Abstract

Purpose

Existing literature indicates that acceptance of dating violence is a significant and robust risk factor for psychological dating abuse perpetration. Past work also indicates a significant relationship between psychological dating abuse perpetration and poor mental health. However, no known research has examined the relationship between acceptance of dating violence, perpetration of dating abuse, and mental health. In addition to exploring this complex relationship, the current study examines whether psychological abuse perpetration mediates the relationship between acceptance of dating violence and mental health (i.e., internalizing symptoms of depression, anxiety, and hostility).

Methods

Three waves of longitudinal data were obtained from 1,042 ethnically diverse high school students in Texas. Participants completed assessments of psychological dating abuse perpetration, acceptance of dating violence, and internalizing symptoms (hostility, and symptoms of anxiety and depression).

Results

As predicted, results indicated that perpetration of psychological abuse was significantly associated with acceptance of dating violence and all internalizing symptoms. Furthermore, psychological abuse mediated the relationship between acceptance of dating violence and internalizing symptoms.

Conclusions

Findings from the current study suggest that acceptance of dating violence is an important target for the prevention of dating violence and related emotional distress.

Implications and Contribution

Study findings indicate that perpetration of psychological abuse is significantly associated with acceptance of dating violence and select mental health variables (i.e., anxiety, depression, hostility). Moreover, psychological abuse perpetration mediated the relationship between acceptance of dating violence and internalizing symptoms. To be effective in preventing mental health problems, interventions may benefit from targeting acceptance and perpetration of dating violence.

Keywords: dating violence, psychological abuse, mental health, adolescents, acceptance, longitudinal

Teen dating violence (TDV), which includes acts of physical violence, psychological abuse, and sexual aggression occurring in the context of an adolescent romantic relationship, is a prevalent and serious problem. Of particular concern is that dating violence in adolescence may establish a maladaptive pattern of relating that persists into adulthood.1,2 Extant research has estimated that TDV occurs in up to one third of adolescent relationships,3 with psychological abuse being more prevalent than physical violence.4 In addition, research has suggested that adolescents are more likely than adults to report mutual TDV, where both members of the couple perpetrate and are victims of violence.5,6 Consequences associated with TDV are potentially severe,1 including suicidality,7 risky sexual behaviors,8 psychological distress,4 mental health symptomatology,5,6 and future intimate partner violence.1,4,9

An extensive body of literature has explicated risk factors for TDV perpetration in an attempt to aid with prevention and reduce negative outcomes.9 However, relatively little is known about the negative consequences of psychological abuse perpetration. Identifying negative outcomes of TDV perpetration is important, as the risk factors for and consequences of TDV are often the same. Thus, identifying and preventing these negative outcomes could ultimately reduce adolescents’ future engagement in dating violence. Acceptance of dating violence and mental health are among the most commonly cited risk factors and consequences of TDV (e.g., see review by Dardis, Dixon, Edwards, & Turchik10). Thus, one potentially important relationship to examine is whether the perpetration of psychological aggression mediates the relationship between acceptance of dating violence (the risk factor) and mental health symptomatology (the outcome). Investigating psychological abuse perpetration is of particular importance as most existing research focuses on physical violence perpetration.11

Acceptance of Dating Violence

Research has consistently supported a significant relationship between the acceptance and perpetration of TDV.2,12 Indeed, acceptance of dating violence is an important mediator in the relationship between known risk factors (e.g., family violence) and TDV perpetration.2,12 For instance, Reyes and colleagues12 found that adolescents who experienced family violence were more likely to develop attitudes accepting of dating violence, anger dysregulation, and depression, which ultimately led to an increased risk for perpetrating physical TDV over time. In addition, Foshee and colleagues13 demonstrated that acceptance of dating violence helped explain the association between specific demographic variables, and moderate and severe physical TDV perpetration. Although this research generally focuses on physical TDV perpetration, it is likely that a significant relationship between acceptance of dating violence and perpetration of psychological abuse exists. This notion is strengthened by research demonstrating that psychological abuse often precedes and potentially contributes to physical TDV.2 The current study addresses this proposed relationship.

