Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Adolescent e-cigarette use has increased rapidly in recent years, but it is unclear whether e-cigarettes are merely substituting for cigarettes or whether e-cigarettes are being used by those who would not otherwise have smoked. To understand the role of e-cigarettes in overall tobacco product use, we examine prevalence rates from Southern California adolescents over 2 decades.

METHODS:

The Children’s Health Study is a longitudinal study of cohorts reaching 12th grade in 1995, 1998, 2001, 2004, and 2014. Cohorts were enrolled from entire classrooms in schools in selected communities and followed prospectively through completion of secondary school. Analyses used data from grades 11 and 12 of each cohort (N = 5490).

RESULTS:

Among 12th-grade students, the combined adjusted prevalence of current cigarette or e-cigarette use in 2014 was 13.7%. This was substantially greater than the 9.0% adjusted prevalence of current cigarette use in 2004, before e-cigarettes were available (P = .003) and only slightly less than the 14.7% adjusted prevalence of smoking in 2001 (P = .54). Similar patterns were observed for prevalence rates in 11th grade, for rates of ever use, and among both male and female adolescents and both Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White adolescents.

CONCLUSIONS:

Smoking prevalence among Southern California adolescents has declined over 2 decades, but the high prevalence of combined e-cigarette or cigarette use in 2014, compared with historical Southern California smoking prevalence, suggests that e-cigarettes are not merely substituting for cigarettes and indicates that e-cigarette use is occurring in adolescents who would not otherwise have used tobacco products.

What’s Known on This Subject:

E-cigarette use has increased rapidly in recent years among adolescents. It is unknown whether e-cigarettes are merely substituting for cigarettes or whether e-cigarettes are increasing total adolescent tobacco product use via initiation by those who would not otherwise have smoked.

What This Study Adds:

The high prevalence of combined e-cigarette or cigarette use in 2014, compared with historical Southern California smoking prevalence, suggests that e-cigarette use is occurring in adolescents who would not otherwise have used tobacco products.

Since the introduction of electronic cigarettes into the US market in 2007,1 adolescent use has increased rapidly, particularly in the past several years. Data from the National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of adolescents in the United States, show that current (past 30-day) use of e-cigarettes increased exponentially from 1.1% in 2011 to 16.0% in 2015 among high school students.2–6 While the prevalence of e-cigarette use is increasing, cigarette use is generally declining among adolescents; in the NYTS, current cigarette use among high school students fell from 15.8% in 2011 to 9.2% in 2014,2,3,5,6 continuing the decline in prevalence of cigarette use among adolescents from its most recent peak in the mid-1990s when the prevalence of current smoking reached 35%.7 Of note, the prevalence of cigarette smoking did not continue to decline from 2014 (9.2%) to 2015 (9.3%).6 In 2014, current use of e-cigarettes surpassed current cigarette use for the first time in several national studies (including the NYTS2 and the Monitoring the Future Study8), as well as in a number of local and state-level studies,9–11 including our study of Southern California adolescents.12

There are multiple interpretations of recent trends in e-cigarette and cigarette use among adolescents. Adolescents who otherwise would have smoked may be using e-cigarettes instead of cigarettes. Alternatively, e-cigarettes may be recruiting new users who otherwise would not have initiated cigarette use (or perhaps any other tobacco product) if e-cigarettes were not available. Recent data from the 2015 NYTS found a small, nonsignificant increase in the use of any tobacco product from 2013 to 2015 (from 22.9% to 25.3%).2,6 The increase in overall tobacco product use appears to be largely driven by increases in e-cigarette and hookah use in 2013 and 2014, and continued increases in e-cigarette use in 2015, along with no decline in cigarette smoking from 2014 to 2015.2,3 Although these data provide insight into trends over the preceding 3 years, adolescent tobacco use has declined for >20 years.7 The impact of e-cigarettes on adolescent tobacco use trends that have evolved over longer periods is unknown.

We analyzed data from the Southern California Children’s Health Study (CHS), a prospective study of 5 cohorts reaching 12th grade in 1995, 1998, 2001, 2004, and 2014, to describe patterns of smoking among adolescents across these years. On the basis of historical data on smoking initiation over the course of adolescence in these cohorts, we compared the rate of total e-cigarette or cigarette use in 2014 to the rate of cigarette use in 2004 before e-cigarettes were available; we hypothesized that an increase from this benchmark may indicate that e-cigarettes are currently being used by adolescents who would not otherwise have smoked if e-cigarettes were not available.

