Abstract

Linoleate dioxygenase-cytochrome P450 (DOX-CYP) fusion enzymes are common in pathogenic fungi. The DOX domains form hydroperoxy metabolites of 18:2n-6, which can be transformed by the CYP domains to 1,2- or 1,4-diols, epoxy alcohols, or to allene oxides. We have characterized two novel allene oxide synthases (AOSs), namely, recombinant 8R-DOX-AOS of Coccidioides immitis (causing valley fever) and 8S-DOX-AOS of Zymoseptoria tritici (causing septoria tritici blotch of wheat). The 8R-DOX-AOS oxidized 18:2n-6 sequentially to 8R-hydroperoxy-9Z,12Z-octadecadienoic acid (8R-HPODE) and to an allene oxide, 8R(9)-epoxy-9,12Z-octadecadienoic acid, as judged from the accumulation of the α-ketol, 8S-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid. The 8S-DOX-AOS of Z. tritici transformed 18:2n-6 sequentially to 8S-HPODE and to an α-ketol, 8R-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid, likely formed by hydrolysis of 8S(9)-epoxy-9,12Z-octadecadienoic acid. The 8S-DOX-AOS oxidized [8R-2H]18:2n-6 to 8S-HPODE with retention of the 2H-label, suggesting suprafacial hydrogen abstraction and oxygenation in contrast to 8R-DOX-AOS. Both enzymes oxidized 18:1n-9 and 18:3n-3 to α-ketols, but the catalysis of the 8R- and 8S-AOS domains differed. 8R-DOX-AOS transformed 9R-HPODE to epoxy alcohols, but 8S-DOX-AOS converted 9S-HPODE to an α-ketol (9-hydroxy-10-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid) and epoxy alcohols in a ratio of ∼1:2. Whereas all fatty acid allene oxides described so far have a conjugated diene impinging on the epoxide, the allene oxides formed by 8-DOX-AOS are unconjugated.

Keywords: cyclooxygenase, cytochrome P450 74 family, 8-dioxygenase, lipidomics, lipid metabolism, oxygenation mechanism, dioxygenase, Coccidioides immitis, Zymoseptoria tritici

Eicosanoids in humans and oxylipins in plants and fungi designate oxygenated unsaturated C20 and C18 fatty acids and many of them exert potent biological actions (1–3). Fungal oxylipins can be formed by dioxygenation of C18 fatty acids by two groups of enzymes, lipoxygenases (LOXs) and heme-containing dioxygenases (DOXs) (2). The LOXs contain catalytic Fe or Mn, and oxidize unsaturated fatty acids to hydroperoxides by hydrogen abstraction at bis-allylic positions (4–8). The heme-containing DOXs belong to the cyclooxygenase (COX) gene family (9). They can oxidize fatty acids at allylic as well as bis-allylic positions due to hydrogen abstraction by a tyrosyl radical (10, 11).

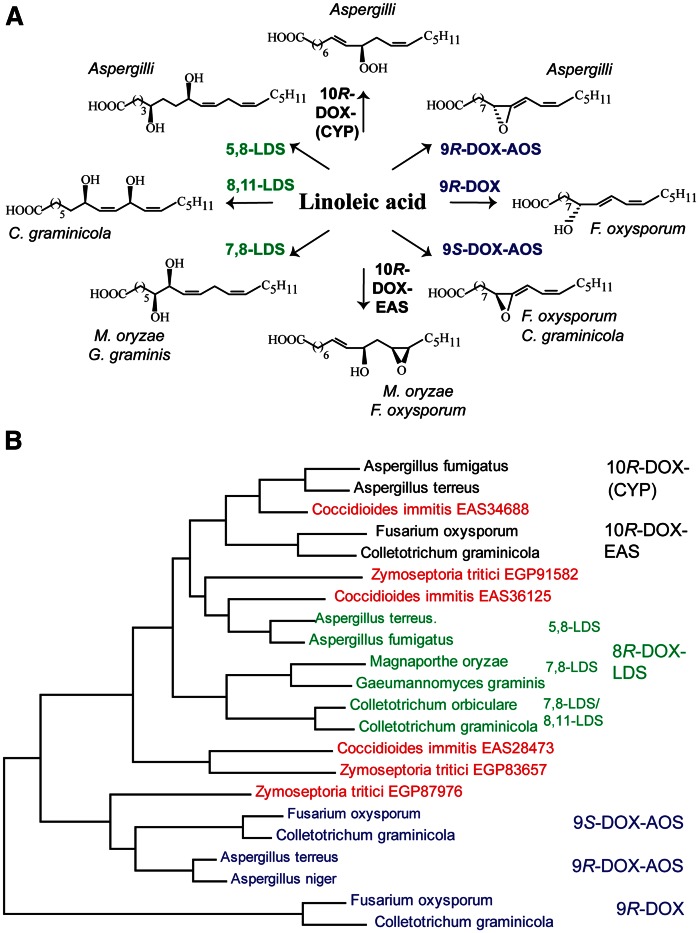

The first characterized fungal DOX related to COX was 7,8-linoleate diol synthase (LDS) (12, 13). The 7,8-LDS is a fusion protein with an 8R-DOX domain and a C-terminal cytochrome P450 (CYP) domain with the 7,8-LDS activities (14). This enzyme and the related 5,8- and 8,11-LDSs can be collectively labeled 8R-DOX-LDS for simplicity. There are now five additional characterized groups of enzymes with sequence homology to 8R-DOX-LDS. They usually align with over 60% amino acid sequence identities within each group. The transformation of 18:2n-6 by all eight enzymes is outlined in Fig. 1A. The DOX domains form 8R-, 9R-, 9S-, and 10R-hydroperoxy metabolites of 18:2n-6 and 18:3n-3 (14–17). The C-terminal CYP domains can transform these hydroperoxides by heterolytic cleavage leading to intramolecular hydroxylation at C-7, C-5, or C-11 with formation of 1,2- or 1,4-diols by 8R-DOX-LDS or epoxidation of the n-6 double bond by 10R-DOX-epoxy alcohol synthases (10R-DOX-EASs). The 9R- and 9S-hydroperoxides of 18:2n-6 can also be subject to homolytic cleavage and dehydration to allene oxides by allene oxide synthases (AOSs) (9R- and 9S-DOX-AOS) (Fig. 1A). AOSs of plants belong to the CYP74 family, but the fungal AOSs form separate CYP families (17, 18). The 8R-DOX-LDS is often expressed by mycelia in laboratory cultures of many strains, whereas other DOX-CYP may be expressed by certain strains or only in response to specific environmental stimuli (1, 19).

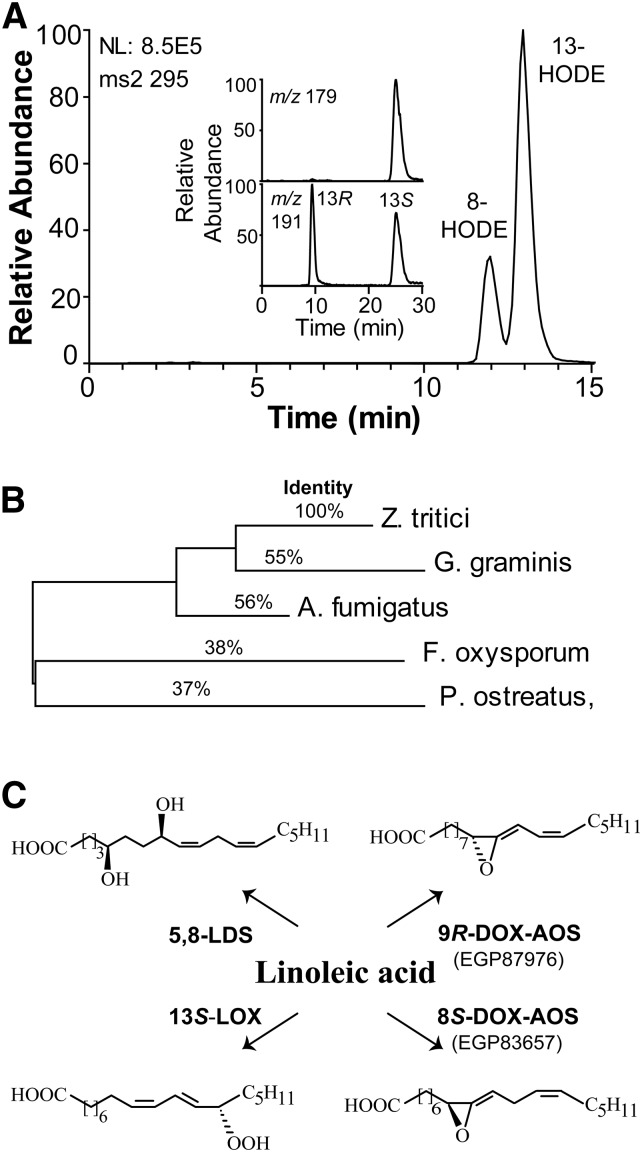

Fig. 1.

Overview of oxylipins formed by DOX-CYP and related enzymes and their sequence similarities. A: Overview of fungal oxylipins formed by DOX-CYP fusion enzymes. Linoleic acid is transformed by mycelia and/or by recombinant enzymes of subfamilies of DOX-CYP fusion to 1,2- and 1,4-diols (left, marked green), to allene oxides (right, marked blue), to an epoxy alcohol (bottom, black), and to 10R-HPODE (top, black). The parentheses in 10R-DOX-(CYP) indicate that the CYP domain is homologous to P450 but lacks the critical Cys residue for catalysis. B: Phylogenetic tree of characterized DOX-CYP fusion enzymes except for three orphans each of C. immitis and Z. tritici (marked red). The sequences are (GenBank identification numbers): EDP52540 and AFB71131 for 10R-DOX-(CYP); EGU86021 and EFQ36272 for 10R-DOX-EAS; for three subfamilies of 8R-DOX-LDS: AGA95448 and EDP50447 for 5,8-LDS, EHA52010 and Q9UUS2 for 7,8-LDS, KDN68726 and EFQ34869 for 7,8- and 8,11-LDS; EGU88194 and EFQ27323 for 9S-DOX-AOS; AGH14485 and EHA29500 for 9R-DOX-AOS; EGU79548 and EFQ36675 for 9R-DOX.

