Abstract

Drop-in centers for homeless youth address basic needs for food, hygiene, and clothing, but can also provide critical services that address youth’s “higher-level” needs (e.g., substance use treatment, mental health care, HIV-related programs). Unlike other services that have restrictive rules, drop-in centers typically try to break down barriers and take a “come as you are” approach to engaging youth in services. Given their popularity, drop-in centers represent a promising location to deliver higher level services to youth that may not seek services elsewhere. A better understanding of the individual-level factors (e.g., characteristics of homeless youth) and agency-level factors (e.g., characteristics of staff and environment) that facilitate and impede youth engagement in drop-in centers will help inform research and outreach efforts designed to engage these at-risk youth in services. Thus, the goal of this review was to develop a preliminary conceptual model of drop-in center use by homeless youth. Towards this goal, we reviewed 20 available peer-reviewed papers and reports on the facilitators and barriers of drop-in center usage and consulted broader models of service utilization from both youth and adult studies to inform model development.

Background

Service Needs of Homeless Youth

For example, in a single night in 2014, nearly 39,000 unaccompanied youth under age 25 were homeless on the street [3]. Each year upwards of 550,000 youth in the U.S. under the age of 24 experience homelessness lasting one week or more [1-3]. These youth become homeless for a variety of reasons such as leaving their home without parental or guardian consent (“runaways”), being forced out of their home (“throwaways”), and aging out of the foster care system [2, 4-6]. Once they are out on the streets on their own, most of these homeless youth are in immediate need of basic services such as food, showers, and clean clothes, yet they also face a host of other challenges. As a result of both pre-existing conditions and their experiences on the streets, homeless youth tend to have multiple and interrelated service needs to address various health-related issues [7]. For example, nearly 75% are current substance users [8], and illicit drug use, needle use (and sharing), and prescription drug misuse are all common [9-14]. Homeless youth also engage in risky sexual behavior [11, 12, 14-17], and rates of HIV transmission [18] and pregnancy [19] are both substantially higher among homeless than housed youth. It is estimated that more than half of homeless youth have one or more mental health disorders, with depression being the most common [20]. In addition, homeless youth report poor nutrition and a range of physical health problems [21, 22], as well as limited education and employment options [23, 24]. Clearly, the service needs of homeless youth are many and varied, expanding beyond the pressing need of securing safe and stable housing.

Drop-in Centers for Homeless Youth

Drop-in centers (sometimes called “access centers”) provide an invaluable safety net for homeless youth by helping them meet both basic needs (e.g., food, hygiene, clothing), as well as “higher-level” needs such as substance use treatment and mental health care, HIV-related programs, individual and group counseling, independent living skills and job training, and school drop-out prevention [25, 26]. These centers are typically funded by private donations (e.g., both of resources and staff time), donations from charitable organizations, and federal and state grants [27, 28]. Unlike shelters that have restrictive rules that youth must follow (e.g., curfews, abstinence from substances), drop-in centers typically try to break down barriers and take a “come as you are” approach to engaging youth in services [28]. This can be quite appealing to homeless youth, many of whom prefer “camping out” (e.g., sleeping in a park or street) over staying in shelters [29].

Homeless youth are more than twice as likely to use drop-in centers than shelters, and both are used more often than other services for medical, substance use, and mental health needs [30]. Researchers surveying 249 youth recruited from shelters and the street in three Midwestern cities found that youth are most likely to report use of outreach services typical to drop-in centers, such as food programs and street outreach, than other services like shelters and counseling services [31]. In a sample of 83 homeless youth interviewed in Chicago, IL and Los Angeles, CA, researchers found that the majority of youth used drop-in centers (58%) or food programs (54%), while less than half used counseling centers (40%) or shelters (36%) [32]. Importantly, those who access substance use, mental health, and case management services at drop-in centers demonstrate significant reductions in substance use, improvements in mental health, and greater housing stability over time compared to those who do not use these services [33]. Drop-in centers are often a youth’s initial resource for services after leaving home, which puts drop-in centers in the unique position to help youth transition to more formal services to meet their needs. They can be an important point of contact for youth that may not seek services elsewhere.

Despite the potential benefits of drop-in centers for addressing the needs of homeless youth, the barriers and facilitators of youth engagement in these centers are unclear. A better understanding of why youth do and do not use drop-in centers will help to shape policy that can better address the health needs of homeless youth. Knowledge gained through the development of a conceptual model of barriers and facilitators of drop-in center use can guide future research efforts in this area by providing a framework for researchers to develop and test the short- and long-term effectiveness of interventions to address gaps in service needs. A model for drop-in center use could also help researchers and outreach workers develop strategies to encourage homeless youth who have only sought basic services to take advantage of higher level services that may be needed to address their health, education, employment, and housing needs.

Purpose of Review

In 2013, the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness called for better intervention models and outreach efforts to meet the unique needs of homeless youth [34], and one of the major strategies to end homelessness among youth endorsed by the federal government is utilization of the types of higher level services drop-in centers offer [35]. The present review responds to these national research priorities by identifying facilitators and barriers to drop-in center service use among homeless adolescents and young adults and developing a conceptual model that synthesizes the evidence found. The conceptual model builds on a broader model of service utilization, the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations [36], which has been applied to health care service use among vulnerable adolescents [37]. This model can be used to inform research and outreach efforts with homeless youth.

Method

Literature Search Strategy

The search strategy followed a three-stage process. First, we generated two key questions to guide the selection of initial search terms, inform decisions on the inclusion and exclusion criteria of studies, and provide a framework for the review: (1) What are the facilitators and barriers of drop-in center utilization among homeless youth? and (2) What models of drop-in service utilization exist in the research literature for homeless youth? To locate articles for the literature review, we performed comprehensive Internet searches for a broad range of search terms related to the subject from 1990 to 2015 using five databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, Social Services Abstracts, Social Sciences Abstracts, and Sociological Abstracts. Keywords used to identify drop-in centers included all terms related to the phrase “drop-in” (or “drop in”) and “access center;” keywords for homelessness were all terms containing “homeless,” “run-away,” or “run-away.” To locate studies on homeless youth with a targeted age of 13 to 25 years old, we additionally included population search terms for youth such as “adolescent,” “child,” “young adult,” or “youth.”

