We carried out targeted sequencing of BRCA1/2 in an unselected cohort of patients diagnosed with primary breast cancer within a population without strong founder mutations. Eleven percent of cases harbored a germline or somatic BRCA1/2 mutation, and the ratio of germline versus somatic mutation was 2 : 1. This has implications for treatment, genetic counseling, and interpretation of tumor-only testing.

Keywords: breast cancer, mutation, somatic, germline, carrier, prevalence

Abstract

Background

A mutation found in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene of a breast tumor could be either germline or somatically acquired. The prevalence of somatic BRCA1/2 mutations and the ratio between somatic and germline BRCA1/2 mutations in unselected breast cancer patients are currently unclear.

Patients and methods

Paired normal and tumor DNA was analyzed for BRCA1/2 mutations by massively parallel sequencing in an unselected cohort of 273 breast cancer patients from south Sweden.

Results

Deleterious germline mutations in BRCA1 (n = 10) or BRCA2 (n = 10) were detected in 20 patients (7%). Deleterious somatic mutations in BRCA1 (n = 4) or BRCA2 (n = 5) were detected in 9 patients (3%). Accordingly, about 1 in 9 breast carcinomas (11%) in our cohort harbor a BRCA1/2 mutation. For each gene, the tumor phenotypes were very similar regardless of the mutation being germline or somatically acquired, whereas the tumor phenotypes differed significantly between wild-type and mutated cases. For age at diagnosis, the patients with somatic BRCA1/2 mutations resembled the wild-type patients (median age at diagnosis, germline BRCA1: 41.5 years; germline BRCA2: 49.5 years; somatic BRCA1/2: 65 years; wild-type BRCA1/2: 62.5 years).

Conclusions

In a population without strong germline founder mutations, the likelihood of a BRCA1/2 mutation found in a breast carcinoma being somatic was ∼1/3 and germline 2/3. This may have implications for treatment and genetic counseling.

introduction

The tumor suppressor genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 have a critical role in the repair of DNA. Inactivation of either of these genes fundamentally influences cancer risk and development [1–3]. Alleles can be inactivated by several mechanisms including germline mutation, somatic mutation, and epigenetic downregulation. The prevalence of somatic BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in breast cancer is currently unclear, as studies have either been small in size or have focused only on a selected group of patients [4–13]. Somatic mutation status is important to know since not only germline but also somatic mutations are believed to be treatment predictive for response to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors and platinum agents [14]. For relapsed ovarian cancer, the PARP inhibitor olaparib has recently been approved in Europe for use in patients with BRCA1/2 mutations—regardless of the mutations being germline or somatic [15, 16]. Ongoing trials will determine whether this will be the case also for breast cancer patients [17].

Importantly, the ratio between somatic and germline mutations has implications for pretest genetic counseling of breast cancer patients and for settings where only tumor specimens, not necessarily the matched germline DNA, are analyzed. Additionally, cataloguing somatic BRCA1 and BRCA2 alterations could aid in the interpretation of germline variants of unknown significance [18].

For the present study, we have analyzed an unselected cohort of 273 primary breast cancer patients treated in south Sweden at the Skåne University Hospital in Malmö. The aims were to determine the prevalence of germline and somatic BRCA1/2 mutations, to determine the ratio between somatic and germline BRCA1/2 mutations, and to describe clinicopathological and molecular characteristics of the tumors. Here, we use the term ‘mutation’ to describe a deleterious sequence variant, and the term ‘carrier’ to describe an individual with a germline mutation.

