Abstract

It is now close to 40 years since the isolation of non-mutable umu/uvm strains of Escherichia coli and the realization that damage induced mutagenesis in E.coli is not a passive process. Early models of mutagenesis envisioned the Umu proteins as accessory factors to the cell's replicase that not only reduced its normally high fidelity, but also allowed the enzyme to traverse otherwise replication-blocking lesions in the genome. However, these models underwent a radical revision approximately 15 years ago, with the discovery that the Umu proteins actually encode for a DNA polymerase, E.coli pol V. The polymerase lacks 3′→5′ exonucleolytic proofreading activity and is inherently error-prone when replicating both undamaged and damage DNA. So as to limit any “gratuitous” mutagenesis, the activity of pol V is strictly regulated in the cell at multiple levels. This review will summarize our current understanding of the myriad levels of regulation imposed on pol V including transcriptional control, posttranslational modification, targeted proteolysis, activation of the catalytic activity of pol V through protein-protein interactions and the very recently described intracellular spatial regulation of pol V. Remarkably, despite the multiple levels at which pol V is regulated, the enzyme is nevertheless able to contribute to the genetic diversity and evolutionary fitness of E.coli.

Keywords: Translesion DNA synthesis, Posttranslational regulation, Proteolysis, Y-family DNA polymerase

1. Introduction

The pioneering studies of Weigle in 1953 [1] demonstrated that survival and mutagenesis of UV-irradiated bacteriophage λ is enhanced if the phage infected a host that had been previously subject to chromosomal DNA damage and provided one of the first hints that E.coli possesses a damage inducible (and potentially error-prone) repair system. These observations were followed up by Witkin who proposed a repressor system which was inactivated by DNA damage as a model to explain Weigle's phage induced reactivation [2]. The pivotal connection to mutagenesis was provided by Radman in a 1974 publication where he outlined an “SOS repair hypothesis” for inducible error-prone repair in E.coli [3]. Although occurring as part of a damage inducible response, it remained unclear at that time if the associated cellular mutagenesis was a passive byproduct of the SOS response, or required the active participation of cellular factors induced as part of the SOS response to facilitate mutagenesis.

The identification of the umuC locus by Kato and Shinoura in 1977 [4] and the allelic uvm locus by Steinborn in 1978 [5] lead to the realization that damage-induced mutagenesis in E.coli is not a passive process. Early mutagenesis models envisaged the Umu proteins as accessory factors to the cell's main replicase, pol III, which would allow it to bypass otherwise replication blocking lesions with a concomitant reduction in replication fidelity [6]. However, we now know that the Umu proteins actually encode for a low-fidelity DNA polymerase, pol V that can catalyze translesion DNA synthesis (TLS) of a variety of DNA lesions in the E.coli genome [7, 8]. Research over the past four decades has revealed numerous and complex levels of regulation that have been imposed on pol V so as to apparently limit its highly mutagenic functions within the cell. However, a low level of mutagenesis is actually beneficial, since it provides genetic diversity and may contribute to overall evolutionary fitness [9, 10]. Indeed, E.coli appears to utilize the various pol V regulatory pathways to provide “just the right amount” of pol V in times of stress, so as to help the organism overcome environmentally challenging adversity.

2. Transcriptional control

The damage-inducible SOS response is regulated through the interplay of two proteins; LexA and RecA [11]. LexA is a transcriptional repressor that binds specific nucleotide sequences located in the promoter region of genes under its control, thereby keeping the target gene's expression to a minimum. RecA is a recombinase that upon DNA damage forms nucleoprotein filaments (commonly called RecA*). Molecules of LexA that are not bound to DNA have a high affinity for the deep helical groove of RecA* [12], where the LexA protein undergoes a self-mediated cleavage reaction [13]. Cleavage of LexA inactivates its ability to serve as a transcriptional repressor. After DNA damage, intracellular levels of intact LexA protein drop and genes that are normally repressed by LexA are subsequently expressed at elevated, derepressed levels.

The LexA binding site is palindromic and has a consensus of TACTG-(TA)5-CAGTA [14, 15]. Binding sites with a close match to the consensus sequence are said to have a low heterology index (H.I.), while those that deviate from the consensus have a high H.I. [16]. Genes that have a high H.I. binding-site are induced early in the SOS response, while those with a low H.I. are expressed much later in the response. The umu locus was shown to be under the transcriptional control of LexA in 1981 [17] and DNA sequence analysis of the umu loci revealed an operon consisting of two genes, umuD and umuC that have a good LexA binding site immediately upstream of the umuD gene [18, 19]. Analysis of the LexA binding site upstream of umuDC indicates that it has an H.I. of 2.77, making it one of the lowest values determined for the binding sites of 40 or so genes that are known to be transcriptionally-regulated by LexA [20]. As a consequence, it is not surprising that induction of the Umu operon occurs late in the SOS-response, and is not fully derepressed until ∼15 minutes after cells have been exposed to DNA damage [21] and significant levels of the Umu proteins do not accumulate until ∼45 minutes after DNA damage [22] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Transcriptional regulation of pol V-catalyzed TLS in E. coli.

