Abstract

Cellular energy production processes are composed of many Mg2+ dependent enzymatic reactions. In fact, dysregulation of Mg2+ homeostasis is involved in various cellular malfunctions and diseases. Recently, mitochondria, energy-producing organelles, have been known as major intracellular Mg2+ stores. Several biological stimuli alter mitochondrial Mg2+ concentration by intracellular redistribution. However, in living cells, whether mitochondrial Mg2+ alteration affect cellular energy metabolism remains unclear. Mg2+ transporter of mitochondrial inner membrane MRS2 is an essential component of mitochondrial Mg2+ uptake system. Here, we comprehensively analyzed intracellular Mg2+ levels and energy metabolism in Mrs2 knockdown (KD) cells using fluorescence imaging and metabolome analysis. Dysregulation of mitochondrial Mg2+ homeostasis disrupted ATP production via shift of mitochondrial energy metabolism and morphology. Moreover, Mrs2 KD sensitized cellular tolerance against cellular stress. These results indicate regulation of mitochondrial Mg2+ via MRS2 critically decides cellular energy status and cell vulnerability via regulation of mitochondrial Mg2+ level in response to physiological stimuli.

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is the universal energy currency of cells. ATP binds to magnesium ion (Mg2+) to compose biologically functional form, and most of intracellular ATP and Mg2+ assumed to form Mg-ATP complexes. Because both ATP and Mg2+ are mutually and strongly buffered in cytosol, it had been believed that Mg2+ deeply contributes on energy metabolism. Actually, studies performed in vitro has revealed that the variety of enzymatic activities are dependent on [Mg2+]1, and some of the Mg2+-dependent enzymes are operated in mitochondria to sustain the cellular function and viability. Some of enzymatic activities of tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle)2,3 are regulated by [Mg2+], and therefore, computer simulation by a realistic metabolic model of TCA cycle also showed mitochondrial Mg2+ level is most important regulating factor4. Mg2+ homeostasis is crucial for maintenance of electron transport chain5. Moreover, the mitochondrial ATP-Mg/Pi carrier exports mitochondrial ATP into cytosol6,7. Therefore, Mg2+ has been implicated as an important regulator of metabolic status in mitochondria8,9,10.

Mg2+ is an important cation for maintain cellular functions and, therefore, suggested the relation of Mg2+ to various diseases such as cancer, obesity, type 2 diabetes and neurological diseases11,12,13,14. Furthermore, intracellular Mg2+ plays roles as a second messenger in the immune system15,16,17,18, and it has been recognized as a multi-target metabolic regulator8,19. Therefore, regulation of intracellular Mg2+ is critical for maintenance of cellular functions and tissue integrity. To reveal the regulatory mechanism of intracellular Mg2+, we have developed Mg2+ sensitive fluorescence probes and imaging techniques20,21,22,23,24. These intracellular Mg2+ imaging works revealed Mg2+ mobilization in pathological and physiological conditions25,26,27,28, and mitochondria are intracellular Mg2+ stores29. Mitochondria redistribute cytosolic and mitochondrial Mg2+ sufficient to change the cytosolic Mg2+ concentration ([Mg2+]cyto) in response to several physiological stimuli25,26. Recent studies using novel Mg2+ fluorescent probe successfully visualized that mitochondrial Mg2+ concentration ([Mg2+]mito) dynamically changes22,30. However, it is not clear, in cells, how the changes of [Mg2+]mito comprehensively affect the cellular energy metabolism in detail.

Although regulation of [Mg2+]mito has not been elucidated in detail, mitochondrial Mg2+ channel MRS2 is known to be a molecular machinery associated with Mg2+ influx into mitochondria31,32,33,34. The rats with functional inactivation of mutated MRS2 have major mitochondrial deficits with a reduction in ATP, and increased numbers of mitochondria in oligodendrocytes35. Mg2+ uptake into mitochondria via MRS2 is essential for the maintenance of respiratory chain and cell viability5.

In this study, we investigate how dysregulation of mitochondrial Mg2+ homeostasis affects cellular energy maintenance and viability using single-cell fluorescence imaging and metabolomics analysis in Mrs2 knockdown (KD) cells. Mrs2 KD induces disruption of mitochondrial Mg2+ homeostasis, which results in supression of mitochondrial ATP production and increased cellular stress susceptibility. These findings suggest that mitochondrial Mg2+ plays important roles to maintain energy supply in cells, and its dysregulation causes cellular malfunction and multiple diseases.

Results

RNAi-mediated Mrs2 KD in HeLa cells

We investigated the importance of mitochondrial Mg2+ homeostasis by an RNAi-mediated Mrs2 KD in HeLa cells. The best miRNA to knockdown MRS2 expression was selected by comparing loss of Mrs2 mRNA expression in HeLa cells with quantitative real time RT-PCR after 3 days of transfection of miR expression vector (Fig. S1). The miR expression vector #1 was optimal for Mrs2 KD in HeLa cells, and it was used for Mrs2 KD.

Effects of Mrs2 KD on Intracellular Mg2+ Homeostasis

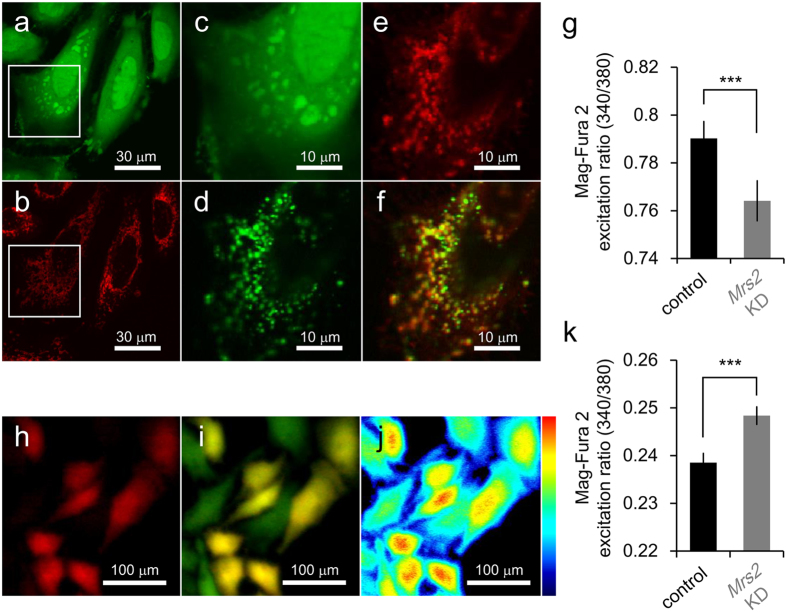

MRS2 is primary Mg2+ uptake machinery in mitochondria31,32,34. To assess the effects of Mrs2 KD on [Mg2+]mito homeostasis, [Mg2+]mito was compared by using a ratiometric Mg2+ indicator Mag-Fura-2. The cell membrane permeabilization protocol was used for the quantification of the [Mg2+]mito36. Briefly, after loading Mag-Fura-2, cytosolic Mag-Fura-2 was washed out by cell membrane permeabilization with a detergent digitonin. While Mag-Fura-2 is normally used for the measurement of [Mg2+]cyto (Fig. 1a–c), the co-localization of Mag-Fura-2 and a mitochondrial marker MitoFluor Red signals was observed after Mag-Fura-2 wash out from cytosol by digitonin treatment (Fig. 1d–f), indicating that this cell membrane permeabilization protocol by using Mag-Fura-2 enables mitochondrial Mg2+ measurement. [Mg2+]mito in Mrs2 KD cells was lower than that in normal cells (Fig. 1g). Mrs2 KD cells were identified by expression of emGFP also coded in miRNA expression vector. [Mg2+]cyto was also estimated with Mag-Fura-2 in normal usage (Fig. 1h–j). The comparative analysis revealed the Mrs2 KD induced an increase in [Mg2+]cyto (Fig. 1k). These results indicate that Mrs2 KD in HeLa cells induces a decrease in [Mg2+]mito and an increase [Mg2+]cyto.

