In the LUX-Head & Neck 1 study, older age (≥65 years) did not adversely affect the benefit in patient-reported outcomes and antitumor activity observed with afatinib over methotrexate, which was consistent with findings from the overall population. Safety in older patients was also consistent with the overall population, favoring afatinib in terms of fewer dose reductions and discontinuations.

Keywords: afatinib, methotrexate, HNSCC, second-line, phase III, older

Abstract

Background

In the phase III LUX-Head & Neck 1 (LHN1) trial, afatinib significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) versus methotrexate in recurrent and/or metastatic (R/M) head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) patients progressing on/after platinum-based therapy. This report evaluates afatinib efficacy and safety in prespecified subgroups of patients aged ≥65 and <65 years.

Patients and methods

Patients were randomized (2:1) to 40 mg/day oral afatinib or 40 mg/m2/week intravenous methotrexate. PFS was the primary end point; overall survival (OS) was the key secondary end point. Other end points included: objective response rate (ORR), patient-reported outcomes, tumor shrinkage, and safety. Disease control rate (DCR) was also assessed.

Results

Of 483 randomized patients, 27% (83 afatinib; 45 methotrexate) were aged ≥65 years (older) and 73% (239 afatinib; 116 methotrexate) <65 years (younger) at study entry. Similar PFS benefit with afatinib versus methotrexate was observed in older {median 2.8 versus 2.3 months, hazard ratio (HR) = 0.68 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.45–1.03], P = 0.061} and younger patients [2.6 versus 1.6 months, HR = 0.79 (0.62–1.01), P = 0.052]. In older and younger patients, the median OS with afatinib versus methotrexate was 7.3 versus 6.4 months [HR = 0.84 (0.54–1.31)] and 6.7 versus 6.2 months [HR = 0.98 (0.76–1.28)]. ORRs with afatinib versus methotrexate were 10.8% versus 6.7% and 10.0% versus 5.2%; DCRs were 53.0% versus 37.8% and 47.7% versus 38.8% in older and younger patients, respectively. In both subgroups, the most frequent treatment-related adverse events were rash/acne (73%–77%) and diarrhea (70%–80%) with afatinib, and stomatitis (43%) and fatigue (31%–34%) with methotrexate. Fewer treatment-related discontinuations were observed with afatinib (each subgroup 7% versus 16%). A trend toward improved time to deterioration of global health status, pain, and swallowing with afatinib was observed in both subgroups.

Conclusions

Advancing age (≥65 years) did not adversely affect clinical outcomes or safety with afatinib versus methotrexate in second-line R/M HNSCC patients.

Clinical trial registration

NCT01345682 (ClinicalTrials.gov).

introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), including cancers of the lip, oral cavity, larynx, and pharynx, represents the seventh most common malignancy worldwide, with >650 000 cases diagnosed in 2012 [1]. Of these cases, 37% were older patients (≥65 years), 15% aged ≥75 years. These statistics are consistent with the EUROCARE-5 population-based study (1999–2007), which also reported decreased survival for head and neck cancer patients of advancing age at diagnosis (5-year relative survival: 56%, 38%, and 34% in patients aged ≤44, 65–74, and ≥75 years, respectively) [2]. There are no specific therapy guidelines for older patients with HNSCC, and treatment is often suboptimal due to poor functional status, high comorbidity burden and limited tolerability of standard therapies [3, 4]. For recurrent and/or metastatic (R/M) HNSCC patients progressing on/after first-line platinum therapy, these age-associated factors add to an already dismal prognosis and limited treatment options. Second-line treatment for R/M HNSCC primarily consists of single-agent or combination chemotherapy (e.g. methotrexate, taxanes) [5, 6]. However, older patients often do not receive these therapies due to the high risk of chemotherapy-induced toxicities, which can lead to treatment intolerance and poorer outcomes [3, 4].

Despite advancements in the development of targeted therapies as similarly efficacious and potentially less toxic options compared with chemotherapy, only one targeted therapy, the anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) monoclonal antibody, cetuximab, is approved for second-line R/M HNSCC, and only in the United States [7]. There are no published studies evaluating cetuximab in older R/M HNSCC patients, although subgroup analyses in a phase II study of cetuximab following the failure of a platinum-based therapy reported similar efficacy outcomes in patients aged <65 or ≥65 years; safety was not analyzed according to age [7]. In contrast, a phase III study of cetuximab combined with platinum-based therapy for first-line R/M disease reported reduced clinical benefit in subgroup analyses of patients aged ≥65 years [8]. In light of these limited data, there remains significant need to identify effective and manageable treatments for older HNSCC patients.