materials and methods

patient cohort and samples

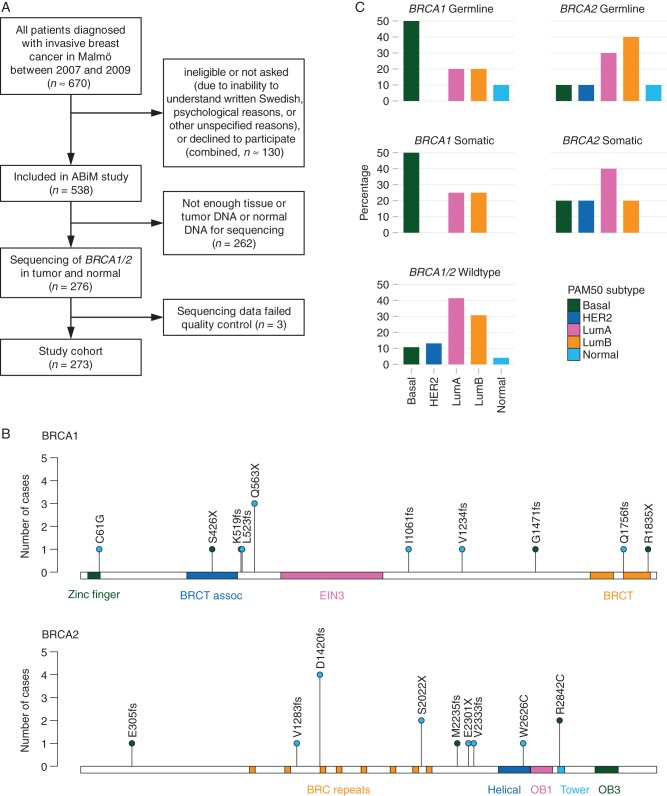

Patients with preoperative diagnosis of invasive breast cancer scheduled for surgery in Malmö, Sweden, during the years 2007–2009, were asked to participate in the population-based All Breast Cancer in Malmö (ABiM) study. Approximately 80% of all breast cancer patients in Malmö during this period were included in the ABiM study (Figure 1A). For consenting patients, fresh-frozen tumor tissue was obtained for molecular analyses, and blood samples were taken before surgery and biobanked within 2 h similar as previously described [19]. Tumor DNA/RNA and buffy coat normal DNA were isolated as previously described [19, 20]. No research tissue was taken unless it was certain not to influence the quality of diagnostic procedures. As a consequence, as well due to the quantity requirements of 10 µg tumor and 3 µg normal DNA, 276 patients were analyzed of which 3 were excluded after quality control of the sequencing data. The remaining 273 patients constitute our study population. Comparisons between the study population and the patients from the ABiM cohort that were not included in the present study population are presented in supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online. Compared with the ABiM patients not analyzed here, patients included in the study population differed significantly with respect to tumor size, grade, Ki-67, and St Gallen subtype, but were similar with regard to all other clinicopathological parameters (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 1.

(A) Study flowchart. Approximately 80% of all patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer in Malmö between 2007 and 2009 were included in the All Breast Cancer in Malmö (ABiM) study. Patients not included were either not asked, ineligible, could not be consented due to language difficulty, or declined to participate. As a result, 538 patients were included in the ABiM study during that period. With the limitation of tumor and normal DNA of sufficient sequencing quality, we were able to study BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in 273 patients. (B) BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations by protein position. Single-nucleotide variants and small (≤5 bp) indels mapped to the canonical protein sequence are shown. blue, germline mutations. Dark Green, somatic mutations. Protein domains are shown as colored bars. BRCT, BRCA1 C-terminus; EIN3, ethylene insensitive 3; OB, oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding. (C) Distribution of the PAM50 intrinsic subtype across mutation subgroups. BRCA1 germline mutant tumors have a similar subtype distribution as BRCA1 somatic mutants, whereas BRCA2 germline and somatic mutants are similar to BRCA1/2 wild-type tumors.

targeted sequencing and variant calling

For paired normal and tumor DNA, the coding exons plus 14 bp of each intron boundary of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumor suppressor genes were target captured (Agilent SureSelect; supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online) and sequenced to a median coverage of 603× (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online) on Illumina HiSeq 2000 instruments with paired-end 101 bp reads. After alignment, identity and match between tumor and normal samples were confirmed by single nucleotide polymorphism analysis. We used VarScan [21] to call single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels in BRCA1 and BRCA2 (see supplementary Methods, available at Annals of Oncology online). Variants were classified as somatic if they were present in the tumor sample only, as germline if they were present in both the tumor and the normal sample, and were removed if they were present only in the normal sample.

