Abstract

1-Naphthaleneacetamide (NAAm) is a synthetic plant growth regulator in the auxin family that is widely used in agriculture to promote the growth of numerous fruits, for root cuttings and as a fruit thinning agent. The potential genotoxic effects of NAAm were investigated in vitro by the chromosome aberrations (CAs), and cytokinesis-block micronucleus assays in human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) for the first time. The human PBLs were treated with 20, 40, 80, and 160 µg/mL of NAAm for 24 and 48 h. The results of this study showed that NAAm significantly induced the formation of structural CA and MN for all concentrations (20, 40, 80 and 160 µg/mL) and treatment periods (24 and 48 h) when compared with the negative and the solvent control. In addition, the higher concentrations of NAAm (80 and 160 µg/mL) caused a statistically significant increase in nuclear bud (NBUD) formation for both 24 and 48 h treatment times. With regard to the cell cycle kinetics, at all the tested concentrations, NAAm caused a statistically significant reduction in the mitotic index (MI) only for 48 h treatment period and also in the nuclear division index (NDI) for both 24 and 48 h treatment periods as compared to the control groups. The reductions in the MI and NDI occured in a concentration-dependent manner for both treatment times. In conclusion, the present results indicate that in the tested experimental conditions, NAAm was genotoxic and cytotoxic on human PBLs in vitro.

Keywords: 1-Naphthaleneacetamide, Synthetic plant growth regulator, Chromosome aberration, Micronucleus, Human peripheral blood lymphocytes

Introduction

1-Naphthaleneacetamide (NAAm) is a synthetic plant growth regulator in the auxin family due to its chemical structure similarities with auxin indole acetic acid (IAA) (Tomlin 2000; USEPA 2007), a natural plant growth hormone which has an important role for seed and root development. NAAm has been widely used in agriculture for several decades as a component in many commercial plant rooting and horticultural formulations such as Rootone, Amide-Thin W, Frufix and Amcotone (Tomlin 2000; USEPA 2007; EFSA 2011). It is used as thinning agent for fruits, particularly apples, pears, peaches and grapes; for root cuttings; and to prevent fruit drop shortly before harvest (Tomlin 2000; Link 2000). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) indicates that approximately 20,000 Ibs (9,000 kg) of naphthalene acetate active ingredients such as NAAm and 1-naphthyl acetic acid are applied annually in the U.S.A. (USEPA 2007). Due to the large amounts of such chemicals are released into the environment, they may represent a potential hazard to the genetic material of the exposed living organisms such as plants, animals and possibly humans. It was also reported that NAAm is degraded by sunlight under environmental conditions, producing primary photoproducts that are more toxic than the parent compound (Da Silva et al. 2013). Regarding to toxicity, NAAm is considered as unlikely hazardous by the World Health Organization (WHO) but as highly toxic by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (Kegley et al. 2011; Esparza et al. 2013). It is also considered harmful to aquatic organisms with a LC50 of 44 mg a.s/L for fishes and harmful if swallowed based on a LD50 of 1,655 mg/kg bw. (EFSA 2011). Unfortunately, to our best knowledge, there is no study available on the genotoxic and/or cytotoxic effects of NAAm on humans in the literature. However, some synthetic auxins, such as 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) (Holland et al. 2002; Cenkci et al. 2010), dicamba (Gonzàlez et al. 2007, 2009; Gonzàlez et al. 2011), and synthetic IAA (Salopek-Sondi et al. 2010) have been found genotoxic, mutagenic and cytotoxic in various test systems. Thus, taking into account these facts, it has become important to evaluate the possible genotoxic potential of NAAm on humans.

Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the genotoxic effects of NAAm using the in vitro chromosome aberration (CA), and cytokinesis-block micronucleus (CBMN) tests, which are worldwide well recognized genotoxicity assays, in human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs), for the first time. In addition to micronucleus assay, the frequency of nuclear buds (NBUDs) in binucleated lymphocytes was analyzed. The mitotic index (MI) and nuclear division index (NDI) were also calculated to evaluate cytotoxic/cytostatic effects of NAAm in human PBLs.

Materials and methods

Test samples and chemicals

Human peripheral blood samples were obtained from four (n = 4) healthy volunteer donors (two males and two females, all non-smokers) aged from 22 to 24 years. All donors had no known excess exposure to genotoxicants. This project was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Mersin University, Turkey and all volunteers gave informed consent to participate in the study and signed consent forms.

NAAm (Fluka 36732, CAS No: 86-86-2; Purity: ≥98.0 %) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The chemical structure of NAAm is shown in Fig. 1. Dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO, purity 99 %, CAS No: 67-68-5), mitomycin-C (MMC, M-05030), colchicine (C-9754) and cytochalasin B (C-6762) were purchased from Sigma. Giemsa and all other chemicals were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). All test solutions were freshly prepared prior to each experiment.

Fig. 1.

