Abstract

γ-Aminobutyric acid is a non-protein amino acid involved in various metabolic processes. The objectives of this study were to examine whether increased GABA could improve heat tolerance in cool-season creeping bentgrass through physiological analysis, and to determine major metabolic pathways regulated by GABA through metabolic profiling. Plants were pretreated with 0.5 mM GABA or water before exposed to non-stressed condition (21/19 °C) or heat stress (35/30 °C) in controlled growth chambers for 35 d. The growth and physiological analysis demonstrated that exogenous GABA application significantly improved heat tolerance of creeping bentgrass. Metabolic profiling found that exogenous application of GABA led to increases in accumulations of amino acids (glutamic acid, aspartic acid, alanine, threonine, serine, and valine), organic acids (aconitic acid, malic acid, succinic acid, oxalic acid, and threonic acid), sugars (sucrose, fructose, glucose, galactose, and maltose), and sugar alcohols (mannitol and myo-inositol). These findings suggest that GABA-induced heat tolerance in creeping bentgrass could involve the enhancement of photosynthesis and ascorbate-glutathione cycle, the maintenance of osmotic adjustment, and the increase in GABA shunt. The increased GABA shunt could be the supply of intermediates to feed the tricarboxylic acid cycle of respiration metabolism during a long-term heat stress, thereby maintaining metabolic homeostasis.

Heat stress induces a variety of negative effects on plant growth and development, and the damage may be further accentuated with the predictable increase of global temperature in the future1,2. It is imperative to improve heat tolerance for cool-season species growing in areas with prolonged periods of heat stress that lead to growth inhibition and even plant death3,4. Use of plant growth regulators or natural products of plants is found to be an effective approach to promote plant tolerance to various abiotic stresses, including heat stress. Recently, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), as an important non-protein amino acid, has been found to exhibit certain physiological functions involved in plant growth regulation and stress tolerance, such as maintenance of cytosolic pH, osmoregulation, and carbon and nitrogen metabolism5,6,7. Earlier studies also have demonstrated that GABA levels of plants rapidly increased when exposed to different environmental stresses6,8. Exogenous application of GABA could enhance chilling tolerance in peach fruits (Amygdalus persica)9, salt tolerance in Nicotiana sylvestris10, and drought tolerance in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne)11. In more recent reports, it is suggested that GABA is not just a metabolite and may act as a stress-induced intercellular signaling molecule related to the signal transduction pathway in plants12,13,14. However, plant adaptation to abiotic stresses is dependent on comprehensive responses associated with physiological and metabolic changes, and the role of GABA on heat stress mitigation still has not yet been fully elucidated.

Antioxidant defense, including enzymatic and non-enzymatic systems, is a fundamental detoxification system for plants to cope with oxidative damage induced by abiotic stress15,16. The ascorbate-glutathione (AsA-GSH) cycle involved in the redox reaction of AsA and GSH together with other antioxidant enzymes including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and peroxidase (POD) maintains the balance between generating and quenching of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in plant cells17. To some extent, antioxidant function determines the ability of plants to survive high temperature, as heat stress leads to massive ROS accumulation which damages to cell membranes and accelerates leaf senescence18,19. GABA-induced stress tolerance could be acquired by increased antioxidant ability in various plant species under different stress conditions, such as aluminium stress20, chilling21, and drought11,22. It has been reported that GABA exhibited a partial role of antioxidant protection due to increased antioxidant enzyme activity in leaves of rice (Oryza sativa) when exposed to short-term (10 d) high temperature (35/30 °C, day/night)23. However, how GABA may regulate enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant pathways during a long-term heat stress has not been well documented.

Many other metabolic processes also undergo changes in plants when suffered from abiotic stress24. The adjustment of metabolite accumulation plays critical roles in plant adaptation to stress25,26,27. It has been well documented that some low-molecular-weight metabolites, such as carbohydrates and amino acids are energy source, osmotic regulants, as well as signaling molecules during stress28,29,30. GABA shunt is testified to the close link to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle13,31. A recent study highlighted the predominant role of GABA on metabolism, which showed GABA supply maintained amino acid metabolism and nitrogen repartition in Arabidopsis under carbon- or nitrogen-limiting growth conditions32. Although several studies have suggested that GABA supplementation to animals is beneficial to acclimate high temperature33,34,35, limited research has been done on GABA-induced metabolic changes for plant adaptation to prolonged periods of heat stress in cool-season plant species. The metabolic pathways that link GABA to stress-related metabolites could provide further insight into functions of GABA in regulating heat tolerance of plants.

The objectives of this study were 1) to examine whether increased GABA could improve heat tolerance in cool-season creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera) through physiological analysis and 2) to determine major metabolic pathways regulated by GABA that contribute to the improved heat tolerance through metabolic profiling.

Results

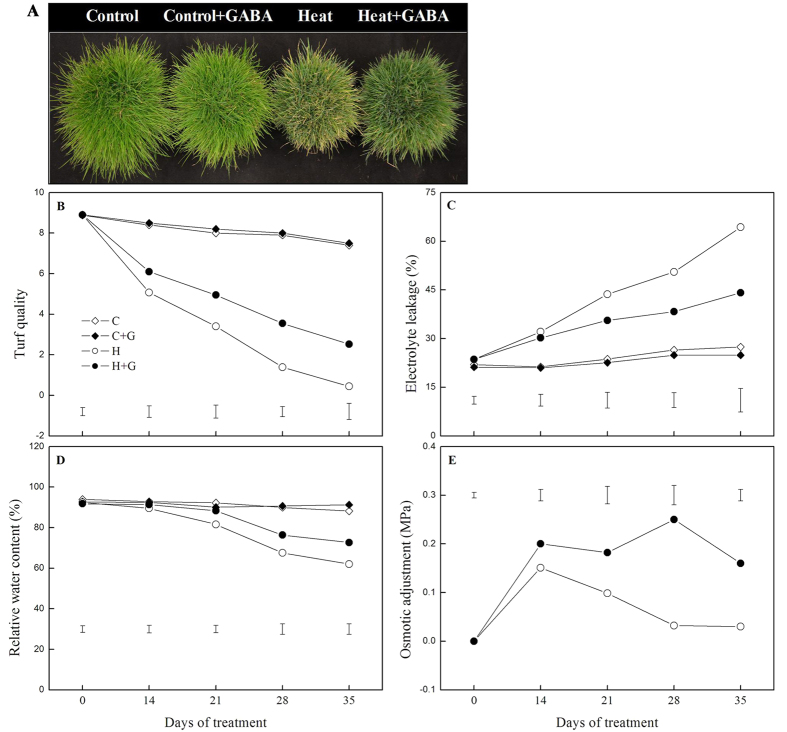

Effects of heat stress alone and with GABA on turf quality and water status

Under the non-stress condition, GABA had no significant effects on turf quality (TQ) and electrolyte leakage (EL) (Fig. 1A–C). Heat stress resulted in a significant decrease in TQ and increase in EL, but exogenous application of GABA alleviated heat-induced decline in TQ and increase in EL (Fig. 1B,C). GABA-treated plants maintained significantly higher relative water content (RWC) than untreated plants at 21, 28, and 35 d of heat stress (Fig. 1D). Leaf osmotic adjustment (OA) of both non- and GABA-treated plants increased after 14 d of heat stress and then declined in untreated plants with prolonged heat stress duration, while it was maintained at a higher level in GABA-treated plants during heat stress. GABA-treated plants showed more than 5 times higher OA than untreated plants from 28 to 35 d of heat stress (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1. The effects of GABA on leaf water deficit and membrane stability during 35 d of 21/19 or 35/30 °C condition.

(A) Phenotype at 35 d of treatment, (B) turf quality, (C) electrolyte leakage, (D) relative water content, and (E) osmotic adjustment. Vertical bars represent least significance difference (LSD) values at a given day of treatment (P = 0.05). C, control; C + G, control + GABA; H, heat; H + G, heat + GABA.

