SQUIRE was a phase III study of gemcitabine and cisplatin with or without necitumumab in patients with metastatic squamous NSCLC. The majority of SQUIRE patients had EGFR protein expressing tumors. Similar to SQUIRE ITT, patients with EGFR protein expressing tumors benefitted from addition of necitumumab to chemotherapy with a safety profile consistent with that of the overall SQUIRE population.

Keywords: EGFR expressing, necitumumab, squamous NSCLC, SQUIRE

Abstract

Background

SQUIRE demonstrated addition of necitumumab to gemcitabine and cisplatin significantly improved survival in patients with stage IV sq-NSCLC. Here, we report additional outcomes for the subpopulation of patients with tumor epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) protein expression.

Patients and methods

Patients with pathologically confirmed stage IV sq-NSCLC were randomized 1:1 to receive a maximum of six 3-week cycles of gemcitabine (1250 mg/m2 i.v., days 1 and 8) and cisplatin (75 mg/m2 i.v., day 1) chemotherapy with or without necitumumab (800 mg i.v., days 1 and 8). Patients in the chemotherapy plus necitumumab group with no progression continued on necitumumab alone until disease progression or intolerable toxicity. SQUIRE included mandatory tissue collection. EGFR protein expression was detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in a central laboratory. Exploratory analyses were pre-specified for patients with EGFR protein expressing (EGFR > 0) and non-expressing (EGFR = 0) tumors.

Results

A total of 982 patients [90% of intention-to-treat (ITT)] had evaluable IHC results. The large majority of these patients (95%) had tumor samples expressing EGFR protein; only 5% had tumors without detectable EGFR protein. Overall survival (OS) for EGFR > 0 patients was significantly longer in the necitumumab plus gemcitabine–cisplatin group than in the gemcitabine–cisplatin group {stratified hazard ratio (HR) 0.79 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.69, 0.92; P = 0.002]; median 11.7 months (95% CI 10.7, 12.9) versus 10.0 months (8.9, 11.4)}. Additionally, an OS benefit was seen in all pre-specified subgroups in EGFR > 0 patients. However, OS HR for EGFR = 0 was 1.52. Adverse events of interest with the largest difference between treatment groups in EGFR > 0 patients (Grade ≥3) were hypomagnesemia (10% versus <1%) and skin rash (6% versus <1%).

Conclusions

In line with SQUIRE ITT, addition of necitumumab to gemcitabine–cisplatin significantly prolonged OS and was generally well tolerated in the subpopulation of patients with EGFR-expressing advanced sq-NSCLC. The benefit from addition of necitumumab to chemotherapy was not apparent in this analysis for the small subgroup of patients with non-EGFR-expressing tumors.

Clinical Trial

introduction

Advanced squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) imposes a heavy worldwide burden [1]. Prognosis is typically poor and the majority of patients are diagnosed with locally advanced or metastatic disease [2]. Squamous NSCLC is a distinct disease and is differentiated from other types of lung cancer not only by the difference in histology, but also its genetic profile [3].

In contrast to adenocarcinoma, genetic alterations such as ALK-translocation and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations are rare in squamous disease, making these patients unsuitable for ALK-inhibitors or EGFR TKIs [4, 5]. In addition, pemetrexed and bevacizumab are only indicated for non-squamous NSCLC. Therefore, platinum-based chemotherapy has remained the standard of care for the first-line treatment of squamous NSCLC for many years. Recently, new molecules have been approved in the United States and the EU for the treatment of advanced squamous NSCLC in the second-line setting including the immunotherapy agents nivolumab and pembrolizumab, and the anti-VEGFR2 monoclonal antibody (mAb) ramucirumab. Recently, the US Food and Drug Administration granted approval to necitumumab—an anti-EGFR mAb—for first-line treatment of patients with metastatic squamous NSCLC in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin chemotherapy [6]. Also, the European Medicines Agency approved necitumumab for first-line treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic EGFR-expressing squamous NSCLC [7]. These marked the first approvals of a targeted therapy in squamous NSCLC in the first-line setting, despite numerous attempts over the past two decades.

