Abstract

Objective

Teen dating violence is a serious public health problem. A cluster-randomized trial was conducted to assess the efficacy of Teen Choices, a 3-session online program that delivers assessments and individualized guidance matched to dating history, dating violence experiences, and stage of readiness for using healthy relationship skills. For high risk victims of dating violence, the program addresses readiness to keep oneself safe in relationships.

Method

Twenty high schools were randomly assigned to the Teen Choices condition (n=2,000) or a Comparison condition (n=1,901). Emotional and physical dating violence victimization and perpetration were assessed at 6 and 12 months in the subset of participants (total n=2,605) who reported a past-year history of dating violence at baseline, and/or who dated during the study.

Results

The Teen Choices program was associated with significantly reduced odds of all four types of dating violence (adjusted ORs ranging from .45 to .63 at 12 months follow-up). For three of the four violence outcomes, participants with a past-year history of that type of violence benefited significantly more from the intervention than students without a past-year history.

Conclusions

The Teen Choices program provides an effective and practicable strategy for intervention for teen dating violence prevention.

Keywords: dating violence prevention, computerized intervention, stages of change, relationship skills, cluster-randomized trial, adolescence

Today, 21 states in the U.S. have laws that encourage or require school districts to develop and/or offer a curriculum for teen dating violence prevention (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2014), a serious public health problem. Adolescent victims of dating violence are at higher risk for substance abuse, unhealthy weight control, risky sexual behavior, pregnancy, suicidality (Silverman, Raj, Mucci, & Hathaway, 2001; Wingood, DiClemente, Mccree, Harrington, & Davies, 2001), and future partner violence (Smith, White, & Holland, 2003). Most of the dating violence prevention programs described in the literature seek to increase awareness about teen dating violence, its warning signs, and services available, and to change gender stereotypes and other attitudes supporting violence against women. Many also seek to change behavior by teaching relationship skills that are healthy alternatives to violence and abuse. While some programs are designed to be delivered to at-risk youth (Wolfe et al., 2003; Ball et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2013), most are delivered universally, to all students, via classroom-based curricula and school-wide events (Weisz & Black, 2001; Tharp, 2012; Wolfe et al., 2009; Foshee et al., 2000). The purpose of the current study is to assess the efficacy of a universal dating violence prevention program delivered by computer.

Three universal programs tested in large-scale cluster-randomized trials have found significant program effects on reducing dating violence. The first, called Fourth R: Skills for Youth Relationships (Wolfe et al., 2009), includes seven 75-minute sessions focusing on healthy relationships, healthy sexuality, and substance abuse prevention. Additional school-level components include teacher training on dating violence and healthy relationships, information for parents, and student-led “safe school committees.” The second intervention, Safe Dates (Foshee et al., 2000), designed for 8th and 9th graders, includes a school theater production, a poster contest, ten 45-minute classroom sessions taught by health and physical education teachers, and the provision of special services for victims of violence and community service training for providers. The third, Shifting Boundaries (Taylor, Mumford, & Stein, 2015), designed for middle schools students, includes six classroom sessions led by Substance Abuse Prevention and Intervention Specialists, as well as a “building intervention” that helps students to identify unsafe areas in the school and allows for building-based restraining orders.

There are several challenges to delivering universal teen dating violence prevention programs in a school setting. First, it is difficult to ensure that programs are implemented fully and with fidelity (Pettigrew et al., 2013; Ringwalt et al., 2010). Programs that require professional interventionists or significant teacher training or class time, like the model programs described above, may be particularly difficult to deliver with fidelity. In the current-day lives of health educators and other teachers, barriers to delivering evidence-based dating violence prevention programs include the demands of teaching to core standards and limited time and resources. Second, universal programs are one-size-fits-all, neglecting individual differences in dating history and history of dating violence victimization and perpetration. Third, students can differ widely in their openness to messages about dating violence and healthy ways of relating.

Teen Choices: A Program for Healthy, Non-Violent Relationships was designed to address many of the challenges to delivering traditional teen dating violence prevention interventions (Levesque, Johnson, & Prochaska, in press). First, the program is computerized and can be administered with fidelity, with little staff time and training. Second, the program assesses and delivers individualized feedback and guidance matched to the adolescent's dating history, history of dating violence victimization and perpetration, and other relevant characteristics. Third, the program is based on an evidence-based model of health behavior change, the Transtheoretical Model (TTM). Research on the TTM has found that behavior change involves progress through a series of stages of change—Precontemplation (not ready), Contemplation (getting ready), Preparation (ready), Action (making behavioral changes), and Maintenance (maintaining changes) (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983). The model includes three additional dimensions central to change: 1) decisional balance—the pros and cons associated with a behavior's consequences (Janis & Mann, 1977); 2) processes of change—10 cognitive, affective, and behavioral activities that facilitate progress through the stages of change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1985); and 3) self-efficacy—confidence to make and sustain changes in difficult situations, and temptation to slip back into old patterns (Bandura, 1977).

More than 35 years of research on the TTM have identified particular principles and processes of change that work best in each stage to facilitate progress. TTM stage-matched interventions have been found effective across dozens of behaviors, including smoking cessation (Velicer, Prochaska, & Redding, 2006), domestic violence cessation (Levesque, Ciavatta, Castle, Prochaska, & Prochaska, 2012), and bullying prevention (Evers, Prochaska, Van Marter, Johnson, & Prochaska, 2007). Meta-analyses of health interventions have found that those tailored to stage produce significantly greater effects than those not tailored to stage (Noar, Benac, & Harris, 2007; Krebs, Prochaska, & Rossi, 2010).

Today, the National standards for K-12 health education require that students not only demonstrate comprehension of key concepts, but also “demonstrate the ability to practice health-enhancing behaviors and avoid or reduce health risks” (Joint Committee on Health Education Standards, 2007), pointing to the importance of integrating an evidence-based model of behavior change like the TTM. For most students, Teen Choices seeks to reduce risk for dating violence by facilitating progress through the stages of change for using five healthy relationship skills: 1) trying to understand and respect the other person's feelings and needs; 2) using calm, nonviolent ways to deal with disagreements; 3) respecting the other person's boundaries; 4) communicating feelings and needs clearly and respectfully; and 5) making decisions that you know are good for you in relationships. Daters are encouraged to use those skills in their dating relationships, and non-daters in their peer relationships, as relationships with peers serve as the foundation for experiences in romantic relationships (Connolly, Furman, & Konarski, 2000; Furman, Simon, Shaffer, & Bouchey, 2002).

