ABSTRACT

Streptomyces iranensis HM 35 is an alternative rapamycin producer to Streptomyces rapamycinicus. Targeted genetic modification of rapamycin-producing actinomycetes is a powerful tool for the directed production of rapamycin derivatives, and it has also revealed some key features of the molecular biology of rapamycin formation in S. rapamycinicus. The approach depends upon efficient conjugational plasmid transfer from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces, and the failure of this step has frustrated its application to Streptomyces iranensis HM 35. Here, by systematically optimizing the process of conjugational plasmid transfer, including screening of various media, and by defining optimal temperatures and concentrations of antibiotics and Ca2+ ions in the conjugation media, we have achieved exconjugant formation for each of a series of gene deletions in S. iranensis HM 35. Among them were rapK, which generates the starter unit for rapamycin biosynthesis, and hutF, encoding a histidine catabolizing enzyme. The protocol that we have developed may allow efficient generation of targeted gene knockout mutants of Streptomyces species that are genetically difficult to manipulate.

IMPORTANCE The developed protocol of conjugational plasmid transfer from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces iranensis may allow efficient generation of targeted gene knockout mutants of other genetically difficult to manipulate, but valuable, Streptomyces species.

INTRODUCTION

Since the discovery of streptomycin in 1943 (1), streptomycetes have been shown to produce thousands of compounds with possibly beneficial features, e.g., antibiotics, immunosuppressants, or anticancer drugs. Actinomycete-derived metabolites comprise over two-thirds of all known antibiotic compounds (2), and recent genome sequencing programs revealed that their biosynthesis potential has been underestimated. In their 8- to 12-Mb genomes, approximately 20 to 30 gene clusters encode the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (3–5). One of the most important Streptomyces-derived compounds is the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor rapamycin (sirolimus), a “billion dollar molecule” and, after cyclosporine, the most widely used immunosuppressant of microbial origin (6). Rapamycin was previously reported as an antifungal antibiotic produced by Streptomyces hygroscopicus ATCC 29253 (7), later renamed Streptomyces rapamycinicus (8). The rapamycin gene cluster in this strain has been sequenced (9), the biosynthetic pathway has been extensively characterized (10–14), and engineering of the cluster has yielded an impressive range of bioactive modified rapamycins (rapalogs) (15, 16), some in multigram amounts. So far, two other rapamycin-producing species are known: the taxonomically closely related Streptomyces iranensis HM 35 (5, 17) and Actinoplanes sp. strain N902-109 (18). To elucidate the molecular biology of rapamycin formation in these strains and to further exploit the physiological and pharmacological capability of rapamycin derivatives, genetic manipulation of these alternative producing strains is essential. Until now, lack of a workable conjugation protocol has denied access to additional rapamycin derivatives, as well as to other secondary metabolites of potential interest.

The first method enabling gene cloning in Streptomyces was polyethylene glycol-mediated plasmid transformation of protoplasts (19). The procedure required extensive optimization of protoplast formation, regeneration, and transfer, and, thus, numerous strains were only poorly or not at all transformable via protoplasts. The use of electroporation for plasmid DNA transfer into Streptomyces (20, 21) enlarged the number of genetically amenable species, but, again, each strain required distinct optimized conditions. An alternative to protoplast transformation is plasmid transfer via conjugation from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces (22). This approach does not require the recipient to have been extensively characterized genetically. It was further developed to a system that allows not only autonomous replication of the introduced plasmid in the recipient but also its integration via homologous recombination between the cloned DNA and the Streptomyces chromosome (23). This system is currently the basis for most Streptomyces genetic manipulation, and numerous protocols with further optimized steps exist (see, e.g., reference 24–26). Very recently, the Ca2+ ion concentration in the conjugation medium was described as one of the crucial factors that increases the conjugation frequency in Streptomyces (27).

Novel rapamycin structures were obtained from Actinoplanes sp. N902-109 by addition of enzyme inhibitors, precursor feeding and biotransformation approaches (18). Directed gene disruption in S. rapamycinicus was successfully performed by Lomovskaya et al. (28). Using the C+ attP-deleted ϕC31 derivative KC515, the rapamycin polyketide synthase-encoding genes were deleted, leading to complete loss of rapamycin formation. KC515-mediated deletions in one or more genes of rapQONML generated true rapamycin analogues (11, 29). Later, we applied various strategies to create new rapamycin derivatives ranging from classical strain improvement methods like random mutagenesis via UV irradiation (30), chemical mutagenesis (31), protoplast-related techniques (32), or precursor substitution (33) to overexpression of the putative transcription regulator genes rapY, rapR, and rapS (34). A comprehensive study was published by Kendrew et al. (16), who succeeded in rapK deletion in the S. rapamycinicus derivative BIOT-3410 by adapting both antibiotic concentrations and media to the conjugation protocol described by Bierman et al. (23).

However, until now, a standardized routine protocol for targeted genetic modification of either of the alternative rapamycin producers Streptomyces iranensis and Actinoplanes sp. N902-109 has not been available. To gain better access to the genetic manipulation of these interesting species, we systematically optimized available conjugation protocols with special focus on S. iranensis HM 35. Here, we established an effective method of targeted gene deletion in S. iranensis HM 35 through intergeneric conjugation. The modified protocol may prove useful for other strains of Streptomyces and allied genera that have so far proved intractable.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and plasmids.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli DH5α and E. coli BW25113/pIJ790 were used for cloning. The nonmethylating E. coli ET12567 carrying the RK2 derivative pUZ8002 (35) was used as the donor in intergeneric conjugation. Cultivation of all E. coli strains was performed as described in Gust et al. (36) and Sambrook et al. (37). S. iranensis HM 35 was cultured on oatmeal agar plates (38) for sporulation. Potential exconjugants were isolated from MMAM agar plates (16). DNA manipulation and cloning were carried out according to standard protocols (37). S. rapamycinicus ATCC 29253, S. iranensis HM 35, and ΔrapK mutant strains for the rapamycin production were precultivated in seed medium (soluble starch [10 g/liter], soy peptone [6 g/liter], yeast extract [6 g/liter], Casamino Acids [1.5 g/liter], magnesium sulfate [0.5 g/liter], dipotassium phosphate [1 g/liter]; pH 7.0). The main cultivation for rapamycin production was done in YMM medium (yeast extract [5 g/liter], malt extract [5 g/liter], maltose [5 g/liter]; pH 6.0). Concentrations of antibiotics were 50 μg/ml kanamycin, 50 μg/ml apramycin, 25 μg/ml chloramphenicol, and 25 μg/ml nalidixic acid.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristic(s)a | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli strains | ||

| DH5α | General cloning host | 68 |

| BW25113 | Strain for propagation of a recombination plasmid | 69 |

| ET12567/pUZ8002 | Strain for intergeneric conjugation | 70 |

| Streptomyces strains | ||

| S. iranensis HM 35 | Wild-type strain | 17 |

| S. iranensis ΔhutF | S. iranensis hutF::aac(3)IV mutant | This study |

| S. iranensis ΔrapK | S. iranensis rapK::aac(3)IV mutant | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pIJ790 | Helper plasmid, RED/ET recombination plasmid | 47 |

| pRSFDuet-1 | E. coli vector for cloning, Kanr | Novagen |

| pOJ260 | Suicide vector nonreplicating in Streptomyces, Aprr | 23 |

| pRSFDuet_pSG5 | Cloning vector, Kanr, pSG5 replicon | This study |

| pRSFDuet_pSG5_kan | E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle vector, cloning vector, Kanr, pSG5 replicon, oriT | This study |

| pKOSi | E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle vector, cloning vector, Kanr, pSG5 replicon | This study |

| pKOSi_hutF | Vector for disruption of hutF, based on pKOSi, Kanr | This study |

| pKOSi_rapK | Vector for disruption of rapK, based on pKOSi, Kanr | This study |

| pKOSi_ΔhutF | pKOSi_hutF::aac(3)IV Kanr Aprr | This study |

| pKOSi_ΔrapK | pKOSi_rapK::aac(3)IV Kanr Aprr | This study |

| pTNM | Source of pSG5 for pKOSi | 42 |

| pIJ773 | Template for amplification of aac(3)IV (Aprr) cassette + oriT | 47 |

Kanr, kanamycin resistance; Aprr, apramycin resistance.

