Abstract

Purpose:

Stagnant outcomes for adolescents and young adults (AYAs; 15 to 39 years old) with cancer are partly attributed to poor enrollment onto clinical trials. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP) was developed to improve clinical trial participation in the community setting, where AYAs are most often treated. Further, many CCOP sites had pediatric and medical oncologists with collaborative potential for AYA recruitment and care. For these reasons, we hypothesized that CCOP sites enrolled proportionately more AYAs than non-CCOP sites onto Children’s Oncology Group (COG) trials.

Methods:

For the 10-year period 2004 through 2013, the NCI Division of Cancer Prevention database was queried to evaluate enrollments into relevant COG studies. The proportional enrollment of AYAs at CCOP and non-CCOP sites was compared and the change in AYA enrollment patterns assessed. All sites were COG member institutions.

Results:

Although CCOP sites enrolled a higher proportion of patients in cancer control studies than non-CCOP sites (3.5% v 1.8%; P < .001), they enrolled a lower proportion of AYAs (24.1% v 28.2%, respectively; P < .001). Proportional AYA enrollment at CCOP sites decreased during the intervals 2004 through 2008 and 2009 through 2013 (26.7% v 21.7%; P < .001).

Conclusion:

Despite oncology practice settings that might be expected to achieve otherwise, CCOP sites did not enroll a larger proportion of AYAs in clinical trials than traditional COG institutions. Our findings suggest that the CCOP (now the NCI Community Oncology Research Program) can be leveraged for developing targeted interventions for overcoming AYA enrollment barriers.

INTRODUCTION

More than 70,000 adolescents and young adults (AYAs; 15 to 39 years) are diagnosed with cancer annually in the United States.1,2 Unfortunately, over the past 30 years, improvement in survival for AYAs has lagged significantly behind that of both younger and older populations.3-7 Although the explanation for this is likely multifactorial, the historically low level of participation by AYAs in US National Cancer Institute (NCI)–funded clinical trials is thought to be crucial.4,8-14 Both the US NCI and the Institute of Medicine have identified improving enrollment of AYAs into cancer trials as a research priority.1,13 Achieving this requires addressing key previously identified enrollment barriers, including the fact that AYAs are more often treated in communities than in traditional academic centers.15-18

The NCI Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP) was launched in 1983 as a strategic initiative to increase access to NCI-funded trials in the community setting and populations characterized by health disparities.19-21 Through 5-year competitive renewal grants, institutions were funded to conduct most types of NCI trials, with an emphasis on cancer prevention and control research. With approximately one-third of all NCI trial participants being enrolled at these institutions, the CCOP demonstrated proof of principle that its approach was effective in improving clinical trial access and enrollment in the community setting.19,20,22-28 In 2014, the CCOP was transformed into the NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) to increase its impact as a component of the new NCI National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN).29,30 The goals of the NCORP are aligned with those of its CCOP predecessor and now include a commitment to conducting research to enhance cancer care delivery and outcomes.

In addition to their emphasis on community-based access, the research teams at 19 of 63 CCOP sites (30.2%) included both pediatric and medical oncology investigators with potential to collaborate in clinical practice and trial recruitment. Further, beginning in approximately 2000, the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) expanded age eligibility where appropriate to provide more clinical trial options for AYAs. This combination of factors could be expected to have facilitated enrollment of AYAs served by CCOP sites with COG institutional membership.

Therefore, we undertook an analysis of all enrollments to COG trials in the period 2004 through 2013 and compared the proportional enrollment of AYAs from COG-affiliated CCOP versus non-CCOP sites. We hypothesized that proportional enrollment of AYAs was higher from the CCOPs than from the non-CCOPs. We reasoned that, if true, the CCOP (now NCORP) approach and infrastructure could serve as a model to be further enhanced, expanded, or disseminated to improve AYA participation. If not, the NCORP would represent an opportunity for leveraging a proven effective program with a targeted enrollment strategy for AYAs.

