Abstract

Background and Purpose

5‐HT increases force and L‐type Ca2 + current (ICa,L) and causes arrhythmias through 5‐HT4 receptors in human atrium. In permanent atrial fibrillation (peAF), atrial force responses to 5‐HT are blunted, arrhythmias abolished but ICa,L responses only moderately attenuated. We investigated whether, in peAF, this could be due to an increased function of PDE3 and/or PDE4, using the inhibitors cilostamide (300 nM) and rolipram (1 μM) respectively.

Experimental Approach

Contractile force, arrhythmic contractions and ICa,L were assessed in right atrial trabeculae and myocytes, obtained from patients with sinus rhythm (SR), paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (pAF) and peAF.

Key Results

Maximum force responses to 5‐HT were reduced to 15% in peAF, but not in pAF. Cilostamide, but not rolipram, increased both the blunted force responses to 5‐HT in peAF and the inotropic potency of 5‐HT fourfold to sevenfold in trabeculae of patients with SR, pAF and peAF. Lusitropic responses to 5‐HT were not decreased in peAF. Responses of ICa,L to 5‐HT did not differ and were unaffected by cilostamide or rolipram in myocytes from patients with SR or peAF. Concurrent cilostamide and rolipram increased 5‐HT's propensity to elicit arrhythmias in trabeculae from patients with SR, but not with peAF.

Conclusions and Implications

PDE3, but not PDE4, reduced inotropic responses to 5‐HT in peAF, independently of lusitropy and ICa,L, but PDE3 activity was the same as that in patients with SR and pAF. Atrial remodelling in peAF abolished the facilitation of 5‐HT to induce arrhythmias by inhibition of PDE3 plus PDE4.

Abbreviations

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- pAF

paroxysmal AF

- peAF

permanent AF

- SR

sinus rhythm

Tables of Links

| TARGETS | |

|---|---|

| GPCRs a | Enzymes c |

| 5‐HT4 receptor | PKA, protein kinase A |

| Ion channels b | PDE3 |

| CaV1.2 channels | PDE4 |

| LIGANDS |

|---|

| 5‐HT |

| Cilostamide |

| IBMX |

| Ro 20‐1724 |

| Rolipram |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Southan et al., 2016) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 (a,b,cAlexander et al., 2015a, 2015b, 2015c).

Introduction

5‐HT increases contractile force, cAMP and the activity of cAMP‐dependent protein kinase (PKA) and hastens relaxation through 5‐HT4 receptors in trabeculae from the right (Kaumann et al., 1990; Sanders et al., 1995) or the left atrium (Sanders and Kaumann, 1992), obtained from patients with sinus rhythm (SR). 5‐HT also causes arrhythmias (Kaumann and Sanders, 1994) in right atrial trabeculae obtained from these patients. In human atrial myocytes from patients with SR, 5‐HT enhances L‐type Ca2 + current (ICa,L; Ouadid et al., 1992), Ca2 + transients (Christ et al., 2014) and contractile force (Sanders et al., 1995). Importantly, in myocytes, 5‐HT can elicit arrhythmic contractions (Sanders et al., 1995) and produces proarrhythmic spontaneous diastolic Ca2 + releases (Christ et al., 2014). It has been proposed that 5‐HT can initiate atrial fibrillation (AF) (Kaumann, 1994), the most common arrhythmia which increases risks for death, congestive heart failure and stroke (Lloyd‐Jones et al., 2004).

In atrial trabeculae from patients with chronic irreversible AF (recently classified as permanent AF, peAF, by Camm et al., 2010), however, the inotropic responses to 5‐HT are markedly reduced, and both 5‐HT‐evoked arrhythmias and spontaneous diastolic Ca2 + releases are abolished (Christ et al., 2014). Furthermore, the arrhythmogenic effects of 5‐HT, detected with electrophysiological methods, are reduced in peAF (Pau et al., 2007). As responses to 5‐HT, mediated through 5‐HT4 receptors in human atrium, are mediated via the cAMP/PKA pathways (Kaumann et al., 1990), we wondered whether the hydrolysis of cAMP by PDEs might be enhanced in peAF, thereby hindering inotropy and arrhythmias.

PDEs comprise 11 PDE families and 21 isoenzymes, of which PDE1, PDE2, PDE3, PDE4 (Bender and Beavo, 2006) and PDE8 (Patrucco et al., 2010) hydrolyse cAMP and are expressed in cardiac myocytes. PDE3, but not PDE4, partly controls the positive inotropic responses to 5‐HT in human atrial trabeculae obtained from patients with SR (Galindo‐Tovar et al., 2009). Inhibition of PDE3 and PDE4 facilitated catecholamine‐evoked arrhythmias in atrial trabeculae obtained from patients with SR, but the activity of PDE4 appears to be decreased in peAF (Molina et al., 2012). It is, however, unknown whether PDE3 and/or PDE4 limits the responses to 5‐HT of the atrial myocardium from patients with peAF.

Voigt et al. (2014) reported in patients with paroxysmal AF (pAF) an increased proarrhythmic diastolic Ca2 + leak from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. However, the effects of 5‐HT in pAF are unknown. We compared the effects of the PDE3 inhibitor cilostamide and the PDE4 inhibitor rolipram on the 5‐HT‐evoked increases in force, arrhythmias and ICa,L, in trabeculae and myocytes obtained from patients with SR, pAF and peAF.

Methods

Patients

These studies were approved by the Medical Faculty Ethics Committee of the Technical University Dresden; approval number EK 114082202, Technical University Dresden, Medical Faculty Carl Gustav Carus. The patients gave written informed consent. The clinical data of patients providing the tissue samples are shown in the Supporting Information Table S1.

Atrial trabeculae and contractile responses to 5‐HT

The methods for preparing trabeculae and myocytes and their use have been described in detail by Kaumann et al. (1990 and Christ et al. (2014) respectively. Briefly, after excision, right atrial appendages were immediately placed into oxygenated, modified Tyrode's solution and transported to the laboratory in less than 10 min. Up to eight trabeculae were dissected from one appendage at room temperature in modified Tyrode's solution containing (mM): NaCl 126.7, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 1.05, NaH2PO4 0.42, NaHCO3 22, EDTA 0.04, ascorbic acid 0.2 and glucose 5.0. The solution was maintained at pH 7.4 by bubbling with a mixture of 5% CO2 and 95% O2. Atrial trabeculae were mounted in pairs, attached to SWEMA 4‐45 strain gauge transducers in an apparatus containing the modified Tyrode's solution at 37°C and stretched as described (Gille et al., 1985). The effects of 5‐HT were investigated in the presence of (‐)‐propranolol (200 nM) to prevent possible effects of endogenously released noradrenaline (Kaumann et al., 1990). Contractile force was recorded and time to half relaxation (t 0.5) was obtained from fast speed tracings (400 data points per s) using Chart Pro for Windows version 5.51 analysis programme (ADI Instruments, Castle Hill, Australia). Any additional contraction besides the 1 Hz rhythm was considered as arrhythmic.

