Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Research reveals mixed evidence for the effects of adenotonsillectomy (AT) on cognitive tests in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS). The primary aim of the study was to investigate effects of AT on cognitive test scores in the randomized Childhood Adenotonsillectomy Trial.

METHODS:

Children ages 5 to 9 years with OSAS without prolonged oxyhemoglobin desaturation were randomly assigned to watchful waiting with supportive care (n = 227) or early AT (eAT, n = 226). Neuropsychological tests were administered before the intervention and 7 months after the intervention. Mixed model analysis compared the groups on changes in test scores across follow-up, and regression analysis examined associations of these changes in the eAT group with changes in sleep measures.

RESULTS:

Mean test scores were within the average range for both groups. Scores improved significantly (P < .05) more across follow-up for the eAT group than for the watchful waiting group. These differences were found only on measures of nonverbal reasoning, fine motor skills, and selective attention and had small effects sizes (Cohen’s d, 0.20–0.24). As additional evidence for AT-related effects on scores, gains in test scores for the eAT group were associated with improvements in sleep measures.

CONCLUSIONS:

Small and selective effects of AT were observed on cognitive tests in children with OSAS without prolonged desaturation. Relative to evidence from Childhood Adenotonsillectomy Trial for larger effects of surgery on sleep, behavior, and quality of life, AT may have limited benefits in reversing any cognitive effects of OSAS, or these benefits may require more extended follow-up to become manifest.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Research indicates variable but possibly selective effects of adenotonsillectomy (AT) on cognitive test scores in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. However, few if any studies have examined changes after AT in a randomized trial assessing diverse cognitive skills.

What This Study Adds:

Findings confirm small, selective effects of AT on cognitive test scores in a randomized trial of AT compared with nonsurgical management, as well as associations of pre-AT to post-AT gains in scores with improvement on measures of sleep disturbance.

Childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is characterized by intermittent upper airway obstruction that disrupts normal ventilation during sleep and sleep patterns.1 The prevalence of OSAS is ∼1% to 6%, with higher rates in African Americans and children from families of lower socioeconomic status.2–4 Children with untreated OSAS are at risk for adverse outcomes ranging from daytime sleepiness and compromised cardiovascular health to behavior problems and impairments in cognition and academic performance.5–11 Problems in behavior and emotional regulation are common in children with OSAS compared with healthy controls, but evidence for adverse effects of OSAS on children’s cognitive abilities is more mixed.6 Some studies fail to find differences between children with OSAS and healthy controls,12,13 and those that do report variable associations of measures of sleep disturbance with cognitive test scores.7,14–18 Similarly, studies of outcomes of adenotonsillectomy (AT) in children with OSAS indicate variable benefits on such tests, with little evidence for associations of these effects with the severity of OSAS and sleep disruption.8,13,14,16,19–26

In the recently completed multicenter Childhood Adenotonsillectomy Trial (CHAT), children with OSAS without prolonged oxyhemoglobin desaturation assigned to early AT (eAT) improved more than those assigned to watchful waiting with supportive care (WWSC) on key secondary outcomes.27–29 Specifically, the eAT group improved more than the WWSC group from a baseline preintervention assessment to a 7-month postintervention follow-up on polysomnographic indices and symptoms of OSAS, global indices of behavior, and quality of life, but not on the primary cognitive outcome measure (A Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment [NEPSY] Attention and Executive Function Domain score) or on global cognitive ability. However, the individual tests that make up these 2 composite measures and other tests predesignated as secondary measures of outcome were not examined for their sensitivity to the effects of AT. Examination of these measures was warranted to determine potential benefits of AT on specific cognitive skills and identify measures sensitive to the effects of AT on children’s functioning but more objective than child behavior ratings.5,10

The primary aim of this study was to determine whether the eAT group improved more than the WWSC group on select measures of cognitive function. Despite variability in the cognitive tests that best discriminate children with OSAS from healthy controls, OSAS-related weaknesses are most evident on tests of sustained and selective attention, response inhibition, nonverbal reasoning, phonological processing, verbal fluency, and fine motor and visual–motor skills.6,7,9,14,16–18,30 Findings from nonrandomized trials of AT in children with snoring or OSAS suggest beneficial effects of surgery on attention and nonverbal problem solving.8,14,19,20 Based on this evidence we hypothesized that the eAT group would improve more across follow-up than the WWSC group on tests of these skills. Within the eAT group we also investigated increases in test scores across follow-up in relation to the degree of improvement in OSAS as measured by overt symptoms and polysomnography. Finally, we explored whether measures of more severe sleep disturbance at baseline were associated with lower baseline test scores.

Methods

Sample

The rationale and methods of the CHAT trial are detailed in previous reports.4,28 In brief, between January 2008 and September 2011, 453 participants were recruited by screening children 5.0 to 9.9 years of age referred from sleep programs, pediatric and otolaryngology clinics, and the surrounding communities of 6 academic medical centers. Study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of each center. Informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians, and assent was obtained from children ≥7 years old. Eligible children were otherwise healthy and had a history of snoring, tonsillar hypertrophy, and polysomnography indicating OSAS without prolonged oxyhemoglobin desaturation (<2% of total sleep time with pulse oxygen saturation <90%) and an obstructive apnea index (apneas per hour of sleep) of 1 to 20 or an obstructive apnea hypopnea index (apneas or hypopneas per hour of sleep) of 2 to 30. Children with extreme obesity (BMI z score ≥3) or on psychotropic medications were excluded, including those treated for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Procedures and Measures

Before group assignment, participants completed polysomnography and a baseline assessment that included parent ratings of sleep symptoms and child neuropsychological testing.4 Children were then randomly assigned by the data coordinating center to WWSC (n = 227) or eAT (n = 226). Assignment was stratified by site, age (5–7 or 8–10 years), race (African American or other), and overweight status (BMI age- and gender-adjusted z score ≤85% or >85%), with the eAT group receiving surgery within 4 weeks of randomization. All assessments were readministered after 7 months (mean [SD] = 7.1 [0.9]). The follow-up period was chosen as one that would be acceptable to parents and referring physicians while also sufficient to detect post-AT changes in cognitive test scores.7,26,31 Measures are listed in Table 1 and included indices of sleep disturbance as assessed by polysomnography, parent ratings, and neuropsychological tests of verbal skills, nonverbal reasoning, attention and executive function, perceptual–motor and visual–spatial skills, and verbal learning and memory (for test descriptions see Supplemental Table 6). Tests were individually administered in 2 fixed sequences counterbalanced across participants by examiners who were uninformed of group assignment.