assessment of the deleteriousness of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants

Variants located in introns (excluding splice sites) and synonymous SNVs were excluded. All variants (SNVs or indels) that resulted in a frameshift or a loss or gain of a stop codon were considered deleterious, except variants in the last exon of BRCA2. We considered SNVs that resulted in the change of one amino acid as deleterious if they were annotated as class 5 (pathogenic) in the Breast Cancer Information Core (BIC) [22], or pathogenic in ClinVar [23], or if Align-GVGD (http://agvgd.iarc.fr) predicted a class of C65 (deleterious).

gene expression profiling and intrinsic breast cancer subtype

Tumors were subtyped according to St Gallen criteria as well as by PAM50 gene expression subtyping (supplementary Methods, available at Annals of Oncology online) based on RNA sequencing [19].

survival analysis

For overall survival (OS), vital status was checked in the Swedish Census Register. For recurrence-free survival (RFS), recurrence information was obtained from the clinical cancer database INCA. Events were death of any cause for OS, and local or distant recurrence for RFS. Survival analysis was done using the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test (two-tailed).

results

germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2

An unselected cohort of 273 breast cancer patients constituted our study population (Figure 1A and supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). The analysis of targeted sequencing data for BRCA1/2 genes revealed germline mutations in 20 patients (7%): 10 BRCA1 mutation carriers and 10 BRCA2 mutation carriers (Table 1 and Figure 1B). Seventeen (85%) of the mutations were caused by substitution, deletion, or insertion of a single nucleotide. One mutation was a heterozygous deletion of exons 1–17, and the other two were deletions of two and five nucleotides resulting in a frameshift.

Table 1.

All germline and somatic BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations identified in the 273 patient cohort

| Patient ID | Age | Gene | Somatic status | Mutation typea | Exon | cDNA change | Protein change | Evidenceb | Tumor size (mm) | Lymph node statusc | NHGd | Ki-67 (%) | St Gallen subtype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | <40 | BRCA1 | Germline | Nonsynonymous SNV | 5 | c.181T>G | p.C61G | A | 11–20 | Pos | 3 | >20 | Basal |

| P2 | 50–59 | BRCA1 | Germline | Frameshift del | 11 | c.1556delA | p.K519fs | B, F | 11–20 | Neg | 3 | >20 | Basal |

| P3 | 50–59 | BRCA1 | Germline | Frameshift del | 11 | c.1568delT | p.L523fs | F, N | >20 | Pos | 3 | ≤20 | LumA |

| P4 | 40–49 | BRCA1 | Germline | Stop-gain SNV | 11 | c.1687C>T | p.Q563X | B, X | >20 | Pos | 3 | >20 | LumB HER2+ |

| P5 | 50–59 | BRCA1 | Germline | Stop-gain SNV | 11 | c.1687C>T | p.Q563X | B, X | 11–20 | Neg | 3 | >20 | Basal |

| P6 | 60–69 | BRCA1 | Germline | Stop-gain SNV | 11 | c.1687C>T | p.Q563X | B, X | 11–20 | Neg | 2 | ≤20 | LumA |

| P7 | <40 | BRCA1 | Germline | Frameshift del | 11 | c.3182delT | p.I1061fs | F, N | >20 | Pos | 3 | >20 | LumB HER2− |

| P8 | <40 | BRCA1 | Germline | Frameshift del | 11 | c.3700_3704del | p.V1234fs | B, F | Unknown | Neg | 2 | ≤20 | LumA |

| P9 | 40–49 | BRCA1 | Germline | Frameshift ins | 20 | c.5266dupC | p.Q1756fs | B, F | >20 | Unknown | 3 | >20 | LumB HER2+ |

