Abstract

Langerhans cells (LC) induce Type 2 antibodies (Ab) reactive with protein antigens (Ag) that are applied to murine skin in the absence of adjuvant after extending their dendrites through tight junctions (TJ) to acquire Ag and migrating to regional lymph nodes (LN). In response to contact sensitizers, EpCAM on LC promotes LC dendrite mobility and LC migration. In epithelial cells, EpCAM regulates expression and distribution of selected TJ-associated claudins. To determine if EpCAM regulates claudins in LC and immune responses to externally applied proteins, we studied conditional KO mice with EpCAM-deficient LC (LC EpCAM cKO). Although LC claudin-1 levels were dramatically reduced in the absence of EpCAM, LC EpCAM cKO and control LC dendrites docked with epidermal TJ with equal efficiencies and ingested surface proteins. Topical immunization of LC EpCAM cKO mice with ovalbumin (Ova) led to increased induction of Type 2 Ova-specific Ab and enhanced proliferation of Ova-reactive T cells associated with increased accumulation of LC in LN. These results suggest that, in the absence of strong adjuvants, EpCAM-deficient LC exhibit increased migration to regional LN. EpCAM appears to differentially regulate LC mobility/migration in the setting of limited inflammation as compared with the intense inflammation triggered by contact sensitizers.

INTRODUCTION

Langerhans cells (LC) are resident epidermal dendritic cells (DC) that migrate to skin-draining lymph nodes (LN) during the steady state and in response to inflammatory stimuli (Schuler and Steinman, 1985) (Jakob et al., 2001) (Merad et al., 2008). Dogma long held that LC were essential for the initiation of T cell-dependent immune responses directed against foreign antigens that were delivered onto, or into, skin (Kaplan et al., 2008) but in vivo experiments involving LC knockout mice have demonstrated that this is not invariably the case (Kaplan et al., 2005) (Kissenpfennig et al., 2005) (Bennett et al., 2005). Work that has been conducted in multiple laboratories has clarified the roles of LC and other skin DC subpopulations in the enhancement and attenuation of cutaneous immunity to foreign antigens and autoantigens (Allan et al., 2003) (Kaplan et al., 2005) (Kissenpfennig et al., 2005) (Bennett et al., 2005) (Henri et al., 2010) (Kautz-Neu et al., 2011) (Igyarto et al., 2011) (Ouchi et al., 2011) (Seneschal et al., 2014), but questions and controversies remain (Kaplan, 2010) (Igyarto and Kaplan, 2013).

Recently, it was reported that LC initiate Th2-type humoral immune responses (IgG1 and IgE subclasses), but not-Th1 type humoral immune responses, to protein antigens that were applied topically to murine skin (Nagao et al., 2009a) (Ouchi et al., 2011) (Nakajima et al., 2012). In this setting, activated LC docked with epidermal tight junctions (TJ) in the stratum granulosum, extended their dendrites through TJ, acquired Ag that was external to TJ and subsequently migrated to LN to initiate immune responses (Kubo et al., 2009) (Ouchi et al., 2011). This process involved TJ reorganization as manifested by redistribution of TJ-associated claudins without obvious compromise of TJ function (Kubo et al., 2009). Activated human LC also have the ability to interact with epidermal TJ, and it has been suggested that LC may initiate or facilitate immune responses to environmental Ag in atopic individuals (Yoshida et al., 2014).

EpCAM (Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule, CD326) is a membrane glycoprotein that is expressed on the surfaces of LC, some developing and developed epithelia and some carcinomas (Balzar et al., 1999) (Trzpis et al., 2007) (Schnell et al., 2013). It has been suggested that EpCAM promotes intercellular adhesion through homophilic interactions (Litvinov et al., 1994), but that it also attenuates cadherin-mediated adhesion (Winter et al., 2003). More recent studies indicate that EpCAM may function as an outside-in signaling molecule that regulates gene transcription (Maetzel et al., 2009). We, and others, have demonstrated that EpCAM binds avidly to some claudins (Ladwein et al., 2005) (Wu et al., 2013), and EpCAM regulates TJ composition and function by modulating amounts and localization of TJ-associated claudins in human colon cancer cells (Wu et al., 2013).

Among DC, EpCAM is selectively expressed at high levels by LC (Borkowski et al., 1996). To study EpCAM in LCs, we developed KO mice in which EpCAM is selectively deleted in LC. We previously reported that EpCAM-deficient LC exhibit impaired mobility and migration in, and from, murine skin that had been treated with strong contact sensitizers (Gaiser et al., 2012). Dendrite extension and retraction was also attenuated in EpCAM-deficient LC in these experiments. Therefore, we hypothesized that EpCAM might modulate the ability of LC dendrites to interact with and penetrate epidermal TJ, and that topical immunization to protein Ag might be compromised in LC EpCAM cKO mice.

In the present study, we demonstrate that EpCAM-deficient LC did not exhibit impaired ability to dock their dendrites with epidermal TJ, or obvious defects in surface protein uptake. Moreover, topical immunization of LC EpCAM cKO mice with ovalbumin (Ova) led to enhanced formation of Type 2 Ova-specific Ab and enhanced proliferation of adoptively transferred Ova-reactive OT-II transgenic T cells accompanied by accumulation of increased (rather than decreased) numbers of LC in regional LN. We conclude that the mobility and migration of EpCAM-deficient LC is enhanced in this model system whereas it was decreased in experiments involving contact sensitizers.

