Eribulin is indicated in the EU for advanced/metastatic breast cancer patients following ≥1 prior chemotherapy for advanced disease, and anthracycline and taxane in adjuvant/metastatic setting. We pooled 1644 patients from two phase III trials and found that eribulin significantly increased survival versus control, particularly in some subgroups of interest like HER2- and triple-negative disease.

Keywords: metastatic breast cancer, triple-negative breast cancer, eribulin, clinical trial, survival, pooled analysis

Abstract

Background

Based on data from two multicenter, phase III clinical trials (Studies 301 and 305), eribulin (a microtubule dynamics inhibitor) is indicated in the European Union (EU) for patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer (MBC) after ≥1 prior chemotherapy for advanced disease, including an anthracycline and a taxane in either the adjuvant or metastatic setting. Data from Studies 305 and 301 were pooled to investigate the efficacy of eribulin in various subgroups of patients who matched the EU label, including those with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative and triple-negative disease.

Patients and methods

In Study 305 (NCT00388726), patients were randomized 2:1 to eribulin mesylate 1.4 mg/m2 (equivalent to eribulin 1.23 mg/m2 [expressed as free base]) intravenously on days 1 and 8 every 21 days] or treatment of physician's choice after 2–5 prior chemotherapies (≥2 for advanced disease), including an anthracycline and a taxane (in early/advanced setting). In Study 301 (NCT00337103), patients were randomized 1:1 to eribulin (as above) or capecitabine (1.25 g/m2 orally twice daily on days 1–14 every 21 days) following ≤3 prior chemotherapies (≤2 for advanced disease), including an anthracycline and a taxane. Efficacy end points were investigated in the intent-to-treat population and subgroups, pooled as discussed above.

Results

Overall, 1644 patients were included (eribulin: 946; control: 698); baseline characteristics were well matched. Overall survival was significantly longer with eribulin versus control (P < 0.01), as were progression-free survival and clinical benefit rate (both P < 0.05). Significant survival benefits with eribulin versus control were observed in a wide range of patient subgroups, including HER2-negative or triple-negative disease (all P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Our findings underline the survival benefit achieved by eribulin used according to EU label in the overall MBC population and in various subgroups of interest, including patients with HER2-negative and triple-negative disease.

introduction

Long-term survival of women with advanced or metastatic breast cancer (MBC) remains poor [1, 2] with no single accepted standard of care once initial chemotherapy has failed [2, 3]. In March 2011, the microtubule dynamics inhibitor eribulin mesylate (eribulin) was approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of MBC in women who had received two or more prior chemotherapy regimens for their disease. This approval was based on results from a phase III, open-label, randomized study (Study 305/EMBRACE), in which eribulin was compared with treatment of physician's choice (TPC) in patients with locally recurrent or MBC who had received 2–5 prior chemotherapeutic regimens (including an anthracycline and a taxane for early or advanced disease), with ≥2 chemotherapies for advanced disease [4]. In this study, the median overall survival (OS) was significantly longer with eribulin than with TPC [hazard ratio (HR) 0.81; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.67, 0.96; P = 0.014]. There was also a significant difference in favor of eribulin in progression-free survival (PFS), as assessed by the investigators (HR 0.76; 95% CI, 0.64, 0.90; P = 0.002), but not by independent review (HR 0.87; 95% CI 0.71, 1.05; P = 0.137) [4].

In July 2014, the European Union (EU) indication for eribulin was expanded to include patients with locally advanced or MBC who had received one or more prior chemotherapeutic regimens for advanced disease (including an anthracycline and a taxane in either the adjuvant or metastatic setting, unless patients were not suitable for these treatments) [5]. Support for this indication came from Study 301, which compared eribulin with capecitabine in women with locally advanced or MBC receiving study treatment as their first-, second-, or third-line therapy, having previously received an anthracycline and a taxane [6]. In this study, a significant survival benefit for eribulin over capecitabine was not demonstrated in the overall population (HR 0.88; 95% CI 0.77, 1.00; P = 0.056); however, prespecified subgroup analyses showed a longer OS for eribulin compared with capecitabine in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative disease or triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) (Twelves et al., manuscript under review).