Methods

Study Sample

The CHS is a prospective cohort study (1993–present), originally designed to study the effects of childhood air pollution exposure.13–15 It comprises 5 cohorts of adolescents (Cohorts A–E) who were recruited and followed through 12th grade (Table 1). Recruitment methods and data collection procedures have been described previously.12–15 Briefly, participants were enrolled from entire classrooms in schools in selected communities in Southern California12,14 in 10th grade (Cohort A, 1993), seventh grade (Cohort B, 1993), fourth grade (Cohort C, 1993 and Cohort D, 1996), kindergarten (Cohort E1, 2003), or first grade (Cohort E2, 2003). The current analysis uses available data from grades 11 and 12 of each cohort from participants who answered questions about tobacco product use (N = 5490; 11th grade: mean age [SD] = 16.9 [0.4]; 12th grade: mean age [SD] = 17.9 [0.4]. In Cohorts A through D, history of cigarette use was collected by in-person interview every year at schools as they were followed over time.15,16 Among participants in Cohorts A through D with data available from 11th or 12th grade, 85.7% of the sample provided information on smoking history in both 11th and 12th grades and therefore contributed to prevalence estimates in both years; 10.6% contributed to 11th grade analyses only and 3.7% contributed to 12th grade analyses only. In Cohorts E1 and E2, who were separated by 1 grade, smoking history was collected every other year, so both 11th- and 12th-grade subjects were included in the 2014 survey. In 2014, smoking history in Cohorts E1 and E2 was collected by self-administered questionnaires under study staff supervision. Cohort A through D subjects were all recruited from the same 12 communities; Cohorts E1 and E2 were recruited from 13 communities, of which 12 participated in the 2014 data collection and 8 were the same as Cohorts A through D.

TABLE 1.

Grade of Adolescents Included in Each Cohort in Each Year of the CHS, 1994–2014

| Cohort | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2012 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 11a | 12a | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| B | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11a | 12a | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| C | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11a | 12a | — | — | — | — | — |

| D | — | — | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11a | 12a | — | — |

| E1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | K | 1 | 9 | 11a |

| E2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 2 | 10 | 12a |

—, no data collected.

Data included in analysis

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained before data collection.

Cigarette and E-Cigarette Use

In all CHS cohorts, participants were asked the number of cigarettes or packs of cigarettes that they had smoked in the past 24 hours, past week, past month, past year, and in their lifetime. In each year, participants were classified as current users if they reported smoking ≥1 cigarettes in the past 24 hours, past week, or past month; participants were classified as ever users if they reported either (1) use in the past year or in their lifetime or (2) listed an age at which they had first smoked. This classification was used for all prevalence estimates of cigarette use alone, across all cohorts.

In 2014, smoking history was assessed in Cohort E participants (in grades 11 and 12) using the same question as in Cohorts A through D, along with 2 additional questions that asked about the age at which each participant had first used a cigarette (“even 1 or 2 puffs”) and the number of days smoked in the past 30 days. In addition, use of e-cigarettes was assessed for the first time using the new questions. Adolescents who had used cigarettes or e-cigarettes on at least 1 of the past 30 days were classified as “current users” of that product. “Ever users” were adolescents who reported having ever tried a product. Analyses evaluating combined product use of cigarettes or e-cigarettes in Cohorts E1 and E2 were based on responses to the new questions. The prevalence rates both for current and ever cigarette use were quite similar using either set of questions, differing by 0.1% for current use and 1.6% for prevalence of ever smoking, and the results of analyses were not substantively different using either set of questions. Therefore, in Cohort E we used the prevalence rates derived from the new questions about cigarette use, which we have reported previously12 and which were common to those used to assess e-cigarette prevalence rates.

Statistical Analysis

Prevalence estimates for ever and current cigarette use were calculated by cohort and grade, using the questionnaire items assessed across all cohorts. In Cohort E (in 2014), we calculated the combined prevalence of cigarette or e-cigarette use (ever or current), which included adolescents who reported use of either product or dual use of both products. Logistic regression models were used to estimate smoking prevalence for each cohort by grade, with adjustment for self-reported sex, ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, or other), and parental education (less than high school education, high school graduate, some college, college degree, some graduate school or higher, unknown/missing). Adjusted models were used to account for the different distribution across cohorts of socioeconomic factors known to be associated with cigarette use. These models were applied separately to current smoking and ever smoking. The distributions of sex, ethnicity, and parental education in Cohort E were used as the reference for calculating the adjusted prevalence estimates from the logistic model. Logistic regression models were also used to evaluate trends in the prevalence of cigarette use (ever or current) over calendar time, by including year of data collection as a continuous predictor variable in separate analyses by grade. Logistic regression models with an interaction term were used to evaluate whether the pattern of cigarette use across cohorts varied by ethnicity or sex. In analyses to assess the sensitivity of results to the participation of different Southern California communities in different cohorts, we additionally restricted analyses to the 8 communities common to all years of all cohorts and adjusted for community. The Statistical Analysis System (SAS, version 9.4) was used for analyses, and figures were created using Stata, version 13.1. All hypothesis testing was conducted assuming a .05 significance level.