RESULTS

Regulation of Claudin-1 Expression in LCs By EpCAM

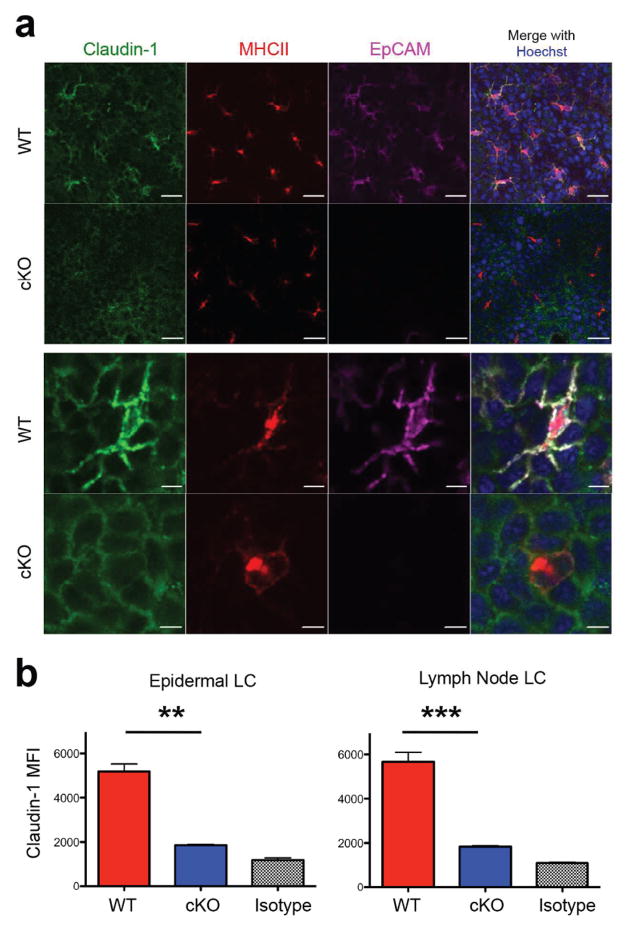

We previously reported that EpCAM modulates adhesion and TJ function by regulating intracellular localization of selected claudins in human colon cancer cells (Wu et al., 2013). EpCAM accomplishes this by associating with claudin-1 and claudin-7 and protecting these TJ-associated proteins from lysosomal degradation (Wu et al., 2013). LC express claudin-1 (Zimmerli and Hauser, 2007), and LC claudin-1 accumulates at LC-TJ docking points as LC extend their dendrites between keratinocytes in the stratum granulosum during antigen uptake (Kubo et al., 2009). To determine if EpCAM regulates LC claudin-1 expression, claudin-1 expression was assessed in EpCAM-deficient LC using immunofluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry. Consistent with previous results (Kubo et al., 2009), immunofluorescence studies of unperturbed epidermis revealed that LC expressed claudin-1 at high levels on cell surfaces while MHC Class II (MHCII) molecules were detected intracellularly (Figure 1a). In control LC, EpCAM co-localized with claudin-1, while expression of both proteins was essentially abolished in EpCAM-deficient LCs (Figure 1a). Flow cytometry confirmed that claudin-1 was down-regulated in EpCAM-deficient LC (p < 0.01) to almost background levels (Figure 1b). EpCAM-deficient MHCIIhigh CD11c+ Langerin+ CD103− cells in skin-draining lymph nodes, representing epidermal LC that had migrated from epidermis, also expressed reduced levels of claudin-1 (p < 0.001) (Figure 1b).

Figure 1. EpCAM regulates claudin-1 expression in LCs.

(a) Reduction of Claudin-1 expression in EpCAM-deficient LCs in unperturbed epidermis as assessed by confocal microscopy. Bars = 20 μ (upper panels) Bars = 5 μ (lower panels). (b) Quantification of claudin-1 content of EpCAM-deficient and control LCs from unperturbed epidermis and skin draining lymph nodes using flow cytometry. Mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) of claudin-1 in MHCII+ CD45+ LCs isolated from epidermis (left) or MHCIIhigh CD11c+ Langerin+ CD103− cells from skin draining LN (right) are depicted. Data shown is from n = 3 experiments. **P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001 via Student’s t test as indicated.

We hypothesized that activated EpCAM-deficient LC would be unable to reorganize TJ at LC-KC contacts, and that this would be reflected in reduced surface antigen uptake and immune response initiating activity. As shown previously (Kubo et al., 2009), en face images of unperturbed control epidermis revealed continuous networks of claudin-1-containing TJ located between the first and second layers of the stratum granulosum (SG1 and SG2) (Figure S1a). Similar networks were present in epidermis obtained from LC EpCAM cKO mice (Figure S1a). In unperturbed epidermis, dendrites of control and EpCAM-deficient LC did not interact with TJ and MHCII was present in an intracellular location (Figure S1a). Light tape stripping activated LC in both control and LC EpCAM cKO mice leading to MHCII redistribution (from intracellular locations to cell surfaces) and LC-TJ docking manifested by the appearance of MHCII- and langerin-containing dendrite tips at the SG1-SG2 level. LC-TJ docking points contained similar amounts of claudin-1 independent of LC EpCAM expression LC (Figure S1a), suggesting that at least a portion of this claudin-1 is keratinocyte-derived or, that in LC, TJ-associated claudin-1 is in a different intracellular pool than that which is not TJ-associated. Vertical confocal microscopic sections confirmed down regulation of claudin-1 expression in the EpCAM-deficient LCs with retained expression of claudin-1 at LC-TJ docking points (Figure S1B).