The DOX-CYP enzymes can also be classified from the position of hydrogen abstraction of linoleic acid: C-8 by 8R- and 10R-DOX and C-11 by 9-DOX (12, 15, 17). The general theme is antarafacial hydrogen abstraction and oxygen insertion in analogy with COX, but there are two exceptions: 9R-DOX and 9R-DOX-AOS (17, 18, 20).

Coccidioides immitis causes valley fever in Western USA with occasionally lethal outcomes (21). Zymoseptoria tritici (teleomorph Mycosphaerella graminicola) causes the most important disease of wheat, septoria tritici blotch (22, 23). Little is known about the DOX-CYP enzymes of these important pathogens. Fungal oxylipins may take part as secondary metabolites in sporulation, the infectious processes, and in biotrophic and necrotic growth (1, 2). It therefore seemed of interest to determine whether C. immitis and Z. tritici might code for known or unique enzymes with homology to 8R-DOX-LDS and related enzymes.

C. immitis and Z. tritici code for three DOX-CYP fusion enzymes each. These tentative proteins can be aligned with characterized DOX-CYP, as shown by the phylogenetic tree in Fig. 1B. The alignment suggests that EGP91582 and EAS36125 are likely related to 8R-DOX-LDS. EAS34688 is connected to 10R-DOX-(CYP), but EAS34688 retains the heme-thiolate cysteine in the CYP domain in contrast to 10R-DOX-(CYP) and might therefore be catalytically related to the nearby 10R-DOX-EAS subfamily (see Fig. 1B). The catalytic properties of the three remaining enzymes are more difficult to deduce.

EAS28473 and EGP83657 appear to be only distantly related to the known DOX-CYP subfamilies, but they can be aligned with 51% amino acid identity (Fig. 1B). EGP87976 aligns with both 9R- and 9S-DOX-AOS, and could be catalytically related. All three proteins have conserved the proximal and distal His heme ligands and the catalytically important Tyr residue in the DOX domains and the critical heme thiolate cysteine in the CYP domains.

We decided to express and characterize EAS28473, EGP83657, and EGP87976 for three reasons. First, they appeared to form, on sequence alignment with related enzymes, at least one separate subfamily (Fig. 1B). Second, the sequence information deduced from the DOX and CYP domains did not allow any unambiguous conclusions on their dual catalytic activities. Third, C. immitis and Z. tritici are important pathogens, and characterization of novel enzymes might provide important information for future biological studies (1, 2). Work with mycelia of C. immitis has caused fatal infections in laboratory personnel (21), but we assessed the oxidation of fatty acids by mycelia of Z. tritici.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Fatty acids were dissolved in ethanol and stored in stock solutions (35–100 mM) at −20°C. The 18:2n-6 (99%), 18:3n-6 (99%), and 18:3n-3 (99%) were from VWR, and 18:1n-9, 20:2n-6, 20:4n-6, and [13C18]18:2n-6 (98%) were from Larodan (Malmö, Sweden). The [11S-2H]18:2n-6 (>99% 2H) and [8R-2H]18:2n-6 (65% 2H) were prepared by Dr. Hamberg as described (24). The 9S-hydroperoxyoctadecatrienoic acid (HPOTrE) and 9R-, 9S-, 13R-, and 13S-hydroperoxyoctadecadienoic acids (HPODEs) were prepared by potato and tomato LOX and by 13R-MnLOX (17). The 8S-, 8R-, and 12S-HETE were from Cayman. The 18O2 (97%), RNaseA, lysozyme, DNase I, and ampicillin were from Sigma. The [13C18]8R-HPODE was prepared with the 8R-DOX domain of 7,8-LDS (14). The [18O2]8R-HPODE (>95% 18O) was prepared in the same way by incubation under 18O2. The labeled 8R-HPODE was purified by reversed-phase (RP)-HPLC. Chemically competent Escherichia coli (NEB5α) were from New England BioLabs. Champion pET101D Directional TOPO kit was from Invitrogen. Restriction enzymes and the gel extraction kit were from Fermentas. Sequencing was performed at Uppsala Genome Center (Uppsala University). The open reading frames of GenBank EAS28473 (C. immitis), EGP83657 (Z. tritici), and EGP87976 (Z. tritici) in pUC57 vectors were purchased from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). PCR primers were ordered from TIB Molbiol (Berlin, Germany). SepPak columns (silicic acid and C18 silica) were from Waters. Z. tritici IPO323 (CBS 115943) was obtained from CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre (Utrecht, The Netherlands). Z. tritici was first grown on agar plates (V8 or potato dextrose) and then transferred to 100 ml medium (1 g yeast extract and 3 g glucose per liter) with shaking at room temperature or 18°C for 10–12 days (23). Mycelia were harvested by filtration, ground to a fine powder in a mortar with liquid N2, and stored at −80°C.

Expression of recombinant proteins

The open reading frames of EAS28473, EGP83657, and EGP87976 in pUC57 were transferred to pET101D-TOPO vectors by PCR technology according to Invitrogen’s instructions. Competent E. coli (BL21 Star) cells were transformed with the expression constructs by heat shock (16). Cells were grown for 2–3 h at 37°C until they obtained an A600 of 0.2–0.8 in 2xYT medium (per liter: 16 g tryptone, 10 g yeast extract, 5 g NaCl, and 100 mg ampicillin) with shaking (220 rpm). The medium was cooled to room temperature (21°C) prior to addition of 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-D-galactopyranoside to induce protein expression. After 5 h of moderate shaking (100–130 rpm), the cells were harvested by centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 4°C; 25 min), suspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6)/5 mM EDTA/10% glycerol or 0.05 M KHPO4 (pH 7.5)/0.3 M NaCl/0.1 M KCl/1 mM GSH/0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 with lysozyme (about 0.5 mg/ml) and, in some experiments, DNase I (about 0.1 mg/ml). The suspension was frozen and thawed twice and then sonicated (Bioruptor Next Gen; 10 times (30 s sonication, 30 s pause), 4°C). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation and the supernatants were used immediately or stored at −80°C until needed. EAS28473, EGP83657, and EGP87976 were expressed in more than three independent experiments.

We confirmed that cell lysate of untransformed E. coli BL21 Star cells does not oxidize 18:2n-6 to any of the products discussed below. Analysis of cell lysates of transformed E. coli without added 18:2n-6 did not form any metabolites of this acid.

Enzyme assays

Recombinant proteins of the crude cell lysate [in 0.05 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.6)/5 mM EDTA/10% glycerol or 0.05 M KHPO4 (pH 7.5)/0.3 M NaCl/0.1 M KCl/1 mM GSH/0.1% (v/v) Tween-20] were incubated with 50–100 μM fatty acids or 30–100 μM hydroperoxides for 40 min on ice; in trapping experiments the hydroperoxides were only incubated for 1 min. The reactions (0.3–0.5 ml) were terminated with 10 ml water and the metabolites were immediately extracted on octadecyl silica (SepPak/C18). The latter was washed with water and retained metabolites were eluted with ethyl acetate (4 ml). After being evaporated to dryness under N2, the residue was dissolved in ethanol (50–100 μl), and 10 μl were subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis.

Nitrogen powder of mycelia of Z. tritici was homogenized in 0.1 M KHPO4 buffer (pH 7.3)/2 mM EDTA/0.04% (v/v) Tween-20. The supernatant, after centrifugation at 16,200 g (10 min, 4°C) was incubated with 100 μM fatty acids for 30 min on ice. The products were extracted as above.

LC-MS analysis

RP-HPLC with MS/MS analysis was performed with a Surveyor MS pump (ThermoFisher) and an octadecyl silica column (5 μm; 2 × 150 mm; Phenomenex), which was eluted at 0.3–0.4 ml/min with methanol/water/acetic acid, 750/250/0.05. The effluent was subject to electrospray ionization in a linear ion trap mass spectrometer (LTQ, ThermoFisher). The heated transfer capillary was set at 315°C, the ion isolation width at 1.5 amu (5 amu for analysis of 2H-labeled metabolites and hydroperoxides), the collision energy at 35 (arbitrary scale), and the tube lens at about −110 V. PGF1α was infused for tuning. Samples were injected manually (Rheodyne 7510) or by an autosampler (Surveyor Autosampler Plus; ThermoFisher).

Normal-phase (NP)-HPLC with MS/MS analysis was performed with a silicic acid column (5 μm Reprosil; 2 × 250 mm; Dr. Maisch) using hexane/isopropyl alcohol/acetic acid, 98/2/0.01 for separation of oxidized fatty acids (0.5 ml/min; Constametric 3200 pump, LDC/MiltonRoy). The effluent was combined with isopropyl alcohol/water (3/2; 0.25 ml/min) from a second pump (Surveyor MS pump). The combined effluents were introduced by electrospray ionization into the ion trap mass spectrometer above.

Chiral-phase (CP)-HPLC analysis of 8- and 9-HPODE was performed by chromatography on Reprosil Chiral-NR (8 μm; 2 × 250 mm; Dr. Maisch), which was eluted at 0.5 ml/min with hexane/isopropyl alcohol/acetic acid, 98.8/1.2/0.01 (25), and isomers of 8-HODE were resolved on Chiralcel OBH (26). Isomers of HETE and 9- and 13-HODE were resolved on Reprosil Chiral-AM (5 μm; 2 × 250 mm; Dr. Maisch), eluted (0.2 ml/min) with hexane/methanol/acetic acid, 96/4/0.02 or 95/5/0.02. The effluents of the CP-HPLC columns were mixed with isopropyl alcohol/water in a ratio of 2:1 and electro sprayed into the mass spectrometer.