| P10 | <40 | BRCA1 | Germline | Heterozygous del | 1–17 | L | 11–20 | Pos | 3 | >20 | Basal | ||

| P11 | ≥80 | BRCA2 | Germline | Frameshift del | 11 | c.3846_3847del | p.V1283fs | B, F | >20 | Neg | 3 | >20 | Basal |

| P12 | <40 | BRCA2 | Germline | Frameshift del | 11 | c.4258delG | p.D1420fs | B, F | 11–20 | Neg | 3 | >20 | LumB HER2− |

| P13 | 40–49 | BRCA2 | Germline | Frameshift del | 11 | c.4258delG | p.D1420fs | B, F | >20 | Pos | 3 | ≤20 | LumA |

| P14 | 40–49 | BRCA2 | Germline | Frameshift del | 11 | c.4258delG | p.D1420fs | B, F | 11–20 | Pos | 2 | >20 | LumB HER2− |

| P15 | 60–69 | BRCA2 | Germline | Frameshift del | 11 | c.4258delG | p.D1420fs | B, F | 11–20 | Pos | 3 | >20 | LumB HER2− |

| P16 | 50–59 | BRCA2 | Germline | Stop-gain SNV | 11 | c.6065C>G | p.S2022X | B, X | 11–20 | Pos | 2 | ≤20 | LumA |

| P17 | ≥80 | BRCA2 | Germline | Stop-gain SNV | 11 | c.6065C>G | p.S2022X | B, X | 11–20 | Pos | 3 | >20 | LumB HER2− |

| P18 | 60–69 | BRCA2 | Germline | Stop-gain SNV | 12 | c.6901G>T | p.E2301X | N, X, D | 11–20 | Neg | 3 | ≤20 | Basal |

| P19 | <40 | BRCA2 | Germline | Frameshift ins | 13 | c.6998dupT | p.V2333fs | F, N | >20 | Neg | 3 | >20 | LumB HER2– |

| P20 | 40–49 | BRCA2 | Germline | Nonsynonymous SNV | 17 | c.7878G>C | p.W2626C | A | >20 | Pos | 3 | ≤20 | Non-lum HER2+ |

| P21 | ≥80 | BRCA1 | Somatic | Stop-gain del | 11 | c.1277delC | p.S426X | X | >20 | Pos | 3 | >20 | LumB HER2− |

| P22 | 70–79 | BRCA1 | Somatic | Frameshift del | 14 | c.4412delG | p.G1471fs | F | 11–20 | Neg | 3 | >20 | LumB HER2− |

| P23 | 40–49 | BRCA1 | Somatic | Splicing SNV | 18 | c.5074+1G>T | C, P | 11–20 | Pos | 3 | >20 | Basal | |

| P24 | 60–69 | BRCA1 | Somatic | Stop-gain SNV | 24 | c.5503C>T | p.R1835X | C, S, X | 11–20 | Neg | 3 | >20 | Basal |

| P10 | <40 | BRCA1 | Somatic | Homozygous del | 1–17 | L | 11–20 | Pos | 3 | >20 | Basal | ||

| P25 | 60–69 | BRCA2 | Somatic | Frameshift del | 10 | c.914_915del | p.E305fs | F | 11–20 | Neg | 3 | ≤20 | LumA |

| P26 | 70–79 | BRCA2 | Somatic | Frameshift del | 11 | c.6705delG | p.M2235fs | F | >20 | Unknown | 3 | >20 | Basal |

| P27 | 60–69 | BRCA2 | Somatic | Nonsynonymous SNV | 20 | c.8524C>T | p.R2842C | A, S, D | >20 | Neg | 2 | ≤20 | LumA |

| P28 | 60–69 | BRCA2 | Somatic | Nonsynonymous SNV | 20 | c.8524C>T | p.R2842C | A, S, D | >20 | Pos | 2 | ≤20 | LumA |

| P15 | 60–69 | BRCA2 | Somatic | Splicing SNV | 26 | c.9502−1G>A | P | 11–20 | Unknown | 3 | >20 | LumB HER2− | |

| P29 | 60–69 | BRCA2 | Somatic | Heterozygous del | All | L | >20 | Pos | 3 | >20 | LumB HER2+ |

