Abstract

Although most children with multiple islet autoantibodies develop type 1 diabetes, rate of progression is highly variable. The goal of this study was to explore potential factors involved in rate of progression to diabetes in children with multiple islet autoantibodies. The Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY) has followed 118 children with multiple islet autoantibodies for progression to diabetes. After excluding 27 children currently diabetes-free but followed for <10 years, the study population was grouped into: rapid progressors (N=39) who developed diabetes in <5 years; moderate progressors (N=25), diagnosed with diabetes within 5-10 years; and slow progressors (N=27), diabetes-free for >10 years. Islet autoimmunity appeared at 4.0±3.5, 3.2±1.8 and 5.8±3.1 years of age in rapid, moderate and slow progressors, respectively (p=0.006). Insulin autoantibody levels were lower in slow progressors compared to moderate and rapid progressors. The groups did not differ by gender, ethnicity, family history, susceptibility HLA and non-HLA genes. The rate of development of individual islet autoantibodies including mIAA, GADA, IA-2A and ZnT8A were all slower in the slow versus moderate/rapid progressors. In multivariate analyses, older age at seroconversion and lower initial mIAA levels independently predicted slower progression to diabetes. Later onset of islet autoimmunity and lower autoantibody levels predicted slower progression to diabetes among children with multiple islet autoantibodies. These factors may need to be considered in the design of trials to prevent type 1 diabetes.

Keywords: multiple islet autoantibodies, islet autoimmunity, rate of progression to diabetes, type 1 diabetes, predictors for diabetes

1. Introduction

Prevention trials would benefit from a more precise method to predict overall staging and rate of progression to type 1 diabetes. Though genetic markers can identify varying risk, it is only once islet autoimmunity has begun (marked by the presence of multiple islet autoantibodies) that a high positive predictive value (>90%) can be achieved. Multiple islet autoantibodies are present in the great majority of prediabetics (1-3). Screening for risk of type 1 diabetes utilizes “biochemical” autoantibody assays for specific islet autoantigens (4). These include autoantibodies to insulin (mIAA) (5), glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA) (6), IA-2A (ICA512) (7) and most recently ZnT8A (8). Individuals having a single positive autoantibody (mIAA, GADA, IA-2A or ZnT8A) are at low risk for progression to diabetes, while the majority of individuals expressing two or more positive autoantibodies, especially on multiple tests over time, will develop type 1 diabetes according to combined analysis from prospective birth cohort studies in Colorado, Finland, and Germany (9). However, rate of progression to diabetes among multiple autoantibody positive subjects varies widely, from a few months to several years after seroconversion.

Insulin autoantibodies are often high at the onset of diabetes in young children while usually negative in individuals first presenting with diabetes after age 12. High levels of insulin autoantibodies have been associated with younger age of onset of diabetes (10;11). In the BABYDIAB study, only non-HLA type 1 diabetes susceptibility genes but not autoantibody levels or HLA-DR3/4-DQ8 influenced rate of diabetes progression among first-degree relatives children with multiple islet autoantibodies (12).

In this study we evaluated potential factors involved in rate of progression to diabetes in multiple autoantibody positive subjects followed prospectively in the Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY). We found that later onset of islet autoimmunity and lower autoantibody levels predicted slower progression to diabetes among children with multiple islet autoantibodies.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study population

