Abstract

Background/Aims

Despite a broad call for biobanks to use social media, data is lacking regarding the capacity of social media tools, especially advertising, to engage large populations on this topic.

Methods

We used Facebook advertising to engage Michigan residents about the BioTrust for Health. We conducted a low-budget (<USD 5,000), 26-day social media campaign targeting Michigan residents aged 18–28. We placed 25 Facebook advertisements and analyzed their performance in terms of reach and cost across 3 engagement types: passive, active and interactive. We compared engagement before, during and after the campaign.

Results

The Facebook page was viewed 1,249 times during the month of the advertising campaign, versus once in the month prior. 779,004 Michigan residents saw ads an average of 25.8 times; 4,275 clicked ads; the average click-through-ratio was 0.021%. Interactions included 516 ‘likes’ and 30 photo contest entries. Cost per outcome ranged from <USD 0.005 per exposure to USD 182 per photo entry. The average cost per click was USD 1.04.

Conclusion

A social media strategy to build public awareness about biobanking is not likely to be effective without a promotional ‘push’ to distribute content. Social media advertisements have the capacity to scale-up engagement on biobanking while keeping costs manageable. Facebook advertisements provide necessary access points for unaware participants, with implications for public trust.

Keywords: Awareness, Biobank, Community engagement, Public health, Social media

Background

Large population biobanks storing biological specimens and related personal and health information are resources that in many cases facilitate secondary uses of samples and data and may involve unknowing participants. Large-scale community engagement efforts that reach participants in retrospective biobanks, which comprise data and samples that have already been collected [1], will contribute to strengthening population health research systems that may depend, practically and ethically, on public trust. We used Facebook advertisements to raise awareness among Michigan residents about the Michigan BioTrust for Health (BioTrust), and assessed the ads’ capacity to inform participants in this retrospective biobank by tracking reach and cost across 3 engagement types: passive, active and interactive.

Formally marketing double de-identified newborn screening dried blood spots (DBS) for health research, Michigan is home to one of the largest biobanks in the United States. Run by the Michigan Department of Community Health, the BioTrust offers a collection of biospecimens whose size, unbiased sampling and linkability to public health data make it a ‘goldmine’ [2] for public health assessment and a potential key to important health questions.

The BioTrust’s nonprofit organization, the Michigan Neonatal Biobank, provides access to almost 4 million DBS that were stored before education and consent mechanisms for storage and research uses were in place, such that these subjects and their parents are unlikely to be aware of this resource or their participation. As of May 2010, new DBS have only been added to the research pool (‘prospectively’) with parental consent, while DBS from the ‘retrospective’ collection – those stored from babies born in the state between July 1, 1984 and April 30, 2010 – remain in the Michigan Neonatal Biobank unless parents or adult participants opt out on their own initiative [3, 4]. The number of participants in Michigan’s retrospective biobank collection who were 18 or older in 2012 was approximately 1.5 million [5].

About a third of US states retain DBS for long-term storage after newborn screening [6] in repositories that could be considered biobanks, in effect if not in name. Lack of transparency on the part of states that store DBS can undermine public trust in newborn screening programs and secondary research initiatives [7]. In Texas and Minnesota, lawsuits brought by parents with privacy concerns have led to the destruction of DBS stored in public health biobanks in those states [8]. Even without the threat of litigation, public trust is a major issue for these repositories, in biobanks worldwide, and any system that would share health specimens and data to improve healthcare and outcomes [9–12].

Complex initiatives such as these in public health and scientific research can generate public skepticism and doubt in both enterprises [13, 14]. Mechanisms for establishing what Giddens [13] would call an ‘access point’ are critical for gaining and maintaining trust. An access point is a direct, interpersonal interaction in which one of the individuals represents a complex system or institution. Access points can mitigate the uncertainty of being involved in large, abstract systems through the direct and human interaction that forms the basis of a trusting relationship [13, 15]. If an individual has the opportunity to interact with another who can represent organizational and institutional interests, the basis for trust (or mistrust) becomes tangible [13, 16, 17]. Social media can offer a channel for establishing virtual access points, establishing and leveraging direct, human relationships; advertisements can be socially embedded within networks of ‘friends’ and can link the public to pages where conversations can establish relationships of trust.

Despite the potential benefits of large-scale engagement, public outreach in Michigan to date has occurred on a small scale relative to the millions with DBS in the BioTrust. Since before the formalization of the BioTrust in 2009, the Michigan Department of Community Health [3, 18], University of Michigan [19] and Michigan State University [20] have conducted various engagement activities to gauge public opinion on biobanking in the state. These have ranged in how many people they reached (scale), how much information about the BioTrust and related issues could be shared (scope) and how much time or opportunity was available to interact with other citizens or experts (depth) about the issue.

Although information about the BioTrust is publically available, our research in Michigan has shown that very few Michiganders have ever heard of the BioTrust [21], suggesting that access points are needed to raise awareness and establish active relationships with the general public. A survey of Michigan adults conducted through Michigan State University’s Institute for Public Policy and Social Research in the fall of 2011 found that 49 of 807 surveyed (6%) said they had heard or read about the BioTrust [22].

Facebook is well suited to boost awareness and engagement, as it is the most viewed website on the Internet [23], and approximately half of Michigan residents use the site [24]. Social media tools facilitate inexpensive outreach to targeted subgroups of the general public and, among Internet users, can also reach the population regardless of education, race/ethnicity or health care access [25, 26].

Social media has long been identified as relevant to biobanking, particularly in its capacity to expand the reach and effectiveness of community engagement [27– 29]. A study of potential participation in cancer biobanks found that social media could be a powerful tool for communicating with 18–29-year-olds in particular [30]. In supporting relationships between biobanks and their participants, social media has the dual capacity to raise awareness and provide a route to ‘deeper’ engagement for those who are interested. Yet, while some existing biobanks and special interest groups are looking to social media to enhance partnerships between researchers and participants, existing biobanks on the scale of the BioTrust have been slow to realize the full potential of online inter-activity [27, 31]. We found no evidence of Facebook advertising being a tool for raising public awareness of biobanks.

In this paper, we describe a 26-day Facebook advertising campaign designed to raise awareness about Michigan’s BioTrust for Health among participants aged 18– 28. We consider its impact in terms of its reach and cost across 3 types of engagement: passive, active and interactive. Within these categories, metrics such as ad reach, clicks, likes, or comments provide insight about how individuals engaged with, and potentially learned from, the material we presented [26, 32–34].

