Abstract

The Republic of Maldives (Maldives) is an island nation in the Indian Ocean with a population of 344, 023. Studies show that Maldives has one of the world’s highest thalassemia carrier rates. It is estimated that 16–18 % of the Maldivians are β-thalassemia carriers, and approximately 28 new β-thal cases are recorded annually. Poor uptake of screening for the condition is one of the main reasons for this high number of new cases. The aim of this study was to explore the reasons for not testing for thalassemia in Maldives before or after marriage. Findings show that participants did not undergo carrier tests because of poor awareness and not fully knowing the devastating consequences of the condition. The outcomes of not testing were distressing for most participants. Religion played a vital role in all the decisions made by the participants before and after the birth of a β-thal child.

Keywords: Maldives, Thalassemia, Premarital testing, Genetic screening

Introduction

Thalassemias are described as “inherited autosomal recessive disorders characterized by reduced rate of hemoglobin synthesis due to a defect in α or β-globin chain synthesis” (Chiruka and Darbyshire 2011, p. 353). According to Webster’s New World Medical Dictionary (2008), a homozygous β-thalassemia patient (β-thal) is someone who is transfusion-dependent due to severe anemia caused by underproduction or absence of beta chains and hence, underproduction of hemoglobin. It is one of the most common hereditary disorders reported in the world. Estimates show that 3 % of the world population is heterozygous for β-thalassemia with more than 200 different mutations and each year, more than 300,000 children are born with severe β-globin disorders (Birgens and Ljung 2007).

The main primary prevention strategy used in thalassemia endemic countries is awareness with premarital screening and genetic counseling. Screening and genetic counseling are effective in some communities, while they have little impact in others because many do not undertake screening test for thalassemia for a variety of reasons including lack of awareness (Al-Farsi et al. 2014). Gender, education level, age, being single, and income level also contribute to unwillingness to participate in premarital screening (Al-Farsi et al. 2014). In addition, carriers sometimes refuse genetic screening or testing due to cultural reasons (Zeinalian et al. 2013) and from fear of stigmatization (Fahad et al. 2012; Verma et al. 2011; Widayanti et al. 2011). Additionally, the nature of the disease (carriers are normally healthy) and denial were additional reasons why some people do not want to be tested voluntarily for genetic conditions such as thalassemia (Garewal et al. 2005) as well as, cost and difficulty of accessing the services (Saxena and Phadke 2002).

Maldives

Maldives is an archipelago of 90, 000 km2 in the Indian Ocean, southwest of Sri Lanka (World Health Organization 2010). It has 1192 low-lying coral islands divided into 20 atolls for administrative purposes, and 194 of those islands are inhabited. Population of the islands ranges from a few hundred to more than 100,000 in the capital Male’ (National Bureau of Statistics 2015). The registered local population of Maldives as of 2014 was 344, 023 (National Bureau of Statistics 2015). The life expectancy of Maldivians is reported as 77 years for men and 79 years for women (World Health Organization 2015). The population of Maldives is 100 % Sunni Muslim by law (Ministry of Legal Reform Information and Arts 2008), and Dhivehi is the local language. Country development indicators show that Maldives has a literacy rate of 98 % (United Nations Children’s Fund 2014).

Thalassemia in Maldives

Genetic studies indicate a strong genetic link between Maldives and mainland Southeast Asia with multiple, independent immigration events and asymmetrical migration common across the country (Pijpe et al. 2013). Thalassemia is the most common genetic disorder in Maldives. It is not clear how thalassemia evolved in Maldives, but there are few studies that imply that the high β-thalassemia carrier rate of Maldives is due to the selective advantage that thalassemia carriers confer against Malaria (Firdous et al. 2011). Maldives has a β-thalassemia prevalence rate of 16–18 % (Angastiniotis 2014).

The first national thalassemia program of Maldives was an awareness program with screening and counseling (World Health Organization 2003). It was initiated by the non-governmental organization, Society for Health Education (SHE) in 1992 (Firdous 2005). With new insights into the problem provided by SHE, the government of Maldives recognized its magnitude and established The National Thalassemia Centre (NTC) of Maldives in 1994. NTC was later merged with National Blood Transfusion Services to form Maldives Blood Services (MBS) in 2012. MBS provides treatment for β-thal patients and carrier testing for the public. As of August 2014, a cumulative total of 803 thalassemia patients were registered with MBS and a total of 563 were living (Angastiniotis 2014). At present, screening is available from SHE and MBS; both of those centers are situated in the capital city Male’. The screening services for outreach populations are provided by the mobile teams of SHE (Firdous 2005). However, there are many who travel and visit the two screening centers in Male’ to get screened at their own expense. According to Firdous et al. (2011), the thalassemia Register of Maldives shows a fall of more than 60 % affected birth prevalence since screening was established.

Thalassemia test result is considered as a “must document” in Male’ by the family court for marriage since 2002 (Ahmed Abdulla, marriage registrar of family court of Maldives, personal communication, June 16, 2012). That rule was only fully implemented in the capital Male’ because access to testing in atolls is not readily available and is very much dependent on the visits of the mobile teams, which are often infrequent and the schedules for which are often not publicized. In spite of that, the standard marriage registration form is common for the whole of Maldives and it is recommended that all intending couples do premarital testing even if the intending couple lives on an island other than Male’. The Thalassemia prevention law of Maldives that was enacted in 2012 mandates all Maldivians be tested before the age of 18, and test results are required to be presented by all Maldivians in order to get married (Peoples’ Majlis 2012). Eighteen years is the earliest age a person can legally get married in Maldives. The mandatory testing under the new law is, however, a precautionary measure only. Marriages between carriers are still legal in Maldives.