Two potential strategies to further investigate the differences in treatment effect observed in a subgroup of interest may include the development of a new randomized clinical trial specifically in this patient subgroup or a pooled analysis of relevant clinical data—the latter approach was conducted upon a request from the EMA. Data from Studies 305 and 301 were pooled to investigate the efficacy of eribulin in various subgroups of patients, including those with HER2-negative and TNBC. This first analysis was carried out with 77% and 82% of events in Studies 305 and 301, respectively [7]. Significant improvements in OS with eribulin versus the control arm were observed in some subgroups, including HER2-negative disease (HR 0.82; 95% CI 0.72, 0.93; P = 0.002) and TNBC (HR 0.74; 95% CI 0.60, 0.92; P = 0.006).

To provide clinicians with additional evidence specific to the patient population now approved in the EU for treatment with eribulin, here we report the efficacy of eribulin in patients pooled from Studies 305 and 301 who matched the EU label. The current analysis differs from the previous pooled analysis [7] as it specifically assesses the efficacy of eribulin in the patient population defined according to the EU label, and in subgroups of interest (that were also investigated in the previous pooled analysis) based on more updated data.

patients and methods

Detailed methods for Studies 305 (NCT00388726) and 301 (NCT00337103) have been published previously [4, 6]. Briefly, in the open-label, randomized Study 305, patients were randomized 2:1 to eribulin mesylate 1.4 mg/m2 (equivalent to eribulin 1.23 mg/m2 [expressed as free base]) intravenously on days 1 and 8 every 21 days] or TPC (defined as any single-agent chemotherapy or hormonal or biological treatment; radiotherapy; or symptomatic treatment alone) after 2–5 prior chemotherapies, of which ≥2 were for locally recurrent or MBC, including an anthracycline and a taxane (for early or advanced disease) [4]. Stratification factors for randomization included HER2 status, prior exposure to capecitabine, and geographic region. OS and PFS were the primary and secondary objectives, respectively [4].

Study 301 was an open-label, randomized study of eribulin (dosed as above) compared with capecitabine (1.25 g/m2 orally twice daily on days 1–14 every 21 days; 1:1 randomization ratio) in patients who had received ≤3 prior chemotherapy regimens (with ≤2 for advanced or metastatic disease) including prior therapy with an anthracycline and a taxane for early or advanced disease [6]. Patients who had received prior capecitabine treatment were excluded. Stratification factors for randomization included HER2 status and geographic region. The coprimary end points were OS and PFS [6].

Informed consent was obtained from all patients for Studies 305 and 301, and all procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national), the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008, and guidelines of the International Conference for Harmonization of Good Clinical Practice.

statistical analyses

The main objective of this pooled analysis was to assess OS and PFS in the pooled intent-to-treat population in patients who had received ≥1 prior line of chemotherapy in the advanced or metastatic setting, including prior exposure to anthracycline and taxane, in concordance with the EU label. Data were updated for Study 305 to 17 June 2013 after 95% of death events occurred. For Study 301, data are to 12 March 2012 after 82% of death events occurred. Investigator-assessed data were used for these analyses; independent assessments were only used for imputation for number of organs involved in the case of missing values. HRs for OS were based on a Cox model, with the study, prior capecitabine use, geographic region, and HER2 status used as stratification factors (in relevant subgroup analyses). Estrogen-receptor (ER) status and number of organs involved were used as covariates, if appropriate, in the sensitivity analyses. P values were estimated using stratified log-rank tests stratified as for HR. For the subgroup analyses, patients were analyzed by HER2 status (positive, negative, or unknown), ER status (positive, negative, or unknown), presence of TNBC, number of organs involved (≤2, >2), and the presence of visceral disease. These subgroup analyses were analyzed in patients who received eribulin versus the ‘control arm’ (which comprised patients treated with the comparator drug in Studies 305 and 301), and also for eribulin versus capecitabine, specifically. Interaction analyses with treatment*study were carried out for the overall population using a Cox model that was stratified by region, prior capecitabine treatment, and HER2 status, and with treatment, study, and treatment*study as covariates. The estimate and inference were obtained within each study before pooling. Both studies were randomized and the line of treatment was balanced between the eribulin and control arms. Interaction analyses were also carried out for subgroup analyses using the Cox models stratified as above, and with treatment, subgroup, and treatment*subgroup as covariates.