Isolation of myocytes and whole‐cell recording of ICa,L

The tissue was cut into small pieces, myocytes were isolated as described previously (Christ et al., 2004) and kept in storage solution (composition in mM: KCl 20, KH2PO4 10, glucose 10, K‐glutamate 70, β‐hydroxybutyrate 10, taurine 10, EGTA 10, albumin 1, pH 7.4 adjusted with KOH at room temperature. Only striated, rod‐shaped myocytes were used. The responses of the myocytes were measured in a small perfusion chamber placed on the stage of an inverse microscope. A system for rapid solution changes allowed application of drugs in the close vicinity of the cells (Cell Micro Controls, Virginia Beach, VA; ALA Scientific Instruments, Long Island, NY, USA). ICa,L was measured at 37°C with standard voltage‐clamp technique +(Axopatch 200, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA), ISO2 software was used for data acquisition and analysis (MFK, Niedernhausen, Germany) as described (Christ et al., 2004). Heat‐polished pipettes were pulled from borosilicate filamented glass (Hilgenberg, Malsfeld, Germany). Tip resistances were 3‐5 MΩ, seal resistances were 3‐6 GΩ. Cell capacitance (CM) was calculated from steady‐state current during depolarising ramp pulses (1 Vs‐1) from ‐40 mV to ‐35 mV. Five minutes after establishing the whole‐cell configuration ICa,L was measured during a test pulse from a holding potential of –80 mV at +10 mV. The experiments were performed with the following Na+‐free superfusion solution (in mM): tetraethylammonium chloride 120, CsCl 10, HEPES 10, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1 and glucose 20, pH 7.4 (adjusted with CsOH). The pipette solution (pH 7.2) included (in mM):Cs methanesulfonate 90, CsCl 20, HEPES 10, Mg‐ATP 4, Tris‐GTP 0.4, EGTA 10 and CaCl2 3, with calculated free Ca2+ concentration of ~60 nM (computer program EQCAL, Biosoft, Cambridge, UK), pH=7.2 (adjusted with CsOH). Current amplitude was determined as the difference between peak inward current and current at the end of the depolarising step.

Pretreatment with PDE inhibitors

Trabeculae and myocytes were pretreated with fixed concentrations of the PDE3 inhibitor cilostamide (300nM), the PDE4 inhibitor rolipram (1μM) or in combination (cilostamide + rolipram) at these concentrations. The concentrations of PDE inhibitors used here were based on earlier work (Galindo‐Tovar et al., 2009) The pretreatment was carried out by incubating the tissue in modified Tyrode's solution for 15min (trabeculae) or 2 min (myocytes), at 37oC, with or without the PDE inhibitors in the concentrations shown.

Experimental design and statistics

The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2015). To minimize variability between patients, experiments involving the action of 5‐HT with PDE inhibitors, were carried out on trabeculae or myocytes from the same atrium pre‐treated with the PDE inhibitors or serving as time‐matched control (TMC), followed by challenges with 5‐HT. Three to eight trabeculae were dissected from the atrial tissue of each patient. The trabeculae were distributed randomly in four organ baths, usually two per bath. The assignment of TMC, cilostamide, rolipram and their combination (cilostamide + rolipram) to the baths was randomized by drawing lots. When more than one cell or trabecula from a patient was available for one experimental group, mean values were calculated for individual patients. We determined a single cumulative concentration–effect curve for 5‐HT on each trabecula. Blinding did not apply for our experimental protocols.

The pEC50 (−logEC50) values (in M) for 5‐HT were estimated from fitting a Hill function with variable slopes to concentration–effect curves from individual experiments. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM of n = number of patients. Significance between means was assessed with the use of paired or non‐paired Student's t‐test or ANOVA, considering P < 0.05 statistically significant. The ANOVA test was used when there was no significant variance inhomogeneity. Furthermore, the repeated‐measures ANOVA test was followed by the post test (Bonferroni) only if the F‐test achieved P < 0.05, indicating effective matching (GraphPad 5.02; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

The incidence of arrhythmias was expressed as percentage of trabeculae showing arrhythmic contractions. Statistical comparisons of the incidence of 5‐HT‐evoked arrhythmias in the presence and absence of PDE inhibitors were carried out by logistic regression. A mixed‐effects logistic regression was used to model binary outcome variables, in which the log odds of the outcomes are modelled as a linear combination of the predictor variables when data are clustered or there are both fixed and random effects (http: //www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/stata/ado/analysis/). Muscle replicates were taken into account by adding them as random effects into the model. The results are expressed as odds ratios. The analysis was carried out with the R 3.1.1 software [R Core Team (2014) R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; URL http://www.R‐project.org/)].

Materials

5‐Hydroxytryptamine HCl, (‐)‐propranolol, IBMX (3‐isobutyl‐1‐methylxanthine), rolipram and cilostamide were purchased from Sigma Chemicals (Poole Dorset, UK). Rolipram and cilostamide were dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide and Tyrode's solution (20% dimethylsulphoxide in Tyrode's solution). Drugs were added to the organ bath so that the concentration of dimethylsulphoxide was less than 0.1%, which by itself did not modify contractile force.

Results

Comparison of inotropic and arrhythmic effects of 5‐HT in atrial trabeculae from patients with SR, pAF and peAF

5‐HT produced similar inotropic effects and incidence of arrhythmias in trabeculae of patients with SR or pAF (Figure 1). As found in our previous paper (Christ et al., 2014), in peAF, the inotropic effects of 5‐HT were markedly reduced and the arrhythmias virtually abolished (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The inotropic and arrhythmic effects of 5‐HT are markedly reduced in trabeculae of patients with peAF but not in those from patients with pAF. (A) Representative experiment. A trabecula of a patient with SR (top tracings) and a trabecula of a patient with peAF (bottom tracing) were set up into the same organ bath, and a concentration–effect curve for 5‐HT was determined. (B) Representative arrhythmia elicited by 100 nM 5‐HT in a trabecula from a patient with SR. (C) Inotropic effects. Each data point represents mean values ± SEM from the number of patients (trabeculae/patients, shown in parentheses). *P < 0.05; for maximum responses to 5‐HT for both SR versus peAF and pAF; (n.s.) non‐significant for SR versus pAF; non‐paired t‐test. ‐logEC50 values were calculated from individual concentration–effects curves. C, force in basal conditions. (D) Data of the percentage of trabeculae with arrhythmic contractions. Curves were fitted to mean values.