For victims of dating violence experiencing fear and who screen positive on a risk assessment (e.g., Does this person try to control most of your daily activities? Are you afraid of what this person will do to you if you tell others about what's happening?), Teen Choices does not focus on healthy relationship skills; instead, it seeks to facilitate progress through the stages of change for keeping oneself safe in relationships. During intervention development, consultants expressed concern that a focus on healthy relationship skills might encourage self-blame among the highest risk victims and encourage them to “work” on their relationship, thereby increasing—rather than reducing—their risk for future violence. In the program, “Keeping oneself safe” is operationally defined as: 1) getting help; 2) making a safety plan; and 3) deciding whether the relationship is right for you.

Goal of the Current Study and Hypotheses

A pilot test of a prototype of the Teen Choices program provided encouraging evidence of the acceptability and feasibility of this approach to intervention (Levesque, Johnson, & Prochaska, in press). The remainder of this paper describes a cluster-randomized trial assessing its efficacy. Outcomes, assessed at 6 and 12 months follow-up, will be reported for the subsample of youth exposed to at least minimal risk for dating violence—that is, participants who had experienced or perpetrated emotional or physical dating violence in the year prior to the study, who were current daters at baseline, or who dated during follow-up. The primary outcomes were emotional and physical dating violence victimization and perpetration; secondary outcomes were consistent use of healthy relationship skills and rejection of attitudes supporting dating violence. It was hypothesized that:

-

1)

Compared to students in the Comparison condition, students assigned to Teen Choices would have significantly reduced odds of four types of dating violence during follow-up: emotional victimization, emotional perpetration, physical victimization, and physical perpetration;

-

2)

Students assigned to Intervention would have significantly increased odds of consistently using healthy relationship skills at follow-up;

-

3)

Students assigned to Intervention would have significantly increased odds of rejecting all attitudes supporting teen dating violence at follow-up; and

-

4)

All findings would remain significant after adjusting for potential confounds and covariates.

Finally, for each of the four dating violence outcomes, analyses examined whether results were moderated by past-year history of that type of violence, gender, race/ethnicity, grade in school, and baseline stage of change.

Method

Participants

Twenty Rhode Island high schools agreed to participate in the study. A Multiattribute Utility Measurement Approach (Graham, Flay, Johnson, Hansen, & Collins, 1984) was used to ensure that schools assigned to Intervention and Comparison were approximately equivalent on school size, student ethnicity, percent of students receiving free or reduced-price lunch, mobility, truancy, dropout, and standardized test performance. The most similar schools were paired, and one school within each pair was randomly assigned to Intervention, and the other to Comparison.

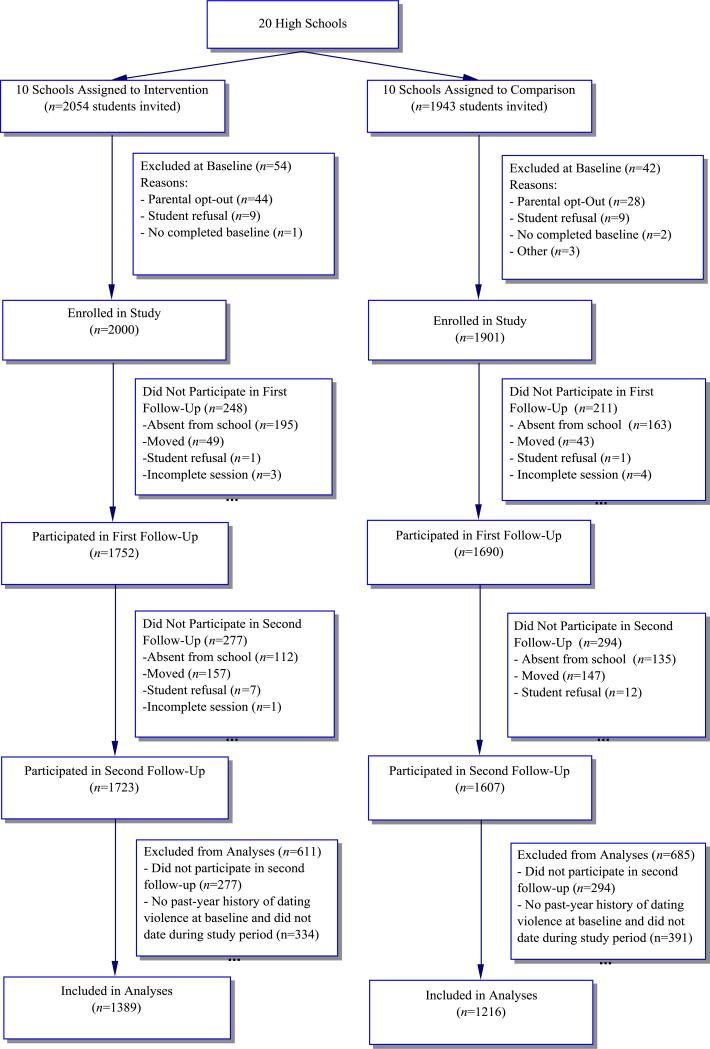

In the fall of 2009, primary contacts at the schools selected intact 9th, 10th, and/or 11th grade classes (e.g., 1st period Health) for participation in the trial, to yield school N's of 200 and a study N of 4,000. Of 2,054 students invited by Intervention schools to participate, 2,000 were enrolled in the study; of 1,943 students invited by Comparison schools, 1,901 were enrolled. Reasons for nonparticipation at baseline are provided in the Participant Flow Diagram (Figure 1). Study assessments were completed at baseline, 6 and 12 months follow-up. In the Intervention group, intervention sessions were completed at baseline, 1 and 2 months. All assessment and intervention sessions were completed by computer at school, accompanied by verbatim audio. Headphones were provided to protect privacy.

Figure 1.

Participant Flow Diagram

While the computer did not allow participants to skip any questions, participants were allowed to end their involvement at any time. Nonparticipants were provided with alternative activity. All assessment and intervention sessions were overseen by project research assistants. However, school personnel generally remained nearby to indicate their support for the project.

Study-wide, retention rates for the 6-month assessment were 87.6% (n=1,752) for Intervention and 88.9% (n=1,690) for Comparison. Students who did not participate in the 6-month assessment were allowed to participate at 12 months. Retention rates at 12 months were 86.2% (n=1,723) for Intervention and 84.5% (n=1,607) for Comparison. Reasons for non-participation at follow-up are reported in the Participant Flow Diagram (Figure 1).

Mixed-effects logistic regression models with a random intercept for school to account for the clustered study design examined predictors of nonresponse at follow-up. At 6 and 12 months, significantly (p<.05) lower rates of participation were found among students who were not white, who received subsidized lunch, who had more dating violence partners during the past year at baseline, who were dating at baseline, who reported that they were not straight or were unsure of their sexual orientation, who were in a pre-Action stage for using healthy relationship skills at baseline, who reported experiencing or perpetrating emotional or physical dating violence in the past year at baseline, and who did not receive a teen dating violence prevention (TDV) curriculum during follow-up. At 6 months only, there was lower participation among students who were freshman or juniors at baseline than among students who were sophomores.