TABLE 1.

Measures

| Source and Measure |

|---|

| Polysomnography |

| Arousal index: number of electrocortical arousals per hour of sleep |

| Apnea hypopnea index: number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep |

| Oxygen desaturation index of ≥3% per hour of sleep |

| Percentage sleep time with end-tidal CO2 values >50 mm Hg |

| Percentage sleep time in stage 1 (light) sleep |

| Percentage sleep time in stage 3 sleep |

| Percentage sleep time in rapid eye movement sleep |

| Sleep efficiency: percentage time in sleep during the total recording period |

| Normalization of OSAS: decrease from baseline to 7-mo follow-up in AHI to <2 events per hour and of obstructive apnea index to <1 event per hour |

| Parent ratings of sleep disturbance |

| PSQ-SRBD32: proportion of 22 yes/no items endorsed, with higher scores indicating more problems |

| 18-item Obstructive Sleep Apnea assessment tool33: range 18–126, with higher scores indicating more negative disease specific quality of life |

| mESS34: range 0–24, with higher scores indicating more sleepiness |

| Neuropsychological domains and tests |

| Verbal skills: DAS-II35 Word Definitions and Verbal Similarities; NEPSY36 Phonological Processing, Comprehension of Instructions, and Speeded Naming |

| Nonverbal reasoning: DAS-II Matrices, Sequential and Quantitative Reasoning, Pattern Construction, and Recall of Designs |

| Attention and executive function: NEPSY Visual Attention, Auditory Attention and Response Set, and Tower; NEPSY-II37 Inhibition (Naming, Inhibition, and Switching conditions) and Word Generation (Semantic and Initial Letter conditions) |

| Perceptual–motor and visual–spatial skills: Purdue Pegboard Test38,39 (Dominant Hand, Non-dominant Hand, and Both Hands conditions); Developmental Test of Visual Motor Integration40; NEPSY Arrows |

| Verbal learning and memory: WRAML241 Verbal Learning Test (Learning, Recall, and Recognition conditions) |

Standardized scores for age used for all neuropsychological tests, including T-scores for the DAS-II (normative mean [SD] = 50 [10], range 10–90), scaled scores for the NEPSY, NEPSY-II, and WRAML2 (normative mean [SD] = 50 [10], range 1–19), and standard scores for the Developmental Test of Visual Motor Integration (normative mean [SD] = 100 [15], range 45–155). Age standardized scores for the Purdue Pegboard were obtained by regressing the raw scores at baseline on age and sex to estimate expected scores and computing differences in z score units between the expected and obtained scores. Higher scores on all neuropsychological tests indicate higher skill levels.

Statistical Analysis

Repeated-measures mixed-effects models were fit to assess group differences in change in age-adjusted standard scores from baseline to the 7-month follow-up. Factors were group (WWSC vs eAT), visit (baseline, follow-up), and the group × visit interaction. Stratification factors and maternal education level were included as covariates. All children with valid test scores were included in the analysis. An intention-to-treat approach was used in the primary analyses, followed by analyses that excluded 20 children (13 WWSC, 7 eAT) who did not receive their assigned treatment (ie, crossovers).

To examine the relationship of changes in the sleep measures to changes in cognitive tests across follow-up for the eAT group, we estimated gains in scores related to practice effects (ie, greater familiarity of children with the tests at follow-up) by using data from the WWSC group. For each test, follow-up scores for these children were regressed on their corresponding baseline scores. The regression equations were then applied to the eAT group to estimate expected follow-up scores. Cognitive change was defined as the standardized difference between the expected and observed scores at follow-up, reflecting the degree to which the follow-up scores differed from those predicted by the baseline scores and practice effects. Subsequent regression models examined changes in the sleep measures as predictors of these change scores, controlling for stratification factors and maternal education. All polysomnography measures except percentage sleep time in rapid eye movement sleep were log transformed to provide more normal distributions. Regression analysis controlling for these same factors was also used to examine associations of baseline neuropsychological test scores for the total sample with baseline sleep measures.

CHAT was designed to detect an effect size of ≥0.32 with 90% power for group differences in the primary outcome of attention and executive function.28 For the exploratory analyses presented here, corrections were not made for multiple comparisons. We computed effect sizes by using Cohen’s d for group differences from mixed models and f2 for regressions, defining small, medium, and large effects, respectively, as 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 for d and 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 for f2.42 We analyzed data by using SAS Proprietary Software 9.3 (TS1M0; SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) and IBM SPSS Statistics Version 23 (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 2 presents group demographic and sleep characteristics and Table 3 test scores on the neuropsychological battery at baseline and follow-up. Although mean scores at baseline were within the average range relative to normative standards, means for 2 NEPSY 2nd edition (NEPSY-II) Inhibition conditions (Inhibition and Switching) were somewhat reduced relative to other scores (scaled scores = 8, 25th percentile). The WWSC and eAT groups differed significantly in only 1 of the tests at baseline.

TABLE 2.