Mental Health

Mental health is a well-documented risk factor for and consequence of TDV perpetration.14 Similar to research examining the relation between acceptance and perpetration of TDV, research examining the link between TDV perpetration and mental health primarily focuses on physical violence perpetration. In a recent meta-analysis, Birkley and Eckhardt15 found that intimate partner violence perpetration was moderately related to hostility and internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression). Specific to TDV perpetration, research suggests that adolescents who have a history of child maltreatment, delinquency, violence, and violent crimes are more likely to have co-occurring depression and other internalizing symptoms and more likely to be physically aggressive against dating partners and peers.16 As an example, adolescents who witness their parents engage in marital violence are more likely to experience depression, and ultimately perpetrate greater physical TDV than are adolescents who did not witness family violence.16 Depressed affect in particular has been found to be both a consequence of and risk factor for TDV perpetration. Indeed, longitudinal studies and a review of the literature have demonstrated depressive symptoms to be associated with later perpetration of physical TDV.10,14,17

With few exceptions,17 limited research directly examines the relationship between TDV perpetration and anxiety. One study found that adolescent female perpetrators of TDV were more likely to report higher global internalizing symptoms (i.e., a sum of symptoms of anxiety, depression, and withdrawal).18 In adult and college samples, research has supported a significant relation between anxiety and intimate partner violence perpetration.11

Hostility has been found to differentiate perpetrators of TDV from non-perpetrators, such that the former report significantly more hostility.19 It may be that adolescents who experience violence (e.g., child maltreatment, bullying, prior TDV) during early childhood might develop more hostile attitudes and views of the world, ultimately leading them to engage in aggressive acts (e.g., TDV perpetration).20 Boivin and colleagues21 examined the relations among prior TDV victimization, hostility, and future TDV perpetration. Results indicated that girls who experienced sustained TDV were more likely to report high levels of hostility and ultimately increased TDV perpetration. Results suggest that girls might develop more hostile attitudes in response to prior victimization, which is associated with future perpetration. For boys, on the other hand, the relationship between prior victimization and future perpetration was mediated by overall emotional distress (e.g., anxiety, depression, and hostility). That is, boys who experienced sustained violence victimization were more likely to experience increased emotional distress, which was associated with future violence perpetration. The current study, by considering internalizing symptoms associated with perpetrating TDV, addresses an important gap in the literature and acknowledges that poor mental health can be both a risk factor for and a consequence of TDV perpetration.

In sum, existing research has established a significant relationship between internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, and hostility) and physical TDV perpetration, with fewer studies examining the link between psychological abuse perpetration and psychopathology. Further, these studies have primarily examined mental health as a risk factor for TDV perpetration rather than as a consequence of such. Examining internalizing symptoms as a consequence of TDV perpetration is of particular importance in adolescent samples, as research has demonstrated that partner violence emerges during adolescence and persists into adulthood. It is possible that emotional distress might be an important consequence of adolescent TDV perpetration, which might ultimately be a risk factor for continued partner violence perpetration.

Theory

Numerous interpersonal theories of violence have emerged, which posit that internal factors of the perpetrator (e.g., acceptance of dating violence) increase the risk of TDV.15 Of particular note is social learning theory, which suggests that the perpetration of dating violence develops through the basic learning constructs of classical and operant conditioning, as well as observational learning. According to this model, experiences in early childhood (exposure to violence, acceptance of violence) contribute to future TDV, which is ultimately associated with negative outcomes (e.g., internalizing symptoms).15

Bell and Naugle22 proposed a comprehensive theoretical model of intimate partner violence, which posits that multiple contextual factors (e.g., acceptance and exposure to violence, demographic variables) contribute to TDV or adult partner violence, which ultimately results in negative consequences (e.g., poor health) that are associated with continued TDV. According to this model, acceptance of dating violence is a proximal, contextual factor that likely emerges from background experiences (e.g., exposure to violence in family) and that is associated with TDV perpetration. In turn, acceptance and perpetration of TDV results in reduced mental health, which may ultimately be associated with future violence perpetration. In addition, the dynamic developmental systems theory is a comprehensive theoretical model that proposes that dating violence is a result of the interaction of three factors: (1) contextual/background factors (e.g., exposure to violence in the family of origin); (2) developmental/internal factors (e.g., acceptance of dating violence); and (3) relationship influences.15 Based on this theory, adolescents who experience family violence might develop accepting attitudes about partner violence, which may make them more susceptible to increased stress and conflict within intimate relationships and ultimately to an increased likelihood for perpetrating TDV. As a result of this perpetration, the adolescent is likely to experience negative outcomes (e.g., poor mental health), which might prompt the continued use of aggression in dating relationships.