Triphenylphosphine (TPP) in hexane was used to reduce hydroperoxy fatty acids to hydroxy fatty acids. NaBH4 or NaB2H4 in methanol (1 mg/ml on ice; 1 h) were routinely used to reduce ketones to alcohols (27). For rapid reduction of the 18O-labeled α-ketol, we added the 1 min incubation to distilled water (4°C; 1 h) with NaBH4 (1 M final concentration; 1 h) and reduced foaming by low speed centrifugations. Hydrogenation was performed in ethanol with Pd/C and a gentle stream of H2 for 2 min and the catalyst was then removed by filtration.

Bioinformatics

The ClustalW algorithm was used for sequence alignments (Lasergene, DNASTAR, Inc.). The MEGA6 software was used for construction of phylogenetic trees with 200 bootstrap tests of the resulting nodes (28).

RESULTS

Catalytic properties of EAS28473 (8R-DOX-AOS) of C. immitis

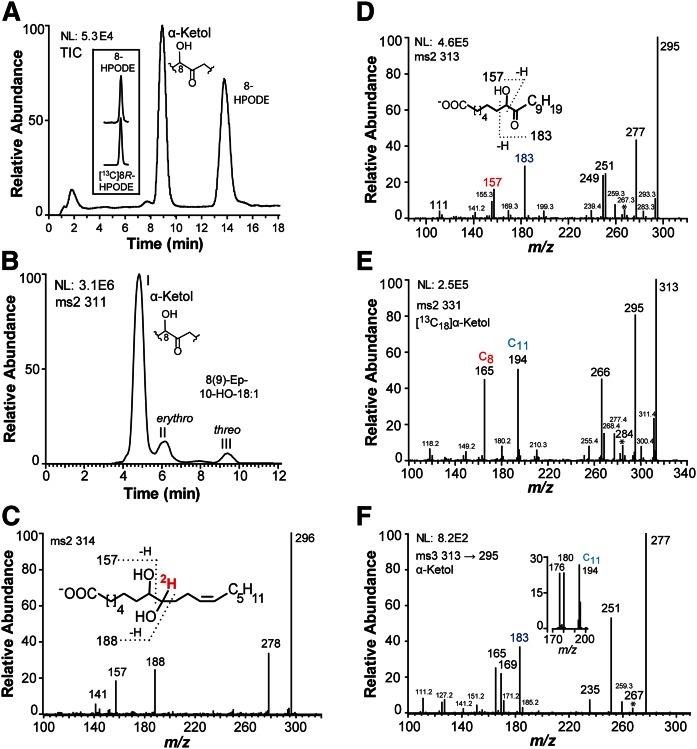

Recombinant EAS28473 oxidized 18:1n-9, 18:2n-6, and 18:3n-3 to 8-hydroperoxy metabolites with MS3 spectra as reported (29, 30). The MS2 spectra of the corresponding alcohols showed the strong and characteristic signal at m/z 157 [−OOC-(CH2)6-CHO]. The RP-HPLC-MS/MS analysis of the oxidation of 18:2n-6 is shown in Fig. 2A. Steric analysis by CP-HPLC-MS/MS analysis (Reprosil Chiral-NR) showed that 8-HPODE had the same retention time as authentic [13C18]8R-HPODE (inset in Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

RP- and NP-HPLC-MS/MS analysis of oxylipins formed from 18:2n-6 and 18:1n-9 by recombinant EAS28473 (8R-DOX-EAS). A: RP-HPLC-MS/MS analysis of products formed from 18:2n-6 by EAS28473 with major metabolites as indicated. The inset shows that 8-HPODE has the same retention time as [13C18]8R-HPODE on CP-HPLC (Reprosil Chiral-NR). B: NP-HPLC-MS/MS analysis of products with a molecular mass of 311 (after reduction of hydroperoxides to alcohols with TPP). The products in peaks II and III yielded the same MS2 spectra as reported for 8(9)-epoxy-10-hydroxy-12Z-octadecenoic acid (labeled 8(9)-ep-10-HO-18:1) (31). C: MS/MS spectrum of the 8,9-diol formed from the α-ketol (8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid) after reduction with NaBH4. This yielded two isomers (erythro and threo) of [9-2H]8,9-DiHODE with identical mass spectra. D: MS/MS spectrum of the α-ketol (8-hydroxy-9-oxo-octadecanoic acid) formed by oxidation of 18:1n-9 by EAS28473. E: MS/MS spectrum of [13C18]8-hydroxy-9-oxo-octadecanoic acid (obtained by hydrogenation of [13C18]8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid). F: MS3 spectrum of 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-octadecanoic acid (obtained by hydrogenation of 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid). The inset shows ions in the MS3 spectrum of [13C18]8-hydroxy-9-oxo-octadecanoic acid between m/z 170 and 200. The number of carbon atoms of some fragment ions is marked Csubscript. The ions at m/z 267, 284 (267+17), and 267, which are formed by loss of 46 (CO+water), 29 (13CO), and 28 (CO) from the carboxylate anions in (D), (E), and (F), respectively, are marked *.

The 8R-hydroperoxides of 18:1n-9, 18:2n-6 and 18:3n-3 were further transformed to α-ketols. The 18:2n-6 was oxidized to 8R-HPODE and an α-ketol, which was identified below as 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid (Fig. 2A). NP-HPLC-MS/MS analysis showed that small amounts of erythro and threo 8(9)-epoxy-10-hydroxy-12Z-octadecenoic acids could also be detected (Fig. 2B). The MS2 spectra (m/z 311→full scan) of these epoxy alcohols showed intense signals at m/z 157 [−OOC-(CH2)6-CHO] and m/z 187 [−OOC-(CH2)6-CHOH-CHO] as described (31).

The structure of the α-ketols formed from 18:2n-6 were confirmed by reduction of the ketone to a hydroxyl group, hydrogenation of the 12Z double bond, comparison with the mass spectra of the [13C18]-labeled α-ketol (27), and with the mass spectra of the α-ketol formed from 18:1n-9.

Treatment of 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid with NaB2H4 yielded threo and erythro [9-2H]8,9-dihydroxy-12Z-octadecenoic acid (8,9-DiHODE). Their MS2 spectra (m/z 314→full scan) were identical with strong signals at m/z 157 [−OOC-(CH2)6-CHO] and m/z 188 [−OOC-(CH2)6-CHOH-C2HO] (Fig. 2C).

The 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-octadecanoic acid, which was formed by hydrogenation of 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid, and the α-ketol formed by oxidation of 18:1n-9 by recombinant EAS28473 yielded identical mass spectra (Fig. 2D). The MS2 spectrum (m/z 313→full scan) of 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-octadecanoic acid showed mid-range signals, among other things, at m/z 183 [possibly HC(O)-C(O−)=CH-C8H17], m/z 157 [−OOC-(CH2)6-CHO], and m/z 155 (183-28; loss of CO), which supports the proposed fragmentation between C-7 and C-8, and in the upper range at m/z 295 (313-18), m/z 277 (313-2 × 18), m/z 267 (313-18-28; loss of water and CO), m/z 251 (313-44-18), and m/z 249, 239, and 199. Reduction of 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-octadecanoic acid with NaB2H4 yielded the expected signals at m/z 157 [−OOC-(CH2)6-CHO] and m/z 188 [−OOC-(CH2)6-CHOH-C2HO]. The MS2 spectrum (m/z 331→full scan) of [13C18]8-hydroxy-9-oxo-octadecanoic acid is shown in Fig. 2E. This compound was obtained by hydrogenation of the α-ketol formed from [13C18]18:2n-6. The fragmentation was consistent with the deduced structure, with signals at m/z 165 (157+9) and m/z 194 (183+11) as indicated in the figure.

The MS3 spectrum (m/z 313→295→full scan) of 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-octadecanoic acid (Fig. 2F) showed signals at m/z 277 (295-18), m/z 267 (295-28; loss of CO), m/z 251 (295-44), and in the lower range m/z 183, 169, and 165. The MS3 spectrum of the [13C18]8-hydroxy-9-oxo-octadecanoic acid showed that the corresponding ions in the lower mass range at m/z 194, 180, and 176 (inset in Fig. 2F). We conclude that 18:1n-9 and 18:2n-6 are sequentially oxidized at C-8 to hydroperoxides and dehydrated to unstable allene oxides, which are hydrolyzed to α-ketols with 8-hydroxy-9-oxo configurations.

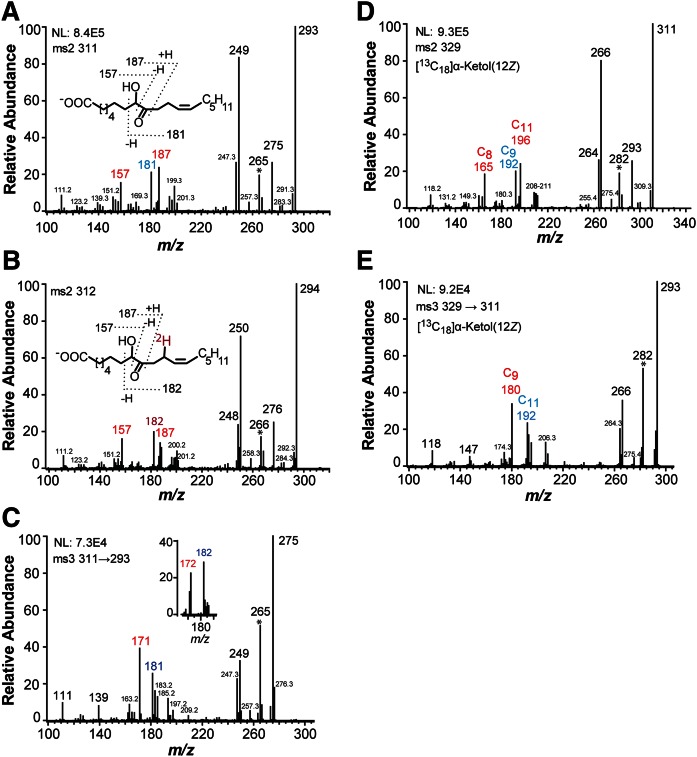

MS/MS and MS3 analysis of unsaturated α-ketols formed by 8R-DOX-AOS

The MS/MS spectra of unsaturated α-ketols, which are formed from 9-hydroperoxy fatty acids, show only weak informative signals, whereas their MS3 spectra are more characteristic (27). We therefore investigated the MS/MS and MS3 spectra of α-ketols derived from 8-hydroperoxy fatty acids.