Our study demonstrates that a social media strategy to build public awareness about biobanking is not likely to be effective without a promotional ‘push’ to distribute content, and that Facebook advertisements can be used to achieve passive, active and interactive engagement at low costs. We provide insight into what reach, cost and performance metrics might be expected from advertisements on this issue, a step toward establishing a needed benchmark for comparable public health campaigns. Cost is relevant from a programmatic perspective given limited budgets for engagement and education, particularly in departments of health where fiscal constraints are the norm. The capacity of Facebook advertising to reach such large numbers of people is significant socially, ethically and for public trust.

Methods

The primary goal of the 26-day Facebook advertising campaign was to make Michiganders aged 18–28 aware that the state is home to a collection of stored DBS called a biobank, comprising bloodspots from about 4 million Michigan natives born after June 1984. We assessed the ad campaign’s capacity to promote our social media content by comparing Facebook page views before, during and after the campaign, and we tracked and analyzed ad performance by recording key metrics, such as cost, reach, click-through-ratios (CTR), likes, and viewer actions.

Phase I: Preparation

Although this paper focuses on the impact of a Facebook ad campaign, it is important to note that our advertising strategy and content were related to 2 other modes of outreach. As delineated in table 1, the ad campaign ran concurrently with 12 college campus visits with educational tables, surveys and give-aways (T-shirts, flash drives and chocolate), and with the submission phase of a ‘mybloodspot.org’ photo contest that ran on Facebook through the application Wildfire.

Table 1.

Community engagement using Facebook: timeline and approach

| Timeline | Phase I March 2012: preparation |

Phase II April 2012 |

Phase III May–August 2012: completion and analysis |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| awareness campaign ↔ data collection | ||||

| Approach | ||||

| Facebook campaign | Updated Facebook page for ‘brand’ consistency and added educational content |

Created ads continuously, varying content, images, target group, and landing pages Managed ads continuously, based on Facebook statistics, ad performance reports Research team made 18 posts to Facebook page to educate viewers, cross- promote contest, events, and website, and respond to Facebook posts |

Collected and analyzed Facebook ad reports: responder demographics, ad performance, actions by impression times Tracked views of posts, shares, comments on Facebook page and Facebook page statistics via Facebook ‘Insights’ |

1. Analyzed data on Facebook page, Facebook ad campaign, and individual Facebook ads 2. Assessed impact of engagement based on reach and cost |

| Mybloodspot.org website |

Updated website for ‘brand’ consistency; created links to photo contest and Facebook page |

The website was the richest source of educational information offered during the ad campaign |

Google Analytics tracked website traffic and sources, including social media |

Analyzed of website traffic and sources |

| Photo contest | Created contest via Wildfire |

Entrants submitted photos to Wildfire (Facebook app); research team posted photo submissions to Facebook page |

Counted valid photo contest entries |

May: voting and selection phases of contest; tracked votes via Wild- fire and interactions with entrants on Facebook |

| Campus events | Prepared materials, give-aways, kiosks |

Educated students at 12 college and community college campuses about the Michigan BioTrust |

Conducted surveys at events via website (un- related to Facebook campaign) |

|

Cross-promotion: The Facebook page, website, and photo contest pages were all landing pages for Facebook ads (Phase II). Campus events also promoted these pages.

Educational materials presented our content in an accessible and neutral tone to promote awareness, information-sharing and engagement. We created a logo, brand and simple URL through the name and website ‘mybloodspot.org’ with the goal of creating a memorable campaign identity. A Facebook page communicating the ‘basics’ (facebook.com/mybloodspot) and a streamlined website offering details about the BioTrust and biobank research lay the groundwork for the ad campaign.

Phase II: Awareness Campaign

Launching an advertisement campaign on Facebook entails selecting an ad type, a target group, a landing page (where ad viewers will land after clicking an ad), selecting pricing and budget options, and designing an ad. We experimented with various images, messages and ad types throughout the duration of the campaign, directing viewers to 3 target sites – www.mybloodspot.org, the Facebook page (facebook.com/mybloodspot) or to the photo contest. We targeted most advertisements to approximately 2 million Michigan residents aged 18–28, pricing our advertisement at or near the high end of Facebook’s suggested bids. Online supplementary figure 1 (www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000351451) details Facebook’s ad-creation process and the options we selected.