Results

Demographic characteristics for each cohort are shown in Table 2. The earlier cohorts (A–D) included a greater proportion of non-Hispanic white adolescents (54%–59%), whereas Cohorts E1 and E2 included more Hispanic adolescents (49%–53%). The distributions of the highest level of parental education differed among the cohorts.

TABLE 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants Enrolled in the CHS, by Cohort, 1994–2014, N = 5490

| Cohort Aa | Cohort Ba | Cohort Ca | Cohort Da | Cohort E1b | Cohort E2b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Total (N = 5490) | 759 | 615 | 1076 | 985 | 1159 | 896 |

| Gradec,d,e | ||||||

| 11 | 713 | 565 | 1016 | 916 | 1159 | — |

| 12 | 627 | 520 | 880 | 774 | — | 896 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 402 (53.0) | 328 (53.3) | 570 (53.0) | 520 (52.8) | 555 (47.9) | 468 (52.2) |

| Female | 357 (47.0) | 287 (46.7) | 506 (47.0) | 465 (47.2) | 604 (52.1) | 428 (47.8) |

| Race/ethnicityd | ||||||

| Hispanic White | 193 (25.4) | 143 (23.3) | 297 (27.6) | 290 (29.4) | 612 (52.8) | 443 (49.4) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 436 (57.4) | 362 (58.9) | 625 (58.1) | 530 (53.8) | 384 (33.1) | 346 (38.6) |

| Other | 130 (17.1) | 110 (17.9) | 154 (14.3) | 165 (16.8) | 163 (14.1) | 107 (11.9) |

| Highest parental educationd,f | ||||||

| <12th grade | 111 (15.2) | 70 (11.8) | 130 (12.5) | 89 (9.5) | 228 (21.2) | 154 (18.6) |

| 12th grade | 157 (21.5) | 122 (20.6) | 189 (18.2) | 172 (18.3) | 177 (16.5) | 127 (15.4) |

| Some college | 288 (39.5) | 249 (42.1) | 451 (43.5) | 447 (47.6) | 393 (36.6) | 318 (38.5) |

| College degree | 93 (12.7) | 55 (9.3) | 115 (11.1) | 114 (12.1) | 137 (12.8) | 118 (14.3) |

| Some graduate school | 81 (11.1) | 95 (16.1) | 151 (14.6) | 117 (12.5) | 139 (12.9) | 110 (13.3) |

—, no data collected.

Cohort A–D communities: Alpine, Lake Elsinore, Lake Gregory, Lancaster, Lompoc, Long Beach, Mira Loma, Riverside, San Dimas, Atascadero, Santa Maria, and Upland.

Cohort E communities: Alpine, Lake Elsinore, Lake Gregory, Mira Loma, Riverside, San Dimas, Santa Maria, Upland, Glendora, Anaheim, San Bernadino, and Santa Barbara.

Some participants contributed to both grades 11 and 12 for Cohorts A–D.

P < .05 for test of difference across cohorts.

Years in grade 11–12: Cohort A, 1994–1995; Cohort B, 1997–1998; Cohort C, 2000–2001; Cohort D, 2003–2004; Cohort E1, 11th: 2014; Cohort E2, 12th: 2014.

Frequencies do not add to total because of missing values.

