Abstract

Metamemory refers to personal knowledge about one’s own memory ability that invokes cognitive processes relevant to monitoring and controlling memory. An impaired monitoring system can potentially result in unawareness of symptoms as can occur in addiction denial. Monitoring processes can be assessed with prospective measures such as Feeling-Of-Knowing (FOK) judgments on prediction of future recognition performance, or retrospective confidence judgments (RCJ) made on previous memory performance. Alcoholic patients with amnesia showed poor FOK but intact RCJ. The neuropsychological continuum from mild to moderate deficits in nonamnesic to amnesic alcoholism raised the possibility that alcoholics uncomplicated by clinically-detectable amnesia may suffer anosognosia for their mild memory deficits. Herein 24 abstinent alcoholics and 26 age-matched controls completed an episodic memory paradigm including prospective FOK and retrospective RCJ monitoring measures and underwent 3T structural magnetic resonance imaging. Alcoholics were less accurate than controls in recognition and in assessing their future recognition performance, which was marked by overestimation, but were as accurate as controls on confidence ratings of actual recognition performance. Examination of brain structure-function relations revealed a double dissociation where FOK accuracy was selectively related to insular volume, and retrospective confidence accuracy was selectively related to frontolimbic structural volumes. Impaired FOK with intact RCJ was consistent with mild anosognosia and suggested evidence for neuropsychological and neural mechanisms of unawareness in addiction.

Keywords: alcoholism, anosognosia, brain, metamemory, MRI

1. Introduction

Alcoholism is a chronic disease characterized by physical and psychological dependence commonly marked by a notable lack of awareness of job, family, and health problems attendant to drinking. This lack of insight jeopardizes the chances of initiating and maintaining sobriety. Individuals with Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) often have mild to moderate cognitive impairment involving episodic memory—the ability to learn new information, such as recent personal experiences (Fama, Pfefferbaum, & Sullivan, 2004; Pitel et al., 2007). Early in treatment, alcoholics can be unaware of their memory deficits and overestimate their mnemonic capacities, which might suggest a mild form of anosognosia for episodic memory dysfunction and characterizes metamemory impairment (Le Berre et al., 2010). Initially used to describe unawareness of hemiplegia (Babinski, 1914), the term of anosognosia has since referred to unawareness of cognitive impairment in neurological disorders such as amnesia and dementia (McGlynn & Schacter, 1989; Barrett et al., 2005; Reed et al., 1993). Herein, our study focused on the study of unawareness of mild to moderate episodic memory deficits observed in alcoholic patients without neurological complication, which was investigated by metamemory measures collected during memory retrieval processes.

Metamemory refers to personal knowledge about one’s own ability to remember and recall information (Flavell, 1971). This function has implications for cognitive processes relevant to monitoring and controlling memory and for enabling efficient use of memory skills in everyday life (Nelson & Narens, 1990). Metamemory monitoring abilities have been assessed at different memory stages (i.e., encoding and retrieval) for general (semantic) knowledge or newly learned information (episodic memories). The recall-judgment-recognition paradigm assesses prospective knowledge, by asking participants to rate their future ability to recognize previously learned information not directly accessible in memory, considered the Feeling-Of-Knowing judgments (FOK) (Hart, 1965). Predictions of future recognition performance are then compared with the actual recognition performance (e.g., Perrotin, Belleville, & Isingrini, 2007; Shimamura & Squire, 1986; Souchay, Isingrini, & Gil, 2002). By contrast, retrospective confidence judgments (RCJs) are made following a recall or recognition task, when participants rate their confidence about the level of success of information retrieval (e.g., Modirrousta & Fellows, 2008; Schnyer et al., 2004).

Excessive alcohol consumption with severe thiamine deficiency results in Korsakoff’s Syndrome (KS), an amnesic syndrome occurring in alcoholics with untreated or under-treated Wernicke’s Encephalopathy (WE) (Kopelman, 1995; Thomson, Guerrini, & Marshall, 2012). Alcoholic KS patients demonstrated impairment in FOK accuracy for both semantic knowledge and recently learned information (Shimamura & Squire, 1986), while showing intact RCJs for recall (Shimamura & Squire, 1988). The previously observed neuropsychological continuum potentially reflecting a neuroanatomical continuity from mild to moderate brain damage in uncomplicated alcoholics to more severe brain damage in alcoholic KS patients (Butters & Brandt, 1985; Le Berre et al., 2014; Pitel et al., 2008) raised the possibility of a mild form of anosognosia for memory deficits in nonamnesic alcoholics without KS. Although nonamnesic alcoholics examined as controls in studies of KS (amnesic) alcoholics did not show metamemory impairment (Shimamura & Squire, 1986, 1988), a study of recently sober, nonamnesic alcoholics did reveal metamemory impairment. Using an episodic memory FOK measure, impairment was identified in episodic memory and metamemory in nonamnesic French alcoholics early in abstinence (Le Berre et al., 2010), who were relatively unaware of their memory deficits and overestimated their memory capacities, as confirmed also by a self-rating questionnaire about memory functioning.

In studies focused on frontal lesions, a dissociation has been suggested in neurostructural substrates supporting prospective FOK and retrospective confidence, implicating the medial prefrontal cortex in FOK accuracy (Modirrousta & Fellows, 2008; Schnyer et al., 2004) and the lateral frontal cortex in RCJs accuracy (Pannu, Kaszniak, & Rapcsak, 2005). In uncomplicated alcoholism, we assume that FOK and RCJ accuracy performance is differentially supported by selective brain substrates. In particular, we speculate that the prospective FOK judgment selectively relies on the cortical midline structures (Northoff & Bermpohl, 2004; Northoff et al., 2006; Schmitz & Johnson, 2007) and the insula (Craig, 2009; Schmitz & Johnson, 2007), which are involved in self-referential processes and awareness. By contrast, retrospective confidence judgments (RCJ) selectively rely on the frontal cortex as well as limbic regions, such as the hippocampus, known to be involved in episodic memory.

The aim of our study was to characterize metacognitive abilities in sober alcoholics by investigating both prospective and retrospective monitoring processes during an episodic memory paradigm and testing their structural brain correlates. Accordingly, we tested two hypotheses: 1) nonamnesic alcoholics would show the amnesic pattern of metamemory impairment, with impaired FOK and relatively intact RCJs, and 2) FOK performance would be related to brain regions involved in introspective thought, notably the insula, whereas RCJ accuracy would be related to brain regions involved in episodic memory, notably frontal and limbic structures.