Afatinib, an oral, irreversible ErbB family blocker, binds to human EGFR 1, 2, and 4 and inhibits signaling from all ErbB family members [9]. In the phase III LUX-Head & Neck 1 (LHN1) trial, afatinib significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) and patient-reported outcomes versus methotrexate in R/M HNSCC patients progressing on/after platinum-based therapy [10]. Afatinib was associated with a predictable and manageable adverse event (AE) profile, with fewer treatment-related dose reductions, discontinuations and fatal events compared with methotrexate. This report evaluates the efficacy and safety of afatinib in prespecified age subgroups of ≥65 and <65 years in LHN1.

materials and methods

patients

Complete eligibility criteria were previously reported [10]. Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years, had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of 0/1, and histologically or cytologically confirmed squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx or larynx, which had recurred or metastasized and were not amenable for salvage surgery or radiotherapy. Patients had documented progression based on investigator assessment [Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1)] following ≥2 cycles of cisplatin or carboplatin for R/M disease; treatment with >1 systemic regimen in this setting was not allowed. Prior EGFR-targeted antibody therapy, but not EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors, was allowed.

study design

In this global, phase III, open-label trial, patients were randomized (2:1) to 40 mg/day oral afatinib or 40 mg/m2/week intravenous methotrexate, stratified by ECOG PS (0/1) and prior EGFR-targeted antibody therapy for R/M disease (yes/no). Details on dose modifications were reported [10]. Treatment continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or withdrawal.

The primary end point was PFS (independent central review); overall survival (OS) was the key secondary end point. Other end points included objective response, tumor shrinkage, patient-reported outcomes of disease symptoms and quality of life [QoL; European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) quality-of-life questionnaire C30 and its head and neck cancer-specific module], and safety; disease control was also assessed.

The study protocol, designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonization Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, and applicable region-specific regulatory requirements, was approved by Independent Ethics Committees at each center. All patients provided written informed consent.

assessments

Tumor response was assessed by investigators and independent central review (RECIST v1.1) every 6 weeks for the first 24 weeks, and every 8 weeks thereafter [10]. Safety was monitored weekly, with incidence and intensity of AEs graded according to the National Cancer Institute-Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 3.0).

statistical analysis

Complete details on statistical analyses were reported [10]. Efficacy analyses included all randomized patients (intent-to-treat population); safety analyses included all treated patients (randomized patients receiving ≥1 dose of study drug). PFS and OS were analyzed following a hierarchical testing procedure consisting of a stratified log-rank test with strata used for randomization on PFS followed by OS. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate PFS and OS, and hazard ratios (HRs) for afatinib versus methotrexate were derived using a stratified Cox proportional hazards model. Predefined age subgroups included ≥65 and <65 years; a Cox proportional hazards model was used to explore subgroup by treatment interaction. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS (version 9.2).

results

patients

Of 483 randomized patients, 128 (27%) were aged ≥65 years (afatinib, n = 83; methotrexate, n = 45), and 355 (73%) aged <65 years (afatinib, n = 239; methotrexate, n = 116) (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online), further described as ‘older’ and ‘younger’, respectively. The median (range) age was 71 (65–82) and 71 (65–88) years for patients treated with afatinib and methotrexate in the older subgroup, and 57 (32–64) and 55 (32–64) years in the younger subgroup. Approximately 15% (n = 71) of patients were aged ≥70 years (afatinib, n = 47; methotrexate, n = 24) and 7% (n = 32) aged ≥75 years (afatinib, n = 22; methotrexate, n = 10) due to small patient numbers; no further analyses were conducted in these exploratory age subgroups.

Baseline disease characteristics were generally well balanced (Table 1). A larger proportion of older patients randomized to methotrexate had an ECOG PS of 1 compared with the afatinib arm, although patient numbers in this arm were small. Compared with the younger subgroup, a larger proportion of older patients had oral cavity primary tumor site, and fewer received prior cisplatin for R/M disease. More patients in the older subgroup received prior radiotherapy with curative intent and fewer received chemoradiation. Slightly higher incidences of diabetes and hypertension were noted in older patients (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). There were no notable differences in baseline concomitant medications (data on file).

Table 1.

