Abstract

Background: Surgical site infections (SSI) occur in 1.8%–9.2% of women undergoing cesarean section (CS) and lead to greater morbidity rates and increased treatment costs. The aim of the study was to evaluate the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of dialkylcarbamoyl chloride (DACC) impregnated dressings to prevent SSI in women subject to CS.

Methods: Randomized, controlled trial was conducted at the Mazovian Bródno Hospital, a tertiary care center performing approximately 1300 deliveries per year, between June 2014 and April 2015. Patients were randomly allocated to receive either DACC impregnated dressing or standard surgical dressing (SSD) following skin closure. In order to analyze cost-effectiveness of the selected dressings in the group of patients who developed SSI, the costs of ambulatory visits, additional hospitalization, nursing care, and systemic antibiotic therapy were assessed. Independent risk factors for SSI were determined by multivariable logistic regression.

Results: Five hundred and forty-three women undergoing elective or emergency CS were enrolled. The SSI rates in the DACC and SSD groups were 1.8% and 5.2%, respectively (p = 0.04). The total cost of SSI prophylaxis and treatment was greater in the control group as compared with the study group (5775 EUR vs. 1065 EUR, respectively). Independent risk factors for SSI included higher pre-pregnancy body mass index (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.08; [95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.0–1.2]; p < 0.05), smoking in pregnancy (aOR = 5.34; [95% CI: 1.6–15.4]; p < 0.01), and SSD application (aOR = 2.94; [95% CI: 1.1–9.3]; p < 0.05).

Conclusion: The study confirmed the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of DACC impregnated dressings in SSI prevention among women undergoing CS.

Cesarean section (CS) remains to be one of the most common surgical procedures performed worldwide and available data indicate that surgical interventions constitute approximately 0.4%–40.5% of all deliveries [1]. Depending on the definition and the observational period, surgical site infection (SSI) occurs in about 1.8%–9.8% of all CS patients and leads to greater morbidity rates, prolonged hospitalization, and increased number of hospital readmissions [2–9]. Post-cesarean SSI has been estimated to extend the period of hospitalization by 4 d, and at the same time generating an additional cost of 3716 EUR per patient [9].

A recently published pilot study revealed a downward trend in SSI rates after CS if dialkylcarbamoyl chloride (DACC) impregnated dressings were used as method of post-operative SSI prevention [10]. The characteristic feature of the dressing, whose fibers were covered with a hydrophobic derivate of fatty acids, is its solely physical mechanism of action. It uses the interaction between hydrophobic molecules in the presence of aqueous medium, as well as the fact that the majority of pathogens responsible for the development of SSIs demonstrate moderate to high cell surface hydrophobicity (CSH) [11]. High CSH allows microorganism to adhere to cells and to initiate infection, at the same time causing their aggregation on the surface of the impregnated dressing, decreasing both their number in the wound bed and proliferation [12–16]. Described mechanism of action is not associated with the release of additional antimicrobial substances, thus eliminating the risk of cytotoxicity and sensitization, which is particularly important during the periods of puerperium and lactation [16]. To date, the efficacy of DACC-impregnated dressings has been proven in the treatment of venous, arterial and pressure ulcers, burns, diabetic foot, and hard-to-heal post-traumatic and post-operative surgical incisions [17–20].

Taking into consideration the steadily growing CS rates, as well as factors that are responsible for impaired wound healing in women of reproductive age, such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, or smoking, it is vital to search for new, efficient, and safe strategies of preventing obstetric SSI. Also, from the point of view of healthcare system economics, it is important to avoid additional costs, which would allow for a widespread application rather than in high-risk patients only. Therefore, the aim of the study was to evaluate the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of DACC impregnated dressings in the prevention of post-operative SSI among CS women.

Patients and Methods

Setting and study population

The single-blinded, randomized, controlled clinical study was conducted between June 2014 and April 2015 at the Mazovian Bródno Hospital, a tertiary referral center and a clinical hospital of the Medical University of Warsaw. Local Ethics Committee approved of the study (reference no. KB/127/2014 received on June 10, 2014) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (reference no. NCT02168023).

The inclusion criteria were: Patient age >18 y, emergency or elective CS, singleton or multiple pregnancy, mental and physical capacity to consent to participation in a clinical trial, CS performed by transverse skin incision followed by a transverse uterine incision in its lower segment, antibiotic prophylaxis administered zero to 30 min before the surgery, and wound irrigation with octenidine solution before subcutaneous tissue closure.

The patients were randomly assigned to two groups, depending on the applied dressing. Patients with DACC impregnated dressing (Sorbact Surgical Dressing®, ABIGO Medical AB, Sweden) constituted the study group, whereas women with standard surgical dressing (SSD) (Tegaderm + Pad®, 3M Health Care, St. Paul, MN) were recruited as control groups. Simple randomization with the 1:1 allocation ratio, conducted by an operating room (OR) nurse, was used to alternate the patients; even number: DACC dressing, and odd number: SSD. For masking purposes, all dressings were placed in white envelopes and sealed. The surgical team was blinded to the type of dressing until skin closure.