Figure 1. The effects of Mrs2 KD on the intracellular Mg2+ homeostasis.

The images of HeLa cells simultaneously loaded with both Mag-Fura-2 (a) and MitoFluor Red (b). (c–f) The enlarged view of the boxed area in panel a and b. (c,d) The localization of Mag-Fura-2 in the same cell shown in the panel a and b before (c) and after (d) cell membrane permeabilization by digitonin. (e) Localization of MitoFluor Red after cell membrane permeabilization by digitonin. (f) The merged image were shown. (g) The mitochondrial Mg2+ level in control and Mrs2 KD HeLa cells. Comparing the ratio of Mag-Fura-2 fluorescence excited at 340 nm to at 380 nm, indicating mitochondrial Mg2+ level, revealed a decrease in Mrs2 KD cells (n = 148 for the control and n = 105 for Mrs2 KD cells from 5 experiments). (h–j) The images of HeLa cells normally loaded with Mag-Fura-2. (h) Fluorescence image of Mrs2 KD cells labeled with emGFP. (i) The merged fluorescence images of control and emGFP- labeled (red) Mrs2 KD cells loaded with Mag-Fura-2 (green). (j) The fluorescence emission ratio image at excitation of 340 and 380 nm of HeLa cells loaded with Mag-Fura-2. Pseudo color showed the emission ratio of Mag-Fura-2 signals excited at 340 nm to 380 nm. (k) The cytosolic Mg2+ level in control and Mrs2 KD cells. In Mrs2 KD cells, cytosolic Mg2+ level is higher than that in control cells (n = 304 for the control and n = 384 Mrs2 KD cells from 5 experiments).

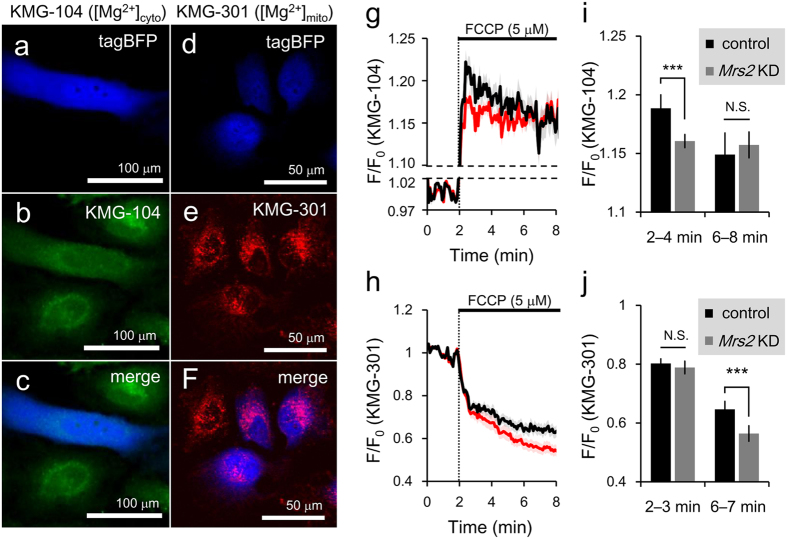

Effects of Mrs2 KD on Mitochondrial Mg2+ Regulatory Systems

The alternation in intracellular distribution of Mg2+ level in Mrs2 KD cells indicates that MRS2 maintain mitochondrial Mg2+ concentration. To investigate the roles of MRS2 on stimulation-induced intracellular Mg2+ redistribution, we visualized cytosolic and mitochondrial Mg2+ dynamics during stimulation with a mitochondrial uncoupler, carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP; 5 μM) in HeLa cells loaded with highly sensitive cytosolic Mg2+ indicator KMG-104 (Fig. 2b,c) or mitochondrial Mg2+ indicator KMG-301 (Fig. 2e,f). To distinguish Mrs2 KD cells from control cells, Mrs2 miR expression vector coding tagBFP was used. As both control and tagBFP-labeled Mrs2 KD cells existed in an observed area of single experiments, the traces of [Mg2+]cyto and [Mg2+]mito in both control and Mrs2 KD cells for comparative analysis were simultaneously obtained in the same batch experiments (Fig. 2a–f). As shown in previous studies reporting FCCP-induced Mg2+ release from mitochondria into the cytosol22,25,26,29, the application of FCCP induced [Mg2+]cyto increase (Fig. 2g). Measurement of [Mg2+]cyto dynamics using KMG-104 revealed that the averaged amplitude of FCCP-induced [Mg2+]cyto increase in 2–4 min (initial phase of [Mg2+]cyto increase) in Mrs2 KD cells was smaller than that in control cells (Fig. 2i, left), supporting the idea that the amount of Mg2+ stored in mitochondria before FCCP treatment is lower in Mrs2 KD cells. The [Mg2+]cyto increase was sustained at least for 8 min in Mrs2 KD cells, whereas [Mg2+]cyto in control cells returned back to the same level of [Mg2+]cyto in Mrs2 KD cells in 6–8 min (Fig. 2i, right). In [Mg2+]mito imaging using KMG-301 (Fig. 2h), in 2–3 min (initial phase of [Mg2+]mito decrease), the averaged amplitudes of FCCP-induced [Mg2+]mito decrease in both cells were not different (Fig. 2j, left). During 6–7 min, the averaged amplitudes of FCCP-induced [Mg2+]mito decrease in Mrs2 KD cells was larger than that in control cells (Fig. 2j, right). These results also indicate that, after the initial phase of FCCP-induced mitochondrial Mg2+ release, mitochondria reuptake the released cytosolic Mg2+ through MRS2, and mitochondria in Mrs2 KD cells failed it. Taken together, MRS2 plays a role as the mitochondrial Mg2+ uptake systems in mammalian cells, and Mrs2 KD causes the deletion of mitochondrial Mg2+ uptake in both steady state and Mg2+ mobilization.

Figure 2. The effects of Mrs2 KD on mitochondrial Mg2+ regulatory system.