Despite awareness raising efforts and free screening, a number of new cases of thalassemia are recorded annually. The records of the Ministry of Health of Maldives (2013) show that an average of 28 new cases were registered each year for the previous decade, which is a high incidence rate given the population size of Maldives and a worrying issue. This study was the first part of a larger study that examined primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of the thalassemia prevention program of Maldives. The aim of the broader study was to examine the effectiveness of thalassemia control measures at the respective levels. The aims of this component of the study were to explore the reasons for couples marrying without premarital screening for thalassemia in Maldives and to explore the reasons for married couples having children without the screening after the introduction of the screening services in 1992.

Method

A Generic Qualitative Approach (Caelli et al. 2003) using face-to-face in-depth interviews (Kvale 2007) was utilized for this study to enable us to explore the participants’ perspectives and reasons for their decisions in relation to the objectives of the study.

Participants and sampling

We used purposive sampling (Merriam 2009) to select participants who could provide detailed and nuanced information. To be included in the study, participants were required to be Maldivians who married without knowing their thalassemia carrier status and have had a β-thal child or children after the year 1992; thalassemia screening was introduced in Maldives in 1992. Only biological parents were invited for the study. As there was no register of the parents of children affected by severe thalassemia in Maldives, the first author (FW) visited the main transfusion center of Maldives (MBS) on several occasions and personally approached the parents of β-thal children during transfusion. Most patients, irrespective of their age, were accompanied by their parents during their transfusion. During those interactions, the contact details of the parents who showed interest in participating in the study were recorded and later cross-checked against inclusion criteria to ensure they were eligible to be included. Special care was taken during final selection to ensure participation from all possible atolls of Maldives.

We commenced the main study in February 2013; however, interviews were purposely postponed until April 2013 (school study-break). This allowed access to participants when many parents from the islands visited the MBS to consult the doctors and do regular three monthly or six monthly ferritin tests for their thalassemia-affected children. Through this delay, there was an opportunity to meet many visitors from atolls who normally do their transfusions in island/atoll level health centers and thus, potentially be included in this study. The final sample comprised of 14 women and 8 men from 10 different atolls.

Data collection

The interviews were conducted by FW in the Maldivian local language Dhivehi, using an interview guide that was developed based on the literature. Each interview lasted approximately 1 h and was digitally recorded for analysis purposes. The intent was to interview the participants individually because it would provide a greater opportunity for the participants to express their perspectives more freely. However, a few preferred to be interviewed with their partner, as couples. Accordingly, 16 individuals (no individual had their partner in this group) and three couples were interviewed for the study. Fourteen individuals and one couple were interviewed in the private room provided by the MBS for this study, and two individuals and two couples preferred to be, and were, interviewed at their own home.

Data analysis

Data collection and analysis occurred concurrently which enabled moving back and forth between the data and analysis. That process was flexible as suggested in Merriam (2009) and enabled the interviewer to guide participants more appropriately in subsequent interviews by incorporating important issues raised in previous interviews. A thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (2006) was undertaken by FW in collaboration with the other authors. In the first stage of data analysis, FW listened to the interviews, wrote memos, and recorded initial impressions about the interviews in a field journal. Recorded interviews were then translated from Dhivehi to English by FW and transcribed concurrently. During translation and transcription, extra care was taken to ensure that contextual, cultural, and emotional meaning of Dhivehi language was preserved. As a next step, FW read the transcripts several times in order to become familiar with the data. This was followed by an open coding process where concepts—significant statements and phrases related to the research aims—were identified and openly coded. Next, potential themes and relevant data were identified using the broadly coded concepts in the initial stage. All potential themes were then further reviewed to refine them. As a final stage, all the refined themes were re-examined to clearly define and name them before producing the final report. All the open coding was done by FW as she is a local Maldivian familiar with culture, religion, and local language with CF, AA, and DS involved in the latter stages. The qualitative data analysis program NVivo 10 was utilized to assist with data storage, management, analysis, and interrogation.

Results

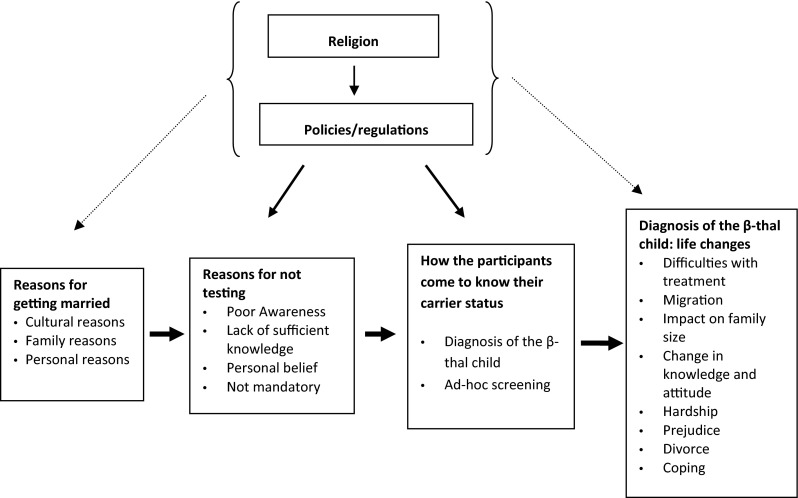

Being a carrier and a parent of a β-thal child was a particularly emotional issue for the participants. Their decisions to get married without premarital testing or not doing the test before having a child changed their lives. The birth of a β-thal child and the complex care needed for them adversely affected the everyday life of our study participants. Since all the participants were Sunni Muslims, their decisions and attitudes before and after the birth of the β-thal child were influenced by Islam and its teachings in many ways. We initially report the demographics and participants’ reasons for getting married followed by their reasons for not testing. This is followed by how participants came to know their carrier status and the consequences of giving birth and having to care for a β-thal child. Figure 1 shows how the findings of this study are linked and are shaped by Islam.