results

The overall group consisted of 1644 patients who had previously received at least one prior chemotherapy regimen for advanced disease, and were included in this analysis [eribulin: n = 946; control (TPC/capecitabine): n = 698]. Of these, 1160 patients had HER2-negative disease and a total of 489 patients were randomized to treatment with capecitabine in the control arm (45 and 444 patients from Studies 305 and 301, respectively). Baseline characteristics and demographics were generally well matched between the two treatment arms (Table 1). Two hundred and twenty patients who received the study treatments as first-line therapy in Study 301 were not included in the current analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics for the patients in the pooled analysis who received eribulin according to the EU labela

| Patient characteristics | Eribulin (n = 946) | Control (n = 698) |

|---|---|---|

| Study populationb | 58% | 43% |

| Age, years | ||

| Mean (SD) | 55 (10.3) | 54 (10.2) |

| Race | ||

| Black | 32 (3.4) | 24 (3.4) |

| White | 860 (90.9) | 639 (91.5) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 20 (2.1) | 17 (2.4) |

| Other | 34 (3.6) | 18 (2.6) |

| Site of disease | ||

| Visceral | 782 (82.7) | 608 (87.1) |

| Non-visceral | 153 (16.2) | 84 (12.0) |

| Missing | 11 (1.2) | 6 (0.9) |

| Number of organs involved | ||

| ≤2 | 471 (49.8) | 324 (46.4) |

| >2 | 475 (50.2) | 374 (53.6) |

| Number of prior chemotherapy regimens | ||

| 1 | 48 (5.1) | 55 (7.9) |

| ≥2 | 896 (94.7) | 642 (92.0) |

| NA | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) |

| Number prior chemotherapy regimen for locally advanced or metastatic disease | ||

| 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 |

| 1 | 288 (30.4) | 300 (43.0) |

| ≥2 | 657 (69.5) | 397 (56.9) |

| NA | — | 1 (0.1) |

| HER2 status | ||

| Positive | 150 (15.9) | 104 (14.9) |

| Negative | 663 (70.1) | 497 (71.2) |

| Unknown | 133 (14.1) | 97 (13.9) |

| ER status | ||

| Positive | 544 (57.5) | 401 (57.4) |

| Negative | 319 (33.7) | 237 (34.0) |

| Unknown | 83 (8.8) | 60 (8.6) |

| PR status | ||

| Positive | 435 (46.0) | 320 (45.8) |

| Negative | 397 (42.0) | 288 (41.3) |

| Unknown | 114 (12.1) | 90 (12.9) |

| Triple negative | 199 (21.0) | 153 (21.9) |

Data are n (%) unless stated otherwise.

ER, estrogen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; NA, not available; PR, progesterone receptor; SD, standard deviation.

aPatients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer who had received one or more prior chemotherapeutic regimens for advanced disease (including an anthracycline and a taxane in either the adjuvant or metastatic setting, unless patients were not suitable for these treatments).

bProportion of total patients.