The chemical structure and formula of 1-naphthaleneacetamide (NAAm) (C12H11NO; molecular weight: 185.22 g/mol; synonyms: 2-(naphthalen-1-yl)acetamide, 2-(1-naphthyl)acetamide, 1-naphthaleneacetamide, alpha-naphthylacetamide, 1-naphthylacetamide)

Chromosome aberration (CA) assay

The method developed by Evans (1984) was followed in preparation of CA, with minor modifications. This study was performed according to the International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) guidelines (Albertini et al. 2000). Lymphocyte cultures were set up by adding 0.2 mL of whole blood from each of the four healthy donors to 2.5 mL of chromosome medium B (Biochrom F-5023; Berlin, Germany).

The cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 72 h. The concentration range (20, 40, 80 and 160 µg/mL) selected based on the highest concentration that resulted in approximately 50 % (the half maximal effective concentration, EC50) reduction in mitosis (160 µg/mL). Hence, in the present study, the concentrations of the test compound used were 1/8, 1/4, 1/2 of EC50. Serial dilutions of NAAm were made in DMSO under sterile conditions. A negative control (untreated cultures), a solvent control (8 μL/mL DMSO) and a positive control (0.2 μg/mL MMC) were also established, in parallel. Treatment times were conducted as 24 and 48 h. The cells were exposed to 0.06 μg/mL colchicine 2 h before harvesting. To collect the cells, the cultures were centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 5 min. After removal of the supernatant; the pellets were treated with 0.4 % KCl as the hypotonic solution for 15 min at 37 °C and then methanol:glacial acetic acid (3:1 v/v) was added as the fixative for 20 min at room temperature (22 ± 1 °C). The fixative treatments were repeated three times with intermittent centrifugation. Finally, the centrifuged cells were dropped onto cold glass slides and air-dried. The slides were stained following standard methods (5 % Giemsa in Sorensen Buffer, pH 6.8, 15–20 min).

Cytokinesis-block micronucleus (CBMN) assay

The cytokinesis-block MN (CBMN) assay was carried out using the methods of Fenech (2000), and Kirsch-Volders et al. (2003). To establish the cultures, 0.2 mL of heparinized whole blood from four healthy donors was added to 2.5 mL chromosome medium B and incubated at 37 °C for 68 h. The cells were treated with 20, 40, 80 and 160 µg/mL concentrations of NAAm for treatment periods of 24 and 48 h. Cytochalasin B (final concentration of 6 µg/mL) was added to the cultures after 44 h of incubation in order to block cytokinesis. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and the pellets were treated with a hypotonic solution (0.4 % KCl) for 5 min at 37 °C. After centrifugation, the cells were fixed once with a cold fixative (methanol:glacial acetic acid: 0.9 % NaCl, 5:1:6 v/v/v) and then fixed further two times with methanol–glacial acetic acid (5:1 v/v). The MN slides were prepared by dropping and air-drying. Finally, the slides were stained with 5 % Giemsa stain solution for 15 min.

Microscopic evaluation

The CA was classified according to ISCN (International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature) (Paz-y-Miño et al. 2002) and evaluated as the structural (chromatid-type: breaks, exchanges, sister unions; chromosome-type: breaks, dicentrics, rings, fragments, translocations) and the numerical (polyploid cells) aberrations. Gaps were not considered as CA according to Mace et al. (1978). For each donor, 100 well-spread, intact metaphases were investigated (totaly 400 metaphase spreads for four donors) in order to score the CAs at each concentration and treatment period. Percentage of cells with structural CAs, and total CA/cell have been calculated following the scoring of CAs. To determine cytotoxicity, the MI was calculated from the number of metaphases in 3,000 cells (12,000 cells per concentration), analyzed per culture for each treatment and donor in the CA assay. MI was calculated according to the formula: MI = 100 × cells in metaphase/3,000.

In the CBMN assay, MNi and NBUDs were scored in binucleated cells according to the scoring and identification criteria of Fenech et al. (2003) and Fenech (2007). The number of MN and NBUD in 1,000 binuclear cells were analyzed for each donor (4,000 binuclear cells per concentration). Cytostaticity of agent was estimated by using the nuclear division index (NDI). For determining NDI, the number of cells containing 1, 2, 3, or 4 nuclei in 1,000 cells was determined per culture, for each treatment and donor. NDI was calculated using the following formula: NDI = 1 × M1 + 2 × M2 + 3 × M3 + 4 × M4/N; where M1 through M4 represent the number of cells with one to four nuclei and N is the total number of cells scored (Eastmond and Tucker 1989; Fenech 2000).

In this study, slides were examined using an Olympus CX21 light microscope at 1000× magnification.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of experimental values in the CA and CBMN assays was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The comparisons between groups were made using a post hoc analysis, LSD test. Concentration–response relationships were determined from the correlation and regression coefficients for all parameters (CA, MN, NBUD, MI and NDI).

