Abstract

Objectives:

The Mental Health Experiences Scale is a measure of perceived stigma, the perception of negative attitudes and behaviours by people with mental disorders. A recent Canadian survey (Canadian Community Health Survey–Mental Health) included this scale, providing an opportunity to describe perceived stigma in relation to diagnosis for the first time in the Canadian general population.

Methods:

The survey interview began with an assessment of whether respondents had utilised services for an “emotional or mental health problem” in the preceding 12 months. The subset reporting service utilisation were asked whether others “held negative opinions” about them or “treated them unfairly” for reasons related to their mental health. The analysis reported here used frequencies, means, cross-tabulation, and logistic regression, all incorporating recommended replicate sampling weights and bootstrap variance estimation procedures.

Results:

Stigma was perceived by 24.4% of respondents accessing mental health services. The frequency was higher among younger respondents (<55 years), those who were not working, those reporting only fair or poor mental health, and the subset who reported having received a diagnosis of a mental disorder. Sex and education level were not associated with perceived stigma. People with schizophrenia reported stigmatization only slightly more frequently than those with mood and anxiety disorders.

Conclusions:

Stigmatization is a common, but not universal, experience among Canadians using services for mental health reasons. Stigmatization was a problem for a sizeable minority of respondents with mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders as well as bipolar and psychotic disorders.

Keywords: stigmatization, perceived stigma, discrimination, mental health, mental disorders, cross-sectional study, population study, epidemiologic study

Abstract

Objectif:

Une estimation actuelle des taux de prévalence des troubles mentaux chez les détenus canadiens sous responsabilité fédérale est nécessaire pour faciliter la prestation des traitements et la planification des services.

Méthode:

L’étude a déterminé les taux de prévalence des troubles mentaux majeurs chez les détenus masculins nouvellement incarcérés, entrant dans le système correctionnel fédéral du Canada. Les données ont été recueillies à chaque centre régional de réception pour les admissions consécutives durant une période de 6 mois (N = 1 110). Les taux de prévalence de durée de vie et actuels ont été estimés à l’aide de l’entrevue clinique structurée pour les troubles de l’axe I du DSM (SCID-I) et de l’entrevue clinique structurée pour les troubles de l’axe II (SCID-II). Le degré d’incapacité a été estimé à l’aide de l’Échelle d’évaluation globale du fonctionnement (GAF). Les résultats ont été désagrégés par ascendance autochtone.

Résultats:

Le taux de prévalence national pour tout trouble mental actuel était de 73%. Les taux les plus élevés étaient liés aux troubles d’utilisation de substances et d’alcool; toutefois, près de la moitié des participants satisfaisaient aux critères de durée de vie d’un trouble mental majeur autre que les troubles d’utilisation de substances et d’alcool ou que le trouble de la personnalité antisociale. Trente-huit pour cent satisfaisaient aux critères tant d’un trouble mental actuel que d’un trouble d’utilisation de substances. Cinquante-sept pour cent des détenus souffrant d’un trouble mental actuel de l’axe I ont été estimés présenter une incapacité fonctionnelle de minimale à modérée d’après la GAF, indiquant que la majorité des participants ne nécessitent pas de services psychiatriques intensifs.

Conclusions:

Ces résultats soulignent le problème posé aux établissements correctionnels fédéraux du Canada en ce qui concerne la prestation de services de santé mentale nécessaires pour aider à la gestion et à la réhabilitation de la population des détenus ayant des besoins de santé mentale.

