Abstract

Background

This study was designed to improve our understanding of the role of miR-18a and its target (connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), which are mediators in HBX-induced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Material/Methods

We first investigated the expression of several candidate microRNAs (miRNAs) reported to have been aberrantly expressed between HepG2 and HepG2.2.15, which is characterized by stable HBV infection, while the CTGF is identified as a target of miR-18a. Furthermore, the expression of CTGF evaluated in HepG2 was transfected with HBX, while the HepG2.2.15 was transfected with miR-18a and CTGF siRNA. We examined the cell cycle at the same time.

Results

We found that the expression of miR-18a was abnormally reduced in the HBV-positive HCC tissue samples compared with HBV-negative HCC samples. Through the use of a luciferase reporter system, we also identified CTGF 3′UTR (1046–1052 bp) as the exact binding site for miR-18a. We also observed a clear increase in CTGF mRNA and protein expression levels in HBV-positive HCC human tissue samples in comparison with the HBV-negative controls, indicating a possible negatively associated relationship between miR-18a and CTGF. Furthermore, we investigated the effect of HBX overexpression on miR-18a and CTGF, as well as the viability and cell cycle status of HepG2 cells. In addition, we found that HBX introduction downregulated miR-18a, upregulated CTGF, elevated the viability, and promoted cell cycle progression. We transfected HepG2.2.15 with miR-18a mimics and CTGF siRNA, finding that upregulated miR-18a and downregulated CTGF suppress the viability and cause cell cycle arrest.

Conclusions

Our study shows the role of the CTGF gene as a target of miR-18a, and identifies the function of HBV/HBX/miR-18a/CTGF as a key signaling pathway mediating HBV infection-induced HCC.

MeSH Keywords: Carcinoma, Hepatocellular; Connective Tissue Growth Factor; MicroRNAs

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranks among the most common malignancies all over the world. As the major etiological factor for HCC, chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) contributes to 80% of all HCC cases in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia; moreover, it contributes 55% of the global incidence [1]. Despite the strong correlation between HCC and HBV infection, which has been supported by epidemiological evidence [1], the mechanisms through which HBV leads to carcinogenesis remain largely unknown.

Critical for replication of hepatitis B virus in vivo, hepatitis B virus-encoded X (HBX) protein has been shown by molecular studies to play an important role in hepatocarcinogenesis [2,3]. The increasing evidence suggests that the HBx protein interrupts the normal physiological mechanisms of host cells, thereby promoting hepatocarcinogenesis. For instance, the HBx protein can modulate the p53’s transcriptional activation to disrupt repair mechanism of DNA and the apoptotic process of liver cells [4,5]. Moreover, HBx protein can reduce the expression level of mitochondrial enzymes that transport electrons for oxidative phosphorylation; after that, it upregulates the production of lipid peroxide and oxygen species, which are harmful at high levels; consequently, mitochondrial injury may be caused [6,7].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a group of small noncoding RNA molecules that can bind the 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs) of target mRNAs preferentially so as to inhibit gene expression [8]. These interactions may lead to either degradation of the targeted mRNAs or inhibition of their translation. MiRNAs can also regulate numerous cellular processes, such as apoptosis, differentiation, and proliferation [9]. Working as either tumor suppressors or oncogenes, miRNAs can suppress the gene expression of key proteins engaged in the progression and development of cancer [10]. Thus, miRNAs may be functionally involved in the control of many cancer-related signaling pathways, such as the mTOR signaling pathway [11]. In terms of viral infections, it causes approximately 10–15% of malignancies [12]. Cervical cancer is believed to be caused by human papilloma virus (HPV) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which resulted from the persistent infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B virus (HBV) (12). Recently, the expression level of miRNA has been reported to be interrupted by virus infection [13]. For instance, Zhang et al. reported that miRNA expression profile was altered in patients with HBV-positive HCC [14]. Patients with chronic HBV infection share a similar miRNA expression profile with patients infected with HCC, while patients infected with acute HBV have a different miRNA expression profile. This indicates that altered miRNAs in chronic HBV infection can contribute to HCC tumorigenesis [14].