The literature search generated 147 unique published articles, reports, reviews, and dissertations. The first two authors independently coded the articles based on titles and abstracts to determine if they were clearly related or unrelated to our key questions. We had discrepant codes for 19 (13%) of these articles and, through discussion, resolved whether to include or exclude them. Forty-four studies were determined to be clearly related to our key questions and advanced to the second stage. Most articles excluded at this stage simply recruited participants from a drop-in center and did not focus specifically on service utilization.

For the second stage, we independently coded the 44 articles based on titles, abstracts, and full text review on two key questions: (1) Does this article focus specifically on homeless youth? and (2) Does this article address the question of why homeless youth use or do not use drop-in center services? Articles that met both criteria were categorized as “Youth” articles (those primarily focusing on youth factors associated with drop-in center utilization), “Agency” articles (those primarily focusing on agency/staff factors associated with drop-in center utilization or studies describing a drop-in center delivery model), or “Both.” Some articles focused on general use of services (e.g., formal medical services in addition to drop-in center services) and did not specify in all cases if findings reported were specific to drop-in centers. Thus, we only included articles where it was clear that drop-in centers were specified in survey materials or interview questions given to youth or service staff. We also included articles that did not specifically use the term “drop-in center,” but instead referenced “outreach services” that were clearly drop-in center sites from a close read of the article. During this second stage, studies were included if they (1) were conducted within the U.S. and Canada (given heterogeneity in homeless populations and service delivery models outside of North America), (2) included youth (approximately ages 13 to 25), and (3) looked specifically at drop-in service use. Articles were excluded if: (a) they were not relevant/were outside the scope of this review; (b) recruited subjects from a drop-in center for an intervention evaluation, but did not focus on use of the drop-in services specifically (for example [33, 38, 39]); and (c) provided guidance on establishing drop-in centers via anecdotal descriptions or protocols for drop-in center set-ups, such as details related to finding funding, building space, and internal organization of the center (for example [26, 28, 40]). We resolved 4 discrepant inter-rate codes (9%) through discussion. This strategy generated 14 studies for inclusion, all of which all were published articles in peer-reviewed journals.

The final stage of the search strategy included a review of the reference sections for the 14 published articles to locate studies we may have missed in the first two search stages. We also conducted independent searches in Google Scholar to ensure eligible articles outside of the previously searched databases were not missed. These search strategies identified six additional articles (five peer-reviewed articles and one online published report) that met our criteria, resulting in a total of 20 articles (19 peer-reviewed, one online report) included in our review. Eleven of these articles were published within the past five years (2010-2015) with only three articles published prior to 2000 (between 1991 and 1999). Published articles were primarily found in psychiatry, social work, sexual risk, and adolescent health journals.

Data Extraction

For each of the included studies, we extracted information about the study population characteristics (age, race/ethnicity, gender), sample size, assessment type (e.g., interviews, questionnaire), focus of the study (i.e., agency, youth, or both), sampling approach (i.e., location where youth were recruited from), objective/purpose of the study, and main findings specifically related to drop-in center use. We included main findings centered around four key questions toward the goal of better understanding why youth use or do not use drop-in centers: (1) What are the characteristics of youth who use drop-in center services, (2) How does drop-in center use differ from other types of service usage, (3) What are the individual-level barriers and facilitators of drop-in center use, and (4) What are the staff and service-level barriers and facilitators of drop-in center use? Data extraction information and main findings are found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Included Studies

| Study Name, Focus, Assessment Type |

Sample Description | Location of Recruitment |

Objective | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Bantchevska et al.,

2011 Youth Interviewer-administered survey |

N=82; aged 15-20 (M=19) 63% male 57% AA, 24% W All met DSM-IV-TR criteria for an SUD. |

Local soup kitchens, parks, libraries, referrals in Columbus, OH |

Predict frequency of drop-in center attendance over a period of six months |

Depressive symptoms and leaving home due to parent’s legal/substance use problems predicted greater attendance; percentage of days used alcohol predicted less attendance |

|

2. Barman-Adhikari &

Rice, 2014 Youth Interviewer- or computer- administered survey |

N=136; aged 13-24 (M=21) 61% male 38% AA, 25% H, 2% W |

One drop-in center in Los Angeles, CA |

Examine correlates of employment services utilization at the drop-in center |

Youth in temporary housing who received instrumental resources from friends (e.g., a place to stay) or caseworkers, and received emotional resources from caseworkers or street peers, were more likely to use employment services. Youth who received instrumental resources from street peers were less likely to use services. |

|

3. Carlson et al., 2006

Youth Audio computer-assisted self-interview |

N=185; aged 15-24 37% male 50% W, 28% AA, 4% H |

Youth approached at street venues |

Describe utilization of services based on “life cycle” of homeless status |

45% of youth utilized outreach services. There were no differences between life cycle stages (e.g., those new to the street, those extricated from the street into programs). |

|

4. DeRosa et al., 1999

Youth, Agency Interviews |

Phase 1: N=296; aged 13-23 67% male 24% AA, 16% H, 43% W Phase 2: N=46 “new to the street”; aged 12-23 61% male 16% AA, 20% H, 11% AS, 33% W |

Street-based hangouts and fixed agency sites in Los Angeles, CA |

Examine service utilization practices and perceptions of services using questionnaires (Phase 1) and qualitative interviews (Phase 2) |

Phase 1: Drop-in centers were the most widely used (78% of youth) of 12 services assessed, and most highly rated for satisfaction. Youth recruited from fixed agency sites were less likely to use drop-in centers, while those who used shelters were more likely to use drop-in centers. Phase 2: Youth used drop-in centers for substantive needs, but preferred to travel and stay on the streets rather than use shelters. Drop-in centers were preferred over other services due to greater flexibility, less paperwork, less disclosure of personal information, greater confidentiality, and fewer rules/restrictions. |

|

5. Ferguson et al., 2011

Agency Focus groups |

N=20; aged 18-24 65% male 65% AA, 25% H, 10% W |

One community- based agency in an urban area that offered drop-in center services as well as mental health, religious, and basic health care services |

