Abstract

The thermophilic acetogenic bacterium Thermoanaerobacter kivui, previously described not to use carbon monoxide as a carbon and energy source, was adapted to grow on CO. This was achieved by using a preculture grown on H2 plus CO2 and by increasing the CO concentration in small, 10% increments. T. kivui was finally able to grow within a 100% CO atmosphere. Growth on CO was found in complex and mineral media, and vitamins were not required. Carbon monoxide consumption was accompanied by acetate and hydrogen production. Cells also grew on synthesis gas (syngas) with the simultaneous use of CO and H2 coupled to acetate production. CO oxidation in resting cells was coupled to hydrogen and acetate production and accompanied by the synthesis of ATP. A protonophore abolished ATP synthesis but stimulated H2 production, which is consistent with a chemiosmotic mechanism of ATP synthesis. Hydrogenase activity was highest in crude extracts of CO-grown cells, and carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH) activity was highest in H2-plus-CO2- or CO-grown cells. The genome of T. kivui harbors two CODH gene clusters, and both CODH proteins were present in crude extracts, but one CODH was more prevalent in crude extracts from CO-grown cells.

INTRODUCTION

Carbon monoxide is a colorless, odorless gas, which is toxic to most organisms in trace amounts. However, some organisms can use carbon monoxide as an electron and carbon source (1, 2). These organisms are aerobic carboxydotrophic bacteria such as Oligotropha carboxydovorans (3), phototrophic purple sulfur bacteria such as Rhodospirillum rubrum (4), hydrogenogenic bacteria and archaea such as Thermosinus carboxydivorans (5) or Thermococcus sp. strain AM4 (6), or some organisms that employ the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway (WLP), such as methanogens (7–9) or acetogens (10–13). Acetogenic bacteria use the WLP for CO2 fixation to acetate. This pathway is considered one of the most ancient biochemical pathways for CO2 fixation, as it combines two essential features: CO2 fixation and the synthesis of ATP (14, 15). The use of carbon monoxide as an electron donor for the WLP has the advantage of providing extremely low potential electrons for reducing cellular electron carriers with a CO2/CO reduction potential of −520 mV (16).

The production of third-generation biofuels from carbon dioxide, molecular hydrogen, and/or carbon monoxide as catalyzed by, for example, acetogenic bacteria is a promising alternative for existing biofuel production routes from renewable sources (17–19). However, it is still in its infancy with respect to knowledge on the biochemistry and bioenergetics of CO oxidation and CO2 reduction in many acetogens. Several acetogenic representatives have been shown to use CO as the sole energy source, such as Butyribacterium methylotrophicum (CO strain) (20), Eubacterium limosum (21), Blautia producta (22), Clostridium thermoautotrophicum (11), Moorella thermoacetica (12), and Clostridium ljungdahlii (23). The extent of CO tolerance and consumption varies greatly between different species, and some closely related bacteria cannot utilize CO as the sole energy source at all (20) or can utilize it only in combination with H2 plus CO2, as is the case, for example, for Acetobacterium woodii (24). The circumstances defining the constraint of using CO as a sole energy source are still widely unresolved.

Acetogenic bacteria use the WLP to produce acetate as a primary end product. This can be through either heterotrophic growth or autotrophic growth on H2 plus CO2 or on CO. During acetogenesis from CO2 plus H2 according to the equation

| (1) |

CO2 is reduced in the methyl branch to formate, activated to formyl-tetrahydrofolate (THF) at the cost of 1 ATP molecule, and further metabolized to methenyl-THF, which is reduced stepwise to methylene-THF and finally to methyl-THF (14). The other CO2 molecule is reduced in the carbonyl branch to CO, which is then combined with the methyl group and coenzyme A (CoA) to acetyl-CoA, catalyzed by a bifunctional carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH)/acetyl-CoA synthase (ACS). The acetyl-CoA is then converted to acetyl-phosphate and finally to acetate, giving rise to 1 ATP molecule.

Acetogenesis from carbon monoxide according to the equation

| (2) |

involves, besides the WLP, an enzyme system that is able to oxidize CO to CO2. This enzyme system can be either the above-mentioned CODH/ACS or a monofunctional CODH. The CO2 produced is then reduced in the WLP as outlined above.

Since the WLP requires the input of 1 ATP molecule for the activation of formate and gives rise to only 1 ATP molecule from substrate-level phosphorylation from the acetate kinase reaction, net energy conservation requires the generation of a chemiosmotic gradient established by a redox-driven ion pump. The gradient is then used by an ATP synthase to generate ATP. In acetogenic bacteria, this redox-driven ion pump is either an Rnf complex, as in A. woodii (25–27), or an Ech complex, as found in M. thermoacetica (28) or Thermoanaerobacter kivui (29). The coupling ions for Rnf and Ech can be either H+ or Na+.

T. kivui is a thermophilic acetogenic organism that can sustain a heterotrophic or autotrophic lifestyle with H2 plus CO2 as the substrate (30). A genetic system is available for some Thermoanaerobacter strains, making T. kivui a good candidate for a strain to be used for the production of biocommodities from CO2 at high temperatures (31, 32). Another interesting feedstock for third-generation biofuels is synthesis gas (syngas), which contains carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and molecular hydrogen in variable proportions and with trace gases whose nature depends on the source (33). Unfortunately, it was reported that T. kivui is unable to grow on carbon monoxide, which would exclude syngas as a feedstock for this bacterium (12). However, we describe here that T. kivui can be adapted to grow on CO or syngas. Not only does CO support growth as a single electron source, but CO oxidation is also coupled to energy conservation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organism and cultivation.

T. kivui LKT-1 (DSM 2030) was routinely cultivated at 60°C. The media were prepared by using anaerobic techniques as described previously (34, 35). All growth experiments were performed with 120-ml serum flasks containing 20 ml medium. Mineral medium contained 3.6 mM KH2PO4, 50 mM KHCO3, 5.4 mM KCl, 6.3 mM NH4Cl, 1.6 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 0.35 mM CaCl2·2H2O, 1.5 mM cysteine-HCl, 10 ml/liter DSM 141 vitamin solution, 10 ml/liter trace element solution (DSM 141), and 4 μM resazurin. Complex medium contained 50 mM NaH2PO4, 50 mM NaH2HPO4, 1.2 mM K2HPO4, 1.6 mM KH2PO4, 4.7 mM NH4Cl, 1.7 mM (NH4)2SO4, 7.5 mM NaCl, 0.37 mM MgSO4, 42 μM CaCl2, 7.2 μM Fe(II)SO4, 54 mM KHCO3, 3 mM cysteine-HCl, 0.2% (wt/vol) yeast extract, 10 ml/liter vitamin solution (DSM 141), 10 ml/liter trace element solution (DSM 141), and 4 μM resazurin at pH 7.5. Growth was determined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600).

Growth experiments on CO were conducted with 0 to 100% CO as the substrate at a final pressure of 2 × 105 Pa. The remainder of the gas phase (makeup gas) was N2 plus CO2 (80:20 [vol/vol]). Growth with H2 as the electron donor was carried out with H2 plus CO2 (80:20 [vol/vol]) at 2.5 × 105 Pa for the preparation of crude extracts or with H2 plus CO2 plus N2 (50:20:30 [vol/vol]) at 2 × 105 Pa for growth experiments. Growth on glucose was carried out by using 25 mM glucose in a gas atmosphere of N2 plus CO2 (80:20 [vol/vol]) at 1 × 105 Pa. Growth on syngas was carried out by using a mixture of 30% CO, 50% H2, 14% CO2, and 6% N2 at 2 × 105 Pa.

Preparation of resting cells and experiments with cell suspensions.

For preparation of cell suspensions, T. kivui was cultivated in 1-liter flasks (Müller-Krempel, Bülach, Switzerland) in the above-mentioned growth media. Cells were cultivated on glucose (25 mM glucose with N2 plus CO2 [80:20 {vol/vol} at 1 × 105 Pa], CO [50% CO, 40% N2, and 10% CO2 at 2 × 105 Pa], or H2 plus CO2 [80:20 {vol/vol} at 2.5 × 105 Pa]); harvested at an OD600 of 1.8 to 2.2, an OD600 of 0.10 to 0.15, or an OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4, respectively, by centrifugation (11,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C); and washed twice with imidazole buffer (50 mM imidazole, 20 mM MgSO4, 20 mM KCl, 20 mM NaCl, 4 mM dithioerythritol (DTE), 4 μM resazurin [pH 7.0]). After the last centrifugation step, cells were resuspended in 1 ml of the same buffer and kept in a gas-tight Hungate tube. The gas phase was exchanged to 100% N2. The protein concentration was determined according to methods described previously by Schmidt et al. (36). Serum flasks (120 ml; Glasgerätebau Ochs GmbH, Bovenden-Lenglern, Germany) were filled with 20 ml imidazole buffer containing 50 mM KHCO3. If indicated, the protonophore 3,3′,4′,5-tetrachlorosalicylanilide (TCS) was added to a concentration of 30 μM from a 10 mM stock solution with 100% ethanol as a solvent. Subsequently, the gas phase of the serum flasks was changed to N2 plus CO2 (80:20 [vol/vol]) at 1.3 × 105 Pa, and resting cells were added to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml and then incubated at 60°C in a water bath. After preincubation for 15 min, the reaction was started by flushing the flasks with 100% CO for 20 s. At the times indicated, 50-μl gas samples were withdrawn and directly injected into a gas chromatograph. Liquid samples (400 μl) were withdrawn for ATP measurements and immediately added to 300 μl of ice-cold 3 M perchloric acid. The samples were incubated on ice for exactly 1 h, and the pH was adjusted immediately to 7.0 by the addition of 93 μl 0.4 M N-tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid (TES) buffer (pH 7.4) and 57 μl of a saturated K2CO3 solution. The precipitated KClO4 was removed by centrifugation (13,400 × g for 5 min at 4°C), and the supernatant was immediately used for ATP measurements or frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −20°C. The ATP concentration was determined by using a luciferin-luciferase assay (37).

Preparation of crude extract, membranes, and cytoplasm.

Cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.2 to 0.3 on CO (50% CO, 40% N2, and 10% CO2 at 2 × 105 Pa), an OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4 on H2 plus CO2 (80:20 [vol/vol] at 2.5 × 105 Pa), or an OD600 of 1.9 to 2.4 on glucose (25 mM glucose with N2 plus CO2 [80:20 {vol/vol} at 1 × 105 Pa]) in 1-liter flasks (Glasgerätebau Ochs, Bovenden-Lenglern, Germany) filled with 200 ml complex medium for growth on gases or 500 ml complex medium for growth on glucose. Cells were harvested anaerobically by centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Cells were washed once in buffer A (50 mM Tris, 20 mM MgSO4, 20% glycerol, 2 mM DTE, 4 μM resazurin [pH 7.5]), and after another centrifugation step at 14,300 × g for 20 min at 4°C, cells were resuspended in 2 to 4 ml buffer A. Cells were disrupted by a single passage through a French press (110 MPa). Undisrupted cells and cell debris were separated by a centrifugation step at 14,300 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant contained the crude extract.

Measurement of enzyme activities.

Hydrogenase or carbon monoxide dehydrogenase activity was measured at 60°C in 1.8-ml anaerobic cuvettes (Glasgerätebau Ochs, Germany) filled with 1 ml Tris buffer at pH 7.5 containing 4 mM DTE and 4 μM resazurin with H2 or CO, respectively, at a pressure of 1.3 × 105 Pa. Methylviologen (MV) (10 mM) served as the electron acceptor for both reactions and was used to start the reaction. MV reduction was measured at 604 nm.

Determination of acetate concentrations.

Samples were withdrawn with a syringe, and cells were removed by centrifugation (14,000 × g for 1 min at 4°C). The acetate concentration in the supernatant was determined by using a gas chromatograph (Clarus 580 GC; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The samples were injected at 250°C and separated on an Elite FFAP column (30 m by 0.25 mm; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) with helium as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 30 cm/s and a split of 1:50. The oven was kept at 60°C for 3 min, followed by a temperature gradient to 150°C at 10°C/min. The samples were analyzed with a flame ionization detector at 250°C. 1-Propanol (10 mM) was used as an internal standard.

Determination of H2 and CO concentrations.

The concentrations of H2 and CO were determined by using a gas chromatograph (Clarus 580 GC; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The samples were injected at 100°C and separated on a ShinCarbon ST 80/100 column (2 m by 0.53 mm; Restek Corporation, Bellefonte, PA, USA). Nitrogen or helium was used as the carrier gas for the determination of H2 or CO concentrations, respectively, with a head pressure of 400 kPa and a split flow of 30 ml/s. The oven was kept at 40°C, and the samples were analyzed with a thermal conductivity detector at 100°C.

Analytical methods.

The protein concentration was measured according to methods described previously by Bradford (38) or, for whole cells, according to methods described previously by Schmidt et al. (36).

For immunological detection of both CODH proteins, the encoding genes were fused to a sequence encoding a His6 tag at the 5′ end and cloned according to methods described previously by Sambrook et al. (39), and the corresponding proteins were produced in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3), purified by affinity chromatography according to the manufacturer's instructions (New England BioLabs GmbH, Frankfurt/Main, Germany), and used for immunization of a rabbit (performed by Davids Biotechnologie, Regensburg, Germany). For Western blot analysis, 10 μg of each cell extract was separated by SDS-PAGE (12%). Proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Protran BA 83; GE Healthcare, United Kingdom), followed by immunoblotting with a 1:2,000 dilution of the rabbit antiserum for both antibodies. Primary antibody detection was performed with a goat anti-rabbit IgG–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (dilution of 1:10,000; Bio-Rad).

Chemicals.

Chemicals were purchased from AppliChem GmbH (Darmstadt, Germany), Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany), Roche Diagnostics GmbH (Mannheim, Germany), Carl Roth GmbH & Co. KG (Karlsruhe, Germany), and Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH (Steinheim, Germany). Gases were purchased from Praxair Deutschland GmbH (Düsseldorf, Germany).

RESULTS

Adaptation of T. kivui to growth on CO.

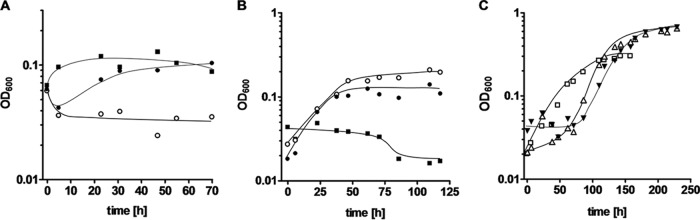

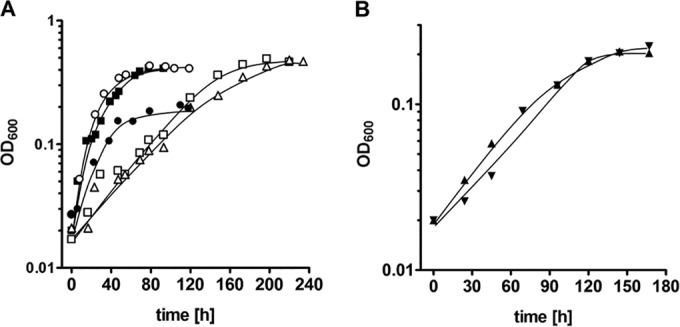

When T. kivui was grown on glucose and transferred to complex medium containing CO (10%) as the carbon and energy source, growth was not observed. Next, cells were pregrown on H2 plus CO2 and transferred to media with different CO concentrations. There was no growth in the presence of 30% CO (or higher) but one doubling in the presence of 10% CO (Fig. 1A). However, cells transferred to medium containing no CO also showed one doubling. Nevertheless, the 10% CO culture was taken as the preculture to inoculate media containing 10 or 20% CO. As shown in Fig. 1B, cells started to grow, and the final optical density was dependent on the CO concentration. At 10% CO, the final OD was 0.1, and at 20% CO, it was 0.2 (Fig. 1B). Next, the CO concentration was increased gradually in 10% increments. Transfer of cells from a 20% CO preculture to media with 30, 40, or 50% CO led to growth only in the presence of 30% CO, and the final OD was higher than that at 20% CO. Upon transfer of cells from a preculture grown at 30% CO to 40% CO, there was a lag phase of ∼72 h (Fig. 1C). Again, the final OD increased. In the next step, from 40 to 50% CO, the final optical density increased again (Fig. 1C). By a subsequent increase of the CO concentration in 10% increments, it was possible to adapt the culture to grow on up to 100% CO. Each transfer to a higher CO concentration resulted in a lag phase. However, the final optical density did not increase substantially above 50% CO.

FIG 1.

Adaptation of T. kivui to growth on CO. (A) A culture adapted to growth on H2 plus CO2 served as the preculture for inoculation of fresh medium in the absence of CO (■) or in the presence of 10% CO (●) or 30% CO (○). (B) The culture cultivated on 10% CO from panel A served as the preculture to reinoculate fresh medium in the absence of CO (■) or in the presence of 10% CO (●) or 20% CO (○). (C) The 20% CO culture from panel B was used as the preculture for cultivation on 30% CO (□), which in turn served as the preculture for cultivation on 40% CO (△). The latter served as the preculture for growth on 50% CO (▼). N2 plus CO2 (80:20 [vol/vol]) was used as the makeup gas at a final pressure of 2 × 105 Pa. All cultures were grown in complex medium, and growth was measured by monitoring the optical density at 600 nm. Shown are data from one representative experiment out of three independent replicates.

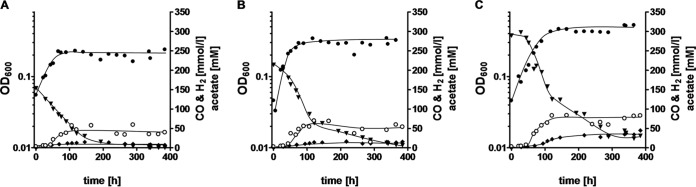

When cells were kept at the same CO concentration for at least three transfers, a lag phase was no longer observed (Fig. 2A). Adapted cultures grew with doubling times of 18.7, 15.4, 10.2, 34.7, and 33.0 h at 20, 50, 70, 90, and 100% CO, respectively. The corresponding final optical densities (OD600) were 0.21, 0.39, 0.41, 0.46, and 0.47, respectively (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

Growth of T. kivui adapted to CO. All cultures were grown in complex medium with increasing concentrations of CO (●, 20%; ■, 50%; ○, 70%; □, 90%; △, 100%) (A) or in mineral medium with 50% CO in the absence (▼) or presence (▲) of additional vitamins (B). N2 plus CO2 (80:20 [vol/vol]) was used as the makeup gas at a final pressure of 2 × 105 Pa. Growth was measured by monitoring the optical density at 600 nm. Cultures adapted to growth on CO (at least 3 transfers at the given concentrations) served as precultures for this experiment. Shown are data from one representative experiment out of three independent replicates.

Growth was also observed when cells were grown in mineral medium; the doubling time was 40.4 h (μ = 0.017 h−1), and the final optical density was 0.21 with 50% CO in the atmosphere (Fig. 2B). Omission of the vitamin solution had not effect on the growth rate or final optical density (Fig. 2B).

Consumption of CO and production of acetate and H2.

CO consumption and product formation were measured in cultures adapted to 30, 50, or 70% CO (Fig. 3). All cultures started to grow immediately and consumed CO at rates of 21 μmol/h (30% CO), 30 μmol/h (50% CO), or, after a short lag phase, 29 μmol/h (70% CO) in 20-ml cultures with a 200-ml gas phase. All cultures produced acetate and H2. When the final optical density was reached, acetate was no longer produced. At this point, 39.6, 53.6, or 82.7 mM acetate was produced in cultures containing 30, 50, or 70% CO, respectively. At the same time, H2 levels did not change anymore and stayed at 6.8, 15.8, or 44.9 mmol/liter medium in cultures containing 30, 50, or 70% CO, respectively. At the time when growth ceased and acetate and hydrogen production stopped, CO was still available in the cultures. Interestingly, it was consumed in the stationary growth phase but with much lower rates of 2, 4, and 9 μmol/h in the cultures with initial CO concentrations of 30, 50, and 70% CO, respectively. Electron flow from CO in the stationary growth phase could not be accounted for experimentally; formate, ethanol, propanol, and H2 were apparently not produced.

FIG 3.

CO consumption, acetate production, and H2 formation in cells growing on increasing concentrations of CO. The gas phase consisted of 30% CO (A), 50% CO (B), or 70% CO (C). N2 plus CO2 (80:20 [vol/vol]) was used as the makeup gas at a final pressure of 2 × 105 Pa. All cultures were grown in complex medium, and growth was measured by monitoring the optical density (●) at 600 nm. The concentrations of CO (▼) and H2 (◆) in the gas phase and of acetate in the liquid phase (○) were determined by gas chromatography. Shown are data from one representative experiment out of three independent replicates.

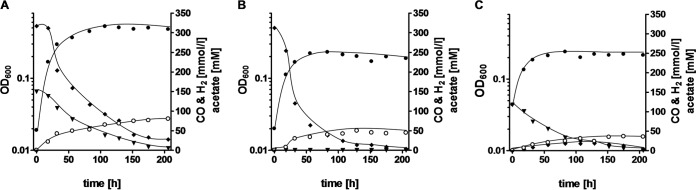

Simultaneous consumption of CO and H2 in a culture cultivated on syngas.

To determine whether T. kivui is able to grow on syngas and convert the gases simultaneously, cells were grown on 30% CO, 50% H2, and 14% CO2 (and 6% N2). Upon transfer of cells from a CO-grown preculture, CO and H2 consumption started immediately and continued simultaneously (Fig. 4A). The OD600 reached was 0.5, and 80 mM acetate was produced. In controls that received only H2 or CO as the electron donor, oxidation of the electron donor also started immediately, but the final optical density of the culture with H2 plus CO2 was only 46% of that of the syngas culture (Fig. 4B), and the final optical density of the CO culture was only 44% of that of the syngas culture (Fig. 4C). At the same time, acetate production was reduced.

FIG 4.

Simultaneous consumption of CO and H2 in cells growing on syngas. The gas phase consisted of 30% CO, 50% H2, 14% CO2, and 6% N2 (A); 50% H2, 20% CO2, and 30% N2 (B); or 30% CO, 14% CO2, and 56% N2 (C) at a pressure of 2 × 105 Pa. All cultures were grown in complex medium, and growth was measured by monitoring the optical density (●) at 600 nm. The concentrations of CO (▼) and H2 (◆) in the gas phase and of acetate in the liquid phase (○) were determined by gas chromatography. Shown are data from one representative experiment out of three independent replicates.

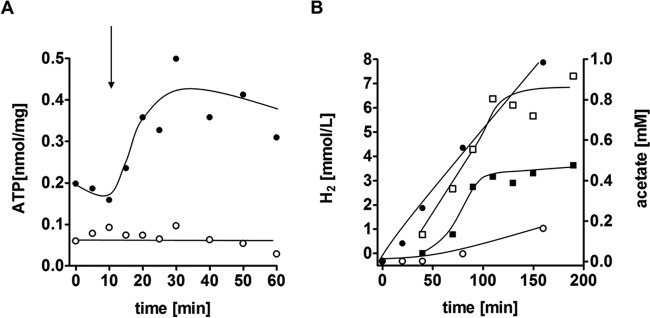

Energetics of CO-dependent acetate formation in cell suspensions.

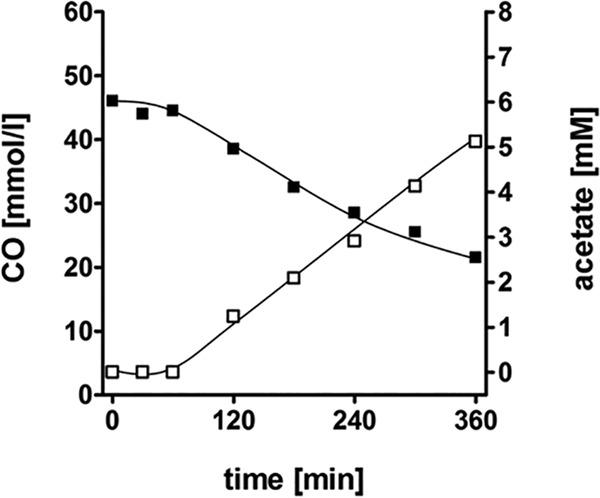

To investigate whether CO consumption was accompanied by acetate production, cell suspension experiments were conducted. Suspensions of cells that had been cultivated on CO (50%) consumed CO at a rate of 1.5 μmol/mg/min, and concomitantly, acetate was produced at a rate of 0.3 μmol/mg/min, reaching 5.1 mM acetate after 6 h (Fig. 5). Next, the effect of CO on cellular ATP levels was investigated. The introduction of CO to cell suspensions pregrown on CO led to an immediate increase of cellular ATP levels (Fig. 6A). When cell suspensions were prepared from cells pregrown on glucose or on H2 plus CO2, there was an immediate decrease in ATP levels upon the addition of CO, and acetate was not produced. When the protonophore TCS was present in the assay mixture, ATP was depleted, and there was no increase in ATP levels after the addition of CO (Fig. 6A). CO oxidation was coupled to H2 formation (Fig. 6B), with a hydrogen evolution rate of 0.7 μmol/mg/min, and 0.98 mM acetate was formed after 160 min. Preincubation of cells with the protonophore TCS led to an inhibition of acetate formation but a stimulation of H2 production, with an H2 evolution rate of 1.4 μmol/mg/min. The final amount of H2 produced was also doubled, with 7.3 mmol/liter buffer compared to 3.6 mmol/liter buffer in the assay containing no uncoupler. These data are fully consistent with a chemiosmotic mechanism of ATP synthesis coupled to CO oxidation and hydrogen formation. CO oxidation led to ion translocation and the generation of a membrane potential, Δψ, which resulted in thermodynamic backup pressure on CO oxidation. The addition of the protonophore TCS led to uncoupling, which in turn relieved the thermodynamic backup pressure and stimulated H2 formation. ATP synthesis was inhibited, and consequently, acetate formation from CO/CO2, which requires ATP, was also inhibited.

FIG 5.

CO consumption and acetate production in resting cells. T. kivui was grown on CO; cells were harvested, washed, and resuspended to a protein concentration of 1 mg/ml in 20 ml buffer (50 mM imidazole, 50 mM KHCO3, 20 mM MgSO4, 20 mM KCl, 20 mM NaCl, 4 mM DTE, 4 μM resazurin [pH 7.0]) in 120-ml serum bottles. The cell suspension experiments were carried out at 60°C in a shaking water bath. The gas phase contained 10% CO, and N2 plus CO2 (80:20 [vol/vol]) was used as the makeup gas at a final pressure of 2 × 105 Pa. The concentrations of CO (■) in the gas phase and acetate (□) in the liquid phase were determined by gas chromatography. Shown are data from one representative experiment out of three independent replicates.

FIG 6.

Influence of a protonophore on acetate, H2, and ATP formation from CO in resting cells. T. kivui was grown on CO, cells were harvested, washed, and resuspended to a protein concentration of 1 mg/ml in 20 ml of buffer (50 mM imidazole, 50 mM KHCO3, 20 mM MgSO4, 20 mM KCl, 20 mM NaCl, 4 mM DTE, 4 μM resazurin [pH 7.0]) in 120-ml serum bottles. Experiments were carried out at 60°C in a shaking water bath. N2 plus CO2 (80:20 [vol/vol]) was used as the makeup gas at a pressure of 1 × 105 Pa. Cells and the protonophore were preincubated for 10 min at 60°C. Vials were flushed with CO for 20 s. (A) The ATP content was measured by using the luciferin-luciferase assay with an assay mixture containing no protonophore (●) or 30 μM TCS (○). The arrow indicates the time point of CO flushing. (B) Hydrogen (squares) and acetate (circles) formation was measured by gas chromatography in an assay mixture in the absence of the protonophore (filled symbols) or in an assay mixture containing 30 μM TCS (hollow symbols). Shown are data from one representative experiment out of three independent replicates.

Key enzyme activities in crude extracts.

The above-mentioned experiments revealed the production of molecular hydrogen from CO. Hydrogenase and carbon monoxide dehydrogenase activities were analyzed in crude extracts prepared from a culture in the exponential growth phase grown on CO, H2 plus CO2, or glucose. The specific activity for H2-dependent methylviologen reduction was by far the highest in crude extracts of CO-grown cells, at 82.1 ± 22.7 U/mg, compared to 25.1 ± 3.1 U/mg in crude extracts of H2- and CO2-grown cells and 33.9 ± 7.3 U/mg in crude extracts of glucose-grown cells. CODH activity was highest in crude extracts prepared from H2- and CO2-grown cells (286.0 ± 73.7 U/mg), similar to that in crude extracts of CO-grown cells (233.3 ± 58.5 U/mg), and much higher than that in glucose-grown cells (91.0 ± 19.9 U/mg).

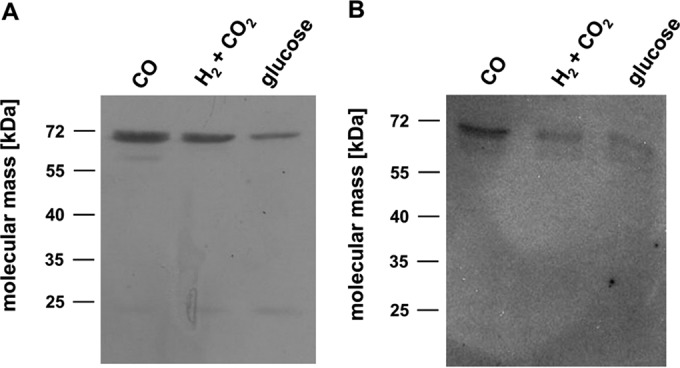

Presence of carbon monoxide dehydrogenases in crude extracts.

The genome of T. kivui harbors two genes encoding two potential CO dehydrogenases. One gene product (CooS) is similar to monofunctional CO dehydrogenases (CooS), and the other (AcsA) is similar to the CODH subunit of the bifunctional CODH/ACS complexes. Western blot analyses revealed that both CODH enzymes were present in crude extracts prepared from cells grown on CO, H2 plus CO2, or glucose. The amounts of bifunctional AcsA were more or less the same in cells grown on CO and those grown on H2 plus CO2 but were smaller in glucose-grown cells (Fig. 7A). In contrast, CooS levels were highest in CO-grown cells (Fig. 7B).

FIG 7.

Detection of AcsA and CooS in crude extracts. Cells were grown on CO, H2 plus CO2, or glucose and harvested in the exponential growth phase. The cell extract was prepared, and 10 μg protein from each sample was separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The presence of AcsA (A) or CooS (B) was determined immunologically with antibodies raised against heterologously produced proteins.

DISCUSSION

It was reported previously that the thermophilic acetogen T. kivui does not grow on CO (12, 40, 41). This finding could be reproduced in this study: upon transfer of a glucose-cultivated preculture to medium containing CO, cells did not grow. However, when inoculated from a preculture cultivated on H2 plus CO2, cells grew in the presence of 10% CO but not in the presence of 30% CO or higher. When reinoculated with 10% increments of CO in the gas phase, T. kivui grew even in the presence of 100% CO. Apparently, the organism needs sufficient time to adapt its metabolism and has set metabolic changes upon autotrophic growth on H2 plus CO2 that are missing during heterotrophy. Apparent final optical densities did not increase substantially at concentrations of CO above 50%, indicating that a factor other than the CO concentration was limiting. The medium pH was not the limiting factor, since it remained constant at pH 7.5.

Acetogenic bacteria play an emerging role in biotechnological applications as organisms that convert industrial waste gases (syngas) to biocommodities (42, 43). The ability of T. kivui to use syngas is thus of great biotechnological interest. T. kivui is a thermophilic organism with an optimal growth temperature at 66°C and a temperature tolerance of 55°C to 70°C (30), which could be advantageous for certain applications at higher temperatures. Growth on CO was observed in mineral medium without yeast extract and without additional vitamins, which is a great advantage for potential biotechnological use due to a considerable cost reduction. Another interesting aspect of syngas utilization is the simultaneous consumption of CO and H2. While CO-tolerant H2-evolving hydrogenases have been described and characterized in several organisms (44, 45), the occurrence of an H2-consuming hydrogenase that is insensitive to CO inhibition is hitherto unprecedented (43). The syngas experiments were, however, conducted in a standing culture and thus are subject to the buildup of a gas gradient within the medium. Hence, it remains to be elucidated whether the simultaneous gas consumption is due to the different solubilities of CO and H2 due to an established gas gradient or whether there is indeed a CO-tolerant H2-consuming hydrogenase.

The requirement of adaptation to CO is not only reflected by the growth experiments but also validated by cell suspension experiments with CO. Cell suspensions of T. kivui prepared from a culture adapted to CO showed an immediate increase in cellular ATP levels upon the addition of CO. In contrast, the addition of CO to cell suspensions of glucose- or H2-plus-CO2-grown cells resulted in an immediate decrease in cellular ATP levels and no acetate formation. A requirement for adaptation to CO as an energy source was reported previously for another acetogenic bacterium. In 1982, a strain of Butyribacterium methylotrophicum (Marburg strain) was adapted to grow vigorously on CO alone, which was termed the CO strain of B. methylotrophicum (20). The authors of that study selected the strain by transferring the Marburg strain twice to medium containing methanol with a 100% CO gas phase and subsequently transferring the strain four times to medium with 100% CO. While cells from the first transfers reached an OD660 of 0.1 to 0.2 after 2 to 3 weeks, the fifth transfer resulted in an OD660 of 0.5, and CO was completely consumed in 3 days. CODH levels in the methanol-grown strain were surprisingly higher than those in the CO-grown strain, which led to the conclusion that more than one CODH activity is required for growth on carbon monoxide. The genome of T. kivui harbors two genes coding for carbon monoxide dehydrogenases. One of these genes is acsA, which encodes the CODH that, together with the acetyl-CoA synthase, forms the central enzyme complex of the WLP, the CODH/ACS complex. The second CODH gene (cooS) presumably encodes a monofunctional CODH (29). CODH activity measured in crude extracts revealed that CODH activity was highest in cells grown on H2 plus CO2 and only marginally lower in CO-grown cells but much lower in glucose-grown cells. This finding is plausible, as during growth on CO, the latter must be scavenged as quickly as possible to prevent a possible inhibition of the soluble hydrogenases. Immunoblot analysis revealed that bifunctional AcsA was present during growth on all substrates but was clearly less abundant in glucose-grown cells. The monofunctional CODH CooS, on the other hand, was clearly more abundant in cells grown on CO than in cells grown on H2 plus CO2 or on glucose. Thus, the monofunctional CODH seems to play a superior role during CO metabolism, making it quite feasible that the ability to grow on CO is at least partly attributable to the monofunctional CODH. However, a monofunctional CODH besides the CODH/ACS is also encoded in the genome of A. woodii, and since this acetogen cannot grow solely on CO (24), it is more likely that a more elaborate adaptation is required.

During autotrophic growth, acetogenic bacteria rely on a chemiosmotic mechanism for energy conservation. In the case of T. kivui, the respiratory enzyme is an Ech complex (29) that, in principle, catalyzes ferredoxin oxidation and H+ reduction. This is coupled to H2 evolution and ion translocation. Here we show that the production of acetate and H2 was coupled to the synthesis of ATP. Whereas acetate production was inhibited by a protonophore, H2 production was stimulated, indicating a coupling of hydrogen production from CO with the synthesis of ATP by a chemiosmotic mechanism. Thus, the generation of the chemiosmotic ion gradient during autotrophic growth on CO is directly coupled to H2 evolution. H2 evolution from CO requires the presence of a CO-tolerant hydrogenase. This is reminiscent of the CO-oxidizing, H2-forming enzyme systems (Coo) found in Methanosarcina barkeri (46), Rhodospirillum rubrum (47), Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans (48), and Thermococcus onnurineus NA1 (49). These organisms grow on CO by coupling the oxidation of CO to CO2 by a proton-translocating and proton-reducing electron transport chain. Purification of the CO-oxidizing, H2-forming enzyme from C. hydrogenoformans revealed that a 6-subunit [NiFe]-hydrogenase forms a tight complex with a Ni-containing CODH (CooS) and an electron transfer protein (CooF) (45). It is feasible that a very similar complex is present in T. kivui grown on CO, and the higher abundance of CooS in CO-grown cells consolidates this idea. This idea is consistent with our previous notion that T. kivui has two Ech hydrogenases (29) and the observation that hydrogenase activity is by far the highest in crude extracts prepared from CO-grown cells. The role of the different Ech hydrogenases in T. kivui and their biochemistry and bioenergetics remain to be established.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sokolova TG, Henstra AM, Sipma J, Parshina SN, Stams AJ, Lebedinsky AV. 2009. Diversity and ecophysiological features of thermophilic carboxydotrophic anaerobes. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 68:131–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henstra AM, Sipma J, Rinzema A, Stams AJ. 2007. Microbiology of synthesis gas fermentation for biofuel production. Curr Opin Biotechnol 18:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer O, Schlegel HG. 1978. Reisolation of the carbon monoxide utilizing hydrogen bacterium Pseudomonas carboxydovorans (Kistner) comb. nov. Arch Microbiol 118:35–43. doi: 10.1007/BF00406071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uffen RL. 1976. Anaerobic growth of a Rhodopseudomonas species in the dark with carbon monoxide as sole carbon and energy substrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 73:3298–3302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.9.3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sokolova TG, Gonzalez JM, Kostrikina NA, Chernyh NA, Slepova TV, Bonch-Osmolovskaya EA, Robb FT. 2004. Thermosinus carboxydivorans gen. nov., sp. nov., a new anaerobic, thermophilic, carbon-monoxide-oxidizing, hydrogenogenic bacterium from a hot pool of Yellowstone National Park. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 54:2353–2359. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sokolova TG, Jeanthon C, Kostrikina NA, Chernyh NA, Lebedinsky AV, Stackebrandt E, Bonch-Osmolovskaya EA. 2004. The first evidence of anaerobic CO oxidation coupled with H2 production by a hyperthermophilic archaeon isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. Extremophiles 8:317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniels L, Fuchs G, Thauer RK, Zeikus JG. 1977. Carbon monoxide oxidation by methanogenic bacteria. J Bacteriol 132:118–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Brien JM, Wolkin RH, Moench TT, Morgan JB, Zeikus JG. 1984. Association of hydrogen metabolism with unitrophic or mixotrophic growth of Methanosarcina barkeri on carbon monoxide. J Bacteriol 158:373–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rother M, Metcalf WW. 2004. Anaerobic growth of Methanosarcina acetivorans C2A on carbon monoxide: an unusual way of life for a methanogenic archaeon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:16929–16934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407486101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diekert GB, Thauer RK. 1978. Carbon monoxide oxidation by Clostridium thermoaceticum and Clostridium formicoaceticum. J Bacteriol 136:597–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savage MD, Wu ZG, Daniel SL, Lundie LL Jr, Drake HL. 1987. Carbon monoxide-dependent chemolithotrophic growth of Clostridium thermoautotrophicum. Appl Environ Microbiol 53:1902–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daniel SL, Hsu T, Dean SI, Drake HL. 1990. Characterization of the H2-dependent and CO-dependent chemolithotrophic potentials of the acetogens Clostridium thermoaceticum and Acetogenium kivui. J Bacteriol 172:4464–4471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diender M, Stams AJ, Sousa DZ. 2015. Pathways and bioenergetics of anaerobic carbon monoxide fermentation. Front Microbiol 6:1275. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuchmann K, Müller V. 2014. Autotrophy at the thermodynamic limit of life: a model for energy conservation in acetogenic bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:809–821. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin WF, Sousa FL, Lane N. 2014. Evolution. Energy at life's origin. Science 344:1092–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1251653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buckel W, Thauer RK. 2013. Energy conservation via electron bifurcating ferredoxin reduction and proton/Na+ translocating ferredoxin oxidation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1827:94–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Köpke M, Held C, Hujer S, Liesegang H, Wiezer A, Wollherr A, Ehrenreich A, Liebl W, Gottschalk G, Dürre P. 2010. Clostridium ljungdahlii represents a microbial production platform based on syngas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:13087–13092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004716107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daniell J, Köpke M, Simpson SD. 2012. Commercial biomass syngas fermentation. Energies 5:5372–5417. doi: 10.3390/en5125372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bengelsdorf FR, Straub M, Dürre P. 2013. Bacterial synthesis gas (syngas) fermentation. Environ Technol 34:1639–1651. doi: 10.1080/09593330.2013.827747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynd L, Kerby R, Zeikus JG. 1982. Carbon monoxide metabolism of the methylotrophic acidogen Butyribacterium methylotrophicum. J Bacteriol 149:255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Genthner BR, Bryant MP. 1982. Growth of Eubacterium limosum with carbon monoxide as the energy source. Appl Environ Microbiol 43:70–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lorowitz WH, Bryant MP. 1984. Peptostreptococcus productus strain that grows rapidly with CO as the energy source. Appl Environ Microbiol 47:961–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanner RS, Miller LM, Yang D. 1993. Clostridium ljungdahlii sp. nov., an acetogenic species in clostridial rRNA homology group I. Int J Syst Bacteriol 43:232–236. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-2-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bertsch J, Müller V. 2015. CO metabolism in the acetogen Acetobacterium woodii. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:5949–5956. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01772-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biegel E, Müller V. 2010. Bacterial Na+-translocating ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:18138–18142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010318107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biegel E, Schmidt S, González JM, Müller V. 2011. Biochemistry, evolution and physiological function of the Rnf complex, a novel ion-motive electron transport complex in prokaryotes. Cell Mol Life Sci 68:613–634. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0555-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hess V, Schuchmann K, Müller V. 2013. The ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase (Rnf) from the acetogen Acetobacterium woodii requires Na+ and is reversibly coupled to the membrane potential. J Biol Chem 288:31496–31502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.510255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierce E, Xie G, Barabote RD, Saunders E, Han CS, Detter JC, Richardson P, Brettin TS, Das A, Ljungdahl LG, Ragsdale SW. 2008. The complete genome sequence of Moorella thermoacetica (f. Clostridium thermoaceticum). Environ Microbiol 10:2550–2573. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hess V, Poehlein A, Weghoff MC, Daniel R, Müller V. 2014. A genome-guided analysis of energy conservation in the thermophilic, cytochrome-free acetogenic bacterium Thermoanaerobacter kivui. BMC Genomics 15:1139. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leigh JA, Mayer F, Wolfe RS. 1981. Acetogenium kivui, a new thermophilic hydrogen-oxidizing, acetogenic bacterium. Arch Microbiol 129:275–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00414697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaw AJ, Hogsett DA, Lynd LR. 2010. Natural competence in Thermoanaerobacter and Thermoanaerobacterium species. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:4713–4719. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00402-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu B, Wang C, Yang H, Tan H. 2012. Establishment of a genetic transformation system and its application in Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis. J Genet Genomics 39:561–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sipma J, Henstra AM, Parshina SM, Lens PN, Lettinga G, Stams AJ. 2006. Microbial CO conversions with applications in synthesis gas purification and bio-desulfurization. Crit Rev Biotechnol 26:41–65. doi: 10.1080/07388550500513974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hungate RE. 1969. A roll tube method for cultivation of strict anaerobes, p 117–132. In Norris JR, Ribbons DW (ed), Methods in microbiology, vol 3b Academic Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bryant MP. 1972. Commentary on the Hungate technique for culture of anaerobic bacteria. Am J Clin Nutr 25:1324–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt K, Liaaen-Jensen S, Schlegel HG. 1963. Die Carotinoide der Thiorhodaceae. Arch Mikrobiol 46:117–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00408204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kimmich GA, Randles J, Brand JS. 1975. Assay of picomole amounts of ATP, ADP and AMP using the luciferase enzyme system. Anal Biochem 69:187–206. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tracy BP, Jones SW, Fast AG, Indurthi DC, Papoutsakis ET. 2012. Clostridia: the importance of their exceptional substrate and metabolite diversity for biofuel and biorefinery applications. Curr Opin Biotechnol 23:364–381. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drake HL, Küsel K, Matthies C. 2006. Acetogenic prokaryotes, p 354–420. In Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer K-H, Stackebrandt E (ed), The prokaryotes, 3rd ed, vol 2 Springer-Verlag, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schiel-Bengelsdorf B, Dürre P. 2012. Pathway engineering and synthetic biology using acetogens. FEBS Lett 586:2191–2198. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bertsch J, Müller V. 2015. Bioenergetic constraints for conversion of syngas to biofuels in acetogenic bacteria. Biotechnol Biofuels 8:210. doi: 10.1186/s13068-015-0393-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fox JD, Kerby RL, Roberts GP, Ludden PW. 1996. Characterization of the CO-induced, CO-tolerant hydrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum and the gene encoding the large subunit of the enzyme. J Bacteriol 178:1515–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soboh B, Linder D, Hedderich R. 2002. Purification and catalytic properties of a CO-oxidizing:H2-evolving enzyme complex from Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans. Eur J Biochem 269:5712–5721. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bott M, Thauer RK. 1987. Proton-motive-force-driven formation of CO from CO2 and H2 in methanogenic bacteria. Eur J Biochem 168:407–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kerby RL, Ludden PW, Roberts GP. 1995. Carbon monoxide-dependent growth of Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol 177:2241–2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Svetlichnyi VA, Sokolova TG, Gerhardt M, Ringpfeil M, Kostrikina NA, Zavarzin GA. 1991. Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans gen. nov., sp. nov., a CO-utilizing thermophilic anaerobic bacterium from hydrothermal environments of Kunashir Island. Syst Appl Microbiol 14:254–260. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(11)80377-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee HS, Kang SG, Bae SS, Lim JK, Cho Y, Kim YJ, Jeon JH, Cha S-S, Kwon KK, Kim H-T, Park C-J, Lee H-W, Kim SI, Chun J, Colwell RR, Kim S-J, Lee J-H. 2008. The complete genome sequence of Thermococcus onnurineus NA1 reveals a mixed heterotrophic and carboxydotrophic metabolism. J Bacteriol 190:7491–7499. doi: 10.1128/JB.00746-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]