Stigmatization refers to a negative social response to people who have a mental illness, resulting in prejudice, discrimination, and social exclusion. Addressing stigma has been the target of national initiatives in many countries. Fighting stigma was prioritized in the Canada’s “Changing Directions, Changing Lives”1 mental health strategy and is one of the pillars of the Mental Health Commission of Canada’s activities through its Opening Minds Initiative.2

Stigmatization interferes with mental health care on many levels, such as by discouraging help seeking.3 Consumer surveys indicate that stigma and discrimination are perceived from family and friends, employers, and also from health professionals.4,5 A report from the Mood Disorders Society of Canada6 forcefully expressed concerns about stigmatization in health settings, stating that people with mental illness “feel ignored in emergency rooms and treated disrespectfully by family physicians.” However, stigma is most often understood as public or personal stigma, a term that refers to prejudice and discrimination directed at people with mental illness by members of the population.7 Self-stigma refers to the internalization of such attitudes, resulting in feelings of shame, blame, and diminished self-worth. Perceived stigma involves perceptions (of those with a mental illness) of stigmatizing attitudes held by others8 and internalization of perceived stigma plays a role in the emergence of self-stigma.7 This is especially true for those who perceive legitimacy in extant social hierarchies.9

In Canada, a survey module assessing the frequency and impact of perceived stigma was developed by members of the Opening Minds antistigma initiative10 in collaboration with Statistics Canada.11 This module targets people who have accessed mental health services in the preceding year and is called the Mental Health Experiences Scale.12 The scale derived from earlier inventories and was modified by Statistics Canada following their in-house protocols. Modifications were made with the permission of the authors (including H.S.), and Statistics Canada staff tested the modified scales extensively using qualitative and quantitative methods.

The Mental Health Experiences Scale was used to collect population-based data during a “Rapid Response” survey conducted by Statistics Canada in 2010, funded by the Mental Health Commission of Canada.12 The sample included 10,389 respondents, but only 752 had sought mental health care in the previous year and thus were administered the scale. Of these, 38.5% reported that they had experienced negative opinions or discrimination as a result of a current or past mental health problem.8 Perceptions of stigmatization were most frequent in the youngest age group (12 to 25 years) and were more frequent in respondents reporting that their general mental health was fair or poor. The odds ratio for perceived stigmatization among those reporting fair or poor mental health was 2.8 (95% CI 1.2 to 6.7). However, the Rapid Response survey did not collect diagnostic information, leaving a gap in knowledge.

Inclusion of the Mental Health Experiences Scale in a 2012 national mental health survey called the Canadian Community Health Survey–Mental Health (CCHS-MH) provides an opportunity to replicate some of the previous (Rapid Response) findings and to address remaining knowledge gaps. The sample size for the CCHS-MH is more than twice as large as that of the prior Rapid Response survey and the CCHS-MH included standardized13 and self-reported information on psychiatric diagnoses. This is potentially important because mental health services are often accessed for reasons other than a diagnosed mental disorder (for example, family or marital therapy or bereavement). The objective of the current study was to estimate the frequency of perceived stigmatization in the subgroup of the population reporting that they had received mental health services in the year prior to the survey in relation to mental health indicators such as the presence of a disorder and self-perceived mental health status.

Methods

Detailed methodological information on the CCHS-MH is available from Statistics Canada archives14 and from recent epidemiological reports.15 In brief, the survey targeted Canadian household residents aged 15 years and older living in any of the 10 provinces. The sampling procedures were based on an area frame designed for the Labour Force Survey, leading to exclusion of persons living on reserves and other Aboriginal settlements, full-time members of the Canadian Forces, and residents of institutions. These exclusions amount to approximately 3% of the national population. A three-stage sampling procedure was used. This was based initially on selection of geographical clusters followed by selection of households from within those clusters and finally by selection of one respondent per household. Data collection occurred between January 2, 2012 and December 31,2012. A total of 25,113 interviews were conducted (a 69% response rate). Most of the interviews (87%) were conducted in person.

The survey included a Canadian adaptation of the World Mental Health (WMH) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI),16 which generated Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, diagnoses for major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, alcohol abuse and dependence, and drug abuse and drug dependence, although questions have been raised about the accuracy of the bipolar disorder diagnoses.15 The survey also collected information about self-reported professionally diagnosed disorders including mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and schizophrenia or other psychoses. The WMH-CIDI does not assess schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders because, as a fully structured interview, its accuracy for these conditions is questionable.17

