Abstract

The purpose of this study was to describe the components and use of motivational interviewing (MI) within a behavior change intervention to promote healthful eating and family meals and prevent childhood obesity. The Healthy Home Offerings via the Mealtime Environment (HOME) Plus intervention was part of a two-arm randomized-controlled trial and included 81 families (8–12 year old children and their parents) in the intervention condition. The intervention included 10 monthly, 2-hour group sessions and 5 bimonthly motivational/goal-setting phone calls. Data were collected for intervention families only at each of the goal-setting calls and a behavior change assessment was administered at the 10th/final group session. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the MI call data and behavior assessment. Overall group attendance was high (68% attending > 7 sessions). Motivational/goal-setting phone calls were well accepted, with an 87% average completion rate. More than 85% of the time, families reported meeting their chosen goal between calls. Families completing the behavioral assessment reported the most change in having family meals more often and improving home food healthfulness. Researchers should use a combination of delivery methods using MI when implementing behavior change programs for families to promote goal setting and healthful eating within pediatric obesity interventions.

Keywords: intervention, behavior change, nutrition, obesity prevention, Motivational Interviewing, family

Introduction

Dietary guidelines (U.S. Department of Agriculture & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010) are created for the general public to help consumers apply healthful eating recommendations. However, it is unknown whether this approach is effective in positively changing behaviors. Public health interventions aim to deliver programs that achieve identifiable results on a large scale (Rychetnik, Hawe, Waters, Barratt, & Frommer, 2004). More specifically, public health nutrition interventions commonly deliver healthful eating messages with the expectation of changing behaviors (Brug, Oenema, & Ferreira, 2005). Public health interventions, which typically aim to be cost-effective (Owen et al., 2012), generally utilize a common approach and may not address individual needs for behavior change. To achieve positive health outcomes, it is imperative to implement behavioral messages that have been shown to change behavior (Paineau et al., 2010) and do so in an efficacious manner.

Achieving positive health outcomes can be accomplished with behavior change; however, the process of behavior change and maintaining change is often a difficult task for children and adults alike (King, 2007). Large behavior change goals can appear unachievable while small behavior change goals are more manageable for most individuals (Golay et al., 2013). Several studies have shown small, beneficial, health-related changes at the family and individual levels. Families who made small changes in dietary intake experienced outcomes that closely mimicked the recommended dietary guidelines (Paineau et al., 2010). Adults who experienced small weight loss saw reduced risk of developing diabetes and improvements in blood pressure and blood lipids (Golay et al., 2013). Furthermore, adults participating in a behavior change intervention with motivational interviewing saw positive changes in overall body weight, body mass index, waist circumference and total energy intake when they self-selected small lifestyle goals (Paxman, Hall, Harden, O’Keeffe, & Simper, 2011). Similarly for children, small behavior changes such as reducing portion sizes and increasing activity levels can have positive impacts on health outcomes (Hill, Wyatt, Reed, & Peters, 2003).

Interventions incorporating a variety of modifiable behaviors such as healthful eating and physical activity, particularly with a focus on the entire family, have been shown to be more effective in obesity prevention (Golley, Hendrie, Slater, & Corsini, 2011) and in improving dietary intake (Ritchie, Welk, Styne, Gerstein, & Crawford, 2005) compared to interventions that do not. Yet understanding the mechanism of how intervention components (e.g., group, individual) contribute to behavior change is in its infancy (Martin, Chater, & Lorencatto, 2013). Incorporating combinations of behavior change techniques and parental and familial involvement (van der Kruk, Kortekaas, Lucas, & Jager-Wittenaar, 2013) in obesity prevention can yield higher success in positive behavioral changes among youth. Furthermore, the literature could benefit from knowing how to better support parents in behavior change for their families (Golley et al., 2011).

In addition to multiple behavior components, interventions that are designed to meet the needs of targeted populations are more effective in accomplishing change (Baranowski, Cerin, & Baranowski, 2009). Previous research supports interventions that extend beyond information delivery and include an individualized, tailored approach that incorporates behavior change strategies. This approach may be necessary for behavior change (Golley et al., 2011; Neumark-Sztainer, Story, Hannan, & Rex, 2003) and has been shown to be effective in increasing fruit and vegetable intake and decreasing fat and sugar intake in both parents and children (Epstein et al., 2001), and increasing active play time and children’s water consumption (McGarvey et al., 2004). Describing a multicomponent intervention that includes in-person group sessions for the whole family supplemented with individual, tailored phone calls with parents can add to the understanding of how family-focused intervention programs promote behavior change.