Sample Demographic and Sleep Characteristics at Baseline

| Characteristic | WWSC Group | eAT Group |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 7.01 (1.39) | 7.06 (1.41) |

| Male, n (%) | 118 (52) | 101 (45) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| African American | 123 (54) | 126 (56) |

| White | 81 (36) | 75 (33) |

| Other | 23 (10) | 25 (11) |

| Hispanic ethnicity, n (%) | 21 (9) | 16 (7) |

| Maternal education less than high school, n (%) | 64 (32) | 62 (32) |

| BMI z score, mean (SD)a | 0.87 (1.25) | 0.87 (1.35) |

| Overweight, n (%)b | 106 (47) | 108 (48) |

| Polysomnography measures | ||

| Arousal index, median (interquartile range) | 7.79 (6.04–10.12) | 8.03 (6.31–10.30) |

| Apnea hypopnea index, median (interquartile range) | 4.51 (2.57–8.84) | 4.79 (2.78–8.67) |

| Oxygen desaturation index of ≥3% per hour of sleep, median (interquartile range) | 4.71 (2.36–9.48) | 4.97 (2.46–10.10) |

| Percentage sleep time with end-tidal CO2 values >50 mm Hg, median (interquartile range)* | 0.73 (0.28–5.68) | 1.80 (0.40–13.93) |

| Sleep efficiency, median (interquartile range) | 92.1 (83.6–96.6) | 93.0 (85.5–96.3) |

| Percentage sleep time in stage 1 (light) sleep, median (interquartile range) | 8.0 (6.0–10.7) | 7.8 (5.6–10.7) |

| Percentage sleep time in stage 3 sleep, median (interquartile range) | 31.3 (26.5–35.0) | 31.4 (26.2–36.8) |

| Percentage sleep time in rapid eye movement sleep, mean (SD) | 18.2 (4.3) | 18.6 (4.2) |

| Behavioral measures of sleep disturbance | ||

| PSQ-SRBD, mean (SD) | 0.50 (0.18) | 0.49 (0.18) |

| 18-item Obstructive Sleep Apnea assessment tool, mean (SD) | 54.12 (18.83) | 53.12 (18.33) |

| mESS, mean (SD) | 7.54 (5.15) | 7.08 (4.67) |

All data are untransformed, with medians (interquartile range) listed for variables with nonnormal distributions.

BMI age- and gender-adjusted z score.

Overweight defined as BMI z score ≥85%.

Significant group difference (P = .035); all other differences nonsignificant.

TABLE 3.

Standard Score Means (SDs) for eAT and WWSC Groups on Neuropsychological Test Battery at Baseline and Follow-up

| WWSC | eAT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skill Domain and Test | Baseline (n = 227) | Follow-up (n = 203) | Baseline (n = 226) | Follow-up (n = 196) |

| Verbal skills | ||||

| DAS-II Word Definitions | 48.68 (8.15) | 49.33 (8.25) | 49.78 (9.08) | 50.41 (8.35) |

| DAS-II Verbal Similarities | 49.10 (9.09) | 50.22 (8.77) | 49.46 (7.69) | 50.30 (8.72) |

| NEPSY Phonological Processinga | 8.49 (3.52) | 8.98 (3.14) | 9.18 (3.24) | 9.39 (3.52) |

| NEPSY Comprehension of Instructions | 10.02 (2.84) | 10.18 (2.91) | 10.25 (3.00) | 10.45 (3.07) |

| NEPSY Speeded Naming | 8.77 (3.30) | 9.43 (3.40) | 8.99 (3.39) | 9.64 (3.11) |

| Nonverbal reasoning | ||||

| DAS-II Matrices | 47.07 (7.83) | 47.84 (9.69) | 47.96 (8.79) | 49.88 (8.78) |

| DAS-II Sequential and Quantitative Reasoning | 46.33 (8.67) | 46.71 (8.96) | 45.93 (8.34) | 48.03 (8.67) |

| DAS-II Pattern Construction | 48.54 (7.62) | 49.92 (7.54) | 48.97 (6.94) | 49.76 (6.98) |

| DAS-II Recall of Designs | 48.46 (8.56) | 49.67 (8.25) | 48.21 (8.57) | 49.49 (8.31) |

| Attention and executive function | ||||

| NEPSY Visual Attention | 9.93 (2.89) | 10.36 (2.88) | 9.91 (2.87) | 10.96 (3.03) |

| NEPSY Auditory Attention and Response Set | 10.04 (2.68) | 10.68 (2.90) | 9.99 (2.83) | 10.81 (2.62) |

| NEPSY Tower | 10.52 (2.81) | 11.28 (2.71) | 10.70 (2.95) | 11.53 (2.81) |

| NEPSY-II Inhibition, Naming | 8.59 (3.61) | 8.90 (3.65) | 8.84 (3.54) | 9.30 (3.72) |

| NEPSY-II Inhibition, Inhibition | 8.08 (3.43) | 8.76 (3.44) | 7.83 (3.25) | 9.11 (3.42) |

| NEPSY-II Inhibition, Switching | 8.02 (3.02) | 8.33 (3.25) | 8.01 (3.50) | 9.21 (3.81) |

| NEPSY-II Word Generation, Semantic Condition | 10.60 (3.02) | 10.77 (3.08) | 10.29 (3.05) | 10.51 (3.07) |

| NEPSY-II Word Generation, Initial Letter Condition | 8.81 (2.64) | 9.24 (3.17) | 8.91 (2.64) | 9.16 (2.96) |

| Perceptual–motor and visual–spatial skills | ||||

| Purdue Pegboard Dominant Hand | 0.03 (1.00) | 0.15 (1.05) | −0.03 (0.99) | 0.27 (0.96) |

| Purdue Pegboard Non-Dominant Hand | −0.05 (1.09) | 0.15 (1.14) | 0.05 (0.90) | 0.18 (1.10) |

| Purdue Pegboard Both Hands | 0.03 (0.97) | −0.04 (0.80) | −0.03 (1.02) | 0.10 (0.81) |

| Developmental Test of Visual Motor Integration | 95.09 (12.55) | 93.91 (10.93) | 94.33 (10.06) | 93.94 (11.34) |

| NEPSY Arrows | 9.92 (2.77) | 10.28 (2.67) | 10.31 (2.80) | 10.46 (2.72) |

| Verbal learning and memory | ||||

| WRAML2 Verbal Learning | 10.04 (2.76) | 10.75 (2.77) | 10.00 (2.48) | 10.71 (2.86) |

| WRAML2 Verbal Learning Recall | 10.26 (2.46) | 10.23 (2.65) | 10.00 (2.35) | 10.22 (2.72) |

| WRAML2 Verbal Learning Recognition | 9.84 (2.87) | 10.28 (2.46) | 9.89 (3.03) | 10.40 (3.01) |

Significant group difference (P = .031) at baseline; all other differences nonsignificant. No group differences significant in comparisons limited to children tested at both baseline and follow-up.