Patients’ demographic and baseline characteristics by age subgroup

| Characteristic | Patients aged ≥65 years |

Patients aged <65 years |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afatinib (N = 83) | Methotrexate (N = 45) | Afatinib (N = 239) | Methotrexate (N = 116) | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 68 (82) | 37 (82) | 207 (87) | 100 (86) |

| Female | 15 (18) | 8 (18) | 32 (13) | 16 (14) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Median (range) | 71 (65–82) | 71 (65–88) | 57 (32–64) | 55 (32–64) |

| Age category, n (%) | ||||

| <75 years | 61 (73) | 35 (78) | 239 (100) | 116 (100) |

| ≥75 years | 22 (27) | 10 (22) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 23 (28) | 7 (16) | 66 (28) | 35 (30) |

| 1 | 60 (72) | 38 (84) | 173 (72) | 81 (70) |

| Smoking habits, n (%)a | ||||

| Median (range) pack years | 50.0 (4.5–156.0) | 43.0 (3.7–156.0) | 40.0 (1.0–130.0) | 36.0 (0.6–225.0) |

| <10 pack years | 18 (22) | 8 (18) | 38 (16) | 23 (20) |

| ≥10 pack years | 60 (72) | 34 (76) | 195 (82) | 92 (79) |

| Unknown | 5 (6) | 3 (7) | 6 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%)a | ||||

| ≤7 units/week | 65 (78) | 40 (89) | 185 (77) | 84 (72) |

| >7 units/week | 15 (18) | 5 (11) | 43 (18) | 28 (24) |

| Unknown | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 11 (5) | 4 (3) |

| Weight loss in prior 3 months, n (%)a | ||||

| None | 59 (71) | 27 (60) | 161 (67) | 80 (69) |

| ≤5% | 12 (14) | 8 (18) | 35 (15) | 19 (16) |

| >5% and ≤10% | 6 (7) | 4 (9) | 27 (11) | 10 (9) |

| >10% | 4 (5) | 3 (7) | 5 (2) | 3 (3) |

| Unknown | 2 (2) | 3 (7) | 11 (5) | 4 (3) |

| Primary tumor site, n (%)a | ||||

| Oral cavity | 29 (35) | 17 (38) | 65 (27) | 25 (22) |

| Oropharynx | 26 (31) | 10 (22) | 73 (31) | 44 (38) |

| Hypopharynx | 12 (14) | 9 (20) | 51 (21) | 21 (18) |

| Larynx | 16 (19) | 9 (20) | 50 (21) | 26 (22) |

| Median time since first diagnosis, years (range)a | 2.3 (0.4–27.1) | 1.7 (0.6–21.7) | 1.9 (0.3–21.0) | 2.4 (0.5–18.2) |

| <2, n (%) | 37 (45) | 24 (53) | 126 (53) | 47 (41) |

| ≥2, n (%) | 46 (55) | 21 (47) | 112 (47) | 68 (59) |

| Unknown, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) | 1 (1) |

| Recurrence and metastases, n (%)a | ||||

| Recurrent only | 28 (34) | 22 (49) | 78 (33) | 39 (34) |

| Metastatic only | 10 (12) | 8 (18) | 36 (15) | 10 (9) |

| Both | 43 (52) | 15 (33) | 121 (51) | 62 (53) |

| Unknown | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 4 (2) | 5 (4) |

| p16 status,b n (%)a | ||||

| Positive | 10 (12) | 8 (18) | 21 (9) | 10 (9) |

| Negative | 25 (30) | 16 (36) | 116 (49) | 51 (44) |

| Not performed | 48 (58) | 21 (47) | 102 (43) | 55 (47) |

| Prior platinum-based therapy for R/M disease, n (%) | ||||

| Cisplatin | 35 (42) | 18 (40) | 133 (56) | 65 (56) |

| Carboplatin | 38 (46) | 17 (38) | 81 (34) | 30 (26) |

| Cisplatin and carboplatin | 8 (10) | 9 (20) | 22 (9) | 19 (16) |

| Other | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 3 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Prior use of anti-EGFR mAb for R/M disease, n (%)c | 49 (59) | 30 (67) | 140 (59) | 68 (59) |

| Prior surgery, n (%) | 62 (75) | 32 (71) | 182 (76) | 90 (78) |

| Prior curative anticancer therapy,d n (%) | ||||

| CT only | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 8 (3) | 5 (4) |

| RT only | 28 (34) | 14 (31) | 49 (21) | 23 (20) |

| CRT | 31 (37) | 14 (31) | 114 (48) | 59 (51) |

| CRT + anti-EGFR mAb | 5 (6) | 2 (4) | 20 (8) | 6 (5) |

| Other | 4 (5) | 2 (4) | 8 (3) | 2 (2) |

aPercentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

bBased on either local or central test results.

cOne patient (aged <65 years in the afatinib group) received prior panitumumab; all remaining patients received cetuximab.

dInvestigator-reported anticancer therapies with curative intent.