Since 1993, DAISY has followed two cohorts of young children at increased risk of type 1 diabetes (total N=2542): a cohort of relatives of type 1 diabetes patients (siblings and offspring), and the general population newborn cohort. The latter consists of children with type 1 diabetes susceptibility HLADR/DQ genotypes identified through screening of over 31,000 newborns at St. Joseph Hospital in Denver, Colorado. Recruitment began in 1993 and ended in 2004. The details of screening and follow-up have been previously published (13). Autoantibodies to insulin, GAD65, IA-2 and ZnT8 were measured in the Immunogenetic Laboratory at the Barbara Davis Center using previously described radio-immunoassays (14). Children in DAISY were tested for islet autoantibodies during the prospective follow-up, beginning at 9 months, 15 months, 24 months and annually thereafter; autoantibody positive children are followed and tested for islet autoantibodies every 3-6 months. Only DAISY children who have developed multiple (2 or more) islet autoantibodies (N=118) were included in this study. Three groups were defined according to time from seroconversion: rapid progressors (N=39) who developed type 1 diabetes in <5 years, moderate (N=25) diagnosed with diabetes within 5-10 years and slow progressors (N=27) who had a diabetes-free follow-up for >10 years (5 eventually developed diabetes). Excluded were 27 children diabetes-free followed for <10 years. The cut-offs of >10 years and < 5 years were chosen to be consistent with other prospective studies and risk assessment estimated in these children (9;12;15). Onset of diabetes was defined according to ADA criteria. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of each study subject. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved all study protocols.

2.2. Islet Autoantibodies

Measurement of islet autoantibodies to insulin, GAD65, IA-2 and ZnT8 was performed in the Clinical Immunology Laboratory at the Barbara Davis Center (BDC) using radio-immunoassays as described in the paper by Yu et al (16). In the 2015 IASP Workshop, sensitivities and specificities were 52% and 100% respectively for mIAA, 82% and 99% respectively for GADA, 72% and 100% respectively for IA-2A, and 70% and 97% respectively for ZnT8A. Measurement of electrochemiluminescence (ECL) assays was performed on yearly DAISY samples in the Immunogenetic Laboratory at the BDC using methods previously described (17;18). The ECL assay cut-off indexes of 0.006 for ECL-IAA or 0.023 for ECLGADA were set at the 99th percentile over 100 healthy controls and the ECL inter-assay co-efficiencies of variation (CV) were 4.8% (n=20) for ECL-IAA and 8.8% (n=10) for ECL-GADA, respectively. In the 2015 IASP Workshop, sensitivities and specificities for the ECL assays were 60% and 98% respectively for ECL-IAA, and 78% and 96% respectively for ECL-GADA, among patients with newly diagnosed T1D.

2.3. Genotyping

Non-HLA single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were genotyped using either a linear array (immobilized probe) method essentially as described in Mirel et al.(19), Illumina GoldenGate Beadexpress assays (veracode 48-plex) or Taqman SNP genotyping assays (Applied Biosystems, CA USA) as previously described (20). The 25 following non-HLA SNPs were analyzed: rs2292239 (ERBB3), rs12708716 (CLEC16A), rs4788084 (IL27), rs7202877 (CTRB), rs4900384 (C14orf), rs2290400 (GSDM), rs5753037 (HORMAD2), rs56297233 (BACH2), rs4763879 (CD69), rs7020673 (GLIS3), rs1990760 (IFIH1), rs3024496 (IL10), rs917997 (IL18RAP), rs12251307 (IL2RA), rs689 (INS), rs1893217 (PTPN2), rs2476601 (PTPN22), rs3184504 (SH2B3), rs2281808 (SIRPG), rs1738074 (TAGAP), rs11203203 (UBASH3A), rs9976767 (UBASH3A), rs13266634 (SLC30A8), rs231775 (CTLA4) and CCR5 (microsatellite).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using PRISM (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla,CA) and SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Autoantibody levels were converted to SD units away from threshold (Z scores) and then log transformed for analyses. Because of negative values, 1 was added before log transformation and calculation of mean. Proportions were compared using chi-square or Fisher's exact test. Follow-up time was defined as time from the initial positive autoantibody test for each subject. Time to diabetes was defined as the time from initial seroconversion. Multivariate time-varying Cox PH model was used to evaluate potential factors involved in rate of progression to diabetes, including age at seroconversion, family history of type 1 diabetes, number of initial autoantibodies and time-varying autoantibody levels. To test the proportional hazards assumption, we used the supreme test methods. The proportional hazards assumption was tested for the following fixed variables, number of first positive autoantibodies, family history of type 1 diabetes and HLA DR3/4-DQ8. We concluded that the proportional hazards assumption was not violated. Survival analysis was performed for development of autoantibodies using the log-rank test.