Neuropsychological assessments were available at the 7-month follow-up for 203 (89.4%) children in the WWSC group and 196 (86.7%) in the eAT group. Slight differences in this sample compared with that examined in the original study28 reflect our inclusion of 2 children with partial test data who were excluded from that study because of missing data for the primary outcome. Compared with the children who completed the study, those without follow-up data included proportionally more black than white participants (38 [15%] vs 16 [8%], P < .05), had lower sleep efficiency, had lower scores on NEPSY-II Inhibition Switching and NEPSY Arrows, and had higher scores on Purdue Pegboard Both Hands (Ps < .05), but none of these differences varied by group.

Group Differences in Change in Test Scores From Baseline to 7-Month Follow-Up

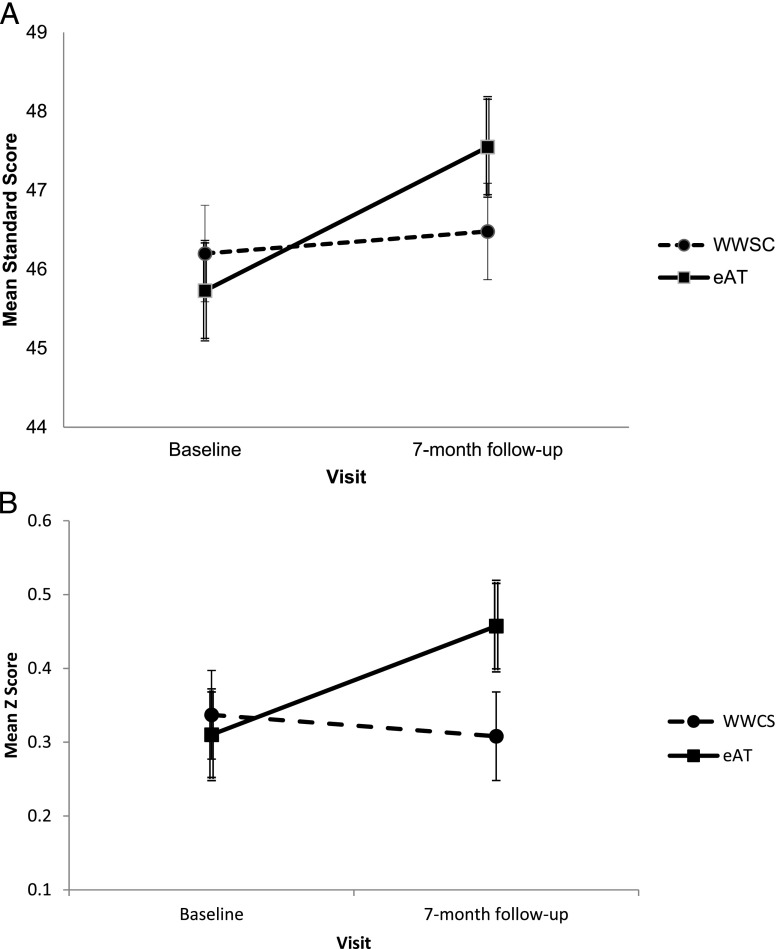

Results from the intention-to-treat analysis are presented in Table 4. Analysis revealed significant group × visit interactions for Differential Abilities Scales, 2nd edition (DAS-II) Sequential and Quantitative Reasoning and Purdue Pegboard Both Hands. Increases in both scores were larger for the eAT group than for the WWSC group, but effect sizes were small (d = 0.20 for both measures). Figure 1 depicts group differences in change on these 2 tests. When crossovers were excluded, group differences with small effect sizes were found for change on Purdue Pegboard Both Hands, unstandardized β (SE) = 0.21 (0.08), P = .013, d = 0.23, and on NEPSY Visual Attention, β (SE) = 0.65 (0.31), P = .040, d = 0.24. Additional exploratory analyses failed to reveal evidence that group differences in change varied in relation to weight status, age, or race, although children who were overweight had significantly lower scores than those not overweight on several measures (data not shown). Practice effects were suggested by significant increases in multiple scores across follow-up for both groups.

TABLE 4.

Results from Mixed Model Analysis of Group Differences in Test Scores From Baseline to 7-Mo Follow-up

| Within-Group Change, Baseline to Follow-upa | Group Difference in Changeb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WWSC | eAT | |||

| Skills Domain and Test | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | P |

| Verbal Skills | ||||

| DAS-II Word Definitions | 0.56 (0.48) | 0.51 (0.49) | −0.05 (0.69) | .942 |

| DAS-II Verbal Similaritiesc | 1.08 (0.51) | 0.65 (0.52) | −0.43 (0.73) | .557 |

| NEPSY Phonological Processing | 0.43 (0.22) | 0.19 (0.23) | −0.24 (0.32) | .443 |

| NEPSY Comprehension of Instructions | 0.13 (0.18) | 0.06 (0.18) | −0.06 (0.25) | .803 |

| NEPSY Speeded Namingc | 0.62 (0.20) | 0.71 (0.21) | 0.08 (0.29) | .773 |

| Nonverbal reasoning | ||||

| DAS-II Matrices | 0.59 (0.62) | 1.67 (0.63) | 1.08 (0.88) | .218 |

| DAS-II Sequential and Quantitative Reasoning | 0.28 (0.52) | 1.82 (0.53) | 1.54 (0.74) | .040* |

| DAS-II Pattern Constructionc | 1.29 (0.44) | 0.53 (0.45) | −0.76 (0.62) | .223 |

| DAS-II Recall of Designsc | 1.12 (0.53) | 1.23 (0.54) | 0.11 (0.76) | .889 |

| Attention and executive function | ||||

| NEPSY Visual Attention | 0.42 (0.22) | 1.02 (0.23) | 0.60 (0.32) | .061 |

| NEPSY Auditory Attention and Response Setc | 0.64 (0.16) | 0.85 (0.17) | 0.21 (0.23) | .353 |