Motivational interviewing (MI) offers a unique counseling style and opportunity to tailor information to promote behavior change in public health-focused intervention trials. MI has been shown to be effective for addictive behaviors, smoking cessation, and health behaviors (e.g., nutrition and physical activity) in a variety of settings (Hecht et al., 2005: Lundahl, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson, & Burke, 2010). MI is a focused, directive, and client-centered counseling style that elicits behavior change by assisting individuals in exploring and resolving their ambivalence (Miller & Rollnick, 1991). This counseling style aims to increase an individual’s self-efficacy in making behavior change(s).

More recently, MI has shown positive results in weight loss efforts across populations (Christie & Channon, 2013) and has had successful outcomes across the lifespan (Flattum, Friend, Neumark-Sztainer, & Story, 2009; Meybodi, Pourshrifi, Dastbaravarde, Rostami, & Saeedi, 2011; Wong & Cheng, 2013). Recent studies suggest that MI is effective even by telephone. When cancer survivors received phone calls from trained motivational interviewers regarding a healthy lifestyle, coping and stress management, those who received MI significantly lowered their levels of stress and significantly increased their daily servings of fruits and vegetables compared to those who did not receive MI (Garrett et al., 2013). Furthermore, overweight veterans who participated in a small-change, phone-based weight loss intervention had significant reductions in body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference, and significant increases in their daily intake of fruits and vegetables (Damschroder, Lutes, Goodrich, Gillon, & Lowery, 2010). Servings of fruits and vegetables were also significantly increased in a group of adults who participated in a randomized, multi-component behavior change intervention where they received phone counseling that augmented mailed materials compared to a group who received printed materials (Kim et al., 2010).

The purpose of this article is to briefly describe how motivational interviewing can be used to support parents to facilitate health behavior change, particularly around healthy eating, family meals, and obesity prevention, using data from a family-based program. The multi-component program was delivered in group sessions with multiple families with 8–12 year old children, as well as with individual, motivational/goal-setting phone calls with parents. The program targeted three main behavioral objectives aimed to positively change behavior. Each behavioral objective encompassed several specific behavioral goals, which are described in detail in Table 1. This article describes:

Table 1.

HOME Plus behavioral objectives and corresponding behavioral goals.

| Behavioral Objectives | Behavioral Goalsa |

|---|---|

| 1. Plan healthy meals and snacks with your family more often |

|

| 2. Have meals with your family at home more often |

|

| 3. Improve the healthfulness of the food available at home |

|

Note.

Behavioral goals from behavior change assessment worksheet

How motivational interviewing techniques were successfully used in a family-focused health promotion program as part of goal-setting phone calls with parents to augment group family sessions.

Parent’s behavioral goal selections during motivational/goalsetting phone calls.

Families’ report of behavioral goals at the end of the intervention program where they rated the goal as one in which they definitely made changes or that they still need to keep working on; they also identified goals they focused on most during the intervention.

The similarities and differences between the parent-selected goals and the family’s report of behavioral changes.

Methods

HOME Plus Study

Healthy Home Offerings via the Mealtime Environment (HOME) Plus is a family-focused, community-based, randomized controlled trial to prevent childhood obesity. The HOME Plus intervention was developed through initial pilot testing and as an active, hands-on prevention program that utilizes the role of family in the initiation, support and reinforcement of health behaviors. Social Cognitive Theory and a socioecological framework were used to guide the framework for the intervention to address personal, behavioral, and environmental factors associated with healthy behaviors for families. Intervention programs based on theory have been identified as an acceptable way to proceed in the promotion of healthy habits, including diet (Brug et al., 2005).

HOME Plus aims to reduce obesity by increasing the frequency of family meals and the amount of healthful foods and beverages available in the home environment, improving the healthfulness of children’s food and beverage intakes, and reducing children’s sedentary behavior, particularly screen time. The study has been described in further detail elsewhere (Fulkerson et al., 2014).