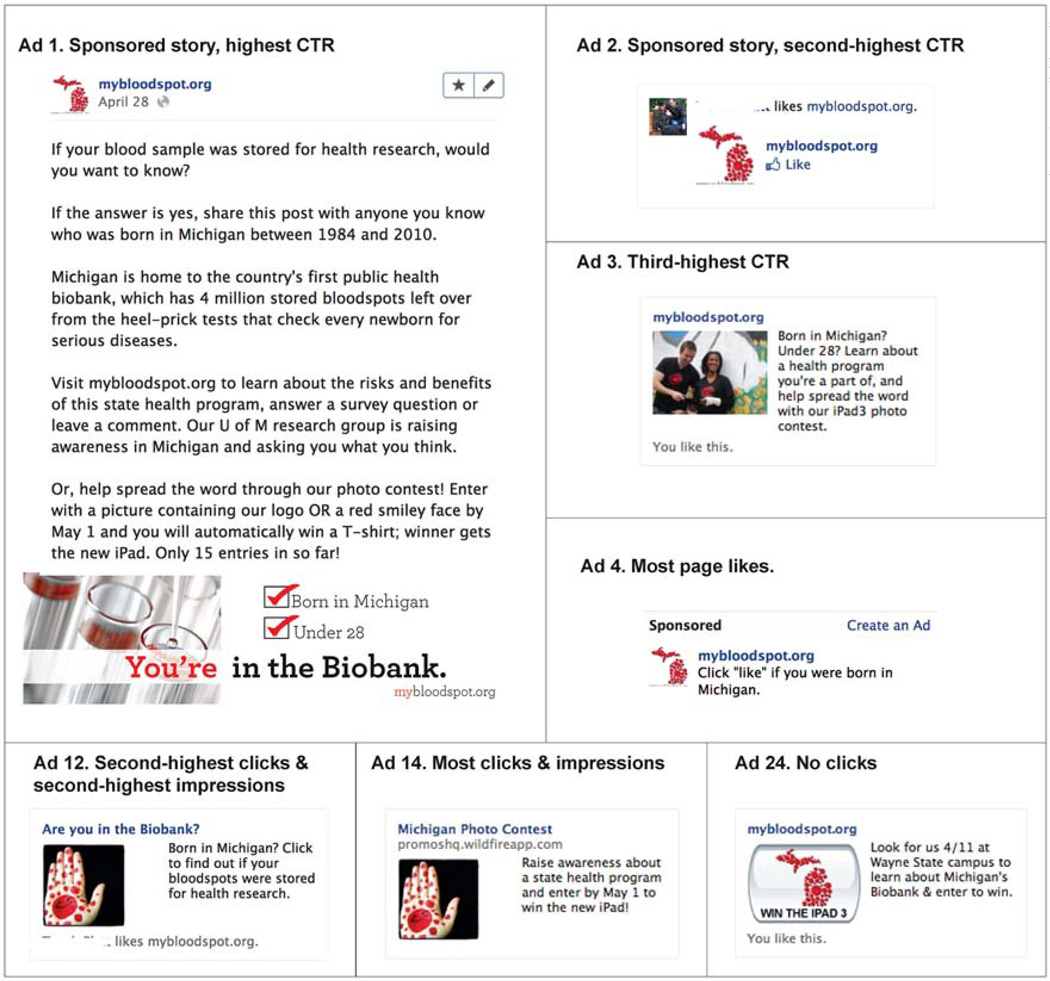

The images and content of our Facebook ad campaign conveyed a neutral-to-positive tone that in some cases sought to harness the inclination of Facebook users to share points of personal or group (in this case, state) pride. We designed ads with the goal of appealing to the user’s connection to Michigan either in the text or by incorporating the shape of the state into the associated image. Seventeen advertisements promoted the photo contest and/or its prizes (T-shirts for all entrants, and an iPad for the grand prize). Five advertisements provided an educational message or the promise of one (e.g., ‘Click here to learn about…’). Three advertisements appealed to an individual’s affiliation with a school that we visited, and 2 ‘sponsored’ advertisements used social connections to draw attention (e.g. ‘your friend likes this’).

Figure 1 shows a sampling of advertisements representing the range of images and messages used and selected for notable aspects of their performance.

Fig. 1.

Sample advertisements. Note: Ad numbers correspond with figure 2.

If a particular advertisement did not gain momentum – evaluated in terms of clicks to one of our target sites – within a few days, we stopped running it so that the dollars from our campaign budget went to more successful advertisements. We also paused and, in some cases, restarted advertisements depending on their ability to ‘compete’ with ads that were running concurrently. Facebook’s Ad Manager provides live, group-level statistics on responder demographics, user interactions, and ad and campaign performance in categories such as cost, reach, actions, and CTR (see table 2 for a list of Facebook definitions).

Table 2.

Common Facebook terms and definitions

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Reach | The number of unique individuals who have seen an ad |

| Frequency | The number of times an individual sees an ad |

| Impressions | The number of times an ad is shown on Facebook (Reach* frequency = impressions) |

| CTR | Ratio of clicks to impressions |

| Likes | Individuals can ‘like’ individual posts or can ‘like’ a Facebook page. After liking an organization’s Facebook page, the individual and the organization remain connected. When an individual likes a page, the page and its posts can appear on the individual’s timeline. An individual’s friends (members of their social network) can then also be exposed to the page. |

| Social clicks | Clicks on ads that include language about the social context (i.e. with information about a viewer’s friend/s who have connected with us). Sponsored stories and ad posts promoting a Facebook page can include this language and achieve a ‘social’ reach. |

| Facebook page | Similar to an individual’s ‘timeline’ or ‘wall’ users can view, share, and comment on content on an organiza- tion’s Facebook page (e.g. facebook.com/mybloodspot). |

| Sponsored story | Paid messages that come from friends about them engaging with a page. When someone interacts with a page, it creates a story that their friends may see in their news feed. |

Source: http://www.facebook.com/help/447834205249495/. See this glossary online for details and additional Facebook advertising terms.

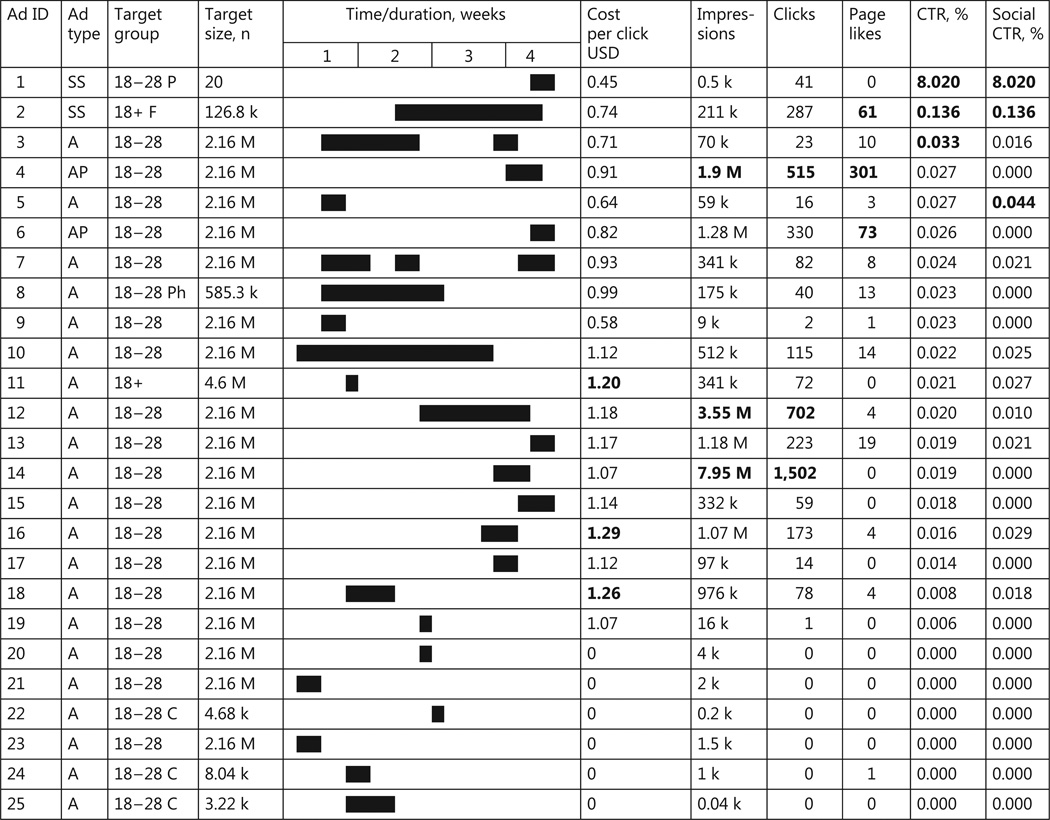

Figure 2 shows the target group, target size, time and duration of each ad, along with results: cost, impressions, clicks, page likes, CTR, and social CTR.

Fig. 2.

