1. INTRODUCTION

These 2015 clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for developing a diabetes mellitus (DM) comprehensive care plan are an update of the 2011 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for Developing a Diabetes Mellitus Comprehensive Care Plan (1 [EL 4; NE]). The mandate for this CPG is to provide a practical guide for comprehensive care that incorporates an integrated consideration of micro- and macrovascular risk (including cardiovascular risk factors such as lipids, hypertension, and coagulation) rather than an isolated approach focusing merely on glycemic control. In addition to topics covered in the 2011 CPG, this update offers new and expanded information on vaccinations; cancer risk; and management of obesity, sleep disorders, and depression among persons with DM, as well as medical management of commercial vehicle operators and others with occupations that put them at increased risks of obesity and DM or in which hypoglycemia might endanger other individuals. In addition, discussions of hypertension management, nephropathy management, hypoglycemia, and antihyperglycemic therapy have been substantially revised and updated. The 2015 treatment goals emphasize individualized targets for weight loss, glucose, lipid, and hypertension management. In addition, the 2015 Guidelines promote personalized management plans with a special focus on safety beyond efficacy.

When a routine consultation is made for DM management, these new guidelines advocate taking a comprehensive approach and suggest that the clinician should move beyond a simple focus on glycemic control. This comprehensive approach is based on the evidence that although glycemic control parameters (hemoglobin A1c [A1C], postprandial glucose [PPG] excursions, fasting plasma glucose [FPG], glycemic variability) have an impact on the risk of microvascular complications and cardiovascular disease (CVD), mortality, and quality of life, other factors also affect clinical outcomes in persons with DM.

The objectives of this CPG are to provide the following:

An education resource for the development of a comprehensive care plan for clinical endocrinologists and other clinicians who care for patients with DM.

An evidence-based resource addressing specific problems in DM care.

A document that can eventually be electronically implemented in clinical practices to assist with decision-making for patients with DM.

To achieve these goals, this CPG includes an executive summary consisting of 67 clinical practice recommendations organized within 24 questions covering the spectrum of DM management. The recommendations provide brief, accurate answers to each question, and an extensively referenced appendix organized according to the same list of questions provides supporting evidence for each recommendation. The format is concise and does not attempt to present an encyclopedic citation of all pertinent primary references, which would create redundancy and overlap with other published CPGs and evidence-based reports related to DM. Therefore, although many highest evidence level (EL) studies—consisting of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses of these trials (EL 1)—are cited in this CPG, in the interest of conciseness, there is also a deliberate, preferential, and frequent citation of derivative EL 4 publications that include many primary evidence citations (EL 1, EL 2, and EL 3). Thus, this CPG is not intended to serve as a DM textbook but rather to complement existing texts as well as other DM CPGs available in the literature including previously published AACE DM CPGs.

2. METHODS

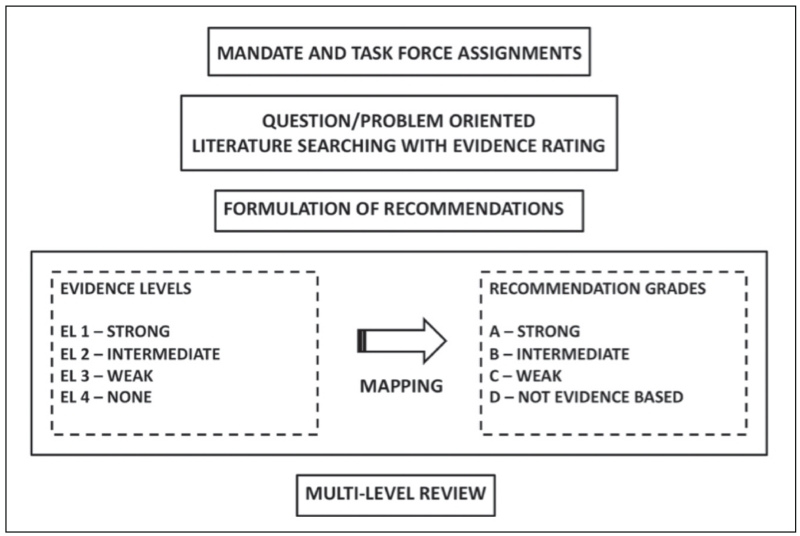

The AACE Board of Directors mandated an update of the 2011 AACE DM CPG (1 [EL 4; NE]), which expired in 2014. Selection of the cochairs, primary writers, and reviewers, as well as the logistics for creating this evidence-based CPG were conducted in strict adherence with the AACE Protocol for Standardized Production of Clinical Practice Guidelines—2010 and 2014 Updates (2 [EL 4; CPG NE; see Fig. 1; Tables 1-4]; 3 [EL 4; CPG NE; see Tables 1-4]).

Fig. 1.

2010 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) methodology. Current AACE CPGs have a problem-oriented focus that results in a shortened production time line, middle-range literature searching, emphasis on patient-oriented evidence that matters, greater transparency of intuitive evidence rating and qualifications, incorporation of subjective factors into evidence-recommendation mapping, cascades of alternative approaches, and an expedited multilevel review mechanism.

Table 1. 2010 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Protocol for Production of Clinical Practice Guidelines—Step I: Evidence Ratinga.

| Numerical descriptor (evidence level)b |

Semantic descriptor (reference methodology) |

|---|---|

| 1 | Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (MRCT) |

| 1 | Randomized controlled trials (RCT) |

| 2 | Meta-analysis of nonrandomized prospective or case-controlled trials (MNRCT) |

| 2 | Nonrandomized controlled trial (NRCT) |

| 2 | Prospective cohort study (PCS) |

| 2 | Retrospective case-control study (RCCS) |

| 3 | Cross-sectional study (CSS) |

| 3 | Surveillance study (registries, surveys, epidemiologic study, retrospective chart review, mathematical modeling of database) (SS) |

| 3 | Consecutive case series (CCS) |

| 3 | Single case reports (SCR) |

| 4 | No evidence (theory, opinion, consensus, review, or preclinical study) (NE) |

Adapted from (1): Endocr Pract. 2010;16:270-283.

1, strong evidence; 2, intermediate evidence; 3, weak evidence; and 4, no evidence.

Table 4. 2010 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Protocol for Production of Clinical Practice Guidelines—Step IV: Examples of Qualifiersa.

| Cost-effectiveness |

| Risk-benefit analysis |

| Evidence gaps |

| Alternative physician preferences (dissenting opinions) |

| Alternative recommendations (“cascades”) |

| Resource availability |

| Cultural factors |

| Relevance (patient-oriented evidence that matters) |

Reprinted from (1): Endocr Pract. 2010;16:270-283.

All primary writers are AACE members and credentialed experts in the field of DM care. This CPG has been reviewed and approved by the primary writers, other invited experts, the AACE Publications Committee, and the AACE Board of Directors before submission for peer review by Endocrine Practice. All primary writers made disclosures regarding multiplicities of interests and attested that they are not employed by industry.

Reference citations in the text of this document include the reference number, numerical descriptor (e.g., EL 1, 2, 3, or 4), and semantic descriptor (Table 1). Recommendations are based on the quality of supporting evidence (Table 2), all of which have also been rated (Table 3). This CPG is organized into specific and relevant clinical questions labeled “Q.”

Table 2. 2010 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Protocol for Production of Clinical Practice Guidelines—Step II: Evidence Analysis and Subjective Factorsa.

| Study design | Data analysis | Interpretation of results |

|---|---|---|

| Premise correctness | Intent-to-treat | Generalizability |

| Allocation concealment (randomization) | Appropriate statistics | Logical |

| Selection bias | Incompleteness | |

| Appropriate blinding | Validity | |

| Using surrogate end points (especially in “first-in-its-class” intervention) |

||

| Sample size (beta error) | ||

| Null hypothesis vs. Bayesian statistics |

Reprinted from (1): Endocr Pract. 2010;16:270-283.

Table 3. 2010 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Protocol for Production of Clinical Practice Guidelines—Step III: Grading of Recommendations; How Different Evidence Levels can be Mapped to the Same Recommendation Gradea,b.

| Best evidence level |

Subjective factor impact |

Two-thirds consensus |

Mapping | Recommendation grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | Yes | Direct | A |

| 2 | Positive | Yes | Adjust up | A |

| 2 | None | Yes | Direct | B |

| 1 | Negative | Yes | Adjust down | B |

| 3 | Positive | Yes | Adjust up | B |

| 3 | None | Yes | Direct | C |

| 2 | Negative | Yes | Adjust down | C |

| 4 | Positive | Yes | Adjust up | C |

| 4 | None | Yes | Direct | D |

| 3 | Negative | Yes | Adjust down | D |

| 1, 2, 3, 4 | NA | No | Adjust down | D |

Starting with the left column, best evidence levels (BELs), subjective factors, and consensus map to recommendation grades in the right column. When subjective factors have little or no impact (“none”), then the BEL is directly mapped to recommendation grades. When subjective factors have a strong impact, then recommendation grades may be adjusted up (“positive” impact) or down (“negative” impact). If a two-thirds consensus cannot be reached, then the recommendation grade is D. NA, not applicable (regardless of the presence or absence of strong subjective factors, the absence of a two-thirds consensus mandates a recommendation grade D).