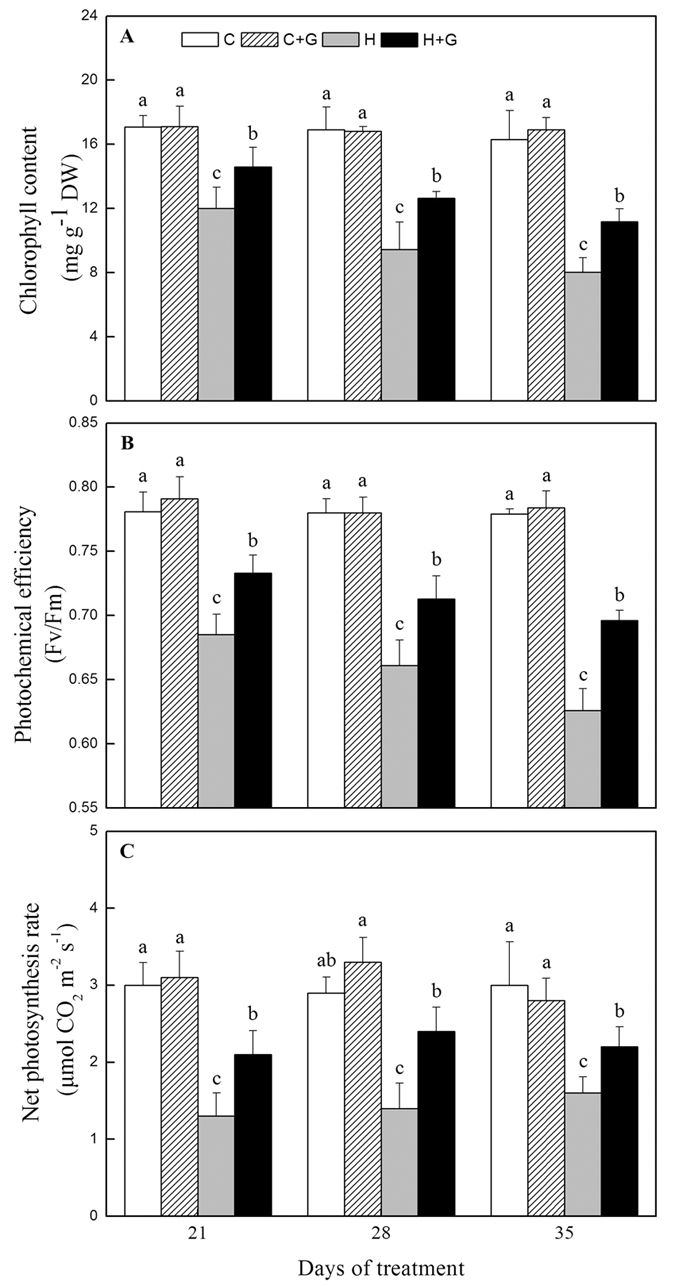

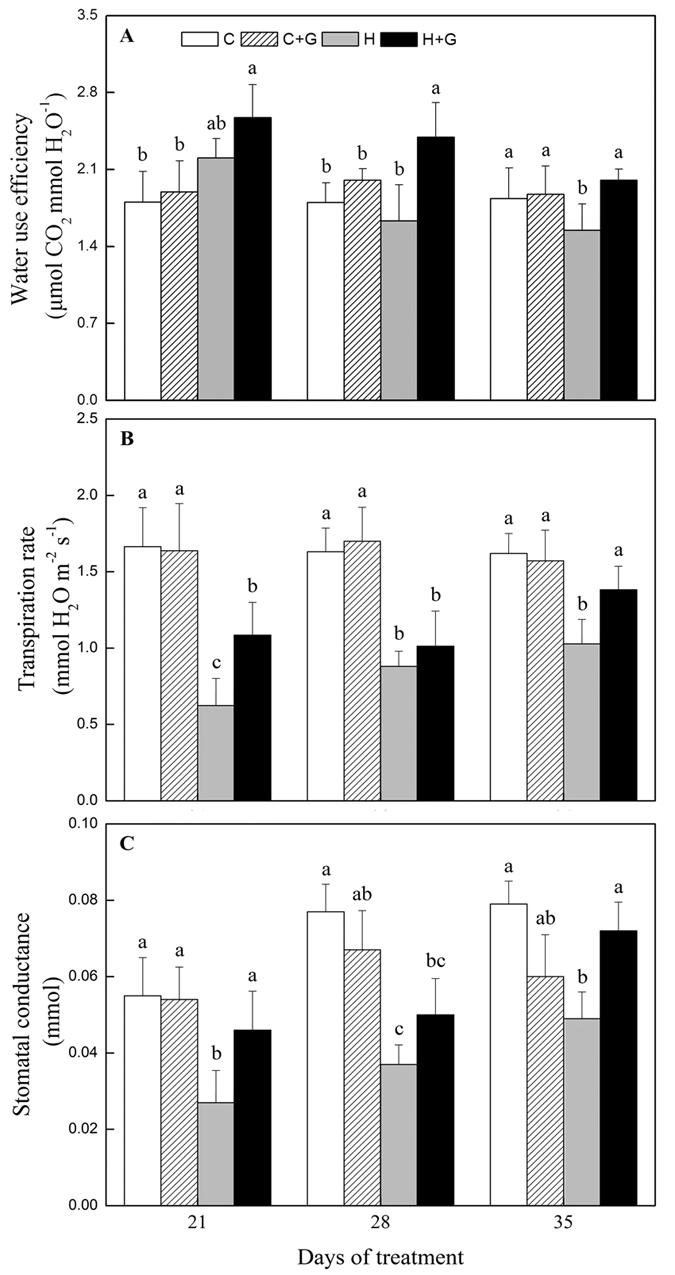

Effects of heat stress alone and with GABA on plant photosynthetic parameters and water use efficiency

Photosynthetic parameters were not significantly affected by exogenous GABA under well-watered condition (Fig. 2A–C). Heat stress led to the reduction in chlorophyll content (Chl) content and photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm) ratio, but with GABA application, Chl content and Fv/Fm were improved significantly from 21 to 35 d of heat stress (Fig. 2A,B). Net photosynthetic rate (Pn) declined significantly after 21 d of heat stress regardless of GABA treatment, but GABA application resulted in a 64% increase in Pn compared to untreated plants at 28 d of heat stress (Fig. 2C). Water use efficiency (WUE) calculated as the ratio of Pn/Tr was significantly higher in heat-stressed plants treated with GABA than that in heat-stressed plants without GABA at 28 and 35 d of heat stress (Fig. 3A). GABA-treated plants also maintained significantly higher transpiration rate (Tr) than untreated plants at 21 and 35 d of heat stress (Fig. 3B). As compared to non-stressed plants, heat-stressed plants without GABA application exhibited a significant reduction in stomatal conductance (gs) exposed to heat stress, while high temperature did not affect gs of these plants treated with GABA under the same stress condition (Fig. 3C).

Figure 2. The effects of GABA on photosynthesis during 35 d of 21/19 or 35/30 °C condition.

(A) Chlorophyll content; (B) Photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm); (C) Net photosynthesis rate. Vertical bars above columns indicate standard error of each mean. Different letters indicate significant difference for comparison at a given day of treatment (P = 0.05). C, control; C + G, control + GABA; H, heat; H + G, heat + GABA.

Figure 3. The effects of GABA on water use during 35 d of 21/19 or 35/30 °C condition.

(A) Water use efficiency; (B) Transpiration rate; (C) Stomatal conductance. Vertical bars above columns indicate standard error of each mean. Different letters indicate significant difference for comparison at a given day of treatment (P = 0.05). C, control; C + G, control + GABA; H, heat; H + G, heat + GABA.

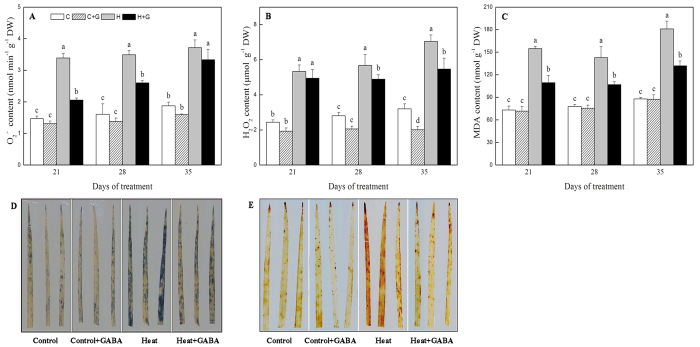

Effects of heat stress alone and with GABA on ROS production and antioxidant metabolism

The content of superoxide anion radical (O2·−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and malondialdehyde (MDA) gradually increased with prolonged heat stress regardless of GABA application (Fig. 4). Foliar spray of GABA had no significant effects on O2·−, H2O2, and MDA content under non-stress condition, except at 35 d when a 34% lower H2O2 content was found in GABA-treated plants (Fig. 4A–C). Exogenous application of GABA significantly decreased heat-induced O2·−, H2O2, and MDA accumulation in leaves. O2·− content was 39 and 26% lower in GABA-treated plants compared with non-treated plants at 21 and 28 d of heat stress. H2O2 content was 14 and 22% lower in GABA-treated plants compared with non-treated plants at 28 and 35 d of heat stress, respectively (Fig. 4A,B). From 21 to 35 d of heat stress, GABA-treated plants maintained 25% lower MDA content than untreated plants (Fig. 4C). O2·− staining at 28 d of treatments and H2O2 staining at 35 d of treatment also showed similar results. The lower density of blue spots which indicated the accumulation of O2·− and brown spots which indicated the accumulation of H2O2 were observed in GABA-treated leaves as compared to non-treated leaves under heat condition (Fig. 4D,E).

Figure 4. The effects of GABA on reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation during 35 d of 21/19 or 35/30 °C condition.

(A) Superoxide anion radical (O2·−) content, (B) hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content, (C) malondialdehyde (MDA) content, (D) O2·− staining at 28 d of treatment, and (E) H2O2 staining at 35 d of treatment. Vertical bars above columns indicate standard error of each mean. Different letters indicate significant difference for comparison at a given day of treatment (P = 0.05). C, control; C + G, control + GABA; H, heat; H + G, heat + GABA.

