Abstract

Background and Purpose

IL‐33 is a novel cytokine that is believed to be involved in inflammation and carcinogenesis. However, its source, its production and its secretion process remain unclear. Recently, we have reported that IL‐33 is up‐regulated in dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) colitis in mice.

Experimental Approach

Production of IL‐33 from intestinal tissue was studied in a murine cancer model induced by azoxymethane (AOM) and DSS in vivo and in cultures of IEC‐6 epithelial cells. Cytokine levels were measured by real time PCR, immunohistochemistry and elisa.

Key Results

Mice with AOM/DSS‐induced colitis expressed all the characteristic symptoms of colon cancer pathology. Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated epithelial cell‐derived IL‐33 in colon tissues from mice with AOM/DSS colitis. Real time PCR and quantitative PCR analysis revealed that AOM/DSS colitis tissues expressed up‐regulated IL‐1β, IL‐33, TGF‐β, and EGF mRNA. Gefitinib, an EGFR inhibitor, inhibited IL‐33 mRNA expression in AOM/DSS colitis mice. The pathophysiological role of IL‐33 in the rat intestinal epithelial cell line (IEC‐6 cells) was then investigated. We found that EGF, but not TGF‐β1 or PDGF, greatly enhanced mRNA expression of IL‐33 and its receptor ST2. In accordance with the gene expression and immunohistochemical analysis of IL‐33 levels, elisa‐based analysis of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts showed increased IL‐33 protein levels in IEC‐6 cells after treatment with EGF.

Conclusions and Implications

Our results suggest that EGF is a key growth factor that increased IL‐33 production and ST2 receptor expression during intestinal inflammation and carcinogenesis. The EGF/IL‐33/ST2 axis represents a novel therapeutic target in colon cancer.

Abbreviations

- AOM/DSS

azoxymethane‐dextran sulfate sodium salt

- IEC

intestinal epithelial cell

- PDGFRα

PDGF α receptor

- αSMA

α‐smooth muscle actin

- UC

ulcerative colitis

Tables of Links

| TARGETS |

|---|

| Catalytic receptors |

| EGFR |

| ST2 (IL‐1 receptor‐like 1) |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Southan et al., 2016) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 (Alexander et al., 2015).

Introduction

IL‐33 is a novel cytokine of the IL‐1 superfamily (Nishida et al., 2009) that is expressed mainly in stromal cells, such as epithelial and endothelial cells (Miller, 2011). IL‐33 is preferentially expressed in the specialized endothelium of high endothelial venules (HEVs) and has been termed the nuclear factor HEVs (Baekkevold et al., 2003; Moussion et al., 2008; Lopetuso et al., 2012). Although typical cytokines exert their biological effects through the activation of specific cell surface receptors, IL‐33 elicits its effects both through activation of the membrane associated ST2 receptor also known as IL‐1 receptor‐like 1 protein) (Yagami et al., 2010) and as an intracellular nuclear factor with transcriptional regulatory properties (Kakkar and Lee, 2008; Haraldsen et al., 2009; Nabe, 2014). Both endogenous and environmental factors trigger the IL‐33 system during infection, inflammation and tissue damage (Lloyd, 2010). Although IL‐33 was previously described as a nuclear factor, it is now known to be expressed in the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Beltran et al., 2009). IL‐33 is thought to function as an alarmin that is released following cell necrosis to alert the immune system to tissue damage or stress (Miller, 2011; Pichery et al., 2012).

Recently, more emphasis has been placed on the pro‐inflammatory roles of the IL‐33/ST2 signalling pathway, particularly in gastrointestinal pathophysiology related to colitis and carcinogenesis. For example, patients with active ulcerative colitis (UC) express significantly elevated levels of IL‐33 mRNA, and sub‐epithelial myofibroblasts act as a major source of IL‐33 (Kobori et al., 2010) and play a critical role in mucosal repair process in the mucosa of UC patients (Andoh et al., 2002). IL‐33/ST2 is also associated with many inflammatory diseases such as asthma (Lloyd, 2010; Morita et al., 2012; Mizutani et al., 2014; Nabe et al., 2015), rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis or osteoarthritis (Talabot‐Ayer et al., 2011), pulmonary fibrosis (Tajima et al., 2007), dermatitis (Schmitz et al., 2005) and allergic contact dermatitis (Taniguchi et al., 2014). Knockdown of ST2 in mice resulted in decreased skin inflammation (Hueber et al., 2011), suggesting a novel treatment strategy for inflammatory skin diseases. Although more emphasis is currently being placed on the pro‐inflammatory activity of the IL‐33 signalling pathway, the protective roles of IL‐33 in atherosclerosis, obesity, type2 diabetes and cardiac remodelling (Miller, 2011) cannot be ignored.

The role of growth factors in cytokine production and related inflammatory responses has been extensively studied; however, to our knowledge, there are no reports regarding the role of growth factor(s) in IL‐33 production. Of the many known growth factors, it is generally known that TGF‐β and EGF are potent signalling substances having a strong influence on the regulation of intestinal epithelial cell (IEC) differentiation (Frey et al., 2004; Abud et al., 2005) and colonic cancer progression (Salomon et al., 1995). Therefore, in the present study, we attempted to analyse the role of these agents in regulating the IL‐33/ST2 system in IECs. We also assessed intestinal epithelial cell‐derived IL‐33 expression in a mouse model of colonic cancer.

Methods

Animals and treatments

All aminal care and experimental procedures were in accordance with the institutional guidelines of The University of Tokyo and were approved by the local Animal Ethics Committee (approval code: P07–138). All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath and Lilley, 2015). Eight‐week‐old male C57BL/6J mice (Charles River, Yokohama, Japan) with an average weight of 24 g were used in this study. They were maintained under a constant 12 h light–dark cycle at an environmental temperature of 20–25°C. All animals were provided with tap water and basal diet ad libitum. After proper acclimatization, mice were randomly assigned to control and treatment groups. A total of 105 animals were used in the experiments described here.

Induction of colon tumours in mice

Experimental colon tumours were induced in mice by azoxymethane (AOM) (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and dextran sulfate sodium salt (DSS) (MP Biomedicals, LLC, Illkirch, France) treatment. Mice were acclimatized for 1 week in our laboratory conditions and then randomly divided into two groups. One group of mice were kept as control (n = 10) provided with tap water and a basal diet ad libitum. The other group of mice (n = 15) were injected with a single dose of AOM (10 mg·kg−1, i.p.). One week after the AOM treatment, the mice were treated with 1% DSS (w·v−1) in their drinking water ad libitum for 7 days, followed by tap water for 7 days. This is one DSS‐water cycle. The mice were subjected to six DSS‐water cycles. In the group receiving treatment with azoxymethane‐dextran sulfate sodium salt (AOM/DSS), a total of seven mice died at different stages of experimental periods: two mice at cycle1, three mice at cycle 2 and two mice at cycle 4 respectively. After the sixth DSS‐water cycle, the mice were killed, gross pathology was assessed and samples were collected for histopathology, immunohistochemistry and quantitative real time PCR analyses.

