ABSTRACT

A structurally novel chitinase, Tc-ChiD, was identified from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus chitonophagus, which can grow on chitin as the sole organic carbon source. The gene encoding Tc-ChiD contains regions corresponding to a signal sequence, two chitin-binding domains, and a putative catalytic domain. This catalytic domain shows no similarity with previously characterized chitinases but resembles an uncharacterized protein found in the mesophilic anaerobic bacterium Clostridium botulinum. Two recombinant Tc-ChiD proteins were produced in Escherichia coli, one without the signal sequence [Tc-ChiD(ΔS)] and the other corresponding only to the putative catalytic domain [Tc-ChiD(ΔBD)]. Enzyme assays using N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) oligomers indicated that both proteins hydrolyze GlcNAc oligomers longer than (GlcNAc)4. Chitinase assays using colloidal chitin suggested that Tc-ChiD is an exo-type chitinase that releases (GlcNAc)2 or (GlcNAc)3. Analysis with GlcNAc oligomers modified with p-nitrophenol suggested that Tc-ChiD recognizes the reducing end of chitin chains. While Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) displayed a higher initial velocity than that of Tc-ChiD(ΔS), we found that the presence of the two chitin-binding domains significantly enhanced the thermostability of the catalytic domain. In T. chitonophagus, another chitinase ortholog that is similar to the Thermococcus kodakarensis chitinase ChiA is present and can degrade chitin from the nonreducing ends. Therefore, the presence of multiple chitinases in T. chitonophagus with different modes of cleavage may contribute to its unique ability to efficiently degrade chitin.

IMPORTANCE A structurally novel chitinase, Tc-ChiD, was identified from Thermococcus chitonophagus, a hyperthermophilic archaeon. The protein contains a signal peptide for secretion, two chitin-binding domains, and a catalytic domain that shows no similarity with previously characterized chitinases. Tc-ChiD thus represents a new family of chitinases. Tc-ChiD is an exo-type chitinase that recognizes the reducing end of chitin chains and releases (GlcNAc)2 or (GlcNAc)3. As a thermostable chitinase that recognizes the reducing end of chitin chains was not previously known, Tc-ChiD may be useful in a wide range of enzyme-based technologies to degrade and utilize chitin.

INTRODUCTION

Chitin is a β-1,4-linked insoluble linear polymer of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and is the main component of the exoskeleton of crustaceans and insects, as well as the cell walls of fungi. Chitin is the second most abundant natural polysaccharide after cellulose, and its annual formation rate is in the order of 1010 to 1011 tons (1). At present, the majority of chitin remains unused, and thus the development of effective methods to convert chitin into useful biomaterials and/or bioenergy is important to maintain our supplies of edible polysaccharides, such as starch.

Chitinases are enzymes responsible for the hydrolysis of chitin polymer, and they produce GlcNAc and/or its oligomers as products. Chitinases are found in a variety of organisms, including bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses, animals, and plants (1, 2). Chitinases from a number of bacteria have been studied in detail. Members of the Actinomycetes usually contain several chitinase genes, for example, Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) contains 11 GH18 family chitinase genes and two GH19 chitinase genes (3, 4). These chitinases include enzymes with different substrate specificities that are active toward various states of chitin (4). The GH19 chitinases from Actinomycetes exhibit antifungal activity and have been suggested to play a role in the restriction of fungal growth (4–6). The chitinolytic machinery of Serratia marcescens, a member of the order Enterobacteriales, has also been extensively studied, leading to the identification of multiple chitinases with different catalytic properties (7).

In general, the GH18 family chitinases are the largest in number (>8,000 in the CAZy database), and >400 enzymes have been characterized. GH19 family chitinases also form a large group and are found almost exclusively in Bacteria and Eucarya (mainly in plants) (8–12). Although the numbers are small, chitinases from other families have also been characterized. A GH23 protein encoded by a goose-type (G-type) lysozyme gene from a moderately thermophilic bacterium, Ralstonia sp. strain A-471, displays chitinolytic activity but not lysozyme activity (13, 14). A GH48 protein (APAP I) from the leaf beetle, Gastrophysa atrocyanea, also exhibits chitinase activity (15), while most other members in this family display hydrolytic activity for cellulose or its derivatives. There is also a report on a structurally novel type chitinase from the hyperthermophilic acidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus tokodaii (16), which has not yet been classified to any of the glycosyl hydrolase (GH) families.

The presence of more than a dozen chitinases from thermophiles has been reported, but only a limited number are found in hyperthermophiles. The chitinase first characterized from a hyperthermophile is the chitinase ChiA from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis (Tk-ChiA) (17). Tk-ChiA contains dual catalytic domains, both belonging to the GH18 family, and enzymatic analyses on full-length and truncated proteins indicated that the amino-terminal domain catalyzes an exo-type cleavage of the chitin chain, while the carboxy-terminal domain catalyzes an endo-type cleavage. The presence of two catalytic domains in Tk-ChiA with different specificities results in a synergistic effect on chitin degradation (17, 18). Tk-ChiA also contains three chitin-binding domains (ChBDs). The ChBD located at the amino terminus belongs to family 5 of the carbohydrate-binding module (CBM), while the other two domains of the CBM family 2 are located consecutively between the two catalytic domains. In the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus, two putative chitinase genes located next to each other on the genome were expressed in Escherichia coli, and their products (ChiA and ChiB from P. furiosus [Pf-ChiA and Pf-ChiB, respectively]) were found to display chitinase activity (19, 20). The catalytic domains of Pf-ChiA and Pf-ChiB are structurally and enzymatically orthologous to the amino- and carboxy-terminal catalytic domains of Tk-ChiA, respectively. It has been pointed out that the Pf-ChiA and Pf-ChiB genes are separated due to a single-base insertion in the locus, and that its deletion would lead to a gene structurally similar to that of Tk-chiA. Deletion of the base from the P. furiosus genome resulted in a strain that grew well on chitin (21).

Thermococcus chitonophagus is a unique hyperthermophilic archaeon isolated from an enriched culture of a sample from a hydrothermal vent site using medium containing chitin as the sole carbon and energy source (22). In T. chitonophagus, the presence of three proteins showing chitinolytic activity has been suggested. A protein with an apparent molecular mass of 70 kDa (Chi70) was purified from the cell membrane fraction. Chi70 exhibits an endo-chitinase activity, with N,N′-diacetylchitobiose [(GlcNAc)2] being the major hydrolysis product (23). Another enzyme with an apparent molecular mass of 50 kDa, Chi50, was partially purified from the culture supernatant and exhibits an exo-chitinase activity that exclusively produces (GlcNAc)2 from colloidal chitin (23). In addition, activity staining on a gel after electrophoresis of whole-cell extracts of T. chitonophagus indicated the presence of a 90-kDa protein, designated Chi90, that can hydrolyze 4-methylumbelliferyl N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminide (chitobiase activity) (23). A portion of the Chi70 gene has been identified (24), but the complete primary structures of these enzymes are still unknown.