Peng et al. determined and compared HepG2 (HBV-negative tumor cell line) and HepG2.2.15 (HBV-positive tumor cell line) in terms of the expression profiling. They identified the differential expression of several miRNAs by using miRNA microarray analysis [15]. In this study, we collected 32 HBV-positive HCC samples and 28 HBV-negative samples. We measured the candidate miRNAs in those samples, finding that miR-18a is differentially expressed in those samples. HBV/HBX/miR-18a/CTGF was identified as a key signaling pathway promoting HBV-induced HCC tumorigenesis.

Material and Methods

Tumor specimens and cell lines

We collected the tissues from 60 hepatocellular carcinoma patients provided by surgical resection (32 HBV-positive cases and 28 HBV-negative cases) at the Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Affiliated Hospital of Henan Medical College (Luoyang, China). Before the surgery, no patient received any medical treatment. As for the HBV surface antigen, HBsAg, it was tested and found to be positive. However, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was tested to be negative in all patients. This work was approved by the Ethics Committee of Henan Medical College. We strictly obeyed the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) of the World Medical Association in this work, and received informed consent from all patients prior to recruitment.

Cell culture, synthetic miRNAs and siRNA, oligo transfection miR-18a mimics, and CTGF siRNA were synthesized by Genepharma (Shanghai, China). Supplemented with 1% streptomycin/ penicillin and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, California, USA) was used to culture HepG2.2.15 and HepG2 cell lines purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). A humidified incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rockford, IL) with 5% CO2 was used to keep the cells at 37°C. We seeded the cells into growth medium without antibiotic in 6-well plates at a density of 3×105 cells/well 24 h before the transfection. When the confluence reached 80%, we transfected the cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in accordance with the protocol of the manufacturer. Four hours later, we changed the growth medium and isolated the total cellular protein or RNA for further experiments. PEGFP-HBx was used to transfect the HepG2 cells, and pEGFP empty vector was used as a control. Western blot analysis was used to verify the overexpression of HBX.

miRNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

The miRNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hamburg, German) was used to extract total RNA, including miRNA from cell lines or tissues. The miScript Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen, Hamburg, German) was used to reversely transcribe target miRNA (miR-122, miR-143, miR-124, miR-210, miR-345, miR-148a, and miR-18a) while CTGF mRNA was used to reversely transcribe target cDNA. A MiScript SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen, Hamburg, Germany) was used to determine the miRNAs or the mRNA expression of cell lines or tissues with the ABI 7000 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA) following the instruction provided by the manufacturer. Comparative threshold methods (2−ΔΔCt) were utilized to calculate the relative quantification value of the target miRNAs or mRNA, which was then normalized to a control.

Protein preparation and Western blot analyses

The cells and tissues were lysed in lysis buffer (Biosharp, Hefei, China) containing 5 g/l sodium deoxycholate, 10 ml/l NP-40, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 100 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.1 g/lSDS, 0.2 g/l NaN3, 150 mmol NaCl, and 50 mmol Tris-HCl (pH 8.5). Lysates were cleared of cell debris by centrifugation at 20 800×g for 15 min at 4°. The Bradford method was used to determine the concentrations of protein, while at the same time a total of 30–50 μg proteins were loaded on a 12% polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE) and electrophoresed. Proteins were then blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). To avoid unspecific binding, the membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in Tris-buffered saline /Tween-20 (0.1%, Bioeasy, Shanghai, China) at room temperature for 2 h. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with mouse anti-β-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-47778; 1:2,000) and primary mouse monoclonal antibodies against CTGF (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-57760; 1:400) in PBS/Tween containing 2% non-fat milk at 4°C for 4 h. After the washing with TBST buffer, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary goat-anti-mouse antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, diluted 1:10,000). An enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rockford, IL) was used to visualize the bands.

Reporter gene constructs

With pGL3L (+) as a parental plasmid, the vector containing wild-type CTGF 3′UTR (pGL3L-WT-CTGF) was constructed. A site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used to introduce the mutations so as to replace the putative binding site in the 3′UTR of CTGF.

Luciferase assay

HepG2 cells were seeded 24 h before the transfection. The cells were transfected with a 50 nM concentration of miR-18a mimics through the use of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, CA), followed by cell culturing for 8 h. After replacing the medium, 50 ng of pRL-TK control (Promega, Madison, WI) and 500 ng of a reporter construct were used to co-transfect the cells with the existence of FuGENE 6 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). We changed the medium 24 h later; at 48 h after the reporter transfection, the cells were lysed in a passive lysis buffer (Promega, Fitchburg, WI). The Dual Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Fitchburg, WI) was used to analyze the cell lysate directly.