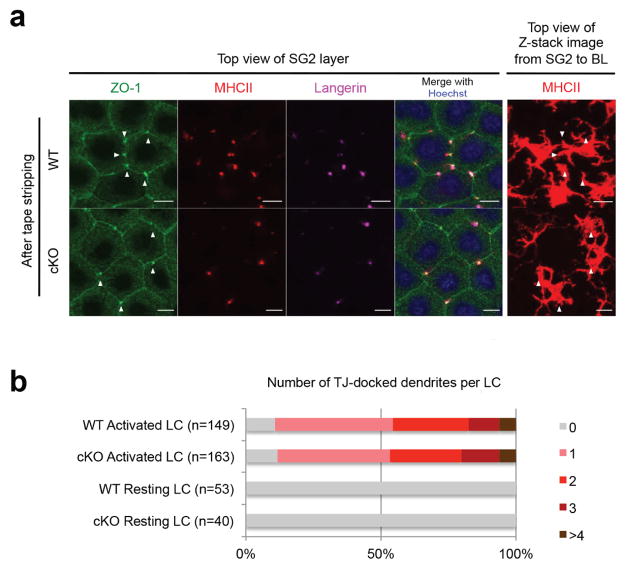

Dendrites of EpCAM-deficient LCs efficiently dock with epidermal TJ

To assess the ability of EpCAM-deficient LC to interact with epidermal TJ, control and LC EpCAM cKO ear skin was subjected to limited tape-stripping and LC-TJ docking points were enumerated in en face immunofluorescence images of epidermis obtained 16 h later. LC-TJ docking points were identified as co-accumulations of TJ-associated ZO-1, MHCII and Langerin, and their association with individual activated LC was verified by scanning through corresponding z-stack images (Figure 2a). As expected, individual control LC docked with TJ very efficiently (~90%) and almost 50% of activated LC docked with TJ via multiple dendrites (Figure 2b). EpCAM-deficient LC docked with epidermal TJ with comparable frequencies and numbers of LC-TJ docking points per activated EpCAM-deficient LC were also not different from controls (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. EpCAM-deficient LC efficiently dock with epidermal TJ.

(a) TJ docking points involving activated LCs and KC were identified as ZO-1 high MHCIIhigh Langerin high accumulations (arrowheads) visualized using confocal microscopy. Bars = 10 μ. (b) Quantification of LC TJ-docking efficiencies determined 16 h after light tape stripping. Data presented is representative of that obtained with 4 mice (a) and aggregated from 2 independent experiments (b).

Retention of TJ barrier function at EpCAM-deficient LC-TJ docking points

To address the issue of barrier compromise in mice with EpCAM-deficient LC, we treated control and LC EpCAM cKO mice with S. aureus exotoxin (ETA) and a small molecule protein-labeling reagent (NHS-long chain (LC)-Biotin). ETA is a 27 kDa protease that cleaves desmoglein-1 and causes superficial acantholysis when it gains access to epidermal desmosomes (Amagai et al., 2000) (Stanley and Amagai, 2006). Sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin (NHS-LC-biotin) is a membrane impermeable small molecule that reacts with accessible lysine residues and can be visualized with fluorchrome-streptavidin. Intradermal injection of ETA caused formation of subcorneal blisters in control skin, as expected (Figure S2). Topical application of ETA onto intact control or LC EpCAM cKO skin as described in Materials and Methods did not cause blisters (assessed 24 h after ETA exposure) (Figure S2).

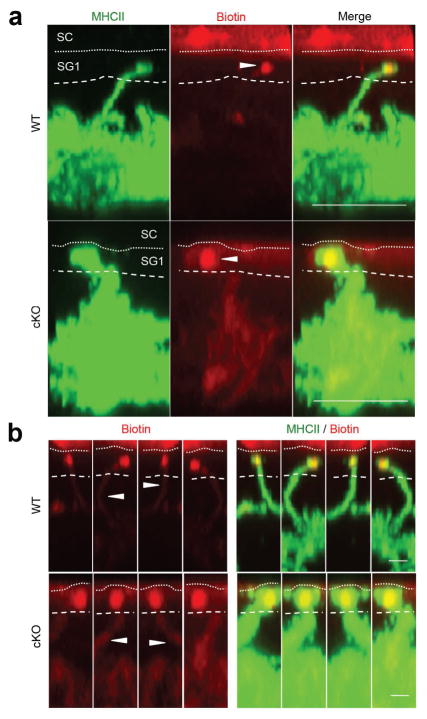

Topically applied NHS-LC-biotin also did not readily penetrate into control or LC EpCAM cKO skin (data not shown). However, consistent with previous experience and the literature (Kubo et al., 2009), it was possible to visualize rare instances where skin surface-derived, streptavidin-marked, biotin-labeled proteins co-localized with the tips of WT LC dendrites that had extended through TJ into the SG1 layer (Figure 3a). Examination of these infrequent events in multiple orientations verified that biotinylated proteins had actually been internalized into WT LC dendrites (see biotin-containing “streaks” in Figure 3b). Although reliable quantification of LC internalization of labeled skin surface proteins was not possible, both control and EpCAM-deficient LC exhibited this activity (Figure 3a, 3b). These results suggest that TJ that form at LC-TJ docking points in LC EpCAM cKO skin are not grossly abnormal and that, in addition, EpCAM does not appear to be required for LC uptake of surface proteins via TJ.

Figure 3. LC EpCAM is not required for uptake of external proteins by LC.

NHS-conjugated biotin was applied to the surface of tape-stripped skin containing control or EpCAM-deficient LC and LC-associated biotin was localized 16 h later using Alexa568-SA and confocal microscopy. (a) Biotin tracer was detected within dendrites that had penetrated TJ. Bars = 5 μ. (b) Internalization of biotin-tracer demonstrated in displays of single dendrites in various orientations as streaks of flourochrome (arrowheads) within dendrites below TJ. Bars = 1 μ.