CRT, chemoradiation therapy; CT, chemotherapy; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; mAb, monoclonal antibody; PS, performance status; R/M, recurrent and/or metastatic; RT, radiation therapy.

treatment exposure

Median (range) treatment durations with afatinib and methotrexate were 84 (6–512) and 43 (1–337) days in older patients, and 80 (2–546) and 43 (1–442) days in younger patients. The majority of older (afatinib, 82%; methotrexate, 82%) and younger (afatinib, 86%; methotrexate, 85%) patients received ≥80% of the assigned study medication. The majority of afatinib-treated patients received the drug in tablet form (older, 80%; younger, 73%) compared with feeding tube administration (older, 13%; younger, 22%) or oral dispersion (older, 7%; younger, 5%).

efficacy

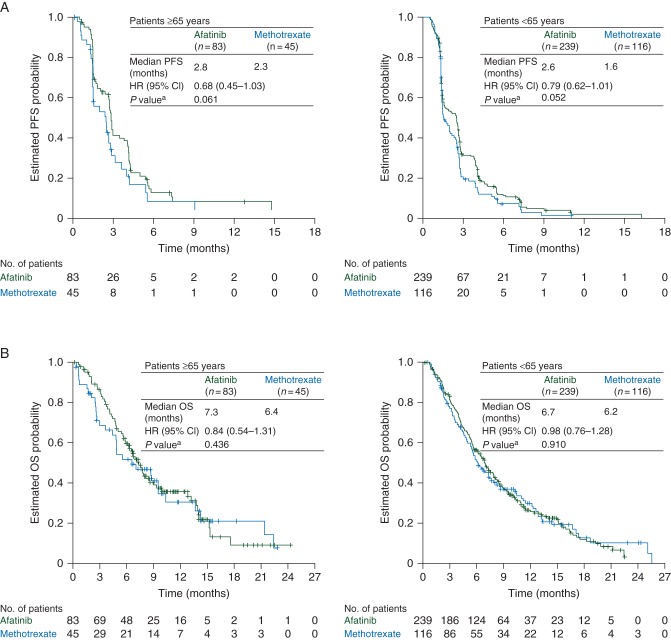

Treatment effects on survival outcomes were similar between subgroups. The median PFS with afatinib versus methotrexate was 2.8 versus 2.3 months {HR = 0.68 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.45–1.03], P = 0.061} in older patients and 2.6 versus 1.6 months [HR = 0.79 (0.62–1.01), P = 0.052] in younger patients (Figure 1A). The median OS with afatinib and methotrexate was 7.3 versus 6.4 months [HR = 0.84 (0.54–1.31), P = 0.436] in older patients and 6.7 versus 6.2 months [HR = 0.98 (0.76–1.28), P = 0.910] in younger patients (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of (A) PFS and (B) OS by age subgroup. aStratified log-rank test. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