Results

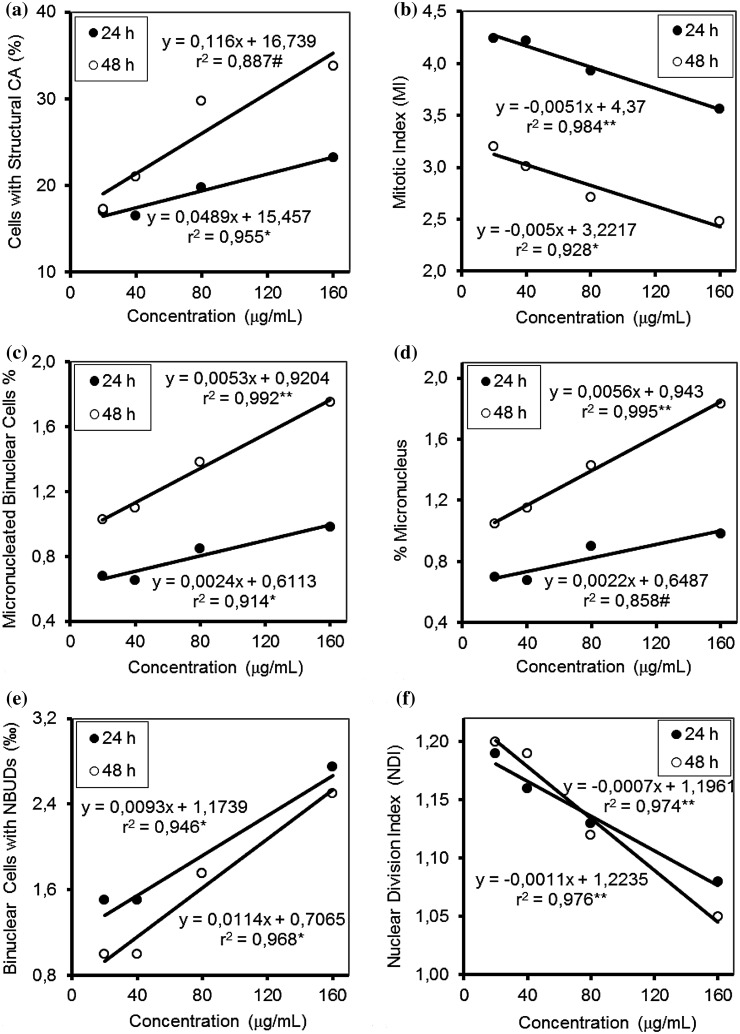

The effects of NAAm on CAs and MI in the human PBLs are summarized in Table 1. NAAm increased the structural CAs significantly for all concentrations (20, 40, 80 and 160 µg/mL) and treatment periods (24 and 48 h) when compared with the negative and the solvent control. The increase of the percentage of structural CAs was concentration-dependent only for the 24 h treatment (for 24 h: r2 = 0.955, P < 0.05; for 48 h: r2 = 0.887, P > 0.05; Fig. 2a). As shown in Table 1, NAAm did not increase CAs to the same extent as the positive control, MMC. Although a concentration-dependent decrease was observed in the MI for both treatment periods (for 24 h: r2 = 0.984, P < 0.01; for 48 h: r2 = 0.928, P < 0.05; Fig. 2b), statistically significant decreases were detected at all the concentrations of NAAm only for 48 h treatment when compared with the negative and the solvent control. In addition, NAAm did not reduce the MI as much as the positive control.

Table 1.

Effects of 1-naphthaleneacetamide (NAAm) on chromosome aberrations (CAs) and mitotic index (MI) in human peripheral lymphocytes

| Test substance | Treatment | Structural CAs | Polyploid cells | % cells with structural CA ± SD | MI ± SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (h) | Conc. (μg/mL) | B′ type | B″ type | ||||

| Negative control | – | – | 33 | 2 | – | 8.50 ± 0.57 | 4.28 ± 0.20 |

| DMSO* | 24 | 8 | 35 | 2 | 1 | 8.75 ± 0.95 | 4.22 ± 0.52 |

| MMC | 24 | 0.2 | 71 | 63 | 6 | 27.50 ± 6.24a3b3 | 2.29 ± 0.17 a3b3 |

| NAAm | 24 | 20 | 71 | 10 | 1 | 17.00 ± 1.41 a3b3c3 | 4.24 ± 0.91 c3 |

| 40 | 57 | 16 | 2 | 16.50 ± 1.29 a3b2c3 | 4.22 ± 1.06 c3 | ||

| 80 | 72 | 12 | 2 | 19.75 ± 2.21 a3b3c2 | 3.93 ± 0.87 c2 | ||

| 160 | 82 | 23 | 1 | 23.25 ± 4.03 a3b3 | 3.56 ± 0.64 c1 | ||

| DMSO* | 48 | 8 | 37 | 4 | – | 9.00 ± 0.81 | 4.55 ± 0.14 |

| MMC | 48 | 0.2 | 180 | 153 | 1 | 54.00 ± 13.83 a3b3 | 2.16 ± 0.10 a3b3 |

| NAAm | 48 | 20 | 69 | 8 | 1 | 17.25 ± 1.70 a1c3 | 3.20 ± 0.18 a3b3c3 |

| 40 | 83 | 15 | – | 21.00 ± 2.82 a2b2c3 | 3.01 ± 0.19 a3b3c3 | ||

| 80 | 126 | 22 | 1 | 29.75 ± 1.25 a3b3c3 | 2.71 ± 0.34 a3b3c2 | ||

| 160 | 135 | 34 | 2 | 33.75 ± 6.13 a3b3c3 | 2.48 ± 0.46 a3b3 | ||

All data are expressed as mean ± SD; n = 4

A total of 400 cells were scored per concentration in the CA assay and 12,000 cells were scored for the MI