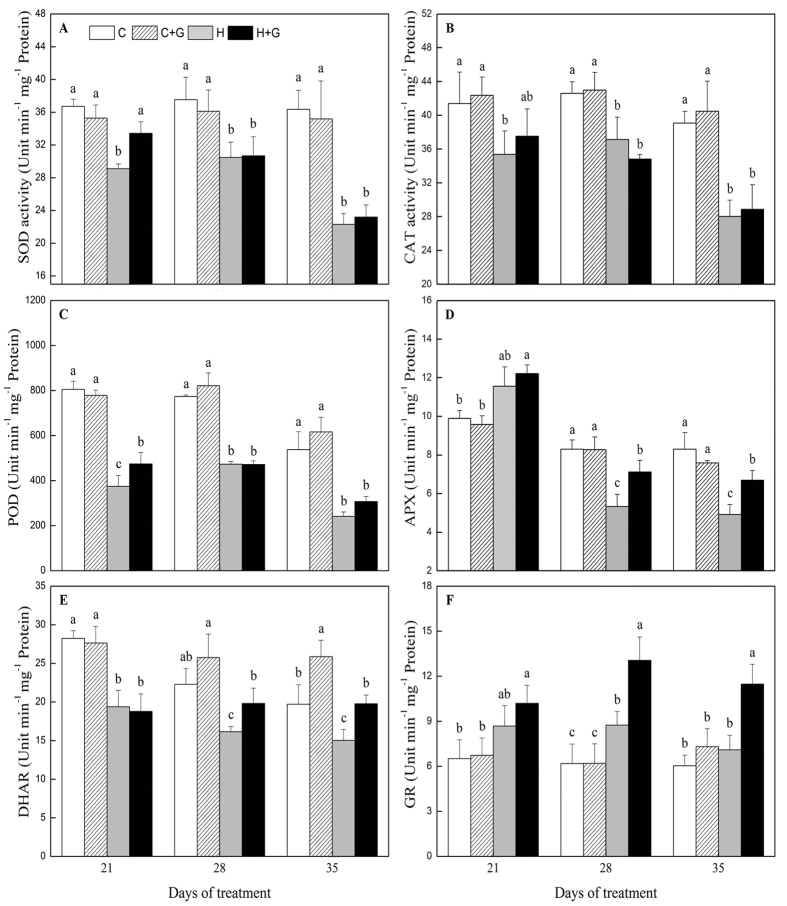

Heat stress caused decreases in SOD, CAT, and POD activities and an increase in APX activity. The activities of SOD, CAT, POD, and APX were not affected by exogenous GABA under non-stress condition (Fig. 5A–D). As demonstrated in Fig. 5B, GABA application also had no significant effect on CAT activity in heat-stressed plants. With application of GABA, plants showed 15 and 27% higher SOD and POD activity at 21 d of heat stress, respectively (Fig. 5A,C). Similarly, ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity increased by 33 and 36% in GABA-treated plants than that in untreated plants at 28 and 35 d of heat stress, respectively (Fig. 5D). Dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR) activity was enhanced in GABA-treated plants compared to untreated plants both under non-stressed and heat stress condition (Fig. 5E). GABA application had no significant effects on glutathione reductase (GR) activity under non-stressed condition, but GABA-treated plants showed 49 and 62% increases in GR activity relative to untreated plants when exposed to 28 and 35 d of heat stress (Fig. 5F).

Figure 5. The effects of GABA on antioxidant enzyme activities during 35 d of 21/19 or 35/30 °C condition.

(A) Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, (B) catalase (CAT) activity, (C) peroxide (POD) activity, and (D) ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity, (E) dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR) activity, (F) glutathione reductase (GR) activity. Vertical bars above columns indicate standard error of each mean. Different letters indicate significant difference for comparison at a given day of treatment (P = 0.05). C, control; C + G, control + GABA; H, heat; H + G, heat + GABA.

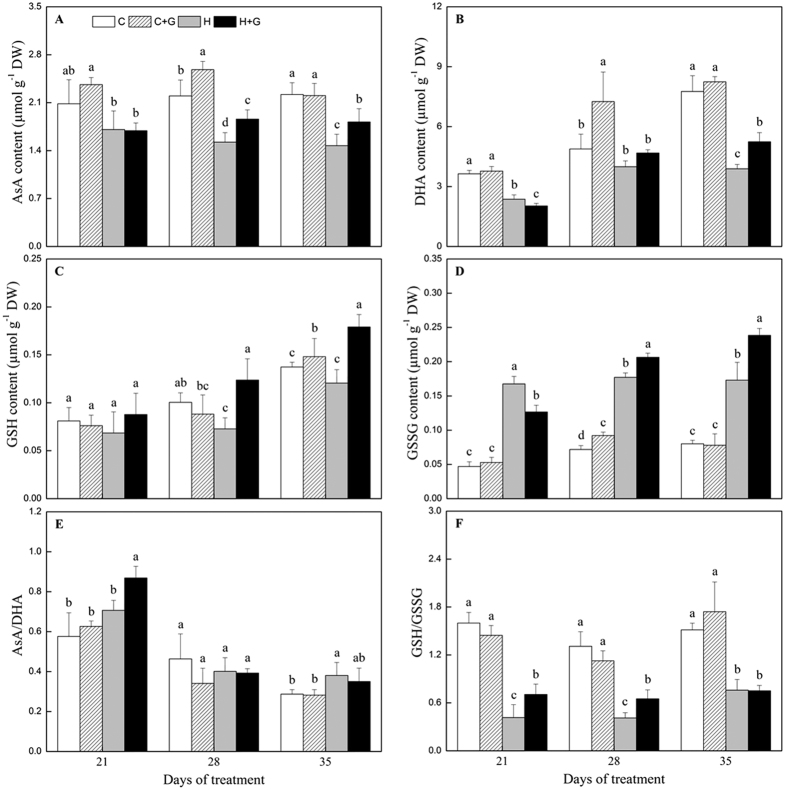

Heat stress reduced the content of ascorbic acid (AsA) and dehydroascorbic acid (DHA). However, with the application of GABA, plants showed significantly higher AsA content under both non-stress and heat stress conditions (Fig. 6A,B). In non-stressed plants treated with GABA, AsA and DHA content went up by 17 and 49%, respectively, over those plants without GABA at 28 d, and heat-stressed plants treated with GABA had 24 and 35% higher AsA and DHA content than heat alone at the last day of heat stress, respectively (Fig. 6A,B). In response to heat stress, reduced glutathione (GSH) and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) content gradually increased in leaves of creeping bentgrass (Fig. 6C,D). GSH and GSSG were found to increase by 1.4-fold in GABA-treated plants compared to non-treated plants at 35 d of heat stress (Fig. 6C,D). The AsA/GSH and GSH/GSSG ratio were not significantly different between non-treated and GABA-treated plants under non-stress condition, while heat-stressed plants treated with GABA exhibited significantly higher AsA/GSH at 21 d and GSH/GSSG at 21 and 28 d than heat-stressed plants without the application of GABA (Fig. 6E,F).

Figure 6. The effects of GABA on non–enzymatic antioxidants during 35 d of 21/19 or 35/30°C condition.

(A) reduced ascorbate (AsA), (B) dehydroascorbic acid (DHA), (C) reduced glutathione (GSH), (D) oxidized glutathione (GSSG), (E) AsA/DHA ratio, and (F) GSH/GSSG ratio. Vertical bars above columns indicate standard error of each mean. Different letters indicate significant difference for comparison at a given day of treatment (P = 0.05). C, control; C + G, control + GABA; H, heat; H + G, heat + GABA.

Metabolic profiling of metabolite changes in response to heat stress alone and with GABA

More than 300 peaks were detected by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS) and over 250 putative metabolites were found in leaves of creeping bentgrass. A total of 57 metabolites differentially accumulated in response to at 35 d of heat stress or with GABA treatment were identified and quantified in leaves of creeping bentgrass, mainly including 10 amino acids, 22 organic acids, 17 sugars, and 8 sugar alcohols, and the basic information of identified metabolites is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Derivitization, relative retention times, and mass to charge (m/z) ratios used for identification and quantification of the 57 metabolites identified in creeping bentgrass.

| No. | RT (min) | Metabolites | m/z | No. | RT (min) | Metabolites | m/z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.735 | Glycine | 58 | 30 | 16.201 | D–Psicofuranose | 245 |

| 2 | 6.758 | Lactic Acid | 117 | 31 | 16.445 | Shikimic acid | 204 |

| 3 | 6.996 | Glycolic acid | 147 | 32 | 16.555 | Citric acid | 233 |

| 4 | 7.170 | Pyruvic acid | 147 | 33 | 16.967 | Quininic acid | 73 |

| 5 | 7.402 | Alanine | 116 | 34 | 17.096 | Fructose | 103 |

| 6 | 7.962 | Oxalic acid | 220 | 35 | 17.321 | Galactose | 179 |

| 7 | 8.477 | Phosphoric acid | 211 | 36 | 17.366 | Glucose | 233 |

| 8 | 8.882 | Malonic acid | 233 | 37 | 17.565 | Talose | 233 |

| 9 | 9.056 | Valine | 144 | 38 | 17.701 | Mannitol | 205 |

| 10 | 9.655 | Serine | 132 | 39 | 18.531 | Gluconic acid | 205 |

| 11 | 9.867 | Glycerol | 103 | 40 | 18.898 | Palmitic Acid | 185 |

| 12 | 10.176 | Threonine | 130 | 41 | 19.284 | Myo–Inositol | 217 |

| 13 | 10.247 | Proline | 142 | 42 | 19.432 | Allose | 158 |

| 14 | 10.459 | Succinic acid | 147 | 43 | 19.735 | Cinnamic acid | 233 |

| 15 | 10.653 | Glyceric acid | 189 | 44 | 20.481 | Linolenic acid | 108 |

| 16 | 10.839 | Itaconic acid | 147 | 45 | 20.700 | Stearic acid | 185 |

| 17 | 12.468 | Erythrulose | 103 | 46 | 21.221 | Glyceryl–glycoside | 73 |

| 18 | 12.738 | Malic acid | 233 | 47 | 21.279 | Mannose | 211 |

| 19 | 13.137 | Aspartic acid | 233 | 48 | 21.672 | D–Glycero–D–gulo–Heptose | 185 |