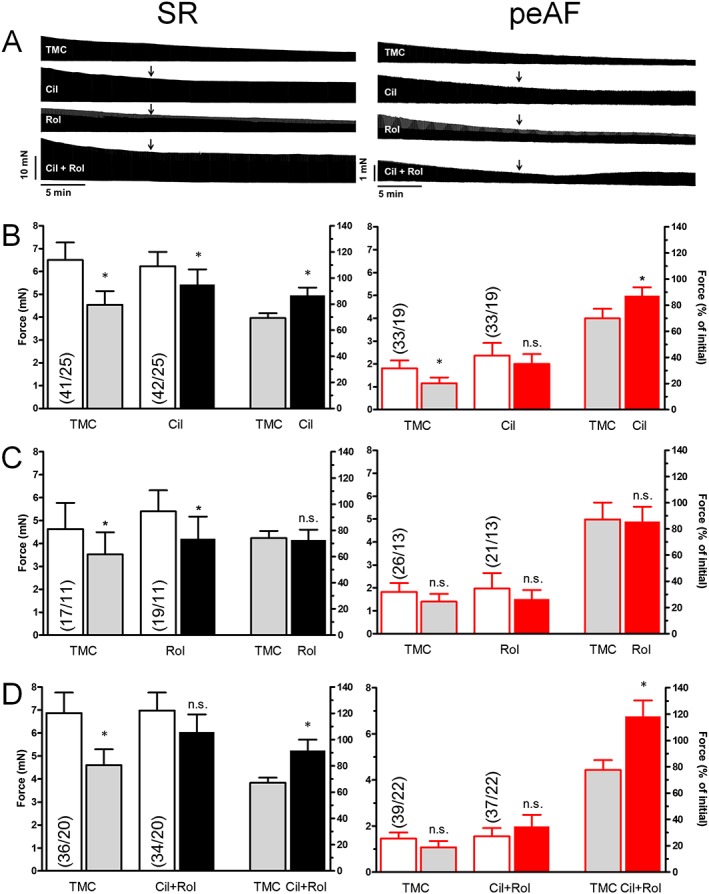

Cilostamide, but not rolipram, similarly increases basal force in trabeculae from patients with SR or peAF

Atrial contractile force is markedly reduced in peAF (Schotten et al., 2001; Christ et al., 2014), in part possibly due to overactive PDEs. We therefore compared the effects of the PDE3 inhibitor cilostamide and the PDE4 inhibitor rolipram on force generation in trabeculae from patients with SR and peAF. Force declined during 30 min in trabeculae from both patients with SR and peAF to a similar extent (when expressed as % of control), although the absolute values of force (in mN) in the tissue samples from patients with peAF were considerably smaller (Figure 2). After correction for the time‐dependent decline in force, cilostamide and the combination (cilostamide + rolipram) similarly increased basal force in trabeculae from both patients with SR or peAF (Figure 2), consistent with a similar regulation of basal force by PDE3 in the two groups. Rolipram alone was ineffective. The intrinsic effects of (cilostamide + rolipram), administered separately or in combination, were similar in trabeculae of patients with pAF to those in trabeculae of patients with SR or peAF (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Effects of cilostamide and rolipram on basal force of trabeculae from patients with SR and peAF. (−)−Propranolol was added for 15 min before the administration of the PDE inhibitors (PDEi, arrows). The time‐dependent decrease of basal force, shown at the representative tracings, is mainly due to the slow onset of the inverse agonist effect of (−)−propranolol at atrial β‐adrenoceptors. (A) Top panels show representative experiments from four trabeculae of a patient with SR and a patient with peAF. Panels B–D show statistical data with cilostamide (Cil; 300 nM), rolipram (Rol; 1 μM) and the combination (Cil + Rol) respectively. The four left‐hand bars in each panel are data of force (mN). The initial values of bars 1 and 3 were taken at a time immediately before the administration of the PDEs. The data of bars 2 and 4 were obtained at the end of the incubation with the PDEs. Columns 5 and 6 show the % change of force between TMC (bar 2) and initial (bar 1) and PDEi (bar 4) and initial (bar 3) respectively. Data are mean ± SEM values from the number of patients (trabeculae/patients, shown in parentheses). *P < 0.05; significant differences between pairs of columns; paired t‐test; n.s. non‐significant.

Figure 3.

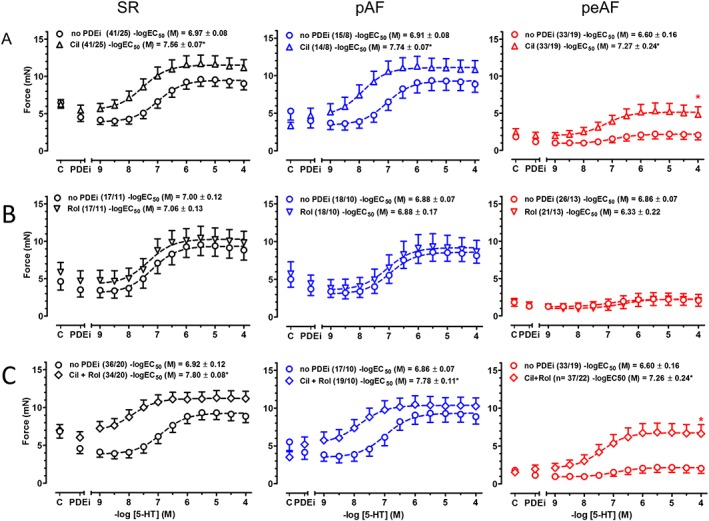

Potentiation of the inotropic effects of 5‐HT by cilostamide and (cilostamide + rolipram), but not by rolipram alone, in trabeculae from patients with SR, pAF and peAF. Panels shown in A–C represent cumulative concentration–effect curves of 5‐HT in the absence [no PDE inhibitor (PDEi), circles] and presence of cilostamide (Cil), rolipram (Rol) and (Cil + Rol) respectively, obtained from paired trabeculae from the same patient with SR, pAF or peAF. Mean ± SEM values of −logEC50 data in the absence and presence of a PDEi from the number of patients (trabeculae/patients, shown between parentheses) were compared with paired t‐tests. *P < 0.05. C, basal force.