Analysis Sample

Outcome analyses reported in the remainder of this report included 1,389 Intervention and 1,216 Comparison participants who completed the final assessment and were exposed to risk for dating violence—that is, students who had experienced or perpetrated emotional or physical dating violence in the year prior to the study, who were current daters at baseline, or who dated during follow-up. This represents 78.2% of the sample that completed the final assessment. Peer violence and other outcomes for 725 participants not exposed to risk for dating violence are reported elsewhere (Levesque, Johnson, Welch, Prochaska, & Paiva, 2016).

Group Equivalence

Using SAS GLIMMIX (SAS Institute, 2011), mixed-effects logistic regression models with a random intercept for school examined Intervention vs. Comparison group equivalence on demographics and baseline measures in the analysis sample. Results are reported in Table 1. There were two significant (p<.05) group differences at baseline: Teen Choices participants were more likely than Comparison to be freshmen or juniors at baseline and to have experienced physical victimization in a dating relationship in the year prior to the study. We also examined group equivalence in receipt of classroom-based TDV curricula during the study period. In all, 87.9% of the Intervention participants and 70.2% of Comparison participants in the analysis sample received a classroom-based TDV curriculum (F(1, 2585) = 0.98, ns).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Teen Choices and Comparison Participants^

| Variable | Teen Choices (n =1,389) | Comparison (n=1,216) | F (1, 2585) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | |||

| Gender | Female | 53.3% | 53.7% | 0.00 |

| Male | 46.7% | 46.3% | ||

| Race/ethicity | White, non-Hispanic | 82.2% | 76.1% | 0.05 |

| Other | 17.8% | 23.9% | ||

| Subsidized lunch | Yes | 22.2% | 23.4% | 0.04 |

| No/don't know | 77.8% | 76.6% | ||

| Grade in school^^ | Grade 9 | 26.7% | 19.3% | 4.41* |

| Grade 10 | 21.2% | 43.9% | ||

| Grade 11 | 51.8% | 36.7% | ||

| Dating partners past year | 0 | 15.4% | 15.5% | 1.75 |

| 1 | 28.1% | 33.2% | ||

| 2 | 23.4% | 24.0% | ||

| 3 or more | 33.0% | 27.2% | ||

| Current dating status | Dating | 40.3% | 36.7% | 3.26 |

| Not dating | 59.7% | 63.3% | ||

| Sexual orientation | Straight | 92.9% | 92.1% | 0.53 |

| Not straight/don't know | 7.1% | 7.9% | ||

| Stage of change for using skills | Pre-Action | 59.5% | 57.6% | 0.50 |

| Action or Maintenance | 40.5% | 42.4% | ||

| Consistent skill use | Yes | 12.8% | 13.6% | 0.37 |

| No | 87.2% | 86.4% | ||

| Reject dating violence attitues | Yes | 39.2% | 38.3% | 0.03 |

| No | 60.8% | 61.7% | ||

| Emotional victimization past year | Yes | 67.3% | 65.3% | 0.79 |

| No | 32.7% | 34.7% | ||

| Emotional perpetration past year | Yes | 57.3% | 54.9% | 0.68 |

| No | 42.7% | 45.1% | ||

| Physical victimization past year | Yes | 35.6% | 31.8% | 4.05* |

| No | 64.4% | 68.2% | ||

| Physical perpetration past year | Yes | 18.5% | 16.4% | 0.92 |

| No | 81.5% | 83.6% |

All participants in the analysis sample were exposed to risk for dating violence: they had experienced or perpetrated emotional or physical dating violence in the year prior to the study, were current daters at baseline, or dated during the follow-up period.

Three Intervention and one Comparison participant recorded their grade as “other.”

p <.05

The Teen Choices Intervention

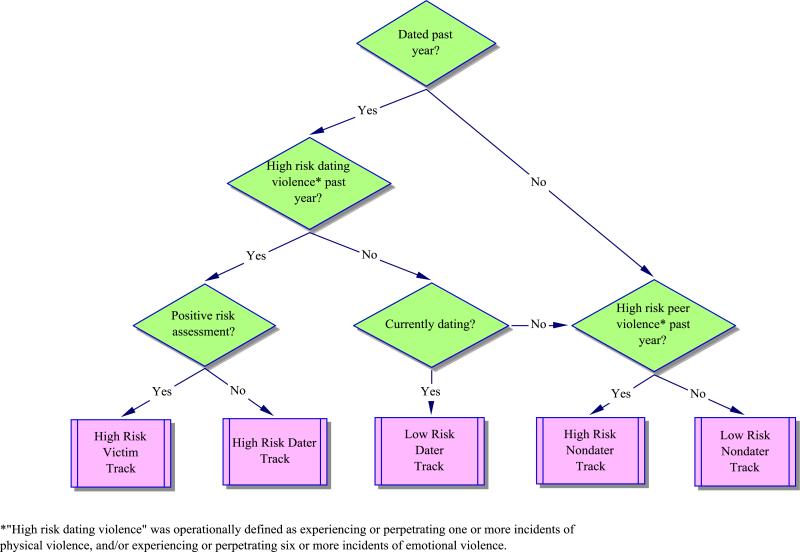

Teen Choices is a 3-session web-based multimedia (text, images, audio, video) expert system intervention that integrates, in a stage-matched manner, key content (e.g., warning signs, statistics on dating violence) and activities (e.g., expectations regarding the balance of power in dating relationships) found in evidence-based dating violence prevention programs. However, the intervention experience is individually tailored, with five intervention tracks to meet the unique needs of: 1) high risk victims; 2) high risk daters; 3) low-risk daters; 4) high risk nondaters; 5) low risk nondaters. Sessions last 25-30 minutes.

The baseline session began with an assessment of dating history and an assessment and feedback on dating violence experienced and perpetrated in the past year (for students who dated) or peer violence experienced and perpetrated (for students who did not date). Victims of dating violence were asked if, in the past month, they “felt scared or frightened by something a current or past dating partner might do to you.” Those reporting fear were administered a 5-item risk assessment. Participants were assigned to an intervention track based on responses to measures in this part of the session (see Figure 2 for track assignment decision rules).

Figure 2.