| NEPSY Towerc | 0.74 (0.21) | 0.76 (0.22) | 0.02 (0.30) | .960 |

| NEPSY-II Inhibition, Naming | 0.30 (0.28) | 0.43 (0.29) | 0.13 (0.40) | .739 |

| NEPSY-II Inhibition, Inhibitionc | 0.66 (0.23) | 1.26 (0.24) | 0.60 (0.33) | .072 |

| NEPSY-II Inhibition, Switching | 0.57 (0.34) | 1.19 (0.34) | 0.61 (0.48) | .201 |

| NEPSY-II Word Generation, Semantic | 0.10 (0.19) | 0.17 (0.19) | 0.07 (0.27) | .797 |

| NEPSY-II Word Generation, Initial Letter | 0.33 (0.27) | 0.11 (0.29) | −0.22 (0.39) | .580 |

| Perceptual–motor and visual–spatial skills | ||||

| Purdue Pegboard Dominant Hand | 0.11 (0.07) | 0.31 (0.07) | 0.19 (0.10) | .060 |

| Purdue Pegboard Non-Dominant Handc | 0.21 (0.07) | 0.15 (0.08) | −0.06 (0.11) | .580 |

| Purdue Pegboard Both Hands | −0.03 (0.06) | 0.15 (0.06) | 0.18 (0.08) | .031* |

| Developmental Test of Visual Motor Integration | −1.20 (0.76) | −0.64 (0.77) | 0.56 (1.08) | .604 |

| NEPSY Arrows | 0.28 (0.18) | 0.01 (0.18) | −0.27 (0.25) | .280 |

| Verbal learning and memory | ||||

| WRAML2 Verbal Learningc | 0.74 (0.19) | 0.72 (0.19) | −0.02 (0.27) | .935 |

| WRAML2 Verbal Learning Recall | −0.05 (0.18) | 0.25 (0.18) | 0.30 (0.25) | .240 |

| WRAML2 Verbal Learning Recognitionc | 0.45 (0.20) | 0.45 (0.20) | 0.00 (0.28) | .992 |

β (SE) for each group is the model estimate of the adjusted mean (SE) change in standard scores (7-mo follow-up minus baseline) for that group.

β (SE) is the model estimate of the adjusted mean (SE) group difference in change in standard scores (eAT group minus WWSC group).

Standard scores increased significantly (P < .05) from baseline to 7-mo follow-up for the total sample.

P < .05 for group × visit interaction effect and small effect sizes for group differences in change (d = 0.20).

FIGURE 1.

Mean standard scores for WWSC and eAT groups on DAS-II Sequential and Quantitative Reasoning test (A) and Purdue Pegboard Both Hands (B) at baseline and 7-month follow-up. Means are estimates from mixed-model analysis. Error bars designate values within 1 SE of the means (single line bars for WWSC group, double lines for eAT group). Results from analysis revealed a significant group × visit interactions (respective Ps = .040 and .031).

Associations of Changes in Test Scores With Changes in Sleep Measures for Children in the eAT Group

Regression analysis revealed several associations of improved scores with positive changes in sleep parameters as measured by polysomnography and sleep questionnaires (Table 5). The associations were weak (partial rs −0.15 to −0.30) and had small effect sizes (f20.022–0.088). The associations tended to cluster around select tests and were evident on 2 of the 3 tests on which the eAT group made greater gains across follow-up than the WWSC group (Purdue Pegboard Non-dominant or Both Hands, NEPSY Visual Attention). Similar associations were found for DAS-II Pattern Construction, NEPSY Auditory Attention and Response Set, NEPSY-II Inhibition Naming Condition, NEPSY-II Word Generation Semantic Condition, and Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning, 2nd edition (WRAML2) Verbal Learning. Contrary to expectations, improved scores on Purdue Pegboard Non-dominant Hand were associated with increases in the arousal index, and improved scores on WRAML2 Verbal Learning Recognition were associated with decreased sleep efficiency. Findings were similar when we excluded crossovers.

TABLE 5.

Findings From Regression Analysis Indicating Significant (P < .05) Associations in eAT Group of Changes in Neuropsychological Test Scores With Changes in Sleep Measures

| Skill Domain and Test | Sleep Measures Associated With Change | β (SE) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonverbal reasoning | |||

| DAS-II Pattern Construction | Normalization of OSAS | 0.40 (0.17) | .023 |

| Percentage sleep time with end-tidal CO2 values >50 mm Hg | −0.10 (0.05) | .033 | |

| Sleep efficiency | 0.13 (0.06) | .028 | |

| Attention and executive function | |||

| NEPSY Visual Attention | PSQ-SRBD | −0.81 (0.41) | .049 |

| NEPSY Auditory Attention and Response Set | Oxygen desaturation index of ≥3% per hour of sleep | −0.15 (0.07) | .037 |

| Percentage sleep time in rapid eye movement sleep | 0.04 (0.01) | .004 | |

| NEPSY-II Inhibition, Naming | Percentage sleep time in rapid eye movement sleep | 0.03 (0.02) | .036 |

| NEPSY-II Word Generation, Initial Letter | Apnea hypopnea index | −0.38 (0.15) | .015 |

| Perceptual–motor and visual–spatial skills | |||

| Purdue Pegboard Non-dominant Hand | Arousal index | 0.39 (0.17) | .021 |

| Sleep efficiency | 0.13 (0.06) | .041 | |

| Purdue Pegboard Both Hands | Percentage sleep time with end-tidal CO2 values >50 mm Hg | −0.16 (0.05) | .002 |

| Sleep efficiency | 0.14 (0.06) | .029 | |

| Verbal learning and memory | |||

| WRAML2 Verbal Learning | Oxygen desaturation index of ≥3% per hour of sleep | −0.18 (0.08) | .023 |

| WRAML2 Verbal Learning Recall | mESS | −0.03 (0.02) | .049 |

| WRAML2 Verbal Learning Recognition | Sleep efficiency | −0.17 (0.08) | .031 |

All Ps associated with small effect size (Cohen’s f2 0.022–0.088).

Associations of Test Scores With Sleep Measures at Baseline

Regressions of baseline test scores on sleep measures for the total sample revealed 3 significant associations. Lower scores on WRAML2 Verbal Learning, DAS-II Word Definitions, and NEPSY-II Word Generation Initial Letter Condition were associated, respectively, with more sleep problems on the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire Sleep Related Breathing Disorder Scale (PSQ-SRBD), greater sleepiness on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale modified for children (mESS), and higher percentage sleep time in stage 1 sleep. These associations were also weak (partial rs −0.15 to −0.17) with small effect sizes (f2 0.021–0.025).

Discussion

The current study adds to the previous findings by suggesting small effects of AT on selective cognitive tests. Specifically, children randomly assigned to eAT made more gains than those in the WWSC group on tests of nonverbal reasoning and fine motor skills. In secondary analysis that excluded crossovers, the eAT group also made significantly greater gains on a timed measure of selective attention and visual scanning (NEPSY Visual Attention). Improvements in similar cognitive domains (fine motor coordination, nonverbal reasoning, and attention and impulse regulation) were associated with positive changes in sleep after eAT. The pattern of associations is in line with previous research suggesting that both respiratory disturbances and sleep quality contribute to cognitive functioning in OSAS.6

Cognitive weaknesses in children with OSAS are often reported in the domains of attention, executive function, and nonverbal reasoning.6,7,14,16–18 Weaknesses in motor dexterity have also been reported in children with snoring or OSAS and adults with OSAS.24,43,44 The present results offer support for small effects of treatment in these same domains. The effects of sleep disturbance on cognition and behavior have been attributed to sleepiness and to adverse effects of intermittent hypoxia and sleep fragmentation on neural development and brain functioning.6 Little is known about the effects of these processes on brain development, but frontal, subcortical, hippocampal, and cerebellar regions are especially vulnerable.7,11,17,44

Nonrandomized clinical trials of AT in children with OSAS or snoring have documented improved test performance after surgery.8,14,19,22–26 Several of these studies found greater gains on tests of attention and executive function, visual–motor and spatial skills, nonverbal reasoning, or memory in children receiving AT for OSAS compared with controls, although others have failed to document these effects.13,16 Post-AT associations between increased attention or nonverbal reasoning scores and improvements in sleep have also been reported.8,20 However, these studies are limited by their nonrandomized design, which could lead to an overestimation of effects. The current study suggests that cognitive benefits of AT over a 7-month period in children with OSAS without significant hypoxemia are probably small and selective. It is unclear whether such minor effects led to improvements in school performance or other aspects of daily functioning, but some children may have benefited more than others.

Our study failed to find any benefit of AT on tests of language, visual perceptual skills, or global cognitive ability.6 These negative findings and mean baseline scores that were comparable to normative means for age are in keeping with past evidence for average global cognitive abilities in children with OSAS.7,12,13 A relative weakness at baseline on NEPSY-II Inhibition is consistent with the vulnerability of children with OSAS to deficits in specific aspects of cognitive ability.6 However, CHAT was not designed to evaluate the effects of OSAS, and any differences between test means of CHAT participants and normative values may reflect differences in background characteristics between the participants and samples used to establish national standards.

The small effects of AT on cognitive test scores contrast with the more pronounced effects of surgery on child behavior and quality of life.27,28 One explanation for these small effects is that sleep-related cognitive weaknesses may be less evident on highly structured tests than under “free-living” conditions in which children have to regulate their own behavior according to environmental demands.45,46 Other possibilities are that the effects of chronic sleep disturbances on brain function are more difficult to reverse than responses to environmental conditions or that longer follow-up is needed to detect more substantial effects of AT on test performance.11,13,46 The tests used in this study may also be suboptimal for detecting effects of AT; measures placing greater demands on sustained attention and novel problem solving may have been more sensitive to the effects of AT.11,14,22,26,43,47 Although OSAS measures in the study were those routinely used in clinical settings and scored using rigorous approaches, alternative measures of OSAS or sleep disruption may also provide more sensitive indices of the effects of AT on sleep.7,8,16,17,20,48

A secondary aim was to explore associations of baseline test scores with baseline measures of sleep disturbance. Although several past studies failed to identify such associations in samples of children with OSAS or snoring and their controls,6,8,14,16,21,25,49 other studies report associations of a variety of indices of sleep disturbance with scores on tests of IQ, nonverbal reasoning, vigilance, executive function, and memory.13,15,17,45,50,51 In agreement with these findings, more symptoms of sleep disruption, greater sleepiness, and a greater percentage of stage 1 sleep were each associated with lower scores on 1 of the cognitive tests. Although the results must be interpreted with caution in view of small effect sizes, they accord with other reports of associations between better sleep and higher neurocognitive functioning.46

The design of CHAT conferred several methodological advantages for examining neuropsychological effects of AT and associations of test scores with sleep measures.3 OSAS was confirmed by standardized polysomnography to ensure uniformity of participant selection and quantification of sleep parameters. Because group assignment was random, potential biases in assessing neuropsychological consequences of AT were minimized. Assessing test score change across follow-up in WWSC group provided an opportunity to take effects of repeat testing into account in assessing the relationship of cognitive changes in the eAT group to changes in the sleep measures. Finally, recruitment from multiple centers yielded a large and diverse sample, and cognitive assessments were comprehensive and administered by examiners naive to group assignment.

This study has several limitations. Effect sizes were small. Moreover, we did not correct for the multiple comparisons, which accords with our exploratory approach52 but increases the risk of type I error. Findings indicating positive effects of AT on cognition thus require confirmation. Additionally, 2 unanticipated associations of increases in the eAT group’s scores across follow-up with negative changes in sleep are difficult to interpret. However, the majority of associations of changes in scores across follow-up with changes in sleep were in the expected direction and were evident for 2 of the 3 cognitive measures in which the eAT group improved more than the WWSC group. Another limitation is that the sample was restricted to children ≥5 years of age with OSAS without prolonged desaturation who were otherwise healthy.

Additional research is needed to investigate the effects of AT on academic learning and determine whether test performance is more affected for some subsets of children than for others. Study of the cognitive effects of AT in children <5 years of age and in those with more severe desaturation or comorbid conditions is likewise warranted. Another important research goal is to identify the types of cognitive skills most affected by AT. The findings suggest that tests of novel problem solving, attention, and motor dexterity are worthy of consideration in future trials. However, future studies might examine ways to increase test sensitivity by assessing speed of decision-making, lengthening tasks, or imposing greater demands on inhibitory control.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that, on average, AT confers small positive effects on cognitive test scores in children with OSAS without prolonged desaturation and with overall average cognitive functioning. The results provide impetus for more research on the cognitive and neurobiological effects of AT for pediatric OSAS.5,10,29,44 The findings are also consistent with previous research suggesting that tests of nonverbal reasoning, attention, and fine motor skills are selectively affected by OSAS and thus more likely to improve after AT.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their collaborators on the CHAT. Appreciation is also extended to participating families and the members of the data and safety monitoring board. We also acknowledge the assistance of Nori Minich and CHAT research staff.

Glossary

- AT

adenotonsillectomy

- CHAT

Childhood Adenotonsillectomy Trial

- DAS-II

Differential Abilities Scales, 2nd edition

- eAT

early adenotonsillectomy

- mESS

Epworth Sleepiness Scale modified for children

- NEPSY

A Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment

- NEPSY-II

NEPSY 2nd edition

- OSAS

obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- PSQ-SRBD

Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire Sleep Related Breathing Disorder Scale

- WRAML2

Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning, 2nd edition

- WWSC

watchful waiting with supportive care

Footnotes

Dr Taylor contributed to the study design, oversight of neurobehavioral data collection, and analysis and interpretation of the data, developed the proposal for this manuscript, and drafted and edited the manuscript; Dr Bowen developed the proposal for this manuscript, participated in analysis and interpretation of the data, and helped draft and edit the manuscript; Drs Beebe, Hodges, Thomas, and Giordani contributed to the study design and proposal for this manuscript, oversight of neurobehavioral data collection, and interpretation of the data and edited the manuscript; Drs Amin, Chervin, Garetz, Rosen, Marcus, and Ellenberg contributed to the study design, oversight of data collection, and interpretation of the data and edited the manuscript; Drs Arens, Katz, Muzumdar, and Paruthi participated in oversight of data collection and interpretation of the data and edited the manuscript; Drs Moore and Morales developed the proposal for this manuscript, participated in analysis and interpretation of the data, and edited the manuscript; Drs Sadhwani and Ware contributed to the proposal for this study, oversight of neurobehavioral data collection, and interpretation of the data and edited the manuscript; Dr Redline designed the study, participated in the interpretation of the data, and edited the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

This trial has been registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT00560859).

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: Dr Chervin is named in or has developed patented and copyrighted materials owned by the University of Michigan and designed to assist with assessment or treatment of sleep disorders; these materials include the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire Sleep-Related Breathing Disorder scale, used in the research reported here. This questionnaire is licensed online by the University of Michigan to appropriate users at no charge and (for electronic use) to Zansors. The other authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Funded by grants HL083075, HL083129, UL1RR024134, UL1TR000003, and UL1RR024989 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: Dr Carol Rosen has consulted for Natus, Advance–Medical and is a consultant for Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Relevant to this work, Dr Chervin is named in or has developed patented and copyrighted materials owned by the University of Michigan and designed to assist with assessment or treatment of sleep disorders. These materials include the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire Sleep-Related Breathing Related Disorder scale, used in the research reported here. Dr Chervin serves on the boards of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the International Pediatric Sleep Society, is an editor for UpToDate, has edited a book for Cambridge University Press, has received support for research and education from Philips Respironics and Fisher Paykel, and has consulted for MC3 and Zansors. The other authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interests to disclose.