Data on patient demographics, peri- and post-operative course were collected from hospital medical records. Demographic parameters included: Age, race, pre-pregnancy weight, weight gain during pregnancy, height, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), parity, gestational age; presence of diabetes mellitus (pre-gestational or gestational diabetes), hypertension (chronic hypertension or pregnancy-induced hypertension); smoking in pregnancy, history of previous CS, and presence of singleton/multiple pregnancy.

Peri- and post-operative parameters included: Type of dressing; mode of CS (emergency, elective); duration of the surgery; surgeon experience (resident, assistant specialist, consultant); type of anesthesia (spinal, general); presence of meconium stained amniotic fluid (MSAF); hemoglobin concentration 24 h before and 24 h after the surgery; receipt of blood transfusion, and length of post-operative hospital stay.

SSI-related parameters included: Presence of superficial or deep SSI during the first 14 d after the surgery, wound dehiscence; onset of the first symptoms of SSI; the need for systemic antibiotic therapy, hospital re-admission and/or re-operation; the number of ambulatory visits; length of additional hospitalization, and identification of the pathogen responsible for SSI.

The technique of a transverse skin incision (Pfannenstiel) followed by a transverse uterine incision in its lower segment was used in all women, as described previously [10]. For subcutaneous tissue and skin incision closure, single monofilament absorbable suture (Monosyn 2/0, B. Braun Melsungen AG, Germany) and subcuticular continuous monofilament non-absorbable suture (Prolene 2-0, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ), were used respectively. All patients received antibiotic prophylaxis (1g of cefazolin) administered zero to 30 min before the surgery according to Polish National Consultants of General Surgery and Clinical Microbiology recommendations and wound irrigation with octenidine solution (Octenisept®, Schülke & Mayr GmbH, Germany) proceeded subcutaneous tissue closure [21]. Octenidine is a cationic, surface active, topical antimicrobial agent with high bactericidal and fungicidal activity, and cytotoxicity similar to that of other common antiseptics such as chlorhexidine [22].

The study plan resembled the one described in the pilot study [10]. Briefly, the dressing was left in situ for the first 48 h post-operatively in all participants, unless there were reasons for replacement, e.g., wound hemorrhage or detachment of the dressing. After that time, the dressing was removed and the first clinical assessment of wound healing was performed. The patients were discharged home on post-operative day three, unless contraindicated, and recommended to revisit on day seven for skin suture removal and second wound evaluation. Third and final wound assessment was scheduled for post-operative day 14. Patients who failed to report for follow-up visits were excluded from the final analysis. Each wound assessment during patient hospitalization, the follow-up visits, or in case of patient's self-referral to an ambulatory center, was performed by one of two authors (PS, MB), blinded to the type of the dressing used.

Study outcome definitions

The symptoms of superficial or deep SSI were analyzed according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria [23]. Wound dehiscence was defined as separation of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, or fascia, resulting from infection. Time of primary hospitalization was defined as period from the day of surgery (day zero) to discharge from the hospital. Time of additional hospitalization was defined as period from the first SSI symptoms to treatment completion and discharge from the hospital (in cases when SSI developed during primary hospitalization and was the main reason for prolonged stay in the hospital), or from day one of re-admission because of SSI until treatment completion and discharge from the hospital (in cases when primary hospitalization was finished). Emergency CS was defined as procedure performed within 30 min of the decision. Surgeon experience was determined on the bases of specialization in obstetrics and years of experience: Resident—physician in specialist training, assistant specialist—specialization in obstetrics for ≤5, consultant—specialization in obstetrics for >5 y.

Cost data analysis and definitions

In case of SSI occurrence, the following costs were analyzed: Systemic antibiotic therapy, ambulatory visits, additional hospitalization, and additional nursing care. The costs were calculated in Polish zloty (PLN) and then converted to Euro (EUR), based on the Polish National Bank exchange rate from June 1, 2015 (1 EUR = 4.1 PLN).

The cost of antibiotic therapy, defined as the cost of therapy from day one to the last day of SSI treatment, was calculated on the basis of antibiotic prices from the central hospital pharmacy and according to the manufacturer's specifications. The cost of ambulatory visit was calculated on the basis of classifying the patients into one of the Diagnosis Related Groups of Polish National Health Fund (DRG: W40), based on the diagnosis from the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems v.10 (ICD-10-CM; o86.0—infection of obstetric surgical wound; o90.0—disruption of cesarean delivery wound), and the performed procedure, in accordance with the International Classification System for Surgical, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures v.5.22 (ICD-9-CM; 86.28—non-excisional debridement of wound, infection or burn; 93.57—application of another wound dressing). Using the abovementioned data, the cost of a single ambulatory visit was estimated at 54 PLN (13 EUR). The costs of additional hospitalization in SSI patients who required prolonged primary hospitalization or readmission, together with the costs of additional nursing care obtained from the hospital financial office, amounted to 316 PLN (77 EUR) and 173 PLN (42 EUR) per day, respectively.