The EGFR is implicated in a variety of cancers, including NSCLC of squamous histology [8, 9]. Activated EGFR enhances processes responsible for tumor growth and progression including angiogenesis, invasion/metastasis, the promotion of proliferation, and inhibition of apoptosis [8, 10]. EGFR protein is detectable in the majority of tumor specimens of patients with NSCLC (especially squamous carcinomas) [11–13]. Previously, the phase III FLEX trial reported a significant improvement in overall survival (OS) with the addition of the anti-EGFR antibody cetuximab to chemotherapy in patients with NSCLC tumors having EGFR protein expression. On subgroup analysis, patients with squamous histology compared with non-squamous had a more pronounced survival effect [14].

Necitumumab is a second-generation, recombinant, human immunoglobulin IgG1 EGFR antibody that binds to EGFR with high specificity and affinity, competing with natural ligands and preventing receptor activation and downstream signaling [15]. Necitumumab inhibits EGFR-dependent tumor-cell proliferation and can exert cytotoxic effects in tumor cells through ADCC [16]. In contrast to the phase III study INSPIRE that did not show a benefit for the addition of necitumumab to pemetrexed and cisplatin in patients with advanced non-squamous NSCLC [17], the pivotal randomized phase III trial SQUIRE showed that the addition of necitumumab to gemcitabine and cisplatin chemotherapy improved OS compared with chemotherapy alone {hazard ratio (HR) = 0.84 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.74, 0.96; P = 0.01]}, was well tolerated, and did not negatively affect health-related quality-of-life in patients with advanced squamous NSCLC [18].

In SQUIRE, tissue collection for study participants was mandatory. Approximately 90% of study population in SQUIRE had tissue available for an analysis of EGFR protein expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC) [18]. Noting the relevance of the EGFR pathway in the etiology of squamous NSCLC [19–21], here we report the efficacy and safety results of the subpopulation of SQUIRE patients with EGFR-expressing tumors.

patients and methods

study design

The SQUIRE study design, treatments, and eligibility criteria have been previously reported [18]. Briefly, patients with stage IV squamous NSCLC were randomized 1:1 to necitumumab (800 mg absolute dose i.v. days 1, 8) plus gemcitabine–cisplatin (G = 1250 mg/m2 i.v. days 1, 8; C = 75 mg/m2 i.v. day 1), or gemcitabine–cisplatin alone every 21 days for up to 6 cycles. Patients in the experimental arm with no disease progression continued on necitumumab monotherapy until disease progression. The primary objective of SQUIRE was OS. Secondary end points included progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR), time to treatment failure (TtTF), safety, and quality of life.

The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, and applicable local regulations. The protocol was approved by the ethics committees of all participating centers, and all patients provided written informed consent before study entry.

procedures related to EGFR IHC

Archived tumor tissue (pretreatment) derived from either the primary tumor or metastatic sites were collected and stored at a secure central laboratory. A tissue block or minimum of four tissue slides (paraffin embedded) was required for analyses. Tumor EGFR protein expression was assayed at a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified laboratory by IHC with the EGFR PharmDx Kit (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and evaluated independently by two trained pathologists to derive percent positive. Discordant results were jointly resolved by the two pathologists.

statistical analysis

In a preplanned exploratory analysis, patients were categorized into detectable (EGFR > 0) where at least one positive cell was identified by EGFR IHC or non-detectable (EGFR = 0) EGFR expression groups. Efficacy was assessed in all randomized patients with evaluable IHC assay results [intention-to-treat (ITT) EGFR subpopulations; EGFR > 0 and EGFR = 0]. OS, PFS, and TtTF were compared between treatment groups using a stratified log-rank test, and survival curves estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. HRs and 95% CIs were estimated from stratified Cox proportional hazards models. Stratification factors were ECOG performance status (0–1 versus 2) and geographic region (North America, Europe, Australia versus South America, South Africa, India versus eastern Asia). ORR was summarized by treatment group, and compared using a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test. A series of efficacy analyses including a STEPP analysis assessed the efficacy outcomes across the range of EGFR expression based on percent positive cells. A sensitivity analysis for OS was carried out among EGFR > 0 patients using censoring for post-study docetaxel.

