Abstract

Pressure volume (PV) based analysis, using classic hemodynamic principles, has served as a basis for our understanding of cardiac physiology and disease states for decades. However, PV analysis has been restricted to primarily the basic research setting and for preclinical testing and has not be widely applied in part because of the invasive nature of the procedure and the expertise required to obtain adequate data using the conductance catheter. Development of single beat methodologies that rely on echocardiographic measurements of ventricular volume and Doppler and peripheral estimates of ventricular pressure and timing of the cardiac cycle has enabled broader application of PV analysis. This review explores the physiologic background, basic methodology, and recent and potential future applications of noninvasive PV analysis.

Keywords: Heart valve diseases, Heart failure, Echocardiography, Hemodynamics

Keywords: Valvola aortica, malattia; Scompenso cardiaco; Ecocardiografia; Emodinamica

Abstract

Da decenni, la nostra comprensione della fisiologia cardiaca e delle condizioni patologiche del cuore si basa su un’analisi pressione-volume (PV), guidata dai principi classici dell’emodinamica. Tuttavia, l’utilizzo dell’analisi PV è stato prevalentemente limitato alla ricerca di base e a test preclinici. L’analisi PV non è stata applicata in modo estensivo, sia per la natura invasiva della procedura, sia per il grado di esperienza necessario per ottenere dati adeguati con il catetere a conduttanza. Lo sviluppo di metodiche su singolo battito, basate su misurazioni ecocardiografiche dei volumi ventricolari e su stime Doppler e periferiche delle pressioni ventricolari e del timing del ciclo cardiaco, ha permesso una più ampia applicazione dell’analisi pressione-volume. Questa review esplora il background fisiologico, la metodologia di base, le applicazioni recenti e le possibili applicazioni future dell’analisi PV non invasiva.

Quantification of ventricular pump function is fundamental to the practice of cardiology. In the 1890s, Otto Frank1 introduced the pressure volume (PV) diagram as a means of characterizing left ventricular performance. For decades, classic hemodynamic principals based on the PV paradigm have been used to characterize ventricular systolic and diastolic function.2–6 Seminal studies demonstrated that with simultaneous invasive measures of pressure using high fidelity manometers and ventricular volume using a conductance catheter or sonomicrometry, data could be obtained that was considered the gold standard for the hemodynamic assessment of cardiac performance.5–7 However, such techniques were often employed in the basic research setting and during preclinical testing in order to characterize the intact heart’s performance under various situations including the effect of a pharmacologic agent or characterization of a disease state. When invasive PV analyses were used to evaluate clinical diseases in humans, the studies were often small to moderate in size (N.=3 to 90)8–13 and rarely did they employ serial measures.9, 11, 12

The development of noninvasive tomographic techniques to accurately measure left ventricular volumes including two and three dimensional echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, coupled with non-invasive methods to estimate pressures has paved the wave for new methods that can accurately estimate PV relations in humans. These single-beat techniques.14, 15 which have been delineated to adequately characterize the end systolic and end diastolic PV relations has led to the broader application of the PV loop paradigm. This paradigm has been employed to enhance our understanding mechanisms that contribute cardiovascular disease, particularly heart failure and responses to therapies.16–20 This review explores the physiologic background, basic methodology, and recent and potential future applications of noninvasive PV analysis.

Overview of PV loop and derived measures

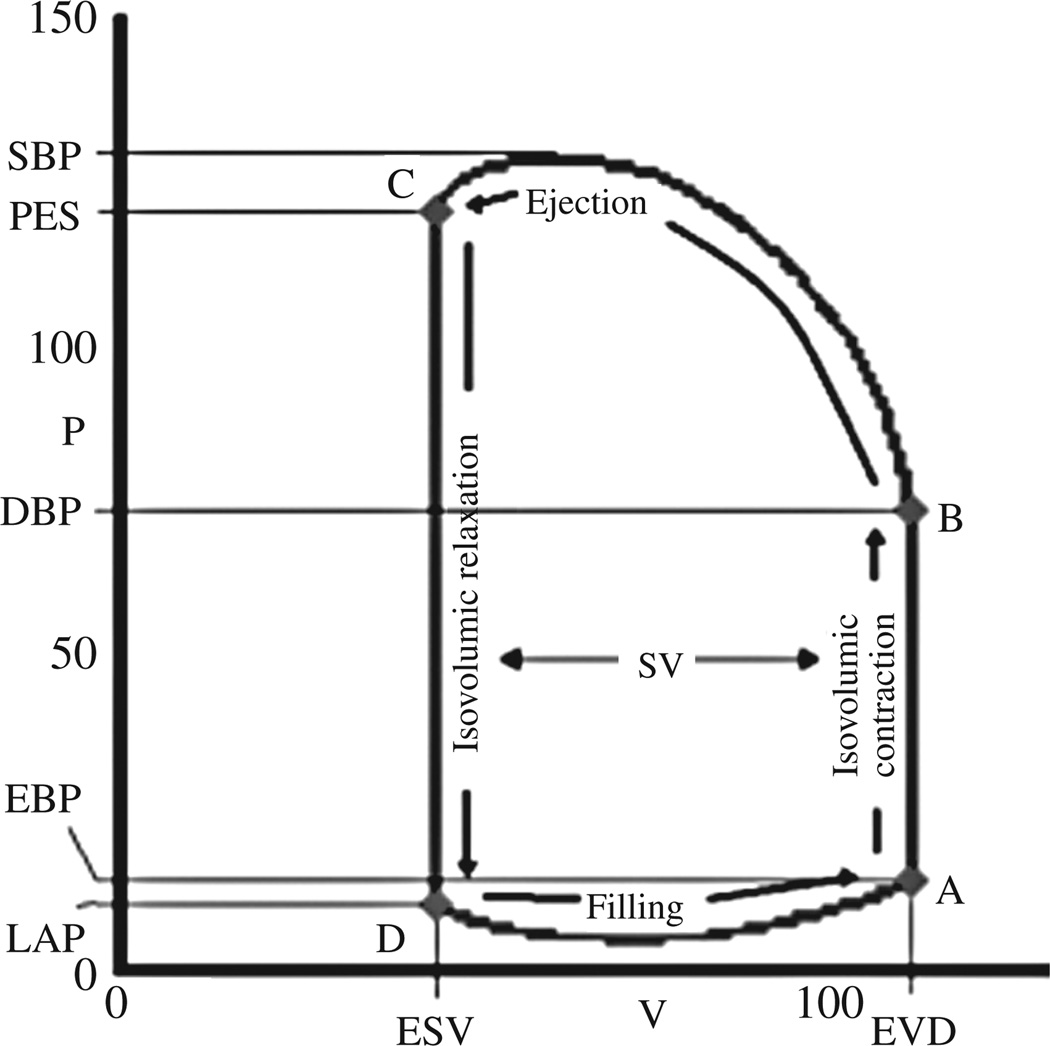

A single PV loop is shown in Figure 1. The relevant aspects and their relationship to the cardiac cycle are delineated. The point of maximal volume and minimal pressure (point A on Figure 1) corresponds to mitral valve closure, the onset of systole. This is often referred to the as the end diastolic PV point. Isovolumetric contraction results in a rapid increase in left ventricular pressure till left ventricular pressure exceed aortic diastolic pressure and ejection begins (point B). Ejection continues until time C when aortic valve closure occurs, which is often referred to as the end systolic pressure/ end systolic volume point. Indeed the relation of the end systolic pressure to the end systolic volume has been employed for decades as an index of ventricular contractile function.6, 7 After aortic valve closure and before mitral valve opening (point D), the ventricle isovolumetrically relaxes, until left ventricular pressure falls below left atrial pressure at which point left ventricular filling begins. From the PV loop, various pressures (end diastolic, end systolic, peak systolic, diastolic aortic and left atrial pressure) and volumes (end diastolic and end systolic volume and their difference, the stroke volume) can be readily identified (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The cardiac cycles plotted on pressure and volume axes. The cardiac cycles begins with mitral closure (A) followed by isovolumetric contraction. When LV pressure exceeds aortic pressure the aortic valve open and ejection begins (B). The point of maximal ventricular stiffness corresponds to the end of systole (C). This is followed by isovolumetric relaxation. When LV pressure drops below LA pressure the mitral opens and LV filling begins (D). Common physiologic parameters can be derived from the PV loop. On the volume axis: End systolic volume (ESV) and end diastolic volume (EDV), stroke volume (SV), and ejection fraction (SV/EDV). On the pressure axis: systolic blood pressure (SBP), end systolic pressure (Pes), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), end diastolic pressure (EDP) and left atrial pressure (LAP).