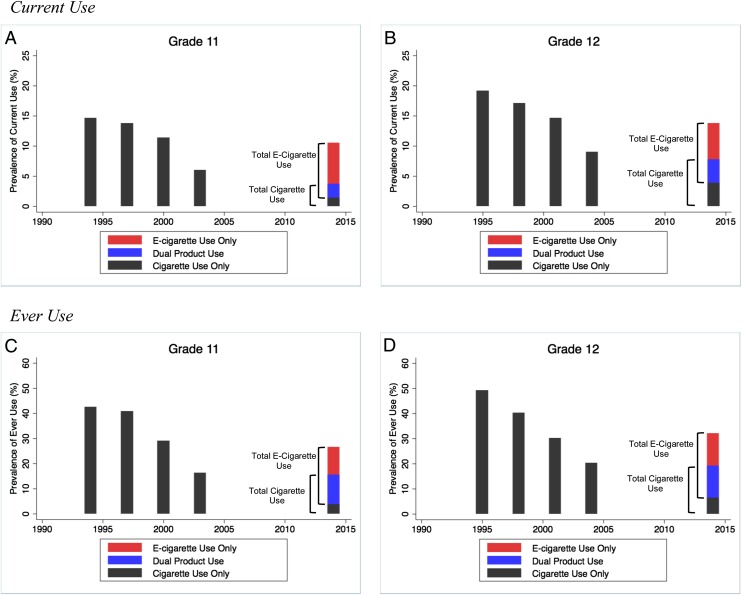

The adjusted prevalence of current smoking among high school students decreased over time from 1995 to 2014 in both 11th and 12th grades (Ptrend < .0001; Fig 1 A and B). Among 12th-grade students in Cohort A (1995), the adjusted prevalence of current smoking was 19.1%; prevalence of use decreased to 17.1% in Cohort B (1998), 14.7% in Cohort C (2001), 9.0% in Cohort D (2004), and 7.8% in Cohort E (2014). Although the prevalence of current cigarette use was lowest among students in both grades in 2014, the combined prevalence of current cigarette and/or e-cigarette use was similar to or greater than that for cigarette use alone 10 to 15 years ago, before e-cigarettes were available (Fig 1 A and B). For example, among 12th-grade students, the adjusted prevalence of combined use of either product in 2014 was 13.7% (3.8% dual users of cigarettes and e-cigarettes, 3.9% cigarette only users, and 6.0% e-cigarette only users), which was similar to the 14.7% prevalence of cigarette use in 2001 (P = .54), and nearly 5 percentage points higher than the adjusted prevalence of current cigarette use in 2004 (9.0%; P = .003).

FIGURE 1.

Adjusted prevalence estimates among adolescents in the CHS by cohort for current cigarette use (all cohorts), and current cigarette or e-cigarette use (Cohort E) in (A) grade 11 and (B) grade 12 and for ever cigarette use (all cohorts) and ever cigarette or e-cigarette use (Cohort E) in (C) grade 11 and (D) grade 12, 1994–2014.

The prevalence of ever cigarette use followed similar patterns of an overall decrease over time across Cohort A (1994–1995) to Cohort E (2014) for both 11th- and 12th-grade students (Ptrend < .0001; Fig 1 C and D). However, the 11th- and 12th-grade prevalence rates for ever cigarette use in 2014 were not statistically significantly lower than the prevalence in Cohort D 10 years earlier in 2003–2004 (P = .59, 0.56, respectively). The prevalence of combined ever use of cigarettes or e-cigarettes also surpassed rates of ever cigarette use more than a decade ago. Among 12th-grade students, the adjusted prevalence of ever use of either cigarettes or e-cigarettes in 2014 was 32.1%, substantially higher than the adjusted prevalence of ever cigarette use in 2004 (20.4%; P < .0001), and slightly higher than the adjusted prevalence in 2001 (30.2%; P = .41).