In order to determine the total costs of prophylaxis and treatment of SSI in both groups, the costs mentioned above were supplemented with the costs of dressings based on mean retail prices: DACC 11.5 PLN (2.8 EUR) and SSD 20 PLN (4.9 EUR).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the R package v. 3.0.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. For categorical variables, the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test were applied. The p-value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

In order to identify the factors responsible for post-operative SSI in women after CS, univariate logistic regression, followed by multivariable logistic regression with backward selection based on the Akaike Information Criterion, were performed.

On the basis of the pilot study results, power analysis indicated that a sample size of 248 for each of the two groups was required to detect a difference in SSI proportion, with a power of 90% and α = 0.05.

Results

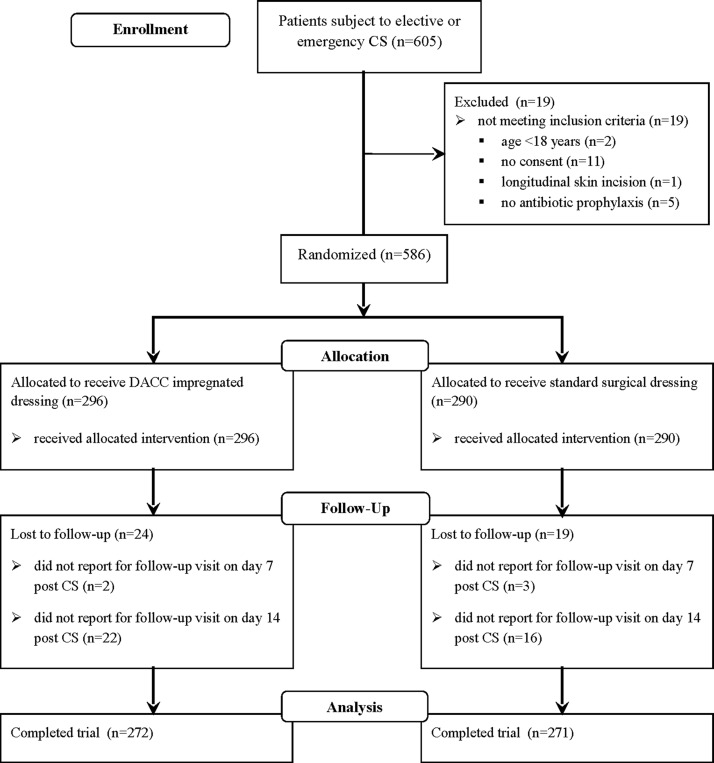

During the study period, between June 2014 and April 2015, there were 1144 deliveries, including 605 cesarean sections (52.9%), at the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Oncology (Fig. 1). Among the women undergoing CS, 19 failed to meet the inclusion criteria: Two were <18 y of age, 11 were not in the capacity to or failed to consent to participation in the study, one patient had CS performed by a longitudinal skin incision, and five patients did not receive antibiotic prophylaxis. Out of the 586 patients who were deemed eligible for the study and who were randomly assigned into either the DACC group (study group, n = 296) or the SSD group (control group, n = 290), 43 (7.3%) failed to report for follow-up visits and were excluded from further analysis. In the final stage, the study and control groups consisted of 272 and 271 patients, respectively.

FIG. 1.

CONSORT 2010 flow diagram of the recruitment process and randomization. CS, cesarean section; DACC, dialkylcarbamoyl chloride

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. There were no substantial differences between the DACC and the SSD groups with regard to patient demographics and peri-operative course. Surgical site infections were observed substantially more often in the SSD group (Table 2). Incisional SSIs occurred during the first 14 post-operative days in 5.2% of patients from the control group as compared with 1.8% of women from the study group (p = 0.04). No statistically significant differences were found as far as the presence of post-operative wound dehiscence, receipt of systemic antibiotic therapy, or re-admission rates were concerned. Regardless of the fact that women who received the DACC dressing did not require systemic antibiotic therapy and additional hospitalization, the number of ambulatory visits was substantially higher in the study group as compared with the control groups, 4.6 vs. 2.9, respectively (p = 0.02) (Table 2). Mean time of additional hospitalization in the SSD group was 8.2 d. In both groups there were no cases of SSIs in patients with diabetes mellitus, both pre-existing before pregnancy and gestational, and with chronic arterial hypertension. All study participants were HIV-negative.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Who Underwent Cesarean Section during the Study Period from June 2014 to April 2015