Gefitinib treatment of mice with AOM/DSS‐induced colitis

Two different experimental groups of mice with acute or chronic AOM/DSS‐induced colitis,were used in these experiments. For the acute model, mice were randomly divided into three groups; the control group (n = 10) was provided with tap water and a basal diet ad libitum without giving any treatment. The other two groups were treated with either 100 μL·kg−1 p.o. of the vehicle DMSO (n = 15) or 50 mg·kg−1, p.o. gefitinib (n = 15) (LC Laboratories®, 165 New Boston Street, Woburn, MA 01801, USA).Both vehicle and gefitinib treatments were commenced 2 days before i.p. injection of a single dose of 10 mg·kg−1AOM and were continued until the end of the experiment. Seven days after AOM injection, the mice were treated with 1% DSS (w·v−1) in their drinking water ad libitum for another 7 days. It should be noted that seven mice from the DMSO group and six mice from the gefitinib 50 group died at different stages over the experimental period. The control and treated mice were killed and the mid‐colon was collected for quantitative real time PCR analyses.

For the chronic model, mice were divided into three groups. The control group (n = 10) was provided with tap water and a basal diet ad libitum. The other two groups (n = 15, each) were each injected i.p. with a single dose of 10 mg·kg−1AOM. One week after the AOM treatment, the mice were subjected to three DSS‐water cycles. On day 1 of DSS cycle 3, one group of mice was treated with the vehicle DMSO (100 μL·kg−1p.o.), and the other group of mice was treated with gefitinib (50 mg·kg−1p.o.) until the end of the third DSS‐water cycle. Over the experimental period, six mice from the DMSO and six mice from the gefitinib50 group died at different stages. After the third DSS‐water cycle, the mice were killed, gross pathology was assessed and samples were collected for quantitative real time PCR analyses.

Histopathological analysis

At the end of experiments, the mice were killed, and the colons were separated from the proximal rectum adjacent to the pelvisternum. The colon length was measured between the ileocecal junction and the proximal rectum, and the number of tumours was counted in each colon. For histopathological analysis, representative colon specimens from polyp and non‐polyp areas were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned (4 μm thickness), stained with haematoxylin and eosin (HE) and examined under light microscopy. Examinations were performed at 100× or 200× magnification and representative images of polyp and non‐polyp areas were acquired using an Olympus AX80 microscope.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Representative specimens from the mid‐colon in polyp and non‐polyp areas were permeabilized with Triton X‐100 (0.2%), blocked with 10% normal goat serum and incubated with the following primary antibodies: mouse anti‐E‐cadherin (1:200 dilution; Takara Bio, Japan), goat anti‐IL‐33 (1:100 dilution; R&D System), goat anti‐PDGFRα (1:200 dilution;R&D System), rat anti‐mouse CD45 (1:300 dilution; eBioscience) and Cy3‐conjugated anti‐α‐smooth muscle actin (1:500 dilution; Sigma). After washing with PBS, the specimens were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 555 coupled donkey anti‐IgG (1:1000 dilution; Molecular probes)for 2 h and counter‐stained with DAPI (Molecular Probes). Images were obtained using a Leica TSC‐SP2 confocal microscope and composed using Leica images software.

Cell culture

The IEC‐6 rat small intestinal cell line was obtained from the RIKEN Cell Bank (RCB0993, Japan). The cells were cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS. The condition of the cells was observed using phase contrast microscopy, and healthy cells were sub‐culturedfor subsequent experimentation. In all cases, the experiments were performed in at least triplicate. All experiments were performed in a blinded manner.

Immunohistochemistry for IEC‐6 cells

IEC‐6 cells were cultured on 25 mm glass cover slips until confluence, then serum‐starved overnight and treated with EGF (20 ng·mL−1) or maintained untreated as a control for 24 h. The cells were washed three times with HBSS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After fixation, the cells washed three times with PBS, permeabilized with 0.2% Tween 20(Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) and incubated with blocking buffer (PBS containing 10% normal goat serum) for 1 h. Cells were then washed and incubated with goat polyclonal anti‐IL‐33(1:250 dilution; R&D System) or rabbit polyclonal anti‐ST2 (1:250 dilution; Abcam) antibody overnight at 4°C. The specimens were washed and incubated with Alex Fluor594 donkey anti‐goat IgG or Alex Fluor 488 goat anti‐rabbit IgG (1:1000 dilution; Invitrogen, Molecular Probes) for 2 h at room temperature in a dark chamber.Images were obtained using an Eclipse E800 fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Elisa

IEC‐6 cells were cultured in 60 mm dishes until confluence and then serum‐starved overnight and treated with EGF (20 ng·mL−1), or maintained untreated as a control for 24 h. After 24 h, the medium was collected and the cells washed and subsequently stored at −80°C until experiments were performed. Cytoplasmic and nuclear protein was extracted (Kim et al., 1995). Briefly, the harvested cells were washed twice with HBSS, added to 100 μL of an extraction solution (10 mmol·L−1HEPES, pH 7.9, 10 mmol·L−1KCI, 0.1 mmol·L−1EGTA, 0.1 mol·L−1EDTA, 1 mmol·L−1DTT, 1 mmol·L−1phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and incubated on ice for 20 min. Plasma membranes were ruptured by adding 10 μLof 10% Nonidet P‐40 and mixing vigorously for a few seconds. The cells were further ruptured by sonication on ice. The cytoplasmic protein fraction was obtained by centrifugation at 1500 × g for 3 min. Pellets containing nuclei werere‐suspended in 100 μL of high salt extract solution (20 mmol·L−1HEPES, pH 7.9, 0.4 mmol·L−1NaCl, 0.1 mmol·L−1 EGTA, 0.1 mmol·L−1EDTA, 1 mmol·L−1DTT, 1 mmol·L−1phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and lysed by sonication and vigorous rocking for 30 min on ice. The supernatant was then collected after centrifugation at 13000 × g for 30 min and stored at −80°C until experiments were performed. Protein concentrations of the cytosolic and nuclear extracts were quantified with the Bradford method using Bio‐Rad protein assay solution (Bio‐Rad Laboratories, California, USA) and BSA as the standard. The amount of IL‐33 in conditioned medium, cytosolic and nuclear extracts was measured using an elisa (R&D System, Minneapolis, MN 55413, USA).