Examine how homeless youth in agency and community settings view their leadership opportunities and how agencies encourage greater involvement among homeless youth. |

Themes included a desire to have a more formal role in agency leadership (e.g., through a youth council), more youth-staff meetings centered on emotional safety, more power to make decisions within the agency, and more opportunities for mentoring. |

|

6. Garrett et al., 2008

Youth Interviews |

N=27; aged 16-24 (M =20) 60% male 593% W, 37% mixed, 4% Native American |

Street, drop-in center, and caseworker contacts with youth that were no longer homeless |

Examine perspectives of homeless youth about facilitators and barriers to service use |

Themes included staff attributes and their relationships with young people (e.g., warm, open, and caring staff encouraged drop-in center use as opposed to judgmental staff), structural barriers (e.g., inconvenient location, waiting lists, limited operating hours, maximum capacity, and age restrictions), independence (e.g., strong desire to be self-reliant or being too busy inhibited service use), use of substances (e.g., not wanting to disappoint staff if showed up to a drop-in center high), and use of services by peers (e.g., meeting friends at a drop- in center for an evening meal). |

|

7. Heinze et al., 2010

Youth, Agency Survey |

N=133, aged 10-24 (M=18) 68% female 62% AA, 25% W, 5% H |

Six community agencies in a large Midwestern urban area |

Examine youth ratings of service agencies (including those providing outreach services) on program characteristics, resources provided, and opportunities for positive development |

Agencies were rated more positively by females, Whites, and those involved in the program longer. Higher satisfaction was associated with agencies providing more organized structure and clear expectations/rules, encouragement for skills development, acceptance, supportive staff, and opportunities to be responsible. |

|

8. Hohman et al., 2008

Youth Computer-administered survey |

N=388, aged 14-24 (M=17) 61% male 53% H, 21% W, 13% AA |

Four drop-in centers in CA with HIV prevention resources |

Compare at-risk youth who attended population-based centers (targeted for homeless and LGBQ youth) to those attending neighborhood-based centers (serving low income primarily Hispanic neighborhoods) |

Homeless youth were more likely to use population- based than neighborhood-based centers. Homelessness, in addition to older age, greater depression, heterosexual orientation, and non- Hispanic race/ethnicity, predicted use of population-based centers. About half of all youth surveyed (homeless and non-homeless) reported confidentiality, non-judgmental staff, being treated with respect, comfortable/safe place, and low/no cost as important drop-in center features. |

|

9. Hudson et al., 2008

Agency Focus groups |

N=54; aged 18-25 (M=21) 69% male 44% AA, 22% H, 24% W All were recent drug users |

Shelter in Hollywood, CA and drop-in center in Santa Monica, CA |

Explore homeless youth’s relationships with service providers, including drop-in center staff |

Perceptions of poor communication with service providers (e.g., disrespect, confusion, nonengaging), perceived lack of empathy, and perceived untrustworthiness were reported as barriers to seeking services. |

|

10. Kort-Bulter & Tyler,

2012 Youth Interviews |

N=249; aged 14-21 (M=19) 45% male 49% W, 24% AA, 8% H |

Shelters and other areas where homeless youth congregate in three Midwestern cities |

Examine the typology (i.e., 4 clusters) of those who use different types of services (including drop-in center services like street outreach and food programs) |

Youth were most likely to utilize services typical to drop-in centers (66% used food programs, 65% used street outreach) in past year. Youth who received outreach and shelter services only reported more recent employment, were older, and had more education than youth who reported minimal service use. Youth who used multiple domain of services in addition to outreach and shelters (e.g., counseling) reported more risk behavior and victimization in their lives. |

|

11. Kozloff et al., 2013

Youth Focus groups |

N=23, aged 18-26 (M=22) 87% male 61% W, 17% AS, 9% AA, 9% H |

Agencies offering mental health services to homeless youth in Toronto, Canada |

Explore factors influencing use of services (including drop-in centers) among homeless youth with co-occurring disorders |

Themes included motivation and readiness to change as important for seeking care, importance of having a support network of family and peers, and good relationships with staff. Stigma and “abstinence-only” philosophies were seen as barriers. Youth would prefer “one-stop shop” centers that provided mental health services, in addition to basic services and health services. |

|

12. Ober at al., 2012

Youth Interviews |

N=305;aged 13-24 (M=20) 64% male 24% AA, 22% H, 19% W |

15 shelters, 7 drop- in centers, and 19 street “hangouts” in Los Angeles, CA |

Examine how drop-in center usage associates with factors related to HIV/STI testing |

Youth who used a drop-in center in the past month were twice as likely to have been tested for HIV/STI. African-American race/ethnicity was also associated with use of drop-in centers. |

|

13. Pennbridge et al.,

1990 Agency Agency-level records review |

Records from 10,515 youth served at shelters and drop- in centers in Los Angeles County between 10/86 and 9/87. |

10 agencies serving homeless youth in Los Angeles County: 5 nonprofit shelters, 1 public shelter, 4 drop-in centers |

Document and compare use of shelter and drop- in center services by homeless youth |

Drop-in center users tended to be older, White, male, and from outside the county compared to shelter users. About 50% of drop-in center users were homeless for 2+ months, told to leave home by primary caregiver, or emancipated minors (compared to 22% of shelter users). Most drop-in users were referred by friends or outreach workers, whereas most shelter users were referred by law enforcement or other agencies. |

|

14. Pergamit & Ernst,

2010 Youth Interviews |

N=83, aged 14-17 54% male 47% AA, 23% H, 16% W |

Shelters and streets in Chicago, IL and Los Angeles, CA |

Examine homeless youths’ knowledge about services available to them and their use of these services |