The Mental Health Experiences Scale was administered to respondents reporting past-year receipt of mental health services. The rationale for this decision is that the process of stigmatization is usually connected to labelling, such as the identification (by a professional) of a disorder considered to be in need of treatment. Receipt of services was determined using two questions: 1) Have you ever received treatment for an emotional or mental health problem? 2) Was this in the past 12 months? The group responding affirmatively to both questions was asked whether “anyone held negative opinions” or “treated you unfairly” because of “your past or current emotional or mental health problem.” If perceived stigma was reported, its impact was assessed using the following: “Please tell me how this affected you. For each question, answer with a number between 0 and 10; where 0 means you have not been affected while 10 means you have been severely affected.” The domains assessed were family relationships, romantic life, school or work life, financial situation, housing situation, and accessing health care services for physical health. Another CCHS-MH survey item asked “In general, would you say your mental health is…?,” with response options being excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. A set of CCHS-MH items also asked respondents whether they had discontinued treatment and, if so, why. One of the options was “discrimination/unfair treatment/embarrassment,” which allowed tabulation of the percentage of treatment discontinuation due to these reasons. Responses to this item seemed relevant to the goals of the study and were therefore tabulated in the analysis.

The analysis was based primarily on estimating means and frequencies with associated 95% confidence intervals. Unexpected findings were addressed in an unplanned analysis using a logistic regression (see the Results, below). All analyses used a recommended procedure incorporating replicate bootstrap weights to help ensure valid inference in view of the complexities of the study design (including different selection probabilities and clustering). Despite the use of these procedures, Statistics Canada suppresses estimates with very small cell sizes. In the current analysis, it was not possible to incorporate elevated distress levels (which were measured using the Kessler-6 distress scale18) due to small cell sizes encountered in the analysis.

Results

Details of the CCHS-MH sample (n = 25,113) have been reported previously.19 As a result of the sampling (and associated weighting) procedures employed, the demographics of the sample were representative of the Canadian household population. The (weighted) percentage of the sample who were women was 50.7% and the mean age was 45.7 years. Table 1 summarizes annual prevalence data from the survey.

Table 1.

Annual prevalence of CIDI-diagnosed and self-reported disorders in the CCHS-MH.

| Disorder | Weighted Frequency |

|---|---|

| CIDI-diagnosed disorder | |

| Major depressive episode | 4.7 (4.3 to 5.1) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 2.6 (2.3 to 2.80) |

| Bipolar disorder I and IIa | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) |

| Alcohol dependence | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| Alcohol abuse | 2.2 (1.9 to 2.5) |

| Drug dependence | 0.8 (0.6 to 0.9) |

| Any drug abuse | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) |

| Self-report disorders | |

| Anxiety disorder | 4.8 (4.5 to 5.2) |

| Mood disorder | 7.0 (6.4 to 7.50) |

| Schizophrenia/psychosis | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) |

Data are given as percentages (95% confidence intervals). CCHS-MH, Canadian Community Health Survey–Mental Health; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

aAccording to recommended CIDI scoring algorithms.

During administration of the stigma module, 17.9% (95% CI 17.1 to 18.7) of respondents reported that they had received mental health care, with 46.5% (95% CI 44.2 to 48.8) of these reporting that they had received treatment within the preceding 12 months. As such, the current analysis is based on the experiences of an estimated 8.3% (0.179 × 0.465 × 100) of the Canadian household population. Overall, 24.4% of this group reported encountering prejudice or discrimination because of their mental health, representing approximately 2.0% (0.083 × 0.244 × 100) of the overall Canadian population. The proportion of those accessing treatment in the preceding year and who reported stigmatization was similar in men (21.9%; 95% CI 17.5 to 26.4) and women (25.8%; 95% CI 21.9 to 29.8) and in respondents with less than secondary school education (30.2%; 95% CI 17.9 to 42.3) versus secondary-level graduation (23.3%; 95% CI 15.3 to 31.3) or postsecondary education (23.8; 95% CI 20.4 to 27.1). However, consistent with the earlier report,8 there was a lower frequency of stigmatization reported by older respondents. Among those over older than 55 years, only 12.5% (95% CI 9.3 to 15.6) reported stigmatization.