2. Material and methods

2. 1. Participants

The two study groups comprised 24 alcoholics and 26 healthy controls (Table 1). The alcoholics were recruited from community treatment centers. Controls were recruited through flyers, announcements, or word of mouth. All participants were volunteers and provided written informed consent obtained according to institutional review board guidelines of SRI International and Stanford University School of Medicine to participate in studies assessing the effect of alcohol on brain structure and function.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants: Mean (Standard Deviation)

| Controls | Alcoholics | χ2, t | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (Women/Men) | 13/13 | 6/18 | 3.31a | 0.07 |

| Age (years) | 44.7 (12.4) | 48.7 (10.6) | −1.22b | 0.23 |

| Range: 24–63 | Range: 26–69 | |||

| Education (years) | 16.8 (2.8) | 13.3 (2.6) | 4.55b | <0.001* |

| Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR) | 117.1¥ (9.8) | 104.0 (14.9) | 3.37 b | <0.002* |

| Range: 84–126 | Range: 69–122 | |||

| Caucasian/Non-Caucasian | 21/5 | 15/9 | 2.07 a | 0.15 |

| Lifetime alcohol consumption (kg) | 30.8¥¥ (29.2) | 1061.9 (711.8) | −6.78 b | <0.001* |

| Duration of abstinence (days) | - | 95.8 (66.4) | - | - |

| Range: 9–219 | ||||

| Duration of alcoholism (years) | - | 23.0 (10.0) | - | - |

| Beck Depression Inventory score | - | 12.5 (8.7) | - | - |

| Range: 0–43 | ||||

| Smoking status Current and past dependence | 0 current | 13 current | - | - |

| 0 past | 6 past |

collected on 20 controls

collected on 22 controls

Pearson χ2.

Student’s unpaired t-test.

Significant at p < 0.05

Diagnosis of alcohol dependence was determined by consensus of at least two calibrated interviewers (clinical research psychologists or research nurse) who used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1998). Exclusion factors for all participants were lifetime DSM-IV-TR criteria for other Axis I diagnoses including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder (mood disorder other than bipolar was not an exclusion if the depression or anxiety onset postdated the alcoholism onset); history of central nervous system trauma, such as loss of consciousness for >30 min, seizures not related to alcohol withdrawal, or neurological disorders; or serious medical conditions, such as severe endocrine, hepatic, or renal disease, and HIV infection. Because of our ongoing HIV study, all alcoholics and most controls underwent laboratory testing for HIV infection, and none was positive. Control participants were interviewed to ensure that they did not meet the criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence or have any history of drug abuse.

Approximate lifetime alcohol consumption was quantified using a modification (Pfefferbaum, Rosenbloom, Crusan, & Jernigan, 1988) of a semi-structured, timeline interview (Skinner & Sheu, 1982). Drinks of each type of alcoholic beverage (wine, beer, and spirits) were standardized to units containing approximately 13.6 g of alcohol and summed over the lifetime. All subjects completed breathalyzer testing at the beginning of morning and afternoon testing sessions. Subjects were excluded if the breathalyzer exceeded 0.0.

The groups were comparable in age (Table 1). Marginally more women were in the control than the alcoholic group, but the proportion of men to women in the alcoholic group reflected the national prevalence of the sex distribution of alcoholism in the United States (Grant et al., 2003). Compared with controls, the alcoholics had fewer years of education (t (48)=4.55, p<.001); thus education was entered as a covariate in statistical analysis of behavioral tests. Verbal IQ (Wechsler Test of Adult Reading, WTAR) levels were lower in the alcoholics than the 20 controls who completed the WTAR (t (42)=3.37, p<.002). When Pearson correlations were conducted within the control group (N=20) and the alcoholic group to test relations between metamemory measures and WTAR, no significant correlation was observed. Depression symptom scores as assessed by the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) questionnaire were collected in the alcoholics; significant correlations were not forthcoming between metamemory measures and BDI scores when Pearson correlations were conducted within the alcoholic group.

The average length of lifetime alcohol dependence based on the SCID interview was 23.1±10.0 years, the mean total lifetime alcohol consumption was 1061.9±711.8 kg, and the mean length of sobriety for alcoholics was 95.8±66.4 days (range 9–219 days). Most of the alcoholic participants reported current (N=13) or past (N=6) dependence for tobacco. Chronic cigarette smoking represents a highly prevalent comorbidity in alcoholism and must be considered as a potential confounding variable given that chronic smoking can contribute to higher cognitive dysfunction in alcohol dependence (Durazzo & Meyerhoff, 2007; Durazzo et al., 2010).

2. 2. Metamemory measures

2. 2. 1. Monitoring measures of metamemory: prospective Feeling-Of-Knowing (FOK) judgment, Retrospective Confidence Judgment (RCJ), and episodic memory

A metamemory paradigm was integrated into an episodic memory task, which comprised three phases: learning, delayed recollection, and recognition. This study was implemented in a mixed block/event-related design fMRI study with the learning phase occurring before the fMRI scan session, the delayed recollection phase and the prospective FOK judgment occurring during the fMRI scan session, and the recognition task with the RCJ measure occurring after the fMRI scan session. Neuropsychological tests that could interfere with episodic memory were not administered during any of the delay intervals.

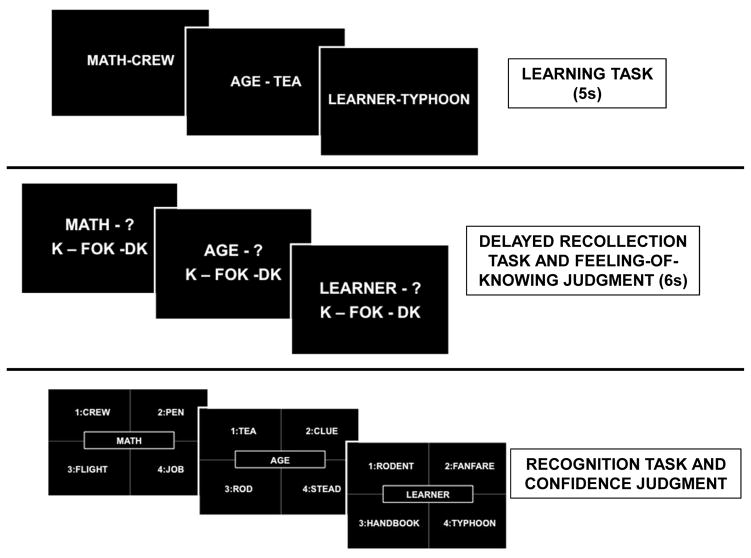

Learning phase of the episodic memory task

In the learning phase, the participants memorized 48 semantic and phonological unrelated word pairs. In each word pair, the first word (i.e., cue) was matched in frequency and numbers of syllables with the second word (i.e., target). Subjects were instructed to read aloud each word pair and study the pair carefully because later they would be asked to judge their ability to remember the second word of each pair. Participants had 5 seconds to study each word pair before moving on to the next pair. The presentation of word pairs was randomized across participants.