In undamaged cells, LexA repressor binds to specific sequences in the promoter region of SOS genes (including recA, lexA, umuDC) (a). The relative affinity of LexA for these sites is determined by the extent the binding-site differs from the consensus site and is determined by the “heterology index” (H.I.). Genes with a high H.I., are expressed at higher basal levels than those with a low H.I. RecA has an H.I., of 4.31 and it is estimated that there are ∼7000 molecules of RecA in an undamaged cell. The umu operon is tightly regulated with an H.I., of 2.77. It is estimated that there are ∼180 molecules of UmuD and ∼15 molecules of UmuC in an undamaged cell. Cellular DNA damage results in the derepression of the SOS regulon (b). RecA protein forms a nucleoprotein filament (RecA*) on single stranded DNA after DNA damage (c). LexA protein has a high affinity for the deep helical groove of RecA* where it undergoes a self-cleavage reaction that inactivates its ability to serve as a transcriptional repressor (d). SOS regulated genes with a high H.I., index such as LexA and RecA are induced early in the SOS response, while those with a low H.I., such as the UmuD and UmuC proteins are induced late in the SOS response. It is estimated that after DNA damage the concentration of RecA increases 10-fold to ∼70,000 molecules per cell. The Umu proteins are induced ∼13-fold, with ∼2400 molecules of UmuD and 200 molecules of UmuC per cell. Like LexA, UmuD has affinity for the deep helical groove of RecA* (e). UmuD undergoes a self-cleavage reaction to generate UmuD′2 (f). Unlike LexA, which is inactivated after cleavage, cleavage of UmuD to UmuD′ activates the protein for its mutagenesis functions. UmuD′2 can subsequently interact with UmuC to generate pol V with peak levels of pol V occurring ∼45 mins after DNA damage (g).

3. Lon-dependent Proteolysis of UmuD and UmuC

While the umuDC operon is one of the tightest regulated by LexA, transcriptional control is nevertheless insufficient to completely eliminate expression of UmuD and UmuC in an undamaged cell [23]. Levels of UmuD and UmuC are, however, kept to a minimum through their targeted proteolysis by the ATP-dependent protease, Lon [24, 25] (Fig. 2). The rapid degradation of the UmuD and UmuC proteins aides the illusion of much tighter transcriptional control than it is in reality since accumulation of the Umu proteins some 45 mins after DNA damage only occurs when their expression outweighs their degradation (Fig. 1). This is probably helped by the fact that other substrates of Lon, such as the cell division inhibitor, SulA [26], are also induced upon DNA damage. The primary Lon recognition site in UmuD has been identified as being located between residues 15 -18 (FPLF), with an auxiliary site between residues 26 - 29 (FPSP) in the amino terminus of UmuD [25]. The Lon recognition site in UmuC has yet to be identified, but is likely to reside in the last 51 carboxyl-terminal amino acid residues of UmuC, since a mutant lacking these residues is extremely stable compared to the normally labile wild-type UmuC protein [27].

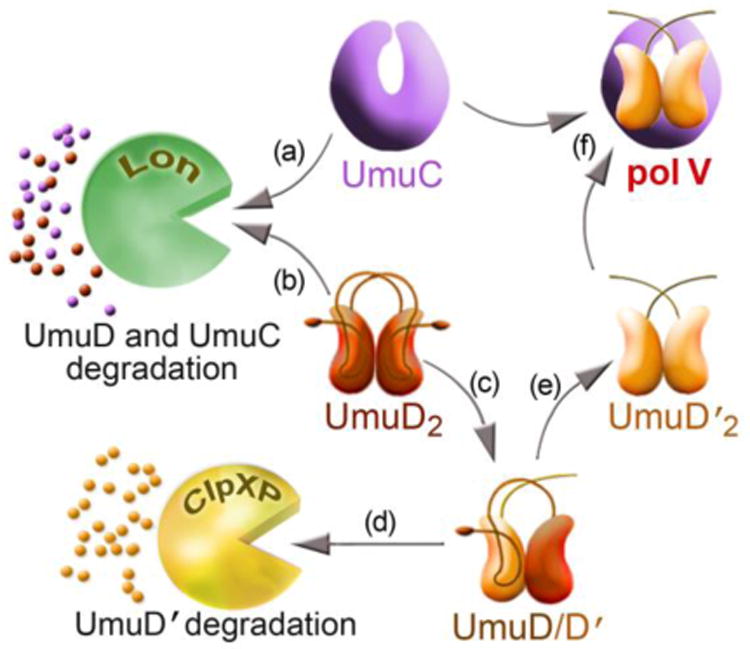

Figure 2. Proteolytic regulation of the Umu proteins helps delay their accumulation until late in the SOS response.

The basal levels of the UmuC (a) and UmuD (b) proteins are kept to a minimum by the ATP-dependent protease, Lon. Late in the SOS response, UmuD2 undergoes an inefficient intermolecular self-cleavage reaction (c). This generates a UmuD/D′ heterodimer and in this context, UmuD′ is rapidly degraded by the ClpXP protease and postpones the accumulation of mutagenically active UmuD′2 (d). In the presence of persistent DNA damage and elevated levels of RecA*, UmuD/D′ is eventually converted to UmuD′2, which is resistant to proteolytic degradation (e). UmuD′2 subsequently interacts with UmuC to generate pol V and in doing so, protects UmuC from Lon-mediated proteolysis (f). This allows for the accumulation of pol V late in the SOS response, when the TLS polymerase is most needed to help facilitate cell-survival.

4. Posttranslational conversion of UmuD to UmuD′

RecA plays a central role in the induction of the LexA-regulated SOS response. However mutants of recA were characterized in the early 1980s that were proficient for LexA cleavage, yet were phenotypically non-mutable after DNA damage [28], indicating that RecA played a direct, 2nd role in induced mutagenesis. Clues as to what this role might be emerged from the DNA sequence analysis of the cloned umuD gene [18, 19], which was shown to have limited homology to the carboxyl-terminus of LexA protein, including a potential cleavage site between residues 24-25 in the N-terminus of UmuD, as well as conserved Serine and Lysine active site residues.

UmuD was shown to undergo RecA-mediated cleavage in vivo [29] and in vitro [30] in 1988. Unlike LexA which is inactivated upon self-cleavage, the cleaved form of UmuD, called UmuD′, was shown to be active for inducible mutagenesis [31]. Indeed, all three of the original umuD mutants isolated by Kato and Shinoura [4] and independently by Steinborn [5] were subsequently shown to encode non-cleavable forms of UmuD [32]. Conversion of mutagenically inactive E.coli UmuD to mutagenically active UmuD′ is extremely slow compared to LexA cleavage in vitro [30]. UmuD exists as a dimer in solution and studies on the nature of the cleavage reaction revealed that it can occur via an intermolecular reaction [33], whereby the cleavage site of one protomer is positioned in the active site of the partner protomer. The slow posttranslational processing of UmuD compared to LexA makes teleological sense, since the cell would want to rapidly induce DNA repair proteins under LexA control, yet also provide time for the repair proteins to work before converting inactive UmuD into a mutagenically active UmuD′ protein.