METHODS

Data Collection and Inclusion Criteria

The NCI Division of Cancer Prevention database was queried to obtain the patient age and institutional type (CCOP or non-CCOP) for all enrollments into COG therapeutic and nontherapeutic studies whose eligibility requirements encompassed age 15 years and older and that were open to enrollment during any portion of 2004 through 2013. An enrollment was classified as AYA if the patient’s age was 15 through 39 years at time of study entry. For purposes of this analysis, therapeutic trials were defined as interventional studies that could be either cancer directed and focused primarily on survival end points, or supportive care directed and linked to nonsurvival outcomes, such as infection, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, and treatment adherence. Disease-specific trials for either newly diagnosed or relapsed/refractory malignancies relevant to the AYA population were included; those for cancers of infancy and young childhood, including infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) hepatoblastoma, neuroblastoma, and Wilms tumor were excluded. Nontherapeutic studies comprised those focused on disease biology, disease classification, epidemiology, and health-related outcomes such as quality of life or caregiver burden. Cancer control studies constituted therapeutic or nontherapeutic studies that had received cancer control designation by NCI. Studies were included in the analysis only if they were routinely conducted at both non-CCOP and CCOP sites, thus phase I trials were excluded.

Statistical Analysis

A well-known limitation of most studies of AYA enrollment onto clinical trials is the lack of a reliable denominator to use for calculating accrual proportion, defined as the proportion of newly diagnosed AYAs among all patients with cancer enrolled onto a clinical trial.13 Although NCI clinical trial registrations have been used in conjunction with SEER incidence data to generate estimates of AYA accrual proportion, this approach was not suitable for our analysis because of the lack of case linkage and geographic variability of CCOP sites relative to SEER population estimates. Therefore, because we had access to accurate data for both age at enrollment (to compute the numerator, the number of AYA enrollments) and the total number of enrollments (to serve as the denominator) by type of site, we calculated AYA proportional enrollments in COG trials (number of AYA patients enrolled divided by total enrollment). Similarly, proportional enrollment onto COG cancer control trials was determined by dividing the number of cancer control study enrollments at CCOP and non-CCOP sites by the total number of study enrollments at each site. Fischer’s exact test and χ2 test of proportions were used to evaluate the difference in proportional AYA enrollment between CCOP and non-CCOP sites, as well as the difference in proportional AYA enrollment at CCOP sites between the intervals 2004 through 2008 and 2009 through 2013.

RESULTS

Overall AYA Clinical Trial Enrollment Onto COG Studies

We first sought to describe the overall availability of and enrollment onto COG trials relevant to AYAs during our study period. Between the intervals 2004 through 2008 and 2009 through 2013, the overall proportion of all COG studies that enrolled at least one patient age 15 years or older increased (77.6% [125/161] v 83.9% [104/124]; P = .25), consistent with the COG’s stated efforts to raise the eligibility age limit on appropriate trials. During this time, there were a total of 64,731 study enrollments in COG trials inclusive of AYAs. However, the proportion of AYA enrollments in these COG studies decreased significantly during this time (28.9% [9,033/31,271] v 26.7% [8,930/33,460]; P < .001). Consistent with the overall decline in proportional AYA enrollment onto COG studies, the proportion of AYA enrollments in therapeutic trials also decreased (33.5% [3,775/11,282] v 30.7% [3,576/11,666]; P < .001).

AYA Clinical Trial Enrollment at CCOP and Non-CCOP Sites

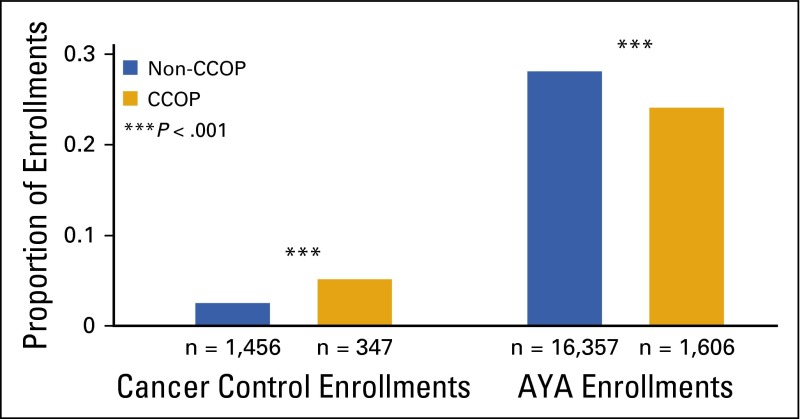

In light of the primary CCOP objective of increasing enrollment onto cancer control studies, we compared cancer control study enrollment between CCOPs and non-CCOPs. During the years 2004 through 2013, there were 9,821 and 81,164 total patient enrollments at CCOP and non-CCOP sites, respectively. As expected, CCOP sites enrolled a significantly higher proportion of patients in COG cancer control studies than did non-CCOP sites (3.5% [347/9,821] v 1.8% [1,456/81,164]; P < .001; Fig 1). In contrast, the proportion of AYA enrollments in all COG studies was significantly lower from CCOP than from non-CCOP sites (24.1% [1,606/6,672] v 28.2% [16,357/58,059], respectively; P < .001).