Cilostamide, but not rolipram, potentiates the inotropic effects of 5‐HT

Cilostamide potentiated 4‐fold, 7‐fold and 4.5‐fold the effects of 5‐HT in trabeculae from patients with SR, pAF and peAF respectively, whereas rolipram was ineffective (Figure 3). The combination of (cilostamide + rolipram) increased 7.5‐fold, 9‐fold and 4.5‐fold the inotropic potency of 5‐HT in trabeculae from patients with SR, pAF and peAF respectively. The reduced maximum force response to 5‐HT in trabeculae from patients with peAF was increased by cilostamide and even more by (cilostamide + rolipram), but force did not reach the corresponding absolute maximum force level observed in trabeculae from patients with SR (Figure 3).

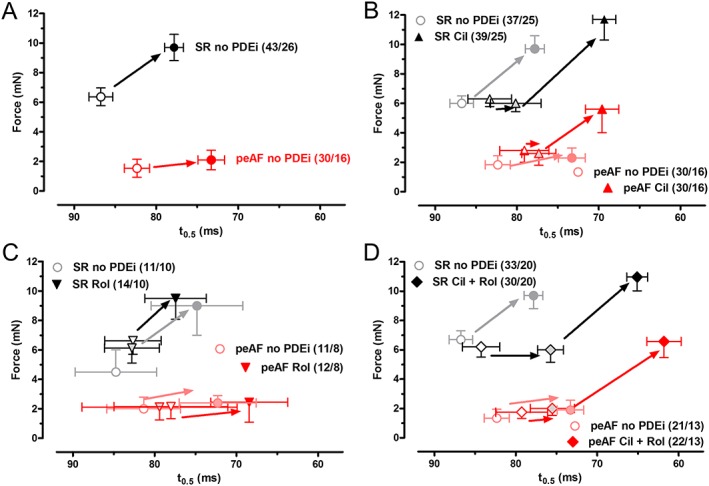

Cilostamide restores the relation between lusitropic and inotropic effects of 5‐HT in peAF

As recently found (Christ et al., 2014), the lusitropic effects of 5‐HT, characterized as a shortening of the time to half relaxation (t 0.5), were well preserved in peAF, while the inotropic effects were markedly blunted, compared with trabeculae from patients with SR (Figure 4). Here, we analysed the relationship between lusitropic and inotropic effects of 5‐HT. 5‐HT started reducing t 0.5 before increasing force in trabeculae from patients with SR (Figure 5A). Rolipram did not change the relationship between the 5‐HT‐evoked increases of force and the shortening of t 0.5 by 5‐HT in trabeculae from patients with SR and peAF (Figure 5C). However, in the presence of cilostamide or the combination of (cilostamide + rolipram) (Figure 5B, D), 5‐HT caused considerable increases in force almost without reduction of t 0.5 in trabeculae from patients with SR, resulting in a leftward shift of the force/t 0.5 relationship. In contrast, in peAF, the force/t 0.5 relationship became flat in the absence of PDE inhibitors (Figure 5). In peAF, cilostamide, but not rolipram, restored the steep relationship between force/t 0.5 responses to 5‐HT, as observed in trabeculae from patients with SR in the absence of the PDE inhibitor (Figure 5). In peAF and with concurrent (cilostamide + rolipram), 5‐HT produced a linear relationship between force and t 0.5 (Figure 5D).

Figure 4.

Similar hastening of relaxation, elicited by 5‐HT in atrial trabeculae from patients with SR or peAF. Relationship between increases in force and shortening of t 0.5, produced by maximally effective concentrations of 5‐HT. Data obtained in the absence of PDE inhibitors (PDEi) (A) and in the presence of cilostamide (Cil; B) rolipram (Rol; C) and (cilostamide + rolipram) (Cil+Rol; D). Data are mean ± SEM from the number of patients (trabeculae/patients, in parentheses) with peAF and SR. Data for rolipram, cilostamide and cilostamide plus rolipram are plotted together with the corresponding control values without any PDEi (in grey or light red).

Figure 5.

Cilostamide induces 5‐HT to enhance force with only minor hastening of relaxation in patients with SR and restores the relationship between force and t 0.5 responses to 5‐HT in trabeculae of patients with peAF. The relationship between increases in force and shortening of t 0.5, produced by increasing concentrations of 5‐HT in the absence of PDE inhibitors (PDEi) (A), presence of cilostamide (B), rolipram (C) and cilostamide plus rolipram (D). Data are mean ± SEM from the number of patients (trabeculae/patients, shown in parentheses). Pale symbols represent data in the absence of PDEi.

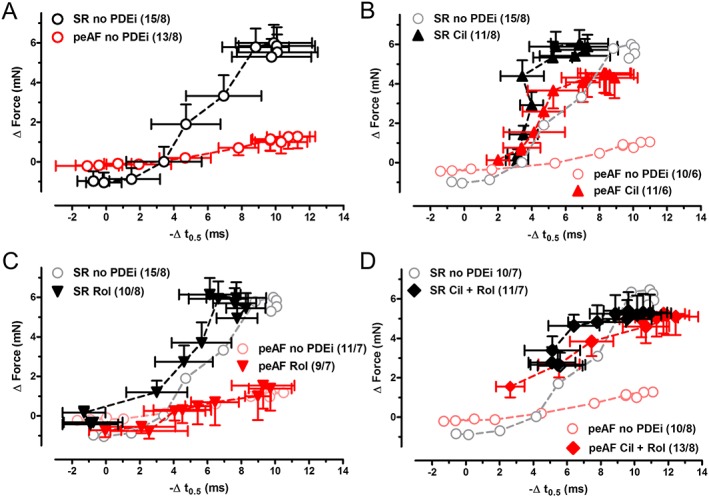

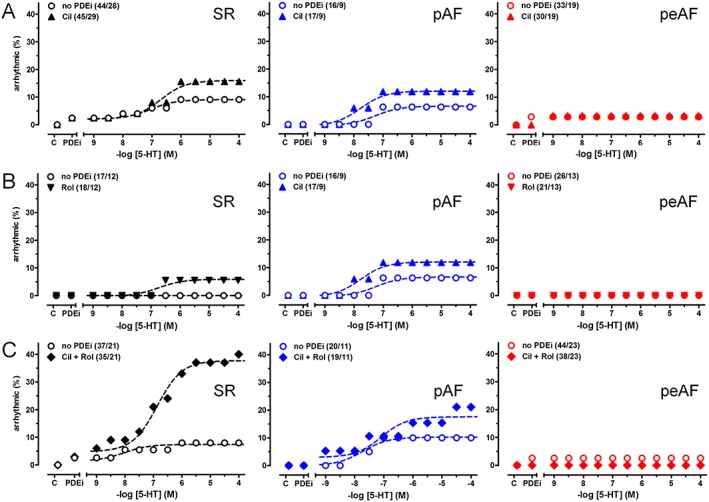

Concurrent (cilostamide + rolipram) facilitates 5‐HT‐evoked arrhythmias in trabeculae from patients with SR and pAF but not in those from patients with peAF