B′: chromatid type aberration; B″: chromosome type aberration

DMSO dimethylsulphoxide (solvent control), MMC mitomycin C (positive control)

* Treatment concentration expressed as µL/mL

a: Difference significant from negative control

b: Difference significant from solvent control (DMSO)

c: Difference significant from positive control (MMC)

Subscript 1: statistically significant at the level of P < 0.05

Subscript 2: statistically significant at the level of P < 0.01

Subscript 3: statistically significant at the level of P < 0.001

Fig. 2.

Graphs showing concentration–response curve slopes and correlation coefficients (r 2) of % cells with structural CA (a), MI (b), micronucleated binuclear cells (%) (c), % micronucleus (d), binuclear cells with NBUDs (e), and NDI (f) on human lymphocytes treated with NAAm for 24 and 48 h. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; # P > 0.05

The results of the present study indicate that NAAm induced a statistically significant increase in the percentage of micronucleated binuclear cells (MNBN %) and the percentage of micronucleus (MN %) when compared with the negative and the solvent control at all the concentrations tested (20–160 µg/mL) for both treatment periods (24 and 48 h). However, the positive control, MMC, significantly induced the formation of MN in comparison with all concentrations of NAAm. While the MNBN % increased linearly as NAAm concentration increased for both 24 h (r2 = 0.914, P < 0.05) and 48 h (r2 = 0.992, P < 0.01; Fig. 2c) treatment times, MN % increase was in a concentration-dependent manner only for the 48 h treatment time (r2 = 0.858, P > 0.05 and r2 = 0.995, P < 0.01 for 24 and 48 h, respectively; Fig. 2d). In both 24 and 48 h treated cultures, NAAm statistically significantly increased the binuclear cells with NBUDs (‰) when compared with the only negative control at 80 µg/mL, and compared to the negative and the solvent control at 160 µg/mL concentration. The frequency of NBUDs increased with increasing concentrations of NAAm (r2 = 0.946, P < 0.05 and r2 = 0.968, P < 0.05 for 24 and 48 h, respectively; Fig. 2e).

As shown in Table 2 NAAm caused a statistically significant reduction in the NDI as compared to the control groups (negative and solvent control) at all the concentrations tested and both treatment times. These reductions were concentration-dependent for both 24 h (r2 = 0.974, P < 0.01) and 48 h (r2 = 0.976, P < 0.01) treatments (Fig. 2f). NAAm also decreased the NDI to the same extent as the positive control for the 24 h (40, 80 and 160 µg/mL) and 48 h (80 µg/mL) treatment period. Furthermore, NAAm showed a higher cytostatic effect than MMC at the highest concentration (160 µg/mL) for the 48 h treatment period (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of 1-naphthaleneacetamide (NAAm) on micronucleus (MN), nuclear buds (NBUDs) and Nuclear Division Index (NDI) in human peripheral lymphocytes

| Test substance | Treatment | Distribution of binuclear cells according to no. micronuclei | Micronucleated binuclear cells | Binuclear cells with NBUDs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (h) | Conc. (μg/mL) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | (%) ± SD | MN (%) ± SD | (‰) ± SD | NDI ± SD | |

| Negative Control | – | – | 3,987 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0.33 ± 0.09 | 0.33 ± 0.09 | 0.25 ± 0.50 | 1.28 ± 0.05 |

| DMSO* | 24 | 8 | 3,986 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 0.35 ± 0.05 | 0.38 ± 0.09 | 0.75 ± 0.50 | 1.24 ± 0.01 |

| MMC | 24 | 0.2 | 3,940 | 58 | 2 | 0 | 1.50 ± 0.25 a3b3 | 1.55 ± 0.26 a3b3 | 2.25 ± 1.50 a2b1 | 1.13 ± 0.01 a3b3 |

| NAAm | 24 | 20 | 3,973 | 26 | 1 | 0 | 0.68 ± 0.17 a1b1c3 | 0.70 ± 0.21 a1b1c3 | 1.50 ± 1.29 | 1.19 ± 0.02 a3b1c1 |

| 40 | 3,974 | 25 | 1 | 0 | 0.65 ± 0.17 a1b1c3 | 0.68 ± 0.17 a1b1c3 | 1.50 ± 0.57 | 1.16 ± 0.03 a3b3 | ||

| 80 | 3,966 | 32 | 2 | 0 | 0.85 ± 0.17 a3b3c3 | 0.90 ± 0.21 a3b3c3 | 1.75 ± 0.95 a1 | 1.13 ± 0.02 a3b3 | ||