| 20 | 13.182 | 5–Oxoproline | 156 | 49 | 21.724 | Galacturonic acid | 233 |

| 21 | 13.311 | GABA | 158 | 50 | 22.721 | Maltose | 204 |

| 22 | 13.600 | Threonic acid | 245 | 51 | 24.453 | Turanose | 233 |

| 23 | 14.347 | Glutamic acid | 128 | 52 | 25.502 | Cellobiose | 222 |

| 24 | 14.978 | Xylose | 233 | 53 | 26.506 | Galactinol | 204 |

| 25 | 15.306 | Levoglucosan | 204 | 54 | 27.607 | Dulcitol | 245 |

| 26 | 15.441 | Fucose | 233 | 55 | 27.825 | Gentiobiose | 204 |

| 27 | 15.821 | Aconitic acid | 211 | 56 | 30.799 | β–Sitosterol | 185 |

| 28 | 15.950 | Ribonic acid | 189 | 57 | 31.494 | Sucrose | 70 |

| 29 | 16.001 | Lyxofuranose | 233 |

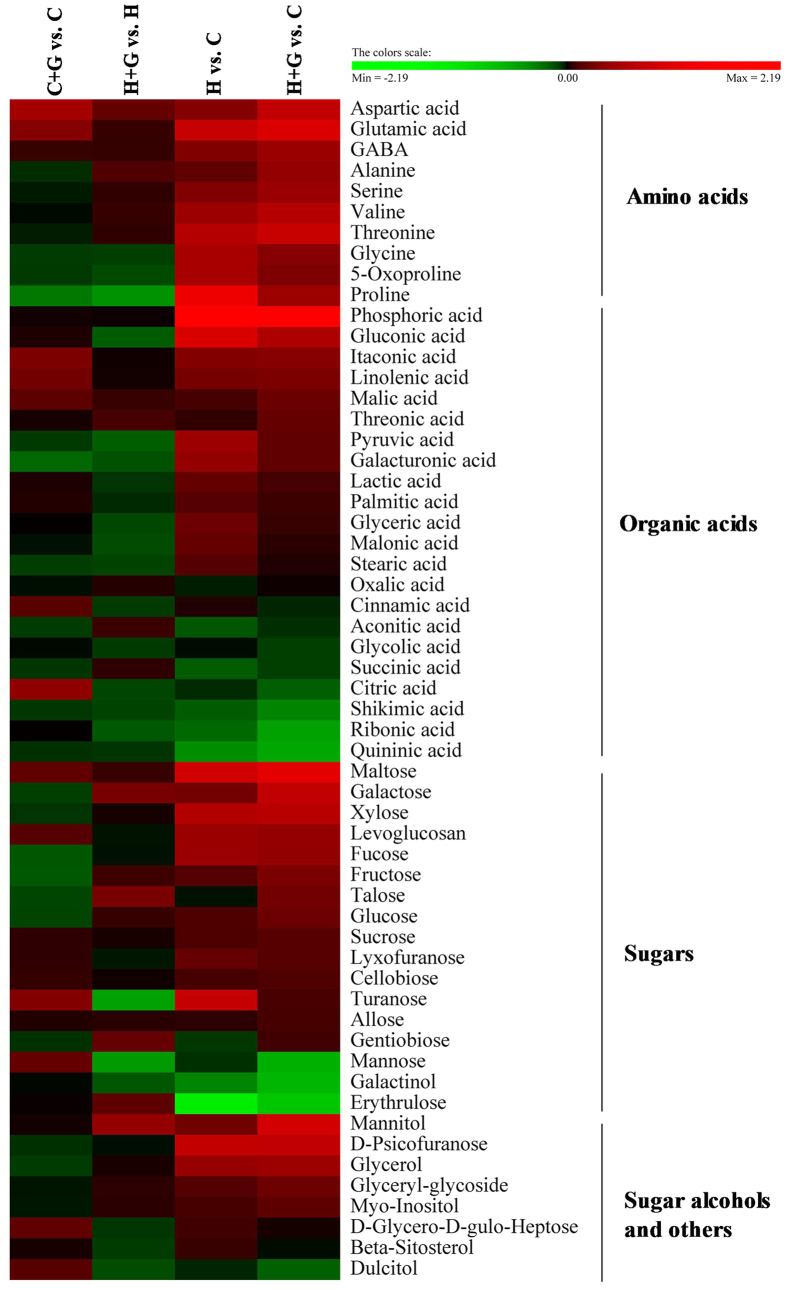

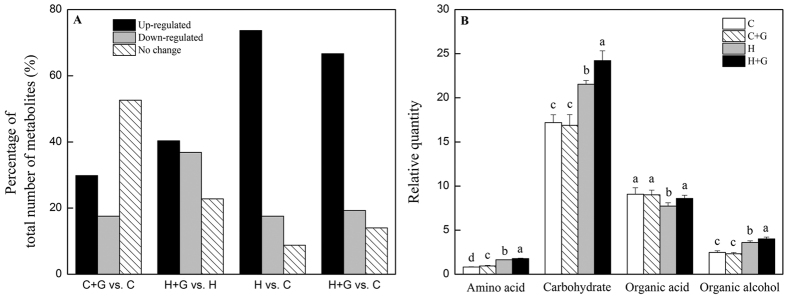

Heat map showed changes in the levels of 57 metabolites in response to exogenous application of GABA and heat stress (Fig. 7). In order to analyze metabolic pathways regulated by GABA and heat stress, the effects of GABA were investigated by comparing GABA treatment with untreated control under non-stress condition (C + G vs. C) and under heat stress (H + G vs. H), and metabolites were affected by heat stress through comparing heat stress treatments without or with GABA application with non-stress control (H vs. C and H + G vs. C). GABA application led to increases in the abundance of 17 metabolites and 23 metabolites, and decreases in the abundance of 10 metabolites and 21 metabolites under non-stress and heat stress, respectively. For both untreated and GABA-treated plants, heat stress led to increases in 23 metabolites and decreases in 3 metabolites (Fig. 8A). As shown in Fig. 8B, the total content of amino acids, carbohydrates, and organic alcohols significantly increased both in untreated and GABA-treated plants under heat stress, while total content of organic acids decreased under heat stress in GABA untreated plants, but increased in GABA-treated plants. GABA-treated plants exhibited 9, 12, 11, and 11% higher content of amino acids, carbohydrates, organic acids, and organic alcohols, respectively, than untreated plants under heat stress. Exogenous application of GABA had no significant effects on total content of carbohydrates, organic acids, and organic alcohols content, but enhanced accumulation of amino acids under non-stress conditions (Fig. 8B).

Figure 7. Heat map of changes in 57 metabolites levels in creeping bentgrass at 35 d in response to exogenous GABA application and heat stress.

The log2 fold change ratios are shown in the results. Red indicates an up–regulation, and green indicates a down–regulation. C + G vs. C and H + G vs. H implied the effects of exogenous GABA on metabolites under control or heat condition, respectively. H vs. C and H + G vs. C implied the effects of heat stress on metabolites without or with GABA application, respectively. C, control; C + G, control + GABA; H, heat; H + G, heat + GABA.

Figure 8.

Change to (A) the percentage of total number of metabolites (%), and (B) total relative amino acid, organic acid, sugar and sugar alcohol content at 35 d of treatment. Vertical bars above columns indicate standard error of each mean. Different letters indicate significant difference (P = 0.05). C, control; C + G, control + GABA; H, heat; H + G, heat + GABA.

The levels of key metabolites associated with heat tolerance and GABA were showed in Fig. 9. Heat stress caused significantly increases in 10 amino acids, and foliar application of GABA further improved the accumulation of 7 amino acids (GABA, glutamic acid, aspartic acid, alanine, threonine, serine, and valine) under heat stress. However, GABA-treated plants had significantly lower glycine, 5-oxoproline, and proline content than untreated plants under non-stress and heat stress conditions (Fig. 9A). For changes of organic acids, GABA-treated plants exhibited significantly higher aconitic, malic, citric, succinic, oxalic, and threonic acid under non-stress or heat condition and no significant differences in lactic, quinic, and shikimic acid were observed between GABA-treated and untreated plants under both temperature conditions, while gluconic, pyruvic, glyceric, and glycolic acid were down-regulated in GABA-treated plants compared to untreated plants under heat stress (Fig. 9B). The accumulation of 8 sugars (sucrose, fructose, glucose, allose, galactose, erythrulose, talose, and maltose) was enhanced by GABA application under heat stress except fucose, mannose, and turanose. In addition, exogenous GABA also resulted in significant increases in two sugar alcohols, mannitol and myo-inositol, under heat stress (Fig. 9C).

Figure 9.

Change to (A) relative amino acids, (B) organic acids, and (C) sugars and sugar alcohols content at 35 d of treatment. Vertical bars above columns indicate standard error of each mean. Different letters indicate significant difference (P = 0.05). C, control; C + G, control + GABA; H, heat; H + G, heat + GABA.

