Abstract

Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) as a screening test for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) has had a checkered history. During the last three decades, a few initial anecdotal reports have given way to the recent well-conducted studies. This review: (1) traces the history; (2) weighs the advantages and disadvantages; (3) addresses the significance in early pregnancy; (4) underscores the benefits after delivery; and (5) emphasizes the cost savings of using the FPG in the screening of GDM. It also highlights the utility of fasting capillary glucose and stresses the value of the FPG in circumventing the cumbersome oral glucose tolerance test. An understanding of all the caveats is crucial to be able to use the FPG for investigating glucose intolerance in pregnancy. Thus, all health professionals can use the patient-friendly FPG to simplify the onerous algorithms available for the screening and diagnosis of GDM - thereby helping each and every pregnant woman.

Keywords: Gestational diabetes mellitus, Screening, Diagnosis, Fasting capillary glucose, Fasting plasma glucose

Core tip: The algorithms for the screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), advocated by various expert panels, are demanding for both the caregiver and the care-receiver: The widely accepted approach of screening all pregnant women with the oral glucose tolerance test is time-consuming, expensive and unfeasible in most countries. Over three decades of research, summarized in this review, suggests that the fasting plasma glucose can simplify the approach to GDM - only if all the limitations of using it are clearly understood.

INTRODUCTION

For many years, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) was defined as hyperglycemia first discovered during pregnancy. However, due to the recent epidemic of type 2 diabetes mellitus afflicting numerous younger women in the child-bearing age, this traditional definition has been redefined. The World Health Organization (WHO)[1] classifies hyperglycemia first identified in pregnancy as: (1) diabetes mellitus in pregnancy; and (2) GDM. GDM generally refers to milder hyperglycemia and lesser degree of glucose intolerance occurring in the latter half of pregnancy, which usually does not persist after delivery in most patients. According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), GDM is diabetes diagnosed in the second or third trimester of pregnancy that is not type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus (T1DM or T2DM)[2]. T1DM is caused by absolute insulin deficiency with positive autoimmune markers which destroy pancreatic β-cells, while T2DM is caused by insulin resistance or relative insulin deficiency. Clearly, GDM is distinct from both these types of diabetes[2]. The reason to segregate women with DM who become pregnant is because these women have more severe complications compared to pregnant women with GDM. However, GDM is also associated with many maternal (preeclampsia, increase in cesarean sections, birth injuries) and fetal problems (macrosomia, hypoglycemia, shoulder dystocia)[3]. After delivery, patients with GDM are at a risk of developing T2DM in the mother and childhood obesity in the neonate[4]. The pathogenesis of GDM is well-understood. The hormonal changes of pregnancy cause insulin resistance; most mothers compensate by increasing insulin secretion-something women with GDM are not able to do.

The diagnosis of GDM is confirmed by the 75 g or 100 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Screening for GDM can be done by: (1) clinical risk factors; (2) the glucose challenge test (GCT); or (3) the OGTT. Even though the ideal screening method is without consensus, screening generally involves a one-step or a two-step approach. In the one step approach, all patients undergo the diagnostic OGTT. In the two-step algorithm, screening is done either by: (1) assessing the clinical risk factors; or (2) the glucose GCT usually at 24-28 wk gestation, when venous plasma glucose is measured one hour after 50 g oral glucose. Patients who have clinical risk factors or exceed a specific GCT screening threshold undergo the diagnostic OGTT. However, due to an array of recommendations available (Table 1), the screening and diagnosis of GDM remains without consensus. Often, the obstetric and endocrine associations within the same country support markedly dissimilar protocols for GDM leading to major inconsistencies in the approach to GDM globally[5]. In 2010, the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) proposed a unified approach for screening and diagnosis of GDM advocating the 2 h, 75 g OGTT for all pregnant women at 24-28 wk[6]. Since its suggested glucose OGTT thresholds were based on the elaborate Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study[7], the IADPSG approach has been accepted by many reputed expert panels [e.g., WHO, ADA and the Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society (ADIPS)], but not all the major health organizations around the world [e.g., the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)].

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus (by country)

| Organization | Use prevalent in | Year | Glucose load (g) | F mmol/L | 1-h mmol/L | 2-h mmol/L | 3-h mmol/L | Values for diagnois |

| NDDG1 | United States/North America | 1979 | 100 | 5.8 | 10.6 | 9.2 | 8.1 | ≥ 2 |

| ADA (C and C) | United States/North America | 2003 (1982) | 100 | 5.3 | 10.0 | 8.6 | 7.8 | ≥ 2 |

| ADA2 | United States/North America | 2011 | 75 | 5.1 | 10.0 | 8.5 | -- | ≥ 1 |

| CDA | Canada | 2013 | 75 | 5.3 | 10.6 | 9.0 | -- | ≥ 1 |

| EASD | Europe | 1991 | 75 | 6.0 | -- | 9.0 | -- | ≥ 1 |

| NICE | United Kingdom | 2015 | 75 | 5.6 | -- | 7.8 | -- | ≥ 1 |

| ADIPS2 | Australasia | 2014 | 75 | 5.1 | 10.0 | 8.5 | -- | ≥ 1 |

| NZSSD | New Zealand | 1998 | 75 | 5.5 | -- | 9.0 | -- | ≥ 1 |

| JDS2 | Japan | 2013 | 75 | 5.1 | 10.0 | 8.5 | -- | ≥ 1 |

| IADPSG | Multiple countries | 2010 | 75 | 5.1 | 10.0 | 8.5 | -- | ≥ 1 |

| WHO2 | Multiple countries | 2013 | 75 | 5.1 | 10.0 | 8.5 | -- | ≥ 1 |

Endorsed by American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists;

Same as IADPSG. ADA: American Diabetes Association; ADIPS: Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society; CDA: Canadian Diabetes Association; C and C: Carpenter-Coustan; EASD: European Association for the Study of Diabetes; JDS: Japan Diabetes Society; NDDG: National Diabetes Data Group; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NZSSD: New Zealand Society for the study of diabetes; WHO: World Health Organization; IADPSG: International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups.

Due to their wide acceptance, the IADPSG is best suited to be accepted world-wide. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics which has accepted the IADPSG criteria has issued a pragmatic guide for four categories: High, upper-middle, low-middle and low resource countries. Thus, depending on the resources, the IADPSG recommendations can be universally applied with modifications[8].