FIG 1.

Proportion of Children’s Oncology Group (COG) study enrollments categorized as cancer control or AYA, by institution type (2004 through 2013). Whereas proportional enrollment onto COG cancer control studies was significantly greater at CCOP than non-CCOP sites, the proportional enrollment of AYA patients was significantly lower (see Methods for calculation of cancer control and AYA proportional enrollments). The P value represents the difference in proportional cancer control or AYA enrollment between sites. AYA, adolescent and young adult; CCOP, Community Clinical Oncology Program.

Change in AYA Clinical Trial Enrollment at CCOP and Non-CCOP Sites Over Time

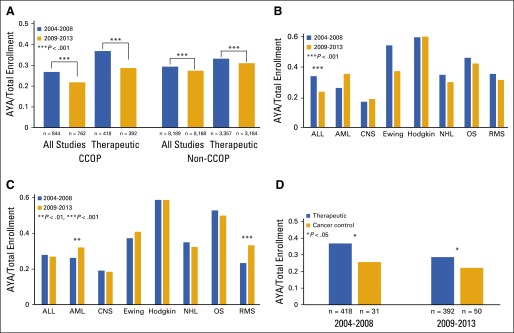

To determine whether proportional enrollment of AYAs in all COG studies at CCOP sites changed over time, the 5-year intervals 2004 through 2008 and 2009 through 2013 were compared. Proportional AYA enrollment at CCOP sites significantly decreased between these intervals (26.7% [844/3,156] v 21.7% [762/3,516]; P < .001), particularly on therapeutic studies (36.8% [418/1,137] v 28.6% [392/1,369]; P < .001; Fig 2A). Proportional AYA enrollment at non-CCOP sites also decreased significantly between these intervals (29.1% [8,189/28,115] v 27.3% [8,168/29,944]; P < .001), including in therapeutic studies (33.1% [3,357/10,145] v 30.1% [3,184/10,297]; P < .001; Fig 2A), although to a lesser extent. Whereas proportional AYA enrollment was greater at CCOP sites compared with non-CCOP sites (36.8% v 33.1%; P = .01) during 2004 through 2008, during 2009 through 2013 it was lower (28.6% v 30.1%; P = .09). Across studies classified by cancer type, no significant changes in proportional AYA enrollment were observed at CCOP sites, except for a decrease in AYA enrollment onto studies of ALL (33.9% [108/319] v 23.6% [144/611]; P = .001; Fig 2B). Overall, cancer-specific AYA proportional enrollment patterns were similar between CCOP and non-CCOP sites; however, at non-CCOP sites, no change was observed for ALL but significant increases were seen in enrollment of AYA with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and in rhabdomyosarcoma (Fig 2C). Finally, we evaluated how the proportion of AYA enrollments onto cancer control studies compared with enrollment onto therapeutic studies during 2004 to 2008 and 2009 to 2013. The proportional enrollment of AYAs was significantly lower in cancer control than therapeutic studies during both periods (25.6% [31/121] v 36.8% [418/1,137], P = .017; and 22.1% [50/226] v 28.6% [392/1,369], P = .045, respectively), and did not increase over time (Fig 2D).

FIG 2.

(A) Proportion of CCOP and non-CCOP study enrollments that were AYA, by study type and time interval. The proportional enrollment of AYAs in all COG studies and in therapeutic studies, in particular, decreased significantly during the 5-year intervals 2004 through 2008 and 2009 through 2013 (see Methods for calculation of AYA proportional enrollment). (B) Proportion of CCOP therapeutic study enrollments that were AYA, by cancer type and time interval. The proportional enrollment of AYAs in trials classified by cancer type did not change significantly during the study intervals, except for a decrease on ALL studies. (C) Proportion of non-CCOP therapeutic study enrollments that were AYA, by cancer type and time interval. The proportional enrollment of AYAs in trials classified by cancer type did not change significantly during the study intervals, except for an increase in AYA patients with AML and RMS. (D) Proportion of CCOP therapeutic study enrollments versus cancer control study enrollments that were AYA, by time interval. The proportional enrollment of AYAs onto cancer control studies at CCOP sites was significantly lower than in therapeutic studies during both 2004 through 2008 and 2009 through 2013. ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; AYA, adolescent and young adult; CCOP, Community Clinical Oncology Program; Ewing, Ewing sarcoma; Hodgkin, Hodgkin lymphoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; OS, osteosarcoma; RMS, rhabdomyosarcoma.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study analyzing AYA enrollment patterns in NCI-sponsored cooperative group trials through the CCOP mechanism. In so doing, we have also obtained insights into AYA clinical trials activity in the setting of predominantly community-based practice compared with that of institutions that include traditional academic centers. As illustrated by this study, improving enrollment of AYAs in clinical trials remains a challenge in both settings. The CCOP was developed to enhance participation of community-based and minority populations in NCI-funded clinical trials, especially cancer control studies. Whereas our data show that proportional enrollment onto cancer control studies was roughly double at CCOP compared with non-CCOP sites, the AYA enrollment proportion was significantly lower. This suggests that simply being community based, focusing on health disparity populations, having a shared infrastructure involving pediatric and adult oncologists at many sites, and offering relevant trials were not enough to drive AYA enrollment.