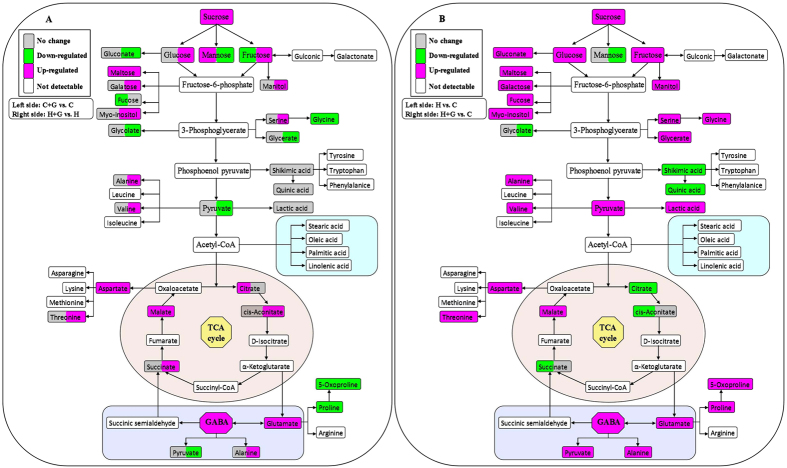

Metabolic pathways affected by GABA and heat stress

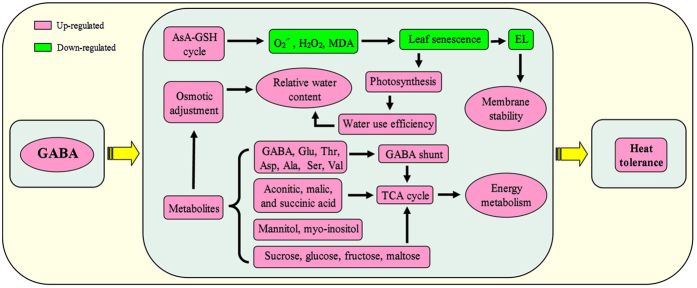

Figure 10 presented central pathways of biosynthetic metabolism involved in the GABA shunt, the TCA cycle and the primary metabolism. Out of 57 identified metabolites, 30 (10 amino acids, 11 organic acids, and 9 sugars and sugar alcohols) were assigned to these metabolic pathways. Increased endogenous GABA content induced by foliar application of GABA enhanced GABA shunt and TCA cycle both under non-stress control (C + G vs. C) and heat (H + G vs. H) conditions, while it resulted in a decrease in proline content (Fig. 10A). Under heat stress, GABA application caused increases in endogenous GABA content and the accumulation of glucose, fructose, maltose, sucrose, and most of amino acids. In contrast, gluconate, glycolate, glycerate, and pyruvate content declined (Fig. 10A). Figure 10B showed the effects of heat stress on metabolic pathways without (H vs. C) or with GABA application (H + G vs. C) as compared to non-stress control. Succinate and cis-aconitate decreased only in heat-stressed plants without GABA, but not in heat-stressed plants with GABA application, while mannose and glycolate only declined in heat-stressed plants treated with GABA (Fig. 10B). To summarize the results, a proposed model for GABA-induced heat tolerance in creeping bentgrass associated with physiological and metabolic changes was presented in Fig. 11. Increased endogenous GABA improved AsA-GAH cycle to decrease ROS (O2·− and H2O2) and MDA content associated with delaying leaf senescence and maintaining cell membrane stability. The enhancement of OA together with significantly increased WUE could contribute to the maintenance of RWC under heat condition. In addition, GABA-induced the accumulation of metabolites was involved in GABA shunt, amino acids, and sugar metabolism, which could be the supply of intermediates to feed the TCA cycle of respiration metabolism during a long-term heat stress, thereby maintaining metabolic homeostasis (Fig. 11).

Figure 10. Assignment of the 30 metabolites from 57 assayed metabolites to the metabolic pathway.

(A) The effects of increased GABA on metabolites under control or heat condition, and the color of left side each box means C + G vs. C, and the color of right side each box means H + G vs. H. (B) The effects of heat stress on metabolites without or with GABA application, and the color of left side each box means H vs. C, and the color of right side each box means H + G vs. C. C, control; C + G, control + GABA; H, heat; H + G, heat + GABA.

Figure 11. A proposed model for GABA–induced heat tolerance in creeping bentgrass associated with physiological and metabolic changes.

Red indicates an up–regulation, green indicates a down–regulation.

Discussion

Heat stress damages include accelerated leaf senescence associated with loss of chlorophyll and membrane stability and inhibition of growth and photosynthesis, as well as the induction of oxidative stress, as found in creeping bentgrass in this study and other plants species36,37,38. Our current findings showed that exogenous application of GABA effectively alleviated these heat stress damages in creeping bentgrass. Delayed leaf senescence (increased Chl content and Fv/Fm) could contribute to the increased Pn due to GABA application in leaves of creeping bentgrass. Similarly, increases in Chl content and photosynthesis by GABA application have been observed in other plant species exposed to hypoxia stress39. Heat stress also may cause water deficit in plants due to imbalanced water loss and water uptake40,41. Plants treated with GABA also exhibited improvement in OA and retained higher RWC, supporting the role of GABA in regulating plant water relations. In addition, higher transpiration was in conjunction with greater Pn leading to significant improved WUE in GABA-treated plants during heat stress. The physiological analysis suggested that GABA could alleviate heat damages in photosynthesis by suppressing leaf senescence and balancing water relations through improving osmotic adjustment and WUE.

GABA-induced stress tolerance could also involve changes in antioxidant enzyme activities associated with mitigation of oxidative injury20,21,42. Nayyar et al.23 reported that exogenous GABA resulted in increases in SOD, CAT, APX, and GR activities in rice seedlings after a relative short-term (10 d) heat stress (35/30 °C, day/night), indicating its protective role in scavenging heat-induced ROS. In this study, under prolonged periods (28 d) of heat stress (35/30 °C, day/night), GABA enhanced the activity of several key enzymes involved in AsA-GSH cycle and the accumulation of nonenzymatic antioxidants (AsA and GSH) while it had no significant effects on activating SOD, CAT and POD. As a result, ROS level and lipid peroxidation were found to decline notably in GABA-treated plants under heat stress. Our results suggested that the ability of GABA-treated plants to alleviate oxidative damages might be mainly the result of activation of both enzymatic and nonenzymatic metabolism in the AsA-GSH cycle during prolonged periods of heat stress, which along with the alleviation of heat-damages in photosynthesis and enhancement of efficient water relations, as well the maintenance of osmotic adjustment, conferring GABA-induced heat tolerance in creeping bentgrass.

The maintenance of metabolic balance and the accumulation of specific metabolites associated with increased endogenous GABA could be associated with the positive effects of GABA on heat tolerance. Carbohydrates are among the most abundant metabolites in plants, which play essential roles in plant tolerance to abiotic stresses, such as serving as energy source, osmoregulants, and signaling molecules43,44. Sugar alcohols, such as mannitol and myo-inositol, exhibit roles in signal transduction and scavengers of ROS against abiotic stress45,46,47. Increased carbohydrate accumulation has been associated with enhanced heat tolerance48,49. GABA application resulted in significant increases in the content of most of sugars identified in this study as well as sugar alcohols, implying the GABA-induced accumulation of carbohydrates could be related to enhanced Pn and osmotic adjustment among various other critical functions imparting heat tolerance.

Amino acids are another important primary metabolites in plants, which also serve as osmolytes as well as precursors for synthesis of proteins and secondary metabolites for stress defense50. Jespersen et al.51 found that exogenous nitrogen stimulated the accumulation of 6 amino acids in leaves of creeping bentgrass associated with enhanced heat tolerance. In the current study, the application of exogenous GABA resulted in increases of 7 amino acids (GABA, glutamic acid, aspartic acid, threonine, serine, alanine, and valine) of total 10 identified amino acids, suggesting the supply of GABA could be critically important for amino acid metabolism under heat conditions. GABA and glutamic acid which can transform from each other directly both serve as nitrogen resource13,32. Furthermore, glutamic acid was also involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis52,53. Increased aspartic acid, as an important precursor for many other amino acids, has been found to link to nitrogen metabolism and delayed leaf senescence under heat stress48,51,54. Threonine synthesis and catabolism could maintain isoleucine needs of plants, which had key functions on regulation of jasmonic acid signaling and heat shock response55,56,57. Melatonin-improved multiple abiotic stresses tolerance and CaCl2-induced cold tolerance both were associated with significantly up-regulated alanine and valine in bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon) through the analysis of metabolome58,59. Arabidopsis mutant shmt1 with a loss-of-function serine hydroxymetyltransferase was more susceptible to high light intensity and salt stress than wild type implying the importance of serine accumulation on stress tolerance60. Thus, all of the accumulation of these amino acids could contribute to GABA-induced heat tolerance via involvement in the supply of metabolic adjustment, antioxidants, OA, and other stress defense functions.

It has been well documented that glycine is the precursor of glutathione synthesis61. Interestingly, glycine, 5-oxoproline, and proline declined with GABA application under heat stress. Thus, significant down-regulated glycine content could be due to be transferred to synthesis of glutathione for antioxidant defense, since significantly increased glutathione was observed in GABA-treated plants as compared to untreated plants under heat stress. Proline is known as a stress-related amino acid, and its level varies with the severity of stress and the level of stress tolerance of plant species62,63. Excess accumulation of proline could attenuate heat tolerance in Arabidopsis seedlings64. The study of Du et al.48 implied that higher increases in proline content reflected the greater damages in bermudagrass and Kentucky bluegrass during early period of heat stress. The lower proline content of GABA-treated plants could reflect lesser heat-induced damages in creeping bentgrass. Additionally, based on the analysis of metabolic pathways, increased GABA shunt could be the supply of pyruvate and succinic semialdehyde to feed the TCA cycle instead of going to proline metabolism.

The multiplicity of organic acids result in the complexity of their functions involved in regulation of pH, stress defense, energy metabolism and detoxifcation in response to different environmental stresses65,66. Heat-caused decrease in total organic acids content was observed in GABA-untreated creeping bentgrass, while GABA-treated plants could maintain organic acids at a normal level. The result suggested that improved GABA alleviated heat-induced the deficiency of organic acids. Many organic acids are involved in TCA cycle which is most critical process of energy metabolism to drive ATP synthesis and biosynthesis in plants67. Generally, heat stress enhanced respiration to activate energy metabolism which may deplete intermediates of TCA cycle pool49,68,69. Increased GABA metabolism may stimulate organic metabolism in the TCA cycle of respiration, such as aconitate, succinate, and malate, since these metabolites were maintained to a greater extent in GABA-treated plants as compared to that in untreated plants under heat stress. In addition, oxalic acid played an important role in low-temperature response because of the increase in antioxidant potential in pomegranate (Punica granatum) and mango (Mangifera indica)70,71. Exogenous oxalic acid alleviated heat stress in alfalfa (Medicago sativa) through activation of antioxidant enzymes72. The finding of Merewitz et al.73 indicated that cytokinin-regulated drought tolerance could be correlated with an accumulation of oxalic acid in creeping bentgrass. Increased oxalic acid induced by GABA was observed in our study, suggesting GABA-regulated heat tolerance may also involve oxalic acid accumulation.

In summary, physiological and metabolic analyses of plants treated with GABA under non-stress and heat stress conditions demonstrated that GABA could improve heat tolerance through regulating multiple physiological processes and metabolic pathways, including the improvement of antioxidant metabolism, inhibition of leaf senescence, balance of photosynthesis and transpiration, and enhancement of osmotic adjustment, as well as the accumulation of amino acids, carbohydrates, organic acids and alcohols. The enhanced carbohydrate metabolism, amino biosynthesis, GABA shunt and TCA cycle could play important roles for GABA-induced heat tolerance. These results highlight the beneficial roles of GABA in heat responses. Future research will focus on the role of GABA as stress signaling molecules on differential expression of genes and proteins controlling those aforementioned metabolic pathways.