Fig. 1.

Reasons for not testing for thalassemia and its consequences in Maldives

Demographics

The study participants included more women (14) than men (8). Participants resided on islands in the north, south, and middle parts of Maldives and their ages ranged from 30 to 53 years. All men were employed while seven of the women were either self-employed or worked in government. The educational background of the participants varied from basic to postgraduate education. All participants except five were married to the mother/father of the child. Four participants were divorced and living separately at the time of the study. The husband of one participant passed away a few months before this study. Table 1 details participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Participant characteristics | No of participants |

|---|---|

| Total (16 individuals and 3 couples) | 22 |

| No. of men | 8 |

| No. of women | 14 |

| Participants’ residential area | |

| North of Male’ | 10 |

| Male’ | 7 |

| South of Male’ | 5 |

| Age of the participants | |

| 30–40 years | 11 |

| 41–above | 11 |

| Year of marriage | |

| Before 1992 | 7 |

| After 1992 | 15 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 17 |

| Divorced | 4 |

| Widowed | 1 |

| Related to the partner | |

| Not related at all | 16 |

| Distant relatives (third cousin or further) | 5 |

| Second cousins | 1 |

| Employment | |

| Employed | 15 |

| Not employed | 7 |

| Education level | |

| Completed basic education | 4 |

| Completed primary education (Grade 5) | 2 |

| Completed middle school (Grade7) | 11 |

| Completed secondary school or higher | 5 |

| Testing center | |

| Society for Health Education (SHE) | 6 |

| Maldives Blood Services (MBS) | 12 |

| Have not tested yet | 4 |

| No of β-thal children | |

| More than one child | 1 couple and 5 individuals |

| Only one child | 2 couples and 11 individuals |

Reasons for getting married

According to our participants, cultural and societal expectations of marriage were shaped by Islam in many ways. The participants provided a range of reasons for their marriage, and they are presented here as cultural and religious, family and personal factors.

Marrying in accordance with cultural and religious practice was dominant in participant interviews. Most participants described finding a partner and dating for some time before marriage as the custom in Maldives, but living together before marriage was described as inappropriate. All participants except three selected their own marriage partners and dated for more than 6 months before marrying. They described dating and consequent familiarity, closeness, and comfort led to a marriage in most cases. For example, one participant stated, “We started dating while very young. Dating continued for about three years and then (we) married.”

Even though Islam does not encourage dating before marriage, many cultural aspects of marriage in this study were related to Islamic teachings. Marriage is sacred in Islam. Islamic teachings and marriage advice given by Ghazis (a Government employed lawyer to conduct marriage on behalf of government) stress that prospective couples should make the marriage last, and they should not divorce unless it is unavoidable. Accordingly, some participants married because they thought they had a good prospective partner for life.

Some participants married because they were advised to do so by their parents in order to ensure that they are “safe” in accordance to Islamic teachings. For example, one man described the decision he and his wife made: “Even parents would push to get married early because children might take a wrong turn or walk on a bad path or something sad might happen.” Another participant thought her mother advised her to get married because according to the Shari’ah, children are not allowed out of wedlock: “They [parents] might have thought that I might take a wrong turn. Lot of girls got pregnant out of wedlock even in those days.”

Personal factors such as limited options on the islands including not having an opportunity to continue education was also a reason for marrying for a few participants in this study. For example, one participant described her decision as follows, “Just that… we cannot continue the education any further in the island. So I wanted to get married and start a life.”

Reasons for not testing

Carrier testing has been freely available in Male’ since 1992. It was also offered on the islands by the mobile teams of SHE from that year onward. However, all participants in this study had at least one β-thal child born after 1992, but without them knowing their carrier status. The participants provided a range of reasons for not testing for thalassemia when the service became available. The main reasons included, poor awareness, insufficient knowledge of the condition, belief that they were not at risk, and testing being not mandatory.

Poor awareness and not knowing about the availability of testing services were described as being main reasons that participants did not undergo testing. For example, one participant reflected, “We were not that aware then… I didn’t know that we can test at that time. I knew SHE was there, but I didn’t know much about carriers.”

Additionally, participants noted that while they had some knowledge about thalassemia, it was insufficient to understand the importance of getting tested. This reasoning was common among those who married before 1992 as well as those who married after 1992. For example, one participant who married before 1992 noted, “I heard about it [thalassemia] a little, but didn’t give much attention.” Similarly, a woman who married after 1992 stated, “I remember hearing about it [thalassemia], but I wasn’t concerned much about it at the time.”