| 160 | 3,961 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 0.98 ± 0.22 a3b3c3 | 0.98 ± 0.22 a3b3c3 | 2.75 ± 0.50 a3b2 | 1.08 ± 0.01 a3b3 | ||

| DMSO* | 48 | 8 | 3,985 | 14 | 1 | 0 | 0.38 ± 0.15 | 0.40 ± 0.18 | 0.50 ± 0.57 | 1.28 ± 0.05 |

| MMC | 48 | 0.2 | 3,788 | 198 | 11 | 3 | 5.30 ± 0.67 a3b3 | 5.73 ± 0.61 a3b3 | 4.25 ± 0.50 a3b3 | 1.11 ± 0.02 a3b3 |

| NAAm | 48 | 20 | 3,959 | 40 | 1 | 0 | 1.03 ± 0.26 a2b2c3 | 1.05 ± 0.30 a2b2c3 | 1.00 ± 1.41 c3 | 1.20 ± 0.04 a1b1c1 |

| 40 | 3,956 | 42 | 2 | 0 | 1.10 ± 0.14 a2b2c3 | 1.15 ± 0.17 a3b2c3 | 1.00 ± 1.41 c3 | 1.19 ± 0.04 a2b2c1 | ||

| 80 | 3,945 | 53 | 2 | 0 | 1.38 ± 0.09 a3b3c3 | 1.43 ± 0.12 a3b3c3 | 1.75 ± 0.50 a1c3 | 1.12 ± 0.03 a3b3 | ||

| 160# | 3,144 | 53 | 3 | 0 | 1.75 ± 0.23 a3b3c3 | 1.83 ± 0.27 a3b3c3 | 2.50 ± 0.57 a2b2c2 | 1.05 ± 0.03 a3b3c1 | ||

All data are expressed as mean ± SD; n = 4

A total of 4,000 cells were scored per concentration for the MN and other nuclear anomalies in binuclear cells

DMSO dimethylsulphoxide (solvent control), MMC mitomycin C (positive control)

#Due to excessive toxicity a total of 3,200 cells were scored per concentration for the percent micronucleated binuclear cells and MN

* Treatment concentration expressed as µL/mL

a: Difference significant from negative control

b: Difference significant from solvent control (DMSO)

c: Difference significant from positive control (MMC)

Subscript 1: statistically significant at the level of P < 0.05

Subscript 2: statistically significant at the level of P < 0.01

Subscript 3: statistically significant at the level of P < 0.001

Discussion

In this study, the genotoxic and cytotoxic effects of NAAm, a synthetic plant growth regulator, were evaluated. For this aim, the formation of CA, MN, NBUD, and the frequency of MI and NDI in human PBLs were employed as biomarkers of genotoxicity and cytotoxicity, respectively.

Results obtained from this study revealed that, in general, NAAm significantly increased the percentage of cells with structural CA and MN formation at all concentrations (20, 40, 80 and 160 µg/mL) and treatment periods (24 and 48 h) when compared with the control groups. NAAm was also found to significantly induce NBUD formation at the two high concentrations (80 and 160 µg/mL) for both 24 and 48 h treatment times in a concentration-dependent manner.

As already mentioned, there is no published study on the genotoxic and/or cytotoxic effects of NAAm in the literature. Thus, the results obtained from this study present the first data for geno-/cytotoxic potential of NAAm on humans. However, the genotoxic potential of some other synthetic auxins, such as 2,4-D and dicamba, have been shown in many previous studies.

Similarly to our findings, Korte and Jalal (1982) reported that 2,4-D had induced chromosomal aberrations in human PBLs in vitro with concentrations of 50 and 60 µg/mL. Madrigal-Bujaidar (2001) observed that 2,4-D had a moderate genotoxic effect in mice that were treated in vivo with high concentrations (100 and 200 mg/kg) of this compound. Holland et al. (2002) reported that both pure and commercial forms of 2,4-D increased the number of MNi at the highest non-toxic concentration (0.3 mM) in human whole blood and isolated lymphocyte cultures. Ateeq et al. (2002) reported that 2,4-D induced chromosome aberrations (CAs) at statistically significant level in the meristematic mitotic cells of Allium cepa. Filkowski et al. (2003) found that 2,4-D and dicamba induced point mutations and double strand breaks in Arabidopsis and single strand breaks in bean root nuclei. Similar results were also reported by Zeljezic and Garaj-Vrhovac (2004), who observed that deberhan A, a commercial formulation of 2,4-D, caused an increase in chromatid and chromosome breaks, number of MNi and number of NBUDs in human PBLs. Gonzàlez et al. (2011) found that dicamba and one of its commercial formulation banvel induced a significant increase in MN and NBUD formation at a concentration range of 50–500 µg/mL in Chinese hamster ovary cells. The damaging activity of dicamba in different mammalian cell targets was also previously observed by the same research group (Gonzàlez et al. 2006, 2007, 2009). The results of these studies and some others (Amer and Aly 2001; Cenkci et al. 2010) are in agreement with the results of our study, although different cell types and/or test system were used.