Quantitative real time PCR analysis of cells and tissue samples

Total RNA was extracted by using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Tokyo, Japan). First‐strand cDNA was synthesized using a random nine‐mer primer and ReverTra Ace at 30°C for 10 min, 42°C for 1 h, 99°C for 5 min and 4°C for 5 min. PCR amplification was performed using ExTaq DNA polymerase. Real time PCR was performed in an AriaMx Real‐Time PCR System (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA 95051, USA) using SYBR‐green fluorescence (ThunderbirdTm SYBR®, Toyobo, Japan) with the ROX reference dye. Primers used for real time PCR analysis are provided in Table 1. Amplification conditions were 95°C for 60 s as a hot start followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 s; 60°C for 60 s and high resolution dissociation (melting) curves of 95°C for 30 s and 60–95°C for 30 s to confirm primer specificity. The purity of the amplified products was confirmed by dissociation curves and gel electrophoresis. Samples were analysed by the ΔCq method using 18S as the reference gene.

Table 1.

Sequences of the primers used for quantitative real time PCR analysis

| Primer set | Orientation | Sequence (5' to 3') | PCR product |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse‐IL‐1β | Forward Reverse | GACGGACCCCAAAAGATGAA ACAGCTTCTCCACAGCCACA | 145 bp |

| Mouse‐IL‐10 (NM_010548.2) | Forward Reverse | GACAACATACTGCTAACCGACTCC CTGGGGCATCACTTCTACCA | 108 bp |

| Mouse‐TNF‐α | Forward Reverse | CAAACCACCAAGTGGAGGAG GTAGACAAGGTACAACCCATCG | 125 bp |

| Mouse‐IL‐33 | Forward Reverse | TGAGACTCCGTTCTGGCCTC CTCTTCATGCTTGGTACCCGAT | 101 bp |

| Mouse‐TGF‐β1 | Forward Reverse | TACGTCAGACATTCGGGAAGCA AGGTAACGCCAGGAATTGTTGC | 138 bp |

| Mouse EGFR NM_207655.2 | Forward Reverse | TCTTCAAGGATGTGAAGTGTG GTGTACGCTTTCGAACAATGT | 146 bp |

| Mouse‐EGF | Forward Reverse | ATAGTTATCCAGGATGCCCAT CGATCCCCAGAATAGCCAAT | 121 bp |

| Mouse‐18S | Forward Reverse | AAACGGCTACCACATCCAAG CCTCCAATGGATCCTCGTTA | 155 bp |

| Rat‐IL1β NM_031512.2 | Forward Reverse | CACCTCTCAAGCAGAGCACAG GGGTTCCATGGTGAAGTCAAC | 79 bp |

| Rat‐IL‐6 NM_012589.2 | Forward Reverse | AAAGAGTTGTGCAATGGCAATTCT CAGTGCATCATCGCTGTTCATACA | 51 bp |

| Rat‐IL‐10 | Forward Reverse | GTTGCCAAGCCTTGTCAGAAA TTTCTGGGCCATGGTTCTCT | 78 bp |

| Rat‐TNF‐α | Forward Reverse | ACTGAACTTCGGGGTGATTG GCTTGGTGGTTTGCTACGAC | 153 bp |

| Rat‐IL‐33 | Forward Reverse | GTGCAGGAAAGGAAGACTCG TGGCCTCACCATAAGAAAGG | 347 bp |

| Rat‐ST2 | Forward Reverse | ATGATTGGCAAATGGAGAAT TTCTAGACCCCAGGATGTTT | 102 bp |

| Rat‐αSMA (NM_031004) | Forward Reverse | GGGAGTGATGGTTGGAATGG CCGTTAGCAAGGTCGGATG | 197 bp |

Data and statistical analysis

The data and statistical analysis in this study comply with the recommendations on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2015). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Samples were not randomized, and data were collected in a blinded manner. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using graphpad prism 3 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Student's unpaired t‐test was used to compare from two groups, whereas one way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test used to compare among more than two groups, when F achieved P < 0.05and there was no significant variance inhomogeneity. *P < 0.05 was established as the level of statistical significance.

Results

AOM/DSS‐induced colon cancer in mice is associated with up‐regulated mRNA for IL‐33 and growth factors

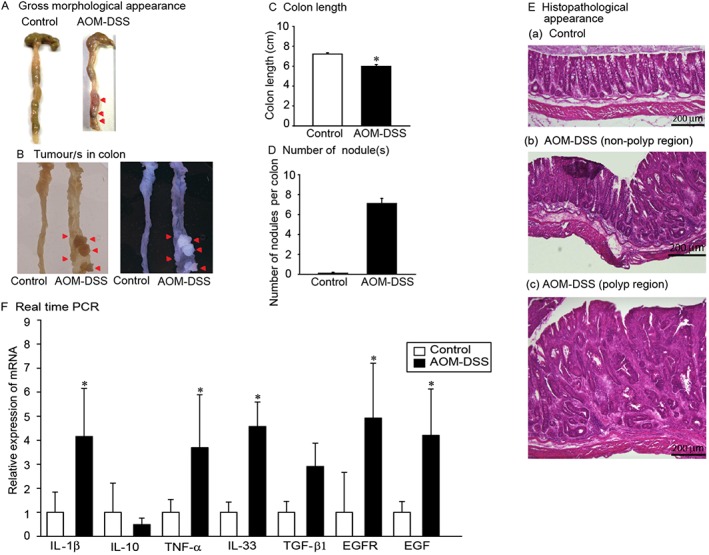

The AOM/DSS‐induced colitis mouse model is commonly used and is an excellent tool for understanding the pathophysiology of colon carcinogenesis. A single injection of AOM and cyclic administration of DSS in drinking water produced chronic colitis with characteristic symptoms, such as decreased body weight, soft faeces, diarrhoea and bloody diarrhoea, during the DSS cycles; conversely, the mice gradually became healthier during the water cycles. Gross pathological features observed included shortening of the colon, as well as large and small tumours in the mid and lower regions of the colon (Figure 1A‐D). Histopathological analysis revealed aberrant crypts, dysplasia and hyperplasia of crypts, and neoplasia in mice with AOM/DSS colitis (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Gross pathology, histopathology and mRNA analysis of colon tissue from mice with colitis induced by AOM/DSS. Control and colitis mice were analysed for the following: (A)gross colon lesions (red arrowheads), (B)tumour nodules (red arrowheads),(C)length of the colon,(D)number of nodules present in each colon and(E)histopathology of the mid‐colon of (a) control, (b) AOM/DSS non‐polyp and (c) AOM/DSS polyp regions. n = 5, Bar = 50 μm. (F)Quantitative real time PCR analyses of the mRNA levels of IL‐1β, IL‐10, TNF‐α, IL‐33, TGF‐β1, EGFR and EGF in control and AOM/DSS mice.*P < 0.05,significantly different from control mice n = 8.