References

- 1.American Thoracic Society Standard and indications for cardiopulmonary sleep studies in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:866–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garetz SL. Behavior, cognition, and quality of life after adenotonsillectomy for pediatric sleep-disordered breathing: summary of the literature. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138(1 suppl):S19–S26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcus CL, Brooks LJ, Draper KA, et al. ; American Academy of Pediatrics . Diagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):576–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redline S, Amin R, Beebe D, et al. The Childhood Adenotonsillectomy Trial (CHAT): rationale, design, and challenges of a randomized controlled trial evaluating a standard surgical procedure in a pediatric population. Sleep. 2011;34(11):1509–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amin R, Somers VK, McConnell K, et al. Activity-adjusted 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure and cardiac remodeling in children with sleep disordered breathing. Hypertension. 2008;51(1):84–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beebe DW. Neurobehavioral morbidity associated with disordered breathing during sleep in children: a comprehensive review. Sleep. 2006;29(9):1115–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beebe DW, Wells CT, Jeffries J, Chini B, Kalra M, Amin R. Neuropsychological effects of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10(7):962–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chervin RD, Ruzicka DL, Giordani BJ, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, behavior, and cognition in children before and after adenotonsillectomy. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/117/4/e769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottlieb DJ, Chase C, Vezina RM, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing symptoms are associated with poorer cognitive function in 5-year-old children. J Pediatr. 2004;145(4):458–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gozal D, O’Brien LM. Snoring and obstructive sleep apnoea in children: why should we treat? Paediatr Respir Rev. 2004;5(suppl A):S371–S376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halbower AC, Mahone EM. Neuropsychological morbidity linked to childhood sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10(2):97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beebe DW, Ris MD, Kramer ME, Long E, Amin R. The association between sleep disordered breathing, academic grades, and cognitive and behavioral functioning among overweight subjects during middle to late childhood. Sleep. 2010;33(11):1447–1456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackman AR, Biggs SN, Walter LM, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in preschool children is associated with behavioral, but not cognitive, impairments. Sleep Med. 2012;13(6):621–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman B-C, Hendeles-Amitai A, Kozminsky E, et al. Adenotonsillectomy improves neurocognitive function in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 2003;26(8):999–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaemingk KL, Pasvogel AE, Goodwin JL, et al. Learning in children and sleep disordered breathing: findings of the Tucson Children’s Assessment of Sleep Apnea (tuCASA) prospective cohort study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2003;9(7):1016–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohler MJ, Lushington K, van den Heuvel CJ, Martin J, Pamula Y, Kennedy D. Adenotonsillectomy and neurocognitive deficits in children with sleep disordered breathing. PLoS One. 2009;4(10):e7343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewin DS, Rosen RC, England SJ, Dahl RE. Preliminary evidence of behavioral and cognitive sequelae of obstructive sleep apnea in children. Sleep Med. 2002;3(1):5–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Brien LM, Mervis CB, Holbrook CR, et al. Neurobehavioral correlates of sleep-disordered breathing in children. J Sleep Res. 2004;13(2):165–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali NJ, Pitson D, Stradling JR. Sleep disordered breathing: effects of adenotonsillectomy on behaviour and psychological functioning. Eur J Pediatr. 1996;155(1):56–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biggs SN, Vlahandonis A, Anderson V, et al. Long-term changes in neurocognition and behavior following treatment of sleep disordered breathing in school-aged children. Sleep. 2014;37(1):77–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chervin RD, Garetz SL, Ruzicka DL, et al. Do respiratory cycle-related EEG changes or arousals from sleep predict neurobehavioral deficits and response to adenotonsillectomy in children? J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(8):903–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galland BC, Dawes PJ, Tripp EG, Taylor BJ. Changes in behavior and attentional capacity after adenotonsillectomy. Pediatr Res. 2006;59(5):711–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giordani B, Hodges EK, Guire KE, et al. Changes in neuropsychological and behavioral functioning in children with and without obstructive sleep apnea following tonsillectomy. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2012;18(2):212–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landau YE, Bar-Yishay O, Greenberg-Dotan S, Goldbart AD, Tarasiuk A, Tal A. Impaired behavioral and neurocognitive function in preschool children with obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47(2):180–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H-Y, Huang Y-S, Chen N-H, Fang T-J, Lee L-A. Impact of adenotonsillectomy on behavior in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(7):1142–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montgomery-Downs HE, Crabtree VM, Gozal D. Cognition, sleep and respiration in at-risk children treated for obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2005;25(2):336–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garetz SL, Mitchell RB, Parker PD, et al. Quality of life and obstructive sleep apnea symptoms after pediatric adenotonsillectomy. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/135/2/e477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcus CL, Moore RH, Rosen CL, et al. ; Childhood Adenotonsillectomy Trial (CHAT) . A randomized trial of adenotonsillectomy for childhood sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2366–2376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosen CL, Wang R, Taylor HG, et al. Utility of symptoms to predict treatment outcomes in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/135/3/e662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halbower AC, Degaonkar M, Barker PB, et al. Childhood obstructive sleep apnea associates with neuropsychological deficits and neuronal brain injury. PLoS Med. 2006;3(8):e301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldstein NA, Fatima M, Campbell TF, Rosenfeld RM. Child behavior and quality of life before and after tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128(7):770–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chervin RD, Hedger K, Dillon JE, Pituch KJ. Pediatric sleep questionnaire (PSQ): validity and reliability of scales for sleep-disordered breathing, snoring, sleepiness, and behavioral problems. Sleep Med. 2000;1(1):21–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franco RA Jr, Rosenfeld RM, Rao M. First place: resident clinical science award 1999. Quality of life for children with obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123(1 Pt 1):9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melendres MC, Lutz JM, Rubin ED, Marcus CL. Daytime sleepiness and hyperactivity in children with suspected sleep-disordered breathing. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):768–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elliott CD. Differential Ability Scales–II (DAS-II). New York, NY: Psychological Corporation; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korkman N, Kirk U, Kemp S. NEPSY: A Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment Manual. New York, NY: Psychological Corporation; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korkman M, Kirk U, Kemp S. NEPSY-II. Administrative Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gardner R. The Objective Diagnosis of Minimal Brain Dysfunction. Cresskill, NJ: Creative Therapies; 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baron IS. Neuropsychological Evaluation of the Child. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beery KE, Buktenica NA, Beery NA. Beery–Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual–Motor Integration. 5th ed. North Tonawanda, NY: MHS Psychological Assessments; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheslow D, Adams W. Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning. 2nd ed Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beebe DW, Groesz L, Wells C, Nichols A, McGee K. The neuropsychological effects of obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis of norm-referenced and case-controlled data. Sleep. 2003;26(3):298–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yaouhi K, Bertran F, Clochon P, et al. A combined neuropsychological and brain imaging study of obstructive sleep apnea. J Sleep Res. 2009;18(1):36–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anderson B, Storfer-Isser A, Taylor HG, Rosen CL, Redline S. Associations of executive function with sleepiness and sleep duration in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/123/4/e701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beebe DW. A brief primer on sleep for pediatric and child clinical neuropsychologists. Child Neuropsychol. 2012;18(4):313–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Avior G, Fishman G, Leor A, Sivan Y, Kaysar N, Derowe A. The effect of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy on inattention and impulsivity as measured by the Test of Variables of Attention (TOVA) in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131(4):367–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chervin RD, Ruzicka DL, Hoban TF, et al. Esophageal pressures, polysomnography, and neurobehavioral outcomes of adenotonsillectomy in children. Chest. 2012;142(1):101–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kohler MJ, Lushington K, Kennedy JD. Neurocognitive performance and behavior before and after treatment for sleep-disordered breathing in children. Nat Sci Sleep. 2010;2:159–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Brien LM, Holbrook CR, Mervis CB, et al. Sleep and neurobehavioral characteristics of 5- to 7-year-old children with parentally reported symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):554–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Emancipator JL, Storfer-Isser A, Taylor HG, et al. Variation of cognition and achievement with sleep-disordered breathing in full-term and preterm children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(2):203–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gosho M, Nagashima K, Sato Y. Study designs and statistical analyses for biomarker research. Sensors (Basel). 2012;12(7):8966–8986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]