The significant increase in the CAs, MNi, and NBUDs following exposure of NAAm in the present study supports the genotoxic potential of this compound. The results of the CA assay showed that NAAm induced the more structural CAs (especially chromatid breaks and acentric fragments) than the numerical CAs. Hence, it can be suggested that NAAm has a clastogenic effect and can lead to the formation of structural CA by breaking the phosphodiester backbone of DNA (Kocaman et al. 2011). DNA damage may be result of direct impact of NAAm on DNA or its indirect effect, for example by production of free radicals. Bukowska (2006) in his review reported that 2,4-D interacted with the genetic material indirectly by producing reactive oxygen species (ROS). 2,4-D is structurally and functionally analogous to the natural auxin IAA (Song 2014), like NAAm. It was also reported that 2,4-D induced proliferation of peroxisomes and increased the intracellular production of DNA-damaging hydrogen peroxide and other reactive oxygen radicals (Kawashima et al. 1984; Linnainmaa 1984; Reddy and Rao 1989) expressing high clastogenic activity (Wolff 1982; Reddy and Rao 1989). We suppose that NAAm may act on nucleic acid, proteins and also lipids with the production of ROS that may cause DNA strand breaks.

MN can be formed from acentric chromosome/chromatid fragments or whole chromosomes that fail to be segregated to the daughter nuclei during mitotic cellular division, and appears as small additional nucleus in the cytoplasm of interphase cells (Fenech and Bonassi 2011; Fenech et al. 2011). Some micronuclei may also be derived from broken anaphase bridges (Lindberg et al. 2007). In the present study, NBUDs, MN-like bodies attached to the nucleus by a thin nucleoplasmic connection, have also been evaluated because they represent a different genomic instability. NBUDs may be formed by exclusion of amplified DNA (Lindberg et al. 2007), from remnants of broken anaphase bridges (Gisselsson et al. 2000, 2001) or by retraction of micronuclei (Lindberg et al. 2007). Although there are no published data relevant to MN and NBUD formations induced by NAAm, it can be seen from the above mentioned literature that some synthetic auxins caused an increase in MN and NBUD frequency in vitro in human PBLs (Zeljezic and Garaj-Vrhovac 2004) and in Chinese hamster ovary cells (Gonzàlez et al. 2011).

Mladinic et al. (2009) suggested that the development of NBUDs is not possible in the short-term cultivation period. In the present study since the CBMN assay was conducted in short-term (68 h) lymphocyte cultures, gene amplification theory cannot be used to explain the formation of NBUDs. Thus, we may suggest that the origin of NBUDs observed in this study could be explained by the broken anaphase bridges and/or the mechanism of micronuclei retraction.

In the present study, the MI and NDI ratios were evaluated for determining cytotoxicity. The measurement of NDI also provides important data on the cytostatic effect of chemicals (Fenech 2007). The results revealed that all the NAAm concentrations tested significantly decreased MI for 48 h, and also NDI for both 24 and 48 h treatment periods as compared to those found in the control group. The reductions of MI and NDI were also observed in a concentration-dependent manner for both treatment times. These data would be indicative of the cytotoxic and cytostatic effects of NAAm in human PBLs. Rixe and Fojo (2007) reported that cytostaticity may be defined as the inhibition of cell growth and/or proliferation, and this initial event can induce cell death if cytostasis is prolonged. Accordingly, in the present study, NAAm revealed a cytostatic effect for the 24 h exposure period without cytotoxicity, whereas this compound displayed both cytostatic and cytotoxic properties for 48 h treatment period due to prolonged exposure of the test substance on lymphocytes.

As similar to the our results, the cytotoxic/cytostatic effects of some different synthetic auxins were reported in the previous studies performed on various test systems (Di Paolo et al. 2001; Tuschl and Schwab 2003; Mičić et al. 2004; Gonzàlez et al. 2006, 2007, 2011).

The mechanism of auxin cytotoxicity is believed to be connected with the production of ROS (Salopek-Sondi et al. 2010). Furthermore, Müller and Sofuni (2000) reported that the clastogenic response of various compounds is often associated with high toxicity. In this study, NAAm most probably had cytostatic and also cytotoxic effects on cultured human PBLs by increasing the oxidative stress and thereby leading to formation of CA resulting in inhibition of DNA synthesis, cell proliferation (i.e. cytostaticity; without lethality) and eventually cell death (i.e. cytotoxicity; with apoptosis).