We assessed mRNA levels of IL‐1β, IL‐10, IL‐33, TNF‐α, TGF‐β1, EGFR and EGF in the mid‐colon of AOM/DSS‐induced colitis mice and found significantly up‐regulated mRNA levels of IL‐1β, IL‐33, EGFR and EGF (Figure 1F).These observations provided further insight into the relationship between IL‐33 and other growth factors.

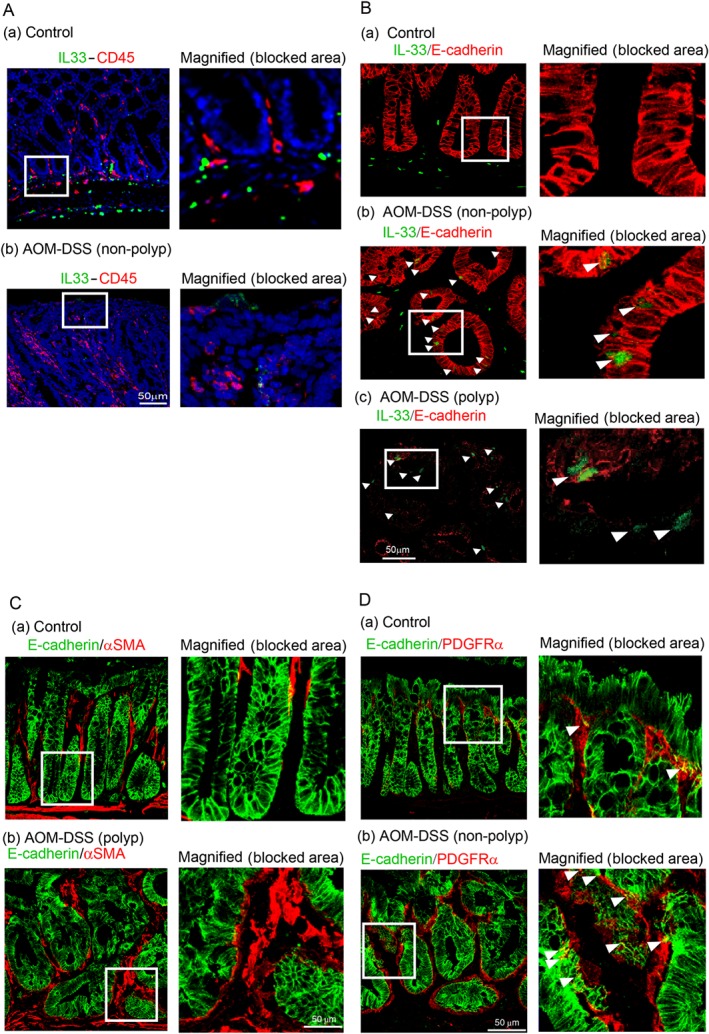

Mice with AOM/DSS colitis express epithelial cell‐derived IL‐33

The potential role of IL‐33 in AOM/DSS‐induced colitis mice was assessed. As IL‐33 expression was significantly increased throughout the colon, immunohistochemical analysis was used to identify the cell types that exhibit elevated IL‐33 expression in AOM/DSS‐induced colitis. Double immunostaining for CD45 and IL‐33 did not reveal any double positive cells, indicating that CD45 positive immune cells did not produce IL‐33 in the colon tissues (Figure 2A). However, double immunostaining for E‐cadherin and IL‐33 revealed many double positive immune cells (Figure 2B), whereas control mice did not express epithelial cell‐derived IL‐33. Control mice exhibited immune cells derived IL‐33 in the submucosal area and strong E‐cadherin staining in epithelial mucosa cells. In non‐polyp areas of AOM/DSS mice, E‐cadherin fluorescence intensity was similar to control mice;however, decreased E‐cadherin fluorescence intensity was observed in polyp areas. Double immunostaining with the epithelial cell marker E‐cadherin and the mesenchymal cell markers α‐smooth muscle actin (αSMA) and the PDGF α receptor (PDGFRα) was used to further characterize the IL‐33 producing cells. As expected, no cells were found to be positive for both E‐cadherin and αSMA(Figure 2C); however, cells that were positive for both E‐cadherin and PDGFRα (Figure 2D) were observed in both control and AOM/DSS colon tissues.

Figure 2.

Histopathology and expression of epithelial cell‐derived IL‐33 in mice with AOM/DSS colitis, a model of colon cancer. Immunohistochemistry of mid‐colon tissue from control and AOM/DSS‐induced colitis mice. (A)(a) IL‐33/CD45 immunohistochemistry in control tissue. Representative regions of IL‐33/CD45 staining are blocked and magnified in the right panel. (b) IL‐33/CD45 staining in tissue from AOM/DSS treated mice. Representative regions are blocked and magnified in the right panel. The staining demonstrates that CD45 positive cells do not produce IL‐33 in AOM/DSS colitis mice. (B) (a) Control mice do not show cells that are positively stained for both IL‐33 and E‐cadherin in the mid‐colon. AOM/DSS non‐polyp (b) and polyp (c) areas exhibit cells that stain positively for both IL‐33 and E‐cadherin. Arrowheads indicate epithelial cell‐derived IL‐33 staining in AOM/DSS‐induced colitis tissue. The representative blocked areas clearly indicate the epithelial derived IL‐33 positive cells in non‐polyp and polyp areas of AOM/DSS colitis tissues. (C)Epithelial mesenchymal‐like cells produce IL‐33 in mouse colon tissues. Immunohistochemical analysis of E‐cadherin/αSMA in (a) control and (b) AOM/DSS tissue. Blocked areas indicate magnified images of E‐cadherin/αSMA. (D) Immunohistochemical analysis of E‐cadherin/PDGFRα in (a) control and (b) AOM/DSS tissue. Blocked areas indicate magnified image of E‐cadherin/PDGFRα. Arrowheads indicate double positive epithelial mesenchymal‐like cells. n = 5, Bar = 50 μm.