Families (n=160) were recruited to participate in the HOME Plus study. Data collection participants included the main meal-preparing parent and a child 8–12 years old. Families were ineligible to participate if they did not speak English, if they had food allergies, or if the child’s age- and gender-adjusted BMI percentile was below the 50th percentile per Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines (http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/; accessed May 2014). Under the circumstance where a family had more than one child that met the eligibility criteria, the participating parent chose the child they felt would have the most interest participating in the study. Families randomized to the control group (n=79) received 10-monthly newsletters. Families randomized to the HOME Plus intervention (n=81) were to attend 10-monthly group sessions (October–July). In addition to the group sessions, the primary meal-preparing parent from intervention families received five motivational/goal-setting phone calls – following sessions 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9 – to provide individual support in meeting the intervention behavioral objectives. The objectives of the program targeted behaviors predictive of obesity prevention (Baranowski et al., 2009; Kamath et al., 2008; Summerbell et al., 2005) and included specific goals to support each objective. Participating families focused on three overarching behavioral objectives: 1) plan healthy meals and snacks with your family more often, 2) have meals with your family at home more often, and 3) improve the healthfulness of the food available at home. Table 1 lists the behavioral objectives and the corresponding family-level behavioral goals.

Intervention Participants

Of the 81 parent-child dyads randomized to the intervention, parent participants were primarily mothers/female guardians (n=76, 94%) and white/Caucasian (n=63, 78%) with a mean age of 41.3 (SD= 7.99) years. Child participants were primarily white/Caucasian (n=56, 69%) with slightly more boys than girls (n=43, 53% vs. n=38, 47%) and mean age of 10.5 years (SD= 1.45). More than one-third (36%) of families had an annual household income less than $35,000, 20% had an annual income between $35,000 and $74,000, and 44% of families had an annual income of $75,000 or more. Almost half of the families (45%) reported receipt of economic assistance (free and/or reduced priced lunch for children or public assistance). More than half of parents had a bachelor’s degree or higher (62%).

Group Sessions

The HOME Plus program was implemented at local Park and Recreation Centers in Minneapolis, Minnesota. All family members living in the home were invited to attend monthly sessions. Each month consisted of a different healthful eating topic and allowed for hands-on cooking for the entire family. The same session was offered several times per month at each site to allow flexibility for families with busy schedules. Session attendance was high, with 68% of families attended ≥7 sessions. Details of the HOME Plus intervention are described elsewhere (Flattum, et al., 2015).

Motivational/goal-setting phone calls

To supplement the topics delivered in the monthly group sessions, the participating parent received five motivational/goal-setting phone calls (referred to as phone calls hereafter). Phone calls utilized MI principles and were conducted by the session facilitators, who are registered dietitians and trained in MI. The focus of the phone calls was to discuss family health behavior goals, build one-on-one rapport outside the group session, and support the participating parent to explore and resolve ambivalence around the HOME Plus behavioral objectives. During the initial phone call, the parent selected a family-level goal to focus on during the study or over the next few months. The selected goal was categorized into one of the three HOME Plus behavioral objectives described earlier (and in Table 1). Each phone call built on the previous phone discussion. If a parent reported that his or her family felt they successfully made a behavior change and achieved maintenance with their initial goal, the parent selected a new goal. Utilizing the Stages of Change Model (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997), families were considered in maintenance stage if they reported making a behavior change around the family-level goal they selected during their initial phone call and sustaining the behavior for the period of time between phone calls. Families who reported making a behavior change but had not achieved maintenance continued to work on their initial goal. Phone calls occurred approximately 2 months apart to allow time for families to work on their goal. All intervention families could participate in calls regardless of their attendance at group sessions, as they were not dependent on session attendance.

MI techniques were used during the phone calls, as this allowed for a shift in focus from giving information, advice, and behavior change prescriptions to helping the participant explore reasons, ideas, and strategies for change. Rather than the facilitator choosing a goal as in traditional counseling sessions, participants were encouraged to choose a goal or behavior they would like to work on and express their readiness to change, as well as benefits and barriers to achieving this change. The HOME Plus facilitator guided the participant in thinking of strategies to overcome barriers and set realistic goals while understanding that not all participants were ready to change. Facilitators utilized Resnicow and McMaster’s framework to transition participants from motivation to goal setting (Resnicow & McMaster, 2012). Conducting MI over the phone allowed for less participant burden, was more cost-effective, and provided scheduling flexibility for participants and facilitators. After each phone call, the facilitator completed a standardized form in an online participant database (Harris et al., 2009). The form included the length of the conversation, whether the previously selected goal was met, whether a new goal was set, the participants’ barriers to meeting the goal, and action plan. Goals were entered into the participant database as one of the three main behavioral objectives.