In a given state the PV loop is constrained by the ventricular properties which are delineated by the time varying elastance model21 in which the properties of the muscle vary in a cyclic manner during the period of the cardiac cycle between each beat. With each cardiac cycle the muscle fibers in the ventricular wall contract and relax causing the chamber to stiffen (reaching a maximal stiffness at the end of systole) and then to become less stiff during the relaxation phase (reaching its minimal stiffness at end-diastole). Thus, the end systolic PV relation (ESPVR) reflects the stiffness of the chamber at the point of maximal myofilament activation, also called the end systolic elastance (Ees) or maximum elastance (Emax). The ESPVR is characterized by both a slope and volume axis intercept (V0) which concomitantly reflect changes in chamber contractility (Figure 2B). For example, when inotropes are introduced, the ESPVR shifts upward (greater end-systolic pressure at any given end systolic volume). As the ESPVR is relatively linear within physiologic conditions, it can be represented by the equation ESP=V0+EesESV; where ESP is end systolic pressure, ESV is end systolic volume, V0 is the volume axis intercept of ESPVR, and Ees is the slope of ESPVR. As such an increase in systolic pump performance or contractility can be manifest by an decrease in V0 or an increase is Ees.22 To account for covariance in Ees and V0,22 both of which determine the position of the ESPVR, the values of these parameters derived for group of subjects can be used to predict the V120 (the volume to achieve an end-systolic pressure of 120 mmHg),23 which is calculated from the Ees and V0 of each patient: V120=V0+120/Ees.

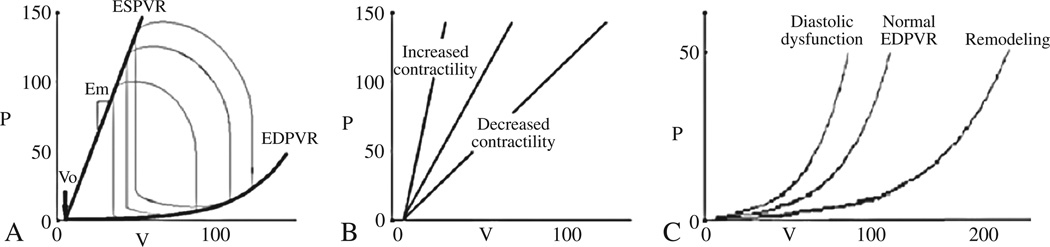

Figure 2.

Pressure-volume analyses demonstrating the normal PV loop and the determinants of ventricular function, including the ESPVR (characterized by the slope [Ees] and the volume axis intercept [V0] and the EDPVR (panel A). Shifts in the ESPVR are often equated with changes in inotropic state (panel B), while shifts in EDPVR toward small volumes or reduced capacitance (diastolic dysfunction) or larger volumes or increased capacitance (remodeling) shown in panel C.

At the other extreme of the cardiac cycle, the EDPVR reflects the passive performance of the ventricle at complete myofilament inactivation. In contrast to the ESPVR, the EDPVR is non-linear with an initial flat portion (relatively high compliance) followed by a phase of rapidly increasing pressure for small increases in volume (lower compliance). The relationship between end diastolic pressure (EDP) and end diastolic volume (EDV) is characterized by several non-linear equations with the most commonly employed being EDP=βEDVα; where α is a curve-fitting constant and β is a diastolic stiffness constant.14 Shifts in the EDPVR signify changes in ventricular capacitance (the volume that the ventricle holds at a given pressure). Compliance is the slope of the EDPVR (change in filling pressure required to create a giving change in filling pressure) and is to be distinguished from capacitance. Because the EDPVR is nonlinear, the compliance changes as the ventricle fills. Upward and leftward shifts in the EDPVR indicate a reduced capacitance and are referred to as diastolic dysfunction. Downward and rightward shifts in the EDPVR represent an increase in ventricular capacitance as is called ventricular remodeling (Figure 2C).

In a given state, the PV loop is constrained within the ESPVR and EDPVR and the shape and position of the PV loop depends on loading conditions. Preload is the hemodynamic load or stretch on the myocardial wall at the end of diastole just before contraction begins (Figure 2A). From the PV loop, for the intact human heart, there are several possible measures of preload including the end diastolic volume or end diastolic pressure (Figure 1A, time A). Afterload is the hydraulic load imposed on the ventricle during ejection (Figure 3). This load, in the absence of pathologic conditions such as mitral valvular regurgitation and aortic valve stenosis, is usually imposed on the heart by the arterial system. While several different measures of afterload are used, in the PV plane, arterial properties can be represented by arterial elastance (Ea).24 Ea is a lumped index of arterial properties that accounts for aortic impedance, peripheral resistance, and arterial compliance, and is depicted on the PV loop as the slope of the line that intersects LV end systolic pressure (Pes) and end diastolic volume on the volume axis. Ea is equal to the Pes divided by the stroke volume (SV); Ea=Pes/SV.24–26

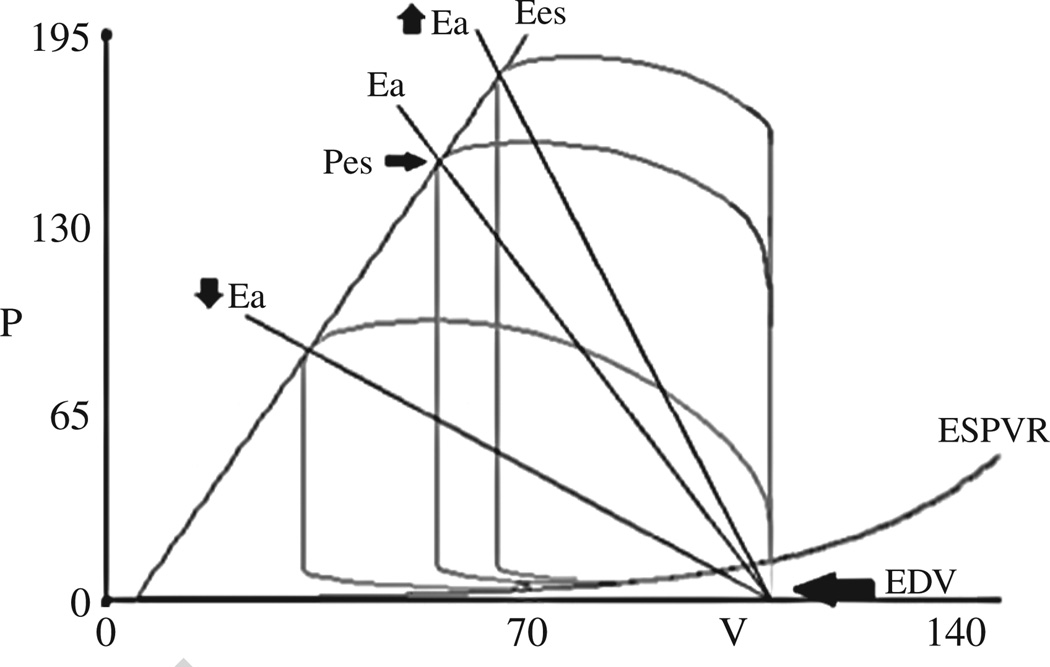

Figure 3.

