Abstract

Despite annual recommendations, American adults remain inadequately vaccinated. The author outlines how compliance may be improved through health care professional interventions, as well as government and community-based programs.

This is the second in a series of two articles about childhood and adult immunization in the United States. Part 1 appeared in the July 2016 issue of P&T and discussed the recommendations, barriers, and measures to improve compliance concerning childhood vaccinations.

INTRODUCTION

Vaccines are among the greatest achievements in medicine and public health.1 The incidence, prevalence, morbidity, and mortality of vaccine-preventable diseases have drastically decreased since vaccinations became available at the end of the 18th century.1–6 In the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices (ACIP) routinely publishes recommendations for adult and childhood vaccination.7–8 The standard vaccines recommended by ACIP for adults vary according to age (18–65 years and older than 65 years), and currently include immunization against: influenza, tetanus-diphtheria, tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis, varicella, human papillomavirus (HPV), herpes zoster, measles-mumps-rubella, and Streptococcus pneumoniae.5,7,8 Despite the issuance of these recommendations, American adults remain inadequately vaccinated.2–5,9 Several factors contribute to adult vaccination noncompliance, including low priority, lack of information, fear or opposition to vaccines, cost, accessibility, and operational or systemic barriers.3–5,10 Proven measures to improve vaccine compliance can be undertaken by health care professionals (including retail and health system pharmacists), government programs, and community organizations.2–5,7,9,11–14

IMPACT OF VACCINES

Without question, vaccines are among the greatest achievements in medicine and public health.1 In fact, the CDC has named the development of vaccines as one of the top 10 public health achievements during the 20th century.2 The incidence, prevalence, morbidity, and mortality of vaccine-preventable diseases have drastically decreased since vaccinations became available at the end of the 18th century.2,6 Since 1924, it is estimated that vaccines have prevented more than 100 million cases of smallpox, measles, polio, rubella, mumps, hepatitis A, diphtheria, and pertussis.4 Between 1980 and the present alone, a greater than 92% reduction in cases and 99% decline in deaths have occurred compared to the prevaccine eras.2 Because of vaccines, the endemic transmission of rubella and polio has been eradicated in the United States, and smallpox has been eliminated worldwide.2 Prevention of infectious diseases provides significant health and economic benefits to both individuals and populations, making vaccination a highly beneficial and cost-effective public health strategy.3,5

VACCINATIONS RECOMMENDED FOR ADULTS

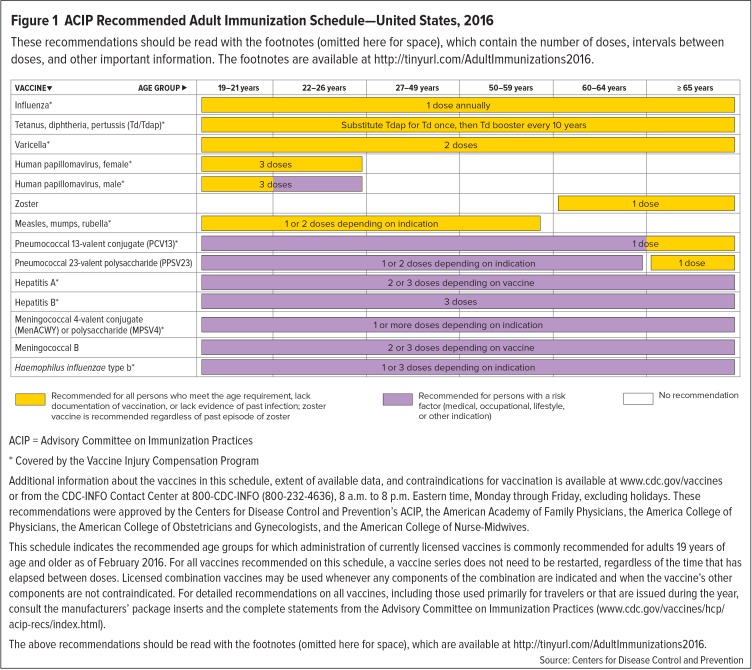

The availability of vaccines that are new or have new indications; evolving ecology and epidemiology of infectious diseases; demographic changes (such as an aging population); and other factors require that recommendations for the immunization of adults and the elderly be constantly updated and improved.5 To that end, the “Recommended Adult Immunization Schedule: United States, 2016” was published by the ACIP in January 2016.5,7,8 This schedule was reviewed and approved by the American College of Physicians (ACP), American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and American College of Nurse-Midwives.7 The full ACIP immunization schedule includes routine vaccination recommendations (with detailed explanations provided in footnotes), as well as indications, contraindications, precautions, and high-risk conditions for which specific vaccines are recommended.7,8

Vaccination recommendations for adults are generally based on factors such as age, immunization history, health status, lifestyle, occupation, and whether an individual is planning to travel or is immunocompromised.5,7,8 Figure 1 presents a summary of the standard vaccinations recommended by the ACIP.7,8 The full recommendations can be accessed at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/adult.html or http://tinyurl.com/AdultImmunizations2016.7,8 It should be noted that the footnotes and other information that accompany this schedule must be read to review the adult vaccine recommendations in their entirety.7,8

Figure 1.

ACIP Recommended Adult Immunization Schedule—United States, 2016

These recommendations should be read with the footnotes (omitted here for space), which contain the number of doses, intervals between doses, and other important information. The footnotes are available at http://tinyurl.com/AdultImmunizations2016.

ACIP = Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

* Covered by the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program

Additional information about the vaccines in this schedule, extent of available data, and contraindications for vaccination is available at www.cdc.gov/vaccines or from the CDC-INFO Contact Center at 800-CDC-INFO (800-232-4636), 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. Eastern time, Monday through Friday, excluding holidays. These recommendations were approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s ACIP, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the America College of Physicians, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the American College of Nurse-Midwives.

This schedule indicates the recommended age groups for which administration of currently licensed vaccines is commonly recommended for adults 19 years of age and older as of February 2016. For all vaccines recommended on this schedule, a vaccine series does not need to be restarted, regardless of the time that has elapsed between doses. Licensed combination vaccines may be used whenever any components of the combination are indicated and when the vaccine’s other components are not contraindicated. For detailed recommendations on all vaccines, including those used primarily for travelers or that are issued during the year, consult the manufacturers’ package inserts and the complete statements from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/index.html).