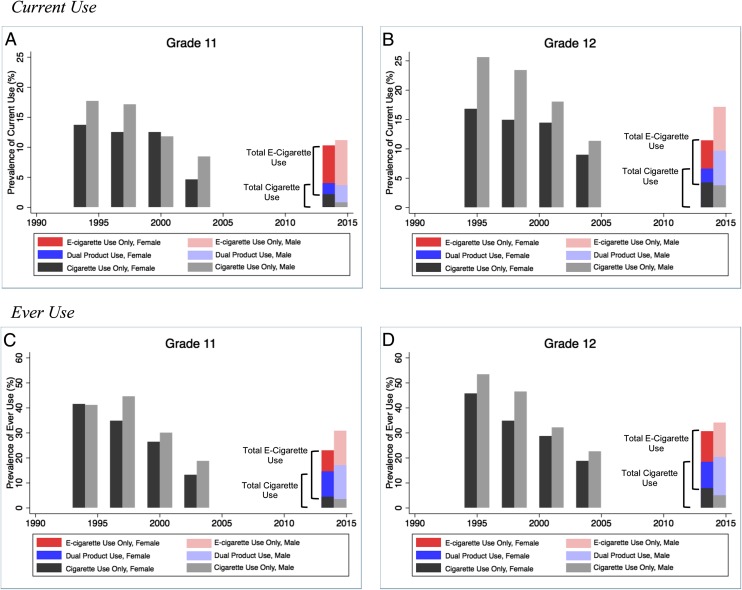

Among both male and female adolescents, the prevalence of cigarette or e-cigarette use (ever or current) in both 11th and 12th grades in 2014 was higher than the prevalence of smoking in 2003–2004 and was generally similar to the prevalence of smoking in 2000–2001 (Fig 2 A–D). There was no difference between sexes in these patterns of decline in smoking over time (interaction P > .05). The prevalence of current and ever use of cigarettes within cohorts was higher among male than among female adolescents, with more pronounced differences observed among 12th-grade students; combined rates of e-cigarette or cigarette use in 2014 were also larger in male than female adolescents.

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence estimates among adolescents in the CHS by cohort and sex for current cigarette use (all cohorts) and current cigarette or e-cigarette use (Cohort E) in (A) grade 11 and (B) grade 12 and for ever cigarette use (all cohorts) and ever cigarette or e-cigarette use (Cohort E) in (C) grade 11 and (D) grade 12, 1994–2014.

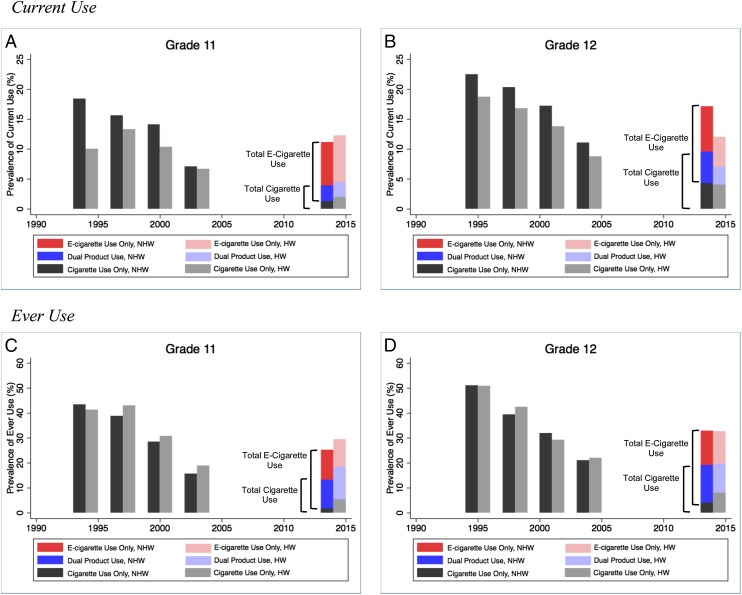

The prevalence of current and ever smoking also decreased over time from 1994 to 2014 among both non-Hispanic white adolescents and Hispanic adolescents (P < .0001; Fig 3 A–D; interaction P for ethnicity >.05). In both ethnic groups, the combined prevalence of current cigarette or e-cigarette use in 2014 exceeded the rate of current cigarette use in 2003 (11th grade) or 2004 (12th grade). For example, among non-Hispanic white 12th-grade students, the combined rate of current cigarette or e-cigarette use in 2014 in Cohort E was identical to the rate of smoking in 2001 (17.2%; 5.0% dual use, 4.4% cigarette only use, 7.8% e-cigarette only use); the rate of combined use among Hispanic white adolescents in 2014 (12.0%; 2.9% dual use, 5.0% cigarette only use, 4.1% e-cigarette only use) was >3 percentage points higher than the rate of smoking in 2004 (8.8%) and only slightly less than the rate of smoking in 2001 (13.8%). Similar patterns were observed for ever use in both ethnicities; the combined rate of cigarette or e-cigarette use in 2014 in 11th- and 12th-grade students was higher than the rates of smoking 10 years earlier in both ethnic groups. We did observe differences in rates of smoking within cohorts between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white study participants. Current smoking prevalence was consistently higher among non-Hispanic white adolescents than among Hispanic white adolescents (Fig 3 A and B), but ever use was generally similar or modestly higher among Hispanic white adolescents than among non-Hispanic white adolescents (Fig 3 C and D). In 2014 the combined prevalence of e-cigarette or cigarette use (both current and ever) was greater in Hispanic whites than non-Hispanic whites in 11th grade, which appears to result from higher prevalence of cigarette only use (dual and e-cigarette only use was similar across both groups). In 12th grade, the combined prevalence of e-cigarette or cigarette use was greater in non-Hispanic whites than Hispanic white youth, largely resulting from greater levels of e-cigarette and dual product use.