5. UmuD-UmuD′ heterodimerization and ClpXP proteolysis

It seems unlikely that cleavage of the N-terminal tail of the two UmuD protomers occurs simultaneously, meaning that the proteins would exist as a heterodimer of intact UmuD and processed UmuD′, until such time that the tail of the intact UmuD protomer is eventually processed to form homodimeric UmuD′ [34] (Fig. 2). Unlike homodimeric UmuD2, which is labile and rapidly degraded by the Lon protease, homodimeric UmuD′2 is largely insensitive to Lon-mediated proteolysis and is much more stable than UmuD2 [24].

However UmuD′ in the context of the UmuD/D′ heterodimer is extremely labile and rapidly degraded by the ClpXP protease both in vivo and in vitro [24, 35, 36]. UmuD2 has also been reported to be substrate of ClpXP in vitro [36], but the biological significance of this finding remains unclear, since UmuD2 is stable in a lon- clpXP+ strain in vivo [24]. Rapid ClpXP-dependent proteolysis of UmuD′ in the UmuD/D′ heterodimer therefore provides an additional way to delay the accumulation of mutagenically active UmuD′2 molecules (Fig. 2). Indeed, rapid proteolysis of UmuD′ in the context of UmuD/D′ gives the impression that posttranslational conversion of UmuD to UmuD′ in vivo is slower than it is in reality. It is tacitly assumed that processing of UmuD to UmuD′ only occurs when the cell is severely damaged, yet considerable conversion of UmuD to UmuD′ was observed in an undamaged recA+ lexA(Def) clpX- strain, indicating that UmuD cleavage does occur in an undamaged cell, but UmuD′ does not accumulate due to rapid proteolysis by ClpXP (Fig. 2 and [37]). The fact that homodimeric UmuD′2 is not degraded by ClpXP indicated that the signal for UmuD′ degradation in the context of the UmuD/D′ heterodimer must reside in the N-terminal tail of intact UmuD. Alanine scanning mutagenesis revealed that the ClpXP recognition site that targets UmuD′ for degradation is located between residues 9-12 of UmuD (LREI) [35].

Another interesting observation related to the regulation of the UmuD′ protein by ClpXP is that when homodimers of UmuD2 and UmuD′2 are mixed in vitro, the proteins rapidly rearrange to form heterodimeric UmuD/D′ [38, 39]. A similar rearrangement was recently demonstrated under equilibrium conditions in vitro, confirming that formation of the heterodimeric UmuD/D′ complex is preferred over homodimeric UmuD2 or UmuD′2 [34]. The fact that formation of a UmuD/D′ heterodimer is preferred over formation of homodimers and that UmuD′ becomes susceptible to degradation by ClpXP only when it is part of the heterodimeric complex with UmuD provides a mechanism whereby E.coli can reduce the intracellular levels of the Umu proteins after they have facilitated survival of the damaged cell. As the damage is repaired, the inducing signal that activates RecA* dissipates and the conversion of UmuD2 to UmuD′2 slows. Any homodimeric UmuD′2 already formed in the cell will readily rearrange into a heterodimer with intact UmuD and will be rapidly degraded by ClpXP. Once UmuD′ is degraded, both UmuD2 and UmuC will be degraded by the Lon protease (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Returning cells to a resting state after pol V-dependent TLS has occurred.

During TLS, the intrinsic ATPase of pol V hydrolyzes the ATP molecule (red triangle) associated with pol V Mut and causes the polymerase to dissociate from DNA after a short TLS track has been synthesized (a). RecA also dissociates from UmuD′2C to leave a soluble UmuD′2C (pol V) complex, but with very weak catalytic activity (b). As the SOS inducing signal wanes, the conversion of UmuD to UmuD′ slows. Intact molecules of UmuD preferentially heterodimerize with UmuD′ (c), which renders UmuD′ susceptible to ClpXP-mediated degradation (d). In the absence of UmuD′2, UmuC is unable to remain in aqueous solution (e). The levels of UmuD2 and UmuC are finally returned to a basal state by their Lon-mediate degradation (f).

6. Activation of pol V via protein-protein interactions

Why is UmuD2 unable to promote mutagenesis, whereas UmuD′2 is considered as being mutagenically active? We believe that the answer lies in their respective ability to interact with UmuC. Homodimeric UmuD′2 was shown in 1989 to interact with UmuC forming a soluble and stable ∼70 kDa UmuD′2C complex [40] which can be purified from E.coli when both subunits are co-expressed in vivo [41]. This is in contrast to UmuC, which when expressed alone, is essentially insoluble [40]. We have taken advantage of the tight association between UmuD′2 and UmuC to develop a simple and efficient method to purify milligram quantities of the soluble UmuD′2C complex from just a few liters of culture [42].

Briefly, N-terminal histidine tagged UmuC was expressed at very low levels along with high levels of untagged UmuD′2. The high levels of UmuD′2 help to “solubilize” UmuC and the UmuD′2-His-UmuC complex was readily purified to homogeneity using a handful of chromatographic steps [42]. By comparison, when we substituted intact UmuD2 for UmuD′2 in the expression system, no soluble UmuC or UmuD2C complex was obtained (unpublished observations), indicating that the interaction between UmuC and UmuD2 and UmuD′2 is very different. Furthermore, when UmuD2 was added to the purified UmuD′2C complex in vitro, heterodimerization between UmuD and UmuD′ occurred and UmuC precipitated out of solution [39] (Fig. 3). In essence, UmuC is only truly “soluble” when bound in a complex with UmuD′2. Presumably binding of UmuD′2 to UmuC masks hydrophobic regions of UmuC that would otherwise be solvent exposed in the absence of UmuD′2.