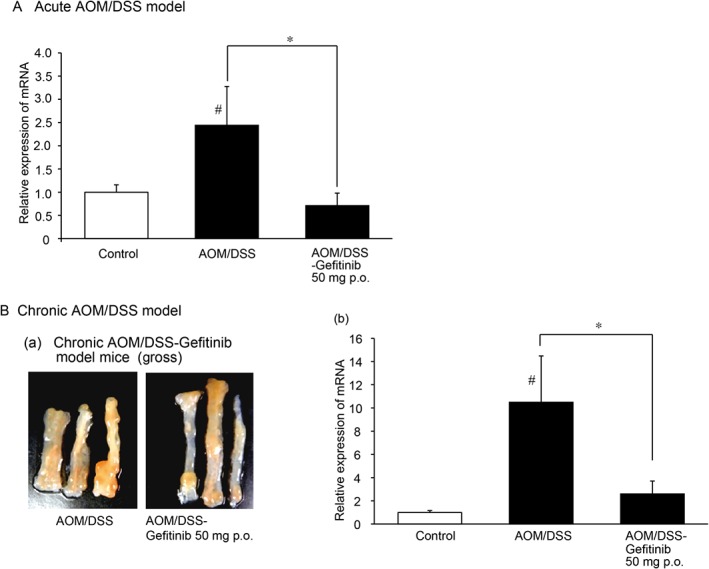

Gefitinib down‐regulates IL‐33 mRNA expression in mice with AOM/DSS colitis

Gefitinib, an orally active selective EGFR‐tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has been approved for the treatment of patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer (Herbst et al., 2004). In this study, we investigated the effects of gefitinib on IL‐33 gene expression in mice with acute or chronic AOM/DSS‐induced colitis. The vehicle‐treated mice in the acute and the chronic groups expressed a higher level of IL‐33 mRNA than the control mice. However, the mice treated with gefitinib (50 mg·kg−1p.o.) in the acute AOM/DSS model significantly down‐regulated IL‐33 mRNA levels compared with the vehicle treated mice (Figure 3A). On the other hand, in the chronic AOM/DSS model mice, gross pathology indicated that gefitinib (50 mg·kg−1p.o.) treatment reduced the number, shape and size of tumour nodules in the colon tissues (Figure 3B‐a). Further analyses showed that gefitinib treatment also significantly reduced IL‐33 gene expression in colon tissues in AOM/DSS mice compared with vehicle treated mice (Figure 3B‐b).

Figure 3.

Gefitinib inhibits IL‐33 gene expression in acute and chronic AOM/DSS‐induced colitis mice. (A)Quantitative real time PCR analyses of acute AOM/DSS model mice. The IL‐33 mRNA level in the mid‐colon in control, AOM/DSS and AOM/DSS‐gefitinib (50 mg·kg−1p.o.) treated mice was assayed. *P < 0.05. Control, n = 6; AOM/DSS‐vehicle, n = 6; AOM/DSS‐gefitinib (50 mg·kg−1) p.o., n = 6.(B)Gross lesions and quantitative real time PCR analyses of chronic AOM/DSS‐induced colitis mice. (a)Gross lesions in the colon in AOM/DSS and AOM/DSS‐gefitinib (50 mg·kg−1p.o.) treated mice. (b) Relative IL‐33 mRNA level in the mid‐colon in control, AOM/DSS‐vehicle and AOM/DSS‐gefitinib (50 mg·kg−1p.o.) treated mice. *P < 0.05 compared with AOM/DSS group;# P < 0.05 compared with control group. Control, n = 6; AOM/DSS‐vehicle, n = 6; AOM/DSS‐gefitinib (50 mg·kg−1) p.o., n = 6.

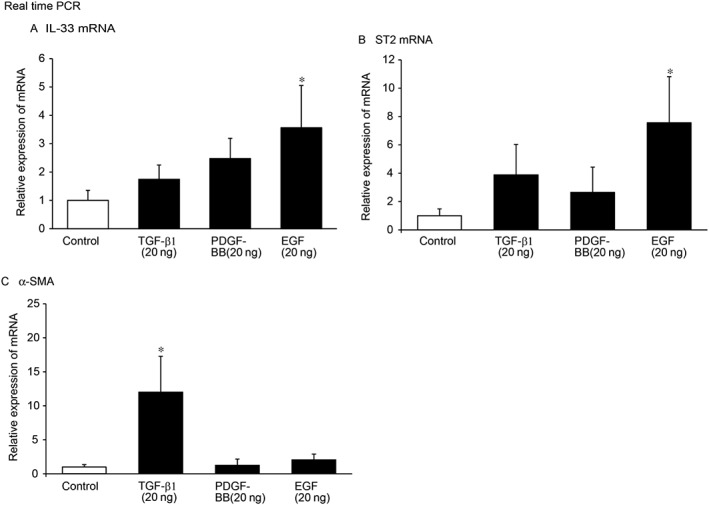

Effects of cytokines and growth factors on the IL‐33/ST2 axis in epithelial cells

IEC‐6 epithelial cells were used to examine the possible effects of growth factors, such as TGF‐β1, PDGF‐BB and EGF, on the IL‐33/ST2 axis. Cells treated with TGF‐β1 (20 ng·mL−1) for 24 h did not alter the expression levels of IL‐33 or ST2. However, TGF‐β1 significantly increased αSMA expression (Figure 4). Treatment with PDGF‐BB (20 ng·mL−1) for 24 h did not alter the IL‐33/ST2 or αSMA mRNA levels. Treatment of IEC‐6 cells with EGF (20 ng·mL−1) for 24 h significantly increased the expression of IL‐33 and ST2. These results suggest that EGF is a critical factor in regulation of the IL‐33/ST2 axis.

Figure 4.

Effects of TGF‐β1, PDGF‐BB and EGF on the IL‐33/ST2 axis in IEC‐6 cells. IEC‐6 cells were cultured and treated with TGF‐β1 (20 ng·mL−1), PDGF‐BB (20 ng·mL−1) or EGF (20 ng·mL−1) for 24 h. Quantitative real time PCR analyses of the mRNA levels of (A) IL‐33, (B) ST2 and (C) αSMA in control, TGF‐β, PDGF‐BB, and EGF‐treated cells.*P < 0.05 compared with control; n = 5.