LC EpCAM cKO mice mount enhanced cellular and humoral immune responses after topical immunization

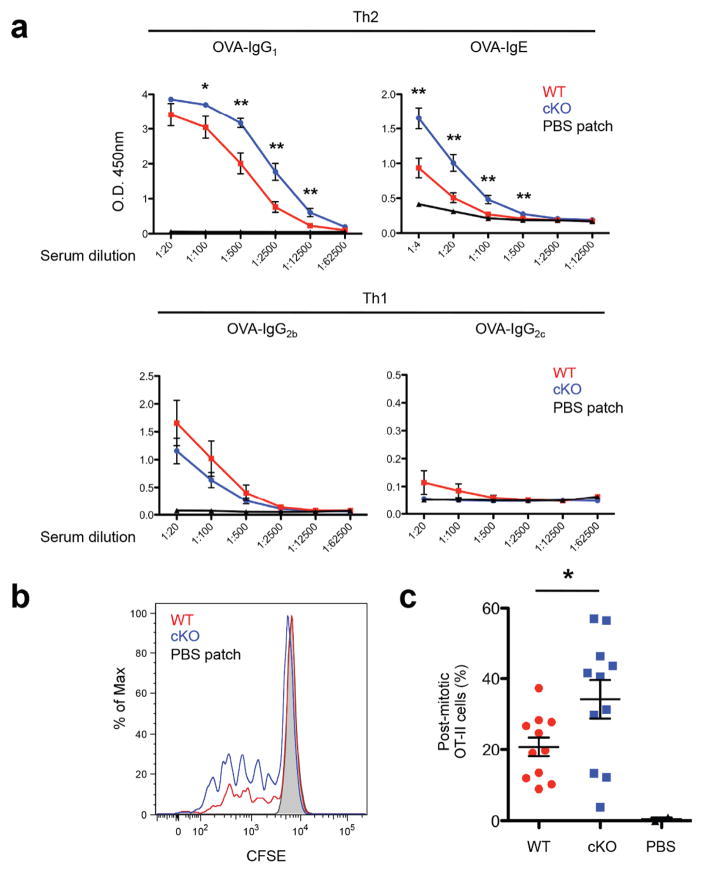

Epidermal LCs mediate T cell priming and Type 2 humoral immunity to foreign protein Ag that are applied to murine skin in the absense of adjuvant (Ouchi et al., 2011) (Nakajima et al., 2012). To determine if conditional deletion of EpCAM from LC had immunological consequences, we applied Ova to tape-stripped ear skin of control and LC EpCAM cKO mice using a modified patch immunization protocol (Ouchi et al., 2011). Anti-Ova antibodies were quantified in sera obtained 1 and 2 wk after the second weekly immunization. As reported previously (Ouchi et al., 2011) (Nakajima et al., 2012), application of Ova to the skin of control mice led to the preferential induction of Type 2-associated Ab (Figure 4a). Anti-Ova IgG1 was induced by 1 wk and anti-Ova IgE was induced by 2 wk. Relative to control mice, LC EpCAM cKO mice showed enhanced anti-Ova IgG1 responses at both time points and enhanced anti-Ova IgE responses at 2 wk (Figure 4a). Type 1 anti-Ova IgG2b Ab was detected at 2 wk and titers were comparable in control and LC EpCAM cKO mice (Figure 4a). Significant Type 1 anti-Ova IgG2c Ab was not detected at either time point or in either mouse strain (Figure 4a).

Figure 4. Enhanced humoral and cellular immune responses to topically applied antigen in LC EpCAM cKO mice.

(a) Serum Ova-specific IgG and IgE were quantified by ELISA 2 wk after topical immunization with Ova. Aggregate data from two independent experiments with a total of n=11 (WT and LC EpCAM cKO) or n=5 mice (PBS patch WT). * P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01 using the Student’s t test as indicated. (b, c) Antigen-specific T cell proliferation was measured by injecting CFSE-labeled OT-II cells into mice 4 days after topical Ova immunization, recovering them 2 days later and quantifying the amount of CFSE in individual CD4+ B220− Va2+ CD45.1+ T cells in skin draining LN. Results shown are from 1 of 2 representative experiments involving n = 11 (WT and LC EpCAM cKO) and n = 2 mice/group (PBS patch WT).

To determine if enhanced Ab responses in LC EpCAM cKO mice were accompanied by enhanced Th responses, we transferred naïve Ova-reactive CD4+ transgenic T cells (OT-II cells) into Ova patch-immunized mice and measured proliferation in skin draining LN several days later as a surrogate measurement of endogenous Th priming (Nakajima et al., 2012) (see Figure S3 for flow cytometry gating strategy). Significant numbers of OT-II cells proliferated in regional LN in an Ova-dependent fashion (as assessed by CFSE dilution and flow cytometry) (Figure 4b). Significantly more OT-II proliferation was observed in Ova-immunized LC EpCAM cKO mice than in controls treated analogously.

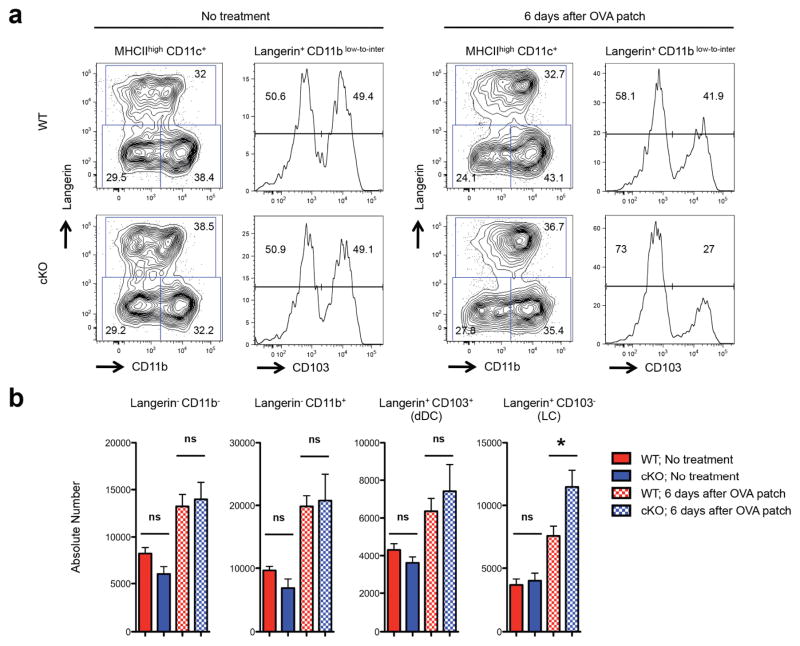

Topical immunization with protein antigen led to enhanced migration of EpCAM-deficient LCs to LN