Flow cytometry

Two milliliters of 1×105/mL HepG2 and HepG2.2.15 cells were seeded in 6-well plates with 12% FBS-DMEM and incubated for 12 h. After that, 0.25% trypsin was used to trypsinize the cells before washing in PBS. PBS was used to resuspend the cells at 1×106 cells/mL. After fixing the cells with 75% ethanol overnight, a solution containing 0.2 mg/mL RNAse, 0.1% Triton X-100/0.1% sodium citrate, and 0.1 mg/mL propidium iodide was used to stain the cells in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. Flow cytometry was performed at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm to analyze the cellular DNA content after cells were stained with propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) was used to analyzing the cells distributed in the 3 major phases of the cell cycle (G2/M, S, G0/G1).

CCK-8 assay

Cell proliferation was measured by the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. Briefly, 24 h after seeding equal numbers of HepG2.2.15 or HepG2, the cells were transfected with the miR-18a mimics, CTGF siRNA, HBX-overexpressing vector, or the control. After transfection, DMEM was used to incubate the cells, and 10 μl of the CCK-8 solution was added to each well, and the cells were cultured for 2 h at the end of the treatment. After that, measurement was conducted on the absorbance value at 450 nm with a microplate (Bio-Tek Instruments Inc, Winooski, VT) absorbance reader to confirm the number of viable cells.

Statistical analysis

Mann-Whitney U test, 2-tailed Student’s t test, or χ2 analysis was used to assess different variables between groups. SPSS 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used to perform statistical analysis, and P<0.05 was considered to be statistical significance.

Results

Expression of miR-18a decreased in HBV-positive HCC samples

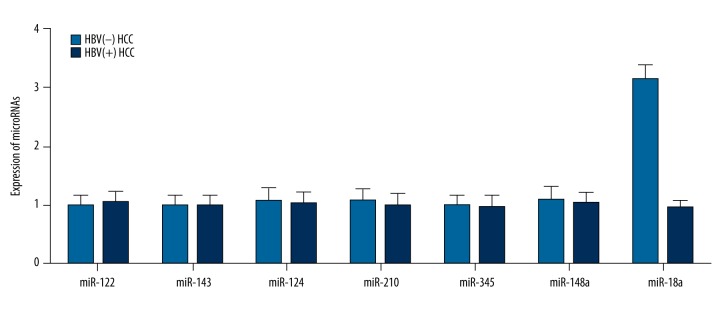

To identify the miRNA and its target gene(s) that mediate the oncogenic effect of HBV in the development of HCC, we performed real-time PCR in tumor tissue samples collected from HBV-positive and HBV-negative patients to screen the candidate miRNAs. These miRNAs were previously reported to be differentially expressed between HepG2 and HepG2.2.15, including miR-122, miR-143, miR-124, miR-210, miR-345, miR-148a, and miR-18a (R1). As shown in Figure 1, miR-18a was significantly upregulated in HBV-negative HCC samples compared with the HBV-positive HCC samples, and all other miRNAs showed comparable expression between the 2 groups.

Figure 1.

Expression of miR-18a was downregulated in HBV-positive tissue samples compared with HBV-negative tissue samples, while other miRNAs, including miR-122, miR-143, miR-122, miR-210, miR-345 and miR-148a, showed no apparent differences.

CTGF was a target of miR-18a

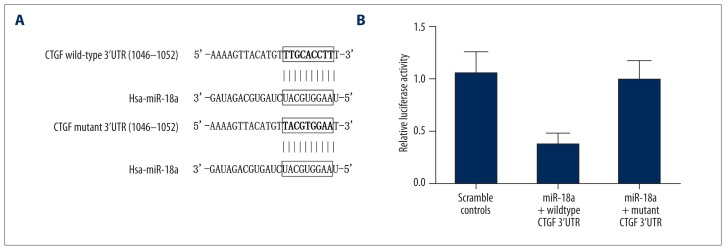

Because of the substantial down-regulation of miR-18a in HBV-positive HCC human tissue samples, we hypothesized that miR-18a might interfere with the development of HCC via targeting 1 or more oncogenes. To test this, we used publicly available miRNA target prediction tools and established CTGF as a potential target of miR-18a for the optimal matching between mature miR-18a and 3′UTR of the gene (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) CTGF was identified as the target of miR-18a, with its possible binding region CTGF 3′UTR and its mutant. (B) Relative luciferase activity of cells treated with constructs containing wild-type CTGF 3′UTR segments was significantly lower compared with the negative controls, while that of cells treated with constructs containing mutant CTGF 3′UTR segments was merely different compared with the negative controls.