More youth reported using drop-in centers (58%) compared to shelters (36%), counseling (40%), and substance use treatment (39%). Few youth who did not use drop-in centers knew where to find one. Youth reported a desire for more recreational, vocational, and mentoring services. |

|

15. Reuler et al., 1991

Agency Chart review |

N=609, aged 2-22 (M=17) 53% female. Race/ethnicity not reported. |

One drop-in center in Portland, OR |

Describe the diagnoses made by staff for all service users between 11/85 and 11/89 at one drop-in center |

Most common diagnoses by drop-in center staff were related to respiratory, dermatologic, and gynecologic (mostly pregnancy test) problems. Most frequent tests ordered were for pregnancy and “strep throat.” Most prescriptions were antibiotics, decongestants, analgesics, and topicals. Over half of referrals were to community hospitals or non-profit and county clinics. |

|

16. Rhoades et al., 2014

Youth Computer-assisted self interview |

N=398, aged 13-28 (M=21) 70% male 31% W, 28% AA, 16% H |

Two drop-in centers in Venice, CA and Hollywood, CA |

Examine differences in service utilization by homeless youth with and without pets |

23% of drop-in center users owned a pet. Pet owners reported less loneliness and depression, but were also less likely to use shelters and job help services than non-pet owners. About half of pet owners reported the pets made it more difficult to stay in a shelter and 11% reported it made it difficult to see a health care provider. |

|

17. Shillington et al.,

2011 Youth Computer-administered survey |

M=96, 14 to 24 (M = 18) 60% male 44% W, 23% H, 16% AA |

Two drop-in centers in Southern CA. One was targeted toward LGBQ and one targeted toward homeless in general. |

Compare demographic and risk behavior differences among homeless youth seeking services at a LGBQ targeted drop-in center and a general youth homeless drop-in center |

Youth reported multiple school/legal issues, inconsistent condom use, and alcohol and drug use. Compared to youth at the homeless drop-in center, those at the LGBQ center were more likely to be White and older, have carried a weapon, not attending school, homeless for longer, religious, and engaged in sexual and substance use risk behavior (but less engaged in alcohol and drug services). |

|

18. Sweat et al., 2008

Youth Surveys and focus groups |

N=54, aged 15-25 (M = 20) Gender not reported 44% AA, 24% W, 22% H |

One drop-in center in Santa Monica, CA and one homeless shelter in Hollywood, CA |

Examine differences between youth who use a drop-in center and youth who use a shelter on risk behaviors and relationship to broader health care systems |

Compared to shelter youth, drop-in center youth were more likely to report drug use, injection drug use, and history of an STI. Drop-in center youth reported more complaints about health care than shelter youth, most likely because shelter youth had preventive on-site care and access to a local free clinic. |

|

19. Thompson et al.,

2006 Agency Focus groups |

N = 389, 16-23 (M = 19) 52% male 65% W, 23% H, 10% AA |

One drop-in center urban Texas |

Gather homeless youths’ perceptions of services (including drop-in centers) and providers |

More than half of youth reported receiving basic services (e.g., food, clothing, shelter) and viewed these as most important, while about 13% or less identified use of other services (e.g., medical, employment, mental health). Providers who were seen as respectful, trustworthy, empathic, pet friendly, understanding of street culture, and supportive/encouraging were viewed most favorably. Unhelpful providers were perceived as those with rigid/unrealistic expectations and those who were disrespectful. Service-level barriers included locations in unsafe or unsuitable (e.g., “in back alleys”) environments, difficulty with paperwork or with establishing oneself in a service, and inconvenient access of services. |

|

20. Tyler et al., 2012

Youth Interviews |

N=249, aged 14-21 (M=18) 55% female 49% W, 24% AA, 8% H |

Shelters and streets in three Midwestern cities |

Examine frequency and correlates of specific service usage (including drop-in center services like street outreach and food programs) |

65% of youth reported use of street outreach services in the past year; 29% reported use at least once per week. Older, LGBT, more educated, those with more nights per week on the street, and those with sexual abuse histories were more likely to use street outreach services and food programs than younger youth, heterosexual youth and those without abuse histories. Those with physical abuse histories were more likely to use street outreach services than those without abuse histories. Those who were kicked out of their homes were 54% less likely to use street outreach than other youth. |

Notes: Youth studies focused on youth factors associated with utilization of drop-in center services; Agency studies focused on agency/staff factors associated with utilization of drop-in center services or studies describing a drop-in center delivery model

Numbered references correspond to superscripts in Figure 1.

DSM-IV-TR = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th ed. – Text Revision; SUD = substance use disorder

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

STI = sexually transmitted infection

LGBQ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, questioning

LGBT = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender

AA=African American/Black, H=Hispanic/Latino(a), W=White, AS=Asian

Results

Homeless Youth Who Use Drop-in Center Services Versus Other Services

In general, youth who use drop-in centers tend to differ in their demographic characteristics and have a higher risk profile than those using shelters. For example, a study in Los Angeles County found that youth using drop-in centers were more likely to be older, White, male, and come from outside the county compared to those using shelters [41]. Another study of youth in Los Angeles County found that drop-in center users were more likely to report drug use and history of a sexually transmitted infection (STI) compared to shelter-using youth [42]. Research has also found that the use of outreach services and food programs is greater among youth who have spent more nights per week on the street, as well as among those with abuse histories, compared to other youth; however, youth who had been kicked out of their homes were 54% less likely to use street outreach than those who had not been kicked out [43].

Kort-Butler and Tyler [31] conducted an analysis of homeless youth grouped by service utilization clusters and found that youth that only used services to get their basic needs met (i.e, shelters and outreach/food programs typical of drop-in centers) differed from those who did not use any services and from those who used multiple types of services available to them (e.g., counseling, mental health/substance use services). For example, those who only used services to get their basic needs met were more likely to report recent employment, older age, more nights on the street, more physical victimization of the street, and more criminal behavior than youth that reported very little use of any services at drop-in centers and elsewhere. Youth who only used services to get their basic needs met were less likely than those who used multiple types of services to have lived in a group home during their lives, to have experienced sexual abuse from family members, or to have traded sex while on the street. They also reported running away at a later age and reported less frequent time running away in their lives than youth receiving multiple services, but reported less criminal risk behavior (e.g., selling drugs) and sexual victimization on the street.