The incidence of arrhythmias elicited by 5‐HT (7%, Figure 1D) is lower than arrhythmias for catecholamines, mediated through β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors (17 and 14% respectively), in atrial trabeculae of patients with SR (Christ et al., 2014). 5‐HT produced arrhythmias in trabeculae from patients with pAF (Figures 1 and 6). The incidence of 5‐HT‐evoked arrhythmias in trabeculae from patients with SR and pAF was not significantly changed by cilostamide or rolipram (Figure 6A, B, Supporting Information Tables S2–S4). However, treatment with (cilostamide + rolipram) increased the incidence of 5‐HT‐evoked arrhythmias to 26% in trabeculae from patients with SR (P < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Concurrent (cilostamide + rolipram) facilitates 5‐HT‐evoked arrhythmias in trabeculae of patients with SR but not pAF and peAF. The influence of cilostamide (Cil), rolipram (Rol) and (cilostamide + rolipram; Cil+Rol) on the incidence of arrhythmias evoked by 5‐HT is shown in panels A–C respectively. C, arrhythmias in the absence of 5‐HT and PDE inhibitors (PDEi). The difference of the incidence of 5‐HT‐evoked arrhythmias between the absence and presence of cilostamide + rolipram was significant (P < 0.05). Data are mean ± SEM from the number of patients (trabeculae/patients shown in parentheses). For detailed statistical analysis, see the Methods section and the Supporting Information Tables S2‐S4.

5‐HT failed to elicit arrhythmic contractions in trabeculae from patients with peAF (in agreement with Christ et al., 2014), and neither cilostamide nor rolipram, administered separately or in combination, facilitated 5‐HT‐evoked arrhythmias (Figure 6, Supporting Information Table S3).

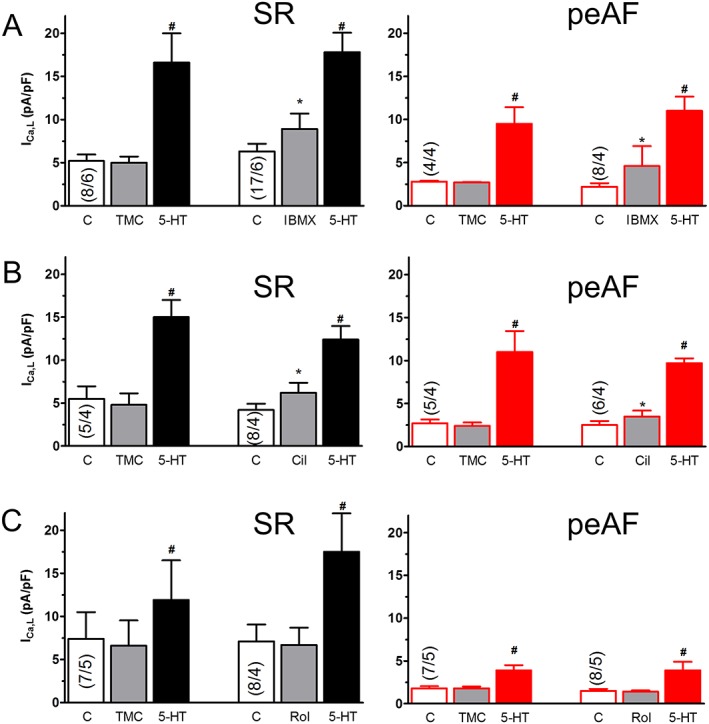

Cilostamide, rolipram or IBMX fail to enhance the responses of ICa,L to 5‐HT in myocytes from patients with SR or peAF

The calcium current ICa,L initiates electromechanical coupling, thereby contributing to the enhancement of contractile force and the facilitation of arrhythmias (Bers, 2002). To investigate the contribution of ICa,L to the recovery of the inotropic responses in peAF in the presence of the PDE inhibitors, the responses of ICa,L to 10 μM 5‐HT were compared in myocytes from patients with SR and peAF (Figure 7). IBMX (10 μM) was also used. IBMX and cilostamide (300 nM) increased ICa,L similarly in myocytes from patients with SR and peAF, but rolipram (10 μM) did not change ICa,L (Figure 7). The responses of ICa,L to 5‐HT were not increased by the three PDE inhibitors in myocytes of patients with SR or peAF (Figure 7). Thus, both the marked blunting of the inotropic responses to 5‐HT in peAF and their restoration by cilostamide are unrelated to the responses of ICa,L to 5‐HT.

Figure 7.

Cilostamide, rolipram and IBMX do not increase the response of ICa,L to 5‐HT in myocytes of patients with SR or peAF. The intrinsic activity of PDE inhibitors for ICa,L and their effect on the ICa,L response to 10 μM 5‐HT are shown for 10 μM IBMX (A), 300 nM cilostamide (Cil; B) and 1 μM rolipram (Rol; C). Data are mean ± SEM from the number of patients (myocytes/patients in parentheses) shown in the bars. IBMX or cilostamide, but not Rol, increased basal ICa,L in myocytes from patients with SR or with peAF. *P < 0.05; significant effect of IBMX or Cil. # P < 0.05, significant effect of 5‐HT; repeated‐measures ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. C control ICa,L.

Due to the limited availability of patients with pAF, it was only possible to obtain data of ICa,L with 10 μM 5‐HT from myocytes of patients with pAF not treated with PDE inhibitors. 5‐HT increased ICa,L density in these myocytes from 9.3 ± 0.8 to 20.7 ± 2.4 pA·pF−1 (P < 0.05), similar to the response to 5‐HT in myocytes from patients with SR (Figure 7).