Safety was assessed in the specified subpopulations in all patients who received at least one dose of study medication and was analyzed according to actual treatment received (safety EGFR subpopulations). Adverse events were coded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 16.0 and graded with the NCI-CTCAE version 3.0.

In a separate exploratory post hoc analysis, the correlation of EGFR copy number gain by FISH with efficacy outcomes was assessed. For this analysis, tumor samples from 557 patients (51% of ITT) were available. Tumors were categorized as FISH positive or negative based on Colorado Classification [22].

results

Archived tissue was collected from 1060 patients (97% of ITT). Tumor EGFR protein expression data based on IHC were available for 982 of 1093 (90%) patients from the SQUIRE study ITT population out of whom, 935 (95%) had tumor samples expressing EGFR protein (EGFR > 0). In both treatment groups, most tumor tissue samples expressing detectable EGFR protein had a high percentage of cells staining positive (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Baseline characteristics were well balanced between treatment groups in the EGFR > 0 subpopulation (Table 1). Only 47 of 982 (5%) patients had tumor tissue samples without detectable EGFR protein (EGFR = 0). Supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online, presents baseline characteristics for EGFR = 0 subpopulation.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients (intention-to-treat epidermal growth factor receptor > 0 subpopulation)

| Necitumumab plus gemcitabine–cisplatin (n = 462) | Gemcitabine–cisplatin (n = 473) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age: years, median (range) | 62 (35–84) | 62 (32–86) |

| Age group (years) | ||

| <65 | 285 (62%) | 296 (63%) |

| ≥65 | 177 (38%) | 177 (37%) |

| <70 | 380 (82%) | 396 (84%) |

| ≥70 | 82 (18%) | 77 (16%) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 381 (82%) | 400 (85%) |

| Female | 81 (18%) | 73 (15%) |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0–1 | 418 (90%) | 436 (92%) |

| 2 | 44 (10%) | 37 (8%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 388 (84%) | 396 (84%) |

| Asian | 36 (8%) | 38 (8%) |

| All others | 38 (8%) | 39 (8%) |

| Smoking | ||

| Smoker | 424 (92%) | 430 (91%) |

| Non-smoker or ex-light smoker | 37 (8%) | 43 (9%) |

| Geographic region | ||

| North America, Europe, Australia | 400 (87%) | 407 (86%) |

| South America, South Africa, India | 47 (10%) | 50 (11%) |

| Eastern Asia | 15 (3%) | 16 (3%) |

| Number of metastatic organ systems | ||

| 1 | 42 (9%) | 45 (10%) |

| 2 | 164 (35%) | 175 (37%) |

| >2 | 256 (55%) | 253 (53%) |

| Sites of metastatic disease | ||

| Bone | 103 (22%) | 108 (23%) |

| Brain | 20 (4%) | 24 (5%) |

| Liver | 89 (19%) | 96 (20%) |

Data are n (%).

Exposure to chemotherapy was similar in both treatment groups in the EGFR > 0 subpopulation (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Of the 456 patients who received necitumumab plus gemcitabine–cisplatin, 242 (52%) continued on necitumumab continuation monotherapy. The maximum number of cycles reached on necitumumab by the cutoff date was 45.