Current Study

Research examining the relations among acceptance of dating violence, psychological abuse perpetration, and mental health is sorely needed as the vast majority of research on TDV focuses on physical violence. Risk factors for and consequences of psychological abuse perpetration are important to identify and understand, as the frequency and rate of psychological abuse remains stable and constant across the lifespan and is a robust predictor of physical violence.2,11 Thus, examining whether psychological abuse perpetration mediates the relationship between acceptance of dating violence and internalizing symptoms will help elucidate the complex problem of TDV, and potentially identify targets for intervention. We hypothesize that 1) acceptance of dating violence will predict psychological abuse perpetration over the next year, and 2) psychological abuse perpetration will mediate the relationship between acceptance of dating violence and internalizing symptoms.

Method

Procedure and Participants

Waves 1 (Spring 2010), 2 (Spring 2011), and 3 (Spring 2012) of an ongoing 6-year longitudinal study were used23 to test the proposed model. Participants were 1,042 adolescents from multiple public high schools in Texas (response rate=62%; higher than the generally accepted response rate of 60%24). Students received a $10 gift card for completing each wave of questionnaires. At Wave 1, students were 56% female with a mean age of 15.1 (SD=0.79), self-identified as Hispanic (31%), White (29%), African American (28%), Asian/Pacific islander (4%) or other (8%), and were in the 9th (75%) or 10th (25%) grade. All procedures were approved by the first author’s Institutional Review Board. Active parental consent was obtained prior to data collection. Retention was 93% at Wave 2 and 86% at Wave 3 (93% from Wave 2 to Wave 3).

Measures

Acceptance of dating violence (Wave 1)

Adapted from Foshee and colleagues,25 students responded to the following 5 items on a 4-point scale anchored by strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4): “Violence between dating partners can improve the relationship.”, “There are times when violence between dating partners is okay.”, “Sometimes violence is the only way to express your feelings.”, “Some couples must use violence to solve their problem.”, “Violence between dating partners is a personal matter and people should not interfere”. This scale, developed for adolescents has been shown to be reliable25 (for the current study, Cronbach’s α=.82).

Psychological abuse perpetration (Wave 2)

Ten yes/no items from the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationship Inventory (CADRI)26 were used to measure psychological abuse (e.g., “I ridiculed or made fun of him/her in front of others”; “ I kept track of who he/she was with and where he/she was”). Items were summed (1 = never perpetrated psychological abuse against partner, 11 = perpetrated all types of psychological abuse against partner) to make a composite variable. The CADRI was normed on an adolescent sample and has consistently been shown to be a valid and reliable measure of teen dating violence26 (Cronbach’s α=.74).

Hostility (Wave 3)

Given prior literature linking hostility to partner violence, participants responded to the following five items from the SCL-90 Hostility subscale27 using a four-point scale anchored by never (1) and most of the time (4): In general, how often do you, 1) “have temper outbursts you can’t control?”, 2) “have urges to beat, injure, or harm someone?”, 3) “have urges to break or smash things?”, 4) “get into frequent arguments?”, and 5) “Shout or throw things?”. Previous studies have demonstrated the reliability and validity of this measure28 (Cronbach’s α=.83).

Depression symptoms (Wave 3)

Six items from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Short Depression Scale29 were used to measure past-week depression symptoms. Participants responded to the following items on a four-point scale anchored by less than 1 day (1) and 5–7 days (4): “I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing.”, “I felt depressed.”, “I felt fearful.”, “My sleep was restless.”, “I was happy.”(re-coded), “I felt lonely.”, “I could not “get going.” Versions of the CES-D are widely used in research, has demonstrated good reliability and validity, and has been used with adolescents30 (Cronbach’s α=.79).

Anxiety symptoms (Wave 3)

Using a three-point scale anchored by not true (1) and very true (3), symptoms of anxiety were measured with the following five items from the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders31: “I am nervous.”, “I worry about being as good as other kids.”, “I worry about things working out for me.”, “I am a worrier.”, “People tell me that I worry too much”. This widely used scale has demonstrated acceptable convergent and discriminant validity32 (Cronbach’s α=.85.