Generation of plasmid pKOSi.

In the first step, a plasmid that carried the temperature-sensitive replicon pSG5 (39, 40) and the origin of transfer oriT (41) was generated. For this purpose, the 2.86-kb SnaBI/AvrII DNA fragment containing the pSG5 replicon was excised from pTNM (42) and ligated with the 3.5-kb XmnI/AvrII fragment excised from pRSFDuet-1 to generate pRSF_pSG5. Next, the 1.2-kb EcoRV/SpeI DNA fragment containing oriT was excised from pOJ260 and cloned into plasmid pRSF_pSG5 using the XbaI and EcoRV restriction sites, leading to pRSF_pSG5_kan.

In a second step, a pRSF_pSG5_kan derivative plasmid that allowed mutant generation via the λ Red-mediated recombination system was constructed (36). To this end, the origin of transfer oriT was removed from pRSF_pSG5_kan using the restriction sites BspHI and BglII. The resulting 4.3-kb DNA fragment was ligated with a 0.9-kb PCR fragment containing the pRSF1030 replicon (43) and was amplified from pRSF_pSG5_kan with the primers oTN115 (GTTATTGTCTCATGAGCGGATACATATTTG), containing a BspHI restriction site (underlined), and oTN116 (TCCGTCAGATCTATAATGACCCCGAAGCAGGG), containing a BglII restriction site (underlined). Ligation of both fragments led to pKOSi (Fig. 1).

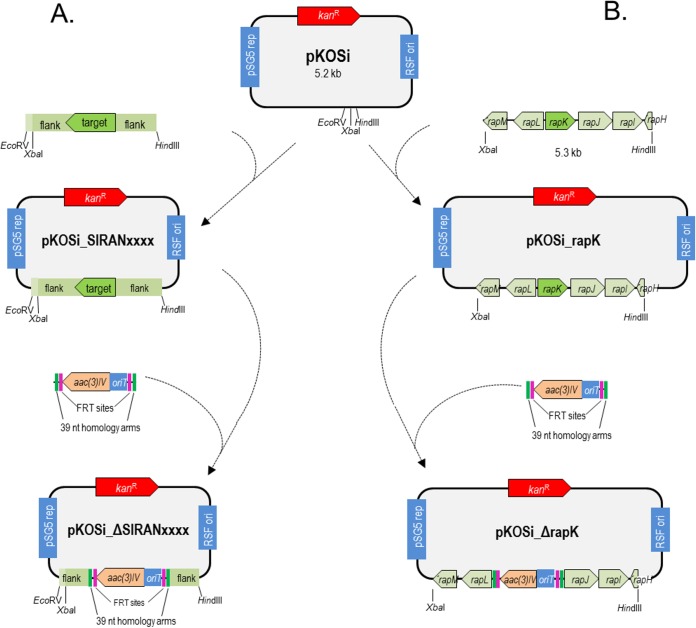

FIG 1.

Generation of deletion plasmids. (A) General procedure. (B) Construction of the deletion vector pKOSi_ΔrapK for rapK as an example. Other deletion plasmids were constructed accordingly. Green, 39-nt homology extensions; pink, FRT sites.

Generation of plasmids for homologous recombination with the Streptomyces chromosome (deletion plasmids).

To inactivate genes in S. iranensis, the corresponding gene sequences together with their 2-kb flanking regions were amplified from S. iranensis genomic DNA using the Phusion Flash high-fidelity PCR master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany). PCR products were individually cloned into pKOSi (Fig. 1) between the XbaI/EcoRV or XbaI/HindIII restriction sites to create pKOSi_SIRANxxxx vectors. Next, the apramycin resistance-conferring gene aac(3)IV was amplified from pIJ773 with 39-nucleotide (nt)-homology arms followed by λ Red-mediated PCR targeting, as described by Gust et al. (36), to yield the final deletion plasmids, which begin with “pKOSi_ΔSIRANxxxx,” where xxxx indicates the annotated gene numbers according to Horn et al. (5) (Fig. 1A). Primers used in these cloning steps are detailed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for generation of deletion plasmids

| Inactivated gene | Primer (sequence) used for amplification of the gene + flanking sequences | Primer (sequence) used for aac(3)IV amplificationa |

|---|---|---|

| hutF | oTN203 (CAAATTAAGCTTTTCGCCTTCCCCGGTTTCGT; HindIII restriction site is underlined) | oTN207 (TGTGGCCGCACTCGCGGAGGTACTGGAGGGCCTGGCGTGATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC) |

| oTN204 (TATTATTCTAGACCACCG TCAGCGAGTTGGCC; XbaI restriction site is underlined) | oTN208 (TGCTCTCCTTCGTCGGCCGTGCCGGTAGCGGCCGGGTCATGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC) | |

| rapK | oTN247 (GACTGTAAGCTTCACCTCACGAACGTCTTC; HindIII restriction site is underlined) | oTN253 (TTCTTCCTGGTACGCGCCAGGCAACGGCGGGGAAGGGTGATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC) |

| oTN252 (GAGTCCTCTAGAGATAGGTTTCCATCGGCAG; XbaI restriction site is underlined) | oTN254 (GCTCATCGGTGGTCCTTCCGGGTCAACTCGGCGGGGTCATGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC) |

The priming sites of the aac(3)IV disruption cassette are in boldface.

Intergeneric conjugation.

Deletion plasmids (pKOSi_ΔSIRANxxxx) (Fig. 1A) were electroporated into the methylation-deficient E. coli strain ET12567/pUZ8002. For this purpose, 800 μl of an overnight culture (2× TY medium supplemented with apramycin, kanamycin, and chloramphenicol) was used to inoculate 10 ml 2× tryptone-yeast extract (TY) medium. It was incubated at 30°C with 250 rpm to an A595 of ∼0.5. Antibiotics were removed by washing the cells twice with 1 ml of antibiotic-free TY medium at 4,000 rpm. Washed cells were resuspended in 250 μl of TY medium.

S. iranensis spores were harvested from 14-day-old oatmeal-agar plates with 20% (vol/vol) glycerol, washed once with TY medium, and resuspended in 1 ml of TY medium before the spores were counted. Per conjugation, 1 × 108 spores/ml were utilized and heat shocked for 10 min at 50°C to induce germination. Then, 250 μl of E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 cells was added, carefully mixed, and immediately plated onto either mannitol soya flour (MS) (containing 10 mM MgCl2) (24) or R6 agar (44) plates. To optimize the conjugation protocol for S. iranensis HM 35, different modifications were tested and combined to achieve higher efficiency. These modifications are further illustrated in Results. Conjugation efficiency was calculated as the ratio of the number of exconjugants per recipient cell, because we used fewer recipient cells (1 × 108 cells/ml) than donor cells (5 × 108 cells/ml) (45).