(a–c) Representative fluorescence image of control and Mrs2 KD cells loaded with cytosolic Mg2+ indicator KMG-104. (a) Mrs2 KD cells labeled with tagBFP. (b) Control and Mrs2 KD cells stained with KMG-104. (c) The merged image of tagBFP and KMG-104 images. (d–f) Representative fluorescent image of control and Mrs2 KD cells loaded with mitochondrial Mg2+ indicator KMG-301. (d) Mrs2 KD cells labeled with tag BFP. (e) Control and Mrs2 KD cells stained with KMG-301. (f) The merged image of tagBFP and KMG-301 images. (g) Averaged time course of [Mg2+]cyto dynamics in control and Mrs2 KD cells measured with KMG-104. Treatment with mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP (5 μM) triggered the [Mg2+]cyto increase (means ± SEM; black line n = 46 for control cells; red line n = 43 for Mrs2 KD cells from 4 experiments). (h) Averaged time course of [Mg2+]mito dynamics in control and Mrs2 KD cells measured with KMG-301. Treatment with FCCP (5 μM) triggered the [Mg2+]mito decrease in mitochondria (means ± SEM; black line, n = 46 for control; red line for n = 43 Mrs2 KD cells from 4 experiments). (i) Comparison of averaged amplitudes of [Mg2+]cyto increase between control and Mrs2 KD cells at 2–4 min (initial [Mg2+]cyto increase, left) and 6–8 min (late phase, right). Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 46 for control and n = 43 for Mrs2 KD cells from 4 experiments). (j) Comparison of averaged amplitudes of [Mg2+]mito decrease between control and Mrs2 KD cells at 2–3 min (initial [Mg2+]mito decrease) and 6–7 min (after mitochondrial re-uptake of Mg2+ released into cytosol). Data are represented as means ± SEM (n = 46 for control and n = 43 Mrs2 KD cells from 4 experiments).

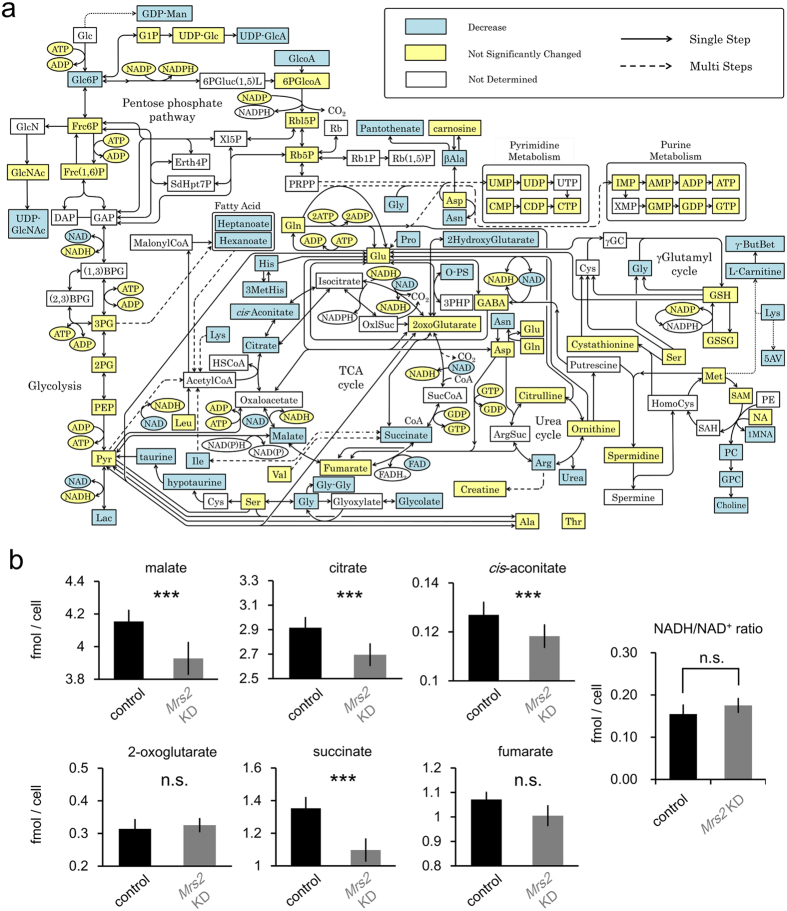

Suppression of TCA Cycle Induced by Disruption of Mitochondrial Mg2+ Homeostasis

To directly assess the effect of Mrs2 KD-induced homeostatic malfunction of mitochondrial Mg2+ on global metabolism and, in particular, mitochondrial energy generation, the metabolomics of Mrs2 KD and control cells were investigated using capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry (CE-MS) technique. CE-MS comprehensively quantify metabolites in biological samples37. We examined the differences in metabolite levels between control and Mrs2 KD cells. We quantitatively identified a total of 133 metabolites (control and Mrs2 KD samples, n = 6 respectively), and 24 metabolites were found to significantly differ between control and Mrs2 KD samples, which are overviewed in Fig. 3a (pathway information was obtained by reference to KEGG [http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html] and a previous report38). Especially, most metabolites of TCA cycle such as malate, citrate, cis-aconitate and succinate, were reduced in Mrs2 KD cells (Fig. 3b). These results suggest that dysregulation of mitochondrial Mg2+ homeostasis causes suppression of TCA cycle turnover in mitochondria. Despite suppression of TCA cycle activity, NADH/NAD+ was not affected in Mrs2 KD cells (Fig. 3b). No effect on product of TCA cycle suggests that the direct impact of Mrs2 KD is downstream of TCA cycle in mitochondrial energy production.

Figure 3. Metabolic alteration of Mrs2 KD cells.

(a) The Overview of alternation in metabolome between control and Mrs2 KD cells. Significance was determined by paired t-test (n = 6, p < 0.05). The significantly decreased metabolites in Mrs2 KD samples are shown in light blue boxes. All significantly changed metabolites are shown. Yellow Boxes indicate metabolites not significantly changed. (b) Comparison of metabolites in TCA cycles and NADH/NAD+ ratio comparing control and Mrs2 KD cells. Significance was determined by paired t-test (n = 6, p < 0.05).

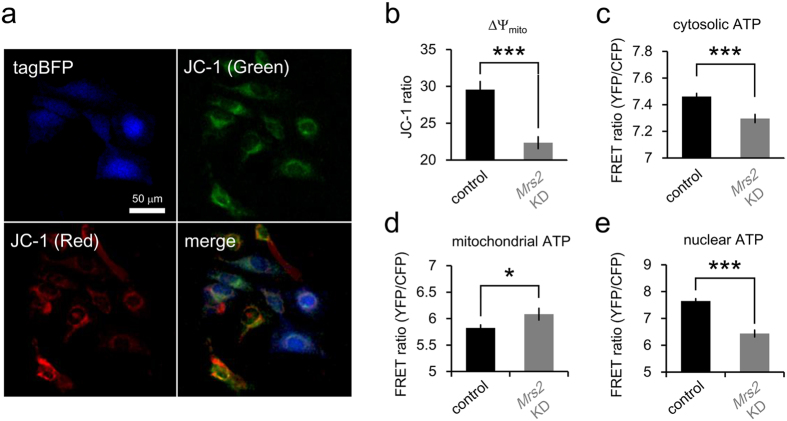

Mrs2 KD Disrupt the Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

Using electron released from NADH and FADH2 produced in TCA cycle, proton gradient is generated across mitochondrial inner membrane via electron-transport chain, which result in generation of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨ). To assess the ΔΨ, we quantified the ratio (red to green) of average mitochondrial fluorescence intensity of 5, 5′, 6, 6′-terachloro-1, 1′, 3, 3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1) per cells (Fig. 4a). In Mrs2 KD HeLa cells, the red-to-green ratio of JC-1 fluorescence, which indicates the mitochondrial inner membrane potential, was lower than control cells (Fig. 4b). This result suggests the mitochondrial Mg2+ uptake through MRS2 is crucial for maintaining the ΔΨ.