Teen Choices Decision Rules for Track Assignment

For all but the high-risk victim track, Teen Choices then delivered an assessment and feedback on five healthy relationship skills, including step-by-step guidance and videos demonstrating how to use two skills the participant had been using the least. Next came the TTM portion of the session, which included an assessment and feedback on stage of change for using healthy relationship skills and up to five TTM stage-matched principles and processes of change for using healthy relationship skills. The session ended with an assessment and feedback on level of alcohol use and its relationship to dating and peer violence; readiness to seek help if a victim or perpetrator of dating violence or peer violence; and readiness to offer help to others who are victims or perpetrators of dating or peer violence. For the high-risk victim track, the session was similarly structured but instead focused on keeping oneself safe in relationships. Screenshots from the Teen Choices program and decision rules for assessing stage of change for using healthy relationship skills and for keeping oneself safe are provided in Online Supplements 1 and 2, respectively.

Follow-up intervention sessions were similarly structured. In addition, they gave feedback on how participants had changed on key dimensions since the last session. Participants could transition between tracks over time (e.g., a nondater who began dating would transition to a dater track). However, participants could not transition from a high-risk to a lower-risk track.

In the trial, all assessment and intervention sessions ended with a Let's Talk About It webpage, which listed school- and community-specific help sources, along with state and national toll-free helplines and online support. (This webpage appeared at the end of assessment sessions for the Comparison group as well). For the Intervention group, additional intervention components included: 1) a program website providing access to a personal homepage with a link to replay session feedback, 15 videos demonstrating healthy relationship skills, the “Let's Talk About It” webpage, and 14 other activities (e.g., Warning Signs, Safety Planning); 2) a student guide describing the program and providing basic information on dating violence; 3) a school guide providing an overview of the clinical trial, a description of the Teen Choices program, frequently asked questions, computer requirements, and an implementation checklist; 4) school posters that included the web address for the Teen Choices website; and 5) a family guide providing basic information on dating violence and steps parents can take if they learn that their teen is a victim of dating abuse. Data on how much students or parents used the print guides and other intervention materials outside the online sessions were not collected.

Procedure

All study procedures and materials were IRB-approved. Via letters delivered to the home, parents were informed of the study's purpose, procedure, risks, and benefits, and asked to return an opt-out form if they did not want their child to participate. The intervention trial was launched in the Fall of 2009. Both the Intervention and Comparison groups completed a computerized baseline assessment and two follow-up assessments approximately 6 and 12 months later—in the Spring and Fall of 2010.

Students assigned to the Intervention condition completed their first Teen Choices intervention session immediately following their baseline assessment, and received the student and family print guides. Primary contacts at the Intervention schools received a school guide and several Teen Choices posters. The second and third intervention sessions were administered at 1 and 2 months follow-up. Students assigned to the Comparison condition completed an alternative evidence-based online TTM-based intervention, Health In Motion, which targets physical activity, screen time, and healthy eating for obesity prevention (Mauriello et al., 2010). Health In Motion sessions were administered following the baseline, 6-month, and 12-month assessments to increase the benefits of study participation for Comparison students.

In addition, both groups received the standard TDV curriculum offered at their school. Schools that offered no curriculum were provided with the Choose Respect materials developed by the DHHS and CDC (2006) and the Love Is Not Abuse curriculum developed by Liz Claiborne, Inc. and the Education Development Center, Inc. (n.d.).

Measures

Demographics and dating history

At baseline, questions assessed age, grade in school, gender, race, ethnicity, whether the teen received free or reduced-price lunch at school, and sexual orientation. At baseline and follow-up, questions assessed dating history and dating status. “Dating” was defined as “‘Going out with’ or ‘seeing’ someone you like or find attractive, or are emotionally or physically involved with. The two of you consider each other as more than just ordinary friends. You do things together, just the two of you, or with a larger group.”

Dating Violence

Because existing partner and teen dating violence measures were either quite lengthy—e.g., the 78-item Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996), had low alphas—e.g., the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (Wolfe et al., 2001), or were missing one or more key dimensions of abuse—e.g., the single item measure from CDC's Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey (Grunbaum et al., 2004), a 30-item measure assessing five types of dating violence victimization and perpetration was developed to meet specific needs of this research (Levesque & Paiva, 2016). Following the scoring conventions used in classic partner violence assessments (Straus et al., 1996; Straus, 1979), response options were Once, 2-5 times, 6-20 times, More than 20 times, and Never, and the midpoint was used in scoring (i.e., 2-5 times=3; 6-20 times=12; more than 20=25). For the five 3-item victim scales, sample items and Cronbach's Alphas for the current sample at baseline were: “Said something to put you down” (emotional mistreatment, α=.88); “Tried to stop you from spending time with your friends” (controlling behavior, α=.81); “Threatened to ruin your reputation” (threats, α=.89); “Kicked, bit, or hit you with a fist” (physical violence, α=.87); and “Touched you sexually when you didn’t want him/her to” (sexual coercion, α=.89). Alphas for the perpetrator versions of those five scales were .88, .75, .93, .89, and .90, respectively (Levesque & Paiva, 2016).

At baseline, instructions for the victimization measure were presented first: Think about all the people you've dated in the last year. Please tell us HOW MANY TIMES in total during the last year you've experienced each of the following from people you've dated. Instructions for the perpetration measure read: Now, tell us HOW MANY TIMES in total during the last year you've done each of the following to the people you've dated. At follow-up, in the spring and fall of 2010, the measure assessed dating violence experienced and perpetrated since January 1, 2010. A landmark event, New Year's Day, was used to mark the beginning of the reporting period to reduce memory biases (Loftus & Marburger, 1983).

Given the hierarchical structure of the victimization measure as determined by hierarchical confirmatory factor analysis (Levesque & Paiva, 2016), the emotional mistreatment and controlling behavior scales were combined to represent emotional dating violence victimization, and the threats, physical violence, and sexual coercion scales were combined to represent physical victimization. The two measures were then dichotomized (e.g., one or more incidents of emotional victimization during the period in question were coded as “yes,” and no incidents coded as “no”), given extreme non-normal distributions. In addition, reliance on dichotomous (yes/no) violence measures is consistent with the goal of the intervention: to prevent future dating violence. Finally, given the overlapping timeframes for the 6- and 12-month violence measures (the lookback period for the 12-month assessment subsumed the lookback period for the 6-month assessment), a “yes” at either timepoint was counted as a “yes” for a given 12-month violence outcome. Analogous scoring rules were used to score and code emotional and physical dating violence perpetration.

Consistent Use of Healthy Relationship Skills

At baseline and follow-up, participants were presented with the five healthy relationship skills listed above and asked to indicate how often they used each skill during the last month. Current daters were asked to focus on their relationship(s) with the people they were currently dating, and nondaters were asked to focus on their relationships with other people around their age. Response options were 1=never to 4=always. In the current sample at baseline, Cronbach's alpha was .73. Participants who responded “always” to all five healthy relationship skills were considered to have met the behavioral criterion for consistent use of healthy relationship skills.