FIGURE 3.

Prevalence estimates among adolescents in the CHS by cohort and by ethnicity for current cigarette use (all cohorts), and current cigarette or e-cigarette use (Cohort E) in (A) grade 11 and (B) grade 12 and for ever cigarette use (all cohorts) and ever cigarette or e-cigarette use (Cohort E) in (C) grade 11 and (D) grade 12, 1994–2014. HW, Hispanic white; NHW, non-Hispanic white.

In analyses restricted to the 8 communities with data available across all cohorts, trends in prevalence across cohorts and across grades within cohorts, as well as the ethnic- and sex-specific patterns, were similar to those observed in the entire sample (data not shown).

Discussion

These Southern California communities have experienced a marked decrease in adolescent cigarette use over the past 2 decades. However, among both 11th- and 12th-grade students, the combined prevalence of current cigarette or e-cigarette use in 2014 was substantially greater than the prevalence of smoking in 2004 (among 12th graders, eg, 13.7% and 9.0%, respectively) and was almost as high as the prevalence of smoking in 2001 (14.7% for 12th graders).

This substantially increased combined prevalence of cigarette smoking or e-cigarette use in 2014, compared with smoking rates a decade earlier, when e-cigarettes were not available, suggests that e-cigarettes are not used only by adolescents who would otherwise be smoking cigarettes. If, for example, the current rates of smoking would not have changed from 2004 to 2014 in the absence of e-cigarettes, then 1.2% of adolescents in Southern California, the difference between the 7.8% adjusted prevalence of cigarette use in 2014 and 9.0% in 2004, may be substituting e-cigarettes for cigarettes. An additional 4.7% of e-cigarette users, the difference between the 13.7% combined prevalence of e-cigarette or cigarette use in 2014 and the 9.0% prevalence of cigarette use in 2004 likely would not have used cigarettes if e-cigarettes were not available, under the assumption that the rate of smoking from 2004 to 2014 would not have changed. The assumption that smoking rates would not have decreased in the absence of e-cigarettes likely makes this estimate of the proportion of e-cigarette users who would not otherwise have used cigarettes conservative.

The general prevalence patterns and the findings compared with the 2004 data were similar among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white participants and in male and female participants; thus, tobacco control interventions geared toward youth are equally needed for youth of both sexes and ethnicities. The prevalence of cigarette use or combined use (Cohort E only) did differ by gender and ethnicity within each cohort. Hispanic adolescents were less likely to report cigarette use in each cohort among both 11th- and 12th-grade students but as likely to report ever use, a pattern consistent with historically reported ethnic comparisons.3,7,17,18 Male respondents were generally more likely to report use of cigarettes, e-cigarettes, or combined use of cigarettes or e-cigarettes, which is also consistent with previous literature.2,7,12,19

A major strength of this study is the use of >20 years of data collected across 5 cohorts drawn from the same CHS communities to assess patterns of change in cigarette use in Southern California. Because all results were adjusted for the Cohort E distribution of race/ethnicity, sex, and parental education, it is unlikely that differences across cohorts were influenced by changes in sociodemographic characteristics of the population over time. The study is also subject to some limitations. Data on use of tobacco products other than cigarettes were not collected from earlier cohorts. Thus, the contribution of hookah, cigar/cigarillo, pipe, or smokeless tobacco use to the prevalence of all tobacco product use in earlier cohorts is not known. Data from the NYTS have shown relatively stable prevalence of use of cigars and smokeless tobacco from 2000 to 2012,20 followed by a decrease in cigar and pipe use and in smokeless tobacco use from 2011 to 2014.2 Although national results may not be generalizable to Southern California (and vice versa), we cannot exclude the possibility that e-cigarette use is substituting for these combustible tobacco products. No data are available on trends in hookah use across the periods of interest in this study, but prevalence of hookah use increased in the NYTS from 2011 to 2014,2 so it seems unlikely that the increase in prevalence of e-cigarette use during this period reflects substitution of e-cigarettes for hookah use among participants who otherwise would have smoked hookah use in previous cohorts. Analyses were restricted to Hispanic youth (historically an underrepresented population in tobacco regulatory science research) and non-Hispanic white youth, who comprise the majority of the Southern California population; the prevalence estimates were imprecise in other racial/ethnic groups in our study, which made up <20% of the sample. Additional research is needed to determine whether similar patterns of product use over time occurred in other racial groups and in other geographic regions.