Figure 4. Comparison of ΔΨ and intracellular ATP level between control and Mrs2 KD cells.

(a) Representative fluorescent image of control and Mrs2 KD cells stained with ΔΨ indicator JC-1 (top right: green fluorescence; bottom left: red fluorescence; bottom right: merged image). Mrs2 KD cells were labeled with tagBFP (top left). (b) Comparative analysis of the green-to-red ratio of JC-1 signals (index of ΔΨ) revealed that Mrs2 KD decreases the ΔΨ (n = 955 and for control and n = 375 Mrs2 KD cells from 4 experiments). (c–e) Cytosolic (c), mitochondrial (d) and nucleic (e) ATP levels in control and Mrs2 KD cells were measured with genetically encoded ATP sensor ATeam. In Mrs2 KD cells, ATP level was decreased in cytosol (n = 1944 control cells from 8 experiments and n = 556 Mrs2 KD cells from 8 experiments) and nucleus (n = 621 control cells from 5 experiments and n = 119 Mrs2 KD cells from 5 experiments), and increased in mitochondrial (n = 388 control cells from 4 experiments and n = 126 Mrs2 KD cells from 4 experiments).

Mrs2 KD Disrupt the Energy Metabolism in Mitochondria

In mitochondria, ATP is made from ADP and phosphate by ATP synthase using an electrochemical gradient of protons across the mitochondrial inner membrane. Therefore, inside-negative ΔΨ across the mitochondrial inner membrane is crucial for maintaining the physiological function of the oxidative phosphorylation to generate ATP. To access the intracellular energy status, we performed live imaging of cells expressing ATeam, which is genetically-encoded fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based ATP indicator39. In cytosol and nucleus, the ATeam ratio, which indicates ATP level, were lower in Mrs2 KD cells than that in control cells (Fig. 4c,e). In contrast to the decrease in extra-mitochondrial ATP levels, in Mrs2 KD cells, ATP level increased in mitochondria (Fig. 4d) despite decrease of TCA cycle turnover (Fig. 3) and ΔΨm (Fig. 4a,b), suggesting that dysregulation of mitochondrial Mg2+ causes the imbalances of ATP exports from mitochondria.

Dysregulation of Mitochondrial Mg2+ Affect the Mitochondrial Morphology

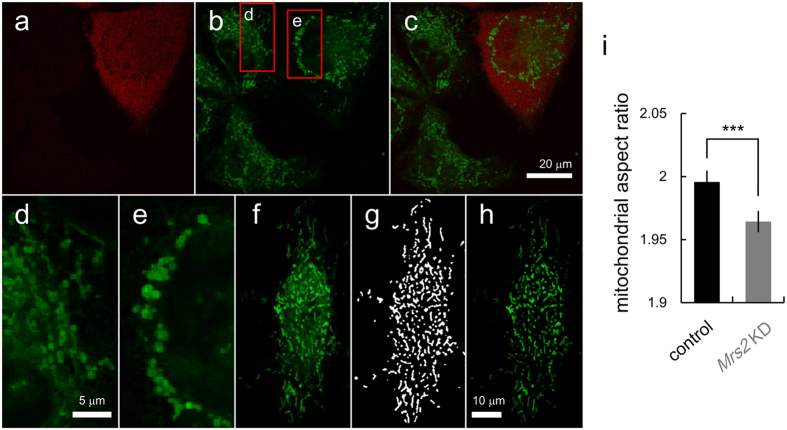

Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelle12,40,41, and their morphological changes regulate cellular metabolic processes and vice versa12. We assessed whether the malfunction of mitochondrial Mg2+ regulatory system affects mitochondrial morphology. To obtain the exact mitochondrial morphology, mitochondrion selective probe insensitive to ΔΨ, Mito Tracker Green FM, was loaded into both control and Mrs2 KD cells (Fig. 5b,c). To distinguish Mrs2 KD cells from control cells, Mrs2 miR expression vector coding tagBFP was used (Fig. 5a,c). Whereas the normal morphology of mitochondria in cells was tubular10 (Fig. 5d), the increased accumulation of rounding mitochondria was observed in Mrs2 KD cells (Fig. 5e). In stress condition, the abnormal accumulation of large swollen mitochondria is reported in previous studies42,43. To quantitatively analyze the morphological difference of mitochondria between in control and in Mrs2 KD cells, a morphological feature was evaluated by computer-assisted image processing. The acquired images (Fig. 5f) were processed to generate a mitochondria-specific binary image (Fig. 5g) allowing the quantification of mitochondrial shape (Fig. 5h) as previously described44. From quantitative morphological analysis of mitochondria, the aspect ratio (the ratio between the major and minor axes of the ellipse equivalent to the mitochondrial object) was calculated for each mitochondrion. The mitochondria in Mrs2 KD cells had lower aspect ratio than that in control cells (Fig. 5i), indicating that Mrs2 KD induced mitochondrial rounding.

Figure 5. Morphological analysis of mitochondria in control and Mrs2 KD cells.

(a) Mrs2 KD cells were labeled with tagBFP. (b) In control and Mrs2 KD cells, mitochondrial location and shape were visualized with MitoTracker Green FM. (c) The merged image was shown (green: mitochondria, red: Mrs2 KD cells). (d,e) The enlarged images of boxed area in panel b in control (d) and Mrs2 KD cells (e). (f) Representative image of mitochondria stained for digital image processing. (g) Binary image of mitochondria shown in panel (f). (h) Fluorescent image of mitochondria masked with mitochondrial binary image shown in panel g. (i) Comparison of aspect ratio (AR) of mitochondrial shape between in control and in Mrs2 KD cells. The AR of mitochondria in Mrs2 KD cells was smaller than that in control cells, suggesting the rounding of mitochondria (mean ± SEM; n = 20628 mitochondria in 109 cells for control and n = 20159 mitochondria in 84 cells from 8 experiments).

