Abstract

Background and Purpose

Signalling through phospholipase C (PLC) controls many cellular processes. Much information on the relevance of this important pathway has been derived from pharmacological inhibition of the enzymatic activity of PLC. We found that the most frequently employed PLC inhibitor, U73122, activates endogenous ionic currents in widely used cell lines. Given the extensive use of U73122 in research, we set out to identify these U73122‐sensitive ion channels.

Experimental Approach

We performed detailed biophysical analysis of the U73122‐induced currents in frequently used cell lines.

Key Results

At concentrations required to inhibit PLC, U73122 modulated the activity of transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) channels through covalent modification. U73122 was shown to be a potent agonist of ubiquitously expressed TRPM4 channels and activated endogenous TRPM4 channels in CHO cells independently of PLC and of the downstream second messengers PI(4,5)P2 and Ca2+. U73122 also potentiated Ca2 +‐dependent TRPM4 currents in human Jurkat T‐cells, endogenous TRPM4 in HEK293T cells and recombinant human TRPM4. In contrast to TRPM4, TRPM3 channels were inhibited whereas the closely related TRPM5 channels were insensitive to U73122, showing that U73122 exhibits high specificity within the TRPM channel family.

Conclusions and Implications

Given the widespread expression of TRPM4 and TRPM3 channels, these actions of U73122 must be considered when interpreting its effects on cell function. U73122 may also be useful for identifying and characterizing TRPM channels in native tissue, thus facilitating the analysis of their physiology.

Abbreviations

- Ci‐VSP

Ciona intestinalis voltage‐sensing phosphatase

- IP3

inositol‐1,4,5‐trisposphate

- PI5K

PI(4)P‐5‐kinase

- PI(4,5)P2

phosphatidylinositol‐(4,5)‐bisphosphate

Tables of Links

| TARGETS | |

|---|---|

| Voltage‐gated ion channels a | Enzymes b |

| Kv7.2 (KCNQ2) channel | PLCβ |

| TRPM3 channel | |

| TRPM4 channel | |

| TRPM5 channel |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Southan et al., 2016) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 (a,bAlexander et al., 2015a, 2015b).

Introduction

Phospholipase C (PLC) catalyses the hydrolysis of membrane‐associated phosphatidylinositol‐(4,5)‐bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2), thereby generating the important second messengers diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol‐1,4,5‐trisposphate (IP3). It is well established that this canonical signalling cascade controls many cellular processes including the activity of membrane proteins, membrane recruitment of enzymes and signalling molecules, reorganization of the cytoskeleton and contraction of smooth muscle cells. Considerable knowledge about the contribution of PLC to these processes has been derived from pharmacological inhibition of its enzymatic activity. Among the few established PLC antagonists, U73122 is most frequently employed, when pharmacological inhibition of PLC is the experimental goal (Bleasdale et al., 1990; Smith et al., 1990). U73122 has been utilized extensively to probe PLC signalling in cells of the immune system (Heissmeyer et al., 2004), in neurons (e.g. Xiang et al., 2002) and in cardiomyocytes (Kobrinsky et al., 2000; Schiekel et al., 2013), among many other cell types. U73122 has also been used to analyse the PI(4,5)P2‐dependence of ion channels during activation of the PLC pathway in native tissues and in heterologous expression systems (Horowitz et al., 2005; Schiekel et al., 2013; Richter et al., 2014).

U73122 is an N‐substituted maleimide, which alkylates biological nucleophils (including cysteine residues) covalently conjugating the compound to the protein (Supporting Information Fig. S1A) (Smith et al., 1990; Horowitz et al., 2005). U73122 most probably inhibits PLC through such alkylation of cysteine residues (Bleasdale et al., 1990; Smith et al., 1990; Wilsher et al., 2007), but direct experimental evidence for this mechanism is not available. In support of the alkylation of PLC, the inactive structural analogue U73343 is the most widely used negative control for U73122, as the maleimide is substituted with a non‐reactive succinimide (Supporting Information Fig. S1A) (Smith et al., 1990). Several side effects of U73122 at concentrations required to inhibit PLC (5–10 μM; Bleasdale et al., 1990; Smith et al., 1990; Horowitz et al., 2005) have been reported raising serious concerns about the use of the compound as an experimental PLC inhibitor. Importantly, U73122 activates ion channels with yet unknown molecular identity in a variety of cell types (Mogami et al., 1997; Muto et al., 1997). U73122 also reduces Ca2 + influx through direct actions on Ca2 + channels or indirectly by reducing the driving force for Ca2 + entry, that is, through activation of ion channels causing membrane potential depolarization (Berven and Barritt, 1995; Macrez‐Lepretre et al., 1996). Furthermore, U73122 was shown to inhibit K+ channels (Cho et al., 2001; Klose et al., 2008; Sickmann et al., 2008) and to induce the release of Ca2 + from intracellular stores into the cytoplasm in a PLC‐independent manner (Mogami et al., 1997; Muto et al., 1997; Macmillan and McCarron, 2010).

Transient receptor potential melastatin 4 (TRPM4) ion channel subunits form ubiquitously expressed Ca2 +‐activated, non‐selective cation channels that are impermeable to Ca2 + ions (reviewed in Mathar et al., 2014a). Gating of TRPM4 channels depolarises the membrane potential to activate voltage‐gated ion channels and to modulate ion flux, in particular entry of Ca2 + in a huge variety of different cell types (Launay et al., 2002; Demion et al., 2007; Vennekens et al., 2007; Barbet et al., 2008; Kruse et al., 2009; Simard et al., 2013; Mathar et al., 2014b). Ca2 + is the only known ligand of TRPM4 (Launay et al., 2002), but the Ca2 + sensitivity of the channels is further increased by PI(4,5)P2 or decavanadate (Nilius et al., 2004; Nilius et al., 2006). Until now, specific TRPM4 channel openers were not available.

It has been suggested that PLC regulates TRPM4 through its constitutive activity and receptor‐induced activation by limiting the availability of PI(4,5)P2 to the channels (Nilius et al., 2006). Positive regulation by PI(4,5)P2 predicts that inhibition of PLC (for example, by U73122) enhances TRPM4 activity as reported previously (Nilius et al., 2006). We find indeed that U73122 activates TRPM4 channels, but we demonstrate that this happens without the involvement of PLC or the downstream second messengers PI(4,5)P2 and Ca2 +. Rather, U73122 is a potent, possibly direct agonist of endogenous and recombinant TRPM4 that activates the channel through covalent modification. In contrast to TRPM4 channels and the expectations arising from the reported effects of PI(4,5)P2 and the regulation through PLC (Oberwinkler and Philipp, 2014; Badheka et al., 2015; Toth et al., 2015), U73122 inhibits the function of TRPM3 channels. It does not, however, affect the closely related TRPM5 channels. Given the ubiquitous expression of TRPM4 channels and the diverse expression profile of TRPM3 channels (Oberwinkler and Philipp, 2014), these findings must be considered when U73122 is used to inhibit PLC. However, these findings suggest that U73122 can be used to the experimenter's advantage to identify members of the TRPM channel family in native tissue, to address the physiology of these channels or to screen for other pharmacological agents influencing these channels, for example, more effective inhibitors of TRPM4 channels.

Methods

Cell culture and transfection

Chinese hamster vary (CHO) dhFR− cells were kept in MEM Alpha Medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (pen/strep) (all Invitrogen GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany). Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells were cultured in DMEM‐Glutamax with 10% FCS, 1% pen/strep, 1% sodium pyruvate and 1% MEM non‐essential amino acids solution (Invitrogen GmbH). G418 (geneticin; 1%, Sigma‐Aldrich, Munich, Germany) was added to the medium of HEK293 cells stably expressing myc‐tagged mouse TRPM3α2 (HEKmTRPM3, UniProt accession number: Q5F4S8) (Frühwald et al., 2012). HEKmTRPM3 cells were cultured without pen/strep. Jurkat T‐cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% pen/strep, 50 μM 2‐mercaptoethanol and 2 mM L‐glutamine (Invitrogen GmbH and Sigma‐Aldrich). All cells were kept in a humidified atmosphere at 5% CO2 and 37°C. For experiments, cells were cultured on glass cover slips that for HEK and Jurkat T‐cells were coated with poly‐d‐lysine or poly‐l‐lysine (both Sigma‐Aldrich). All experiments were performed at room temperature (22–25°C). Cells were transiently transfected with jetPEI (Polyplus Transfection, Illkirch, France), and all experiments were performed 24–48 h after transfection. The expression vectors used were as follows: hTRPM4‐pcAGGSM2 and hTRPM4‐pEGFP‐N1 (UniProt accession number: Q8TD43), mTRPM5‐pcDNA3.1 (Q9JJH7), Ciona intestinalis voltage‐sensing phosphatase (Ci‐VSP)‐pRFP‐C1 and Ci‐VSP(C363S)‐pRFP‐C1 (Q4W8A1), pRFP‐C1‐PI(4)P‐5‐kinase (PI5K) (P70181), human muscarinic receptor 1 (hM1 receptor)‐pSGHV0 (Q96RH1), KCNQ2‐pBK‐CMV (Kv7.2, O43526) and pEGFP‐C1 (Addgene, Teddington, UK). The point mutation D984A in hTRPM4 was introduced with the QuickChange II XL Site‐Directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Electrophysiological recordings