Reprinted from (1): Endocr Pract. 2010;16:270-283.

Recommendations (numerically labeled “R1, R2, etc.”) are based on importance and evidence (Grades A, B, and C) or expert opinion when there is a lack of conclusive clinical evidence (Grade D). The best EL (BEL), which corresponds to the best conclusive evidence found in the Appendix to follow, accompanies the recommendation grade in this Executive Summary; definitions of evidence levels are provided in Figure 1 and Table 1 (2 [EL 4; CPG NE; see Fig. 1; Table 1-4]). Comments may be appended to the recommendation grade and BEL regarding any relevant subjective factors that may have influenced the grading process (Table 4). Details regarding each recommendation may be found in the corresponding section of the Appendix. Thus, the process leading to a final recommendation and grade is not rigid; rather, it incorporates a complex expert integration of objective and subjective factors meant to reflect optimal real-life clinical decision-making and enhance patient care. Where appropriate, multiple recommendations are provided so that the reader has management options. This document is only intended to serve as a guideline. Individual patient circumstances and presentations differ, and the ultimate clinical management is based on what is in the best interest of the individual patient, involving patient input and reasonable clinical judgment by the treating clinicians.

3. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

To guide readers, DM comprehensive management recommendations are organized into the following questions:

Q1. How is diabetes screened and diagnosed?

Q2. How is prediabetes managed?

Q3. What are the glycemic treatment goals of DM?

Q4. How are glycemic targets achieved for type 2 diabetes (T2D)?

Q5. How should glycemia in type 1 diabetes (T1D) be managed?

Q6. How is hypoglycemia managed?

Q7. How is hypertension managed in patients with diabetes?

Q8. How is dyslipidemia managed in patients with diabetes?

Q9. How is nephropathy managed in patients with diabetes?

Q10. How is retinopathy managed in patients with diabetes?

Q11. How is neuropathy diagnosed and managed in patients with diabetes?

Q12. How is CVD managed in patients with diabetes?

Q13. How is obesity managed in patients with diabetes?

Q14. What is the role of sleep medicine in the care of the patient with diabetes?

Q15. How is diabetes managed in the hospital?

Q16. How is a comprehensive diabetes care plan established in children and adolescents?

Q17. How should diabetes in pregnancy be managed?

Q18. When and how should glucose monitoring be used?

Q19. When and how should insulin pump therapy be used?

Q20. What is the imperative for education and team approach in DM management?

Q21. Which vaccinations should be given to patients with diabetes?

Q22. How should depression be managed in the context of diabetes?

Q23. What is the association between diabetes and cancer?

Q24. Which occupations have specific diabetes management requirements?

Readers are referred to the Appendix (section 4) for more detail and supporting evidence for each question.

3.Q1. How is Diabetes Screened and Diagnosed?

R1. There is a continuum of risk for poor health outcomes in the progression from normal glucose tolerance to overt T2D. Screening should be considered in the presence of risk factors for DM (Table 5) (Grade C; BEL 3). Individuals at risk for DM whose glucose values are in the normal range should be screened every 3 years; clinicians may consider annual screening for patients with 2 or more risk factors (Grade C; BEL 3).

- R2. The following criteria may be used to diagnose DM (Table 6) (Grade B; BEL 3):

- FPG concentration (after 8 or more hours of no caloric intake) ≥126 mg/dL, or

- Plasma glucose concentration ≥200 mg/dL 2 hours after ingesting a 75-g oral glucose load in the morning after an overnight fast of at least 8 hours, or

- Symptoms of hyperglycemia (e.g., polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia) and a random (casual, nonfasting) plasma glucose concentration ≥200 mg/dL, or

-

A1C level ≥6.5%Glucose criteria (i.e., FPG or 2-h glucose after a 75-g oral glucose load) are preferred for the diagnosis of DM. The same test—plasma glucose or A1C measurement—should be repeated on a different day to confirm the diagnosis of DM. However, a glucose level ≥200 mg/dL in the presence of DM symptoms does not need to be confirmed (Grade B; BEL 3).

R3. Prediabetes may be identified by the presence of impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), which is a plasma glucose value of 140 to 199 mg/dL 2 hours after ingesting 75 g of glucose, and/or impaired fasting glucose (IFG), which is a fasting glucose value of 100 to 125 mg/dL (Table 6) (Grade B; BEL 2). A1C values between 5.5 and 6.4% inclusive should be a signal to do more specific glucose testing (Grade D; BEL 4). For prediabetes, A1C testing should be used only as a screening tool; FPG measurement or an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) should be used for definitive diagnosis (Grade B; BEL 2). Metabolic syndrome based on National Cholesterol Education Program IV Adult Treatment Panel III criteria should be considered a prediabetes equivalent (Grade C; BEL 3).

R4. Pregnant females with DM risk factors should be screened at the first prenatal visit for undiagnosed T2D using standard criteria (Grade D; BEL 4). At 24 to 28 weeks’ gestation, all pregnant subjects should be screened for gestational DM (GDM) with a 2-hour OGTT using a 75-g glucose load. GDM may be diagnosed using the following plasma glucose criteria: FPG >92 mg/dL, 1-hour post-glucose challenge value ≥180 mg/dL, or 2-hour value ≥153 mg/dL (Grade C; BEL 3).

R5. DM represents a group of heterogeneous metabolic disorders that develop when insulin secretion is insufficient to maintain normal plasma glucose levels. T2D is the most common form of DM, accounting for more than 90% of cases, and is typically identified in patients who are overweight or obese and/or have a family history of DM, a history of GDM, or meet the criteria for metabolic syndrome. Once DM glucose criteria have been satisfied, T2D should be diagnosed based on patient history, phenotype, and lack of autoantibodies characteristic of T1D (Grade A; BEL 1). Most persons with T2D have evidence of insulin resistance (such as elevated fasting or postprandial plasma insulin and/or elevated C-peptide concentrations), high triglycerides, and/or low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C]).

R6. T1D is usually characterized by absolute insulin deficiency and should be confirmed by the presence of autoantibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase, pancreatic islet β cells (tyrosine phosphatase IA-2), zinc transporter (ZnT8), and/or insulin (Grade A; BEL 1). Some forms of T1D have no evidence of autoimmunity and have been termed idiopathic. T1D can also occur in people who are overweight or obese. Therefore, documenting the levels of insulin and C-peptide and the presence or absence of immune markers in addition to the clinical presentation may help establish the correct diagnosis to distinguish between T1D and T2D in children or adults and determine appropriate treatment (Grade B; BEL 2).

R7. Any child or young adult with an atypical presentation, course, or response to therapy may be evaluated for monogenic DM (formerly maturity-onset diabetes of the young); diagnostic likelihood is strengthened by a family history over 3 generations, suggesting autosomal dominant inheritance (Grade C; BEL 3).

Table 5. Risk Factors for Prediabetes and T2D: Criteria for Testing for Diabetes in Asymptomatic Adults.

| Age ≥45 years without other risk factors |

| CVD or family history of T2D |

| Overweight or obesea |

| Sedentary lifestyle |

| Member of an at-risk racial or ethnic group: Asian, African American, Hispanic, Native American (Alaska Natives and American Indians), or Pacific Islander |

| HDL-C <35 mg/dL (0.90 mmol/L) and/or a triglyceride level >250 mg/dL (2.82 mmol/L) |

| IGT, IFG, and/or metabolic syndrome |

| PCOS, acanthosis nigricans, NAFLD |

| Hypertension (BP >140/90 mm Hg or on therapy for hypertension) |

| History of gestational diabetes or delivery of a baby weighing more than 4 kg (9 lb) |

| Antipsychotic therapy for schizophrenia and/or severe bipolar disease |

| Chronic glucocorticoid exposure |

| Sleep disorders in the presence of glucose intolerance (A1C >5.7%, IGT, or IFG on previous testing), including OSA, chronic sleep deprivation, and night-shift occupation |

Abbreviations: A1C = hemoglobin A1C; BP = blood pressure; CVD = cardiovascular disease; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IFG = impaired fasting glucose; IGT = impaired glucose tolerance; NAFLD = nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea; PCOS = polycystic ovary syndrome.

Testing should be considered in all adults who are obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2), and those who are overweight (BMI 25 to <30 kg/m2) and have additional risk factors. At-risk BMI may be lower in some ethnic groups, in whom parameters such as waist circumference and other factors may be used.

Table 6. Glucose Testing and Interpretation.

| Normal | High Risk for Diabetes | Diabetes |

|---|---|---|

| FPG <100 mg/dL | IFG FPG ≥100-125 mg/dL |

FPG ≥126 mg/dL |

| 2-h PG <140 mg/dL | IGT 2-h PG ≥140-199 mg/dL |

2-h PG ≥200 mg/dL Random PG ≥200 mg/dL + symptoms |

| A1C <5.5% | 5.5 to 6.4% For screening of prediabetesa |

≥6.5% Secondaryb |

Abbreviations: A1C = hemoglobin A1C; FPG = fasting plasma glucose; IFG = impaired fasting glucose; IGT = impaired glucose tolerance; PG = plasma glucose.

A1C should be used only for screening prediabetes. The diagnosis of prediabetes, which may manifest as either IFG or IGT, should be confirmed with glucose testing.

Glucose criteria are preferred for the diagnosis of DM. In all cases, the diagnosis should be confirmed on a separate day by repeating glucose or A1C testing. When A1C is used for diagnosis, follow-up glucose testing should be done when possible to help manage DM.

3.Q2. How is Prediabetes Managed?

R8. T2D can be prevented or at least delayed by intervening in persons who have prediabetes (see Table 6 for glucose criteria) (Grade A, BEL 1). Frequent measurement of FPG and/or an OGTT may be used to assess the glycemic status of patients with prediabetes (Grade C; BEL 3). The clinician should manage CVD risk factors (especially elevated blood pressure and/or dyslipidemia) and excessive weight, and monitor these risks at regular intervals (Grade C; BEL 3).

R9. Persons with prediabetes should modify their lifestyle, including initial attempts to lose 5 to 10% of body weight if overweight or obese and participate in moderate physical activity (e.g., walking) at least 150 minutes per week (Grade B; BEL 3). Physicians should recommend patients participate in organized lifestyle change programs with follow-up, where available, because behavioral support will benefit weight-loss efforts (Grade B; BEL 3).

R10. In addition to lifestyle modification, medications including metformin, acarbose, or thiazolidinediones (TZDs) should be considered for patients who are at moderate-to-high risk for developing DM, such as those with a first-degree relative with DM (Grade A; BEL 1).

3.Q3. What are the Glycemic Treatment Goals of DM?

3.Q3.1. Outpatient Glucose Targets for Nonpregnant Adults

-

R11. Glucose targets should be individualized and take into account life expectancy, disease duration, presence or absence of micro- and macrovascular complications, CVD risk factors, comorbid conditions, and risk for hypoglycemia, as well as the patient’s psychological status (Grade A; BEL 1). In general, the goal of therapy should be an A1C level ≤6.5% for most nonpregnant adults, if it can be achieved safely (Table 7) (Grade D; BEL 4). To achieve this target A1C level, FPG may need to be <110 mg/dL, and the 2-hour PPG may need to be <140 mg/dL (Table 7) (Grade B, BEL 2).

In adults with recent onset of T2D and no clinically significant CVD, glycemic control aimed at normal (or near-normal) glycemia should be considered, with the aim of preventing the development of micro- and macrovascular complications over a lifetime, if it can be achieved without substantial hypoglycemia or other unacceptable adverse consequences (Grade A; BEL 1). Although it is uncertain that the clinical course of established CVD is improved by strict glycemic control, the progression of microvascular complications clearly is delayed. A less stringent glucose goal should be considered (A1C 7 to 8%) in patients with history of severe hypoglycemia, limited life expectancy, advanced renal disease or macrovascular complications, extensive comorbid conditions, or long-standing DM in which the A1C goal has been difficult to attain despite intensive efforts, so long as the patient remains free of polydipsia, polyuria, polyphagia, and other hyperglycemia-associated symptoms (Grade A; BEL 1).

Table 7. Comprehensive Diabetes Care Treatment Goals.

| Parameter | Treatment goal | Reference (evidence level and study design) |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose | ||

| A1C, % | Individualize on the basis of age, comorbidities, duration of disease; in general ≤6.5 for most; closer to normal for healthy; less stringent for “less healthy” |

(4 [EL 4; NE]) |

| FPG, mg/dL | <110 | |

| 2-h PPG, mg/dL | <140 | |

| Inpatient hyperglycemia: glucose, mg/dL |

140-180 | (5 [EL 4; consensus NE]) |

| Blood pressure | Individualize on the basis of age, comorbidities, and duration of disease, with general target of: |

(6 [EL 4; NE]) |

| Systolic, mm Hg | ~130 | |

| Diastolic, mm Hg | ~80 | |

| Lipids | ||

| LCL-C, mg/dL | <100, moderate risk <70, high risk |

(4 [EL 4; NE]) |

| Non-HDL-C, mg/dL | <130, moderate risk <100, high risk |

|

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | <150 | |

| TC/HDL-C ratio | <3.5, moderate risk <3.0, high risk |

|

| ApoB, mg/dL | <90, moderate risk <80, high risk |

|

| LDL particles | <1,200 moderate risk <1,000 high risk |

|

| Weight | ||

| Weight loss | Reduce weight by at least 5 to 10%; avoid weight gain |

(4 [EL 4; NE]) |

| Anticoagulant therapy | ||

| Aspirin | For secondary CVD prevention or primary prevention for patients at very high riska |

(7 [EL 1; MRCT but small sample sizes and event rates]; 8 [EL 1; MRCT]; 9 [EL 1; MRCT]; 10 [EL 2; PCS]) |

Abbreviations: ApoB = apolipoprotein B; BEL = best evidence level; CVD = cardiovascular disease; DM = diabetes mellitus; EL = evidence level; FPG = fasting plasma glucose; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IFG = impaired fasting glucose; IGT = impaired glucose tolerance; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; MRCT = meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials; NE = no evidence (theory, opinion, consensus, review, or preclinical study); PCS = prospective cohort study; PPG = postprandial glucose; TC = total cholesterol.

High risk, DM without cardiovascular disease; very high risk, DM plus CVD.

3.Q3.2. Inpatient Glucose Targets for Nonpregnant Adults

R12. For most hospitalized persons with hyperglycemia in the intensive care unit (ICU), a glucose range of 140 to 180 mg/dL is recommended, provided this target can be safely achieved (Table 7) (Grade D; BEL 4). For general medicine and surgery patients in non-ICU settings, a premeal glucose target <140 mg/dL and a random blood glucose <180 mg/dL are recommended (Grade C; BEL 3).

3.Q3.3. Outpatient Glucose Targets for Pregnant Subjects

R13. For females with GDM, the following glucose goals should be considered: preprandial glucose concentration ≤95 mg/dL and either a 1-hour postmeal glucose value ≤140 mg/dL or a 2-hour postmeal glucose value ≤120 mg/dL (Grade D; BEL 4). For females with pre-existing T1D or T2D who become pregnant, glucose should be controlled to meet the following goals (but only if they can be safely achieved): premeal, bedtime, and overnight glucose values between 60 and 99 mg/dL; a peak PPG value between 100 and 129 mg/dL; and an A1C value ≤6.0% (Grade D; BEL 4).

3.Q4. How are Glycemic Targets Achieved for T2D?

3.Q4.1. Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes

R14. Medical nutrition therapy (MNT) is recommended for all people with prediabetes or DM, including T1D, T2D, GDM, and other less common forms of DM. MNT must be individualized, generally via evaluation and teaching by a trained nutritionist or registered dietitian or a physician knowledgeable in nutrition (Grade D; BEL 4). The goals of MNT are to improve overall health by teaching patients to eat a diet containing a variety of foods in appropriate amounts to help manage body weight, glucose, lipids, and blood pressure (Table 8). Nutritional recommendations should take into account personal and cultural preferences, as well as the individual’s knowledge of nutrition, willingness to change eating habits, and barriers to change. For people on insulin therapy, insulin dosage adjustments should match carbohydrate intake (e.g., with use of carbohydrate counting).

R15. Patients should engage in at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity exercise such as brisk walking (15- to 20-minute mile) or its equivalent (Grade B; BEL 2). Persons with T2D should also incorporate flexibility and strength-training exercises (Grade B; BEL 2). Patients must be evaluated initially for contraindications and/or limitations to physical activity, and then an exercise prescription should be developed for each patient according to both goals and activity limitations. Physical activity programs should begin slowly and build up gradually (Grade D; BEL 4). Patients with T1D should also exercise regularly; however, individuals requiring insulin therapy should be educated about the acute and chronic effects of exercise on blood glucose levels and learn how to adjust insulin dosages and food intake to maintain good glucose control before, during, and after exercise to avoid significant hypo- or hyperglycemia (Grade D; BEL 4).

Table 8. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Healthful Eating Recommendations for Patients With Diabetes Mellitus.

| Topic | Recommendation | Reference (evidence level and study design) |

|---|---|---|

| General eating habits |

Eat regular meals and snacks; avoid fasting to lose weight Consume plant-based diet (high in fiber, low calories/glycemic index, and high in phytochemicals/antioxidants) Understand Nutrition Facts Label information Incorporate beliefs and culture into discussions Use mild cooking techniques instead of high-heat cooking Keep physician-patient discussions informal |

(11 [EL 3; SS]; 12 [EL 4; position NE]; 13 [EL 4; position NE]; 14 [EL 4; review NE]; 15 [EL 3; SS]; 16 [EL 1; RCT]; 17 [EL 3; SS]) |

| Carbohydrate | Explain the 3 types of carbohydrates—sugars, starch, and fiber—and the effects on health for each type Specify healthful carbohydrates (fresh fruits and vegetables, legumes, whole grains); target 7-10 servings per day Lower-glycemic index foods may facilitate glycemic control (glycemic index score <55 out of 100: multigrain bread, pumpernickel bread, whole oats, legumes, apple, lentils, chickpeas, mango, yams, brown rice), but there is insufficient evidence to support a formal recommendation to educate patients that sugars have both positive and negative health effects |

(13 [EL 4; position NE]; 18 [EL 4; review NE]; 19 [EL 4; review NE]; 20 [EL 4; review NE]; 21 [EL 4; NE review]; 22 [EL 4; review NE]; 23 [EL 4; review NE]) |

| Fat | Specify healthful fats (low mercury/contaminant-containing nuts, avocado, certain plant oils, fish) Limit saturated fats (butter, fatty red meats, tropical plant oils, fast foods) and trans fat; choose fat-free or low-fat dairy products |

(24 [EL 4; review NE]; 25 [EL 4; review NE]; 26 [EL 4; NE review]) |

| Protein | Consume protein in foods with low saturated fats (fish, egg whites, beans); there is no need to avoid animal protein Avoid or limit processed meats |

(13 [EL 4; position NE]; 27 [EL 2; MNRCT]; 28 [EL 2; PCS, data may not be generalizable to patients with diabetes already]) |

| Micronutrients | Routine supplementation is not necessary; a healthful eating meal plan can generally provide sufficient micronutrients Specifically, chromium; vanadium; magnesium; vitamins A, C, and E; and CoQ10 are not recommended for glycemic control Vitamin supplements should be recommended to patients at risk of insufficiency or deficiency |

(29 [EL 4; CPG NE]) |

Abbreviations: BEL = best evidence level; CPG = clinical practice guideline; EL = evidence level; MNRCT = meta-analysis of non-randomized prospective or case-controlled trials; NE = no evidence (theory, opinion, consensus, review, or preclinical study); PCS = prospective cohort study; RCT = randomized controlled trial.

3.Q4.2. Antihyperglycemic Pharmacotherapy for T2D

R16. Pharmacotherapy for T2D should be prescribed based on suitability for the individual patient’s characteristics (Grade D; BEL 4). As shown in Table 9, antihyperglycemic agents vary in their impact on FPG, PPG, weight, and insulin secretion or sensitivity, as well as the potential for hypoglycemia and other adverse effects. The initial choice of an agent involves comprehensive patient assessment including a glycemic profile obtained by self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) and the patient’s A1C, weight, and presence of comorbidities. Minimizing the risks of hypoglycemia and weight gain are priorities.

R17. Details about the effects of and rationale for available antihyperglycemic agents can be found in the 2015 AACE Comprehensive Diabetes Management Algorithm Consensus Statement (4). The AACE recommends initiating therapy with metformin, a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, a dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitor, a sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, or an α-glucosidase inhibitor for patients with an entry A1C <7.5% (Grade C; BEL 3). A TZD, sulfonylurea, or glinide may be considered as alternative therapies but should be used with caution due to side-effect profiles (Grade C; BEL 3). For patients with entry A1C levels >7.5%, the AACE recommends initiating treatment with metformin (unless contraindicated) plus a second agent, with preference given to agents with a low potential for hypoglycemia that are weight neutral or associated with weight loss (Grade C; BEL 3). This includes GLP-1 receptor agonists, SGLT2 inhibitors, or DPP-4 inhibitors as the preferred second agents; TZDs and basal insulin may be considered as alternatives. Colesevelam, bromocriptine, or an α-glucosidase inhibitor have limited glucoselowering potential but also carry a low risk of adverse effects and may be useful for glycemic control in some situations (Grade C; BEL 3). Sulfonylureas and glinides are considered the least desirable alternatives due to the risk of hypoglycemia (Grade B; BEL 2). For patients with an entry A1C >9.0% who have symptoms of hyperglycemia, insulin therapy alone or in combination with metformin or other oral agents is recommended (Grade A; BEL 1). Pramlintide and the GLP-1 receptor agonists can be used as adjuncts to prandial insulin therapy to reduce postprandial hyperglycemia, A1C, and weight (Grade B; BEL 2). The long-acting GLP-1 receptor agonists also reduce fasting glucose.

R18. Insulin should be considered for T2D when noninsulin antihyperglycemic therapy fails to achieve target glycemic control or when a patient, whether drug naïve or not, has symptomatic hyperglycemia (Grade A; BEL 1). Therapy with long-acting basal insulin should be the initial choice in most cases (Grade C; BEL 3). The insulin analogs glargine and detemir are preferred over intermediate-acting neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) because analog insulins are associated with less hypoglycemia (Grade C; BEL 3). When control of postprandial hyperglycemia is needed, preference should be given to rapid-acting insulins (the analogs lispro, aspart, and glulisine or inhaled insulin) over regular human insulin because the former have a more rapid onset and offset of action and are associated with less hypoglycemia (Grade B; BEL 2). Premixed insulin formulations (fixed combinations of shorter- and longer-acting components) of human or analog insulin may be considered for patients in whom adherence to more intensive insulin regimens is problematic; however, these preparations have reduced dosage flexibility and may increase the risk of hypoglycemia compared with basal insulin or basal-bolus regimens (Grade B; BEL 2). Basal-bolus insulin regimens are flexible and recommended for intensive insulin therapy (Grade B; BEL 3).

R19. Intensification of pharmacotherapy requires glucose monitoring and medication adjustment at appropriate intervals (e.g., every 3 months) when treatment goals are not achieved or maintained (Grade C; BEL 3). The 2015 AACE algorithm outlines treatment choices on the basis of the A1C level (4 [EL 4; NE]).

Table 9. Effects of Diabetes Drug Actiona.

| Met | GLP1RA | SGLT2I | DPP4I | TZD | AGI | Coles | BCR-QR | SU/Glinide | Insulin | Pram | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPG lowering | Moderate |

Mild to

moderate b |

Moderate | Mild | Moderate | Neutral | Mild | Neutral |

SU: moderate Glinide: mild |

Moderate to marked (basal insulin or premixed) |

Mild |

| PPG lowering | Mild |

Moderate to

marked |

Mild | Moderate | Mild | Moderate | Mild | Mild | Moderate |

Moderate to marked (short/ rapid-acting insulin or premixed) |

Moderate to

marked |

| NAFLD benefit | Mild | Mild | Neutral | Neutral | Moderate | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral |

| Hypoglycemia | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral |

SU: moderate to

severe Glinide: mild to moderate |

Moderate to severe,

especially with short/rapid-acting or premixed |

Neutral |

| Weight | Slight loss | Loss | Loss | Neutral | Gain | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Gain | Gain | Loss |

| Renal impairment/ GU |

Contraindicated

in stage 3B, 4, 5 CKD |

Exenatide

contraindicated CrCl <30 mg/ mL |

GU

infection risk |

Dose adjustment may be necessary (except linagliptin) |

May

worsen fluid retention |

Neutral | Neutral | Neutral |

Increased

hypoglycemia risk |

Increased risks of

hypoglycemia and fluid retention |

Neutral |

| GI adverse effects |

Moderate |

Moderate

(caution in PIs about pancreatitis) |

Neutral | Neutral (caution in PIs about pancreatitis) |

Neutral | Moderate | Mild | Moderate | Neutral | Neutral | Moderate |

| CHF | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral (caution: possibly increased CHF hospitalization risk in CV safety trial) |

Moderate | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral |

| CVD | Possible benefit | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Safe | ? | Neutral | Neutral |

| Bone | Neutral | Neutral | Bone loss | Neutral |

Moderate

bone loss |

Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral | Neutral |

Abbreviations: AGI = α-glucosidase inhibitors; BCR-QR = bromocriptine quick release; CHF = congestive heart failure; CKD = chronic kidney disease; Coles = colesevelam; CrCl = creatinine clearance; CV = cardiovascular; DPP4I = dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors; FPG = fasting plasma glucose; GI = gastrointestinal; GLP1RA = glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists; GU = genitourinary; Met = metformin; NAFLD = nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; PI = prescribing information; PPG = postprandial glucose; SGLT2I = sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors; SU = sulfonylureas; TZD = thiazolidinediones.

Boldface type highlights a benefit or potential benefit; italic type highlights adverse effects.

Mild: albiglutide and exenatide; moderate: dulaglutide, exenatide extended release, and liraglutide.

3.Q5. How Should Glycemia in T1D be Managed?

- R20. Insulin must be used to treat T1D (Grade A; BEL 1). Physiologic insulin regimens, which provide both basal and prandial insulin, should be used for most patients with T1D (Grade A; BEL 1). These regimens involve the use of insulin analogs for most patients with T1D (Grade A; BEL 1) and include the following approaches:

- Multiple daily injections (MDI), which usually involve 1 to 2 subcutaneous injections daily of basal insulin to control glycemia between meals and overnight, and subcutaneous injections of prandial insulin or inhaled insulin before each meal to control meal-related glycemia (Grade A; BEL 1)

- Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) to provide a more physiologic way to deliver insulin, which may improve glucose control while reducing risks of hypoglycemia (Grade A; BEL 1)

3.Q6. How is Hypoglycemia Managed?

R21. Oral administration of rapidly absorbed glucose should be used to treat hypoglycemia (generally defined as any blood glucose <70 mg/dL with or without symptoms including anxiety, palpitations, tremor, sweating, hunger, paresthesias, behavioral changes, cognitive dysfunction, seizures, and coma; severe hypoglycemia is defined as any that requires assistance from another person to administer carbohydrates or glucagon or take other corrective action). If the patient is unable to swallow or is unresponsive, subcutaneous or intramuscular glucagon or intravenous glucose should be given by a trained family member or medical personnel (Grade A; BEL 1). The usual adult dose of subcutaneous glucagon is 1 mg (1 unit). For children weighing less than 44 lbs (20 kg), the dose is half the adult dose (0.5 mg). As soon as the patient is awake and able to swallow, he or she should receive a rapidly absorbed source of carbohydrate (e.g., fruit juice) followed by a snack or meal containing both protein and carbohydrates (e.g., cheese and crackers or a peanut butter sandwich) (Grade C; BEL 3). Patients with severe hypoglycemia and altered mental status or with persistent hypoglycemia need to be hospitalized (Grade A; BEL 1). If the patient has hypoglycemic unawareness and hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure, several weeks of hypoglycemia avoidance may reduce the risk or prevent recurrence of severe hypoglycemia. In patients with T2D who become hypoglycemic and have been treated with an α-glucosidase inhibitor in addition to insulin or an insulin secretagogue, oral glucose or lactose-containing foods (dairy products) must be given because α-glucosidase inhibitors inhibit the breakdown and absorption of complex carbohydrates and disaccharides (Grade C; BEL 3).

3.Q7. How is Hypertension Managed in Patients with Diabetes?

R22. The blood pressure goal for persons with DM or prediabetes should be individualized and should generally be about 130/80 mm Hg (Table 7) (Grade B; BEL 2). A more intensive goal (e.g., <120/80 mm Hg) should be considered for some patients, provided this target can be reached safely without adverse effects from medication (Grade C; BEL 3). More relaxed goals may be considered for frail patients with complicated comorbidities or those who have adverse medication effects (Grade D; BEL 4).

R23. Therapeutic lifestyle modification for hypertension should include dietary interventions that emphasize reduced salt intake such as DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension), physical activity, and, as needed, consultation with a registered dietitian and/or certified diabetes educator (CDE) (Grade A; BEL 1). Pharmacologic therapy should be used to achieve targets unresponsive to therapeutic lifestyle changes alone (Grade A; BEL 1). The clinician should select antihypertensive agents on the basis of their ability to reduce blood pressure and prevent or slow the progression of nephropathy and retinopathy; angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) are preferred in patients with DM (Grade C; BEL 3). Combination therapy should be used when needed to achieve blood pressure targets, including calcium channel antagonists, diuretics, combined α/β-adrenergic blockers, and newer-generation β-adrenergic blockers in addition to agents that block the renin-angiotensin system (Grade A; BEL 1).

3.Q8. How is Dyslipidemia Managed in Patients with Diabetes?

R24. All patients with DM should be screened for dyslipidemia (Grade B; BEL 2). Therapeutic recommendations should include lifestyle changes and, as needed, consultation with a registered dietitian and/or CDE (Grade B; BEL 2).

R25. Because macrovascular disease may be evident prior to the diagnosis of DM, lipid levels of patients with prediabetes should be managed in the same manner as those of patients with DM (Grade D; BEL 4).

R26. In persons with DM or prediabetes and no atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) or major cardiovascular risk factors (i.e., moderate CVD risk), treatment efforts should target a low-density lipo-protein cholesterol (LDL-C) goal of <100 mg/dL and a non-HDL-C goal of <130 mg/dL (Grade B; BEL 2). In high-risk patients (those with DM and established ASCVD or at least 1 additional major ASCVD risk factor such as hypertension, family history, low HDL-C, or smoking), a statin should be started along with therapeutic lifestyle changes regardless of baseline LDL-C level (Grade A; BEL 1). In these patients, an LDL-C level <70 mg/dL and a non-HDL-C treatment goal <100 mg/dL should be targeted (Table 7) (Grade B; BEL 2). If the triglyceride concentration is ≥200 mg/dL, non-HDL-C may be used to predict ASCVD risk (Grade C; BEL 3). Secondary treatment goals may be considered, including apolipoprotein B (ApoB) <80 mg/dL and low-density lipoprotein particles (LDL-P) <1,000 nmol/L in patients with ASCVD or at least 1 major risk factor, and <90 mg/dL or <1,200 nmol/L in patients without ASCVD and no additional risk factors, respectively (Grade D; BEL 4).

R27. Pharmacologic therapy should be used to achieve lipid targets unresponsive to therapeutic lifestyle changes alone (Grade A; BEL 1). Statins are the treatment of choice in the absence of contraindications. Statin dosage should always be adjusted to achieve LDL-C and non-HDL-C goals (Table 7) unless limited by adverse effects or intolerance (Grade A; BEL 1). Combining the statin with a bile acid sequestrant, niacin, and/or cholesterol absorption inhibitor should be considered when the desired target cannot be achieved with the statin alone; these agents may be used instead of statins in cases of statin-related adverse events or intolerance (Grade C; BEL 3). In patients who have LDL-C levels at goal but triglyceride concentrations ≥200 mg/dL and low HDL-C (<35 mg/dL), treatment protocols including the use of fibrates, niacin, or high-dose omega-3 fatty acids may be used to achieve the non-HDL-C goal (Table 7) (Grade B; BEL 2). High-dose omega-3 fatty acids, fibrates, or niacin may also be used to reduce triglyceride levels ≥500 mg/dL (Grade C; BEL 3).

3.Q9. How is Nephropathy Managed in Patients with Diabetes?

R28. Beginning 5 years after diagnosis in patients with T1D (if diagnosed before age 30) or at diagnosis in patients with T2D and those with T1D diagnosed after age 30, annual assessment of serum creatinine to determine the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and urine albumin excretion rate (AER) should be performed to identify, stage, and monitor progression of diabetic nephropathy (Grade C; BEL 3). Patients with nephropathy should be counseled regarding the need for optimal glycemic control, blood pressure control, dyslipidemia control, and smoking cessation (Grade B; BEL 2). In addition, they should have routine monitoring of albuminuria, kidney function electrolytes, and lipids (Grade B; BEL 2). Associated conditions such as anemia and bone and mineral disorders should be assessed as kidney function declines (Grade D; BEL 4). Referral to a nephrologist is recommended well before the need for renal replacement therapy (Grade D; BEL 4).

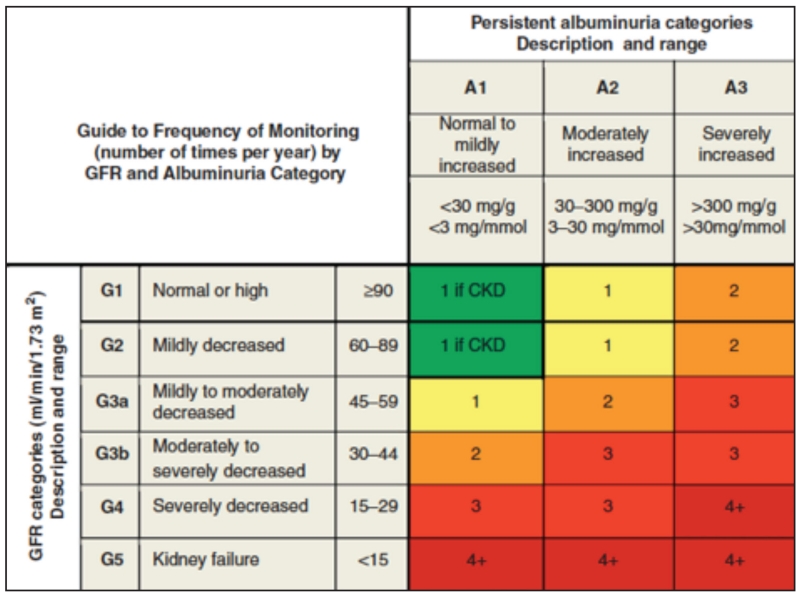

R29. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockade is recommended for patients with DM who have chronic kidney disease (CKD) categories G2, G3a, G3b, and if slow progression is demonstrated, G4 (see Fig. 2 for category definitions) (Grade A; BEL 1). Serum potassium levels should be closely monitored (Grade A; BEL 1). RAAS-blocking drugs are not safe for use in pregnant subjects. ACE inhibitors and ARBs should not be used together due to increased risks of adverse effects, particularly hyperkalemia (Grade B; BEL 2).

R30. Weight loss with regular exercise is recommended for patients with DM and category G2 to G4 CKD (Grade D; BEL 4).

Fig. 2.

GFR and albuminuria grid illustrating the risk of progression by color intensity. The number in each box suggests the frequency of monitoring (number of times per year). Green indicates stable disease with annual follow-up measurements if CKD is present; yellow indicates caution and calls for ≥1 measurement per year; orange requires 2 measurements per year; red calls for 3 measurements per year, and deep red may require close monitoring at a frequency of 4 times or more per year (at least every 1-3 months). These general parameters are based on expert opinion and must take into account underlying comorbid conditions and disease state, as well as the likelihood of a change in management for any individual patient. CKD = chronic kidney disease; GFR = glomerular filtration rate. Frequency of recommendations from the KDIGO CKD Workgroup (30 [EL 4; NE]; 31 [EL 4; NE]). Modified and reprinted with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Kidney International 2011;80(1):17-28, copyright 2011.

3.Q10. How is Retinopathy Managed in Patients with Diabetes?

R31. At the time of diagnosis, patients with T2D should be referred to an experienced ophthalmologist for a dilated eye examination (Grade C; BEL 3). Follow-up with eyecare specialists should typically occur on an annual basis, but patients with T2D who have had a negative ophthalmologic examination may be screened every 2 years (Grade B; BEL 2). In patients with T1D, a referral should be made within 5 years of diagnosis (Grade C; BEL 3). Females who are pregnant and have DM should be referred for frequent/repeated eye examinations during pregnancy and 1 year postpartum (Grade B; BEL 2). Patients with active retinopathy should have examinations more than once a year, as should patients receiving vascular endothelial growth factor therapy (Grade C; BEL 3). Optimal glucose, blood pressure, and lipid control should be implemented to slow the progression of retinopathy (Grade A; BEL 1).

3.Q11. How is Neuropathy Diagnosed and Managed in Patients with Diabetes?

R32. Diabetic neuropathy may be diagnosed clinically but also must be differentiated from other neurologic conditions. Patients with T1D should have a complete neurologic evaluation 5 years after the diagnosis of DM and subsequent annual evaluations (Grade B; BEL 2). Patients with T2D should have their first neurologic examination at the time of diagnosis and yearly thereafter (Grade B; BEL 2). This exam should consist of a complete foot inspection including assessment of foot structure and deformity, skin temperature and integrity, the presence of ulcers, vascular status, presence of pedal pulses, and toe and foot amputations (Grade B; BEL 2). For a complete discussion of diabetic foot assessment, refer to the American Diabetes Association (ADA) Foot Care Task Force report, which has been endorsed by the AACE (32). Neurologic testing may include assessment of sensation using 1- and 10-g monofilaments; vibration perception using a 128-Hz tuning fork; ankle reflexes; and touch, pinprick, and warm and cold thermal sensations (Grade B; BEL 2). Painful neuropathies may have no physical signs, and diagnosis may require skin biopsy or other surrogate measures of small-fiber neuropathy (SFN) (Grade D; BEL 4). Screening for cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy should be performed at diagnosis of T2D or 5 years after the diagnosis of T1D and then annually (Grade D; BEL 4). Tests should include time and frequency domain measures of heart rate variability with deep inspiration, Valsalva maneuver, and blood pressure change from a lying to standing position (Grade D; BEL 4).

R33. Controlling glucose to individual target levels is recommended to prevent the onset of neuropathy (Grade A; BEL 1). Although nothing has been shown to reverse neuropathy once it is established, there is speculation that interventions that reduce oxidative stress, improve glycemic control, and/or improve dyslipidemia and hypertension might have a beneficial effect on established diabetic neuropathy.

R34. Tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors should be considered for the treatment of painful neuropathy (Grade A; BEL 1).

R35. Large-fiber neuropathies should be managed with strength, gait, and balance training; pain management; orthotics to treat and prevent foot deformities; tendon lengthening for pes equinus from Achilles tendon shortening; and/or surgical reconstruction and full-contact casting for foot ulcers, as needed (Grade B; BEL 2).

R36. SFNs should be managed with foot protection (e.g., padded socks), supportive shoes with orthotics if necessary, regular foot and shoe inspection, prevention of heat injury, and use of emollient creams. For pain management, the medications mentioned in R34 should be considered (Grade B; BEL 2).

3.Q12. How is CVD Managed in Patients with Diabetes?

R37. Because CVD is the primary cause of death for most persons with DM, a DM comprehensive care plan should include modifications of CVD risk factors (Grade B; BEL 2). The cardiovascular risk reduction targets are summarized in Table 7.

R38. The use of low-dosage aspirin (75 to 162 mg daily) is recommended for secondary prevention of CVD (Grade A; BEL 1). Some patients may benefit from higher doses (Grade B; BEL 2). For primary prevention of CVD, aspirin use may be considered for those at high cardiovascular risk (10-year risk >10%) (Grade D; BEL 4).

R39. Measurement of coronary artery calcification or coronary imaging may help assess whether a patient is a reasonable candidate for intensification of glycemic, lipid, and/or blood pressure control (Grade B; BEL 2). Screening for asymptomatic coronary artery disease with various stress tests in patients with T2D has not been clearly demonstrated to improve cardiac outcomes and is therefore not recommended (Grade A; BEL 1).

3.Q13. How is Obesity Managed in Patients with Diabetes?

R40. Obesity should be diagnosed according to body mass index (BMI) (Grade B; BEL 2). Individuals with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 are classified as obese, and those with a BMI of 25 to <30 kg/m2 are overweight. For Southeast Asians and Asian Indians, lower BMI cutpoints may be appropriate. Measurement of waist circumference may be considered for individuals with a BMI between 25 and 35 kg/m2 (Grade D; BEL 4). Those with waist circumference values >102 cm (40 in) for males and > 88 cm (35 in) for females are at higher risk for metabolic disease. In addition to these anthropometric measures, patients should be evaluated for obesity-related complications, including other components of metabolic syndrome, sleep apnea, and osteoarthritis to determine disease severity and facilitate obesity staging (Grade D; BEL 4).

R41. Lifestyle modifications including behavioral changes, reduced calorie diets, and appropriately prescribed physical activity should be implemented as the cornerstone of obesity management (Grade A; BEL 1). Pharmacotherapy for weight loss may be considered when lifestyle modification fails to achieve the targeted goal (Grade A; BEL 1). Pharmacotherapy may be initiated at the same time as lifestyle modification in patients with BMIs of 27 to 29.9 kg/m2 and ≥1 obesity-related complication such as T2D (Grade D; BEL 4). Pharmacotherapy and lifestyle modification may be initiated together in patients with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 regardless of the presence of complications (Grade D; BEL 4). Bariatric surgery should be considered in patients with severe obesity-related complications including T2D if the BMI is ≥35 kg/m2 (Grade B; BEL 2). Patients with T2D who undergo malabsorptive procedures, such as Rouxen-Y gastric bypass or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, must have careful postoperative follow-up because of risks of micronutrient deficiencies and hypoglycemia (Grade D; BEL 4).

3.Q14. What is the Role of Sleep Medicine in the Care of the Patient with Diabetes?

R42. Adults with T2D, especially obese males older than 50 years, should be screened for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which is common in this population (Grade D; BEL 4). This condition should be suspected based on a history of daytime drowsiness and heavy snoring, especially if a bed partner witnesses apneas. Increasing evidence supports home apnea testing. Referral to a sleep specialist should be considered in patients suspected of having OSA or restless leg syndrome and when patients are intolerant of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices (Grade A; BEL 1). CPAP and similar oxygen delivery systems should be used to treat OSA (Grade A; BEL 1). Weight loss may also significantly improve OSA.

3.Q15. How is Diabetes Managed in the Hospital?

R43. Insulin can rapidly control hyperglycemia and therefore should be used for the majority of hospitalized patients with hyperglycemia (Grade A; BEL 1). Intravenous insulin infusion should be used to treat persistent hyperglycemia among critically ill patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) (Grade A; BEL 1). Scheduled subcutaneous insulin therapy with basal, nutritional, and correctional components should be used for glycemic management in noncritically ill patients (Grade A; BEL 1). Insulin dosing should be synchronized with provision of meals or enteral or parenteral nutrition (Grade A; BEL 1). Exclusive use of “sliding scale” insulin should be discouraged (Grade A; BEL 1). Preference should be given to regular insulin for intravenous administration and insulin analogs for subcutaneous administration (Grade D; BEL 4).

R44. All patients, independent of a prior diagnosis of DM, should have laboratory blood glucose testing upon hospital admission (Grade C; BEL 3). Patients with known history of DM should have their A1C measured in the hospital if this assessment has not been performed in the preceding 3 months (Grade D; BEL 4). A1C should also be measured in patients with hyperglycemia in the hospital who do not have a prior diagnosis of DM (Grade D; BEL 4). Glucose monitoring with bedside point-of-care (POC) testing should be initiated in all patients with known DM and in nondiabetic patients receiving therapy associated with high risk of hyperglycemia, such as corticosteroids or enteral or parenteral nutrition (Grade D; BEL 4). Patients with persistent hyperglycemia require ongoing POC testing with treatment similar to patients with known history of DM.

R45. A plan for preventing and treating hypoglycemia should be established for each patient, and hypoglycemic episodes should be documented in the medical record (Grade C; BEL 3).

R46. Appropriate plans for follow-up and care should be documented at hospital discharge for inpatients with a prior history of DM as well as nondiabetic patients with hyperglycemia or increased A1C levels (Grade D; BEL 4). DM discharge planning should start soon after hospitalization, and clear DM management instructions should be provided at discharge (Grade D; BEL 4).

3.Q16. How is a Comprehensive Diabetes Care Plan Established in Children and Adolescents?

R47. The pharmacologic treatment of any form of DM in children should not, at this stage of our knowledge, differ in substance from treatment for adults (Grade D; BEL 4), except in children younger than about 4 years, when bolus premeal insulin may be administered after rather than before a meal due to variable and inconsistent calorie/carbohydrate intake. In children or adolescents with T1D, MDI or CSII insulin regimens are preferred (Grade C; BEL 3). Injection frequencies may become problematic in some school settings. Higher insulin-to-carbohydrate ratios and basal insulin dosages may be needed during puberty (Grade C; BEL 3). Insulin requirements may be increased 20 to 50% during menstrual periods in pubescent girls (Grade C; BEL 3). In children or adolescents with T2D, diet and lifestyle modification should be implemented first (Grade A; BEL 1). Addition of metformin and/or insulin should be considered when glycemic targets are not achievable with lifestyle measures (Grade B; BEL 2). An extensive review of guidelines for the care of children with DM from the International Society of Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes was published in 2009 and is available on their website (33).

R48. T1D in adolescents should be managed in close consultation with the patient and their family members. The ADA; Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF); and National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) offer resources to help with transition planning (34-36).

3.Q17. How Should Diabetes in Pregnancy be Managed?

R49. For females with GDM, glucose should be managed with the following treatment goals: preprandial glucose concentration ≤95 mg/dL and either a 1-hour postmeal glucose ≤140 mg/dL or a 2-hour postmeal glucose ≤120 mg/dL (Grade C; BEL 3).

R50. All females with pre-existing DM (T1D, T2D, or previous GDM) should have access to preconception care to ensure adequate nutrition and glucose control before conception, during pregnancy, and in the postpartum period (Grade B; BEL 2). Preference should be given to rapidacting insulin analogs to treat postprandial hyperglycemia in pregnant subjects (Grade D; BEL 4). Regular insulin is acceptable when analogs are not available. Basal insulin needs should be met using rapid-acting insulin via CSII or by using long-acting insulin (e.g., NPH or detemir, which are U.S. Food and Drug Administration [FDA] pregnancy category B) (Grade A; BEL 1). Although insulin is the preferred treatment during pregnancy, metformin and glyburide have been shown to be effective alternatives that do not cause adverse effects in some females (Grade C; BEL 3).

3.Q18. When and How Should Glucose Monitoring be Used?

R51. A1C should be measured at least twice yearly in all patients with DM and at least 4 times yearly in patients not at target (Grade D; BEL 4).

R52. SMBG should be performed by all patients using insulin (minimum of twice daily and ideally before any insulin injection) (Grade B; BEL 2). More frequent SMBG after meals or in the middle of the night may be required for insulin-taking patients with frequent hypoglycemia, patients not at A1C targets, or those with hypoglycemic symptoms (Grade C; BEL 3). Patients not requiring insulin therapy may benefit from SMBG, especially to provide feedback about the effects of their lifestyle and pharmacologic therapy; testing frequency must be personalized.

R53. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) should be considered for patients with T1D and T2D on basal-bolus therapy to improve A1C levels and reduce hypoglycemia (Grade B; BEL 2). Early reports suggest that even patients not taking insulin may benefit from CGM (Grade D; BEL 4).

3.Q19. When and How Should Insulin Pump Therapy be Used?

R54. Candidates for CSII include patients with T1D and patients with T2D who are insulin dependent (Grade A; BEL 1). CSII should only be used in patients who are motivated and knowledgeable in DM self-care, including insulin adjustment. To ensure patient safety, prescribing physicians must have expertise in CSII therapy, and CSII users must be thoroughly educated and periodically reevaluated. Sensor-augmented CSII, including those with a threshold-suspend function, should be considered for patients who are at risk of hypoglycemia (Grade A; BEL 1).

3.Q20. What is the Imperative for Education and Team Approach in DM Management?

R55. An organized multidisciplinary team may best deliver care for patients with DM (Grade D; BEL 4). Members of such a team can include a primary care physician, endocrinologist, physician assistant, nurse practitioner, registered nurse, dietitian, exercise specialist, and mental health professional. The educational, social, and logistical elements of therapy and variations in successful care delivery associated with age and maturation increase the complexity of caring for children with DM.

R56. Persons with DM should receive comprehensive diabetes self-management education (DSME) at the time of DM diagnosis and subsequently as appropriate (Grade D; BEL 4). DSME improves clinical outcomes and quality of life in individuals with DM by providing the knowledge and skills necessary for DM self-care. Therapeutic lifestyle management must be discussed with all patients with DM or prediabetes at the time of diagnosis and throughout their lifetime (Grade D; BEL 4). This includes MNT (with reduction and modification of caloric and fat intake to achieve weight loss in those who are overweight or obese), appropriately prescribed physical activity, avoidance of tobacco products, and adequate sleep quantity and quality. Additional topics commonly taught in DSME programs outline principles of glycemia treatment options; blood glucose monitoring; insulin dosage adjustments; acute complications of DM; and prevention, recognition, and treatment of hypoglycemia.

3.Q21. Which Vaccinations Should be Given to Patients with Diabetes?

R57. AACE supports the recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) that all patients with DM be vaccinated for influenza and pneumococcal infection. An annual influenza vaccine should be provided to those with DM who are ≥6 months old (Grade C; BEL 3). Furthermore, a pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine should be administered to patients with DM age ≥2 years (Grade C; BEL 3). A single administration of the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) should be administered to adults with DM age 19 to 64 years (Grade C; BEL 3). The 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine should be administered in series with the PPSV23 to all adults aged ≥65 years (Grade C; BEL 3). Revaccination is also indicated for those with nephrotic syndrome, chronic renal disease, and other immunocompromised states, such as posttransplantation.

R58. Hepatitis B vaccinations should be administered to adults 20 to 59 years of age as soon after DM diagnosis as possible (Grade C; BEL 3). Vaccination of adults ≥60 years should be considered based on assessment of risk and likelihood of an adequate immune response (Grade C; BEL 3).

R59. All children and adolescents with DM should receive routine childhood vaccinations according to the normal schedule (Grade C; BEL 3).

R60. The tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis (Tdap) vaccine is typically included with routine childhood vaccinations. However, all adults with DM should receive a tetanus-diphtheria (Td) booster every 10 years (Grade D; BEL 4).

R61. Patients with DM may need other vaccines to protect themselves against other illnesses. Healthcare professionals may consider vaccines for the following diseases based on individual needs of the patient: measles/mumps/rubella, varicella (chicken pox), and polio. In addition, patients traveling to other countries may require vaccines for endemic diseases (Grade D; BEL 4).

3.Q22. How Should Depression be Managed in the Context of Diabetes?

R62. Screening for depression should be performed routinely for adults with DM because untreated depression can have serious clinical implications for patients with DM (Grade A; BEL 1).

R63. Patients with depression should be referred to mental health professionals who are members of the DM care team (Grade D; BEL 4).

3.Q23. What is the Association Between Diabetes and Cancer?

R64. In light of the increased risk of certain cancers in patients with obesity or T2D, healthcare professionals should educate patients regarding this risk and encourage a more healthy lifestyle (Grade D; BEL 4). Weight reduction, regular exercise, and a healthful diet are recommended (Grade C; BEL 3). Individuals with obesity and those with T2D should be screened more often and more rigorously for common cancers and those associated with these metabolic disorders (Grade B; BEL 2).

R65. To date, no definitive relationship has been established between specific antihyperglycemic agents and an increased risk of cancer or cancer-related mortality. Healthcare professionals should be aware of potential associations but should recommend therapeutic interventions based on the risk profiles of individual patients (Grade D; BEL 4).

R66. When a patient with DM has a history of a particular cancer, the physician may consider avoiding a medication that was initially considered disadvantageous to that cancer, even though no proof has been forthcoming (Grade D; BEL 4).

3.Q24. Which Occupations Have Specific Diabetes Management Requirements?

R67. Commercial drivers are at high risk for developing T2D. Persons with DM engaged in various occupations including commercial drivers and pilots, anesthesiologists, and commercial or recreational divers have special management requirements. Treatment efforts for such patients should be focused on agents with reduced likelihood of hypoglycemia (Grade C; BEL 3).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge the medical writing assistance of Amanda M. Justice, who was instrumental in the publication of this guideline.

Abbreviations

- A1C

hemoglobin A1c

- AACE

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists

- ACCORD

Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes

- ACE

angiotensin-converting enzyme

- ADA

American Diabetes Association

- AER

albumin excretion rate

- ApoB

apolipoprotein B

- ARB

angiotensin II receptor blocker

- ASCVD

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- BEL

best evidence level

- BMI

body mass index

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CDE

certified diabetes educator

- CGM

continuous glucose monitoring

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- CPAP

continuous positive airway pressure

- CPG

clinical practice guideline

- CSII

continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DPP-4

dipeptidyl peptidase 4

- DSME

diabetes self-management education

- DSPN

distal symmetric polyneuropathy

- EL

evidence level

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- FDA

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- FPG

fasting plasma glucose

- GDM

gestational diabetes mellitus

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide 1

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HDL-C

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HR

hazard ratio

- ICU

intensive care unit

- IFG

impaired fasting glucose

- IGT

impaired glucose tolerance

- ISF

insulin sensitivity factor

- LDL-C

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-P

low-density lipoprotein particles

- MDI

multiple daily injections

- MNT

medical nutrition therapy

- NPH

neutral protamine Hagedorn

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- PG

plasma glucose

- POC

point-of-care

- PPG

postprandial glucose

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

- Q

clinical question

- R

recommendation

- RAAS

reninangiotensin-aldosterone system

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SFN

small-fiber neuropathy

- SGLT2

sodium glucose cotransporter 2

- SMBG

self-monitoring of blood glucose

- T1D

type 1 diabetes

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

- TZD

thiazolidinedione

Footnotes

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice are systematically developed statements to assist healthcare professionals in medical decision making for specific clinical conditions. Most of the content herein is based on literature reviews. In areas of uncertainty, professional judgment was applied.

These guidelines are a working document that reflects the state of the field at the time of publication. Because rapid changes in this area are expected, periodic revisions are inevitable. We encourage medical professionals to use this information in conjunction with their best clinical judgment. The presented recommendations may not be appropriate in all situations. Any decision by practitioners to apply these guidelines must be made in light of local resources and individual patient circumstances.

REFERENCES

Note: All reference sources are followed by an evidence level (EL) rating of 1, 2, 3, or 4 and the study design. The strongest evidence levels (EL 1 and EL 2) appear in red for easier recognition.

- 1.Handelsman Y, Mechanick JI, Blonde L, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan. Endocr Pract. 2011;17(Suppl 2):1–53. doi: 10.4158/ep.17.s2.1. EL 4; NE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mechanick JI, Camacho PM, Cobin RH, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Protocol for Standardized Production of Clinical Practice Guidelines--2010 update. Endocr Pract. 2010;16:270–83. doi: 10.4158/EP.16.2.270. EL 4; CPG NE; see Fig. 1; Tables 1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mechanick JI, Camacho PM, Garber AJ, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Protocol for Standardized Production of Clinical Practice Guidelines, Algorithms, and Checklists - 2014 Update and the AACe G4G Program. Endocr Pract. 2014;20:692–702. doi: 10.4158/EP14166.PS. EL 4; CPG NE; see Tables 1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. American association of clinical endocrinologists/American college of endocrinology’ comprehensive diabetes management algorithm 2015. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:438–447. doi: 10.4158/EP15693.CS. EL 4; NE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moghissi ES, Korytkowski MT, DiNardo M, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association consensus statement on inpatient glycemic control. Endocr Pract. 2009;15:353–369. doi: 10.4158/EP09102.RA. EL 4; consensus NE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) JAMA. 2014;311:507–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. EL 4; NE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Younis N, Williams S, Ammori B, Soran H. Role of aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:1459–1466. doi: 10.1517/14656561003792538. EL 1; MRCT but small sample sizes and event rates. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration. Baigent C, Blackwell L, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1849–1860. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1. EL 1; MRCT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang C, Sun A, Zhang P, et al. Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.09.029. EL 1; MRCT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ong G, Davis TM, Davis WA. Aspirin is associated with reduced cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetes in a primary prevention setting: the Fremantle Diabetes study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:317–321. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1701. EL 2; PCS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis JE, Arheart KL, LeBlanc WG, et al. Food label use and awareness of nutritional information and recommendations among persons with chronic disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1351–1357. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27684. EL 3; SS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Craig WJ, Mangels AR, American Dietetic Association Position of the American Dietetic Association: vegetarian diets. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1266–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.05.027. EL 4; position NE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dietary Guidelines for Americans . US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2010. 2010. Available at: http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2010.asp [EL 4; position NE] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones JM, Anderson JW. Grain foods and health: a primer for clinicians. Phys Sportsmed. 2008;36:18–33. doi: 10.3810/psm.2008.12.8. EL 4; review NE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pawlak R, Colby S. Benefits, barriers, self-efficacy and knowledge regarding healthy foods; perception of African Americans living in eastern North Carolina. Nutr Res Pract. 2009;3:56–63. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2009.3.1.56. EL 3; SS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birlouez-Aragon I, Saavedra G, Tessier FJ, et al. A diet based on high-heat-treated foods promotes risk factors for diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1220–1226. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28737. EL 1; RCT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corsino L, Svetkey LP, Ayotte BJ, Bosworth HB. Patient characteristics associated with receipt of lifestyle behavior advice. N C Med J. 2009;70:391–398. EL 3; SS. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vuksan V, Rogovik AL, Jovanovski E, Jenkins AL. Fiber facts: benefits and recommendations for individuals with type 2 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2009;9:405–411. doi: 10.1007/s11892-009-0062-1. EL 4; review NE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wheeler ML, Pi-Sunyer FX. Carbohydrate issues: type and amount. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:S34–S39. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.024. EL 4; review NE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trinidad TP, Mallillin AC, Loyola AS, Sagum RS, Encabo RR. The potential health benefits of legumes as a good source of dietary fibre. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:569–574. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509992157. EL 4; review NE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hare-Bruun H, Nielsen BM, Grau K, Oxlund AL, Heitmann BL. Should glycemic index and glycemic load be considered in dietary recommendations? Nutr Rev. 2008;66:569–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00108.x. EL 4; NE review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palou A, Bonet ML, Pico C. On the role and fate of sugars in human nutrition and health. Introduction. Obes Rev. 2009;10(Suppl 1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00560.x. EL 4; review NE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willcox DC, Willcox BJ, Todoriki H, Suzuki M. The Okinawan diet: health implications of a low-calorie, nutrient-dense, antioxidant-rich dietary pattern low in glycemic load. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009;28(Suppl):500S–516S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2009.10718117. EL 4; review NE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minihane AM, Harland JI. Impact of oil used by the frying industry on population fat intake. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2007;47:287–297. doi: 10.1080/10408390600737821. EL 4; review NE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Micha R, Mozaffarian D. Saturated fat and cardiometabolic risk factors, coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes: a fresh look at the evidence. Lipids. 2010;45:893–905. doi: 10.1007/s11745-010-3393-4. EL 4; review NE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Booker CS, Mann JI. Trans fatty acids and cardiovascular health: translation of the evidence base. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;18:448–456. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2008.02.005. EL 4; NE review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Micha R, Wallace SK, Mozaffarian D. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2010;121:2271–2283. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.924977. EL 2; MNRCT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vang A, Singh PN, Lee JW, Haddad EH, Brinegar CH. Meats, processed meats, obesity, weight gain and occurrence of diabetes among adults: findings from Adventist Health Studies. Ann Nutr Metab. 2008;52:96–104. doi: 10.1159/000121365. Erratum in Ann Nutr Metab. 2010;56:232. EL 2; PCS, data may not be generalizable to patients with diabetes already. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]