Family-Related Behavior Change Assessment

At the 10th and final in-person group session, families (i.e., parents and children together) completed a family reflection behavior change measure worksheet to assess their behavior changes throughout the intervention program. Families rated change for each behavior on a scale of 0–10 (0=need to keep working on, 10=definitely made changes). They were asked to place a mark by the three behavioral goals they focused on the most during the program and describe how their family will continue these changes on their own outside of the program. Each behavior on the assessment fell under one of the three main behavioral objectives of the HOME Plus intervention. The worksheet data were subsequently entered into the participant database.

Analysis

Data from the phone calls and behavior change assessment were analyzed for families who attended the tenth and final group session (n=57 of 81; 70%). Qualitative data from the motivational/goal-setting phone calls, including selected goals and barriers to reaching and achieving goals, were categorized by the facilitators who conducted the phone calls into one of the three HOME Plus behavioral objectives. Quantitative data were analyzed to determine counts, frequencies and means. For analysis, goals selected during phone calls were averaged over the five phone calls to indicate frequency of goal selection by behavioral objective. To examine behavior change on the behavior change assessment form, categories were collapsed and reported as follows: 0–3: need to keep working on, 8–10: definitely made changes.

Results

Motivational/goal-setting phone calls

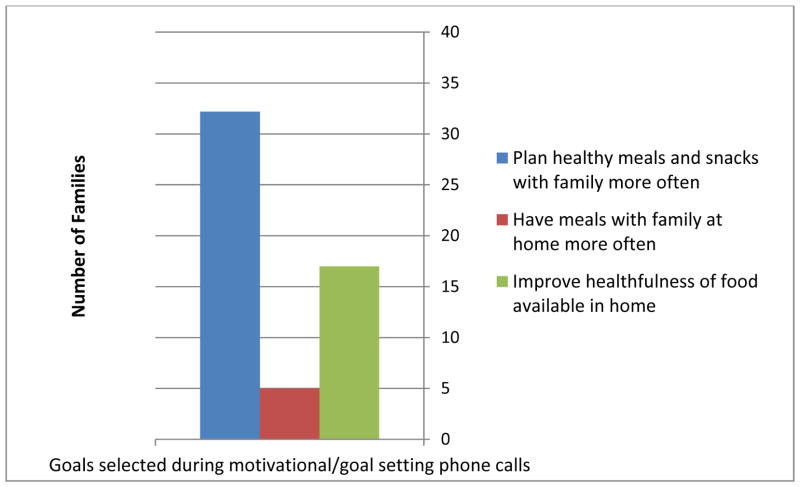

Phone calls were well accepted by all intervention parents with an 87% average completion rate; 84% (n=68) of all intervention families completed at least four of the five calls. Of the 57 families who attended the final group session, 96% completed at least four phone calls. On average, phone calls lasted 10–20 minutes in length. Figure 1 presents the frequency of the overarching behavioral objectives that align with the goals selected by parents across the five calls. On average over the course of the intervention, 32 families selected to work on planning healthful meals and snacks, 17 selected to improve the healthfulness of foods available in the home and 5 selected to have family meals more often. More than one-third of families (37%) achieved their initial goal with maintenance and selected a second goal for future focus. More than 85% of the time, families reported meeting their chosen goal between calls, although not all families reported maintenance, and therefore did not necessarily choose another goal.

Figure 1.

Frequency of overarching behavioral objectives selected by parents across five motivational/goal-setting phone calls as part of the HOME Plus intervention (n=57)