The above recommendations should be read with the footnotes (omitted here for space), which are available at http://tinyurl.com/AdultImmunizations2016.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The ACIP recommendations regarding immunizations for adults vary according to age (18–65 years and older than 65 years), and currently include vaccines against influenza (IIV or LAIV); tetanus-diphtheria (Td); tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap); varicella (VAR); human papillomavirus (HPV, 2vHPV, 4vHPV, or 9vHPV); herpes zoster; measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR); and S. pneumoniae (pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate [PCV13] or pneumococcal 23-valent polysaccharide [PPSV23]).7,8 Vaccines against hepatitis A (HepA), hepatitis B (HepB), meningococcus, and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) are recommended for persons with specific indications, such as a medical, occupational, and/or lifestyle risk factors.7,8 Additional details regarding many of these vaccines follow.

Herpes Zoster

Herpes zoster, also known as shingles, is a painful vesicular rash that is extremely common in the elderly.5 It is caused by the reactivation of the varicella zoster virus when T-cell–mediated immunity falls below a critical level.5 The incidence of herpes zoster infection is rising, partially due to increasingly prolonged life expectancy.5 In Western countries, its incidence is 10.9 per 1,000 people over the age of 80 years, compared to 1.1 to 2.9 per 1,000 people younger then 50 years of age.5 Approximately half of all shingles cases occur in individuals 60 years of age and older.5

A live attenuated vaccine against herpes zoster is available in the U.S. and the European Union for administration to adults 50 years of age and older.5 This vaccine significantly reduces the burden of herpes zoster, although it declines in efficacy with advanced age.5 Illustratively, after administration of the vaccine, the incidence of herpes zoster in older people has been found to be reduced by 69.8% in those between the ages of 50 and 59 years; by 63.9% in those 60 to 69 years old; and by 37.6% in people 70 years of age and older.5

Although the vaccine is licensed for use in patients 50 years of age and older, ACIP recommends that a single dose of herpes zoster vaccine be administered to adults 60 years of age or older, regardless of whether they have reported a prior episode of herpes zoster.7,8 People 60 years of age or older with chronic medical conditions may receive this vaccination unless their condition constitutes a contraindication, such as severe immunodeficiency.7,8

Human Papillomavirus

According to the ACIP, women and men up to the ages of 26 and 21 years, respectively, who have not received the vaccination during childhood as is recommended, should receive three catch-up doses of HPV vaccine.5,7,8 The second dose should be administered four to eight weeks after the first (minimum interval of four weeks), and the third dose should be administered 24 weeks after the first, and 16 weeks after the second (minimum interval of 12 weeks).5,7,8

Three HPV vaccines are licensed for use in women (bivalent HPV vaccine [2vHPV], quadrivalent HPV vaccine [4vHPV], and nine-valent HPV vaccine [9vHPV]). Two are licensed for use in men (4vHPV and 9vHPV).7,8 For women, 2vHPV, 4vHPV, or 9vHPV is recommended in a three-dose series for routine vaccination of adults 19 through 26 years old, if not previously vaccinated.7,8 For male patients, 4vHPV or 9vHPV is recommended in a three-dose series for routine vaccination of adults 19 through 21 years of age, if not previously vaccinated.7,8 HPV vaccination is also recommended for men who have sex with men and immunocompromised individuals (including those with human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]) up to the age of 26 years who did not receive any or all doses when they were younger.7,8

Influenza

In the United States, annual seasonal influenza vaccinations are recommended for all adults, as well as children 6 months of age and older.5,7,8 It is particularly important for elderly people to receive an influenza vaccine because this disease is a major cause of vaccine-preventable morbidity and mortality in this age group.5

An age-appropriate influenza vaccine formulation should be administered.7,8 For example, individuals older than 6 months of age (including pregnant women) can receive the inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV).7,8 Intradermal IIV is an option for people ages 18 to 64 years, while high-dose IIV is an option for patients 65 years of age and older.7,8 In its 2016 guidelines, the ACIP recommended live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) for healthy, nonpregnant, nonimmunocompromised patients ages 2 to 49 years. However, during June 2016, the committee voted to rescind that recommendation, based on data showing very poor or lower efficacy for this formulation during the 2013–2016 flu seasons. At present, this decision is awaiting approval by the CDC.7,8,15

It should be noted that the ability of the influenza vaccines to induce an effective and robust immune response decreases with advancing age and is generally lower in the elderly than in younger adults.5 One recent meta-analysis found that the efficacy of the influenza vaccine in the elderly was 17% to 53% (depending on the influenza strain), compared with 70% to 90% in young adults.5 Still, a number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that influenza vaccination reduces the overall mortality of noninstitutionalized elderly people by 39% to 75% during influenza seasons.5 However, the true efficacy of this vaccine in the elderly is unclear because of variation in factors such as the virulence of the circulating strain, the prevalence of the virus, and the efficacy of the vaccine against the circulating strain.5

Strategies to optimize the efficacy of the influenza vaccine in the elderly include the development of new and more effective vaccines and the vaccination of people in close contact with these patients, such as family members and health care professionals (HCPs), particularly those who work in long-term-care facilities.5

Measles, Mumps, and Rubella

According to ACIP adult vaccination recommendations, people born before 1957 are generally considered to be immune to measles and mumps.7,8 However, all adults born in 1957 or later should have documentation of one or more doses of the MMR vaccine unless they have a medical contraindication to the vaccine or laboratory evidence of immunity to each of these three diseases.7,8 Documentation of provider-diagnosed disease is not considered acceptable evidence of immunity against measles, mumps, or rubella.7,8

For vaccination against measles or mumps, a routine second dose of MMR vaccine, administered a minimum of 28 days after the first dose, is recommended for adults who are students in postsecondary educational institutions, work in a health care facility, or plan to travel internationally.7,8 Patients who received inactivated measles vaccine or measles vaccine of an unknown type during 1963 to 1967 should be revaccinated with two doses of MMR vaccine.7,8 Those who were vaccinated before 1979 with either inactivated mumps vaccine or mumps vaccine of an unknown type who are at high risk for mumps infection (e.g., people who are working in a health care facility) should be considered for revaccination with two doses of MMR vaccine.7,8

Rubella immunity should be determined for women of childbearing age, regardless of the year of birth.7,8 Women without any evidence of immunity should be vaccinated; however, if pregnant, they should receive an MMR vaccine upon completion or termination of the pregnancy before being discharged from the health care facility.7,8