Cell Vulnerability to Cellular Stress enhanced by Mitochondrial Mg2+ dysregulation

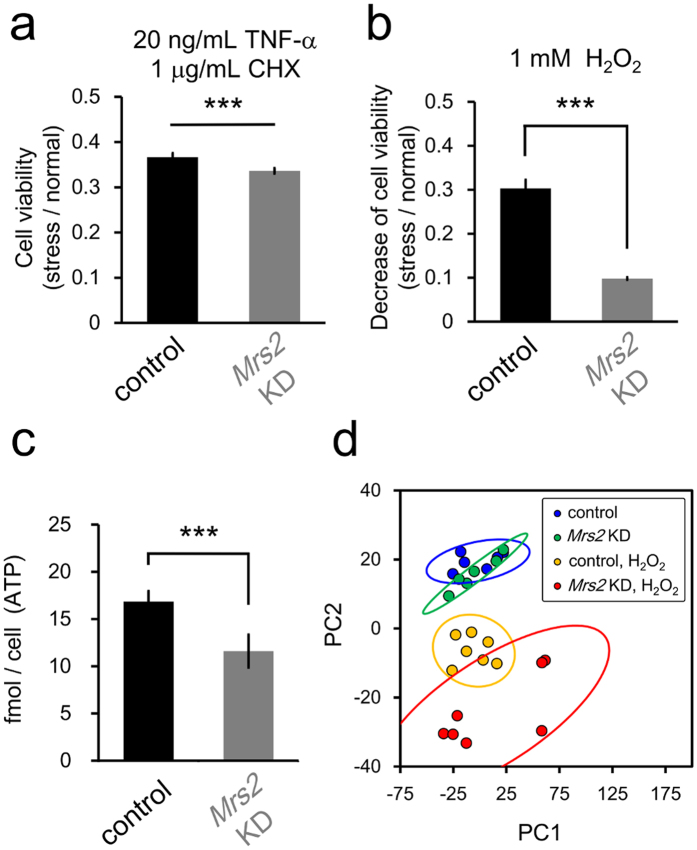

We revealed the dysregulation of mitochondrial Mg2+ results in the reduction of extra-mitochondrial ATP concentration. The negative effects of low ATP levels on cellular vulnerability are suggested45. To investigate the physiological effects of inaccessibility to Mg2+ induced energy imbalance on cellular vulnerability to stress, the viabilities were compared under cellular stress conditions between control and Mrs2 KD cells by MTT assay. In Mrs2 KD cells, cell viabilities were lower than in control cells in the condition of 20 ng/mL TNF-α and 1 μg/mL cycloheximide (CHX) (Fig. 6a) and also 1 mM H2O2 conditions (Fig. 6b), respectively. These results indicate that dysregulation of mitochondrial Mg2+ homeostasis causes increased susceptibility under cellular stress conditions. Metabolome analysis revealed that, under H2O2 condition, ATP level in Mrs2 KD cells was lower than that in control cells (Fig. 6c), suggesting Mrs2 KD-induced lower ATP level cause cellular vulnerability against oxidative stress. Next, to investigate the effects of mitochondrial Mg2+ dysregulation on cellular metabolome under stress condition, the overall impact of Mrs2 KD was compared using principal component analysis (PCA) for all detected 104 metabolites among 4 conditioned samples; control and Mrs2 KD cells with/without H2O2. PCA revealed that the clusters of control and Mrs2 KD cells under H2O2 condition were more separated than in normal condition, indicating that Mrs2 KD-induced defection of mitochondrial ATP synthesis had larger impacts under stress conditions (Fig. 6d).

Figure 6. Mrs2 KD induced increased vulnerability to cellular stress.

(a,b) Comparison of the cell viability under TNF-α/CHX- or H2O2-induced stress between in control and in Mrs2 KD cells. In Mrs2 KD cells, cell damage (decrease rate in cell viability) in the presence of H2O2 (a) or TNF-α/CHX (b) is more severe than that in control cells (n = 12 for the control and n = 12 for Mrs2 KD samples), indicating Mrs2 KD cells are more vulnerable to cellular stress. (c) Comparison of ATP level between control and Mrs2 KD cells under H2O2 condition by metabolome analysis (n = 6 for each sample). (d) Plot of samples under 4 conditions projected onto the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) identified PCA using all quantified 104 metabolites (n = 6 or 7 for each sample). Each circle indicates a single sample, while the larger ovals represent 95% confidence regions. Each color indicates 4 groups of conditions.

Discussion

We demonstrated that deficit of MRS2, which is a mitochondrial primary Mg2+ regulatory system, causes disruption of mitochondrial energy metabolism and cellular sensitization against cellular stress. First, we confirmed that Mrs2 KD causes malfunction of mitochondrial Mg2+ uptake (Fig. 2) and reduction of Mg2+ stored in mitochondria (Fig. 1). Second, we revealed that Mrs2 KD induces decreases in substrates of TCA cycle (Fig. 3), ΔΨ and extra-mitochondrial ATP levels (Fig. 4) in contrast increased mitochondrial ATP level (Fig. 4). In addition, we observed that mitochondria in Mrs2 KD cells have abnormal morphology (Fig. 5). Lastly, we showed that the effect of Mrs2 KD was noticeable under stress conditions, which sensitized cells to cellular stress (Fig. 6). These results indicate that mitochondrial Mg2+ regulate the cellular energy status, and it changes mitochondrial morphology and affects cell vulnerability against biological stress.

Physiological Significance of mitochondrial Mg2+ homeostasis

Although partial information has been accumulated about Mg2+-dependent regulation of energy metabolism, the comprehensive effects of mitochondrial Mg2+ on metabolic status in living cells have not been elucidated. As far as we know, this is the first work to demonstrate a series of relationships between Mg2+ regulatory system and cellular energy metabolism. In Mrs2 KD cells, in contrast to decreased substrates of TCA cycle (Fig. 3), collapse of ΔΨm and decreased extra-mitochondrial ATP levels (Fig. 4), mitochondrial ATP level are increased (Fig. 4). These results indicate the mitochondrial dis-accessibility to Mg2+ suppress ATP efflux from mitochondria, which is possibly mediated by ATP-Mg/Pi carrier6. Mitochondrial ATP accumulation inhibits many enzymatic processes in TCA cycle46 and electron transport chain activities5 in a negative feedback manner. Suppression of TCA cycle and electron transport chain activities would result in reduced ATP production in mitochondria. Consequently, mitochondrial Mg2+ regulates coupled reactions in mitochondrial energy metabolism, i.e. TCA cycle, electron transport chain and ADP/ATP translocation. In addition, morphological changes of mitochondria were also observed in Mrs2 KD cells (Fig. 5). Abnormal large and round mitochondria are also observed under pharmaceutically ATP synthesis-inhibited condition47. These are consistent with the idea that mitochondrial morphology is controlled by energy metabolism48. Abnormal mitochondrial morphology is associated with cancer11 obesity, type 2 diabetes12, and neurodegenerative disorders12,13,14. It may be explained by the idea that metabolic impairment induces cellular vulnerability45. Actually, sensitization against cellular stress by mitochondrial Mg2+ dysregulation was observed in Mrs2 KD cells (Fig. 6). In contrast, in a cellular model experiments of Parkinson’s disease, increase in [Mg2+]cyto, which probably links to [Mg2+]mito increase, protects cells from neurodegeneration by maintaining cellular ATP concentration and suppressing ROS production28. In summary, mitochondrial Mg2+ regulate the cellular metabolic process via shift of mitochondrial energy metabolism, and it changes mitochondrial morphology and affects the cell viability through changing stress susceptibility.

In normal cells, mitochondrial Mg2+ would play a role as a regulator of metabolic state under physiological condition. A wide variety of hormonal regulations of intracellular Mg2+ homeostasis has been reported49. In human, circadian rhythm for the serum Mg2+ level with the peak around noon are reported50, which is corresponding to circadian Mg2+ excretory rhythm with the peak at night51. In facts, a recent study revealed circadian rhythms in the intracellular [Mg2+] regulate cellular metabolism52. Because Mg2+ transport through MRS2 depends on extra-mitochondrial Mg2+ concentration53, mitochondrial Mg2+ homeostasis is also probably governed by circadian regulation. In addition, we recently demonstrated mitochondrial Mg2+ regulation mediated by second messenger pathways26. These studies support that cells dynamically regulate [Mg2+]mito in response to various signals and circadian rhythm under physiological condition. A respiration-dependent mitochondrial Mg2+ regulation54 is consistent with the coupling of [Mg2+]mito regulation with mitochondrial activities. Consequently, cells would modulate energy production and metabolic states via regulation of mitochondrial Mg2+ in response to environmental information.