In total, 31 mutations were identified in 29 patients, with 2 patients having a germline and a somatic mutation in the same gene.

aSNV, single-nucleotide variant; del, deletion; ins, insertion.

bEvidence for deleteriousness: A, Align-GVGD; B, BIC; C, ClinVar; D, see Discussion; F, frameshift; L, loss/LOH; N, novel variant; P, affects splice donor or acceptor site; S, COSMIC; X, stop-gain/loss.

cPos, positive (N1–N3); Neg, negative (N0).

dNHG, Nottingham histologic grade.

BRCA1/2 carriers versus noncarriers

Comparing the 20 BRCA1/2 germline mutation carriers with the 253 noncarriers (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online), as expected we found that carriers were significantly younger at time of diagnosis (median age 45 versus 63 years; P < 0.001), that carriers more often had present or past contralateral breast cancer than noncarriers (20% versus 3%, P < 0.01), and that tumors of carriers were more often Nottingham grade 3 (P = 0.04) and basal subtype (St Gallen 30% versus 13%, P = 0.04; PAM50 30% versus 12%, P = 0.03), and less often of the St Gallen luminal A subtype (25% versus 53%, P = 0.02). However, the median tumor size in both groups was identical (20 mm).

germline mutations in BRCA1 versus BRCA2

When comparing tumors from the 10 BRCA1 germline mutation carriers with those from the 10 BRCA2 germline mutation carriers, we found remarkable similarities in tumor size, lymph node status, and grade (supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). The median age at diagnosis was 41.5 years for BRCA1 carriers and 49.5 years for BRCA2 carriers.

somatic mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2

Somatic BRCA1 mutations were found in four noncarrier patients and one carrier patient, and somatic BRCA2 mutations were found in five noncarriers and one carrier (Table 1). No patient had somatic mutations in both BRCA1 and BRCA2, and no patient presented with more than one somatic alteration in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Combined, the overall prevalence of patients with only somatic BRCA1/2 mutations was 3% (9/273), with BRCA1 and BRCA2 each contributing approximately half. The median age at diagnosis for patients with somatic BRCA1/2 mutations was 65 years and comparable to the age of BRCA1/2 wild-type tumor patients (median 62.5 years; supplementary Tables S4 and S6, available at Annals of Oncology online). Nine (82%) of the 11 mutations were caused by substitution or deletion of a single nucleotide, of which 2 affected splice donor or acceptor sites (Table 1). The other two mutations were larger deletions of several exons: one somatic homozygous deletion of BRCA1 exons 1–17 in a carrier with a germline heterozygous deletion of these exons and one heterozygous deletion of all BRCA2 exons. Of the 11 somatic mutations, 3 were found in previous studies and listed in the COSMIC database of somatic mutations in cancer [24].

combined germline and somatic mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2

BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations occur in equal frequency

The prevalence of BRCA1 mutations (regardless of germline or somatic origin) was 5% (14/273; supplementary Table S7, available at Annals of Oncology online), and the prevalence of BRCA2 mutations was 5% (15/273). Combined, the prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations was 11% (29/273). The highest prevalence was found in patients younger than 40 years at diagnosis (46%, 6/13), all of whom were germline carriers (supplementary Table S8, available at Annals of Oncology online).

germline BRCA1/2 mutations versus somatic BRCA1/2 mutations

While patient age at diagnosis differed between germline and somatic BRCA1/2 mutation tumors, the molecular characteristics of the tumors were similar. Tumor size, lymph node status, estrogen receptor status, progesterone receptor status, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status, and St Gallen/PAM50 subtype had similar distribution in both groups (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). Two of 20 germline mutation carriers had an additional somatic mutation, presumably inactivating both alleles (patients P10 and P15 in Table 1).