Data Analytic Plan

Primary hypotheses were tested with Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in Mplus 7.11. To handle missingness in longitudinal data, full information maximum likelihood method was used. FIML estimation provides less biased and more efficient estimations even when not missing at random.33 Because of the ordered categorical nature of the items, a mean and variance adjusted weighted-least squares estimation method (WLSMV) was employed to obtain parameter estimates and standard errors for the SEM. Model fit is evaluated as being acceptable when using root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)34 of < .0635 and a comparative fit index (CFI),34 Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) of ≥ .95.35,36 To test the potential mediation effect of perpetrating psychological abuse, indirect command with 5,000 bootstrap samples and 95% biased-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) was applied. This method corrects bias of significance in mediation tests.37

Several demographic factors, such as gender (1=female and male=0); parent education (1=did not graduate from high school and 4=finish college); three dummy-coded variables regarding ethnicity (White=1 vs. all other ethnicities=0, Hispanic=1 vs. all other ethnicities=0, or African American=1 vs. all other ethnicities=0); lifetime psychological abuse perpetration (1=at least once and 0=never); the number of lifetime dating partners (1=1; 5=5+), exposure to mother-to-father violence (1=never and 4=more than 20 times), and exposure to father-to-mother violence (1=never and 4=more than 20 times), and Wave 1 symptoms of hostility, anxiety, and depression were included as control variables.

Results

Bivariate correlations, means, and standard deviations are shown in Table 1. SEM revealed that a mediation model fit the data well, χ2[499]=1106.9, p<.05; RMSEA=0.03, 95% CI=.027, .034; CFI=.96, TLI=.96. The model explained 23% of the variance in psychological abuse perpetration, 32% of the variance in hostility, 28% of the variance in depression symptoms, and 30% of the variance in anxiety symptoms, once taking into account all covariates. Female (b=.83, SE=0.41), African American (b=.88, SE=0.40), lifetime psychological abuse perpetration (b=1.70, SE=0.23), and hostility (b=.40, SE=0.17) at Wave 1 were positively related with psychological abuse perpetration at Wave 2. In addition, being female was negatively related to hostility (b= −.18, SE=0.07) but positively associated with anxiety (b=.15, SE=.07) at Wave 3. Being Hispanic was negatively related to hostility (b=−0.27, SE=.12) and symptoms of depression (b=−.24, SE=0.10) at Wave 3. Being African American was negatively associated with depression (b=−0.23, SE=.10) at Wave 3. Being White was negatively associated with hostility (b=−0.21, SE=.10) and symptoms of anxiety (b=−0.34, SE=.11) at Wave 3. Internalizing psychopathology at Wave 1 was positively related reporting these symptoms at Wave 3 (hostility, b=.61, SE=.07, depression, b=.42, SE=.07, anxiety, b=.69, SE=.10). The remaining covariates were not significantly associated with any of the mediator or outcome variables at Wave 3.

Table 1.

Mean, Standard Deviation, Internal Consistency and Correlation among variables

| Mean | SD | GACV | PTDVP | Hostility | Depression | Anxiety | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GACV | 1.40 | 0.52 | |||||

| PTDVP | 4.23 | 2.73 | 0.14*** | ||||

| Hostility | 1.67 | 0.62 0. | 12*** | 0.31*** | |||

| Depression | 1.83 | 0.66 | 0.06* | 0.31*** | 0.45*** | ||

| Anxiety | 2.01 | 0.56 | −0.01 | 0.26*** | 0.26*** | 0.47*** |

Note. GACV = General acceptance of couple violence, PTDVP = Psychological Teen Dating Violence Perpetration.