PV loop with Ea, a lumped index of afterload, is depicted on the PV loop as the slope of the line that intersects LV end systolic pressure (Pes) and end diastolic volume on the volume axis. The impact of changing Ea (afterload) on PV loop is shown. Lower Ea results in an increased stroke volume and lower systolic blood pressure, whereas raising Ea results in the opposite effect.

While ESPVR and EDPVR form the basis of PV loop analysis and interpretation and can be used to describe specific aspects of ventricular function, interpretation of each parameter in isolation has limitations. Zile27 identified that in the setting of diastolic dysfunction (an upward and leftward shift in the EDPVR), which occurs in the setting of hypertension, aortic stenosis and coronary artery disease, Emax (which is based on total systolic pressure) does not adequately reflect contractile dysfunction. This is because in the setting of reduced capacitance, developed pressure (end systolic pressure minus end diastolic pressure) does not equate with total systolic pressure.27 Additionally, the methods to index end systolic elastance in the setting of structural abnormalities of the left ventricle such as LVH are not well defined. For example, in the setting of LVH, a normal value for end systolic elastance is actually low, when indexed for the LV mass.

Given the limitations of interpreting the ESPVR or EDPVR in isolation, it has been proposed that the area between the EDPVR and ESPVR be measured to index overall pump function. Suga and colleagues introduced the concept of PV area to quantify ventricular energetic.28–32 The area between EDPVR and ESPVR as a function of EDP,33 termed the isovolumic PV area (PVAiso) is independent of afterload and can be calculated non-invasively as a function of LVEDP from single beat techniques that define the EDPVR and ESPVR (Figure 4). The PVA correlates with myocardial oxygen consumption.29 The area within the PV loop represents the external mechanical work or stroke work (Figure 4B).31 The area bound by the EDPVR, ESPVR and the systolic limbs of the PV loop represents the potential energy of the LV per cardiac cycle (area BC). The ratio of the area within the PV loop to the total potential energy is known as ventricular efficiency.31 Measures that evaluate more than systolic or diastolic function in isolation and integrate overall pump function, such as PVA, may be more sensitive indices of ventricular function and earlier markers of impaired performance,34 especially in the setting of reduced diastolic capacitance.27

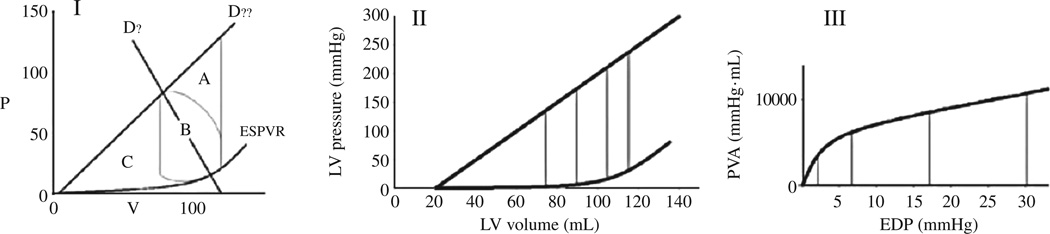

Figure 4.

Panel I shows the relationship between the afterload independent measure of PVA (area ABC), and the potential energy of the ventricle (area BC), and the actual stroke work (area B). Left ventricular efficiency can be expressed as area B divided by either ABC or BC. Panels II and III demonstrate how PV iso is calculated from the PV diagram. One value for PVA iso can be obtained from each end diastolic PV point (in this case LVEDP of 2, 7, 17, 30 mmHg correspond to PVA of 4304, 6507, 9652, 10504 mmHg*mL, respectively). The relationship between PVAiso and EDP is constructed from the EDPVR and ESPVR in panel I and is shown graphically in panel II.

Methods for PV loop derivation

The initial studies to derive PV loops used invasive catheter based methods to measure left ventricular chamber pressure and volume.35, 36 Loading conditions are altered across multiple cardiac cycles usually by preload reduction using a balloon to occlude the inferior vena with serial simultaneous ventricular pressure and volume measurement obtained using a conductance catheter (Figure 2A).37 This approach has been performed in humans and validated in canine models.38 The conductance catheter provides continuous and instantaneous measurement of left ventricular volume based on measuring the time-varying electrical conductance of blood in the left ventricle.35, 39 Based on Ohm’s Law the conductance is approximately linear to the volume of blood in the ventricle. Practically, the ventricle is divided in segments by evenly placed electrodes at the tip of a catheter that spans the LV cavity. The volume is calculated by summing the conductance measured across segments. Calibration relies on correcting for the conductance of surrounding structures, called parallel conductance volume (Vc). Vc is calculated by temporarily altering the conductivity of blood by injecting a small amount of hypertonic saline. The second correction factor is slope factor, alpha. Alpha is calculated by dividing the conductance stroke volume by the reference usually thermodilution) stroke volume. Accurate calibration is essential for valid interpretation of PV loops derived using conductance catheters and failure to accurately calibrate the device can lead to spurious results. Thus, because of the invasive nature of this approach and the expertise required to obtain appropriately calibrated data, these techniques have been restricted to small sets of patients by highly skilled investigators at single centers, limiting the application of this approach to larger populations and to single, not serial measures.

Because of these limitations, noninvasive methods to estimate measures typically derived from invasive PV relationships have been developed. The advantages of noninvasive methodology are obvious. It can be applied to large numbers of patients and assessment can be performed at multiple time points to evaluate changes in cardiac function chronically and serially observing the natural history of a disease or the response to pharmacologic or device based therapy. With three dimensional imaging modalities, accurate measurement of ventricular volume can be obtained without the need for an external reference or calibration. However, the “Achilles heel” of the noninvasive approach to derive the PV parameters is the reliance on peripheral blood pressure measurement to estimated LV end systolic pressure and Doppler echocardiography to estimate LV end diastolic pressure (Table I). Despite these limitations, recent data suggests that the performance of these single beat techniques is quite remarkable across a wide range of ventricular volumes.40

TABLE I.

Comparison of invasive and noninvasive pressure volume loop methods.

| Invasive method | Non invasive method |

|---|---|

| Advantages | Advantages |

| — High fidelity pressure measurements | — Noninvasive |

| — Continuous measurement of pressure and volume throughout cardiac cycle |

— Easily performed serially and in large patient samples |

| — Accurate imaging based measurement of volume | |

| Disadvantages | Disadvantages |

| — Invasive | — Peripheral or Doppler derived estimates of pressure which have measurement error |

| — Difficult to perform serially or in large patient samples | — Data not continuous and derived from single, using resting condition |

| — Relies on conducatance for measurement of volume, which is subject to calibration errors and requires expertise |

— Only estimates of PV indices, validated in small series |

Several single beat techniques15, 21, 41–43 were developed in the early 1990s and throughout 2000, to estimate the ESPVR (Ees and V0). The simplest approach relies on the ratio of end systolic pressure and volume7 and assumes V0=0. Additional methods to derive both the slope and volume intercept of the ESPVR relies on either bilinearity to derive elastance for the isovolumic and ejection phases of systole21 or nonlinear least squares approximation to obtain the volume intercept V041 Others select two points from the PV loop: at end systole and at a second systolic time point. For a given ratio of end systolic elastance and elastance at the second time point(End), V0 and the slopes of the line connecting the end systolic time point to V0 can be obtained.42 Chen and Kass derived an entirely non-invasive single beat technique to measure the ESPVR.15 Their approach has the advantage of simplicity as they do not incorporate bilinearity and they derive rather than measure End. This approach has been validated in humans with data derived from routine cuff blood pressure measurements, Doppler echocardiographic measures of isovolumetric contraction, and ejection duration, and measurements of end diastolic and end systolic volumes.15 The correlation with invasively derived estimates of V0 and Ees is high; the regression SEE was 0.64, with the mean error of 0.43±0.5 mmHg/ml with about 75% of the estimates falling within 0.6 mm Hg/ml of the measured value.15