Individual-Level Barriers and Facilitators of Using Drop-In Centers

Demographics

Youth at different stages of the homeless “life cycle” (such as initiation to the street, integration into street culture, crisis occurrence, and extrication from the street) do not appear to differ in their use of outreach services that many drop-in centers offer [44]. However, use of drop-in centers and related services tends to be higher among older youth [43], as well as LGBT youth and those with more education [43]. Although there is less evidence that gender is associated with drop-in center use, some research suggests that females are more satisfied than males with services for homeless youth in general (including drop-in centers) [45]. In terms of racial/ethnic differences, one study conducted in Los Angeles found that minority youth were more likely than Whites to use drop-in center services [46], yet there is some evidence that racial minority youth are generally less satisfied with services overall [45].

Access to care and referral sources

Difficulty locating a drop-in center is an obvious barrier to its use. In a sample of 83 homeless youth, although the majority reported use of drop-in centers, very few who had not used a drop-in center before reported that they knew how to find one [32]. Studies also indicate that peers are the main referral source for drop-in centers [32]; for example, about 52% of youth using a drop-in center learned about the service from a friend as compared to only approximately 12% from program outreach efforts [41].

Role of peers

In addition to learning about drop-in centers from peers, homeless youth cite use of drop-in centers services by peers as a facilitator of their own drop-in center use; for example, they meet friends at a drop-in center for an evening meal [47]. Focus groups with Canadian youth indicated that having a social support network of family and peers was helpful in initiating care at drop-in centers and elsewhere [48]. There is also some evidence that receiving emotional support from other homeless peers may help to facilitate engagement in some services like employment support at drop-in centers [49]. However, receiving resources like food and clothing from street peers (i.e., not necessarily friends) was associated with less use of employment services, which may relate to an overreliance on the street economy or limited attachment to conventional sources of support.

Risk behaviors and other factors

Substance use and mental health problems may be factors preventing homeless youth from using drop-in centers. Bantchevska and colleagues [50] examined 82 substance abusing homeless youth in Columbus, OH who were part of a larger evaluation of different substance abuse treatment approaches. Of the factors examined as predictors of drop-in center attendance (i.e., age, gender, reason for leaving home, length of homelessness, problems in meeting basic needs, depressive symptoms, and days using alcohol and drugs), three factors predicted reduced frequency of drop-in center use: leaving home due to legal or substance use problems, greater depressive symptoms, and greater percentage of days using alcohol in the past 90 days. Youth in a focus group study similarly discussed how substance use was a barrier to drop-in center use; for example, youth described how they may not feel the need for services when high or that they did not want to disappoint staff by showing up under the influence [47].

Pets

Pet owners and non-owners report similar use of food and clothing services [51], likely because these services are typically offered at drop-in centers where pets are allowed. Pet ownership was cited as a barrier to shelter use, but not necessarily to drop-in center use [51]. However, pet owners have reported that providers who are pet-friendly may help to facilitate engagement in drop-in center use as well as with higher levels of care use [29]. For example, youth with pets report that the animals provide motivation for them to take care of themselves, as well as motivation to seek services that offer food and temporary shelter to the pets [29, 51].

Motivation and self-efficacy

In focus group work with 23 homeless youth receiving mental health services in Toronto, Canada, youth discussed that internal motivation was a key component guiding one’s decision to seek services at drop-in centers and elsewhere [48]. However, youth also report a personal pride in being independent and self-reliant in terms of getting their needs met on the street [47].

Staff and Service-Level Barriers and Facilitators of Using Drop-In Centers

Staff characteristics

Several qualitative studies have found that characteristics of the staff can both facilitate and discourage use of drop-in centers. Being warm, open, non-judgmental, and caring [29, 47, 48, 52, 53], and able to relate to the youth’s presenting issues [29, 52], can encourage youth to use drop-in centers. In contrast, staff who are perceived as judgmental [47], act disrespectful toward the youth, or have rigid or unrealistic expectations of the youth [29], may discourage service utilization. Other researchers have found that youth report non-engagement with service providers who demonstrate authoritative communication styles (e.g., judgmental, hurried manner), convey disrespect, do not take the youth seriously, and appear untrustworthy [52]. A survey of 133 youth in Midwestern cities similarly found that greater satisfaction among youth is reported for supportive staff from agencies (including emergency shelters, youth and family counseling) that are organized with a clear structure, encourage a sense of belonging, and promote independence and self-efficacy [45].

Structural characteristics

Homeless youth prefer drop-in centers over other types of services due to perceived greater flexibility and confidentiality, less paperwork and disclosure of personal information, and fewer rules/restrictions [29, 54]. Indeed, youth who use drop-in centers report barriers to seeking other kinds of services outside of the drop-in center such as delays in service, difficulty finding transportation, perceived lack of respect by health care workers, and high costs [42]. In a study that surveyed 189 at-risk youth seeking drop-in center services for the first time (about 44% were homeless; others had a place to stay), confidentiality, low/no cost, location in a safe area, comfortable setting, and clean facilities were reported among the most important aspects of the centers by at least half of those surveyed [53]. The most commonly endorsed reasons for attending drop-in services by the homeless youth were that it provided a safe place to be (45.7% endorsed this reason), offered recreational opportunities (39.2%), and linkages to other services (11.3%) [25].