Methods

HeLa cells culture

HeLa cells were seeded in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 50 U/mL penicillin and 50 mg/mL streptomycin (Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The cells were plated on glass-bottomed dishes (Iwaki, Tokyo, Japan), 100 mm cell culture dishes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), or 48 well dishes (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for fluorescence imaging, metabolomics analysis or MTT assay, respectively. The medium was changed in every other day.

Knockdown of Mrs2 in HeLa cells

For knockdown of Mrs2, BLOCK-iTTM Pol II miR RNAi Expression Vector Kits (Life technologies) was used. BLOCK-iT RNAi Designer from Life Technologies was used to design four single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides encoding the target pre-miRNA. These vectors are specifically designed to allow expression of miRNA sequences and contain specific miR flanking sequences that allow proper processing of the miRNA. Sequences of pre-miRNA insert in miRNA vectors for knockdown were designed as follow:

5′-GTAGCTACTGATTCCAAGAGTAGTTTTGGCCACTGACTGACTACTCTTGATCAGTAGCTA-3′ (Mrs2 KD #1),

5′-GAATGCTAGCTACTGATTCCAAGTTTTGGCCACTGACTGACTTGGAATCTAGCTAGCATT-3′ (Mrs2 KD #2),

5′-GTGAAGAATGCTAGCTACTGATGTTTTGGCCACTGACTGACATCAGTAGAGCATTCTTCA-3′ (Mrs2 KD #3), and

5′-GTTTGAAGAATGCTAGCTACTGGTTTTGGCCACTGACTGACCAGTAGCTCATTCTTCAAA-3′ (Mrs2 KD #4), respectively.

To identify the cells transfected with microRNA expression vector for Mrs2 knockdown, the sequence coding EmGFP or tagBFP were incorporated into the vectors. The miR RNAi vectors were transfected into cells 3 days prior to the experiments using Lipofectamine LTX (Life technologies) in the experiments except preparation for metabolome analysis.

Real time RT-PCR

To determine Mrs2 mRNA levels in miR transfected cells, total RNA from HeLa cells were isolated and purified by using the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN, Tokyo, Japan). Total RNA was reverse-transcripted using SuperScript VILO (Life technologies), and the generated cDNA was used as template for quantitative real time PCR amplification with SYBR GreenERTM (Life technologies). The Mrs2 mRNA levels were normalized to GAPDH signals as an internal standard. Quantitative real time PCR were performed using the following primers: Mrs2 forward 5′-CAGTTGTCTGGAGAGGGTCAA-3′, Mrs2 reverse 5′-AAGGATCAGTGGCTGCAAAA-3′, GAPDH forward 5′-CACCCACTCCTCCACCTTTG-3′ and GAPDH reverse 5′-CATGAGGTCCACCACCCTGT-3′.

Fluorescence imaging of the cytosolic or mitochondrial Mg2+ levels

For the quantification of cytosolic Mg2+ level in cells, HeLa cells were loaded with Mag-Fura-2-AM (Life technologies). For dye loading, HeLa cells were incubated in medium with 1 μM and 0.02% F-127 for 45 min at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The cells were gently washed twice with 1.0 mL of Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) at pH7.4 (adjusted with NaOH) that consisted of (in mM) 137 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.3 CaCl2, 0.5 MgCl2, 0.4 MgSO4, 0.3 Na2HPO4, 0.4 KH2PO4, 4.2 NaHCO3, 5.6 D-glucose, 5.0 HEPES. Then, further incubation was carried out for 15 min to allow for complete de-esterification of AM esters. For the measurement of the emitted fluorescence values at the excitation of 340 nm and 380 nm, a fluorescence microscope ECLIPSE TE300 (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a ×20 objective (S Fluor, Nikon) was used. A Xe lamp (150 W) with a monochromator unit was used for 340 nm and 380 nm excitation, and fluorescence was measured with a CCD camera (HiSCA, Hamamatsu Photonics, Shizuoka, Japan). The ratios of the fluorescence with excitation at 340 nm to that at 380 nm were calculated as an indicator of the cytosolic Mg2+ levels. For the detection of Mrs2 KD cells, emGFP was illuminated with the excitation at 488 nm. Region of interest (ROI) was located on the respective cell areas. In each ROI, spatial averaged ratios of the emitted fluorescence with excitation at 340 nm to that at 380 nm was calculated as an indicator of the Mg2+ levels.

For the quantification of mitochondrial Mg2+ level in cells using ratiometric Mg2+ indicator Mag-Fura-2, the cell permeabilization method using digitonin was performed as described previously36. Briefly, cells were stained with Mag-Fura-2 as described above. Cells loaded with Mag-Fura-2 were permeabilized with 20 μg/mL digitonin in intracellular-like medium (ICM; 120 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM KH2PO4, 20 mM HEPES-Tris at pH7.2 and 2 mM MgATP) buffer for 3 min, followed by washout of the released cytosolic Mag-Fura-2 with ICM. For the confirmation of mitochondrial localization and leakage from cytosol of Mag-Fura-2, fluorescence imaging was conducted with a confocal laser scanning microscope system (FluoViewFV1000; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) mounted on an inverted microscope (IX81; Olympus) equipped with a ×60 oil objective. For the measurements Mag-Fura-2 signals, the cells were illuminated with the excitation wavelength at 405 nm from diode laser, and the signals from Mag-Fura-2 and Mito Fluor Red were separated using a 560 nm dichroic mirror. The fluorescence images were obtained by detecting the signals at 500–550 nm for Mag-Fura-2 and at 570–670 nm for Mito Fluor Red, respectively. For the measurement of the emitted fluorescence values at the excitation of 340 nm and 380 nm, a fluorescence microscope ECLIPSE TE300 equipped with a ×20 objective (S Fluor) was used. The procedure of Mag-Fura-2 detection was mentioned above. A ROI is located on the all spotted area with strong intensities in each cell (Fig. 1D).

Real time imaging of cytosolic Mg2+ dynamics

For real time imaging of cytosolic Mg2+ dynamics, highly selective Mg2+ fluorescent dye KMG-104AM was used24. For loading KMG-104, cells were incubated with 5 μM KMG-104AM and 0.02% F-127 in pH adjusted HBSS for 30 min at 37 °C. Then, the cells were washed twice with HBSS and incubated in HBSS for 15 min at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 to allow for complete hydrolysis of the acetoxymethyl ester form. Fluorescence imaging was conducted with a confocal laser scanning microscope system, FV1000, equipped with a ×40 oil objective. For the measurements of KMG-104 signals, the cells loaded with KMG-104 were illuminated with the excitation wavelength at 488 nm from argon (Ar) laser. The fluorescence was obtained by detecting the signals at 500–600 nm. For the detection of tagBFP-labeled Mrs2 KD cells, the cells were illuminated with the excitation wavelength at 405 nm from diode laser, and its fluorescence was obtained by detecting the signals at 425–475 nm.