Facebook advertisements design and results. Ad type: SS = sponsored story (appears in viewer’s news feed); A = traditional ad (appears in ad space); AP = ad created from a wall post (a copy of a wall post appears in ad space). Target group: 18+ = Michigan residents aged 18+; 18–28 = Michigan residents aged 18–28; P = …who liked a post on our wall; Ph = …who are interested in photography; F = …who have friends that liked us; C = …who attend a specific college (Wayne State, Lansing Community College, or Washtenaw Community College). Bold text indicates top three within a category. See images of ads 1, 2, 3, 4, 12, 14 and 24 in figure 1. CTR = Click-through rate.

Although we do compare ad performance here, based on Facebook Ad Manager’s ad performance reports, this advertising campaign was not designed for the primary purpose of controlled comparison. We continually revised and created new advertisements, responding to their performance in real time in attempts to maximize their efficiency and educational reach. The effectiveness of this campaign overall will be evaluated in comparison to other methods of outreach in the future.

Phase III: Completion and Analysis

Facebook provides analytic data through its Ad Manager and Insights interfaces. The Facebook Ad Manager recorded reach, cost and user actions. To see who was reached, as well as how many, we ran reports on responder demographics that presented the age and gender breakdown of the campaign’s impressions. Using Facebook Insights, we tracked user interactions and sources of Facebook page traffic; we ran reports on page views and likes for month-long periods before, during and after the advertising campaign in order to compare Facebook activity with and without advertising.

Supplementing our Facebook advertising data were reports provided by Wildfire, tracking photo contest entries and votes both during and after the advertising campaign, and Google Analytics statistics mapping and timing traffic on our website during our advertising campaign, which provided another window into how deeply visitors who landed on our site plumbed for information.

In this paper, we present the results of our advertising campaign in terms of reach and cost overall, and across 3 types of engagement: passive, active and interactive. We use available metrics (clicks, likes, posts, etc.) as commonly used ‘Key Performance Indicators’ of engagement [26] as described below.

Types of Engagement

Public engagement has a variety of meanings in theory and practice ranging from the purely rhetorical to a type of communication or educational experience based on the deficit model of the public understanding of science to a form of deliberative democracy [35]. The types of engagement we describe here are labeled in terms of the user’s experience and process of becoming aware, knowledgeable or vocal about Michigan’s BioTrust. In the social media context, engagement is a mechanism for establishing connections [26].

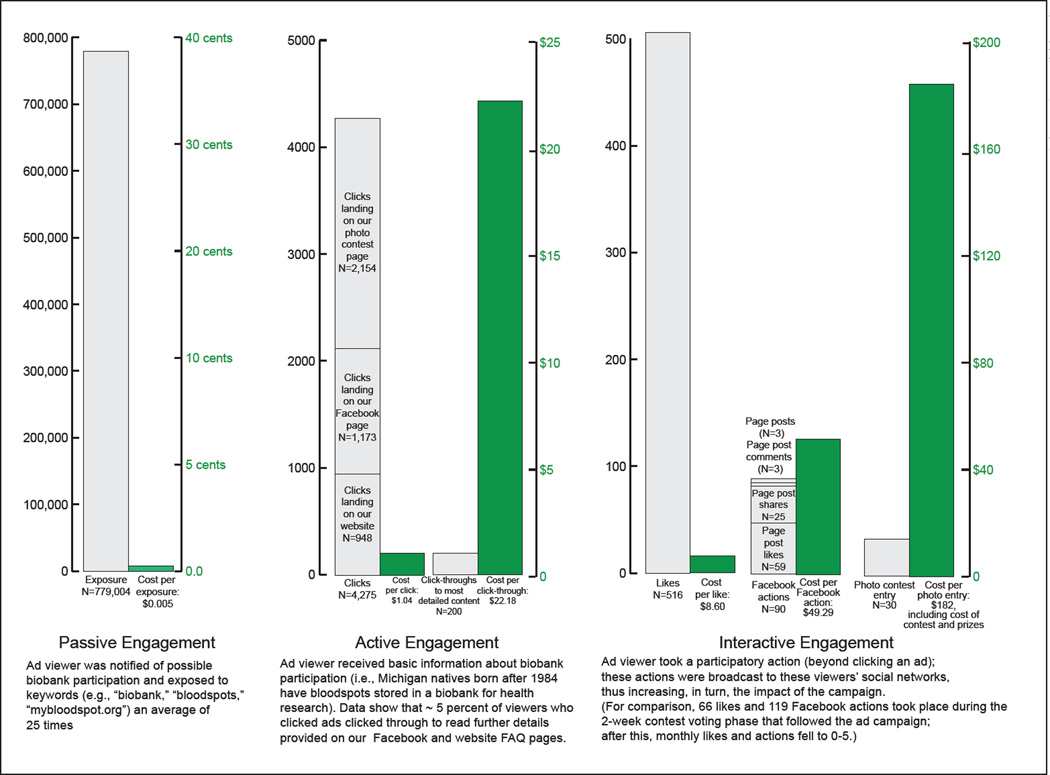

‘Passive engagement’, corresponding with the reach of the advertisement campaign, is defined as the exposure of viewers to the ad campaign, including key terms and brief educational content. ‘Active engagement’, corresponding with clicks, is defined as the linking of ad viewers to landing pages that provide access to static or interactive content. ‘Interactive engagement’, corresponding with likes, page posts, page post comments, page post likes, shared posts, or participation in our photo contest, is defined as the establishment of a dynamic relationship among our research group, an ad viewer and the ad viewer’s social network, through the participatory action of the ad viewer ( fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Impact of Facebook campaign.

Reach

As a Facebook term, ‘reach’ is a measure of the number of individuals who view advertisements, and we apply this definition in our analysis of passive engagement. In order to assess the scale of other engagement types, our definition of ‘reach’ within these categories also includes the total number of actions taken by individuals who viewed advertisements.

Cost

The costs of various ad campaign results, categorized across 3 types of engagement, are shown in figure 3 and are calculated as number of individuals reached/USD 4,436, with one noted exception: the cost per photo entry is calculated as reach/USD 5,481 to include the USD 1,045 of associated photo contest costs.