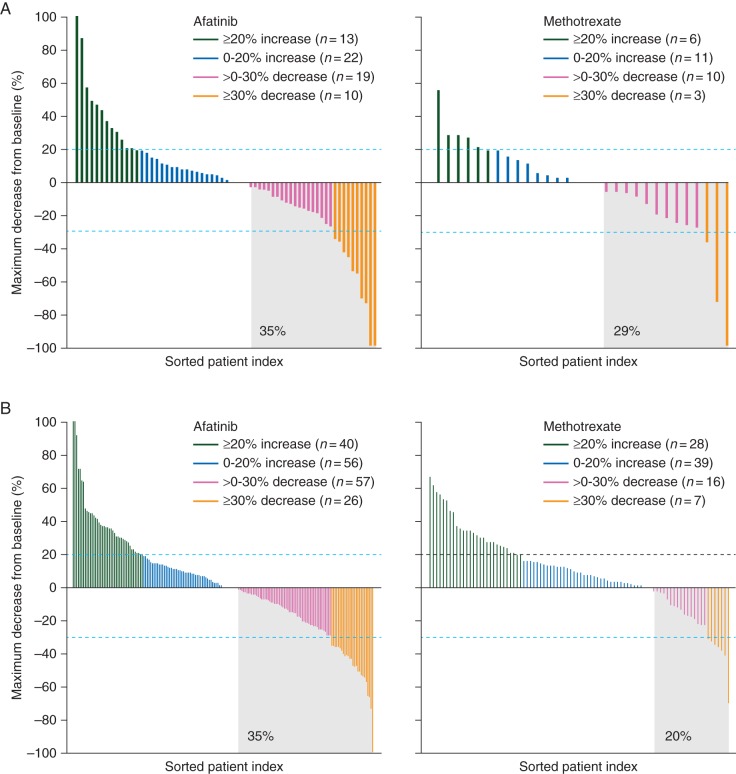

Objective response rates (ORRs) with afatinib versus methotrexate were 10.8% versus 6.7% [odds ratio (OR) = 1.7 (95% CI 0.44–6.64)] in older patients, and 10.0% versus 5.2% [OR = 2.0 (0.81–5.15)] in younger patients. Disease control rates (DCRs) with afatinib versus methotrexate were 53.0% versus 37.8% [OR = 1.9 (0.89–3.90)] in older patients and 47.7% versus 38.8% [OR = 1.4 (0.92–2.26)] in younger patients. A higher percentage of patients in each subgroup experienced tumor shrinkage from baseline with afatinib versus methotrexate, with no notable differences between the subgroups (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Waterfall plot of maximum percentage tumor shrinkage in subgroups of patients aged (A) ≥65 years and (B) <65 years.

Approximately 50% of patients in each subgroup received subsequent anticancer therapy following discontinuation of study treatment, with the majority (∼92% in each subgroup) receiving subsequent chemotherapy as monotherapy or in combination (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

safety

The safety profiles of afatinib and methotrexate were similar in older and younger patients (Table 2). Treatment-related AEs occurred in ≥85% of patients across treatment groups in each age subgroup, with grade 3/4 AEs in 32%–40% of patients (Table 2). In each subgroup, the most frequent grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs consisted of rash/acne, diarrhea, stomatitis, and fatigue with afatinib, and stomatitis and hematologic AEs (e.g. anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia) with methotrexate. There were no notable differences with either treatment between subgroups in change from baseline in body weight or ECOG PS (data on file).

Table 2.

Treatment-related AEs in ≥5% of patients (in any group) by age subgroup

| Event, n (%) | Patients aged ≥65 years |

Patients aged <65 years |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afatinib (N = 83) |

Methotrexate (N = 44) |

Afatinib (N = 237) |

Methotrexate (N = 116) | |||||

| Any AE | Any grade | Grade 3/4a | Any grade | Grade 3/4a | Any grade | Grade 3/4b | Any grade | Grade 3/4b |

| 80 (96) | 31 (37) | 39 (89) | 15 (34) | 223 (94) | 94 (40) | 98 (85) | 37 (32) | |

| Diarrhea | 66 (80) | 9 (11) | 6 (14) | 2 (5) | 165 (70) | 21 (9) | 13 (11) | 1 (1) |

| Rash/acnec | 64 (77) | 6 (7) | 4 (9) | 0 (0) | 174 (73) | 25 (11) | 9 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Stomatitisd | 40 (48) | 3 (4) | 19 (43) | 1 (2) | 85 (36) | 17 (7) | 50 (43) | 12 (10) |

| Fatiguee | 19 (23) | 7 (8) | 15 (34) | 2 (5) | 60 (25) | 11 (5) | 36 (31) | 3 (3) |

| Nausea | 14 (17) | 3 (4) | 5 (11) | 0 (0) | 50 (21) | 2 (1) | 31 (27) | 1 (1) |

| Paronychiaf | 10 (12) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 36 (15) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Dry skin | 10 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 26 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pruritus | 10 (12) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (7) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Vomiting | 9 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 32 (14) | 4 (2) | 14 (12) | 0 (0) |

| Weight decreased | 9 (11) | 1 (1) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 17 (7) | 1 (<1) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Decreased appetite | 8 (10) | 0 (0) | 5 (11) | 1 (2) | 35 (15) | 10 (4) | 16 (14) | 0 (0) |

| Epistaxis | 6 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 11 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Dyspepsia | 5 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 18 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Anemia | 5 (6) | 1 (1) | 8 (18) | 5 (11) | 17 (7) | 3 (1) | 22 (19) | 5 (4) |

| Cheilitis | 5 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Muscle spasms | 5 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Hypokalemia | 4 (5) | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 9 (4) | 5 (2) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Dysgeusia | 4 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Blood creatinine increased | 4 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Dehydration | 4 (5) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Dizziness | 4 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Conjunctivitisg | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 16 (7) | 1 (<1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Palmar-plantar erythrodysethesia | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 15 (6) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Leukopenia | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 4 (9) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (8) | 7 (6) |

| ALT increased | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (7) | 1 (2) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 12 (10) | 2 (2) |

| Neutropenia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 15 (34) | 4 (9) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 16 (14) | 7 (6) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (7) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (4) | 2 (2) |

aThere were no grade 5 drug-related AEs observed in ≥5% of patients. In the subgroup of patients aged ≥65 years, there were no patients with grade 5 AEs in the afatinib group and one patient with grade 5 renal failure and pancytopenia in the methotrexate group not included in the table.