Methods

Plant material and treatment

Creeping bentgrass (cv. Penncross) sods were collected from Horticultural Farm II at Rutgers University, North Brunswick, NJ. The sod pieces were planted in polyvinyl chloride tubes (30 cm length, and 10 cm diameter) filled with fritted clay in a greenhouse for two months (September–October, 2014). The greenhouse had average day/night temperatures of 23/16 °C and 790 mmol m−2 s−1 photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) with natural sunlight and supplemental sodium lights when lack of natural sunlight. Plants were fertilized weekly with half-strength Hoagland’s nutrient solution74 and trimmed twice a week to maintain a canopy height of approximately 4 cm. Plants were transferred to controlled growth chambers after 2-month establishment in the greenhouse. The growth chambers were controlled at day/night temperatures of 21/19 °C, 70% relative humidity, and 12-h photoperiod at PAR of 660 mmol m−2 s−1 at the canopy level. Plants were maintained in those conditions for 7 d to allow plant acclimation to the growth chamber conditions prior to the imposition of heat treatment.

For the GABA treatment, all plants were sprayed three times at two-day intervals before exposed to heat stress with equal volume of 0.5 mM GABA solution or water (non-GABA treated control), and the duration of pretreatment was 5 d. The concentration of GABA was chosen based on a preliminary test with a range of concentrations (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 mM) for the most effective concentration on phenotypic changes. GABA-treated plants or non GABA-treated control plants were then subjected to the following four treatments in growth chambers for 35 d: 1) Non-stress control: plants were irrigated every two days to maintain soil water content at the pot capacity and maintained at 21/19 °C (day/night); 2) Non-stress control treated with GABA; 3) Heat stress: plants were exposed to 35/30 °C (day/night) conditions; and 4) Heat stress treated with GABA. Thus, the experiment had four treatments, and each treatment had four replicates. The experiment design was a split-plot design with temperature as the main plot and GABA treatments as the sub-plot. Each temperature treatment (21/19 °C or 35/30 °C, day/night) was replicated in four growth chambers (a total of eight chambers), and one pot (replicate) of GABA-treated and non-treated plants were placed in each growth chambers set at 21/19 °C or 35/30 °C.

Physiological analysis

TQ was evaluated based on color, density, and uniformity of the grass using a scale of 1 to 9; 9 being fully turgid, dense green canopy, 6 being minimal acceptable level, and 1 being completely desiccated and brown plants75. Leaf EL was calculated as the percentage of Cinitial/Cmax76. After washing three times with deionized water, 0.1 g fresh leaves were immersed in 35 mL of deionized water and shaken for 24 h to measure initial conductivity (Cinitial) using a conductivity meter (YSI Model 32, Yellow Spring, OH). Leaves then were autoclaved at 120 °C for 20 min and the conductance of the solution was measured as maximum conductance (Cmax). Leaf RWC was calculated using the formula RWC (%) = [(FW–DW)/(TW–DW)] × 10077. Fresh leaves were collected form plants and immediately weighed for fresh weight (FW), and then leaves were immerged in distilled water for 12 h at 4 °C. Turgid leaves were gently wiped dry and weighed for turgid weight (TW). Leaves then dried at 80 °C for 72 h to get a dry weight (DW). For determination of OA, fresh leaf tissues were submerged in deionized water for 8 h at 4 °C to fully hydrate leaves. Tissues were blotted dry and frozen in liquid nitrogen for further analysis. Following thawing in ice bath, leaves were ground with a micropestle to extract leaf sap and 10 mL sap was inserted into an osmometer (Wescor, Inc., Logan, UT) to determine osmolality (mmol kg−1). According to the formula osmotic potential = ([osmolality] [0.001][2.58]), osmolality was converted to osmotic potential. OA was then calculated as the difference in osmotic potential at full turgor between stressed leaves and well-watered control leaves78.

For leaf Chl content analysis, fresh leaves (0.1 g) were immerged in 10 mL of dimethyl sulphoxide in the dark for 48 h, and then the leaf extract was measured at 663 nm and 645 nm with a spectrophotometer (Spectronic in Instruments, Rochester, NY, USA). The formula described in Arnon79 was used for calculating chlorophyll content. For measurement of Fv/Fm, A layer of leaves were adapted to darkness for 30 min using leaf clips, and the Fv/Fm ratio was recorded with the fluorescence meter (Fim 1500; Dynamax, Houston, TX, USA). Three measurements of Fv/Fm ratio were taken per replicate at each sampling day. Pn, Tr, and gs of 10 individual leaves per replicate per treatment were measured using a photosynthetic apparatus (Li-Cor 6400, Li-Cor, Inc., Lincoln, NE). WUE was calculated following the formula: WUE = Pn/Tr. For the above measurements, leaves were placed in the leaf chamber, which provided 400 μl L−1 CO2 and 800 μmol photon m−2 red and blue light. Leaf samples were then cut from plants and scanned with Magic WandTM Portable Scanner (PDS-ST415-VPS, VuPoint Solutions) to measure leaf area which was used to calculate Pn, Tr, and gs.

The measurement of ROS and MDA content

For the measurement of generation of O2·−, 0.1 g leaves were ground with 1.5 ml 65 mM PBS (pH 7.8) and then centrifuged at 10000 g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected. The reaction mixture containing supernatant (0.5 ml), PBS (0.5 ml), and 10 mM hydrochloride (0.1 ml) was incubated at water bath (25 °C) for 20 min. A 2 ml mixed solution (58 mM sulfanilamide and 7 mM α-naphthylamine) was added into reaction mixture for another 20 min at 25 °C water bath and then the reaction was extracted with 2 ml chloroform and the absorbance was measured at 530 nm80. The H2O2 was assayed according to potassium iodide method81. Briefly, 0.1 g leaves were homogenized with 5 ml 0.1% TCA and centrifuged at 12000 g for 20 min. 0.5 ml 10 mM potassium phosphate and 1 ml 1 M KI were added to 0.5 ml of supernatant. The absorbancy of reaction was recorded at 390 nm. To analyze MDA, 0.2 g leaves was ground on ice with 2 ml of 50 mM cold phosphate buffer saline (PBS) (pH 7.8). The homogenate was centrifuged at 12000 g for 30 min at 4 °C. A 0.5 ml supernatant and 1.0 ml reaction solution (20% w/v trichloroacetic acid and 0.5% w/v thiobarbituric acid) were added to the pellet and incubated at 95 °C for 15 min, and then cooled quickly in cool water. The reaction solution was centrifuged at 8000 g for 10 min. The absorbance of the reaction solution was measured at 532 and 600 nm. The concentration of MDA was calculated according to the formula described by Dhindsa et al.82. For determination of O2·− or H2O2 staining, leaves were stained with 2 mM nitrobluetetrozolium (NBT) in 20 mM PBS (pH 6.8) for 12 h or 0.1% (w/v) 3-diaminobenzinidine (DAB, pH 3.8) for 24 h, respectively, and then decolorated with ethanol and rinsed with deionized water83,84.

The analysis of antioxidant enzyme activity and content of non-enzymatic antioxidants

The supernatant, which was collected from MDA extraction, was further used for the assay of antioxidant enzyme activity. For SOD activity, 0.05 ml enzyme extract was mixed with 1.45 ml reaction solution (1.1 ml of 50 mM PBS, 100 μ of 195 mM methionine, 150 μl of 60 μM riboflavin, and 100 μl of 1.125 mM NBT), and the change of absorbance was recorded at 560 nm85. The activities of POD and CAT were determined by using the methods of Chance and Maehly86. For the assay of POD, 0.05 ml H2O2 (0.75%), 0.5 ml guaiacol solution (0.25%) and 0.995 ml PBS (100 mM, pH 5.0) were added in 0.05 ml enzyme extract, and then the mixture was gently shaken. For the assay of CAT, 0.5 ml H2O2 (45 mM) and 1 ml PBS (50 mM, pH 7.0) were mixed with 0.05 ml enzyme extract. The absorbance changes of reaction solution were monitored at 460 or 240 nm every 10 seconds for 6 times for POD or CAT, respectively. For measurement of APX activity, 0.05 ml of enzyme extract was added into 1.5 ml of reaction solution containing 10 mM AsA, 5 mM H2O2, 0.003 mM EDTA, and 100 mM PBS (pH 5.8) and the change of absorbance was recorded every 10 seconds for 6 times at 290 nm87. DHAR and GR activities were determined according to the method of Cakmak et al.88 and the changes in absorbance were monitored at 340 nm for GR or 265 nm for DHAR every 10 seconds for 1 min. Protein content was determined using Bradford’s89 method.

AsA, DHA, GSH and GSSG content were measured using the method of Gossett et al.90. After homogenization of 0.2 g of leaves in 3 ml 5% phosphoric acid, the sample was centrifuged at 12000 g for 15 min. Total ascorbate was determined in a reaction mixture consisting of 100 μl supernatant, 250 μl 150 mM KPO4 buffer (pH 7.4) containing 5 mM EDTA and 50 μl 10 mM DTT. AsA was measured in a similar reaction mixture but the DTT was replaced by an equal amount of H2O. The further reaction was developed in both mixtures above by the addition of the following reagents: 200 μl 10% TCA, 200 μl 44% phosphoric acid, 200 μl α, α′-dipyridyl, and 100 μl FeCl3 and the mixtures were incubated at 40 °C for 40 min. The absorbency of reaction solution was read at 525 nm. The concentration of DHA was estimated from the difference of total ascorbate and AsA. For determination of glutathione, 0.2 g leaf tissues were ground in 3 ml of 6% phosphoric acid (pH 2.8). The homogenate was centrifugated at 12000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. Total glutathione was measured in a reaction mixture consisting of 200 μl extract, 200 μl reagent solution A (110 mM Na2PO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 15 mM EDTA, 0.3 mM 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid)), and 160 μl reagent B (1 mM EDTA, 50 mM imidazole, and 1.5 units GR activity). 80 μl of NADPH was added to start the reaction. The change in absorbance was monitored at 412 nm. For GSSG, 200 μl extract was incubated at 25 °C for 1 h with 40 μl 2-vinylpyridine before measurement according to the method mentioned above. Similarly, GSH was estimated as the difference between total glutathione and GSSG.