Finally, more than a decade after initial efforts to derive single beat methods to estimate the ESPVR, a method for estimating the EDPVR has recently been delineated. The EDPVR was more difficult to estimate because of the curvelinear nature of the relationship between pressure and volume. A seminal finding14 is that when diastolic pressure volume relations are normalized to ventricular volume to yield volume normalized EDPVRs the curves are very similar across species and cardiac conditions. This indicated the existence of a common underlying shape of the EDVPR which can be expressed by a simple analytical expression. Using the approach, a noninvasive single beat estimation of EDVPR was developed,14 that required a single end diastolic pressure volume point to estimate the entire EDPVR. End diastolic pressure was either measured directly or estimated by Doppler echocardiographic using validated formulas44–46 and end diastolic volume was measured by tomographic techniques. Using a curve fitting formula, EDP=βEDVα; where α is a curve-fitting constant and β is a diastolic stiffness constant and the derived constants from the aforementioned empirical analyses for α is 27.8 and for β is 2.8, an estimate of the EDPVR can be accurately determined. The single beat non-invasive method of Klotz14 was similar to multi-beat invasively measured EDPVR in 31 heart failure patients40 with an overall mean root mean square error obtained by pooling data from all patients was 2.79±0.21 mmHg.40 Table II lists the data needed to derive complete noninvasive PV loops. See appendix for detailed calculations needed to derive V30 and V120.

TABLE II.

Noninvasive pressure volume loops: data collection.

| Blood pressure | |

| Systolic blood pressure (brachial) | Sphygmomanometer |

| Diastolic blood pressure (brachial) | Sphygmomanometer |

| Left ventricular end diastolic pressure | |

| Mitral E wave velocity | Doppler echocardiography |

| Tissue Doppler mitral E’ velocity | Tissue Doppler |

| Volumes | |

| Left ventricular end diastolic volume | 2 or 3D echocardiography |

| Left ventricular end systolic volume | 3 or 3D echocardiography |

| Times | |

| Ejection time | Doppler echocardiography |

| Isovolumic contraction time | Doppler echocardiography |

| Isovolumic relaxation time | Doppler echocardiography |

Recent clinical applications of non-invasive PV analysis

Non-invasive PV loop analysis has been used to enhance our understanding of the mechanisms that underlie physical exam findings associated with the fourth heart sound. It has been applied to large populations to identify different pathophysiologic mechanisms that underlie heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Serial non-invasive PV loop assessment has been used to understand the mechanisms that underlie the response to carvedilol in heart failure patients and to improve our understanding of the progressive nature of cardiac amyloidosis. Additionally, non-invasive PV loop analysis promises to enhance our understanding of low flow aortic stenosis in the setting of preserved ejection fraction.

The relationship between physical exam findings and PV relations

The fourth heart sound (S4) is associated with conditions that cause LV hypertrophy and diastolic stiffness such as aortic stenosis, LVH, and ischemia.47 With the use of a non-invasive estimates of the EDPVR, the association of S4 with decreased ventricular compliance was recently demonstrated. Shah et al.48 performed phonocardiography, Doppler echocardiography, cardiac catheterization, and non-invasive single beat EDPVR derivation on 90 patients presenting for cardiac catheterization. They found that in patients with detectable S4 on phonocardiogram, end diastolic volume index was increased (76 vs 54 mL) and LVEDP was increased (18.5 vs 13.3 mmHg). Furthermore, the group averaged volume normalized EDPVR was leftward shifted in the patients with S4. This is reflected in the difference in the calculated EDV at idealized EPD of 20 mmHg: 63 mL in S4 group and 68 ml in the group without S4.48

Heart failure in the setting of normal or preserved ejection

HFPEF has been the subject of increasing attention over the last decade in part because it now accounts for more than half of the cases of heart failure.49 While traditionally attributed to “diastolic dysfunction”,50 manifesting as an upward/leftward shift of the end diastolic PV relationship,50 not all subjects with HFPEF have been demonstrated to have diastolic dysfunction. Rather, HFPEF patients display a diversity of underlying clinical pathologies and HFPEF is associated with multiple comorbid conditions51 suggesting that a single pathophysiologic explanation does not adequately account for HFPEF phenotype. Analyses of invasive PV data collected on a small cohort of subjects with HFPEF suggested marked heterogeneity in the position of the EDPVR in these subjects. Such heterogeneity in the position of the EDPVR found with invasive measures was confirmed with non-invasive measures17 applied to 357 Chinese subjects. They found that compared to those without heart failure, all heart failure patients (including HFPEF) exhibited on average a rightward shifted EDVPR. The degree of rightward shift in the EDVPR was associated with concomitant co-morbid conditions including renal dysfunction, anemia, obesity and concomitant coronary heart disease. Not unexpectedly, within the heart failure subjects as EF decreased, diastolic capacitance increased (Figure 5, reproduced with permission). This finding contrasts with the finding of Lam et al.19 They compared group averaged EDPVR derived in 224 HFPEF patients to the group averaged EDPVR in 719 patients with hypertension without heart failure and 617 patients without cardiovascular disease in Olmsted County and found that the EDPVR in the HFPEF group was upward and leftward shifted compared to both the normal and hypertensive group.19 These conflicting findings can be explained by differences in systolic blood pressure between the HFPEF group and the control group. The HFPEF patients in Chinese cohort had higher systolic blood pressure than the control group. This is contrast to the HFPEF patients in Olmstead County whose blood pressure was lower than the hypertensive controls. Indeed, when HFPEF subjects are stratified by the presence of hypertension,16 the group averaged EDVPRs in patients with HFPEF and who were non-hypertensive were consistent with an upward and leftward shift (normal end diastolic volume but elevated end diastolic pressure), however, hypertensive HFPEF patients had increased end systolic and end diastolic volumes, with an EDPVR shifted rightward, suggesting that increased circulating volume, not decreased capacitance as the primary mechanism of heart failure. Accordingly, stratifying HFPEF subjects by blood pressure can facilitate the identification of different physiologic phenotypes.