p < .05,

p < .001

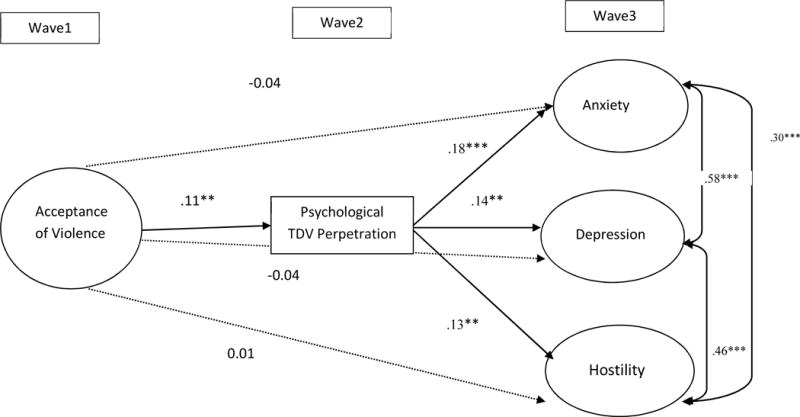

As expected (Figure 1), acceptance of dating violence was positively related to psychological abuse perpetration, b=0.38, SE=0.13, p=.003, 95% confidence interval (CI) with bootstrapping method=0.13, 0.63, albeit with relatively small effect sizes. Psychological abuse perpetration was positively associated with symptoms of anxiety (b=0.06, SE=0.01, p<.001, 95% CI=0.03, 0.09), depression (b=0.04, SE=0.01, p=.002, 95% CI=0.01, 0.06), and hostility (b=0.04, SE=0.01, p=.004, 95% CI=0.01, 0.06). That is, the more youth accepted general couple violence, the more likely they were to perpetrate psychological abuse and, in turn, were more likely to report more symptoms of anxiety, depression, and hostility.

Figure 1.

Note. Path coefficients and correlations are completely standardized. Although not shown here, previous mental health, gender, and three dummy-coded ethnicities, parental education, interparental violence, the number of dating partners and previous psychological TDV perpetration history were included as covariates in the model. All significant (p <.05) paths are highlighted by boldface and marked by asterisks. * p < .05, **<.01, *** <.001

Discussion

Research has consistently demonstrated that acceptance of dating violence and emotional distress are both significant risk factors for and consequences of TDV perpetration. Moreover, comprehensive theoretical models of partner violence posit that multiple contextual factors (including acceptance of violence) contribute to violence, and result in poor mental health, which may then serve to perpetuate violence.22 However, no known studies have examined the link between acceptance of dating violence and emotional distress, nor have there been empirical investigations examining psychological abuse perpetration as a mediator of this link. Moreover, the bulk of TDV perpetration research has focused on physical forms of violence. Thus, the purpose of the current study was to examine whether dating violence acceptance leads to emotional distress for adolescents who perpetrate psychological abuse.

Consistent with our hypothesis, acceptance of dating violence at wave 1 was linked to psychological abuse perpetration at wave 2. This finding is consistent with previous research indicating that acceptance of dating violence is associated with and precedes TDV perpetration and indicates that adolescents who accept dating violence norms are at an increased risk for perpetrating abuse in their relationships.12 Furthermore, psychological abuse perpetration significantly predicted internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, and hostility). To date, limited research has directly examined the relationship between psychological abuse perpetration and anxiety; thus, this study adds to the literature by demonstrating that adolescents who perpetrate psychological abuse may experience anxiety as a result (in addition to hostility and symptoms of depression). The longitudinal nature of this study supports the temporal order to these variables. Moreover, the finding that psychological abuse perpetration is associated with and precedes depression and hostility is in line with existing literature,21 and further supports the notion that TDV perpetration may contribute to poor mental health, which ultimately could result in continued and future partner violence. In other words, adolescents who experience internalizing symptoms as a result of their partner violence might lack adequate coping and emotion regulation skills, thus ultimately contributing to additional TDV perpetration.

Our hypothesis that psychological abuse perpetration mediates the relationship between acceptance of dating violence and internalizing symptoms was supported. Findings suggest that adolescents who accept dating violence as a normative behavior are more likely to perpetrate psychological abuse. In turn, the perpetration of psychological abuse temporally predicted depression, anxiety, and hostility. This result provides support for the notion that acceptance of dating violence is a risk factor for negative psychological outcomes among adolescents who perpetrate psychological abuse. One potential explanation is that adolescents who accept dating violence might have been exposed to violence (e.g., child maltreatment, TDV victimization) or to environments in which violence is normative during early development. As a result of these earlier experiences and their attitudes towards dating violence, they may be more likely to engage in TDV, which in turn increases their psychological distress. A second potential reason for this relationship is that adolescents who both accept and engage in dating violence might experience peer and social rejection, which could contribute to psychological distress.12 Future research should unpack these potential explanations.