| Study group (n = 272) | Control group (n = 271) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 31.2 ± 4.8 (18–43) | 30.6 ± 4.8 (18–44) | .08 |

| ≤20 | 5 (1.8%) | 4 (1.5%) | .63 |

| 21–30 | 114 (42.0%) | 126 (46.5%) | |

| 31–40 | 148 (54.4%) | 134 (49.4%) | |

| >40 | 5 (1.8%) | 7 (2.6%) | |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 269 (98.9%) | 268 (98.9%) | >.999 |

| Non-Caucasian | 3 (1.1%) | 3 (1.1%) | |

| Pre-pregnancy weight (kg) | 65.8 ± 13.2 (40–138) | 66.4 ± 14.6 (39–129) | .69 |

| Weight gain during pregnancy (kg) | 14.3 ± 6.0 (0–40) | 14.4 ± 5.6 (0–38) | .64 |

| Height (m) | 1.66 ± 0.06 (1.48–1.81) | 1.65 ± 0.06 (1.4–1.84) | .55 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 23.9 ± 4.5 (16.3–47.7) | 24.2 ± 4.9 (14.5–43.6) | .57 |

| BMI <25 | 193 (70.9%) | 176 (64.9%) | .31 |

| BMI ≥25 and <30 | 53 (19.5%) | 62 (22.9%) | |

| BMI ≥30 | 26 (9.6%) | 33 (12.2%) | |

| Parity | |||

| Primiparous | 131 (48.2%) | 150 (55.4%) | .11 |

| Multiparous | 141 (51.8%) | 121 (44.6%) | |

| Gestational age (wks) | 38.1 ± 2.4 (24–41) | 38 ± 2.5 (24–41) | .92 |

| < 37 wks | 32 (11.8%) | 46 (17.0%) | .11 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 26 (9.6%) | 35 (12.9%) | .28 |

| PGDM | 9 (3.3%) | 8 (2.9%) | |

| GDM | 17 (6.3%) | 27 (10.0%) | |

| Hypertension | 24 (8.8%) | 34 (12.5%) | .08 |

| Pre-pregnancy HTN | 11 (4.0%) | 8 (2.9%) | |

| PIH | 13 (4.8%) | 26 (9.6%) | |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 20 (7.3%) | 20 (7.4%) | >.999 |

| Mode of CS | |||

| Elective | 214 (78.7%) | 211 (77.9%) | .90 |

| Emergency | 58 (21.3%) | 60 (22.1%) | |

| Previous CS | 96 (35.3%) | 87 (32.1%) | .49 |

| Multiple pregnancy | 5 (1.8%) | 7 (2.6%) | .76 |

| Duration of surgery (min.) | 36.3 ± 9.0 (17–82) | 36.7 ± 11.4 (17–125) | .94 |

| ≤25 | 35 (12.9%) | 34 (12.5%) | .86 |

| 25–50 | 218 (80.1%) | 221 (81.5%) | |

| >50 | 19 (7.0%) | 16 (6.0%) | |

| Surgeon experience | |||

| Resident | 106 (39.0%) | 113 (41.7%) | .56 |

| Assistant specialist | 73 (26.8%) | 77 (28.4%) | |

| Consultant | 93 (34.2%) | 81 (29.9%) | |

| Type of anesthesia | |||

| Spinal | 225 (82.7%) | 221 (81.6%) | .81 |

| General | 47 (17.3%) | 50 (18.4%) | |

| MSAF | 20 (7.3%) | 21 (7.7%) | .99 |

| Pre-operative Hgb (g/dL) | 12.2 ± 1.0 (8.3–14.9) | 12.3 ± 1.1 (8.7–16.1) | .77 |

| Post-operative Hgb (g/dL) | 10.9 ± 1.0 (7.1–14.2) | 11 ± 1.2 (6.5–14.6) | .39 |

| Δ Hgb (g/dL) | 1.3 ± 0.7 (0.1–3.5) | 1.3 ± 0.9 (0.1–6.5) | .17 |

| Blood transfusion | 6 (2.2%) | 4 (1.5%) | .75 |

| Length of post-operative hospital stay (d) | 4.3 ± 1.9 (3–14) | 4.6 ± 2.1 (3–15) | .22 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD/ (range) or as frequency (%).

BMI = body mass index; PGDM = pre-gestational diabetes mellitus; GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus; HTN = hypertension; PIH = pregnancy induced hypertension; CS = cesarean section; MSAF = meconium stained amniotic fluid; Hgb = hemoglobin concentration; Δ Hgb = change in hemoglobin concentration.