Some participants knew a little more than the above mentioned participants, but did not understand the severity or the possible consequences of the condition. Some said they had β-thal relatives and knew that β-thal children needed continuous transfusions. They did not, however, realize its consequences fully. For example, a couple who had β-thal relatives on both sides of their family described their situation as “[Our] Awareness was not there… If his sister told us that “this is that big” and “it’s good to do the tests”—we would have known.” Another participant added noting, “We knew there is something called thalassemia, but didn’t know that it is this big.” Therefore, poor awareness of possible consequences was also a major factor for many participants in this study not being tested for thalassemia before marriage or having children.

Additionally, the findings show that some participants had a good knowledge of thalassemia as a genetic condition, but they did not do the test because they did not think that they would be carriers and they were confident in that belief. For example, one participant explained her decision not to test, “So I would hear about it [thalassemia]… But I didn’t think that I needed to test… I didn’t think that it would happen to us.” Another woman described her confidence as, “I never thought that I would be one of them [thalassemia carriers].” A man who thought he would not be a carrier described his confidence and stated, “I was so sure that I would not be a carrier because no one else in my family is.”

Furthermore, a few participants stated that they did not undertake premarital testing despite knowing that it was important because it was not mandatory at the time of their marriage. For example, one participant who married after 1992 in Male’ noted, “Now we can’t get married without testing for it [thalassemia]. There were no such regulations in those days.”

When asked if they would get married to the father/mother of the child if they knew their carrier status and the risks involved, most of them replied “No”. Two participants said they might, but in that case they said they would seek alternatives when having children. Another two participants replied that they do not know what their decision would be in that situation.

Realization of the carrier status

Participants in this study realized their carrier status in two ways. While most came to know with their first diagnosed β-thal child, the next most common form of knowing was via ad hoc screening conducted by the mobile teams of SHE for the islands.

Current practice in Maldives is for parents to undertake a carrier test before confirming their child’s diagnosis. Hence, many participants found out their carrier status through the carrier test they undertook as part of the diagnosis of their child. For example, one couple, who had a β-thal child of less than a year stated, “Yes, [we came to know about our status] after she was born. They explained that we need to get tested [as part of diagnosis of the child]. When we received the results, we both turned out to be carriers.”

Those participants who found out their carrier status as a result of ad hoc screening conducted by the mobile teams from SHE became aware of their carrier status before the child’s diagnosis, through undertaking their carrier test while the woman was pregnant with the child, or when the child was a few months old with no symptoms. For example, one participant who was married and pregnant at the time of testing stated, “It’s just that we got the opportunity to do it while we were on the island.... The team came to our island, so we thought we should get tested. When we tested, we both were carriers.”

In addition, a few (four) participants accepted their carrier status based on their doctor’s explanation and their child’s condition, without a carrier test. One of them stated, “No, I haven’t [done the carrier test]. Doctors say that children need (to be) transfused because we both are carriers. There’s no point of testing after that point of time, right?… So we didn’t do the test.”

Life after the diagnosis of β-thal child/children

Our results show that giving birth to a β-thal child had a significant impact on the participants’ lives in many ways. The main influencing aspects included difficulties with treatment for the child, having to migrate, impact on family size, change in knowledge and attitude, hardship related to caring for the child, prejudice felt due to the condition, and divorce as a result of the carriers status.

The treatment process for the β-thal children was distressing for most participants in this study. Treatment for β-thal children in Maldives is blood transfusion and iron chelation. Maldives does not have a suitable blood banking service for the patients who need transfusions. According to the participants, the normal procedure for all β-thal patients was for parents/guardians to find donors and then the service provider would do cross-match and transfusion free of charge. All participants went through that process of finding a donor every other week or so. Some of them described the process as quite “all right”.

However, for some others, accessing blood was difficult. Those participants discussed many difficulties including being unable to secure donors at times, feeling helpless, and the embarrassment of having to ask donors repeatedly. For example, one participant stated, “Most of the times, if they don’t answer the phone, I feel uncomfortable to call again.” Another participant stated, “Once I got very helpless. I left all my dignity and asked people on the road. I approached strangers and asked their blood group and if they can give some blood.” In most cases, participants described the time passed without being able to get a matching donor as worrying and distressing.

Migration as a result of the child’s diagnosis was a common scenario for many participants of this study who were from smaller islands. Many participants moved to larger islands, especially to the capital Male’ to ease the difficulties of accessing transfusion services. One such participant stated that, “We can do the transfusion from the island, but what happens is, it’s difficult to get blood from a crowded place like this [Male’] even. So, we cannot get donors from the island to do transfusion every other week.” However, most of the migrated participants described the life in Male’ as difficult and expensive even though access to services was easier.

Most participants expressed the desire to have a larger family due to cultural and religious reasons. For example, in Maldivian culture, children look after their elderly parents and a participant in our study reflected on this: “Everyone will grow old one day. We will need their [children’s] help and if I have many children, I will get some help.” Another participant expressed her desire to have a larger family because it is recommended in Islam, “I want another child from that [Islamic] aspect as well. It is like that in Islam, right?”

However, even with the desire and need to have a larger family, all participants used some kind of child spacing or contraceptive method after the diagnosis of their first β-thal child. Many started contraception because they were afraid that they might not be able care for the child they already had. For example, one participant stated, “It is more than thalassemia. We will not be able to give attention to this child if we get another child. If we can’t give good care for this girl [β-thal child], I don’t want another child.” Additionally, some participants were afraid of having another β-thal child. For example, one participant stated, “I want another child, but I don’t know what will happen. If I get another β-thal child, it might be an addition to the present child. It will be an additional responsibility. It will be burdensome for us.” Seeing their children pass away due to the condition and witnessing their suffering when undergoing treatment were also reasons for some participants not wanting to have more children. In fact, two couples and 10 individual participants did not have an additional child after their first diagnosed β-thal child.