Although several factors have been proposed to influence AYA clinical trial enrollment, the availability of open trials is thought to be of fundamental importance.11,12,16 Availability of an NCI-sponsored clinical trial implies that the trial is offered through the NCTN and has been activated at the NCTN site where an AYA patient seeks cancer care. Because our study analyzed actual enrollments from all COG-affiliated institutions, the clinical trials represented here were, by definition, available to these AYA patients. However, another factor potentially influencing enrollment is geographic accessibility of treatment sites where NCI-sponsored clinical trials are conducted. We hypothesized that such clinical trials were more accessible at CCOP sites because the majority of these sites were located in the community setting, where most AYAs are treated.15-18 CCOP sites were provided resources intended to improve patient enrollment, including dedicated research funding, access to clinical trials and research networks, and support for patient recruitment and data collection.19-21,23,31 Further, one third of CCOP sites were served by both pediatric and medical oncology practices, which offered opportunities for collaboration that might have been efficacious for diagnosing and treating cancer across the AYA age spectrum.30 Despite these favorable program-level characteristics, our data indicate that CCOP sites were no more effective than non-CCOP sites in enrolling AYA patients to COG trials. Because we used proportional enrollment as our metric of comparison, the validity of our findings is independent of the number of COG clinical trials that were available for AYAs. This is because at any given time, the same trials were available throughout the COG to both CCOP and non-CCOP sites. Although the total number of enrollments between the 5-year periods might be expected to vary according to clinical trial availability, proportional enrollment of AYAs is less likely to do so. Thus, our finding of declining proportional enrollment of AYAs over the past decade is concerning, given the attention that has been given to the AYA problem of inferior survival improvement and its correlation with low participation in clinical trials.32 This is particularly true considering that the number of AYA-enrolling trials actually increased over our study period.

Unfortunately, our study is unable to determine the reason why AYA accrual proportion in COG studies declined over time. It is notable that the decline occurred at both CCOP and non-CCOP sites. One potential explanation is that a shift in AYA accrual from COG to adult cooperative group trials occurred during the study period. However, this seems unlikely to have contributed substantially. For most AYA cancers, there is relatively little overlap in trials offered concurrently by COG and the adult groups. Although there is some potential overlap for ALL, AML, Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), none of the COG trials enrolled across the entire AYA age spectrum, and some were limited to age 21 years and younger. Further, any overlap varied over time according to clinical trial activations and closures. There has been virtually no overlap for Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma because such trials are not routinely offered by the adult-focused groups. Further, in a study by Seibel et al33 that examined AYA accrual onto NCI trials from 2000 to 2010, declining AYA enrollment was noted across all cooperative groups; static or decreasing accrual of patients 20 to 39 years old was noted in virtually every AYA cancer, including AML, HL, NHL, breast, gynecologic, soft tissue, bone, colon, and others. The most likely AYA cancer in which an enrollment shift to adult groups might have occurred is ALL, the only malignancy in which we detected a significant decline in proportional AYA enrollment among the CCOPs (Fig 2B). Although C10403, a Cancer and Leukemia Group B–sponsored phase II study of a pediatric-inspired regimen for adults diagnosed with ALL, was accruing for part of our study period, it was not activated until 2007, required 2 to 3 years to reach anticipated accrual rates, and ultimately enrolled 318 patients, only one fifth of whom came from participating CCOPs.34 Our findings and these additional observations make clear that availability of a mechanism for accurately tracking AYA enrollments will be critical for understanding changes over time, especially in response to interventions designed to improve AYA accrual to NCI trials. Indeed, doing so would realize a major objective of the NCTN, which is to increase intergroup collaboration in the conduct of NCI-funded trials.