FEATURES OF A GOOD SCREENING TEST

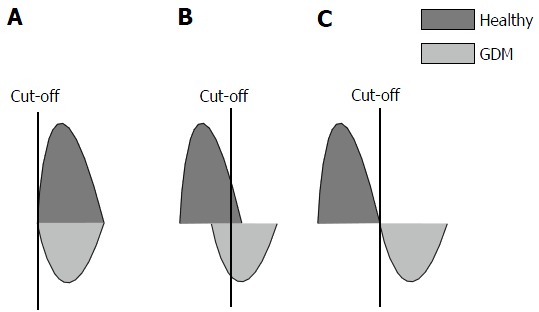

The conventional thinking is that screening tests should be very sensitive (i.e., without false negatives) so that no patient with the disease is missed, while diagnostic tests should be specific (i.e., without false positives) so the diagnosis can be confirmed in all patients with potential disease (initially picked up by the sensitive screening test). In any population, a perfect screening test would separate all the patients with disease (defined by clinical criteria or a “gold-standard” test, e.g., bone marrow stainable iron for iron deficiency anemia and OGTT for GDM) from all the healthy subjects. Thus, for GDM, the positive screening test should identify most women with GDM (true positives; the number of women picked up from all women with GDM will depend on the sensitivity) along with some women without GDM (false positives; the number of women falsely identified with GDM from amongst women without GDM will depend on the specificity), and the specific diagnostic test (OGTT in this case) will separate the true and false positives. However, usually due to overlap of the screening test results among the diseased and healthy population, choosing an appropriate cut-off (depending on the sensitivity/specificity combination desired) for the screening test would help it to become highly sensitive with minimum loss of specificity - something that may not be possible if there is a major overlap between the diseased and healthy populations. Thus, a screening test with poor specificity, i.e., too many healthy testing as diseased (being over the threshold for diagnosis due to too many false positives) would have to proceed with the test needed to confirm the diagnosis. This would make the screening test of little use since its main function is to avoid the cumbersome and expensive diagnostic test. A screening test with 0% specificity, i.e., when there is a total overlap of the diseased and healthy populations (Figure 1A), is useless. When there is less overlap between diseased and non-diseased, the performance of the screening test will be better (Figure 1B). The ideal state, when there is total segregation between diseased and healthy populations (Figure 1C), is a situation which is almost never achieved.

Figure 1.

Effect healthy and diseased populations overlap on screening test performance (A-C). GDM: Gestational diabetes mellitus.

IS SCREENING FOR GDM WARRANTED?

In the past, there were extensive and acrimonious debates about the screening for GDM. Many questions have been raised: Should we screen pregnant women for GDM at all? Should screening be based on clinical risk factors only? Is screening with GCT a valid and potentially the best approach to screening? What is the most cost-effective way to screen for GDM? How good are other screening methods like fasting plasma glucose (FPG), glycated albumin and HBA1c?

Screening for GDM does not meet many of the screening criteria set by the United Kingdom National Screening Committee, which is a modified version of the WHO criteria for assessing proposed screening programs[9]. Despite this, most preeminent professional societies, e.g., ADA and WHO, recommend screening for GDM. In 2002, a thorough review by the Health Technology Program, United Kingdom[10] concluded, “On balance, the present evidence suggests that we should not have universal screening, but a highly selective policy, based on age and overweight (of patients)”.

In 2008, after reviewing all the evidence, the preeminent United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) determined that the evidence was insufficient to assess the benefits and harms of screening for GDM. However, in 2014, the USPSTF (after another comprehensive follow-up review) advised that asymptomatic women after 24 wk of gestation should be screened for GDM, though before 24 wk, the evidence was insufficient[11].

If it is decided to screen for GDM, there is debate about the best way to screen for GDM. Though originally screening via risk-factors (age, obesity, family history of DM, GDM in previous pregnancy, non-white race, previous miscarriage/stillbirth/fetal malformation/preeclampsia/macrosomia) was widely recommended, many studies recommend otherwise: A recent comprehensive study found that this approach would miss a third of women with GDM[12]. In another recent commentary about the ideal way to screen, an editorial in a preeminent journal argued that whichever way one looks at it, there is no justification for either risk-factor or GCT based screening[13]. Their advice: The OGTT should be used for both screening and diagnosis of GDM-as recommended by the IADPSG. Though the cost of screening increases and more women are labelled as GDM, the St. Carlos study confirms that in the long term it is cheaper due to the fewer complications[14].

Many laboratory screening tests have been tried for screening of GDM. They are direct glucose measurements (FPG, GCT) or indirect measurements of glucose (HBA1c, fructosamine). Newer markers (insulin, irisin, galanin, adiponectin, sex hormone-binding globulin, C-reactive protein, fibrinectin, glycosylated fibrinactin, ferritin, glycated CD59) especially in early pregnancy have been tried to predict GDM later in pregnancy. However, only GCT and FPG have shown some promise. The holy grail of screening for GDM has yet to be found.

OGTT AS A GOLD STANDARD FOR DIAGNOSIS OF GDM AND DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

As pointed earlier, all the expert panels agree that the OGTT is the “gold standard” for GDM diagnosis. The OGTT has many drawbacks, the most serious flaw being that it is not reproducible[15]. It is expensive, time consuming and quite demanding for both the patient and the laboratory; furthermore, it is also not physiologic, quite unpleasant, uncorrected for body weight and its predictive value changes with ethnicity due to varying prevalence of GDM[16]. As a diagnostic test for DM in non-pregnant adults, many arguments have been made for keeping the OGTT[17] or avoiding it[15]. Due to the numerous problems of the OGTT, since 1997, the ADA favors the FPG with a lower threshold (7.0 mmol/L), rather than the OGTT for the diagnosis of DM in non-pregnant adults-even though this approach has its critics[18]. However, there has been no debate about the OGTT as a diagnostic test for GDM. Despite the potential of nausea and vomiting in pregnant women[19], the OGTT remains the cornerstone for diagnosis of GDM. Though many alternatives for screening of GDM have been explored, however, only the OGTT is currently acceptable as the diagnostic test.

Additional tests with OGTT may help to improve its performance. Measuring insulin with the 100 g OGTT may identify a subgroup of women who do not meet the ACOG criteria for GDM as they have only one abnormal glucose value. It has been found that women who have raised one hour serum glucose post oral glucose may need more intensive treatment[20]. The diagnosis of GDM using OGTT in pregnancy are further compounded by the variation in guidelines of the various preeminent expert panels for the glucose load used (75 g vs 100 g) and, as mentioned earlier, in varying diagnostic glucose thresholds suggested for diagnosis. Thus, a pregnant woman has the potential for undergoing the onerous OGTT three times: First one at booking, second one at between 24-28 wk, and the third one post-partum, six weeks after delivery.

FPG AS A SCREENING TEST

Over time, the definition of GDM, laboratory methods for glucose, and the screening and diagnostic criteria of GDM have evolved. Initially, in 1985, an anecdotal report[21] first used fasting blood glucose (along with glycosuria) for screening pregnant women. The interest in FPG surged when the expert committee of the ADA preferred using the FPG with lower thresholds rather than the OGTT for DM diagnosis in non-pregnant adults. In 1999, once the WHO approved this ADA approach, FPG became even more accepted and popular. Later, some studies while studying GDM screening, accidentally found that the FPG may have value[22]. The first comprehensive study on FPG as a screening test was conducted by Sacks et al[23]. In fact, Professor David Sacks due to his extensive initial and subsequent pioneering and iconic studies should be credited for putting FPG as a screening test for GDM on the world map.