Structural barriers to drop-in center use discussed by youth include inconvenient locations, long waiting lists, limited or inconvenient operating hours, inadequate capacity, and age restrictions [47]. Drop-in centers are sometimes perceived as being located “in back alleys” or in unsafe areas, or far from other services needed by the youth, which can also pose barriers to utilization [29]. In addition, youth who use drop-in centers report greater difficulty with finding and receiving medical care services than do youth who report staying at shelters, perhaps due to the availability of prevention services at shelters [42]. Youth at drop-in centers also desire more opportunities for recreation, schooling/vocational training, and mentorship from others who have similar experiences. For example, drop-in center users at one agency reported satisfaction with services offered but desired more mentoring opportunities and more formal roles in the decision making of the agency (e.g., youth council) [32].

Conceptual Model

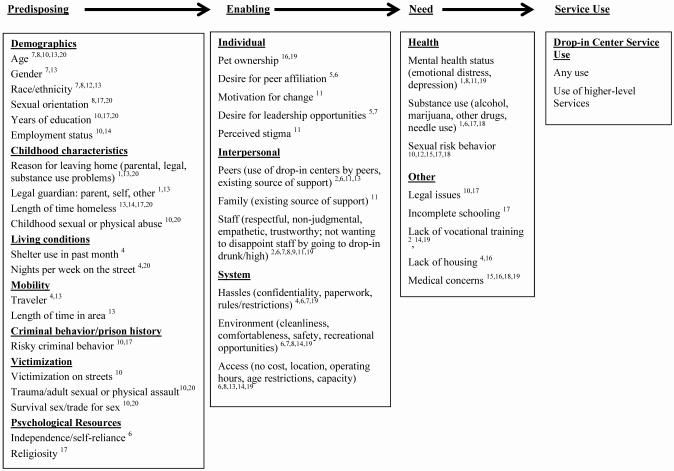

Based on the findings of our review, we developed a model of drop-in center use among homeless youth (Figure 1). This model builds on the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations [36] that has been applied to broader health care service use among vulnerable adolescents with a history of homelessness [37] by including predisposing, enabling, and need factors. In contrast to prior work, the proposed model is specific to drop-in center usage, as opposed to general health care service usage in ambulatory and emergent care settings, and focuses on barriers and facilitators to the utilization of drop-in center services.

Figure 1.

Model of Drop-in Center Use among Homeless Youth Based on the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations

Predisposing factors

Several predisposing factors identified from this review may facilitate or prevent the use of drop-in centers. Demographic factors included in the conceptual model are age, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, years of education, and employment status. Although the research in this area is limited, age, gender, and race/ethnicity may play a role in youth’s utilization of drop-in services and their satisfaction with the services received. In addition, LGBT youth were identified in our review as a population that warrants further attention given their greater engagement in drop-in center services, yet need for intensive higher level drop-in services, compared to heterosexual youth. Youth who have completed more education or are able to secure employment may depend less on drop-in centers due to their independence and perhaps limited need of basic services. Thus, offering job training or working with local businesses to help youth obtain employment may help increase independence and reduce demand for basic needs services.

In addition to these demographic factors, childhood characteristics such as reason for leaving home (e.g., being kicked out by parents, leaving due to substance use problems) and legal guardian status may be factors involved in drop-in center usage. These are directly related to length of time homeless (e.g., youth who ran away at a young age may have greater experience on the streets), childhood sexual or physical abuse (which may have been a reason why youth left home initially), and victimization since being homeless, such as sexual or physical assault or other traumatic experiences. Given the confounding mental health needs and often traumatic histories of homeless youth, mental health and counseling services appear to be an essential service needed at drop-in centers, particularly since youth with these backgrounds utilize drop-in centers to a greater extent than those without trauma histories.

Other predisposing factors include current living condition (e.g., staying in a shelter versus on the street), mobility (e.g., “traveler” moving around often, youth just recently arrived in the area), and criminal or prison history. Having a sense of pride in being independent and not needing outside help to survive is also linked to less service use. Identifying subgroups of homeless youth who are unlikely to seek out drop-in services on their own is essential for informing outreach efforts to engage particularly hard-to-reach youth, which often include those at greatest need for drop-in center services.

Enabling factors

Enabling factors include individual, interpersonal, and system level domains that may facilitate or prevent youth from using drop-in centers. Factors at the individual level that are conceptualized as facilitators of drop-in center use include pet ownership, desire to connect with peers in social settings, desire for leadership opportunities within the drop-in center, and motivation to change potentially risky behaviors or get off the streets. In contrast, perceived stigma of using services is an individual level barrier to service use. Interpersonal factors that facilitate usage include getting emotional support from others, exposure to peers who use drop-in centers themselves, and drop-in center staff that evidence respect, empathy, and trustworthiness, and are accepting of youth without judgment. In contrast, staff that are perceived as disrespectful, judgmental, non-empathetic, and untrustworthy may be barriers to service use. Although drop-in centers generally accept youth if they arrive under the influence (within reasonable limits), youth may perceive that good relationships with staff could be negatively impacted by their use of substances, which could prevent them from seeking services while under the influence. System-level factors that may facilitate drop-in center use include limited hassles associated with drop-in centers (e.g., fewer rules/restrictions, less paperwork, greater degree of confidentiality); a clean, comfortable, and safe environment; multiple recreational and social activities; and convenient or open access to the centers.

If providers at drop-in centers better understand the factors enabling use of drop-in center services, they can tailor outreach efforts to engage youth to initiate use of centers and encourage already enrolled youth to pursue higher level services based on their personal needs. For example, efforts can be made to hire staff members that possess the qualities to which youth respond positively. Service providers themselves must be self-aware of behaving or communicating in a way that can be perceived as "judgmental" as this could deter youth from seeking services. Policies around confidentiality may need to be modified and rules for admittance may be relaxed (within reason) to increase enrollment numbers. Enlisting peers for outreach efforts may be another method for encouraging use of services. Offering services at locations that youth can easily access and are perceived as safe also appears to be essential for engagement.