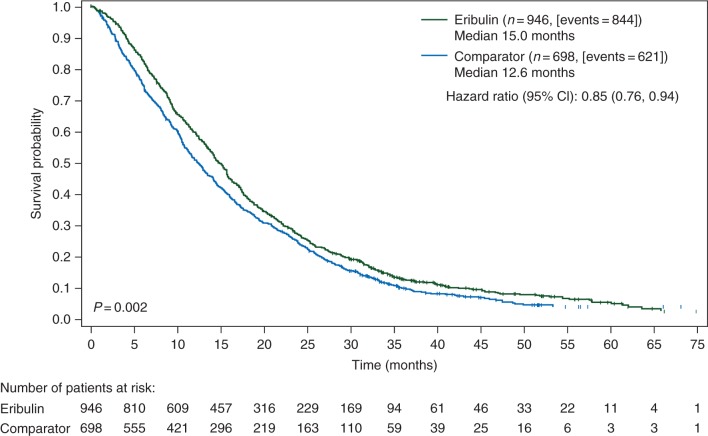

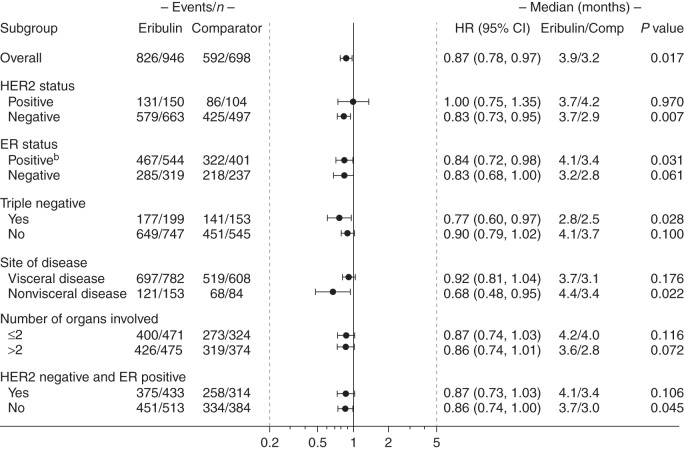

In the overall group of 1644 patients who had received ≥1 prior chemotherapy regimens for advanced disease, OS was significantly longer in the eribulin versus the control arm (HR 0.85; 95% CI 0.76, 0.94; P < 0.01; Figure 1); the median OS was 15.0 months (inter-quartile range 17.3) versus 12.6 (inter-quartile range 17.8) months, respectively. Treatment with eribulin was also associated with a significantly longer PFS compared with the control arm (HR 0.87; 95% CI 0.78, 0.97; P < 0.05; median PFS: 3.9 versus 3.2 months, respectively; Figure 2). Inclusion of a treatment*study interaction term in the model for OS or PFS confirmed lack of statistical evidence for treatment differences among Studies 305 and 301 (both P > 0.05). The objective response rate (ORR) was similar between the treatment groups, whereas clinical benefit rate was significantly higher with eribulin compared with the control (30% versus 27%, respectively; P < 0.05; supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 1.

OS curves in patients who received eribulin or the comparator drug according to the EU labela. Hazard ratio is estimated based on the Cox model with stratification factors of region, HER2 status, prior capecitabine use, and study. The median OS is adjusted by study. P value is estimated based on the stratified log-rank test. aPatients with locally advanced or MBC who had received one or more prior chemotherapeutic regimens for advanced disease (including an anthracycline and a taxane in either the adjuvant or metastatic setting, unless patients were not suitable for these treatments). CI, confidence interval; EU, European Union; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; MBC, metastatic breast cancer; OS, overall survival.

Figure 2.

PFS in patients who received eribulin according to the EU labela, based on investigator review. HR was estimated based on the Cox model without covariates, with stratification factors: study, region, HER2 status, and prior capecitabine use. For HER2 subgroup analysis, HER2 was not used as a stratification factor. P value is estimated based on the stratified log-rank test. aPatients with locally advanced or MBC who had received one or more prior chemotherapeutic regimens for advanced disease (including an anthracycline and a taxane in either the adjuvant or metastatic setting, unless patients were not suitable for these treatments). bA significant interaction between study and treatment was observed in this analysis when a treatment*study interaction term was used (P < 0.01; data not shown). CI, confidence interval; ER, estrogen receptor; EU, European Union; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR, hazard ratio; MBC, metastatic breast cancer; PFS, progression-free survival.