Tetanus-Diphtheria and Tetanus-Diphtheria-Acellular Pertussis

The Td vaccine is recommended for all adults, with boosters given every 10 years to those who have been previously vaccinated.5 The ACIP recommendations state that people 11 years of age or older who have not received the Tdap vaccine (or for whom vaccine status is unknown) should receive one dose of Tdap followed by a Td booster every 10 years.7,8 Tdap can be administered regardless of the interval since the last tetanus or diphtheria-toxoid-containing vaccine.7,8

For unvaccinated adults, a three-dose primary vaccination series with Td-containing vaccines should be completed and should include one Tdap dose.7,8 The first two doses should be administered at least four weeks apart and the third dose given six to 12 months after the second.7,8 For adults who have received fewer than three doses, the remaining doses should be administered.7,8 For pregnant women, a dose of Tdap should be administered during each pregnancy (preferably between 27 and 36 weeks’ gestation), regardless of the interval since the last Td or Tdap vaccination.7,8 The ACIP schedule should be consulted for recommendations for administering Td/Tdap prophylactically for wound management.7,8

Because pertussis has re-emerged in developed countries, as of 2013, the ACIP began recommending the re-administration of Tdap to adults (including HCPs) who expect to be around infants due to the morbidity associated with pertussis in this age group.1,5 However, studies have shown that Tdap immunization of pregnant women against pertussis may be a more effective strategy.1,14 One study found that maternal Tdap vaccination reduced the incidence of pertussis in infants by 33%, compared with 20% achieved with postpartum vaccination alone. The rate of hospitalization was also reduced by 38% compared to 19%, respectively.14 Furthermore, maternal vaccination with Tdap reduced the risk of infant death by 49% compared with 16%, respectively.14 Therefore, starting in 2011, the ACIP began recommending that unvaccinated pregnant women receive Tdap in the late second or third trimester of pregnancy.14 The following year, the ACIP extended this recommendation for all pregnant women to receive Tdap during every pregnancy.14 The ACIP also continues to recommend the vaccination of adults who expect to be around infants (i.e., “cocooning”), with the recognition that this recommendation may be difficult to implement.14

Pneumonia

The pneumococcal vaccine is primarily recommended for the elderly, specifically those 65 years of age and older; however, there is debate as to whether PPSV23 or PCV13 should be administered to these patients.5 Elderly adults are recommended to receive one dose of PCV13 and one, two, or three doses of PPSV23.7,8 Additional doses of PPSV23 are not required for adults vaccinated with PPSV23 at 65 years of age or older.7,8 When indicated, both PCV13 and PPSV23 should be administered to adults whose pneumococcal vaccination history is unknown or incomplete.7,8 If both PCV13 and PPSV23 are indicated, PCV13 should be administered first; however, both vaccines should not be administered during the same visit.7,8 Instead, a single dose of PCV13 should be given, followed by a dose of PPSV23 at least eight weeks later.5

PCV13 is recommended for people 19 years of age or older who have not previously received PCV13 or PPSV23 and are immunocompromised or have functional or anatomic asplenia, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, or cochlear implants.5 Adults 19 years of age or older with these conditions who have previously received one or more doses of PPSV23 should receive a dose of PCV13 one or more years following the last PPSV23 dose.5 Other high-risk patients (including those with chronic heart or lung disease, diabetes mellitus, or chronic liver disease, as well as those exposed to alcoholism or cigarette smoking) should receive PPSV23, with the first dose given at least eight weeks after PCV13 and at least five years after the most recent dose of PPSV23.5

A meta-analysis of 22 studies in adults found that the risk of invasive pneumococcal disease (and to a lesser extent all-cause pneumonia) is reduced by pneumococcal vaccination.5 However, another study that evaluated the efficacy of PPSV23 in preventing pneumonia and acute re-exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease did not find a statistically significant difference between patients receiving the pneumococcal vaccination and control groups.5

Study results are similarly contradictory in elderly patients. One study reported that the efficacy of PPSV23 in preventing pneumonia in healthy elderly adults was not significant.5 However, a randomized, placebo-controlled study demonstrated a 63.8% reduction in pneumococcal pneumonia in institutionalized elderly patients.5 A reduction in the incidence of all cases of bacteremic and nonbacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia in adults over the age of 50 years was also demonstrated in a three-year cohort study.5

Varicella

Because of the high risk of varicella (i.e., chickenpox) complications in adults, the ACIP recommends a two-dose varicella vaccination in healthy adults without a clinical history of varicella or evidence of varicella immunity.5,7,8 This recommendation should especially be heeded by people who are at high risk for exposure to or transmission of the disease, such as HCPs, household contacts of immunocompromised subjects, nonpregnant women of childbearing age, people frequently exposed to children, and international travelers.5,7,8

The ACIP considers adequate evidence of varicella immunity in adults to be demonstrated by any of the following:5,7,8

Documentation of two doses of varicella vaccine at least four weeks apart;

Americans born before 1980, except HCPs and pregnant women;

History of varicella based on diagnosis or verification by an HCP;

History of herpes zoster based on diagnosis or verification by an HCP; or

Laboratory confirmation of disease or evidence of immunity.

Adults without evidence of varicella immunity should receive two doses of single-antigen varicella vaccine or a second dose if they have received only one dose.7,8 For patients receiving two doses, the second dose should be administered four to eight weeks after the first dose.7,8 Pregnant women should be assessed for evidence of varicella immunity; for those without evidence of immunity, the first dose of varicella vaccine should be received upon completion or termination of pregnancy prior to discharge from the health care facility.7,8