Diagnosis of their first β-thal child significantly changed the participants’ knowledge of thalassemia and attitude towards marriage between carriers. Following diagnosis, most participants in the study understood the possible consequences of being a carrier couple. And all knew and accepted that they had a β-thal child because both were carriers of thalassemia. They also understood that thalassemia is hereditary, and there was a chance that they might have a β-thal child every time they get pregnant. The collective attitude of the participants towards carriers marrying carriers was, “it is not recommended” and most participants expressed strong discouragement towards it. For example, one participant expressed his opinion as follows:

What I want to say is no matter how much you love someone do not marry a carrier. You can get someone else that you love and the other person can be forgotten, but what you have to face by marrying a carrier can never be forgotten. Never get married! A huge risk like that should not be taken in life…You shouldn’t get into something that hasn’t got any guarantee. I will say, don’t do it!

Hardship of caring for a β-thal child was a common issue discussed by most participants in this study. They expressed that having a β-thal child was hard financially and mentally. Participants described that treatment itself was not costly because thalassemia services were free for registered patients, but indirect costs mostly related to renting and traveling were burdensome for those who were not from Male’. For example, one participant noted, “Rent, food and other things cost about MVR10, 000 [Approximately U$600] to stay here for about 10 days.” That was a large sum of money in her case as she was a self-employed single mother who earns about $300 per month. Additionally, most participants described the emotional hardship that they go through when caring for a β-thal child as being harder than anything else. For example, a man described his emotions as follows:

Actually, I get very worried. I am most saddened about these children. Their hardship and the anguish they will feel in their heart. That part is most distressing. I get very sad because of that. They were very young and cry a lot during transfusion. It was very tormenting. I cannot even explain what went through my heart at times. Those feelings are too difficult to explain. Even now I think about this girl [β-thal daughter] a lot. Sometimes when I am alone, I think about her to the extent that I cry for myself. The sufferings she goes through and how sad she will be, how joyful others of her age are. Things like that come to my mind a lot.

Despite most participants feeling that they did not face any prejudice due to their carrier status, a few (3) expressed concerns about how the society looked at them. For example, one woman described being labeled because of the condition, “Things like ‘the child got sick because I am a bad person. There is a disease in me that I am hiding from doctors’. I got very sad when they [relatives of her husband] talked like that.” Additionally, some participants talked about their children (both β-thal and normal) facing prejudice in the community, albeit not in the school system. For example, one participant noted that, “They [public] look at β-thal children very differently, very different than normal children; especially, in less developed islands.” Also, a few participants felt that their thalassemia carrier children faced discrimination because of their β-thal siblings. One of them noted:

We cannot say it’s [prejudice towards normal siblings] not there in Maldives… It is actually there. Sometimes (pause) for example, I have a normal child, but people restrict girls from talking to him. Like, there are some girls who don’t want to get involved with my son because he has β-thal brothers in the family.

Despite most participants suggesting that divorce was not a solution to their problem and they would rather stay together and assume responsibility together, a few faced the devastating consequence of divorce as a result of being a carrier. One man stated that he went for a divorce because he wanted a normal child and did not want to take the risk of another pregnancy with his carrier wife. A single mother also described the diagnosis of the child and their screening as devastating, and it caused them to separate in the end,

As soon as he came inside [just after the test result], he said “we cannot live together and we should get separated.” From there…Our relationship became very weak from that day onward… we ended up with a divorce after 10 years of marriage.

Coping: a test of faith in Islam

Despite the hardship, worries, separations, and prejudice, all participants still believed that whatever happened, it happened for the best and everything happens according to Allah’s decree. For example, one participant stated, “Having a thalassemia child (pause)… what I would say is what is there in Allah’s decree will happen. That’s how I see it.” Another participant stated that, “Everything happens according to Allah’s Will.” Since most participants’ viewed their circumstance as Allah’s decree, they naturally believed that they should not complain or regret their situation. For example, one participant stated, “I look at it from a religious point of view. I cannot complain about it. We have to accept and be happy with Allah’s decree.”

Additionally, many participants viewed their circumstances as a test of faith from Allah and believed that Allah would not place undue burden on a human being that could not be carried out by that person. For example, one participant described his situation as, “Allah will not burden someone to the extent that it cannot be carried by that person. So, I am being patient in these things and live my life.” Moreover, most participants firmly believed that their β-thal children are a trust from Allah given for safe keeping and it should not be neglected under any circumstance. They believed that responsibility of caring for a β-thal child was a test of patience from Allah, and it should be endured with courage. For example, one man stated that:

We have to work for it as long as she [β-thal child] lives because it is an amaanai (trust given for safe keeping) from Allah, right? I cannot neglect her. I don’t want to abandon that “amaanai” from Allah… There is no way that I will neglect that responsibility. I will not neglect her while my knees touch this ground (mumbles). It’s a difficult responsibility that is being given to us.

Furthermore, some participants believed that they will be rewarded more from Allah for taking care of a β-thal child because Islam says even the simplest of good deeds will be rewarded. For example, one participant stated that, “Islam says that an affliction of a disease will wipe away sins. From what I hear, we will get more rewards and blessings for looking after a child like this than taking care of a normal child.” Hence, despite most participants describing caring for β-thal children as hard and emotionally draining, most of them accepted it as their fate and it should be endured as best as they can.