Among those indicating that their mental health was very good or excellent, only 11.8% (95% CI 7.8 to 15.7) reported stigmatization, whereas the frequency was 20.1% (95% CI 15.6 to 24.5) in those reporting merely “good” mental health. Among those reporting fair or poor mental health, 36.6% (95% CI 31.1 to 42.1) reported stigmatization.

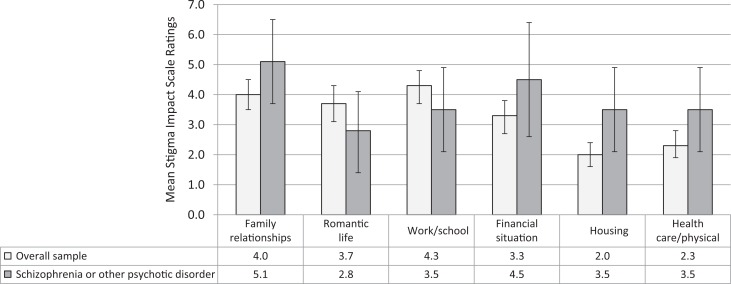

Figure 1 shows ratings on the Stigma Impact Scale. In the overall sample, the highest impact was reported to occur in the areas of work/school and family and romantic relationships. Disorder-specific comparisons were inconclusive as a result of low precision, but Figure 1 also reports the pattern for schizophrenia or other psychosis because this group is believed to be strongly affected by stigma. Although statistically significant differences were not observed, these participants reported a slightly lower impact of stigma in school/work and romantic relationships, but higher impact in other areas such as family relationships, finances, housing, and health care.

Figure 1.

Mean Stigma Impact Scale ratings (95% confidence intervals) in the overall sample, and in those with self-reported schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder. The number with schizophrenia is 410, which is rounded due to Statistics Canada data release guidelines.

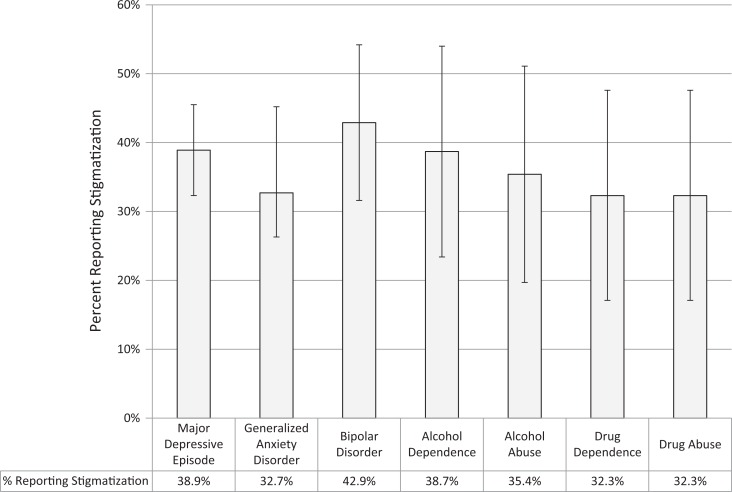

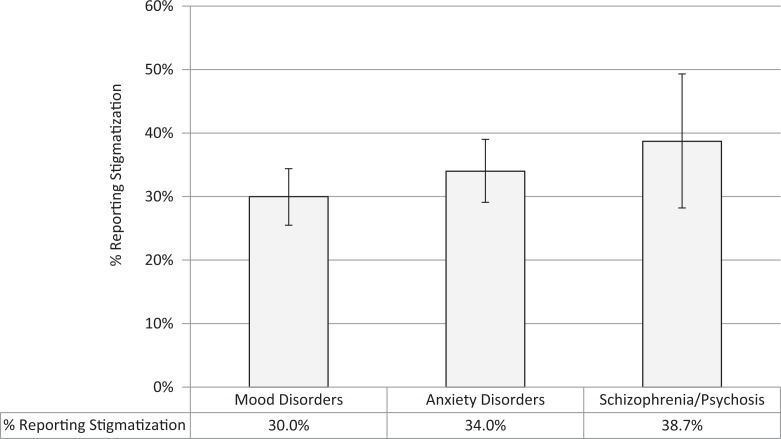

Figures 2 and 3 present the frequency of stigmatization in relation to disorder status for CIDI-based diagnoses and self-reported diagnoses, respectively. Notably, according to their 95% confidence intervals, all of these estimates are consistent with a 30% frequency of stigmatization.