Results

Overall Campaign Reach

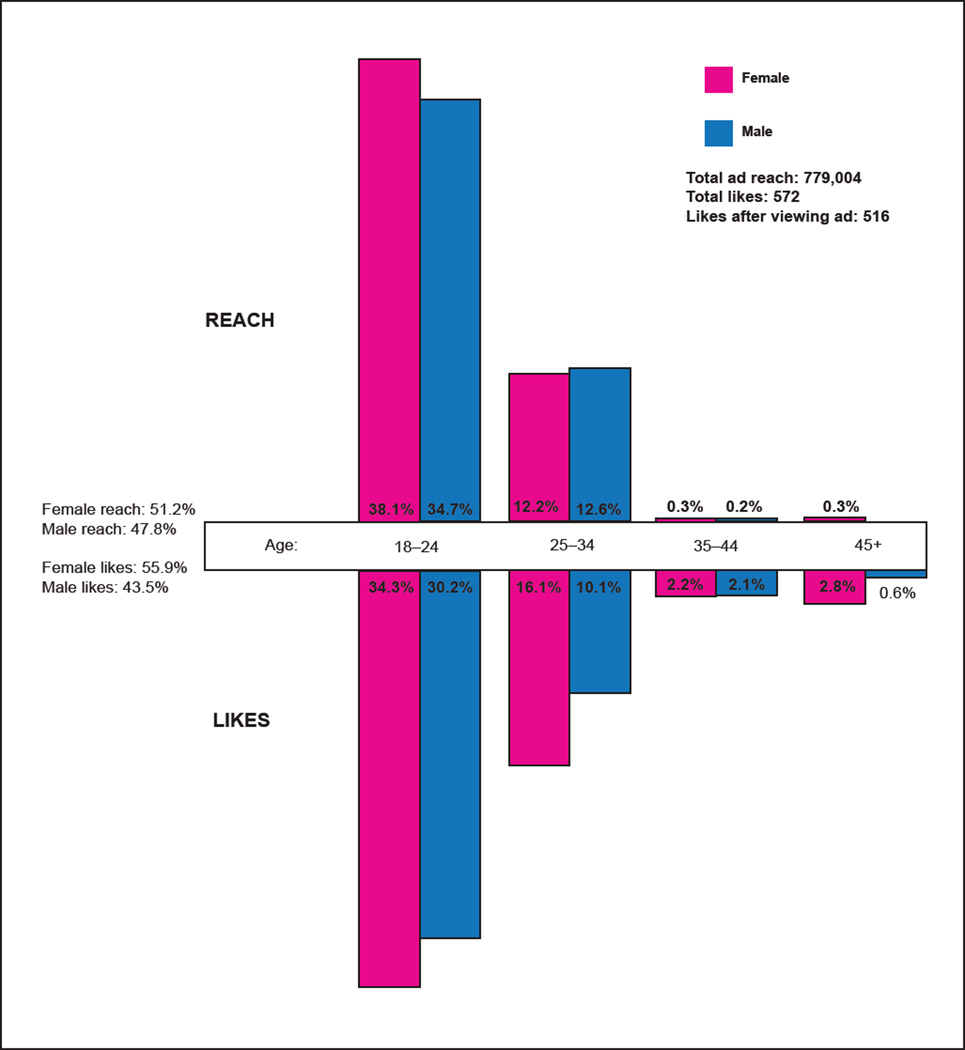

Facebook advertising statistics are group-level data that can be summarized and analyzed by ad type, age group and gender. The campaign reached 779,004 unique Michigan residents aged 18 or older; impressions, or Facebook’s tally of the number of times the advertisements were placed on a viewer’s screen, totaled 20,087,795.

Of these impressions, 46% of viewers were male; 52% were female. The majority (88%) of viewers were aged 18–24, and 12% were 25–34 years old. Except for 2 advertisements that targeted Michigan residents over 18, the campaign targeted Michigan residents in the specific age range of 18–28. Less than 1% of impressions from our campaign reached viewers over 34.

Figure 2 shows the number of impressions for each advertisement in our campaign, and figure 4 shows reaches and likes tracked during our ad campaign, summarizing campaign demographics (age and gender).

Fig. 4.

Gender and age. Individuals reached and individuals who ‘liked’ our page during Facebook ad campaign.

In the month prior to the advertising campaign, Facebook Insights recorded 1 view of our Facebook page and 1 new ‘like’, suggesting that creating a Facebook page for education on this topic alone was not sufficient for connecting with the public. Facebook advertisements were necessary to drive activity on our Facebook page. We observed that during the advertising campaign, we achieved 1,249 page views and 572 likes. Activity declined after the advertising campaign: 813 page views and 69 new likes were recorded in May, the month after the campaign (which included the photo contest voting and selection phases), while data collected for June included 70 page views and 4 new likes.

Figure 3 charts the impact of the Facebook advertising campaign in terms of specific outcomes such as ad views, clicks and interactions, such as page and post likes, post shares, page posts, page post comments, and photo contest entries, reporting the number of individuals and cost of each result; we categorized results across 3 types of engagement: passive, active and interactive, as described above.

Overall Campaign Cost

The total cost of the 4-week campaign was USD 4,436. Related costs for the photo contest and prizes totaled USD 1,045 – USD 222 to run a photo contest through a third-party platform, Wildfire; USD 529 for the contest grand prize (the new iPad); USD 221 for 32 T-shirts; USD 23 for USB keys; and USD 50 in gift cards. The average cost per click was USD 1.04, calculated as the total cost divided by the clicks received; the cost per click of individual ads is included in figure 2. It cost less than one cent per individual reached and less than one-tenth of one cent per impression. The cost of each Facebook ‘like’ was USD 8.60 or 10.60 including the photo contest costs.

Reach and Cost across Engagement Types

Passive Engagement

‘Passive’ viewers who read advertising content were exposed to key words such as ‘biobank’, ‘bloodspots stored for research’ and the URL ‘mybloodspot.org’.

Reach

At the broadest level, impressions alone represent a form of engagement (n = 20 million). The 779,004 individuals we reached saw our advertisements, on average, 25.8 times. Given this level of saturation, it is likely that that some viewers who took no action still noticed ads and their contents. Thirteen individuals ‘liked’ us following an impression, without clicking on the ad itself.

Cost

The cost of exposure was USD 0.005 per ad viewer.

Active Engagement

Active viewers navigated from advertisements to one of 3 landing pages (Facebook, photo contest or my bloodspot.org) and in some cases to additional web pages. These viewers minimally accessed the information: ‘Michigan natives aged 2–28 are all part of the state’s biobank, a collection of bloodspots stored for health research.’ Maximally, the educational impact that resulted from advertisement clicks were views of our website FAQ and Facebook ‘about us’ pages that communicated details about our outreach and about biobank participation.

Reach

The number of individuals who clicked on one of our Facebook advertisements was 4,275. Overall, the CTR, or percentage of impressions that led viewers to click on an ad, was 0.021%.

Clicking an advertisement led viewers to our Facebook page (n = 1,173), our photo contest page (n = 2,154) or our website, mybloodspot.org (n = 948).

A total of 200 individuals – just 4.7% of viewers who clicked on an advertisement – clicked through to the most detailed information provided on our website’s FAQ page, mybloodspot.org/getinformed (49) or in our Facebook ‘about us’ content (151).