Our study illustrates that significant barriers still exist to increasing AYA participation in clinical oncology trials. Despite these findings, there is reason to believe that the CCOP, now NCORP, represents a potential avenue for addressing this problem. The CCOP/NCORP was developed to improve access to NCI-funded trials for under-represented populations, including those located far from traditional NCI-funded comprehensive cancer centers and others affected by health disparities associated with race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status.19,21 In particular, the CCOP/NCORP was charged with increasing enrollments in cancer control trials. Subsequently CCOP/NCORP sites have distinguished themselves as national leaders in supportive-care trial development and enrollment, demonstrating their ability to achieve targeted research objectives.22,24-26 To date, however, neither the CCOP nor NCORP has been given the charge or resources aimed at increasing AYA enrollment. With increased attention to the AYA population in the NCTN, and 43.5% of NCORPs now having combined adult and pediatric sites, this network is even better positioned for designing and testing strategic interventions to increase AYA recruitment. Potential measures could include steps to enhance physician awareness of low AYA clinical trial accrual, collaboration between the pediatric and medical oncology components for coordinated recruitment and patient care, community outreach to AYAs and primary care providers, and adaptation of other proven comprehensive strategies to make trials more available, accessible, acceptable, and appropriate to AYAs.35

Acknowledgment

Supported by the AFLAC Foundation (M.E.R., D.R.F.), Paul Calabresi Career Development Award for Clinical Oncology (Grant No. K12 CA-132783-04) from the National Cancer Institute (NCI; M.E.R.), and NCI Grant No. U10-CA98543 (D.R.F.).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Michael E. Roth, Ann M. O'Mara, Nita L. Seibel, David S. Dickens, Brad H. Pollock, David R. Freyer

Collection and assembly of data: Michael E. Roth, Ann M. O'Mara, David R. Freyer

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Low Enrollment of Adolescents and Young Adults Onto Cancer Trials: Insights From the Community Clinical Oncology Program

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jop.ascopubs.org/site/misc/ifc.xhtml.

Michael E. Roth

No relationship to disclose

Ann M. O'Mara

Stock or Other Ownership: Pfizer (I)

Nita L. Seibel

No relationship to disclose

David S. Dickens

No relationship to disclose

Anne-Marie Langevin

Research Funding: Roche (Inst)

Brad H. Pollock

Consulting or Advisory Role: Astellas Pharma

David R. Freyer

No relationship to disclose

References

- 1. Adolescent Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group: Closing the Gap: Research and Care Imperatives for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. NIH Publication No. 06-6067. Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al: SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2005. Bethesda, MD, National Cancer Institute, 2008, pp 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bleyer A. Older adolescents with cancer in North America deficits in outcome and research. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002;49:1027–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(02)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleyer A, Budd T, Montello M. Adolescents and young adults with cancer: The scope of the problem and criticality of clinical trials. Cancer. 2006;107(7) suppl:1645–1655. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bleyer A, O'Leary M, Barr R, et al. Cancer Epidemiology in Older Adolescents and Young Adults Ages 15-29 Years of Age, Including SEER Incidence and Survival: 1975-2000. NIH Pub. No. 06-5767. Bethesda, MD, National Cancer Institute, 2006.