The MS analyses of 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic and [13C18]8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acids are summarized in Fig. 3. The MS2 spectrum of 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid (m/z 311→full scan) showed important signals at m/z 157 [−OOC-(CH2)6-CHO], m/z 181 [possibly HC(O)-C(O−)=CH-C8H15], and m/z 187 [−OOC-(CH2)6-CHOH-CHO] as indicated by the inset in Fig. 3A. A characteristic signal of α-ketols was also noted at m/z 265 (A−-46; likely loss of CO and water) and m/z 181. The MS2 spectrum (m/z 312→full scan) of [11S-2H]8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid showed that a strong signal at m/z 182 (181+1) (Fig. 3B), which supported the fragmentation. In addition, we used MS3 and MS4 spectra to confirm the origin of the signal at m/z 181. The MS3 (m/z 311→181→full scan) and MS4 spectra (m/z 311→293→181→full scan) of 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid yielded strong signals at m/z 163 (35%; 181-18) and m/z 153 (base peak, 100%; 181-28; loss of CO). These results were consistent with cleavage between C-7 and C-8 with formation of m/z 181 [possibly HC(O)-C(O−)=CH-C8H15] (inset in Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

MS/MS and MS3 spectra of the α-ketol (8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid) formed from 18:2n-6 and [13C18]18:2n-6 by recombinant EAS28473 (8R-DOX-AOS). A: MS/MS spectrum of 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid. B: MS/MS spectrum of the monodeuterated α-ketol, [11S-2H]8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid. C: MS3 spectrum of 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid. D: MS3 spectrum of [13C18]8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid. E: MS3 spectrum of [13C18]8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid. The number of carbon atoms of some fragment ions is marked Csubscript in (E). Important fragments are labeled in a larger font and colored. NL, intensity normalized to 100%. The ions at m/z 282 in (D) and (E), which are likely formed by loss of 47 (13CO+water) and 29 (13CO), respectively, are marked *.

Some signals were likely formed by rearrangement mechanisms, e.g., m/z 199 (Fig. 3A). The MS3 spectrum (m/z 311→199→full scan) yielded m/z 181 (35%; 199-18), m/z 155 (100%; 199-44), and m/z 137 (40%; 155-18) as the major fragment ions.

MS3 spectra of α-ketols often contain strong and characteristic signals and can be useful complements to the MS/MS spectra, although the complex MS3 fragmentation is difficult to interpret. The MS3 spectrum of 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid (m/z 311→293→full scan) showed prominent signals at m/z 265 (293-28), m/z 181, and m/z 171 (Fig. 3C), whereas the corresponding spectrum (m/z 311→293→full scan) of [11S-2H]8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid yielded many signals increased by one mass unit, notably in the lower mass range at m/z 182 (181+1) and m/z 172 (171+1) (inset in Fig. 3C).

We finally recorded the MS/MS and MS3 spectra of the [13C18]8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid for comparison with these spectra of the unlabeled compound. The MS2 spectrum (m/z 329→full scan) of [13C18]8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid showed signals, among other things, at m/z 165 (see 157+8), m/z 196 (see 187+9), m/z 192 (see 181+11), and weak signals at m/z 208–211 of equal intensities (Fig. 3D). The MS3 spectrum (m/z 329→311→full scan) of the [13C18]8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid showed strong signals, among other things, at m/z 282 (311-29; loss of 13CO), m/z 192, and m/z 180, which likely contained 17, 11, and 9 carbon atoms (Fig. 3E). This confirmed the proposed fragmentation.

The 8R-DOX-AOS differs from 9R-DOX-AOS of Aspergilli by transforming 18:3n-3 via 8R-HPOTrE to an allene oxide/α-ketol (Fig. 4A). The structure of the α-ketol was confirmed by LC-MS analysis before and after hydrogenation.

Fig. 4.

NP-HPLC-MS/MS analysis of oxylipins formed from 18:3n-3 by EAS28473 (8R-DOX-AOS). A: NP-HPLC-MS/MS analysis. The top chromatogram shows elution of 8-HPOTrE and the bottom chromatogram shows elution of the α-ketol, 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z,15Z-octadecadienoic acid. B: MS/MS spectrum of 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z,15Z-octadecadienoic acid. C: MS3 spectrum of 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z,15Z-octadecadienoic acid. The ions at m/z 263, which are formed by loss of 46 (CO+water) and 28 (CO) in (B) and (C), respectively, are marked *. NL, intensity normalized to 100%.

The MS2 spectrum (m/z 309→full scan) of the α-ketol with two double bonds, 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z,15Z-octadecadienoic acid, showed signals, among other things, at m/z 157, 179, and 197 (see inset in Fig. 4B). The fragmentation ion at m/z 179 was supported by the MS3 spectrum (m/z 309→291→179→full scan; data not shown), which yielded m/z 161 (179-18) and m/z 151 (179-28; loss of CO) in analogy with the corresponding ion at m/z 181 in the MS/MS spectrum of 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid discussed above (see Fig. 3A). The signal at m/z 197 might be due to rearrangement. The MS4 spectrum (m/z 309→291→197→full scan) yielded m/z 179 (197-18) and m/z 153 (197-44) as the main ions.

The MS3 spectrum (m/z 309→291→full scan) of the α-ketol showed signals, which were not present in the MS/MS spectrum, e.g., at m/z 193, 171, and 165. The MS4 spectrum (m/z 309→291→193→full scan; data not shown) yielded signals at m/z 175 (193-18) and m/z 165 (193-28; loss of CO) (Fig. 4B), suggesting that m/z 193 and 165 could be related.

Finally, the structure of the α-ketol formed from 18:3n-3 was confirmed by LC-MS analysis after hydrogenation to 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-octadecanoic acid (see Fig. 2D).

The 18:3n-6 appeared to be a poor substrate in analogy with 8R-DOX-LDS. The 20:2n-6 was oxidized at C-11, but transformation to α-ketols could not be detected. The product specificity suggested that recombinant EAS28473 could be named 8R-DOX-AOS with 18:1n-9, 18:2n-6, and 18:3n-3 as likely natural substrates.

Oxidation of arachidonic acid by 8R-DOX-AOS of C. immitis

C. immitis is a human pathogen and we therefore also assessed the oxidation of 20:4n-6 by 8R-DOX-AOS. The metabolites were reduced with TPP and analyzed by NP- and CP-HPLC-MS/MS (supplemental Fig. S1A, B). The three main products were identified as 8-, 10-, and 12-HETE from their MS2 spectra (m/z 419→full scan), which were as reported previously (32). Steric analysis showed that both 12-HETE and 8-HETE mainly consisted of the S stereoisomers, as judged from reanalysis with added authentic 12S-HETE and 8R-HETE. The minor product, 10-HETE, eluted on CP-HPLC mainly as a single isomer (95%), but the stereo configuration was not further investigated.