Metabolite extraction, separation, and quantification

The extraction procedure of metabolites was conducted according to methods of Roessner et al.91 and Rizhsky et al.92. Leaf samples were collected form 35 d of treatments and lyophilized in a FreeZone 4.5 system (Labconco, Kansas City, MO) until consistent weight. The lyophilized samples were then ground to a fine powder. Leaf tissue powder (20 mg) was transferred into a 10 ml centrifuge tube, and extracted in 1.4 ml of 80% (v/v) aqueous methanol at 200 rpm for 2 h. A 10 μl ribitol solution (2 mg ml−1) was added to tube as an internal standard prior to incubation. The samples were incubated in a water bath at 70 °C for 15 min. After centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 30 min, the supernatant was pipetted into new tube, and then 1.4 ml of water and 0.75 ml of chloroform were added in tube. The mixture was thoroughly vortexed and centrifuged for 5 min at 5000 rpm. 2 ml of the polar phase (methanol/water) was decanted into 1.5 ml HPLC vials and dried in a centrivap benchtop centrifugal concentrator (Labconco, Kansas City, MO). The dried polar phase was methoximated with 80 μl of methoxyamine hydrochloride (20 mg ml−1) at 30 °C for 90 min and was trimethylsilylated with 80 μl N-methyl-N-(trimethylsily)trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) including 1% trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS) for 60 min at 70 °C.

The analysis procedure of GC-MS was followed by the method of Qiu et al.93. The extracts were analyzed with a PerkinElmer gas chromatograph coupled with a TurboMass-Autosystem XL mass spectrometer (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MS). Equal extract (1 μl) was injected into a DB-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Agilent J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA). The inlet temperature was maintained at 260 °C. Initial GC oven temperature was set at 80 °C after a 5 min solvent delay; the GC oven temperature was raised to 280 °C with 5 °C min−1 after injection for 2 min, and finally held at 280 °C for 15 min. For the injection temperature, it was set to 280 °C, and then the ion source temperature was adjusted to 200 °C. Helium was used as the carrier gas with a constant flow rate set at 1 ml min−1. The measurements were made with electron impact ionization (70 eV) in the full scan mode (m/z 30–550). The metabolites were identified by using TURBOMASS 4.1.1 software (PerkinElmer Inc.) coupled with commercially available compound libraries: NIST 2005 (PerkinElmer Inc.,Waltham, MS), Wiley 7.0 (John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Hoboken, NJ).

Statistical analysis

The general linear model procedure for the analysis of variance (SAS 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to determine the significance of main treatment effects and interaction of GABA and heat stress for all measured parameters. The significance of differences was tested using Fisher’s protected least significance test (LSD) with p = 0.05 at a given day of stress treatment.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Li, Z. et al. Metabolic pathways regulated by γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) contributing to heat tolerance in creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera). Sci. Rep. 6, 30338; doi: 10.1038/srep30338 (2016).

Footnotes

Author Contributions Designed the studies: B.H. Undertook the experimental work: Z.L. and J.Y. Analysed the data: Z.L. and J.Y. Contributed to figure and manuscript preparation: Z.L., B.H. and Y.P.