Electrophysiological recordings were performed in the whole‐cell configuration with an Axopatch 200B amplifier in voltage‐clamp mode (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA, USA). Data were acquired with an ITC‐18 interface and controlled by patchmaster software (both HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht, Germany). Recordings were low‐pass filtered at 2 kHz, currents were sampled at 5 kHz and were elicited by 660 ms‐voltage ramps every 5 s. The voltage‐dependent 5‐phosphatase of Ciona intestinalis (Ci‐VSP) was activated with a 30 s voltage step from the holding potential of −60 to +80 mV (Halaszovich et al., 2009). Whole‐cell currents are presented as normalized to the cell capacitance (current density; pA/pF) or as normalized current I/IStart. Series resistance (Rs) typically was below 6 MΩ and compensated for throughout the recordings (80–90%). Liquid junction potentials were not compensated for (approximately −4 mV). The extracellular solution for most electrophysiological experiments contained (standard extracellular solution; mM) 144 NaCl, 5.8 KCl, 1.3 CaCl2, 0.9 MgCl2, 0.7 NaH2PO4, 10 HEPES and 5.6 d‐glucose, pH 7.4 (with NaOH), 305–310 mOsm·kg−1. In some experiments, NaCl or CaCl2 was substituted by N‐methyl‐d‐glucamine (NMDG; Sigma‐Aldrich) (Figure 1D–G). The extracellular solution with highest CaCl2 concentration contained (mM) 20 NMDG, 10 d‐glucose, 10 HEPES and 100 CaCl2, pH 7.4 (with NaOH), 307–310 mOsm·kg−1 (Figure 1F and G). Borosilicate glass patch pipettes (Sutter Instrument Company, Novato, CA, USA) had an open pipette resistance of 2–3 MΩ after back‐filling with intracellular solution. Standard intracellular solution contained (mM) 135 KCl, 2.41 CaCl2 (100 nM free Ca2 +), 3.5 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, 5 EGTA, 2.5 Na2ATP, pH 7.3 (with KOH), 290–295 mOsm·kg−1. From this solution, CaCl2 was omitted, and 20 mM 1,2‐bis(2‐aminophenoxy)ethane‐N,N,N ′,N′‐tetraacetic acid (BAPTA; Sigma‐Aldrich) was added to the standard intracellular solution (Figure 4, 0 Ca2 +). β,γ‐Methyleneadenosine 5′‐triphosphate disodium salt (2.276 mM; AMP‐PCP; Sigma‐Aldrich) was used to replace Na2ATP (Figure 3B, 0 ATP). The intracellular solution for recordings of mTRPM3 and mTRPM5 channels (Figure 6) contained (mM) 110 CsCl, 20 tetraethylammonium chloride, 3.5 MgCl2, 2.5 Na2ATP, 2.41 CaCl2, 5 HEPES, 5 EGTA, pH 7.3 (with CsOH), 290–295 mOsm·kg−1. For Jurkat T‐cells (Figure 2F), the intracellular solution contained (mM) 140 KCl, 8 NaCl, 2.9 CaCl2 (free Ca2 + 100 nM), 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 BAPTA, pH 7.3 (with KOH), 290–295 mOsm·kg−1 (Launay et al., 2004). Concentrations of free Ca2 + were calculated with WEBMAXC STANDARD. For excised inside‐out patches (Figure 5A), pipette resistance was between 1 and 1.5 MΩ, and pipettes were filled with standard extracellular solution. Excised patches were perfused with intracellular solution containing (mM) 135 KCl, 2.41 CaCl2, 3.5 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, 5 EGTA, pH 7.3 (with KOH), 290–295 mOsm·kg−1.

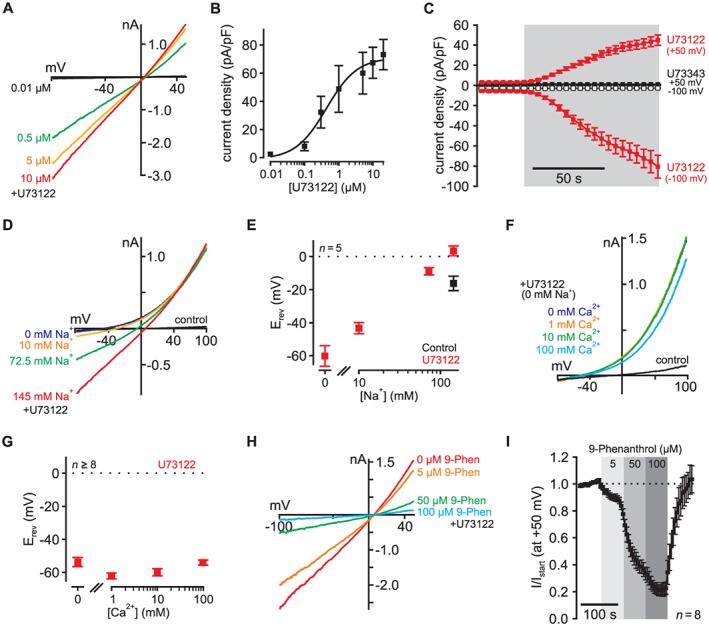

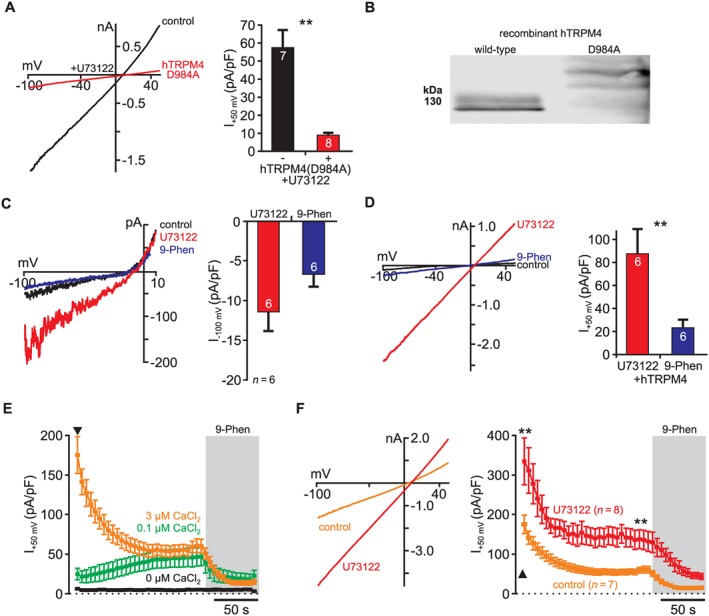

Figure 1.

U73122 activates endogenous cation currents in CHO cells. (A) In non‐transfected CHO cells, U73122 activated endogenous currents with a linear current–voltage relationship in a dose‐dependent manner with (B) an EC50 of approximately 0.44 μM and a Hill coefficient of about 0.96 (each data point n > 8 independent cells, current amplitudes analysed at +50 mV). (C) In response to 5 μM U73122, inward and outward currents developed within seconds and reached stable amplitudes in 1 to 2 min (red; n = 30). The inactive analogue U73343 (5 μM) did not activate endogenous currents in CHO cells (black; n = 7) (grey inserts indicate application of the compounds). (D) U73122‐induced inward currents were dependent on Na+ and were abolished largely in absence of extracellular Na+ (representative recording). (E) The reversal potentials (Erev) of these currents changed with extracellular Na+ concentrations and were 6.7 ± 3.2 mV (145 mM Na+), −9.2 ± 2.4 mV (72.5 mM Na+), −43.2 ± 3.6 mV (10 mM Na+) and −60.2 ± 6.5 mV (0 mM Na+) (n = 5). (F) and (G) In the presence of U73122, inward currents and reversal potentials did not depend on the extracellular Ca2 + concentration (n > 8). (H)–(I) The TRPM4‐specific antagonist 9‐phenanthrol dose‐dependently and reversibly inhibited U73122‐sensitive currents in CHO cells. In these recordings, 9‐phenanthrol was applied after U73122 (5 μM; n = 8).

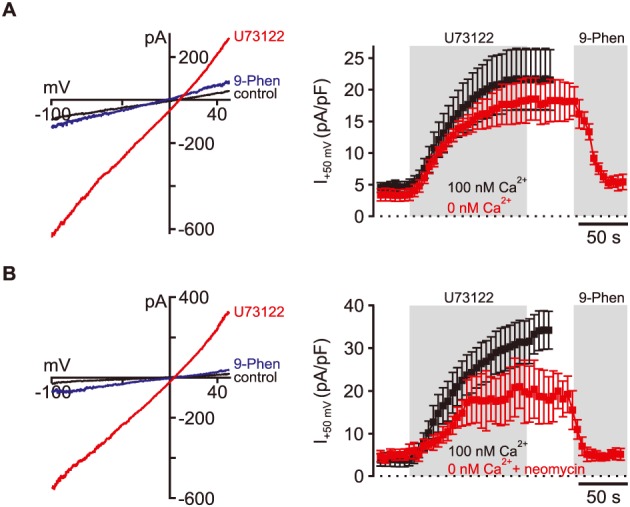

Figure 4.

U73122 activates TRPM4 in the absence of intracellular Ca2 +. In CHO cells dialysed with (A) 20 mM BAPTA (0 CaCl2) and (B) 20 mM BAPTA together with 1 mM neomycin, U73122‐sensitive currents were indistinguishable from control cells with 100 nM free CaCl2 and physiological PI(4,5)P2 levels (no statistically significant difference). Thus, intracellular Ca2 + and membrane PI(4,5)P2 were not required for U73122‐dependent activation of endogenous TRPM4 in CHO cells. (A and B: left, representative recordings; right, summary of recordings; 5 μM U73122). (A) 100 nM Ca2 +: n = 11; 0 nM Ca2 +: n = 16; (B) 100 nM Ca2 +: n = 5; 0 nM Ca2 + + neomycin: n = 16.

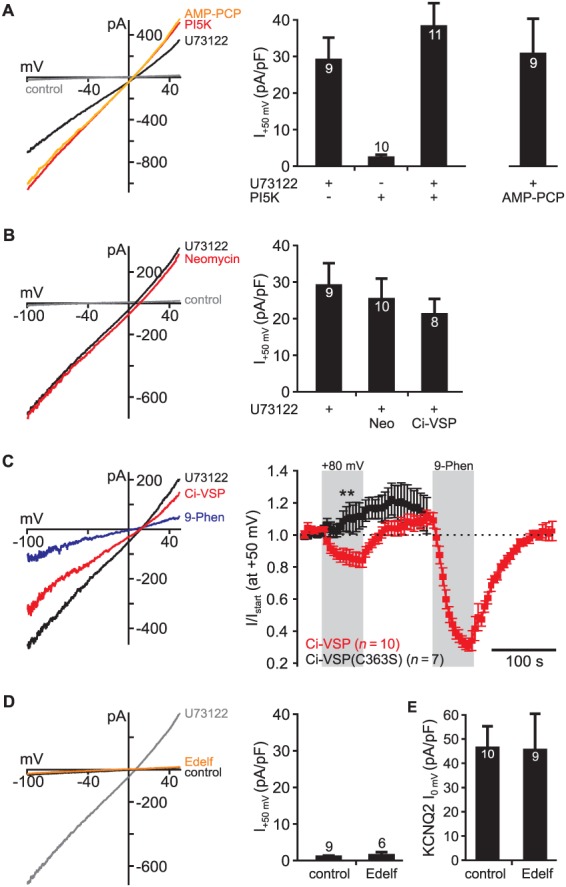

Figure 3.