patient subgroups by receptor status and disease characteristics

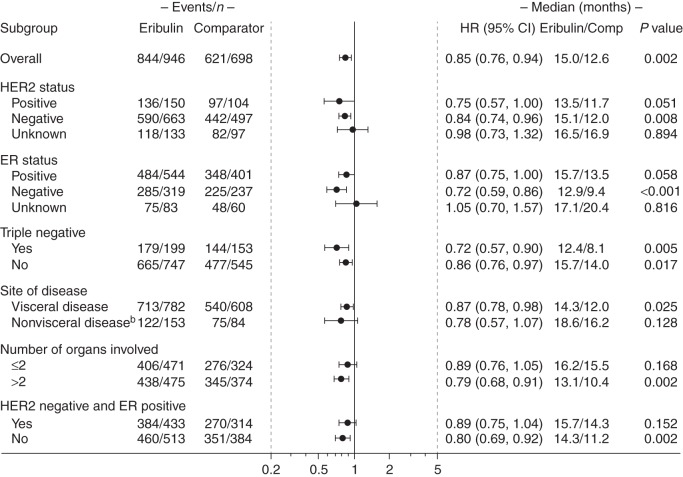

In the 1160 patients with HER2-negative disease, OS was significantly longer with eribulin compared with the control arm (HR 0.84; 95% CI 0.74, 0.96; P < 0.01; median OS: 15.1 versus 12.0 months, respectively). Significantly longer OS with eribulin versus the control arm was also observed in the 352 patients with TNBC (HR 0.72; 95% CI 0.57, 0.90; P < 0.01; median OS: 12.4 versus 8.1 months, respectively).

Significant improvements were also observed in patients with ER-negative disease (P < 0.001), those without TNBC (P < 0.05), with >2 organs involved (P < 0.05), and in patients with visceral disease (P < 0.05; Figure 3). No significant interaction between study and treatment was observed (P > 0.05), except in patients with non-visceral disease (P < 0.05; data not shown).

Figure 3.

OS in patients who received eribulin according to the EU labela. HR was estimated based on the Cox model without covariates, with stratification factors: study, region, HER2 status, and prior capecitabine use. For HER2 subgroup analysis, HER2 was not used as a stratification factor. P value is estimated based on the stratified log-rank test. aPatients with locally advanced or MBC who had received one or more prior chemotherapeutic regimens for advanced disease (including an anthracycline and a taxane in either the adjuvant or metastatic setting, unless patients were not suitable for these treatments). bA significant interaction between study and treatment was observed in this analysis (P < 0.05; data not shown). Intent-to-treat population. CI, confidence interval; ER, estrogen receptor; EU, European Union; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR, hazard ratio; MBC, metastatic breast cancer; OS, overall survival.

Eribulin significantly improved PFS compared with the control arm in patients with HER2-negative (P < 0.01), TNBC (P < 0.05), ER-positive disease (P < 0.05), and in patients with non-visceral disease (P < 0.05; Figure 2). A significant interaction between study and treatment was only observed in the patients with ER-positive disease when a treatment*study interaction term was used (P < 0.01; data not shown).

An additional analysis was conducted in patients with HER2-negative/ER-positive disease, as summarized in Figures 2 and 3 and supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online.

sensitivity analyses

A sensitivity analysis with covariates of ER status and the number of organs involved was conducted for OS in the overall population and in the subgroups. The findings were consistent with the analyses without these added covariates (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Comparative analyses were also conducted in patients who received eribulin versus capecitabine in the control arm, in the pooled patient population. Overall, eribulin significantly prolonged OS compared with capecitabine (HR 0.84; 95% CI 0.73, 0.96; P < 0.05; median OS: 15.2 versus 13.3 months, respectively). A similar benefit with eribulin compared with capecitabine was also observed in many of the subgroups analyzed, including patients with HER2-negative disease or TNBC (both P < 0.05; supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