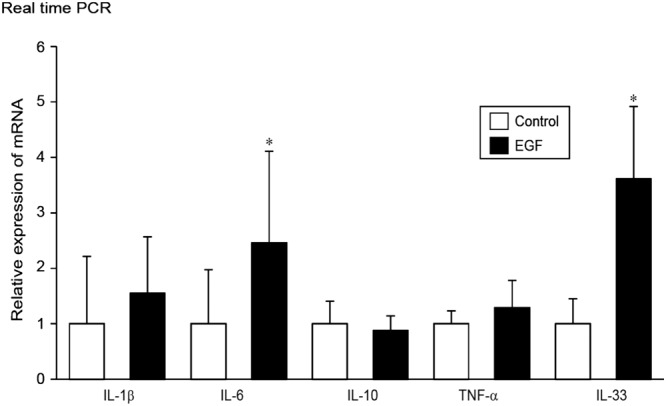

The association of EGF with pro‐inflammatory cytokines, such as IL‐1β, IL‐6 and TNF‐α, and the anti‐inflammatory cytokine IL‐10,was also examined in IEC‐6 cells. IEC‐6 cells treated with EGF (20 ng·mL−1) for 24 h exhibited increased levels of pro‐inflammatory cytokines. Quantitative real time PCR analysis showed that the levels of IL‐6, but not those of IL‐1β and TNF‐α, were significantly up‐regulated. Treatment with EGF did not alter IL‐10 mRNA levels in IEC‐6 cells (Figure 5). Notably, the expression of IL‐33was the highest among the cytokines tested in either the control or EGF‐treated cells (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Regulation of IL‐1β, IL‐6, IL‐10, TNF‐α and IL‐33 mRNA expression in IEC‐6 cells. IEC‐6 cells were cultured and treated with EGF (20 ng·mL−1) for 24 h followed by real time PCR analyses of the indicated mRNA levels. Quantitative real time PCR analyses of the mRNA levels of IL‐1β, IL‐6, IL‐10, TNF‐α and IL‐33 in control and EGF‐treated cells.*P < 0.05, compared with control; n = 5.

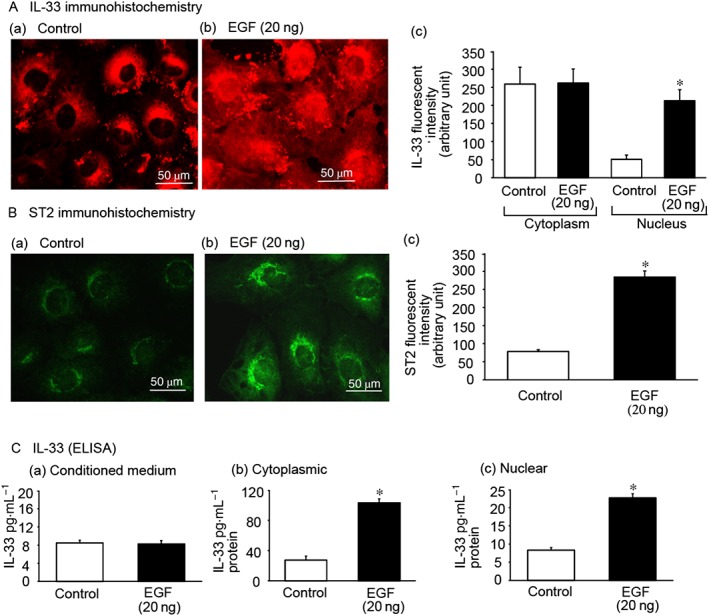

EGF treatment increases IL‐33 and ST2 protein expression

Immunohistochemical analysis of IEC‐6 cells indicated that cytoplasmic IL‐33 staining was observed in non‐treated cells, whereas EGF‐treated cells exhibited robust IL‐33 staining of both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Figure 6A). In IEC‐6 cells, cytoplasmic peri‐nuclear ST2 receptor staining was observed in control cells, whereas EGF‐treated cells exhibited robust ST2 receptor expression throughout the cytoplasm (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

EGF up‐regulates IL‐33/ST2 in IEC‐6 cells. IEC‐6 cells were treated with EGF (20 ng·mL−1) for 24 h. (A) IL‐33 immunohistochemistry: (a) control cells showing cytoplasmic IL‐33; (b) EGF‐treated cells showing cytoplasmic and nuclear expression of IL‐33; (c) significantly increased IL‐33 expression was observed in EGF‐treated cells in the nucleus. (B) ST2 immunohistochemistry: (a) control cells express moderate levels of ST2, (b) EGF‐treated cells express high levels of ST2 and (c) significantly increased ST2 expression in EGF‐treated cells was observed. (C) The effect of EGF on IL‐33 levels was analysed using an elisa method. (a) Conditioned medium, (b) cytosolic extracts and (c) nuclear extracts. Bar = 50 μm. *P < 0.05, compared with control; n = 5.

elisa was used to quantitate IL‐33 levels in IEC‐6 conditioned medium, as well as in the cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts of IEC‐6 cells. Control cells exhibited moderate IL‐33 quantities in the cytoplasmic extracts and low quantities in the nuclear extracts. EGF treatment of IEC‐6 cells significantly increased cytoplasmic and nuclear IL‐33 levels. However, it should be noted that EGF treatment did not produce a marked difference in IL‐33 levels in the conditioned medium (Figure 6C).

Discussion

In this study, we confirmed that AOM/DSS‐induced chronic colitis mice expressed aberrant crypts, dysplasia/hyperplasia of crypts, micro and tubular adenomas, invading the bowel wall and frequently infiltrated by T lymphocytes and other immune cells, as described by others (De Robertis et al., 2011). In addition to these observations, shortening of colon length and the presence of small, medium and large tumours in the lower part of the colon are typical phenomena. Quantitative real time PCR analyses of mid‐region colon tissue of AOM/DSS mice demonstrated the up‐regulation of pro‐inflammatory cytokines such as IL‐1β and IL‐33 as well as up‐regulated growth factors such as TGF‐β1 and EGF. We further investigated IL‐33 producing cells using double immunohistochemical staining. In control mice, IL‐33 producing epithelial cells were not detected whereas, in AOM/DSS colitis mice, a large number of IL‐33 producing epithelial cells were identified. It should be noted that IL‐33‐ producing cells were found in both the non‐polyp and polyp regions in mice with AOM/DSS colitis. Other cell types producing IL‐33 were assessed using different markers to identify non‐epithelial cells producing IL‐33. E‐cadherin, αSMA double immune‐positive cells producing IL‐33 were not observed. However, E‐cadherin, PDGFRα double positive cells producing IL‐33 was observed in both control and AOM/DSS mice. This finding suggests that, under physiological conditions, a subset of mesenchymal cells produce IL‐33 for colon homeostasis. These double positive cells were abundant in the dysplastic AOM/DSS colon in comparison with control mice. Nevertheless, the origin of these cells, whether native mesenchymal or epithelial mesenchymal transition cells, could not be ascertained. However, we could confirm that the IL‐33 producing cells were not CD45 positive immune cells. Recently, knockdown of genes has provided an important tool for the investigation of many physiological, pathological, pathophysiological and therapeutic functions in the animal body. Knockdown of ST2 in mice ameliorated skin inflammation (Hueber et al., 2011), suggesting a novel treatment strategy for inflammatory skin diseases. On the other hand, knockdown of the ST2 gene as well neutralization of the IL‐33/ST2 axis protected mice from acute inflammation in DSS‐induced colitis (Sedhom et al., 2012). These findings provide important clues for the role of the IL‐33/ST2 axis in the pathophysiology of intestinal inflammation and in colon cancer.