3. Results

The characteristics of study participants are shown in Table 1. Gender, ethnicity, family history of type 1 diabetes and HLA DR3/4-DQ8 were not significantly different between the groups. Slow progressors had later onset of islet autoimmunity compared to moderate and rapid progressors (5.8±3.1, 3.2±1.8 and 4.0±3.5 years respectively, p=0.006). Slow progressors were also less likely to have ever been positive for ECL-IAA compared to moderate and rapid progressors (74%, 100% and 97% respectively, p=0.001), but no differences were seen for ECL-GADA.

Table 1.

Characteristics of slow, moderate and rapid progressors in DAISY multiple autoantibody positive subjects

| Characteristics | Slow Progressors (N=27) | Moderate Progressors (N=25) | Rapid Progressors (N=39) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male Gender, N (%) | 17 (63) | 10 (40) | 22 (56) | 0.23 |

| Ethnicity NHW, N (%) | 21 (78) | 23 (92) | 36 (92) | 0.19 |

| FDRb with type 1 diabetes | 19 (70) | 14 (56) | 26 (67) | 0.53 |

| HLA DR3/3, N (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 0.38 |

| HLA DR3/4-DQ8, N (%) | 11 (41) | 10 (40) | 24 (62) | |

| HLA DR4/4, N (%) | 2 (7) | 3 (12) | 4 (10) | |

| HLA DR3/X, N (%) | 7 (26) | 4 (16) | 4 (10) | |

| HLA DR4/X, N (%) | 4 (15) | 6 (24) | 4 (10) | |

| HLA DRX/X, N (%) | 3 (11) | 2 (8) | 1 (3) | |

| ECL-IAA casec, N (%) | 20 (74) | 25 (100) | 38 (97) | 0.001 |

| ECL-GADA casec, N (%) | 19 (70) | 20 (80) | 29 (74) | 0.73 |

| Initial radioassay Abd counte | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 0.40 |

| Age at seroconversione | 5.8 ± 3.1 | 3.2 ± 1.8 | 4.0 ± 3.5 | 0.006 |

| Follow-upf from seroconversione | 13.2 ± 2.6 | 7.2 ± 1.5 | 2.7 ± 1.5 | <0.0001 |

| Follow-upf from birthe | 19.0 ± 3.6 | 10.4 ± 2.0 | 6.7 ± 4.0 | <0.0001 |

P value: chi-square or Fisher exact test for categorical variables, ANOVA for continuous variables

FDR: first-degree relative

ECL case: has ever been positive for ECL

Ab: autoantibodies

Mean ± SD

Follow-up: follow-up to development of diabetes or last visit for those slow progressors who haven't developed diabetes

Autoantibody levels for subjects who developed diabetes are summarized in Table 2. Slow progressors had lower initial mIAA levels than moderate and rapid progressors (−0.06, −0.04 and 0.15 respectively, p=0.015). No differences were found for the other autoantibodies between the three groups.

Table 2.

Autoantibody characteristics in DAISY multiple autoantibody positive subjects

| Variable | Slow progressors (N=5)a | Moderate progressors (N=25) | Rapid progressors (N=39) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial mIAAb | −0.06 ± 0.13 | −0.04 ± 0.12 | 0.15 ± 0.34 | 0.015 |

| Initial ECL-IAAb | −0.06 ± 0.15 | −0.08 ± 0.14 | 0.04 ± 0.28 | 0.14 |

| Initial GADA | −0.14 ± 0.43 | −0.04 ± 0.34 | −0.17 ± 0.32 | 0.33 |

| Initial ECL-GADAb | −0.08 ± 0.22 | −0.08 ± 0.19 | −0.04 ± 0.26 | 0.82 |

| Initial IA-2A | 0.20 ± 0.09 | 0.18 ± 0.12 | 0.24 ± 0.19 | 0.44 |

| Initial ZnT8Ab | −0.02 ± 0.01 | −0.02 ± 0.02 | −0.01 ± 0.03 | 0.90 |

Data is mean ± SD. Autoantibody levels were converted to SD units away from threshold (Z scores). Because of negative values, 1 was added before log transformation and calculation of mean.