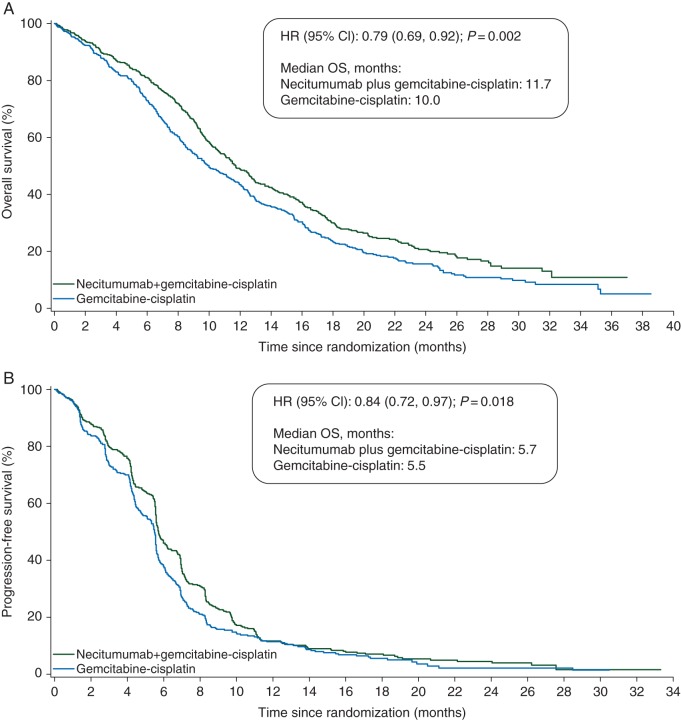

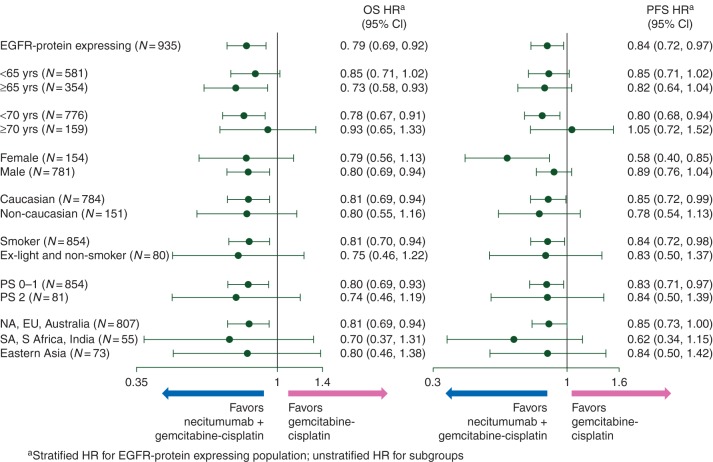

Supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online, summarizes the efficacy results for the EGFR > 0 subpopulation. Patients in the necitumumab plus gemcitabine–cisplatin group had significantly prolonged OS compared with those in the gemcitabine–cisplatin group [stratified HR 0.79 (95% CI 0.69, 0.92), P = 0.002]. The Kaplan–Meier curve for OS in the EGFR > 0 subpopulation showed an early separation in favor of the necitumumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin group (Figure 1A). PFS of the EGFR > 0 subpopulation was also significantly prolonged in the experimental arm compared with control [stratified HR 0.84 (95% CI 0.72, 0.97), P = 0.018] (Figure 1B). TtTF also showed significant prolongation (P = 0.006); ORR and disease control rate were numerically higher in favor of the experimental arm without statistical significance (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). In subgroup analyses for OS and PFS in the EGFR > 0 subpopulation, necitumumab treatment benefit was reported across most subgroups including PS2 (OS HR = 0.74, PFS HR = 0.84) (Figure 2). Supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online, summarizes the number of patients in the EGFR > 0 subpopulation who received post-study systemic anticancer therapy. Overall, post-study therapy was balanced between treatment arms. Based on a sensitivity analysis of OS censoring at the start of post-study docetaxel, it is unlikely that the imbalance in docetaxel therapy (32% necitumumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin group; 24% gemcitabine and cisplatin group) was a driver for the observed OS benefit (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of (A) overall survival and progression-free survival (B) (intention-to-treat epidermal growth factor receptor > 0 subpopulation).

Figure 2.

Subgroup analyses. Forest plots of overall survival and progression-free survival (intention-to-treat epidermal growth factor receptor > 0 subpopulation) in subgroups defined by baseline characteristics. HR, hazard ratio; NA, North America; EU, Europe; SA, South America; S Africa, South Africa.

The STEPP analysis across the ranges of EGFR protein expression for OS and PFS did not lead to the identification of a cutpoint to differentiate those who benefit from the addition of necitumumab versus those who do not (supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). The survival benefit for patients with EGFR > 0 seemed to extend across the range of EGFR IHC values including low-expressing subgroups (supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). However, patients in the EGFR = 0 subpopulation did not appear to benefit from the addition of necitumumab to gemcitabine and cisplatin (OS HR = 1.52; PFS HR = 1.33). In interaction analyses modeling, the EGFR = 0 and EGFR > 0 patients together using a stratified model, the P values for the interaction of treatment with EGFR subgroup for OS and PFS were 0.015 and 0.252, respectively.