Discussion

Findings of this research suggest that there are many reasons that individuals and/or couples do not undertake testing for thalassemia before or after marriage in Maldives. One of the main reasons for not doing the carrier test in our study was poor awareness and lack of understanding of the possible consequences of having a β-thal child. This finding is similar to the findings of Ahmed et al. (2002) and Widayanti et al. (2011). The research conducted by Ahmed and her colleagues to study the β thalassemia carrier testing behavior among British Pakistanis shows that there was a low level (61 %) of intention to test among the participants in their study, and participants had poor knowledge about being a carrier and inheritance of the conditions. They concluded that the high prevalence of β-thal births among British Pakistanis was the results of poor knowledge and negative attitude towards carrier testing. The study by Widayanti et al. (2011) was conducted to explore the opinions of Javanese mothers about thalassemia. Their study was based on a sample of 180 Javanese mothers of whom 74 had a β-thal child. Their findings showed that 43 % of their study participants had never heard of thalassemia. However, most of their study participants were keen to get information and carrier testing, implying that lack of awareness played a vital role in the low levels of carrier testing.

Awareness-related findings of this study are in accordance with Health Belief Model (Champion and Skinner 2008). Our findings show that most of our participants did not do the carrier test because they did not have the full knowledge of the condition. Hence, many did not understand their susceptibility to the condition prior to the diagnosis of their first β-thal child, neither the severity of the condition, nor the benefit of testing well in time to take any precaution. Perhaps, changing the approach of health education, screening, and genetic counseling provided by SHE and MBS might improve the use of the services at an earlier stage. That in return might help the Maldivian population understand the condition and its consequences better, and it might help in reproductive decision-making of carrier couples beforehand. In addition, this finding in Maldives suggests that awareness programs are not achieving the targeted outcome from the whole population. At present, the awareness programs are cantered in the capital Male’ and populations in the islands have limited access to those services. Making it more local to the island populations and making the information more freely available to everyone in Maldives (via schools, health centers, hospitals, and clinics) might be helpful in changing the situation for better.

Poor awareness in our study might be due to participants not receiving the many messages that were conveyed by the awareness programs at the time of their marriage. According to Firdous (2005), printed materials on thalassemia were distributed and made available for the public via island health centers from the start of the Thalassemia Awareness Program of SHE in 1992. In addition, the same program included extensive public education and awareness via school health education programs. Furthermore, thalassemia was included in secondary school curriculum and training courses of teachers and health personnel in 1996 as part of advocacy building among national stakeholders (Firdous 2005). Maldives has one of the highest school attendance and literacy rates in South Asia, and even the smallest populated islands have health posts with a family health worker or a community health worker. Therefore, the gap between the awareness level that programs could deliver and the real awareness level of the public needs much attention. Perhaps, it is possible that health promotion activities were well planned but not well delivered throughout the country.

Most participants in our study stated that they would not marry if they knew their carrier status and the risks involved. This view is similar to the findings related to cancellation of marriages by participants after premarital testing in countries like Saudi Arabia (Memish and Saeedi 2011) and Gaza Strip (Tarazi et al. 2007). Memish and Saeedi found that 51.9 % of those who were tested and found to be carriers chose not to proceed with the marriage in their evaluation of outcome of national premarital screening and genetic counseling program in Saudi Arabia. The study undertaken in the Gaza Strip, Palestine by Tarazi et al. (2007) showed that as high as 73.7 % of the carriers in their study did not proceed with the marriage to their carrier partners. Hence, the negative attitude towards carriers marrying carriers among our participants provides a point of intervention for more effective strategies in the thalassemia program.

Timing is an important factor that needs further attention in Maldives. Premarital screening undertaken just prior to marriage like in many other Muslim countries (see for example Saudi Arabia (Memish and Saeedi 2011) might not work in Maldives. Dating and seeing the other person as a compatible life partner was one of the major factors that contributed for most participants’ decision to proceed to marriage in our study. Dating for a long period would make the relationship public on most islands, and it might be difficult for intending couples not to proceed with the marriage even if testing confirms their positive carrier status. Difficulties experienced with canceling wedding plans and stigmatization were also common reasons for proceeding with the marriage in other countries including Saudi Arabia (Al Hamdan et al. 2007; Fahad et al. 2012). Additionally, studies conducted in Southern Iran also showed similar findings: canceling wedding plans once they become public was not an option for many (Karimi et al. 2007). Therefore, the marriage culture of “dating and marrying” suggests that timing of the screening is an important factor that might influence the choice of prospective marriage partners in Maldives. Also, it suggests that there might be space for alternative reproductive health procedures such as prenatal diagnosis in Maldives which is reported by the same authors elsewhere.

A few participants in our study indicated that compulsory premarital testing would have prevented them getting married without testing. They indicated that they knew about thalassemia, but did not do the test because it was not compulsory at the time of their marriage. This finding is similar to the findings of Bozkurt (2007) in Cyprus and screening-related findings in primary health care centers of Oman (Al-Farsi et al. 2014). According to Bozkurt’s study (2007), only 42 % of the participants in Cyprus volunteered for the screening test, while 58 % undertook the screening because it was compulsory. Likewise, Al-Farsi and his colleagues (2014) found that 84.5 % of their study participants in Oman thought that premarital screening was important and 49.5 % participants believed that it should be made compulsory. The new thalassemia law of Maldives mandates every child is screened before 18 years of age. Therefore, the future uptake of screening might be different from the findings of this study.