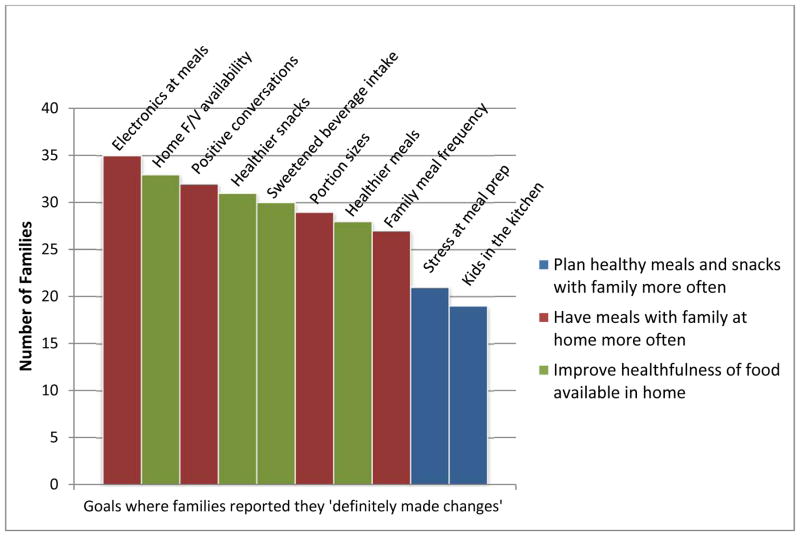

Behavior Change Assessment

In total, 57 (70%) families completed the behavior change assessment at the last in-person session. Figure 2 shows the frequency of goals in which families felt they definitely made changes (color coded by the overarching program behavioral objectives). The most commonly selected goals were categorized under the following behavioral objectives: “Have meals with family at home more often” (red on Figure 2) and “Improve the healthfulness of food available in home” (green on Figure 2). Examples of these behaviors include (in order of frequency from highest to lowest), decreasing electronics at meals (n=35), increasing the amount of fruits and vegetables at home and served at mealtime (n=33), and promoting positive conversations at meals (n=32). Goals categorized under the overarching behavioral objective, “Plan healthy meals and snacks with your family more often” (blue on Figure 2) were those rated least often as definitely made changes. Examples of these behaviors include reducing stress around meal preparation (n=21) and kids in our family are helping out in the kitchen (n=19).

Figure 2.

Frequency of HOME Plus behavioral goals where families (n=57) reported they “definitely made changes” by behavioral objective. Behavioral Goals: Electronics at meals = We have decreased the use of electronics at meals. Home F/V availability = We have increased the amount of fruits and vegetables at home or that are served at meal time. Positive conversations = We promote positive conversations at meal time. Healthier snacks = Our snacks have gotten healthier and include more fruits and vegetables. Sweetened beverage intake = We have decreased the amount of sweetened beverages we drink. Portion sizes = We have cut down on portion sizes and/or the amount of food we eat. Healthier meals = Our meals have gotten healthier. Family meal frequency = We have increased the number of family meals in our home. Stress at meal prep = We have less stress around meal preparation. Kids in the kitchen = The kids in our family are helping out in the kitchen

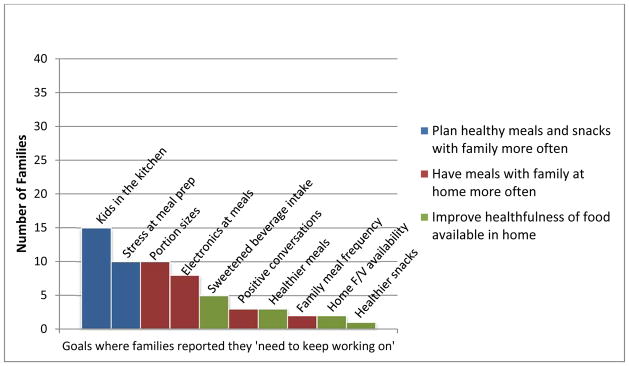

Inversely, it is important to understand the behavioral objectives families reported as needing the most work (i.e., those rated as need to keep working on). As shown in Figure 3, goals rated as those that they need to keep working on were categorized under the overarching behavioral objective, “Plan healthy meals and snacks with your family more often” and included kids helping in the kitchen (n=15) and reducing stress around meal preparation (n=10). Decreasing portion sizes (n=10) was another goal commonly rated as need to keep working on by families.

Figure 3.

Frequency of HOME Plus behavioral goals where families (n=57) reported they “need to keep working on” by behavioral objective. Behavioral goals: Kids in the kitchen = The kids in our family are helping out in the kitchen. Stress at meal prep = We have less stress around meal preparation. Portion sizes = We have cut down on portion sizes and/or the amount of food we eat. Electronics at meals = We have decreased the use of electronics at meals. Sweetened beverage intake = We have decreased the amount of sweetened beverages we drink. Positive conversations = We promote positive conversations at meal time. Healthier meals = Our meals have gotten healthier. Family meal frequency = We have increased the number of family meals in our home. Home F/V availability = We have increased the amount of fruits and vegetables at home or that are served at meal time. Healthier snacks = Our snacks have gotten healthier and include more fruits and vegetables.