Evaluation of exconjugants by Southern blotting.

S. iranensis exconjugants were cultured in tryptone soy broth for 4 days at 28°C. Genomic DNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin microbial DNA kit (Macherey & Nagel) followed by Southern blotting using an 800- to 1,000-bp-long nonradioactively labeled DNA probe, as previously described (46). S. iranensis HM 35 genomic DNA was used as the control.

Rapamycin production.

S. rapamycinicus ATCC 29253 was precultured in seed medium for 48 h at 28°C, and S. iranensis strains were precultured in seed medium for 72 h at 28°C. Subsequently 1/10 of the preculture was cultured in YMM medium for 120 h at 28°C. Bacterial biomass was pelleted by centrifugation, and the pellets were extracted excessively with ethyl acetate. The extracts were filtered to remove the biomass, dehydrated with anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered again, and reduced to dryness with a rotary evaporator (Laborota 4000 efficient; Heidolph Instruments, Schwabach, Germany). The crude extracts were reconstituted in 1 ml methanol and filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size polytetrafluoroethylene filter (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). The samples were loaded onto an ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography (LC)–mass spectrometry system consisting of an UltiMate 3000 binary rapid-separation liquid chromatograph with photodiode array detector (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) and an LTQ XL linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) equipped with an electrospray ion source. The extracts (injection volume, 10 μl) were analyzed on a 150- by 4.6-mm Accucore reversed-phase (RP)-mass spectrometry column with a particle size of 2.6 μm (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Dreieich, Germany) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min with the following gradient: 0.1% (vol/vol) HCOOH-MeCN/0.1% (vol/vol) HCOOH-H2O 0/100, which was increased to 60/35 in 30 s and then to 100/0 in 1.5 min, held at 100/0 for 4 min, and reversed to 0/100 in 30 s, with detection at 190 to 400 nm. Rapamycin powder (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in methanol (final concentration, 100 μg/ml) and used as a standard.

l-Histidine degradation assay.

Tripartite petri dishes were prepared containing 8 ml of ISP9 agar (38) per third. To test histidine degradation, the medium was supplemented with (i) 1% (wt/vol) sucrose and 1% (wt/vol) ammonium sulfate, (ii) 1% (wt/vol) sucrose and 25 mM l-histidine, (iii) 25 mM l-histidine and 1% (wt/vol) ammonium sulfate, and (iv) 25 mM l-histidine. Each third of the tripartite petri dish was point inoculated with 5 × 105 spores of the S. iranensis ΔhutF mutant or the S. iranensis HM 35 wild-type strain. For the ΔhutF mutant strains, apramycin was added to the medium. The plates were incubated for 14 days at 28°C. The use of l-histidine as the sole carbon and/or nitrogen source was taken as an indication for l-histidine degradation.

RESULTS

To efficiently and reproducibly generate gene deletion mutants of the rapamycin-producing actinomycete S. iranensis HM 35, we optimized the procedure for conjugal plasmid transfer from the nonmethylating E. coli strain ET12567/pUZ8002 into S. iranensis HM 35. A schematic overview of the process is given in Fig. 2. The starting point was the generation of a plasmid that carried a chosen target gene sequence surrounded by flanking regions of approximately 2 kb each. This so-called deletion plasmid of the pKOSi_SIRANxxxx type (Fig. 1A) was introduced into E. coli BW25113/pIJ790. The helper plasmid pIJ790 carried the phage λ Red recombinase under the control of an inducible promoter (47) and the homologous recombination machinery genes bet and exo as well as gam, responsible for inhibiting host RecBCD exonuclease V. Gene rearrangement as a prerequisite for subsequent deletion was achieved by homologous recombination, with the disruption cassette carrying the apramycin resistance gene aac(3)IV as a selectable marker and the origin of transfer oriT (36). Recombined pKOSi derivatives (pKOSi_ΔSIRANxxxx) (Fig. 1A) were then transferred into the nonmethylating E. coli strain ET12567/pUZ8002 for conjugation with S. iranensis HM 35. The conjugation itself and the steps summarized below were identified as the most critical processes, requiring careful optimization.

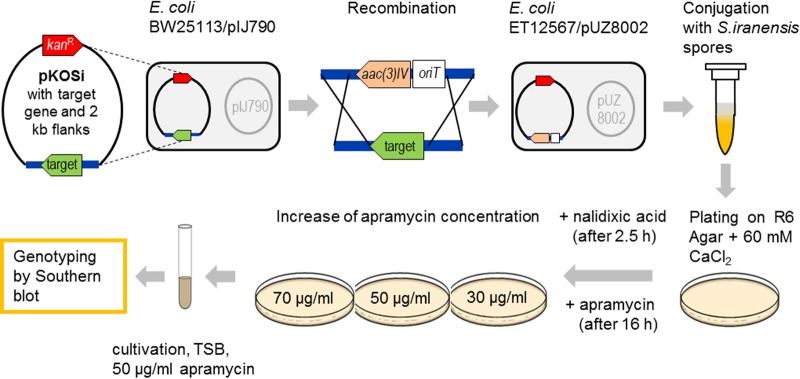

FIG 2.

Overview of the generation of S. iranensis gene deletion mutants via intergeneric conjugation. A PCR product consisting of a target gene and its 2-kb upstream and 2-kb downstream flanking regions was introduced into pKOSi (Fig. 1). The resulting pKOSi_SIRANxxxx plasmids were cloned via the shuttle host E. coli DH5α into E. coli BW25113/pIJ790, where gene rearrangement by homologous recombination with a disruption cassette occurred. The disruption cassette carried the apramycin resistance gene aac(3)IV and the origin of transfer gene oriT. Recombined plasmids were transferred into the nonmethylating E. coli strain ET12567/pUZ8002 for conjugation with S. iranensis HM 35. The conjugation mixture was plated on R6 agar containing 60 mM CaCl2. The growth of E. coli was inhibited by nalidixic acid. Obtained exconjugants were stepwise adapted to increased apramycin concentrations before genotyping by Southern blotting was performed to confirm successful genetic modification. TSB, tryptic soy broth.

Optimization of the conjugation protocol for S. iranensis HM 35.