Gefitinib, an orally active selective EGFR‐tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has been approved for the treatment of patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer (Herbst et al., 2004). We found here that gefitinib significantly down‐regulated the IL‐33 mRNA level in mice with acute or chronic AOM/DSS colitis, which provided evidence for the involvement of the EGF signalling pathways in colon cancer pathophysiology. In the chronic AOM/DSS model mice, we further observed that gefitinib markedly reduced the shape, size and numbers of tumour nodules in colon tissues. Others have reported that gefitinib blocks the signal transduction pathways involved in proliferation, survival, host dependent processes and the regulation of cancer growth (Piechocki et al., 2008).

A well‐established IEC line (IEC‐6 cells) was chosen for the further study of the regulation of the IL‐33/ST2 axis in epithelial cells. These cells express TGF‐βR I and II (Rao et al., 2000), ST2 (Willems et al., 2012), EGFR (Real et al., 1986; Scheving et al., 1989; Tzouvelekis et al., 2013) and PDGFRα (data not shown). The in vivo study presented here indicated that pro‐inflammatory cytokines (IL‐1β and TNF‐α) and growth factors (TGF‐β1 and EGF) were up‐regulated in AOM/DSS mice along with IL‐33. We then identified the growth factor(s) that stimulated the IL‐33/ST2 axis by assessing the effects of TGF‐β1, PDGF‐BB and EGF. We found that stimulation of IL‐33/ST2 mRNA levels by TGF‐β1 and PDGF‐BB was negligible, whereas EGF strongly stimulated both IL‐33 and ST2 mRNA levels in IEC‐6 cells.

Next, the expression pattern of IL‐33/ST2 in IEC‐6 epithelial cells was examined. Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that IL‐33 is expressed in the cytoplasm of non‐treated control cells, whereas EGF‐treated cells exhibited robustIL‐33 expression in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm. By comparison, immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that IEC‐6 epithelial cells exhibited peri‐nuclear cytoplasmic expression of the IL‐33 transmembrane receptor ST2. However, upon EGF stimulation, dense ST2 expression was observed throughout the IEC‐6 cells.Similar findings have been reported by (Beltran et al., 2009) who showed cytoplasmic epithelial expression of IL‐33 in control patients and nuclear expression of IL‐33 and ST2 in epithelial cells of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The question then arises as to why IL‐33 is expressed in the cytoplasm of non‐treated control cells, while EGF‐treated cells express IL‐33 in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm. One possibility is that, under control conditions, cytoplasmic IL‐33 expression could serve certain physiological functions, while stimulation with EGF may induce IL‐33 expression and translocation into the nucleus where IL‐33 could participate in transcriptional regulation. Notably, we did not observe marked differences in IL‐33 levels in conditioned media from control and EGF‐treated cells, indicating that EGF does not stimulate IL‐33 secretion. The secretion patterns of IL‐33/ST2 are still being characterized and require further analyses of the secretory mechanisms of cells to assess their significance.

In summary, IL‐33/ST2 homeostasis in epithelial cells is controlled by EGF. EGF can be produced by many cells, including immune cells, and could trigger IL‐33 up‐regulation in chronic intestinal inflammation, without elevating the secretion of this cytokine into the extracellular space. The increased IL‐33 production during inflammation then can contribute to the biology of colon cancer. The EGF/IL‐33/ST2 axis represents a new potential therapeutic target for colon cancer.

Author contributions

M.S.I., H.O. and M.H. designed the research study, interpretation of data and manuscript preparation. M.S.I. performed most of the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. K.H. and S.I. performed part of the research and data analysis and approved the version to be published. N.K. and S.M. provided technical support and approved the version to be published. H.O. supervised the study and critical discussions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of transparency and scientific rigour

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organisations engaged with supporting research.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant numbers 25221205 and 24248050.

Islam, M. S. , Horiguchi, K. , Iino, S. , Kaji, N. , Mikawa, S. , Hori, M. , and Ozaki, H. (2016) Epidermal growth factor is a critical regulator of the cytokine IL‐33 in intestinal epithelial cells. British Journal of Pharmacology, 173: 2532–2542. doi: 10.1111/bph.13535.