To verify CTGF as the direct target of miR-18a, we used luciferase reporter assay among miR-18a-treated cells transfected with wild-type CTGF 3′UTR constructs and mutant CTGF 3′UTR constructs, respectively. Results (Figure 2B) showed that the relative luciferase activity of cells transfected with wild-type CTGF 3′UTR constructs was significantly lower than that of the scramble controls, while cells transfected with mutant CTGF 3′UTR constructs showed more difference compared with scramble controls. The results showed that CTGF is the direct target of miR-18a, and site 1046–1052 is the exact binding site of miR-18a.

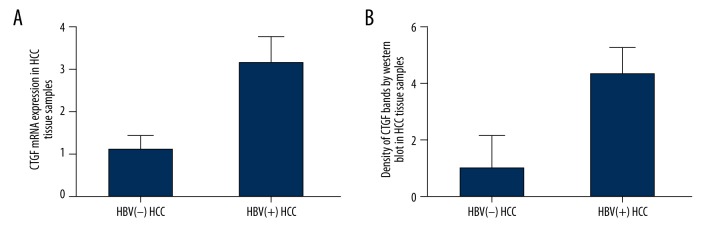

Possible negatively related association between miR-18a and CTGF

To investigate the effect of miR-18a upon CTGF in HCC tissue samples, we also examined the mRNA and protein expression level of CTGF via qRT-PCR and Western blot analysis among HBV-negative and HBV-positive HCC samples. As shown in Figure 3A, the CTGF mRNA expression level of HBV-negative HCC samples was significantly lower than that of HBV-positive HCC samples. The CTGF protein expression level of HBV-negative HCC samples also exhibited similar downregulation in comparison with the HBV-positive HCC samples (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) Expression level of CTGF mRNA in HBV-positive HCC tissue samples was upregulated compared with the HBV-negative tissue samples. (B) Expression level of CTGF protein in HBV-positive HCC tissue samples was upregulated compared with the HBV-negative tissue samples.

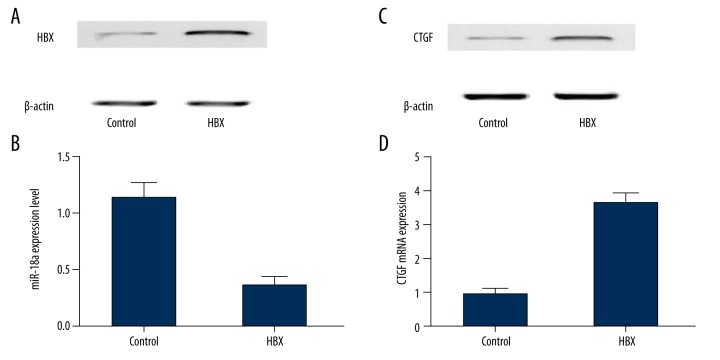

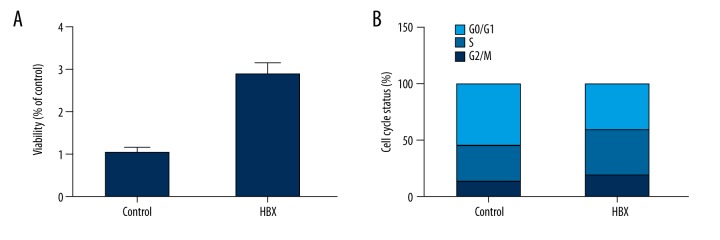

HBX introduction reduced the expression of miR-18a/CTGF and enhanced cell proliferation by promoting cell cycle progression in HepG2 cells

To evaluate the effect of HBX upon the expression of miR-18a and CTGF, we transfected HepG2 cells with constructs carrying HBX or the empty vector. Subsequently, the mRNA or protein expression levels of miR-18a and CTGF were determined with the presence of HBX. As shown in Figure 4, expression of miR-18a (Figure 4A) was inhibited in HepG2 cells overexpressing HBX (Figure 4B) compared with the controls. Subsequently, protein and mRNA expression levels of CTGF all showed a clear increase in the presence of HBX compared with controls.

Figure 4.

(A) Western blot analysis of HBX in HBX-expressing cells compared with the controls. (B) Expression level of miR-18a was inhibited by the presence of HBX compared with the controls. (C) Protein expression level of CTGF was higher among HBX-expressing cells compared with the controls. (D) The mRNA expression of CTGF was upregulated in the presence of HBX compared with the controls.

Additionally, we investigated cell viability and cell cycle status of HBX over-expressing HepG2 cells as compared with the empty vector-transfected control cells. In comparison with the controls, relative cell viability of the HepG2 cells transfected with constructs carrying HBX showed a substantial decrease in viability (Figure 5A). To further explore the underlying molecular mechanism, flow cytometry analysis was conducted and the G2/M and S phase fraction were found to increase from 13.18% to 19.91%, and from 32.09% to 40.09%, respectively. G0/G1 decreased from 54.73% to 41% with the overexpression of HBX (Figure 5B). These findings indicate that the introduction of HBX expression can enhance the proliferation of the HepG2 cells by promoting cell cycle progression.

Figure 5.

(A) Viability of HBX-expressing cells increased when compared with the controls. (B) Cell cycle status of HBX-expressing cells in phase G0, S, and G2/M compared with the controls.

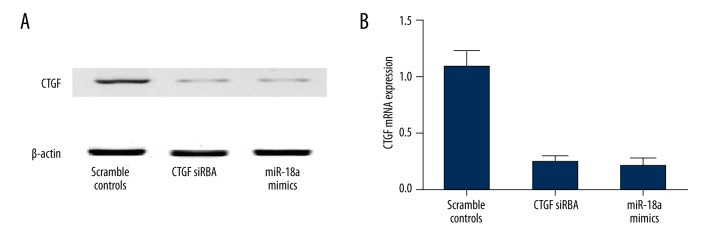

Transfection of miR-18a inhibited the expression of CTGF and suppressed the proliferation of HepG2.2.15 cells

We conducted qRT-PCR and Western blot analysis to investigate the mRNA and protein expression of CTGF in HepG2.2.15 cells transfected with miR-18a mimics or CTGF siRNA. As shown in Figure 6A, compared with the scramble controls, protein expression of miR-18a mimics-treated cells and CTGF siRNA-treated cells similarly decreased, and a similar change in the mRNA expression of CTGF was detected in those cells (Figure 6B). The above findings validate that miR-18a can inhibit the mRNA and protein expression of CTGF.

Figure 6.

(A) CTGF protein expression level of cells treated with miR-18a mimics and CTGF siRNA were equally low when compared with the scramble controls. (B) CTGF mRNA expression level of cells treated with miR-18a mimics and CTGF siRNA were equally low when compared with the scramble controls.

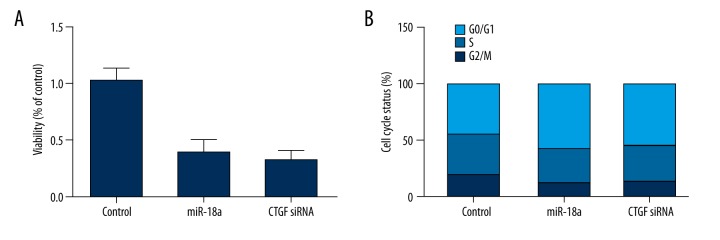

To further explore the underlying mechanism, we also investigated the cell viability of cell cycle fraction in treatment groups. Cell viability of both treatment groups was much lower in HepG2.2.15 cells transfected with miR-18a mimics or CTGF siRNA compared with the scramble controls (Figure 7A). Moreover, the cell cycle distribution analysis results (Figure 7B) showed a boost in G0 phase of the miR-18a mimics-treated group from 44.76% to 57.66%, along with a decreased proportion of G2/M and S phase cells from 19.12% to 12.09% and 36.12% to 30.25%, respectively. Similarly, transfection of CTGF siRNA also inhibited the G2/M and S fraction (19.12% to 13.54% and 36.12% to 31.23%, respectively) and G0/G1 fraction increased from 44.76% to 55.23%.

Figure 7.

(A) Viability of cells treated with miR-18a mimics and CTGF siRNA showed similar low levels compared with the scramble controls. (B) Cell cycle status of cells treated with miR-18a mimics and CTGF siRNA in phase G0, S, and G2/M compared with the scramble controls.

Discussion

In this study we found that the expression of miR-18a was abnormally reduced in the HBV-positive HCC tissue samples compared with that in HBV-negative HCC samples. Using the luciferase reporter system, we also identified CTGF 3′UTR (1046–1052 bp) as the exact binding site for miR-18a. There was a clear increase in CTGF mRNA and protein expression levels in HBV-positive HCC human tissue samples compared to the HBV-negative controls, suggesting negatively associated relationship between miR-18a and CTGF. A relevant investigation was conducted on the effect of HBX overexpression on miR-18a and CTGF, as well as the viability and cell cycle status of HepG2 cells. We found that HBX introduction downregulated miR-18a, upregulated CTGF, elevated the viability, and promoted cell cycle progression. Furthermore, we transfected HepG2.2.15 with miR-18a mimics and CTGF siRNA, finding that they can upregulate miR-18a, downregulate CTGF, suppress viability, and cause cell cycle arrest.

Influencing target gene expression in an inheritable way, non-coding RNAs include long RNAs (lncRNAs) with more than 200 nucleotides and short microRNAs(miRNAs), in which less than 22 nucleotides have been regarded as an epigenetic regulator. Alterations in some host miRNA profiles have been noticed to be associated with HBx expression. MiRNAs whose expression could be induced were upregulated by HBx, including miRNA 602 (miR-602), miR-143, miRNA-29a, and miR-148a. As a putative tumor suppressor, miR-602 targets RASSF1A, [16]. miR-143 can promote metastasis, migration, and invasion of hepatoma cells by targeting fibronectin type III domain-containing 3B (FNDC3B) [17]. miR-148a and miRNA-29a can enhance migration of hepatoma cells by targeting tensin homolog and phosphatase (PTEN) [18,19]. MiRNAs whose expression can be induced were downregulated by HBx, including miR-661, miR-373, and let-7a. miR-661 is related to tumor metastasis by targeting MTA1 [20]; miR-373 mediates proper adhesion of cell to cell by targeting CDH1 [21]; and let-7a supports proliferation of cells by targeting signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) [22]. The correlation between miRNAs and HBx involves the process by which HBx regulates expression of genes, possibly through mechanisms of epigenetic control related to miRNA [23].

MiR-18a is a member of the miR-17~92 cluster. It is generally accepted that the miR-17~92 cluster functions as an oncogene in its own right [24,25] or as a key downstream effector of the Myc family of onco-proteins, such as c- and N-Myc [26,27]. miR-17~92 contributes to various aspects of cancer initiation and progression [28]. For example, our laboratory has demonstrated that miR-17~92 augments tumor angiogenesis in the KRAS-driven colon carcinoma model [27], despite the fact that it has a cell-intrinsic anti-angiogenic function in endothelial cells [29]. In the colon cancer model, induction of angiogenesis is accompanied by down-regulation of several anti-angiogenic members of the TSR super family, including thrombospondin-1 and clusterin [30]. TSR proteins in solid tumors are targeted by both miR-18 and miR-19. In B-lymphoid malignancies, the key oncogenic component of miR-17~92 is miR-19 [31], acting primarily through the PTEN pathway. In this study we found that miR-18a was significantly upregulated in HBV-negative HCC samples compared with the HBV-positive HCC samples, and we validated CTGF as a target of miR-18a by using luciferase assay. In line with this, we also found that CTGF mRNA and protein expression level of HBV-negative HCC samples was significantly lower than that of HBV-positive HCC samples.

As a member of the CCN family, CTGF acts as a growth factor through binding with integrins expressed on the surface of cells. CTGF demonstrates a large range of functions in vivo, such as angiogenesis, migration, and proliferation [32]. Interestingly, in a variety of cancer types, CTGF works as an oncogene while in other cancer types it is identified as a tumor-suppressor gene. The overexpression of CTGF has been shown to be related to the progression of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia [33], glioblastoma [34], esophageal adenocarcinoma [35], pancreatic cancer [36], and HCC [37]. The suppression of metastasis is also related to overexpression of CTGF. In colorectal cancer [38], lung adenocarcinoma [39], and gallbladder cancer [40], CTGF act as the favorable prognostic marker. We found that downregulation of miRNA in HCC patients was related to overexpression of intratumoral CTGF. We also found evidence corresponding to previous studies showing that differential expression miRNA in breast cancer patients is related to overexpression of CTGF, and CTGF might be a biomarker specific to BM [41]. In this study, we found that the expression of miR-18a was inhibited in HepG2 cells overexpressing HBX in comparison with the controls. The G2/M and S phase fraction were found to be increased from 13.18% to 19.91% and 32.09% to 40.09%, respectively, while G0/G1 decreased from 54.73% to 41% with the overexpression of HBX. In HepG2.2.15 cells, protein expression of miR-18a mimics-treated cells and CTGF siRNA-treated cells were similarly decreased compared with the scramble controls. Along with a boost in G0 phase of miR-18a mimics treatment group from 44.76% to 57.66%, there was a decreased proportion of G2/M and S phase cells from 19.12% to 12.09% and 36.12% to 30.25%, respectively. Similarly, transfection of CTGF siRNA also inhibited the G2/M and S fraction (19.12% to 13.54% and 36.12% to 31.23%, respectively), while the G0/G1 fraction increased from 44.76% to 55.23%.

Conclusions

Taken together, we discovered that HBx down-regulated Gld2, which led to reduced expression level of miR-122 in cells infected by HBV. This process is part of post-transcriptional regulation. Therefore, a new mechanism is put forward in this study to explain how HBV affects miRNA expression.

Footnotes

conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Kew MC. Epidemiology of chronic hepatitis B virus infection, hepatocellular carcinoma, and hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Biol. 2010;58(4):273–77. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen HS, Kaneko S, Girones R, et al. The woodchuck hepatitis virus X gene is important for establishment of virus infection in woodchucks. J Virol. 1993;67(3):1218–26. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1218-1226.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zoulim F, Saputelli J, Seeger C. Woodchuck hepatitis virus X protein is required for viral infection in vivo. J Virol. 1994;68(3):2026–30. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.2026-2030.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chirillo P, Pagano S, Natoli G, et al. The hepatitis B virus X gene induces p53-mediated programmed cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(15):8162–67. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee AT, Ren J, Wong ET, et al. The hepatitis B virus X protein sensitizes HepG2 cells to UV light-induced DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(39):33525–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506628200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee YI, Hwang JM, Im JH, et al. Human hepatitis B virus-X protein alters mitochondrial function and physiology in human liver cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(15):15460–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309280200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takada S, Shirakata Y, Kaneniwa N, Koike K. Association of hepatitis B virus X protein with mitochondria causes mitochondrial aggregation at the nuclear periphery, leading to cell death. Oncogene. 1999;18(50):6965–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116(2):281–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(10):704–14. doi: 10.1038/nrg2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang B, Pan X, Cobb GP, Anderson TA. microRNAs as oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Dev Biol. 2007;302(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. Defining the role of mTOR in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12(1):9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore PS, Chang Y. Why do viruses cause cancer? Highlights of the first century of human tumour virology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(12):878–89. doi: 10.1038/nrc2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin Z, Flemington EK. miRNAs in the pathogenesis of oncogenic human viruses. Cancer Lett. 2011;305(2):186–99. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang ZZ, Liu X, Wang DQ, et al. Hepatitis B virus and hepatocellular carcinoma at the miRNA level. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(28):3353–58. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i28.3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng F, Xiao X, Jiang Y, et al. HBx down-regulated Gld2 plays a critical role in HBV-related dysregulation of miR-122. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang L, Ma Z, Wang D, et al. MicroRNA-602 regulating tumor suppressive gene RASSF1A is overexpressed in hepatitis B virus-infected liver and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9(10):803–8. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.10.11440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, Liu S, Hu T, et al. Up-regulated microRNA-143 transcribed by nuclear factor kappa B enhances hepatocarcinoma metastasis by repressing fibronectin expression. Hepatology. 2009;50(2):490–99. doi: 10.1002/hep.23008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong G, Zhang J, Zhang S, et al. Upregulated microRNA-29a by hepatitis B virus X protein enhances hepatoma cell migration by targeting PTEN in cell culture model. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan K, Lian Z, Sun B, et al. Role of miR-148a in hepatitis B associated hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bui-Nguyen TM, Pakala SB, Sirigiri DR, et al. Stimulation of inducible nitric oxide by hepatitis B virus transactivator protein HBx requires MTA1 coregulator. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(10):6980–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 21.Place RF, Li LC, Pookot D, et al. MicroRNA-373 induces expression of genes with complementary promoter sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(5):1608–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707594105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Lu Y, Toh ST, et al. Lethal-7 is down-regulated by the hepatitis B virus x protein and targets signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. J Hepatol. 2010;53(1):57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arzumanyan A, Friedman T, Kotei E, et al. Epigenetic repression of E-cadherin expression by hepatitis B virus x antigen in liver cancer. Oncogene. 2012;31(5):563–72. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petrocca F, Visone R, Onelli MR, et al. E2F1-regulated microRNAs impair TGFbeta-dependent cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in gastric cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(3):272–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He L, Thomson JM, Hemann MT, et al. A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature. 2005;435(7043):828–33. doi: 10.1038/nature03552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chayka O, Corvetta D, Dews M, et al. Clusterin, a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor gene in neuroblastomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(9):663–77. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dews M, Homayouni A, Yu D, et al. Augmentation of tumor angiogenesis by a Myc-activated microRNA cluster. Nat Genet. 2006;38(9):1060–65. doi: 10.1038/ng1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendell JT. miRiad roles for the miR-17-92 cluster in development and disease. Cell. 2008;133(2):217–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doebele C, Bonauer A, Fischer A, et al. Members of the microRNA-17-92 cluster exhibit a cell-intrinsic antiangiogenic function in endothelial cells. Blood. 2010;115(23):4944–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-264812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dews M, Fox JL, Hultine S, et al. The myc-miR-17~92 axis blunts TGF{beta} signaling and production of multiple TGF{beta}-dependent antiangiogenic factors. Cancer Res. 2010;70(20):8233–46. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olive V, Bennett MJ, Walker JC, et al. miR-19 is a key oncogenic component of mir-17-92. Genes Dev. 2009;23(24):2839–49. doi: 10.1101/gad.1861409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leask A, Holmes A, Abraham DJ. Connective tissue growth factor: a new and important player in the pathogenesis of fibrosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2002;4(2):136–42. doi: 10.1007/s11926-002-0009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sala-Torra O, Gundacker HM, Stirewalt DL, et al. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) expression and outcome in adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2007;109(7):3080–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-031096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie D, Yin D, Wang HJ, et al. Levels of expression of CYR61 and CTGF are prognostic for tumor progression and survival of individuals with gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(6):2072–81. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0659-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koliopanos A, Friess H, di Mola FF, et al. Connective tissue growth factor gene expression alters tumor progression in esophageal cancer. World J Surg. 2002;26(4):420–27. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0242-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bennewith KL, Huang X, Ham CM, et al. The role of tumor cell-derived connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) in pancreatic tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2009;69(3):775–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mazzocca A, Fransvea E, Dituri F, et al. Down-regulation of connective tissue growth factor by inhibition of transforming growth factor beta blocks the tumor-stroma cross-talk and tumor progression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2010;51(2):523–34. doi: 10.1002/hep.23285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin BR, Chang CC, Che TF, et al. Connective tissue growth factor inhibits metastasis and acts as an independent prognostic marker in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(1):9–23. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang CC, Shih JY, Jeng YM, et al. Connective tissue growth factor and its role in lung adenocarcinoma invasion and metastasis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(5):364–75. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fang ZQ, Zang WD, Chen R, et al. Gene expression profile and enrichment pathways in different stages of bladder cancer. Genet Mol Res. 2013;12(2):1479–89. doi: 10.4238/2013.May.6.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagpal N, Ahmad HM, Chameettachal S, et al. HIF-inducible miR-191 promotes migration in breast cancer through complex regulation of TGF-signaling in hypoxic microenvironment. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9650. doi: 10.1038/srep09650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]