Figure 2.

Frequency of perceived stigmatization with 95% confidence intervals, by Composite International Diagnostic Interview diagnostic category.

Figure 3.

Frequency of perceived stigmatization with 95% confidence intervals, by Composite International Diagnostic Interview diagnostic category.

In view of the finding that poor perceived mental health, CIDI diagnoses, or self-reported disorders were all associated with perceived stigmatization, we sought, in an unplanned analysis, to evaluate the independent effects of these variables on perceived stigmatization. Table 2 shows the joint relationship between having a CIDI-diagnosed disorder and self-reported mental health. As expected, there is a strong relationship between having a disorder and perceived mental health status, but they do not assess exactly the same thing. Approximately 25% of those with a disorder reported very good or excellent mental health and 4.4% of those without any of the disorders covered by the CIDI reported only fair or poor mental health.

Table 2.

CIDI or self-report diagnosis and perceived mental health.

| Perceived Mental Healtha | CIDI or Self-Reported Diagnosis of a Mental Disorder | No CIDI or Self-Reported Diagnosis of a Mental Disorder |

|---|---|---|

| Very good/excellent | 24.9 (20.0 to 24.9) | 69.8 (68.7 to 70.9) |

| Moderate | 38.8 (35.8 to 41.7) | 25.8 (24.8 to 26.8) |

| Fair/poor | 38.7 (35.8 to 41.6) | 4.4 (4.0 to 4.8) |

Data are given as percentages (95% confidence intervals). CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

aThis item was worded as follows: “In general, would you say your mental health is… excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?”

After assessing interactions between these variables using cross-product interaction terms in a logistic regression model (no significant interactions were found), all three variables were included in a model predicting perceived stigmatization as an outcome. Compared with people reporting very good or excellent mental health, having fair or poor mental health (OR 3.0; 95% CI 1.9 to 4.7), good mental health (OR 1.7; 95% CI 1.1 to 2.8), as well as any CIDI diagnosis (OR 2.1; 95% CI 1.5 to 2.9) was independently associated with stigmatization. However, having any self-reported professional diagnosis was no longer significantly associated with perceived stigma (OR 1.2; 95% CI 0.8 to 1.8). Among those who reported being diagnosed with a disorder but who had none of the disorders assessed by the CIDI, only 18.2% (95% CI 13.9 to 22.5) reported stigma. On the other hand, among those who had a CIDI diagnosis but did not report having been diagnosed with a disorder, the frequency of perceived stigma was 25.1% (95% CI 16.2 to 33.9).

In analysis of the treatment discontinuation data, the most common reasons for discontinuing treatment were “felt better” (which ranged between 16% and 42%, depending on the disorder) or (treatment was) “not helping” (approximately 20% for all disorders). Another response option was “discrimination/unfair treatment/embarrassment.” Depending on the disorder, between 2.0% and 6.4% of participants reported discontinuing treatment for this reason.

Discussion

This study helps to quantify the stigma perceived by Canadians accessing mental health care. Although the frequencies are high (in the range of 30% to 40% for those with the various disorders assessed), the experience of stigmatization was not universal. Interestingly, although the sample was restricted to those receiving mental health services in the past year, not all of the respondents had evidence of a disorder, either as discerned by the CIDI or by self-report. Some people seek mental health care for reasons other than mental disorders per se (such as stress management, marital problems), and such individuals appear to perceive stigmatization less often than those with a diagnosis.

It is often assumed that stigmatization is an inevitable component of the experience of mental illness. The analysis reported here does not directly support this idea. The experience of stigmatization may diminish with time as people learn to cope with their illness. Some respondents who did not report stigma in this survey may have experienced it at an earlier time in their life. The observation that stigma was more often reported by younger respondents is consistent with this possibility.