Rejection of Attitudes Supporting Dating Violence

Attitudes were assessed using the Acceptance of Couple Violence Scale (Foshee, Fothergill, & Stuart, 1992). Respondents rated their agreement (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree) with 11 statements indicating acceptance of dating violence (e.g., “A boy angry enough to hit his girlfriend must love her very much,” “There are times when violence between dating partners is OK”). In the current sample at baseline, Cronbach's alpha was .87. Because scores were skewed to the left (the modal score was 1.0, indicating complete rejection of attitudes supporting dating violence), the measure was dichotomized (yes/no for complete rejection of attitudes supporting dating violence).

Other TDV Curricula

Most Intervention and Comparison schools offered some kind of TDV curriculum during the study period. To control for those additional intervention activities, in June, 2010, schools were asked to provide the research team with a copy of their teen dating violence prevention curriculum for the 2009-2010 academic year for each grade participating in the trial. A dichotomous variable was created to represent whether participants received any TDV curriculum during the period in question (yes/no).

Analysis Plan

Power Analysis for the Primary Outcomes

Data provided by 943 students from five schools in earlier survey research (Levesque, 2007) were used to estimate the intraclass correlation (ICC) for each of the four violence outcomes. Using the ANOVA method (Murray et al., 1994), ICC estimates for all four outcomes were in the .01 range. Furthermore, based on outcomes of large-scale randomized trials assessing the efficacy of computerized TTM interventions for bullying prevention and domestic violence cessation, we estimated effect sizes in the small range (odds ratios = .60). With 20 schools and an average of 200 students per school at baseline, a study retention rate exceeding 75%, and approximately 75% of the sample exposed to risk for dating violence, power estimates for the 12-month dating violence outcomes exceed β=.80, with two-tailed tests of significance and alpha =.0125 (alpha = .05 with Bonferroni adjustment for four primary outcomes).

Outcome Analyses

All outcome variables were dichotomous. Mixed-effects logistic regression models with a random intercept for school compared outcomes among Intervention vs. Comparison participants in the analysis sample. Unadjusted models were examined first, and then adjusted models were examined to control for potential confounds and covariates, including variables that predicted non-response at follow-up and additional variables that predicted the primary outcomes (gender, number of dating partners during follow-up, and dating violence attitudes). Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were reported. Odds ratios for the treatment effect represent the Intervention group's odds of experiencing a given outcome divided by the Comparisons group's odds. An odds ratio of 1.00 indicates no effect for the intervention. A value <1.00 indicates that the Intervention group had reduced odds of the outcome relative to Comparison, and value >1.00 indicates that the Intervention group had increased odds of the outcome.

For each of the four 12-month violence outcomes, moderator analyses were conducted. Group x past-year history of that type of violence (yes/no), group x gender (female/male), group by race/ethnicity (white/nonwhite), group x grade in school (9/10/11), and group x stage of change (Action or Maintenance/pre-Action) interaction effects were examined to determine whether intervention effects were moderated by those important participant characteristics. Where significant interaction effects were found, analyses examined the effect of the intervention within subgroups.

Results

Dating Violence

Results, presented in Table 2, show that the Teen Choices intervention was associated with significantly reduced odds of all four types of dating violence: emotional victimization, emotional perpetration, physical victimization, and physical perpetration, with unadjusted odd ratios ranging from .50 to .72 at 6 months, and from .50 to .70 at 12 months. While the rates of dating violence increased in both groups from 6 to 12 month follow-up, the odds ratios remained relatively stable, suggesting the stability of the intervention effects.

Table 2.

Study Outcomes at 6 and 12 Months Follow-Up Among Intervention and Comparison Participants

| Outcomes | Teen Choices % | Comparison % | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) Adjusted^ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 Months Follow-Up | (n=1,267) | (n=1,136) | ||||

| Violence Outcomes | ||||||

| Emotional Victimization | 43.2% | 58.1% | 0.55 (0.46 - 0.66) | **** | 0.48 (0.39 - 0.60) | **** |

| Emotional Perpetration | 30.9% | 47.1% | 0.50 (0.39 - 0.65) | **** | 0.43 (0.34 - 0.55) | **** |

| Physical Victimization | 18.0% | 23.2% | 0.72 (0.59 - 0.89) | ** | 0.70 (0.55 - 0.88) | ** |

| Physical Perpetration | 9.8% | 15.4% | 0.60 (0.47 - 0.76) | **** | 0.58 (0.44 - 0.77) | *** |

| Skills And Attitudes Outcomes | ||||||

| Consistent Skill Use | 41.7% | 20.9% | 2.70 (2.06 - 3.53) | **** | 2.60 (1.93 - 3.50) | ****^^ |

| Rejection of Dating Violence Attitudes | 54.1% | 47.4% | 1.29 (1.01 - 1.65) | * | 1.28 (1.02 - 1.60) | * |

| 12 Months Follow-Up | (n=1,389) | (n=1,216) | ||||

| Violence Outcomes | ||||||

| Emotional Victimization | 59.3% | 74.3% | 0.50 (0.41 - 0.62) | **** | 0.45 (0.36 - 0.56) | **** |

| Emotional Perpetration | 44.4% | 59.8% | 0.53 (0.43 - 0.67) | **** | 0.47 (0.38 - 0.58) | **** |

| Physical Victimization | 30.7% | 38.7% | 0.70 (0.57 - 0.84) | *** | 0.63 (0.51 - 0.78) | **** |

| Physical Perpetration | 17.3% | 25.2% | 0.62 (0.51 - 0.75) | **** | 0.57 (0.46 - 0.71) | **** |

| Skills And Attitudes Outcomes | ||||||

| Consistent Skill Use | 38.3% | 29.5% | 1.50 (1.15 - 1.96) | ** | 1.68 (1.32 - 2.14) | ****^^ |

| Rejection of Dating Violence Attitudes | 57.0% | 53.5% | 1.15 (0.94 - 1.41) | 1.13 (0.95 - 1.35) | ||

Adjusted for gender, race/ethnicity, SES, grade in school at baseline, sexual orientation at baseline, dating status at baseline, past year history of specific violence at baseline, stage of change for using healthy relationship skills at baseline, dating violence attitudes at baseline, number of dating partners during follow-up, and dating violence curriculum during follow-up

Also adjusted for current dating status

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

p<.0001

Results remained significant after adjusting for potential confounds and covariates, with adjusted odds ratios of ranging from .43 to .70 at 6 months, and from .45 to .63 at final follow-up (see Table 2). Variables reliably (p<.05) associated with reduced odds of all four types of violence at final follow-up include being in the Action or Maintenance stage for using healthy relationship skills at baseline and rejecting dating violence attitudes at baseline; variables reliably associated with increased odds of all four types of violence include having a past-year history of that type of violence at baseline and dating during follow-up. Regarding the latter finding, each additional dating partner introduced additional risk of dating violence—especially emotional and physical victimization—during follow-up. Compared to participants who did not date during follow-up, those having 1, 2, or 3 or more partners had 7.58, 14.13, and 17.21 times the odds, respectively, of experiencing emotional victimization during follow-up, and 3.85, 5.85, and 11.38 times the odds of experiencing physical victimization (all p<.0001).