FPG AS A SCREENING TEST: ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES

As a screening test for GDM, the FPG is very appealing: It cheap, reliable, reproducible, does not produce vomiting as seen with the OGTT/GCT. Thus, it can be administered in women unable to tolerate glucose drink and it takes less time than GCT. Using the FPG make GDM screening and diagnosis patient friendly[24]. However, the value of FPG for GDM screening remains uncertain. It is also not without problems. Incomplete fasting or an inability to fast for at least 8 h may not be easy for some pregnant women. In many poorer countries, multiple studies confirm that women find it hard to come to a clinic fasting. In some countries, fasting becomes hard if not impossible due to cultural beliefs that pregnant women should not fast for a long time, and commuting to the clinic takes an inordinately long time making it hard to fast. Often, the dropout rate is high when a pregnant woman is asked to come again for an OGTT after the clinic appointment. In some Asian populations, the FPG is inherently much lower (than Caucasians) but the postprandial is very high[25]. Thus, in India the authority on GDM, Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group India advocates “a single-step procedure”, i.e., the 2-h glucose without fasting glucose for the screening and diagnosis of GDM[26].

THE PROBLEMS OF STUDIES EVALUATING THE FPG IN SCREENING

The potential problems in interpreting studies of screening with FPG are as follows: (1) numerous studies evaluating FPG screening have a pre-selection bias. Patients are selected on the basis of clinical history or positive GCT; then, they undergo an OGTT which is not done on all patients and compared to the FPG. This creates a higher prevalence of GDM, improving the predictive value of the FPG[27]. The entire population must undergo both the screening and diagnostic test. Any surrogate screening test should cannot be assessed using a biased population and applying findings to a healthy population[28]; (2) results in different populations have varying prevalence and cannot be compared. However, standardized procedures and ethnicity customization will improve reproducibility; (3) FPG performance is also difficult to compare between studies as differing criteria are used for the diagnosis of GDM; (4) studies should use FPG independent of the OGTT to evaluate its performance. Using the FPG of the OGTT is erroneous as it assumes FPG is reproducible, which may not be so; and (5) in most reports, FPG performance is compared to the OGTT rather than examining how the test predicts poor health outcome. It has been suggested that the “gold-standard” for screening tests would be a universally agreed-on set of pregnancy outcomes[29].

BIASED REPORTS ON GDM SCREENING WITH FPG

As pointed earlier, to evaluate any screening test, the screening test and the diagnostic test must be done in the entire cohort. Otherwise, the evaluation is not accurate. In FPG screening, this is often not the case since only the positive screen patients (by clinical risk-factors or the 50-g GCT) undergo the OGTT. The FPG performance is compared to these fewer preselected patients who undergo the OGTT. These earlier studies by Sacks et al[23], de Aguiar et al[30], Agarwal et al[31,32], Rey et al[33], Soheilykhah et al[34], Senanayake et al[35] and Juutinen et al[36] suffer from this drawback (Table 2).

Table 2.

Studies about fasting plasma glucose as a screening test

| n | Cut-off mmol/L | Se (%) | Sp (%) | GDM (%) | AUC | Glucose load (g) | OG criteria1 | Ref. |

| Without selection bias | ||||||||

| 5010 | 4.5 | 81.5 | 54 | 7.6 | -- | 75 | WHO-1985 | Reichelt et al[37] |

| 558 | 4.8 | 81 | 76 | 10.2 | 0.897 | 100 | ADA | Perucchini et al[27] |

| 942 | 4.1 | > 70 | 13 | 0.766 | 75 | WHO-1985 | Tam et al[38] | |

| 1685 | 4.7 | 78.1 | 32.2 | 19.8 | 0.639 | 75 | WHO-1999 | Agarwal et al[39] |

| 500 | 4.7 | 88 | 95 | 7.2 | -- | 100 | C and C-1982 | Poomalar et al[41] |

| In early pregnancy | ||||||||

| 4507 | 4.6 | 80 | 43 | 6.7 | 0.7 | 75 | Sacks | Sacks et al[46] |

| 708 | 4.7 | 79.9 | 27.5 | 25.9 | 0.579 | 75 | WHO-1999 | Agarwal et al[47] |

| 4876 | 4.4 | 79 | 46.9 | 2.8 | 0.72 | 100 | C and C 100-g OGTT | Riskin-Mashiah et al[49] |

| 17186 | 4.3 | 84 | 29 | 12.4 | -- | 75 | IADPSG | Zhu et al[51] |

| 486 | -- | 47.2 | 77.4 | 10.9 | 0.623 | -- | FPG > 5.1 mmol/L | Yeral et al[53] |

Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) threshold with Specificity (Sp) corresponding to Sensitivity (Se) about 80%. AUC: Area under receiver operating characteristic curve; C and C: Carpenter-Coustan; ADA: American Diabetes Association; WHO: World Health Organization; IADPSG: International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups; OGTT: Oral glucose tolerance test; GDM: Gestational diabetes mellitus.

UNBIASED STUDIES ON FPG SCREENING FOR GDM

In 1998, the first comprehensive unbiased study of FPG screening for GDM was from Brazil (Table 2). Based on this study, Brazil became one of the few countries that recommend using FPG as a screening test for GDM in their national guidelines. Reichelt et al[37] analyzed the value of FPG as a screening test for GDM in 5010 women. The FPG performed well in the 16 (0.3%) women with frank diabetes (2-h > 11.1 mmol/L). However, in most of the other 363 (7.2%) women with reduced and compromised glucose tolerance (GIGT, 2-h = 7.8-11.0 mmol/L), despite the author’s claim, the performance was less than satisfactory. At their ideal cut-off of 4.7 mmol/L, both the sensitivity and specificity for women with GIGT were too low to be of any use (68.0%). If the threshold was decreased to 4.5% mmol/L, the sensitivity and specificity would be 81.5% and 54%; 51% women were less than this threshold. Thus, approximately one in two of their pregnant patients would have to proceed to the diagnostic OGTT to pick up 8 of 10 women with GDM. The increased number of false positives would make FPG as an inefficient screening test for GDM.

The 1999 study by Perucchini et al[27] evoked a lot of interest in FPG since it was published in the preeminent British Medical Journal. In 520 women who were pregnant the FPG performed better than the OGCT (Carpenter and Coustan criteria, C and C, using the 3-h, 100 g OGTT). FPG as a screening test had a good overall sensitivity and specificity. However, the number of women was small and the cohort was very small.