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Study Outcomes

| Study group (n = 272) | Control group (n = 271) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients with SSI (%) | 5 (1.8) | 14 (5.2) | .04 |

| No. of patients with SSI and wound dehiscence (%) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | >.99 |

| No. of patients with SSI who required systemic antibiotic treatment (%) | 0 | 4 (1.5) | .13 |

| No. of patients with SSI who required hospital readmission (%) | 0 | 3 (1.1) | .24 |

| No. of patients with SSI who required surgical intervention (%) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Study group (n = 5) | Control group (n = 14) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time of SSI occurrence (d) | 7.4 ± 1.14 (6-9) | 9.1 ± 3.6 (3–14) | .26 |

| No. of ambulatory visits | 4.6 ± 1.67 (2-6) | 2.9 ± 1.1 (1–4) | .02 |

| Length of additional hospitalization (d) | 0 | 8.2 ± 3.2 (5–11) | .22 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD/ (range) or as frequency (%)

SSI = surgical site infection.

Enterobacteriaceae, coagulase-positive and negative staphylococci, anaerobes, Enterococcaceae, and Streptococcus sp. were the pathogens responsible for most SSI cases in both groups (Table 3). Microbiological analysis revealed strains of Enterobacteriaceae as the dominant group of pathogens isolated in patients from the SSD group, accounting for more than half of the identified microorganisms (56.25%). A similar correspondence was not observed in the DACC group, where Enterobacteriaceae constituted 9.1% of the isolated strains, with no dominant group of pathogens.

Table 3.

Microorganisms Isolated from Surgical Site Infections during the Study Period from June 2014 to April 2015

| Study group | Control group | |

|---|---|---|

| Microorganisms | No. (%) | No. (%) |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 1 (9.1) | 9 (56.25) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 0 | 3 |

| Proteus mirabilis | 0 | 1 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 0 | 2 |

| Escherichia coli | 1 | 3 |

| Coagulase-positive Staphylococci | 2 (18.2) | 1 (6.25) |

| MSSA | 2 | 1 |

| Coagulase-negative Staphylococci | 1 (9.1) | 1 (6.25) |

| MSSE | 1 | 0 |

| Staphylococcus hominis | 0 | 1 |

| Anaerobes | 2 (18.2) | 1 (6.25) |

| Bacteroides fragilis | 1 | 0 |

| Prevotella bivia | 0 | 1 |

| Peptoniphilus asaccharolyticus | 1 | 0 |

| Enterococcaceae | 2 (18.2) | 1 (6.25) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 2 | 1 |

| Streptococcus sp. | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 1 (9.1) | 3 (18.75) |

| Total | 11 (100) | 16 (100) |

MSSA = methicillin susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; MSSE, methicillin susceptible Staphylococcus epidermidis

The univariate analysis revealed pre-pregnancy BMI of ≥30 kg/m2 (odds ratio [OR] = 4.5; [95% CI: 1.3–14.8]; p = 0.009), pregnancy induced hypertension (OR = 5.1; [95% CI: 1.4–16.2]; p = 0.008), and smoking in pregnancy (OR = 5.0; [95% CI: 1.3–15.7]; p = 0.009) to be the factors that substantially increase the risk for SSI, and application of the DACC impregnated dressing as the factor that lowers the risk (OR =0.3; [95% CI: 0.09–1.03]; p = 0.04) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate Analysis of Risk Factors for Surgical Site Infection in Females after Cesarean Section

| No. (%) of patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSI (n = 19) | No SSI (n = 524) | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age (y) | ||||

| ≤30 | 10 (52.6) | 239 (45.6) | 1.0 | - |

| 31–40 | 8 (42.1) | 274 (52.3) | 0.7 (0.23–2.0) | .48 |

| >40 | 1 (5.3) | 11 (2.1) | 2.2 (0.4–17.9) | .41 |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 18 (94.7) | 519 (99.0) | 1.0 | - |

| Non-Caucasian | 1 (5.3) | 5 (1.0) | 5.7 (0.1–55.2) | .19 |

| Weight gain during pregnancy (kg) | ||||

| ≤10 | 7 (37.0) | 132 (25.0) | 1.0 | - |

| >10 | 12 (63.0) | 392 (75.0) | 0.6 (0.2–1.8) | .28 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| BMI <25 | 9 (47.4) | 360 (68.7) | 1.0 | - |

| BMI ≥25 and <30 | 4 (21.0) | 111 (21.2) | 0.99 (0.23–3.2) | >.999 |

| BMI ≥30 | 6 (31.6) | 53 (10.1) | 4.5 (1.3–14.8) | .009 |

| Parity | ||||

| Primiparous | 14 (73.7) | 267 (51.0) | 2.7 (0.9–9.7) | .06 |

| Gestational age | ||||

| < 37 wks | 5 (26.3) | 73 (13.9) | 2.2 (0.6–6.7) | .17 |

| Hypertension | ||||

| PIH | 5 (26.3) | 34 (6.5) | 5.1 (1.4–16.2) | .008 |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 5 (26.3) | 35 (6.7) | 5.0 (1.3–15.7) | .009 |