The observation that enhanced Ab-forming responses and Ag-specific T cell proliferation occurred in LC EpCAM cKO mice suggested that more Ag was present in the LN of patch-immunized LC EpCAM cKO mice than in LN of patch-immunized control mice. This could occur if LC migration in the setting of patch immunization was enhanced in LC EpCAM cKO. To test this hypothesis, we assessed skin migratory DC in regional LN prior to and following Ova patch immunization in control and LC EpCAM cKO mice.

Skin-derived migratory DC (MHCIIhigh CD11cinter-to-high cells in skin draining LN) include four subsets that differentially express CD11b, Langerin (CD207) and CD103 (Poulin et al., 2007) (Bursch et al., 2007) (Henri et al., 2010). Langerin+ cells include Langerin+ CD103− migratory LC and Langerin+ CD103+ dermal DC. Langerin− migratory DC include CD11b+ cells as well as those that are CD11b− Langerin− and CD103−. At steady state, there were no differences in frequencies or absolute numbers of skin migratory DC subsets in LC EpCAM cKO mice as compared to those in controls (Figure 5a, 5b). After Ova patch immunization, we observed modest increases in LC frequencies and 1.5-fold increases in absolute LC numbers in draining LN from LC EpCAM cKO mice (Figure 5a, 5b). Levels of expression of CD86 and CD40 on migratory LC from control and LC EpCAM cKO mice were not different (Figure S4), suggesting that migratory LC were activated to similar extents in the two mouse strains. Frequencies and numbers of DC other than LC, including Langerin+ CD103+ dermal DC, were also not different in corresponding LN in control and LC EpCAM cKO mice. Importantly, we confirmed that EpCAM expression was selectively ablated in LC in LC EpCAM cKO mice while intermediate and indistinguishable levels of EpCAM were expressed by Langerin+ CD103+ dermal DC in both control and LC EpCAM cKO mice (Figure S5).

Figure 5. Exaggerated migratory activity of EpCAM-deficient LC during topical immunization.

(a) Flow cytometric profiles of the skin-derived migratory DCs (MHCIIhigh CD11cinter-to-high) present in skin draining LN from non-treated or Ova patch-immunized WT and EpCAM cKO mice. MHC IIhigh CD11cinter-to-high DCs were analyzed for the expression of Langerin, CD11b and CD103 using flow cytometry. Langerin+ CD103− DCs represent migratory LC while Langerin+ CD103+ DCs correspond to migratory dermal DCs. (b) Absolute numbers of lymph node DC prior to, and following, topical immunization with Ova. Aggregate data from four independent experiments with a total of n=8 mice/group (Ova-patched WT and LC EpCAM cKO) and n= 5 mice/group (non-treated WT and LC EpCAM cKO) is depicted. * P < 0.05 as determined by Student’s t test.

We also enumerated LCs in epidermis of control and LC EpCAM cKO mice on day 7 after OVA patch immunization or topical application of 2, 4-dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB). LC EpCAM cKO mice showed reduced numbers of LCs in epidermis in response to OVA patch immunization compared to control mice. These data are consistent with increased mobilization of EpCAM-deficient LCs from epidermis in response to topical immunization with protein antigen. Numbers of LCs in epidermis of LC EpCAM cKO mice and control mice were comparable 7 days after DNFB treatment (Figure S6). Of interest, baseline frequencies of LC in unperturbed epidermis in control and LC EpCAM cKO mice were also identical.

Apparent reduction in EpCAM expression by LC that are emigrating from epidermis

We previously reported that EpCAM is required for efficient migration of LC from skin that had been treated with strong contact sensitizers and from skin explants (Gaiser et al., 2012). We and others (Bobr et al., 2012), have also observed that LC that have migrated from skin under these circumstances express levels of EpCAM that are several-fold lower than unstimulated LC, although they remain very high. We attempted to assess effects of LC activation on EpCAM expression in patch immunization experiments by visualizing activated LC in situ. Whereas intraepidermal activated LC in patch-immunized skin routinely expressed high levels of surface-associated EpCAM, EpCAM was difficult to detect on the rare LC that were observed traversing the basement membrane (Figure S7). This is consistent with the enhanced LC migration and more efficient topical immunization that we observed in this study.

DISCUSSION

Expression of high levels of EpCAM by murine epidermal LC distinguishes them from other murine DC (Borkowski et al., 1996). Human LC do not express EpCAM, but they do express the closely related homolog TROP2 (Eisenwort et al., 2011). It seems likely that EpCAM and TROP2 play analogous roles in murine and human LC, respectively, and that the functions of these cell surface proteins are related to important and perhaps unique aspects of LC physiology. Because germ line EpCAM KO mice are not viable (Nagao et al., 2009b) (Guerra et al., 2012) (Lei et al., 2012), we generated EpCAM fl/fl mice that can be used to conditionally ablate EpCAM expression in LC and cells of other lineages (Gaiser et al., 2012). In the present study, we used LC EpCAM cKO mice to explore the role of LC EpCAM in immune responses to protein antigens that were applied to gently tape-stripped skin.