In 2000, Tam et al[38] from Hong Kong, inspired by the Reichelt study, compared 50 g glucose challenge, FPG, random glucose and fructosamine in 942 women who were pregnant. The prevalence of GDM (1980 WHO criteria) was 13%; since the area under a receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for GCT, FPG and 2-h glucose were similar, due to its simplicity, they recommended universal screening using FPG (cut-off 4.1 mmol/L) rather than the GCT.

In 2005, in one study involving 1685 pregnant women (WHO GDM criteria for the 75 g OGTT)[39], we found that the elevated number of women testing as false-positive made the FPG an inefficient test for GDM screening. Subsequently, a year later, we showed that[40] the variation in FPG performance may be due to the differing diagnostic criteria used for the diagnosis of GDM. The performance of FPG as a screening test with 4 different diagnostic criteria (using the same 75 g OGTT) was compared. In 4602 women, the FPG efficiency as a screening test was a function of the criteria used for diagnosis; it was excellent when the ADA-2003 criteria were used for diagnosis. With the other three criteria (WHO, ADIPS, European Association of Study on diabetes), at a satisfactory 85% sensitivity, the increased FPR and low specificity limited the value of FPG in screening.

More recently in 2013, Poomalar et al[41] compared FPG and GCT as screening tests. They found (like Peruchini’s study) that the ROC curve for FPG was better than GCT. However, their numbers were also small (500 women) and one is uncertain about the randomization of their subjects and the number of women missed during the study period.

FPG AS A SCREENING TEST FOR GDM IN EARLY PREGNANCY

In screening for GDM in early pregnancy (Table 2), two questions arise: (1) can the diagnosis of GDM be made in early pregnancy? and (2) how to interpret a raised FPG in early pregnancy.

In 2014, as stated earlier, the USPSTF concluded that the evidence was not enough to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for GDM in asymptomatic pregnant women before 24 wk of pregnancy[11]. It has been shown that higher first trimester FPG levels increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes[42]. Some experts have cogently argued that the IADPSG recommendation (endorsed by WHO) that an FPG of 5.1-6.9 mmol/L be classified as GDM in pregnancy cannot be accepted as there are no controlled trials that address the benefits of diagnosing and treating GDM in early pregnancy[43]. Even the ADA does not support the IADPSG view to diagnose GDM in early pregnancy.

Physiologically, in non-obese women, there is a fall in FPG in early pregnancy (median 0.11 mmol/L between 6-10 wk gestation), thereafter the glucose levels decrease little. Eight of ten studies showed a decrease in the first trimester[44]. A more recent study observed the same finding about FPG, while in the second to the third trimester, most studies have shown that the FPG changed little[45]. Thus, the thresholds used in third trimester for GDM diagnosis-on a theoretical basis-cannot be used in the first trimester.

The controversies about GDM diagnosis in early pregnancy notwithstanding, different studies have addressed this issue about FPG screening in early pregnancy with mixed results. Sacks et al[46] concluded that in their 5557 women during the first prenatal visit, despite good compliance, the poor specificity of FPG made it an inefficient test for screening for GDM. Similar conclusions were drawn by us[47] in a highrisk population. However, Corrado et al[48] observed that a FPG ≥ 5.1 mmol/L predicts GDM in later pregnancy. Similarly, Riskin-Mashiah et al[49] found that FPG may be used as a screening test to assess risk, but not as a diagnostic test in early pregnancy: A higher FPG in the first trimester, even though in the normal range, constituted a risk for GDM in later pregnancy. Alunni et al[50], found that implementing FPG (and HBA1c) screening in early pregnancy, nearly doubled the incidence of GDM and predicted the need for more pharmacotherapy. An extensive study by Zhu et al[51], involving 17186 women from China, showed that the first prenatal visit FPG correlated strongly with GDM at 24-28 wk gestation; however, they also assert that FPG ≥ 5.1 mmol/L should not be used to make a diagnosis of GDM in early pregnancy. They found that besides gestational age, chronological age also affects the FPG level as an independent variable. A study in 2004, on 246 women, found that FPG does not predict GDM in later pregnancy[52].

In 2014, Yeral et al[53] measured the FPG of 736 women during early pregnancy (1st visit) and randomized them (at 2nd visit) into: (1) the two-step 50 g GCT followed by 3-h, 100 g OGTT for positive results; and (2) the one step 2-h, 75 g OGTT repeating the tests in late pregnancy for women testing negative. GDM was diagnosed by Carpenter and Coustan criteria for 100 g OGTT and IADPSG criteria for the 75 g OGTT (in both second visit and late pregnancy). Within each cohort, the sensitivity in early pregnancy of 50 g GCT and 75 g OGTT was 68.2% and 87.1%, respectively. However, they reported the consolidated performance of FPG in early pregnancy (sensitivity 47.2%) for GDM diagnosed by the different criteria in the two groups. Since FPG performance is a function of the diagnostic criteria[40], individual performance of FPG is needed in each group to interpret their results further. Furthermore, the FPG results cannot be compared to other studies as two OGTT gold-standards were used.

In summary, most studies agree that the FPG in early pregnancy can predict risk for GDM in late pregnancy and possibly the need for medical therapy (and insulin). However, its poor specificity makes it an inappropriate test for screening test in early pregnancy - if and once the experts agree that GDM can be diagnosed in early pregnancy at all.

FASTING CAPILLARY GLUCOSE AS A SCREENING TEST FOR GDM

Few studies have addressed the value of fasting capillary glucose (FCG) as a screening test for GDM. There is an excellent correlation between fasting capillary glucose and fasting venous fasting glucose in pregnant women[54]; thus, the fasting capillary glucose shares the same performance characteristics as the fasting venous glucose.

Three studies have reported on the value of FCG as a screening test for GDM. These studies were done in populations of countries at low risk (Sweden)[55], moderate risk (Canada)[56] and highrisk (United Arab Emirates)[57] for GDM. Both studies in the high risk population and lowrisk population showed a similar AUC (87%), sensitivity (86%), specificity (55%) at FCG thresholds of 4.0 mmol/L and 4.7 mmol/L, respectively. The study from Canada was designed differently; it used FCG in preselected patients who tested positive with 50 g GCT with the specific aim to define a threshold which could rule of GDM without the need for an OGTT. The AUC was modest at 0.67. The fasting capillary glucose was positively associated with OGTT glucose values, and inversely associated with insulin sensitivity and pancreatic beta cell function. However, due to the overlap of FCG in the GDM and non-GDM populations, it could not be used to rule out GDM reliably. All three studies show that, like the FPG, the poor specificity precludes using FCG for GDM screening[58] since too many healthy women testing positive (false positives) would need the diagnostic OGTT. However, using the FCG (like FPG) may be of value to avoid a number of OGTTs needed, as discussed in the next section.