only subjects who developed diabetes are included in these analyses

missing information in some subjects: ECL is measured yearly, not at every visit

Multivariate time-varying Cox PH model was performed to evaluate potential factors involved in rate of progression to diabetes, including age at seroconversion, family history of type 1 diabetes, HLA-DR3/4-DQ8, number of initial autoantibodies and time-varying autoantibody levels. Age at seroconversion (HR 0.8, 95% CI 0.7-1.0, p=0.044) and mIAA level (HR 1.1, 95% CI 1.0-1.2, p=0.002) were significant predictors of time to progression to type 1 diabetes in children who were multiple autoantibody positive (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate time-varying Cox PH model (Analysis of Maximum Likelihood Estimates)

| Parameter | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| FDRa with type 1 diabetes | 0.42 (0.15-1.20) | 0.105 |

| HLA DR3/4-DQ8 | 1.91 (0.78-4.68) | 0.160 |

| Age at seroconversion | 0.82 (0.67-1.00) | 0.044 |

| Initial radioassay Abb count | 1.72 (0.98-3.0) | 0.057 |

| mIAA | 1.12 (1.04-1.21) | 0.002 |

| GADA | 0.95 (0.88-1.02) | 0.124 |

| IA-2A | 1.03 (0.94-1.13) | 0.519 |

| ZnT8A | 1.38 (0.76-2.50) | 0.287 |

Multivariate models including age at seroconversion, family history of type 1 diabetes, HLA-DR3/4-DQ8, number of initial radioassay autoantibodies and time-varying autoantibody levels. Time to diabetes was defined as the time from initial seroconversion. ECL assays were not included in these models as these assays are measured yearly and not at every visit.

FDR: first-degree relative

Ab: autoantibodies

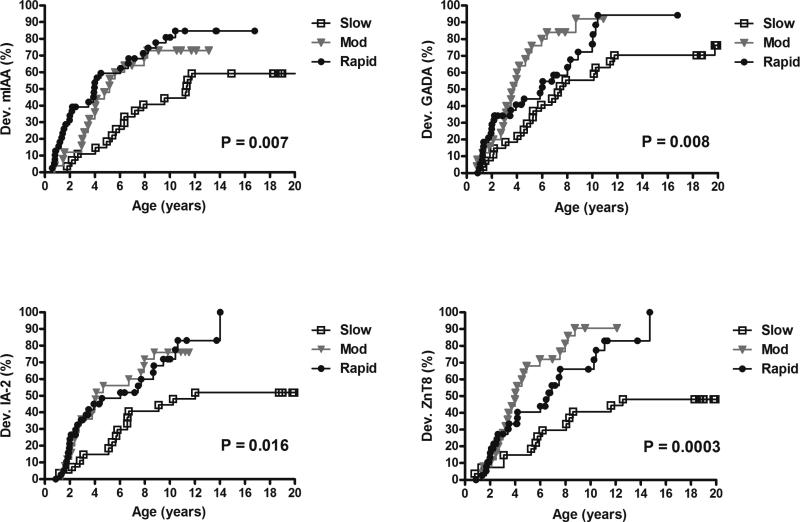

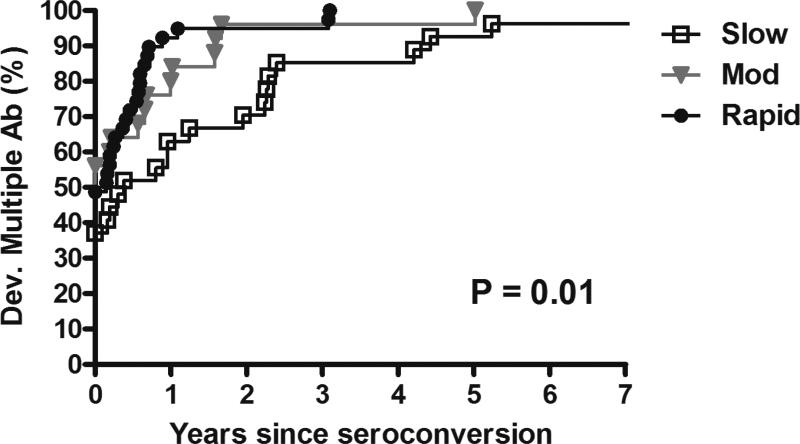

The rate of development of individual islet autoantibodies was slower in the slow versus moderate/rapid progressors (Figure 1). Slow progressors had a lower risk of developing mIAA at 10 years of age compared to moderate and rapid progressors (44%, 73% and 81% respectively, p=0.007) with similar results for IA-2A (44%, 76% and 72% respectively, p=0.016). Development of GADA at 10 years was also lower in slow progressors compared to moderate and rapid progressors (56%, 92% and 77% respectively, p=0.008) with similar results for ZnT8A (41%, 91% and 66% respectively, p=0.0003). In addition, rate of progression from single to multiple autoantibodies was slower in the slow versus moderate/rapid progressors (70% at 2 years since seroconversion vs 96% and 95% respectively, p=0.01) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Development of individual autoantibodies by groups (since birth)

Development of mIAA, GADA, IA-2A and ZnT8A since birth in slow, moderate and rapid progressors.

Dev.: development

Mod: moderate

Figure 2.

Development of multiple (≥ 2) autoantibodies by groups (since seroconversion)

Development of multiple (>2) autoantibodies since seroconversion in slow, moderate and rapid progressors.

Dev.: development

Ab: autoantibodies

Mod: moderate

Non-HLA susceptibility polymorphisms previously genotyped in DAISY (N=25) were evaluated for association with progression to diabetes from islet autoimmunity (20). No significant differences were found between the three groups. When comparing the two groups of slow to rapid progressors, only rs4763879 minor allele A (CD69) was significantly less frequent in slow progressors (p=0.036). We combined 5 gene SNPs available in 75 of the 91 subjects and previously associated with either islet autoimmunity and/or type 1 diabetes in DAISY into a genetic risk score. For all 5 gene SNPs, a score of 2 was given if the child was homozygous for the susceptible allele, 1 if heterozygous and 0 if homozygous for the non-susceptible allele. The sum of the scores for the 5 genes was assigned as the combined risk score for each child. The risk scores from all 5 SNPs (PTPN22 rs2476601, INS rs689, CTLA4 rs231775, UBASH3A rs11203203, GLIS3 rs7020673) ranged from 2 to 8. The genetic risk score among the 3 groups was not significantly different (p=0.99) (data not shown).

4. Discussion

Whether being a first-degree relative with type 1 diabetes or not, children with two or more positive islet autoantibodies have a 70% risk for developing diabetes in ten years following appearance of autoantibodies (9). Prospective studies such as DAISY and TEDDY (The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young) have shown that mIAA and, in TEDDY IA-2A levels, (but not GADA levels) were useful in estimating the age at diabetes onset. Both nonfluctuating mIAA and mIAA levels were significant factors for progression to diabetes (11;15). DAISY has the longest follow-up of children at risk for diabetes coming from both the general population and relatives of type 1 diabetes patients. This study found that later onset of islet autoimmunity and lower autoantibody levels predicted slower progression to diabetes among children with multiple autoantibodies. In addition, the rate of development of individual islet autoantibodies including mIAA, GADA, IA-2A and ZnT8A as well as development of multiple autoantibodies were slower in the slow versus moderate/rapid progressors.

Factors involved in slow progression to diabetes once islet autoimmunity is confirmed are largely unkown, but would be helpful in both design of prevention trials and the understanding of type 1 diabetes pathophysiology. Results from the BABYDIAB study (12) did not show significant differences in islet autoantibody profiles between rapid and slow progressors, except for a delayed development of IA-2A in slow progressors. Similar to DAISY, this study did not find any differences in HLA DR/DQ risk categories nor in 13 non-HLA genes overall between the slow and rapid progressors. However, combined risk score from 7 non-HLA genotypes (IL2 rs4505848, CD25 rs11594656, INS VNTR, IL18RAP rs917997, IL10 rs3024505, IFIH1 rs2111485 and PTPN22 rs6679677) was able to discriminate between rapid and slow progressors. The different results in non-HLA genes can be explained by the number and type of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) included in these two studies. In addition, BABYDIAB only follows relatives of patients with type 1 diabetes, while DAISY follows both general population children and relatives of type 1 diabetes patients.

The results of this study are consistent with previously known factors involved in high risk of development of diabetes. Age at seroconversion and autoantibody characteristics such as levels and affinity have been shown to increase risk of progression to diabetes (11;15;21;22). In addition, the presence of autoantibodies that typically develop later such as IA-2A and ZnT8A has been described as an increased risk for development of diabetes (23;24). In TrialNet, an autoantibody risk score (ABRS) (25) was developed from a proportional hazards model that combined autoantibody levels from each autoantibody (GADA, IA-2A, mIAA, ICA and ZnT8A). The ABRS was strongly predictive of diabetes in the TrialNet population. The same factors involved in risk for development of type 1 diabetes seem to be important in the rate of progression to diabetes as well. An inverse log-linear relationship between levels of insulin autoantibodies and time of progression from first appearance of islet autoantibodies to diagnosis of diabetes has been previously reported in prospectively followed DAISY children (11), and IAA levels were also significant factors for progression to diabetes in the TEDDY cohort (15). Levels of insulin autoantibodies may therefore be a marker of rate of the disease process. Although the underlying mechanism is unknown, there is some evidence that proinsulin/insulin molecules are a primary target of the islet autoimmunity resulting in diabetes of the non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse with anti-insulin T cell autoimmunity the primary driver of beta cell destruction (26).

The limitations of this study include small numbers of subjects in each group as well as incomplete non-HLA type 1 diabetes-susceptibility SNP information. Other factors such as OGTT and DPT-1 risk score (risk score based on age, BMI and OGTT indexes) could not be analyzed because of small numbers (27) (28).

Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) assays have been shown to be more disease specific and, for ECL-IAA more sensitive, than radioassays (17;18;29). Slow progressors were less likely to have been positive for ECL-IAA, but no differences were seen for ECL-GADA. ECL assays were not included in the multivariate time-varying Cox PH model as these assays were measured yearly in DAISY and not at every visit. The higher disease specificity of ECL assays seems to be related to higher affinity, confirming that autoantibody characteristics are likely important contributors to rate of progression to diabetes.

Factors involved in slower progression to diabetes among children with multiple autoantibodies include age at seroconversion and autoantibody characteristics. These factors may need to be considered in the design of trials to prevent type 1 diabetes.

Highlights.

- In subjects with multiple islet autoantibodies, insulin autoantibody levels are lower in slow progressors compared to moderate and rapid progressors

- Onset of islet autoimmunity happens later in slow progressors

- Rate of development of individual islet autoantibodies (mIAA, GADA, IA-2A and ZnT8A) are slower in the slow versus moderate/rapid progressors

- Rate of progression from single to multiple autoantibodies is slower in the slow versus moderate/rapid progressors

- No significant differences in HLA susceptibility genotypes between slow versus moderate/rapid progressors

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants DK32493, DK32083, DK050979, DK57516, JDRF 17-2013-535 and ADA Grant 1-14-CD-17. AKS takes full responsibility for the contents of the article. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no relevant conflict of interest to disclose.

Reference List

- 1.Orban T, Sosenko JM, Cuthbertson D, Krischer JP, Skyler JS, Jackson R, et al. Pancreatic islet autoantibodies as predictors of type 1 diabetes in the Diabetes Prevention Trial-Type 1. Diab care. Dec. 2009;32(12):2269–74. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siljander HT, Simell S, Hekkala A, Lahde J, Simell T, Vahasalo P, et al. Predictive characteristics of diabetes-associated autoantibodies among children with HLA-conferred disease susceptibility in the general population. diab. Dec. 2009;58(12):2835–42. doi: 10.2337/db08-1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bingley PJ, Gale EA. Progression to type 1 diabetes in islet cell antibody-positive relatives in the European Nicotinamide Diabetes Intervention Trial: the role of additional immune, genetic and metabolic markers of risk. diabetol. May. 2006;49(5):881–90. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu L, Cuthbertson DD, Maclaren N, Jackson R, Palmer JP, Orban T, et al. Expression of GAD65 and islet cell antibody (ICA512) autoantibodies among cytoplasmic ICA+ relatives is associated with eligibility for the Diabetes Prevention Trial-Type 1. diab. Aug. 2001;50(8):1735–40. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenbaum C, Palmer JP, Kuglin B, Kolb H, Participating Laboratories Insulin autoantibodies measured by radioimmunoassay methodology are more related to insulin- dependent diabetes mellitus than those measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay: results of the Fourth International Workshop on the Standardization of Insulin Autoantibody Measurement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;74(5):1040–4. doi: 10.1210/jcem.74.5.1569152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baekkeskov S, Aanstoot H-J, Christgau S, Reetz A, Solimena M, Cascalho M, et al. Identification of the 64K autoantigen in insulin-dependent diabetes as the GABA-synthesizing enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase [published erratum appears in Nature 1990 Oct 25;347(6295):782]. Nature. 1990;347(6289):151–6. doi: 10.1038/347151a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gianani R, Rabin DU, Verge CF, Yu L, Babu SR, Pietropaolo M, et al. ICA512 autoantibody radioassay. diab. 1995;44:1340–4. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.11.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wenzlau JM, Moua O, Sarkar SA, Yu L, Rewers M, Eisenbarth GS, et al. SlC30A8 is a major target of humoral autoimmunity in type 1 diabetes and a predictive marker in prediabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. Dec. 2008;1150:256–9. doi: 10.1196/annals.1447.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziegler AG, Rewers M, Simell O, Simell T, Lempainen J, Steck A, et al. Seroconversion to multiple islet autoantibodies and risk of progression to diabetes in children. JAMA. Jun 19. 2013;309(23):2473–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vardi P, Ziegler AG, Matthews JH, Dib S, Keller RJ, Ricker AT, et al. Concentration of insulin autoantibodies at onset of type I diabetes. Inverse log-linear correlation with age. Diab care. 1988;11(9):736–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.11.9.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steck AK, Johnson K, Barriga KJ, Miao D, Yu L, Hutton JC, et al. Age of Islet Autoantibody Appearance and Mean Levels of Insulin, but Not GAD or IA-2 Autoantibodies, Predict Age of Diagnosis of Type 1 Diabetes: Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young. Diab care. Jun. 2011;34(6):1397–9. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Achenbach P, Hummel M, Thumer L, Boerschmann H, Hofelmann D, Ziegler AG. Characteristics of rapid vs slow progression to type 1 diabetes in multiple islet autoantibody- positive children. diabetol. Jul. 2013;56(7):1615–22. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2896-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rewers M, Bugawan TL, Norris JM, Blair A, Beaty B, Hoffman M, et al. Newborn screening for HLA markers associated with IDDM: Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY). diabetol. 1996;39:807–12. doi: 10.1007/s001250050514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu L, Rewers M, Gianani R, Kawasaki E, Zhang Y, Verge CF, et al. Antiislet autoantibodies usually develop sequentially rather than simultaneously. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:4264–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.12.8954025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steck AK, Vehik K, Bonifacio E, Lernmark A, Ziegler AG, Hagopian WA, et al. Predictors of Progression From the Appearance of Islet Autoantibodies to Early Childhood Diabetes: The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY). Diab care. May. 2015;38(5):808–13. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu L, Simone E. Modification to Combined GAD65/ICA512 Radioassay for general population screening. diab. 1996;45(Supplement 1) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu L, Miao D, Scrimgeour L, Johnson K, Rewers M, Eisenbarth GS. Distinguishing persistent insulin autoantibodies with differential risk: nonradioactive bivalent proinsulin/insulin autoantibody assay. diab. Jan. 2012;61(1):179–86. doi: 10.2337/db11-0670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miao D, Guyer KM, Dong F, Jiang L, Steck AK, Rewers M, et al. GAD65 Autoantibodies Detected By Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) Assay Identify High Risk For Type 1 Diabetes. diab. 2013 Aug 23; doi: 10.2337/db13-0534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mirel DB, Valdes AM, Lazzeroni LC, Reynolds RL, Erlich HA, Noble JA. Association of IL4R haplotypes with type 1 diabetes. diab. Nov. 2002;51(11):3336–41. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.11.3336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steck AK, Dong F, Wong R, Fouts A, Liu E, Romanos J, et al. Improving prediction of type 1 diabetes by testing non-HLA genetic variants in addition to HLA markers. Pediatr Diabetes. Aug. 2014;15(5):355–62. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hummel M, Bonifacio E, Schmid S, Walter M, Knopff A, Ziegler AG. Brief communication: early appearance of islet autoantibodies predicts childhood type 1 diabetes in offspring of diabetic parents. Ann Intern Med. Jun 1. 2004;140(11):882–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-11-200406010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Achenbach P, Warncke K, Reiter J, Naserke HE, Williams AJ, Bingley PJ, et al. Stratification of type 1 diabetes risk on the basis of islet autoantibody characteristics. diab. Feb. 2004;53(2):384–92. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Decochez K, De Leeuw IH, Keymeulen B, Mathieu C, Rottiers R, Weets I, et al. IA-2 autoantibodies predict impending type I diabetes in siblings of patients. diabetol. Dec. 2002;45(12):1658–66. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0949-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu L, Boulware DC, Beam CA, Hutton JC, Wenzlau JM, Greenbaum CJ, et al. Zinc transporter-8 autoantibodies improve prediction of type 1 diabetes in relatives positive for the standard biochemical autoantibodies. Diab care. Jun. 2012;35(6):1213–8. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sosenko JM, Skyler JS, Palmer JP, Krischer JP, Yu L, Mahon J, et al. The prediction of type 1 diabetes by multiple autoantibody levels and their incorporation into an autoantibody risk score in relatives of type 1 diabetic patients. Diab care. Sep. 2013;36(9):2615–20. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakayama M, Abiru N, Moriyama H, Babaya N, Liu E, Miao D, et al. Prime role for an insulin epitope in the development of type 1 diabetes in NOD mice. Nature. May 12. 2005;435(7039):220–3. doi: 10.1038/nature03523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sosenko JM, Krischer JP, Palmer JP, Mahon J, Cowie C, Greenbaum CJ, et al. A risk score for type 1 diabetes derived from autoantibody-positive participants in the diabetes prevention trial- type 1. Diab care. Mar. 2008;31(3):528–33. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sosenko JM, Skyler JS, Mahon J, Krischer JP, Beam CA, Boulware DC, et al. The application of the diabetes prevention trial-type 1 risk score for identifying a preclinical state of type 1 diabetes. Diab care. Jul. 2012;35(7):1552–5. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu L, Dong F, Miao D, Fouts AR, Wenzlau JM, Steck AK. Proinsulin/Insulin Autoantibodies Measured With Electrochemiluminescent Assay Are the Earliest Indicator of Prediabetic Islet Autoimmunity. Diab care. 2013 Feb 19; doi: 10.2337/dc12-2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]