In the EGFR > 0 subpopulation, 323 (71%) of 456 patients in the necitumumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin group and 281 (60%) of 468 in the gemcitabine and cisplatin group had one or more grade 3 or worse treatment-emergent adverse events. Grade 3 or worse adverse events that were more common (>2%) in the necitumumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin group than in the gemcitabine and cisplatin group included hypomagnesemia (9% versus <1%) and rash (3% versus <1%) (supplementary Table S6, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Adverse events in the EGFR > 0 subpopulation leading to discontinuation of at least one study drug were reported by 139 (30%) patients in the necitumumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin group and by 118 (25%) in the gemcitabine and cisplatin group (data not shown). Neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were the most common reasons for treatment discontinuation of any therapy. In the experimental arm, 1.1% of patients discontinued treatment because of rash (versus 0% in the control arm). Including events related to disease progression in the EGFR > 0 subpopulation, adverse events with an outcome of death were reported for 50 (11%) patients in the necitumumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin group and 46 (10%) patients in the gemcitabine and cisplatin group.

In addition to the analysis of treatment-emergent adverse events, selected composite event categories based on the known safety profiles of other EGFR antibodies and the previous clinical experience of necitumumab were analyzed as adverse events of interest. Based on these categories, grade 3 or more adverse events that were more common (≥2%) in necitumumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin arm versus gemcitabine and cisplatin arm in the EGFR > 0 population included: hypomagnesemia (10% versus <1%), rash (6% versus <1%), venous thromboembolic events (5% versus 3%), and arterial thromboembolic events (4% versus 2%) (Table 2). Adverse events of interest for the EGFR = 0 population are summarized in supplementary Table S7, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Table 2.

Adverse events of interest (safety epidermal growth factor receptor > 0 subpopulation)

| Necitumumab plus gemcitabine–cisplatin (n = 456) |

Gemcitabine–cisplatin (n = 468) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade | Grade ≥3 | Any grade | Grade ≥3 | |

| Neutropenia | 199 (44%) | 112 (25%) | 206 (44%) | 126 (27%) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 5 (1%) | 4 (<1%) | 8 (2%) | 7 (1%) |

| Anemia | 186 (41%) | 46 (10%) | 212 (45%) | 50 (11%) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 101 (22%) | 48 (11%) | 120 (26%) | 51 (11%) |

| Diarrhea | 72 (16%) | 9 (2%) | 53 (11%) | 7 (1%) |

| Fatigue | 191 (42%) | 36 (8%) | 195 (42%) | 33 (7%) |

| Hypomagnesemia | 145 (32%) | 44 (10%) | 72 (15%) | 4 (<1%) |

| Hypomagnesemia (laboratory data) | 327 (83%) | 81 (21%) | 282 (71%) | 24 (6%) |

| Skin reactions | ||||

| Rash | 351 (77%) | 29 (6%) | 48 (10%) | 2 (<1%) |

| Hypersensitivity/infusion-related reaction | 8 (2%) | 2 (<1%) | 10 (2%) | 0 |

| Conjunctivitis | 37 (8%) | 1 (<1%) | 12 (3%) | 0 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 4 (<1%) | 2 (<1%)a | 4 (<1%) | 3 (<1%) |

| Arterial thromboembolic events | 26 (6%) | 18 (4%)b | 18 (4%) | 9 (2%)b |

| Venous thromboembolic events | 46 (10%) | 25 (5%)c | 25 (5%) | 12 (3%)c |

This table shows adverse events of interest according to either composite categories or preferred terms (febrile neutropenia and diarrhea only). Data are n (%).

aIncludes one fatal event (0.2%).

bFatal arterial thromboembolic events, n (%): Neci + Gem–Cis 3 (0.7%), Gem–Cis 1 (0.2%).

cFatal venous thromboembolic events, n (%): Neci + Gem–Cis 1 (0.2%), Gem–Cis 1 (0.2%).