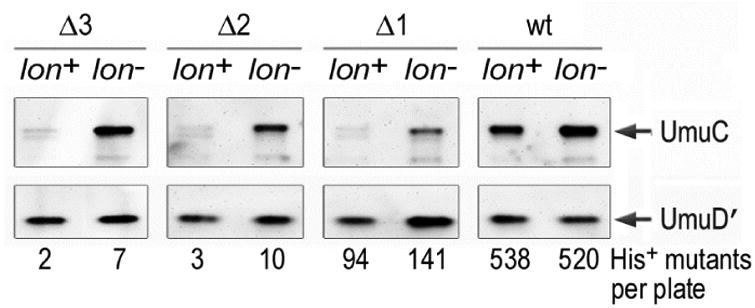

Based upon structural modeling studies, it has been suggested that one protomer of the UmuD′ dimer interacts with UmuC residues 82, 90 and 126-132, while the other protomer interacts with UmuC residues 89, 93, 94 and 239 [43]. In contrast, at least two independent studies have indicated that UmuD′ interacts with the N- and C- terminus of UmuC. By using deletions of UmuC in a yeast two hybrid assay, Jonczyk and Nowicka determined that residues 1-13 and 397-422 are required for an interaction between UmuD′ and UmuC [44]. Sutton et al., also concluded that the 26 C-terminal residues of UmuC are required for the interaction with UmuD′ [45]. By taking advantage of the fact that UmuC is labile and degraded by the Lon protease in vivo unless the protein is in a complex with UmuD′2, we have found that deletion of just one C-terminal residue renders UmuC unstable such that it is barely detectable in the lon+ strain and reduces Umu-dependent mutagenesis to about 20% of that seen with wild-type UmuD′2C, most likely because the mutant has a reduced ability to interact with UmuD′ (Fig .4). Deletion of two or more amino acids essentially renders the strain non-mutable, presumably as a result of the complete loss of the UmuD′2-UmuC interaction. In support of this notion, the Δ2 or Δ3 mutant is unable to promote cellular mutagenesis in a lon- strain, even though the cell contains close to wild-type levels of UmuC (Fig. 4). With the ability to purify milligram quantities of the UmuD′2C complex [42], it surely must only be a matter of time before the crystal structure of pol V is finally determined and the regions of interaction identified.

Fig 4. Removal of C-terminal residues of UmuC disrupts the interaction with UmuD′ and renders UmuC susceptible to Lon-mediated proteolysis.

Western blot showing levels of UmuD′ and UmuC in isogenic lon+ and Δlon recA730 lexA(Def) strains. The UmuD′C proteins were expressed from a low copy plasmid, pRW134 [71]. UmuD′ is not degraded by the Lon protease and similar levels of UmuD′ are observed in both lon+ and Δlon strains. In contrast, UmuC is highly susceptible to Lon-mediated degradation unless it is in a complex with UmuD′2. As clearly seen, UmuC mutants lacking one, two or three C-terminal amino acids are extremely unstable in a lon+ strain, but are stabilized in a Δlon strain. A UmuC mutant lacking just one C-terminal residue exhibited significantly reduced levels of UmuD′C-dependent spontaneous mutagenesis, while mutants lacking two, or three, C-terminal residues of UmuC were rendered essentially non-mutable, as judged by the number of His+ revertants observed per plate. Together, these observations are consistent with the hypothesis that UmuD′ physically interacts with the extreme C-terminus of UmuC and in doing so, protects it from Lon-mediated degradation.

Although formation of UmuD′2C is a pre-requisite for mutagenesis, genetic and biochemical studies have revealed that pol V alone has very weak catalytic activity [42] which is strongly enhanced through interactions with protein partners. One of these partners is RecA. Clues to a direct role of RecA in the pol V-dependent mutagenic process came from genetic studies of Devoret and colleagues who isolated the recA1730 (F117S) allele that is proficient for both LexA and UmuD cleavage, but is unable to promote UmuD′2C (pol V)-dependent mutagenesis in vivo [46-48]. The so-called “3rd role” of RecA in damage induced mutagenesis remained elusive for over 25 years. However, reconstitution of pol V-dependent translesion DNA synthesis in vitro revealed that for efficient TLS to occur, a single molecule of RecA, along with an ATP molecule must be transferred from the 3′ tip of a RecA* filament to UmuD′2C to generate a higher order structure termed pol V Mut [49, 50]. Subsequent biochemical studies have revealed that the ATP molecule is required for pol V Mut to bind a primer-terminus and that an intrinsic ATPase activity of pol V leads to ATP hydrolysis, which in turn, causes pol V Mut to dissociate from DNA [51]. The autoregulatory ATPase activity of pol V therefore helps limit the extent of error-prone DNA synthesis facilitated by pol V Mut (Fig. 3).

Greatest stimulation of TLS is observed when RecA* is trans-activating. Cis-activation could in principle also stimulate pol V activity, but such a mechanism would generate downstream problems, since the RecA* filament formed on the DNA strand being replicated would need to be displaced for pol V Mut to copy DNA [42, 52]. A study showing repetitive “on – off” deactivation – reactivation of pol V Mut, implied that RecA, which remains bound to pol V Mut in both states, is likely to bind in different locations [50]. Very recently, cross-linking studies have indicated that the 3′ tip of RecA* (residues 112-117) interacts with two separate regions of UmuC that include residues 257-277 and 362-377 that are over 40Å apart, suggesting at least two distinct binding modes of the RecA-UmuC interaction [53].