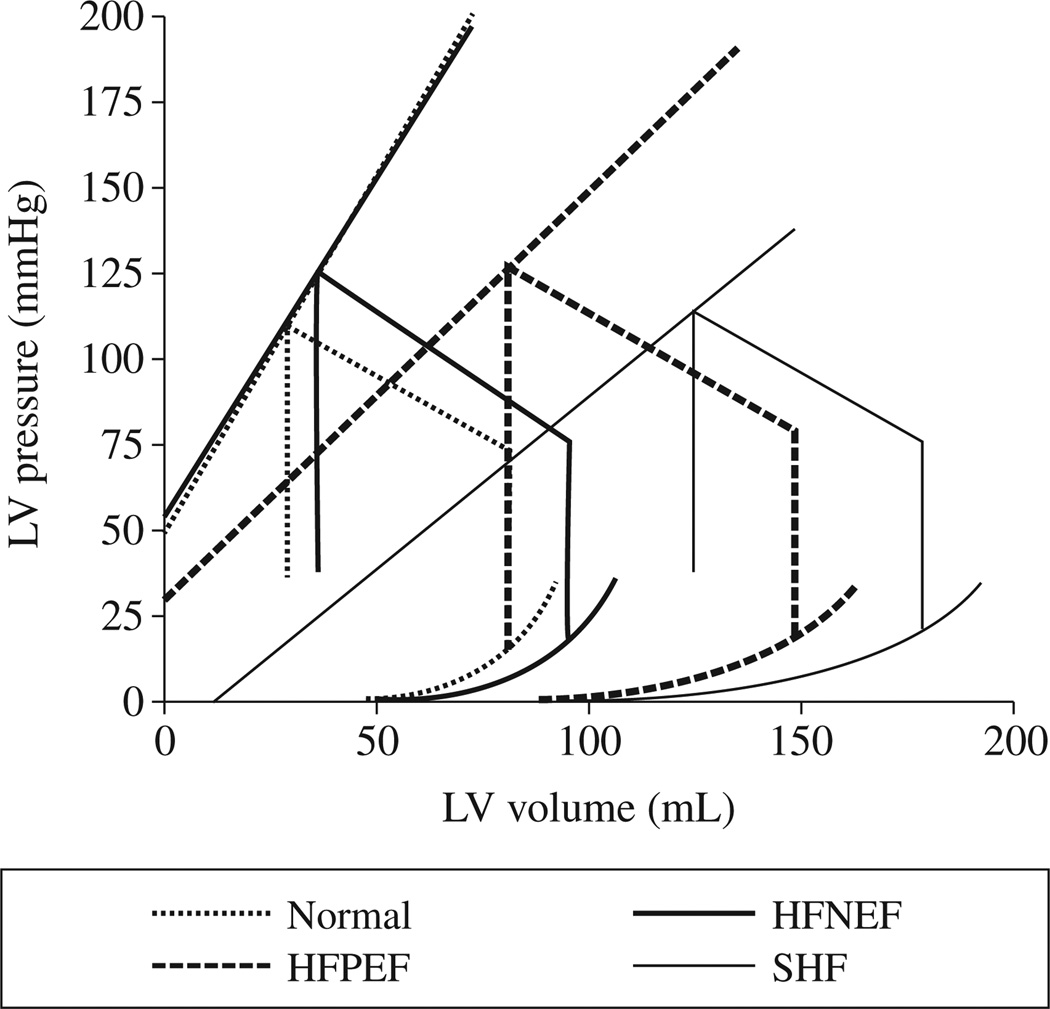

Figure 5.

Non-invasively estimated average pressure-volume relations including end-systolic and end diastolic pressure-volume relations in patients with normal (HFNEF), mildly reduced (HFPEF) and moderate and severe reduction (SHF) in EF compared to normal controls. Note the increased end diastolic volume despite similar end systolic elastance in the HFNEF compared to normal.

Disease progression and response to pharmacologic intervention

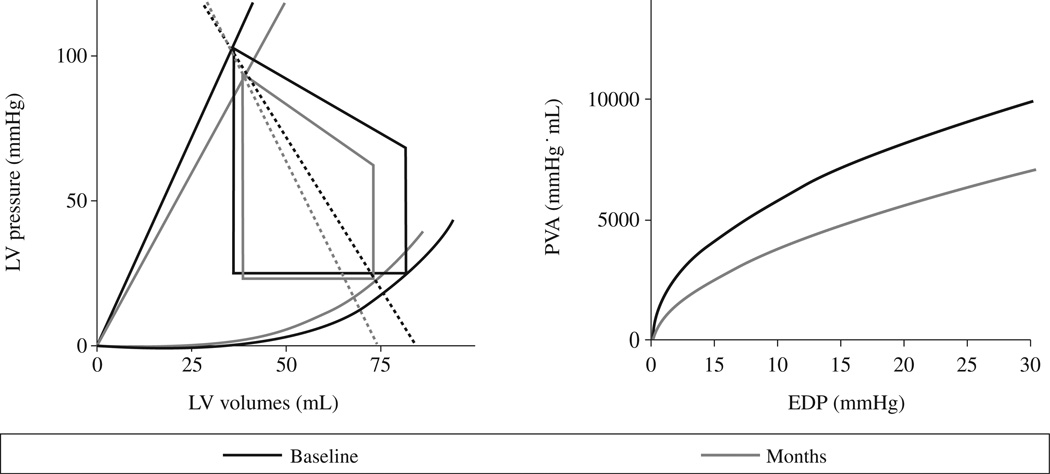

Bhuiyan et al.34 employed noninvasive PV loop analysis to explore the mechanisms underlying the progressive decline in cardiac function and the high mortality associated with transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis, both mutant and wild type. As part of the TRACS (Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiac Study), 29 patients from 5 centers who had serial echocardiographic measures including ventricular volume and full Doppler analysis including mitral inflow and tissue Doppler every 6 month for up to 2 years. Using these data, group-averaged PV loops were constructed and demonstrated that over an 18 month follow-up period the ability of the ventricle to perform work declined. Specifically, the PVAiso-EDP relationship demonstrated progressive declines over time which was attributable to decrements in chamber contractility (Ees) and ventricular capacitance along with increases in arterial elastance. Additionally, the decline in ventricular performance in this population was strongly associated with mortality. Such applications could be employed in other rare cardiac disorders to elucidate the mechanisms underlying disease progression.

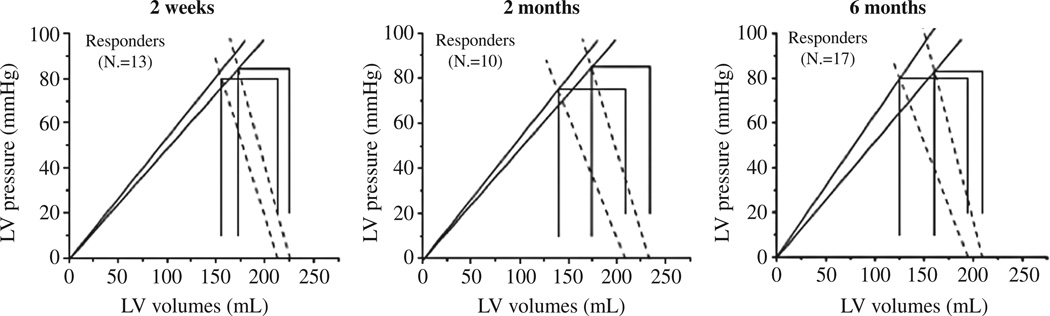

Beta adrenergic antagonists are a mainstay of therapy for patients with systolic heart failure across the spectrum of disease.52, 53 Meta-analysis of large clinical trials suggest that beta blockers increased the ejection fraction by an average of 6–8% units54 and that the mortality benefit is directly attributable to reductions in heart rate.55 Using non-invasive PV loop analysis performed serially in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction, the mechanisms underlying the improvement in ejection fraction with carvediolol were studied. At baseline and 2 weeks, 2, 6, and 12 months after the initiation of carvedilol group averaged PV loops were compared between responders (those whose EF increased by 5%)56 and nonresponders to carvedilol therapy. Responders demonstrated a significant decreases in arterial elastance (mediated mainly by reductions in heart rate) as well as increases in chamber contractility with a resulting improvement in the Ees/Ea ratio (Figure 7). Multiple linear regression showed that 56% of the EF increase was mediated by a reduction in HR, rather than a reduction in total peripheral resistance, which had been previously suggested as a major benefit of carvediolol over other beta adrenergic antagonists.54 These findings were further validated by the studies showing benefits of heart rate reduction with ivabradine, an inhibitor of the If current in the sinoatrial node, which selectively reduces heart rate without modifying myocardial contractility and intracardiac conduction.57. In animal studies treatment with ivabradine results in improvement of ejection fraction58, 59 and in the recent SHIFT trial heart failure patients randomized to ivabradine experienced a reduction in death and hospitalization60

Figure 7.

Groups mean PV-loops in responders to carvedilol. The blue line shows baseline values and in red are paired follow-up values. ESPVRs were estimated by the end systolic PV ratio (Res) represented by solid lines and arterial elastance (Ea) by the dotted lines. From Circ Heart Fail 2009;2:189-96.18 Reprinted with permission from authors.