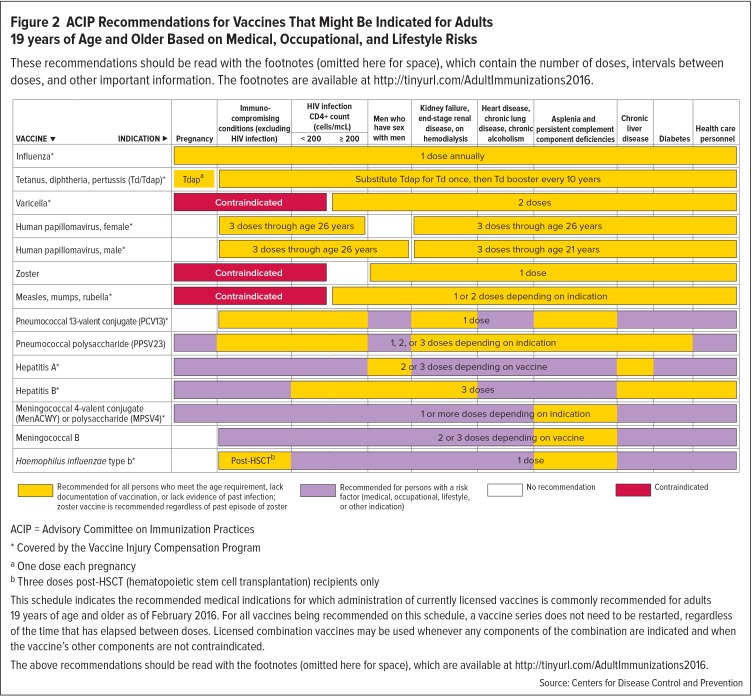

VACCINES RECOMMENDED FOR HCPS

Because of frequent contact with patients and exposure to viruses and bacteria, HCPs are at high risk for developing vaccine-preventable diseases and may also be a source of infection for susceptible patients or colleagues.5,14 Outbreaks of serious and sometimes fatal cases of pertussis, influenza, rubella, chickenpox, hepatitis A and B, mumps, measles, drug-resistant tuberculosis, and invasive meningococcal disease have been documented among HCPs.5 Lost working days can also negatively effect the ability of an HCP to provide health care services.5

Adherence to the ACIP vaccination recommendations for HCPs is therefore a major infection prevention and control measure.5 Vaccination of HCPs benefits patients, colleagues, and other community members through decreasing illness, hospitalization, and even death.14 The 2016 ACIP vaccination recommendations for HCPs (Figure 2) are similar to those for other adults and are discussed in additional detail in footnotes.7,8 However, in addition to standard vaccinations, the ACIP also recommends that HCPs be vaccinated against hepatitis B.7,8

Figure 2.

ACIP Recommendations for Vaccines That Might Be Indicated for Adults 19 years of Age and Older Based on Medical, Occupational, and Lifestyle Risks

These recommendations should be read with the footnotes (omitted here for space), which contain the number of doses, intervals between doses, and other important information. The footnotes are available at http://tinyurl.com/AdultImmunizations2016.

ACIP = Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

* Covered by the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program

aOne dose each pregnancy

bThree doses post-HSCT (hematopoietic stem cell transplantation) recipients only

This schedule indicates the recommended medical indications for which administration of currently licensed vaccines is commonly recommended for adults 19 years of age and older as of February 2016. For all vaccines being recommended on this schedule, a vaccine series does not need to be restarted, regardless of the time that has elapsed between doses. Licensed combination vaccines may be used whenever any components of the combination are indicated and when the vaccine’s other components are not contraindicated.

The above recommendations should be read with the footnotes (omitted here for space), which are available at http://tinyurl.com/AdultImmunizations2016.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

There are few published data concerning vaccination coverage for HCPs; however, there is evidence that these rates are low.5 For example, the ACIP has recommended annual influenza vaccination for HCPs since the early 1980s.14 Despite this longstanding recommendation, immunization rates for HCPs never exceeded 50% prior to the 2009–2010 influenza season.14 These low coverage rates prompted the ACIP to recommend mandatory influenza vaccination for all HCPs since 2010.14 Despite these efforts to improve influenza immunization rates among HCPs since 2010, influenza coverage within health care organizations has ranged from 65% to 75%.5,14 This coverage rate is still well below the 90% target.9 Further increases in HCP vaccination are vital because vaccination coverage rates exceeding 80% are essential to provide the “herd immunity” needed to significantly influence the transmission of influenza by HCPs in medical settings.14

VACCINES RECOMMENDED FOR TRAVELERS

It is generally agreed that there is a need to prevent the spread of travel-related infections.5 Therefore, a consultation with an infectious disease specialist or other means of identifying recommended travel-related vaccinations is important to help reduce and manage health risks.5 Potential risks need to be evaluated by considering information regarding the countries to be visited, including whether time will be spent in urban or rural areas, possible activities, and other variables.5 Factors regarding the traveler also need to be considered, including age, gender, vaccination and medical history, and immune status.5 HCPs should also refer travelers to the current immunization schedules to make sure they are up to date with standard vaccinations.5

With regard to the immunization of travelers, there are three types of vaccinations: “required”, “recommended,” or “routine.” 5 Required immunizations are those that are needed to enter a particular country, for which an international proof of vaccination certificate is mandatory.5 Recommended vaccines are medically advisable based on the risk for contracting a contagious disease during a journey.5 Lastly, routine vaccinations are those that protect against diseases that are known to cause outbreaks in both developed and developing countries.5 The CDC publishes vaccine recommendations for travelers according to the country to be visited, which can be accessed at wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/destinations/list.16

The most frequent vaccine-preventable disease that affects international travelers is hepatitis A, which is endemic throughout developing areas of Asia, Africa, and Central and South America because of poor sanitary conditions; however, HepA vaccine should be considered for travelers to any destination.5 The incidence of HepA among unvaccinated travelers to these areas is estimated to be three to 20 cases per 1,000 travelers per month.5 A number of travel-related cases and outbreaks of HepA reported in Europe and the U.S. have usually involved infections “imported” by asymptomatic children who were visiting from abroad.5

Immunization against typhoid fever is another common vaccine for travelers.5 The risk of typhoid fever is highest for travelers to Southern Asia, but it is also endemic in other areas of Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, and Central and South America.5 Typhoid vaccine is recommended for all travelers to these areas and should be administered two weeks or more before potential exposure.5 Two vaccines are available: an oral live attenuated vaccine for immunocompetent patients, which requires a booster every five years, and an intramuscular capsular polysaccharide vaccine for immunocompromised patients, which requires a booster every two years.5

Meningococcal disease also poses a risk to travelers; however, it occurs at an appreciably lower incidence than most other vaccine-preventable contagious diseases.5 Travelers to Africa (particularly to the “meningitis belt,” which stretches from Senegal to Ethiopia) and the Middle East are especially at risk.5 Quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (which is composed of groups A, C, Y, and W135 conjugated to diphtheria toxoid) is recommended for travelers to these regions.5 The recently approved MenB vaccine is not recommended for travelers because meningococcal disease in the high-risk areas of Africa and the Middle East is generally not caused by serotype B.14

Vaccination against yellow fever is also recommended for travelers to sub-Saharan Africa and tropical South America.5 The risk of contracting yellow fever depends on immunization status, trip itinerary and activities, the season (risk peaks during the rainy season), and the current local rate of virus transmission.5 The only immunization available against yellow fever is a live attenuated vaccine that has many contraindications, including allergy to any of its components, symptomatic primary immunodeficiencies or thymus disorders, or malignant neoplasms.5 A risk–benefit evaluation should be conducted prior to administering the yellow fever vaccine to individuals 60 years of age and older, patients with asymptomatic HIV infection and CD4+ T lymphocyte levels of 200–499/mcL, and pregnant or breastfeeding women.5 Additional immunizations that should be considered for travelers include those against polio, tick-born encephalitis, Japanese encephalitis, cholera, and rabies.5 However, these vaccines are related to specific travel-related risks and, therefore, are not frequently administered.5