We found that viewers were far more likely to click an ad or post they saw associated with the name of a friend who had already liked us. The ‘social CTR’ of our campaign overall was 0.077%. A sponsored story (whose content was simply: ‘[Friends name] likes mybloodspot.org’) reached 32,981 Michiganders who had friends who had liked us already – with a CTR of 0.136%.

CTR averages by gender were relatively even. Males aged 18–24 and 25–34 both had an average CTR of 0.021%. Females in the same age brackets clicked through at a rate of 0.020 and 0.025%, respectively.

Tracking the behavior of visitors to our website, Google Analytics statistics were another indicator of the depth of to which viewers actively sought additional information during our Facebook advertising campaign. In this period, a quarter of visitors to our homepage went on to look at a second page of our website, and 14% looked at a third page; a third of visitors spent more than a minute on the website, and 12.4% spent more than 10 minutes.

Cost

The cost per advertisement click was USD 1.04. The cost per ad viewer who clicked through to our most detailed content pages was USD 22.18.

Interactive Engagement

Interactive engagement involved participatory actions among ad viewers – likes, posts, page posts, page post comments, page post likes, shared posts, and participation in our photo contest – which themselves were broadcasted to the interactor’s social network. Participatory ad viewers who established a connection with us on Facebook increased our campaign impact by allowing content to be shared virally and by permitting content to stream into their Facebook ‘news feeds’ on an ongoing basis.

Reach

During our ad campaign, 516 individuals liked our page within 24 hours of viewing an ad or within 28 days of clicking on an ad. A total of 477 clicked ‘like’ directly on an advertisement. A single ad that ran with the text, ‘Click like if you were born in Michigan!’ received 246 likes. (Other ‘like’ sources included our Facebook page (62), our mobile site (15), our website (15), and friend referrals (13)).

During the ad campaign, 3 people added a post or commented on one of our posts on our Facebook wall: ‘Interesting.’; ‘I support this…’; and ‘Yo [ sic ] people have my blood, I want it back now.’ The latter comment was an opportunity for us to engage with an individual about his consent options as well as the benefits and risks of participation.

Other Facebook interactions that increased the impact of our campaign were page post shares (n = 25) and page post likes (n = 59) that were broadcasted to the users’ social networks.

Another form of interactive engagement was participation in our photo contest. A total of 30 entrants, all Michigan residents aged 18 and older, submitted photos that met 2 requirements: they featured an image of Michigan and, in some form, a red smiley face patterned off of the mybloodspot.org logo. The average CTR of advertisements that promoted the contest was just slightly lower (0.020 vs. 0.023%) than those that did not.

Facebook and Wildfire data collected after the ad campaign showed that these 30 entries yielded further (indirect) interactions among photo contest participants and voters (not included in fig. 3, which focuses on the direct impact of the advertising campaign). During an 18-day voting period, ‘mybloodspot.org’ received 137 Facebook likes, and its timeline was viewed 744 times; voters, who were allowed to vote for up to 3 photo entries, cast 1,477 votes. On our Facebook wall, we exchanged information with one contest entrant who posted questions regarding newborn screening and bloodspot retention policies in other states, and another person contributed to this thread of comments emphasizing the distinction between biobanks and newborn screening. Another commenter and photo contest entrant born before 1984, with a daughter in the BioTrust, wrote in a response to a post that she wished she were a part of the BioTrust herself. Facebook actions during the photo contest voting phase included 31 page post likes, 15 page post comments, 3 posts, and 3 page post shares.

Cost

The cost of each interaction (combining likes, Facebook actions and photo contest participation) was USD 6.97 or USD 8.61, including the associated photo contest costs (the Wildfire application and contest prizes). As shown in figure 3, the cost per ‘like’ was USD 8.60. The cost per Facebook action (page posts, page post comments, page post shares, and page post likes) was USD 49.29. The cost per photo entry was USD 148 or 182 including photo contest costs.

Discussion

Reach and Cost

This 26-day advertising campaign was perhaps the most far-reaching communication tool used to date to inform individuals of their participation in the Michigan BioTrust. The overall campaign reach was significant because it was both large (779,004) and highly targeted (reaching Michigan residents aged 18–28).

The data presented here to report the reach, cost and performance metrics of our campaign offers a point of comparison for others who might look to use Facebook advertising as a tool for raising awareness about biobanking and other public health issues that are unfamiliar to the public.

The overall CTR of our campaign was 0.021%. Our advertisements were noncommercial, and in addressing biobanking, they presented an unfamiliar issue compared to many in public health, such as infectious or chronic disease. These peculiarities of our campaign made it difficult to compare against an external benchmark. In business, an ‘optimal’ CTR is often cited as 0.1% or above, but benchmarks for successful campaigns are highly variable and contextual; for a nonprofit, educational campaign such as this, the optimal rate is unknown. A Webtrends survey of 2009–2010 Facebook campaigns reported an average CTR of 0.051% with an average cost per click of 49 cents in 2010. Their report showed that CTR increased with age: the average CTR among viewers aged 18–24 was under 0.02%, and for campaigns they categorized as ‘health care’ related, the average CTR was 0.011%, with a cost-per-click of USD 1.27.

The promotion of Facebook content links individuals to educational information, as measured by clicks, but also links individuals to people and organizations, as measured by likes. Facebook ‘likes’ are necessary for leveraging networks to achieve a snowballing social reach; thus, a promotional ‘push’ to establish connections is particularly important for organizations beginning at ground level, with a fan base of zero. There is evidence that sparking interest and discussion or priming amplifies communications’ impact [36, 37]. Facebook clicks, likes and posts indicate interaction with the educational material beyond passive viewing.

‘Sponsored stories’ are ideal for promoting a public health message. These advertisements appear in users’ newsfeeds and, outside of the word-count restraints of other Facebook advertisements, can provide more detailed information. The 2 sponsored advertisements we ran had the highest CTRs of the campaign. Social advertisements had significantly higher CTRs than those that did not. The sociality of advertisements on Facebook has implications for the delivery of messages but may also affect their reception, since social ads are channeled through a trusted (‘friended’) source.

In terms of cost, we find that Facebook can be used to engage large populations inexpensively (USD 0.005 per exposure/passive engagement; USD 1.04 per click/active engagement). The more expensive actions associated with interactive engagement were comparable to standard compensation (stipends) for other forms of community engagement and could be considered well below typical costs if accounting for recruitment [38].