Some respondents who reported very good or excellent mental health had mental disorders (either by self-report or according to the CIDI). Some of these may have recovered from disorders or may have sought mental health care for issues (such as marital problems, family problems or postrecovery monitoring) that did not negatively affect their perceptions of their own mental health at the time of the survey. In this study, those with mental disorders reported higher levels of stigmatization than those without, consistent with the international literature.20,21 A possible explanation is that diagnostic labelling may have contributed to perceived stigmatization in those with mood and anxiety disorders. For example, Birchwood et al22 reported a strong association between social phobia and shame beliefs among people recently diagnosed with schizophrenia. However, in our study, self-perceived mental health and having a disorder had an independent association with stigmatization even among those who did not report having been diagnosed (“labelled”) with a disorder. CIDI diagnoses are based primarily on symptom patterns and do not depend on having received a professional diagnosis. However, respondents may have self-labelled in ways that were conducive to perceived stigmatization. Theoretically, the results may reflect greater levels of stigmatization among those with poorer mental health or may reflect an impact of poor mental health on perceptions of stigmatization. Because the CCHS-MH is a cross-sectional study, another possible interpretation must be considered: that perceived stigmatization may have been a negative prognostic factor for mental disorders (for example, increasing their prevalence by prolonging their duration or increasing rates of relapse). People with mood disorders may be sensitive to negative evaluation by others as a result of symptoms such as low self-esteem. Similar processes may unfold in anxiety disorders (especially social anxiety disorder, which was not assessed in the CCHS-MH). The association of mood and anxiety disorders with perceived stigma is consistent with international surveys21,23 that used two items from the World Health Organization’s Disability Assessment Schedule to assess perceived stigma. A 13.5% prevalence of stigmatization among respondents with mental disorders and significant disability was found.

There are few international studies against which to compare these results. In the United Kingdom, the “Time to Change” antistigma initiative included a survey of specialist mental health care patients called the Viewpoint Survey.24 The Viewpoint Survey included a validated scale for perceived stigma. The frequency of stigma was much higher than in the CCHS-MH, falling in the range of 87% to 91% during different iterations of the survey conducted during 2008 to 2011. This higher frequency of perceived stigma may reflect different measurement approaches or the targeting of the Viewpoint Survey toward specialty mental health patients, or it may be an artifact of a low response rate (Viewpoint Survey response rates ranged between 6% and 11% depending on the year of the survey).

The reported pattern of impact of stigma, overall, is consistent with that reported in the previous Rapid Response module,12 with the most impacted life domains being those in which close interpersonal contact occurs (family and close friends, romantic relationships, and work or school). However, these results tentatively suggest that the pattern of impact may differ depending on the diagnosis. In turn, this may reflect the contexts associated with various disorders. In schizophrenia, for example, the frequency of perceived impact of stigma was lowest for romantic relationships and higher for finances, work/school, housing, and physical health care. A lower frequency of involvement in romantic relationships could also explain the result. However, an examination of the confidence intervals in Figure 1 indicates that the current study did not achieve sufficient precision to confirm different patterns of impact on these different domains of life.

Levels of stigmatization are generally believed to be higher in people with schizophrenia than in other disorders. For example, using Swedish national opinion data, Wood et al25 reported that schizophrenia was associated with more negative stereotypes than depression or anxiety. However, this study examined public stigma rather than perceived stigma. In the International Study of Discrimination and Stigma Outcomes, perceived stigma was only slightly higher among people with schizophrenia than major depression.26,27 In the current study, levels of reported stigmatization were surprisingly similar between the various classes of disorders, all in the range of 30% to 40%. However, the overall frequency was slightly higher in people reporting that they had a psychotic disorder.