Need factors

Beyond the basic services that homeless youth may desire and can obtain at drop-in centers, they may be able to receive higher-level services at drop-in centers or connect with other services via referrals from staff. Indeed, drop-in centers offer a unique outreach opportunity for higher-level prevention and medical services that may not be fully utilized. Homeless youth report a preference for “one-stop shop” agencies that offer integrated services encompassing mental health, health care, and basic needs [48]. Mental health problems such as depression, substance use, and sexual risk factors may either facilitate or prevent youth from seeking drop-in center services, but services targeted toward these issues are needed in drop-in centers. In addition, youth report legal, schooling, employment, and housing needs. Thus, there is much potential for drop-in centers to hire staff or seek community volunteers to deliver tailored programs in these areas. These programs could help draw new users into the centers but could also serve those youth already attending drop-in centers for basic needs services.

Since drop-in centers tend to be preferred over other services and are the most used of all the service options [29-32], they represent an important avenue to offer homeless youth a variety of higher-level services such as mental health care, substance use treatment, HIV/STI testing, and assistance with educational and employment needs. For example, researchers found that about half of a sample of 136 youth seeking services at one drop-in center in Los Angeles reported using employment services at the site [49]. Drop-in centers may not only represent a one-stop shop where many services can be delivered, but youth who receive these services may be more likely to seek further services elsewhere. For example, one study found that only those youth who reported use of drop-in centers and/or shelters (as compared to those who do not) reported use of any medical, dental, or other services such as mental health or employment services, crisis hotlines, or substance use treatment [30]. Use of drop-in centers in the past month also emerged as a predictor of ever receiving HIV/STI testing among 305 homeless youth in Los Angeles, an effect seen when other factors such as number of sex partners and depression symptoms were not significant predictors [46]. Lastly, although the study did not specify where the STI/HIV testing occurred, Tyler and colleagues [43] found that youth who were older, female, LGBT, more highly educated, victims of sexual abuse, and had group home/foster care placement were more likely to report receiving testing in the past year. Thus, there is much potential for drop-in centers to meet the higher-level needs of homeless youth.

Implications and Contribution

In this review, we outlined the core facilitators and barriers of drop-in center usage by homeless adolescents and young adults. Our proposed model of drop-in center service usage by homeless youth serves as an initial step toward a more comprehensive plan of action to meet the federal government’s strategic plan to prevent and end youth homelessness by designing and offering better interventions and outreach methods to meet this goal [34]. As an immediate next step, our proposed model needs to be empirically tested through quantitative survey research and qualitative interviews with homeless youth and drop-in center staff. It is also clear that further research is needed to more definitively outline specific facilitators and barriers to service use, which when understood fully can be addressed to better meet the needs of homeless adolescents and young adults.

Outreach workers can make use of this review to target youth with specific characteristics that make them unlikely to engage in services. Likewise, if center staff better understand what prevents homeless youth from using their services, they can implement changes to their center to better engage and retain youth, as well as seek funding and volunteers to provide higher level services that youth might benefit from if offered. The knowledge that youth are more likely to use drop-in centers as opposed to other services advocates for drop-in centers to offer higher level services that youth may not use otherwise. If limited funding or staffing precludes drop-in centers from offering more of these higher-level services to youth, efforts can be made to partner with local organizations, clinics, and volunteers in the community to bring outside providers into the drop-in center or to offer services outside the center that contain the same attractive qualities that encourage youth to use drop-in centers (e.g., limited paperwork, confidentiality, respectful providers). Drop-in centers are in a unique position to facilitate these relationships based on practical knowledge of what works to engage youth. Staff can work to address multiple needs of homeless youth in an environment in which they are likely to engage.

Implications and Contribution.

This study reviewed the facilitators and barriers of drop-in center usage by homeless youth and developed a conceptual model of drop-in center service. These findings can serve as an initial step toward a more comprehensive plan of action to increase research and outreach efforts to meet the diverse needs of homeless youth.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Engaging Substance Using Homeless Youth in Drop-in Center Services, R21 DA039076, awarded to Joan S. Tucker, Ph.D.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Statement of authorship:

EP: conceptualized the review, reviewed articles from the search strategy, drafted initial draft of the manuscript and incorporated feedback into a final version for submission

JT: obtained funding, conceptualized the review, reviewed articles from the search strategy, reviewed drafts of the manuscript

SK: assisted with the search strategy, reviewed drafts of the manuscript.