- 6.Bleyer A, Montello M, Budd T. US cancer incidence, mortality and survival: Young adults are lagging further behind. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2002;21:389a. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bleyer WA. Cancer in older adolescents and young adults: Epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, survival, and importance of clinical trials. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38:1–10. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke ME, Albritton K, Marina N. Challenges in the recruitment of adolescents and young adults to cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2007;110:2385–2393. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrari A, Montello M, Budd T, et al. The challenges of clinical trials for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(5) suppl:1101–1104. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tai E, Beaupin L, Bleyer A. Clinical trial enrollment among adolescents with cancer: Supplement overview. Pediatrics. 2014;133(suppl 3):S85–S90. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0122B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tai E, Buchanan N, Eliman D, et al. Understanding and addressing the lack of clinical trial enrollment among adolescents with cancer. Pediatrics. 2014;133(suppl 3):S98–S103. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0122D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freyer DR, Seibel NL. The clinical trials gap for adolescents and young adults with cancer: Recent progress and conceptual framework for continued research. Curr Pediatr Rep. 2015;3:137–145. doi: 10.1007/s40124-015-0075-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nass SJ, Beaupin LK, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Identifying and addressing the needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer: Summary of an Institute of Medicine workshop. Oncologist. 2015;20:186–195. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins CL, Malvar J, Hamilton AS, et al. Case-linked analysis of clinical trial enrollment among adolescents and young adults at a National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center. Cancer. 2015;121:4398–4406. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harlan LC, Lynch CF, Keegan TH, et al. Recruitment and follow-up of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: The AYA HOPE Study. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:305–314. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0173-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tai E, Buchanan N, Westervelt L, et al. Treatment setting, clinical trial enrollment, and subsequent outcomes among adolescents with cancer: A literature review. Pediatrics. 2014;133(suppl 3):S91–S97. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0122C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albritton KH, Wiggins CH, Nelson HE, et al. Site of oncologic specialty care for older adolescents in Utah. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4616–4621. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.4103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeager ND, Hoshaw-Woodard S, Ruymann FB, et al. Patterns of care among adolescents with malignancy in Ohio. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006;28:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carpenter WR, Fortune-Greeley AK, Zullig LL, et al. Sustainability and performance of the National Cancer Institute’s Community Clinical Oncology Program. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaluzny A, Brawley O, Garson-Angert D, et al. Assuring access to state-of-the-art care for U.S. minority populations: The first 2 years of the Minority-Based Community Clinical Oncology Program. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1945–1950. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.23.1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCaskill-Stevens W, McKinney MM, Whitman CG, et al. Increasing minority participation in cancer clinical trials: The minority-based community clinical oncology program experience. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5247–5254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.22.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buchanan DR, O’Mara AM, Kelaghan JW, et al. Quality-of-life assessment in the symptom management trials of the National Cancer Institute-supported Community Clinical Oncology Program. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:591–598. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minasian LM, Carpenter WR, Weiner BJ, et al. Translating research into evidence‐based practice. Cancer. 2010;116:4440–4449. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25248. : The National Cancer Institute Community Clinical Oncology Program. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrow GR, Hickok JT, Roscoe JA, et al. Differential effects of paroxetine on fatigue and depression: a randomized, double-blind trial from the University of Rochester Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4635–4641. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palesh OG, Roscoe JA, Mustian KM, et al. Prevalence, demographics, and psychological associations of sleep disruption in patients with cancer: University of Rochester Cancer Center-Community Clinical Oncology Program. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:292–298. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roscoe JA, Heckler CE, Morrow GR, et al. Prevention of delayed nausea: A University of Rochester Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program study of patients receiving chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3389–3395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobs SR, Weiner BJ, Minasian LM, et al. Achieving high cancer control trial enrollment in the community setting: An analysis of the Community Clinical Oncology Program. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;34:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parsons HM, Harlan LC, Seibel NL, et al. Clinical trial participation and time to treatment among adolescents and young adults with cancer: Does age at diagnosis or insurance make a difference? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4045–4053. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Printz C. NCI launches program for community-based clinical research: NCORP replaces 2 previous programs. Cancer. 2014;120:3097–3098. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weiss AR, Nichols CR, Freyer DR: Enhancing adolescent and young adult oncology research within the National Clinical Trials Network: Rationale, progress, and emerging strategies. Semin Oncol 42:740-747, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiner BJ, Jacobs SR, Minasian LM, et al. Organizational designs for achieving high treatment trial enrollment: A fuzzy-set analysis of the Community Clinical Oncology Program. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:287–291. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bleyer A, Montello M, Budd T, et al. National survival trends of young adults with sarcoma: Lack of progress is associated with lack of clinical trial participation. Cancer. 2005;103:1891–1897. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanford B, Luger S, Devidas M, et al. Frontline-treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in older adolescents and young adults (AYA) using a pediatric regimen is feasible: Toxicity results of the prospective US Intergroup Trial C10403 (Alliance) Blood. 2013;122 3903. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Seibel N, Hunsberger S, O'Mara AM, et al: Adolescent and young adult oncology (AYAO) patient enrollments onto National Cancer Institute (NCI)-supported trials from 2000 to 2010. J Clin Oncol 32:5s, 2014 (suppl; abstr 10058)

- 35.Fern LA, Lewandowski JA, Coxon KM, et al. Available, accessible, aware, appropriate, and acceptable: A strategy to improve participation of teenagers and young adults in cancer trials. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e341–e350. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]