References

- Abud HE, Watson N, Heath JK (2005). Growth of intestinal epithelium in organ culture is dependent on EGF signalling. Exp Cell Res 303: 252–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SP, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Catalytic receptors. Br J Pharmacol 172: 5979–6023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andoh A, Fujino S, Okuno T, Fujiyama Y, Bamba T (2002). Intestinal subepithelial myofibroblasts in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Gastroenterol 37 (Suppl 14): 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baekkevold ES, Roussigne M, Yamanaka T, Johansen FE, Jahnsen FL, Amalric F et al. (2003). Molecular characterization of NF‐HEV, a nuclear factor preferentially expressed in human high endothelial venules. Am J Pathol 163: 69–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltran CJ, Nunez LE, Diaz‐Jimenez D, Farfan N, Candia E, Heine C et al. (2009). Characterization of the novel ST2/IL‐33 system in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 16: 1097–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MJ, Bond RA, Spina D, Ahluwalia A, Alexander SP, Giembycz MA et al. (2015). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting: new guidance for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3461–3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Robertis M, Massi E, Poeta ML, Carotti S, Morini S, Cecchetelli L et al. (2011). The AOM/DSS murine model for the study of colon carcinogenesis: from pathways to diagnosis and therapy studies. J Carcinog 10: 9. doi: 10.4103/1477-3163.78279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey MR, Golovin A, Polk DB (2004). Epidermal growth factor‐stimulated intestinal epithelial cell migration requires Src family kinase‐dependent p38 MAPK signaling. J Biol Chem 279: 44513–44521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraldsen G, Balogh J, Pollheimer J, Sponheim J, Kuchler AM (2009). Interleukin‐33 – cytokine of dual function or novel alarmin? Trends Immunol 30: 227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst RS, Fukuoka M, Baselga J (2004). Gefitinib–a novel targeted approach to treating cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 4: 956–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueber AJ, Alves‐Filho JC, Asquith DL, Michels C, Millar NL, Reilly JH et al. (2011). IL‐33 induces skin inflammation with mast cell and neutrophil activation. Eur J Immunol 41: 2229–2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakkar R, Lee RT (2008). The IL‐33/ST2 pathway: therapeutic target and novel biomarker. Nat Rev Drug Discov 7: 827–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010). Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Lee HS, Chang KT, Ko TH, Baek KJ, Kwon NS (1995). Chloromethyl ketones block induction of nitric oxide synthase in murine macrophages by preventing activation of nuclear factor‐kappa B. J Immunol 154: 4741–4748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobori A, Yagi Y, Imaeda H, Ban H, Bamba S, Tsujikawa T et al. (2010). Interleukin‐33 expression is specifically enhanced in inflamed mucosa of ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol 45: 999–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd CM (2010). IL‐33 family members and asthma – bridging innate and adaptive immune responses. Curr Opin Immunol 22: 800–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopetuso LR, Scaldaferri F, Pizarro TT (2012). Emerging role of the interleukin (IL)‐33/ST2 axis in gut mucosal wound healing and fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 5: 18. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Lilley E (2015). Implementing guidelines on reporting research using animals (ARRIVE etc.): new requirements for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3189–3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AM (2011). Role of IL‐33 in inflammation and disease. J Inflamm 8: 22. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani N, Nabe T, Yoshino S (2014). IL‐17A promotes the exacerbation of IL‐33‐induced airway hyperresponsiveness by enhancing neutrophilic inflammation via CXCR2 signaling in mice. J Immunol 192: 1372–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita H, Arae K, Ohno T, Kajiwara N, Oboki K, Matsuda A et al. (2012). ST2 requires Th2‐, but not Th17‐, type airway inflammation in epicutaneously antigen‐sensitized mice. Allergol Int 61: 265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussion C, Ortega N, Girard JP (2008). The IL‐1‐like cytokine IL‐33 is constitutively expressed in the nucleus of endothelial cells and epithelial cells in vivo: a novel ‘alarmin’? PLoS One 3: e3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabe T (2014). Interleukin (IL)‐33: new therapeutic target for atopic diseases. J Pharmacol Sci 126: 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabe T, Wakamori H, Yano C, Nishiguchi A, Yuasa R, Kido H et al. (2015). Production of interleukin (IL)‐33 in the lungs during multiple antigen challenge‐induced airway inflammation in mice, and its modulation by a glucocorticoid. Eur J Pharmacol 757: 34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida A, Andoh A, Imaeda H, Inatomi O, Shiomi H, Fujiyama Y (2009). Expression of interleukin 1‐like cytokine interleukin 33 and its receptor complex (ST2L and IL1RAcP) in human pancreatic myofibroblasts. Gut 59: 531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichery M, Mirey E, Mercier P, Lefrancais E, Dujardin A, Ortega N et al. (2012). Endogenous IL‐33 is highly expressed in mouse epithelial barrier tissues, lymphoid organs, brain, embryos, and inflamed tissues: in situ analysis using a novel Il‐33‐LacZ gene trap reporter strain. J Immunol 188: 3488–3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piechocki MP, Dibbley SK, Lonardo F, Yoo GH (2008). Gefitinib prevents cancer progression in mice expressing the activated rat HER2/neu. Int J Cancer 122: 1722–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao JN, Li L, Bass BL, Wang JY (2000). Expression of the TGF‐beta receptor gene and sensitivity to growth inhibition following polyamine depletion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C1034–C1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Real FX, Rettig WJ, Chesa PG, Melamed MR, Old LJ, Mendelsohn J (1986). Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor in human cultured cells and tissues: relationship to cell lineage and stage of differentiation. Cancer Res 46: 4726–4731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon DS, Brandt R, Ciardiello F, Normanno N (1995). Epidermal growth factor‐related peptides and their receptors in human malignancies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 19: 183–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheving LA, Shiurba RA, Nguyen TD, Gray GM (1989). Epidermal growth factor receptor of the intestinal enterocyte. Localization to laterobasal but not brush border membrane. J Biol Chem 264: 1735–1741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, McClanahan TK et al. (2005). IL‐33, an interleukin‐1‐like cytokine that signals via the IL‐1 receptor‐related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2‐associated cytokines. Immunity 23: 479–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedhom MA, Pichery M, Murdoch JR, Foligne B, Ortega N, Normand S et al. (2012). Neutralisation of the interleukin‐33/ST2 pathway ameliorates experimental colitis through enhancement of mucosal healing in mice. Gut 62: 1714–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SPH et al. (2016). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucleic Acids Res 44 (Database Issue): D1054–D1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima S, Bando M, Ohno S, Sugiyama Y, Oshikawa K, Tominaga S et al. (2007). ST2 gene induced by type 2 helper T cell (Th2) and proinflammatory cytokine stimuli may modulate lung injury and fibrosis. Exp Lung Res 33: 81–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talabot‐Ayer D, McKee T, Gindre P, Bas S, Baeten DL, Gabay C et al. (2011). Distinct serum and synovial fluid interleukin (IL)‐33 levels in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and osteoarthritis. Joint Bone Spine 79: 32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi K, Yamamoto S, Hitomi E, Inada Y, Suyama Y, Sugioka T et al. (2014). Interleukin 33 is induced by tumor necrosis factor alpha and interferon gamma in keratinocytes and contributes to allergic contact dermatitis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 23: 428–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzouvelekis A, Ntolios P, Karameris A, Vilaras G, Boglou P, Koulelidis A et al. (2013). Increased expression of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF‐R) in patients with different forms of lung fibrosis. Biomed Res Int 2013: 654354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems S, Hoefer I, Pasterkamp G (2012). The role of the Interleukin 1 receptor‐like 1 (ST2) and Interleukin‐33 pathway in cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk assessment. Minerva Med 103: 513–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagami A, Orihara K, Morita H, Futamura K, Hashimoto N, Matsumoto K et al. (2010). IL‐33 mediates inflammatory responses in human lung tissue cells. J Immunol 185: 5743–5750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]