E-cigarettes have gained popularity in recent years, in part because of availability in a wide variety of flavorings21 that may be appealing to adolescents and young adults,22 the perception that e-cigarettes are less harmful than smoking,23 absence or poor enforcement of regulations on indoor use,24 and the recent popularity of product-specific venues that encourage use of these products in social situations, such as vape shops.25 Such characteristics of e-cigarettes may be recruiting new users who are deterred from initiating cigarettes because of concerns about the health hazards of smoking and social stigmatization of cigarette use.7 There is concern that the increasing prevalence of e-cigarette use could even lead to initiation of smoking among previously nonsmoking adolescent e-cigarette users in what has been described as a “gateway effect,” either as a result of social normalization of alternative product use and smoking behaviors more generally, leading to renormalization of smoking or by directly increasing use of cigarettes through establishment of reward seeking behaviors (eg, nicotine dependence).26–30 Although our results demonstrated a decline in cigarette use in the past decade, we also have observed a markedly increased likelihood of intention to use cigarettes31 among e-cigarette users in the CHS in 2014 who had never smoked, results which are consistent with 2 recent studies examining the association of e-cigarette use with susceptibility to smoking,28,30 and recent longitudinal studies that have found that never-smoking e-cigarette users were more likely to report use of cigarettes a year later than never e-cigarette users.32–34

The use of e-cigarettes by nonsmoking adolescents poses several potential public health problems. First, use of e-cigarettes containing nicotine may directly contribute to nicotine dependence in late adolescence or early adulthood, putting adolescents at risk for lifelong nicotine dependence.35,36 Use of e-cigarettes, even without nicotine, may normalize tobacco product use behaviors more generally, which could then lead to increased rates of addiction via use of other nicotine-containing products, including cigarettes and other harmful combustible tobacco products.35–37 Second, in addition to lifelong problems associated with nicotine dependence, exposure to nicotine in adolescence adversely affects cognitive function and development.19 There is also evidence that e-cigarettes may generate aldehydes and other toxic chemicals and that flavoring additives may induce adverse respiratory health effects in e-cigarette users.38 Although the adverse health effects of e-cigarettes may be less than those of cigarettes, the long-term consequences of e-cigarette use are not known because these products have been on the market for less than a decade.

Conclusions

Longitudinal data on emerging adolescent tobacco and alternative tobacco product use, including detailed information on topography of e-cigarette use and dose of nicotine, are needed to understand the role of e-cigarettes in nicotine addiction and whether e-cigarette users who have not used combustible cigarettes will, in the future, continue using e-cigarettes only, quit using tobacco products altogether, or progress to combustible cigarette users or dual users of both products. However, the high combined prevalence of e-cigarette use or cigarette use in 2014, compared with historical Southern California smoking prevalence, suggests that adolescents are not merely substituting e-cigarettes for cigarettes but that e-cigarettes are instead recruiting a new group of users who would not likely have initiated combustible tobacco product use in the absence of e-cigarettes, which poses a potential threat to the public health of adolescent populations.

Glossary

- CHS

Southern California Children’s Health Study

- NYTS

National Youth Tobacco Survey

Footnotes

Dr Barrington-Trimis formulated the research question, interpreted the results, wrote and edited the manuscript, and is guarantor of the article; Dr Urman contributed to formulating the research question, conducted the analyses, interpreted the results, and edited the manuscript; Dr Berhane contributed to formulating the research question, interpretation of the results, statistical analyses, and editing the manuscript; Mr Howland developed the questionnaire, collected data, and contributed to the draft of the manuscript; Drs Cruz, Unger, Leventhal, Gilreath, and Samet contributed to formulating the research question, interpretation of results and editing the manuscript; Dr McConnell designed the study, collected data, and contributed to formulating the research question and interpretation of the results and critically reviewed the manuscript; and all authors approved the manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by grant P50CA180905 from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health and the US Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found on online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2016-1502.