The efficacy results of exploratory post hoc analysis of EGFR copy number gain are presented in supplementary Table S8, available at Annals of Oncology online. The OS HR for EGFR FISH positive and negative subgroups were 0.70 and 1.02, respectively, with a statistically non-significant treatment-by-marker interaction P value (0.066).

discussion

The SQUIRE trial showed that the addition of necitumumab to gemcitabine and cisplatin chemotherapy improved survival in patients with advanced squamous NSCLC, leading to the approval of necitumumab as a new treatment option in this patient population. In line with the SQUIRE ITT, the addition of necitumumab to chemotherapy was associated with a statistically significant improvement in OS and PFS in the subpopulation of patients with EGFR-expressing tumors. In addition, subgroup analyses of OS and PFS based on age, gender, smoking status, ethnicity, and performance status for patients with advanced EGFR-expressing squamous NSCLC showed consistent benefit across most subgroups. The safety profile of necitumumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin was acceptable in this subpopulation of patients as well. In general, the findings for the advanced EGFR-expressing squamous NSCLC subpopulation paralleled the results of the SQUIRE ITT with a slightly more pronounced efficacy and a similar safety profile.

SQUIRE confirmed the hypothesis generated by a subgroup analysis from the FLEX trial of cetuximab: the addition of an anti-EGFR mAb to first-line chemotherapy can be of particular use in patients with metastatic squamous NSCLC, indicating the relevance of EGFR pathway in this patient population [14, 23]. While FLEX only recruited patients with EGFR-expressing tumors, SQUIRE also included patients without detectable EGFR protein, which allowed for an exploratory analysis of efficacy outcomes in this group of patients. SQUIRE results suggest that the small group of patients with no detectable EGFR protein may not benefit from the addition of necitumumab to chemotherapy. A biologically plausible rationale can be hypothesized for the apparent lack of efficacy of an anti-EGFR mAb in patients whose tumor cells do not express the target. The value of a biomarker-oriented approach to guide the prescription of a targeted therapy is well understood in the era of precision medicine; however, the SQUIRE results (given the small subpopulation of patients with EGFR = 0, together with the complexity of EGFR pathway in NSCLC) are not conclusive regarding the lack of benefit in patients with EGFR = 0. Importantly, no specific safety concern was identified in this group that could explain the observed lack of effect.

As previously reported [18], the level of EGFR protein expression (high expression versus low expression based on H-score cutoff of 200) was not of predictive value in SQUIRE. While patients with high expression (EGFR H-score ≥200) had a more favorable HR for OS, the same trend was not observed for PFS, and the treatment-by-marker interaction test P values were not significant [18]. Further analyses of SQUIRE results across the range of EGFR IHC presented here also suggest that patients whose tumors have detectable EGFR protein benefit from the addition of necitumumab to chemotherapy, regardless of the level of EGFR protein expression.

SQUIRE was a large randomized trial specifically conducted in patients with advanced squamous NSCLC and incorporated a mandatory tissue collection. One major strength of the presented results is the high percentage of available tissue for EGFR IHC analysis in SQUIRE. In addition, the exploratory analysis of main efficacy outcomes in EGFR > 0 subpopulation was pre-specified. Nevertheless, these data should be interpreted in the context of the SQUIRE ITT results and caution should be exercised, especially when it comes to the outcomes of smaller subgroups.

The results of EGFR copy number gain by FISH in SQUIRE showed a trend for a more favorable survival HR in the EGFR FISH positive subpopulation but without statistically significant treatment-by-marker interaction tests. Half of the SQUIRE population had tumor tissue available for this analysis and this exploratory analysis was not pre-specified. Further analyses of the data are needed in order to better understand the potential predictive role of EGFR copy number gain in this setting.