Valvular heart disease

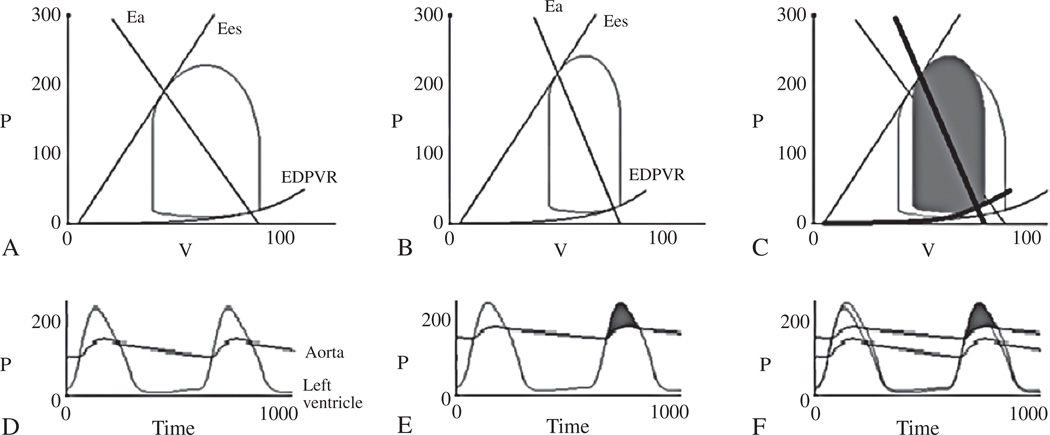

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common valvular pathology, disproportionately effecting older adults61 and resulting often in a remodeled ventricle with diastolic dysfunction. Diagnosing severe AS can be challenging. According to practice guidelines the diagnosis of severe AS depends on echocardiographically derived gradient, velocity or aortic valve area.62 In practice, valve area calculation can be limited by inaccurate LVOT measurements. Furthermore, as many as 22% of patients with severe AS, do not meet velocity or gradient based estimates of AS severity.63 The phenotype of aortic stenosis associated with low transvalvular gradients in the context of reduced ejection fraction has been recognized for decades and is beyond the scope of this review.64, 65 More recently the phenotype of aortic stenosis with low flow despite normal ejection fraction has come to light, leading some to apply the terminology: paradoxical low flow (PLF) low gradient AS. PLF AS patients have aortic valve area index ≤0.6 cm2 with LVEF≥50% and a stroke volume index of ≥35 mL/m2.66 In one series, among patient with AS and normal EF, 35% had PLF. Two separate studies found that 55%66 and 56%67 of patients with PLF has transvalvular gradients of 30 mmHg or less. This reduced gradient is thought to be due to poor ventricular function in the setting of severe diastolic dysfunction66 or markedly increased afterload68 due to longstanding hypertension and diffuse atherosclerosis of the aorta and conduit vesels. Using PV loops one can easily identify and understand the underlying mechanisms contributing to low gradient PLF physiology. Figure 8 shows example PV loops generated using The Heart Simulator modeling program <http://www.columbia.edu/itc/hs/medical/heartsim/>. PV loops and corresponding timeplots of LV and aortic pressure for normal flow (panels A and D) and PLF AS (B and E) are shown. The combination of increased afterload and reduced stroke volume result in a lower gradient across the stenotic aortic valve despite the same valve area. Note the leftward shifted EDPVR, higher systolic blood pressure, increased Ea, and lower stroke volume in the PLF example compared to the normal flow example (panels C and F).

Figure 8.

PV loop and corresponding timeplots of LV and aortic pressure for normal flow (A, D), paradoxical low flow AS (B, E) and the two superimposed (C,F). The combination of increased afterload and reduced stroke volume result in a lower gradient across the stenotic aortic valve despite the same valve area (mean gradient 38 vs 50 mmHg in the paradoxical low flow example compared to normal flow AS). Note the leftward shifted EDPVR, higher systolic blood pressure (182 vs 150 mmHg), increased Ea, and lower stroke volume (34 vs 51 ml) in the paradoxical low flow compared to normal flow example (C, F).

The distinct pathophysiology and the lower gradients associated with PLF AS often confound the diagnosis of severe AS and as such surgery is often deferred.66 This, despite the poor prognosis associated with PLF AS compared to normal flow.66, 67 To overcome the limitations of relying on gradient or aortic valve area, investigators have developed a sensitive index of overall afterload. Valvuloarterial impedance (ZVA) is calculated echocardiographically by dividing the sum of the systolic blood pressure and mean gradient (a measure of the left ventricular systolic pressure) by the left ventricular stroke volume index. Similar to the concept of arterial elastance, ZVA estimates the impact of the overall afterload imposed by the aortic valve and arterial system. ZVA is emerging as a sensitive index of AS severity with high ZVA portending a poor prognosis in patients with AS.69 While valuable as a prognostic index, ZVA does not distinguish between the potential theoretical subtypes of patients with PLF. It can be inferred from the formula that either an abnormally high systolic blood pressure or abnormally low stroke volume can cause ZVA to be elevated. Whether patients with high ZVA secondary to high blood pressure differ in response to amelioration of AS with TAVI as compared to those with low stroke volume is a focus of ongoing study. While Hachicha notes that both decreased stroke volume and increased arterial stiffness are associated with increased mortality after aortic valve replacement in PLF AS,66 the impact of these indices on functional recovery after TAVI is not yet defined. PV loop assessment can identify the relative contributions of afterload and diastolic dysfunction to PLF AS. Furthermore, serial noninvasive PV assessment in PLF AS patients can quantify the time-course and magnitude of remodeling after AVR.70, 71

Conclusions

Echocardiographically derived non-invasive PV loop analysis facilitates the application of classic hemodynamic principles to large samples of patients and can be applied serially, enhancing our understanding of the pathophysiology of disease, the mechanism underlying response to therapy and disease progression, and the development of prognostic markers. Future studies using such techniques will provide additional insights into the complex physiologic issues that clinicians and their patients face each day.

Figure 6.

PV relations (panel A) and iso-volumetric pressure-volume area (PVA-iso, panel B) baseline to 18-month follow-up There were significant (e.g. P<0.05) increases in Ea, declines in Res, altered Ea/Res ratio, and significant difference in PVA-iso curve from baseline to 18 months. Published online December 29, 2010. From Circ Heart Fail 2009;2:189-96.18 Reprinted with permission from authors.

Acknowledgments

Funding.—Dr. Maurer is supported a grant from the National Institute of Health/National Institute on Aging, K24AG036778 – 01A1

APPENDIX

ESPVR

Deriving the single beat ESPVR depends on estimating the slope (Ees) and the volume intercept (V0). We employ the method of Chen(15). Ees is obtained first as it is employed to estimate V0.

Estimating Ees depends on calculating time-normalized elastance:

Where tnd is normalized isovolumic contraction, and IVCT is isovolumic contraction time and ET is ejection time.

Endest is elastance at time normalized end of isovolumic contraction. It relies on calculating a time normalized mid systolic elastance (End) using the quadratic equation. EF is ejection fraction. SBP and DBP are systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

Where Ees is single beat end systolic elastance. SV is stroke volume.

After obtaining as Ees[sb], we can estimate V0.

Kelly showed that end systolic pressure is 90% of systolic blood pressure(72).

Where V0 is time the volume intercept of the ESPVR and ESV is end systolic volume.

Where V120 is the ventricular volume corresponding to a systolic pressure of 120 mmHg.

EDPVR

We employ the method of Klotz to derive a single beat estimate of the EDPVR(14).

Where EDP is end diastolic pressure and E is mitral E wave velocity and E’ is tissue Doppler septal E wave velocity(73).

Where V30 is the ventricular volume corresponding to a diastolic pressure of 30 mmHg, and Vtemp is as calculated above, where EDV is end diastolic volume.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest.—None declared.