Like all of E.coli's DNA polymerases, pol V interacts with the β–sliding clamp through a conserved canonical binding site [54]. This interaction is essential for pol V-dependent mutagenesis in vivo [55]. As expected, the interaction with β–clamp increases the processivity of pol V [56]. Pol V replicates DNA very slowly and is estimated to only incorporate one nucleotide every 2 seconds [42]. In the absence of the β-clamp, pol V can only replicate ∼30 nucleotides (in 2 mins) before dissociating from the primer-template. In contrast, in the presence of the β–sliding clamp, pol V can replicate several hundred nucleotides, if assayed under extended reaction times in the presence of ATPγS [42]. Interestingly, even in the presence of the β-clamp pol V exhibited very limited synthesis in the absence of single stranded binding (SSB) protein [42], indicating that SSB is another key co-factor required to stimulate pol V synthesis (Fig. 3).

7. Spatial regulation of pol V

One could easily imagine that the levels of regulation imposed on pol V and described above would be sufficient to keep the enzyme “in check”. However, recent studies have revealed yet another level of regulation, namely spatial regulation of pol V [57]. Through the use of single molecule fluorescent microscopy, electron microscopy and western blotting of soluble E.coli extracts, it was discovered that when first induced after DNA damage, UmuC is sequestered on the inner membrane. Over time, it re-localizes to the cytosol. The timing of the re-localization is concurrent with the conversion of UmuD to UmuD′ and the accumulation of soluble UmuD′2C [57] (Fig. 5). At the present time, it is unknown how UmuC is initially sequestered on the inner membrane, but it is interesting to speculate that an exposed hydrophobic surface on monomeric UmuC is occluded when UmuD′2 binds to UmuC to generate soluble UmuD′2C (Fig. 5).

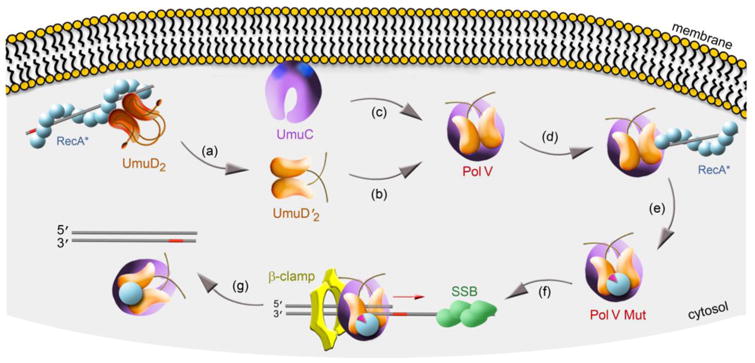

Figure 5. Spatial regulation of pol V.

UmuC protein expressed >30 min after DNA damage is sequestered on the inner cellular membrane, possibly as a result of exposed hydrophobic patches on its surface (blue spots). Inefficient cleavage UmuD to UmuD′ occurs in the deep helical groove of RecA* that may also be membrane associated [72, 73] (a). Once generated, UmuD′2 (b) has high affinity for UmuC (c). We hypothesize that when UmuD′2 binds to UmuC, it occludes the previously exposed hydrophobic surface on monomeric UmuC and allows the soluble UmuD′2C (pol V) complex to re-localize to the cytosol. Soluble pol V transiently interacts with the 3′ tip of RecA* (d), where it acquires a molecule of RecA and ATP to generate pol V Mut ∼45 min after the damage (e). Pol V Mut is targeted to a lesion-containing (red bar) primer-template through an interaction with the β–sliding clamp protein and is further stimulated in the presence of single stranded binding (SSB) (f). After TLS, ATP-hydrolysis catalyzed by the intrinsic DNA-dependent ATPase activity of pol V triggers dissociation of pol V Mut from DNA, thus minimizing the error-prone tracts of DNA synthesized by pol V Mut (g).

8. Alternative mechanisms of regulation imposed on pol V orthologs

It is now known that many gram-negative bacteria and their plasmids harbor pol V orthologs. Very few of these orthologs have been as well characterized as E.coli pol V, but where they have, it is interesting to determine how the activity of the pol V ortholog is regulated. Compared to E.coli, Salmonella typhimurium is poorly mutable. Like E. coli UmuD, S. typhimurium UmuD is subject to rapid proteolysis by the Lon protease [37]. Yet Lon regulation is largely circumvented because S. typhimurium UmuD is very efficiently converted to homodimeric UmuD′2 [58], thereby avoiding both Lon-mediated degradation of homodimeric UmuD2 and ClpXP-degradation of heterodimeric UmuD/D′.

It appears that S. typhimurim has no need to utilize targeted proteolysis as a form of regulation to limit the mutagenic activity of pol V since the S. typhiumurim UmuC protein is unable to promote significant levels of cellular mutagenesis [59]. Based upon analysis of chimera with regions of E. coli UmuC interchanged with S. typhimurium UmuC, the 8 residues that differ between amino acids 26-60 that comprise the substrate lid of the fingers domain of the polymerase [60] appear to be responsible for the poor mutability [61]. At the present time, S. typhimurium pol V has not been purified and characterized biochemically and it is unknown if the poor mutability is due to a loss of catalytic activity, or an increase in the fidelity of the S. typhimurium pol V compared to E.coli pol V.

Similarly, the most error-prone pol V ortholog characterized to date is pol VR391 encoded by rumAB from the integrating conjugating element (ICE) 391 (formerly known as IncJ R391) [62-64]). When located in its native environment (an 88.5kb ICE), pol VR391 promotes very low levels of cellular mutagenesis in E.coli [65]. The observed level of mutagenesis increased dramatically when the rumAB operon was sub-cloned [62]. RumA is cleaved to a RumA′ at a similar rate to E.coli UmuD, indicating that inefficient cleavage may help attenuate pol VR391 activity [63], but it does not explain why the cellular mutagenesis increased when the rumAB operon was sub-cloned.