Behaviors that families reported focusing on the most included increasing the amount of fruits and vegetables at home and served at mealtime (n=28), cutting down on portion sizes (n=24), and snacks have gotten healthier and include more fruits and vegetables (n=23). There was no consistent pattern observed based on the overarching behavioral objectives for these ratings.

Discussion

This article aimed to describe behavioral goal setting during in-person group sessions for whole families and individual motivational/goal-setting phone calls with individual parents as part of a multi-component, family-focused, community-based obesity prevention intervention. In addition, the article described how motivational interviewing techniques can be used over the phone in a family-focused program to set and work on family-level behavioral goals. This article further describes similarities and differences between the parent-selected goals during phone calls and the family’s report of behavioral changes throughout the intervention.

The study suggests that the combined intervention delivery of in-person group sessions and individual phone calls is feasible and effective for family goal selection and behavior change. Overall attendance at group sessions was high and phone calls were well accepted by participating parents. Previous research suggests that a parent’s success in achieving behavior change positively correlates to a child’s success (Sonneville et al., 2012). Furthermore, group sessions, which focused on different monthly topics, allowed families to apply motivation to different behaviors throughout the program, while the individual phone calls assisted parents in setting goals that were reasonable and specific to their family. This combined delivery allowed for a tailored intervention approach that differs from most community-based interventions that utilize a “one size fits all” methodology. This innovative intervention approach was successful in utilizing the process of behavior change which has been shown to produce positive behavior changes (Golley et al., 2011).

It is apparent that the goals on the behavior change assessment form where families reported definitely making changes differed from the goals parents chose to discuss and work on during individual phone calls. We speculate that this occurred for a variety of reasons. First, specific behaviors where families focus and report making changes may indicate this specific behavior was one they were already doing well, a behavior where they felt they did not need improvement, or it was one that had consensus among family members. Second, parents who feel confident their current behaviors are healthful may choose to focus more intently on behaviors that are more difficult to change and require more effort and support (i.e., from the phone calls). Third, families that actively select a behavior change goal may select a behavior that clearly needs improvement and make significant improvements, as was done successfully by participants in a study by Estabrooks and colleagues (Estabrooks et al., 2005). Finally, the behaviors families reported as changing the most over the intervention period could be behaviors the family viewed as “easier” to accomplish since less dedication is required to achieve easy goals (Locke, 1996). For example, reducing electronics at meals, increasing fruits and vegetables, and promoting positive conversation at meals may be easier goals for parents to implement and gauge their success. The ease of implementation of the goals where families made changes may be due to the clear message/guideline of the goal as delivered during intervention sessions. Reducing electronics commonly translates to turning off the television during meals, whereas “having the kids in the kitchen more often” (a goal selected less frequently) is not as clearly operationalized.

Behavioral goals where families reported more work was needed were similar to the self-selected goals made during the phone calls. Parents utilized the individual phone time with facilitators to focus on behaviors they found most difficult to change on their own without support and guidance. Examples of these behaviors include “having less stress around meal preparation” and “having kids help in the kitchen more often.” Parents were able to explore avenues of behavior change and discuss advantages and disadvantages of change, which was guided by MI techniques. The occurrence of phone calls gave families an opportunity to make behavior changes and revisit the goal for further support. Behavior changes, even small, occur over time and it is likely that the goals families needed to keep working on require more time and the length of the intervention was not long enough for families to feel they made changes with these specific behaviors.

The phone calls utilizing MI proved to be an effective counseling style to promote healthful behavior changes for families in the HOME Plus study. Throughout the duration of the intervention, many families reported accomplishing their initial goal, prompting them to select a second goal of focus. For parents who reported continuing to work on their initial goal, several reported achieving success or making progress during their calls. Our study adds to previous research that has found MI to be effective when delivered over the phone (Garrett et al., 2013) and in changing family behaviors (Woo Baidal et al., 2013). MI was successfully implemented during the phone call component of the HOME Plus intervention and participants reported enjoying the calls.