Consistent Use of Healthy Relationship Skills

Teen Choices was associated with significantly higher odds of consistently using healthy relationship skills at 6 and 12 months. Results remained significant after adjusting for potential confounds and covariates. (See Table 2). In the adjusted logistic regression analyses, current dating status at the time of the follow-up assessment was included as a covariate, as current daters and nondaters completed different versions of the measure (daters reported on skill use in their dating relationships, and nondaters on skill use in their relationships with other people their age).

Rejection of Attitudes Supporting Dating Violence

Teen Choices was associated with significantly higher odds of rejecting attitudes supporting dating violence attitudes at 6 months follow-up. However, the effects were small and were not statistically significant at 12 months follow-up (see Table 2).

Moderator Analyses

Moderator analyses found significant group x past-year history interaction effects for three of the four 12-month dating violence outcomes: emotional victimization (F(1,2583) = 6.93, p=<.01), emotional perpetration (F(1,2583) = 14.41, p=<.001), and physical victimization (F(1,2583) = 6.79, p<.01), but not for physical perpetration (F(1,2583) = 2.09, ns). Results of subgroup analyses for all four violence outcomes are presented in Table 3. In general, unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios show that, for each outcome, participants with a past-year history of that type of dating violence benefited more from the intervention than participants without a past-year history. There were no significant group x gender, group x race/ethnicity, group x grade, or group x stage of change interaction effects for the 12 month outcomes.

Table 3.

Subgroup Analyses: 12-Month Dating Violence Outcomes among Intervention and Comparison Group Participants With and Without a Past Year History of Each Type of Violence

| Type of Abuse | Subgroup | Teen Choices % | Comparison % | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) Adjusteda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Victimizationb | |||||||

| Past Year History1 | 65.6% | 82.9% | 0.39 (0.31 - 0.49) | **** | 0.33 (0.25 - 0.43) | **** | |

| No History2 | 46.5% | 58.1% | 0.63 (0.46 - 0.86) | ** | 0.63 (0.47 - 0.85) | ** | |

| Emotional Perpetrationb | |||||||

| Past Year History3 | 54.3% | 76.3% | 0.37 (0.29 - 0.46) | **** | 0.31 (0.24 - 0.41) | **** | |

| No History4 | 31.2% | 39.6% | 0.69 (0.52 - 0.92) | * | 0.72 (0.54 - 0.95) | * | |

| Physical Victimizationb | |||||||

| Past Year History5 | 44.7% | 62.3% | 0.49 (0.36 - 0.65) | **** | 0.51 (0.36 - 0.72) | *** | |

| No History6 | 23.0% | 27.7% | 0.78 (0.62 - 0.97) | * | 0.72 (0.56 - 0.92) | ** | |

| Physical Perpetration | |||||||

| Past Year History7 | 35.8% | 55.3% | 0.45 (0.30 - 0.67) | **** | 0.37 (0.22 - 0.63) | *** | |

| No History8 | 13.1% | 19.4% | 0.63 (0.50 - 0.79) | **** | 0.62 (0.48 - 0.81) | *** | |

Adjusted for gender, race/ethnicity, SES, grade in school at baseline, sexual orientation at baseline, dating status at baseline, stage of change for using healthy relationship skills at baseline, dating violence attitudes at baseline, number of dating partners during follow-up, and dating violence curriculum during follow-up

Significant group × past year history interaction at 12 months follow-up

Teen Choices n =935, Comparison n =794

Teen Choices n =454, Comparison n =422

Teen Choices n =796, Comparison n =668

Teen Choices n =593, Comparison n =548

Teen Choices n =494, Comparison n =387

Teen Choices n =895, Comparison n =829

Teen Choices n =257, Comparison n =199

Teen Choices n =1,132, Comparison n =1,017

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

p<.0001.

Discussion

A cluster-randomized trial was conducted to assess the efficacy of Teen Choices, a 3-session online program that delivers assessments and individualized guidance matched to dating history, dating violence experiences, and stage of readiness for using healthy relationship skills; for high-risk victims of dating violence experiencing fear, the program addresses readiness to keep oneself safe in relationships. For the most part, findings support the four study hypotheses. Consistent with Hypothesis #1, Teen Choices was associated with significantly reduced odds of all four types of dating violence examined: emotional victimization, emotional perpetration, physical victimization, and physical perpetration, with adjusted OR's ranging from .43 to .70 at 6 months follow-up, and .45 to .63 at 12 months. These reductions are notable in their own right, but especially so in light of the brevity and convenience of the Teen Choices intervention compared to other evidence-based teen dating violence prevention programs. It is also notable that for three of the four dating violence outcomes, intervention effects were significantly larger for individuals with a past-year history of that type of violence—that is, individuals who may already be experiencing the detrimental effects of dating violence and who are at increased risk for future violence, and thus most in need of intervention.

Consistent with Hypothesis #2, participants assigned to Intervention had significantly increased odds of consistently using healthy relationship skills at 6 and 12 months follow-up. Some readers may question whether the focus on healthy relationship skills is appropriate or adequate for prevention of victimization, as the responsibility for victimization rests with the perpetrator, and not the victim. While most high school students can certainly benefit from learning about and using healthy relationship skills, and from exposure to the program's information and activities designed to help students develop healthy images of relationships and to make healthy choices, relationships are dyadic; young people who date cannot fully anticipate or control the behavior of their dating partners. Therefore, ideally, the Teen Choices program would be administered to an entire school population, to increase the likelihood of reaching both members of dating dyads, including potential perpetrators. It is encouraging that the current findings were achieved in a study that included only 200 students per school—on average, less than 20% of each school's student body—a decision based on power analyses identifying the optimal number of clusters and participants per cluster for a given power, effect size, and budget for a cluster-randomized trial. School-wide administration of the program could also help support other school activities and curricula designed to create a school climate that encourages healthy ways of relating and is intolerant of emotional and physical dating violence. School-wide administration of Teen Choices program may be achievable. From 2000 to 2008, the ratio of students to instructional computers with Internet access improved from 5.2:1 to 2.9:1 (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2014), and that ratio will continue to improve as public schools build the infrastructure required to implement online Common Core standards testing.