intrinsic subtype is associated with mutated gene rather than germline or somatic origin

We compared the PAM50 intrinsic subtypes across the five subgroups of BRCA1 germline, BRCA1 somatic only, BRCA2 germline, BRCA2 somatic only, and BRCA1/2 wild-type tumors (Figure 1C). We found that BRCA1-mutated tumors (regardless of germline or somatic origin) had a significantly different intrinsic subtype distribution than wild-type tumors (P = 0.003), with half of the tumors being of the basal subtype. In contrast, BRCA2 had a subtype distribution that resembled more the wild-type tumors.

molecular details

The predominant mutation type was deletion of one or several bases that resulted in a frameshift, which occurred in 12/31 mutations. We observed no difference in the distribution of the type of mutation (deletion, insertion, and SNV) between germline and somatic mutations (Table 1). Mutant allele frequencies of germline BRCA1/2 mutations in normal samples ranged from 38% to 51% (median 47%), consistent with a heterozygous carrier. In the tumor samples, the same mutations generally had an increased mutant allele frequency consistent with loss of the wild-type allele in the tumor (34%–91%, median 68%). For all but two mutations, the mutant allele frequency was higher in the tumor than in the normal sample (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

survival analysis

The median follow-up was 6.4 years (range 0.6–7.6 years). Between patients with a BRCA1/2 mutation and wild-type patients, we found no significant difference in OS (5-year OS 86% in both groups, log-rank P = 0.81) or RFS (5-year RFS 84% for mutants, 92% for wild type, log-rank P = 0.35, supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). However, in the subgroup of patients who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy (147 of 273 patients), RFS was significantly inferior for patients with BRCA1/2 mutations (5-year RFS: 75% versus 92%; P = 0.049, supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). The low number of events precluded survival analysis of germline and somatic subgroups.

discussion

In the present study, we report that 3% of the tumors from our cohort of unselected breast cancer patients harbored only somatic mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 and 7% harbored germline mutations. Accordingly, the likelihood of a mutation found in a breast carcinoma being somatic was 1/3 and germline 2/3, with ratio of 1 : 2. The tumor phenotypes were found to be similar regardless of the mutation being germline or somatically acquired, but germline mutations carriers were much younger at diagnosis (median age at diagnosis, germline BRCA1 41.5 years; germline BRCA2 49.5 years; somatic BRCA1/2 64 years; wild-type BRCA1/2 62.5 years), consistent with the Knudson two-hit hypothesis [25].

Although our cohort is derived from a population-based series of breast cancer patients, we have previously shown that small- and low-grade tumors can be undersampled [19]. Therefore, and also influenced by DNA quantity requirements, patients with larger tumors and more aggressive features, such as high grade and high proliferation, were enriched in our study population. Accordingly, the prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations, both germline and somatic, may be overestimations. However, given that there was no inclusion bias for age at diagnosis or family history, the ratio of somatic to germline mutations should be unbiased and representative. Our finding that 2/3 of the BRCA1/2 mutations found in the tumors were germline highlights the need for a strategy on how to deal with identified mutations when sequencing tumors without matched peripheral blood for comparison.

A similar rate of 1/3 somatic versus 2/3 germline was found in the The Cancer Genome Atlas breast cancer study, which carried out exome sequencing of tumor and normal samples of a selected breast cancer patient cohort [26]. Meric-Bernstam et al. [13] recently published a study of germline and somatic mutations in cancer patients treated at MD Anderson. In 251 breast cancer patients, 6 somatic and 21 germline BRCA1/2 mutations were found, corresponding to a ratio of 1 : 3.5. Their cohort consisted of patients referred to a tertiary cancer center who were likely to benefit from somatic genomic testing, and most patients had metastatic or inoperable disease. Although their study is informative for that kind of setting, it is possible that such ascertainment inflates the ratio of somatic to germline BRCA1/2 mutations.