In this study, we have identified and characterized a structurally novel chitinase from T. chitonophagus. The enzyme, Tc-ChiD, does not exhibit sequence similarity to any protein that has been demonstrated to exhibit chitinase activity. The enzymatic properties of the protein suggest that Tc-ChiD recognizes the reducing end of the chitin chain and releases (GlcNAc)2 as the major product.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

T. chitonophagus DSM 10152 was obtained from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ). Cultivation of T. chitonophagus was performed basically with the same method applied for T. kodakarensis (25). T. chitonophagus was grown under anaerobic conditions at 85°C in a nutrient-rich medium (ASW-YT) supplemented with elemental sulfur (S0). ASW-YT medium was composed of 0.8× artificial seawater (0.8× ASW), 5.0 g liter−1 yeast extract, 5.0 g liter−1 tryptone, and 0.8 mg liter−1 of resazurin (as a redox indicator). After autoclaving, Na2S solution was added to the medium until it became colorless, and S0 (2.0 g liter−1) was added prior to inoculation.

Escherichia coli DH5α and E. coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL (Stratagene) were used for plasmid construction and heterologous gene expression, respectively. E. coli cells were cultivated at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium containing ampicillin (100 μg liter−1). Unless mentioned otherwise, all chemicals were purchased from Wako Pure Chemicals (Osaka, Japan) or Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan).

Genomic DNA extraction and draft genome analysis of T. chitonophagus.

T. chitonophagus was cultivated in ASW-YT-S0 medium at 85°C for 12 h. The genomic DNA was extracted using the NucleoBond AXG kit (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany). Draft genome analysis was performed at TaKaRa Bio, Inc. (Otsu, Japan) using the HiSeq system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Construction of expression plasmids of Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD).

Two recombinant Tc-ChiD proteins, Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD), were heterologously produced in E. coli. Tc-ChiD(ΔS) (residues 26 to 805) contains the entire Tc-ChiD protein except for the putative signal sequence. Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) (residues 321 to 805) contains only the predicted catalytic region. The expression plasmids were constructed as follows. Using the genomic DNA of T. chitonophagus as the template, two primer sets (Tc-nChi-f/Tc-nChi-r and Tc-nChi-dBD-f/Tc-nChi-r) were used to amplify the regions corresponding to Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD), respectively. The amplified fragments were digested with NdeI and SalI and inserted into the respective sites of pET21a (Stratagene). The resulting plasmids were designated pET-Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and pET-Tc-ChiD(ΔBD), respectively.

Preparation of recombinant Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD).

E. coli cells harboring pET-Tc-ChiD(ΔS) or pET-Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) were cultivated at 37°C in LB medium until the optical density at 660 nm reached ∼0.3. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to a final concentration of 0.1 mM to induce overexpression. After cultivation of cells for a further 4 h, cells were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C). The cell pellets were resuspended with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). These cell suspensions were disrupted by sonication, and crude cell extracts were obtained by centrifugation (5,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C). The cell extracts were further incubated at 80°C for 15 min and centrifuged (20,400 × g for 10 min at 4°C). Supernatants after the centrifugation were applied to an anion-exchange column, Resource Q (GE Healthcare Biosciences), equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Both Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) were eluted by a linear gradient of NaCl (0 to 1 M) using the protein purification system ÄKTA avant 25 (GE Healthcare Biosciences). For the purification of Tc-ChiD(ΔS), the peak fractions after anion-exchange column were collected, and (NH4)2SO4 was added to a final concentration of 1.5 M. The mixture was centrifuged (5,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C), and the resulting precipitate was dissolved in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) plus 150 mM NaCl. For the purification of Tc-ChiD(ΔBD), (NH4)2SO4 was added to the peak fractions after anion-exchange chromatography at a final concentration of 1.0 M, and the mixture was applied to a hydrophobic interaction column, Resource ISO (GE Healthcare Biosciences), and eluted with a linear gradient of (NH4)2SO4 (1 to 0 M). Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) proteins after each step were collected and further applied to a gel filtration column, Superdex 200 (GE Healthcare Biosciences) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) plus 150 mM NaCl. Fractions containing Tc-ChiD(ΔS) or Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) were concentrated using Vivaspin 2 (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany). The protein concentrations were determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Preparation of colloidal chitin.

Chitin from crab shells (2.5 g; Nacalai Tesque) was mixed with 125 ml of phosphoric acid (85% [wt/vol] in H2O) and stirred at 4°C for 24 h. The suspension was poured into 1.25 liter of deionized H2O and centrifuged (15,300 × g for 10 min at 4°C). The resulting precipitate was washed with deionized H2O until the pH of the suspension became neutral, and it was suspended with 100 ml of deionized H2O. The concentration of chitin in the suspension was determined by measuring dry chitin weight.

Chitinase assay by thin-layer chromatography.

Chitin degradation activity of Tc-ChiD(ΔS) or Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) was measured using the GlcNAc oligomers G2 (N,N′-diacetylchitobiose), G3 (N,N′,N″-triacetylchitotriose), G4 (N,N′,N″,N‴-tetraacetylchitotetraose), G5 (N,N′,N″,N‴,N⁗-pentaacetylchitopentaose), and G6 (N,N′,N″,N‴,N⁗,N‴″-hexaacetylchitohexaose) (Seikagaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) (Megazyme, Co. Wicklow, Ireland) or their p-nitrophenyl (pNP) derivatives (pNP-G2 [p-nitrophenyl N,N′-diacetylchitobioside], pNP-G3 [p-nitrophenyl N,N′,N″-triacetylchitotrioside], pNP-G4 [p-nitrophenyl N,N′,N″,N‴-tetraacetylchitotetraoside], and pNP-G5 [p-nitrophenyl N,N′,N″,N‴,N⁗-pentaacetylchitopentaoside]) (Seikagaku Corporation). In a typical reaction, GlcNAc oligomers (1.4 mg ml−1) or p-nitrophenyl GlcNAc oligomers (1 mM) were added with enzyme (0.67 μM) in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 5.0), and reactions were performed at 85°C for a defined time, like 5, 15, 30, 60, or 120 min. Reaction mixtures were spotted onto a silica gel plate (DC Kieselgel 60; Merck Co., Berlin, Germany) and developed with a solvent composed of 1-butanol–methanol–ammonia solution (25% in water)–water (5:4:2:1 [vol/vol/vol/vol]). The products were determined by spraying the plate with aniline-diphenylamine reagent (4 ml of aniline, 4 g of diphenylamine, 200 ml of acetone, and 30 ml of 85% phosphoric acid) and baking at 180°C for 3 min.

Effects of pH and temperature on chitinase activity.

Chitinase activity was measured under various pH and temperature conditions with the Schales procedure, with some modification (26). Colloidal chitin was used as the substrate (final concentration, 0.2% [wt/vol]), and the standard assay was performed at 85°C in 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 5.0) for 10 min. Reactions were terminated by cooling samples on ice, and the amount of reducing sugar generated was measured using GlcNAc as the standard. The pH dependence of chitinase activity was determined at 85°C with the following buffers: 50 mM sodium citrate (pH 3.0 to 5.0), 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 4.5 to 6.0), and 50 mM 2-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid monohydrate (MES) (pH 6.0 to 7.0). The optimal temperature was examined between 50 and 95°C in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.0) using colloidal chitin as the substrate.

Thermostability of the recombinant Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) proteins.

The purified Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) proteins in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) supplemented with 150 mM NaCl were incubated for various periods of time at 80, 90, or 100°C. After cooling the protein solutions on ice, the remaining chitinase activity was measured by the modified Schales procedure described above.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The gene sequences of T. chitonophagus chiA, chiC, and chiD have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under the accession numbers LC134313, LC134314, and LC121823, respectively.

RESULTS

Draft genome analysis of T. chitonophagus and identification of Tc-ChiD.

As T. chitonophagus is able to grow using chitin as the sole carbon source, the organism is expected to possess an efficient system for chitin degradation and assimilation. In order to elucidate the chitin degradation process, we performed a genomic analysis of T. chitonophagus. The genomic DNA of T. chitonophagus was isolated and analyzed by HiSeq 2000 (Illumina) using a paired-end sequencing strategy. From the total nucleotide reads of >2,073 Mbp, 20 contigs were assembled that constituted 1,964,779 nucleotides with a G+C content of 44.91%. Open reading frame (ORF) prediction resulted in the identification of 2,168 ORFs.

In order to identify genes involved in chitin degradation, we searched for protein sequences that included regions displaying sequence similarity to the following elements in Tk-ChiA: (i) the exo-chitinase domain, (ii) the endo-chitinase domain, (iii) the ChBD of CBM family 2, and (iv) the ChBD of CBM family 5. In all four cases, an orthologous gene for Tk-chiA was identified. The gene consists of 3,870 bp and encodes a protein (Tc-ChiA) of 1,289 amino acid residues (approximately 142 kDa) (see Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). Tc-ChiA displays a domain structure identical to that of Tk-ChiA: a signal sequence, a ChBD of the CBM family 5, a GH18 family catalytic domain (74% identical to the exo-chitinase domain of Tk-ChiA), two consecutive ChBDs of the CBM family 2, and a second GH18 family catalytic domain (73% identical to the endo-chitinase domain of Tk-ChiA). Using the exo-chitinase domain of Tk-ChiA, we identified another gene encoding a putative chitinase adjacent to Tc-chiA. The gene consists of 1,806 bp and encodes a protein (Tc-ChiC) of 601 amino acid residues (approximately 68.1 kDa) containing a signal sequence, a ChBD of the CBM family 5, and a GH18 family catalytic domain (66% identical to the exo-chitinase domain of Tk-ChiA) (see Fig. S1 and S3 in the supplemental material). Tc-ChiC contains a putative transmembrane region at the carboxy terminus.

A third gene was identified with a search using the Tk-ChiA ChBD of CBM family 2. The gene consists of 2,418 bp and encodes a protein (designated here Tc-ChiD) of 805 amino acid residues (approximately 90 kDa) (see Fig. S1 and S4 in the supplemental material). The amino-terminal sequence of Tc-ChiD includes two basic residues (KR), followed by a hydrophobic stretch of 11 residues, suggesting that it corresponds to a signal sequence for secretion. Following the signal sequence, two putative ChBDs (ChBD1, residues 33 to 133; ChBD2, residues 181 to 280) are present. Both domains belong to CBM family 2, and they are 41.2% identical to each other. These ChBDs show high sequence similarities with the second (39.6% and 59.2% identical, respectively) and third (39.0% and 56.6%, respectively) ChBDs of Tk-ChiA (17) and the ChBD (38.0% and 56.7%, respectively) of Pf-ChiB (20) (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). According to three-dimensional (3D) structural analyses of ChBDs from Tk-ChiA and Pf-ChiB, the chitin-binding surface is composed of three solvent-exposed tryptophan residues (Trp636, Trp669, and Trp687 for ChBD2 of Tk-ChiA; Trp779, Trp812, and Trp830 for ChBD3 of Tk-ChiA; and Trp274, Trp308, and Trp326 for Pf-ChiB) (27–29). These tryptophan residues are also conserved in both ChBDs of Tc-ChiD. In contrast to the amino-terminal region, the function of the carboxy-terminal region of Tc-ChiD could not be clearly predicted based on primary structure alone. A homology search using the region spanning residues 321 to 805 of Tc-ChiD identified a homologous group of proteins found in various strains of Clostridium botulinum, a mesophilic anaerobic bacterium (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The proteins in this group are mostly annotated as hypothetical proteins, but some are predicted to be related to chitinase, such as H04402_02911 in C. botulinum strain H04402 065 (annotated as chitinase Jessie 3) and CLL_A1377 in C. botulinum strain B Eklund 17B (NRP) (annotated as secreted chitodextrinase). Although the annotation of CBO2831 from C. botulinum strain Hall A is a hypothetical protein, Sebaihia et al. (30) described that it encodes a predicted secreted protein that is weakly similar to chitinases but has no apparent catalytic or chitin-binding domains. Tc-ChiD and its homologs in C. botulinum strains do not contain the conserved motifs frequently observed in chitinases, such as the DXDXE catalytic motif of GH18 family chitinases or the Y-[FHY]-G-R-G-[AP]-x-Q-[IL]-[ST]-[FHYW]-[HN]-[FY]-NY motif found in GH19 family chitinases (31). To our knowledge, there is no report on the biochemical analysis of these proteins from Clostridium. The carboxy-terminal domain of Tc-ChiD also exhibits weak homology to eucaryal proteins found in the genus Entamoeba belonging to the phylum Amoebozoa, for example, Jessie 3 lectin of Entamoeba histolytica (EHI_152170) (32). E. histolytica Jessie 3 lectin harbors a unique ChBM of CBM family 55, followed by a domain showing weak similarity to the carboxy-terminal domain of Tc-ChiD (see Table S1). The Jessie 3 lectin of E. histolytica, produced as recombinant proteins fused with a maltose-binding domain, did not exhibit chitinase activity (33).

Overexpression and purification of the recombinant Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD).

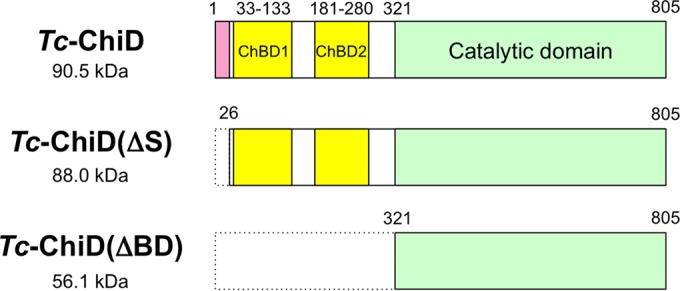

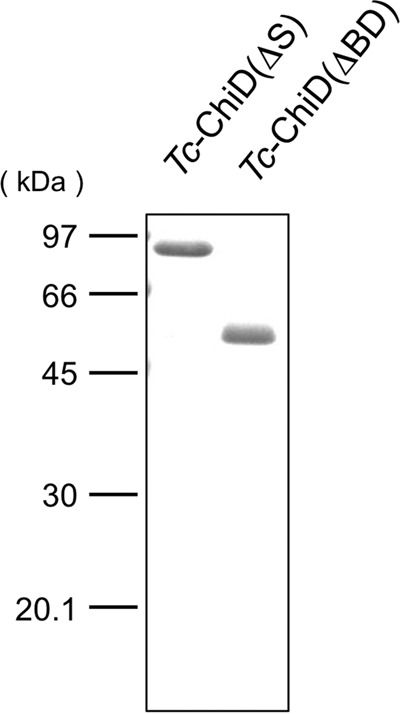

As there was a possibility that Tc-ChiD represented a structurally novel chitinase, we set out to elucidate the biochemical function of the protein. Two types of recombinant Tc-ChiD proteins were prepared. One includes the entire protein without the predicted signal sequence [Tc-ChiD(ΔS)], and the other contains only the region downstream of the two ChBDs [Tc-ChiD(ΔBD)] (Fig. 1). The two proteins were produced in E. coli using the T7 promoter/pET21a system and purified to homogeneity (Fig. 2), as described in Materials and Methods.

FIG 1.

Structural features of the ChiD from T. chitonophagus (Tc-ChiD) and truncated Tc-ChiD proteins [Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD)]. A putative signal sequence (pink, residues 1 to 25), two chitin-binding domains (ChBDs) (yellow, residues 33 to 133 and 181 to 280), and a putative catalytic domain (green, residues 321 to 805) are indicated.

FIG 2.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) purified from recombinant E. coli strains. Purified Tc-ChiD(ΔS) (87.8 kDa) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) (56.1 kDa) were applied (1 μg each).

Chitinase activity of Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD).

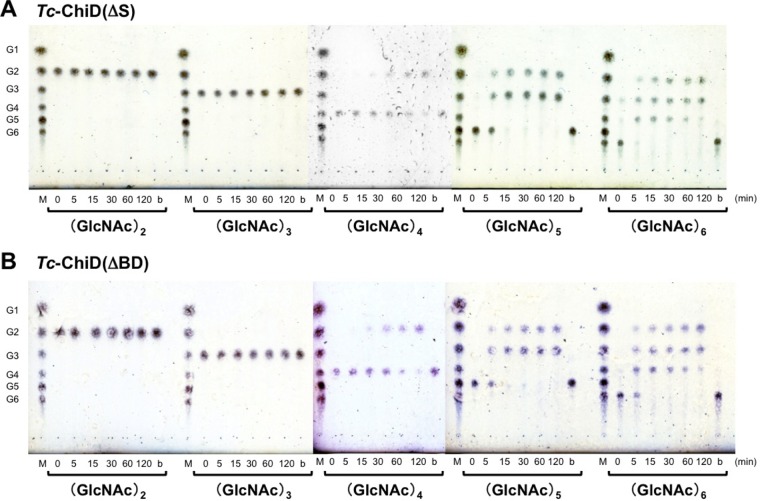

The chitinase activities of the recombinant Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) proteins were examined by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using (GlcNAc)n oligomers (n = 2 to 6) as the substrates (Fig. 3A and B). For both enzymes, degradation products were observed for (GlcNAc)n substrates longer than n = 4 [i.e., (GlcNAc)4, (GlcNAc)5, and (GlcNAc)6], whereas (GlcNAc)2 and (GlcNAc)3 were not hydrolyzed. When using (GlcNAc)4 as the substrate, the product was (GlcNAc)2. (GlcNAc)5 was converted into (GlcNAc)3 and (GlcNAc)2. When using (GlcNAc)6 as the substrate, (GlcNAc)3 and (GlcNAc)2 were generated.

FIG 3.

TLC of hydrolysis products of various GlcNAc oligomers incubated with Tc-ChiD(ΔS) (A) or Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) (B). Reaction mixtures containing 1.4 g liter−1 substrate in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.0) were incubated with either Tc-ChiD(ΔS) or Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) (6.8 μM each) at 85°C for the indicated time periods (0 to 120 min). Lanes M, standard GlcNAc oligomers ranging from GlcNAc to (GlcNAc)6 (G1 to G6); lanes b, blank control incubated without enzyme for 120 min at 85°C.

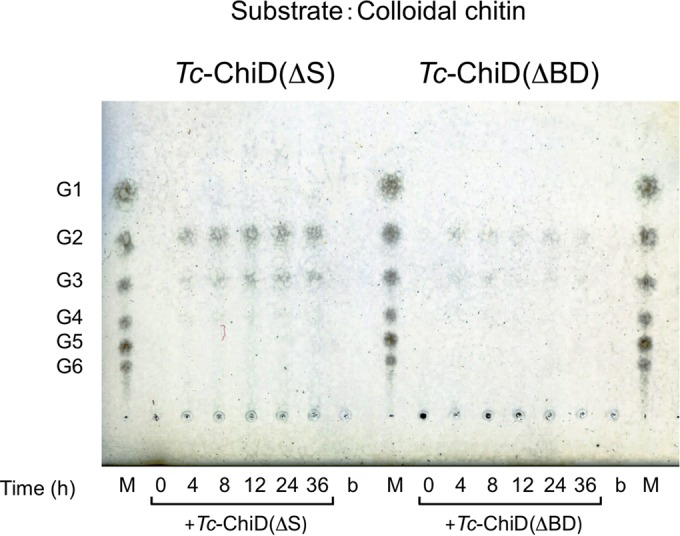

In order to determine whether the Tc-ChiD proteins were endo-type enzymes or whether they were exo-type enzymes that recognized the ends of (GlcNAc)n chains, we next examined the products generated from the colloidal chitin. As shown in Fig. 4, the main products were (GlcNAc)2 and (GlcNAc)3, indicating that both proteins recognized the ends of chitin oligomers and are exo-type enzymes. We also observed that reactions with Tc-ChiD(ΔS) resulted in a greater accumulation of product than those with Tc-ChiD(ΔBD).

FIG 4.

TLC analysis of reaction products of colloidal chitin incubated with Tc-ChiD(ΔS) or Tc-ChiD(ΔBD). Reaction mixtures containing 0.2% (wt/vol) colloidal chitin as a substrate in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) were incubated with either Tc-ChiD(ΔS) or Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) (0.67 μM) at 85°C for the indicated time periods (0 to 36 h). The reaction products were analyzed after centrifugation. Lanes M, standard GlcNAc oligomers ranging from GlcNAc to (GlcNAc)6 (G1 to G6); lanes b, blank control incubated without enzyme for 36 h at 85°C.

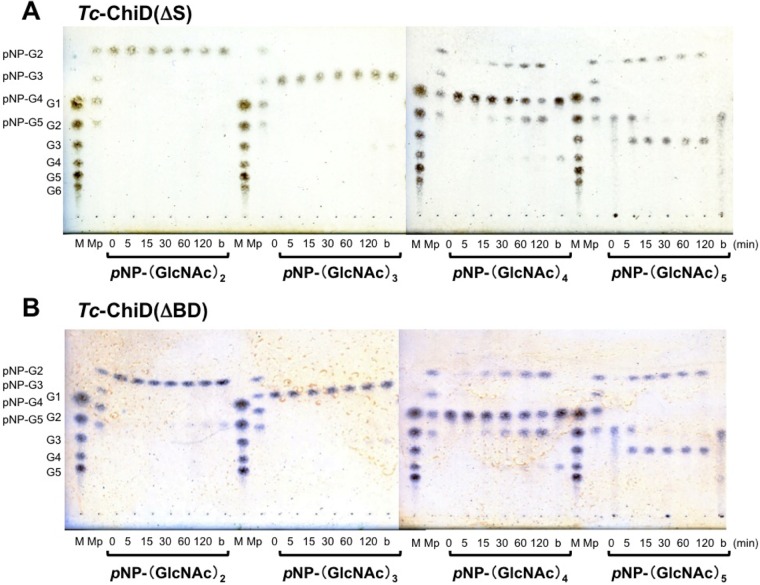

In order to identify the end (reducing and/or nonreducing) recognized by Tc-ChiD, p-nitrophenyl GlcNAc oligomers, in which the reducing end is modified with p-nitrophenol (pNP), were used as the substrates. pNP-(GlcNAc)n (n = 2 to 5) substrates were individually incubated with Tc-ChiD(ΔS) or Tc-ChiD(ΔBD), and the free pNP released from the substrates was monitored by measuring absorption at 405 nm. Absorbance was not detected in any of the reactions (data not shown), indicating that both enzymes at least do not cleave the first glycosidic bond that links the reducing end of GlcNAc oligomer and pNP. In order to identify the degradation products, the reaction mixtures were analyzed by TLC (Fig. 5). As a result, pNP-(GlcNAc)2 and pNP-(GlcNAc)3 were not hydrolyzed by either enzyme. When pNP-(GlcNAc)4 was used as the substrate, spots corresponding to pNP-(GlcNAc)2 and (GlcNAc)2 were detected. In the case of pNP-(GlcNAc)5, spots corresponding to pNP-(GlcNAc)2 and (GlcNAc)3 were detected, and pNP-(GlcNAc)3 could not be detected. These results suggest that Tc-ChiD recognizes the reducing end of chitin and cleaves the second glycosidic linkage.

FIG 5.

TLC of hydrolysis products of various p-nitrophenyl GlcNAc oligomers incubated with Tc-ChiD(ΔS) (A) or Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) (B). Reaction mixtures containing 1 mM substrate in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.0) were incubated with either Tc-ChiD(ΔS) or Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) (6.8 μM) at 85°C for the indicated time periods (0 to 120 min). Lanes M, standard GlcNAc oligomers ranging from GlcNAc to (GlcNAc)6 (G1 to G6); lanes Mp, standard p-nitrophenyl GlcNAc oligomers ranging from pNP-(GlcNAc)2 to pNP-(GlcNAc)5 (pNP-G2 to pNP-G5); lanes b, blank control incubated without enzyme for 120 min at 85°C.

In order to confirm that Tc-ChiD is specific toward chitin, the enzyme was incubated with other oligosaccharides, such as chitosan (β-1,4-linked glucosamine oligomers), cellulose (β-1,4-linked glucose oligomers), and amylose (α-1,4-linked glucose oligomers). Degradation products were not observed, confirming that Tc-ChiD is a chitinase (data not shown).

Enzymatic properties of Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD).

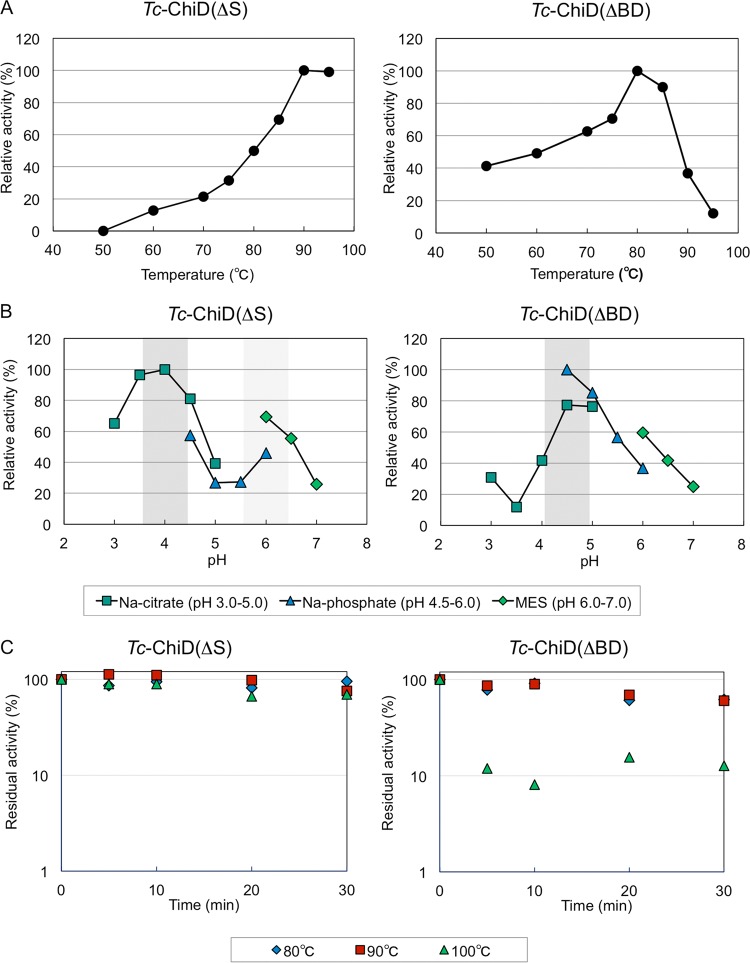

Chitinase activities of Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) were analyzed under near-optimal growth conditions of T. chitonophagus. Chitinase activities of Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) were quantified by a modification of the Schales procedure using 0.2% (wt/vol) colloidal chitin as the substrate. When we examined the effects of temperature on activity, Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) displayed the highest activity at 80°C (1.02 × 102 μmol min−1 μmol protein−1), with a significant decrease observed at temperatures of >90°C, whereas Tc-ChiD(ΔS) exhibited the highest activity at 90°C (3.12 × 101 μmol min−1 μmol protein−1) (Fig. 6A). Arrhenius plots of the data indicate that the activation energies of the reactions were 80.5 kJ mol−1 for Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and 24.3 kJ mol−1 for Tc-ChiD(ΔBD). The effects of pH on chitinase activity were also examined at 85°C under various pH conditions (pH 3.0 to 7.0). As a result, both enzymes showed high activity at a pH range from 4.0 to 4.5 (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, Tc-ChiD(ΔS) showed an increase in activity at around pH 6.0. In terms of thermostability, the two enzymes were incubated at 80, 90, or 100°C for various periods of time, and their residual activities were examined (Fig. 6C). As a result, the half-life of Tc-ChiD(ΔBD) was 40 min at both 80 and 90°C, and the residual activity dramatically decreased to approximately 10% within 5 min at 100°C. In the case of Tc-ChiD(ΔS), the half-lives at 80°C, 90°C, and 100°C were 10 h, 1.3 h, and 48 min, respectively. The results indicate that the catalytic domain alone [Tc-ChiD(ΔBD)] displays higher initial velocity, but the presence of the ChBDs of Tc-ChiD [Tc-ChiD(ΔS)] greatly contributes to increasing the thermostability of the protein. This is reflected in the results of Fig. 4, in which product formation was examined after relatively long reaction times at 85°C (4 to 36 h).

FIG 6.

(A) Effects of temperature on the activities of Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD). The chitinase activities were determined at different temperatures (50 to 95°C) by using the Schales procedure, as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Effects of pH on the activities of Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD). The chitinase activities were determined at different pH conditions, as described in Materials and Methods. Symbols: dark green squares, sodium citrate (pH 3.0 to 5.0); blue triangles, sodium phosphate (pH 4.5 to 6.0); light green diamonds, MES (pH 6.0 to 7.0). (C) Thermostabilities of Tc-ChiD(ΔS) and Tc-ChiD(ΔBD). Purified enzymes were incubated in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) supplemented with 150 mM NaCl at 80°C (blue diamonds), 90°C (red squares), and 100°C (green triangles) for various time intervals. The residual activities were determined at 85°C.

DISCUSSION

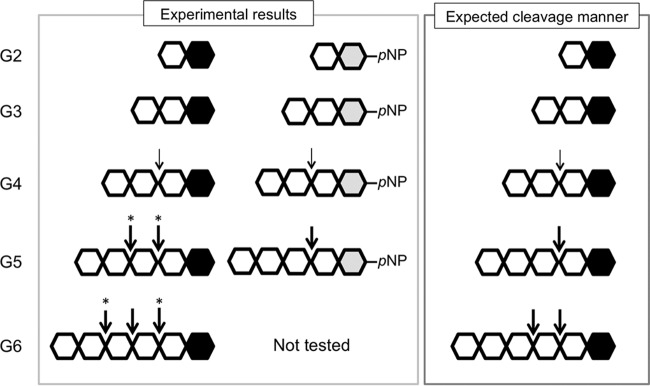

In this study, we have identified a structurally novel chitinase, Tc-ChiD, from the hyperthermophilic archaeon T. chitonophagus. Although we have tried to identify chitinases with similarity to Tc-ChiD, no chitinase sequences of the GH18 and GH19 families were found at least up to an 8.6 E value in a BLAST search (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Tc-ChiD is specific for chitin and does not cleave chitosan, cellulose, or amylose. The enzyme is an exo-chitinase and mainly releases (GlcNAc)2 units from the reducing ends of chitin chains (Fig. 7).

FIG 7.

Schematic illustration of the reaction catalyzed by Tc-ChiD. Individual GlcNAc monomers are represented by hexagons. The black hexagons indicate the reducing ends of the GlcNAc oligomers, and those in the pNP-GlcNAc oligomers are in gray. Thin arrows indicate positions with lower activities. Asterisks indicate cleavage sites that cannot be distinguished in the experiments.

As indicated above, homologs of the Tc-ChiD protein are not widely distributed in nature. Most intriguingly, homologs of Tc-ChiD are not found in any of the closely related members of the Thermococcales and in any other archaeal genome. The most closely related homologs are confined to members of the bacterial genus Clostridium. As Tc-ChiD does not display structural similarity to any of the previously established chitinase proteins, the protein can be considered to represent a novel GH family.

Compared to chitinases, cellulases have been studied to a much greater extent. Exo-type cellulases (cellobiohydrolases) are divided into two groups: enzymes that recognize the reducing end (mainly belonging to families GH7 and GH48), and enzymes that recognize the nonreducing end (mainly belonging to GH6 and GH48) (34–37). It has been reported that organisms that harbor both types of exo-type cellulases along with an endo-type enzyme, such as Thermomonospora fusca and Trichoderma reesei (34), display relatively high efficiency in cellulose degradation. As for chitinases, a synergistic effect toward chitin degradation has been reported for S. marcescens, which harbors two exo-type chitinases, Sm-ChiA and Sm-ChiB, as well as an endo-type enzyme (38, 39). Sm-ChiA and Sm-ChiB are both members of the GH18 family, but Sm-ChiA hydrolyzes chitin from the reducing end, whereas Sm-ChiB recognizes the nonreducing end (38–40), enabling S. marcescens to degrade chitin chains from both ends. However, reports on chitinases that recognize the reducing end of chitin chains are still limited. Tc-ChiD is the first enzyme from an archaeon with such a mode of substrate recognition. As Tk-ChiA harbored two chitinase domains that exhibited endo-type activity and an exo-type activity that recognized the nonreducing end of chitin (17, 18), the corresponding protein in T. chitonophagus (Tc-ChiA) can also be expected to display similar properties. This would result in T. chitonophagus harboring both kinds of exo-type chitinases along with an endo-type enzyme, and it agrees well with the fact that this archaeon displays high levels of chitin degradation among the Archaea.

The putative chitinase genes on the T. chitonophagus genome allow us to estimate the sizes of the proteins they encode. As described in the introduction, T. chitonophagus has been reported to harbor at least three chitinases with molecular masses of approximately 90, 70, and 50 kDa (Chi90, Chi70, and Chi50, respectively) (23, 41). The T. chitonophagus genome sequence determined here suggests the presence of three chitinases: Tc-ChiA (142 kDa), Tc-ChiC (68 kDa), and Tc-ChiD (90 kDa). According to size alone, Tc-ChiD examined in this study may correspond to Chi90. However, in contrast to the fact that Chi90 was reported as a chitobiase, or β-N-acetylglucosaminidase, Tc-ChiD displayed exo-chitinase activity only toward chitin chains with a length of ≥4 GlcNAc units. On the other hand, Tc-ChiC may correspond to the 70-kDa chitinase, Chi70. Tc-ChiA is too large to correspond to Chi90, Chi70, and Chi50. Further studies will be necessary to accurately predict a correspondence between the proteins identified biochemically and the genes identified by genome analysis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This work, including the efforts of Haruyuki Atomi, was funded by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), through the Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology program within the research area “Creation of Basic Technology for Improved Bioenergy Production through Functional Analysis and Regulation of Algae and Other Aquatic Microorganisms.”

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00319-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gooday GW. 1990. Physiology of microbial degradation of chitin and chitosan. Biodegradation 1:177–190. doi: 10.1007/BF00058835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamid R, Khan MA, Ahmad M, Ahmad MM, Abdin MZ, Musarrat J, Javed S. 2013. Chitinases: an update. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 5:21–29. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.106559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentley SD, Chater KF, Cerdeño-Tárraga AM, Challis GL, Thomson NR, James KD, Harris DE, Quail MA, Kieser H, Harper D, Bateman A, Brown S, Chandra G, Chen CW, Collins M, Cronin A, Fraser A, Goble A, Hidalgo J, Hornsby T, Howarth S, Huang CH, Kieser T, Larke L, Murphy L, Oliver K, O'Neil S, Rabbinowitsch E, Rajandream MA, Rutherford K, Rutter S, Seeger K, Saunders D, Sharp S, Squares R, Squares S, Taylor K, Warren T, Wietzorrek A, Woodward J, Barrell BG, Parkhill J, Hopwood DA. 2002. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 417:141–147. doi: 10.1038/417141a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawase T, Yokokawa S, Saito A, Fujii T, Nikaidou N, Miyashita K, Watanabe T. 2006. Comparison of enzymatic and antifungal properties between family 18 and 19 chitinases from S. coelicolor A3(2). Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 70:988–998. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsujibo H, Okamoto T, Hatano N, Miyamoto K, Watanabe T, Mitsutomi M, Inamori Y. 2000. Family 19 chitinases from Streptomyces thermoviolaceus OPC-520: molecular cloning and characterization. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 64:2445–2453. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gherbawy Y, Elhariry H, Altalhi A, El-Deeb B, Khiralla G. 2012. Molecular screening of Streptomyces isolates for antifungal activity and family 19 chitinase enzymes. J Microbiol 50:459–468. doi: 10.1007/s12275-012-2095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaaje-Kolstad G, Horn SJ, Sørlie M, Eijsink VGH. 2013. The chitinolytic machinery of Serratia marcescens–a model system for enzymatic degradation of recalcitrant polysaccharides. FEBS J 280:3028–3049. doi: 10.1111/febs.12181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collinge DB, Kragh KM, Mikkelsen JD, Nielsen KK, Rasmussen U, Vad K. 1993. Plant chitinases. Plant J 3:31–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1993.t01-1-00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muzzarelli RAA. 1997. Human enzymatic activities related to the therapeutic administration of chitin derivatives. Cell Mol Life Sci 53:131–140. doi: 10.1007/PL00000584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patil RS, Ghormade V, Deshpande MV. 2000. Chitinolytic enzymes: an exploration. Enzyme Microb Technol 26:473–483. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(00)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki M, Morimatsu M, Yamashita T, Iwanaga T, Syuto B. 2001. A novel serum chitinase that is expressed in bovine liver. FEBS Lett 506:127–130. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02893-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu XH, Zhang H, Fukamizo T, Muthukrishnan S, Kramer KJ. 2001. Properties of Manduca sexta chitinase and its C-terminal deletions. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 31:1221–1230. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(01)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ueda M, Ohata K, Konishi T, Sutrisno A, Okada H, Nakazawa M, Miyatake K. 2009. A novel goose-type lysozyme gene with chitinolytic activity from the moderately thermophilic bacterium Ralstonia sp. A-471: cloning, sequencing, and expression. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 81:1077–1085. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1676-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arimori T, Kawamoto N, Shinya S, Okazaki N, Nakazawa M, Miyatake K, Fukamizo T, Ueda M, Tamada T. 2013. Crystal structures of the catalytic domain of a novel glycohydrolase family 23 chitinase from Ralstonia sp. A-471 reveals a unique arrangement of the catalytic residues for inverting chitin hydrolysis. J Biol Chem 288:18696–18706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.462135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujita K, Shimomura K, Yamamoto K, Yamashita T, Suzuki K. 2006. A chitinase structurally related to the glycoside hydrolase family 48 is indispensable for the hormonally induced diapause termination in a beetle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 345:502–507. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Staufenberger T, Imhoff JF, Labes A. 2012. First crenarchaeal chitinase found in Sulfolobus tokodaii. Microbiol Res 167:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka T, Fujiwara S, Nishikori S, Fukui T, Takagi M, Imanaka T. 1999. A unique chitinase with dual active sites and triple substrate binding sites from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus kodakaraensis KOD1. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:5338–5344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka T, Fukui T, Imanaka T. 2001. Different cleavage specificities of the dual catalytic domains in chitinase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis KOD1. J Biol Chem 276:35629–35635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105919200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oku T, Ishikawa K. 2006. Analysis of the hyperthermophilic chitinase from Pyrococcus furiosus: activity toward crystalline chitin. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 70:1696–1701. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao J, Bauer MW, Shockley KR, Pysz MA, Kelly RM. 2003. Growth of hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus on chitin involves two family 18 chitinases. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:3119–3128. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.6.3119-3128.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreuzer M, Schmutzler K, Waege I, Thomm M, Hausner W. 2013. Genetic engineering of Pyrococcus furiosus to use chitin as a carbon source. BMC Biotechnol 13:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-13-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huber R, Stöhr J, Hohenhaus S, Rachel R, Burggraf S, Jannasch HW, Stetter KO. 1995. Thermococcus chitonophagus sp. nov., a novel, chitin-degrading, hyperthermophilic archaeum from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent environment. Arch Microbiol 164:255–264. doi: 10.1007/BF02529959. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andronopoulou E, Vorgias CE. 2003. Purification and characterization of a new hyperthermostable, allosamidin-insensitive and denaturation-resistant chitinase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus chitonophagus. Extremophiles 7:43–53. doi: 10.1007/s00792-002-0294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andronopoulou E, Vorgias CE. 2004. Isolation, cloning, and overexpression of a chitinase gene fragment from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus chitonophagus: semi-denaturing purification of the recombinant peptide and investigation of its relation with other chitinases. Protein Expr Purif 35:264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato T, Fukui T, Atomi H, Imanaka T. 2003. Targeted gene disruption by homologous recombination in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis KOD1. J Bacteriol 185:210–220. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.1.210-220.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imoto T, Yagishit K. 1971. A simple activity measurement of lysozyme. Agr Biol Chem 35:1154–1156. doi: 10.1271/bbb1961.35.1154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mine S, Nakamura T, Hagihara Y, Ishikawa K, Ikegami T, Uegaki K. 2006. NMR assignment of the chitin-binding domain of a hyperthermophilic chitinase from Pyrococcus furiosus. J Biomol NMR 36:70–70. doi: 10.1007/s10858-006-9058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakamura T, Mine S, Hagihara Y, Ishikawa K, Ikegami T, Uegaki K. 2008. Tertiary structure and carbohydrate recognition by the chitin-binding domain of a hyperthermophilic chitinase from Pyrococcus furiosus. J Mol Biol 381:670–680. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanazono Y, Takeda K, Niwa S, Hibi M, Takahashi N, Kanai T, Atomi H, Miki K. 2016. Crystal structures of chitin binding domains of chitinase from Thermococcus kodakarensis KOD1. FEBS Lett 590:298–304. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sebaihia M, Peck MW, Minton NP, Thomson NR, Holden MTG, Mitchell WJ, Carter AT, Bentley SD, Mason DR, Crossman L, Paul CJ, Ivens A, Wells-Bennik MHJ, Davis IJ, Cerdeño-Tárraga AM, Churcher C, Quail MA, Chillingworth T, Feltwell T, Fraser A, Goodhead I, Hance Z, Jagels K, Larke N, Maddison M, Moule S, Mungall K, Norbertczak H, Rabbinowitsch E, Sanders M, Simmonds M, White B, Whithead S, Parkhill J. 2007. Genome sequence of a proteolytic (group I) Clostridium botulinum strain Hall A and comparative analysis of the clostridial genomes. Genome Res 17:1082–1092. doi: 10.1101/gr.6282807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huet J, Rucktooa P, Clantin B, Azarkan M, Looze Y, Villeret V, Wintjens R. 2008. X-ray structure of papaya chitinase reveals the substrate binding mode of glycosyl hydrolase family 19 chitinases. Biochemistry 47:8283–8291. doi: 10.1021/bi800655u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Dellen K, Ghosh SK, Robbins PW, Loftus B, Samuelson J. 2002. Entamoeba histolytica lectins contain unique 6-Cys or 8-Cys chitin-binding domains. Infect Immun 70:3259–3263. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.3259-3263.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chatterjee A, Ghosh SK, Jang K, Bullitt E, Moore L, Robbins PW, Samuelson J. 2009. Evidence for a “wattle and daub” model of the cyst wall of Entamoeba. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000498. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barr BK, Hsieh YL, Ganem B, Wilson DB. 1996. Identification of two functionally different classes of exocellulases. Biochemistry 35:586–592. doi: 10.1021/bi9520388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boisset C, Fraschini C, Schülein M, Henrissat B, Chanzy H. 2000. Imaging the enzymatic digestion of bacterial cellulose ribbons reveals the endo character of the cellobiohydrolase Cel6A from Humicola insolens and its mode of synergy with cellobiohydrolase Cel7A. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:1444–1452. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.4.1444-1452.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sánchez MM, Pastor FIJ, Diaz P. 2003. Exo-mode of action of cellobiohydrolase Cel48C from Paenibacillus sp. BP-23–a unique type of cellulase among Bacillales. Eur J Biochem 270:2913–2919. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zverlov VV, Velikodvorskaya GA, Schwarz WH. 2002. A newly described cellulosomal cellobiohydrolase, CelO, from Clostridium thermocellum: investigation of the exo-mode of hydrolysis, and binding capacity to crystalline cellulose. Microbiology 148:247–255. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-1-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horn SJ, Sørbotten A, Synstad B, Sikorski P, Sørlie M, Vårum KM, Eijsink VGH. 2006. Endo/exo mechanism and processivity of family 18 chitinases produced by Serratia marcescens. FEBS J 273:491–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hult EL, Katouno F, Uchiyama T, Watanabe T, Sugiyama J. 2005. Molecular directionality in crystalline beta-chitin: hydrolysis by chitinases A and B from Serratia marcescens 2170. Biochem J 388:851–856. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Honda Y, Taniguchi H, Kitaoka M. 2008. A reducing-end-acting chitinase from Vibrio proteolyticus belonging to glycoside hydrolase family 19. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 78:627–634. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1352-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andronopoulou E, Vorgias CE. 2004. Multiple components and induction mechanism of the chitinolytic system of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus chitonophagus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 65:694–702. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1640-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.