bIn the subgroup of patients aged <65 years, there were two patients with grade 5 AEs in the afatinib group (one aspiration, one septic shock) and four patients with grade 5 AEs in the methotrexate group (one aspiration, one septic shock, one sepsis, and one general physical health deterioration) not included in the table.

cGrouped term including acne, dermatitis, dermatitis acneiform, erythema, exfoliative rash, folliculitis, rash, rash erythematous, rash macular, rash maculopapular, rash pruritic, rash pustular, skin exfoliation, skin fissures, skin lesion, skin reaction, skin toxicity, and skin ulcer.

dGrouped term including aphthous stomatitis, mucosal erosion, mucosal inflammation, mouth ulceration, and stomatitis.

eGrouped term including asthenia, chronic fatigue syndrome, fatigue, and malaise.

fGrouped term including nail bed infection and paronychia.

gGrouped term including conjunctivitis.

AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

Incidences of treatment-related serious AEs were similar for afatinib and methotrexate in older (10% and 9%) and younger (15% and 12%) patients. In both subgroups, afatinib was associated with fewer treatment-related dose reductions (older, 36% versus 43%; younger, 31% versus 41%) and discontinuations (older, 7% versus 16%; younger, 7% versus 16%). There were no deaths related to afatinib and one related to methotrexate in older patients; fewer treatment-related deaths were observed with afatinib [n = 2 (1%)] compared with methotrexate [n = 4 (3%)] in younger patients.

patient-reported outcomes

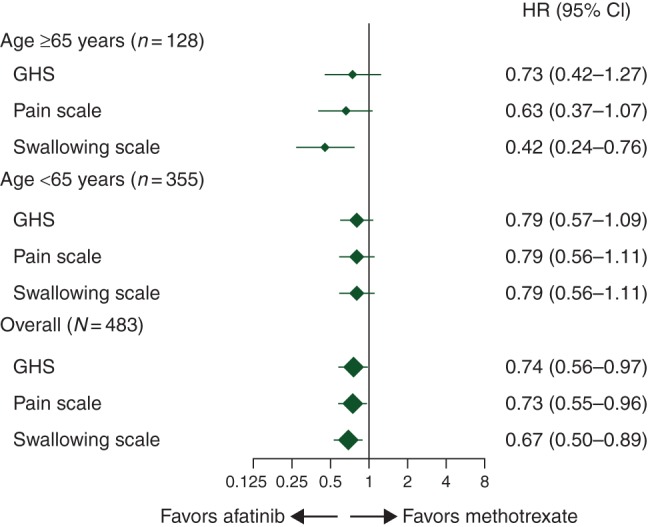

In the older and younger subgroups, respectively, ≥90% and ≥95% completed EORTC QoL questionnaires at baseline, and ≥65% and ≥71% across treatment groups completed questionnaires at assessment time points during the first 24 weeks of treatment. There were no notable differences in baseline questionnaire scores between subgroups (data on file). A trend toward improved time to deterioration in global health status and pain was observed with afatinib versus methotrexate in both subgroups; a significant benefit with afatinib was observed for time to deterioration in swallowing in older patients (Figure 3). A significant improvement in change in pain over time (P = 0.015) was observed with afatinib versus methotrexate in older patients (data on file).

Figure 3.

Time to deterioration of patient-reported outcomesa by age subgroup. aAssessed using EORTC questionnaire QLQ-C30 and QLQ-H&N35 for pain (composite of items 31–34) and swallowing (composite of items 35–38). CI, confidence interval; EORTC, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; GHS, global health status; HR, hazard ratio; QLQ-C30, quality-of-life questionnaire C30; QLQ-H&N35, quality-of-life questionnaire head and neck cancer-specific module.

discussion

The PFS benefit with afatinib over methotrexate was similarly present in R/M HNSCC patients aged ≥65 or <65 years, and was associated with a trend toward improvement in some disease-related symptoms. Although patient numbers in the older subgroup were smaller than the overall population and younger subgroup (particularly the methotrexate arm due to the 2:1 randomization scheme), and the study was not powered for formal statistical comparison of predefined subgroups, there is no indication that the benefit observed with afatinib would be adversely affected by advancing age. Median OS, percentage of patients with tumor shrinkage, ORR, and DCR were also numerically higher with afatinib versus methotrexate in both subgroups, with >50% of older patients achieving disease control with afatinib. Similar to the previous phase III trials in this setting [8, 11], the 65-year age cutoff was predefined in this study, and patient numbers in exploratory subgroups aged ≥70 years were too small for meaningful analyses.