Analysis of the DNA sequence of the ICE391 (Genbank AY090559) reveals that it encodes a Lon protease homolog (orf31) that may degrade RumA and/or RumB; a putative 3′→5′ exonuclease (orf13) immediately upstream of the rumAB operon that may proofread any errors made by pol VR391; and a lambda cI-like repressor, called SetR (orf 96) [66] that may also down-regulate rumAB expression. We assume that these proteins combine to substantially reduce pol VR391–dependent mutagenesis when expressed from the ICE391 and as such, the catalytic activity of pol VR391 has not been subjected to any evolutionary pressure to curtail its mutagenesis promoting ability, thereby explaining why the enzyme is so potent when cloned away from its cis-acting regulating proteins. The fact that pol VR391 retains the potential to be highly mutagenic when unshackled from its normal regulation is worrisome. Antibiotics are known to induce the SOS response in bacteria [67, 68] and the mobilization of ICE391 [69]. The ICE391 elements are widely distributed in pathogenic strains of Vibrio cholera and prolonged exposure to SOS-inducing antibiotics may lead to the attenuation of regulatory mechanisms that normally keep pol VR391 activity to a minimum and may allow the pathogenic bacteria to adapt and ultimately acquire antibiotic resistance.

9. Concluding remarks and future perspectives

It is clear that bacteria use a variety of regulatory mechanisms to keep the mutagenesis-promoting activity of pol V enzymes at a level they can tolerate. In the case of E.coli, it is at multiple levels. S. typhimurium appears, on the surface, to do so with one fail swoop through a few amino acid substitutions in its UmuC protein. In contrast, pol VR391 has not been subjected to evolutionary pressures to curtail its very efficient mutagenesis-promoting activity because the enzyme is usually “kept in check” by a multitude of cis-acting regulatory factors. The result is that the TLS and mutagenesis promoting activity of pol V enzymes are minimalized until such time that they are needed for cell survival and mutagenesis, so as to maintain the evolutionary fitness of the host organism [9, 10, 70].

Such complex levels of regulation could hardly be imagined some 40 years ago when the umu operon was first discovered. Indeed, one gets the sense that we may have only revealed the “tip of the iceberg” on understanding how “simple” bacteria regulate the mutagenic process. To date, much of the studies on pol V have centered on E.coli, yet as noted above, there are hints that other bacteria utilize alternate mechanism to keep the error-prone polymerase in check. The advent of new technologies, such as single cell fluorescent microscopy, for example, opens up endless avenues of research on understanding (in three dimensions), how and when, any given bacterium (not just E.coli) responds to environmental damage (such as chronic exposure to antibiotics), and the subsequent evolution of antibiotic resistance that ensures cell survival. Based upon previous studies, it likely that a variety of novel and ingenious mechanisms that regulate the mutagenic process still remain to be discovered. One can only imagine where our understanding of such regulation might be in five years time, let alone another forty.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible by funding from the NIH/NICHD Intramural Research Program to R.W. and ES012259, GM21422 to M.F.G. We thank Alexandra Vaisman for generating the figures shown in this review article.