The HOME Plus study had limitations and strengths. The present sample size was small and limited to only participants who attended the final intervention session. We speculate that had all families participating in the HOME Plus intervention attended the last session there may have been a greater variation in behavior change responses. However, 70% of HOME Plus intervention families attended the final session and this represents the majority of participants, since the average session attendance was 68%. Also, report bias may exist in our data since families reported on their own behavior changes. Finally, families who consented to participate in the study may have been more motivated to make behavior changes around family meals and healthful eating compared to families who did not participate. Despite these limitations, our report is unique in that it describes the combined approach of using in-person sessions supplemented with individual motivational/goal-setting phone calls with parents in a family-based health promotion program. This description adds to the literature by showing how MI techniques can be used for phone-based goal setting in health promotion trials. In the HOME Plus study, group sessions allowed for a wide array of public health topics to be covered for a large number of people and provide an opportunity for parents to discuss and learn from one another. The individual, phone component with parents was specifically tailored to each family and allowed parents to explore opportunities to accomplish goals in a nonjudgmental and more private setting. The motivational/goal-setting phone calls were also convenient for parents who were unable to attend the group sessions.

Conclusions and Implications

The feasible and successful combination of group and individualized goal setting using motivational interviewing strategies described as part of the HOME Plus study is promising for future health promotion interventions. The combination of an in-person, group delivery intervention with individual motivational/goal-setting phone calls was effective in having families’ self-select and meet goals. This study provides an enhanced understanding of the active ingredients of behavior change programs. Future intervention programs are encouraged to utilize a double method (group and individual) intervention, knowing that goals and behaviors that are more easily attainable, and therefore positively affect behavior change, may differ by delivery method. Our results can guide researchers developing family-focused and community-based obesity prevention programs to improve behavior change outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the parents and children participating in the study, the students and volunteers from the University of Minnesota, School of Nursing, and Melissa Horning and Kayla Dean for their assistance with the article.

Funding

The work was supported by grant R01DK08400 by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Software support was provided by the University of Minnesota’s Clinical and Translation Science Institute (grant 1UL1RR033183) from the National center for Research Resources (NCRR) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The HOME Plus trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT01538615).

Contributor Information

Michelle Draxten, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota.

Colleen Flattum, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota.

Jayne Fulkerson, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota.