Catalytic properties of recombinant EGP83657 (8S-DOX-AOS) of Z. tritici

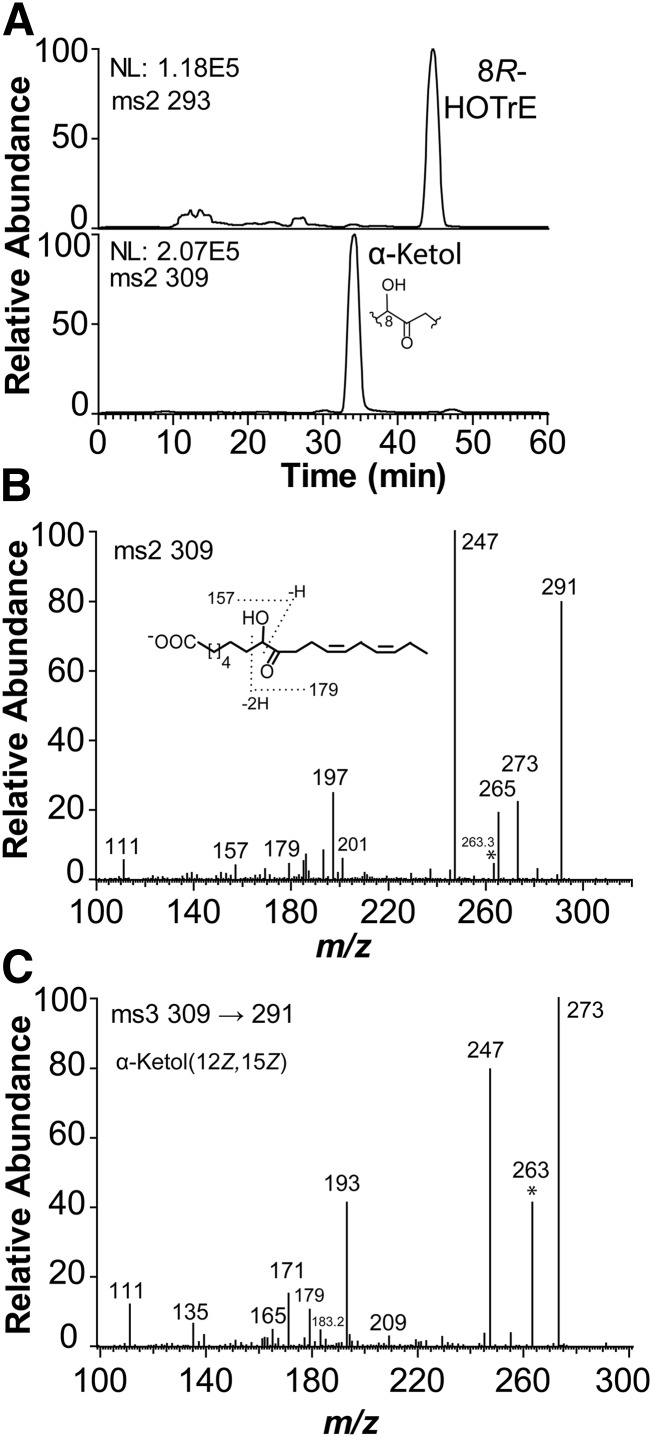

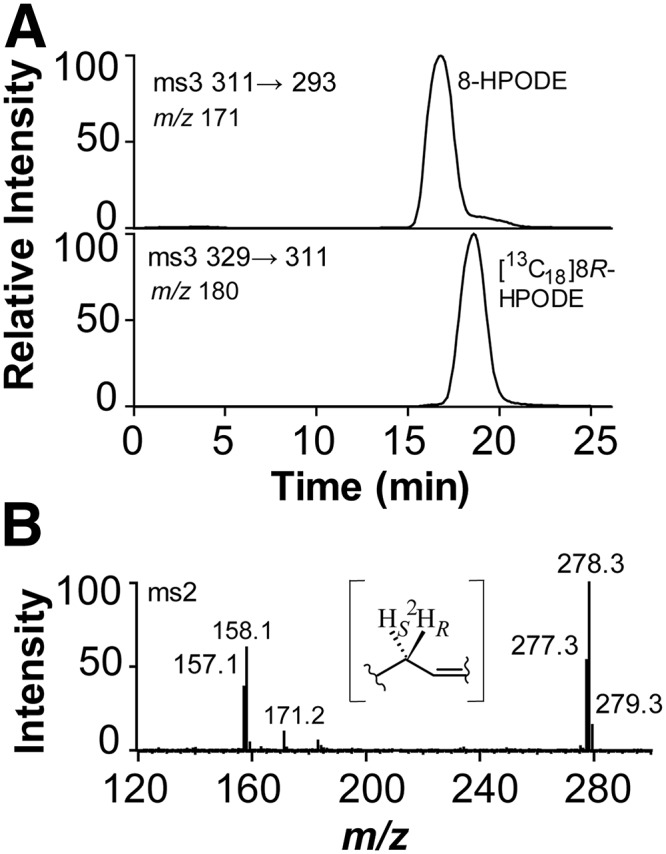

EGP83657 oxidized 18:1n-9, 18:2n-6, and 18:3n-3 to 8-hydroperoxy metabolites and to α-ketols in analogy with 8R-DOX-AOS, but with an important difference. Steric analysis of 8-HPODE showed that it mainly consisted of the S stereoisomer (Fig. 5A), which apparently was sequentially converted to 8S(9)-epoxy-9,12Z-octadecadienoic acid [8S(9)-EODE] and then hydrolyzed to an α-ketol.

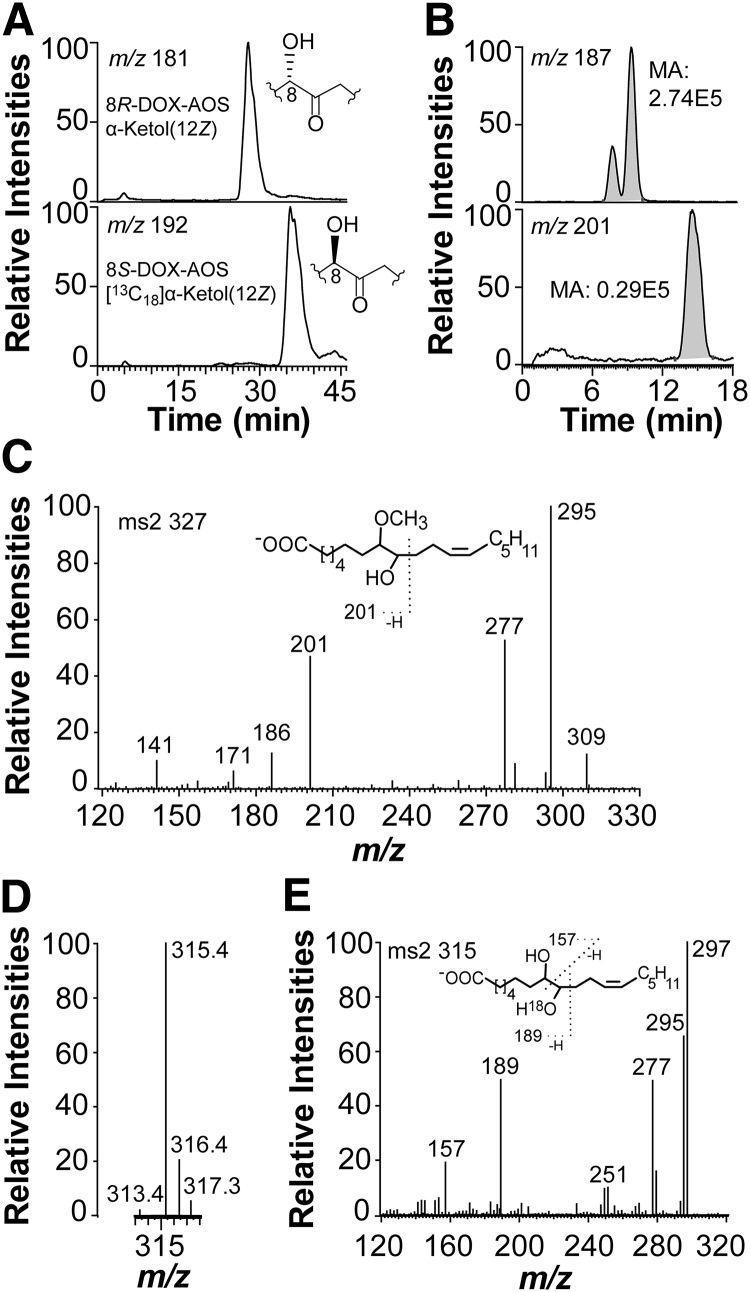

Fig. 5.

Steric analysis of 8-HPODE formed by EGP83657 (8S-DOX-AOS) and the retention of deuterium during oxidation of [8R-2H]18:2n-6 to 8S-HPODE. A: The 8-HPODE formed by EGP83657 eluted before [13C18]8R-HPODE on the CP-HPLC column and it was thus identified as the 8S stereoisomer. B: MS/MS spectrum (m/z 293–297→full scan) of 8-HODE formed from [8R-2H]18:2n-6 (65% 2H) (33). The even numbered fragments contain the 2H label, and the signal at m/z 158 is likely due to the fragment ion −OOC-(CH2)6-C2HO. The inset shows the labeling of hydrogens at C-8 of 18:2n-6.

The 8S-HPODE was formed from [8R-2H]18:2n-6 with retention of the deuterium label (Fig. 5B). These observations are consistent with suprafacial hydrogen abstraction and oxygen insertion, whereas 8R-DOX catalyzes antarafacial hydrogen abstraction and oxygenation as discussed above (33).

The 20:2n-6 was oxidized at C-11, but an α-ketol could not be detected. The 18:3n-6 was a poor substrate. We conclude that EGP83657 can be described as 8S-DOX-AOS with 18:1n-9, 18:2n-6, and 18:3n-3 as likely natural substrates.

Catalytic properties of recombinant EGP87976 (9R-DOX-AOS) of Z. tritici

Recombinant EGP87976 oxidized 18:2n-6 and transformed 9R-HPODE to two polar products, as judged by RP-HPLC-MS analysis (peaks I and II in supplemental Fig. S2A). The MS/MS and MS3 spectra were as reported for the γ- and α-ketols, respectively, of 9-HPODE-derived allene oxides (27). The 18:2n-6 was also oxidized to 9-HPODE, and steric analysis by CP-HPLC (Reprosil Chiral-AM) and MS2 analysis showed that 9-HPODE consisted of the 9S and 9R stereoisomers in a ratio of ∼1:3 (supplemental Fig. S2B). This underestimates the relative formation of the 9R stereoisomer as 9R-HPODE was further transformed to α- and γ-ketols as major products.

The 18:3n-3 was a poor substrate, and 9S-HPODE was transformed mainly to epoxy alcohols, but a 9-HPODE-derived α-ketol was also detected by its characteristic MS3 spectrum (27). Recombinant EGP87976 thus belongs to the group of 9R-DOX-AOS, which is found in Aspergilli (Fig. 1B).

Oxidation of fatty acids by mycelia of Z. tritici

Nitrogen powder of mycelia of Z. tritici oxidized 18:1n-9, 18:2n-6, and 18:3n-3 to hydroperoxides at C-8 and to variable amounts of 5,8-diols. Steric analysis (Chiralcel OBH) showed that 8R-HPODE stereoisomer was formed (>95%), and the 5,8-diols were identified by two characteristic fragments formed by MS/MS analysis, m/z 115 [−OOC-(CH2)-CHO] and m/z 173 [−OOC-(CH2)3-CHOH-(CH2)2-CHO]. The oxidation of 18:2n-6 to hydroperoxides by nitrogen powder of Z. tritici is shown in Fig. 6A. In addition to 8-HPODE, large amounts of 13-HPODE were also detected. Steric analysis with aid of [13C18]13-HODE showed that 13S-HPODE was the main stereoisomer (>98%; inset in supplemental Fig. S2A). The 18:3n-3 was also oxidized at C-13, but 18:1n-6 was not. The oxidation at C-13 of 18:2n-6 and 18:3n-3 was therefore likely catalyzed by 13S-LOX. We could not detect formation of α-ketols.

Fig. 6.

The 13S-LOX and 5,8-LDS activities of mycelia and an overview of fatty acid DOXs of Z. tritici. A: RP-HPLC-MS/MS analysis of hydroperoxides after reduction to alcohols. The inset shows that 13S-HODE was the main product (top) as judged from the separation of 13C-labeled 13R- and 13S-HODE (bottom). B: Phylogenetic tree of five iron LOXs. The GenBank identification numbers are (from top to bottom): EGP90986, EJT77580, EAL84806, EKX38530, and BAI99788. The phylogenetic tree was constructed with MEGA6. The percent sequence identity with EGP90986 is indicated. C: Overview of the oxidation of 18:2n-6 by mycelia (left) and by two recombinant DOX-AOSs (right) of Z. tritici.