Abbreviations

- nt

nucleotide

- dNTP

deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate

- rNTP

ribonucleoside triphosphate

- pol

DNA polymerase

- TLS

Translesion DNA synthesis

- CPD

cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer

- RecA*

RecA bound to single-stranded DNA forming a nucleoprotein filament

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Weigle JJ. Induction of mutation in a bacterial virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1953;39:628–636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.39.7.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Witkin EM. The radiation sensitivity of Escherichia coli B: a hypothesis relating filament formation and prophage induction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;57:1275–1279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.57.5.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radman M. Phenomenology of an inducible mutagenic DNA repair pathway in Escherichia coli: SOS repair hypothesis. In: Prakash L, Sherman F, Miller MW, Lawrence CW, Tabor HW, editors. Molecular and environmental aspects of mutagenesis. Charles C Thomas; Springfield, Ill: 1974. pp. 128–142. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kato T, Shinoura Y. Isolation and characterization of mutants of Escherichia coli deficient in induction of mutations by ultraviolet light. Mol Gen Genet. 1977;156:121–131. doi: 10.1007/BF00283484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinborn G. Uvm mutants of Escherichia coli K12 deficient in UV mutagenesis. I. Isolation of uvm mutants and their phenotypical characterization in DNA repair and mutagenesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1978;165:87–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00270380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bridges BA, Woodgate R. The two-step model of bacterial UV mutagenesis. Mutat Res. 1985;150:133–139. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(85)90110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang M, Shen X, Frank EG, O'Donnell M, Woodgate R, Goodman MF. UmuD′2C is an error-prone DNA polymerase, Escherichia coli, DNA pol V. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8919–8924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reuven NB, Arad G, Maor-Shoshani A, Livneh Z. The mutagenesis protein UmuC is a DNA polymerase activated by UmuD′, RecA, and SSB and Is specialized for translesion replication. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31763–31766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.31763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeiser B, Pepper ED, Goodman MF, Finkel SE. SOS-induced DNA polymerases enhance long-term survival and evolutionary fitness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8737–8741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092269199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corzett CH, Goodman MF, Finkel SE. Competitive fitness during feast and famine: how SOS DNA polymerases influence physiology and evolution in Escherichia coli. Genetics. 2013;194:409–420. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.151837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Little JW, Mount DW. The SOS regulatory system of Escherichia coli. Cell. 1982;29:11–22. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu X, Egelman EH. The LexA repressor binds within the deep helical groove of the activated RecA filament. J Mol Biol. 1993;231:29–40. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Little JW. Autodigestion of LexA and phage repressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1375–1379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker GC. Mutagenesis and inducible responses to deoxyribonucleic acid damage in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1984;48:60–93. doi: 10.1128/mr.48.1.60-93.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg OG. Selection of DNA binding sites by regulatory proteins: the LexA protein and the arginine repressor use different strategies for functional specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:5089–5105. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.11.5089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis LK, Harlow GR, Gregg-Jolly LA, Mount DW. Identification of high affinity binding sites for LexA which define new DNA damage-inducible genes in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1994;241:507–523. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bagg A, Kenyon CJ, Walker GC. Inducibility of a gene product required for UV and chemical mutagenesis in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:5749–5753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.9.5749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitagawa Y, Akaboshi E, Shinagawa H, Horii T, Ogawa H, Kato T. Structural analysis of the umu operon required for inducible mutagenesis in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4336–4340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.13.4336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perry KL, Elledge SJ, Mitchell B, Marsh L, Walker GC. umuDC and mucAB operons whose products are required for UV light and chemical-induced mutagenesis: UmuD, MucA, and LexA products share homology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4331–4335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.13.4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernández de Henestrosa AR, Ogi T, Aoyagi S, Chafin D, Hayes JJ, Ohmori H, Woodgate R. Identification of additional genes belonging to the LexA-regulon in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:1560–1572. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato N, Ohnishi T, Tano K, Yamamoto K, Nozu K. Induction of UMUC+ gene expression in Escherichia coli irradiated by near ultraviolet light. Photochem Photobiol. 1985;42:135–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1985.tb01551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sommer S, Boudsocq F, Devoret R, Bailone A. Specific RecA amino acid changes affect RecA-UmuD′C interaction. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:281–291. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woodgate R, Ennis DG. Levels of chromosomally encoded Umu proteins and requirements for in vivo UmuD cleavage. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;229:10–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00264207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank EG, Ennis DG, Gonzalez M, Levine AS, Woodgate R. Regulation of SOS mutagenesis by proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10291–10296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez M, Frank EG, Levine AS, Woodgate R. Lon-mediated proteolysis of the Escherichia coli UmuD mutagenesis protein: in vitro degradation and identification of residues required for proteolysis. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:3889–3899. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizusawa S, Gottesman S. Protein degradation in Escherichia coli: the lon gene controls the stability of sulA protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:358–362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.2.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodgate R, Singh M, Kulaeva OI, Frank EG, Levine AS, Koch WH. Isolation and characterization of novel plasmid-encoded umuC mutants. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5011–5021. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.5011-5021.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blanco M, Herrera G, Collado P, Rebollo JE, Botella LM. Influence of RecA protein on induced mutagenesis. Biochimie. 1982;64:633–636. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(82)80102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shinagawa H, Iwasaki H, Kato T, Nakata A. RecA protein-dependent cleavage of UmuD protein and SOS mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1806–1810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burckhardt SE, Woodgate R, Scheuermann RH, Echols H. UmuD mutagenesis protein of Escherichia coli: overproduction, purification and cleavage by RecA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1811–1815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nohmi T, Battista JR, Dodson LA, Walker GC. RecA-mediated cleavage activates UmuD for mutagenesis: mechanistic relationship between transcriptional derepression and posttranslational activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1816–1820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koch WH, Ennis DG, Levine AS, Woodgate R. Escherichia coli umuDC mutants: DNA sequence alterations and UmuD cleavage. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;233:443–448. doi: 10.1007/BF00265442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDonald JP, Frank EG, Levine AS, Woodgate R. Intermolecular cleavage of the UmuD-like mutagenesis proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1478–1483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ollivierre JN, Sikora JL, Beuning PJ. Dimer exchange and cleavage specificity of the DNA damage response protein UmuD. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1834:611–620. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonzalez M, Rasulova F, Maurizi MR, Woodgate R. Subunit-specific degradation of the UmuD/D′ heterodimer by the ClpXP protease: The role of trans recognition in UmuD′ stability. EMBO J. 2000;19:5251–5258. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neher SB, Sauer RT, Baker TA. Distinct peptide signals in the UmuD and UmuD′ subunits of UmuD/D′ mediate tethering and substrate processing by the ClpXP protease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13219–13224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235804100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez M, Frank EG, McDonald JP, Levine AS, Woodgate R. Structural insights into the regulation of SOS mutagenesis. Acta Biochemica Polonica. 