In both predefined age subgroups, afatinib was associated with a trend toward improved patient-reported time to deterioration of global health status, pain and swallowing, reflecting the improvements observed in the overall population [10]. In older patients, significant benefit with afatinib was observed for time to deterioration in swallowing and improvement in pain over time. Patient-reported outcomes were not analyzed by primary tumor site, which can impact swallowing ability. In this context, a larger proportion of older patients had oral cavity primary site, while more patients in the younger subgroup had oropharynx primary site. In the previous phase III studies of R/M HNSCC, EGFR-targeted agents have not significantly improved global health status over chemotherapy, although some improvements in disease-related symptoms were reported with first-line cetuximab plus chemotherapy; no studies evaluated QoL or disease-related symptoms specifically in older patients [11–13]. While some caution is warranted when interpreting the patient-reported outcomes data for older patients in this study due to smaller patient numbers, findings suggest that afatinib may provide some QoL benefit over methotrexate in these patients.

Treatment compliance is an important factor for clinical outcomes in older patients, as they are vulnerable to nonadherence due to health-related and socioeconomic factors (e.g. logistical complications and hospital transportation) [14]. In this study, treatment exposure with afatinib was similar in older and younger patients, and compliance rates were high with afatinib versus methotrexate in both subgroups. Further, no unexpected safety findings with afatinib were observed in older patients, with an AE profile that was predictable and manageable, and generally similar to younger patients. Of note, there were some differences in baseline prior therapies that may impact tolerability, including less intensive therapy in the curative setting in the older subgroup (i.e. more patients received radiotherapy alone and fewer received chemoradiation compared with younger patients), although no analysis of timing of curative therapy was performed, and a greater proportion of older patients receiving carboplatin over cisplatin in the first-line R/M setting compared with younger patients. Consistent with the overall study, fewer treatment-related dose reductions and discontinuations were observed with afatinib versus methotrexate in both subgroups, with no afatinib-related deaths occurring in older patients. These findings suggest that advancing age did not adversely affect the favorable safety profile of afatinib in this study.

There are some study limitations that should be considered when interpreting these findings, particularly for patients aged ≥65 years. There is no standard definition for ‘older’ or ‘elderly’; however, much of the literature defines patients aged ≥65 years as ‘older’, with subcategories of ‘young old’ (65–74 years), ‘old’ (75–85 years), and ‘oldest old’ (>85 years) [3, 4]. In this study, 25% of patients included in the ≥65 years subgroup were aged ≥75 years, categorizing the majority as ‘young old’. This is not unexpected, as patients aged ≥75 years are often underrepresented in clinical trials due to exclusion criteria preventing enrollment of patients with high comorbidity burden and poor functional status, which are routinely observed with advancing age, particularly in HNSCC patients. In this trial, patients with ECOG PS ≥2 (due to the lack of prior experience with afatinib in R/M HNSCC patients with ECOG PS >1) and/or significant comorbidities (e.g. cardiovascular abnormalities, gastrointestinal disorders) were excluded, resulting in similar functional status and baseline medical conditions between subgroups. Further, there was no formal geriatric assessment to define frailty of the patients enrolled; thus, patients in the ≥65 years subgroup are considered to be relatively fit, warranting a certain degree of caution when considering treatment of a frailer population. Despite these limitations, patients aged ≥65 years represented a substantial proportion (27%) of the total study population, with a ∼15-year difference in median age observed between subgroups. This allowed for meaningful comparison of clinical outcomes based on the age cutoff of ≥65 years, ultimately demonstrating similar treatment effects of afatinib and methotrexate in these subgroups. These findings support the concept that chronological age alone should not be a determining factor in treatment choice, and other factors including functional status, comorbidities, and frailty should be considered [4]. Ongoing trials in HNSCC patients aged ≥70 years have incorporated geriatric evaluation to define patient frailty and deliver more personalized treatment (ELAN trials) [15].