| Mode of CS | ||||

| Elective | 13 (68.4) | 412 (78.6) | 1.0 | - |

| Emergency | 6 (31.6) | 112 (21.4) | 1.7 (0.5–4.9) | .27 |

| Previous CS | 3 (15.6) | 180 (34.4) | 0.4 (0.7–1.28) | .14 |

| Multiple pregnancy | 2 (10.5) | 10 (1.9) | 6.0 (0.6–31.6) | .06 |

| Duration of surgery (min.) | ||||

| ≤25 | 4 (21.0) | 65 (12.4) | 1.0 | - |

| >25 | 15 (79.0) | 459 (87.6) | 0.53 (0.16–2.27) | .28 |

| Surgeon experience | ||||

| Resident | 8 (42.1) | 211 (40.3) | 1.0 | - |

| Assistant specialist | 5 (26.3) | 145 (27.7) | 0.9 (0.2–3.2) | >.999 |

| Consultant | 6 (31.6) | 168 (32.0) | 0.9 (0.3–3.2) | >.999 |

| Type of anesthesia | ||||

| Spinal | 14 (73.7) | 432 (82.4) | 1.0 | - |

| General | 5 (26.3) | 92 (17.6) | 1.7 (0.5–5.1) | .36 |

| MSAF | 3 (15.8) | 38 (7.2) | 2.4 (0.4–8.9) | .17 |

| Pre-operative Hgb | ||||

| ≤12 g/dL | 6 (31.6) | 191 (36.4) | 0.8 (0.2–2.3) | .81 |

| Post-operative Hgb | ||||

| ≤10 g/dL | 3 (15.8) | 97 (18.5) | 0.8 (0.15–3.0) | >.999 |

| Δ Hgb | ||||

| ≥3g/dL | 1 (5.3) | 9 (1.7) | 3.2 (0.07–25.1) | .30 |

| Length of post-operative hospital stay (d) | ||||

| ≤5 | 13 (68.4) | 393 (75.0) | 1.0 | - |

| 6–10 | 5 (26.3) | 123 (23.5) | 1.2 (0.3–3.8) | .78 |

| >10 | 1 (5.3) | 8 (1.5) | 3.7 (0.08–31.9) | .27 |

| Dressing type | ||||

| SSD | 14 (73.7) | 257 (49.1) | 1.0 | - |

| DACC | 5 (26.3) | 267 (50.9) | 0.3 (0.09–1.03) | .04 |

SSI = surgical site infection; BMI = body mass index; PIH = pregnancy induced hypertension; CS = cesarean section; MSAF = meconium stained amniotic fluid; Hgb = hemoglobin concentration; Δ Hgb = change in hemoglobin concentration; SSD = standard surgical dressing; DACC = dialkylcarbamoyl chloride-impregnated dressing; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

In order to identify independent risk factors for SSI, a separate multivariable logistic regression with backward selection was performed. The following parameters were found to influence the risk for SSI: Pre-pregnancy BMI (aOR = 1.08; [95% CI: 1.0–1.2]; p < 0.05), smoking in pregnancy (aOR = 5.34; [95% CI: 1.6–15.4]; p < 0.01) and SSD application (aOR = 2.94; [95% CI: 1.1–9.3]; p < 0.05).

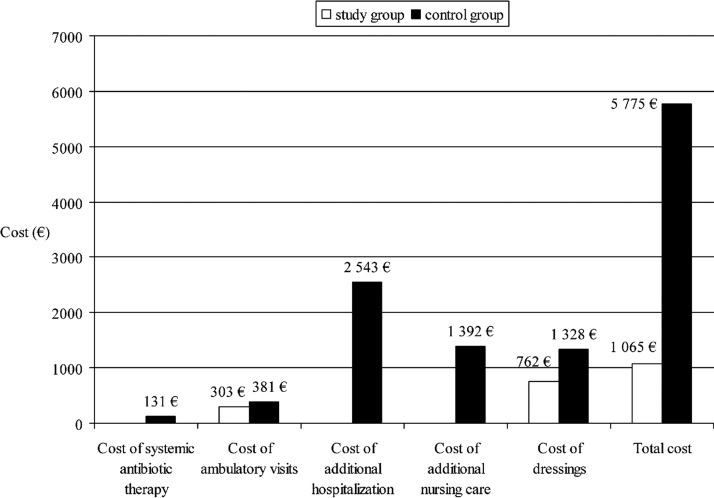

Total estimated cost of SSI prophylaxis and treatment was greater in the control group as compared with the study group, and amounted to 5775 EUR vs. 1065 EUR, respectively (Fig. 2). In the study group it comprised only the cost of ambulatory visits, whereas in the control group total cost encompassed additional expenses because of prolonged hospitalization and additional nursing care. Similarly, systemic antibiotic treatment with metronidazole, cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, amoxicillin, ciprofloxacin, or gentamicin used alone or in combination was necessary only in patients in the control group.

FIG. 2.

Cost of treatment attributable to surgical site infection after cesarean section by dressing type.

Discussion

The presented study was a single-center, randomized controlled trial, aiming to evaluate the efficacy of DACC impregnated dressings to prevent SSI in women after CS. To the best of our knowledge, it has been the first prospective study on the use of DACC dressings in a large cohort of pregnant women.

Our results confirmed effectiveness of the DACC dressings in SSI prevention after CS. Application of the hydrophobic dressing resulted in a decreased rate of SSI and its considerably milder course, with no need for systemic antibiotic therapy and hospital readmissions. As a consequence, the total cost of SSI treatment was lower in the DACC group and was a result of ambulatory visits only. Despite the fact that the total number of the ambulatory visits was substantially higher in the study group, the dominant element in the total treatment cost was the length of additional hospitalization, with mean duration of 8 d in the group with SSD.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed obesity, smoking, and the use of a standard occlusive dressing as the three independent factors that increase the risk for incisional SSI after CS. The adverse effects of the first two factors have been well-documented in the literature [2,3,5,7,8]. In case of obesity, excessive thickness of subcutaneous tissue is believed to cause tissue hypoperfusion and hypoxygenation, impeding the healing process and antibiotic penetration [24]. The risk of SSI is often additionally increased by the presence of hyperglycemia, prolonged surgery time because of technical difficulties, the need for a longer skin incision, and more blood loss. Also, proper wound hygiene and care may be hampered by the location of the incision between skin folds, what may predispose to the development of infection. As far as smoking is concerned, the components of tobacco smoke cause tissue hypoxia, impair the function of inflammatory cells, and limit fibroblast proliferation and migration, thus delaying wound healing [25–27].

The type of dressing used in prevention of SSI after obstetric operations is of the utmost importance from the point of view of the study goals. Similarly to subcutaneous drains or surgical staples used for skin closure, the type of the applied dressing may affect the risk of SSI [2,5]. Obtained results revealed an almost three-fold increase of SSI risk in patients who received the SSD.

Microorganisms responsible for SSI were similar in both groups, with the exception of more numerous Enterobacteriacae strains found among the control groups, which may be explained by the fact that approximately 25% of Enterobacter spp. strains isolated from surgical incisions are characterized by high CSH, whereas hydrophobic properties are found in 88% of the Enterobacter cloacae strains alone [28]. In case of Klebsiella pneumoniae, CSH is affected by the presence of O-antigen lipopolysaccharide or polysaccharide capsule, making bacteria more hydrophilic and, as a result, less susceptible to adhesion to the hydrophobic surface of the dressing [29]. Neither the abovementioned properties of bacterial strains nor the effect of the remaining factors on the CSH of the isolated pathogens were the subject of the investigation. It has been proven that the use of octenidine solution, just as bacterial culture in carbon dioxide atmosphere in the presence of serum, resembling wound conditions under an occlusive dressing, increase CSH, contrary to antibiotics used in pre-operative prophylaxis [11,16,30].

Our study is subject to several limitations, including the fact that the effectiveness of the impregnated dressings was analyzed in a group of women undergoing CS, which, unlike most surgical patients, constitute young population with few comorbidities. Also, the observed SSI incidence after CS most probably does not reflect the total SSI rate because of the fact that analysis included only superficial and deep SSI, as well as shorter than recommended by the CDC period of observation. Exclusion of organ/space SSI from the analysis was imposed by the fact that the effect of the dressing on the incidence of such infections after CS is limited and the shortened time of the observation, from the recommended 30 d to 14 d, was conditioned by lack of the possibility of effective medical supervision and low patient compliance after that time, as described by Wilson et al. [4]. At the same time, the literature reports indicate that superficial and deep SSIs account for 93%–100% of all cases of SSI following CS, with 78%–100% occurring within 14 d of the surgery [2–4,6,7]. As the subject of the study included only superficial and deep SSI such risk factors as number of vaginal examinations, duration of labor or pre-term rupture of membranes were not included in the analysis, taking into account their correlation with organ/space infections.

To conclude, the use of a DACC-coated dressing decreased the SSI rates among patients after CS and proved its cost-efficacy. Weight reduction before conception, abstaining from smoking in pregnancy, and application of dressings that are effective in SSI prophylaxis, are the key factors which might prevent SSIs after CS.