Implications and Directions for Future Research

While additional research is needed, there are a number of potentially important prevention and treatment implications. Results from the current study – especially the temporal nature of our findings – support the importance of targeting acceptance in TDV interventions.38 For example, the Families for Safe Dates prevention program has demonstrated significant reductions in acceptance of TDV.39 Thus, it is not just the act of violence that matters but how the act is processed. Given the significant relation between acceptance of dating violence and TDV perpetration, prevention programs should continue to target and attempt to alter attitudes about dating violence.

In addition, treatment for adolescents with a history of TDV perpetration would benefit from assessing psychological health and attitudes about dating violence. Mental health symptoms are a well-cited risk factor for and consequence of TDV perpetration.1 Thus, it is likely that adolescents with untreated emotional distress could perpetrate TDV in the future regardless of their reduced acceptance of dating violence. Interventions and treatments targeting multiple factors associated with TDV are more likely to lead to reductions in perpetration and victimization.40

This is the first known study that has examined psychological TDV perpetration as a mediator in the relation between acceptance of dating violence and symptoms of mental health, and continued research is needed to replicate these findings. While our focus on psychological abuse perpetration is relatively novel, future research should examine physical and sexual TDV perpetration as longitudinal mediators of the relationship between acceptance of dating violence and poor mental health. Finally, the current study focused on depression, anxiety, and hostility; however, there are additional mental health symptoms likely associated with psychological TDV perpetration, such as posttraumatic stress disorder and suicidality.

Limitations

While the large ethnically diverse sample, longitudinal design, and focus on psychological abuse are strengths, findings should be considered in light of several limitations. First, our study design did not account for high-risk adolescents who dropped out of school. Second, our findings are based on self-reports. Future research may benefit by using collateral sources or behavioral indicators to help reduce the influence of social desirability and recall bias. Third, despite comprising a large, ethnically diverse sample from a wide geographical area, findings may be limited to adolescents in southeast Texas. However, the current sample matches quite well with national samples on a range of behaviors.23

Despite these limitations, the current study used 3 waves/years of data from a large ethnically diverse sample to demonstrate that psychological abuse perpetration mediated the link between acceptance of dating violence and internalizing symptoms.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Award Number K23HD059916 (PI: Temple) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) and 2012-WG-BX-0005 (PI: Temple) from the National Institute of Justice (NIJ). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NICHD or NIJ. This work would not have been possible without the permission and assistance of the schools and school districts

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts: The authors have no conflicts to report

References

- 1.Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, Rothman E. Longitudinal Associations Between Teen Dating Violence Victimization and Adverse Health Outcomes. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):71–78. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy CM, O’Leary KD. Psychological aggression predicts physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1989;57(5):579. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hickman LJ, Jaycox LH, Aronoff J. Dating violence among adolescents prevalence, gender distribution, and prevention program effectiveness. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2004;5(2):123–142. doi: 10.1177/1524838003262332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jouriles EN, Garrido E, Rosenfield D, McDonald R. Experiences of psychological and physical aggression in adolescent romantic relationships: links to psychological distress. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33(7):451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Próspero M, Kim M. Mutual partner violence: mental health symptoms among female and male victims in four racial/ethnic groups. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24(12):2039–2056. doi: 10.1177/0886260508327705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volpe EM, Hardie TL, Cerulli C. Associations among depressive symptoms, dating violence, and relationship power in urban, adolescent girls. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2012;41(4):506–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olshen E, McVeigh KH, Wunsch-Hitzig RA, Rickert VI. Dating violence, sexual assault, and suicide attempts among urban teenagers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(6):539–545. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.6.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard DE, Wang MQ. Risk profiles of adolescent girls who were victims of dating violence. Adolescence. 2003;38(149):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banyard VL, Cross C. Consequences of teen dating violence: understanding intervening variables in ecological context. Violence Against Women. 2008;14(9):998–1013. doi: 10.1177/1077801208322058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dardis CM, Dixon KJ, Edwards KM, Turchik JA. An examination of the factors related to dating violence perpetration among young men and women and associated theoretical explanations: a review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2015;16(2):136–152. doi: 10.1177/1524838013517559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shorey RC, Temple JR, Febres J, Brasfield H, Sherman AE, Stuart GL. The Consequences of Perpetrating Psychological Aggression in Dating Relationships: A Descriptive Investigation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27(15):2980–2998. doi: 10.1177/0886260512441079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reyes HL, Foshee VA, Niolon PH, Reidy DE, Hall JE. Gender Role Attitudes and Male Adolescent Dating Violence Perpetration: Normative Beliefs as Moderators. J Youth Adolesc. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0278-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foshee VA, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Reyes HLM, et al. What accounts for demographic differences in trajectories of adolescent dating violence? An examination of intrapersonal and contextual mediators. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42(6):596–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ackard DM, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Long-term impact of adolescent dating violence on the behavioral and psychological health of male and female youth. J Pediatr. 2007;151(5):476–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birkley EL, Echardt C. Anger, hostility, internalizing negative emotions, and intimate partner violence perpetration: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;37:40–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCloskey L, Lichter E. The contribution of marital violence to adolescent aggression across different relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:390–412. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foshee VA, McNaughton Reyes HL, Ennett ST. Examination of sex and race differences in longitudinal predictors of the initiation of adolescent dating violence perpetration. Journal of aggression, maltreatment & trauma. 2010;19(5):492–516. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2010.495032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chase KA, Treboux D, O’leary KD. Characteristics of high-risk adolescents’ dating violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17(1):33–49. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leen E, Sorbring E, Mawer M, Holdsworth E, Helsing B, Bowen E. Prevalence, dynamic risk factors and the efficacy of primary interventions for adolescent dating violence: An international review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2013;18(1):159–174. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norlander B, Eckhardt C. Anger, hostility, and male perpetrators of intimate partner violence: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25(2):119–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boivin S, Lavoie F, Hébert M, Gagné MH. Past victimizations and dating violence perpetration in adolescence: the mediating role of emotional distress and hostility. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27(4):662–684. doi: 10.1177/0886260511423245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bell KM, Naugle AE. Intimate partner violence theoretical considerations: Moving towards a contextual framework. Clinical psychology review. 2008;28(7):1096–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Temple JR, Shorey RC, Fite P, Stuart GL, Vi Donna L. Substance Use as a Longitudinal Predictor of the Perpetration of Teen Dating Violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42(4):596–606. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9877-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson TP, Wislar MS. Response rates and nonresponse errors in surveys. JAMA. 2012;307:1805–1806. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foshee VA. Gender differences in adolescent dating abuse prevalence, types and injuries. Health Education Research. 1996;11(3):275–286. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfe DA, Scott K, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Wekerle C, Grasley C, Straatman AL. Development and validation of the conflict in adolescent dating relationships inventory. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13(2):277–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Derogatis LR. BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory: administration, scoring & procedures manual. National Computer Systems; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoe M, Brekke J. Testing the cross-ethnic construct validity of the Brief Symptom Inventory. Research on Social Work Practice. 2009;19(1):93–103. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradley KL, Bagnell AL, Brannen CL. Factorial validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression 10 in adolescents. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2010;31(6):408–412. doi: 10.3109/01612840903484105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Audrain-McGovern J, Lerman C, Wileyto EP, Rodriguez D, Shields PG. Interacting effects of genetic predisposition and depression on adolescent smoking progression. American J Psychiatry. 2004;161(7):1224–1230. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, et al. The screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): Scale construction and psychometric characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(4):545–553. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muris P, Merckelbach H, Ollendic T, King N, Bogie N. Three traditional and three new childhood anxiety questionnaires: Their reliability and validity in a normal adolescent sample. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2002;40(7):753–772. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newman D. Longitudinal modeling with randomly and systematically missing data: A simulation of ad hoc, maximum likelihood, and multiple imputation techniques. Organizational Research Methods. 2003;6:328–362. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Browne M, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of testing model fit. In: Bollen K, Long J, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kline R. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd. New York: The Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu L, Bentler P. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacKinnon DP, Luecken LJ. How and for whom? Mediation and moderation in health psychology. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2 Suppl):S99–S100. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ritchwood T, Albritton T, Akers A, et al. The effect of Teach One Reach One (TORO) on youth acceptance of couple violence. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0188-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foshee VA, McNaughton Reyes HL, Ennett ST, Cance JD, Bauman KE, Bowling JM. Assessing the effects of Families for Safe Dates, a family-based teen dating abuse prevention program. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(4):349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolfe DA, Crooks C, Jaffe P, et al. A School-Based Program to Prevent Adolescent Dating Violence A Cluster Randomized Trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163:692–699. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]