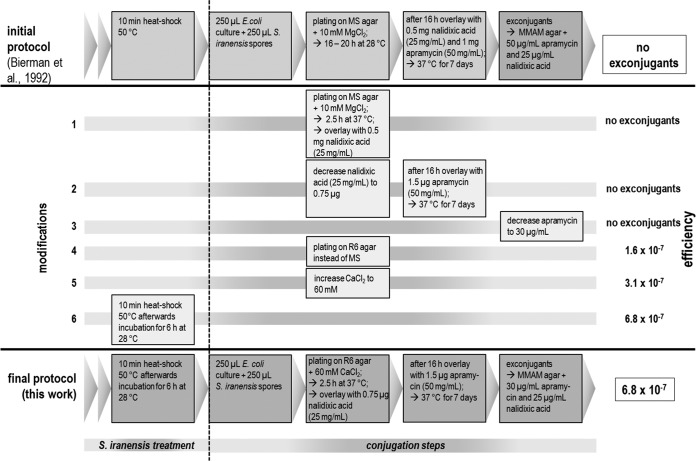

Because none of the known conjugation protocols (e.g., see reference 23) provided any exconjugants of the rapamycin producer S. iranensis HM 35, a systematic analysis and optimization of protocols were required. The final protocol summarizing all modifications and their consequences regarding conjugation efficiency in comparison to the starting version (23) is presented in Fig. 3. The first modification concerned the incubation time of the conjugation agar plates before they were overlaid with nalidixic acid. Overlaying with 0.5 mg of nalidixic acid was carried out after 2.5 h instead of the 16 h of incubation time at 37°C, followed by an overnight incubation at 37°C to support the loss of the pKOSi derivative. Release of the recombined plasmid was mediated by the temperature-sensitive replicon pSG5, which is functional only at temperatures below 34°C. Therefore, an early temperature shift to 37°C inhibited its replication, thereby promoting plasmid loss. Altogether, this provided an appropriate delivery system for homologous recombination between the plasmid-based sequence and the bacterial chromosome. The time scale for incubation with apramycin remained unchanged; i.e., agar plates were overlaid with 1 mg apramycin (50 mg/ml) after 16 h. Nevertheless, this modification step alone did not lead to exconjugant formation. Hence, the amounts of nalidixic acid and apramycin were decreased in the agar plates after conjugation had occurred at 37°C. Nalidixic acid (0.75 μg) and apramycin (only 1.5 μg) were added to select for growth of E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002. Again, none of these amendments improved conjugation frequency. Thus, in addition to identifying the described changes, we tested several media for their suitability for plating of the conjugation mixture of E. coli cells and Streptomyces spores in place of MS medium, as described in reference 23. Replacement of the MS medium with R6 agar containing 48 mM CaCl2 (a medium suitable for killing E. coli [16, 48]) gave stable exconjugants from each postconjugation plate.

FIG 3.

Development of an efficient conjugation protocol for the rapamycin producer S. iranensis HM 35. Stepwise modification of the basic protocol (23) led to increased conjugation efficiency and allowed reproducible generation of gene deletion mutants of S. iranensis HM 35. The highest conjugation efficiency (6.8 × 10−7 cells ml−1) was achieved when all modifications were applied in a single experiment.

The exconjugants obtained were patched onto MMAM agar plates with increased apramycin concentrations. Afterward, a PCR was carried out to distinguish between mutants with single or double crossovers (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Only the genotype of the double-crossover mutants was examined by Southern blotting. The conjugation frequency achieved was still relatively low, in the range of 1.6 × 10−7 (Fig. 4). Based on the study of reference 27, we increased the CaCl2 concentration in the R6 agar plates to 60 mM, which led to a conjugation frequency of 3.1 × 10−7. We further improved the conjugation frequency to 6.8 × 10−7 by inserting a 6-h germination time step at 28°C for the heat-shocked spores (27) prior to mixing them with the E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002 cells (Fig. 3). In summary, an efficient S. iranensis gene deletion strategy was achieved by applying all of the above modifications in a single experiment.

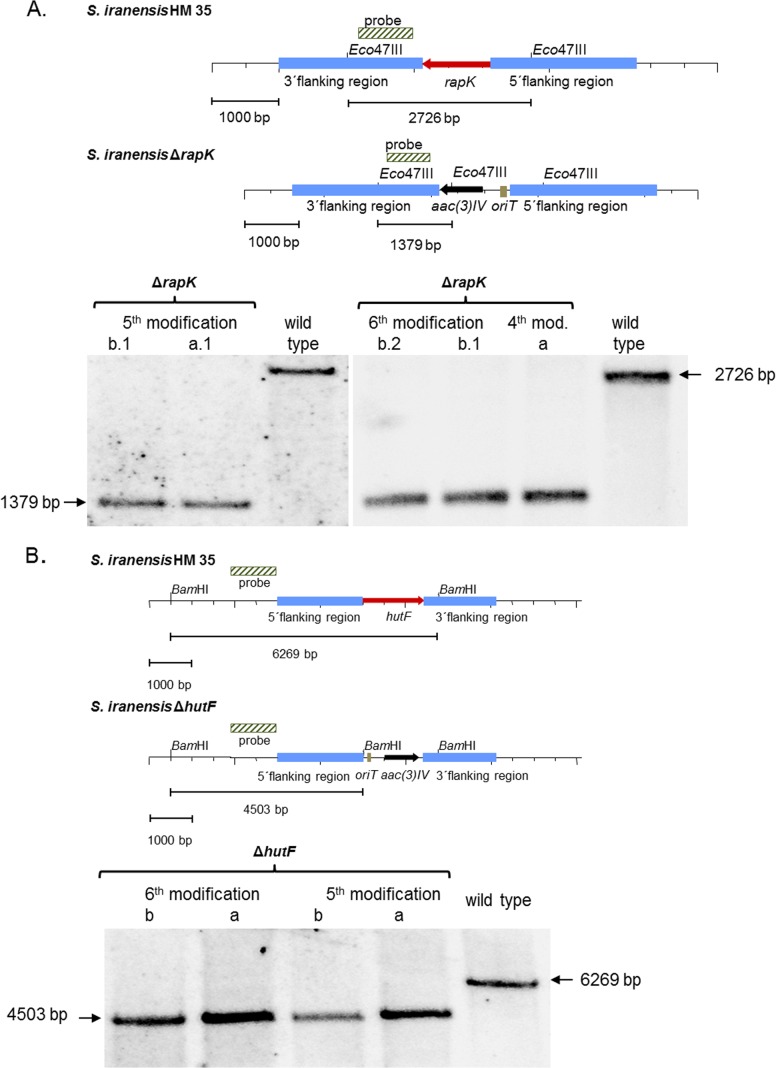

FIG 4.

Southern blot analysis. (A) S. iranensis rapK deletion mutant. The genomic locus was replaced by an apramycin resistance cassette. Genomic DNA was cut with Eco47III. An 801-bp PCR fragment encoding a rapK downstream sequence was used as the probe. ΔrapK deletion mutants (lanes 1, 2, 4 and 6) were characterized by a band of 1,379 bp; the typical 2,726-bp band of the wild type (lane 3 and 7) had disappeared. (B) S. iranensis hutF deletion mutant. The wild-type S. iranensis HM 35 strain was replaced at the locus of hutF by an apramycin resistance cassette. Genomic DNA was digested with BamHI. A 1,047-bp PCR fragment containing the upstream sequence of hutF was used as the probe. In ΔhutF deletion mutants (lanes 1 to 4), the characteristic 6,269-bp band of the wild type (lane 5) disappeared. Instead, a band of 4,503 bp represented successful gene replacement.

Verification of the conjugation protocol by deleting various genes.

To exemplify the final protocol, 10 S. iranensis genes were chosen for deletion: SIRAN1006, SIRAN1022, azlA, SIRAN1968, SIRAN4334, SIRAN4988, hutF, rapK, SIRAN8167, and SIRAN8652. In each case, exconjugants for knockouts of each target gene were obtained. The successful deletion of the indicated genes in each of the 10 generated S. iranensis deletion mutants was confirmed by Southern blotting, as shown for hutF and rapK (Fig. 4).