In the present study, we determined that expression of claudin-1, a TJ-associated protein, in LC was decreased in the absence of EpCAM. In epithelial cells, EpCAM physically associated with selected claudins (including claudin-1), and this prevented claudin-1 from being degraded in lysosomes (Wu et al., 2013). We propose that this mechanism is operative in LC, but we cannot address this issue directly. Interestingly, although levels of claudin-1 that were present in (or on) EpCAM-deficient LC were dramatically reduced, claudin-1 still accumulated at sites where EpCAM-deficient LC dendrites docked with epidermal TJ. Confocal microscopy did not allow us to determine if claudin-1 that was present in these structures was produced by keratinocytes or by LC. It is possible that claudin-1 that is associated with the tips of LC dendrites in LC EpCAM cKO mice is of LC origin since earlier studies in epithelial cells indicated that pools of claudin-1 that are TJ-associated and extra-junctional are metabolized differently (Wu et al., 2013).

The efficiencies with which dendrites of EpCAM-deficient LC and control LC docked with epidermal TJ did not differ and there were no obvious differences in the abilities of LC of the two genotypes to ingest labeled surface proteins. Additionally, LC EpCAM cKO and control skin was similarly impermeable to a small molecule (sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin) and a 27k Da protease (ETA). Unexpectedly, assessment of immune responses to topically applied Ova revealed enhancement of Ag-specific Type 2 (IgG1 and IgE) Ab responses and increased proliferation of adoptively transferred naïve Ova-reactive OT-II CD4 T cells in LC EpCAM cKO mice as compared to controls. Enhanced Th2 responses to topical Ova in LC EpCAM cKO mice cannot be attributed to increased LC frequency because quantification of epidermal LC in the present study did not reveal enhanced accumulation of LC in the epidermis of LC EpCAM cKO mice as was previously reported (Gaiser et al., 2012). We have been unable to identify technical or methodologic differences that could explain these findings, but we cannot exclude minor genetic drift or an unrecognized change in the microbiome associated with our mouse colony as potential explanations. Despite this, enumeration of skin-derived migratory DC in LN draining topical immunization sites in the present study revealed that there was a selective increase in the number of comparably activated migratory LC in LN of immunized EpCAM cKO mice relative to controls. LC in LC EpCAM cKO mice were also more effectively mobilized from epidermis in response to topical application of Ova than LC in control mice. The most straightforward interpretation of this result is that, in the protein Ag topical immunization model, the migratory capacity of EpCAM-deficient LC is enhanced as compared to that of control LC, and that the enhanced immune responses that we observed in LC EpCAM cKO mice can be attributed to increased delivery of Ag from epidermis to LN by LC. Our observation that infrequently identified LC that were in the process of traversing the basement membrane zone in the setting of topical protein immunization did not express high levels of EpCAM is consistent with the concept that enhanced LC migratory capacity is associated with decreased EpCAM expression.

The suggestion that the ability of activated EpCAM-deficient LC to migrate is enhanced in comparison to that of their EpCAM-expressing counterparts is, at least at first glance, inconsistent with our earlier report (Gaiser et al., 2012). We previously studied LC motility in contact allergen (TNCB)-treated epidermis of LC EpCAM cKO and control mice and quantified the ability LC to emigrate from epidermis in skin explants and after contact allergen-treatment in vivo. In these experiments, the ability of EpCAM-deficient LC to extend and retract their dendrites and to translocate within epidermis was decreased, as was their ability to migrate to regional LN. Potent contact allergens (and/or their vehicles) have an irritant (or adjuvant) component that is distinct from their ability to interact with endogenous proteins to form complete Ag, and that these chemicals are among the most potent activators of LC that have been studied. In contrast, the protocol that is used to induce immune responses to topically applied proteins does not involve the use of adjuvants. Ova preparations that we used for topical immunization did contain small amounts of endotoxin (800 EU/mg Ova), however. Approximately, 144 EU of endotoxin was applied topically to each immunization site. We do not know if topically applied endotoxin penetrates into the epidermis or if this amount of endotoxin is biologically significant but it is likely that similar amounts have been present in all purified protein preparations that have previously been used in topical immunization protocols. We determined that emigration of LCs from epidermis after topical application of Ova is enhanced in LC EpCAM cKO mice as compared to control mice. We propose that the activation state of LC, and/or perhaps surrounding keratinocytes, in contact allergen-treated skin is qualitatively or quantitatively different than that occurs in protein Ag-treated skin and that this relates to the seemingly paradoxical observations that we have made in two distinct experimental models.

It is not obvious how a single cell surface protein could have seemingly opposite effects on LC migration in different experimental settings. Recently, Maghzal and coworkers identified a novel mechanism through which EpCAM might regulate various aspects of cellular physiology (including intercellular adhesion and cell migration) that may be relevant (Maghzal et al., 2010) (Maghzal et al., 2013). These investigators determined that the intracellular domain of EpCAM is homologous to pseudo-substrate domains that are found in, and that inhibit the activity of, multiple members of the protein kinase C family by binding to enzyme active sites in the absence of PKC activators (Maghzal et al., 2013). In Xenopus skin explants, EpCAM bound to, and attenuated the activity of, PKCδ and regulated epidermal integrity – an endpoint that is dependent on maintenance of an appropriate balance between intercellular adhesion and cell motility/migration. Since EpCAM also bound to other PKC family members (Maghzal et al., 2013), one can envision that loss of EpCAM in different cells (or the same cell in different conditions) could result in very different phenotypes depending on the stimulus and particular serine/threonine kinase involved. PKC family members are known to regulate the actin-myosin cytoskeleton (Larsson, 2006) and highly controlled assembly and disassembly of this microfilament network is required for a variety of cell behaviors, including cell migration. We propose that activation of one or more PKC family members is differentially regulated by EpCAM in protein- and contact allergen-treated skin and that varied downstream effects on the cytoskeleton result in enhanced or inhibited LC migration.