Not screening for thalassemia before or after marriage had devastating consequences for our study participants. The most difficult and distressing consequence was the emotional trauma that they experienced as a result of the suffering of their child/children. This finding provides qualitative insight into the high prevalence of depression observed among the mothers of thalassemia and blood malignancies children in Iran (Sharghi et al. 2006) and high parental anxiety that was apparent among the parents of β-thal children in Turkey (Canatan et al. 2003). The Iranian study was conducted using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). The mothers of thalassemia children in that study had a BDI score of 17.9 (SD = 10.6) (13.81 (SD = 9.6) for the control group). The study conducted in Turkey by Canatan et al. (2003) reported that 82 % of the parents in their study had high levels of anxiety. Maldives has a large β-thal population, but there are no support services (formal) for parents of β-thal. This finding shows the importance of support service for the mental wellbeing of the parents of β-thal patients.

Thalassemia treatment is free of charge in Maldives; however, many participants, especially those who were from the islands, described indirect costs such as rentals and traveling to access the services were burdensome for them. This phenomenon was observed among the parents of thalassemia patients in other countries as well. For example, a study conducted in Turkey by Canatan et al. (2003) revealed that almost half (47 %) of the families that were included in their study had financial difficulties because of β-thal children and related issues despite the treatment itself being free of charge. This finding reveals the need for government-based extra financial assistance for β-thal patients and their families who were experiencing financial difficulties due to the indirect factors such as travel.

Many participants in our study wanted larger families, but all started some kind of child spacing or contraception after the diagnosis of their first β-thal child in order to prevent further pregnancies. The main reasons were fear that they might be unable to take care of the present β-thal child and the uncertainty around the status of the child from any subsequent pregnancies. Hence, trying to compensate for the genetically affected child was not a common phenomenon among this group of participants. These findings are different to the findings that were observed among the parents of β-thal patients in Fars province, Iran (Habibzadeh et al. 2012). Those showed that, regardless of the number of affected children with thalassemia in a family, parents in that area had a similar average number of unaffected children as parents without the disorder. The difference in our study might be due to the fact that participants were not aware of their carrier status when they started their family and were more concerned about wellbeing of the β-thal child than trying to compensate for the loss. This warrants further research.

Despite the severe consequences of having a β-thal child, no participant regretted giving birth to their β-thal child. Most participants believed their circumstances were, “Allah’s Will”. Additionally, many believed that the β-thal child was a test from Allah and they will be rewarded for caring for them. Furthermore, many believed that their β-thal children were an “amaanai” (trust for safe keeping) from Allah. Similar findings were observed by Shaw and Hurst (2008). Their findings showed that their participants (mainly British Pakistani Muslims) believed the genetic condition that they faced was God’s decision, and most believed their condition or that of their children was a test from God and they should endure it. Findings of the study undertaken by Rozario (2009) also showed that strong faith and being content with Allah’s decision were important for Bangladeshi couples. Hence, faith played an important role in the lives of our study participants and how they dealt with issues related to their carrier status and the birth of their β-thal child/children.

Limitations

While we were able to include participants from 10 atolls, we were unable to access all cases in Maldives. Those who were not included may have had a different experience. This was the main limitation of the study.

Conclusion

Thalassemia is a common genetic disorder across Maldives. The population wide carrier testing program for thalassemia was introduced in 1992, free of charge. The findings of this study revealed that there are many reasons why Maldivians do not undertake premarital testing or testing after marriage. Most common reasons included poor awareness of the availability of the service, poor knowledge about the condition and the consequences of it, and the non-compulsory nature of the test at the time of their marriage. The consequences of giving birth to a β-thal child were challenging and life changing for most participants in this study. Most challenges were related to caring for β-thal child and the concomitant emotional hardship they experienced. Religion appeared to inform every decision at every stage of their life, however, which is considered positive.

It is apparent from our findings that the thalassemia awareness program of Maldives needs to be strengthened. Maldives has a culture of selecting own partners and dating before proceeding to a marriage. Therefore, even if the population receives the awareness messages, cancellation of marriages based on premarital test results might be less effective compared to many other Muslim countries where marriages are mostly arranged. Therefore, in order to improve outcomes, the prevention program needs to incorporate more reproductive options such as prenatal diagnosis and pre-implantation diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants who took part in this study and all the staff of Maldives Blood Services for all the help they provided during this study.

Compliance with ethical standards

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Western Australia (Ref: RA/4/1/5626) in accordance with the requirements of the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (National Statement) and the policies and procedures of The University of Western Australia. In Addition, the study was approved by the National Health Research Committee of Maldives on the seventh of February, 2013. All procedures of this study were carried out in accordance to the laws and regulations of Australia and Maldives. All participants provided written consent prior to study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmed S, Bekker H, Hewison J, Kinsey S. Thalassaemia carrier testing in Pakistani adults: behaviour, knowledge and attitudes. Public Health Genomics. 2002;5:120–127. doi: 10.1159/000065167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Hamdan NA, Al Mazrou YY, Al Swaidi FM, Choudhry AJ. Premarital screening for thalassemia and sickle cell disease in Saudi Arabia. Genet Med. 2007;9:372–377. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318065a9e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Farsi OA, Al-Farsi YM, Gupta I, Ouhtit A, Al-Farsi KS, Al-Adawi S. A study on knowledge, attitude, and practice towards premarital carrier screening among adults attending primary healthcare centers in a region in Oman. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angastiniotis M. The Maldives: WHO Mission August 2014. Nicosia: Thalassaemia International Federation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Birgens H, Ljung R. The thalassaemia syndromes. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2007;67:11–26. doi: 10.1080/00365510601046417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt G. Results from the North Cyprus thalassemia prevention program. Hemoglobin. 2007;31:257–264. doi: 10.1080/03630260701297204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caelli K, Ray L, Mill J. ‘Clear as mud’: toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2003;2:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Canatan D, Ratip S, Kaptan S, Cosan R. Psychosocial burden of beta-thalassaemia major in Antalya, south Turkey. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:815–819. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion LV, Skinner SC (2008) The health belief model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K (eds) Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. Jossey-Base: A Wiley Inprint, San Francisco