References

- Hansen J. et al. Global temperature change. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 14288–14293 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahid A., Gelani S., Ashrafa M. & Foolad M. R. Heat tolerance in plants: an overview. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 199–223 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Blum A., Klueva N. & Nguyen H. T. Wheat cellular thermotolerance is related to yield under heat stress. Euphytica 117, 117–123 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Fry J. & Huang B. R. Applied turfgrass science and physiology (John Wiley & Sons, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- Shelp B. J., Bown A. W. & McLean M. D. Metabolism and functions of γ–aminobutyric acid. Trends Plant Sci. 41, 446–452 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnersley A. M. & Turano F. J. Gamma aminobutyric (GABA) and plant responses to stress. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 19, 479–509 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa J. M., Singh N. K., Cherry J. H. & Locy R. D. Nitrate uptake and utilization is modulated by exogenous γ–aminobutyric acid in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 48, 443–450 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S. Q. et al. Effects of exogenous GABA on gene expression of Caragana intermedia roots under NaCl stress: regulatory roles for H2O2 and ethylene production. Plant Cell Environ. 33, 149–162 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang H. T., Cao S. F., Yang Z. F., Cai Y. T. & Zheng Y. H. Effect of exogenous γ–aminobutyric acid treatment on proline accumulation and chilling injury in peach fruit after long–term cold storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 1264–1268 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akçay N., Bor M., Karabudak T., Özdemir F. & Türkan İ. Contribution of gamma amino butyric acid (GABA) to salt stress responses of Nicotiana sylvestris CMSII mutant and wild type plants. J. Plant Physiol. 169, 452–458 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan S., Laskowski K., Shukla V. & Merewitz E. B. Mitigation of drought stress damage by exogenous application of non–protein amino acid γ–aminobutyric acid on perennial ryegrass. J. Amer. Hort. Sci. 138, 358–366 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Kinnersley A. M. & Lin F. Receptor modifiers indicate that 4–aminobutyric acid (GABA) is a potential modulator of ion transport in plants. Plant Growth Regul. 32, 65–76 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Bouché N. & Fromm H. GABA in plants: just a metabolite? Trends Plant Sci. 9, 110–115 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G. H. et al. Exogenous γ–aminobutyric acid (GABA) affects pollen tube growth via modulating putative Ca2+–permeable membrane channels and is coupled to negative regulation on glutamate decarboxylase. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 3235–3248 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman M., Hossain M. A., da Silva J. A. T. & Fujita M. Plant response and tolerance to abiotic oxidative stress: antioxidant defense is a key factor in Crop stress and its management: perspectives and strategies (eds Venkateswarlu B. et al.) 261–315 (Springer: Netherlands, , 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Li J. G., Shen M. C., Zhang C. L. & Dong Y. H. Cold plasma treatment enhances oilseed rape seed germination under drought stress. Sci. Rep. 5, 13033 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Liu Y. & Zhang J. Advances in the research on the AsA–GSH cycle in horticultural crops. Front Agric. China 4, 84–90 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Xu S., Li J., Zhang X., Wei H. & Cui L. Effects of heat acclimation pretreatment on changes of membrane lipid peroxidation, antioxidant metabolites, and ultrastructure of chloroplasts in two cool–season turfgrass species under heat stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 56, 274–285 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Sgobba A., Paradiso A., Dipierro S., De Gara L. & de Pinto M. C. Changes in antioxidants are critical in determining cell responses to short– and long–term heat stress. Physiol. Plant. 153, 68–78 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H., Xu X., Wang H., Wang H. & Tao Y. Exogenous γ–aminobutyric acid alleviates oxidative damage caused by aluminium and proton stresses on barley seedlings. J. Sci. Food Agr. 90, 1410–1416 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A., Cao S., Yang Z., Cai Y. & Zheng Y. γ–Aminobutyric acid treatment reduces chilling injury and activates the defence response of peach fruit. Food Chem. 129, 1619–1622 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumari K. & Puthur J. T. γ–Aminobutyric acid (GABA) priming enhances the osmotic stress tolerance in Piper nigrum Linn. plants subjected to PEG–induced stress. Plant Growth Regul. 78, 57–67 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Nayyar H., Kaur R., Kaur S. & Singh R. γ–aminobutyric acid (GABA) imparts partial protection from heat stress injury to rice seedlings by improving leaf turgor and upregulating osmoprotectants and antioxidants. J. Plant Growth Regul. 33, 408–419 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Akula R. & Ravishankar G. A. Influence of abiotic stress signals on secondary metabolites in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 6, 1720–1731 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kind T., Scholz M. & Fiehn O. How large is the metabolome? A critical analysis of data exchange practices in chemistry. Plos One 4, e5440 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargallo-Garriga A. et al. Opposite metabolic responses of shoots and roots to drought. Sci. Rep. 4, 6829 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaubitz U., Erban A., Kopka J., Hincha D. K. & Zuther E. High night temperature strongly impacts TCA cycle, amino acid and polyamine biosynthetic pathways in rice in a sensitivity–dependent manner. J. Exp. Bot. erv352, doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv352 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey P. H. Organic osmolytes as compatible, metabolic and counteracting cytoprotectants in high osmolarity and other stresses. J. Exp. Bot. 208, 2819–2830 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulaev V., Cortes D., Miller G. & Mittler R. Metabolomics for plant stress response. Physiol. Plant. 132, 199–208 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wind J., Smeekens S. & Hanson J. Sucrose: metabolite and signaling molecule. Phytochemistry 71, 1610–1614 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fait A., Fromm H., Walter D., Galili G. & Fernie A. R. Highway or byway: the metabolic role of the GABA shunt in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 13, 14–19 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batushansky A. et al. Combined transcriptomics and metabolomics of Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings exposed to exogenous GABA suggest its role in plants is predominantly metabolic. Mol. Plant 7, 1065–1068 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Chen L. X., Fan Z. Y. & Wu Y. S. Effects of gamma–aminobutyric acid on performance of lactating sows during heat weather. Anim. Husbandry Feed Sci. 1, 16–17 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Tang J., Sun Y. Q. & Xie J. Protective effect of γ–aminobutyric acid on antioxidation function in intestinal mucosa of Wenchang chicken induced by heat stress. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 23, 1634–1641 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J. B. et al. Effects of rumen–protected γ–aminobutyric acid on performance and nutrient digestibility in heat–stressed dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 97, 5599–5607 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camejo D. et al. High temperature effects on photosynthetic activity of two tomato cultivars with different heat susceptibility. J. Plant Physiol. 162, 281–289 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veerasamy M., He Y. L. & Huang B. R. Leaf senescence and protein metabolism in creeping bentgrass exposed to heat stress and treated with cytokinins. J. Amer. Sco. Hort. Sci. 132, 467–472 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Soliman W. S., Fujimori M., Tase K. & Sugiyama S. I. Oxidative stress and physiological damage under prolonged heat stress in C3 grass Lolium perenne. Grassland Sci. 57, 101–106 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Xia Q. P., Gao H. B. & Li J. R. Effects of gamma–aminobutyric acid on the photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of muskmelon seedlings under hypoxia stress. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 4, 999–1006 (2011). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y. W. & Huang B. R. Osmotic adjustment and root growth associated with drought preconditioning–enhanced heat tolerance in kentucky bluegrass. Crop Sci. 41, 1168–1173 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez M., Canales E. & Borrás-Hidalgo O. Molecular aspects of abiotic stress in plants. Biotechnol. Appl. 22, 1–10 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Kuruvilla K. P., Nandhu M. S., Paul J. & Paulose C. S. Oxidative stress mediated neuronal damage in the corpus striatum of 6–hydroxydopamine lesioned Parkinson’s rats: Neuroprotection by Serotonin, GABA and Bone Marrow Cells Supplementation. J. Neurol. Sci. 331, 31–37 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheen J., Zhou L. & Jang J. C. Sugars as signaling molecules. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2, 410–418 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan F. et al. Exploring the temperature–stress metabolome of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 136, 4159–4168 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnoff N. & Cumbes Q. J. Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of compatible solutes. Phytochemistry 28, 1057–1060 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Patra B., Ray S., Richter A. & Majumder A. L. Enhanced salt tolerance of transgenic tobacco plants by co–expression of PcINO1 and McIMT1 is accompanied by increased level of myo–inositol and methylated inositol. Protoplasma 245, 143–152 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillaspy G. E. The cellular language of myo–inositol signaling. New Phytol. 192, 823–839 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H., Wang Z., Yu W., Liu Y. & Huang B. Differential metabolic responses of perennial grass Cynodon transvaalensis × Cynodon dactylon (C4) and Poa Pratensis (C3) to heat stress. Physiol. Plant. 141, 251–264 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Yu J. & Huang B. Elevated CO2–mitigation of high temperature stress associated with maintenance of positive carbon balance and carbohydrate accumulation in kentucky bluegrass. Plos One 9, e89725 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Less H. & Galili G. Principal transcriptional programs regulating plant amino acid metabolism in response to abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol. 147, 316–330 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jespersen D., Yu J. & Huang B. Metabolite responses to exogenous application of nitrogen, cytokinin, and ethylene inhibitors in relation to heat–induced senescence in creeping bentgrass. Plos One 10, e0123744 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beale S. I., Gough S. P. & Granick S. Biosynthesis of alpha–aminolevulinic acid from the intact carbon skeleton of glutamic acid in greening barley. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 72, 2719–2723 (1975). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg M. B. & Ferraris J. D. Intracellular organic osmolytes: function and regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7309–7313 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good A. G. & Zaplachinski S. T. The effects of drought stress on free amino acid accumulation and protein synthesis in Brassica napus. Physiol. Plant 90, 9–14 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- VanBogelen R. A., Kelley P. M. & Neidhardt F. C. Differential induction of heat shock, SOS, and oxidation stress regulons and accumulation of nucleotides in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 169, 26–32 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staswick P. E. & Tiryaki I. The oxylipin signal jasmonic acid is activated by an enzyme that conjugates it to isoleucine in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16, 2117–2127 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi V., Joung J. G., Fei Z. & Jander G. Interdependence of threonine, methionine and isoleucine metabolism in plants: accumulation and transcriptional regulation under abiotic stress. Amino Acids 39, 933–947 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H. et al. Comparative physiological, metabolomic, and transcriptomic analyses reveal mechanisms of improved abiotic stress resistance in bermudagrass [Cynodon dactylon (L). Pers.] by exogenous melatonin. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 681–694 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Ye T., Zhong B., Liu X. & Chan Z. Comparative proteomic and metabolomic analyses reveal mechanisms of improved cold stress tolerance in bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers.) by exogenous calcium. J. Integr. Plant Biology 56, 1064–1079 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno J. I., Martín R. & Castresana C. Arabidopsis SHMT1, a serine hydroxymethyltransferase that functions in the photorespiratory pathway influences resistance to biotic and abiotic stress. Plant J. 41, 451–463 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noctor G. et al. The role of glycine in determining the rate of glutathione synthesis in poplar. Possible implications for glutathione production during stress. Physiol. Plant. 100, 255–263 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen N. & Hermans C. Proline accumulation in plants: a review. Amino Acids 35, 753–759 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty U. & Tongden C. Evaluation of heat acclimation and salicylic acid treatments as potent inducers of thermotolerance in Cicer arietinum L. Curr. Sci. Bangalore 89, 384 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Lv W. T., Lin B., Zhang M. & Hua X. J. Proline accumulation is inhibitory to Arabidopsis seedlings during heat stress. Plant Physiol. 156, 1921–1933 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. L. Organic acids in the rhizosphere–a critical review. Plant Soil 205, 25–44 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. F., Ryan P. R. & Delhaize E. Aluminium tolerance in plants and the complexing role of organic acids. Trends Plant Sci. 6, 273–278 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweetlove L. J., Beard K. F., Nunes-Nesi A., Fernie A. R. & Ratcliffe R. G. Not just a circle: flux modes in the plant TCA cycle. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 462–470 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B., Liu X. & Fry J. D. Shoot physiological responses of two bentgrass cultivars to high temperature and poor soil aeration. Crop Sci. 38, 1219–1224 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Huang B. & Gao H. Growth and carbohydrate metabolism of creeping bentgrass cultivars in response to increasing temperatures. Crop Sci. 40, 1115–1120 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z. S., Tian S. P., Zheng X. L., Zhou Z. W. & Xu Y. Responses of reactive oxygen metabolism and quality in mango fruit to exogenous oxalic acid or salicylic acid under chilling temperature stress. Physiol. Plant. 130, 112–121 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Sayyari M. et al. Prestorage oxalic acid treatment maintained visual quality, bioactive compounds, and antioxidant potential of pomegranate after long–term storage at 2 °C. J. Agr. Food Chem. 58, 6804–6808 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y. B., Wand C. Z. & Li D. F. Effect of oxalic acid on chlorophyll content and antioxidant system of alfalfa under high temperature stress. Pratacultural Sci. 25, 55–59 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Merewitz E. B. et al. Elevated cytokinin content in ipt transgenic creeping bentgrass promotes drought tolerance through regulating metabolite accumulation. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 1315–1328 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagland C. R. & Arnon D. I. The solution culture method for growing plants without soil. California. Agric. Exp. Circ. 347, 1–32 (1950). [Google Scholar]

- Beard J. B. Turf management for golf courses 2nd edn (ed. James B.) 17–22 (Ann Arbor Press, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- Blum A. & Ebercon A. Cell membrane stability as a measure of drought and heat tolerance in wheat. Crop Sci. 21, 43–47 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Barrs H. D. & Weatherley P. E. A re–examination of the relative turgidity technique for estimating water deficits in leaves. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 15, 413–428 (1962). [Google Scholar]

- Blum A. Osmotic adjustment and growth of barley genotypes under drought stress. Crop Sci. 29, 230–233 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Arnon D. I. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta Vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 24, 1–13 (1949). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elstner E. F. & Heupel A. Inhibition of nitrite formation from hydroxylammoniumchloride: a simple assay for superoxide dismutase. Anal. Biochem. 70, 616–620 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velikova V., Yordanov I. & Edreva A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain–treated bean plants: protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. 151, 59–66 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Dhindsa R. S., Dhindsa P. P. & Thorpe T. A. Leaf senescence: correlated with increased leaves of membrane permeability and lipid peroxidation, and decreased levels of superoxide dismutase and catalase. J. Exp. Bot. 32, 93–101 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Dunand C., Crèvecoeur M. & Penel C. Distribution of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in Arabidopsis root and their influence on root development: possible interaction with peroxidases. New Phytol. 174, 332–341 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thordal-Christensen H., Zhang Z., Wei Y. & Collinge D. B. Subcellular localization of H2O2 in plants. H2O2 accumulation in papillae and hypersensitive response during the barley–powdery mildew interaction. Plant J. 11, 1187–1194 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Giannopolitis C. N. & Ries S. K. Superoxide dismutase. I. Occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 59, 309–314 (1977). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance B. & Maehly A. C. Assay of catalase and peroxidase. Method Enzymol. 2, 764–775 (1955). [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y. & Asada K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate–specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 22, 867–880 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak I., Strbac D. & Marschner H. Activities of hydrogen peroxide–scavenging enzymes in germinating wheat seeds. J. Exp. Bot. 44, 127–132 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein–dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossett D. R., Millhollon E. P. & Lucas M. C. Antioxidant response to NaCl stress in salt–tolerant to and salt–sensitive cultivars of cotton. Crop Sci. 34, 706–714 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Roessner U., Wagner C., Kopka J., Trethewey R. N. & Willmitzer L. Simultaneous analysis of metabolites in potato tuber by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Plant J. 23, 131–142 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizhsky L. et al. When defense pathways collide. The response of Arabidopsis to a combination of drought and heat stress. Plant Physiol. 134, 1683–1696 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y. et al. Application of ethyl chloroformate derivatization for gas chromatography–mass spectrometry based metabolomic profiling. Anal. Chim. Acta 583, 277–283 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]