Unless required, adherence to vaccine recommendations by travelers is low.5 For example, despite current recommendations, HepA vaccine coverage among adults traveling to endemic areas has been reported to be as low as 27%.5

VACCINE COVERAGE IN ADULTS

In Western countries, morbidity and mortality due to communicable infectious diseases have significantly decreased, largely because of well-planned national immunization schedules and vaccination strategies, particularly for children.5 However, American adults are inadequately vaccinated, particularly against pneumococcal disease, influenza, hepatitis B, tetanus, and diphtheria/pertussis.9 Consequently, tens of millions of Americans remain susceptible to potentially deadly infections that could be prevented by effective vaccines.9

In the U.S., the elderly are particularly susceptible to death from pneumonia and influenza.4 Pneumococcal and influenza vaccines are estimated to prevent thousands of deaths each year; however, vaccination rates for these diseases among adults 65 years of age and older were only 59.7% in 2013 17 and 66.7% in 2014–2015 18, respectively. In the U.S., coverage for the herpes zoster vaccine among adults 60 years of age and older has been even lower than that of the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines with just 24.2% of that age group receiving the vaccine in 2013.17

Despite ACIP recommendations, vaccination coverage rates among high-risk adults 65 years of age or older have also remained low.5,7 The overall influenza vaccine coverage for the 2012–2013 season among adults aged 18–64 years with one or two high-risk conditions was only 49.5% and 59.5%, respectively.7 Influenza vaccination rates were low among high-risk patients with heart disease (50.5%), lung disease (46.2%), renal disease (62.5%), diabetes (58.0%), and cancer (56.4%).7 Among adults 19 years of age and older with chronic liver conditions, only 13.3% reported that they received the vaccine for HepA and 34.0% for HepB.7 HepB vaccination coverage among adults ages 19 to 59 years and 60 years and older with diabetes was only 26.3% and 13.9%, respectively.7 Importantly, it has been estimated that in 2012–2013, 90% of high-risk unvaccinated adults may have missed at least one opportunity to receive the influenza vaccine from their HCPs.7

CONSEQUENCES OF VACCINE NONCOMPLIANCE

An estimated average of 50,000 Americans die of vaccine-preventable diseases each year, with more than 99% of these deaths occurring in adults.3,5 This means that each year, roughly one out of every 7,000 Americans will die of a disease that might have been prevented by available vaccines.3 In 2008, an estimated 44,000 cases of invasive pneumococcal disease were reported, which caused about 4,500 deaths, mostly involving people over the age of 35 years.12 In 2009, HPV infections were responsible for the majority of cervical cancers, even though they can be prevented by a vaccine.5

Rapid population aging is a major challenge in developed countries such as the U.S., Canada, and most of Europe.5 The incidences of infections and their severity, complications, hospitalization, and mortality rates all increase with age.5 The elderly are therefore classified as one of the highest risk groups for infectious diseases, mainly because of their reduced immune response and the high prevalence of other risk factors.5 Although most vaccines are less effective in the elderly, immunization is still an efficient means of preventing infectious diseases in this group.5 However, influenza and pneumonia, considered together, are the fifth leading cause of death for Americans 65 years of age and older, partially due to vaccine noncompliance.4,9 Mortality from pneumonia in this age group varies from 15% to 40%, depending on risk factors.4 Therefore, it is surprising that vaccination rates with PPV23 continue to be less then 60% for people older than 65 years.4

BARRIERS TO ADULT IMMUNIZATION

To facilitate compliance with vaccine recommendations, barriers to adult immunization have been identified by the U.S. Public Health Service, multiple national professional health care organizations, and state public health agencies.4 Several factors conspire to prevent routine immunization, including cost, lack of knowledge and awareness, missed opportunities, and operational or systemic barriers.3 Identifying the reasons underlying the tendency of adults to forego immunization is a critical step in improving vaccination policies and strategies and in increasing adult immunization coverage.5 A discussion of the barriers to adult immunization follows.

Low Priority

The American health care system lacks an effective adult vaccine delivery system. Vaccination remains a low priority for both physicians and patients.10 Unlike schools, employers rarely require proof of vaccination as a condition of employment, so this motivator disappears in young adulthood.10 When HCPs were asked why patients might not receive recommended immunizations, among the reasons that were consistently mentioned was the belief that a healthy person did not need to be vaccinated and failure to come in for regular well-care visits.4

Lack of Information

Lack of information is a serious contributor to adult immunization noncompliance, particularly for patients.10 Many adults are not aware that they need vaccinations and don’t ask for them when they seek health care.10 Patients often aren’t aware of the benefits of immunization, or don’t understand why a booster dose might be needed.10 Without a structured reminder system, patients may also forget to schedule a needed vaccination.10 Some patients mistakenly believe that disease prevention through vaccination is no longer a concern when they are adults.10

A survey of more than 2,000 adults 19 to 74 years old (including 20 HCPs) asked about attitudes and knowledge regarding the tetanus, influenza, and pneumonia vaccines.4 Among those surveyed, 90% to 96% were aware that influenza and tetanus vaccines are available.4 However, only 36% knew that adults should receive a tetanus booster every 10 years.4 Instead, 74% believed that a tetanus shot was necessary only when an injury occurred.4 Furthermore, although 65% were aware of the pneumococcal vaccine, 56% had not gotten it because “their doctor had not recommended it.”4

Informational barriers regarding vaccines also impede HCPs. These include: knowledge gaps concerning vaccine indications and contraindications; poorly trained medical staff; missed opportunities for vaccine administration; limited patient screening for immunization status; and insufficient time spent communicating the benefits and risks of vaccines to patients.4,5 Many HCPs are unaware of the ACIP adult immunization recommendations and the variations due to age and comorbidities.10 In one survey, only 60% of physicians and 56% of physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and registered nurses stated that they used official guidelines as their source of information about adult immunizations.4