EGP91582 aligns with 8R-DOX-LDS, and this protein is a strong candidate for the observed 5,8-LDS activities. The oxidation at C-13 of 18:2n-6 and 18:3n-3 was likely due to the only LOX of Z. tritici (GenBank identification number: EGP90986), which belongs to the family of fungal iron LOX (Fig. 6B). The 13S-LOX of Z. tritici thus has the same catalytic activity as reported for the LOX of Fusarium oxysporum and Pleurotus ostreatus (8, 34).

A summary of the oxidation of 18:2n-6 by mycelia and by 8S- and 9R-DOX-AOS is shown in Fig. 6C. The DOX-AOS activities could not be detected in mycelia and may only be expressed in response to environmental stimuli in analogy with other secondary metabolites.

Non-enzymatic hydrolysis of allene oxides

It seems likely that the α-ketols, which are derived from oxidation of 18:2n-6, are formed from nonenzymatic hydrolysis of allene oxides, 8R(9)- and 8S(9)-epoxy-10,12Z-octadecadienoic acids [8R(9)- and 8S(9)-EODE] (18). Hydrolysis of allene oxides to α-ketols occurs mainly with inversion of configuration of the hydroxyl group compared with the configuration of the precursor hydroperoxide (17, 35, 36). The two α-ketols, which are formed by hydrolysis of 8R(9)- and 8S(9)-EODE, are therefore expected to consist mainly of the 8S- and 8R-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acids, respectively.

CP-HPLC-MS/MS analysis showed that 8R(9)-EODE and [13C18]8S(9)-EODE were hydrolyzed to α-ketols with different retention times (Fig. 7A). The stereoisomer with the shortest retention time was formed by hydrolysis of 8R(9)-EODE and thus tentatively identified as the α-ketol with 8S configuration. “S before R” is also the elution order of the major α-ketols formed by hydrolysis of 9R(10)- and 9S(10)-EODE, respectively (17).

Fig. 7.

Analysis of hydrolysis products of allene oxides. A: CP-HPLC-MS/MS analysis of stereoisomers of α-ketols. The α-ketols were formed from 18:2n-6 and [13C18]18:2n-6 by 8R- and 8S-DOX-AOS, respectively. Hydrolysis of 9-HPODE-derived allene oxides is known to result in inversion of configuration at C-9 (35). The 9S-α-ketol elutes before the 9R-α-ketol on CP-HPLC (Reprosil Chiral-AM) (17). The α-ketols formed from 8R- and 8S-DOX-AOS eluted in the same order, 8S-hydroxy-9-oxo-octadecenoic before [13C18]8R-hydroxy-9-oxo-octadecenoic acid, as illustrated by the insets in the two chromatograms. B: RP-HPLC analysis of products formed by 8R-DOX-AOS after incubation for 1 min with 8R-HPODE and then terminated with methanol (30 vol; 60 min at 21°C.). The α-ketols were reduced to alcohols (NaBH4) before analysis. The top chromatogram shows separation of erythro and threo isomers of 8,9-DiHOME [monitoring of m/z 187; −OOC-(CH2)6-CHOH-CHO] and the bottom chromatogram shows elution of 8-methoxy-9-hydroxy-12Z-octadecenoic acids (monitoring of m/z 201 [187+14; −OOC-(CH2)6-CHOCH3-CHO] in a broad peak. MA, measured area as indicated in gray. C: MS/MS spectrum of 8-methoxy-9-hydroxy-12Z-octadecenoic acid. The inset demonstrates the ion at m/z 201. D: Hydrolysis of allene oxides formed from [18O2]8R-HPODE by 8R-DOX-AOS. The partial mass spectrum after reduction with NaBH4 to 8,9-DiHODE shows the intensities of the carboxylate anions with (m/z 315) and without (m/z 313) the 18O-label. E: MS/MS analysis of [18O]8,9-DiHODE. The inset shows the fragmentation.

Hydrolysis of allene oxides in an excess of methanol will form methoxy derivatives. We incubated 8R-DOX-AOS for 1 min with excess 8R-HPODE, added 30 vol of methanol and let the hydrolysis proceed for 1 h. To facilitate the analysis, we reduced the α-ketols with NaBH4. Analysis showed the presence of the expected products, 8,9-DiHOME and 8-methoxy-9-hydroxy-12Z-octadecenoic acid, in a ratio of ∼9:1 (Fig. 7B). The MS/MS spectrum (m/z 327→full scan) of the latter is shown in Fig. 7C. Signals were noted at m/z 309 (327-18), m/z 295 (327-32; loss of methanol), m/z 277 (295-18), and m/z 201 [−OOC-(CH2)6-CHOCH3-CHO], and in the lower mass range at m/z 186, 171, and 141. The MS3 spectrum (m/z 327→201→full scan) showed signals at m/z 186 (100%; 201-15, loss of ·CH3) and m/z 169 (10%; 201-32, loss of methanol), whereas MS3 spectrum (m/z 327→295→full scan) yielded intense signals at m/z 277 (100%; 295-18), m/z 171 (35%), and m/z 141 (20%). These spectra were consistent with the proposed structure. The trapping experiment indicates a short half time of the unconjugated allene oxide, 9R(10)-EODE, as about 90% was hydrolyzed by water after 1 min of incubation (Fig. 7B).

We next analyzed the transformation of [18O2]8R-HPODE by 8R-DOX-AOS to determine the incorporation of 18O into the α-ketol (8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid). The ketone at C-9 of the α-ketol can be exchanged with water and we therefore reduced the products formed after 1 min with NaBH4. LC-MS analysis of erythro and threo 8,9-DiHODE in the full scan mode showed incorporation of one molecule of 18O (Fig. 7D) and the MS2 spectrum (m/z 315→full scan) showed a signal at m/z 189, which demonstrated the 18O-label at C-9 (Fig. 7E).

Transformation of hydroperoxides by 8R- and 8S-DOX-AOS

The transformation of other hydroperoxides by 8R- and 8S-DOX-AOS may indicate their relation to other AOS of fungi. We therefore assessed whether the 8R-AOS of 8R-DOX-AOS (EAS28473) and 8S-AOS of 8S-DOX-AOS (EGP83657) could transform 9- and 13-HPODE.

The 8R-DOX-AOS efficiently transformed 9R-HPODE to an epoxy alcohol as a major product, but an α-ketol could not be detected. The epoxy alcohol was tentatively identified as threo 9R(10R)-epoxy-11-hydroxy-12Z-octadecenoic acid, as judged from NP- and RP-HPLC-MS/MS analysis (m/z 311→full scan) (31) along with small amounts of the erythro isomer (supplemental Fig. S3A). The 9S-, 13S-, and 13R-HPODE were only converted to small fractions (5–10%) of epoxy alcohols, as judged by RP-HPLC-MS/MS analysis.

The 8S-DOX-AOS (EGP83657) converted only a fraction of 8R-HPODE to 8-hydroxy-9-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid (5–10%). In contrast, about 50% of 9S-HPODE was transformed to an α-ketol, 9-hydroxy-10-oxo-12Z-octadecenoic acid, and to erythro and threo 9S(10S)-epoxy-11-hydroxy-12Z-octadecenoic acids (supplemental Fig. S3B) [see (31)]. The relative amounts of the α-ketol and the epoxy alcohols were ∼1:2. The 9S-HPOTrE was transformed in the same way. The α-ketols were identified by their characteristic MS2 and MS3 spectra (16, 27). The 9R-HPODE and 13S- and 13R-HPODE were not transformed by 8S-DOX-AOS, as only small amounts of epoxy alcohols were detected (<10%).

The transformation of 9S-HPODE by the 8S-AOS activities to an α-ketol, which originates from 9S(10)-EODE, suggests that the 8S-AOS may have evolved from 9S-AOS of 9S-DOX-AOS.

DISCUSSION

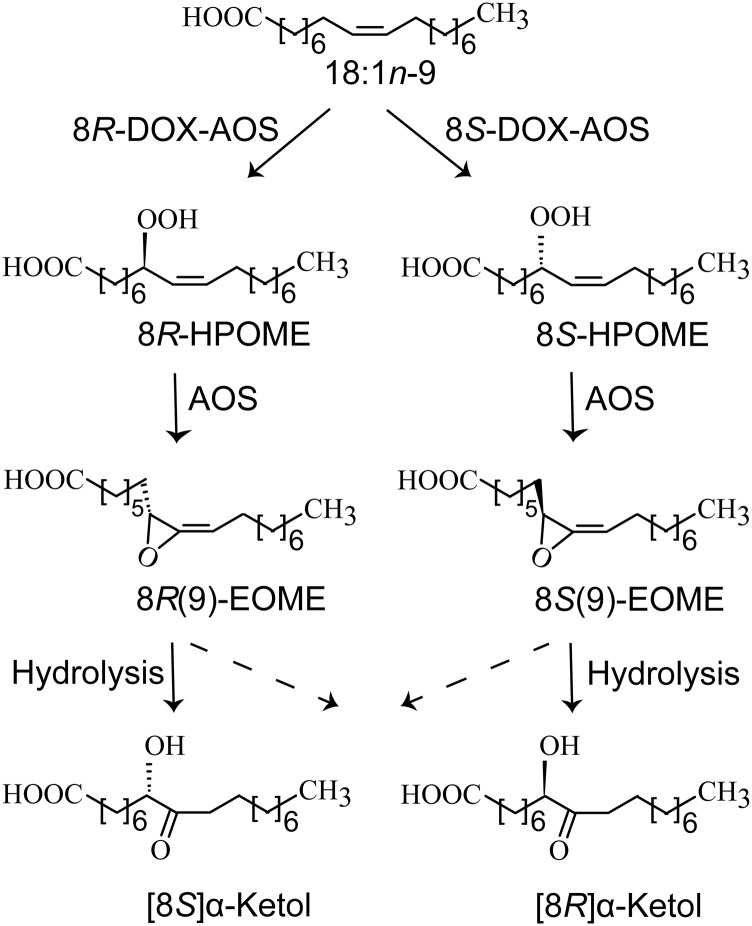

Our main goal was to investigate the catalytic properties of three putative DOX-CYP fusion enzymes of C. immitis (EAS28473) and Z. tritici (EGP83657 and EGP87976). We report that two of the recombinant enzymes form novel allene oxides and they are named 8R- and 8S-DOX-AOS, respectively, whereas the third enzyme belongs to the 9R-DOX-AOS subfamily. The sequential oxidation of 18:1n-9 by 8R- and 8S-DOX-AOS to allene oxides and hydrolysis to α-ketols are outlined in Fig. 8. We detected 5,8-LDS and 13S-LOX activities of mycelia of Z. tritici (Fig. 6C), which could be attributed to expression of EGP91582 and EGP90986, respectively.