Generally, reach and cost of educational health awareness campaigns are affected by context and may vary widely within a single communications medium. Cultural and technological shifts in media consumption, the synergism of approaches within a single campaign, and variable definitions of outcome all create apples-to-oranges challenges when trying to evaluate efforts to raise public awareness. The existing public health literature offers spare data on cost-effectiveness across methods of information delivery. Some studies have examined cost effectiveness of health communications, but are not as well suited to comparison for our study, given their focus on specific high-risk or populations under-represented in research (e.g. [39, 40] ), interventions in the developing world and/or health behavior change outcomes (e.g. [41] ). Still, we looked to a ‘paper’ study to provide context for evaluation of the cost and results of our campaign because cost is a major obstacle for institutions seeking to reach biobank participants.

Paul et al. [42] compared the relative cost-effectiveness of 3 different types of pamphlets recruiting women (ages 50–69) to register with a Pap Test Reminder Service. The mailing of pamphlets is comparable to the passive type of engagement seen in our study. Individuals are exposed to a limited amount of information and may or may not choose to engage further. Compared to the Pap Test Reminder Service study, our campaign reach was over 100 times greater, at less than half the cost. Despite the expansive reach of passive engagement in the Facebook campaign, the percentage of viewers who were subsequently actively engaged – indicated by clicking on an advertisement – was very small (0.5 vs. 86%) compared to the percentage of recipients who reported reading the pamphlets, and the raw number of pamphlet-readers was higher.

As a form of interactive engagement, the number of ‘connections’ made within a month of the 2 campaigns, defined as women registered on the one hand and Facebook ‘likes’ on the other, was comparable: 550 among pamphlet-recipients and 516 among ad-viewers. By this measure, the Facebook ad campaign was more cost-effective than the one deployed in the pamphlet study. Future research comparing methods of outreach would provide valuable insight into optimizing community engagement efforts for a wide range of biobanking and public health initiatives.

Significance of Facebook Engagement: Implications for Biobanks and Public Trust

While information about the BioTrust exists in several locations on the Web, none is likely to be viewed by users who are not looking for it. The data we collected on Facebook engagement before, during and after our advertising campaign suggests that a social media strategy to raise public awareness about biobanking is not likely to be effective without a promotional ‘push’ linking individuals to educational content. The two-way, interactive capacity of Facebook to link institutions such as universities and lay populations is unparalleled, underutilized, and understudied in the field of public health. Despite the broad call for expanded use of social media, biobanks have yet to take full advantage of its interactivity [31].

The capacity of Facebook to engage large populations on the topic of biobanking has particular ethical significance for retrospective biobanks. In an attempt to bolster public trust in research, the proposed changes to the Common Rule outlined in the Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking would make consent a necessary part of research using de-identified data, but would not apply to existing biospecimens [43]. This change aims to strengthen the point of contact between participants and researchers or biobank representatives that may be achieved using traditional informed consent processes. This interaction can serve as an access point for establishing trust in public health systems. However, the proposed changes – as well as the current formulation of the Common Rule – still allow the BioTrust and other ‘retrospective’ biobanks to store and share de-identified biospecimens and data without the knowledge or meaningful consent of the public [1]. Michigan’s opt-out consent model for its retrospective DBS can only be meaningful if these individuals are informed of their participation. Simply put, no one can exercise their right to opt out of something without knowing they are in it [44, 45].

Absent the traditional (opt-in) consent process, the ethical imperative of respect for persons can be satisfied by establishing access points downstream, to inform the public of their participation and their options. Engagement with participants, parents and residents statewide can raise awareness about population biobanks, the privacy protections they have in place and the public’s options for consent [46, 47]. But the task of initiating engagement is challenging for both subjects (who may not know of the availability of information relevant to them) and for institutions (that may lack the resources to establish contact with providers of retrospective samples) [48]. Without public awareness, population biobanks struggle to implement safeguards of trust such as accountability and partnership with participants [49]. Communication, transparency, accessibility, and ongoing outreach foster public buy-in and informed participation in biobank research [46, 47, 50].

Five concerns have historically challenged public engagement on Michigan’s biobank and for large population biobanks in general: (1) the cost of outreach, (2) the inaccessibility of information and/or venues for engagement on the topic, (3) the complexity of the subject, (4) the perceived or actual apathy of the public, and (5) the risk of backlash. The political terrain in Michigan caused us to abandon an initial effort to use billboards to reach large numbers. Instead, we shifted focus to another mass medium – Facebook – to maintain focus on retrospective biobank participants, taking advantage of a dynamic platform that would enable viewers’ questions, interests and concerns to be readily communicated and answered. Public health social marketing campaigns enable an important feature of community engagement: the ability to receive feedback from targeted communities in real time [26, 29, 51]. In addition to effecting community engagement for its own sake, our outreach, including the social media campaign, has shed light on the sur-mountability of the obstacles on the path to an informed public.

This project demonstrates the capacity of Facebook advertising to lead individuals to an access point where individuals have the opportunity to view relevant information, link to educational content, ask questions, or engage with peers. Policies assuring that individuals can find details about de-identification, consent options, and the risks and the benefits of biobank participation – themes that would be covered in informed consent documents, websites or in lengthier community engagement activities such as community meetings or deliberative juries – need to be paired with explicit plans to push information out to large populations, thus improving transparency, accessibility and accountability.

Future research comparing engagement on this issue across information delivery methods, including websites, community meetings, campus visits, surveys, and deliberative juries, will enhance the literature on public health communications in general and on the theme of public trust in biobanking initiatives in particular. To specifically inform the state of Michigan about the BioTrust or state health departments with comparable repositories of newborn screening bloodspots and population health data, future target groups for engagement could include the parents of retrospective biobank participants, and retrospective biobank participants aged 2–17, now, or as they come of age.

Limitations

Assessing engagement on Facebook is limited to the aggregated data made available by Facebook. This means that actions represent the union of all actions and not independent categories; it is not possible to examine the intersection of the 780 actions.

By concentrating all of our advertisements within a 26-day period, we ran a high risk of advertisement fatigue. Ad frequency (ads were seen by individuals an average of 25.8 times) drove up impressions, lowering average CTRs, and advertisements that ran late in the campaign might have been lower solely because viewers had already seen our name and message dozens of times over the preceding weeks.

In simply observing how our target populations used Facebook to access and seek information, we are limited in how much we can say about knowledge transfer or long-term increased awareness. Future research coupling Facebook outreach with knowledge surveys would also provide additional insight into the effectiveness of Facebook advertisements in communicating complex public health content.