According to antibiotics and secondary-metabolite analysis shell (antiSMASH) (49, 50), the genes SIRAN1006, SIRAN1022, and azlA are members of a polyketide synthase (PKS) gene cluster, whereas SIRAN8652 belongs to a terpene synthase-containing cluster. SIRAN1986 represents a glycoside hydrolase and SIRAN4334 a monooxygenase. The gene SIRAN4988 codes for a putative serine/threonine phosphatase. hutF is annotated as formiminoglutamate deiminase, an enzyme involved in histidine catabolism (51, 52), whereas SIRAN8167 encodes a transmembrane efflux protein. Finally, we deleted rapK, which is part of the rapamycin biosynthesis gene cluster. The chorismatase RapK generates 4,5-dihydrocyclohex-1-ene-carboxylic acid (DHCHC) from chorismate. DHCHC serves as starter unit for the type I PKS encoded by rapA for rapamycin biosynthesis (16, 53). Two mutant strains, the ΔrapK and ΔhutF mutants, were further characterized.

Characterization of the ΔrapK and ΔhutF deletion mutants.

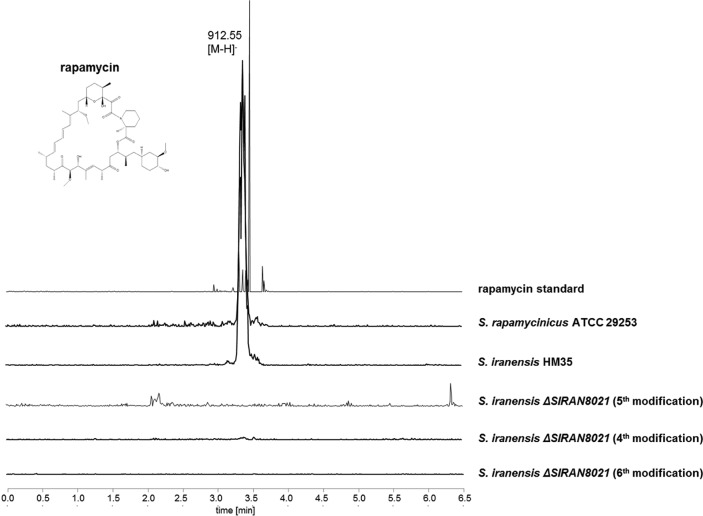

Like S. rapamycinicus, S. iranensis is able to produce the immunosuppressant rapamycin (5) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Consequently, a ΔrapK mutant should be incapable of rapamycin biosynthesis. As shown in Fig. 5, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis confirmed that the rapK deletion strain lost its ability to produce rapamycin. This result is in agreement with data obtained for the ΔrapK mutant of S. rapamycinicus (16, 53).

FIG 5.

Identification of rapamycin by LC-mass spectrometry. Extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) showing mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) of 912 to 914 [M-H], corresponding to rapamycin extracted from biomass. Unlike with the ΔrapK mutants obtained by each modification of the transformation protocol, a mass corresponding to rapamycin was detectable only in S. rapamycinicus ATCC 29253 and S. iranensis HM 35.

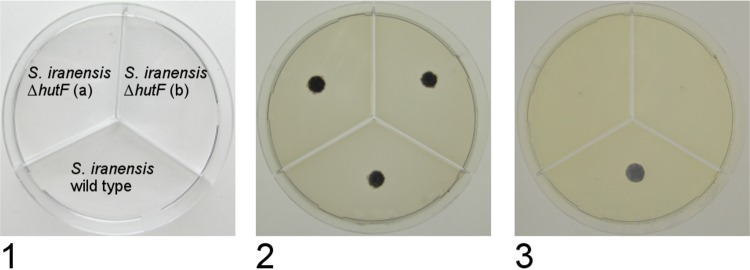

The gene hutF is annotated as formiminoglutamate deiminase, an enzyme involved in formation of N-formyl-l-glutamic acid from N-formininoglutamic acid. The former compound is further metabolized into l-glutamic acid that can be transferred via α-ketoglutaric acid into the citric acid cycle. In this process, two molecules of NH4+ are released. Therefore, growth of S. iranensis on l-histidine as the sole carbon and/or nitrogen source is possible. The ΔhutF mutants were expected to lack the ability to degrade l-histidine. Both ΔhutF mutants and the wild type were grown on ISP9 agar containing l-histidine as the sole carbon and/or nitrogen source to test l-histidine degradation. Figure 6 shows the growth of colonies of these mutants. On control agar, no difference between the mutant and the wild-type strain was observed. In contrast to the wild type, the mutant strain did not germinate when agar plates with l-histidine as the sole carbon and/or nitrogen source were used. This phenotype was indicative of the deletion of hutF. These successful gene deletions demonstrated the efficiency of the modified conjugation procedure for generation of gene knockouts in S. iranensis.

FIG 6.

Growth of S. iranensis HM 35 and ΔhutF mutants on ISP9 agar plates. Plates were inoculated with 5 × 105 spores and incubated for 14 days at 28°C. (1) Inoculation scheme; (2) plate supplemented with 1% (wt/vol) sucrose and 1% (wt/vol) ammonium sulfate (control); (3) plate supplemented with 1% (wt/vol) sucrose and 25 mM histidine. Growth on all other agar plates containing histidine as the sole C or N source was comparable to that on plate 3.

DISCUSSION

Streptomycetes produce an immense number of secondary metabolites, including compounds of medical interest. Among them is the valuable immunosuppressant rapamycin. Methods to genetically manipulate the genome of its alternative producers, e.g., by introducing or deleting selected genes, might open new avenues toward the production of novel rapamycin variants without the need for postfermentative chemical modification. Despite this importance, until this study, there had been no effective protocol for the generation of targeted gene deletions in rapamycin-producing Actinoplanes sp. N902-109 (18), for S. iranensis (17), or even for the established producer S. rapamycinicus (8); the working protocol (16) had not been systematically optimized. Two major challenges hinder gene deletions in actinomycetes: (i) the transfer of the vector carrying the foreign DNA into the cell and (ii) the site-specific integration of DNA into the chromosome. Typically, intergeneric conjugation is used as a means of gene transfer into streptomycetes to accomplish the first step (22, 54, 55). Intergeneric conjugation has already been successfully applied to species of various genera, e.g., Streptomyces, Actinomadura, Amycolatopsis, Arthrobacter, Micromonospora, Nocardia, Rhodococcus, Kitasatospora, and Saccharopolyspora (56–60). The advantage of this strategy is that it allows for the design and construction of recombinant plasmids in E. coli prior to transfer to the recipient of interest. The second step, the integration of recombinant DNA into the genome, is often mediated by the integration vector pSET152 (23) or derivatives thereof that contain the attachment site (attP) and the integrase (int) function of the temperate phage ϕC31. pSET152 derivatives undergo site-specific integration into the attB sites of the Streptomyces chromosome (61). However, even this was challenging with S. rapamycinicus and S. iranensis and not feasible with the standard conjugation protocol (23). Only by applying the mentioned modifications could pSET152 be reproducibly inserted into both species (data not shown).

While the insertion of pSET152 proves that the introduction of recombinant gene cassettes into a given species is possible, it also means that pSET152 derivatives are not suitable to achieve targeted gene deletions. To address this problem, diverse solutions exist. The basic required step relies on gene rearrangement by homologous recombination, typically between the gene to be deleted and a cassette consisting of a selection marker and an origin of transfer. As already mentioned, the appropriate cassette can easily be generated in E. coli. An elegant way to perform such gene rearrangement consists of λ Red-mediated PCR targeting (36). Therefore, we designed a pKOSi-based deletion vector that, besides carrying the temperature-sensitive replicon pSG5 (39, 40), carries a cassette encoding the kanamycin resistance gene kan and 2-kb flanking regions of the gene to be deleted. The apramycin resistance gene aac(3)IV, the origin of transfer gene oriT, and twin Flp recognition target (FRT) sequences were amplified from pIJ773 containing arms with 39 nt of homology to the gene of interest.

Subsequently, the PCR product was electroporated into E. coli BW25113/pIJ790. This strain expresses the genes encoding the λ Red recombination machinery, thus promoting homologous recombination between the genomic region and the homology arms of the PCR product and generating the final plasmid for intergeneric conjugation with S. iranensis. The advantage of this method is its rapidity, compared to step-by-step cloning of the resistance cassette, the oriT gene, and the FRT sequences. Theoretically, the described procedure provides a promising approach for the ultimate site-specific homologous recombination between this cassette and the bacterial chromosome to generate targeted gene knockouts. However, in practice, it does not work properly for every Streptomyces species, and further optimization is often required to successfully conjugate E. coli with refractory species (62–65). Various species-dependent parameters which strongly affected the transformation efficiency were identified. Sun et al. (64) found that the ratio of donor to recipient cell numbers was the most influential factor for conjugation into Streptomyces noursei. Also, for Streptomyces diastatochromogenes, the number of spores and their use instead of mycelia, in combination with a cultivation step at 30°C subsequent to the heat shock, were found to be the most important factors (65). In contrast, Du et al. (63) achieved the highest conjugation efficiencies for Streptomyces lincolnensis by using mycelia rather than spores as recipients and by addition of 10.3% sucrose to the SM medium (63). Due to the fact that several streptomycetes degrade methylated DNA, a nonmethylating E. coli strain can be preferable as the DNA donor in intergeneric conjugation (55). However, when an effective gene transfer system for Streptomyces ipomoeae, the causative agent of soil rot disease of sweet potatoes, was engineered, plasmids could be introduced and maintained with approximately equivalent frequencies from either methyl-proficient or methyl-deficient E. coli donors (66).

The parameters that determine successful intergeneric conjugation include the following: (i) the type of cells, (ii) the media used for sporulation and conjugation protocols, (iii) the duration of the incubation steps, and (iv) the temperature of the incubation steps. All of these factors were important when we transferred a basic conjugation protocol into an effective conjugation system for rapamycin-producing S. iranensis. Modifications of each of the parameters were found to be required. The protocol developed for deletion mutant generation was applied to S. iranensis spores. Screening of media indicated that R6 agar instead of MS agar in the conjugation agar plates is a prerequisite for the growth of exconjugants. We also changed the time of addition and amount of nalidixic acid and apramycin. By significantly decreasing the concentrations of both compounds, an even higher number of transconjugants was obtained. Based on data from Wang and Jin (27), we changed the CaCl2 concentration in the conjugation agar plates and found 60 mM to be optimal. Another important step included 6 h of incubation directly after the heat shock. By combining all of the described modifications in a single experiment, we achieved a conjugation efficiency of 6.8 × 10−7 transconjugants per recipient CFU. This is still low compared to those obtained for Streptomyces coelicolor (1.1 × 10−1) when the methylation-deficient donor E. coli ET12567/pUB307 was applied for the first time (55) or compared to those achieved for S. lincolnensis mycelia exconjugants (2.8 × 10−5) when regenerated on solid MS medium containing 10.3% sucrose (63).

Conjugation efficiencies have proved to be highly varied, depending on the Streptomyces species and on the optimization steps used. For S. peucetius and Streptomyces sp. strain C5 conjugation efficiencies of 1.5 × 10−4 per recipient cell or 1.1 × 10−5 exconjugants per recipient spore, respectively, were calculated (67). Phornphisutthimas et al. (62) obtained high efficiencies of conjugation (10−2 to 10−3) for S. rimosus with a procedure based on heat treatment of the spores at 40°C for 10 min prior to their being mixed with E. coli ET12567(pUZ8002/pIJ8600). In that study, tryptic soy agar medium containing 10 mmol/liter MgCl2 was the preferred medium for conjugation. Finally, Sun et al. (64) obtained 8 × 10−3 exconjugants per recipient when spores were heat shocked at 50°C for 10 min, mixed with E. coli ET12567/pUZ8002/pSET152 in the ratio of 1:100, plated on 2CMY medium (71) containing 40 mmol/liter MgCl2, and incubated at 30°C for 22 h.

Taken together, the methods and strategies applied to develop and optimize intergeneric conjugation for a given species are as diverse as the species themselves. The present protocol focuses on S. iranensis, aiming to generate mutants producing nonnative rapamycin variants, to study the regulation of rapamycin biosynthesis in this species, and also to make the species amenable to the discovery of novel secondary metabolites by genetic engineering. To our knowledge, the modified protocol is the first successful directed gene deletion protocol for this species.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We warmly thank Christian Hertweck (Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology [HKI], Jena, Germany) for insightful ideas and help as well as Christina Täumer and Karin Burmeister for excellent technical assistance. Plasmid pTNM was kindly provided by Andriy Luzhetskyy (Saarland University, Germany).

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG)-funded Collaborative Research Center 1127 ChemBioSys, the European Union (EU)-funded Marie Curie International Training Network (ITN) Quantfung, and the Jena School for Microbial Communication (JSMC), a DFG Excellence Graduate School.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00371-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jones D, Metzger HJ, Schatz A, Waksman SA. 1944. Control of Gram-negative bacteria in experimental animals by streptomycin. Science 100:103–105. doi: 10.1126/science.100.2588.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopwood DA. 2007. Streptomyces in nature and medicine: the antibiotic makers. Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentley SD, Chater KF, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Challis GL, Thomson NR, James KD, Harris DE, Quail MA, Kieser H, Harper D, Bateman A, Brown S, Chandra G, Chen CW, Collins M, Cronin A, Fraser A, Goble A, Hidalgo J, Hornsby T, Howarth S, Huang CH, Kieser T, Larke L, Murphy L, Oliver K, O'Neil S, Rabbinowitsch E, Rajandream MA, Rutherford K, Rutter S, Seeger K, Saunders D, Sharp S, Squares R, Squares S, Taylor K, Warren T, Wietzorrek A, Woodward J, Barrell BG, Parkhill J, Hopwood DA. 2002. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 417:141–147. doi: 10.1038/417141a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baranasic D, Gacesa R, Starcevic A, Zucko J, Blazic M, Horvat M, Gjuracic K, Fujs S, Hranueli D, Kosec G, Cullum J, Petkovic H. 2013. Draft genome sequence of Streptomyces rapamycinicus strain NRRL 5491, the producer of the immunosuppressant rapamycin. Genome Announc 1(4):e00581-13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00581-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horn F, Schroeckh V, Netzker T, Guthke R, Brakhage AA, Linde J. 2014. Draft genome sequence of Streptomyces iranensis. Genome Announc 2(4):e00616-14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00616-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trevillian P. 2006. Immunosuppressants: clinical applications. Aust Prescr 29:102–108. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2006.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vezina C, Kudelski A, Sehgal SN. 1975. Rapamycin (AY-22,989), a new antifungal antibiotic. I: taxonomy of the producing streptomycete and isolation of the active principle. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 28:721–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar Y, Goodfellow M. 2008. Five new members of the Streptomyces violaceusniger 16S rRNA gene clade: Streptomyces castelarensis sp. nov., comb. nov., Streptomyces himastatinicus sp. nov., Streptomyces mordarskii sp. nov., Streptomyces rapamycinicus sp. nov., and Streptomyces ruanii sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 58:1369–1378. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwecke T, Aparicio JF, Molnár I, König A, Khaw LE, Haydock SF, Oliynyk M, Caffrey P, Cortés J, Lester JB. 1995. The biosynthetic gene cluster for the polyketide immunosuppressant rapamycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:7839–7843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.König A, Schwecke T, Molnár I, Böhm GA, Lowden PAS, Staunton J, Leadlay PF. 1997. The pipecolate-incorporating enzyme for the biosynthesis of the immunosuppressant rapamycin: nucleotide sequence analysis, disruption and heterologous expression of Rap P from Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Eur J Biochem 247:526–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khaw LE, Böhm GA, Metcalfe S, Staunton J, Leadlay PF. 1998. Mutational biosynthesis of novel rapamycins by a strain of Streptomyces hygroscopicus NRRL 5491 disrupted in rapL, encoding a putative lysine cyclodeaminase. J Bacteriol 180:809–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowden PAS, Böhm GA, Metcalfe S, Staunton J, Leadlay PF. 2004. New rapamycin derivatives by precursor-directed biosynthesis. Chembiochem 5:535–538. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregory MA, Gaisser S, Lill RE, Hong H, Sheridan RM, Wilkinson B, Petkovic H, Weston AJ, Carletti I, Lee H-L, Staunton J, Leadlay PF. 2004. Isolation and characterization of prerapamycin, the first macrocyclic intermediate in the biosynthesis of the immunosuppressant rapamycin by S. hygroscopicus. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 43:2551–2553. doi: 10.1002/anie.200453764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gregory MA, Hong H, Lill RE, Gaisser S, Petkovic H, Low L, Sheehan LS, Carletti I, Ready SJ, Ward MJ, Kaja AL, Weston AJ, Challis IR, Leadlay PF, Martin CJ, Wilkinson B, Sheridan RM. 2006. Rapamycin biosynthesis: elucidation of gene product function. Org Biomol Chem 4:3565–3568. doi: 10.1039/b608813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregory MA, Petkovic H, Lill RE, Moss SJ, Wilkinson B, Gaisser S, Leadlay PF, Sheridan RM. 2005. Mutasynthesis of rapamycin analogues through the manipulation of a gene governing starter unit biosynthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 44:4757–4760. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendrew SG, Petkovic H, Gaisser S, Ready SJ, Gregory MA, Coates NJ, Nur EAM, Warneck T, Suthar D, Foster TA, McDonald L, Schlingman G, Koehn FE, Skotnicki JS, Carter GT, Moss SJ, Zhang MQ, Martin CJ, Sheridan RM, Wilkinson B. 2013. Recombinant strains for the enhanced production of bioengineered rapalogs. Metab Eng 15:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamedi J, Mohammadipanah F, Klenk HP, Potter G, Schumann P, Sproer C, von Jan M, Kroppenstedt RM. 2010. Streptomyces iranensis sp. nov., isolated from soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 60:1504–1509. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.015339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishida H, Sakakibara T, Aoki F, Saito T, Ichikawa K, Inagaki T, Kojima Y, Yamauchi Y, Huang LH, Guadliana MA, Kaneko T, Kojima N. 1995. Generation of novel rapamycin structures by microbial manipulations. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 48:657–666. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.48.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bibb MJ, Ward JM, Hopwood DA. 1978. Transformation of plasmid DNA into Streptomyces at high frequency. Nature 274:398–400. doi: 10.1038/274398a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pigac J, Schrempf H. 1995. A simple and rapid method of transformation of Streptomyces rimosus R6 and other Streptomycetes by electroporation. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:352–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tyurin M, Starodubtseva L, Kudryavtseva H, Voeykova T, Livshits V. 1995. Electrotransformation of germinating spores of Streptomyces spp. Biotechnol Tech 9:737–740. doi: 10.1007/BF00159240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazodier P, Petter R, Thompson C. 1989. Intergeneric conjugation between Escherichia coli and Streptomyces species. J Bacteriol 171:3583–3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bierman M, Logan R, O'Brien K, Seno ET, Nagaraja Rao R, Schoner BE. 1992. Plasmid cloning vectors for the conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces spp. Gene 116:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA. 2000. Practical Streptomyes genetics. John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nybo SE, Shepherd MD, Bosserman MA, Rohr J. 2005. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces species. Curr Protoc Microbiol 19:10E.3.1–10E.3.26. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc10e03s19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brnáková Z, Farkasovská J, Rusnáková A, Godány A. 2008. Formation of Streptomyces protoplasts during cultivation in liquid media with lytic enzyme. Nova Biotechnol 8:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X-K, Jin J-L. 2014. Crucial factor for increasing the conjugation frequency in Streptomyces netropsis SD-07 and other strains. FEMS Microbiol Lett 357:99–103. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lomovskaya N, Fonstein L, Ruan X, Stassi D, Katz L, Hutchinson CR. 1997. Gene disruption and replacement in the rapamycin-producing Streptomyces hygroscopicus strain ATCC 29253. Microbiology 143(pt 3):875–883. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-3-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung L, Liu L, Patel S, Carney JR, Reeves CD. 2001. Deletion of rapQONML from the rapamycin gene cluster of Streptomyces hygroscopicus gives production of the 16-O-desmethyl-27-desmethoxy analog. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 54:250–256. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.54.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung W, Yoo Y, Park J, Park S, Han A, Ban Y, Kim E, Kim E, Yoon Y. 2011. A combined approach of classical mutagenesis and rational metabolic engineering improves rapamycin biosynthesis and provides insights into methylmalonyl-CoA precursor supply pathway in Streptomyces hygroscopicus ATCC 29253. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 91:1389–1397. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3348-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu X, Zhang W, Chen X, Wu H, Duan Y, Xu Z. 2010. Generation of high rapamycin producing strain via rational metabolic pathway-based mutagenesis and further titer improvement with fed-batch bioprocess optimization. Biotechnol Bioeng 107:506–515. doi: 10.1002/bit.22819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen X, Wei P, Fan L, Yang D, Zhu X, Shen W, Xu Z, Cen P. 2009. Generation of high-yield rapamycin-producing strains through protoplasts-related techniques. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 83:507–512. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-1918-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ritacco FV, Graziani EI, Summers MY, Zabriskie TM, Yu K, Bernan VS, Carter GT, Greenstein M. 2005. Production of novel rapamycin analogs by precursor-directed biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:1971–1976. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.4.1971-1976.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoo YJ, Hwang J-Y, Shin H-L, Cui H, Lee J, Yoon YJ. 2014. Characterization of negative regulatory genes for the biosynthesis of rapamycin in Streptomyces rapamycinicus and its application for improved production. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 42:125–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paget MSB, Chamberlin L, Atrih A, Foster SJ, Buttner MJ. 1999. Evidence that the extracytoplasmic function sigma factor σE is required for normal cell wall structure in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). J Bacteriol 181:204–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gust B, Chandra G, Jakimowicz D, Yuqing T, Bruton CJ, Chater KF. 2004. Lambda red-mediated genetic manipulation of antibiotic-producing Streptomyces. Adv Appl Microbiol 54:107–128. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(04)54004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shirling EB, Gottlieb D. 1966. Methods for characterization of Streptomyces species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 16:313–340. doi: 10.1099/00207713-16-3-313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muth G, Wohlleben W, Puhler A. 1988. The minimal replicon of the Streptomyces ghanaensis plasmid pSG5 identified by subcloning and Tn5 mutagenesis. Mol Gen Genet 211:424–429. doi: 10.1007/BF00425695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muth G, Nußbaumer B, Wohlleben W, Pühler A. 1989. A vector system with temperature-sensitive replication for gene disruption and mutational cloning in streptomycetes. Mol Gen Genet 219:341–348. doi: 10.1007/BF00259605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fürste JP, Pansegrau W, Ziegelin G, Kröger M, Lanka E. 1989. Conjugative transfer of promiscuous IncP plasmids: interaction of plasmid-encoded products with the transfer origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86:1771–1775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.6.1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petzke L, Luzhetskyy A. 2009. In vivo Tn5-based transposon mutagenesis of Streptomycetes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 83:979–986. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2047-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Som T, Tomizawa J-I. 1982. Origin of replication of Escherichia coli plasmid RSF 1030. Mol Gen Genet 187:375–383. doi: 10.1007/BF00332615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Illing GT, Normansell ID, Peberdy JF. 1989. Protoplast isolation and regeneration in Streptomyces clavuligerus. J Gen Microbiol 135:2289–2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phornphisutthimas S, Thamchaipenet A, Panijpan B. 2007. Conjugation in Escherichia coli. Biochem Mol Biol Educ 35:440–445. doi: 10.1002/bmb.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schroeckh V, Scherlach K, Nützmann HW, Shelest E, Schmidt-Heck W, Schuemann J, Martin K, Hertweck C, Brakhage AA. 2009. Intimate bacterial-fungal interaction triggers biosynthesis of archetypal polyketides in Aspergillus nidulans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:14558–14563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901870106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gust B, Challis GL, Fowler K, Kieser T, Chater KF. 2003. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:1541–1546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337542100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moss SJ, Stanley-Smith AE, Schell U, Coates NJ, Foster TA, Gaisser S, Gregory MA, Martin CJ, Nur-e-Alam M, Piraee M, Radzom M, Suthar D, Thexton DG, Warneck TD, Zhang M-Q, Wilkinson B. 2013. Novel FK506 and FK520 analogues via mutasynthesis: mutasynthon scope and product characteristics. Medchemcomm 4:324–331. doi: 10.1039/C2MD20266B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blin K, Medema MH, Kazempour D, Fischbach MA, Breitling R, Takano E, Weber T. 2013. antiSMASH 2.0: a versatile platform for genome mining of secondary metabolite producers. Nucleic Acids Res 41:W204–W212. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weber T, Blin K, Duddela S, Krug D, Kim HU, Bruccoleri R, Lee SY, Fischbach MA, Müller R, Wohlleben W, Breitling R, Takano E, Medema MH. 2015. antiSMASH 3.0: a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res 43:W237–W243. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schomburg D, Salzmann M. 1991. Formiminoglutamate deiminase, p 969–971. In Schomburg D, Salzmann M (ed), Enzyme handbook 4. Springer, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Magasanik B, Bowser HR. 1955. The degradation of histidine by Aerobacter aerogenes. J Biol Chem 213:571–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andexer JN, Kendrew SG, Nur-e-Alam M, Lazos O, Foster TA, Zimmermann A-S, Warneck TD, Suthar D, Coates NJ, Koehn FE, Skotnicki JS, Carter GT, Gregory MA, Martin CJ, Moss SJ, Leadlay PF, Wilkinson B. 2011. Biosynthesis of the immunosuppressants FK506, FK520, and rapamycin involves a previously undescribed family of enzymes acting on chorismate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:4776–4781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015773108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matsushima P, Baltz RH. 1996. A gene cloning system for Streptomyces toyocaensis. Microbiology 142:261–267. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-2-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Flett F, Mersinias V, Smith CP. 1997. High-efficiency intergeneric conjugal transfer of plasmid DNA from Escherichia coli to methyl DNA-restricting streptomycetes. FEMS Microbiol Lett 155:223–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb13882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsushima P, Broughton MC, Turner JR, Baltz RH. 1994. Conjugal transfer of cosmid DNA from Escherichia coli to Saccharopolyspora spinosa: effects of chromosomal insertions on macrolide A83543 production. Gene 146:39–45. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90831-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voeykova T, Emelyanova L, Tabakov V, Mkrtumyan N. 1998. Transfer of plasmid pTO1 from Escherichia coli to various representatives of the order Actinomycetales by intergeneric conjugation. FEMS Microbiol Lett 162:47–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stegmann E, Pelzer S, Wilken K, Wohlleben W. 2001. Development of three different gene cloning systems for genetic investigation of the new species Amycolatopsis japonicum MG417-CF17, the ethylenediaminedisuccinic acid producer. J Biotechnol 92:195–204. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(01)00360-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shigeru K, Bibb MJ, Nihira T, Yamada Y. 2000. Conjugal transfer of plasmid DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces lavendulae FRI-5. J Microbiol Biotechnol 10:535–538. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Choi S-U, Lee C-K, Hwang Y-I, Kinoshita H, Nihira T. 2004. Intergeneric conjugal transfer of plasmid DNA from Escherichia coli to Kitasatospora setae, a bafilomycin B1 producer. Arch Microbiol 181:294–298. doi: 10.1007/s00203-004-0654-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuhstoss S, Rao RN. 1991. Analysis of the integration function of the streptomycete bacteriophage φC31. J Mol Biol 222:897–908. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90584-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Phornphisutthimas S, Sudtachat N, Bunyoo C, Chotewutmontri P, Panijpan B, Thamchaipenet A. 2010. Development of an intergeneric conjugal transfer system for rimocidin-producing Streptomyces rimosus. Lett Appl Microbiol 50:530–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Du L, Liu R-H, Ying L, Zhao G-R. 2012. An efficient intergeneric conjugation of DNA from Escherichia coli to mycelia of the lincomycin-producer Streptomyces lincolnensis. Int J Mol Sci 13:4797–4806. doi: 10.3390/ijms13044797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun F-H, Luo D, Shu D, Zhong J, Tan H. 2014. Development of an intergeneric conjugal transfer system for xinaomycins-producing Streptomyces noursei Xinao-4. Int J Mol Sci 15:12217–12230. doi: 10.3390/ijms150712217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ma Z, Liu J, Bechthold A, Tao L, Shentu X, Bian Y, Yu X. 2014. Development of intergeneric conjugal gene transfer system in Streptomyces diastatochromogenes 1628 and its application for improvement of toyocamycin production. Curr Microbiol 68:180–185. doi: 10.1007/s00284-013-0461-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guan D, Pettis GS. 2009. Intergeneric conjugal gene transfer from Escherichia coli to the sweet potato pathogen Streptomyces ipomoeae. Lett Appl Microbiol 49:67–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2009.02619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Paranthaman S, Dharmalingam K. 2003. Intergeneric conjugation in Streptomyces peucetius and Streptomyces sp. strain C5: chromosomal integration and expression of recombinant plasmids carrying the chiC gene. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:84–91. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.1.84-91.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hanahan D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol 166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.MacNeil DJ, Gewain KM, Ruby CL, Dezeny G, Gibbons PH, MacNeil T. 1992. Analysis of Streptomyces avermitilis genes required for avermectin biosynthesis utilizing a novel integration vector. Gene 111:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90603-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xiao Y, Li SM, Ma L, Zhang GY, Ju JH, Zhang CS. 2010. Genetic manipulation system for tiacumicin producer Dactylosporangium aurantiacum NRRL 18085. Acta Microbiol Sin 50:1014–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.