To our knowledge, this study is only the second study reporting population-based data for stigma in Canada. Stigma is difficult to measure in community populations and the CCHS-MH restricted its attention to perceived stigma in those receiving mental health care. The approach does not distinguish between the perception of stigma and the actual occurrence of stigmatizing or discriminatory behaviours on the part of others. In addition, the source of the perceived stigmatization was not assessed. Sources may have included health professionals, family, employers, or many others. The current study found a lower overall frequency of perceived stigma (approximately 25% versus 38.5%) than the one prior Canadian population survey,12 a finding that is difficult to interpret.

It is worth noting that the problem of stigma is not restricted to mental disorders, although its assessment in the CCHS focused on mental health. Stigmatized conditions include epilepsy, HIV/AIDS, and hepatitis C. A quote28 from a 25-year-old Ugandan woman reacting to a person with onchocerciasis (a neglected tropical disease) resembles mental illness stigma: “No one will allow them to lead, and many people ignore them. They are considered dangerous. People fear contact with them.” Leprosy, for example, is highly stigmatized and it is believed that public health strategies to combat the disease are negatively affected by this stigma.29 Interestingly, one of the most important messages in combatting mental health stigma is that recovery is possible.30 In leprosy, an analogous message is important: that leprosy can be cured.31

A limitation of this study was that the data collection was restricted to participants who had received treatment in the preceding year. Because stigmatization is one of the reasons why a person might stay away from mental health treatment, a study that focuses only on those accessing treatment may underestimate the burden of stigma in the population. For example, because the process of stigmatization often involves labelling, people may stay away from clinical settings in which they believe they may be labelled. As such, stigmatization of those who experience mental health problems but have not recently sought treatment was not assessed. The Mental Health Experiences Scale focuses on those receiving treatment in the past year in an effort to make the tool more useful for monitoring stigma over time.8 Although the existence of a field-tested module for assessment of perceived stigma is important, the lack of independent validation of the Mental Health Experiences Scale is a limitation of studies using this scale. In addition, although the scale was developed for use in epidemiology, the core of one of its questions may be useful as a modifiable prototype question for exploring the issue of stigma during clinical interactions: “Do you feel that anyone held negative opinions about you or treated you unfairly because of your emotional or mental health problem?”

Additional limitations relate to the lack of measurement of some correlates of perceived stigma in prior studies (most of which examined specific groups such as immigrants or youths), such as a low level of mental health literacy32 or having a family member with a mental illness.33 In some cases, greater knowledge may be associated with lower stigma, as may contact with others having the illness.

Conclusions

Public stigma exerts its influence partially through processes by which it is internalized by those who are stigmatized, leading, for example, to diminished self-esteem.2 It also exerts its impact through enactment in the form of discrimination, thereby becoming an issue of civil rights.12 The results presented here suggest the existence of an interplay between mental health itself and processes of stigmatization. Specifically, both mental health status itself and perceptions of mental health status may contribute to the perception of stigma or, alternatively, stigma may be an important negative determinant of mental health status. Effects going in both directions may occur, something that longitudinal studies could help to clarify.

Acknowledgements

Scott B. Patten is a senior health scholar with Alberta Innovates, Health Solutions. He has received support from the Mental Health Commission of Canada, Opening Minds. Heather Stuart holds the Bell Canada Mental Health and Anti-Stigma Research Chair. Keltie McDonald is recipient of a Canadian Institutes of Health. The analysis was conducted at Prairie Regional Data Centre, which is part of the Canadian Research Data Centre Network (CRDCN). The services and activities provided by the CRDCN are made possible by the financial or in-kind support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, Statistics Canada, and participating universities whose support is gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily represent the CRDCN’s or that of its partners. Data collection for the CCHS was carried out by Statistics Canada, but the analyses and interpretations presented here are those of the authors, not Statistics Canada.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research operating grant (MOP-130415). The study also received support from a Hotchkiss Brain Institute Grant “Depression in the Community.”

References

- 1. Mental Health Commission of Canada. Changing Directions, Changing Lives: The Mental Health Strategy for Canada. 2012 [cited 2014 Nov 17]. Available from http://strategy.mentalhealthcommission.ca/pdf/strategy-text-en.pdf.

