Abstract

There is a rising prevalence of older HIV+ adults who are at risk of deficits in higher-order neurocognitive functions and associated problems in everyday functioning. The current study applied Multiprocess Theory to examine the effects of HIV and aging on measures of laboratory-based, naturalistic, and self-perceived symptoms of prospective memory (PM). Participants included 125 Younger (48 with HIV, age = 32±4.6 years) and 189 Older (112 with HIV, age = 56±4.9 years) adults. Controlling for global neurocognitive functioning, mood, and other demographics, older age and HIV had independent effects on long-delay time-based PM in the laboratory, whereas on a naturalistic PM task older HIV− adults performed better than older HIV+ adults and younger persons. In line with the naturalistic findings, older age, but not HIV, was associated with a relative sparing of self-perceived PM failures in daily life across longer delay self-cued intervals. Findings suggest that, even in relatively younger aging cohorts, the effects of HIV and older age on PM can vary across PM delay intervals by the strategic demands of the retrieval cue type, are expressed differently in the laboratory and in daily life, and are independent of other higher-order neurocognitive functions (e.g., retrospective memory).

Keywords: Prospective memory, episodic memory, neuropsychological assessment, HIV, aging

Introduction

HIV infection among people 50 years of age and older is increasingly prevalent, primarily due to advances in combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) that have extended life expectancies and transformed HIV into a chronic disease (Hogg et al., 1998; Powderly, 2002). Adults over age 50 accounted for 22% of estimated new diagnoses in 2008 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011) and represent nearly one quarter of the current HIV population, with prevalence rates expected to rise to nearly 73% by 2030 (Smit, Brinkman, Geerlings, Smit, Thyagarajan, Sighem, Wolf, & Hallet, 2015). Older adults with HIV are at greater risk for rapid disease progression than their younger counterparts (Goetz, Boscardin, Wiley, & Alkasspooles, 2001) and commonly experience higher rates of HIV-associated central nervous system (CNS) complications such as increased neuropathological burden (e.g., beta-amyloid deposition; Green, Masliah, Vinters, Beizai, Moore, & Achim, 2005), smaller frontal grey matter volumes (Jernigan et al., 2005), and spectroscopic evidence of neural injury in frontal white matter and basal ganglia (Ernst & Chang, 2004). Older age is also associated with increased risk of HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment (Valcour, Shikuma, Watters, & Sacktor, 2004) and related declines in everyday functioning (e.g., Morgan, Iudicello, & Weber, 2012). In fact, HIV+ older adults with HIV Associated Neurocognitive Disorders (HAND) may be at disproportionate risk for healthcare non-compliance, including cART non-adherence (Hinkin et al., 2004), and being lost to follow-up in HIV clinical care (Jacks et al., 2015).

One distinct aspect of cognition affected by both HIV disease (Carey, Woods, Rippeth, Heaton, & Grant, 2006) and older age (Henry, MacLeod, Phillips, & Crawford, 2004) is prospective memory (PM; Einstein & McDaniel, 1990). PM is defined as the execution of planned actions in the future, or more simply, “remembering to remember.” Everyday examples of PM range from common household tasks, such as remembering to switch off the lights when not in use, to vitally important health-related tasks, such as remembering to take a prescribed medication or attend a healthcare appointment. The current study applied the Multiprocess Theory of PM (Einstein & McDaniel, 1990) to examine the effects of HIV and aging on measures of laboratory-based, naturalistic, and self-perceived symptoms of prospective memory (PM).

Prospective Memory: Retrieval Cue Type and Delay Interval

The extant theories on PM tend to agree on some essential cognitive processes involved in successful execution of a future intention, which include: (1) forming an intention, (2) associating the intention with a retrieval cue (i.e., passage of time [time-based PM] or the occurrence of a specific event [event-based PM]), (3) retaining this association over a delay interval during which PM monitoring may occur while one is engaged in an ongoing task, (4) noticing the PM retrieval cue, and subsequently disengaging from the ongoing task, (5) retrieving the appropriate intention from retrospective memory, and (6) executing the planned PM action (see Kliegel, McDaniel & Einstein, 2008 for a review). One influential theory of PM, the Multiprocess Theory, postulates that the cognitive demands of PM across these stages vary along a continuum from being automatic/spontaneous to strategic/executive (McDaniel & Einstein, 2000). Specifically, two types of processes support prospective remembering: (1) top down executively-guided strategic/attention-demanding processes through which individuals rehearse their PM task goals and/or monitor the task environment for PM cues and (2) spontaneous processes that reflexively/involuntarily respond to PM cues (Einstein & McDaniel, 2010). In general, time-based PM tasks (e.g., remembering to attend a healthcare appointment at 11 am) are more strategically demanding than event-based tasks (e.g., remembering to ask a healthcare provider a specific question during an examination) because the former rely more heavily on self-initiated executive processes (e.g., monitoring the passage of time) than do the latter (McDaniel & Einstein, 2007). That said, the exact properties of event-based and time-based tasks can impact their relative resource demands. Some event-based tasks place considerable demands on strategic processes and thereby more closely resemble the presumed cognitive demands of time-based tasks (e.g., Henry et al., 2004), and in fact event-based tasks can be more strategically demanding than time-based tasks.

Regarding the resource demands of time-based PM, Huang, Loft, and Humphreys (2014) showed that when clock checking was encouraged the resulting resource demands of time-based PM decreased, and the authors posited that the need for internal cognitive control was transferred to the external world by performing the well-practiced task of checking the clock, which reminded participants of the PM task and reduced the internal cognitive control required to maintain the PM intention. In contrast, Huang et al. (2014) found significant costs to the ongoing task (reflective of capacity-sharing between the ongoing and PM task; Smith, Bayen, & Martin, 2010) when participants were not encouraged to check the clock, presumably because internal control processes were required to make prospective timing estimates and to maintain the intention to perform the PM task.

The Multiprocess Theory posits that by manipulating certain task parameters, including increasing cue distinctiveness, cue focality (i.e., the degree to which the ongoing task directs attention to the features of PM cues processed at encoding), or the associativity of the cue with the intended action, an event-based task retrieval can be more spontaneous and therefore less strategically demanding (Einstein & McDaniel, 2010; McDaniel & Einstein, 2000). For example, a highly associated cue and intended action pairings facilitate spontaneous retrieval. In line with this, McDaniel Guynn, Einstein, and Breneiser (2004) reported that highly related PM cue-response conditions produced more accurate PM performance than low related cue-response conditions, and that PM performance for high cue-response pairings were not disrupted by manipulations of divided attention (also see Loft & Yeo, 2007).

An additional essential and defining, yet relatively underexplored, component of PM tasks is the delay interval between intention formation and subsequent retrieval. During the delay interval, one needs to maintain the deferred intent to act, and remember the content of the intention-cue pairing in the face of possible decay and interference. Some research has found that increased PM delay has a negative impact of PM accuracy, in both healthy (e.g., Loft, Kearney, & Remington, 2008; Scullin, Bugg, McDaniel, & Einstein., 2011) and clinical populations (Raskin et al., 2011; Weinborn, Bucks, Stritzke, Leighton, & Woods, 2011). However, delay effects on PM are not always found (e.g., Hicks, Marsh, & Russel, 2000) and findings often are contingent upon what participants are doing over the delay interval (Martin, Brown, & Hicks, 2011). Specifically, Martin et al. (2011) reported that lengthening duration of the ongoing task prior to the presentation of the (first) PM cue decreased PM, while lengthening the duration of a filler task between the intention formation and the beginning of the ongoing task in which PM cues were embedded did not impact PM.

According to the Multiprocess Theory, under more resource-demanding PM conditions, longer delays place greater demands on limited executive resources supporting cue detection and monitoring; therefore, performance should suffer as delay interval increases (Einstein & McDaniel, 2010). More precisely, the term “greater demands” in this context refers to the fact that it is difficult for the human cognitive system to maintain the allocation of resources (effort) to a specific task the longer that the task has not been presented (or made relevant in the context of time-based PM) in an ongoing task context (Remington & Loft, 2015). In line with this, Loft et al. (2008) and Scullin et al. (2011) found that costs to ongoing tasks deceased (reflecting decreased PM cue monitoring) and PM accuracy declined, with increased delay in resource-demanding PM tasks. However, the degree to which individuals can rely more on spontaneous retrieval, and thus require less executive control, delay should have a decreased impact. Similarly, Scullin et al. (2011) reported that increased delay interval has a negative effect on a non-focal event-based PM task but a null effect on a focal event-based PM task.