In conclusion, the outcomes of SQUIRE patients with advanced EGFR-expressing squamous NSCLC treated with necitumumab in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin are consistent with that of the ITT population; this suggests a positive benefit/risk profile and further corroborates the mechanism of action of necitumumab. This work supports the existing evidence regarding the importance of EGFR in squamous NSCLC, and highlights the need for continued efforts to increase our understanding of the complex biology of the EGFR pathway in this disease.

funding

This work was supported by Eli Lilly and Company and there is no grant number.

disclosure

LP-A has received honorarium from Eli Lilly and Company. MAS has received advisory honorarium from Eli Lilly and Company. JS, RRH, VS, and RK are employees of Eli Lilly and Company and hold equity in the company. MV-G declares no conflict of interest. NT has received speaker and advisory board honoraria from Eli Lilly and Company. FRH has received research funding to his laboratory (through University of Colorado) for biomarker studies related to the SQUIRE study and has received advisory board honoraria from Eli Lilly and Company.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

We thank the patients, their families, and the study personnel across all sites for participating in this study. We wish to acknowledge Gu Mi for additional statistical support. We acknowledge Jill Kolodsick and Anastasia Perkowski from Eli Lilly and Company, who provided medical writing and editorial assistance, respectively.

references

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R et al. . GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014; 64: 364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gandara DR, Hammerman PS, Sos ML et al. . Squamous cell lung cancer: from tumor genomics to cancer therapeutics. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21: 2236–2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Besse B, Adjei A, Baas P et al. . 2nd ESMO Consensus Conference on Lung Cancer: non-small-cell lung cancer first-line/second and further lines of treatment in advanced disease. Ann Oncol 2014; 25: 1475–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology—Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. NCCN 2014 http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#site (10 February 2016, date last accessed).

- 6.Portrazza™ (necitumumab). US Prescribing Information. Eli Lilly and Company; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Portrazza™ (necitumumab). EU Prescribing Information. Eli Lilly and Company; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendelsohn J. Targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor for cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20: 1s–13s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baselga J. Why the epidermal growth factor receptor? The rationale for cancer therapy. Oncologist 2002; 7(Suppl 4): 2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salomon DS, Brandt R, Ciardiello F, Normanno N. Epidermal growth factor-related peptides and their receptors in human malignancies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 1995; 19: 183–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veale D, Ashcroft T, Marsh C et al. . Epidermal growth factor receptors in non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 1987; 55: 513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fontanini G, Vignati S, Bigini D et al. . Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFr) expression in non-small cell lung carcinomas correlates with metastatic involvement of hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes in the squamous subtype. Eur J Cancer 1995; 31: 178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veale D, Kerr N, Gibson G et al. . The relationship of quantitative epidermal growth factor receptor expression in non-small cell lung cancer to long term survival. Br J Cancer 1993; 68: 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pirker R, Pereira JR, Szczesna A et al. . Cetuximab plus chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (FLEX): an open-label randomised phase III trial. Lancet 2009; 373: 1525–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li S, Kussie P, Ferguson KM. Structural basis for EGF receptor inhibition by the therapeutic antibody IMC-11F8. Structure 2008; 16: 216–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu M, Zhang H, Jimenez X et al. . Identification and characterization of a fully human antibody directed against epidermal growth factor receptor for cancer therapy. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 163. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paz-Ares L, Mezger J, Ciuleanu TE et al. . Necitumumab plus pemetrexed and cisplatin as first-line therapy in patients with stage IV non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (INSPIRE): an open-label, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 328–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thatcher N, Hirsch FR, Luft AV et al. . Necitumumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin versus gemcitabine and cisplatin alone as first-line therapy in patients with stage IV squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (SQUIRE): an open-label, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 763–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meert AP, Martin B, Delmotte P et al. . The role of EGF-R expression on patient survival in lung cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2002; 20: 975–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheng J, Yang YP, Zhao YY et al. . The efficacy of combining EGFR monoclonal antibody with chemotherapy for patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis from 9 randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015; 94: e1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dacic S, Flanagan M, Cieply K et al. . Significance of EGFR protein expression and gene amplification in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 2006; 125: 860–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirsch FR, Herbst RS, Olsen C et al. . Increased EGFR gene copy number detected by fluorescent in situ hybridization predicts outcome in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with cetuximab and chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 3351–3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pirker R, Pereira JR, von Pawel J et al. . EGFR expression as a predictor of survival for first-line chemotherapy plus cetuximab in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: analysis of data from the phase 3 FLEX study. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.