- 2. Stuart H, Chen SP, Christie R, et al. Opening minds in Canada: background and rationale. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(10 Suppl 1):S8–S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol. 2004;59(7):614–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wahl OF. Mental health consumers’ experience of stigma. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(3):467–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mental Health Foundation. Pull Yourself Together! Update; 2000 [cited 2015 Nov 24]. Available from http://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/publications/pull-yourself-together-update/

- 6. Mood Disorders Society of Canada. Stigma and discrimination – as expressed by mental health professionals. 2007 Nov 12 [cited 2015 Nov 24]. Available from http://www.mooddisorderscanada.ca/documents/Publications/Stigma_and_discrimination_as_expressed_by_MH_Professionals.pdf.

- 7. Corrigan PW, Rao D. On the self-stigma of mental illness: stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(8):464–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Griffiths KM, Batterham PJ, Barney L, et al. The Generalised Anxiety Stigma Scale (GASS): psychometric properties in a community sample. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rusch N, Lieb K, Bohus M, et al. Self-stigma, empowerment, and perceived legitimacy of discrimination among women with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(3):399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mental Health Commission of Canada. Opening Minds; 2012 [updated 2014]; cited 2014 Nov 17]. Available from http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/initiatives-and-projects/opening-minds.

- 11. Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey–Mental Health Stigma and Discrimination Content Module - Test (CCHS); updated 2008 May 5 [cited 2015 Aug 19]. Available from http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=5152&lang=en&db=imdb&adm=8&dis=2.

- 12. Stuart H, Patten S, Koller M, et al. Stigma in Canada: results from a rapid response survey. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(Suppl1):s27–s33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed Washington (DC; ): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Canadian Community Health Survey–Mental Health Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2011. [updated 10 September 2014]; [cited 6 September 2014]. Available from: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca:81/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=5015&lang=en&db=imdb&adm=8&dis=2.

- 15. McDonald KC, Bulloch AGM, Duffy A, et al. Prevalence of bipolar I and II disorder in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(3):151–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):83–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eaton WW, Romanoski A, Anthony JC, et al. Screening for psychosis in the general population with a self-report interview. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179(11):689–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato D, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of major depression in Canada in 2012. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(1)23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2004;(420):21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alonso J, Buron A, Rojas-Farreras S, et al. Perceived stigma among individuals with common mental disorders. J Affect Disord. 2009;118(1-3):180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Birchwood M, Trower P, Brunet K, et al. Social anxiety and the shame of psychosis: a study in first episode psychosis. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(5):1025–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alonso J, Buron A, Bruffaerts R, et al. Association of perceived stigma and mood and anxiety disorders: results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118(4):305–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Corker E, Hamilton S, Henderson C, et al. Experiences of discrimination among people using mental health services in England 2008-2011. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2013;55:s58–s63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wood L, Birtel M, Alsawy S, et al. Public perceptions of stigma towards people with schizophrenia, depression, and anxiety. Psychiatry Res. 2014;220(1-2):604–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lasalvia A, Zoppei S, Van Bortel T, et al. Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination reported by people with major depressive disorder: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2013;381(9860):55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Rose D, et al. ; INDIGO Study Group. Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2009;373(9661):408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Weiss MG. Stigma and the social burden of neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2(5):e237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kazeem O, Adegun T. Leprosy stigma: ironing out the creases. Lepr Rev. 2011;82(2):103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Knaak S, Modgill G, Patten SB. Key ingredients of anti-stigma programs for health care providers: a data synthesis of evaluative studies. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(10 Suppl 1):S19–S26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Luko EE. Understanding the stigma of leprosy. South Sudan Medical Journal; updated 2010 [cited 2015 Nov 24]. Available from http://www.southsudanmedicaljournal.com/archive/august-2010/understanding-the-stigma-of-leprosy.html.

- 32. Copelj A, Kiropoulos L. Knowledge of depression and depression related stigma in immigrants from former Yugoslavia. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13(6):1013–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Calear AL, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Personal and perceived depression stigma in Australian adolescents: magnitude and predictors. J Affect Disord. 2011;129(1-3):104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]