safety

For eribulin, the median number of treatment cycles was 5 (range, 1–65 cycles), and the median duration of treatment was 3.9 months (range, 0.7–45.1 months). For the comparator arm, the median number of treatment cycles was 4 (range, 1–61 cycles), and the median duration of treatment was 3.1 months (range, 0.03–51.8 months). Treatment emergent adverse events (TEAEs) occurred in 901 (96.7%) of 932 patients receiving eribulin and 629 (91.3%) of 689 patients in the comparator arm. Serious TEAEs occurred in 199 (21.4%) of patients on eribulin and 155 (22.5%) of those on the comparator, and TEAEs leading to therapy discontinuation occurred in 105 (11.3%) of eribulin patients and 94 (13.6%) of patients receiving comparator. Both treatment arms had manageable safety profiles consistent with their known TEAEs. TEAEs of any grade occurring in >10% of either arm and grade 3 or 4 TEAEs occurring in >2% of either arm are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Treatment emergent adverse events occurring at >10% for any grade or >2% for grade 3 or 4

| Eribulin (n = 932) |

Comparator (n = 689) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Any grade | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

| Subjects with any TEAE | 901 (96.7) | 361 (38.7) | 258 (27.7) | 629 (91.3) | 248 (36.0) | 76 (11.0) |

| Subjects with any serious TEAE | 199 (21.4) | 83 (8.9) | 49 (5.3) | 155 (22.5) | 60 (8.7) | 38 (5.5) |

| Subjects with TEAEs leading to discontinuation | 105 (11.3) | 49 (5.3) | 10 (1.1) | 94 (13.6) | 43 (6.2) | 17 (2.5) |

| Neutropenia | 500 (53.6) | 218 (23.4) | 208 (22.3) | 142 (20.6) | 53 (7.7) | 20 (2.9) |

| Alopecia | 361 (38.7) | 0 | 0 | 42 (6.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 268 (28.8) | 7 (0.8) | 0 | 176 (25.5) | 13 (1.9) | 0 |

| Peripheral neuropathya | 266 (28.5) | 64 (6.9) | 4 (0.4) | 87 (12.6) | 10 (1.5) | 0 |

| Leukopenia | 255 (27.4) | 113 (12.1) | 18 (1.9) | 74 (10.7) | 21 (3.0) | 3 (0.4) |

| Fatigue | 221 (23.7) | 24 (2.6) | 3 (0.3) | 116 (16.8) | 23 (3.3) | 1 (0.1) |

| Asthenia | 203 (21.8) | 45 (4.8) | 0 | 122 (17.7) | 27 (3.9) | 0 |

| Anemia | 177 (19.0) | 17 (1.8) | 1 (0.1) | 133 (19.3) | 11 (1.6) | 2 (0.3) |

| Pyrexia | 161 (17.3) | 3 (0.3) | 0 | 56 (8.1) | 4 (0.6) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 158 (17.0) | 4 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | 174 (25.3) | 27 (3.9) | 1 (0.1) |

| Constipation | 154 (16.5) | 3 (0.3) | 0 | 89 (12.9) | 3 (0.4) | 0 |

| Headache | 148 (15.9) | 5 (0.5) | 0 | 73 (10.6) | 0 | 2 (0.3) |

| Vomiting | 146 (15.7) | 5 (0.5) | 2 (0.2) | 119 (17.3) | 11 (1.6) | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 129 (13.8) | 29 (3.1) | 4 (0.4) | 79 (11.5) | 19 (2.8) | 7 (1.0) |

| Back pain | 124 (13.3) | 9 (1.0) | 2 (0.2) | 49 (7.1) | 5 (0.7) | 1 (0.1) |

| Weight decreased | 124 (13.3) | 3 (0.3) | 0 | 53 (7.7) | 1 (0.1) | 0 |

| Cough | 113 (12.1) | 4 (0.4) | 0 | 57 (8.3) | 1 (0.1) | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 106 (11.4) | 5 (0.5) | 1 (0.1) | 34 (4.9) | 3 (0.4) | 0 |