Conclusion

Social media has been recognized as a promising tool for communicating about biobanking, but existing content (e.g. pages and posts) is not likely to reach individuals unaware of their participation in a biobank or large populations without a promotional push. We found that incorporating Facebook advertisements in a social media strategy helped us to bridge the gap between making information available and making information accessible. Facebook advertisements can create an access point linking the public to relevant information and institutions, exposing large populations to key concepts and facilitating deeper engagement. Large numbers can be reached within a fixed budget and at a low cost; in this case, less than a penny per exposure or USD 1.04 per ad click. In addition to raising awareness and creating an access point with implications for public trust around biobanking, our study provides a valuable point of comparison for gauging effectiveness of communications in a public health context where a benchmark is lacking.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Grant Number 5-R01-HD-067264-02, Linking Community Engagement Research to Public Health biobank Practice. The authors gratefully acknowledge Susan B. King, D. Min, for her helpful input in reviewing the paper; and Nicole Fisher and Chris Wojcik, who provided outstanding research assistance throughout the project.

References

- 1.Solbakk JH, Holm S, Hofmann B, editors. The Ethics of Research Biobanking. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Couzin-Frankel J. Newborn blood collections. Science gold mine, ethical minefield. Science. 2009;324:166–168. doi: 10.1126/science.324.5924.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [accessed October 26, 2012];MDCH - Michigan BioTrust For Health: Frequently asked questions. http://www.michigan.gov/mdch/0,4612,7-132-2942_4911_4916-232933-,00.html.

- 4.Chrysler D, McGee H, Bach J, Goldman E, Jacobson PD. The Michigan BioTrust for Health: using dried bloodspots for research to benefit the community while respecting the individual. J Law Med Ethics. 2011;39:98–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2011.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. [accessed February 21, 2013];MDCH: Crude Birth Rates. http://www.mdch.state.mi.us/pha/osr/natali-ty/tab1.1.asp.

- 6.Olney RS, Moore CA, Ojodu JA, Lindegren ML, Hannon WH. Storage and use of residual dried blood spots from state newborn screening programs. J Pediatr. 2006;148:618–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis M, Goldenberg A, Anderson R, Roth-well E, Botkin J. State laws regarding the retention and use of residual newborn screening blood samples. Pediatrics. 2011;127:703–712. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothwell E, Anderson R, Botkin J. Policy issues and stakeholder concerns regarding the storage and use of residual newborn dried blood samples for research. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2010;11:5–12. doi: 10.1177/1527154410365563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansson MG. Building on relationships of trust in biobank research. J Med Ethics. 2005;31:415–418. doi: 10.1136/jme.2004.009456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grossmann C, BPowers B, Mc-JMGinnis Mc-JM, editors. Institute of Medicine (US): Weaving a strong trust fabric. Digital Infrastructure for the Learning Health System: The Foundation for Continuous Improvement in Health and Health Care: Workshop Series Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petersen A. Biobanks engagements: engendering trust or engineering consent? Genomics Soc Policy. 2007;3:31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ducournau P, Strand R. Trust, Distrust and Co-Production: The Relationship between Research Biobanks and Donors. In: Solbakk JH, et al., editors. The Ethics of Research Biobanking. Dordrecht: Springer; 2009. pp. 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giddens A. The Consequences of Modernity. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wynia MK. Public health, public trust and lobbying. Am J Bioeth. 2007;7:4–7. doi: 10.1080/15265160701429599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardin R. Distrust. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farrell H. Institutions and midlevel explanations of trust. In: Cook KS, Levi M, Hardin R, editors. Whom Can We Trust? How Groups, Networks, and Institutions Make Trust Possible. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2009. pp. 127–148. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giddens A. Beyond Left and Right: The Future of Radical Politics. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duquette D, Rafferty AP, Fussman C, Geh-ring J, Meyer S, Bach J. Public support for the use of newborn screening dried blood spots in health research. Public Health Genomics. 2011;14:143–152. doi: 10.1159/000321756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. [accessed April 3, 2013]; mybloodspot.org: Sharing the facts with Michigan’s 4 million. http://www.mybloodspot.org/

- 20.Fleck LM, Mongoven A, Marzec S. Stored Blood Spots: Ethical and Policy Challenges. East Lansing: Michigan State University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thiel D, Platt J, Liebert J, King S, Kardia SLR. National Human Genome Research Institute, Ethical Legal and Social Implications Program. Chapel Hill: 2011. Apr, Town Hall and Online Responses to Informed Consent Models for Public Health Biobanks. Abstracts Exploring the ELSI Universe: 2011 Congress. [Google Scholar]

- 22. [accessed January 2012];Michigan State University: State of the State Survey-60. http://www.ippsr.msu.edu/SOSS.

- 23.Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook ‘friends’: social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J Comput Mediat Comm. 2007;12:1143–1168. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Facebook Demographics Revisited - 2011 Statistics. [accessed October 23, 2012];Web Business by Ken Burbary. http://www.kenburbary.com/2011/03/face-book-demographics-revisited-2011-statis-tics-2/

- 25.Chou WY, Hunt YM, Beckjord EB, Moser RP, Hesse BW. Social media use in the United States: implications for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e48. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neiger BL, Thackeray R, Van Wagenen SA, Hanson CL, West JH, Barnes MD, Fagen MC. Use of social media in health promotion: purposes, key performance indicators, and evaluation metrics. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13:159–164. doi: 10.1177/1524839911433467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaye J, Curren L, Anderson N, Edwards K, Fullerton SM, Kanellopoulou N, Lund D, MacArthur DG, Mascalzoni D, Shepherd J, Taylor PL, Terry SF, Winter SF. From patients to partners: participant-centric initiatives in biomedical research. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:371–376. doi: 10.1038/nrg3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Platt J, Bollinger D, Dvoskin R, Kardia S, Kaufman D. Predicting informed consent preferences for participating in population-based research. Genet Med. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.59. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dove ES, Joly Y, Knoppers BM. Power to the people: a wiki-governance model for biobanks. Genome Biol. 2012;13:158. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-5-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luque JS, Quinn GP, Montel-Ishino FA, Are-valo M, Bynum SA, Noel-Thomas S, Wells KJ, Gwede CK, Meade CD. Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network Partners. Formative research on perceptions of biobanking: what community members think. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27:91–99. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0275-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gottweis H, Gaskell G, Starkbaum J. Connecting the public with biobank research: reciprocity matters. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:738–739. doi: 10.1038/nrg3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang R, Scown P, Urquhart C, Hardman J. Tapping the educational potential of Face-book: guidelines for use in higher education. Educ Inform Technol. 2012:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norgate A, Cattral M, Schiff J, Selzener M, McGilvray I, Bazerbachi F. Abstracts 24th Intern Meet Transplantation. Berlin: 2012. Jul, Raising Awareness through Public and Media Relations; