Abstract

The Rb1 tumor suppressor protein is a molecular adaptor that physically links transcription factors like E2f with various proteins acting on DNA or RNA to repress gene expression. Loss of Rb1 liberates E2f to activate the expression of genes mediating resulting phenotypes. Most Rb1 binding proteins, including E2f, interact through carboxyl-terminal protein interaction domains, but genetic evidence suggests that an amino-terminal protein interaction domain is also important. One protein that binds Rb1 through the amino-terminal domain is encoded by Thoc1, a required component of the THO ribonucleoprotein complex important for RNA processing and transport. The physiological relevance of this interaction is unknown. Here we tested whether Thoc1 mediates effects of Rb1 loss on mouse embryonic development. We found that Thoc1 deficiency delays embryo death, and this delay correlates with reduced apoptosis in the brain. E2f protein levels are reduced in Rb1:Thoc1-deficient brain tissue. Expression of apoptotic regulatory genes regulated by E2f, like Apaf1 and Bak1, is also reduced. These observations suggest that Thoc1 is required to support increased expression of E2f and apoptotic regulatory genes that trigger apoptosis upon Rb1 loss. These findings implicate Rb1 in the regulation of the THO ribonucleoprotein complex.

INTRODUCTION

Mutation of the RB1 tumor suppressor gene causes the pediatric cancer retinoblastoma, and deregulation of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene product is observed in most other types of human cancer (1). Rb1 is also essential for normal embryonic development (2–4). At the cellular level, Rb1 regulates pleiotropic functions, including the cell cycle, DNA damage responses, cellular senescence, cellular differentiation, metabolism, and transcription, among others (5–8). At the molecular level, Rb1 functions as an adaptor that physically interacts with cellular proteins to nucleate the formation of protein complexes in specified regions of the genome (6). The paradigm for this model is based on the binding of Rb1 with E2f transcription factors. Upon binding, Rb1 inhibits E2f-mediated transcriptional transactivation and recruits chromatin-modifying activities to stably repress gene expression.

As befits a molecular adaptor, Rb1 contains multiple protein interaction domains within the carboxyl (RbC)- and amino (RbN)-terminal halves of the protein. Structural characterization by crystallography indicates that both RbC and RbN contain analogous tandem cyclin fold structures widely utilized in nature for protein interaction (9). Most of the cellular proteins currently known to bind Rb1, including E2f, do so through the RbC tandem cyclin fold. A smaller number of cellular proteins are known to bind the less-well-studied RbN protein binding domain (10). Nonetheless, RbN appears to be important for Rb1 tumor suppressor activity, as some retinoblastoma patients carry amino acid substitution mutations mapping to this region (10). Further, Rb1 alleles containing RbN mutations fail to support normal embryonic development (11). Mechanisms underlying requirements for RbN in tumor suppression and/or normal development are not clear.

One protein that physically interacts with RbN is encoded by the Thoc1 gene (9, 12). Thoc1 is an essential subunit of the evolutionarily conserved THO complex. THO is assembled on nascent RNA transcripts to facilitate RNA processing and transport (13–16). Thoc1 is widely and variably expressed in tissues of the adult mouse and during embryonic development (17, 18). Loss of Thoc1 causes early embryonic death (17); thus, its function is nonredundant. In adult mice, induced Thoc1 deletion causes defects in a limited number of rapidly dividing cells like intestinal stem cells and myeloid progenitor cells (19, 20). Mice homozygous for a hypomorphic Thoc1 allele expressing reduced Thoc1 are viable (18, 21). These findings suggest that requirements for Thoc1 may be higher in rapidly proliferating cells, perhaps in cells lacking Rb1.

The physiological relevance of Rb1-Thoc1 interaction is not known. Rb1 and Thoc1 appear to have opposite effects on tissue homeostasis. For example, mice engineered with reduced Thoc1 levels or increased Rb1 levels exhibit a dwarf phenotype (18, 22). Rb1 is functionally inactivated in many cancer types, whereas Thoc1 is overexpressed in cancers of the breast, lung, ovary, colon, and prostate (14, 23–27). By analogy to the Rb1-E2f interaction, these observations suggest that liberation of Thoc1 activity upon Rb1 loss may contribute to resulting phenotypes. Here we tested this prediction in the context of mouse development by assessing effects of hypomorphic Thoc1 alleles on well-characterized embryonic phenotypes previously observed in Rb1 null mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse husbandry.

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the department of Laboratory Animal Resources, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY. Mice with previously described null Rb1 (2) and hypomorphic Thoc1 (21) alleles were back-crossed for at least six generations with mice with the C57BL/6 background prior to use. Detection of a vaginal plug in the morning was considered embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5). Adult mice were euthanized by carbon dioxide asphyxiation, while embryos were euthanized by decapitation. Tissues dissected at necropsy were either fixed immediately after dissection in buffered 10% formalin or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

DNA isolation and PCR genotyping.

PCR genotyping was performed with DNA extracted from tail biopsy specimens from recently weaned mice or embryonic yolk sac tissue as described by Laird et al. (28). Briefly, tissues were digested in Laird lysis buffer (100 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.5], 5 mM EDTA, 0.2% SDS, 200 mM NaCl, 100 μg of proteinase K/ml) overnight at 55°C. Undigested tissue was collected by centrifugation, and the supernatant containing genomic DNA was precipitated with an equal volume of isopropanol. The genomic DNA precipitate was removed and dissolved in RNase- and DNase-free water by incubation at 55°C for 1 h. The PCR genotyping assays used for Thoc1 and Rb1 alleles were described previously (2, 21).

Histopathology.

Paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were sectioned serially at a 5-μm thickness on a Microm microtome (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E) staining of sections was performed by deparaffinization in xylene, rehydration through a series of graded ethanol solutions and water, staining with Harris hematoxylin and eosin Y, dehydration with a series of graded alcohol solutions, clearing in xylene, and mounting. Stained sections were visualized and photographed with an Olympus BX41 histology microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Sections were stained for various proteins by standard immunohistochemistry methods. Briefly, sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and boiled in citrate buffer (0.01 M trisodium citrate in water, pH 6.0) in a microwave oven for 15 min; this was followed by blocking of endogenous peroxidase activity with hydrogen peroxide (3% H2O2 in methanol). The tissue sections were rinsed in PBST solution (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS; pH 7.2], 0.1% Tween 20) three times for 5 min each time. Nonspecific binding of the antibody was blocked with BSA solution (1% bovine serum albumin in PBS) or diluted goat serum in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendation (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Sections were incubated with primary antibodies against Ki67 (1:1,000 dilution; Novocastra, United Kingdom), activated caspase 3 (1:500; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), or phosphorylated histone H3 (1:1,000 dilution; Millipore, Billerica, MA) overnight in a humidified chamber. Staining was developed with the ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) or a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:150 dilution; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) with diaminobenzidine (1 mg/ml diaminobenzidine, 1 μl/ml H2O2 in PBS) as a substrate.

The fraction of immunopositive cells was measured by creating nonoverlapping images spanning an entire tissue section with a 20× objective. The number of immunopositive cells and the total number of cells were manually determined in each image of a section and combined to generate the measurement of each mouse.

Western blot analysis.

Protein was extracted from tissue by sonication in lysis buffer (250 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.1% NP-40). The total protein concentration was measured with the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad DC reagent; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Equal amounts of total protein from each sample were denatured by boiling in loading buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 20% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.5 ml of 0.0025% bromophenol blue) and subjected to 8 to 10% SDS-PAGE. Resolved proteins were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and the membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 5% nonfat dry milk dissolved in PBS. Primary antibody incubation for β-actin (1:3,000 dilution; Calbiochem, Billerica, MA), Apaf1 (1:800 dilution; GeneTex, Irvine, CA), Bak1 (1:1,000 dilution; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), Bax (1:2,000 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), Bid (1:1,000 dilution; Cell Signaling), Bim (1:1,000 dilution; Cell Signaling), E2f1 (1:500 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), E2f3 (1:500 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Rbl1 (1:500 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Trp73 (1:500 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), PCNA (1:1,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Rb1 (1:250 dilution; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and Thoc1 (1:5,000 dilution; GeneTex, Irvine, CA) was performed overnight at 4°C. Unbound antibody was removed by washing with PBST. The blots were then incubated with an HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:5,000 dilution; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) for 1 h at room temperature, after which the proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Essential fatty acid analysis.

Analysis of essential fatty acid levels in E13.5 embryos and their placentae was performed at the Vanderbilt Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center lipid lab (Nashville, TN). Briefly, lipids were extracted from tissue with a chloroform-methanol (2:1, vol/vol) solution as described previously (29). Phospholipids and triglycerides were separated by thin-layer chromatography and then methylated by 15% BF3 in methanol (30). The methylated lipids were extracted and separated by gas chromatography. Individual lipid classes were separated by thin-layer chromatography with Silica Gel 60A plates developed in petroleum ether-ethyl ether-acetic acid (80:20:1) and visualized with rhodamine 6G. Fatty acid methyl esters were identified by comparing their retention times to those of known standards. Inclusion of lipid standards with odd-chain fatty acids permitted lipid quantitation in the sample.

Statistical analysis.

Differences in live-to-dead embryo ratios between genotypes were analyzed with Fisher's exact test. For other assays, the mean values of each genotype were compared with unpaired Student t tests with a two-tail distribution. Graphing and statistical analysis were performed in GraphPad Prism version 6.05. P values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Rb1 null embryos die in mid-gestation between E13.5 and E15.5 with defects in the placenta, the nervous system, and erythropoiesis (2–4). Cellular defects observed in these tissues include ectopic cell proliferation and apoptosis mediated through both cell autonomous and cell nonautonomous mechanisms. Since mice homozygous for a hypomorphic Thoc1 allele are viable despite significantly reduced Thoc1 expression (21), we have used this allele to test whether Thoc1 deficiency suppresses defects in embryonic development caused by Rb1 loss.

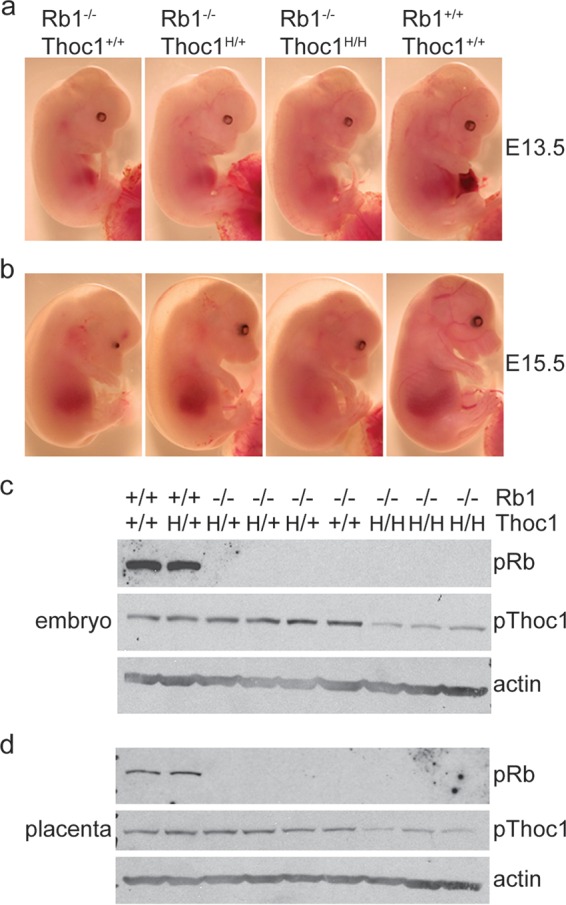

Rb1 null embryos from E13.5 to E15.5 all exhibit morphological abnormalities, including skin pallor, hunched posture, and smaller size. The severity of these defects is somewhat reduced in the presence of hypomorphic Thoc1 alleles (Fig. 1a and b). We visually assessed fetal heartbeats at different ages of gestation to test whether Thoc1 deficiency affects the viability of Rb1 null embryos. Consistent with previously published reports, most Rb1−/− embryos die prior to E15.5 (2–4). The fraction of live E13.5-to-E15.5 Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H embryos (where H represents a hypomorphic allele) is significantly greater than that of Rb1−/− embryos (Table 1) (by Fisher's exact test, P = 0.03). Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/+ embryos also appear to live longer than Rb1−/− embryos, but this difference does not reach statistical significance (by Fisher's exact test, P = 0.15). Rb1−/− embryos deficient in Thoc1 occasionally remain alive past E15.5, but none are born live. As expected, Rb1 expression is undetectable in Rb1−/− embryos (Fig. 1c and d). Thoc1 levels are markedly lower in Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H embryos than in Rb1−/− embryos, consistent with previously published work (18, 21). These observations indicate that reduced Thoc1 levels delay the embryonic death caused by Rb1 loss.

FIG 1.

Gross morphology of Rb1-deficient embryos. (a) E13.5 embryos of the genotypes indicated were removed from timed pregnancies and imaged under a dissecting scope. (b) E15.5 embryos imaged as described above. Note that size, development, and pallor appear to be improved in embryos with hypomorphic Thoc1 alleles (H). (c) Protein was extracted from E15.5 embryos of the genotypes indicated and analyzed by Western blot assay for Rb1 and Thoc1 protein expression. Actin served as a protein loading control. (d) Protein was extracted from matched placentae from the embryos analyzed in panel c and analyzed by Western blotting as described above. Note the Rb1 loss and reduced Thoc1 in the relevant genotypes.

TABLE 1.

Yield of Rb1 mutant embryosa

| Genotype | No. (%) of embryos live/no. dead |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| E13.5 | E14.5 | E15.5 | |

| Rb1−/−:Thoc1+/+ | 15 (88)/2 | 0 (0)/3 | 1 (7)/13 |

| Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/+ | 35 (83)/7 | 8 (67)/4 | 13 (36)/23 |

| Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H | 20 (100)/0 | 2 (100)/0 | 6 (38)/10 |

| Rb1+/−:Thoc1+/+ | 39 (100)/0 | 14 (100)/0 | 56 (95)/3 |

| Rb1+/−:Thoc1H/+ | 93 (100)/0 | 42 (100)/0 | 92 (98)/2 |

| Rb1+/−:Thoc1H/H | 34 (100)/0 | 15 (100)/0 | 45 (94)/3 |

| Rb1+/+:Thoc1+/+ | 28 (100)/0 | 9 (100)/0 | 25 (100)/0 |

| Rb1+/+:Thoc1H/+ | 41 (100)/0 | 24 (100)/0 | 59 (100)/0 |

| Rb1+/+:Thoc1H/H | 12 (100)/0 | 7 (100)/0 | 19 (100)/0 |

Embryos were generated by timed matings between Rb1+/−:Thoc1H/+ mice. Embryos were harvested on the indicated days after the detection of a vaginal plug. Mice with a detectable heartbeat when harvested were considered viable.

The proximal cause of death of Rb1−/− embryos at midgestation is defective placental function (31, 32). Rb1−/− placentae exhibit defective differentiation and ectopic proliferation of trophoblast cells in the labyrinth layer. Overproliferation of trophoblast cells increases the physical separation between maternal and fetal blood vessels, thereby reducing the efficiency of oxygen and nutrient exchange. Inefficient placental transport contributes to a host of downstream defects, including abnormal erythrocyte maturation and apoptosis in the brain. Supplying Rb1 null embryos with a wild-type placenta suppresses some these defects but not others, demonstrating that cell autonomous mechanisms are also involved (31–33).

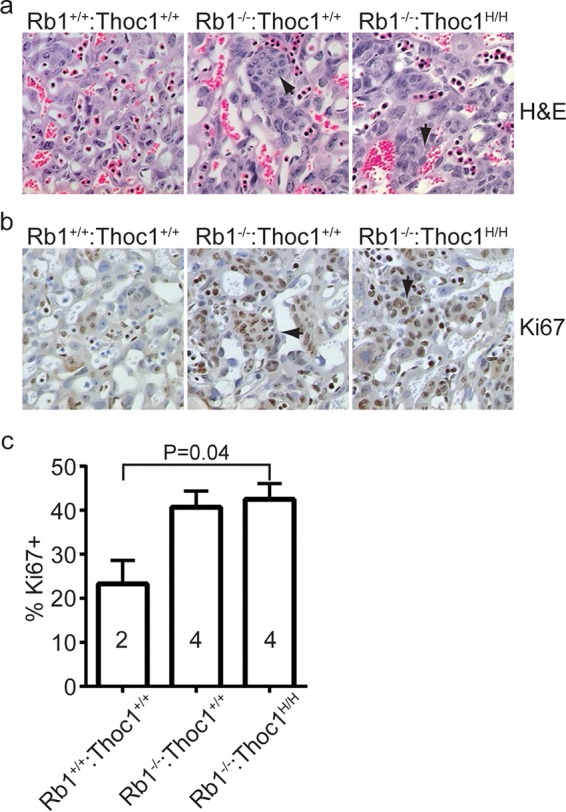

Histological analysis does not reveal consistently detectable differences between Rb1−/− and Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H embryos in the architecture of the placental labyrinth layer (Fig. 2a). Immunohistochemical staining of the proliferation marker Ki67 is comparable in the two genotypes, indicating that they suffer similarly from trophoblast overproliferation (Fig. 2b and c). To directly measure placental transport function, we have compared fatty acid levels in embryos and placentae. Essential fatty acids cannot be synthesized in the body, and hence, embryos must obtain them from the maternal circulation via placental transport. Essential fatty acid levels in the embryo, relative to that of those available from the maternal circulation in the placenta, are thus a measure of placental transport. Nonessential fatty acids serve as a control since they can be synthesized by the embryo independently of placental transport. Rb1−/− embryos are known to exhibit diminished placental transport of essential fatty acids (32, 34). Relative essential fatty acid levels in Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H embryos are not significantly different from those observed in Rb1−/− mice (Table 2). As expected, nonessential fatty acid levels are not affected by Rb1 or Thoc1 deficiency. These data demonstrate that the increased longevity of Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H embryos cannot be accounted for by improved placental transport.

FIG 2.

Histology of the labyrinth layer within E15.5 placentae. (a) Tissue sections from placentae of the genotypes indicated were stained by H&E, and representative sections were imaged by bright-field microscopy with a 20× objective. Arrows indicate islands of overproliferating trophoblast stem cells observed upon Rb1 loss. (b) The tissue sections shown in panel a were immunostained for the proliferation marker Ki67. Islands of Ki67-positive trophoblast stem cells are highlighted by arrows. (c) The fraction of cells staining positive for Ki67 was measured in the placental sections in panel b. The graph shows the mean values and standard errors, and the sample size is indicated within each bar.

TABLE 2.

Essential fatty acid transport in Rb1 mutant embryos

| Genotype and sample or parameter | Avg % of total fatty acids or ratio ± SD |

|

|---|---|---|

| 18:02 + 20:04 + 22:06a | 16:0 + 18:0b | |

| Rb1−/−:Thoc1+/+ (n = 5)/ | ||

| Fetus | 25.8 ± 1.8 | 45.1 ± 2.0 |

| Placenta | 42.9 ± 5.5 | 41.3 ± 4.1 |

| Fetus/placenta ratio | 0.61 ± 0.07 | 1.1 ± 0.13 |

| Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/+ (n = 5)/ | ||

| Fetus | 26.4 ± 1.4 | 44.9 ± 1.3 |

| Placenta | 44.0 ± 4.8 | 42.1 ± 4.8 |

| Fetus/placenta ratio | 0.61 ± 0.09 | 1.1 ± 0.16 |

| Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H (n = 5)/ | ||

| Fetus | 26.3 ± 0.5 | 45.2 ± 0.5 |

| Placenta | 42.7 ± 1.9 | 44.0 ± 1.9 |

| Fetus/placenta ratio | 0.62 ± 0.03 | 1.0 ± 0.05 |

Essential fatty acids.

Nonessential fatty acids.

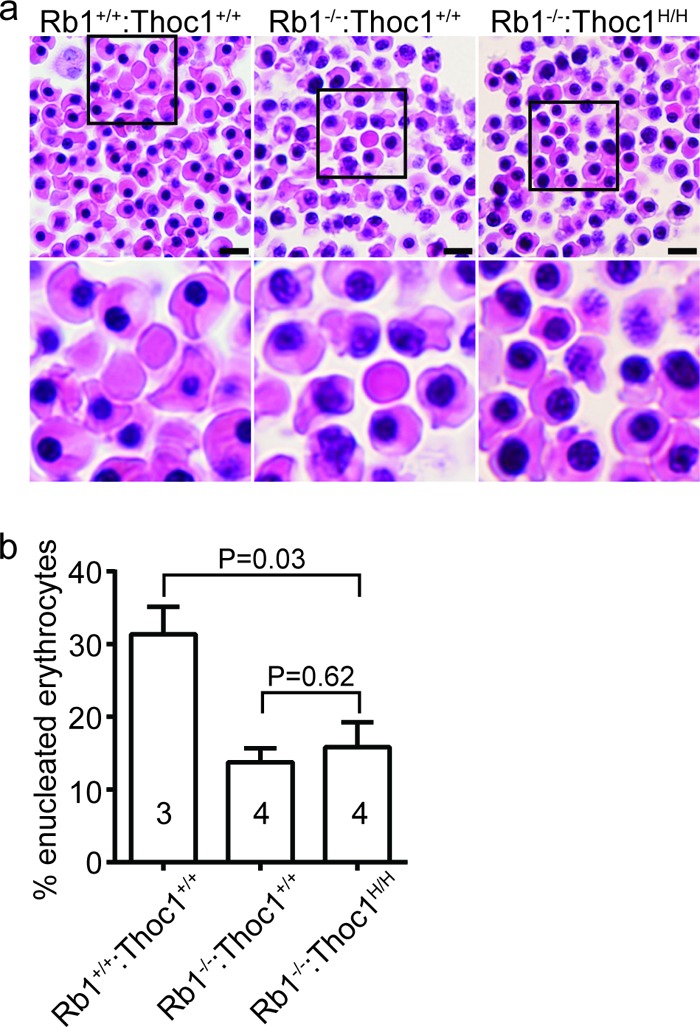

Rb1 is required for normal erythropoiesis, since Rb1 loss causes defects in peripheral blood erythrocyte enucleation (32, 35). Consistent with previously published reports, enucleation is reduced in E13.5 Rb1−/− embryos (Fig. 3a and b). Enucleation is reduced similarly in Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H embryos. Thus, Thoc1 deficiency does not rescue inefficient erythrocyte maturation caused by Rb1 loss. Improved erythrocyte maturation, therefore, does not account for the increased longevity of Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H embryos.

FIG 3.

Peripheral blood erythrocyte maturation in E13.5 embryos. (a) Tissue sections containing peripheral blood spaces from embryos of the genotypes indicated were stained with H&E. Boxed areas in the top row of images are magnified in the lower row. Note that nucleated erythrocytes are relatively abundant at this stage of development but are increased further upon Rb1 loss. Bars, 20 µm. (b) The fractions of enucleated (maturing) peripheral blood erythrocytes in embryos of the genotypes indicated were measured. The graph shows the mean values and standard errors, and the sample size is indicated within each bar.

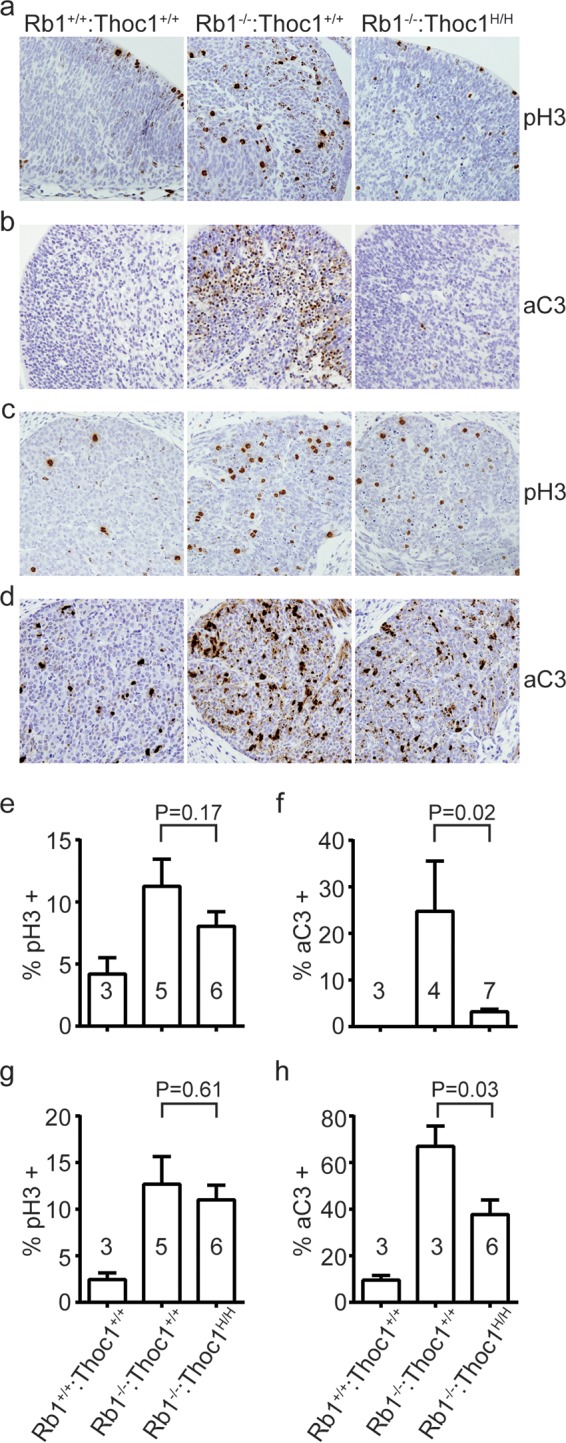

Regions of the mid-gestation brain, like the intermediate zones of the ventricles or the trigeminal ganglia, show pronounced ectopic cell proliferation and apoptosis in Rb1−/− embryos (2–4). We analyzed brain tissue of wild-type, Rb1−/−, and Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H mid-gestation embryos to characterize the effects of Thoc1 deficiency on ectopic cell proliferation and apoptosis. Rb1 loss causes ectopic cell proliferation and widespread apoptosis in the intermediate zone of the fourth ventricle, as expected (Fig. 4a and b). The percentage of cells staining positive for the proliferation marker phosphorylated histone H3 is not significantly different in Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H embryos relative to that in Rb1−/− embryos (Fig. 4e). In contrast, Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H embryos exhibit significantly lower levels of apoptosis (Fig. 4f). Similar results are observed in the trigeminal ganglia (Fig. 4c, d, g, and h). Overall, these observations demonstrate that Thoc1 deficiency significantly suppresses apoptosis but not cell proliferation in the brains of Rb1 null mice. In addition, these findings indicate that apoptosis is not an inevitable consequence of abnormal cell cycle entry caused by Rb1 loss since the two effects are genetically separable.

FIG 4.

Phenotypes associated with Rb1 loss in the brain. (a) Brain sections spanning the intermediate zone of the fourth ventricle from E13.5 embryos of the genotypes indicated were immunostained for the cell proliferation marker phosphorylated histone H3 (pH3). Representative sections imaged by bright-field microscopy with a 20× objective are shown. (b) The brain sections shown in panel a were immunostained with the apoptosis marker activated caspase 3 (aC3). (c) Brain sections spanning the trigeminal ganglia from E13.5 embryos of the genotypes indicated were immunostained for pH3 as described for panel a. (d) Trigeminal ganglion sections were immunostained for aC3 as described for panel b. (e) The fraction of cells near the fourth ventricle staining positive for pH3 in sections from panel a was measured. The graph shows the mean values and standard errors, and the sample size is indicated within each bar. The P value derived with the Student t test by comparing the genotypes indicated is shown. (f) The fraction of aC3 immunopositive fourth ventricle cells from sections in panel b was measured and graphed as in panel e. (g) The fraction of pH3 immunopositive trigeminal ganglion cells from sections in panel c was measured as described for panel e. (h) The fraction of aC3-immunopositive trigeminal ganglion cells from sections in panel d was measured as described for panel e.

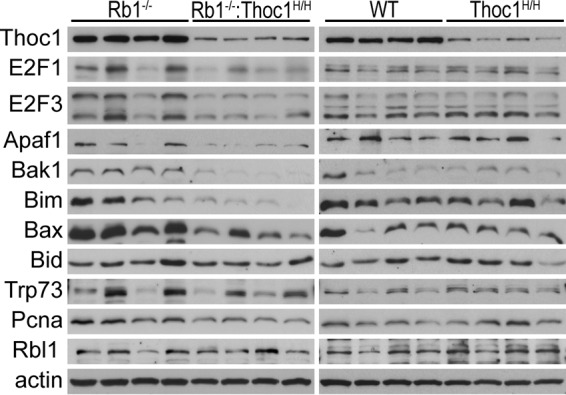

E2f activity mediates brain apoptosis in Rb1−/− embryos (36–38), in part by increasing the expression of apoptotic regulatory genes, which it controls (39, 40). We have examined brain protein extracts from multiple mice to test whether Thoc1 deficiency suppresses the expression of E2f and apoptotic regulatory proteins. E2f1 and E2f3 levels are lower in Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H embryos than those in Rb1−/− embryos (Fig. 5). Protein expression from some E2f-regulated apoptotic regulatory genes, including Apaf1, Bak1, Bim, and Bax, is also reduced in Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H embryos. Other E2f-regulated genes, like Bid, Trp73, Pcna, and Rbl1, express similar protein levels in each genotype. Further, Thoc1 deficiency does not detectably affect protein expression from any of these genes in the context of wild-type Rb1; protein levels are similar in the brains of wild-type and Thoc1H/H embryos. Thus, Thoc1 is specifically required to support the high levels of expression of E2f and some apoptotic regulatory proteins induced by Rb1 loss. On the other hand, low Thoc1 levels in Thoc1H/H embryos are sufficient to support basal-level protein expression. It is unclear whether Thoc1 directly supports the expression of all of the genes affected, reduced expression is indirectly due to the decline in E2f activity, or both. In any case, reduced expression likely contributes to the diminished brain apoptosis observed in Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H embryos. It is also unclear why some genes are affected by reduced Thoc1 while others are not. Perhaps highly expressed genes are preferentially affected by Thoc1 deficiency, as previously reported (23). Alternatively, additional factors may compensate for reduced Thoc1 and/or E2f activity at some genes to maintain high-level expression. For example, Mycn supports the gene expression necessary for cell proliferation in retinae devoid of E2f1, E2f2, and E2f3 (41). Additional work is required to address these questions.

FIG 5.

Thoc1 deficiency reduces E2f protein levels in the mouse brain. Brain tissue protein extracts from E13.5 to E15.5 mouse embryos of the genotypes indicated were prepared. The extracts were assayed by Western blotting for the proteins indicated. Actin served as a protein loading control. Each lane represents results from an individual mouse.

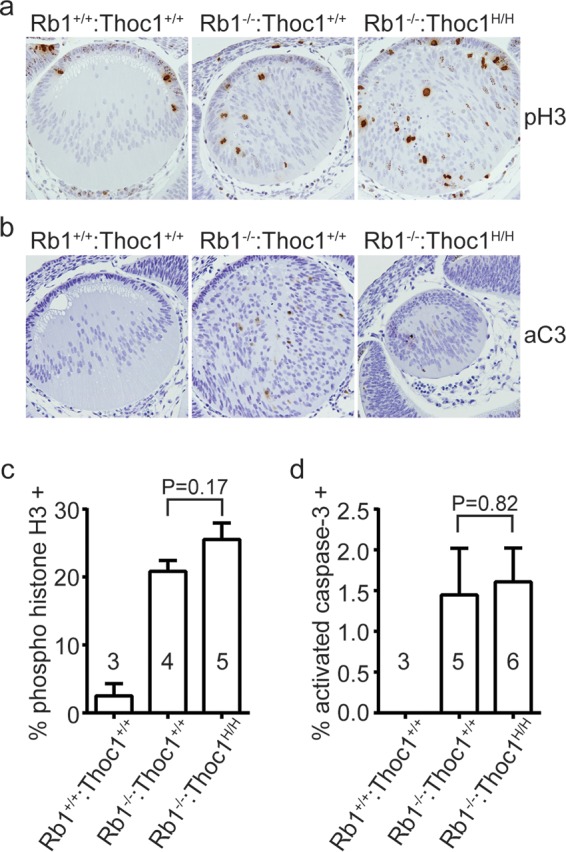

We examined the eye lenses of E13.5 embryos to test whether suppression of apoptosis is unique to the brain or a general consequence of Thoc1 deficiency. Ectopic cell proliferation and apoptosis disrupt the normal development of the eye lens in mid-gestation Rb1−/− embryos, and this defect appears to be cell autonomous (33). The eye lenses of both Rb1−/− and Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H embryos exhibit increased lens fiber cell numbers and spatial disorganization (Fig. 6a). The percentage of dividing cells is increased similarly in both genotypes relative to that in the wild type (Fig. 6a and c). Wild-type eye lenses lack detectable apoptotic cells, but they are readily detectable in both Rb1−/− and Rb1−/−:Thoc1H/H embryos (Fig. 6b). The percentages of activated caspase-3 immunopositive cells are similar in embryos of the two genotypes (Fig. 6d). Thus, Thoc1 deficiency does not suppress ectopic cell proliferation or apoptosis caused by Rb1 loss in the eye lens.

FIG 6.

Phenotypes associated with Rb1 loss in the eye lens. (a) Eye sections from E13.5 embryos of the genotypes indicated were immunostained for the cell proliferation marker phosphorylated histone 3 (pH3). Representative sections imaged by bright-field microscopy with a 20× objective are shown. Note the cellular disorganization. (b) Eye sections immunostained with the apoptosis marker activated caspase 3 (aC3). (c) The fraction of cells staining positive for pH3 was measured in E13.5 embryos of the genotypes indicated. The graph shows the mean values and standard errors, and sample sizes are shown in or near the bars. The P value derived with the Student t test by comparing the genotypes indicated is shown. (d) The fraction of cells immunopositive for activated aC3 was measured and graphed as described above.

Results presented here demonstrate that Thoc1 mediates some developmental phenotypes caused by Rb1 loss in the mouse embryo. The requirement for Thoc1 is context dependent (apoptosis versus cell proliferation) and tissue specific (brain versus eye lens). Given the known role of the THO complex in RNA processing and transport, we suggest that high Thoc1 levels are required to support the increased expression of E2f and other proapoptotic genes that occurs upon Rb1 loss in the brain. Thoc1 deficiency causes the reduced expression of these genes, thus reducing apoptosis. These effects are likely to be cell autonomous because Thoc1 deficiency does not rescue placental transport defects, the cell nonautonomous proximal trigger for brain apoptosis. The genetic interaction between Rb1 and Thoc1 detected here suggests that Rb1 inhibits the THO ribonucleoprotein complex, implicating the RbN protein interaction domain in Rb1-mediated regulation of ribonucleoprotein biogenesis and RNA transport. It remains a formal possibility, however, that the genetic interaction detected is indirect and independent of Rb1-Thoc1 binding. Thus, additional work to discover how Rb1 binding affects THO ribonucleoprotein complex activity is required to validate this hypothesis. The hypothesis may help explain why naturally occurring missense mutations in RbN cause retinoblastoma in some human patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Madeline Hanford and Aaron Burberry for expert technical assistance. Ellen Karasik assisted with tissue processing and histology. We thank members of the RPCI writing group for helpful comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA125665 and RO1 CA70292 to D.W.G.) and the University at Buffalo Mark Diamond Fund (F-09-02 to M.C.). Core facilities utilized in this work were supported by National Cancer Institute grant P30 CA016056.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burkhart DL, Sage J. 2008. Cellular mechanisms of tumour suppression by the retinoblastoma gene. Nat Rev Cancer 8:671–682. doi: 10.1038/nrc2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacks T, Fazeli A, Schmitt EM, Bronson RT, Goodell MA, Weinberg RA. 1992. Effects of an Rb mutation in the mouse. Nature 359:295–300. doi: 10.1038/359295a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke AR, Maandag ER, van Roon M, van der Lugt NM, van der Valk M, Hooper ML, Berns A, te Riele H. 1992. Requirement for a functional Rb-1 gene in murine development. Nature 359:328–330. doi: 10.1038/359328a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee EY, Chang CY, Hu N, Wang YC, Lai CC, Herrup K, Lee WH. 1992. Mice deficient for Rb are nonviable and show defects in neurogenesis and haematopoiesis. Nature 359:288–294. doi: 10.1038/359288a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manning AL, Dyson NJ. 2012. RB: mitotic implications of a tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Cancer 12:220–226. doi: 10.1038/nrc3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chinnam M, Goodrich DW. 2011. RB1, development, and cancer. Curr Top Dev Biol 94:129–169. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380916-2.00005-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viatour P, Sage J. 2011. Newly identified aspects of tumor suppression by RB. Dis Model Mech 4:581–585. doi: 10.1242/dmm.008060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicolay BN, Dyson NJ. 2013. The multiple connections between pRB and cell metabolism. Curr Opin Cell Biol 25:735–740. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hassler M, Singh S, Yue WW, Luczynski M, Lakbir R, Sanchez-Sanchez F, Bader T, Pearl LH, Mittnacht S. 2007. Crystal structure of the retinoblastoma protein N domain provides insight into tumor suppression, ligand interaction, and holoprotein architecture. Mol Cell 28:371–385. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodrich DW. 2003. How the other half lives, the amino-terminal domain of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein. J Cell Physiol 197:169–180. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riley DJ, Liu CY, Lee WH. 1997. Mutations of N-terminal regions render the retinoblastoma protein insufficient for functions in development and tumor suppression. Mol Cell Biol 17:7342–7352. doi: 10.1128/MCB.17.12.7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durfee T, Mancini MA, Jones D, Elledge SJ, Lee WH. 1994. The amino-terminal region of the retinoblastoma gene product binds a novel nuclear matrix protein that co-localizes to centers for RNA processing. J Cell Biol 127:609–622. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y, Wang X, Zhang X, Goodrich DW. 2005. Human hHpr1/p84/Thoc1 regulates transcriptional elongation and physically links RNA polymerase II and RNA processing factors. Mol Cell Biol 25:4023–4033. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.10.4023-4033.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo S, Hakimi MA, Baillat D, Chen X, Farber MJ, Klein-Szanto AJP, Cooch NS, Godwin AK, Shiekhattar R. 2005. Linking transcriptional elongation and messenger RNA export to metastatic breast cancers. Cancer Res 65:3011–3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masuda S, Das R, Cheng H, Hurt E, Dorman N, Reed R. 2005. Recruitment of the human TREX complex to mRNA during splicing. Genes Dev 19:1512–1517. doi: 10.1101/gad.1302205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strässer K, Masuda S, Mason P, Pfannstiel J, Oppizzi M, Rodriguez-Navarro S, Rondon AG, Aguilera A, Struhl K, Reed R, Hurt E. 2002. TREX is a conserved complex coupling transcription with messenger RNA export. Nature 417:304–308. doi: 10.1038/nature746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, Chang Y, Li Y, Zhang X, Goodrich DW. 2006. Thoc1/Hpr1/p84 is essential for early embryonic development in the mouse. Mol Cell Biol 26:4362–4367. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02163-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Chinnam M, Wang J, Wang Y, Zhang X, Marcon E, Moens P, Goodrich DW. 2009. Thoc1 deficiency compromises gene expression necessary for normal testis development in the mouse. Mol Cell Biol 29:2794–2803. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01633-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitzonka L, Ullas S, Chinnam M, Povinelli BJ, Fisher DT, Golding M, Appenheimer MM, Nemeth MJ, Evans S, Goodrich DW. 2014. The Thoc1 encoded ribonucleoprotein is required for myeloid progenitor cell homeostasis in the adult mouse. PLoS One 9:e97628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pitzonka L, Wang X, Ullas S, Wolff DW, Wang Y, Goodrich DW. 2013. The THO ribonucleoprotein complex is required for stem cell homeostasis in the adult mouse small intestine. Mol Cell Biol 33:3505–3514. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00751-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X, Li Y, Zhang X, Goodrich DW. 2007. An allelic series for studying the mouse Thoc1 gene. Genesis 45:32–37. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bignon YJ, Chen Y, Chang CY, Riley DJ, Windle JJ, Mellon PL, Lee WH. 1993. Expression of a retinoblastoma transgene results in dwarf mice. Genes Dev 7:1654–1662. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.9.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chinnam M, Wang Y, Zhang X, Gold DL, Khoury T, Nikitin AY, Foster BA, Li Y, Bshara W, Morrison CD, Payne Ondracek RD, Mohler JL, Goodrich DW. 2014. The Thoc1 ribonucleoprotein and prostate cancer progression. J Natl Cancer Inst 106:dju306. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang J, Li Y, Khoury T, Alrawi S, Goodrich DW, Tan D. 2008. Relationships of hHpr1/p84/Thoc1 expression to clinicopathologic characteristics and prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Clin Lab Sci 38:105–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaspar C, Cardoso J, Franken P, Molenaar L, Morreau H, Moslein G, Sampson J, Boer JM, de Menezes RX, Fodde R. 2008. Cross-species comparison of human and mouse intestinal polyps reveals conserved mechanisms in adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)-driven tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol 172:1363–1380. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Domínguez-Sánchez MS, Saez C, Japon MA, Aguilera A, Luna R. 2011. Differential expression of THOC1 and ALY mRNP biogenesis/export factors in human cancers. BMC Cancer 11:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu C, Yue B, Yuan C, Zhao S, Fang C, Yu Y, Yan D. 2015. Elevated expression of Thoc1 is associated with aggressive phenotype and poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 468:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.10.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laird PW, Zijderveld A, Linders K, Rudnicki MA, Jaenisch R, Berns A. 1991. Simplified mammalian DNA isolation procedure. Nucleic Acids Res 19:4293. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.15.4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. 1957. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrison WR, Smith LM. 1964. Preparation of fatty acid methyl esters and dimethylacetals from lipids with boron fluoride-methanol. J Lipid Res 5:600–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wenzel PL, Wu L, de Bruin A, Chong JL, Chen WY, Dureska G, Sites E, Pan T, Sharma A, Huang K, Ridgway R, Mosaliganti K, Sharp R, Machiraju R, Saltz J, Yamamoto H, Cross JC, Robinson ML, Leone G. 2007. Rb is critical in a mammalian tissue stem cell population. Genes Dev 21:85–97. doi: 10.1101/gad.1485307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu L, de Bruin A, Saavedra HI, Starovic M, Trimboli A, Yang Y, Opavska J, Wilson P, Thompson JC, Ostrowski MC, Rosol TJ, Woollett LA, Weinstein M, Cross JC, Robinson ML, Leone G. 2003. Extra-embryonic function of Rb is essential for embryonic development and viability. Nature 421:942–947. doi: 10.1038/nature01417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Bruin A, Wu L, Saavedra HI, Wilson P, Yang Y, Rosol TJ, Weinstein M, Robinson ML, Leone G. 2003. Rb function in extraembryonic lineages suppresses apoptosis in the CNS of Rb-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:6546–6551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031853100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun H, Chang Y, Schweers B, Dyer MA, Zhang X, Hayward SW, Goodrich DW. 2006. An E2F binding-deficient Rb1 protein partially rescues developmental defects associated with Rb1 nullizygosity. Mol Cell Biol 26:1527–1537. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.4.1527-1537.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spike BT, Dirlam A, Dibling BC, Marvin J, Williams BO, Jacks T, Macleod KF. 2004. The Rb tumor suppressor is required for stress erythropoiesis. EMBO J 23:4319–4329. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saavedra HI, Wu L, de Bruin A, Timmers C, Rosol TJ, Weinstein M, Robinson ML, Leone G. 2002. Specificity of E2F1, E2F2, and E2F3 in mediating phenotypes induced by loss of Rb. Cell Growth Differ 13:215–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai KY, Hu Y, Macleod KF, Crowley D, Yamasaki L, Jacks T. 1998. Mutation of E2f-1 suppresses apoptosis and inappropriate S phase entry and extends survival of Rb-deficient mouse embryos. Mol Cell 2:293–304. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80274-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ziebold U, Reza T, Caron A, Lees JA. 2001. E2F3 contributes both to the inappropriate proliferation and to the apoptosis arising in Rb mutant embryos. Genes Dev 15:386–391. doi: 10.1101/gad.858801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stanelle J, Putzer BM. 2006. E2F1-induced apoptosis: turning killers into therapeutics. Trends Mol Med 12:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Polager S, Ginsberg D. 2009. p53 and E2f: partners in life and death. Nat Rev Cancer 9:738–748. doi: 10.1038/nrc2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen D, Pacal M, Wenzel P, Knoepfler PS, Leone G, Bremner R. 2009. Division and apoptosis of E2f-deficient retinal progenitors. Nature 462:925–929. doi: 10.1038/nature08544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]