Discussion

Our experiments have clearly shown that the inotropic and arrhythmic responses to 5‐HT were markedly reduced in peAF but not in pAF. Cilostamide increased similarly the basal force in SR and peAF. Cilostamide increased the force responses to 5‐HT in peAF, consistent with a control by PDE3. The combination of cilostamide + rolipram nearly restored the maximum response whereas rolipram alone had no effect. However, cilostamide caused similar potentiation of the inotropic effects of 5‐HT in trabeculae obtained from patients with SR, pAF and peAF, suggesting that atrial PDE3 activity is unchanged. Concurrent cilostamide + rolipram facilitated 5‐HT‐evoked arrhythmias in trabeculae from patients with SR but not peAF, suggesting that atrial remodelling in peAF prevents not only arrhythmias by 5‐HT but also their control by PDE3 and PDE4. These results lead us to reject our hypothesis that the blunted inotropic and arrhythmic responses in peAF were due to an increase of the activities of PDE3 and PDE4.

Similar responses of contractile force and ICa,L to PDE inhibitors in SR and peAF

Basal atrial force and ICa,L are markedly reduced in peAF (Van Wagoner et al., 1999; Schotten et al., 2001; Christ et al., 2014). However, the direct inotropic responses to cilostamide or the combination of cilostamide plus rolipram were similar in atrial trabeculae of patients with SR and peAF (Figure 2). Furthermore the increases of ICa,L by cilostamide and IBMX were also similar in SR and peAF (Figure 7). The inotropic responses to 5‐HT, reduced by PDE3 both in SR and peAF, appear therefore to occur without a contribution of PDE3 to the ICa,L responses. Our results also agree with our previous conclusion that the regulation of ICa,L by cAMP/PKA of the responses to 5‐HT does not differ between myocytes from patients with SR and peAF (Christ et al., 2014).

Our findings with the PDE inhibitors disagree with a report by Dinanian et al. (2008, who studied ICa,L in myocytes from patients with a cardiac pathology that predisposes to AF. These authors claimed that in mitral valve lesions and advanced heart failure, in addition to a marked down‐regulation of ICa,L, the non‐selective PDE inhibitor IBMX caused increased responses of ICa,L, compared to the responses in myocytes from patients with higher or normal basal ICa,L. However, these authors reported percentage responses to IBMX, not absolute responses in current density (ie Δ pA/pF‐1). Similar absolute responses to IBMX expressed in current density, as found by us in myocytes from patients with SR and peAF, would give higher % responses with the low basal ICa,L in peAF than with the high basal ICa,L in SR.

Blunted force responses to 5‐HT in peAF and their control by PDE3 occur independently of the effects of 5‐HT on ICa,L

In peAF, the maximum inotropic response to 5‐HT was reduced by 85% (Figure 1; Christ et al., 2014). The blunted inotropic responses to 5‐HT observed in peAF were restored by pre‐treatment with cilostamide or (cilostamide + rolipram) almost to the levels found in trabeculae from patients with SR, while rolipram alone had no effect (Figure 3). Thus PDE3, but not PDE4, modulated the force responses to 5‐HT in peAF, as previously found in SR (Galindo‐Tovar et al., 2009).

The maximum ICa,L responses to both 5‐HT and forskolin were reduced by only about 30% in peAF, and the dependence of the 5‐HT‐evoked activation of ICa,L on cAMP and/or PKA was the same in myocytes from patients with SR and peAF (Christ et al., 2014). Cilostamide and rolipram did not influence the response of ICa,L to 5‐HT in myocytes from patients with peAF and SR. Taken together, these results demonstrated that the ICa,L responses to 5‐HT were unrelated to the blunted inotropic responses to 5‐HT in peAF and not controlled by PDE3 and PDE4.

Changes of the relationship between the inotropic and lusitropic responses to 5‐HT by PDE3 activity in trabeculae from patients with SR and peAF

5‐HT activates the cAMP/PKA cascade through 5‐HT4 receptors in human atrium, thereby facilitating 5‐HT‐evoked relaxation (Kaumann et al., 1990). The PKA‐dependent phosphorylation of L‐type Ca2 + channels and proteins involved in myocardial relaxation, including phospholamban, as well as the expression of the Ca2 + ATPase of the sarcoplasmic reticulum, did not differ between atrial trabeculae from patients with SR or peAF, consistent with similar lusitropic effects of 5‐HT (Figure 4; Christ et al., 2014). 5‐HT at low concentrations hastens relaxation (i.e. reduces the time to half relaxation, t 0.5) without significantly increasing force in trabeculae from patients with SR. In contrast, in the presence of cilostamide, but not rolipram, low 5‐HT concentrations caused marked increases of force with only small reductions in t 0.5, resulting in a leftward shift of the force/t 0.5 relationship (Figure 5). This observation could be explained by a substantial Ca2 + release through the RyR2 channels of the sarcoplasmic reticulum, as a result of the selective phosphorylation of these channels. Such a mechanism would imply a greater sensitivity of RyR2 channels to PKA‐catalysed phosphorylation when local cAMP is enhanced by inhibition of PDE3, than phosphorylation of phospholamban, troponin I and myosin‐binding protein C to mediate hastening of relaxation. Alternatively, the association of PDE3 with RyR2 channels may be tighter than that of the proteins involved in hastening relaxation.

In peAF, the force/t 0.5 relationship for 5‐HT is markedly flattened (Figure 5A). In trabeculae of patients with peAF, cilostamide restored the steep force/t 0.5 relationship of 5‐HT observed in trabeculae from patients with SR in the absence of cilostamide (Figure 5B), consistent with a blunting of the force responses to 5‐HT in peAF by hydrolysis of cAMP by PDE3. However, the marked force responses to 5‐HT with only minor reduction of t 0.5 observed with cilostamide in trabeculae of patients with SR was not observed with cilostamide in peAF. Therefore, the possible selective sensitization of RyR2 channels to PKA‐dependent phosphorylation by inhibition of PDE3 with cilostamide would be blunted or even not occur in peAF. Clearly, these findings reveal complexities that need further investigation, especially at a biochemical level.