Conclusion

In conclusion, these findings suggest that NAAm most probably has a genotoxic effect by inducing the CAs, MNi, and NBUDs formation and has a cytotoxic/cytostatic effect by reducing the MI and NDI at the concentrations tested (20, 40, 80 and 160 µg/mL) in human PBLs in vitro. Hence, we can say that this synthetic plant growth regulator may pose clastogenic and cytotoxic/cytostatic risk in human beings and it should be used more carefully. We also suggest that further researches should be done to investigate the possible harmful effects of NAAm on human health.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Mustafa Kemal University Research Fund (project code: 281).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Albertini RJ, Anderson D, Douglas GR, Hagmar L, Hemminki K, Merlo F, Natarajan AT, Norppa H, Shuker DEG, Tice R, Waters MD, Aitio A. IPCS guidelines for the monitoring of genotoxic effects of carcinogens in humans. Mutat Res. 2000;463:111–172. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5742(00)00049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amer SM, Aly FAE. Genotoxic effect of 2,4-dichlorophenoxy acetic acid and its metabolite 2,4-dichlorophenol in mouse. Mutat Res. 2001;494:1–12. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5718(01)00146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ateeq B, Farah MA, Ali MN, Ahmad W. Clastogenicity of pentachlorophenol, 2,4-D and butachlor evaluated by Allium root tip test. Mutat Res. 2002;514:105–113. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5718(01)00327-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowska B. Toxicity of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid-molecular mechanisms. Pol J Environ Stud. 2006;15:365–374. [Google Scholar]

- Cenkci S, Yıldız M, Ciğerci İH, Bozdağ A, Terzi H, Terzi ESA. Evaluation of 2,4-D and Dicamba genotoxicity in bean seedlings using comet and RAPD assays. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2010;73:1558–1564. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2010.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva ES, Wong-Wah-Chung P, Burrows HD, Sarakha M. Photochemical degradation of the plant growth regulator 2-(1-naphthyl) acetamide in aqueous solution upon UV irradiation. Photochem Photobiol. 2013;89:560–570. doi: 10.1111/php.12050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo O, de Duffard AM, Duffard R. In vivo and in vitro binding of by 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid to a rat liver mitochondrial protein. Chem Biol Interact. 2001;137:229–241. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2797(01)00255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond DA, Tucker JD. Identification of aneuploidy-inducing agents using cytokinesis-blocked human lymphocytes and an anti-kinetochore antibody. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1989;13:34–43. doi: 10.1002/em.2850130104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) Conclusion of the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance 2-(1-naphthyl) acetamide (notified as 1-napthylacetamide) EFSA J. 2011;9:2020. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esparza X, Moyanoa E, Cosialls JR, Galceran MT. Determination of naphthalene-derived compounds in apples by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chim Acta. 2013;782:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2013.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans HJ. Human peripheral blood lymphocytes for the analysis of chromosome aberrations in mutagen tests. In: Kilbey BJ, Legator M, Nichols W, Ramel C, editors. Handbook of mutagenicity test procedures. 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers BV; 1984. pp. 405–427. [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M. The in vitro micronucleus technique. Mutat Res. 2000;455:81–95. doi: 10.1016/S0027-5107(00)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M. Cytokinesis-block micronucleus cytome assay. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1084–1104. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M, Bonassi S. The effect of age, gender, diet and lifestyle on DNA damage measured using micronucleus frequency in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Mutagenesis. 2011;26:43–49. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geq050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M, Chang WP, Kirsch-Volders M, Holland N, Bonassi S, Zeiger E. HUMN project: detailed description of the scoring criteria fort he cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay using isolated human lymphocytes cultures. Mutat Res. 2003;534:65–75. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5718(02)00249-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenech M, Kirsch-Volders M, Natarajan AT, Surralles J, Crott JW, Parry J, Norppa H, Eastmond DA, Tucker JD, Thomas P. Molecular mechanisms of micronucleus, nucleoplasmic bridge and nuclear bud formation in mammalian and human cells. Mutagenesis. 2011;26:125–132. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geq052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filkowski J, Besplug J, Burke P, Kovalchuk I, Kovalchuk O. Genotoxicity of 2,4-D and dicamba revealed by transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana plants harboring recombination and point mutation markers. Mutat Res. 2003;542:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisselson D, Björk J, Höglund M, Mertens F, Dal Cin P, Åkerman M, Mandahl N. Abnormal nuclear shape in solid tumors reflects mitotic instability. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:199–206. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63958-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisselsson D, Pettersson L, Höglund M, Heidenbland M, Gorunova L, Wiegant J, Mertens F, Dal Cin P, Mitelman F, Mandahl N (2000) Chromosomal breakage-fusion-bridge events cause genetic intratumor heterogenecity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:5357–5362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gonzàlez NV, Soloneski SE, Larramendy ML. Genotoxicity analysis of the phenoxy herbicide dicamba in mammalian cells in vitro. Toxicol In Vitro. 2006;20:1481–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzàlez NV, Soloneski S, Larramendy ML. The chlorophenoxy herbicide dicamba and its commercial formulation banvel® induce genotoxicity and cytotoxicity in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. Mutat Res. 2007;634:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzàlez NV, Soloneski S, Larramendy ML. Dicamba-induced genotoxicity in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells is prevented by vitamin E. J Hazard Mater. 2009;163:337–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.06.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzàlez NV, Nikoloff N, Soloneski S, Larramendy ML. A combination of the cytokinesis-block micronucleus cytome assay and centromeric identification for evaluation of the genotoxicity of dicamba. Toxicol Lett. 2011;207:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland NT, Duramad P, Rothman N, Figgs LW, Blair A, Hubbard A, Smith MT. Micronucleus frequency and proliferation in human lymphocytes after exposure to herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid in vitro and in vivo. Mutat Res. 2002;521:165–178. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5718(02)00237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima Y, Katoh H, Nakajima S, Kozuka H, Uchiyama A. Effects of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid on peroxisomal enzymes in rat liver. Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;33:241–245. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90481-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegley SE, Hill BR, Orme S, Choi AH (2011) PAN Pesticide Database, Pesticide Action Network, North America, San Francisco, CA. http://www.pesticideinfo.org