Hypothesis #3, that students assigned to Intervention would have significantly increased odds of rejecting all attitudes supporting dating violence was supported at 6 months follow-up, but not at 12 months. The 12-month finding is surprising, as Teen Choices—especially for early-stage users—focuses on increasing knowledge and changing attitudes to establish the foundation and motivation for change. However, the attitudes outcome measure used here was developed for middle schools students and had a restricted range in the current sample. It may not have been particularly well suited to measuring finer gradations and forms of attitude change in a high school sample.

Consistent with Hypothesis #4, all findings—with the exception of the 12-month attitudes outcome—remained significant after adjusting for potential confounds and covariates.

It is important to note that all intervention effects were achieved without teacher involvement in delivery of the intervention content. While computerized administration, and the convenience and privacy it affords, is one of the strengths of the program, there are many ways that teachers could get involved, should they choose. For example, teachers could lead class discussions to explore and reinforce key concepts; assign activities from the Teen Choices website; ask students to write about something new they learned from their session; or administer quizzes to assess knowledge. For schools with little or no class time to dedicate to teen dating violence prevention, intervention sessions could be completed as homework assignments.

Finally, it is important to comment on variables associated with nonresponse and the dating violence outcomes in the current study, as both have important implications for teen dating violence prevention. First, only 21 participants refused to participate in a follow-up session, and another 8 started but did not complete a follow-up session (see Table 1). All other missed sessions were due to school absenteeism, school transfer, and school dropout. Rates of nonresponse in the follow-up surveys are in line with rates of absenteeism (8% daily), school transfers (14% yearly) and dropout (8%) among Rhode Island high school students (Rhode Island Department of Education, 2015). Thus, the variables associated with nonresponse in the current study—e.g., being a racial/ethnic minority, receiving subsidized lunch, being gay, lesbian, bisexual, or unsure of one's sexual orientation, having more dating partners, being in a pre-Action stage for using healthy relationship skills, having a past year history of dating violence—are probably also associated with school absenteeism, transfers, and/or dropout. This finding has two important implications for dating violence prevention: 1) victims, perpetrators, and other students at increased risk for dating violence may be less likely to be in school to receive it; 2) it is worth exploring whether teen dating violence prevention programs that improve relationship skills and reduce risk for dating violence can reduce school absenteeism and dropout.

Another finding that deserves attention is the strong relationship between number of dating partners and risk for dating violence during follow-up. Past research with young adults has found that increased length of relationship was associated with increased risk for dating violence (Gamez-Guadix, Straus, & Hershberger, 2011; Dardis, Dixon, Edwards, & Turchik, 2015). In the current study, which did not assess relationship length, each additional relationship introduced additional risk for dating violence. These data suggest that delaying dating may be an effective dating violence prevention strategy. Using a social norms approach, the Teen Choices program informs students that a majority of their peers, at any given time, are not dating. If and when they do date, it's important to make good decisions about whom to date.

Limitations

This study has several strengths, including its cluster-randomized design, large sample size, high intervention fidelity, and high retention rates at follow-up. But it has limitations as well. First, the dating violence measure assessing the primary outcomes was developed by the study authors. The measure has good internal consistency, and the adjusted analyses showing the relationship between the four types of violence and other variables that predict them suggest that the measure has good construct validity as well. However, independent research is needed to validate the measure used here, and future research evaluating the efficacy of the Teen Choices program should include independently developed measures of outcome. Second, self-report frequency-based violence measures, in general, do not take motivations or the context or consequences of the violence into account. For example, the physical perpetration measure does not take into account whether the violence was perpetrated in self-defense or caused injury.

Third, the attitudes measure used here was developed for middle schools students and had a restricted range in the current sample. Future research might use an alternative measure appropriate for a high school sample. Fourth, the study did not assess whether students were exposed to other interventions (e.g., psychotherapy for aggression) that might have had an impact on study outcomes. Fifth, the study was conducted using 20 Rhode Island high schools. It is unclear whether findings would generalize to a more culturally diverse population, or to youth in more rural or urban settings. Finally, in retrospect, it would have been worthwhile to examine the impact of the intervention on outcomes linked to emotional wellbeing or self-esteem.

Research Implications

This research provides evidence of the efficacy of an online, stage-based intervention for teen dating violence prevention. Additional research is needed to replicate and extend these findings and to address their limitations. Key questions for future research include: 1) Can the effects of Teen Choices be enhanced through school-wide implementation, thereby increasing the likelihood that both members of dating dyads will be exposed to the intervention? And 2) Can the effects of Teen Choices be enhanced through greater teacher involvement (e.g., by reinforcing key concepts?) Finally, future research might prioritize the inclusion of teens who miss school-administered sessions because of absenteeism or school dropout.

Clinical and Policy Implications

As more states in the U.S. are requiring school districts to deliver curricula for teen dating violence prevention, Teen Choices program addresses barriers to implementation of evidence-based universal programs: it is brief, administered by computer with fidelity, and highly tailored to meet the unique need of students. Furthermore, by integrating an evidence-based model of behavior change, it not only imparts information on key concepts, but facilitates the development and use of healthy relationship skills to prevent emotional and physical dating violence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

At the time this research was conducted, Deborah A. Levesque, Janet L. Johnson, and Janice M. Prochaska held stock and/or stock options in Pro-Change. Janice M. Prochaska is now a consultant for Pro-Change and Carol A. Welch is now a consultant for FieldGlobal, LLC, Mumbai, India. Andrea L. Paiva is a consultant for Pro-Change.

Footnotes

We wish to acknowledge the contributions of Patricia Castle, Ph.D., Joseph Rossi, Ph.D., and Karen Grace-Martin, Ph.D., who provided helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Deborah A. Levesque, Pro-Change Behavior Systems, Inc.

Janet L. Johnson, Pro-Change Behavior Systems, Inc.

Carol A. Welch, Pro-Change Behavior Systems, Inc.

Janice M. Prochaska, Pro-Change Behavior Systems, Inc.

Andrea L. Paiva, University of Rhode Island

Reference List

- Ball B, Tharp AT, Noonan RK, Valle LA, Hamburger ME, Rosenbluth B. Expect respect support groups: Preliminary evaluation of a dating violence prevention program for at-risk youth. Violence Against Women. 2012;18(7):746–762. doi: 10.1177/1077801212455188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Choose Respect. 2006 http://vetoviolence.cdc.gov/apps/datingmatters/respect.html.