Fig. 8.

Overview of the sequential oxidation of oleic acid to 8-hydroperoxyoctadecenoic acid (HPOME) and to allene oxides by 8R- and 8S-DOX-AOS. The two allene oxides, 8R(9)- and 8S(9)-epoxy-9-octadecamonoenoic acids (EOMEs), are mainly hydrolyzed to α-ketols by inversion of configuration at C-8 (solid arrows).

Previously described allene oxides are formed from cis-trans conjugated hydroperoxy fatty acids, e.g., from 9S- and 13S-HPOTrE by plant CYP74, 8R-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid by the AOS-LOX of the coral, Plexaura homomalla, and from 9R- and 9S-HPODE by fungal 9-DOX-AOS (37–39). The allene oxides can be transformed enzymatically or nonenzymatically to cyclopentenone fatty acids, e.g., analogs of jasmonic acid and prostaglandin A2, respectively (37–39). The process leading to a cyclopentenone from the 10Z-isomer of the 9S-HPODE-derived allene oxide was recently studied in detail (40, 41). This allene oxide undergoes homolytic cleavage with formation of a ketone at C-10, a radical at C-9, and an allyl-like radical at C-11 to C-13. This oxyallyl diradical may then form a cyclopentenone. In contrast, 8-HPODE-derived allene oxides lack conjugated double bonds, but they are nevertheless rapidly hydrolyzed by methanol or water (Fig. 7). The oxidation of 18:1n-9 to allene oxides by 8-DOX-AOS is unprecedented as this fatty acid is a poor substrate of LOXs and fungal 9R-and 9S-DOX-AOSs (17, 42).

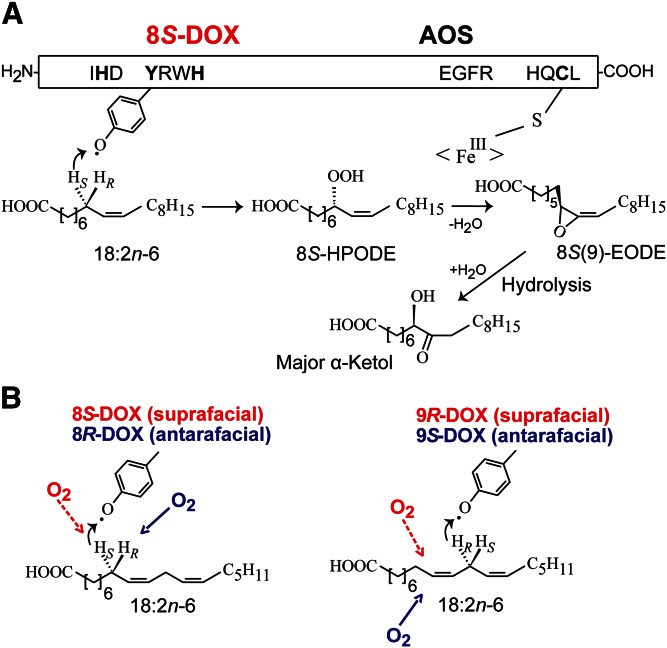

The 8R- and 8S-DOX-AOS can be aligned with 51% amino acid identity, but the four amino acids in the 8-DOX domains from the catalytic Tyr to the proximal His heme ligand are not identical. The consensus sequence TyrArgPheHis of all 9S- and 9R-DOX domains is conserved in 8R-DOX-AOS, but it is replaced in 8S-DOX-AOS with the consensus sequence TyrArgTrpHis of 8R-DOX-LDS, 10R-DOX-(CYP), and 10R-DOX-EAS. 8S-DOX-AOS is, nevertheless, the first described enzyme with a catalytic 8S-DOX domain.

The substrate recognition sites (SRSs) 4 (or I-helices) of the 8R- and 8S-AOS domains differ. The hexamer SRS 4 sequence ValAlaThrGlnAlaGln of 8R-AOS aligns except for one or two positions (in bold type) with the SRS 4 sequence ValAlaAsnGln(Ala/Gly)Gln of 5,8-LDS [see (18, 43)]. The CYP domain of 8S-DOX-AOS is catalytically related to 9S-DOX-AOS, as it transformed 9S-HPODE to an α-ketol, but this relation is not evident from SRS 4 or other sequence alignments of 8S- and 9S-AOS domains.

The general rule for oxygenation of unsaturated fatty acids by COXs, LOXs, and DOX-CYP fusion enzymes is antarafacial hydrogen abstraction and oxygen insertion. Exceptions to this rule are, for example, fungal LOXs with catalytic manganese, 9R-DOX, and 9R-DOX-AOS (6, 17, 20). The 9R- and 9S-DOX-AOSs both abstract the proR hydrogen at C-11 of 18:2n-6, but oxygen is inserted from opposite directions. An outline of the sequential biosynthesis of 8S-HPODE and 8S(9)-EODE from 18:2n-6 by 8S-DOX-AOS and the nonenzymatic hydrolysis of 8S(9)-EODE to an α-ketol is shown in Fig. 9A. Due to the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog rule, the proR hydrogen at C-11 points in the same direction as the proS hydrogen at C-8 of 18:2n-6, which is abstracted by both 8R- and 8S-DOX-AOS (Fig. 9B). The 8S-DOX-AOS thus catalyzes suprafacial hydrogen abstraction and oxygenation in analogy with 9R-DOX-AOS.

Fig. 9.

Illustration of the sequential biosynthesis of allene oxides from 18:2n-6 by 8S-DOX-EAS (EGP83657) and the suprafacial and antarafacial oxidation mechanisms of 8- and 9-DOX-AOS. A: Overview of the sequential biosynthesis of allene oxides by 8S-DOX-AOS and important amino acid residues for catalysis. B: The 8S- and 8R-DOX-AOSs abstract the proS hydrogen at C-8, whereas 9S- and 9R-DOX-AOSs abstract the proR hydrogen at C-11. The figure illustrates that these proS and proR hydrogens have the same absolute configuration relative to the 9Z,12Z-pentadiene structure. The red and blue arrows indicate the direction of oxygen insertion at C-8 and C-9, respectively, in relation to the pentadiene structure. The S and R assignments are due to the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog nomenclature rule.

Interestingly, 9R-DOX-AOS of Aspergillus niger can be transformed to 9S-DOX-AOS by replacement of two amino acids with those conserved in these two positions of 9S-DOX-AOS, Gly616Ile and Phe626Leu (17). This shifts the direction of oxygenation, but it does not change the hydrogen abstraction (see Fig. 9B). Gly616 and Phe627 were not conserved in the corresponding positions of either 8S-DOX-AOS or 8R-DOX-AOS, which both contain Leu residues in these positions.

What is the biological function of 8-DOX-AOS? C. immitis and its closely related species, Coccidioides posadasii, cause common and potentially serious human infections, which are endemic in California and Arizona (21). It was therefore of interest to determine whether 8R-DOX-AOS could metabolize arachidonic acid, as eicosanoids have potent actions in inflammation and its resolution (44). Arachidonic acid was transformed to 8S-, 10-, and 12S-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid. None of these metabolites are known to have specific biological effects (44), but it would be of interest to determine whether 8R-DOX-AOS is expressed during infection of human cells and metabolizes arachidonic acid of the host.

Z. tritici is spread worldwide, and septoria tritici blotch is often considered to be the most devastating disease of wheat (22, 23). Plants transform 13S-HPOTrE sequentially to allene oxides and to jasmonates, which act as growth and defense hormones (37, 38). The fungal AOS domains can only be aligned with plant AOSs (CYP74) and related P450 with a low degree of amino acid identity (18). Fungal AOSs and CYP74 have likely evolved independently. The parallel evolution of 8R-, 8S-, 9R-, and 9S-DOX-AOSs in fungi and CYP74 linked to LOX in plants suggest that the allene oxides may be of biological importance. This is well-established in the pathway to jasmonic acid with potent actions in plants (37, 38). Lasiodiplodia theobromae and a few other fungal pathogens overproduce jasmonic acid to induce pathological plant growth (45). Fungal jasmonates may be formed by the biochemical pathway in plants, but details are lacking (8, 46). The fungal repertoire of oxylipins likely participates in the struggle between the pathogen and its host, as well as in reproduction and development (1).