Fear or Opposition Concerning Vaccines

Myths about vaccines are plentiful, causing some patients to be fearful about vaccines or needles.10 A dislike of needles or fear that a vaccine may cause side effects are common reasons why adults avoid immunization.4,5 In addition, despite the success of immunization as a public health intervention, some people are opposed to vaccines, arguing that they are dangerous or don’t work; that personal hygiene is a more reliable means of preventing infection; or that mandatory vaccinations violate religious principles or individual rights.5

Lack of Accessibility

Vaccination costs can be a significant barrier for adults who want to be immunized.10 Low-income families who are uninsured may not be aware of free public vaccination programs when and where available.5 Other obstacles impeding vaccine compliance may include transportation problems, language barriers, or incomplete records.5 Some patients may also have cognitive issues that prevent them from understanding vaccine recommendations or understanding why immunization is needed.10

Systemic and Operational Obstacles

Systemic and operational barriers faced by patients and HCPs that impede vaccine compliance include: the direct and indirect costs of immunization, vaccine storage difficulties, and lack of current, easily accessed immunization records.4,5,10 Stringent storage requirements (such as that required by the MMR, live attenuated influenza, and rotavirus vaccines) and vaccine shortages also hamper immunization efforts.4,5,10 It has been estimated that only 31% of family physicians and 20% of internists stock all of the vaccines routinely recommended for adults.7 Waste is also a serious concern; each year, health care facilities return or destroy doses of influenza vaccine, with 29 million vials discarded in 2008 alone.10

Immunization records are also often incomplete for adults. Immunizers must frequently search for or cannot find documents regarding a patient’s immunization status, or must rely on potentially inaccurate patient self-reporting.10 Lack of accurate vaccination records may also cause HCPs to miss opportunities to educate and vaccinate patients.10 Various surveys have also documented a lack of computerized vaccine registries, which presents significant potential risk for incomplete immunization or overimmunization.5

MEASURES TO OVERCOME NONCOMPLIANCE

HCP-Based Interventions

Clearly, passively offering immunizations to adult patients has led to suboptimal results with respect to vaccine compliance.5 Although important advances in immunization have been made, serious issues still exist, such as the re-emergence of pertussis, measles outbreaks, and the vulnerability of the elderly to influenza and pneumococcal diseases.5 Immunization is an important component of medical care, therefore, it is the duty of HCPs, including retail and health system pharmacists, to be knowledgeable about and supportive of vaccination goals.3,7,9 Proven strategies exist that can improve immunization coverage rates and reduce vaccine-preventable diseases among adults in the United States.7 A discussion of some HCP-based measures to increase adult vaccine compliance follows.

Provide Counseling

HCPs are clearly influential figures in promoting vaccination among adults.2,5,7 A recommendation from an HCP for a vaccination has been observed to be a strong predictor of patient compliance.5,7 Conversely, the failure of HCPs to discuss vaccination with patients is a common reason for vaccine noncompliance.4 In one survey, most consumers (79% to 85%, depending on the vaccine) indicated they were likely to receive a vaccine if their health care professional recommended it.4 However, more than 50% of health care professionals admitted that they did not always discuss the consequences of missed vaccinations with patients.4

Health care providers can influence patients’ acceptance and motivation regarding immunization.2,9 It is essential that all HCPs develop counseling approaches that individualize the message concerning vaccines for each patient.2,5 Patients should be encouraged to accept the immunizations they need and be advised of infection risks.2,9 Any concerns about vaccine efficacy and safety should be discussed, and any misconceptions should be respectfully corrected using facts to address myths.2,9,5

Several tools are available that can assist HCPs in screening patients and recommending needed vaccines.7 Many providers will need to refer patients to other HCPs for vaccinations.7 The Vaccine Finder, available at www.vaccines.gov/more_info/features/healthmapvaccinefinder.html, can be used to identify locations for specific vaccinations in a particular area.7,19 CDC-developed Vaccine Information Statements (VIS) are also available in many languages from the CDC at http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis or from state or local health departments.9 In addition, free apps concerning immunization recommendations and scheduling are available through the iTunes Store or Google Play.3

Maximize Opportunities for Vaccinations

Every possible catch-up opportunity should be used to recommend vaccinations that will protect adults, particularly the elderly.5,9 Although vaccine coverage in adults is low, most family physicians and internists feel responsible for ensuring that patients receive recommended vaccines.4,7 However, only 32% of family physicians and 29% of internists assess their adult patients’ vaccination status at every visit.7

HCPs need to be aware of the importance of routinely assessing patients’ vaccination histories and recommending and/or administering necessary vaccines.5,9 Anywhere medical care is rendered, procedures for screening patients should be in place.3,9 Policies (such as standing orders) should be established to administer needed vaccines or to refer patients to another facility.3,9 If standing orders or collaborative practice agreements are not in place, physicians should be informed of their patients’ need for vaccination.9 If possible, patients who need immunizations should be vaccinated during the current health care visit because delaying vaccination until the next appointment increases the risk of patient noncompliance.9

Improve Vaccination Accessibility

Vaccine accessibility can be improved by offering alternative venues for immunization, allowing walk-in visits, and providing availability during extended hours.2,9 Such services and programs have been shown to provide high-quality care, reach new patients, and contain costs.12,13 The utility of this approach is evidenced by the success of retail pharmacy-based immunization programs.11–13 Influenza vaccines are the most commonly administered vaccine in pharmacies, but other vaccines are also available in such locations.13 In recent years, nearly half of all flu vaccines received by adults were administered in nonmedical settings, such as drugstores, contributing to the nearly doubling of those administered in the U.S. to 134.5 million from 2000 to 2014.11,13

A recent study demonstrated the benefit of the expanded hours provided by pharmacy-based immunization programs in increasing adult vaccination.12 Of 6,250,402 immunizations administered at a national pharmacy chain during one year, 1,906,352 (30.5%) were given during evenings, weekends, or federal holidays—times when traditional venues for vaccination are not accessible.12 Another study showed that patients with risk factors for pneumococcal pneumonia who had access to vaccinations against this disease at a large pharmacy chain were immunized at a significantly higher rate than would normally be expected (4.88% versus 2.90%).12

It is unclear whether these improvements in vaccination rates can be attributed entirely to retail pharmacy-based immunization programs; however, many studies have shown that easy access and convenience are a big factor for adults getting immunizations.11 Retail pharmacy vaccination programs don’t require an appointment, offer many locations, and are accessible during off hours and weekends.11,13 Customers can even spontaneously decide to get an immunization during a shopping trip.11 Some doctor’s offices have also begun offering same-day appointments for flu shots.11

Maintain Electronic Medical Records (EMRs)