- Connolly J, Furman W, Konarski R. The role of peers in the emergence of heterosexual romantic relationships in adolescence. Child Development. 2000;71(5):1395–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dardis CM, Dixon KJ, Edwards KM, Turchik JA. An examination of the factors related to dating violence perpetration among young men and women and associated theoretical explanations: a review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2015;16(2):136–152. doi: 10.1177/1524838013517559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers KE, Prochaska JO, Van Marter DF, Johnson JL, Prochaska JM. Transtheoretical-based bullying prevention effectiveness trials in middle schools and high schools. Educational Research. 2007;49(4):397–414. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee V, Fothergill K, Stuart J. Results from the teenage dating abuse study conducted in Githens Middle School and Southern High School. University of North Carolina; Chapel Hill, NC: 1992. Unpublished Technical Report. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Greene WF, Koch GG, Linder GF, MacDougall JE. The Safe Dates program: 1-year follow-up results. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(10):1619–1622. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.10.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Simon VA, Shaffer L, Bouchey HA. Adolescents' working models and styles for relationships with parents, friends, and romantic partners. Child Development. 2002;73(1):241–255. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamez-Guadix M, Straus MA, Hershberger SL. Childhood and adolescent victimization and perpetration of sexual coercion by male and female university students. Deviant Behavior. 2011;32:712–742. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Flay BR, Johnson CA, Hansen WB, Collins LM. Group comparability: A multiattribute utility measurement approach to the use of random assignment with small numbers of aggregated units. Evaluation Review. 1984;8(2):247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Grunbaum JA, Kann L, Kinchen S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Lowry R, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance--United States, 2003 (Abridged). Journal of School Health. 2004;74(8):307–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb06620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janis IL, Mann L. Decision making: A psychological analysis of conflict, choice, and commitment. Free Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Joint Committee on Health Education Standards . National Health Education Standards: Achieving excellence. 2 ed. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs P, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS. A meta-analysis of computer-tailored interventions for health behavior change. Preventive Medicine. 2010;51(3-4):214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque DA, Ciavatta MM, Castle PH, Prochaska JM, Prochaska JO. Evaluation of a stage-based, computer-tailored adjunct to usual care for domestic violence offenders. Psychology of Violence. 2012;2(12):368–384. doi: 10.1037/a0027501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque DA, Johnson JL, Prochaska JM. Teen Choices, an online stage-based program for healthy, nonviolent relationships: Development and feasibility trial. Journal of School Violence. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2016.1147964. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque DA, Johnson JL, Welch CA, Prochaska JM, Paiva AL. Teen Choices: A Program for Healthy, Nonviolent Relationships: Effects on peer violence. 2016 doi: 10.1037/vio0000049. Manuscript in preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque DA, Paiva AL. Assessing emotional and physical dating violence victimization and perpetration among adolescents: Measure development and validation. 2016 Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Levesque DA. A stage-based expert system for teen dating violence prevention. Final Report to the Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Grant No: R43CE000499. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Liz Claiborne, & Education Development Center . Love is not abuse: A teen dating violence prevention curriculum. 3 ed. Liz Claiborne, Inc.; New York: [Google Scholar]

- Loftus EF, Marburger W. Since the eruption of Mt. St. Helens, has anyone beaten you up? Improving the accuracy of retrospective reports with landmark events. Memory and Cognition. 1983;11(2):114–120. doi: 10.3758/bf03213465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauriello LM, Ciavatta MM, Paiva AL, Sherman KJ, Castle PH, Johnson JL, et al. Results of a multi-media multiple behavior obesity prevention program for adolescents. Preventive Medicine. 2010;51:451–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E, Tancredi DJ, McCauley HL, Decker MR, Virata MC, Anderson HA, et al. One-year follow-up of a coach-delivered dating violence prevention program: A cluster randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;45(1):108–112. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray DM, Rooney BL, Hannan PJ, Peterson AV, Ary DV, Biglan A, et al. Intraclass correlation among common measures of adolescent smoking: Estimates, correlates, and applications in smoking prevention studies. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1994;140(11):1038–1050. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Educational Statistics Number and internet access of instructional computers and rooms in public schools, by selected school characteristics: Selected years, 1995 through 2008. 2014 https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d13/tables/dt13_218.10.asp?current=yes.

- National Conference of State Legislatures Teen dating violence. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/teen-dating-violence.aspx.

- Noar SM, Benac CN, Harris MS. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(4):673–693. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew J, Miller-Day M, Shin Y, Hecht ML, Krieger JL, Graham JW. Describing teacher-student interactions: A qualitative assessment of teacher implementation of the 7th grade keepin' it REAL substance use intervention. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2013;51(1-2):43–56. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9539-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Common processes of self-change in smoking, weight control, and psychological distress. In: Shiffman S, Wills T, editors. Coping and substance abuse: A conceptual framework. Academic Press; New York: 1985. pp. 345–363. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51(3):390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhode Island Department of Education InfoWorks! Rhode Island education data reporting. 2015 http://infoworks.ride.ri.gov/search/schools-and-districts.

- Ringwalt CL, Pankratz MM, Jackson-Newsom J, Gottfredson NC, Hansen WB, Giles SM, et al. Three-year trajectory of teachers' fidelity to a drug prevention curriculum. Prevention Science. 2010;11(1):67–76. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0150-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute I. SAS/STAT 9.3 User's Guide. Author; Cary, NC: 2011. The GLIMMIX Procedure. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JG, Raj A, Mucci LA, Hathaway JE. Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286(5):572–579. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, White JW, Holland LJ. A longitudinal perspective on dating violence among adolescent and college-age women. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(7):1104–1109. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BG, Mumford EA, Stein ND. Effectiveness of “Shifting Boundaries” teen dating violence prevention program for subgroups of middle school students. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(2 Suppl 2):S20–S26. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharp AT. Dating Matters: The next generation of teen dating violence prevention. Prevention Science. 2012;13(4):398–401. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Redding CA. Tailored communications for smoking cessation: Past successes and future directions. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006;25(1):49–57. doi: 10.1080/09595230500459511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz AN, Black BM. Evaluating a sexual assault and dating violence prevention program for urban youths. Social Work Research. 2001;25(2):89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Mccree DH, Harrington K, Davies SL. Dating violence and the sexual health of black adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2001;107(5):e72. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.5.e72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Crooks C, Jaffe P, Chiodo D, Hughes R, Ellis W, et al. A school-based program to prevent adolescent dating violence: A cluster-randomized trial. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(8):692–699. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Scott K, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Wekerle C, Grasley C, Straatman AL. Development and validation of the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13(2):277–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Wekerle C, Scott K, Straatman AL, Grasley C, Reitzel-Jaffe D. Dating violence prevention with at-risk youth: A controlled outcome evaluation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(2):279–291. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.