In summary, effective anticancer treatment and management of tolerability in older R/M HNSCC patients is a significant challenge. In the LHN1 study, similar outcomes with regard to efficacy and patient-reported outcomes of QoL and disease-related symptoms were observed with afatinib versus methotrexate in the second-line R/M HNSCC patients aged ≥65 and <65 years. Further, afatinib demonstrated a predictable and manageable safety profile in both subgroups.

funding

This work was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim. There is no applicable grant number for this work.

disclosure

TG has stock ownership or options in Bayer AG; has participated in advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck Serono, Novartis, and MSD; and has received honoraria from Novartis, Merck Serono, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Roche. J-PHM has participated in noncompensated advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim. RIH has participated in advisory boards for BMS, Merck, Celgene, and Bayer and corporate-sponsored research for BMS, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, and AstraZeneca. LFL has participated in advisory boards for Eisai, BMS, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Merck Serono, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Debiopharm, VentiRX, SOBI, Novartis, AstraZeneca, and Bayer. MT has participated in advisory boards for Merck Serono, Eisai, and Bayer; has participated in corporate-sponsored research for Eisai and MSD; and has received honoraria from Merck Serono, BMS, Eisai, Otsuka, and Bayer. JG has participated in advisory boards for BMS and Merck Serono, and has received research grants from BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chugai, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Merck Serono, and Sanofi. GdC Jr has participated in advisory boards and corporate-sponsored research for Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, MSD, AstraZeneca, Merck Serono, and Eurofarma; has also participated in corporate-sponsored research for BMS; and has received honoraria from Roche, MSD, AstraZeneca, Merck Serono, and Eurofarma. XJC and EE are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. JBV has participated in advisory boards for Merck Serono, Innate Pharma, Synthon Biopharmaceuticals, MSD and Vaccinogen; has received honoraria from Merck Serono and Vaccinogen; and is on the steering committee for the LUX-Head & Neck studies. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgments

We thank the patients, their families, and all of the investigators who participated in the study. We also thank Liz Svensson (Boehringer Ingelheim) for her contributions to the study. Medical writing assistance, supported financially by Boehringer Ingelheim, was provided by Katie McClendon, PhD, of GeoMed, an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare plc, during the preparation of this manuscript. The authors were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions, were involved at all stages of manuscript development, and have approved the final version.

references

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M et al. . GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0: Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. 2012.

- 2.Gatta G, Botta L, Sanchez MJ et al. . Prognoses and improvement for head and neck cancers diagnosed in Europe in early 2000s: The EUROCARE-5 population-based study. Eur J Cancer 2015; 51: 2130–2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mountzios G. Optimal management of the elderly patient with head and neck cancer: issues regarding surgery, irradiation and chemotherapy. World J Clin Oncol 2015; 6: 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarris EG, Harrington KJ, Saif MW, Syrigos KN. Multimodal treatment strategies for elderly patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 2014; 40: 465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Head and Neck Cancers, Version 1.2015. 2015. In http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck.pdf (11 March 2016, date last accessed). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Grégoire V, Lefebvre JL, Licitra L, Felip E, and on behalf of the EHNS–ESMO–ESTRO Guidelines Working Group. Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: EHNS-ESM–ESTRO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2010; 21: v184–v186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vermorken JB, Trigo J, Hitt R et al. . Open-label, uncontrolled, multicenter phase II study to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of cetuximab as a single agent in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck who failed to respond to platinum-based therapy. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 2171–2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F et al. . Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 1116–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solca F, Dahl G, Zoephel A et al. . Target binding properties and cellular activity of afatinib (BIBW 2992), an irreversible ErbB family blocker. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2012; 343: 342–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machiels JP, Haddad RI, Fayette J et al. . Afatinib versus methotrexate as second-line treatment in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck progressing on or after platinum-based therapy (LUX-Head & Neck 1): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 583–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machiels JP, Subramanian S, Ruzsa A et al. . Zalutumumab plus best supportive care versus best supportive care alone in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck after failure of platinum-based chemotherapy: an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12: 333–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart JS, Cohen EE, Licitra L et al. . Phase III study of gefitinib compared with intravenous methotrexate for recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck [corrected]. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 1864–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mesia R, Rivera F, Kawecki A et al. . Quality of life of patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab first line for recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Ann Oncol 2010; 21: 1967–1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gellad WF, Grenard JL, Marcum ZA. A systematic review of barriers to medication adherence in the elderly: looking beyond cost and regimen complexity. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2011; 9: 11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joel Guigay J, Le Caer H, Mertens C et al. . Elderly Head and Neck Cancer (ELAN) study: personalized treatment according to geriatric assessment in patients age 70 or older: first prospective trials in patients with squamous cell cancer of the head and neck (SCCHN) unsuitable for surgery. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32 (15_suppl): abstract TPS6099. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.