| Anorexia | 101 (10.8) | 2 (0.2) | 0 | 32 (4.6) | 3 (0.4) | 0 |

| Bone pain | 97 (10.4) | 15 (1.6) | 0 | 57 (8.3) | 6 (0.9) | 0 |

| Pain in extremity | 94 (10.1) | 8 (0.9) | 0 | 47 (6.8) | 5 (0.7) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 73 (7.8) | 2 (0.2) | 0 | 70 (10.2) | 7 (1.0) | 0 |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 60 (6.4) | 23 (2.5) | 0 | 20 (2.9) | 2 (0.3) | 0 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 32 (3.4) | 22 (2.4) | 9 (1.0) | 9 (1.3) | 4 (0.6) | 5 (0.7) |

| Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome | 8 (0.9) | 2 (0.2) | 0 | 240 (34.8) | 72 (10.4) | 0 |

aPeripheral neuropathy combines the following preferred terms: peripheral neuropathy, neuropathy peripheral, neuropathy, peripheral motor neuropathy, polyneuropathy, peripheral sensory neuropathy, peripheral sensorimotor neuropathy, demyelinating polyneuropathy, and paraesthesia.

discussion

This pooled analysis evaluated the efficacy of eribulin in 1644 patients with MBC who had received at least one prior chemotherapy regimen for advanced disease within the previously reported Studies 301 [6] and 305 [4]. The current analysis specifically assesses the efficacy of eribulin in the patient population defined according to the EU label, and in subgroups of interest based on more updated data. The majority of patients in this analysis received eribulin in the third-line or higher setting due to the fact that all patients from Study 305 received treatment in the third-line or higher setting as per the study design [4].

The limitations of this pooled analysis include that it was not preplanned and the complicated nature of the pooling of data because the patient groups from the two studies (Study 301 and Study 305) varied in terms of the extent of prior chemotherapy. However, the statistical models and analysis used took these differences into account. Additionally, the two studies also differed in their control arms––while Study 301 used capecitabine as the active comparator, Study 305 used TPC. However, considering the lack of data from prospective studies in patient populations that match the current indication of eribulin [5], this pooled analysis should provide clinicians with valuable additional data to aid treatment decisions.

The statistically significant differences observed in OS are a strength of these pooled analyses, since OS has been the gold standard end point in phase III oncology clinical trials since the 1980s [8]. While surrogate end points (e.g. PFS) can markedly reduce the number of patients needed to detect a statistically significant benefit (in comparison with OS analysis), meta-analyses have, however, shown that these are not always reliable and PFS and OS may only weakly correlate [9, 10]. The poor correlation between PFS and OS may be related to the composite nature of PFS as an end point, cross-over, and poststudy anticancer therapies [11].

In our pooled analysis, the median OS was significantly longer with eribulin compared with the control arm. The HRs were similarly in favor of eribulin both in the overall analysis and in the sensitivity analysis, which included ER status and the number of organs involved as covariates due to the large treatment effects observed. By adjusting for these factors, which are also considered prognostic in patients with MBC [12], the sensitivity analysis aimed to balance the impact of these two subgroups on the overall effects of treatment on OS. Treatment with eribulin was also associated with significantly longer PFS.

Treatment of HER2-positive tumors by chemotherapy alone is considered when therapies comprising anti-HER2 agents are contraindicated or not available. In contrast, chemotherapy is the standard of care in patients with HER2-negative breast cancer, which constitutes ∼85% of women with MBC [13], and is associated with poor prognosis and limited effective treatment options [14]. Clinical studies of eribulin in the context of targeted HER2 are ongoing and should provide additional insight for eribulin treatment of HER2-positive tumors. Given that patients with HER2-negative disease represented a large subset of the population in Studies 305 and 301, and HER2 status was a stratification factor in both, the current analysis of this subgroup is of interest, and seems both robust and valuable. The current analysis demonstrated that eribulin substantially improved OS compared with control treatments in this subgroup of pooled patients, irrespective of the analysis model used.

In our pooled analysis, benefits with eribulin compared with the control were also observed in other subgroups of interest, such as patients with TNBC or ER-negative disease, with these improvements again achieving nominal statistical significance.