- Chiruka S, Darbyshire P. Management of thalassaemia. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;21:353–356. doi: 10.1016/j.paed.2011.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fahad M, Alswaidi ZA, Memish SJ, O’Brien NA, Al-Hamdan FM, Al-Enzy OAA, Al-Wadey AM. At-risk marriages after compulsory premarital testing and counseling for β-thalassemia and sickle cell disease in Saudi Arabia, 2005–2006. J Genet Couns. 2012;21(2):243–255. doi: 10.1007/s10897-011-9395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firdous N. Prevention of thalassaemia and haemoglobinopathies in remote and isolated communities—the Maldives experience. Ann Hum Biol. 2005;32:131–137. doi: 10.1080/03014460500074996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firdous N, Gibbons S, Modell B. Falling prevelance of beta-thalassaemia and eradication of malaria in the Maldives. J Community Genet. 2011;2:173–189. doi: 10.1007/s12687-011-0054-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garewal G, Das R, Jaur J, Marwaha RK, Gupta I. Establishment of prenatal diagnosis for ß-thalassaemia: a step towards its control in a developing country. Ann Hum Biol. 2005;32:138–144. doi: 10.1080/03014460500075019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habibzadeh F, Yadollahie M, Roshanipoor M, Haghshenas M. Reproductive behaviour of mothers of children with beta-thalassaemia major. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18:246–249. doi: 10.26719/2012.18.3.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M, Jamalian N, Yarmohammadi H, Askarnejad A, Afrasiabi A, Hashemi A. Premarital screening for β-thalassaemia in Southern Iran: options for improving the programme. J Med Screen. 2007;14:62–66. doi: 10.1258/096914107781261882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvale S. Doing interviews. London: SAGE Publications, Ltd; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Memish ZA, Saeedi MY. Six-year outcome of the national premarital screening and genetic counseling program for sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31:229–235. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.81527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam SB. Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation. San Francisco: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health . The Maldives health statistics 2013. Maldives: Ministry of Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Legal Reform Information and Arts . Functional translation of the Constitution of the Republic of Maldives 2008. Maldives: President’s office; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics . Maldives: population and housing Cencus 2014. Maldives: Ministry of Finance & Treasory; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Peoples’ Majlis . Thalassaemia prevention law. Maldives: President’s Office; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pijpe J, de Voogt A, van Oven M, Henneman P, van der Gaag KJ, Kayser M, de Knijff P. Indian ocean crossroads: human genetic origin and population structure in the Maldives. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2013;151:58–67. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozario S. Allah is the scientist of the scientists: modern medicine and religious healing among British Bangladeshis. Cult Relig. 2009;10:177–199. doi: 10.1080/14755610903077562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena A, Phadke S. Feasibility of thalassaemia control by extended family screening in Indian context. J Health Popul Nutr. 2002;20:31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharghi A, Karbakhsh M, Nabaei B, Meysamie A, Farrokhi A. Depression in mothers of children with thalassemia or blood malignancies: a study from Iran. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006;2:27. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-2-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A, Hurst J. “What is this genetics, anyway?” understandings of genetics, illness causality and inheritance among British Pakistani users of genetic services. J Genet Couns. 2008;17:373–383. doi: 10.1007/s10897-008-9156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarazi I, Al Najjar E, Lulu N, Sirdah M. Obligatory premarital tests for β-thalassaemia in the Gaza strip: evaluation and recommendations. Int J Lab Hematol. 2007;29:111–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-553X.2006.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund . The state of the world’s children report 2015 statistical tables. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Verma IC, Saxena R, Kohli S. Past, present & future scenario of thalassaemic care & control in India. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134:507–521. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster’s New World Medical Dictionary (2008) Thalassemia major. Credo Reference, Boston http://ezproxy.library.uwa.edu.au. Accessed 15 Nov 2015

- Widayanti CG, Ediati A, Tamam M, Faradz SMH, Sistermans EA, Plass AMC. Feasibility of preconception screening for thalassaemia in Indonesia: exploring the opinion of Javanese mothers. Ethn Health. 2011;16:483–499. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2011.564607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . WHO South East Asia advisory committee on health research: report to the regional director. New Delhi: World Health Organization: Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Social disparities in health in the Maldives: an assessment and implications. India: World Health Organization: Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World health statistics 2015. Luxembourg: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zeinalian M, Nobari R, Moafi A, Salehi M, Hashemzadeh-Chaleshtori M. Two decades of pre-marital screening for beta-thalassemia in central Iran. J Community Genet. 2013;4:517–522. doi: 10.1007/s12687-013-0142-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]