BRCA1/2 mutations may soon prove treatment predictive for breast cancer. The Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Trial (TNT) compared carboplatin with docetaxel in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer, and found that patients with germline BRCA1/2 mutations had a higher response rate with carboplatin [27]. Furthermore, a number of trials have shown a greater efficacy of PARP inhibitors in germline BRCA1/2 mutation carriers than in noncarriers, and phase III trials in this subset are ongoing [17]. In ovarian cancer, both somatic and germline BRCA1/2 mutations are now used for treatment prediction, with the approval of olaparib for relapsed BRCA1/2-mutated ovarian cancer, regardless of the mutation being germline or somatic [16].

A strength of our study is that we have detailed information about patients who were not included in the study population. Consequently, we can assess and interpret inclusion bias. Another strength is the comprehensive analytic method used, which is expected to detect a great majority of pathogenic mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2, including missense mutations and DNA copy number losses.

There are also limitations to our study. First, a rather small number of carriers results in imprecise point estimates. Second, the ratio between somatic and germline BRCA1/2 mutations depends on the study population, which must be considered for the generalizability of our results. Sweden is a country with a high incidence of breast cancer similar to that of the USA and most European nations: the lifetime risk for women is 12%. The median age at diagnosis (64 years) is higher than in many other countries. Although founder mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have been reported, carriers of the five most common mutations account for only 19% of the total number of mutation carriers (Å. Borg, personal communication). Therefore, Sweden should be viewed as a country without strong founder mutations. Third, two of the mutations we found are not yet classified as definitely pathogenic (IARC class 5). For example, although BRCA2 c.8524C>T is not listed in BIC or ClinVar as definitely pathogenic, we consider it deleterious since it was classified pathogenic by Align-GVGD and found in one ovarian cancer sample according to COSMIC and independently in two of our tumor samples. In a homology-directed repair assay, it has intermediate function [28]. The stop-gain mutation BRCA2 c.6901G>T is located in exon 12. The fact that a low expressed transcript isoform carrying an in-frame exon 12 deletion has been described [29, 30] adds some uncertainty to the pathogenicity of this mutation. Functional and larger population-based studies are likely to be carried out over the next years, and they are needed to validate our results.

In conclusion, in our data from a population without strong germline founder mutations, the likelihood of a BRCA1/2 mutation found in a breast carcinoma being somatic was ∼1/3 and germline 2/3. This could have implications for treatment and genetic counseling.

funding

This work was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society (CAN 2009/1537, 2010/800, 2010/1254, 2013/730, 2013/637, 2013/750, and 2014/562), Swedish Research Council (2009-2712, 2011-3021, 2012-1747, and 2012-1986), Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, VINNOVA, and Governmental Funding of Clinical Research within National Health Service, Swedish Breast Cancer Group, Crafoord Foundation, Lund University Medical Faculty, Gunnar Nilsson Cancer Foundation, Skåne University Hospital Foundation, BioCARE Research Program, King Gustav Vth Jubilee Foundation, Krapperup Foundation, and the Mrs. Berta Kamprad Foundation.

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

We are grateful to all patients for participation in this study. We thank Ingrid Tengrup, Lennart Bondeson, Lotta Lundgren, Jonas Manjer, and Janne Malina of the ABiM Study Group, and also thank the surgeons, physicians, and healthcare staff of the Breast Cancer Surgery Unit of Skåne University Hospital Malmö for patient recruitment. We thank members of the Translational Oncogenomics Unit, Division of Oncology and Pathology for input, and Ingrid Caro-Östergren for technical assistance.