In the sections below, we draw upon the Multiprocess theory, and associated empirical research, to discuss the possible effects of HIV and older age on PM. Further, we were interested in examining how these effects might vary according to the retrieval cue types and PM delay intervals of various laboratory-based, naturalistic, and self-perceived measures of PM.

Effect of HIV on Prospective Memory

The value of PM in predicting crucial daily life activities in HIV+ adults has kindled scholarly interest on effect of HIV on different aspects of PM. Emergent literature using the Memory for Intentions Screening Test (MIST; Raskin, Buckheit, & Sherrod, 2010) indicates that persons living with HIV disease have problems with PM functioning, but that the extent of this deficit, as predicted by the Multiprocess theory, is dependent on retrieval cue type and PM delay interval. Persons living with HIV disease are particularly susceptible to the increased strategic demands of long-delayed time-based PM tasks. Time-based PM tasks on the MIST are typically considered to be more resource demanding than the event-based PM tasks. This is because the time-based tasks do not encourage clock checking (Huang et al., 2014), and the event-based PM cue-intention pairings are high in semantic relatedness (Loft & Yeo, 2007; McDaniel et al., 2004). The MIST also manipulates the duration of the ongoing task prior to the presentation of PM cues, and thus different delay intervals would be expected to have an effect on PM performance (Martin et al., 2011). In a sample of middle-aged adults, Morgan et al. (2012) observed that HIV+ persons with clinical neurocognitive disorders (Antinori, Arendt, & Becker, 2007) performed more poorly than seronegatives on longer (i.e., 15-min) but not shorter (i.e., 2-min) PM delay tasks. In addition, the effect of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders was stronger for time-based PM than for event-based PM, and was specifically associated with executive dysfunction (i.e., planning and cognitive flexibility).

In contrast to the findings in laboratory settings, Weber, Woods, Delano-Wood, Bondi, and Grant (2011) reported no observed difference between HIV+ and HIV− participants on a naturalistic time-based PM task that required participants to remember to telephone the examiner at a specific time the next day. Nonetheless, several studies have shown that variance in performance on these naturalistic tasks by HIV+ individuals is predictive of both objective and self-report real-world behavioral outcomes, such as medication non-adherence (Woods et al., 2008; Zogg et al., 2011).

The Paradoxical Effect of Age on Prospective Memory

Meta-analyses of PM research in various laboratory paradigms have indicated that older age is associated with moderate declines in performance on time-based PM tasks and more strategically demanding non-focal event-based PM tasks (Henry et al., 2004; Kliegel, McDaniel, & Einstein 2008). In addition, among typically aging adults tested in the laboratory, longer delay intervals between intention formation and the presentation of retrieval cues are associated with poorer PM (Einstein et al., 2000; McDaniel et al., 2013), which some authors have argued is secondary to age-related decline in executive functions (Kliegel et al., 2003; Scullin et al., 2011).

In contrast to PM performance on laboratory paradigms, the meta-analysis conducted by Henry et al. (2004) showed that PM task requirements embedded in naturalistic settings (such as mailing a stamped postcard to the experimenter several days in the future; McBride, Coane, Drwal, & LaRose, 2013) were associated with advantages in older age. Possible explanations for these conflicting patterns of results may include increased motivation by older adults for naturalistic compared to laboratory PM tasks (Aberle, Rendell, Rose, McDaniel, & Kliegel, 2010), the possibility that older adults have more structured lives (Bailey, Henry, Rendell, Phillips, & Kliegel, 2010), or higher use of reminders in this cohort (Rendell & Thomson, 1999). Indeed, it has been argued that the paradoxical effect of age on PM may be at least partially attributable to the external aids that cue the PM event. In laboratory (e.g., computer task or MIST) settings, participants completing time-based PM tasks have to self-initiate and maintain prospective timing estimations (internally keeping time or checking a clock) in order to monitor for the approaching PM target time (Huang et al. 2014; Waldum & Sahakyan, 2013). In contrast, self-report data collected by Kvavilashvili and Fisher (2007) indicated that in naturalistic settings, instead of continually monitoring time, individuals preferentially relied on external cues (e.g., seeing the phone, seeing a diary, etc.) routinely encountered in their day-to-day lives in order to prompt PM retrieval. Hence, it might be speculated that older adults evidence superior performances because it is crucial for them to learn compensatory strategies (e.g., the use of reminders; Rendell & Thomson, 1999) in order to mitigate difficulties they might face in everyday life.

The Current Study: The Effects of HIV Disease and Age on PM

To investigate the effects of HIV and aging on PM, the present study aimed to use multiple, complementary lenses on the construct of PM, which includes a well-validated laboratory task (MIST), a naturalistic PM task, and a widely-used self-measure of PM symptoms (PRMQ). It has been argued that PM is ubiquitous in daily life and therefore captures aspects of functionally essential cognition that are not assessed by traditional tests. We argue that these tasks capture different aspects of this important cognitive function. Also note that it is common across cognitive constructs (i.e., not just PM) for self-report and actual performance to diverge, but measuring one without the other in a clinical population leaves us with an incomplete picture of the construct. Lab-based measures provide an index of ability/capacity under controlled conditions, whereas self-report and naturalistic measures provide an index of how PM operates in daily life, which can be influenced by a host of different factors.

Another novelty of this study concerns the cutoff for older age. Compared to the studies reported above, which used 60 and over as a cutoff age, our study utilized a relatively young and non-traditional cutoff of age 50 years in order to define “older” adults. This age classification is driven by the epidemiology of HIV infection and recommendations of the NIH aging research taskforce (Stoff, Mitnick, & Kalichman, 2004). More specifically, less than 5% of the entire HIV population in the US is 65+ years of age (CDC, 2014), which is a similar proportion to that observed in this study (i.e., 5%). NIH recommended that researchers focus their attention on the growing number of persons aged 50 and older with HIV disease, who now represent approximately one-third of the epidemic (CDC, 2013) and are at heighted risk for central nervous system involvement. In the same way, very few persons with HIV disease are 20 years or younger (CDC, 2014). Thus, the traditional cognitive psychology approach of comparing very old persons to very young persons is not feasible (or epidemiologically relevant) in studies of aging with HIV disease. As such, the current study’s use of a 10-year age-gap grouping is appropriate and in line with prior studies (e.g., Weber et al., 2011; Woods, Dawson, Weber, & Grant, 2010).

The consensus of the literature indicates that both HIV disease and older age are associated with poor performance on strategically demanding PM when performance is measured in the laboratory. For example, Woods et al. (2010) reported additive effects of HIV and aging on strategically demanding event-based PM (i.e., decreasing the semantic relatedness of the cue-intention pairing), which was associated with executive dysfunction. However, this study did not include a measure of time-based PM, nor an examination of delay interval. Hence, one of the primary aims of the study is to directly compare age and HIV associated changes in event-based and time-based PM as a function of delay interval as manipulated in a laboratory PM task (MIST). Unlike event-based PM, time-based PM is a historically understudied area. Indeed, it is possible that the effects of older age on time-based PM tasks may be exacerbated by the added strategic monitoring demands of time-based PM. As reviewed, MIST event–based PM tasks are designed to be less resource demanding (non-focal, but high cue-intention semantic relatedness) than time-based PM tasks (clocking checking not encouraged). With regards to the delay effects—as cited above—PM has not always been shown to be affected by the delay interval (e.g., Hicks et al., 2000). Further, delay effects depend on the tasks that participants perform over the delay interval (Martin et al. 2011). Specifically, Martin et al. (2011) reported that lengthening the duration of the ongoing task prior to the presentation of the PM cue decreased PM. In the current study, we manipulated the duration of the ongoing task prior to the presentation of the PM cue, and we expected poorer PM performance for longer delays. Additionally, Loft et al. (2008) reported that delay length had an impact on PM when the target was non-focal. The MIST PM cues we used in the present study were non-focal, and therefore the delay interval was expected to have an effect on performance. However, we expected a weaker effect of delay on time-based PM relative to that of event-based PM due to the high semantic relatedness of the cue-intention pairings for time-based PM items on the MIST.

The other objective of the current study is to examine the impact of HIV disease and age on a naturalistic PM task. A review of the PM-aging literature suggests that older age is associated with better performance on performance-based naturalistic PM function indicators (e.g., McBride et al., 2013). Thus, we expected to find a main effect of age, such that older participants would perform better than their younger counterparts. The effect of HIV serostatus on naturalistic PM performance seems less clear. For example, Weber et al. (2011) reported no difference between HIV− and HIV+ groups. Furthermore, even in the HIV+ group with HAND, Doyle et al. (2013) found a trend level effect (p = .07). On the other hand, Carey et al. (2006) reported a main effect of HIV status on a similar naturalistic task. Hence, one objective of this study is to explore the effect of HIV on a naturalistic PM task in order to contribute to the discordant literature.

Finally, we plan to evaluate PM failures in everyday life (i.e., the Prospective and Retrospective Memory Questionnaire [PRMQ]; Smith et al., 2000) as they relate to age and HIV disease. Concerning the PRMQ and age related findings, it is of note that several studies (Crawford, Smith, Maylor, Della Sala, & Logie, 2003; Crawford, Henry, Ward, & Blake 2006; Smith et al., 2000) reported that there was no effect of age on PRMQ. Therefore, we do not expect to find age-related self-reported PM failures. On the other hand, we expect to find more PM complaints made by HIV+ individuals. For example, Woods et al. (2007) found out that HIV+ participants reported more frequent PM complaints in daily life than their seronegative counterparts.

In sum, we expect to find age and HIV effects on laboratory based PM assessment such that HIV+ and older adults will perform worse than their younger and seronegative counterparts. We expect these effects to be exacerbated in more demanding PM tasks (e.g., time-based PM, and long delay interval). In the naturalistic PM task, we expect that older adults will perform comparably, if not better, than younger participants. Since the findings regarding HIV+ effect on the naturalistic PM are equivocal, we will solely explore HIV-associated differences on this task. While we do not expect to find age-related differences in self-reported PM failures in everyday life, we do expect that HIV+ adults will report more PM failures in their daily lives. We also will investigate the potential additive or synergetic effect of age and HIV on each of the PM measures.

Method

Participants

The study sample consisted of 314 participants recruited from the San Diego community and local HIV clinics as part of an NIH-funded study on aging and memory in HIV disease. Participants were enrolled at baseline into one of four groups based on age (younger group ≤ 40 years, n = 125; older group ≥ 50 years, n = 189) and HIV serostatus, which was confirmed using standard Western blot and/or a point-of-care test (MedMira Inc., Nova Scotia, Canada) resulting in 189 HIV-seropositive (HIV+) individuals and 125 HIV-seronegative comparison individuals (HIV−). Exclusion criteria included having a severe psychiatric disorder (e.g., schizophrenia) or neuromedical condition including an active central nervous system opportunistic infection, a seizure disorder, head injury with loss of consciousness for more than 30 minutes, stroke with persistent neurological sequelae, non–HIV-associated dementia, and an estimated verbal IQ score < 70 on the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR; Psychological Corporation, 2001). Individuals were also excluded if they tested positive on a breathalyzer or urine toxicology screen for illicit drugs (except marijuana) on the day of testing. The participants’ demographic, psychiatric, and HIV disease and treatment characteristics are displayed in Table 1. Although the HIV+ groups were comparable to their seronegative counterparts in age, the Younger HIV+ group reported fewer years of education than the other three groups (ps < .05). The HIV+ groups included significantly higher proportions of men and were more likely to have diagnoses of affective disorders (i.e., depression and anxiety) than the seronegative groups (ps < .05). Hepatitis C virus (HCV) was more common in the Older groups than in the Younger groups, regardless of HIV status (p < .05). Regarding HIV disease and treatment variables, the Older HIV+ group had a longer duration of infection, lower nadir CD4 lymphocyte counts, and a higher prevalence of AIDS diagnoses than the Younger HIV+ sample (ps < .05), but did not differ in viral load, current CD4 count, or treatment characteristics (all ps > .10; see Table 1).

Table 1.

Cohort’s demographic, psychiatric, medical, and HIV disease characteristics.

| Younger HIV− (n = 48) |

Younger HIV+ (n = 77) |

Older HIV− (n = 77) |

Older HIV+ (n = 112) |

p | Group Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.2(.7) | 32.7(.5) | 56.2(.5) | 56.1(.5) | < .001 | Y−, Y+< O−, O+ |

| Education (years) | 14.1(.3) | 12.8(.2) | 13.9(.4) | 14.2(.2) | < .001 | Y+ < Y−, O−, O+ |

| Ethnicity (% white) | 43.8 | 40.3 | 66.2 | 68.8 | < .001 | Y−, Y+ < O−, O+ |

| Gender (% men) | 66.7 | 85.7 | 71.4 | 83.9 | < .001 | Y−, O− < Y+, O+ |

| Estimated Verbal IQ (WTAR) | 103.3(1.3) | 100.7(1.2) | 102.9(1.3) | 102.1(1.1) | – | – |

| Affective Disorders (%) | 29.2 | 72.7 | 45.5 | 68.8 | < .001 | Y−, O− < Y+, O+ |

| Substance Dependence (%) | 41.7 | 57.1 | 52.0 | 56.3 | – | – |

| HCV (%) | 4.2 | 5.3 | 21.1 | 32.1 | < .001 | Y−, Y+< O−, O+ |

| HIV Duration (months) | – | 87.5(7.9) | – | 202.1(8.9) | < .001 | Y+ < O+ |

| AIDS (%) | – | 35.5 | – | 65.2 | < .001 | Y+ < O+ |

| CD4 Count (cells/μL) | – | 589.8(30.4) | – | 579.0(29.0) | – | – |

| Nadir CD4 (cells/μL) | – | 279.1(20.5) | – | 182.1(16.0) | < .001 | O+ < Y+ |

| Prescribed cART Status (%) | – | 84.4 | – | 90.2 | – | – |

| RNA in Plasma Detectable (%) | – | 25.4 | – | 16.2 | – | – |

| Among Subjects on cART | – | 13.0 | – | 13.1 | – | – |

| 2-min Event Based PM1(%) | 71 | 82 | 47 | 54 | < .001 | Y−, Y+ > O−, O+ |

| 15-min Event Based PM1(%) | 63 | 47 | 27 | 20 | < .001 | Y− >Y+ > O−, O+ |

| 2-min Time Based PM1(%) | 81 | 75 | 53 | 46 | < .001 | Y−, Y+ > O−, O+ |

| 15-min Time Based PM1(%) | 29 | 14 | 4 | 4 | < .001 | Y− >Y+ > O−, O+ |

| 24-hour Trial (Pass) (%) | 29 | 32 | 48 | 28 | = .02 | O− > Y−, Y+, O+ |

Note. Data represents M (SE) or %. Younger ≤ 40 years; Older ≥ 50 years; WTAR = Wechsler Test of Adult Reading; HCV = Hepatitis C Virus; AIDS = Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; CD4 = Cluster of Differentiation 4; cART combination antiretroviral therapy.

The percentage of participants who received a score of 4 (the highest score in MIST subscales).

Materials and Procedure

The university’s human subjects committee approved this study. All participants provided written, informed consent prior to completing comprehensive medical, psychiatric, and neuropsychological research evaluations for which they received $35 financial compensation for the neurocognitive portion of the study.

Laboratory PM Measure

Participants were administered the research version of MIST (Raskin, et al. 2010), which is a standardized measure of PM with high internal reliability (Woods et al., 2008) and reasonable construct validity in both HIV infection (e.g., Carey et al., 2006) and aging (e.g., Kamat et al., 2014). Prior to administration of the MIST, participants were informed that the test would be examining their ability to remember tasks and carry them out. Participants were instructed to perform an ongoing distractor task (i.e., a standardized word search), and instructed to stop whatever they were doing when it was time to perform an assigned task. Participants were instructed that they could use a digital clock located behind them in order to keep track of time while completing the distractor task but the use of this clock was not explicitly encouraged (Huang et al., 2014). Administration of the MIST involved the participant sitting across from the examiner while the examiner verbally indicated event-based (e.g., “When I hand you a postcard, self-address it”) or time-based (e.g., “In 15 minutes, use that paper to write the number of medications you are currently taking”) cue directives to the participant. The MIST utilizes cue-intention pairings with high semantic relatedness for event-based directives (e.g., “When I show you a Request for Records form, write your doctors’ names on it”). Cues directives were verbally administered in sequential order at standardized intervals while the participant completed the ongoing distractor task. For example, after beginning the word search distractor task, participants were given an initial time-based cue directive (i.e., “In 15 minutes, tell me that it is time to take a break”), and then one min later given a separate event-based cue directive (i.e., “When I hand you a red pen, sign your name on your paper”). Then, 15 min after the initial time-based cue directive any verbal or action response by the participant was recorded (correct response would be “It is time to take a break”). 15 min after the initial event-based cue directive the participant was given a red pen and any verbal or action response was subsequently recorded (correct response would be signing their name on their paper). This method of administration is completed until all 8 trials of the MIST are administered, which in total takes approximately 25 minutes to administer. Note that intervals between cue directive and cue response for different trials overlap in the standardized administration of the MIST. Details regarding the standardized administration and details of order of cue-type (i.e., time-based, event-based), response modality (i.e., verbal, action), delay lengths (i.e., 2-minute, 15-minute), order of task presentation and execution, and cognitive load of tasks utilized for the present study are described in Woods et al. (2008).

Each trial on the MIST is worth two possible points: one point is awarded for a correct response and one point for responding (in some manner) at the appropriate time (± 18 seconds for 2-minute delay target; ± 135 seconds for 15-minute delay target) or to the appropriate cue. For example, if a participant is 3 minutes tardy in writing how many medications they are currently taking, only one point is awarded (for recalling the correct cue, but at the incorrect time) for that trial. Similarly, one point is earned if, for example, the participant incorrectly signs their name instead of correctly self-addressing the displayed postcard. For the present study, individual MIST trials contributed to two of the MIST’s four subscales as determined by each trial’s specific delay interval length (2-min, 15-min) and cue type (event-based, time-based), resulting in four delay-cue subscales (2-min event-based, 2-min time-based, 15-min event-based, 15-min time-based). Thus, each of the four delay-cue subscale scores consisted of two MIST trials and had scores ranging from 0–4, with higher scores reflecting better performance.

Naturalistic PM task

The naturalistic PM task was adapted from the MIST (Raskin et al., 2010; Woods et al., 2008). At the end of the experiment session, participants were instructed to leave a telephone message for the examiner the following day specifying the number of hours slept the night after the assessment. The use of mnemonic strategies such as electronic calendars was permitted, but not explicitly encouraged (Carey et al., 2006; Zogg et al., 2010). Participants were given full credit for completing the task if the correct message was left for the examiner the next day at the target time. Conversely, performance was scored as “incomplete” for the following conditions: (1) the participant did not leave any message, (2) did so at an incorrect time (≥15% of the target time; i.e., ±3 hours and 35 minutes), and/or (3) left a message without specifying the number of hours slept.

Self-perceived PM Symptoms in Daily Life

The PRMQ (Smith et al., 2000) has high internal reliability and construct validity (Crawford et al., 2003) and has been used in prior studies of HIV disease (e.g., Woods et al., 2007) and aging (e.g., Smith et al., 2000). The PRMQ consists of 16 questions about everyday memory errors (e.g., “Do you forget to buy something you planned to buy, like a birthday card, even when you see the shop?”). The questionnaire includes eight PM complaints, which are separated into further subscales: four short-term items, half of which are self-cued (e.g., “Do you decide to do something in a few minutes’ time and then forget to do it?”) and half environmentally-cued (e.g., “Do you intend to take something with you before leaving a room or going out, but minutes later leave it behind, even though it’s there in front of you?”). There also are four long-term PM items, half of which are self-cued (e.g., “Do you forget appointments if you are not prompted by someone else or by a reminder such as a calendar or diary?”) and the other half of which are environmentally‐cued (e.g., “Do you forget to buy something you planned to buy, like a birthday card, even when you see the shop?”). Participants are asked to rate how often each type of memory failure has occurred on a 5-point scale: Very Often, Quite Often, Sometimes, Rarely, or Never. Responses for PM errors were coded from 1 (never) to 5 (very often) for each item, resulting in a subscale score range between 2 and 10, with higher scores reflecting more frequent PM failures in daily life.

Medical evaluation

Participants were administered a brief medical evaluation conducted by a research nurse and included a review of systems, medications, history, urine toxicology, and a blood draw.

Psychiatric evaluation

Current (i.e., within the last 30 days) and lifetime affective disorders (i.e., Major Depressive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder) were evaluated via the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; version 2.128). Any individual meeting criteria for either current or lifetime MDD or GAD was classified as having an affective disorder (see Table 1). The CIDI also provided lifetime diagnoses of Substance Use Disorders.

Neuropsychological assessment

All participants were administered a comprehensive neuropsychological test battery that assessed the following domains: (1) learning, (2) delayed memory, (3) attention, (4) speed of information processing, (5) executive functions, and (6) motor skills. The measures for each domain included (1) the Logical Memory I subtest from the Wechsler Memory Scale, 3rd edition (WMS-III; Wechsler, 1997) and Total Trials 1–5 for the California Verbal Learning Test, 2nd edition (CVLT-II; Delis, Kaplan, & Kramer, 2000) for learning; (2) the Logical Memory II subtest from the WMS-III and the long Delay Free Recall trial for the CVLT II for delayed memory; (3) the Digit Span subtest from the WMS-III and Trial 1 from the CVLT-II for attention; (4) Trailmaking Test, Part A time (Army Individual Test Battery, 1944) and the Total Execution Time from the Tower of London Test (Drexel Version; Culbertson & Zillmer, 1999) for speed of processing; (5) Trailmaking Test, Part B time and the Total Moves score from the Tower of London Test for executive functions; and (6) Grooved Pegboard dominant and non-dominant hand completion time (Heaton et al., 2004; Klove, 1963) for motor skills. Raw scores from these measures were converted to demographically-adjusted normative T-scores, which were then converted to deficit scores (Carey et al., 2006) that range from 0 (T-scores >39) to 5 (T-scores <20). These deficit scores were averaged to derive a global deficit score (GDS) for which higher scores reflect greater general neurocognitive dysfunction; this approach is widely used to summarize neurocognitive functioning in the HIV literature.

Data Analysis

The effects of HIV serostatus and aging on MIST and PRMQ scores were evaluated with multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA). Although the MIST and PRMQ scores were non-normally distributed (i.e., negatively skewed) as determined by a Shapiro-Wilk W test (ps < .01), the results of the primary analysis did not change when a nonparametric approach to testing the statistical interaction was used. Since ANOVA-based tests are considered robust tests against normality assumption and there is no non–parametric corresponding test, MANOVA was determined to be the most appropriate statistical approach. Post-hoc tests were adjusted for multiple comparisons by using Tukey’s tests, which were complemented by Cohen’s d effect size estimates. The binary nature of the naturalistic PM task necessitated the use of logistic regression to predict the pass rate in this task. To determine covariates for these models, we considered only variables that related to both the independent and dependent variables at a critical alpha of .05. Of the 6 variables (i.e., education, ethnicity, sex, affective disorders, hepatitis C infection (HCV), and global neurocognitive impairment) that were associated with our fixed effects (see Table 1): 1) only HCV and neurocognitive impairment (i.e., General Deficit Score: GDS) were also associated with the MIST scores and therefore included in that model as fixed effects factors; 2) only affective disorder diagnosis and neurocognitive impairment (i.e., GDS) were associated with the PRMQ scores and were thus included as fixed effects factors in that model; and 3) only ethnicity and neurocognitive impairment (i.e., GDS) were associated with the naturalistic task and thus included in the logistic regression. Of note, the Shapiro-Wilk test of normality revealed that the data collected in MIST and PRMQ failed the assumption of normality of parametric tests (ps < .05). The analyses were conducted using the JMP statistical program and the critical alpha was set at .05.

Results

Laboratory PM: The Memory for Intentions Screening Test (MIST)

The model with age group, HIV, HCV, and GDS as between subject factors and 4 MIST subscales (PM cues: 2-min and 15-min delay intervals and event-based and time-based cues) as within–subjects factors yielded significant main effects of age (F(1, 309) = 74.48, p < .001, ηp2= .19), GDS (F(1, 309) = 66.23, p < .001, ηp2= .16), and PM cue (Pillai’s Trace = .12, F(3, 305) = 88.11, p < .01, ηp2= .33). Importantly, these main effects were tempered by significant interactions between age and PM cue (F(3, 307) = 3.44, p < .05, ηp2= .01, between HIV serostatus and PM cue (F(3, 307) = 2.75, p < .05, ηp2= .01), and between GDS and PM cue (F(3, 307) = 4.94, p < .01, ηp2= .02). None of the three way interactions reached significance, ps > .05. The results of planned post-hoc analyses of the significant 2-way interactions are displayed in Figures 1 and 2 and are detailed below.

Figure 1.

MIST performance as a function of age. Error bars indicate the standard error.

Figure 2.

MIST performance as a function of HIV status. Error bars indicate the standard error.

Age and MIST cue

Pairwise analyses showed that younger participants performed better than older adults in all conditions: 2-min event-based, 15-min event-based, 2-min time-based, and 15-min time-based (ps < .001). The magnitude of the age and the delay interaction differed by the cue type. For event-based cues, the effect of age was comparable on both 2- and 15-min delays (ds = .67). For time-based cues, however, there was a 30% larger effect of age on the 15-min delay (d = .75) than on the 2-min delay (d = .58; See Figure 1).

HIV and MIST cue

Pairwise analyses showed that the HIV+ groups did not differ on event-based MIST performance for the 2–min delay (p > .05, d = .17). For the rest of MIST subscales, the HIV− group performed better than the HIV+ group: 15-min event-based, 2-min time-based, and 15-min time-based (ps < .05; See Figure 2). The largest effect size was observed in 15-min time-based cue (d = .67), which was followed by small effect sizes for the 15-min event-based (d = .30) and 2-min time-based (d = .14) cue scores.

Neurocognitive impairment and MIST cue

Pairwise analyses showed that participants whose GDS was within normal limits performed better than the participants with neuropsychological impairment in all MIST subscales: 2-min event-based, 15-min event-based, 2-min time-based, and 15-min time-based (ps < .001). The magnitude of the GDS associations with PM cues differed by the delay interval. In 2-min delay, the GDS had comparable medium effects across event- (d = .49) and time-based (d = .54) cues. For 15-min delay, however, there was a very large effect of GDS impairment on time-based cues (d = 1.04) that was 79% larger than the medium effect of GDS on event-based cues (d = .58; See Figure 3).

Figure 3.

MIST performance as a function of General Deficit Score. Error bars indicate the standard error.

Ongoing task performance and MIST cue

The performance on the ongoing task (i.e., the number of words found by the participants) was analyzed as a function of age and HIV status. We found a significant effect of age (F(1,312)= 135.75, p < .001, ηp2= .30); younger participants (M = 21.14, SE = .52) outperformed older participants (M = 13.23, SE = .53). As might be anticipated, there was a decline in the number of words correctly located as age increased. No effect of HIV was found (p > .05). There was no difference between Young HIV− and Young HIV+ and between Old HIV− and Old HIV+ (ps > .05). To explore the relationships between the performance on the ongoing task and MIST scores, we employed spearman correlational analyses. Correlations between distractor performance and MIST scores were significant (ps < .05). Contrary to the expectations of a trade-off, we found a positive relationship between the performance on the ongoing task and PM task: the greater the ongoing performance, the greater PM performance. In this respect we can safely eliminate the hypothesis that individuals could be sacrificing ongoing task performance to increase PM performance.

Memory error types in MIST

Each trial on the MIST is worth two possible points: one point is awarded for a correct response and one point for responding (in some manner) at the appropriate time (± 15% of the target) or to the appropriate cue. No response errors (i.e., omission errors) are presumed to be directly due to failure of PM (i.e., cue detection). To confirm that retrospective memory performance did not explain our findings, we conducted a separate analysis paralleling the primary statistical model. Instead of MIST subscale scores, we analyzed the error type “prospective memory failure” wherein the participant exhibits a complete failure to recall the prompt and provides no response. The model with age group, HIV, HCV, and GDS as between subject factors and PM failures in MIST subscales as within subjects factors yielded significant main effects of age (F(1, 307) = 27.51, p < .001, ηp2= .07), GDS (F(1, 307) = 34.16, p < .001, ηp2= .10), and PM cue (Pillai’s Trace = .15, F(3, 307) = 6.98, p < .01, ηp2= .02). Importantly, these main effects were tempered by significant interactions between age and PM cue (F(3, 307) = 5.61, p < .001, ηp2= .02) and between GDS and PM cue (F(3, 303) = 7.58, p < .001, ηp2= .02). The similar pattern reassured us that the effects were driven by omission errors (i.e., prospective memory errors).

The Semi-Naturalistic PM Task

A logistic regression analysis was conducted to predict the pass rate in the 24-hour trial using HIV, age, and the interaction between HIV and age. The model also included ethnicity and GDS as predictors since these variables were associated with our fixed effects. A test of the full model against a constant only model was statistically significant (χ2 (5, N=314) =17.96, p = .003) indicating that the predictors as a set reliably predicted success rate on 24-hour trial. Ethnicity (χ2 (1, N=314) = 4.68, p = .03) and the HIV and age interaction (χ2 (1, N=314) = 4.79, p = .023) each significantly contributed to the model. No other predictor variable was associated with naturalistic task performance (all other ps > .05). Post-hoc analysis indicated that older HIV− adults had significantly greater odds of successfully complete the naturalistic PM task as compared to Young HIV−, Young HIV+, and Older HIV+ groups (odds ratios range = 1.9, 95% CI [1.1, 3.7] to 2.4, 95% CI [1.3, 4.5]). These data are displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

24-hour Task performance as a function of age and HIV status. Error bars indicate the standard error.

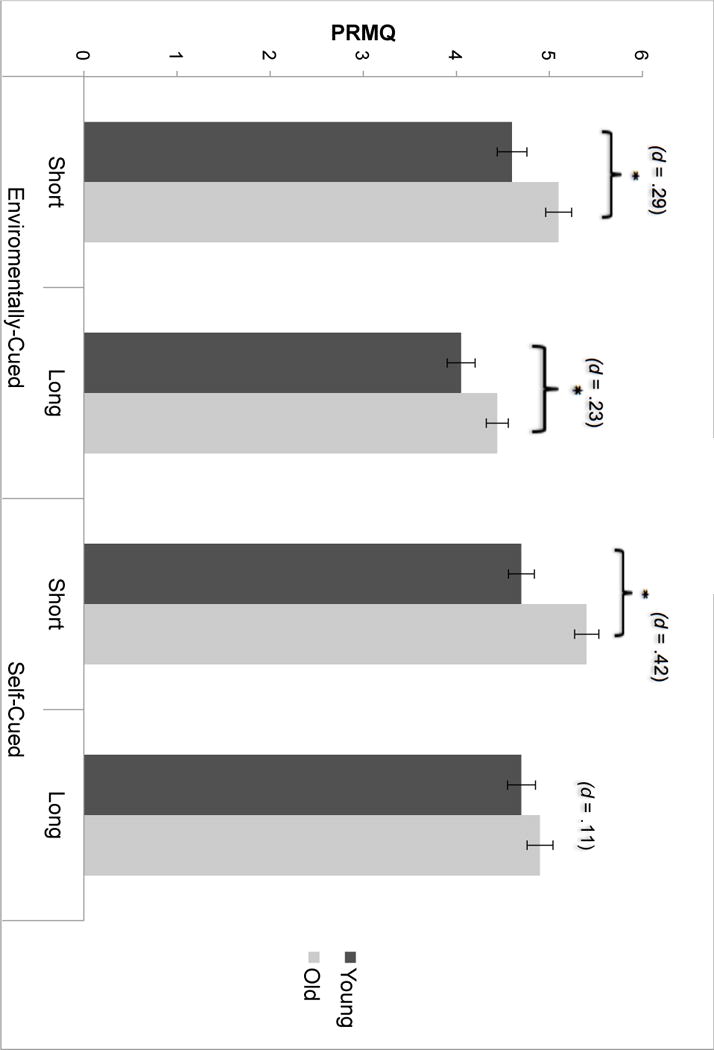

The Prospective and Retrospective Memory Questionnaire (PRMQ)

The model yielded significant main effects of HIV (F(1, 308) = 4.30, p = .04, ηp2= .01), Affective Disorders (F(1, 308) = 43.47, p < .001, ηp2= .12) and the PRMQ subscales (Pillai’s Trace = .08, F(3, 308) = 23.64, p < .001, ηp2= .07). The main effect of age was marginally significant (p = .07, ηp2= .01). The interactions between age and HIV (F(1, 308) = 5.52, p = .02, ηp2= .02), between PRMQ subscales and age (F(3, 306) = 2.95, p = .04, ηp2= .01), and between PRMQ subscales and HIV (F(3, 306) = 3.54, p = .02, ηp2= .01) were significant. The results of planned post-hoc analyses for these interaction terms are detailed below and are displayed in Figures 5 and 6.

Figure 5.

PRMQ performance as a function of age. Error bars indicate the standard error.

Figure 6.

PRMQ performance as a function of HIV status. Error bars indicate the standard error.

Age and PRMQ subscales

Pairwise analyses showed that older participants reported more PM complaints than younger participants in three subscales of PRMQ, short-delay environmentally-cued, long-delay environmentally-cued, and short-delay self-cued (ps < .05); however, the difference was not significant for the long-delay self-cued subscale (p >.05, d = .11; See Figure 4). The magnitude of the age difference was the greatest for the short‐delay self-cued items, which showed a medium effect (d = .42). By way of comparison, the magnitude of the age differences in environmentally-cued short-delay (d = .29) and long-delay (d = .23) subscales were generally small and similar in magnitude.

HIV and PRMQ subscales

Pairwise analysis showed that the HIV+ group reported more frequent PM failures than HIV- participants in all subscales of PRMQ: short-delay environmentally-cued, long-delay environmentally-cued, short-delay self-cued, and long-delay self-cued subscales (ps < .002; See Figure 5). The effect size was the greatest in long-delay self-cued subscale (d = .68), whereas the remaining three subscales had broadly small-to-medium effect sizes, including short-delay environmentally-cued (d = .49), short-delayed self-cued (d = .42), and long-delay environmentally-cued (d = .37).

Discussion

There is a rising prevalence of older HIV+ adults who are at high risk of having deficits in higher-order neurocognitive functions such as PM (e.g., Woods et al., 2010), which are associated with problems in everyday functioning (e.g., Morgan et al., 2012). As such, understanding the cognitive architecture of PM declines in the context of HIV infection and older age is important in an effort to guide neuropsychological rehabilitation strategies for maximizing functional independence. The current study examined the independent and combined effects of aging and HIV on PM across measures of laboratory, naturalistic, and self-perceived symptoms and as a function of cue retrieval type and delay interval. The empirical findings revealed by the present study extend the literature in several important ways. First, we report that the effects of aging can vary by a function of the strategic demands of cue type and delay interval length as manipulated in the laboratory (i.e., MIST). Second, this is the first paper to have reported an interaction between HIV disease and age on a semi-naturalistic PM task—with older adults without HIV performing the best. Third, these aforementioned effects of HIV and age were shown to be statistically independent of global neurocognitive deficits, including robust clinical measures of retrospective memory and executive functions. Fourth, the effect of age on PM across delay and cue type were observed in a much younger cohort (i.e., persons in their 50s) than has been reported in prior studies of aging and PM. Finally, we replicated previous findings showing that the effect of HIV on the MIST varies as a function of cue type and delay interval length. The scientific value of exact replication in establishing the reliability of this effect, especially regarding empirical questions of data that may be utilized for clinical decision-making, has received increased attention in the psychological literature (Pashler & Wagenmakers, 2012; Yong, 2012).

A major contribution of this study is the finding that the effects of aging on laboratory-measured PM varied by the delay interval and cue type. Specifically, the interaction between aging and PM cue and delay on the MIST indicated that effects of older age were comparable across short and long delay intervals for event-based PM; however, for the time-based PM scales, the age effects were amplified on longer delay intervals. This finding converges with previous studies showing that time-based tasks and long-delay intervals are more susceptible to the effects of aging (e.g., Martin et al. 2011; Woods et al., 2010). Previous research reported that time-based tasks and longer intervals demand more cognitive resources for execution and older adults are significantly less efficient at engaging strategic encoding and retrieval process required to perform PM tasks (e.g., Kelly, Hertzog, Hayes, & Smith, 2014; Martin et al., 2011; Woods et al., 2010). This pattern of findings is consistent with the Multiprocess model, which posits that the length of time between intention formation and execution of the intention may influence PM performance with all other things being equal. Longer delays may necessitate more strategic control by placing greater demands on limited executive resources supporting cue detection and monitoring; therefore, performance suffers as delay length increases and strategic processes may fail (McDaniel & Einstein, 2000).

The effect of HIV status on PM was evident in all MIST cue/delay scales except in the event-based 2-min delay condition. This finding can be interpreted within the context of the Multiprocess model, which postulates that PM retrieval can depend on strategic attention-demanding processes or spontaneous retrieval processes. We suspect that individuals could have had a greater probability to rely on spontaneous retrieval, rather than sustained executive attentional processes, when under the event-based 2-min delay conditions.

To examine this argument at the conceptual level, we employed Spearman’s rho correlations to examine the associations between the MIST subscale scores and measures selected from the comprehensive neuropsychological battery in order to provide evidence for the automatic/spontaneous vs. strategic components (e.g., executive, memory, and attention) of PM. In general, 2-min event-based PM was not correlated with any cognitive domains, while the other MIST scales (particularly the 2 min and 15 time-based MIST scales) were correlated with these cognitive, relatively strategic domains, which suggests that 2-min event-based tasks are not controlled by top-down, individual driven attentional resources. Rather, these findings indirectly indicate that it is spontaneous retrieval that may be driving our observed findings. Thus, we argue that HIV- adults’ performance was comparable to their older seronegative counterparts in 2-min event-based PM, which is purportedly driven by spontaneous retrieval. These effects might be due to neural burden of HIV in prefrontal systems (Jernigan et al., 2005) involved in higher-level cognitive control processes (e.g., Khanlou et al, 2009).

The presently observed trend-like effect of aging on PRMQ was unexpected. However, several studies (Crawford et al., 2003, 2006; Smith et al., 2000) reported that there was no effect of age on any of the scales of the PRMQ. Therefore, the present research is consistent with other evidence that suggests that older individuals do not show a decline in their self- or proxy-rated PM. However, we agree that the failure to find an age effect on PRMQ scores runs somewhat contrary to existing research (i.e., age paradox). It has been suggested that the absence of age effects on PM failures in daily life may be at least partially attributable to the external aids to cue the PM event. However, PRMQ items allow for controlling for whether prospective remembering has been supported by external reminders (e.g., ‘Do you forget appointments if they are not prompted by someone else or by a reminder such as a calendar or diary?’). Despite controlling for this factor, no age-related deficit has been reported in the literature, nor found in the present study. To explain this unanticipated finding, Crawford et al. (2006) proposed that the absence of age effects across measures of both self-report and proxy reports of PM (Crawford et al., 2003; Smith et al., 2000) reflects the tendency to rate their PM memory performance relative to a participant’s peers (see Rabbitt, Maylor, McInnes, Bent, & Moore, 1995). Hence, we also propose that the absence of an age effect on this measure might reflect participant’s judgment of his/her PM performance relative to his/her peers. In contrast to the aging findings detailed above, we found an effect of HIV serostatus, such that HIV+ adults reported more PM memory failures than did their seronegative counterparts, which also has been reported in previous studies (e.g., Woods et al., 2007).

The significant interaction between HIV disease and age on a semi-naturalistic PM task, with older adults without HIV performing the best, was one of the most interesting findings of the study. The literature on PM and aging studies indicate that older age is associated with better performance on this type of naturalistic PM task (e.g., Henry et al., 2004; but see Kvavilashvili & Fisher, 2007). Also, one might expect that HIV+ individuals would perform the best because it would be important for them to learn compensatory strategies in order to help mitigate some difficulties they might experience in everyday life. However, we found that older adults performed better than younger adults on a naturalistic PM task only if they were not infected with HIV. For participants living with HIV disease, age had no impact on naturalistic PM, which may be a function of older adults being more likely to use compensatory strategies (Weber et al., 2011) as these strategies are compromised in older adults living with HIV. In this regard, it can be speculated that routine lifestyles and decreased busyness often experienced by older seronegative adults may be a contributing factor to the superior performance in the naturalistic PM tasks observed for this cohort. However, HIV infection may increase the monitoring demands for PM in longer delays due to relatively more hectic life style (e.g., more doctor appointments, increased numbers of medications), which may impair their naturalistic PM task performance. In support of this, research suggest that older adults experience increased motivation to perform naturalistic compared to laboratory PM tasks (Aberle et al., 2010), utilize a higher number of reminders (Rendell & Thomson, 1999), and lead more structured lives (Bailey et al., 2010). We might expect similar compensatory strategies employed by HIV+ group. Indeed, it was reported that while older HIV+ group performed significantly worse than younger HIV+ group on the lab-based portion of the MIST, the older group performed comparably to the younger group on the naturalistic task. Further, older HIV+ participants who successfully completed the naturalistic task reported using more PM-based and external mnemonic strategies (Weber et al., 2011). Whether the prospective use of external reminding aids that minimize strategic time monitoring demands (e.g., context-free cueing) actually improve HIV-associated PM deficits in daily life remains to be explored further.

Another contribution of this study is the observation that the age effects on PM are apparent in a fairly young cohort of “older” adults (M age = 56 years) as compared to a fairly old cohort of “younger” adults (M age = 32 years). Typical aging studies often compare adults aged 65 years and older to younger adults, who are typically undergraduate students in their early 20s (e.g., Aberle et al., 2010; Einstein, Smith, McDaniel, & Shaw, 1997; Einstein, McDaniel, Manzi, Cochran, & Baker, 2000; Juan, Juan, Jose, & Jose, 2013). As stated above, the age classification in the study was driven by the epidemiology of HIV infection and recommendations of the NIH aging research taskforce (Stoff et al., 2004): less than 5% of the entire HIV population in the US is 65+ years of age (CDC, 2014), which is a similar proportion observed in this study (i.e., 5%). In the same way, very few persons with HIV disease are 20 years or younger (CDC, 2014). Not only is the current study’s use of a 10-year age-gap grouping in line with our prior studies (e.g., Weber et al., 2011; Woods et al., 2010), which also reported that PM failures become more prominent after 50 years of age, but our age grouping methodology also provided an ecologically relevant, feasible, and methodologically sound means of testing age-related hypotheses in HIV disease. Further, this study design conforms to those recommended by NIH. We accept that this unconventional age cut-off might raise the question of whether the oldest participants within the Older group are driving the age-related findings. To examine evidence for this explanation, we employed an additional analysis excluding older participants (65 and over) while retaining the lower-bound age cutoff (50). We still obtained the similar interactions. Moreover the effect sizes in the new model were greater than the original model with 15-minute time-based scale still generating the greatest effect size. Thus, our data suggest that medium to large effects of older age are demonstrable during the 6th decade of life, even on short-delay event-based PM tasks with relatively modest cognitive demands. The precipitous occurrence of age-related PM problems is unlikely to be solely an artifact of mild neurocognitive deficits due to HIV, HCV, and/or drugs, since these factors (either statistically or by way of group matching) were controlled in the analysis. Thus, our study suggests that PM may start to deteriorate with age much earlier than has been previously reported. In support of this hypothesis, similar observations of declines in middle-age have been made in other higher-order cognitive domains, such as retrospective memory and executive functions (Deary et al., 2009).

Although it was not the main focus of the present study, the effect of covariates (i.e., neurocognitive impairment and affective disorders) deserves discussion. We found that the aforementioned age- and HIV-associated PM deficits on PM were independent of the effects of neurocognitive impairment, which generated notable effects sizes, ranging between .49 and 1.04. Since neurocognitive impairment was quantified by cognitive domains that are critical to PM functioning (e.g., retrospective memory, executive functions, and processing speed), and since these domains are often affected in HIV and aging, our findings offer important evidence for possibly dissociable mechanisms underlying PM decline and more global cognitive deficits. This finding indicates that PM deficits revealed in this study are not simply artifact of declines in other cognitive domains. Rather, it is a unique and separate domain, as further evidenced by its unique relationships with everyday functioning outcomes (e.g., Woods et al., 2009). Identifying the psychiatric and cognitive determinants of self-reported PM complaints in HIV is important for understanding the PM deficits and accordingly tailoring PM intervention strategies for this vulnerable group. We reported that affective states predicted PRMQ scores, which has been reported by previous research. For example, Woods et al. (2007, 2008) reported that higher self-reported levels of current anxiety, depression, and fatigue were associated with increased frequency of PM complaints. It seems that affective distress is a primary contributor to the self-reported PM deficit. At this point, we can only speculate that affective stress might place substantial demands on self-initiated monitoring and retrieval strategies. As one source of the affective stress, fatigue is common in persons with HIV infection and is associated with depression, poorer health-related quality of life, and greater functional disability.

As one of the limitations of the study, limited number of trials in each subscale/measures (i.e., 2 trials per scale in both MIST and PRMQ, and one observation in the naturalistic task) raises concerns about the stability of each measure. Of note, the relatively few number of trials is a chronic problem in PM research, which is a function of the nature of the construct that requires a sufficient delay in between the formation and the execution of the intention. Indeed, many laboratory-based PM measures are commonly criticized as having too many trials without sufficient spacing, thereby perhaps reflecting measures of sustained/divided attention rather than PM per se (Brandimonte, Ferrante, Feresin, & Delbello, 2001). The MIST, on the other hand, is a well-validated clinical PM measure that demonstrates evidence of construct validity in both HIV (Carey et al., 2006; Woods et al., 2006; 2007) and aging (e.g., Kamat et al., 2014; Woods et al., 2013, 2014). Further, scales on the MIST demonstrate evidence of convergent (e.g., Morgan et al., 2012) and ecological (Poquette et al., 2013) validity in both HIV and substance abuse (Weinborn et al., 2011). Perhaps even more important than these validity measures is the fact that the current findings regarding the MIST’s PM delay scales replicate previous studies by showing a main effect of HIV disease. Such findings, we believe, show the applied stability of the measure. Furthermore, the subscales demonstrate acceptable reliability (Woods et al., 2008). The MIST has also been shown to predict a variety of real-word behavioral outcomes across a variety of clinical populations, including individuals with Parkinson’s disease (Raskin et al., 2011), schizophrenia (Twamley et al., 2008), traumatic brain injury (Tay, Ang, Lau, Meyyappan, & Collinson, 2010), amnestic mild cognitive impairment (Karantzoulis, Troyer, & Rich, 2009), and substance use disorders (Iudicello et al., 2011).

The PRMQ, as a self-report of PM symptoms, may reflect a variety of other factors, including actual performance, ability, self-efficacy, and mood. Nevertheless, the PMRQ has been widely used both in healthy and clinical populations (e.g., Smith 2000; Weinborn et al, 2011; Woods et al., 2007). Crawford et al. (2003) reported high internal reliability and construct validity of the PRMQ. Prospective memory performance was predicted by the prospective memory subscales of the PRMQ (Kliegel & Jager, 2006). Furthermore, distinct aspects of metamemory were found to relate to actual prospective memory performance and to the scores of the PRMQ, providing cross-validation for the PRMQ. Based on the literature and our replication of the previous findings, we are convinced that the PRMQ proves to be reliable self-report measure of prospective memory failures.

Similarly, the various PRMQ subscales have been shown to be predictive of real-world outcomes in HIV (e.g., Woods et al., 2008) and aging (Woods et al., 2013; 2014) and has been widely used both in healthy and clinical populations (e.g., Smith 2000; Weinborn et al, 2011; Woods et al., 2007) with high internal reliability and construct validity (Crawford et al., 2003). Concordantly, we are certain that our measures prove to be reliable and valid measures of PM.

Regarding the naturalistic task (24-hour trial), we acknowledge that one observation is not ideal for stability of a PM measure. We also acknowledge it is not necessarily harmful for a PM task to be realistically anchored in the types of day-to-day activities in which our patients engage. When interpreted in the context of the MIST and PRMQ data, this naturalistic approach gives us an ecologically relevant depiction of PM phenomenon in everyday life that complements the lab-based and self-report data. Thus, this study allows us to look at the phenomenon of PM through multiple lenses. This approach (i.e., one observation of prospective memory in a natural setting) has been adopted by other researchers in healthy (e.g., Kvavilashvili & Fisher, 2007; McBride, Coane, Drwal, & LaRose, 2013) and HIV-infected populations (Weber et al., 2011; Woods et al., 2008; Zogg et al., 2011). Moreover it has been reported that the performance in this task (fail/pass) predicted real world behavioral outcomes in HIV population (Woods et al., 2008; Zogg et al., 2011). In the broader neuropsychological literature on ecological validity, which struggles to strike the appropriate balance between experimental control and accurately reflecting the complexities of daily life (see Chaytor & Schmitter-Edgecombe, 2003 for a review), the 24-hour trial of the MIST differs procedurally from the rest of the test items.

The external validity of the study is limited by the recruitment of largely male, Caucasian sample, so the extent to which these findings generalize to women and ethnic minorities remains to be determined. Also, one might note that the delay intervals manipulated in the present study do not reflect real life-time PM tasks, because the MIST includes only 2- and 15- min delays, while real-life time delays are typically more variable and may be on average longer. However, there are real-life delays of 2- and 15-min (e.g., checking the food in the oven, remembering to take medication in 15 min), and therefore this task may accurately map on to some daily functioning outcomes. One possible improvement to the laboratory based PM tasks might be to examine the role of compensatory strategies. For example, many individuals commonly tend to take notes or create a personalized form of reminder, and MIST does not allow for this possibility. This would be a fruitful area for further work. Pertinently, future research should also concentrate on the investigation of the development of memory strategies to improve PM (e.g., rehearsal of the intended action, strategic monitoring, etc).

This study aimed to shed light on PM deficits experienced by people living with HIV, which may be similar to the prospective memory demands in everyday lives of HIV patients. For example, Poquette et al. (2013) observed that laboratory-based deficits in longer time-based PM delay intervals were uniquely predictive of non-adherence to prescribed cART regimens. Meta-analyses of PM research in laboratory settings have indicated that older age is associated with moderate declines in performance on time-based PM tasks and more strategically demanding event-based PM tasks (Henry et al., 2004; Kliegel et al., 2008), which may increase the risk of deficits in real-world outcomes such as self-reported medication adherence (Woods et al., 2014). Limitations notwithstanding, our use of a well-characterized cohort and standardized performance-based measures underscores the importance of exploring PM deficits in HIV and the need for improvement of the ecological validity of PM evaluations and of remediating memory strategies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Grants R01-MH073419, T32-DA31098, L30-DA0321202, P30-MH62512 and K24-AG026431.

The San Diego HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program [HNRP] group is affiliated with the University of California, San Diego, the Naval Hospital, San Diego, and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, and includes: Director: Igor Grant, M.D.; Co-Directors: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D., and J. Allen McCutchan, M.D.; Center Manager: Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D.; Jennifer Marquie-Beck, M.P.H.; Melanie Sherman; Neuromedical Component: Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D. (P.I.), J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., Scott Letendre, M.D., Edmund Capparelli, Pharm.D., Rachel Schrier, Ph.D., Debra Rosario, M.P.H., Neurobehavioral Component: Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D. (P.I.), Mariana Cherner, Ph.D., Jennifer E. Iudicello, Ph.D., David J. Moore, Ph.D., Erin E. Morgan, Ph.D., Matthew Dawson; Neuroimaging Component: Terry Jernigan, Ph.D. (P.I.), Christine Fennema-Notestine, Ph.D., Sarah L. Archibald, M.A., John Hesselink, M.D., Jacopo Annese, Ph.D., Michael J. Taylor, Ph.D.; Neurobiology Component: Eliezer Masliah, M.D. (P.I.), Cristian Achim, M.D., Ph.D., Ian Everall, FRCPsych., FRCPath., Ph.D. (Consultant); Neurovirology Component: Douglas Richman, M.D., (P.I.), David M. Smith, M.D.; International Component: J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., (P.I.); Developmental Component: Cristian Achim, M.D., Ph.D.; (P.I.), Stuart Lipton, M.D., Ph.D.; Participant Accrual and Retention Unit: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D. (P.I.); Data Management Unit: Anthony C. Gamst, Ph.D. (P.I.), Clint Cushman (Data Systems Manager); Statistics Unit: Ian Abramson, Ph.D. (P.I.), Florin Vaida, Ph.D., Reena Deutsch, Ph.D., Anya Umlauf, M.S.

The authors thank Marizela Cameron and P. Katie Riggs for their help with study management and Donald Franklin and Stephanie Corkran for their help with data processing.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest related to this work. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the United States Government.

References

- Aberle I, Rendell PG, Rose NS, McDaniel MA, Kliegel M. The age prospective memory paradox: Young adults may not give their best outside of the lab. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:1444–1453. doi: 10.1037/a0020718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manual of directions and scoring. Washington, DC: War Department, Adjutant General’s Office; 1944. Army Individual Test Battery. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey PE, Henry JD, Rendell PG, Phillips LH, Kliegel M. Dismantling the “age-prospective memory paradox”: The classic laboratory paradigm simulated in a naturalistic setting. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2010;63:646–652. doi: 10.1080/17470210903521797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandimonte MA, Ferrante D, Feresin C, Delbello R. Dissociating prospective memory from vigilance processes. Psicológica. 2001;22:97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Carey CL, Woods SP, Rippeth JD, Heaton RK, Grant I, The HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center (HNRC) Group Prospective memory in HIV-1 infection. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2006;28:536–548. doi: 10.1080/13803390590949494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford JR, Smith G, Maylor EA, Della Sala S, Logie RH. The Prospective and retrospective memory questionnaire (PRMQ): Normative data and latent structure in a large non-clinical sample. Memory. 2003;11(3):261–275. doi: 10.1080/09658210244000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford JR, Henry JD, Ward AL, Blake J. The Prospective and Retrospective Memory Questionnaire (PRMQ): Latent structure, normative data and discrepancy analysis for proxy-ratings. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;45:83–104. doi: 10.1348/014466505X28748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbertson WC, Zillmer EA. The Tower of London, Drexel University, research version: Examiner’s manual. North Tonawanda: Multi-Health Systems; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Deary IJ, Corley J, Gow AJ, Harris SE, Houlihan LM, Marioni RE, Penke L, Rafnsson SB, Starr JM. Age-associated cognitive decline. British Medical Bulletin. 2009;92:135–52. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldp033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle K, Loft S, Morgan EE, Weber E, Cushman C, Johston E, Grant I, Woods SP, The HNRP Group Prospective memory in HIV-associated Neurocognitive Disorders (HAND): The neuropsychological dynamics of time monitoring. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2013;35:359–72. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2013.776010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein GO, McDaniel MA. Normal aging and prospective memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1990;16:717–726. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.16.4.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein GO, McDaniel MA. Prospective memory and what costs do not reveal about retrieval processes: A commentary on Smith, Hunt, McVay, and McConnell (2007) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2010;36:1082–1088. doi: 10.1037/a0019184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein GO, McDaniel MA, Manzi M, Cochran B, Baker M. Prospective memory and aging: Forgetting intentions over short delays. Psychology and Aging. 2000;15:671–683. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.15.4.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein GO, Smith RE, McDaniel MA, Shaw P. Aging and prospective memory: The influence of increased task demands at encoding and retrieval. Psychology and Aging. 1997;12:479–488. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.12.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enrique P, Juan JGM, Juan C, Jose AS, Jose MA. Effects of age on performance of prospective memory tasks differing according to task type, difficulty and degree of interference. Journal of Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2013:S7:001. doi: 10.4172/2161-0487.S7-001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst T, Chang L. Effect of aging on brain metabolism in antiretroviral-naïve HIV patients. AIDS. 2004;18(Suppl 1):61–67. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2011.604027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz MB, Boscardin WJ, Wiley D, Alkasspooles S. Decreased recovery of CD4 lymphocytes in older HIV-infected patients beginning highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2001;15:1576–1579. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108170-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DA, Masliah E, Vinters HV, Beizai P, Moore DJ, Achim CL. Brain deposition of beta-amyloid is a common pathologic feature in HIV positive patients. AIDS. 2005;19(4):407–11. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000161770.06158.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heathcote A, Loft S, Remington R. Slow down and remember to remember! A delay theory of prospective memory costs. Psychological Review. 2015;122:376–384. doi: 10.10.1037/a0038952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, Mindt MR, Sadek J, Moore DJ, Bentley H, The HNRC Group The impact of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment on everyday functioning. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society: JINS. 2004;10(3):317–331. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704102130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, MacLeod M, Phillips L, Crawford JR. A meta-analytic review of prospective memory and aging. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:27–39. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks JL, Marsh RL, Russell EJ. The properties of retention intervals and their affect on retaining prospective memories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2000;25:1160–1169. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.26.5.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin CH, Hardy DJ, Mason KI, Castellon SA, Durvasula RS, Lam MN, Stefaniak M. Medication adherence in HIV-infected adults: Effect of patient age, cognitive status, and substance abuse. AIDS. 2004;18(Suppl 1):19–25. doi: 10.1077/00002030-200401001-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg RS, Heath KV, Yip B, Craib KJ, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT, et al. Improved survival among HIV-infected individuals following initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279(6):450–454. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.6.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T, Loft S, Humphreys MS. Internalizing versus externalizing control: Different ways to perform a time-based prospective memory task. Journal Of Educational Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2014;40:1064–1071. doi: 10.1037/a0035786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iudicello JE, Weber E, Grant I, Weinborn M, Woods SP, HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center (HNRC) Group Misremembering future intentions in methamphetamine-dependent individuals. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 2011;25(2):269–286. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2010.546812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks A, Wainwright D, Salazar L, Grimes R, York M, Strutt AM, Shahani L, Woods SP, Hasbun R. Neurocognitive deficits increase risk of poor retention in care among older adults with newly diagnosed HIV infection. AIDS. 2015;29(13):1711–1714. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan TL, Gamst AC, Archibald SL, Fennema-Notestine C, Mindt MR, Marcotte TD, Heaton RK, Ellis RJ, Grant I. Effects of methamphetamine dependence and HIV infection on cerebral morphology. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1461–72. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamat R, Weinborn M, Kellogg EJ, Bucks RS, Velnoweth A, Woods SP. Construct Validity of the memory for Intentions Screening Test (MIST) in healthy older adults. Assessment. 2014;21:742–753. doi: 10.1177/1073191114530774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karantzoulis S, Troyer AK, Rich JB. Prospective memory in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society: JINS. 2009;15(3):407–415. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709090596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, Hertzog C, Hayes MG, Smith AD. The effects of age and focality on delay-execute prospective memory. Neuropsychology, development, and cognition. Section B, Aging, neuropsychology and cognition. 2013;20(1):101–124. doi: 10.1080/13825585.2012.69115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanlou N, Moore DJ, Chana G, Cherner M, Lazzaretto D, Dawes S, et al. Increased frequency of alpha-synuclein in the substantia nigra in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Journal of Neurovirology. 2009;15(2):131–8. doi: 10.1080/13550280802578075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliegel M, McDaniel MA, Einstein GO, editors. Prospective memory: Cognitive, neuroscience, developmental, and applied perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]