In summary, we have characterized fatty acid oxygenases of Z. tritici and report biosynthesis of two novel allene oxides formed by 8R- and 8S-DOX-AOS of C. immitis and Z. tritici. Their natural substrates are likely unsaturated C18 fatty acids, and the biological function of these secondary metabolites should be evaluated in the context of related allene oxides formed by plants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the generous help, advice, and the deuterated fatty acids provided by Dr. Hamberg, the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- AOS

- allene oxide synthase

- CP

- chiral-phase

- COX

- cyclooxygenase

- CYP

- cytochrome P450

- DiHODE

- dihydroxyoctadecadienoic acid

- DOX

- dioxygenase

- EAS

- epoxy alcohol synthase

- EODE

- epoxyoctadecadienoic acid

- HPODE

- hydroperoxyoctadecadienoic acid

- HPOTrE

- hydroperoxyoctadecatrienoic acid

- LDS

- linoleate diol synthase

- LOX

- lipoxygenase

- NP

- normal-phase

- SRS

- substrate recognition site

- RP

- reversed-phase

- TPP

- triphenylphosphine

- α-ketol

- C18 fatty acids with 8-hydroxy-9-oxo- or 9-hydroxy-10-oxo structural elements

This work was supported by Vetenskapsrådet Grant K2013-67X-06523-31-3 and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation Grant KAW 2004.0123. M.A. was supported by the Erasmus program.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains a supplement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tsitsigiannis D. I., and Keller N. P.. 2007. Oxylipins as developmental and host-fungal communication signals. Trends Microbiol. 15: 109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brodhun F., and Feussner I.. 2011. Oxylipins in fungi. FEBS J. 278: 1047–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Funk C. D. 2001. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 294: 1871–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newcomer M. E., and Brash A. R.. 2015. The structural basis for specificity in lipoxygenase catalysis. Protein Sci. 24: 298–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su C., and Oliw E. H.. 1998. Manganese lipoxygenase. Purification and characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 13072–13079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamberg M., Su C., and Oliw E.. 1998. Manganese lipoxygenase. Discovery of a bis-allylic hydroperoxide as product and intermediate in a lipoxygenase reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 13080–13088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wennman A., Magnuson A., Hamberg M., and Oliw E. H.. 2015. Manganese lipoxygenase of Fusarium oxysporum and the structural basis for biosynthesis of distinct 11-hydroperoxy stereoisomers. J. Lipid Res. 56: 1606–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brodhun F., Cristobal-Sarramian A., Zabel S., Newie J., Hamberg M., and Feussner I.. 2013. An iron 13S-lipoxygenase with an alpha-linolenic acid specific hydroperoxidase activity from Fusarium oxysporum. PLoS One. 8: e64919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hörnsten L., Su C., Osbourn A. E., Garosi P., Hellman U., Wernstedt C., and Oliw E. H.. 1999. Cloning of linoleate diol synthase reveals homology with prostaglandin H synthases. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 28219–28224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao G., Tsai A. L., Palmer G., Boyar W. C., Marshall P. J., and Kulmacz R. J.. 1997. Analysis of hydroperoxide-induced tyrosyl radicals and lipoxygenase activity in aspirin-treated human prostaglandin H synthase-2. Biochemistry. 36: 1836–1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su C., Sahlin M., and Oliw E. H.. 1998. A protein radical and ferryl intermediates are generated by linoleate diol synthase, a ferric hemeprotein with dioxygenase and hydroperoxide isomerase activities. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 20744–20751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brodowsky I. D., Hamberg M., and Oliw E. H.. 1992. A linoleic acid (8R)-dioxygenase and hydroperoxide isomerase of the fungus Gaeumannomyces graminis. Biosynthesis of (8R)-hydroxylinoleic acid and (7S,8S)-dihydroxylinoleic acid from (8R)-hydroperoxylinoleic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 267: 14738–14745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su C., and Oliw E. H.. 1996. Purification and characterization of linoleate 8-dioxygenase from the fungus Gaeumannomyces graminis as a novel hemoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 14112–14118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann I., Jernerén F., Garscha U., and Oliw E. H.. 2011. Expression of 5,8-LDS of Aspergillus fumigatus and its dioxygenase domain. A comparison with 7,8-LDS, 10-dioxygenase, and cyclooxygenase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 506: 216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann I., Jernerén F., and Oliw E. H.. 2014. Epoxy alcohol synthase of the rice blast fungus represents a novel subfamily of dioxygenase-cytochrome P450 fusion enzymes. J. Lipid Res. 55: 2113–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann I., and Oliw E. H.. 2013. Discovery of a linoleate 9S-dioxygenase and an allene oxide synthase in a fusion protein of Fusarium oxysporum. J. Lipid Res. 54: 3471–3480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sooman L., Wennman A., Hamberg M., Hoffmann I., and Oliw E. H.. 2016. Replacement of two amino acids of 9R-dioxygenase-allene oxide synthase of Aspergillus niger inverts the chirality of the hydroperoxide and the allene oxide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1861: 108–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffmann I., Jernerén F., and Oliw E. H.. 2013. Expression of fusion proteins of Aspergillus terreus reveals a novel allene oxide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 288: 11459–11469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jernerén F., Sesma A., Franceschetti M., Hamberg M., and Oliw E. H.. 2010. Gene deletion of 7,8-linoleate diol synthase of the rice blast fungus: studies on pathogenicity, stereochemistry, and oxygenation mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 5308–5316. [Erratum. 2010. J. Biol. Chem 285: 20422.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sooman L., and Oliw E. H.. 2015. Discovery of a novel linoleate dioxygenase of Fusarium oxysporum and linoleate diol dynthase of Colletotrichum graminicola. Lipids. 50: 1243–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen C., Barker B. M., Hoover S., Nix D. E., Ampel N. M., Frelinger J. A., Orbach M. J., and Galgiani J. N.. 2013. Recent advances in our understanding of the environmental, epidemiological, immunological, and clinical dimensions of coccidioidomycosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 26: 505–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Driscoll A., Kildea S., Doohan F., Spink J., and Mullins E.. 2014. The wheat-Septoria conflict: a new front opening up? Trends Plant Sci. 19: 602–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodwin S. B., M’Barek S. B., Dhillon B. , A. H. Wittenberg, C. F. Crane, J. K. Hane, A. J. Foster, T. A. Van der Lee, J. Grimwood, A. Aerts, et al. . 2011. Finished genome of the fungal wheat pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola reveals dispensome structure, chromosome plasticity, and stealth pathogenesis. PLoS Genet. 7: e1002070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamberg M. 2011. Stereochemistry of hydrogen removal during oxygenation of linoleic acid by singlet oxygen and synthesis of 11(S)-deuterium-labeled linoleic acid. Lipids. 46: 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garscha U., Nilsson T., and Oliw E. H.. 2008. Enantiomeric separation and analysis of unsaturated hydroperoxy fatty acids by chiral column chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 872: 90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garscha U., and Oliw E. H.. 2007. Steric analysis of 8-hydroxy- and 10-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids and dihydroxyoctadecadienoic acids formed from 8R-hydroperoxylinoleic acid by hydroperoxide isomerases. Anal. Biochem. 367: 238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jernerén F., Hoffmann I., and Oliw E. H. (2010) Linoleate 9R-dioxygenase and allene oxide synthase activities of Aspergillus terreus. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 495: 67–73. [Erratum. 2010. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 500: 210.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., and Kumar S.. 2013. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30: 2725–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliw E. H., Wennman A., Hoffmann I., Garscha U., Hamberg M., and Jernerén F.. 2011. Stereoselective oxidation of regioisomeric octadecenoic acids by fatty acid dioxygenases. J. Lipid Res. 52: 1995–2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oliw E. H., Su C., Skogström T., and Benthin G.. 1998. Analysis of novel hydroperoxides and other metabolites of oleic, linoleic, and linolenic acids by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry with ion trap MSn. Lipids. 33: 843–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliw E. H., Garscha U., Nilsson T., and Cristea M.. 2006. Payne rearrangement during analysis of epoxyalcohols of linoleic and alpha-linolenic acids by normal phase liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 354: 111–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bylund J., Ericsson J., and Oliw E. H.. 1998. Analysis of cytochrome P450 metabolites of arachidonic and linoleic acids by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry with ion trap MS. Anal. Biochem. 265: 55–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamberg M., Zhang L. Y., Brodowsky I. D., and Oliw E. H.. 1994. Sequential oxygenation of linoleic acid in the fungus Gaeumannomyces graminis: stereochemistry of dioxygenase and hydroperoxide isomerase reactions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 309: 77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tasaki Y., Toyama S., Kuribayashi T., and Joh T.. 2013. Molecular characterization of a lipoxygenase from the basidiomycete mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 77: 38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamberg M. 2000. New cyclopentenone fatty acids formed from linoleic and linolenic acids in potato. Lipids. 35: 353–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brash A. R. 2009. Mechanistic aspects of CYP74 allene oxide synthases and related cytochrome P450 enzymes. Phytochemistry. 70: 1522–1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gfeller A., Dubugnon L., Liechti R., and Farmer E. E.. 2010. Jasmonate biochemical pathway. Sci. Signal. 3: cm3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wasternack C., and Kombrink E.. 2010. Jasmonates: structural requirements for lipid-derived signals active in plant stress responses and development. ACS Chem. Biol. 5: 63–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song W. C., and Brash A. R.. 1991. Investigation of the allene oxide pathway in the coral Plexaura homomalla: formation of novel ketols and isomers of prostaglandin A2 from 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 290: 427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hebert S. P., Cha J. K., Brash A. R., and Schlegel H. B.. 2016. Investigation into 9(S)-HPODE-derived allene oxide to cyclopentenone cyclization mechanism via diradical oxyallyl intermediates. Org. Biomol. Chem. 14: 3544–3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brash A. R., Boeglin W. E., Stec D. F., Voehler M., Schneider C., and Cha J. K.. 2013. Isolation and characterization of two geometric allene oxide isomers synthesized from 9S-hydroperoxy-linoleic acid by P450 CYP74C3: Stereochemical assignment of natural fatty acid allene oxides. J. Biol. Chem. 288: 20797–20806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clapp C. H., Strulson M., Rodriguez P. C., Lo R., and Novak M. J.. 2006. Oxygenation of monounsaturated fatty acids by soybean lipoxygenase-1: Evidence for transient hydroperoxide formation. Biochemistry. 45: 15884–15892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoffmann I., and Oliw E. H.. 2013. 7,8- and 5,8-linoleate diol synthases support the heterolytic scission of oxygen-oxygen bonds by different amide residues. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 539: 87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haeggström J. Z., and Funk C. D.. 2011. Lipoxygenase and leukotriene pathways: biochemistry, biology, and roles in disease. Chem. Rev. 111: 5866–5898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jernerén F., Eng F., Hamberg M., and Oliw E. H.. 2012. Linolenate 9R-dioxygenase and allene oxide synthase activities of Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Lipids. 47: 65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsukada K., Takahashi K., and Nabeta K.. 2010. Biosynthesis of jasmonic acid in a plant pathogenic fungus, Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Phytochemistry. 71: 2019–2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.