USING THE FPG TO DECREASE THE NUMBER OF OGTTS

The two-threshold method: Screening every pregnant woman for GDM with the OGTT, as advised by all expert panels (WHO, ADA, ACOG, CDA), is very demanding for the patient, the laboratory and the health-delivery system. Hence, there is a need for simpler, alternative screening tests. Screening tests are sensitive or specific, and generally, as the sensitivity increases, the specificity decreases and vice versa. So, to get the best of a screening test’s performance, Henderson, a chemical pathologist, advocates using two-thresholds[59]. In short, two threshold values, instead of one cut-off (as is the common practice), are utilized for the screening (e.g., fasting glucose for GDM). The higher cut-off, the specificity of which is innately increased, is used to “rule-in” the disease (GDM here); while the lower cut-off with its inherently increased sensitivity is used to “rule-out” the disease. Subjects with results in between these two selected cut-offs, are “indefinite” and would need the diagnostic test. All subjects above the higher threshold and below the lower threshold, do not need to be evaluated further. Thus, the FPG can be used to limit the number of OGTTs in any population. The author of this review is a chemical pathologist; thus, being aware of the literature in clinical chemistry has been applying this method to GDM.

Thus, since 2000, in our UAE population, we have used the two threshold “rule-in and rule-out” algorithm GDM in multiple studies[32,39,40,60,61] (Table 3). Depending on the FPG result, the OGTT can be avoided completely: (1) the upper chosen FPG cut-off, “rules-in” GDM with 100% specificity, and (2) the lesser FPG cut-off selected “rules-out” GDM with variable sensitivity. Table 3 shows that between 25%-70% women would not need the OGTT using this algorithm. Studies from China[62] and Brazil[63] have shown similar results.

Table 3.

Studies using fasting glucose to avoid oral glucose tolerance test

| OGTTs circumvented (n, %) | Thresholds (lower and higher) mmol/L | OGTT (g) | Diagnostic criteria | Comments | Ref. |

| 50.9 | 4.4 and 5.3 | 100 | ADA (C and C) | Biased sampling: Preselected by clinical/GCT | Agarwal et al[32] |

| 30.1 | 4.7 and -- | 75 | WHO-1999 | Only lower threshold used to rule out GDM | Agarwal et al[39] |

| 63.8 | 4.9 and 7.0 | 75 | ADA (C and C) | FPG screening dependent on GDM criteria | Agarwal et al[40] |

| 68.5 | 4.9 and 7.0 | 75 | ADA (C and C) | Glucometer used for FPG | Agarwal et al[60] |

| 50.1 | 4.7 and 7.0 | 75 | ADA (C and C) | Fasting capillary glucose used | Agarwal et al[57] |

| 50.6 | 4.4 and 5.1 | 75 | IADPSG | Pooled data from 4 studies | Agarwal et al[61] |

| 50.3 | 4.4 and 5.1 | 75 | IADPSG | Data from China corroborating UAE data | Zhu et al[62] |

| 61.0 | 4.4 and 5.1 | 75 | IADPSG | Data from Brazil corroborating UAE data | Trujillo et al[63] |

| 57.0 | 4.4 and 5.1 | 75 | IADPSG | Thresholds applied to HAPO Study | Agarwal et al[77] |

OGTT: Oral glucose tolerance test; ADA: American Diabetes Association; WHO: World Health Organization; IADPSG: International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups; C and C: Carpenter-Coustan; GCT: Glucose challenge test; GDM: Gestational diabetes mellitus; FPG: Fasting plasma glucose; UAE: United Arab Emirates; HAPO: Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome.

Therefore, using this approach, the FPG could tentatively avoid 33.0%-50.0% OGTTs, depending on the GDM diagnostic criteria[40,61]. Most countries still using the GCT for screening and OGTT for diagnosis may find it more cost-effective and simpler to switch to the OGTT for screening and diagnosis using the FPG decreasing the number of OGTTs needed-only after making sure this FPG-OGTT algorithm works in their population.

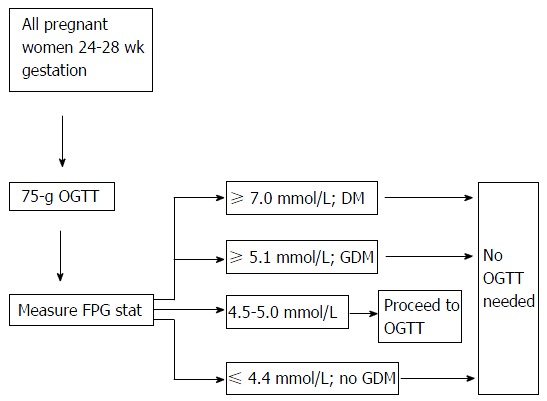

Rationale of using the 5.1 mmol/L and 4.4 mmol/L FPG thresholds: As per the criteria of the IADPSG, an FPG ≥ 5.1 mmol/L (independent of the other two values of the 75 g OGTT) confirms GDM. The lower cut-off of 4.4 mmol/L is derived from the elaborate HAPO study[7] which found that pregnancy outcomes were good when the FPG was ≤ 4.4 mmol/L. This approach is shown diagrammatically in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Suggested algorithm for gestational diabetes mellitus screening. OGTT: Oral glucose tolerance test; FPG: Fasting plasma glucose; GDM: Gestational diabetes mellitus; DM: Diabetes mellitus.

Shortcomings of the 2 threshold approach: There is a major difference in fasting glucose levels between 15 different centers distributed globally as shown by the HAPO study[64]. In some Asian populations, the FPG is very low but the postprandial is very high[25]. Thus, the suggested approach may, in many populations, may not circumvent too many OGTTs.

Another concern with approach is laboratory turn-around time (time taken to get the FPG result). If too long, this algorithm cannot be used. To decrease the turn-around time, a glucometer has been used to measure the fasting capillary glucose. The glucometer FCG has been found to be as good as the laboratory FPG with the excellent diagnostic correlation (κ = 0.95) for GDM[57].

COST OF SCREENING WITH FPG

Few studies analyzing cost of FPG screening compared to other screening methods are available. One study compared eight screening strategies[65]. It found that when the risk of GDM in a population was between 1.0%-4.2%, FPG followed by the OGTT was the cost-effective method. When risk was less (or more), other strategies were better. They also comment on another very important aspect of screening: Acceptance rates. The percentage of women who would undergo the screening test was as follows: OGTT, 40%; FPG, 50%; GCT, 70%; and RPG, 90%.

Another study[66], calculated the costs of three strategies: The 2-step (GCT + 100 g OGTT), the 1-step (75 g OGTT) and FPG of the OGTT to limit the number of OGTTs. Of the three strategies, the last one was the ideal approach.