Real time imaging of mitochondrial Mg2+ dynamics

For real time imaging of mitochondrial Mg2+ dynamics, HeLa cells were stained with 20 μM highly selective mitochondrial Mg2+ fluorescent dye KMG-301AM in pH adjusted HBSS for 10 min on ice, so that hydrolysis of the acetoxymethyl ester by esterase present in the cytosol would be avoided22. Then, the cells were washed twice with HBSS and incubated in HBSS for 15 min at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 to allow for complete hydrolysis of the acetoxymethyl ester form in mitochondria. The detailed property and usage of KMG-301AM was described in our previous report22. Fluorescence imaging was conducted with a confocal laser scanning microscope, FV1000, equipped with a ×40 oil objective. The cells loaded with KMG-301 were illuminated with the excitation wavelength at 559 nm from diode laser, and its fluorescence was obtained by detecting signals at 570–670 nm. For the detection of tagBFP-labeled Mrs2 KD cells, the cells were illuminated with the excitation wavelength at 405 nm from diode laser, and its fluorescence was obtained by detecting the signals at 425–475 nm.

Fluorescence imaging of the intracellular ATP levels

For the quantification of intracellular ATP levels in living cells, ATeam1.0339 was transfected into HeLa cells using Lipofectamine LTX. The transfection was conducted the day before observation. Fluorescent imaging was conducted with a confocal laser scanning microscope system equipped with a ×20 air objective. For the measurements of ATeam signals, the cells were illuminated with the excitation wavelength at 440 nm from diode laser, and the signals from mseCFP and cp173-mVenus were separated using a 510 nm dichroic mirror and obtained at 480–510 nm for mseCFP and at 535–565 nm for cp173-Venus, respectively. The ratios of cp173-mVenus to mseCFP signals were calculated as an indicator of the cytosolic ATP levels.

Fluorescence imaging of the mitochondrial membrane potentials

For the quantification of mitochondrial membrane potential in living cells, HeLa cells were loaded with mitochondrial membrane potential sensitive dye 5, 5′, 6, 6′-terachloro-1, 1′, 3, 3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1; Life technologies). For dye loading, HeLa cells were incubated in pH adjusted HBSS with 10 μg/mL JC-1 for 15 min at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The cells were gently washed twice with 1.0 mL of HBSS. Fluorescent imaging was conducted with a confocal laser scanning microscope system, FV1000, equipped with a ×20 air objective. For the measurements of JC-1 signals, the cells were illuminated with the excitation wavelength at 488 nm from Ar laser, and the signals from JC-1 were separated using a 560 nm dichroic mirror and obtained by detecting the signals at 520–560 nm for green channel and at 575–620 nm for red channel, respectively. The ratio of signals from red channels to that from green channels was calculated as an indicator of the mitochondrial membrane potential. For the detection of tagBFP-labeled Mrs2 KD cells, the cells were illuminated with the excitation wavelength at 405 nm from diode laser, and its fluorescence images were obtained by detecting the signals at 425–475 nm.

Measurement of mitochondrial morphology

For assessment of mitochondrial morphology in living cells, mitochondria were stained with Mito Tracker Green FM and their morphology were quantified by handmade digital image processing software using MATLAB (MathWorks, Cambridge, UK). The algorithm for quantification of morphological feature is previously described44. Briefly, mitochondrial binary images were obtained from Mito Tracker Green FM-stained images, and aspect ratio of each mitochondrion was calculated as the ratio between the major and minor axes of the ellipse equivalent to the mitochondrial object.

Measurement of cell viability

For quantification of vulnerability against cellular stress, cell viabilities under the stress inducer H2O2- or TNFα/CHX-treated condition were measured using MTT assay. Control and Mrs2 KD cells were treated with H2O2 (1 mM) or TNFα (20 ng/mL) plus cycloheximide (CHX; 1 μg/mL) for 24 h. Then, the cells were incubated in the medium containing 0.5 mg/mL of MTT for 2 h at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Then, the medium was removed, and 100 μL of dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, nacalai tesque, Kyoto, Japan) was added in each well to dissolve the precipitation. The absorbance at 570 nm under stress condition (ABSstress) and normal condition (ABScontrol) were measured using a microplate reader (Fluoroskan Ascent FL, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell viability was defined as the ABSstress/ABScontrol.

Image analysis and statistics

The fluorescence was calculated as the mean intensity over a ROI on the cell body of each cell using the software package, FluoView (Olympus), Aquacosmos (Hamamatsu Photonics) or handmade software by MATLAB.

Metabolome analysis

The cells were transfected with a plasmid for Mrs2 knockdown by electroporation using Neon (Life Technologies). The cells were plated on a 100 mm dish, and grown for 3 days at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Culture medium was changed every day. Procedure for sample preparation of metabolome analysis was previously described37. Briefly, after washing cells twice with ice-cold 5% mannitol, metabolites were extracted by 1 mL ice-cold methanol containing internal standards (25 μM each of methionine sulfone (MetSul; Wako, Osaka, Japan), 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES; wako), D-Camphor-10-sulfonic acid (CSA; Wako). 400 μL of collected extracts were transferred into another tube, mixed with 400 μL chloroform and 200 μL Milli-Q water, and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 3 min at 4 °C. A 400 μL aliquot of the aqueous layer was centrifugally filtered through a 5 kDa cutoff membrane (UltrafreeMC-PLHCC for Metabolome Analysis; Human Metabolome Technologies, Yamagata, Japan) to remove proteins from samples, followed by the centrifugal-concentration at 42 °C. CE-MS experiments were performed using Agilent CE Capillary Electrophoresis System.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Yamanaka, R. et al. Mitochondrial Mg2+ homeostasis decides cellular energy metabolism and vulnerability to stress. Sci. Rep. 6, 30027; doi: 10.1038/srep30027 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. H. Imamura for the generous gift of intracellular ATP indicator ATeam 1.03. This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research, KAKENHI (24240045, 16H01751) and Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport, Science, and Technology, Japan (MEXT)-Supported Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities in 2014–2018 (S1411003).

Footnotes

Author Contributions R.Y., Y.S., K.H. and K.O. designed the research. R.Y. and S.T. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. K.S. designed and synthesized the compounds. R.Y., Y.S. and K.O. designed and wrote the paper. T.S. and K.O. supervised the project. All authors participated in the discussion of the data and in production of the final version of the manuscripts.