Acknowledgments

Statistical analyses were done by BioStat (Poland). Language translator Izabella Mrugalska provided assistance in preparing and editing the manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Betrán AP, Marialdi M, Lauer JA, et al. . Rates of caesarean section: Analysis of global, regional and national estimates. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2007;21:98–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen MA, Butler AM, Willers DM, et al. . Risk factors for surgical site infection after low transverse cesarean section. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2008;29:477–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wloch C, Wilson J, Lamagni T, et al. . Risk factors for surgical site infection following caesarean section in England: Results from a multicentre cohort study. BJOG 2012;119:1324–1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson J, Wloch C, Saei A, et al. . Inter-hospital comparison of rates of surgical site infection following caesarean section delivery: Evaluation of a multicentre surveillance study. J Hosp Infect 2013;84:44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alanis MC, Villers MS, Law TL, et al. . Complications of cesarean delivery in the massively obese parturient. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;203:271.e1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadar E, Melamed N, Tzadikevitch-Geffen K, Yogev Y. Timing and risk factors of maternal complications of cesarean section. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2011;283:735–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Opøien HK, Valbø A, Grinde-Andersen A, Walberg M. Post-cesarean surgical site infections according to CDC standards: Rates and risk factors. A prospective cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol 2007;86:1097–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneid-Kofman N, Sheiner E, Levy A, Holcberg G. Risk factors for wound infection following cesarean deliveries. Int J Gyn Obstet 2005;90:10–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenks PJ, Laurent M, McQuarry R, Watkins R. Clinical and economic burden of surgical site infection (SSI) and predicted financial consequences of elimination of SSI from an English hospital. J Hosp Infect 2014;86:24–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stanirowski PJ, Kociszewska A, Cendrowski K, Sawicki W. Dialkylcarbamoyl chloride-impregnated dressing for the prevention of surgical site infection in women undergoing cesarean section: A pilot study. Archives of Medical Science 2016. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2015.47654 (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ljungh A, Wadström T. Growth conditions influence expression of cell surface hydrophobicity of staphylococci and other wound infection pathogens. Microbiol Immunol 1995;39:753–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doyle RJ. Contribution of the hydrophobic effect to microbial adhesion. Microbes Infect 2000;2:391–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gentili S, Gianesini P, Balboni E, et al. . Panbacterial real-time PCR to evaluate bacterial burden in chronic wounds treated with Cutimed™ Sorbact™. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2012;31:1523–1529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ronner AC, Curtin J, Karami N, Ronner U. Adhesion of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to DACC-coated dressings. J Wound Care 2014;23:486–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geroult S, Phillips RO, Demangel C. Adhesion of the ulcerative pathogen Mycobacterium ulcerans to DACC-coated dressings. J Wound Care 2014;23:417–418,422–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ljungh A, Yanagisawa N, Wadström T. Using the principle of hydrophobic interaction to bind and remove wound bacteria. J Wound Care 2006;15:175–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosti G, Magliaro A, Mattaliano V, et al. . Comparative study of two antimicrobial dressings in infected leg ulcers: A pilot study. J Wound Care 2015;24:121–122;124–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hampton S. An evaluation of the efficacy of Cutimed® Sorbact® in different types of non-healing wounds. Wounds UK 2007;3:113–119 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kammerlander G, Locherer E, Süss-Burghart A, et al. . Non-medicated wound dressing as an antimicrobial alternative in wound management. Wounds UK 2008;4:10–18 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haycocks S, Chadwick P, Guttormsen K. Use of DACC-coated antimicrobial dressing in people with diabetes and a history of foot ulceration. Wounds UK 2011;7:108–114 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hryniewicz W, Kulig J, Ozorowski T, et al. . Stosowanie antybiotyków w profilaktyce okołooperacyjnej (Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis). Warsaw: Narodowy Instytut Leków (National Medicines Institute), 2011:1–27 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hübner NO, Siebert J, Kramer A. Octenidyne dihydrochloride, a modern antiseptic for skin, mucous membranes and wounds. Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2010;23:244–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, et al. . Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1999;20:250–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anaya DA, Dellinger E. The obese surgical patient: A susceptible host for infection. Surg Infect 2006;7:473–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen JA, Goodson WH, Hopf HW, Hunt TK. Cigarette smoking decreases tissue oxygen. Arch Surg 1991;126:1131–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorensen LT, Nielsen HB, Kharazmi A, Gottrup F. Effect of smoking and abstention on oxidative burst and reactivity of neutrophils and monocytes. Surgery 2004;136:1047–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong LS, Green HM, Feugate JE, et al. . Effects of “second-hand” smoke on structure and function of fibroblasts, cells that are critical for tissue repair and remodeling. BMC Cell Biol 2004;5:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michalska A, Gospodarek E. Hydrophobic properties of Enterobacter spp. rods. Med Dośw Mikrobiol 2009;61:227–234 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camprubí S, Merino S, Benedí J, et al. . Physicochemical surface properties of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Curr Microbiol 1992;24:31–33 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kustos T, Kustos I, Kilár F, et al. . Effects of antibiotics on cell surface hydrophobicity of bacteria causing orthopedic infections. Chemotherapy 2003;49:237–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]