Adult vaccine noncompliance can be reduced by implementing electronic recordkeeping systems for recording vaccine administrations.5 EMR systems should include adult immunization records and clinical decision support systems that will prompt providers to determine their patients’ immunization needs and recommend appropriate vaccinations.7,9 One successful strategy for reducing vaccine noncompliance involved the use of EMR reminders identifying vaccination opportunities that were directed at primary care and emergency department physicians.5 EMRs also enable the long-term storage of medical records and provide an efficient method for the maintenance and retrieval of immunization records.9

Use Patient Notifications

Notifying patients of their need for immunization can take several forms.9 In ambulatory care settings, successful strategies to increase adult vaccine compliance have included patient recall/reminder letters or text messages.5,7,9 Patients can also be contacted about needed vaccinations by form or individualized letter mailings, by telephone, or with inserts included with prescriptions.9 Adhesive reminder labels with messages such as, “You may need a flu or pneumonia vaccine, ask your pharmacist or doctor,” can also be affixed to prescription containers.9 For inpatients or institutionalized patients, one-on-one conversations can also be an effective means of notifying patients about needed vaccines.9

Comply with HCP Vaccination Requirements

Health care personnel have a responsibility to be up to date with personal vaccinations in order to promote their own health and protect patients and colleagues.2 However, mandatory influenza vaccination of HCPs appears to be the only means of increasing the percentage of vaccinated HCPs in most patient care settings.14 Mandatory influenza vaccination policies are therefore becoming increasingly common in the U.S., with many institutions already reporting successful implementation.14 In the 2012–2013 influenza season, 30% of HCPs reported such a requirement at their institution.14 When mandatory, flu vaccine coverage rates for HCPs were above 95% for all occupational settings, including hospitals, ambulatory care offices, and long-term-care facilities, compared with 65% to 75% when immunization was not required.14

Government and Community-Based Programs

Most of the problems leading to low vaccination coverage are due to information and knowledge gaps on the part of patients and HCPs.5 In addition, age-related diseases and disorders are also well-known risk factors for the occurrence of some vaccine-preventable diseases, such as influenza and invasive pneumococcal disease.5 Therefore, public education efforts should be targeted at these and other noncompliant groups and include age-based adult immunization schedules, as well as information to dispel vaccine myths.5

Nonprofit organizations can also play an important role in introducing and sustaining new vaccination programs.5 These organizations can support public policy by communicating the benefits of vaccination through social media and public service announcements, as well as at public events.5 These organizations provide an important link between the scientific community and the lay public, providing a counterbalance to media hype and claims made by antivaccination groups.5

Pharmacists can also act as advocates for public health by participating in community-based immunization efforts.2,9 Pharmacists can facilitate disease prevention strategies or lead local activities in their communities during National Adult Immunization Week.9 They can work with local health departments, state or national immunization coalitions, or other associations to promote vaccination among high-risk populations.2,9 Pharmacists can distribute posters, news letters, or brochures, and sponsor seminars to explain the risk of vaccine-preventable infections to patients, pharmacy staff, and other HCPs.2,9 Resources for these efforts include the Immunization Action Coalition and the National Coalition for Adult Immunization.9

Adult vaccination noncompliance can be further reduced by implementing public health immunization programs in medical homes, integrated health care sites, and in nontraditional places, such as the workplace.5 Based on the success of pharmacy-based immunization programs, the CDC recommends “expanding access through nontraditional settings, e.g., pharmacy, workplace, and school venues for vaccination to reach individuals who may not visit a traditional provider during the flu season.”12

Health System Pharmacist-Based Interventions

The need to improve adult vaccination coverage should inspire health system pharmacists to assess what they and their institutions can do to improve immunization rates.9 Efforts to promote immunization by these HCPs can be categorized into six types of activities: patient counseling, history and screening, administrative measures, documentation, formulary management, and public education.9 Such activities can be integrated into or undertaken in parallel to a pharmacy-based immunization program.9

The “ASHP [American Society of Health-System Pharmacists] Guidelines on the Pharmacist’s Role in Immunization” discuss the place of health system pharmacists in promoting and conducting proper patient immunizations.9 A summary of these guidelines follows.

Vaccine Administration Programs

An effective vaccine administration program requires a solid infrastructure of appropriately trained staff, adequate physical space, written policies and procedures addressing vaccine storage and handling, patient screening and education, and accurate documentation.9 A vaccine administration program must also address the storage and disposal of injection supplies, as well as the proper disposal of used needles.9 Health care organizations might also consider developing policies and protocols that address other topics, such as those listed in Table 1. Excellent resources for setting up an immunization program are available from the ACP (www.acponline.org) and from the CDC (www.cdc.gov/vaccines).3

Table 1.

Suggested Vaccination Policies and Protocols For Use in Health Care Organizations9

|

It is also very important for pharmacists to be fully immunized to protect their own health, as well as that of their patients and colleagues.2,9 Pharmacists who participate in infection control and risk management committees in organized health care settings should therefore promote sound organizational policies regarding immunization delivery among staff.9

Standing Orders

Vaccine administration may occur pursuant to standing orders or protocols, or through individual prescriptions.9 The ACIP recommends the use of standing orders to improve adult immunization rates in long-term-care facilities, home health care agencies, hospitals, clinics, workplaces, and managed care organizations.9 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services also no longer requires a physician order for influenza or pneumococcal immunizations administered in participating hospitals, long-term-care facilities, or home health care agencies.9

Legal Authority

Health system pharmacists must understand the legal regulations and professional guidelines concerning vaccine administration.9 The pharmacist’s authority and the conditions under which he or she can administer vaccines are determined by each state’s laws and regulations governing pharmacy practice.9 Development of state-specific protocols or standing-order programs can be facilitated through partnerships with state boards of pharmacy, health departments, and pharmacy associations.9

Training

Pharmacists must be competent in all aspects of vaccine administration.9 A list of topics that might be included in vaccine administration training is presented in Table 2. Because information regarding vaccines changes rapidly, pharmacists must also have access to current immunization references (e.g., the CDC’s National Immunization Program publications, including Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases, also known as the “Pink Book”) and continuing education programs in order to stay abreast of evolving guidelines and recommendations.9

Table 2.

Essential Elements in a Comprehensive Vaccination Training Program for Health System Pharmacists9

|

History and Screening

All health care institutions should implement systematic monitoring systems to ensure that all patients are assessed for immunization adequacy before they leave the facility.2,9 HCPs designated to identify patient immunization needs should also have the knowledge, authority, and responsibility to arrange or provide immunization services.9 It is particularly important that clinics that treat a large number of patients who are at high risk for contracting vaccine-preventable diseases (e.g., patients with diabetes, asthma, or heart disease and elderly patients) employ patient immunization screening.9

In health care institutions, this can take some or all of the following forms:9

Occurrence screening. Vaccine needs are identified during particular events, such as nursing home or hospital admission or discharge, emergency room or ambulatory care visits, and any other contact with a health care delivery system, particularly for patients younger than 8 years of age or older than 50 years of age.9

Diagnosis screening. Vaccine needs of patients are reviewed when high-risk conditions are diagnosed.9

Procedure screening. Immunization needs are assessed in conjunction with medical or surgical procedures.9

Periodic mass screening. Immunization adequacy of selected populations is assessed at a given time.9

Occupational screening. Immunization needs of HCPs who are in contact with high-risk patients or otherwise exposed to vaccine-preventable diseases are addressed.9

Screening for contraindications and precautions. Candidates that have been identified as needing vaccination are screened for contraindications and precautions.9 A contraindication screening questionnaire can be obtained from the Immunization Action Coalition at www.immunize.org/catg.d/p4065.pdf.9,20

Reimbursement

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act requires that qualified private health insurance policies must provide full reimbursement for recommended vaccines with no out-of-pocket costs for patients.9 Medicare and Medicaid also pay for some vaccines, depending on the particular plan.9,10 Whenever necessary, health system pharmacists should advocate reimbursement for needed immunizations that are not covered by insurance as a cost-effective preventive measure.9 For patients without insurance coverage, out-of-pocket payments from the patient or referral to free vaccination programs are viable options.9

Formulary Management

When considering vaccine choices, P&T committees should review relevant immune pharmaceuticals, immunopharmacology, and disease epidemiology.9 Health system formularies should include vaccines, immunoglobulins, and toxoids that prevent infectious diseases.9 Pharmacists are an important resource for information and recommendations upon which to base formulary decisions.9

Health system pharmacists must also establish and maintain product specifications for drug purchases and standards to ensure the proper storage, use, and quality of all pharmaceuticals dispensed.9 A choice between single or multidose vaccine containers must be made on the basis of efficiency, safety, economic, and regulatory considerations.9 Health system pharmacists should also develop guidelines concerning the routine stocking of immunizations in certain high-use patient care areas.9

Proper transportation and storage are important for immunological drugs, including vaccines, because many require refrigeration or freezing.9 Storage protocols should include the conditions in all areas that immunological drugs are kept, as well as ensuring that immunological drugs received by the pharmacy were transported under suitable conditions.9 Methods should also be established to detect and properly dispose of outdated or partially administered immunological drugs.9 Live bacterial (e.g., bacillus Calmette–Guérin) and live viral (e.g., varicella, yellow fever) vaccines should be disposed of in the same manner as other infectious biohazardous waste.9

CONCLUSION

The efficacy of vaccines in preventing severe infectious disease is without question.4 However, despite this success, there is a need for improvement in adult vaccine compliance.4 Although various measures of improving vaccine coverage have been identified, achieving target levels will be possible only through the combined efforts of patients, HCPs (including retail and health system pharmacists), local communities, and governmental and nonprofit organizations.5 A more dynamic approach to the prevention of infectious diseases in adults and the elderly through vaccination may further improve public health.5

REFERENCES

- 1.Oldfield BJ, Stewart RW. Common misconceptions, advancements, and updates in pediatric vaccine administration. South Med J. 2016;109(1):38–41. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams DM, Weber DJ. Improving adult immunization across the continuum of care: making the most of opportunities in the ambulatory care setting. 50th American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Midyear Clinical Meeting and Exhibition; New Orleans, Louisiana. December 8, 2015; Available at: www.cemidday.com/handout-immunization.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poland GA, Schaffner W, Hopkins RH., Jr Immunization guidelines in the United States: new vaccines and new recommendations for children, adolescents, and adults. Vaccine. 2013;31(42):4689–4693. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson E. Recommended solutions to the barriers to immunization in children and adults. Mo Med. 2014;111(4):344–348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esposito S, Durando P, Bosis S, et al. Vaccine-preventable diseases: from paediatric to adult targets. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(3):203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temoka E. Becoming a vaccine champion: evidence-based interventions to address the challenges of vaccination. SD Med. 2013. Spec no: 68–72. [PubMed]

- 7.Kim DK, Bridges CB, Harriman KH. Advisory committee on immunization practices recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older: United States, 2016. Ann Int Med. 2016;64(3):184–194. doi: 10.7326/M15-3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Recommended adult immunization schedule, United States–2016. Available at: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/adult/adult-schedule.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists ASHP guidelines on the pharmacist’s role in immunization. Available at: www.ashp.org/doclibrary/bestpractices/specificgdlimmun.aspx. Accessed March 31, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Wick JY. Pharmacy Times. Roll up your sleeves: adult immunizations. Available at: www.pharmacytimes.com/publications/issue/2013/march2013/roll-up-your-sleeves-adult-immunizations. Accessed March 31, 2016.

- 11.Half of all flu shots in the U.S. are provided by pharmacists. Human Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(11):3103–3106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maine LL, Knapp KK, Scheckelhoff DJ. Pharmacists and technicians can enhance patient care even more once national policies, practices, and priorities are aligned. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(11):1956–1962. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dempsey AF, Zimet GD. Interventions to improve adolescent vaccination: what may work and what still needs to be tested. Vaccine. 2015;33:D106–D113. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kao CM, Schneyer RJ, Bocchini JA. Child and adolescent immunizations: selected review of recent U.S. recommendations and literature. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2014;26(3):383–395. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . ACIP votes down use of LAIV for 2016–2017 flu season. Available at: www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/s0622-laiv-flu.html. Accessed July 10, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Recommended adult immunization schedule, United States–2016. Travelers’ health: destinations. Available at: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/adult/adult-schedule.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2014–15 influenza season. Jun 23, 2016. Available at: www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1415estimates.htm. Accessed June 29, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams WW, Lu PJ, O’Halloran A, et al. Vaccination coverage among adults, excluding influenza vaccination—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(4):95–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vaccines.gov. Vaccine Finder. Available at: www.vaccines.gov/more_info/features/healthmapvaccinefinder.html. Accessed March 31, 2016.

- 20. Immunization Action Coalition. Screening checklist for contraindications to vaccinations in adults. Available at: www.immunize.org/catg.d/p4065.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2016.