References

- de Baaij J. H., Hoenderop J. G. & Bindels R. J. Magnesium in man: implications for health and disease. Physiol Rev. 95, 1–46 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panov A. & Scarpa A. Mg2+ control of respiration in isolated rat liver mitochondria. Biochemistry 35, 12849–12856 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Zavala J. S. & Moreno-Sanchez R. Modulation of oxidative phosphorylation by Mg2+ in rat heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 273, 7850–7855 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn M. C., Achs M. J. & Garfinkel D. Computer simulation of metabolism in pyruvate-perfused rat heart. II. Krebs cycle. Am J Physiol. 237, R159–R166 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piskacek M., Zotova L., Zsurka G. & Schweyen R. J. Conditional knockdown of hMRS2 results in loss of mitochondrial Mg2+ uptake and cell death. J Cell Mol Med. 13, 693–700 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aprille J. R. Mechanism and regulation of the mitochondrial ATP-Mg/Pi carrier. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 25, 473–481 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinopoulos C. et al. A novel kinetic assay of mitochondrial ATP-ADP exchange rate mediated by the ANT. Biophys J. 96, 2490–2504 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf F. I., Trapani V. & Cittadini A. Magnesium and the control of cell proliferation: looking for a needle in a haystack. Magnes Res. 21, 83–91 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani A. M. Cellular magnesium homeostasis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 512, 1–23 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther T. Concentration, compartmentation and metabolic function of intracellular free Mg2+. Magnes Res. 19, 225–236 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alirol E. & Martinou J. C. Mitochondria and cancer: is there a morphological connection? Oncogene. 25, 4706–4716 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy M., Reddy P. H., Iijima M. & Sesaki H. Mitochondrial division and fusion in metabolism. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 33, 111–118 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann B. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in cell life and death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 11, 872–884 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y. & Lu B. Mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy in Parkinson’s disease: disordered cellular power plant becomes a big deal in a major movement disorder. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 21, 935–941 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F. Y. et al. Second messenger role for Mg2+ revealed by human T-cell immunodeficiency. Nature. 475, 471–476 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N. & Veillette A. Immunology: Magnesium in a signalling role. Nature. 475, 462–463 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandao K., Deason-Towne F., Perraud A. L. & Schmitz C. The role of Mg2+ in immune cells. Immunol Res. 55, 261–269 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaigne-Delalande B. & Lenardo M. J. Divalent cation signaling in immune cells. Trends Immunol. 35, 332–344 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin H. The logic of the Membrane, Magnesium, Mitosis (MMM) model for the regulation of animal cell proliferation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 458, 16–23 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y. et al. Design and synthesis of Mg2+-selective fluoroionophores based on a coumarin derivative and application for Mg2+ measurement in a living cell. Anal Chem. 74, 1423–1428 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota T. et al. Investigation of intracellular magnesium mobilization pathways I PC12 cells B simultaneous Mg-Ca fluorescent imaging. J Am Coll Nutr. 23, 742S–744S (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo Y. et al. Newly developed Mg2+-selective fluorescent probe enables visualization of Mg2+ dynamics in mitochondria. PLoS One. 6, e23684 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii T. et al. Design and synthesis of a FlAsH-type Mg2+ fluorescent probe for specific protein labeling. J Am Chem Soc. 136, 2374–2381 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu H. et al. Design and synthesis of highly sensitive and selective fluorescein-derived magnesium fluorescent probes and application to intracellular 3D Mg2+ imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 126, 16353–16360 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo Y., Fujimoto A., Hotta K., Suzuki K. & Oka K. Glutamate-induced calcium increase mediates magnesium release from mitochondria in rat hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci Res. 88, 3125–3132 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka R., Shindo Y., Hotta K., Suzuki K. & Oka K. NO/cGMP/PKG signaling pathway induces magnesium release mediated by mitoKATP channel opening in rat hippocampal neurons. FEBS Lett. 587, 2643–2648 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka R. et al. Neural depolarization triggers Mg2+ influx in rat hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 310, 731–741 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo Y., Yamanaka R., Suzuki K., Hotta K. & Oka K. Intracellular magnesium level determines cell viability in the MPP+ model of Parkinson’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1853, 3182–3191 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota T. et al. Mitochondria are intracellular magnesium stores: investigation by simultaneous fluorescent imagings in PC12 cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1744, 19–28 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Gruskos J., Afzal M. & Buccella D. Visualizing changes in mitochondrial Mg2+ during apoptosis with organelle-targeted triazole-based ratiometric fluorescent sensors. Chem Sci. 6, 6841–6846 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zsurka G., Gregan J. & Schweyen R. J. The human mitochondrial Mrs2 protein functionally substitutes for its yeast homologue, a candidate magnesium transporter. Genomics. 72, 158–168 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindl R., Weghuber J., Romanin C. & Schweyen R. J. Mrs2p forms a high conductance Mg2+ selective channel in mitochondria. Biophys J. 93, 3872–3883 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz C., Deason F. & Perraud A. L. Molecular components of vertebrate Mg2+-homeostasis regulation. Magnes Res. 20, 6–18 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quamme G. A. Molecular identification of ancient and modern mammalian magnesium transporters. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 298, C407–C429 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramoto T. et al. A mutation in the gene encoding mitochondrial Mg2+ channel MRS2 results in demyelination in the rat. PLoS Genet. 7, e1001262 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordas G. & Hajnoczky G. Plasticity of mitochondrial calcium signaling. J Biol Chem. 278, 42273–42282 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soga T. et al. Quantitative metabolome analysis using capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2, 488–494 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M., Ikeda S., Tashiro E., Soga T. & Imoto M. Metabolomic identification of the target of the filopodia protrusion inhibitor glucopiericidin A. Chem Biol. 17, 989–998 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura H. et al. Visualization of ATP levels inside single living cells with fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based genetically encoded indicators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 15651–15656 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner L. L. Determining the shape and cellular distribution of mitochondria: the integration of multiple activities. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 25, 471–476 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman J. R. & Nunnari J. Mitochondrial form and function. Nature. 505, 335–343 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einheber S., Bhat M. A. & Salzer J. L. Disrupted axo-glial junctions result in accumulation of abnormal mitochondria at nodes of ranvier. Neuron Glia Biol. 2, 165–174 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan D. F. et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science. 331, 456–461 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman W. J., Distelmaier F., Esseling J. J., Smeitink J. A. & Willems P. H. Computer-assisted live cell analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential, morphology and calcium handling. Methods. 46, 304–311 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. & Michaelis E. K. Selective neuronal vulnerability to oxidative stress in the brain. Front Aging Neurosci. 2, 12 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaNoue K. F., Bryla J. & Williamson J. R. Feedback interactions in the control of citric acid cycle activity in rat heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 247, 667–679 (1972). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard A. P. et al. Quantitative analysis of mitochondrial morphology and membrane potential in living cells using high-content imaging, machine learning, and morphological binning. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1853, 348–360 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youle R. J. & van der Bliek A. M. Mitochondrial fission, fusion, and stress. Science 337, 1062–1065 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani A. M. & Scarpa A. Regulation of cellular magnesium. Front Biosci. 5, D720–D734 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touitou Y., Touitou C., Bogdan A., Beck H. & Reinberg A. Serum magnesium circadian rhythm in human adults with respect to age, sex and mental status. Clin Chim Acta. 87, 35–41 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnen-Dechent W. & Ketteler M. Magnesium basics. Clin Kidney J. 5, i3–i14 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney K. A. et al. Daily magnesium fluxes regulate cellular timekeeping and energy balance. Nature (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolisek M. et al. Mrs2p is an essential component of the major electrophoretic Mg2+ influx system in mitochondria. Embo J. 22, 1235–1244 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung D. W., Panzeter E., Baysal K. & Brierley G. P. On the relationship between matrix free Mg2+ concentration and total Mg2+ in heart mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1320, 310–320 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.