References

- 1.National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth . Facts and resources about the education of children and youth experiencing homelessness, in Education for Homeless Children and Youth Program Data Collection Summary. U.S. Department of Education; Washington, DC: 2013. Available at http://naehcy.org/sites/default/files/dl/homeless-ed-101.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammer H, Finkelhor D, Sedlak AJ. NISMART Bulletin, October 2002. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Washington, DC: 2002. Runaway/Thrownaway Children: National Estimates and Characteristics. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henry M, et al. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Office of Community Planning and Development; Washington, DC: 2014. The 2014 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Part 1: Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greene JM, et al. Incidence and Prevalence of Homeless and Runaway Youth. RTI International; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rew L, et al. Correlates of resilience in homeless adolescents. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2001;33(1):33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson SJ, et al. Homeless Youth: Characteristics, Contributing Factors, and Service Options. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2010;20(2):193–217. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly K, Caputo T. Health and street/homeless youth. Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12(5):726–736. doi: 10.1177/1359105307080594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wenzel SL, et al. Personal network correlates of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use among homeless youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112(1-2):140–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Tayyib AA, et al. Association between prescription drug misuse and injection among runaway and homeless youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;134:406–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huba GJ, et al. Predicting substance abuse among youth with, or at high risk for, HIV. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14(2):197–205. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kipke MD, et al. "Substance abuse" disorders among runaway and homeless youth. Substance Use & Misuse. 1997;32(7-8):969–986. doi: 10.3109/10826089709055866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nyamathi A, et al. Characteristics of Homeless Youth Who Use Cocaine and Methamphetamine. American Journal on Addictions. 2012;21(3):243–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rice E, et al. The effects of peer group network properties on drug use among homeless youth. American Behavioral Scientist. 2005;48(8):1102–1123. doi: 10.1177/0002764204274194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tucker JS, et al. Substance Use and Other Risk Factors for Unprotected Sex: Results from an Event-Based Study of Homeless Youth. Aids and Behavior. 2012;16(6):1699–1707. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0017-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Rosa CJ, et al. HIV risk behavior and HIV testing: a comparison of rates and associated factors among homeless and runaway adolescents in two cities. AIDS Educ Prev. 2001;13(2):131–48. doi: 10.1521/aeap.13.2.131.19739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy DP, et al. Unprotected Sex of Homeless Youth: Results from a Multilevel Dyadic Analysis of Individual, Social Network, and Relationship Factors. Aids and Behavior. 2012;16(7):2015–2032. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0195-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tucker JS, et al. Social Network and Individual Correlates of Sexual Risk Behavior Among Homeless Young Men Who Have Sex With Men. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;51(4):386–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rotheram-Borus MJ, et al. Reductions in HIV risk among runaway youth. Prevention Science. 2003;4:173–187. doi: 10.1023/a:1024697706033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greene JM, Ringwalt CL. Pregnancy among three national samples of runaway and homeless youth. J Adolesc Health. 1998;23(6):370–7. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robertson M. In: Homeless youth, in Encyclopedia of homelessness. Levison D, editor. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shane PG. A sample of homeless and runaway youth in New Jersey and their health status. J Health Soc Policy. 1991;2(4):73–82. doi: 10.1300/J045v02n04_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Wormer R. Homeless Youth Seeking Assistance: A Research-Based Study from Duluth, Minnesota. Child and Youth Care Forum. 2003;32(2):89–103. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rabinovitz S, et al. No way home: Understanding the needs and experiences of homeless youth in Hollywood. Hollywood Homeless Youth Partnership; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tucker JS. Drug use, social context, and HIV risk in homeless youth (R01DA020351) National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shillington AM, Bousman CA, Clapp JD. Characteristics of Homeless Youth Attending Two Different Youth Drop-In Centers. Youth & Society. 2011;43(1):28–43. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beechinor L, Matsushima K. The nurse practitioner and homeless adolescents in Waikiki. Nurse practitioner forum. 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holter MC, Mowbray CT. Consumer-run drop-in centers: program operations and costs. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2005;28(4):323–31. doi: 10.2975/28.2005.323.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slesnick N, et al. How to open and sustain a drop-in center for homeless youth. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30(7):727–734. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson SJ, et al. Insights from the street: Perceptions of services and providers by homeless young adults. Evaluation and program planning. 2006;29(1):34–43. [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Rosa CJ, et al. Service utilization among homeless and runaway youth in Los Angeles, California: rates and reasons. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24(6):449–58. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kort-Butler LA, Tyler KA. A cluster analysis of service utilization and incarceration among homeless youth. Soc Sci Res. 2012;41(3):612–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pergamit MR, Ernst M. National Runaway Safeline. Chicago, IL: 2010. Runaway youth’s knowledge and access of services. Accessible at http://www.1800runaway.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/PART-A-Youth-on-Streets.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slesnick N, et al. Six- and twelve-month outcomes among homeless youth accessing therapy and case management services through an urban drop-in center. Health Research and Educational Trust. 2008;43(1):211–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00755.x. Pt 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.United States Interagency Council on Homelessness . National Research Agenda: Priorities for Advancing Our Understanding of Homelessness. United States Interagency Council on Homelessness; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.United States Interagency Council on Homelessness . Opening doors: Federal strategic plan to prevent and end homelessness. U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Services Research. 2000;34(6):1273–1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosa Solorio M, et al. Health care service use among vulnerable adolescents. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2006;1(3):205–220. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slesnick N, et al. Treatment outcome for street-living, homeless youth. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(6):1237–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peterson PL, et al. Short-term effects of a brief motivational intervention to reduce alcohol and drug risk among homeless adolescents. Psychol Addict Behav. 2006;20(3):254–64. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans J. Exploring the (bio) political dimensions of voluntarism and care in the city: The case of a ‘low barrier’emergency shelter. Health & place. 2011;17(1):24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pennbridge JN, et al. Runaway and Homeless Youth in Los-Angeles County, California. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1990;11(2):159–165. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(90)90028-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sweat J, et al. Risk behaviors and health care utilization among homeless youth: Contextual and racial comparisons. Journal of HIV/AIDS prevention in children & youth. 2008;9(2):158–174. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tyler KA, Akinyemi SL, Kort-Butler LA. Correlates of service utilization among homeless youth. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34(7):1344–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carlson JL, et al. Service utilization and the life cycle of youth homelessness. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38(5):624–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heinze HJ, Jozefowicz DMH, Toro PA. Taking the youth perspective: Assessment of program characteristics that promote positive development in homeless and at-risk youth. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32(10):1365–1372. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ober AJ, et al. If you provide the test, they will take it: Factors associated with HIV/STI testing in a representative sample of homeless youth in Los Angeles. AIDS education and prevention: official publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2012;24(4):350. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2012.24.4.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garrett SB, et al. Homeless Youths' Perceptions of Services and Transitions to Stable Housing. Evaluation and program planning. 2008;31(4):436–444. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kozloff N, et al. Factors influencing service use among homeless youths with co-occurring disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(9):925–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barman-Adhikari A, Rice E. Social networks as the context for understanding employment services utilization among homeless youth. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2014;45(0):90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bantchevska D, et al. Predictors of Drop-in Center Attendance among Substance-Abusing Homeless Adolescents. Social Work Research. 2011;35(1):58–63. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rhoades H, Winetrobe H, Rice E. Pet Ownership Among Homeless Youth: Associations with Mental Health, Service Utilization and Housing Status. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2015;46(2):237–244. doi: 10.1007/s10578-014-0463-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hudson AL, Nyamathi A, Sweat J. Homeless youths' interpersonal perspectives of health care providers. Issues in mental health nursing. 2008;29(12):1277–1289. doi: 10.1080/01612840802498235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hohman M, et al. Adolescent Use of Two Types of HIV Prevention Agencies. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention in Children & Youth. 2008;9(2):175–191. [Google Scholar]