Unfortunately, LC are not amenable to the kinds of biochemical or biological studies that would allow us to identify mechanisms that mediate EpCAM-dependent activities and potentially explain our experimental observations. To that end we are studying EpCAM in primary epithelial cells (Sato et al., 2009) and cell lines (Wu et al., 2013) that can be readily propagated and manipulated in vitro. After determining how EpCAM regulates epithelial cell physiology, we plan targeted experiments in which we confirm, or fail to confirm, that similar mechanisms relate to LC physiology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Experimental mice were generated and utilized as indicated in the supplementary materials. Procedures and study protocols were approved by the NCI animal care and use committee and conducted according to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Antibodies

Antibodies of interest were obtained from commercial sources and used in flow cytometric and immunofluorescence microscopy experiments as detailed in the supplementary materials

Visualization of epidermal TJ and LC-TJ docking sites

Epidermal TJ and LC-TJ docking sites were visualized in epidermal sheets as described previously (Kubo et al., 2013) and detailed in supplementary materials.

LC activation and protein uptake

Experiments involving LC activation and assessment of LC protein uptake were carried out as previously described (Kubo et al., 2009). See supplementary materials for details.

Immunization to topically-applied proteins

Topical (patch) immunization was performed as described previously (Ouchi et al., 2011) with modifications (see supplementary materials).

Quantification of Ova-specific Ab responses

Ova-specific Ab were measured in sera obtained 7 and 14 d after patch immunization as described in the supplementary materials.

In vivo measurement of antigen specific T cell proliferation

OT-II T cell proliferation was measured in protein patch immunized mice as described in the supplementary materials.

Characterization and enumeration of lymph node dendritic cells and epidermal LC

Lymph node dendritic cells and epidermal LC were enumerated in topically immunized mice as detailed in the supplementary materials.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- Ab