Delayed recollection phase of the episodic memory task and prospective FOK judgment

Approximately 40 min after the learning phase, participants performed the recollection phase of the episodic memory task associated with the FOK monitoring prospective measure. For the FOK task, participants viewed the first word of each previously learned word pair presenting as a cue and judged their memory feeling about the second word with three different options of judgment: 1) K (Know) judgment: I know that I can recall the second word, 2) FOK judgment: I cannot recall the second word and I feel able to recognize it later, 3) DK (Don’t Know) judgment: I cannot recall the second word and I feel unable to recognize it later (Figure 1). Participants had 6 sec to answer before moving to the next pair. In addition, we added 24 FOK trials on new word pairs used as control to estimate chance performance.

Figure 1.

Design of the Metamemory Paradigm

Recognition task and RCJ

Approximately 60 min after the delayed recollection phase, participants performed the recognition task. The first word of each previously learned word pair or new word pair was presented as a cue in the center of the screen and the second word of each word pair was presented among 4 items (Figure 1). Subjects were asked to choose which of the 4 words was originally paired with the center word. No time limit was imposed for the recognition trials. Finally, the confidence (RCJ) monitoring retrospective measure was collected trial-by-trial when participants were asked to assess their confidence in successful recognition of correct word matching: 1) CONF judgment: Yes, I am confident, or 2) UNCONF judgment: No, I am not confident. The delay interval between the delayed recollection and the recognition phases included additional scan series other than the metamemory fMRI part such as SPGR, FSE, and resting state fMRI series, as well as an auditory fMRI study focused on brain functioning during alcohol sounds.

We created three lists of words equivalent in frequency; words were extracted from the SUBTLEXus database where frequencies are based on subtitles from American films and television series (Brysbaert & New, 2009). The assignment of the 3 lists of words was randomized across participants, anticipating future assessment in longitudinal study. In addition, for the recognition phase of the metamemory task, we created a neutral distractor, a phonological distractor, and a semantic distractor for each correct matching second word. The phonological and semantic distractors were then shuffled and associated with a different second correct matching word to increase the level of difficulty for the recognition task. Stimuli were presented by E-Prime® software (Psychology Software Tools Inc., Pittsburgh, PA).

Two measures of episodic memory were recorded: total recognition score (number of recognized words) and the recognition success rate (%) corresponding to the % of recognized words associated with a FOK or DK judgment (i.e., without consideration for words associated with a K judgment).

The proportion (%) of “K”, “FOK”, and “DK” judgments for the FOK monitoring prospective measure and the number of “CONF” and “UNCONF” judgments for the confidence (RCJ) monitoring retrospective measure were computed separately for the healthy control and alcoholic groups. Additional measures were 1) the percentage of successful recognition for words associated with K judgment (K Hits), 2) the percentage of correct FOK prediction (FOK Hits) and correct DK prediction (DK Hits) for FOK prospective measure, and 3) the percentage of correct CONF prediction (CONF HITS) and correct UNCONF prediction (UNCONF HITS) for RCJ retrospective measure.

Two metacognitive measures were calculated to evaluate the agreement between predictions of future recognition performance and actual recognition performance for the FOK judgment and to assess the agreement between confidence feeling about previous recognition performance and actual previous recognition performance for the Confidence judgment.

The nonparametric Goodman-Kruskal gamma correlation (Nelson, 1984), which ranged from −1 to +1 and provided measure of the relative accuracy, yielded positive values corresponding to a strong association between recognition performance and prediction or retrospective judgments, values close to zero indicating the absence of association, and negative values designating an inverse relation. This measure was undefined when two of the four possible outcomes used to compute the scores (a, b, c, d) are equal to 0. Thus following Snodgrass and Corwin’s (1988) recommendation (see Souchay et al., 2002), the raw data were corrected by adding 0.5 to each frequency and then dividing by N + 1 (where N was the number of judgments).

The Hamann coefficient (Schraw, 1995) determined the absolute accuracy (i.e., the degree to which judgments matched correct and incorrect performance). This coefficient was a nonparametric correlation measure and varied from −1 to +1 where 0 corresponded to chance levels of accuracy. For the FOK measure, the Goodman-Kruskal gamma correlation and the Hamann coefficient were calculated only on FOK or DK judgments when participants did not succeed in recollecting the second word associated with the first word of each word pair. For the RCJ measure, the Goodman-Kruskal gamma correlation and the Hamann coefficient were computed on all judgments. See supplementary material for more details on the calculation of the Goodman-Kruskal gamma correlation and the Hamann coefficient.

2. 2. 2. Subjective metamemory measure: Memory Functioning Questionnaire (MFQ)

The MFQ was completed by 18 healthy controls and 23 alcoholic patients to assess self-appraisal of everyday memory functioning (Gilewski, Zelinski, & Schaie, 1990). The MFQ comprised 64 items rated in a 7-point Likert scale and provided 4 unit-weight factor scores assessing the following subjective qualifiers: General Frequency of Forgetting (“How often do these present a problem for you? names, appointments, things people tell you”); Seriousness of Forgetting (“When you actually forget in these situations, how serious of a problem do you consider the memory failure be? for names, words, phone numbers used frequently”); Retrospective Functioning (changes in current memory ability relative to earlier life: “How is your memory compared to the way it was 1 year ago? 10 years ago? When you were 18?”); and Mnemonics Usage (frequency to use mnemonic techniques, especially external memory strategies: “How often do you use these techniques to remind yourself about things? Keep an appointment book, make lists of things to do, plan your daily schedule in advance”).

2. 3. MRI data acquisition and analysis

MRI data were collected from 23 alcoholics and 25 controls. For 8 controls and 4 alcoholics, anatomical MRI data were acquired on a General Electric 3T clinical system with a volumetric SPoiled Gradient Recalled (SPGR) sequence (124 slices; 1.25 mm thick slices; skip=0 mm; TR=6.5 ms; TE=1.54 ms; flip angle=15°). For the 36 other participants (17 controls and 19 alcoholics), T1-weighted, 3D images were collected on a 3T General Electric (GE) Discovery MR750 system with an Inversion Recovery-SPoiled Gradient Recalled (IRSPGR) echo sequence (146 slices; 1.2 mm thick slices; skip=0 mm; TR=5.904 ms; TE=1.932 ms; flip angle=11°).

A clinical neuroradiologist read all structural studies to identify space occupying lesions or other dysmorphology. Additional review of images identified images with quality too poor for quantification. The scanning procedure was conducted within 1 month of the behavioral testing in all participants, except for one alcoholic patient with a timeframe of 5 weeks.