references

- 1.Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S et al. . Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet 2003; 72: 1117–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D et al. . A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science 1994; 266: 66–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wooster R, Neuhausen SL, Mangion J et al. . Localization of a breast cancer susceptibility gene, BRCA2, to chromosome 13q12-13. Science 1994; 265: 2088–2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Futreal PA, Liu Q, Shattuck-Eidens D et al. . BRCA1 mutations in primary breast and ovarian carcinomas. Science 1994; 266: 120–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Timms KM, Liu S et al. . Incidence and outcome of BRCA mutations in unselected patients with triple receptor-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17: 1082–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janatova M, Zikan M, Dundr P et al. . Novel somatic mutations in the BRCA1 gene in sporadic breast tumors. Hum Mutat 2005; 25: 319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khoo US, Ozcelik H, Cheung AN et al. . Somatic mutations in the BRCA1 gene in Chinese sporadic breast and ovarian cancer. Oncogene 1999; 18: 4643–4646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lancaster JM, Wooster R, Mangion J et al. . BRCA2 mutations in primary breast and ovarian cancers. Nat Genet 1996; 13: 238–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miki Y, Katagiri T, Kasumi F et al. . Mutation analysis in the BRCA2 gene in primary breast cancers. Nat Genet 1996; 13: 245–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sørlie T, Andersen TI, Bukholm I, Børresen-Dale AL. Mutation screening of BRCA1 using PTT and LOH analysis at 17q21 in breast carcinomas from familial and non-familial cases. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1998; 48: 259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Looij M, Cleton-Jansen AM, van Eijk R et al. . A sporadic breast tumor with a somatically acquired complex genomic rearrangement in BRCA1. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2000; 27: 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang M, Xu Y, Ouyang T et al. . Somatic mutations in the BRCA1 gene in Chinese women with sporadic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012; 132: 335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meric-Bernstam F, Brusco L, Daniels M et al. . Incidental germline variants in 1000 advanced cancers on a prospective somatic genomic profiling protocol. Ann Oncol 2016; 27: 795–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burgess M, Puhalla S. BRCA 1/2-mutation related and sporadic breast and ovarian cancers: more alike than different. Front Oncol 2014; 4: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiggans AJ, Cass GK, Bryant A et al. . Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors for the treatment of ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 5: CD007929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C et al. . Olaparib maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed serous ovarian cancer: a preplanned retrospective analysis of outcomes by BRCA status in a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 852–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Ashworth A. Synthetic lethality and cancer therapy: lessons learned from the development of PARP inhibitors. Annu Rev Med 2015; 66: 455–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eccles DM, Mitchell G, Monteiro AN et al. . BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing-pitfalls and recommendations for managing variants of uncertain clinical significance. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 2057–2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saal LH, Vallon-Christersson J, Hakkinen J et al. . The Sweden Cancerome Analysis Network—Breast (SCAN-B) Initiative: a large-scale multicenter infrastructure towards implementation of breast cancer genomic analyses in the clinical routine. Genome Med 2015; 7: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olsson E, Winter C, George A et al. . Serial monitoring of circulating tumor DNA in patients with primary breast cancer for detection of occult metastatic disease. EMBO Mol Med 2015; 7: 1034–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE et al. . VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res 2012; 22: 568–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szabo C, Masiello A, Ryan JF, Brody LC. The breast cancer information core: database design, structure, and scope. Hum Mutat 2000; 16: 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Riley GR et al. . ClinVar: public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res 2014; 42: D980–D985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forbes SA, Beare D, Gunasekaran P et al. . COSMIC: exploring the world's knowledge of somatic mutations in human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 2015; 43: D805–D811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knudson AG., Jr Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1971; 68: 820–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2012; 490: 61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tutt A, Ellis P, Kilburn L et al. . The TNT trial. In 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. Abstract S3-01 Presented 11 December 2014 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guidugli L, Pankratz VS, Singh N et al. . A classification model for BRCA2 DNA binding domain missense variants based on homology-directed repair activity. Cancer Res 2013; 73: 265–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bieche I, Lidereau R. Increased level of exon 12 alternatively spliced BRCA2 transcripts in tumor breast tissue compared with normal tissue. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 2546–2550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rauh-Adelmann C, Lau KM, Sabeti N et al. . Altered expression of BRCA1, BRCA2, and a newly identified BRCA2 exon 12 deletion variant in malignant human ovarian, prostate, and breast cancer cell lines. Mol Carcinog 2000; 28: 236–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.