The joint control of 5‐HT‐induced arrhythmias by PDE3 and PDE4 in trabeculae of patients with SR is lost in peAF

Arrhythmias evoked by 5‐HT occur through spontaneous diastolic Ca2 + releases through RyR2 channels in myocytes of patients with SR, but this mechanism is blunted in myocytes of patients with peAF (Christ et al., 2014). One other related mechanism that may contribute to the inability of 5‐HT to produce arrhythmic contractions in peAF could be the high beating rate of the chronically fibrillating atrium. Greiser et al. (2014) reported that a persistent pacing of rabbit atria at high frequency for 5 days caused a decrease of RyR2 channels and increased Ca2 + buffering strength, as well as smaller and reduced RyR2 clusters in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. This ‘Ca2 + silencing’ was also observed in myocytes of patients with peAF. Taken together, the chronic tachycardia causes a silencing of subcellular Ca2 +, thereby reducing arrhythmogenic Ca2 + instability.

PDE4 has been proposed to protect against arrhythmias in human atrial myocardium (Molina et al., 2012). These authors reported that inhibition of PDE4 increased ICa,L, the frequency of spontaneous Ca2 + release and the incidence of arrhythmias evoked by catecholamines through β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors. Our results, demonstrating that rolipram did not increase the incidence of 5‐HT‐evoked arrhythmias in trabeculae from patients with SR (Figure 6B), even with a concentration of rolipram 10 times higher than that used by Molina et al. (2012), are inconsistent with a role for PDE4. Furthermore, we found that rolipram did neither increase ICa,L nor affect the responses to 5‐HT in myocytes of both patients with SR or peAF (Figure 7C). Our failure to detect an increase of ICa,L with rolipram could be related to different experimental conditions from those of Molina et al. (2012). These authors used the PDE4 inhibitor Ro 20‐1724 for their experiments with ICa,L, and their results were obtained at room temperature, whilst our experiments were carried out with rolipram at the physiological temperature of 37°C. We have assayed the effects of Ro 20‐1724 but found that this PDE4 inhibitor failed to increase ICa,L at both room temperature and 37°C as shown in the Supporting Information Figure S1.

Cilostamide failed to increase the incidence of 5‐HT‐evoked arrhythmias in trabeculae from patients with SR, inconsistent with a control by PDE3. However, the combination (cilostamide + rolipram) produced a significant increase of 5‐HT‐evoked arrhythmias (Figure 6C). One possible explanation is that cAMP, overflowing from a compartment where PDE3 has been inhibited by cilostamide, could reach a compartment where PDE4 can be activated through PKA‐catalysed phosphorylation and hydrolyse cAMP (MacKenzie et al., 2002). On the other hand, treatment with (cilostamide + rolipram) did not produce 5‐HT‐evoked arrhythmias in peAF. This is in marked contrast to the preserved control by PDE3 of the inotropic effects of cAMP in peAF. Thus, the hydrolysis of cAMP in the compartment in which PDE3, and perhaps PDE4, control arrhythmias might occur in a different intracellular compartment than the inotropic control, a possibility which requires further investigation.

Arrhythmias were defined as arrhythmic contractions of the trabeculae. Kaumann and Sanders (1994) reported that 5‐HT caused experimental arrhythmias in trabeculae from patients with SR and suggested that the arrhythmias could trigger AF. A limitation of the clinical relevance of our results with arrhythmias is, however, that triggered activity in a right atrial trabecula is equivalent neither to triggered firing of ectopic foci in the pulmonary veins nor to a re‐entrant mechanism that is supposed to sustain AF. The 5‐HT4 receptors also function in human left atrium from patients with terminal heart failure, increasing cAMP and activating PKA (Sanders and Kaumann, 1992), effects that could conceivably elicit AF. Hence, arrhythmic contractions could be a surrogate for clinically relevant arrhythmogenicity. Echocardiographic evidence has shown that both left and right atrium dilate in peAF (Van Gelder et al., 1991) and there is electrical remodelling in left and right atrial cells from patients with peAF (Voigt et al., 2010).

The incidence of 5‐HT‐evoked arrhythmias did not differ between atrial trabeculae from patients with pAF and those with SR. Voigt et al. (2014) reported an increased diastolic Ca2 + leak, associated with an increased Ca2 + load of the sarcoplasmic reticulum and hyperphosphorylation of phospholamban in unstimulated myocytes of patients with pAF. Although their observations led Voigt et al. (2014) to propose an increased arrhythmogenesis in pAF, this appears not to affect the incidence of arrhythmias evoked by 5‐HT in the trabeculae from patients with pAF, even in the presence of both cilostamide and rolipram, compared with trabeculae of patients with SR.

In conclusion, the results of this work are inconsistent with the hypothesis that the activity of PDE3 is increased in trabeculae of patients with peAF. The reduced maximum force response to 5‐HT in peAF samples is mainly related to the activity of PDE3. This control by PDE3 appears unchanged in trabeculae from patients with SR, pAF and peAF, because the PDE3 inhibitor cilostamide similarly potentiated the inotropic effects of 5‐HT in the three groups. As the responses of ICa,L to 5‐HT are similar and unchanged by IBMX, cilostamide or rolipram in myocytes of patients with SR or peAF, the blunted force response to 5‐HT in peAF appears unrelated to changes in ICa,L. Rolipram alone did not modify the inotropic and arrhythmic responses to 5‐HT in trabeculae from patients with SR, pAF or peAF, inconsistent with a role for PDE4. The lusitropic effects of 5‐HT are similar in trabeculae of patients with SR and peAF, but PDE3 changes the relationship between force and relaxation in trabeculae of patients with SR but not in those from patients with peAF. Concurrent treatment with cilostamide combined with rolipram increased the arrhythmogenic propensity of 5‐HT in trabeculae from patients with SR but not in the tissues from patients with peAF.

Author contributions

E.B., T.C., A.K. and M.K. performed the research. A.K., T.C., U.R. and M.K. designed the research study. S.S., E.B. and T.C. analysed the data. A.K. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of transparency and scientific rigour

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organisations engaged with supporting research.

Supporting information

Table S1 Characteristics of patients.

Table S2 Trabeculae from patients with sinus rhythm (SR).

Table S3 Trabeculae from patients with permanent AF (peAF).

Table S4 Trabeculae from patients with intermittent AF (pAF).

Figure S1 No effect of Ro 20‐1724 on ICa,L in human atrial cardiomyocytes.

Supporting info item

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Romy Kempe, Annegret Häntzschel and Trautlinde Thurm (Dresden) for excellent assistance and Klaus‐Dieter Soehren (Hamburg) for thorough analysis. The authors are grateful to Dr Silke Skytte Johansen (Hamburg) for performing statistical analysis of the incidence of arrhythmias. The work was supported by the German Centre for Cardiovascular Research (DZHK) and the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF).