1998;45:163–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Battista JR, Ohta T, Nohmi T, Sun W, Walker GC. Dominant negative umuD mutations decreasing RecA-mediated cleavage suggest roles for intact UmuD in modulation of SOS mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7190–7194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shen X, Woodgate R, Goodman MF. Escherichia coli DNA polymerase V subunit exchange: a post-SOS mechanism to curtail error-prone DNA synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52546–52550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310127200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodgate R, Rajagopalan M, Lu C, Echols H. UmuC mutagenesis protein of Escherichia coli: purification and interaction with UmuD and UmuD′. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7301–7305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruck I, Woodgate R, McEntee K, Goodman MF. Purification of a soluble UmuD′C complex from Escherichia coli: Cooperative binding of UmuD′C to single-stranded DNA. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10767–10774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karata K, Vaisman A, Goodman MF, Woodgate R. Simple and efficient purification of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase V: cofactor requirements for optimal activity and processivity in vitro. DNA Repair. 2012;11:431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chandani S, Loechler EL. Structural model of the Y-Family DNA polymerase V/RecA mutasome. J Mol Graph Model. 2013;39:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jonczyk P, Nowicka A. Specific in vivo protein-protein interactions between Escherichia coli SOS mutageneis proteins. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2580–2585. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2580-2585.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sutton MD, Walker GC. umuDC-mediated cold sensitivity is a manifestation of functions of the UmuD(2)C complex involved in a DNA damage checkpoint control. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1215–1224. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1215-1224.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dutreix M, Moreau PL, Bailone A, Galibert F, Battista JR, Walker GC, Devoret R. New recA mutations that dissociate the various RecA protein activities in Escherichia coli provide evidence for an additional role for RecA protein in UV mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2415–2423. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2415-2423.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bailone A, Sommer S, Knezevic J, Dutreix M, Devoret R. A RecA protein mutant deficient in its interaction with the UmuDC complex. Biochimie. 1991;73:479–484. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90115-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dutreix M, Burnett B, Bailone A, Radding CM, Devoret R. A partially deficient mutant, recA1730, that fails to form normal nucleoprotein filaments. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;232:489–497. doi: 10.1007/BF00266254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schlacher K, Cox MM, Woodgate R, Goodman MF. RecA acts in trans to allow replication of damaged DNA by DNA polymerase V. Nature. 2006;442:883–887. doi: 10.1038/nature05042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang Q, Karata K, Woodgate R, Cox MM, Goodman MF. The active form of DNA polymerase V is UmuD′2C-RecA-ATP. Nature. 2009;460:359–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Erdem AL, Jaszczur M, Bertram JG, Woodgate R, Cox MM, Goodman MF. DNA polymerase V activity is autoregulated by a novel intrinsic DNA-dependent ATPase. Elife. 2014;3:e02384. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pham P, Bertram JG, O'Donnell M, Woodgate R, Goodman MF. A model for SOS-lesion targeted mutations in E. coli involving pol V, RecA, SSB and β sliding clamp. Nature. 2001;409:366–370. doi: 10.1038/35053116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gruber AJ, Erdem AL, Sabat G, Karata K, Jaszczur MM, Vo DD, Olsen TM, Woodgate R, Goodman MF, Cox MM. A RecA Protein Surface Required for Activation of DNA Polymerase V. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dalrymple BP, Kongsuwan K, Wijffels G, Dixon NE, Jennings PA. A universal protein-protein interaction motif in the eubacterial DNA replication and repair systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11627–11632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191384398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Becherel OJ, Fuchs RP, Wagner J. Pivotal role of the β-clamp in translesion DNA synthesis and mutagenesis in E. coli cells. DNA Repair. 2002;1:703–708. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang M, Pham P, Shen X, Taylor JS, O'Donnell M, Woodgate R, Goodman M. Roles of E. coli DNA polymerases IV and V in lesion-targeted and untargeted SOS mutagenesis. Nature. 2000;404:1014–1018. doi: 10.1038/35010020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Robinson A, McDonald JP, Caldas VE, Patel M, Wood EA, Punter CM, Ghodke H, Cox MM, Woodgate R, Goodman MF, van Oijen AM. Regulation of mutagenic DNA polymerase V: activation in space and time. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005482. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Woodgate R, Levine AS, Koch WH, Cebula TA, Eisenstadt E. Induction and cleavage of Salmonella typhimurium UmuD protein. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;229:81–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00264216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sedgwick SG, Ho C, Woodgate R. Mutagenic DNA repair in Enterobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5604–5611. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.18.5604-5611.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ling H, Boudsocq F, Woodgate R, Yang W. Crystal structure of a Y-family DNA polymerase in action: a mechanism for error-prone and lesion-bypass replication. Cell. 2001;107:91–102. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00515-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koch WH, Kopsidas G, Meffle B, Levine AS, Woodgate R. Analysis of chimeric UmuC proteins: identification of regions in Salmonella typhimurium UmuC important for mutagenic activity. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;251:121–129. doi: 10.1007/BF02172909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ho C, Kulaeva OI, Levine AS, Woodgate R. A rapid method for cloning mutagenic DNA repair genes: isolation of umu-complementing genes from multidrug resistance plasmids R391, R446b, and R471a. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5411–5419. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5411-5419.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kulaeva OI, Wootton JC, Levine AS, Woodgate R. Characterization of the umu-complementing operon from R391. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2737–2743. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2737-2743.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mead S, Vaisman A, Valjavec-Gratian M, Karata K, Vandewiele D, Woodgate R. Characterization of polVR391: a Y-family polymerase encoded by rumA′B from the IncJ conjugative transposon, R391. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:797–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pinney RJ. Distribution among incompatibility groups of plasmids that confer UV mutability and UV resistance. Mutat Res. 1980;72:155–159. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(80)90232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beaber JW, Waldor MK. Identification of operators and promoters that control SXT conjugative transfer. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5945–5949. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.17.5945-5949.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cirz RT, Chin JK, Andes DR, de Crecy-Lagard V, Craig WA, Romesberg FE. Inhibition of mutation and combating the evolution of antibiotic resistance. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cirz RT, Jones MB, Gingles NA, Minogue TD, Jarrahi B, Peterson SN, Romesberg FE. Complete and SOS-mediated response of Staphylococcus aureus to the antibiotic ciprofloxacin. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:531–539. doi: 10.1128/JB.01464-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beaber JW, Hochhut B, Waldor MK. SOS response promotes horizontal dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. Nature. 2004;427:72–74. doi: 10.1038/nature02241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tark M, Tover A, Tarassova K, Tegova R, Kivi G, Horak R, Kivisaar M. A DNA polymerase V homologue encoded by TOL plasmid pWW0 confers evolutionary fitness on Pseudomonas putida under conditions of environmental stress. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5203–5213. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5203-5213.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Szekeres ESJ, Woodgate R, Lawrence CW. Substitution of mucAB or rumAB for umuDC alters the relative frequencies of the two classes of mutations induced by a site-specific T-T cyclobutane dimer and the efficiency of translesion DNA synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2559–2563. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2559-2563.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Garvey N, St John AC, Witkin EM. Evidence for RecA protein association with the cell membrane and for changes in the levels of outer membrane proteins in SOS-induced Escherichia coli cells. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:870–876. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.3.870-876.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rajendram M, Zhang L, Reynolds BJ, Auer GK, Tuson HH, Ngo KV, Cox MM, Yethiraj A, Cui Q, Weibel DB. Anionic phospholipids stabilize RecA filament bundles in Escherichia coli. Mol Cell. 2015;60:374–384. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]