- Kirsch-Volders M, Sofuni T, Aardema M, Albertini S, Eastmond D, Fenech M, Ishidate M, Jr, Kirchner S, Lorge E, Morita T, Norppa H, Surrallés J, Vanhauwaert A, Wakata A. Report from the in vitro micronucleus assay working group. Mutat Res. 2003;540:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocaman AY, Rencüzoğulları E, Topaktaş M, İstifli ES, Büyükleyla M. The effects of 4-thujanol on chromosome aberrations, sister chromatid exchanges, and micronucleus in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Cytotechnology. 2011;63:493–502. doi: 10.1007/s10616-011-9372-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte C, Jalal SM. 2,4-D induced clastogenicity and elevated rates of sister chromatid exchanges in cultured human lymphocytes. J Hered. 1982;73:224–226. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a109622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg HK, Wang X, Järventaus H, Falck GC-M, Norppa H, Fenech M. Origin of nuclear buds and micronuclei in normal and folate-deprived human lymphocytes. Mutat Res. 2007;617:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link H. Significance of flower and fruit thinning on fruit quality. Planth Growth Reg. 2000;31:17–26. doi: 10.1023/A:1006334110068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linnainmaa K. Induction of sister chromatid exchanges by the peroxisome proliferators 2,4-D, MCPA, and clofibrate in vivo and in vitro. Carcinogenesis. 1984;5:703–707. doi: 10.1093/carcin/5.6.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace ML, Jr, Daskal Y, Wray W. Scanning-electron microscopy of chromosome aberrations. Mutat Res. 1978;52:199–206. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(78)90141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrigal-Bujaidar E, Hernàndez-Ceruelos A, Chamorro G. Induction of sister chromatid exchanges by 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid in somatic and germ cells of mice exposed in vivo. Food Chem Toxicol. 2001;39:941–946. doi: 10.1016/S0278-6915(01)00037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mičić M, Bihari N, Mlinarič-Raščan I. Influence of herbicide, 2,4-dichlorophenoxy acetic acid, on haemocyte DNA of in vivo treated mussel. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2004;311:157–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2004.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mladinic M, Perkovic P, Zeljezic D. Characterization of chromatin instabilities induced by glyphosate, terbuthylazine and carbofuran using cytome FISH assay. Toxicol Lett. 2009;189:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller L, Sofuni T. Appropriate levels of cytotoxicity for genotoxicity tests using mammalian cells in vitro. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2000;35:202–205. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2280(2000)35:3<202::AID-EM7>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz-y-Miño C, Bustamante G, Sánchez ME, Leone PE. Cytogenetic monitoring in a population occupationally exposed to pesticides in Ecuador. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110:1077–1080. doi: 10.1289/ehp.021101077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy JK, Rao MS. Oxidative DNA damage caused by persistent peroxisome proliferation: its role in hepatocarcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 1989;214:63–68. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(89)90198-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rixe O, Fojo T. Is cell death a critical end point for anticancer therapies or is cytostasis sufficient? Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:7280–7287. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salopek-Sondi B, Piljac-Žegarac J, Magnus V, Kopjar N. Free radical–scavenging activity and DNA damaging potential of auxins IAA and 2-methyl-IAA evaluated in human neutrophils by the alkaline comet assay. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2010;24:165–173. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. Insight into the mode of action of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) as an herbicide. J Integr Plant Biol. 2014;56:106–113. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlin CDS. The pesticide manual. 12. Farnham: British Crop Protection Council Publisher; 2000. p. 661. [Google Scholar]

- Tuschl H, Schwab C. Cytotoxic effects of the herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid in HepG2 cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2003;41:385–393. doi: 10.1016/S0278-6915(02)00238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USEPA (Environmental Protection Agency from United States of America) (2007) 738-R-07-07017 (October 2007) Registration eligibility decision (RED) for Naphthaleneacetic acid, its salts, ester and acetamide. EPA, USA

- Wolff S. Chromosome aberrations, sister chromatid exchanges, and the lesions that produce them. In: Wolf S, editor. Sister chromatid exchange. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 1982. pp. 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zeljezic D, Garaj-Vrhovac V. Chromosomal aberrations, micronuclei and nuclear buds induced in human lymphocytes by 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid pesticide formulation. Toxicology. 2004;200:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]