U73122‐dependent activation of TRPM4 channels does not involve PLC and PI(4,5)P2. (A) Increasing cellular PI(4,5)P2 levels through overexpression of PI5K type‐1 β did not activate endogenous channels in CHO cells (n = 10). In cells expressing PI5K, U73122‐activated TRPM4 currents were similar to currents in control cells without PI5K (−PI5K: n = 9; +PI5K: n = 11). When endogenous PI kinases were inhibited through dialysis of cells with the non‐hydrolysable ATP analogue AMP‐PCP (2.3 mM), U73122‐induced currents were also indistinguishable from controls (control: n = 9). (B) Reducing cellular PI(4,5)P2 levels before application of U73122 through dialysis of cells with neomycin (1 mM, 4 min before application of U73122; n = 10) or through activation of voltage‐dependent PI(4,5)P2 5‐phosphatase Ci‐VSP (n = 8) did not alter U73122‐dependent current amplitudes in CHO cells (n = 9). To reduce PI(4,5)P2 levels prior to treatment, Ci‐VSP was activated for 1 min at +80 mV before application of U73122 in these experiments. Note that these cells were kept at +80 mV during U73122 application to maintain low PI(4,5)P2 levels. Thus, U73122 activated TRPM4 despite reduced PI(4,5)P2 concentration (note that currents in A and B were compared with the same batch of control cells). (C) In line, activation of Ci‐VSP after application of U73122 only slightly reduced U73122‐activated TRPM4 currents indicating that the channel was largely insensitive to PI(4,5)P2 depletion (n = 10). Note that this slight inhibition was absent in cells co‐expressing catalytically dead Ci‐VSP(C363S) (n = 7) (U73122 was applied at 5 μM in all experiments presented in A–C; 100 μM 9‐phenanthrol). (D) Treatment of CHO cells with the PLC inhibitor edelfosine (10 μM; 30 min) did not induce endogenous currents (n = 6), and (E) treatment with edelfosine did not alter KCNQ2 (Kv7.2)‐mediated currents indicating that inhibition of PLC did not change cellular PI(4,5)P2 levels (control: n = 10; Edelf: n = 9). Control experiments for experimental manipulations are presented in Supporting Information Fig. S2.

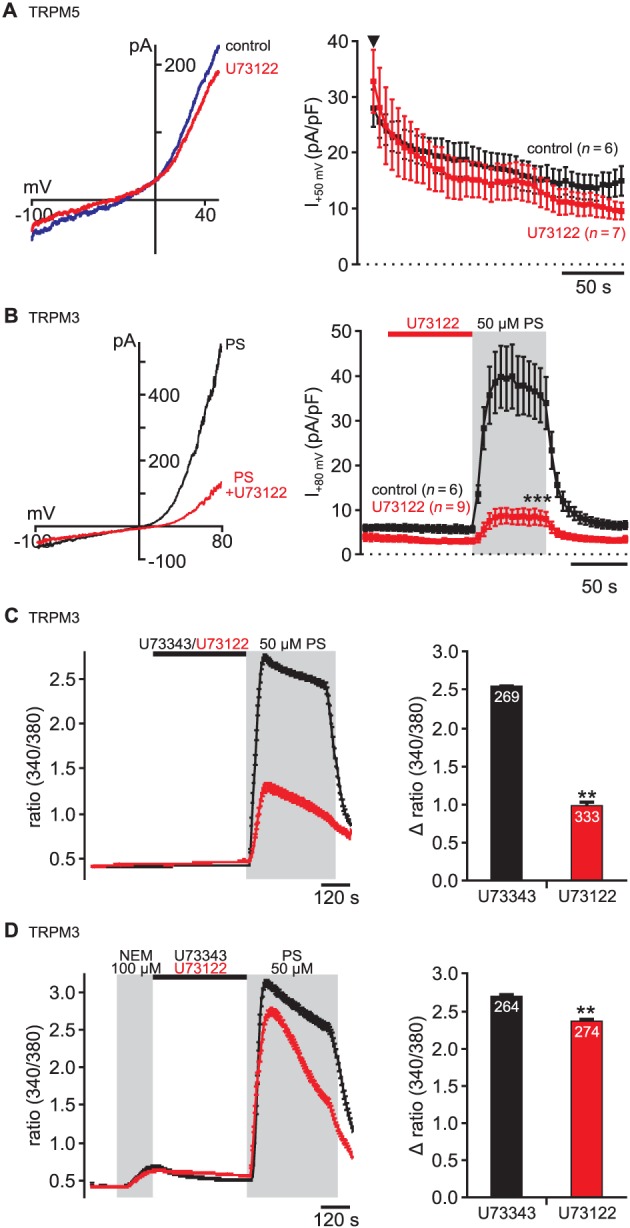

Figure 6.

U73122 does not affect TRPM5, but inhibits TRPM3 channels. (A) Application of U73122 did not affect TRPM5‐mediated currents evoked by 1 μM intracellular Ca2 + (control: n = 6; U73122: n = 7) in HEK293T cells transiently expressing murine TRPM5 (cf. Supporting Information Fig. S4). U73122 (5 μM) was applied for 60 s before establishment of the whole‐cell configuration and throughout the recording. The arrowhead indicates establishment of the whole‐cell configuration. (B) and (C) The steroid pregnenolone sulphate (PS; 50 μM) induced (B) outwardly rectifying currents and (C) Ca2 + transients in HEK293T cells stably expressing murine TRPM3 channels (HEKmTRPM3). TRPM3‐mediated responses were strongly reduced by pre‐application of U73122. In contrast, U73343 did not affect the activity of TRPM3 channels [in (B) 5 μM U73122, in (C) 3 μM U73122 or U73343]. (D) Pre‐application of NEM (100 μM) attenuated the inhibition of TRPM3 channels by U73122 indicating that the inhibition of TRPM3 channels might be caused by covalent modification. (B) Control: n = 6; U73122: n = 9; (C) U73343: e = 269, n = 5; U73122: e = 333, n = 6; (D) U73343: e = 264, n = 5; U73122: e = 274, n = 5.

Figure 2.

U73122 activates endogenous and recombinant TRPM4 channels. (A) Overexpression of human TRPM4(D984A) with a loss‐of‐function mutation in the channel pore abolished U73122‐dependent current activation in CHO cells most probably through dominant‐negative inhibition (left, representative recordings; right, summary of recordings). These findings indicated that endogenous TRPM4 channels are the target of U73122 in CHO cells (−TRPM4(D984A): n = 7; +TRPM4(D984A9): n = 8). (B) Western blots demonstrated strong expression of TRPM4(D984A) in CHO cells. Note that only hTRPM4(D984A) was expressed as GFP fusion protein and thus is approximately 30 kDa larger than the wild‐type protein. (C) In HEK293T cells, U73122 activated small, but 9‐phenanthrol sensitive endogenous currents (n = 6; left, representative recordings; right, summary of recordings). Standard intracellular and extracellular solutions (cf. Methods) were used in these experiments. Because HEK293T cells generate considerable voltage‐dependent outward currents under the experimental conditions employed, inward currents in response to U73122 are presented. (D) In HEK293T cells, overexpressing human TRPM4 channels, U73122 activated large and 9‐phenanthrol sensitive currents demonstrating that also recombinant TRPM4 channels are sensitive to U73122 (n = 6). (E) Dialysis of human Jurkat T‐cells with different Ca2 + concentrations via the patch pipette induced Ca2 +‐dependent and 9‐phenanthrol sensitive currents through endogenous TRPM4 channels (0 μM Ca2 +, n = 5; 0.1 μM Ca2 +, n = 5; 3 μM Ca2 +, n = 8). (F) Pre‐application of U73122 in the ‘on‐cell’ configuration before rupture of the membrane patch potentiated TRPM4‐mediated currents in Jurkat T‐cells. In these experiments, TRPM4 was activated with 3 μM intracellular Ca2 +. The arrowhead in (E) and (F) indicates establishment of the whole‐cell configuration. In all experiments, U73122 was applied at 5 μM (control: n = 7; U73122: n = 8). 9‐Phenanthrol was applied at a concentration of 100 μM in all recordings.

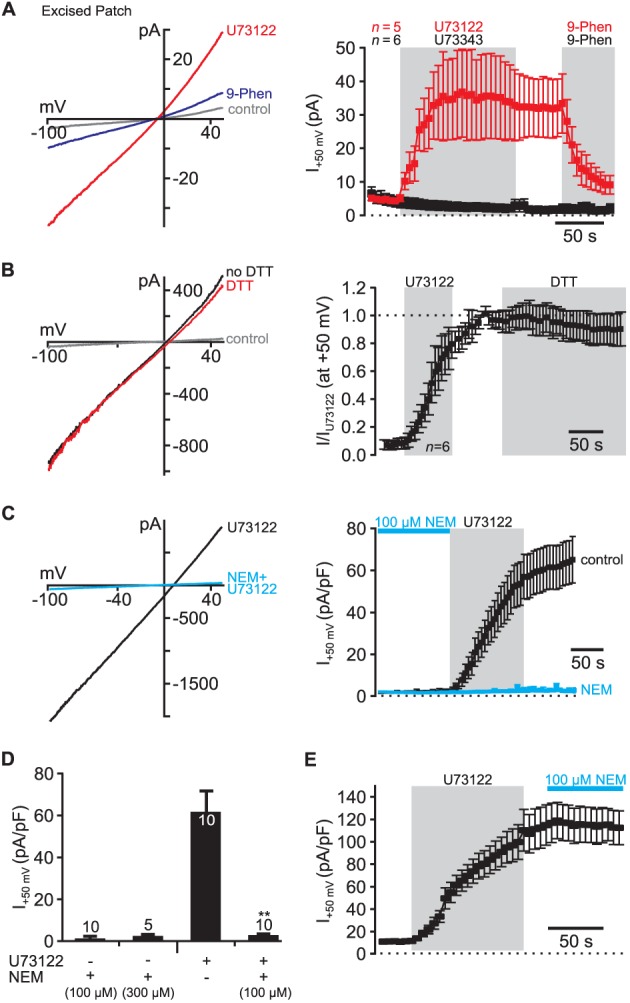

Figure 5.

U73122 activates TRPM4 through covalent modification. (A) U73122 activated TRPM4 channels in membrane patches excised from non‐transfected CHO cells indicating that soluble cytoplasmic factors are not required for current induction (U73122: n = 5; U73343: n = 6). Note that membrane patches were excised into intracellular solution without ATP. In contrast, U73343 did not induce any currents in excised membrane patches. 9‐Phenanthrol was applied at a concentration of 100 μM in these experiments. (B) In whole‐cell patch clamp recordings, U73122‐induced currents were insensitive to reduction by dithiothreitol (DTT, 5 mM), strongly indicating a chemically stable modification through alkylation (n = 6). Currents were normalized to the maximal amplitude of the U73122‐induced currents (I/IU73122; indicated by dashed line). (C) and (D) Application of NEM (100 μM: n = 10; 300 μM: n = 5), another alkylating reagent, did not activate endogenous TRPM4 channels in CHO cells. However, pre‐application of NEM abolished activation of TRPM4 channels by U73122 (n = 10; whole‐cell patch clamp) indicating that NEM occluded the interaction site of U73122. (E) In contrast when applied after U73122, NEM (100 μM) did not inhibit U73122‐dependent currents in CHO cells and thus did not affect the activity of endogenous TRPM4 channels (n = 7). 5 μM U73122 was used in all recordings (control experiments for the substances employed are presented in Supporting Information Fig. S3).