References

- 1.Frank O. Zur Dynamik des Herzmuskels. Z Biol. 1895;32:370–447. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sunagawa K, Yamada A, Senda Y, Kikuchi Y, Nakamura M, Shibahara T, et al. Estimation of the hydromotive source pressure from ejecting beats of the left ventricle. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1980;27:299–305. doi: 10.1109/TBME.1980.326737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guyton AC, Armstrong GG, Chipley PL. Pressure-volume curves of the arterial and venous systems in live dogs. Am J Physiol. 1956;184:253–258. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1956.184.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burch GE, Cronvich JA, Creech O, Hyman A. Pressure-volume diagrams of the left ventricle of man; a preliminary report. Am Heart J. 1957;53:890–894. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(57)90325-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suga H. Time course of left ventricular pressure-volume relationship under various extents of aortic occlusion. Jpn Heart J. 1970;11:373–378. doi: 10.1536/ihj.11.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suga H. Time course of left ventricular pressure-volume relationship under various enddiastolic volume. Jpn Heart J. 1969;10:509–515. doi: 10.1536/ihj.10.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suga H, Sagawa K. Instantaneous pressure-volume relationships and their ratio in the excised, supported canine left ventricle. Circ Res. 1974;35:117–126. doi: 10.1161/01.res.35.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanke T, Misfeld M, Heringlake M, Schreuder JJ, Wiegand UKH, Eberhardt F. The effect of biventricular pacing on cardiac function after weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass in patients with reduced left ventricular function: A pressure-volume loop analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steendijk P, Tulner SA, Bax JJ, Oemrawsingh PV, Bleeker GB, van Erven L, et al. Hemodynamic effects of long-term cardiac resynchronization therapy: analysis by pressure-volume loops. Circulation. 2006;113:1295–1304. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.540435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penicka M, Bartunek J, Trakalova H, Hrabakova H, Maruskova M, Karasek J, et al. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in outpatients with unexplained dyspnea: a pressure-volume loop analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1701–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kass DA, Baughman KL, Pak PH, Cho PW, Levin HR, Gardner TJ, et al. Reverse remodeling from cardiomyoplasty in human heart failure: external constraint versus active assist. Circulation. 1995;9112 doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.9.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreuder JJ, Steendijk P, van der Veen FH, Alfieri O, van der Nagel T, Lorusso R, et al. Acute and short-term effects of partial left ventriculectomy in dilated cardiomyopathy: Assessment by pressure-volume loops. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:2104–2114. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westermann D, Kasner M, Steendijk P, Spillmann F, Riad A, Weitmann K, et al. Role of left ventricular stiffness in heart failure with normal ejection fraction. Circulation. 2008;117:2051–2060. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.716886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klotz S, Hay I, Dickstein ML, Yi GH, Wang J, Maurer MS, et al. Single-beat estimation of end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship: a novel method with potential for noninvasive application. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H403–H412. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01240.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CH, Fetics B, Nevo E, Rochitte CE, Chiou KR, Ding PA, et al. Noninvasive single-beat determination of left ventricular end-systolic elastance in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:2028–2034. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01651-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maurer MS, King DL, El-Khoury Rumbarger L, Packer M, Burkhoff D. Left heart failure with a normal ejection fraction: identification of different pathophysiologic mechanisms. J Card Fail. 2005;11:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He KL, Burkhoff D, Leng WX, Liang ZR, Fan L, Wang J, et al. Comparison of ventricular structure and function in Chinese patients with heart failure and ejection fractions >55% versus 40% to 55% versus <40% Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:845–851. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maurer MS, Sackner-Bernstein JD, El-Khoury Rumbarger L, Yushak M, King DL, Burkhoff D. Mechanisms underlying improvements in ejection fraction with carvedilol in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:189–196. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.806240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lam CS, Roger VL, Rodeheffer RJ, Bursi F, Borlaug BA, Ommen SR, et al. Cardiac structure and ventricular-vascular function in persons with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Circulation. 2007;115:1982–1990. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.659763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhuiyan T, Helmke S, AR P, FL R, Packman J, Cheung K, et al. Pressure-volume relationships in patients with transthyretin (ATTR) cardiac amyloidosis secondary to v122i mutations and wild type TTR: TRACS (Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloid Study) Circ Heart Failure. 2010 doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.910455. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shishido T, Hayashi K, Shigemi K, Sato T, Sugimachi M, Sunagawa K. Single-beat estimation of end-systolic elastance using bilinearly approximated time-varying elastance curve. Circulation. 2000;102:1983–1989. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.16.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burkhoff D, Mirsky I, Suga H. Assessment of systolic and diastolic ventricular properties via pressure-volume analysis: a guide for clinical, translational, and basic researchers. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H501–H512. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00138.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen RS, Karlin P, Yushak M, Mancini D, Maurer MS. The effect of erythropoietin on exercise capacity, left ventricular remodeling, pressure-volume relationships, and quality of life in older patients with anemia and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Congestive Heart Failure. 2010;16:96–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2009.00135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sunagawa K, Maughan WL, Burkhoff D, Sagawa K. Left ventricular interaction with arterial load studied in isolated canine ventricle. Am J Physiol. 1983;245(5 Pt 1):H773–H780. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.245.5.H773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burkhoff D, Sagawa K. Ventricular efficiency predicted by an analytical model. Am J Physiol. 1986;250(6 Pt 2):R1021–R1027. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.250.6.R1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sunagawa K, Maughan WL, Sagawa K. Optimal arterial resistance for the maximal stroke work studied in isolated canine left ventricle. Circ Res. 1985;56:586–595. doi: 10.1161/01.res.56.4.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zile M, Izzi G, Gaasch W. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction limits use of maximum systolic elastance as an index of contractile function. Circulation. 1991;83:674–680. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.2.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suga H. Total mechanical energy of a ventricle model and cardiac oxygen consumption. Am J Physiol. 1979;236:H498–H505. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.236.3.H498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khalafbeigui F, Suga H, Sagawa K. Left ventricular systolic pressure-volume area correlates with oxygen consumption. Am J Physiol. 1979;237:H566–H569. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.237.5.H566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suga H, Hayashi T, Shirahata M. Ventricular systolic pressure-volume area as predictor of cardiac oxygen consumption. Am J Physiol. 1981;240:H39–H44. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1981.240.1.H39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suga H, Igarashi Y, Yamada O, Goto Y. Mechanical efficiency of the left ventricle as a function of preload, afterload, and contractility. Heart and Vessels. 1985;1:3–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02066480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suga H, Goto Y, Futaki S, Kawaguchi O, Yaku H, Hata K, et al. Systolic pressure-volume area (PVA) as the energy of contraction in Starling’s law of the heart. Heart Vessels. 1991;6:65–70. doi: 10.1007/BF02058751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Izzi G, Zile MR, Gaasch WH. Myocardial oxygen consumption and the left ventricular pressure-volume area in normal and hypertrophic canine hearts. Circulation. 1991;84:1384–1392. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.3.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhuiyan T, Helmke S, Patel AR, Ruberg FL, Packman J, Cheung K, et al. Pressure-Volume Relationships in Patients with Transthyretin (ATTR) Cardiac Amyloidosis Secondary to V122I Mutations and Wild Type TTR: TRACS (Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloid Study) Circulation: Heart Failure. 2010 doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.910455. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baan J, Jong TT, Kerkhof PL, Moene RJ, van Dijk AD, van der Velde ET, et al. Continuous stroke volume and cardiac output from intra-ventricular dimensions obtained with impedance catheter. Cardiovasc Res. 1981;15:328–334. doi: 10.1093/cvr/15.6.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burkhoff D, van der Velde E, Kass D, Baan J, Maughan WL, Sagawa K. Accuracy of volume measurement by conductance catheter in isolated, ejecting canine hearts. Circulation. 1985;72:440–447. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.72.2.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kass DA, Yamazaki T, Burkhoff D, Maughan WL, Sagawa K. Determination of left ventricular end-systolic pressure-volume relationships by the conductance (volume) catheter technique. Circulation. 1986;73:586–595. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.73.3.