antibody

- Ag

antigen

- DC

dendritic cell

- EpCAM

Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule

- KO

knockout

- LC

Langerhans cell

- LN

lymph node

- MHCII

MHC class II antigen

- Ova

ovalbumin

- SG

stratum granulosum

- TJ

tight junction

- WT

wild type/control

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

CONTRIBUTIONS

T.O. and M.C.U. conceived experiments, T.O. performed most of the experiments, G.N. analyzed activation marker of DCs upon topical immunization with OVA and T.O. and M.C.U. wrote the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allan RS, Smith CM, Belz GT, van Lint AL, Wakim LM, Heath WR, et al. Epidermal viral immunity induced by CD8alpha+ dendritic cells but not by Langerhans cells. Science. 2003;301:1925–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1087576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amagai M, Matsuyoshi N, Wang ZH, Andl C, Stanley JR. Toxin in bullous impetigo and staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome targets desmoglein 1. Nat Med. 2000;6:1275–7. doi: 10.1038/81385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnden MJ, Allison J, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Defective TCR expression in transgenic mice constructed using cDNA-based alpha- and beta-chain genes under the control of heterologous regulatory elements. Immunol Cell Biol. 1998;76:34–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1998.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzar M, Winter MJ, de Boer CJ, Litvinov SV. The biology of the 17-1A antigen (Ep-CAM) J Mol Med. 1999;77:699–712. doi: 10.1007/s001099900038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett CL, van Rijn E, Jung S, Inaba K, Steinman RM, Kapsenberg ML, et al. Inducible ablation of mouse Langerhans cells diminishes but fails to abrogate contact hypersensitivity. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:569–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200501071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobr A, Igyarto BZ, Haley KM, Li MO, Flavell RA, Kaplan DH. Autocrine/paracrine TGF-beta1 inhibits Langerhans cell migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:10492–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119178109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkowski TA, Nelson AJ, Farr AG, Udey MC. Expression of gp40, the murine homologue of human epithelial cell adhesion molecule (Ep-CAM), by murine dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:110–4. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursch LS, Wang L, Igyarto B, Kissenpfennig A, Malissen B, Kaplan DH, et al. Identification of a novel population of Langerin+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3147–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenwort G, Jurkin J, Yasmin N, Bauer T, Gesslbauer B, Strobl H. Identification of TROP2 (TACSTD2), an EpCAM-like molecule, as a specific marker for TGF-beta1-dependent human epidermal Langerhans cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:2049–57. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaiser MR, Lammermann T, Feng X, Igyarto BZ, Kaplan DH, Tessarollo L, et al. Cancer-associated epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM; CD326) enables epidermal Langerhans cell motility and migration in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E889–97. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117674109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra E, Lattanzio R, La Sorda R, Dini F, Tiboni GM, Piantelli M, et al. mTrop1/Epcam knockout mice develop congenital tufting enteropathy through dysregulation of intestinal E-cadherin/beta-catenin. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henri S, Poulin LF, Tamoutounour S, Ardouin L, Guilliams M, de Bovis B, et al. CD207+ CD103+ dermal dendritic cells cross-present keratinocyte-derived antigens irrespective of the presence of Langerhans cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:189–206. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igyarto BZ, Haley K, Ortner D, Bobr A, Gerami-Nejad M, Edelson BT, et al. Skin-resident murine dendritic cell subsets promote distinct and opposing antigen-specific T helper cell responses. Immunity. 2011;35:260–72. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igyarto BZ, Kaplan DH. Antigen presentation by Langerhans cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25:115–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob T, Ring J, Udey MC. Multistep navigation of Langerhans/dendritic cells in and out of the skin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:688–96. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.118797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan DH. In vivo function of Langerhans cells and dermal dendritic cells. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:446–51. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan DH, Jenison MC, Saeland S, Shlomchik WD, Shlomchik MJ. Epidermal langerhans cell-deficient mice develop enhanced contact hypersensitivity. Immunity. 2005;23:611–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan DH, Kissenpfennig A, Clausen BE. Insights into Langerhans cell function from Langerhans cell ablation models. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2369–76. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan DH, Li MO, Jenison MC, Shlomchik WD, Flavell RA, Shlomchik MJ. Autocrine/paracrine TGFbeta1 is required for the development of epidermal Langerhans cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2545–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kautz-Neu K, Noordegraaf M, Dinges S, Bennett CL, John D, Clausen BE, et al. Langerhans cells are negative regulators of the anti-Leishmania response. J Exp Med. 2011;208:885–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H, Nagao K, Kubo A, Hata T, Shimizu A, Mizuno H, et al. Altered stratum corneum barrier and enhanced percutaneous immune responses in filaggrin-null mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1538–46. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissenpfennig A, Henri S, Dubois B, Laplace-Builhe C, Perrin P, Romani N, et al. Dynamics and function of Langerhans cells in vivo: dermal dendritic cells colonize lymph node areas distinct from slower migrating Langerhans cells. Immunity. 2005;22:643–54. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo A, Nagao K, Amagai M. 3D visualization of epidermal Langerhans cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;961:119–27. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-227-8_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo A, Nagao K, Yokouchi M, Sasaki H, Amagai M. External antigen uptake by Langerhans cells with reorganization of epidermal tight junction barriers. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2937–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladwein M, Pape UF, Schmidt DS, Schnolzer M, Fiedler S, Langbein L, et al. The cell-cell adhesion molecule EpCAM interacts directly with the tight junction protein claudin-7. Exp Cell Res. 2005;309:345–57. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson C. Protein kinase C and the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. Cell Signal. 2006;18:276–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Z, Maeda T, Tamura A, Nakamura T, Yamazaki Y, Shiratori H, et al. EpCAM contributes to formation of functional tight junction in the intestinal epithelium by recruiting claudin proteins. Dev Biol. 2012;371:136–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvinov SV, Velders MP, Bakker HA, Fleuren GJ, Warnaar SO. Ep-CAM: a human epithelial antigen is a homophilic cell-cell adhesion molecule. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:437–46. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.2.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maetzel D, Denzel S, Mack B, Canis M, Went P, Benk M, et al. Nuclear signalling by tumour-associated antigen EpCAM. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:162–71. doi: 10.1038/ncb1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maghzal N, Kayali HA, Rohani N, Kajava AV, Fagotto F. EpCAM controls actomyosin contractility and cell adhesion by direct inhibition of PKC. Dev Cell. 2013;27:263–77. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maghzal N, Vogt E, Reintsch W, Fraser JS, Fagotto F. The tumor-associated EpCAM regulates morphogenetic movements through intracellular signaling. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:645–59. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merad M, Ginhoux F, Collin M. Origin, homeostasis and function of Langerhans cells and other langerin-expressing dendritic cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:935–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao K, Ginhoux F, Leitner WW, Motegi S, Bennett CL, Clausen BE, et al. Murine epidermal Langerhans cells and langerin-expressing dermal dendritic cells are unrelated and exhibit distinct functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3312–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807126106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao K, Zhu J, Heneghan MB, Hanson JC, Morasso MI, Tessarollo L, et al. Abnormal placental development and early embryonic lethality in EpCAM-null mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima S, Igyarto BZ, Honda T, Egawa G, Otsuka A, Hara-Chikuma M, et al. Langerhans cells are critical in epicutaneous sensitization with protein antigen via thymic stromal lymphopoietin receptor signaling. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1048–55. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouchi T, Kubo A, Yokouchi M, Adachi T, Kobayashi T, Kitashima DY, et al. Langerhans cell antigen capture through tight junctions confers preemptive immunity in experimental staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2607–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin LF, Henri S, de Bovis B, Devilard E, Kissenpfennig A, Malissen B. The dermis contains langerin+ dendritic cells that develop and function independently of epidermal Langerhans cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3119–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, van de Wetering M, Barker N, Stange DE, et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell U, Cirulli V, Giepmans BN. EpCAM: structure and function in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1828:1989–2001. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler G, Steinman RM. Murine epidermal Langerhans cells mature into potent immunostimulatory dendritic cells in vitro. J Exp Med. 1985;161:526–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.3.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seneschal J, Jiang X, Kupper TS. Langerin+ dermal DC, but not Langerhans cells, are required for effective CD8-mediated immune responses after skin scarification with vaccinia virus. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:686–94. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley JR, Amagai M. Pemphigus, bullous impetigo, and the staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1800–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzpis M, McLaughlin PM, de Leij LM, Harmsen MC. Epithelial cell adhesion molecule: more than a carcinoma marker and adhesion molecule. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:386–95. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter MJ, Nagelkerken B, Mertens AE, Rees-Bakker HA, Briaire-de Bruijn IH, Litvinov SV. Expression of Ep-CAM shifts the state of cadherin-mediated adhesions from strong to weak. Exp Cell Res. 2003;285:50–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CJ, Mannan P, Lu M, Udey MC. Epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) regulates claudin dynamics and tight junctions. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:12253–68. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.457499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Kubo A, Fujita H, Yokouchi M, Ishii K, Kawasaki H, et al. Distinct behavior of human Langerhans cells and inflammatory dendritic epidermal cells at tight junctions in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:856–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli SC, Hauser C. Langerhans cells and lymph node dendritic cells express the tight junction component claudin-1. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2381–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.