Calcium imaging

Ca2 + imaging experiments were performed as described previously (Drews et al., 2014). HEKmTRPM3 cells (expressing splice variant TRPM3α2, from now on TRPM3) cultured on poly‐l‐lysine (Sigma‐Aldrich) coated glass coverslips were incubated for 30 min with 5 μM Fura 2‐AM in growth medium at room temperature (Biotrend Chemikalien GmbH, Köln, Germany). Then, cells were transferred to a closed recording chamber (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA) and constantly perfused with extracellular solution (in mM: 145 NaCl, 10 CsCl, 2–5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 d‐glucose, pH 7.2 (with NaOH), 315–325 mOsm·kg−1). On an inverted microscope (TE2000 with 10x SFluor; N.A. 0.5; Nikon Corporation, Düsseldorf, Germany), every 5 s a pair of images was taken at 510 nm wavelength with a Retiga‐Exi camera (Qimaging, Surrey, BC, Canada) during alternate excitation with light of 340 and 380 nm wavelengths using a motorized filter wheel (Ludl, Hawthorne, NY, USA). The background fluorescence was subtracted for each picture individually, and ratio images (340 or 380 nm) were calculated pixel by pixel (after thresholding to exclude pixels with low intensity values). This was carried out with ImageJ using a modified version of the ‘ratio plus’ plug‐in. Data from regions of interest corresponding to single cells were averaged, and for calculating changes in ratio values (Δratio), baseline values measured in the absence of agonists or antagonists were subtracted.

Western blots

Cells were washed twice with ice‐cold PBS, and proteins were extracted using ice‐cold PBS containing 1% Triton X‐100 (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) and a protease inhibitor mix (1 mM PMSF, 1 μg·mL−1 pepstatin, 5 μg·mL−1 leupeptin, 5 μg·mL−1 antipain, 1 μg·mL−1 aprotinin and 100 μg·mL−1 trypsin inhibitor; all from Carl Roth). Cell lysates were homogenized by pipetting up and down 10 times and kept on ice for 30 min followed by centrifugation for 15 min at 13.000× g and 4°C to remove debris and nuclei. Protein concentrations in the supernatants were determined using Roti®‐Quant (Carl Roth) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two volumes from each cell extract were mixed with one volume of sample buffer (120 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, 150 mM DTT, 6% SDS, 15% glycerol and 0.015% bromphenol blue; all from Carl Roth). Samples were heated to 37°C for 30 min before layering onto polyacrylamide slab gels containing 0.1% SDS and protein separation by one‐dimensional electrophoresis according to Laemmli (Laemmli, 1970). Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare, Solingen, Germany) and blocked with 5% milk (Carl Roth) in PBS overnight at 4°C. Nitrocellulose membranes were incubated with primary anti‐human‐TRPM4 (1:500; Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) and secondary IRDye® 800CW labelled anti‐rabbit (1:10 000; LI‐COR Biosciences GmbH, Bad Homburg vor der Höhe, Germany) antibodies in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (Carl Roth) at room temperature and visualized with the ODYSSEY® Sa infrared imaging system (LI‐COR Biosciences).

U73122/U73343

The 5 mM stock solutions of U73122 (1‐[6‐[[(17β)‐3‐methoxyestra‐1,3,5(10)‐trien‐17‐yl]amino]hexyl]‐1H‐pyrrole‐2,5‐dione) or U73343 (1‐[6‐[[(17β)‐3‐methoxyestra‐1,3,5(10)‐trien‐17‐yl]amino]hexyl]‐2,5‐pyrrolidinedione; both Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, United Kingdom or Sigma‐Aldrich) in DMSO were stored at −20°C in single use aliquots. U73122 induced currents in virtually every CHO cell tested, but current amplitudes were strongly dependent on the storage duration of U73122 at −20°C. Because U73122 gradually lost activity with time, final concentrations were prepared from the stock solution immediately before the experiment, and solutions were discarded after 30 min. Controls were recorded for each set of experiments, and identical U73122 solutions were used for each experimental condition (untreated controls and U73122‐treated cells).

Materials

DTT (Fisher Scientific‐Germany GmbH, Schwerte, Germany), edelfosine (ET‐18‐OCH3; Sigma‐Aldrich), hydrogen peroxide solution (H2O2; Sigma‐Aldrich), neomycin sulphate (Carl Roth), N‐ethylmaleimide (NEM; Sigma‐Aldrich), oxotremorine‐M (Biotrend Chemikalien GmbH), pregnenolone sulphate (PS; Sigma‐Aldrich or Steraloids, Newport, RI, USA) and 9‐phenanthrol (R&D Systems GmbH, Wiesbaden‐Nordenstadt, Germany). NEM, 9‐phenanthrol and PS were prepared as stock solutions in DMSO, kept at −20°C and diluted into physiological solutions prior to experiments. 9‐Phenanthrol was applied at a concentration of 100 μM unless stated otherwise. The final concentration of DMSO was below 1% in all solutions.

Data analysis

The data and statistical analysis in this study comply with the recommendations on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2015). Patch clamp recordings were analysed with PATCHMASTER software and IgorPro (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). Current amplitudes were measured during a 200 ms voltage step at the indicated voltages before and after voltage ramps. Responses were fitted to a Hill equation with I/Ib = Ib + (Imax−Ib)/(1 + (EC50/[S])nH), where I is the (normalized) current, Ib and Imax denote minimal and maximal currents at low and high drug concentrations, EC50 is the concentration at the half maximal effect, [S] is the drug concentration and nH is the Hill coefficient (Leitner et al., 2012). Ca2 + imaging experiments were analysed with ImageJ and Origin (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, USA).

Compliance with design and statistical analysis requirements

The isolated cells under investigation were randomly assigned to the different treatment groups. Data recordings and the analysis for experiments presented in Figures 2A, D and 3 were performed in a blinded manner. Single recordings were normalized to base line values individually to account for baseline variations between cells. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's two‐tailed t‐test/Wilcoxon‐Mann–Whitney test, and when appropriate comparisons between multiple groups were performed with ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test. Significance was assigned at P ≤ 0.01 (**P ≤ 0.01). Data subjected to statistical analysis had an n value of more than five per group, and data are presented as mean ± SEM. In electrophysiological experiments, n represents the number of individual cells and accordingly the number of independent experiments (no pseudo‐replication) (Figures 1–5 and 6A–B; Supporting Information S1‐S4). In Ca2 + imaging experiments, e represents the number of measured cells, and n denotes the number of independent experiments (Figure 6C and D). In these imaging experiments, many cells were recorded as replicates within the field of vision of the objective to ensure the reliability of an individual experiment.

Results

U73122 activates endogenous cationic currents in CHO cells

We found that large whole‐cell currents with a linear current–voltage relationship (under physiological ionic conditions) appeared in CHO cells when applying U73122 (Figure 1, chemical structure of U73122 is shown in Supporting Information Fig. S1A). Currents developed in a concentration‐dependent manner with an EC50 of approximately 0.44 μM and a Hill coefficient of about 0.96 (Figure 1A and B, Supporting Information Fig. S1B). However, due to the low stability of U73122 in solution, the irreversibility of current induction and incompatibility of higher U73122 concentrations with whole‐cell patch clamp, these values may constitute only approximations of the actual dose‐response relationship. Current amplitudes induced by 5 μM U73122 were 49.4 ± 6.4 pA/pF and −89.5 ± 12.0 pA/pF at +50 and −100 mV, respectively (n = 30; Figure 1C). Following application of U73122, the currents appeared within 1 to 2 min (5 μM U73122: time to 90% of maximum current at +50 mV: 68.9 ± 3.2 s, n = 30; Figure 1C), and current amplitudes were constant over at least 20 min even after removal of U73122 (not shown). In contrast, no such currents were induced by the structural analogue U73343 that is widely used as a negative control for U73122 (Figure 1C).

In order to identify the U73122‐sensitive channels, we analysed the permeation properties of the currents. The amplitude of the U73122‐induced inward currents was dependent on the extracellular Na+ concentration, and these currents were largely abolished in the absence of extracellular Na+ (Figure 1D and E). Reversal potentials changed from 6.7 ± 3.2 mV with 145 mM Na+ to −60.2 ± 6.5 mV with 0 mM Na+ (n = 5; Figure 1E). In contrast, currents and reversal potentials were insensitive to changes in extracellular Ca2 + (Figure 1F and G). Taken together, U73122‐induced endogenous currents in non‐transfected CHO cells are largely carried by monovalent cations.

Interestingly, these biophysical properties agree well with the characteristics of TRPM4 channels (c.f. Launay et al., 2002). Because CHO cells are known to express these channels endogenously (Yarishkin et al., 2008), we hypothesized that U73122 was an agonist of TRPM4 channels. In a first attempt to probe this hypothesis, we tested the sensitivity of the U73122‐activated currents to the TRPM4‐specific inhibitor 9‐phenanthrol. Figures 1H and I show that 9‐phenanthrol inhibited U73122‐activated currents reversibly and in a dose‐dependent manner with an IC50 of 24.9 ± 3.23 μM (n = 8; Supporting Information Fig. S1C) agreeing well with the reported 9‐phenanthrol sensitivity of TRPM4 channels (17 μM in Grand et al., 2008). To analyse whether the cells expressed functional Ca2 +‐activated ion channels endogenously, we dialysed non‐transfected CHO cells with 500 μM free Ca2 + through a patch pipette. In these cells, sizeable Ca2 +‐activated currents developed that were also inhibited by 9‐phenanthrol (100 μM) indicating that these currents were mediated by TRPM4 channel subunits (Supporting Information Fig. S1D).

U73122 activates endogenous and recombinant TRPM4 channels

To further elucidate whether U73122‐sensitive currents in CHO cells were mediated by TRPM4, we overexpressed TRPM4(D984A), a dominant‐negative TRPM4 mutant carrying a loss‐of‐function mutation in the channel pore (Nilius et al., 2005). As shown in Figure 2A, U73122‐activated currents were largely abolished in cells expressing TRPM4(D984A)‐GFP compared with control cells expressing only GFP. Given the robust expression of TRPM4(D984A) (Figure 2B), these findings indicated that TRPM4(D984A) co‐assembled with endogenous U73122‐sensitive channel subunits into non‐functional heteromeric channels. This suggested that the endogenous U73122‐activated channels were either TRPM4 or closely related TRPM channels.

Similar to CHO cells, HEK293T cells were shown to express endogenous TRPM4 channels (Amarouch et al., 2013). U73122 activated currents sensitive to 9‐phenanthrol (100 μM) in HEK293T cells, but these currents were much smaller than in CHO cells (Figure 2C). Because the induced currents were so small, we could utilize HEK293T cells as an expression system to analyse whether recombinant TRPM4 channels were sensitive to U73122. Figure 2D shows that application of U73122 to HEK293T cells expressing human TRPM4 channels induced large non‐rectifying currents (87.9 ± 21.7 pA/pF at +50 mV; n = 6) that were inhibited by 9‐phenanthrol (100 μM; Figure 2D). Thus, U73122 activates recombinant (human) TRPM4 unequivocally identifying TRPM4 channels as targets of U73122.