FPG AS A POST-PARTUM SCREENING TEST AFTER DELIVERY

Since GDM is a marker for diabetes mellitus after delivery, it is obligatory to find the state of glucose tolerance in the immediate postnatal period and after long-term follow-up. All major guidelines recommend testing the mother 6-12 wk after birth of the baby; however there is a variation in the recommendations of the tests to use: FPG or the OGTT. The ADA and CDA recommend the OGTT, the NICE advocates FPG while the WHO and ACOG maintain that either test is acceptable[67]. The OGTT is more sensitive and picks up a higher number of women with dysglycemia, but the compliance is less (between 30%-70%). A ten year study showed that fasting glucose missed up 10% of women with DM and 60% women with impaired glucose tolerance[68]. We have reported that both tests show similar estimates for DM but widely discordant rates for glucose intolerance depending on the criteria used for DM diagnosis[69]. Kim et al[67] cogently argue that the decision could be based on the criteria used to pick up GDM antepartum. Thus, if the less stringent criteria are used (e.g., IADPSG) which picks up more women with dysglycemia post-partum, it may be better to use the FPG since the disparity between the two will decrease when women with lesser degrees of glucose intolerance are identified antepartum[69].

OTHER STUDIES ABOUT FPG AND GDM

Atilano et al[22] found that an abnormal FPG ≥ 5.8 mmol/L predicted GDM much better than an abnormal GCT. In this study, very high FPG values showed an excellent positive predictive value (96%), but the corresponding sensitivity at these high levels would remain poor. However, their patient population was pre-selected by an abnormal GCT giving a high prevalence of GDM of 22% and there are many doubts if the conclusions can be universally applied. Herrera et al[70] in 324 patients with GDM (75 g OGTT at 24-28 wk by C and C criteria) found 7.0% women who had isolated elevated FPG were more likely to need hypoglycemic agents, have higher body mass index and be Black or Hispanic. Another study compared FPG and hs-CRP in the first trimester and found the former was more sensitive and the latter more specific[71]. A higher maternal fasting glucose during 4-12 gestational weeks in 57454 women was associated with an increased birth weight and birth length of the offspring during 6-12 mo of the infant’s life[72].

STUDIES CHALLENGING THE USE OF FPG FOR GDM SCREENING

Many studies have found the FPG to be an inadequate test for GDM. Most of these studies are from South Asia, where women have lower FPG than their Caucasian counterparts. Balaji et al[73] found that FPG was inadequate as a screening test in their 1643 subjects from South India when compared to the WHO-1999 criteria. A threshold of 5.1 mmol/L had a sensitivity of just 24.0%. In another study[36] on 435 Finnish women with GDM (by the older criteria of the fourth International Conference-Workshop on GDM, a FPG threshold of 4.8 mmol/L picked up just 69.6% of the women with GDM). However, despite the poor sensitivity, FPG predicted the need for insulin. A 2003 study from Japan[74], found that in 749 Japanese women, a FPG threshold of 85.0 mg/dL had a sensitivity of 71.4% and 75.0 in first and second trimester, respectively; however, there were just 22 (2.9%) women with GDM (Japan Diabetes Association criteria).

FPG AND THE ROLE OF THE LABORATORY

FPG as a screening test for GDM: Other reviews

All reviews analyzing FPG as a screening test comment about the problem of analyzing the results. There is a lot of inconsistency and wide variation in the sensitivity and specificity found by these studies because of the ethnicity of the population, local prevalence and the diagnostic criteria used. In November 2012, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of the United States Department of Health and Human Services[3], Maryland analyzed 7 studies on FPG to screen for GDM. They were unable to make any definite conclusions about the FPG as a screening test. They found that the FPG was not good at predicting an abnormal OGTT. In 2010, Virally et al[75] looked at 8 reports commenting on screening for GDM using FPG. Their conclusion was that due to the heterogeneity the studies were impossible to compare; some were in highrisk populations and the diagnostic criteria were very variable. They were critical of the fact that none of the GDM studies related to perinatal outcomes. In 2013, the USPSTF published a systemic review of screening tests for GDM[29]. At a FPG threshold of 4.7 mmol/L, the sensitivity was similar to GCT. However, the positive likelihood ratio (LR) of 1.8 compared unfavorably to the positive LR of 5.9 of the GCT. Thus, they concluded that FPG and GCT were good at identifying women who do not have GDM but the FPG was not as good as GCT to identify women who have GDM. They also found that FPG did not diagnose GDM as frequently in Asian as non-Asian women.

CONCLUSION

In general, for the screening of GDM, the FPG is more sensitive than specific, i.e., it is better at “ruling-out” than “ruling-in” GDM[76]. Its performance is highly dependent upon the ethnicity of the population, the GDM prevalence, the diagnostic criteria and the FPG thresholds used. If these screening thresholds are kept low, the FPG will identify most women with GDM, but also an excessive number of women without GDM (due to poor specificity). Therefore, at an acceptable sensitivity, the poor specificity and high-false positive rate limit its usefulness as a screening test. However, as shown by studies originally from UAE, and reproduced by studies from China and similar studies from Brazil, it can still be very useful to decide if the OGTT is needed for diagnosis. Then, the FPG can help to reduce the number of onerous OGTTs required by nearly half[61,77]; however, 5%-15% patients with GDM would be missed, potentially women with lesser degrees of glucose intolerance - so health care will not be compromised. In summary, once its caveats are clearly understood, the FPG can simplify the screening and diagnosis of GDM. Thus, by circumventing the OGTT, the FPG can relieve many pregnant woman in the demanding work-up of glucose intolerance.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: Agarwal MM declares no conflict of interest related to this publication.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty Type: Endocrinology and Metabolism

Country of Origin: United Arab Emirates

Peer-Review Report Classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: April 6, 2016