Capecitabine, as a single agent, is a commonly used option beyond first-line treatment. As patients treated with capecitabine represented the largest subgroup in terms of treatment type in the comparator arm in this analysis, it allowed for comparisons to be made versus the patients treated with eribulin. The pooled analysis of all patients treated with eribulin versus capecitabine represents an interesting set of data to help place eribulin in the hierarchy of treatment. Ultimately, the choice to administer eribulin in the second line or higher setting will likely depend on both patient preference and toxicity profile following exposure to first-line treatment. Our pooled analyses suggest that treatment with eribulin compared with capecitabine significantly improves OS. The eribulin benefits were maintained in subgroups of patients with HER2-negative, ER-negative, or TNBC disease, among others, suggesting a tendency for longer survival outcomes with eribulin compared with capecitabine.

conclusions

These data provide an assessment of the efficacy of eribulin in patients with MBC which matched the EU label. In this pooled analysis, eribulin was associated with longer OS than the control arm in the overall patient population and in various subgroups, including patients with HER2-negative disease and TNBC. Our dataset is extensive and the analyses appear to be robust with eribulin repeatedly demonstrating a survival benefit in comparison with control treatment. Our findings support the use of eribulin earlier in the treatment paradigm for patients with MBC that matched the target population as defined in the EU label.

funding

No payment was made to any author for the preparation of this manuscript or the analysis, though some authors are employees of Eisai Inc. Editorial support was provided by Oxford PharmaGenesis, Inc. and this was funded by Eisai. Grant number is not applicable.

disclosure

XP has received consulting fees from Eisai, Roche, Novartis, Amgen, GSK, Pierre Fabre, and Teva. FM has received consulting honoraria from Eisai, Roche, Novartis, Amgen, PharmaMar, and AstraZeneca. RK received honoraria from Eisai. MG and EB are employees of Eisai Inc. AW has received consulting fees from Eisai, Roche, AstraZeneca, and Novartis.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

The authors thank Yi He and Haihong Zhu (Eisai Inc., Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA) for their contributions to the statistical analyses.

references

- 1.SEER Cancer Statistics Factsheets: Female Breast Cancer. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html (5 November 2015, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardoso F, Costa A, Norton L et al. ESO-ESMO 2nd international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC2). Ann Oncol 2014; 25: 1871–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Breast Cancer; Version 3.2015. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf (5 November 2015, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortes J, O'Shaughnessy J, Loesch D et al. Eribulin monotherapy versus treatment of physician's choice in patients with metastatic breast cancer (EMBRACE): a phase 3 open-label randomised study. Lancet 2011; 377: 914–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halaven 0.44 mg/ml solution for injection [summary of product characteristics]. Hertfordshire, UK: Eisai Europe Limited. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaufman PA, Awada A, Twelves C et al. Phase III open-label randomized study of eribulin mesylate versus capecitabine in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline and a taxane. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 594–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Twelves C, Cortes J, Vahdat L et al. Efficacy of eribulin in women with metastatic breast cancer: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014; 148: 553–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCain JA., Jr The ongoing evolution of endpoints in oncology. Manag Care 2010; 19(5 Suppl 1): 1–11.21128520 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burzykowski T, Buyse M, Piccart-Gebhart MJ et al. Evaluation of tumor response, disease control, progression-free survival, and time to progression as potential surrogate end points in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 1987–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cortazar P, Justice R, Johnson J et al. US Food and Drug Administration approval overview in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 1705–1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korn EL, Freidlin B, Abrams JS. Overall survival as the outcome for randomized clinical trials with effective subsequent therapies. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 2439–2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andre F, Slimane K, Bachelot T et al. Breast cancer with synchronous metastases: trends in survival during a 14-year period. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 3302–3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howlader N, Altekruse SF, Li CI et al. US incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by joint hormone receptor and HER2 status. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014; 106, doi:010.1093/jnci/dju1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Partridge AH, Rumble RB, Carey LA et al. Chemotherapy and targeted therapy for women with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative (or unknown) advanced breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 3307–3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.