In order to elucidate whether U73122 also activates endogenous TRPM4 in other cell types, we turned to Jurkat T‐cells that are derived from human tissues and have been described as a native expression system for TRPM4 (Launay et al., 2004). In Jurkat T‐cells, TRPM4 forms endogenous Ca2 +‐activated non‐selective cation channels that were shown to constitute necessary modulators of cytokine release. As reported by Launay and colleagues, dialysis of Jurkat T‐cells with increasing Ca2 +‐concentrations (0 Ca2 +, 100 nM Ca2 +, 3 μM Ca2 +) activated large concentration‐dependent currents that desensitized slowly (Figure 2E). These Ca2 +‐activated currents were inhibited by 9‐phenanthrol (100 μM) and thus, also in our hands, were mediated by TRPM4. To determine the sensitivity of TRPM4 to U73122 in Jurkat T‐cells, we applied U73122 (5 μM) in the ‘on‐cell’ configuration before rupture of the membrane patch. This application protocol enabled analysis of TRPM4‐mediated currents immediately after membrane rupture as well as after current desensitisation (cf. Figure 2E). In cells treated with U73122, currents activated by 3 μM Ca2 + were significantly increased compared with control cells (Figure 2F) demonstrating that U73122 also activates TRPM4 channels endogenously expressed in Jurkat T‐cells.

Taken together, these experiments demonstrated that U73122 is a potent agonist of endogenous TRPM4 channels in cell lines derived from various species, including humans, and of recombinant TRPM4.

U73122‐dependent activation of TRPM4 channels does not involve PLC and PI(4,5)P2

We next aimed at understanding how U73122 activates TRPM4 channels. Firstly, we examined whether the action of U73122 on TRPM4 involves the substrate of PLC, PI(4,5)P2. Membrane PI(4,5)P2 concentrations are set by the opposing activities of lipid phosphatases, lipases and PI(4)P‐5‐kinases (PI5K). Provided that the basal activity of PLC is high, sustained activity of these kinases might increase PI(4,5)P2 levels during U73122‐dependent inhibition of PLC. Because PI(4,5)P2 positively modulates TRPM4 channels (Nilius et al., 2006), such U73122‐dependent changes of PI(4,5)P2 might indirectly modulate TRPM4 channel function.

We employed several well‐established tools for experimental manipulation of PI(4,5)P2 levels in living cells (Halaszovich et al., 2009; Leitner et al., 2011) whilst utilizing recombinant KCNQ2 (Kv7.2) channels as PI(4,5)P2 sensors. Because PI(4,5)P2 is essential for KCNQ channel activity, these channels are sensitive indicators for the PI(4,5)P2 concentration of the plasma membrane. KCNQ2 current amplitudes decrease in response to PI(4,5)P2 depletion, and the currents are potentiated when cellular PI(4,5)P2 levels are increased. Thus, KCNQ2 channel activity reliably reports on changes in concentration of PI(4,5)P2 in both directions (Zhang et al., 2003; Suh et al., 2006; Rjasanow et al., 2015).

In a first step, we overexpressed PI5K to increase membrane PI(4,5)P2 (PI5K type‐1β; Li et al., 2005), which was confirmed by pronounced potentiation of KCNQ2 currents (Supporting Information Fig. S2A). However, neither basal currents nor U73122‐activated currents were affected in non‐transfected CHO cells by overexpression of PI5K (Figure 3A). Next, we blocked the activity of endogenous PI5K during U73122‐induced TRPM4 activation by replacement of intracellular ATP with its non‐hydrolysable analogue AMP‐PCP (2.3 mM AMP‐PCP in the patch pipette) (Halaszovich et al., 2009). We dialysed CHO cells with AMP‐PCP for 4 min, sufficient time to abolish PI5K‐mediated PI(4,5)P2 synthesis (Supporting Information Fig. S2C), before the application of U73122 (5 μM). In cells dialysed with AMP‐PCP, U73122‐induced currents were not different from untreated controls (Figure 3A), indicating that increased PI(4,5)P2 levels and kinases, including PI5Ks, are not necessary for U73122‐dependent activation of TRPM4.

We additionally examined whether U73122‐activated currents were affected by diminished PI(4,5)P2 levels. PI(4,5)P2 depletion was achieved via two independent experimental strategies: First, cells were dialysed with the polycation neomycin (1 mM) via in‐diffusion from the patch pipette to reduce the amount of available PI(4,5)P2 through sequestration (Leitner et al., 2011). Second, we employed the genetically encoded, voltage‐sensitive PI phosphatase Ci‐VSP, which reversibly depletes PI(4,5)P2 upon depolarization of the membrane potential (Murata et al., 2005; Halaszovich et al., 2009; Lindner et al., 2011; Rjasanow et al., 2015). Both approaches effectively depleted PI(4,5)P2 as confirmed by robust inhibition of KCNQ2 potassium channels (Supporting Information Fig. S2B and C). When we applied U73122 after complete dialysis of cells with neomycin or during activation of Ci‐VSP (at +80 mV), U73122‐induced currents were indistinguishable from untreated controls (Figure 3B). Thus, U73122‐dependent whole‐cell currents were unaffected by reduced PI(4,5)P2 levels. This was somewhat surprising, as TRPM4 channels have been shown to require PI(4,5)P2 for activation through the physiological ligand Ca2 + (Nilius et al., 2006).

We performed additional experiments using Ci‐VSP to deplete PI(4,5)P2. This time, we activated Ci‐VSP after application of U73122 to estimate the PI(4,5)P2‐dependence of the U73122‐sensitive current from the extent of Ci‐VSP‐dependent current inhibition (Halaszovich et al., 2009; Rjasanow et al., 2015). In these experiments, U73122‐activated currents were attenuated only slightly in response to Ci‐VSP‐mediated PI(4,5)P2 depletion (ICi‐VSP/Istart: 0.85 ± 0.04, n = 10; Figure 3C). In contrast, activation of Ci‐VSP strongly inhibited KCNQ2 channels (ICi‐VSP/Istart: 0.19 ± 0.03, n = 5; Supporting Information Fig. 2C) in line with their high sensitivity to PI(4,5)P2 depletion (Li et al., 2005; Rjasanow et al., 2015). These data demonstrate that TRPM4‐mediated currents induced by U73122 are largely insensitive to physiological changes in membrane PI(4,5)P2. This insensitivity may suggest that either TRPM4 channels exhibit high affinity to PI(4,5)P2 in the presence of U73122 or that channel activation through U73122 does not require PI(4,5)P2.

After having established that changes in PI(4,5)P2 levels are not required for the activation of TRPM4 channels by U73122, we examined whether inhibition of PLC was involved at all. We reasoned that if TRPM4 activation was mediated by inhibition of PLC, then other PLC antagonists should similarly activate TRPM4. However, treatment of CHO cells with the PLC inhibitor edelfosine (10 μM, 30 min; Powis et al., 1992) did not induce any current in CHO cells and thus does not activate TRPM4 channels (Figure 3D). As a control for the efficacy of edelfosine to inhibit PLC under our experimental conditions, we tested its effect on the deactivation of KCNQ2 channels by Gq/PLC‐coupled muscarinic receptors, which is an extensively studied model for PLC signalling (e.g. Zhang et al., 2003). In cells pretreated with edelfosine, PLCβ‐mediated inhibition of KCNQ2 channels was largely impaired (Supporting Information Fig. S2D), confirming efficient inhibition of PLC. We therefore conclude that inhibition of PLC does not suffice to induce TRPM4 currents in CHO cells. In cells treated with edelfosine, KCNQ2‐mediated currents were essentially the same as in control cells (Figure 3E), indicating that PI(4,5)P2 levels were not altered by edelfosine. We thus conclude that inhibition of PLC does not cause increased PI(4,5)P2 levels. These findings are in full agreement with a previous study also reporting that cellular PI(4,5)P2 levels do not change after inhibition of PLC with edelfosine (Horowitz et al., 2005).

Taken together, the activation of TRPM4 by U73122 does not depend on PI(4,5)P2, and inhibition of PLC does not increase PI(4,5)P2 levels in CHO cells. We conclude that activation of TRPM4 channels by U73122 does not involve inhibition of PLC or changes in cellular PI(4,5)P2 concentrations.

U73122 activates TRPM4 in the absence of intracellular Ca2 +

U73122 was previously shown to increase cytoplasmic Ca2 + levels through inhibition of Ca2 + uptake into intracellular stores (Mogami et al., 1997; Macmillan and McCarron, 2010) and via IP3‐mediated Ca2 + release through weak activation of PLC (Horowitz et al., 2005; Klein et al., 2011). Because elevated Ca2 + concentrations are the physiological signal for TRPM4 activation, we wondered whether U73122 activates TRPM4 currents indirectly through such a cytoplasmic Ca2 + increase. We omitted Ca2 + from the intracellular (pipette) solution and dialysed CHO cells with a high concentration of the fast Ca2 +‐chelator BAPTA (20 mM) through the patch pipette before application of U73122. With BAPTA in the pipette, U73122 activated currents that were indistinguishable from currents in control cells dialysed with solution containing 100 nM free intracellular Ca2 +, and thus permissive for endogenous Ca2 + signals (buffered with 5 mM EGTA; Figure 4A; no statistically significant difference). Ca2 + and PI(4,5)P2 are positive modulators of TRPM4 channel function, and it is well established that both are required to activate the channels under physiological conditions (Launay et al., 2002; Nilius et al., 2006). To examine whether a combination of Ca2 + together with PI(4,5)P2 is necessary for TRPM4 channel function in presence of U73122, we performed additional experiments. Figure 4B shows that in cells dialysed with the Ca2 + chelator BAPTA and neomycin U73122‐activated currents were essentially the same as in control cells (no statistically significant difference). Thus, we conclude that, in fact, TRPM4 channels can be activated by U73122 even in absence of the reported essential cofactors Ca2 + and PI(4,5)P2.

Actions of U73122 involve covalent modification of TRPM4 or an associated subunit

Given that PLC, PI(4,5)P2 and Ca2 + were not involved, we next asked whether any other soluble cytoplasmic factor was necessary for activation of TRPM4 by U73122. Therefore, we applied U73122 to inside‐out patches excised from CHO cells. U73122, but not U73343, induced sizeable currents sharing the biophysical properties of TRPM4 that were sensitive to 9‐phenanthrol (100 μM). These findings demonstrated activation of TRPM4 in isolated membranes depleted of soluble cytosolic components (Figure 5A). We concluded that U73122 acts on the channel directly or through closely associated subunits that remain attached to the channel in excised membrane patches. Because activation of TRPM4 occurred in the absence of ATP (see Methods), protein phosphorylation is also unlikely to be involved.