References

- 1.Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes: a scientific review. Circulation. 2014;129(19):1972–1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(14):381–385 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrazola RA, Neff LJ, Kennedy SM, Holder-Hayes E, Jones CD; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(45):1021–1026 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Notes from the field: electronic cigarette use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(35):729–730 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011 and 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(45):893–897 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh T, Arrazola RA, Corey CG, et al. Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students - United States, 2011-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(14):361–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use 1975–2014: Overview: Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishnan-Sarin S, Morean ME, Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, Kong G. E-cigarette use among high school and middle school adolescents in Connecticut. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(7):810–818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wills TA, Knight R, Williams RJ, Pagano I, Sargent JD. Risk factors for exclusive e-cigarette use and dual e-cigarette use and tobacco use in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/135/1/e43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.State Health Officer’s Report on E-Cigarettes: A Community Health Threat. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Public Health, California Tobacco Control Program; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrington-Trimis JL, Berhane K, Unger JB, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with adolescent electronic cigarette and cigarette use. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):308–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters JM, Avol E, Navidi W, et al. A study of twelve Southern California communities with differing levels and types of air pollution. I. Prevalence of respiratory morbidity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(3):760–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McConnell R, Berhane K, Yao L, et al. Traffic, susceptibility, and childhood asthma. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(5):766–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gauderman WJ, Gilliland GF, Vora H, et al. Association between air pollution and lung function growth in southern California children: results from a second cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(1):76–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gauderman WJ, Avol E, Gilliland F, et al. The effect of air pollution on lung development from 10 to 18 years of age. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(11):1057–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2013. MMWR Suppl. 2014;63(4):1–168 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Cigarette use among high school students—United States, 1991–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(26):797–801 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arrazola RA, Kuiper NM, Dube SR. Patterns of current use of tobacco products among U.S. high school students for 2000–2012—findings from the National Youth Tobacco Survey. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(1):54–60.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu SH, Sun JY, Bonnevie E, et al. Four hundred and sixty brands of e-cigarettes and counting: implications for product regulation. Tob Control. 2014;23(suppl 3):iii3–iii9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kong G, Morean ME, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S. Reasons for electronic cigarette experimentation and discontinuation among adolescents and young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(7):847–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latimer LA, Batanova M, Loukas A. Prevalence and harm perceptions of various tobacco products among college students. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(5):519–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Nonsmokers' Rights Foundation States and municipalities with laws regulating use of electronic cigarettes. Available at: www.no-smoke.org/pdf/ecigslaws.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2015

- 25.Lee YO, Kim AE. “Vape shops” and “E-cigarette lounges” open across the USA to promote ENDS. Tob Control. 2015;24(4):410–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanwick R. E-cigarettes: Are we renormalizing public smoking? Reversing five decades of tobacco control and revitalizing nicotine dependency in children and youth in Canada. Paediatr Child Health. 2015;20(2):101–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore GF, Littlecott HJ, Moore L, Ahmed N, Holliday J. E-cigarette use and intentions to smoke among 10-11-year-old never-smokers in Wales. Tob Control. 2016;25:147–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bunnell RE, Agaku IT, Arrazola RA, et al. Intentions to smoke cigarettes among never-smoking U.S. middle and high school electronic cigarette users, National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011–2013. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):228–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coleman BN, Apelberg BJ, Ambrose BK, et al. Association between electronic cigarette use and openness to cigarette smoking among US young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):212–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wills TA, Sargent JD, Knight R, Pagano I, Gibbons FX. E-cigarette use and willingness to smoke: a sample of adolescent non-smokers. Tob Control. 2016;25(E1):e52–e59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barrington-Trimis J, Berhane K, Unger J, et al. The e-cigarette psychosocial environment, e-cigarette use, and susceptibility to cigarette smoking [published online ahead of print May 6, 2016]. J Adolesc Health. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with initiation of combustible tobacco product smoking in early adolescence. JAMA. 2015;314(7):700–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Primack BA, Soneji S, Stoolmiller M, Fine MJ, Sargent JD. Progression to traditional cigarette smoking after electronic cigarette use among US adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(11):1018–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wills TA, Knight R, Sargent JD, Gibbons FX, Pagano I, Williams RJ. Longitudinal study of e-cigarette use and onset of cigarette smoking among high school students in Hawaii [published online ahead of print January 25, 2016]. Tob Control. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kandel DB, Kandel ER. A molecular basis for nicotine as a gateway drug. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(21):2038–2039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bell K, Keane H. All gates lead to smoking: the “gateway theory,” e-cigarettes and the remaking of nicotine. Soc Sci Med. 2014;119:45–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider S, Diehl K. Vaping as a catalyst for smoking? An initial model on the initiation of electronic cigarette use and the transition to tobacco smoking among adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barrington-Trimis JL, Samet JM, McConnell R. Flavorings in electronic cigarettes: an unrecognized respiratory health hazard? JAMA. 2014;312(23):2493–2494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]