References

- Baranowski T, Cerin E, Baranowski J. Steps in the design, development and formative evaluation of obesity prevention-related behavior change trials. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2009;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brug J, Oenema A, Ferreira I. Theory, evidence and intervention mapping to improve behavior nutrition and physical activity interventions. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2005;2 doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-2-2. 2-5868-2-2. 1479-5868-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie D, Channon S. The potential for motivational interviewing to improve outcomes in the management of diabetes and obesity in paediatric and adult populations: A clinical review. Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism. 2013;16:381–7. doi: 10.1111/dom.12195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Lutes LD, Goodrich DE, Gillon L, Lowery JC. A small-change approach delivered via telephone promotes weight loss in veterans: Results from the ASPIRE-VA pilot study. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;79:262–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Gordy CC, Raynor HA, Beddome M, Kilanowski CK, Paluch R. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake and decreasing fat and sugar intake in families at risk for childhood obesity. Obesity Research. 2001;9:171–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks PA, Nelson CC, Xu S, King D, Bayliss EA, Gaglio B, … Glasgow RE. The frequency and behavioral outcomes of goal choices in the self-management of diabetes. The Diabetes Educator. 2005;31:391–400. doi: 10.1177/0145721705276578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flattum C, Friend S, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Motivational interviewing as a component of a school-based obesity prevention program for adolescent girls. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2009;109:91–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flattum C, Draxten M, Horning M, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D, Garwick A, Kubik MY, Story M. HOME Plus: Program design and implementation of a family-focused, community-based intervention to promote the frequency of healthfulness of family meals, reduce children’s sedentary behavior, and prevent obesity. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2015;12:53. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Gurvich O, Kubik MY, Garwick A, Dudovitz B. The healthy home offerings via the mealtime environment (HOME) plus study: Design and methods. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2014;38:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett K, Okuyama S, Jones W, Barnes D, Tran Z, Spencer L, … Marcus A. Bridging the transition from cancer patient to survivor: Pilot study results of the cancer survivor telephone education and personal support (C-STEPS) program. Patient Education and Counseling. 2013;92:266–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golay A, Brock E, Gabriel R, Konrad T, Lalic N, Laville M, … Anderwald C. Taking small steps towards targets - perspectives for clinical practice in diabetes, cardiometabolic disorders and beyond. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2013;67:322–32. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golley RK, Hendrie GA, Slater A, Corsini N. Interventions that involve parents to improve children’s weight-related nutrition intake and activity patterns - what nutrition and activity targets and behaviour change techniques are associated with intervention effectiveness? Obesity Reviews: An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2011;12:114–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde J. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) - A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht J, Borrelli B, Breger RKR, Defrancesco C, Ernst D, Resnicow K. Motivational interviewing in community-based research: Experiences from the field. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;29(Suppl):29–34. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2902s_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JO, Wyatt HR, Reed GW, Peters JC. Obesity and the environment: Where do we go from here? Science (New York, NY) 2003;299:853–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1079857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath CC, Vickers KS, Ehrlich A, McGovern L, Johnson J, Singhal V, … Montori VM. Clinical review: Behavioral interventions to prevent childhood obesity: A systematic review and metaanalyses of randomized trials. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;93:4606–4615. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Pike J, Adams H, Cross D, Doyle C, Foreyt J. Telephone intervention promoting weight-related health behaviors. Preventive Medicine. 2010;50(3):112–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JC. An evidence-based approach for establishing dietary guidelines. The Journal of Nutrition. 2007;137:480–3. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.2.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke EA. Motivation through conscious goal setting. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 1996;5:117–124. doi: 10.1016/S0962-1849(96)80005-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke BL. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20:137–160. doi: 10.1177/1049731509347850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J, Chater A, Lorencatto F. Effective behaviour change techniques in the prevention and management of childhood obesity. International Journal of Obesity (2005) 2013;37:1287–94. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarvey E, Keller A, Forrester M, Williams E, Seward D, Suttle DE. Feasibility and benefits of a parent-focused preschool child obesity intervention. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1490–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.9.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meybodi FA, Pourshrifi H, Dastbaravarde A, Rostami R, Saeedi Z. The effectiveness of motivational interview on weight reduction and self-efficacy in Iranian overweight and obese women. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2011;30:1395–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York, NY: The Guilford Press, a Division of Guilford Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan PJ, Rex J. New Moves: A school-based obesity prevention program for adolescent girls. Preventive Medicine. 2003;37(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen L, Morgan A, Fischer A, Ellis S, Hoy A, Kelly MP. The cost-effectiveness of public health interventions. Journal of Public Health. 2012;34:37–45. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paineau D, Beaufils F, Boulier A, Cassuto DA, Chwalow J, Combris P, … Bornet FRJ. The cumulative effect of small dietary changes may significantly improve nutritional intakes in free-living children and adults. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010;64:782–91. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxman JR, Hall AC, Harden CJ, O’Keeffe J, Simper TN. Weight loss is coupled with improvements to affective state in obese participants engaged in behavior change therapy based on incremental, self-selected “small changes”. Nutrition Research (New York, NY) 2011;31(5):327–37. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1997 doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, DiIorio C, Soet JE, Borrelli B, Hecht J, Ernst D. Motivational interviewing in health promotion: It sounds like something is changing. Health Psychology. 2002;21:444–451. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.5.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, McMaster F. Motivational interviewing: Moving from why to how with autonomy support. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2012;9:19–19. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie LD, Welk G, Styne D, Gerstein DE, Crawford PB. Family environment and pediatric overweight: What is a parent to do? Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105:S70–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational interviewing in health care. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rychetnik L, Hawe P, Waters E, Barratt A, Frommer M. A glossary for evidence based public health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2004;58:538–545. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.011585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonneville KR, Rifas-Shiman S, Kleinman KP, Gortmaker SL, Gillman MW, Taveras EM. Associations of obesogenic behaviors in mothers and obese children participating in a randomized trial. Obesity. 2012;20:1449–54. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerbell CD, Waters E, Edmunds L, Kelly SAM, Brown T, Campbell KJ. Interventions for preventing obesity in children (review) Cochrane Database Systematic Review. 2005;20(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 7. Washington DC: US Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kruk JJ, Kortekaas F, Lucas C, Jager-Wittenaar H. Obesity: A systematic review on parental involvement in long-term european childhood weight control interventions with a nutritional focus. Obesity Reviews: An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2013;5:745–760. doi: 10.1111/obr.12046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong EMY, Cheng MMH. Effects of motivational interviewing to promote weight loss in obese children. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2013;22:2519–30. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo Baidal JA, Price SN, Gonzalez-Suarez E, Gillman MW, Mitchell K, Rifas-Shiman S, … Taveras EM. Parental perceptions of a motivational interviewing–based pediatric obesity prevention intervention. Clinical Pediatrics. 2013;52:540–548. doi: 10.1177/0009922813483170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]