Berk, E. , Christ, T. , Schwarz, S. , Ravens, U. , Knaut, M. , and Kaumann, A. J. (2016) In permanent atrial fibrillation, PDE3 reduces force responses to 5‐HT, but PDE3 and PDE4 do not cause the blunting of atrial arrhythmias. British Journal of Pharmacology, 173: 2478–2489. doi: 10.1111/bph.13525.

References

- Alexander SPH, Davenport AP, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: G Protein‐Coupled Receptors. Br J Pharmacol 172: 5744–5869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Catterall WA, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Voltage‐gated ion channels. Br J Pharmacol 172: 5904–5941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE et al. (2015c). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 172: 6024–6109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender AT, Beavo JA (2006). Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular regulation to clinical use. Pharmacol Rev 58: 488–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers DM (2002). Cardiac excitation–contraction coupling. Nature 415: 198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Schotten U, Savelieva I, Ernst S et al. (2010). European Heart Rhythm Association, European Association for Cardio‐Thoracic Surgery, guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 31: 2369–2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ T, Boknik P, Wöhrl S, Wettwer E, Graf EM, Bosch RF et al. (2004). L‐type Ca2+ current downregulation in chronic human atrial fibrillation is associated with increased activity of protein phosphatases. Circulation 110: 2651–2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ T, Rozmaritsa N, Engel A, Berk E, Knaut M, Metzner K et al. (2014). Arrhythmias, elicited by catecholamines and serotonin, vanish in human chronic atrial fibrillation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111: 11193–11198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MJ, Bond RA, Spina D, Ahluwalia A, Alexander SPA, Giembycz MA et al. (2015). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting: new guidance for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3461–3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinanian S, Boixel C, Juin C, Hulot J‐S, Coulombe A, Rücker‐Martin C et al. (2008). Downregulation of the calcium current in human right atrial myocytes from patients in sinus rhythm but with a high risk of atrial fibrillation. European Heart Journal 29: 1190–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo‐Tovar A, Vargas ML, Escudero E, Kaumann AJ (2009). Ontogenic changes of the control by phosphodiesterase‐3 and ‐4 of 5‐HT responses in porcine heart and relevance to human atrial 5‐HT4 receptors. Br J Pharmacol 156: 237–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gille E, Lemoine H, Ehle B, Kaumann AJ (1985). The affinity of (‐)‐propranolol for β1‐ and β2‐adrenoceptors of human heart. Differential antagonism of the positive inotropic effects and adenylate cyclase stimulation by (‐)‐noradrenaline and (‐)‐adrenaline. Naunyn‐Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol 331: 60–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiser M, Kerfant BG, Williams GS, Voigt N, Harks E, Dibb KM et al. (2014). Tachycardia‐induced silencing of subcellular Ca2 + signaling in atrial myocytes. J Clin Invest 124: 4759–4772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumann AJ (1994). Do human atrial 5‐HT4 receptors mediate arrhythmias? Trends Pharmacol Sci 15: 451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumann AJ, Sanders L (1994). 5‐Hydroxytryptamine cause rate‐dependent arrhythmias through 5‐HT4 receptors in human atrium: facilitation by β‐adrenoceptor blockade. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 348: 536–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumann AJ, Sanders L, Brown AM, Murray KJ, Brown MJ (1990). A 5‐hydroxytryptamine receptor in human atrium. Br J Pharmacol 100: 879–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd‐Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS et al. (2004). Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 110: 1042–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie SJ, Baillie GS, MacPhee I, MacKenzie C, Seamons R, McSorley T et al. (2002). Long PDE4 cAMP specific phosphodiesterases are activated by protein kinase A‐mediated phosphorylation of a single serine residue in upstream conserved region 1 (UCR1). Br J Pharmacol 136: 421–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina CE, Leroy J, Xie M, Richter W, Lee I‐O, Maack C et al. (2012). Cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase type 4 protects against atrial arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol 59: 2182–2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouadid H, Seguin J, Dumuis A, Bockaert J, Nargeot J (1992). Serotonin increases calcium current in human atrial myocytes via the newly described 5‐hydroxytryptamine4 receptors. Mol Pharmacol 41: 346–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrucco E, Albergine MS, Santana LF, Beavo JA (2010). Phosphodiesterase 8A (PDE8A) regulates excitation–contraction coupling in ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 49: 330–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pau D, Workman AJ, Kane KA, Rankin AC (2007). Electrophysiological and arrhythmogenic effects of 5‐hydroxytryptamine on human atrial cells are reduced in atrial fibrillation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 42: 54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders L, Kaumann AJ (1992). A 5‐HT4‐like receptor in human left atrium. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 345: 382–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders L, Lynham JA, Bond B, DelMonte F, Harding S, Kaumann AJ (1995). Sensitization of human atrial 5‐HT4 receptors by chronic β blocker treatment. Circulation 92: 2526–2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotten U, Ausma J, Stellbrink C, Sabatschus I, Vogel M, Frechen D et al. (2001). Cellular mechanisms of depressed atrial contractility in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. Circulation 103: 691–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SPH et al. (2016). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucl Acids Res 44 (Database Issue): D1054–D1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gelder IC, Crijns HJ, Van Gilst WH, Hamer HPM, Lie KI (1991). Decrease of right and left atrial sizes after direct‐current electrical cardioversion in chronic atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 67: 93–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagoner DR, Pond AL, Lamorgese M, Rossie SS, McCarthy PM, Nerbonne JM (1999). Atrial L‐type Ca2+ currents and human atrial fibrillation. Circ Res. 85: 428–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt N, Heijman J, Wang Q, Chiang DY, Li N, Karck M et al. (2014). Cellular and molecular mechanisms of atrial arrhythmogenesis in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Circulation 129: 145–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt N, Trausch A, Knaut M, Matschke K, Varro A, Van Wagoner DR et al. (2010). Left‐to‐right atrial inward rectifier potassium current gradients in patients with paroxysmal versus chronic atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 3: 472–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Characteristics of patients.

Table S2 Trabeculae from patients with sinus rhythm (SR).

Table S3 Trabeculae from patients with permanent AF (peAF).

Table S4 Trabeculae from patients with intermittent AF (pAF).

Figure S1 No effect of Ro 20‐1724 on ICa,L in human atrial cardiomyocytes.

Supporting info item