U73122 is an N‐substituted maleimide that can alkylate amino acid residues (e.g. cysteine) by covalent conjugation. Such a mechanism may underlie its activation of TRPM4, as only the maleimide U73122, but not the structural analogue U73343 lacking the alkylation capacity activates TRPM4 channels (cf. Figure 1C) (Bleasdale et al., 1990; Smith et al., 1990). Stable modification is also supported by the observation that even after removal of U73122 TRPM4 remained active on the time scale of the whole‐cell patch clamp experiments (>20 min). Furthermore, U73122‐induced whole‐cell currents were insensitive to reduction by DTT as expected from covalent modification through alkylation of the channel or associated proteins (Figure 5B, Supporting Information Fig. S3 for control experiments).

To further test this idea, we additionally used NEM, another maleimide compound widely employed to alkylate cysteine residues. Whilst sharing the chemical reactivity with U73122, NEM is smaller in size (Supporting Information Fig. S1A) (Li et al., 2004; Horowitz et al., 2005; Wilsher et al., 2007). Application of NEM (100 or 300 μM) did not induce any whole‐cell currents in CHO cells (Figure 5C and D; Supporting Information Fig. S3 for control experiments). However, pre‐application of NEM (100 μM) completely abolished current induction by U73122 (Figure 5C and D). Because NEM did not inhibit U73122‐induced currents when applied after U73122 (Figure 5E), these findings indicated that the target site of U73122 was occluded by pre‐application of NEM. Thus, a cysteine residue of the pore‐forming channel subunit or a closely associated membrane‐resident interaction partner is most probably essential for the U73122‐mediated activation of TRPM4. However, further work is needed to fully elucidate whether U73122 directly targets TRPM4 or closely associated auxiliary proteins.

Specificity of TRPM channel modulation by U73122

We then tested whether U73122 also modulates the activity of related TRPM channel family members. TRPM5 is a Ca2 +‐activated channel with high sequence similarity to TRPM4 and similar functional properties (Hofmann et al., 2003; Prawitt et al., 2003; Ullrich et al., 2005). As shown in Figure 6A and Supporting Information Fig. S4, dialysis of HEK293T cells overexpressing murine TRPM5 with micromolar Ca2 + induced currents with properties consistent with Ca2 +‐activated TRPM5 (Hofmann et al., 2003; Prawitt et al., 2003). Currents appeared immediately after establishment of the whole‐cell configuration, were dependent on the Ca2 + concentration and were absent in non‐transfected cells (Supporting Information Fig. S4). TRPM5 currents measured after pre‐application of U73122 (5 μM; for 60 s before establishment of whole‐cell configuration) were indistinguishable from untreated controls (Figure 6A), indicating that TRPM5 channels are insensitive to U73122.

The steroid pregnenolone sulphate (PS; 50 μM) induced outwardly rectifying currents and intracellular Ca2 + elevation in HEK293 cells stably expressing murine TRPM3 channels (HEKmTRPM3; Figure 6B and C), as previously reported (Wagner et al., 2008; Frühwald et al., 2012). U73122 did not induce currents or Ca2 + transients in these HEKmTRPM3 cells indicating that the substance does not activate TRPM3 channels (Figure 6B, C). In contrast, pretreatment with U73122 strongly suppressed PS‐induced currents (Figure 6B) and Ca2 + transients (Figure 6C), whereas the structural analogue U73343 had no effect on TRPM3 (Figure 6C). Because this suggested that the mechanism of channel modulation may be similar to the activation of TRPM4, we examined the effect of NEM on TRPM3 channel inhibition by U73122. As shown in Figure 6D, pretreatment of HEKmTRPM3 cells with NEM (100 μM) attenuated the inhibition of TRPM3 channels by U73122. Hence, the inhibition of TRPM3 channels is probably also caused by alkylation.

In summary, U73122 modulates the activity of TRPM channels differentially and with high selectivity for the specific channel isoforms by a mechanism involving covalent modification.

Discussion and conclusions

U73122 activates TRPM4 channels

We showed that U73122 is a potent TRPM4 channel opener that is already effective at nanomolar concentrations. Because the compound activates endogenous TRPM4 channels in various cell types from different species as well as recombinant TRPM4, we concluded that U73122 is a general TRPM4 channel agonist.

Ca2 + constitutes the natural ligand of TRPM4, and under physiological conditions membrane, PI(4,5)P2 is essential for channel activation (Nilius et al., 2006). Hence, the finding that the classical PLC inhibitor U73122 activates TRPM4 suggests the obvious mechanism that this activation is mediated by Ca2 + and PI(4,5)P2, given that levels of both positive modulators can depend on PLC (Nilius et al., 2006). However, utilizing a diversity of established experimental tools (Powis et al., 1992; Halaszovich et al., 2009; Leitner et al., 2011; Wilke et al., 2014; Leitner et al., 2015), we find that activation of TRPM4 by U73122 is independent of PLC, Ca2 + and PI(4,5)P2. Importantly, we show that inhibition of PLC is neither sufficient nor necessary for U73122‐dependent activation of TRPM4 channels and that inhibition of PLC does not cause an increase of PI(4,5)P2 levels. U73122 activated TRPM4 in absence of Ca2 + and PI(4,5)P2 demonstrating that in contrast to physiological (Ca2 +‐dependent) activation these two cofactors are dispensable for channel function in presence of U73122 (cf. Figures 3 and 4). This suggests either that the U73122‐activated channel has higher PI(4,5)P2 affinity than when gated through intracellular Ca2 + or that in presence of U73122 the channel function does not require the reported cofactor PI(4,5)P2 (cf. Nilius et al., 2006). We want to point out that this is the first evidence that TRPM4 channels are functional in the absence of Ca2 + and that, therefore, increases in the concentration of cytosolic Ca2 + are also not essentially required to gate the channels.

But how exactly does U73122 activate TRPM4 channels? Because only U73122, but not U73343, was effective, covalent modification is the most probable candidate mechanism for the modulation of TRPM channels. Importantly, the maleimide U73122 conjugates unspecifically to biological nucleophils in a Michael‐addition reaction (Bleasdale et al., 1990; Smith et al., 1990; Horowitz et al., 2005). Thus, any nucleophilic amino acid residue (e.g. cysteine) that is accessible to the compound is a potential target and alkylation of a combination of accessible cysteines might induce channel opening. Such a mechanism is also supported by the fact that activation of TRPM4 by U73122 is abolished by pre‐application of NEM that most probably occludes the relevant target site(s) of U73122. Whilst this demonstrated that NEM presumably also can alkylate TRPM4 or an auxiliary subunit (see below), it is important to mention that NEM alone did not activate the channel. Probably alkylation with a larger chemical moiety or a compound with other stereochemistry is necessary to induce channel gating, that is, only large hydrophobic U73122, but not NEM, induced conformational changes to open the channels. Because NEM similarly abrogated U73122‐dependent inhibition of TRPM3, such covalent modification through alkylation appears to be a common mechanism to modulate the activity of TRPM channels.

Yet it remains to be elucidated whether U73122 activates TRPM4 directly or through alkylation of a closely associated membrane‐resident auxiliary subunit. U73122 induced TRPM4 currents even in excised membrane patches indicating that soluble cytoplasmic factors are not necessary for the action of U73122 on the channel. We think that, if auxiliary channel subunits are involved, these proteins should be expressed ubiquitously, because U73122 activated TRPM4 in cells from hamster and in various cell types from human origin. In addition, putative and yet unidentified, endogenous subunits would need to be highly expressed to saturate recombinantly overexpressed TRPM4 or TRPM3 channel protein. The necessary factors would be required to interact with TRPM4 and TRPM3, but not necessarily with the TRPM5 isoform, as the activity only of these first two is modulated. Finally, an auxiliary subunit should confer U73122‐dependent activation and inhibition to TRPM4 and TRPM3 channels, respectively, all together making this hypothetical mechanism rather unlikely. Hence, the most economical mechanistic model proposes that U73122 alkylates the pore‐forming α‐subunit to modulate TRPM channel activity. However, we want to emphasize that at present we cannot exclude indirect actions of U73122 on TRPM channels through alkylation of ubiquitously expressed auxiliary subunits. To establish the underlying molecular structures with certainty, obviously, further work employing mass spectrometry or cysteine scanning mutagenesis is required.

Implications for experimental analysis of TRPM channels

Until now, only decavanadate and BTP2 (3,5‐bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazole) (Nilius et al., 2004; Takezawa et al., 2006) are known to positively modulate the activity of TRPM4 channels (Launay et al., 2002; Nilius et al., 2006). Decavanadate increases the sensitivity of the channels to Ca2 + (Nilius et al., 2004), and BTP2 activates TRPM4 only at high cytoplasmic Ca2 + levels (Takezawa et al., 2006). In contrast, U73122 allows for (experimental) activation of TRPM4 independently of Ca2 +, that is, decoupled from the physiological ligand. Thus, U73122 might be used in high‐throughput screens to identify TRPM4 channel inhibitors or gating modifiers. Additionally, U73122 may help to identify functional TRPM4 channels in native tissue and to study the impact of TRPM4 channel activity on cellular physiology. Given subtype specificity within the TRPM channel family, U73122 may be utilized to differentiate between TRPM channel isoforms on cellular level, especially between Ca2 +‐activated TRPM4 and TRPM5 channels. In contrast, limited overall selectivity of U73122 together with other reported serious side effects (see below), its restricted stability in solution and importantly inhibitory actions on PLC obviously limit its applicability in multicellular preparations and presumably prevents the use in vivo.

We provide first evidence for activation of TRPM4 channels through alkylation and covalent modification. Such covalent modification is a well‐established and physiologically relevant mechanism to activate TRPA1 channels to mediate the sensation of pungent compounds and natural irritants (Hinman et al., 2006; Macpherson et al., 2007). Thus, it is tempting to speculate about the existence of physiologically relevant ligands that selectively activate TRPM4 channels through a similar mechanism. However, whilst this is an interesting idea, such potential endogenous ligands await identification.

Implications for experimental use of U73122

Several side effects of U73122 have been published previously that are shared in most reported cases with its structural analogue and negative control U73343. Both substances activate nuclear oestrogen receptors (Cenni and Picard, 1999) and inhibit histamine H1 (Hughes et al., 2000) as well as adenosine A1 receptors (Walker et al., 1998). U73122 and U73343 inhibit Kir3, BK K+ channels (Cho et al., 2001; Klose et al., 2008; Sickmann et al., 2008) and Ca2 + channels (Berven and Barritt, 1995). In contrast, only U73343 (but not U73122) activates TRPM7 possibly through direct interaction with the channels (Hofmann et al., 2014). The actions of U73122 on TRPM channels add to these reported effects bearing considerably higher risk for misleading interpretations of results. This is most likely for activation of TRPM4 by U73122, as these channels are ubiquitously expressed (Mathar et al., 2014a). TRPM4 has been identified in virtually every cell line tested (Launay et al., 2002; Yarishkin et al., 2008; Amarouch et al., 2013), in cell types of the immune system (Launay et al., 2004; Vennekens et al., 2007; Barbet et al., 2008), in the nervous system (Gerzanich et al., 2009; Schattling et al., 2012) and in the heart (Kruse et al., 2009), among many other cell types and organs. We want to emphasize that at concentrations generally used and also required to inhibit PLC, U73122 irreversibly induces currents through TRPM4. This activation may depolarise the membrane potential substantially thereby severely affecting cell physiology. Cellular responses to activation of TRPM4 may include activation of voltage‐gated ion channels, or the reduction (of the driving force) of Ca2 + entry through already active channels, which will strongly impact cellular Ca2 + dynamics (cf. Launay et al., 2004). Importantly, U73343 is not suitable as negative control, because it does not activate TRPM4 and thus, in this case, might even support conclusions that erroneously attribute effects to the PLC pathway, whilst in reality, TRPM4 channel activation is the underlying mechanism. We want to point out that these side effects essentially prevent the in vivo use of U73122 and that control experiments (preferentially on single cell level using electrophysiological techniques) should be designed carefully to avoid misinterpretation of results and incorrect conclusions derived from application of U73122.

Taken together, the most frequently employed PLC inhibitor U73122 significantly modulates the activity of TRPM channels, that is, at concentrations required to inhibit PLC U73122 activates TRPM4 and inhibits TRPM3. Given widespread expression of these channels, we strongly advice to consider U73122‐dependent modulation of TRPM channels when U73122 is used to modulate the PLC signalling cascade. Our findings probably even necessitate revision of previously established mechanistic conclusions based on application of the substance.

Author contributions

M.G.L., J.O. and D.O. conceptualized and designed experiments. M.G.L., N.M., M.B., M.D., S.D., B.U.W., M.K., M.L., J.O. and D.O. collected, analysed and interpreted data. M.G.L, J.O. and D.O. wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript, and all authors that qualify for authorship are designated. The experiments were conducted in the Institute of Physiology and Pathophysiology at the Philipps‐University Marburg (Germany).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Declaration of transparency and scientific rigour

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organisations engaged with supporting research.

Supporting information

Figure S1 U73122 activates endogenous TRPM4 currents in non‐transfected CHO cells. (A) Chemical structures of the PLC inhibitor U73122, the inactive analogue U73343 and N‐Ethylmaleimide (NEM). U73122 (left) is an N‐substituted maleimide, whereas in U73343 (right) the maleimide is substituted with a nonreactive succinimide (U73343 lacks one double bond). NEM (middle) is an N‐substituted maleimide just as U73122, but smaller in size. Because U73122 gradually looses activity over time, solutions should be prepared directly before use and discarded after 30 min (U73122, 1‐[6‐[[(17β)‐3‐Methoxyestra‐1,3,5(10)‐trien‐17‐yl]amino]hexyl]‐1H‐pyrrole‐2,5‐dione; U73343, 1‐[6‐[[(17β)‐3‐Methoxyestra‐1,3,5(10)‐trien‐17‐yl]amino]hexyl]‐2,5‐pyrrolidinedione; NEM, 1‐Ethylpyrrole‐2,5‐dione). (B) Application of 20 μM U73122 subsequent to 10 μM caused only negligible current increase indicating that 10 μM U73122 may constitute a saturating concentration to activate TRPM4 (left: representative recording, right: summary of recordings, normalized to the current at 10 μM U73122; n = 6). Please note that due to low stability of U73122 in solution, the irreversibility of current induction and the incompatibility of higher U73122 concentrations with patch clamp the maximal and half maximal current by U73122 cannot be determined with certainty. Thus, the given values may represent only approximations to the actual concentration–response relationship. (C) TRPM4‐specific antagonist 9‐phenanthrol dose dependently inhibited U73122‐dependent currents with an IC50 of 24.9 ± 3.23 μM (n = 8). Dose response relation was derived from recordings presented in Figure 1I of the main text. (D) Dialysis of non‐transfected CHO cells with 500 μM free Ca2+ through a patch pipette induced 9‐phenanthrol (100 μM) sensitive currents in non‐transfected CHO cells (n = 5; pipette solution contained in mM: 135 KCl, 3.5 MgCl2, 5.2 CaCl2 (500 μM free), 5 EGTA and 5 HEPES; pH 7.3 with KOH, 290 mOsm·kg−1). These findings indicate that endogenous TRPM4 channels are functional in CHO cells and exhibit outward rectification when activated by intracellular Ca2+. Note that Ca2+ activated currents in every cell tested, but the time courses of current induction significantly varied between single cells. Hence, the panel shows peak current amplitudes in a representative recording (left) and a summary of recordings from five independent cells (right).

Figure S2 KCNQ2 (Kv7.2) currents as sensitive reporter of PI(4,5)P2 levels. K+ currents were recorded in CHO cells transiently overexpressing voltage‐gated KCNQ2 channels (voltage protocols and scale bars as indicated; dashed line indicates 0 current). (A) In cells overexpressing PI5K (type‐1 β), KCNQ2‐mediated currents were significantly larger (n = 7) than in controls without PI5K (n = 6). These data demonstrate that overexpression of PI5K robustly increased cellular PI(4,5)P2 levels (left, representative recordings; right, summary of recordings). (B) Dialysis of CHO cells with neomycin (1 mM) through the patch pipette rapidly inhibited KCNQ2‐mediated currents through a reduction of available PI(4,5)P2 (control: n = 6; neomycin: n = 7). The left panel depicts representative recordings with/without neomycin at the start (black) and the end (grey) of the experiment. Deactivation of KCNQ2 channels was complete after approx. 3 min. The right panel shows the summarized time course of the experiments. The arrowhead represents establishment of the whole‐cell configuration. (C) Activation of voltage‐dependent PI(4,5)P2 5‐phosphatase Ci‐VSP (30 s, +80 mV) reversibly deactivated KCNQ2 channels in control cells (n = 5) and in cells pretreated with 5 μM U73122 (n = 5). In cells dialysed with AMP‐PCP (2.3 mM) for 4 min before activation of Ci‐VSP, KCNQ2 currents did not recover from Ci‐VSP‐dependent inhibition demonstrating that AMP‐PCP inhibits PI5K required for the resynthesis of PI(4,5)P2 (n = 6). (D) Activation of co‐expressed Gq protein‐coupled muscarinic receptors type 1 (M1R) with oxotremorine‐M (oxo‐M, 10 μM; grey insert) robustly inhibited KCNQ2 (Kv7.2) channels (n = 5). Channel deactivation was largely attenuated by pretreatment of CHO cells with the PLC inhibitor edelfosine (10 μM; 30 min) (left, representative recording; right, time course of KCNQ2 inhibition) demonstrating efficient inhibition of PLC under our experimental setting (n = 6).

Figure S3 NEM, DTT and H2O2 are active under our experimental conditions. (A) and (B) As previously reported, NEM (100 μM) irreversibly activated voltage‐gated KCNQ2 channels. Current activation could not be reversed by application of DTT (5 mM; n = 8). Treatment of CHO cells with H2O2 (5 mM) potentiated currents through recombinant KCNQ2 channels, and current potentiation was reversed by application of DTT (5 mM; n = 6). These recordings demonstrated that NEM and DTT were active under our experimental conditions (voltage protocols and scale bars as indicated).

Figure S4 Ca2+‐sensitive TRPM5 currents in transfected HEK293T cells. In HEK293T cells overexpressing murine TRPM5 channels, intracellular Ca2+ induced outwardly rectifying currents in a concentration‐dependent manner. These currents were absent in non‐transfected HEK293T cells. The Figure depicts representative recordings (left) and a summary of recordings over time (right). The arrowhead in the right panel indicates rupture of the membrane patch and establishment of the whole‐cell configuration (1 μM Ca2+: n = 6; 100 nM Ca2+: n = 5; 1 μM Ca2+/not transfected: n = 5).

Supporting information

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the kind gift of plasmids for Ci‐VSP from Dr Y. Okamura, hTRPM4/mTRPM5 from Dr T. Gudermann and KCNQ2 from Dr T. Jentsch. We thank Julia Hartmann, Raissa Enzeroth, Natalia Fritzler and Olga Ebers for superb technical assistance. We thank Dr R. Vennekens for helpful comments. This work was supported by a Research Grant of the University Medical Center Giessen und Marburg (UKGM) to M.G.L. (UKGM 17/2013; UKGM 13/2016) and by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to M.G.L. (LE 3600/1‐1, SPP1608/2) and through SFB 593 to J.O. (TPA16) and D.O. (TPA12).

Leitner, M. G. , Michel, N. , Behrendt, M. , Dierich, M. , Dembla, S. , Wilke, B. U. , Konrad, M. , Lindner, M. , Oberwinkler, J. , and Oliver, D. (2016) Direct modulation of TRPM4 and TRPM3 channels by the phospholipase C inhibitor U73122. British Journal of Pharmacology, 173: 2555–2569. doi: 10.1111/bph.13538.