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kass DA, Midei M, Graves W, Brinker JA, Maughan WL. Use of a conductance (volume) catheter and transient inferior vena caval occlusion for rapid determination of pressure-volume relationships in man. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1988;15:192–202. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810150314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baan J, van der Velde E, de Bruin H, Smeenk G, Koops J, van Dijk A, et al. Continuous measurement of left ventricular volume in animals and humans by conductance catheter. Circulation. 1984;70:812–823. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.70.5.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ten Brinke EA, Burkhoff D, Klautz RJ, Tschope C, Schalij MJ, Bax JJ, et al. Single-beat estimation of the left ventricular end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship in patients with heart failure. Heart. 2010;96:213–219. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.176248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takeuchi M, Igarashi Y, Tomimoto S, Odake M, Hayashi T, Tsukamoto T, et al. Single-beat estimation of the slope of the end-systolic pressure-volume relation in the human left ventricle. Circulation. 1991;83:202–212. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.1.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Senzaki H, Chen CH, Kass DA. Single-beat estimation of end-systolic pressure-volume relation in humans. A new method with the potential for noninvasive application. Circulation. 1996;94:2497–2506. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.10.2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee WS, Nakayama M, Huang WP, Chiou KR, Wu CC, Nevo E, et al. Assessment of left ventricular endsystolic elastance from aortic pressure-left ventricular volume relations. Heart Vessels. 2002;16:99–104. doi: 10.1007/s003800200003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mulvagh S, Quinones MA, Kleiman NS, Cheirif J, Zoghbi WA. Estimation of left ventricular end-diastolic pressure from Doppler transmitral flow velocity in cardiac patients independent of systolic performance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:112–119. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90146-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vanoverschelde JL, Robert AR, Gerbaux A, Michel X, Hanet C, Wijns W. Noninvasive estimation of pulmonary arterial wedge pressure with Doppler transmitral flow velocity pattern in patients with known heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:383–389. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80559-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hillis GS, Moller JE, Pellikka PA, Gersh BJ, Wright RS, Ommen SR, et al. Noninvasive estimation of left ventricular filling pressure by E/e’ is a powerful predictor of survival after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stefadouros MA, Little RC. The cause and clinical significance of diastolic heart sounds. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140:537–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shah SJ, Nakamura K, Marcus GM, Gerber IL, McKeown BH, Jordan MV, et al. Association of the Fourth Heart Sound With Increased Left Ventricular End-Diastolic Stiffness. J Cardiac Failure. 2008;14:431–436. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sweitzer NK, Lopatin M, Yancy CW, Mills RM, Stevenson LW. Comparison of clinical features and outcomes of patients hospitalized with heart failure and normal ejection fraction (>=55%) versus those with mildly reduced (40% to 55%) and moderately to severely reduced (<40%) fractions. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1151–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zile MR, Baicu CF, Gaasch WH. Diastolic heart failure — abnormalities in active relaxation and passive stiffness of the left ventricle. New Engl J Med. 2004;350:1953–1959. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klapholz M, Maurer M, Lowe AM, Messineo F, Meisner JS, Mitchell J, et al. Hospitalization for heart failure in the presence of a normal left ventricular ejection fraction: Results of the New York heart failure registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1432–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Packer M, Bristow MR, Cohn JN, Colucci WS, Fowler MB, Gilbert EM, et al. The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. New Engl J Med. 1996;334:1349–1355. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605233342101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in-Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF) Lancet. 1999;353:2001–2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Packer M, Antonopoulos GV, Berlin JA, Chittams J, Konstam MA, Udelson JE. Comparative effects of carvedilol and metoprolol on left ventricular ejection fraction in heart failure: results of a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2001;141:899–907. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.115584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Flannery G, Gehrig-Mills R, Billah B, Krum H. Analysis of randomized controlled trials on the effect of magnitude of heart rate reduction on clinical outcomes in patients with systolic chronic heart failure receiving beta-blockers. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:865–869. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Green P, Anshelevich M, Talreja A, Burcham JL, Ravi SM, Shirani J, et al. Long-term effects of carvedilol or metoprolol on left ventricular function in ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:1114–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Savelieva I, Camm AJ. If inhibition with ivabradine: electrophysiological effects and safety. Drug Saf. 2008;31:95–107. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200831020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mulder P, Barbier S, Chagraoui A, Richard V, Henry JP, Lallemand F, et al. Long-term heart rate reduction induced by the selective if current inhibitor ivabradine improves left ventricular function and intrinsic myocardial structure in congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2004;109:1674–1679. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118464.48959.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Couvreur N, Tissier R, Pons S, Chetboul V, Gouni V, Bruneval P, et al. Chronic heart rate reduction with ivabradine improves systolic function of the reperfused heart through a dual mechanism involving a direct mechanical effect and a long-term increase in FKBP12/12.6 expression. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1529–1537. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Swedberg K, Komajda M, Böhm M, Borer JS, Ford I, Dubost-Brama A, et al. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet. 2010;376:875–885. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stewart MDFBF, Siscovick MDMPHD, Lind MSBK, Gardin MDFJM, Gottdiener MDFJS, Smith MDVE, et al. Clinical factors associated with calcific aortic valve disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:630–634. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00563-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, de Leon AC, Jr, Faxon DP, Freed MD, et al. 2008 Focused Update Incorporated Into the ACC/AHA 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease) Endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:e1–e142. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barasch E, Fan D, Chukwu EO, Han J, Passick M, Petillo F, et al. Severe isolated aortic stenosis with normal left ventricular systolic function and low transvalvular gradients: pathophysiologic and prognostic insights. J Heart Valve Dis. 2008;17:81–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carabello B, Green L, Grossman W, Cohn L, Koster J, Collins J., Jr Hemodynamic determinants of prognosis of aortic valve replacement in critical aortic stenosis and advanced congestive heart failure. Circulation. 1980;62:42–48. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.62.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tribouilloy C, Lévy F. Assessment and management of low-gradient, low ejection fraction aortic stenosis. Heart. 2008;94:1526–1527. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.142745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hachicha Z, Dumesnil JG, Bogaty P, Pibarot P. Paradoxical low-flow, low-gradient severe aortic stenosis despite preserved ejection fraction is associated with higher afterload and reduced survival. Circulation. 2007;115:2856–2864. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.668681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cramariuc D, Cioffi G, Rieck AE, Devereux RB, Staal EM, Ray S, et al. Low-Flow Aortic Stenosis in Asymptomatic Patients: Valvular-Arterial Impedance and Systolic Function From the SEAS Substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2009;2:390–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Briand M, Dumesnil JG, Kadem L, Tongue AG, Rieu R, Garcia D, et al. Reduced systemic arterial compliance impacts significantly on left ventricular afterload and function in aortic stenosis: implications for diagnosis and treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hachicha Z, Dumesnil JG, Pibarot P. Usefulness of the valvuloarterial impedance to predict adverse outcome in asymptomatic aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1003–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Villari B, Vassalli G, Monrad ES, Chiariello M, Turina M, Hess OM. Normalization of diastolic dysfunction in aortic stenosis late after valve replacement. Circulation. 1995;91:2353–2358. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.9.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Krayenbuehl H, Hess O, Monrad E, Schneider J, Mall G, Turina M. Left ventricular myocardial structure in aortic valve disease before, intermediate, and late after aortic valve replacement. Circulation. 1989;79:744–755. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.4.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kelly RP, Ting CT, Yang TM, Liu CP, Maughan WL, Chang MS, et al. Effective arterial elastance as index of arterial vascular load in humans. Circulation. 1992;86:513–521. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ommen SR, Nishimura RA, Appleton CP, Miller FA, Oh JK, Redfield MM, et al. Clinical utility of doppler echocardiography and tissue doppler imaging in the estimation of left ventricular filling pressures: a comparative simultaneous doppler-catheterization study. Circulation. 2000;102:1788–1794. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.15.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]