First decision: May 17, 2016

Article in press: June 29, 2016

P- Reviewer: Cerf ME, Charoenphandhu N, Lovrencic MV, Schoenhagen P S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Diagnostic Criteria and Classification of Hyperglycaemia First Detected in Pregnancy. Geneva: WHO Press, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39 Suppl 1:S13–S22. doi: 10.2337/dc16-S005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartling L, Dryden DM, Guthrie A, Muise M, Vandermeer B, Aktary WM, Pasichnyk D, Seida JC, Donovan L. Screening and diagnosing gestational diabetes mellitus. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2012;(210):1–327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:1773–1779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agarwal MM, Dhatt GS, Othman Y. Gestational diabetes: differences between the current international diagnostic criteria and implications of switching to IADPSG. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29:544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, Persson B, Buchanan TA, Catalano PA, Damm P, Dyer AR, Leiva Ad, Hod M, Kitzmiler JL, Lowe LP, McIntyre HD, Oats JJ, Omori Y, Schmidt MI. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:676–682. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Dyer AR, Trimble ER, Chaovarindr U, Coustan DR, Hadden DR, McCance DR, Hod M, McIntyre HD, et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1991–2002. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hod M, Kapur A, Sacks DA, Hadar E, Agarwal M, Di Renzo GC, Cabero Roura L, McIntyre HD, Morris JL, Divakar H. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) Initiative on gestational diabetes mellitus: A pragmatic guide for diagnosis, management, and care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131 Suppl 3:S173–S211. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(15)30033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UK National Screening Committee. Criteria for appraising the viability, effectiveness and appropriateness of a screening programme. 2015. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/evidence-review-criteria-national-screening-programmes. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott DA, Loveman E, McIntyre L, Waugh N. Screening for gestational diabetes: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6:1–161. doi: 10.3310/hta6110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moyer VA. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:414–420. doi: 10.7326/M13-2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cosson E, Benbara A, Pharisien I, Nguyen MT, Revaux A, Lormeau B, Sandre-Banon D, Assad N, Pillegand C, Valensi P, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic performances over 9 years of a selective screening strategy for gestational diabetes mellitus in a cohort of 18,775 subjects. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:598–603. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simmons D, Moses RG. Gestational diabetes mellitus: to screen or not to screen?: Is this really still a question? Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2877–2878. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duran A, Sáenz S, Torrejón MJ, Bordiú E, Del Valle L, Galindo M, Perez N, Herraiz MA, Izquierdo N, Rubio MA, et al. Introduction of IADPSG criteria for the screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus results in improved pregnancy outcomes at a lower cost in a large cohort of pregnant women: the St. Carlos Gestational Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2442–2450. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson MB. Counterpoint: the oral glucose tolerance test is superfluous. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1883–1885. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanna FW, Peters JR. Screening for gestational diabetes; past, present and future. Diabet Med. 2002;19:351–358. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuomilehto J. Point: a glucose tolerance test is important for clinical practice. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1880–1882. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dekker JM, Balkau B. Counterpoint: impaired fasting glucose: The case against the new American Diabetes Association guidelines. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1173–1175. doi: 10.2337/diacare.2951173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agarwal MM, Punnose J, Dhatt GS. Gestational diabetes: problems associated with the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2004;63:73–74. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Cianni G, Seghieri G, Lencioni C, Cuccuru I, Anichini R, De Bellis A, Ghio A, Tesi F, Volpe L, Del Prato S. Normal glucose tolerance and gestational diabetes mellitus: what is in between? Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1783–1788. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mortensen HB, Mølsted-Pedersen L, Kühl C, Backer P. A screening procedure for diabetes in pregnancy. Diabete Metab. 1985;11:249–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atilano LC, Lee-Parritz A, Lieberman E, Cohen AP, Barbieri RL. Alternative methods of diagnosing gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1158–1161. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sacks DA, Greenspoon JS, Fotheringham N. Could the fasting plasma glucose assay be used to screen for gestational diabetes? J Reprod Med. 1992;37:907–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rey E. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus. A simple test may make it easier to study whether screening is worthwhile. BMJ. 1999;319:798–799. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7213.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wijeyaratne CN, Ginige S, Arasalingam A, Egodage C, Wijewardhena K. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus: the Sri Lankan experience. Ceylon Med J. 2006;51:53–58. doi: 10.4038/cmj.v51i2.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anjalakshi C, Balaji V, Balaji MS, Ashalata S, Suganthi S, Arthi T, Thamizharasi M, Seshiah V. A single test procedure to diagnose gestational diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol. 2009;46:51–54. doi: 10.1007/s00592-008-0060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perucchini D, Fischer U, Spinas GA, Huch R, Huch A, Lehmann R. Using fasting plasma glucose concentrations to screen for gestational diabetes mellitus: prospective population based study. BMJ. 1999;319:812–815. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7213.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sox HC, Higgins MC, Owens DK. In: Medical Decision Making. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell. NJ, USA, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donovan L, Hartling L, Muise M, Guthrie A, Vandermeer B, Dryden DM. Screening tests for gestational diabetes: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:115–122. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-2-201307160-00657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Aguiar LG, de Matos HJ, Gomes MB. Could fasting plasma glucose be used for screening highrisk outpatients for gestational diabetes mellitus? Diabetes Care. 2001;24:954–955. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.5.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agarwal MM, Hughes PF, Ezimokhai M. Screening for gestational diabetes in a highrisk population using fasting plasma glucose. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2000;68:147–148. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(99)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agarwal MM, Hughes PF, Punnose J, Ezimokhai M. Fasting plasma glucose as a screening test for gestational diabetes in a multi-ethnic, highrisk population. Diabet Med. 2000;17:720–726. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rey E, Hudon L, Michon N, Boucher P, Ethier J, Saint-Louis P. Fasting plasma glucose versus glucose challenge test: screening for gestational diabetes and cost effectiveness. Clin Biochem. 2004;37:780–784. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soheilykhah S, Rashidi M, Mojibian M, Dara N, Jafari F. An appropriate test for diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27:785–788. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2010.540598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senanayake H, Seneviratne S, Ariyaratne H, Wijeratne S. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus in southern Asian women. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2006;32:286–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2006.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Juutinen J, Hartikainen AL, Bloigu R, Tapanainen JS. A retrospective study on 435 women with gestational diabetes: fasting plasma glucose is not sensitive enough for screening but predicts a need for insulin treatment. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1858–1859. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.12.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reichelt AJ, Spichler ER, Branchtein L, Nucci LB, Franco LJ, Schmidt MI. Fasting plasma glucose is a useful test for the detection of gestational diabetes. Brazilian Study of Gestational Diabetes (EBDG) Working Group. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1246–1249. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.8.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tam WH, Rogers MS, Yip SK, Lau TK, Leung TY. Which screening test is the best for gestational impaired glucose tolerance and gestational diabetes mellitus? Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1432. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.9.1432b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agarwal MM, Dhatt GS, Punnose J, Koster G. Gestational diabetes in a highrisk population: using the fasting plasma glucose to simplify the diagnostic algorithm. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;120:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agarwal MM, Dhatt GS, Punnose J. Gestational diabetes: utility of fasting plasma glucose as a screening test depends on the diagnostic criteria. Diabet Med. 2006;23:1319–1326. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poomalar GK, Rangaswamy V. A comparison of fasting plasma glucose and glucose challenge test for screening of gestational diabetes mellitus. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33:447–450. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2013.771156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riskin-Mashiah S, Younes G, Damti A, Auslender R. First-trimester fasting hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1639–1643. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McIntyre HD, Sacks DA, Barbour LA, Feig DS, Catalano PM, Damm P, McElduff A. Issues With the Diagnosis and Classification of Hyperglycemia in Early Pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:53–54. doi: 10.2337/dc15-1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mills JL, Jovanovic L, Knopp R, Aarons J, Conley M, Park E, Lee YJ, Holmes L, Simpson JL, Metzger B. Physiological reduction in fasting plasma glucose concentration in the first trimester of normal pregnancy: the diabetes in early pregnancy study. Metabolism. 1998;47:1140–1144. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(98)90290-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riskin-Mashiah S, Damti A, Younes G, Auslander R. Normal fasting plasma glucose levels during pregnancy: a hospital-based study. J Perinat Med. 2011;39:209–211. doi: 10.1515/jpm.2010.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sacks DA, Chen W, Wolde-Tsadik G, Buchanan TA. Fasting plasma glucose test at the first prenatal visit as a screen for gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:1197–1203. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agarwal MM, Dhatt GS, Punnose J, Zayed R. Gestational diabetes: fasting and postprandial glucose as first prenatal screening tests in a highrisk population. J Reprod Med. 2007;52:299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corrado F, D’Anna R, Cannata ML, Interdonato ML, Pintaudi B, Di Benedetto A. Correspondence between first-trimester fasting glycaemia, and oral glucose tolerance test in gestational diabetes diagnosis. Diabetes Metab. 2012;38:458–461. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riskin-Mashiah S, Damti A, Younes G, Auslender R. First trimester fasting hyperglycemia as a predictor for the development of gestational diabetes mellitus. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;152:163–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alunni ML, Roeder HA, Moore TR, Ramos GA. First trimester gestational diabetes screening - Change in incidence and pharmacotherapy need. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;109:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2015.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu WW, Yang HX, Wei YM, Yan J, Wang ZL, Li XL, Wu HR, Li N, Zhang MH, Liu XH, et al. Evaluation of the value of fasting plasma glucose in the first prenatal visit to diagnose gestational diabetes mellitus in china. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:586–590. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bhattacharya SM. Fasting or two-hour postprandial plasma glucose levels in early months of pregnancy as screening tools for gestational diabetes mellitus developing in later months of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30:333–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2004.00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yeral MI, Ozgu-Erdinc AS, Uygur D, Seckin KD, Karsli MF, Danisman AN. Prediction of gestational diabetes mellitus in the first trimester, comparison of fasting plasma glucose, two-step and one-step methods: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Endocrine. 2014;46:512–518. doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-0111-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dhatt GS, Agarwal MM, Othman Y, Nair SC. Performance of the Roche Accu-Chek active glucose meter to screen for gestational diabetes mellitus using fasting capillary blood. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13:1229–1233. doi: 10.1089/dia.2011.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fadl H, Ostlund I, Nilsson K, Hanson U. Fasting capillary glucose as a screening test for gestational diabetes mellitus. BJOG. 2006;113:1067–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anderson V, Ye C, Sermer M, Connelly PW, Hanley AJ, Zinman B, Retnakaran R. Fasting capillary glucose as a screening test for ruling out gestational diabetes mellitus. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2013;35:515–522. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30909-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Agarwal MM, Dhatt GS, Othman Y, Gupta R. Gestational diabetes: fasting capillary glucose as a screening test in a multi-ethnic, highrisk population. Diabet Med. 2009;26:760–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Agarwal MM, Dhatt GS, Bali N. Fasting capillary glucose as a screening test for gestational diabetes mellitus. BJOG. 2007;114:237–238; author reply 237-238. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Henderson AR. Assessing test accuracy and its clinical consequences: a primer for receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. Ann Clin Biochem. 1993;30(Pt 6):521–539. doi: 10.1177/000456329303000601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Agarwal MM, Dhatt GS, Safraou MF. Gestational diabetes: using a portable glucometer to simplify the approach to screening. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2008;66:178–183. doi: 10.1159/000140602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Agarwal MM, Dhatt GS, Shah SM. Gestational diabetes mellitus: simplifying the international association of diabetes and pregnancy diagnostic algorithm using fasting plasma glucose. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2018–2020. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu WW, Fan L, Yang HX, Kong LY, Su SP, Wang ZL, Hu YL, Zhang MH, Sun LZ, Mi Y, et al. Fasting plasma glucose at 24-28 weeks to screen for gestational diabetes mellitus: new evidence from China. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2038–2040. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Trujillo J, Vigo A, Reichelt A, Duncan BB, Schmidt MI. Fasting plasma glucose to avoid a full OGTT in the diagnosis of gestational diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;105:322–326. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sacks DA, Hadden DR, Maresh M, Deerochanawong C, Dyer AR, Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Coustan DR, Hod M, Oats JJ, et al. Frequency of gestational diabetes mellitus at collaborating centers based on IADPSG consensus panel-recommended criteria: the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:526–528. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Round JA, Jacklin P, Fraser RB, Hughes RG, Mugglestone MA, Holt RI. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus: cost-utility of different screening strategies based on a woman’s individual risk of disease. Diabetologia. 2011;54:256–263. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1881-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Agarwal MM, Dhatt GS, Othman Y. Gestational diabetes in a tertiary care hospital: implications of applying the IADPSG criteria. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;286:373–378. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2324-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim C, Chames MC, Johnson TR. Identifying post-partum diabetes after gestational diabetes mellitus: the right test. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;1:84–86. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70044-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Myers JE, Hasan X, Maresh MJ. Post-natal assessment of gestational diabetes: fasting glucose or full glucose tolerance test? Diabet Med. 2014;31:1133–1137. doi: 10.1111/dme.12503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Agarwal MM, Punnose J, Dhatt GS. Gestational diabetes: implications of variation in post-partum follow-up criteria. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;113:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2003.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Herrera K, Brustman L, Foroutan J, Scarpelli S, Murphy E, Francis A, Rosenn B. The importance of fasting blood glucose in screening for gestational diabetes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:825–828. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.935322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ozgu-Erdinc AS, Yilmaz S, Yeral MI, Seckin KD, Erkaya S, Danisman AN. Prediction of gestational diabetes mellitus in the first trimester: comparison of C-reactive protein, fasting plasma glucose, insulin and insulin sensitivity indices. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:1957–1962. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.973397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dong L, Liu E, Guo J, Pan L, Li B, Leng J, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Li N, Hu G. Relationship between maternal fasting glucose levels at 4-12 gestational weeks and offspring growth and development in early infancy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;102:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Balaji V, Balaji M, Anjalakshi C, Cynthia A, Arthi T, Seshiah V. Inadequacy of fasting plasma glucose to diagnose gestational diabetes mellitus in Asian Indian women. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94:e21–e23. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maegawa Y, Sugiyama T, Kusaka H, Mitao M, Toyoda N. Screening tests for gestational diabetes in Japan in the 1st and 2nd trimester of pregnancy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2003;62:47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(03)00146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Virally M, Laloi-Michelin M. Methods for the screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus between 24 and 28 weeks of pregnancy. Diabetes Metab. 2010;36:549–565. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Agarwal MM, Dhatt GS. Fasting plasma glucose as a screening test for gestational diabetes mellitus. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;275:81–87. doi: 10.1007/s00404-006-0245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Agarwal MM, Weigl B, Hod M. Gestational diabetes screening: the low-cost algorithm. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;115 Suppl 1:S30–S33. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(11)60009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]