References

- Alexander SPH, Catterall WA, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Voltage‐gated ion channels. Br J Pharmacol 172: 5904–5941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SP, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 172: 6024–6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amarouch MY, Syam N, Abriel H (2013). Biochemical, single‐channel, whole‐cell patch clamp, and pharmacological analyses of endogenous TRPM4 channels in HEK293 cells. Neurosci Lett 541: 105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badheka D, Borbiro I, Rohacs T (2015). Transient receptor potential melastatin 3 is a phosphoinositide‐dependent ion channel. J Gen Physiol 146: 65–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbet G, Demion M, Moura IC, Serafini N, Leger T, Vrtovsnik F et al. (2008). The calcium‐activated nonselective cation channel TRPM4 is essential for the migration but not the maturation of dendritic cells. Nat Immunol 9: 1148–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berven LA, Barritt GJ (1995). Evidence obtained using single hepatocytes for inhibition by the phospholipase C inhibitor U73122 of store‐operated Ca2+ inflow. Biochem Pharmacol 49: 1373–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleasdale JE, Thakur NR, Gremban RS, Bundy GL, Fitzpatrick FA, Smith RJ et al. (1990). Selective inhibition of receptor‐coupled phospholipase C‐dependent processes in human platelets and polymorphonuclear neutrophils. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 255: 756–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenni B, Picard D (1999). Two compounds commonly used for phospholipase C inhibition activate the nuclear estrogen receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 261: 340–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Youm JB, Ryu SY, Earm YE, Ho WK (2001). Inhibition of acetylcholine‐activated K(+) currents by U73122 is mediated by the inhibition of PIP(2)‐channel interaction. Br J Pharmacol 134: 1066–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MJ, Bond RA, Spina D, Ahluwalia A, Alexander SP, Giembycz MA et al. (2015). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting: new guidance for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3461–3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demion M, Bois P, Launay P, Guinamard R (2007). TRPM4, a Ca2 + ‐activated nonselective cation channel in mouse sino‐atrial node cells. Cardiovasc Res 73: 531–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drews A, Mohr F, Rizun O, Wagner TF, Dembla S, Rudolph S et al. (2014). Structural requirements of steroidal agonists of transient receptor potential melastatin 3 (TRPM3) cation channels. Br J Pharmacol 171: 1019–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frühwald J, Camacho Londono J, Dembla S, Mannebach S, Lis A, Drews A et al. (2012). Alternative splicing of a protein domain indispensable for function of transient receptor potential melastatin 3 (TRPM3) ion channels. J Biol Chem 287: 36663–36672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerzanich V, Woo SK, Vennekens R, Tsymbalyuk O, Ivanova S, Ivanov A et al. (2009). De novo expression of Trpm4 initiates secondary hemorrhage in spinal cord injury. Nat Med 15: 185–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grand T, Demion M, Norez C, Mettey Y, Launay P, Becq F et al. (2008). 9‐phenanthrol inhibits human TRPM4 but not TRPM5 cationic channels. Br J Pharmacol 153: 1697–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaszovich CR, Schreiber DN, Oliver D (2009). Ci‐VSP is a depolarization‐activated phosphatidylinositol‐4,5‐bisphosphate and phosphatidylinositol‐3,4,5‐trisphosphate 5′‐phosphatase. J Biol Chem 284: 2106–2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heissmeyer V, Macian F, Im SH, Varma R, Feske S, Venuprasad K et al. (2004). Calcineurin imposes T cell unresponsiveness through targeted proteolysis of signaling proteins. Nat Immunol 5: 255–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinman A, Chuang HH, Bautista DM, Julius D (2006). TRP channel activation by reversible covalent modification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 19564–19568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann T, Chubanov V, Gudermann T, Montell C (2003). TRPM5 is a voltage‐modulated and Ca(2+)‐activated monovalent selective cation channel. Curr. Biol. 13: 1153–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann T, Schafer S, Linseisen M, Sytik L, Gudermann T, Chubanov V (2014). Activation of TRPM7 channels by small molecules under physiological conditions. Pflug. Arch.: Eur. J. Phy 466: 2177–2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz LF, Hirdes W, Suh BC, Hilgemann DW, Mackie K, Hille B (2005). Phospholipase C in living cells: activation, inhibition, Ca2+ requirement, and regulation of M current. J Gen Physiol 126: 243–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes SA, Gibson WJ, Young JM (2000). The interaction of U‐73122 with the histamine H1 receptor: implications for the use of U‐73122 in defining H1 receptor‐coupled signalling pathways. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 362: 555–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RR, Bourdon DM, Costales CL, Wagner CD, White WL, Williams JD et al. (2011). Direct activation of human phospholipase C by its well known inhibitor u73122. J Biol Chem 286: 12407–12416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose A, Huth T, Alzheimer C (2008). 1‐[6‐[[(17beta)‐3‐methoxyestra‐1,3,5(10)‐trien‐17‐yl]amino]hexyl]‐1H‐pyrrole‐2,5‐ dione (U73122) selectively inhibits Kir3 and BK channels in a phospholipase C‐independent fashion. Mol Pharmacol 74: 1203–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobrinsky E, Mirshahi T, Zhang H, Jin T, Logothetis DE (2000). Receptor‐mediated hydrolysis of plasma membrane messenger PIP2 leads to K + −current desensitization. Nat Cell Biol 2: 507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse M, Schulze‐Bahr E, Corfield V, Beckmann A, Stallmeyer B, Kurtbay G et al. (2009). Impaired endocytosis of the ion channel TRPM4 is associated with human progressive familial heart block type I. J Clin Invest 119: 2737–2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK (1970). Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227: 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launay P, Cheng H, Srivatsan S, Penner R, Fleig A, Kinet JP (2004). TRPM4 regulates calcium oscillations after T cell activation. Science 306: 1374–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launay P, Fleig A, Perraud AL, Scharenberg AM, Penner R, Kinet JP (2002). TRPM4 is a Ca2 + −activated nonselective cation channel mediating cell membrane depolarization. Cell 109: 397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitner MG, Feuer A, Ebers O, Schreiber DN, Halaszovich CR, Oliver D (2012). Restoration of ion channel function in deafness‐causing KCNQ4 mutants by synthetic channel openers. Br J Pharmacol 165: 2244–2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitner MG, Halaszovich CR, Ivanova O, Oliver D (2015). Phosphoinositide dynamics in the postsynaptic membrane compartment: mechanisms and experimental approach. Eur J Cell Biol 94: 401–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitner MG, Halaszovich CR, Oliver D (2011). Aminoglycosides inhibit KCNQ4 channels in cochlear outer hair cells via depletion of phosphatidylinositol(4,5)bisphosphate. Mol Pharmacol 79: 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Gamper N, Hilgemann DW, Shapiro MS (2005). Regulation of Kv7 (KCNQ) K+ channel open probability by phosphatidylinositol 4,5‐bisphosphate. J Neurosci 25: 9825–9835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Gamper N, Shapiro MS (2004). Single‐channel analysis of KCNQ K+ channels reveals the mechanism of augmentation by a cysteine‐modifying reagent. J Neurosci 24: 5079–5090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner M, Leitner MG, Halaszovich CR, Hammond GR, Oliver D (2011). Probing the regulation of TASK potassium channels by PI4,5P(2) with switchable phosphoinositide phosphatases. J Physiol 589: 3149–3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan D, McCarron JG (2010). The phospholipase C inhibitor U‐73122 inhibits Ca(2+) release from the intracellular sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) store by inhibiting Ca(2+) pumps in smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1295–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson LJ, Dubin AE, Evans MJ, Marr F, Schultz PG, Cravatt BF et al. (2007). Noxious compounds activate TRPA1 ion channels through covalent modification of cysteines. Nature 445: 541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrez‐Lepretre N, Morel JL, Mironneau J (1996). Effects of phospholipase C inhibitors on Ca2+ channel stimulation and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores evoked by alpha 1A‐ and alpha 2A‐adrenoceptors in rat portal vein myocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 218: 30–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathar I, Jacobs G, Kecskes M, Menigoz A, Philippaert K, Vennekens R (2014a). Trpm4. Handb Exp Pharmacol 222: 461–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathar I, Kecskes M, Van der Mieren G, Jacobs G, Camacho Londono JE, Uhl S et al. (2014b). Increased beta‐adrenergic inotropy in ventricular myocardium from Trpm4‐/‐ mice. Circ Res 114: 283–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogami H, Lloyd Mills C, Gallacher DV (1997). Phospholipase C inhibitor, U73122, releases intracellular Ca2+, potentiates Ins(1,4,5)P3‐mediated Ca2+ release and directly activates ion channels in mouse pancreatic acinar cells. Biochem J 324: 645–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y, Iwasaki H, Sasaki M, Inaba K, Okamura Y (2005). Phosphoinositide phosphatase activity coupled to an intrinsic voltage sensor. Nature 435: 1239–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto Y, Nagao T, Urushidani T (1997). The putative phospholipase C inhibitor U73122 and its negative control, U73343, elicit unexpected effects on the rabbit parietal cell. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 282: 1379–1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Mahieu F, Prenen J, Janssens A, Owsianik G, Vennekens R et al. (2006). The Ca2 + ‐activated cation channel TRPM4 is regulated by phosphatidylinositol 4,5‐biphosphate. EMBO J 25: 467–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Prenen J, Janssens A, Owsianik G, Wang C, Zhu MX et al. (2005). The selectivity filter of the cation channel TRPM4. J Biol Chem 280: 22899–22906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Prenen J, Janssens A, Voets T, Droogmans G (2004). Decavanadate modulates gating of TRPM4 cation channels. J Physiol 560: 753–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberwinkler J, Philipp SE (2014). Trpm3. Handb Exp Pharmacol 222: 427–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powis G, Seewald MJ, Gratas C, Melder D, Riebow J, Modest EJ (1992). Selective inhibition of phosphatidylinositol phospholipase C by cytotoxic ether lipid analogues. Cancer Res 52: 2835–2840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prawitt D, Monteilh‐Zoller MK, Brixel L, Spangenberg C, Zabel B, Fleig A et al. (2003). TRPM5 is a transient Ca2 + ‐activated cation channel responding to rapid changes in [Ca2+]i. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 15166–15171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter JM, Schaefer M, Hill K (2014). Riluzole activates TRPC5 channels independently of PLC activity. Br J Pharmacol 171: 158–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rjasanow A, Leitner MG, Thallmair V, Halaszovich CR, Oliver D (2015). Ion channel regulation by phosphoinositides analyzed with VSPs‐PI(4,5)P2 affinity, phosphoinositide selectivity, and PI(4,5)P2 pool accessibility. Front Pharmacol 6: 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schattling B, Steinbach K, Thies E, Kruse M, Menigoz A, Ufer F et al. (2012). TRPM4 cation channel mediates axonal and neuronal degeneration in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Nat Med 18: 1805–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiekel J, Lindner M, Hetzel A, Wemhoner K, Renigunta V, Schlichthorl G et al. (2013). The inhibition of the potassium channel TASK‐1 in rat cardiac muscle by endothelin‐1 is mediated by phospholipase C. Cardiovasc Res 97: 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sickmann T, Klose A, Huth T, Alzheimer C (2008). Unexpected suppression of neuronal G protein‐activated, inwardly rectifying K+ current by common phospholipase C inhibitor. Neurosci Lett 436: 102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard C, Hof T, Keddache Z, Launay P, Guinamard R (2013). The TRPM4 non‐selective cation channel contributes to the mammalian atrial action potential. J Mol Cell Cardiol 59: 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RJ, Sam LM, Justen JM, Bundy GL, Bala GA, Bleasdale JE (1990). Receptor‐coupled signal transduction in human polymorphonuclear neutrophils: effects of a novel inhibitor of phospholipase C‐dependent processes on cell responsiveness. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 253: 688–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SP et al. (2016). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucl. Acids Res. 44: D1054–D1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh BC, Inoue T, Meyer T, Hille B (2006). Rapid chemically induced changes of PtdIns(4,5)P2 gate KCNQ ion channels. Science 314: 1454–1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takezawa R, Cheng H, Beck A, Ishikawa J, Launay P, Kubota H et al. (2006). A pyrazole derivative potently inhibits lymphocyte Ca2+ influx and cytokine production by facilitating transient receptor potential melastatin 4 channel activity. Mol Pharmacol 69: 1413–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]