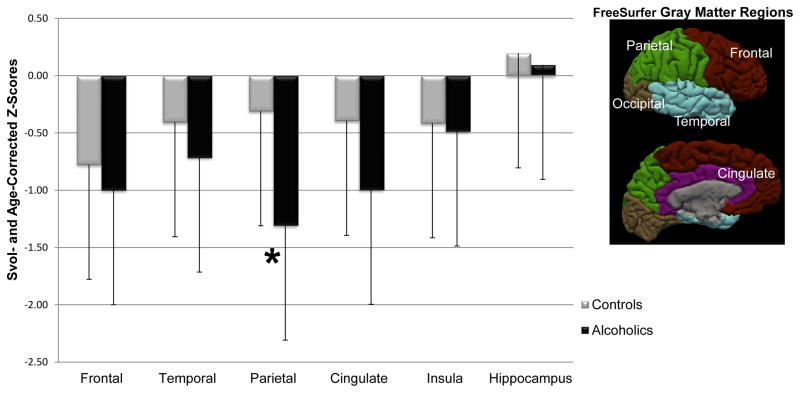

Analysis involved skull stripping, which was the result of majority voting (Rohlfing, Russakoff, & Maurer, 2004) applied to the maps extracted by the Robust Brain Extraction (ROBEX) method (Iglesias, Liu, Thompson, & Tu, 2011) and FSL BET (Smith, 2002). The SRI24 atlas-based analysis pipeline (Rohlfing, Zahr, Sullivan, & Pfefferbaum, 2010) was used to identify supratentorial volume (svol). FreeSurfer (Dale, Fischl, & Sereno, 1999) was used on skull-stripped data to create bilateral gray matter (GM) volume of hypothesis-driven regions of interest (ROI), i.e. the frontal, temporal, parietal, cingulate cortices (Desikan et al., 2006) (surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/fswiki/CorticalParcellation) plus the insular cortex and bilateral volumes of the hippocampi. This latter ROI included the hippocampus, along with the surrounding hippocampal regions, but we herein used the term of hippocampal volumes to refer to this ROI. Volumes were expressed in cc (Figure 2).

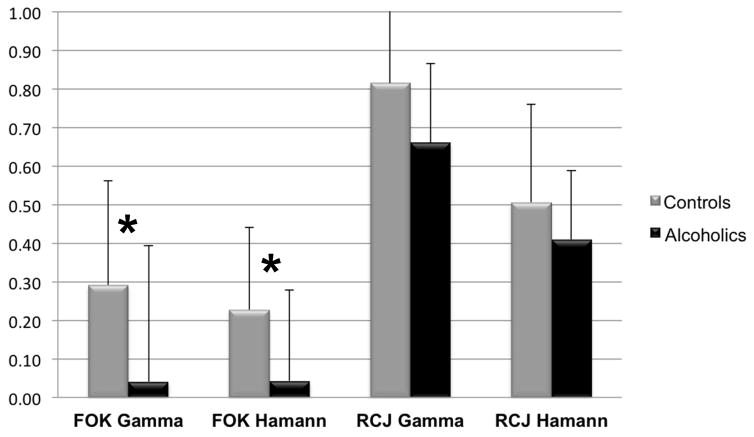

Figure 2.

Feeling-of-Knowing (FOK) and Confidence (RCJ) Goodman-Kruskal gamma correlation and Hamann coefficient in control subjects and alcoholic patients.

*Significant at p < 0.05

2. 4. Statistical analyses

To examine group differences on primary metrics, the gamma and Hamann coefficient for FOK and RCJ monitoring measures and “Hits” (%) for each judgment subtype were analyzed with analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), covarying for years of education. One-sample t-tests examined whether the gamma and Hamann coefficient were different from 0 in each group (control and alcoholic). Paired sample t-tests detected differences between FOK and RCJ gamma and Hamann coefficient in each group. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-tests sought group differences in the subjective measure of metamemory (MFQ).

Z-scores for each regional brain measure were calculated to adjust for normal variation in supratentorial volume (svol) and age by a two-step regression approach (Mathalon, Sullivan, Rawles, & Pfefferbaum, 1993; Pfefferbaum et al., 1992). For each subject, the standardized svol- and age-corrected z-scores were expressed as deviation from the mean, where, by definition, the expected mean of the control group was 0±1 standard deviation. Between-group differences in ROI volumes were assessed using 2-diagnosis (Alcoholic vs. Control) × 2-scanners (3T clinical vs. Discovery MR750) ANOVAs. Because the brain data were collected on two different scanners, the type of scanner was entered as an additional factor in these statistical analyses. To determine brain ROI volumes linkage with metamemory performance, Pearson correlations were conducted within the alcoholic group to test relations between metamemory measures (FOK and RCJ gamma) and ROI volumes. Familywise Bonferroni correction for comparisons based on 6 ROIs for directional hypothesis (poorer performance was predicted to be related to smaller brain volumes) testing with α=.05 required p≤.017. Multiple regression analysis assessed the unique contribution each brain regional volume made to each metamemory measure.

3. Results

3. 1. Episodic memory

The number of words correctly recognized and the recognition success rate percentage scores for FOK or DK judgments of the alcoholics were lower than those of the controls [total F(1,47)=4.21, p=0.0457, η2=0.082] and [% F(1,47)=5.85, p=0.0195, η2=0.111] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Episodic memory and metamemory measures in the control group and in the alcoholic group: Mean (Standard Deviation)

| Controls | Alcoholics | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Episodic Memory | |||

|

| |||

| Total recognition score | 35.5 (7.7) | 27.3 (7.6) | 0.0457* |

| Recognition success rate percentage (%) | 72.4 (14.9) | 54.3 (15.5) | 0.0195* |

|

| |||

| Feeling-Of-Knowing judgment (FOK) | |||

|

| |||

| K % | 21.5 (19.2) | 18.8 (18.7) | 0.91 |

| FOK % | 46.9 (19.2) | 46.4 (17.7) | 0.70 |

| DK % | 31.6 (17.2) | 34.8 (23.4) | 0.64 |

| K Hits % | 85.5 (24.1) | 66.3 (33.4) | 0.18 |

| FOK Gamma | 0.29 (0.27) | 0.04 (0.35) | 0.0217* |

| FOK Hamann | 0.23 (0.21) | 0.04 (0.24) | 0.0507* |

| FOK Hits % | 76.6 (16.3) | 55.8 (17.8) | 0.0064* |

| DK Hits % | 34.1 (15.5) | 44.9 (16.9) | 0.38 |

|

| |||

| Retrospective Confidence Judgment (RCJ) | |||

|

| |||

| Number of CONF judgments | 27.0 (12.2) | 25.4 (10.5) | 0.60 |

| Number of UNCONF judgments | 21.0 (12.2) | 22.6 (10.5) | 0.60 |

| RCJ Gamma | 0.82 (0.19) | 0.66 (0.21) | 0.11 |

| RCJ Hamann | 0.51 (0.25) | 0.41 (0.18) | 0.88 |

| CONF Hits % | 92.3 (10.4) | 76.1 (16.4) | 0.0191* |

| UNCONF Hits % | 50.2 (14.1) | 63.6 (16.4) | 0.12 |

Significant at p < 0.05, two-tailed test

3. 2. Prospective monitoring of metamemory: FOK judgment

Proportion of K, FOK, and DK judgments

Some participants did not make a judgment during the allotted 6 sec: 8 alcoholics and 4 controls missed 1 trial, 3 alcoholics and 1 control missed 2 trials, 1 alcoholic and 1 control missed 3 trials. Taking these missing trials into account, we calculated the proportion (%) of K, FOK, and DK judgments made. Alcoholics and controls did not differ in the percentage of K judgments [F(1,47)=0.01, p=0.91], FOK judgments [F(1,47)=0.15, p=0.70], or DK judgments [F(1,47)=0.22, p=0.64] made; thus, the groups responded similarly in making judgments on their feeling about their memory for the second word of a pair (Table 2).

Because participants made prospective judgments only about their FOK, data on number of second words of a pair accurately recollected was not acquired. Consequently, we compared the percentage of successfully recognized words associated with K judgments (K Hits). Three controls and 1 alcoholic did not provide K judgment and were not included in this analysis. No significant difference between groups was found on K Hits [F(1,43)=1.89, p=0.18] (Table 2).

FOK judgment: relative and absolute accuracy measures

The relative accuracy between FOK and recognition performance was assessed using the Goodman-Kruskal gamma correlation, and the absolute accuracy was determined using the Hamann coefficient. Both measures revealed that controls scored reliably above zero [gamma t(25)=5.53, p<0.001; Hamann t(25)=5.41, p<0.001], whereas alcoholics did not [gamma t(23)=0.56, p=0.58; Hamann t(23)=0.90, p=0.38]. Further, the alcoholic group had a significantly lower FOK gamma correlation index [F(1,47)=5.64, p=0.0217] and a trend toward lower FOK Hamann coefficient [F(1,47)=4.02, p=0.0507] than the control group (Table 2 and Figure 2).

The alcoholics produced significantly fewer Hits [F(1,46)=8.16, p=0.0064] for FOK judgments than controls. By contrast, no significant group differences emerged for Hits [F(1,46)=0.80, p=0.38] on DK judgments (Table 2). Because 1 alcoholic did not provide FOK judgments and 1 alcoholic did not make any DK judgments, these participants were not included in these analyses.

Proportion of K, FOK, and DK judgments for new word pairs

Several participants did not make a judgment during the 6 sec time frame: 5 alcoholics and 4 controls missed 1 trial, 1 control missed 2 trials, 1 alcoholic missed 3 trials, and 1 alcoholic missed 6 trials. As done for the learned word pairs, we took into account these missing trials and calculated the proportion (%) of K, FOK, and DK judgments for novel word pairs. Alcoholics did not differ significantly from controls in the number of K [F(1,47)=1.73, p=0.20], FOK [F(1,47)=2.00, p=0.16], or DK [F(1,47)=3.32, p=0.07] judgments made.

3. 3. Retrospective monitoring of metamemory: Confidence judgment (RCJ)

Number of CONF and UNCONF judgments

Alcoholic patients did not differ significantly from controls in the number of CONF [F(1,47)=0.28, p=0.60] or UNCONF judgments [F(1,47)=0.28, p=0.60]. Thus, alcoholics and controls responded similarly in making judgments about their confidence in successful recognition of correct word matching (Table 2).

Confidence judgment: relative and absolute accuracy measures

Both measures were reliably above zero by controls [t(25)=21.55, p<0.001 for gamma and t(25)=10.13, p<0.001 for Hamann] and alcoholics [t(23)=15.68, p<0.001 for gamma and t(23)=11.28, p<0.001 for Hamann]. The groups did not differ on the RCJ gamma correlation index [F(1,47)=2.60, p=0.11] or the RCJ Hamann coefficient [F(1,47)=0.02, p=0.88] (Table 2 and Figure 2). Nevertheless, the alcoholics produced significantly fewer Hits [F(1,47)=5.89, p=0.0191] on CONF judgments than controls, whereas the groups did not differ on Hits [F(1,47)=2.45, p=0.12] on UNCONF judgments (Table 2).

3. 4. Differences between FOK and RCJ metamemory (gamma and Hamann) measures

FOK gamma scores were significantly lower than RCJ gamma scores in both groups: alcoholic: t(23)=−7.37, p<0.001; control: t(25)=−8.10, p<0.001. Similarly, FOK Hamann scores were significantly lower than RCJ Hamann scores in both groups: alcoholic: t(23)=−7.24, p<0.001; control: t(25)=−4.62, p<0.001.

3. 5. Subjective measure of metamemory: Memory Functioning Questionnaire (MFQ)

Relative to controls, alcoholics had lower scores on General Frequency of Forgetting (Z=2.99, p=0.0027) and lower ratings on Seriousness of Forgetting (Z=3.97, p<0.001), suggesting that alcoholics had feelings that their memory failures were more serious and frequent than controls. Mnemonics Usage (Z=−1.92, p=0.055) showed a trend towards a difference, suggesting that alcoholics used mnemonic techniques less often than controls. No significant group effect emerged on Retrospective Functioning (Z=1.30, p=0.19).

3. 6. Group differences in the regional brain volumes

Compared with controls, alcoholics had smaller gray matter volumes in the parietal cortex [F(1, 44)=16.15, p<0.001] controlling for the type of scanner used (Figure 3). Significant effect of type of scanner was revealed only on the hippocampi volumes with higher volumes observed on the 3T clinical system than on the Discovery MR750 system, which could be explained by the fact that there were more brain data collected on controls with the 3T clinical system than with the Discovery MR750. No significant effect of interaction was showed for all ROIs volumes. As no significant effect of interaction between diagnosis × scanners was observed, the factor ‘type of scanner system’ was not significant, and thus was not controlled in the subsequent statistical analyses. Using two scanners can be problematic, which in this case is increased by the fact that more controls were scanned on one of the two scanners.

Figure 3.

Between-group differences in ROIs gray matter volumes. *Significant p < 0.05

3. 7. Regional brain volumes as predictors of FOK and RCJ accuracy in alcoholics

The gamma correlation and the Hamann coefficient yielded similar group effects. Thus, to reduce the number of comparisons, all correlations and multiple regressions were conducted on the gamma index and were restricted to measures in the alcoholic patients.

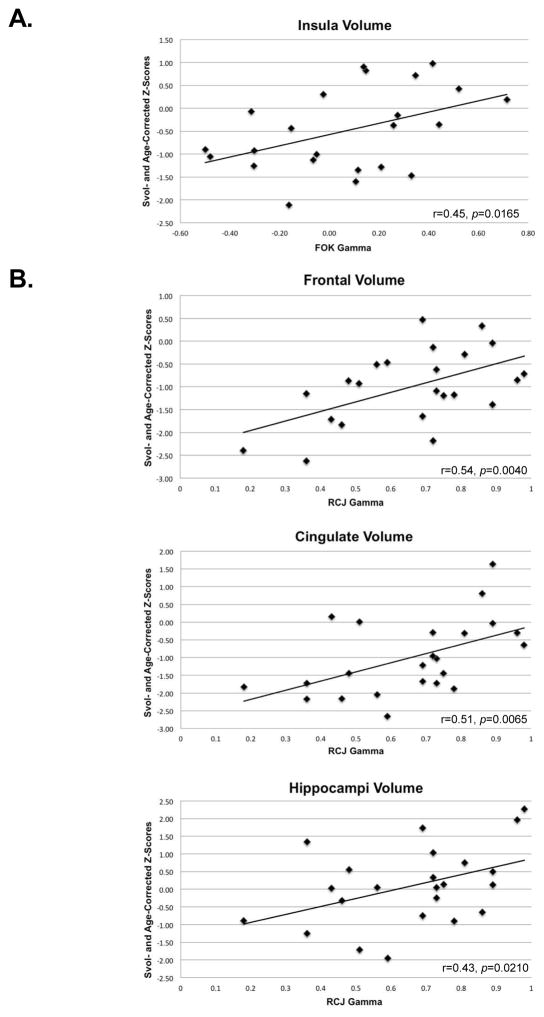

FOK Gamma

Lower FOK gamma correlated with smaller insular volumes (Figure 4A). Bilateral insula volume endured as a significant unique predictor of the FOK gamma after accounting for variance from bilateral frontal (Beta = 0.44, p<.04, R2 = 20%), cingulate (Beta = 0.44, p<.04, R2 = 20%), and hippocampal (Beta = 0.43, p<.04, R2 = 19%) volumes in separate multiple regressions.

Figure 4.

Scatterplots for significant correlations between ROIs volumes and A) FOK gamma and B) RCJ gamma in the alcoholic group (N=23 as brain data were not collected on one patient). One-tailed Bravais-Pearson correlations.

RCJ Gamma

Lower RCJ gamma was associated with smaller volumes of the bilateral frontal cortex, cingulate cortex, and hippocampus (Figure 4, B). In separate multiple regression analyses, controlling for bilateral insula volume, the bilateral frontal (Beta = 0.54, p=0.0100, R2 = 29%), cingulate (Beta = 0.51, p=0.0147, R2 = 26%) and hippocampal (Beta = 0.43, p=0.0481, R2 = 18%) volumes each endured as significant selective predictors of the RCJ gamma.

4. DISCUSSION

The aim of our study was to explicate the extent that individuals with AUD perceived their memory difficulties. Our results were consistent with the hypothesis that some metamemory monitoring mechanisms were spared and others were impaired in nonamnesic alcoholism and provided a basis for speculating about cognitive and neural substrates mediating self-awareness of memory impairment. In particular, we observed a cognitive dissociation of impaired FOK with intact RCJ and identified a double dissociation of these processes with respect to their neurostructural substrates. Specifically, FOK accuracy selectively related to volumes of the insula but not frontolimbic structures, whereas retrospective confidence accuracy selectively related to volumes of frontolimbic structures but not insula in nonamnesic alcoholics.

4. 1. Double Dissociation in Neurostructural Substrates Supporting FOK and RCJ

The insula was selectively related to FOK but not RCJ accuracy in the alcoholic group. A study using an episodic FOK paradigm reported this brain region as contributing to memory awareness in cognitively diverse older adults including cognitively normal controls and patients with Alzheimer’s disease (Cosentino et al., 2015). One assumption to understand the alcohol-related impaired FOK - intact RCJs dissociation was that prospective FOK and retrospective RCJs both implicated online memory monitoring mechanisms but differed in that FOK judgments required additional self-inferential processes to generate accurate future estimations. Our results were consistent with this possibility because the insula has been shown to be a key neural substrate supporting components of self-awareness (Craig, 2009; Schmitz & Johnson, 2007).

In contrast with the insula, frontal and limbic regions were selectively related to the RCJ but not FOK accuracy in alcoholics. In previous functional imaging studies, greater confidence was associated with greater activity in a network of limbic regions of Papez’s circuit, including the hippocampus and brain structures adjacent to the cingulate gyrus, suggesting involvement of these brain regions in subjective assessment of memory functioning (Chua, Schacter, Rand-Giovannetti, & Sperling, 2006; Kim & Cabeza, 2009). In addition to their well-established role in episodic memory retrieval processes and subjective confidence levels regardless of accuracy, these limbic structures may also contribute selectively to confidence accuracy indicated by our results. Further, implication of the posterior cingulate and medial temporal regions was observed in recollection-related processes (Eldridge, Knowlton, Furmanski, Bookheimer, & Engel, 2000; Yonelinas, Otten, Shaw, & Rugg, 2005), leading to the hypothesis that accurate confidence judgment in recognition was based on recollection memory processes.

4. 2. Cognitive Dissociation of Impaired FOK and Intact RCJ in Nonamnesic Alcoholics

Our alcoholics showed episodic memory deficits compared with healthy controls, made inaccurate FOK predictions, and tended to overestimate their memory skills. This pattern of impaired functioning was previously reported in a sample of nonamnesic French alcoholics (Le Berre et al., 2010). This alcohol-related metamemory deficit, however, did not extend to the retrospective confidence, wherein alcoholics accurately judged their success in recognizing episodic information. A similar dissociation between impaired FOK and intact RCJ was reported in amnesic alcoholics (Shimamura & Squire, 1986, 1988).

The pattern of deficiencies in episodic FOK (Souchay et al., 2002) with preserved retrospective confidence of recognizing episodic material (Moulin, James, Perfect, & Jones, 2003; Pappas et al., 1992) also characterized the metamemory profile in Alzheimer’s disease. As an organizing framework for the cognitive processes involved in metamemory, the Cognitive Awareness Model was developed in the context of understanding unawareness (i.e., anosognosia) of memory problems in Alzheimer’s disease (Agnew & Morris, 1998; Hannesdottir & Morris, 2007) and has potential application in alcoholism. This model includes different levels of unawareness in dementia, where primary anosognosia involves a failure of higher metacognitive mechanisms supporting self-awareness of memory performance ability. A secondary anosognosia follows disruptions in lower metacognitive mechanisms contributing to processing awareness (Hannesdottir & Morris, 2007). The secondary awareness category can be divided into 1) mnemonic anosognosia, corresponding to difficulties in long-term consolidation of newly updated information in semantic or autobiographical personal knowledge, i.e., failure in the personal knowledge base and 2) executive anosognosia, associated with impairment in the executive level comparator mechanisms. Breakdown in the mnemonic system leads to difficulties in detecting cognitive failure and conducting comparisons with information stored in the personal knowledge base. In our study, alcoholics were as accurate as controls on their retrospective confidence judgments, but impaired in episodic FOK accuracy. RCJ measures were reliably nonzero, contrary to the FOK measures, and were even significantly higher than their prospective FOK measures. Taken together, these findings were consistent with secondary, mnemonic anosognosia and ran counter to a primary and secondary executive anosognosia in chronic alcoholism, in that alcoholics were able to perceive a memory failure consciously when it occurred during recognition performance.

We proposed that a mnemonic anosognosia can explain the pattern of metamemory impairment observed in our uncomplicated chronic alcoholics. In this context, the alcoholics performed as if they failed to consolidate updated information into their personal long-term database. With this scenario, the alcoholics compared their current memory functioning to outdated self-beliefs. In support of this possibility was their performance on the Memory Functioning Questionnaire (MFQ). Although we expected that alcoholics would estimate their forgetting to be as severe and frequent as those of controls, surprisingly alcoholics subjectively complained about more serious and frequent everyday life forgetting than did controls. Nevertheless, at the same time, alcoholics did not acknowledge more changes in their current memory ability relative to earlier periods of life than the controls and intuitively did not perceive more changes associated with the evolution of their disease. This pattern of response implies that subjective representation of the alcoholics’ actual memory functioning, their personal database, may not have been completely updated over time and would only reflect their memory skills at some time earlier in life, perhaps before or at the beginning of their alcoholism onset. Further, the fact that alcoholics partially acknowledged their memory impairment on a subjective level but in the same time did not use this awareness to adjust estimations about their memory performance when generating their FOK judgments reinforced the operation of unawareness of memory difficulties.

4. 3. Conclusions

Metamemory is a complex construct comprising multiple, dissociable cognitive and mnemonic mechanisms (Leonesio & Nelson, 1990; Pinon, Allain, Kefi, Dubas, & Le Gall, 2005). For the first time, our study identified a double dissociation of brain structure-function relations indicating a selective relation between the insula and FOK accuracy, and a selective relation between frontolimbic structures and retrospective confidence accuracy. This double dissociation underscored the differential involvement of self-referential processes in prospective metamemory monitoring in contrast with memory retrieval processes in retrospective metamemory monitoring in uncomplicated alcoholism. Evidence for a mild form of anosognosia for memory impairment in nonamnesic alcoholics, underestimating their memory difficulties despite a partial subjective memory complaint, suggested new evidence for psychological and neural structural mechanisms of unawareness in addiction.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Association between FOK or RCJ judgments on recognition performance and actual recognition performance to calculate the Gamma and Hamann measures

Acknowledgments

The current analysis, writing, and manuscript preparation were supported by the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants AA017168, AA017923, AA010723, and AA012388.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors - Anne-Pascale Le Berre, Eva M. Müller-Oehring, Dongjin Kwon, Matthew R. Serventi, Adolf Pfefferbaum, Edith V. Sullivan - has any conflicts of interest with the reported data or their interpretation.

According to the Table S1, the nonparametric Goodman-Kruskal gamma correlation is calculated as following (ad − bc)/(ad + bc), whereas the Hamann coefficient is calculated as following [(a + d) − (b + c)]/[(a + d) + (b + c)].

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agnew SK, Morris RG. The heterogeneity of anosognosia for memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease: a review of the literature and a proposed model. Aging & Mental Health. 1998;2:7–19. doi: 10.1080/13607869856876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Babinski J. Contribution à l’étude des troubles mentaux dans l’hémiplegie organique cérébrale (anosognosie) Revue Neurologique. 1914;27:845–847. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AM, Eslinger PJ, Ballentine NH, Heilman KM. Unawareness of cognitive deficit (cognitive anosognosia) in probable AD and control subjects. Neurology. 2005;64(4):693–699. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000151959.64379.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brysbaert M, New B. Moving beyond Kucera and Francis: a critical evaluation of current word frequency norms and the introduction of a new and improved word frequency measure for American English. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41(4):977–990. doi: 10.3758/brm.41.4.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butters N, Brandt J. The continuity hypothesis: the relationship of long-term alcoholism to the Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. 1985;3:207–226. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-7715-7_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua EF, Schacter DL, Rand-Giovannetti E, Sperling RA. Understanding metamemory: neural correlates of the cognitive process and subjective level of confidence in recognition memory. Neuroimage. 2006;29(4):1150–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino S, Brickman AM, Griffith E, Habeck C, Cines S, Farrell M, Shaked D, Huey ED, Briner T, Stern Y. The right insula contributes to memory awareness in cognitively diverse older adults. Neuropsychologia. 2015;75:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD. How do you feel--now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10(1):59–70. doi: 10.1038/nrn2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9(2):179–194. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, Segonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, Buckner RL, Dale AM, Maguire RP, Hyman BT, Albert MS, Killiany RJ. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31(3):968–980. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Fryer SL, Rothlind JC, Vertinski M, Gazdzinski S, Mon A, Meyerhoff DJ. Measures of learning, memory and processing speed accurately predict smoking status in short-term abstinent treatment-seeking alcohol-dependent individuals. Alcohol and alcoholism. 2010;45(6):507–513. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Meyerhoff DJ. Neurobiological and neurocognitive effects of chronic cigarette smoking and alcoholism. Frontiers in bioscience. 2007;12:4079–4100. doi: 10.2741/2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge LL, Knowlton BJ, Furmanski CS, Bookheimer SY, Engel SA. Remembering episodes: a selective role for the hippocampus during retrieval. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3(11):1149–1152. doi: 10.1038/80671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fama R, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Perceptual learning in detoxified alcoholic men: contributions from explicit memory, executive function, and age. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28(11):1657–1665. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000145690.48510.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) Version 2.0. Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York, NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Flavell JH. First Discussant’s Comments: What is Memory Development the Development of? Human Development. 1971;14:272–278. doi: 10.1159/000271221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilewski MJ, Zelinski EM, Schaie KW. The Memory Functioning Questionnaire for assessment of memory complaints in adulthood and old age. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5(4):482–490. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;71(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannesdottir K, Morris RG. Primary and secondary anosognosia for memory impairment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex. 2007;43(7):1020–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70698-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart JT. Memory and the feeling-of-knowing experience. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1965;56(4):208–216. doi: 10.1037/h0022263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias JE, Liu CY, Thompson PM, Tu Z. Robust brain extraction across datasets and comparison with publicly available methods. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2011;30(9):1617–1634. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2011.2138152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Cabeza R. Common and specific brain regions in high- versus low-confidence recognition memory. Brain Research. 2009;1282:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopelman MD. The Korsakoff syndrome. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;166(2):154–173. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Berre AP, Pinon K, Vabret F, Pitel AL, Allain P, Eustache F, Beaunieux H. Study of metamemory in patients with chronic alcoholism using a feeling-of-knowing episodic memory task. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34(11):1888–1898. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Berre AP, Pitel AL, Chanraud S, Beaunieux H, Eustache F, Martinot JL, Reynaud M, Martelli C, Rohlfing T, Sullivan EV, Pfefferbaum A. Chronic alcohol consumption and its effect on nodes of frontocerebellar and limbic circuitry: Comparison of effects in France and the United States. Human Brain Mapping. 2014 doi: 10.1002/hbm.22500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonesio RJ, Nelson TO. Do different metamemory judgments tap the same underlying aspects of memory? Journal of Experimental Psychology Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1990;16(3):464–467. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.16.3.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathalon DH, Sullivan EV, Rawles JM, Pfefferbaum A. Correction for head size in brain-imaging measurements. Psychiatry Research. 1993;50(2):121–139. doi: 10.1016/0925-4927(93)90016-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn SM, Schacter DL. Unawareness of deficits in neuropsychological syndromes. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 1989;11(2):143–205. doi: 10.1080/01688638908400882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modirrousta M, Fellows LK. Medial prefrontal cortex plays a critical and selective role in ‘feeling of knowing’ meta-memory judgments. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46(12):2958–2965. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulin CJA, James N, Perfect TJ, Jones RW. Knowing What You Cannot Recognise: Further Evidence for Intact Metacognition in Alzheimer’s Disease. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition: A Journal on Normal and Dysfunctional Development. 2003;10(1):74–82. doi: 10.1076/anec.10.1.74.13456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TO. A comparison of current measures of the accuracy of feeling-of-knowing predictions. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;95(1):109–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TO, Narens L. Metamemory: a theoretical framework and new finding. In: BGH, editor. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation. New York: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G, Bermpohl F. Cortical midline structures and the self. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2004;8(3):102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G, Heinzel A, de Greck M, Bermpohl F, Dobrowolny H, Panksepp J. Self-referential processing in our brain--a meta-analysis of imaging studies on the self. Neuroimage. 2006;31(1):440–457. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannu JK, Kaszniak AW, Rapcsak SZ. Metamemory for faces following frontal lobe damage. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2005;11(6):668–676. doi: 10.1017/s1355617705050873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas BA, Sunderland T, Weingartner HM, Vitiello B, Martinson H, Putnam K. Alzheimer’s disease and feeling-of-knowing for knowledge and episodic memory. Journal of Gerontology. 1992;47(3):P159–164. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.3.p159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotin A, Belleville S, Isingrini M. Metamemory monitoring in mild cognitive impairment: Evidence of a less accurate episodic feeling-of-knowing. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45(12):2811–2826. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A, Lim KO, Zipursky RB, Mathalon DH, Rosenbloom MJ, Lane B, Ha CN, Sullivan EV. Brain gray and white matter volume loss accelerates with aging in chronic alcoholics: a quantitative MRI study. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 1992;16(6):1078–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A, Rosenbloom M, Crusan K, Jernigan TL. Brain CT changes in alcoholics: effects of age and alcohol consumption. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 1988;12(1):81–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinon K, Allain P, Kefi MZ, Dubas F, Le Gall D. Monitoring processes and metamemory experience in patients with dysexecutive syndrome. Brain and Cognition. 2005;57(2):185–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitel AL, Beaunieux H, Witkowski T, Vabret F, de la Sayette V, Viader F, Desgranges B, Eustache F. Episodic and working memory deficits in alcoholic Korsakoff patients: the continuity theory revisited. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32(7):1229–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitel AL, Beaunieux H, Witkowski T, Vabret F, Guillery-Girard B, Quinette P, Desgranges B, Eustache F. Genuine episodic memory deficits and executive dysfunctions in alcoholic subjects early in abstinence. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(7):1169–1178. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed BR, Jagust WJ, Coulter L. Anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease: relationships to depression, cognitive function, and cerebral perfusion. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 1993;15(2):231–244. doi: 10.1080/01688639308402560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlfing T, Russakoff DB, Maurer CR., Jr Performance-based classifier combination in atlas-based image segmentation using expectation-maximization parameter estimation. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2004;23(8):983–994. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2004.830803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlfing T, Zahr NM, Sullivan EV, Pfefferbaum A. The SRI24 multichannel atlas of normal adult human brain structure. Human Brain Mapping. 2010;31(5):798–819. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz TW, Johnson SC. Relevance to self: A brief review and framework of neural systems underlying appraisal. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2007;31(4):585–596. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnyer DM, Verfaellie M, Alexander MP, LaFleche G, Nicholls L, Kaszniak AW. A role for right medial prefontal cortex in accurate feeling-of-knowing judgements: evidence from patients with lesions to frontal cortex. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42(7):957–966. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraw G. Measures of feeling of knowing accuracy: a new look at an old problem. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 1995;9:321–332. [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura AP, Squire LR. Memory and metamemory: a study of the feeling-of-knowing phenomenon in amnesic patients. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1986;12(3):452–460. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.12.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura AP, Squire LR. Long-term memory in amnesia: cued recall, recognition memory, and confidence ratings. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1988;14(4):763–770. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.14.4.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Sheu WJ. Reliability of alcohol use indices. The Lifetime Drinking History and the MAST. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1982;43(11):1157–1170. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1982.43.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Human Brain Mapping. 2002;17(3):143–155. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass JG, Corwin J. Pragmatics of measuring recognition memory: applications to dementia and amnesia. Journal of Experimental Psychology General. 1988;117(1):34–50. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.117.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souchay C, Isingrini M, Gil R. Alzheimer’s disease and feeling-of-knowing in episodic memory. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40(13):2386–2396. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson AD, Guerrini I, Marshall EJ. The evolution and treatment of Korsakoff’s syndrome: out of sight, out of mind? Neuropsychology Review. 2012;22(2):81–92. doi: 10.1007/s11065-012-9196-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonelinas AP, Otten LJ, Shaw KN, Rugg MD. Separating the brain regions involved in recollection and familiarity in recognition memory. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(11):3002–3008. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.5295-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Association between FOK or RCJ judgments on recognition performance and actual recognition performance to calculate the Gamma and Hamann measures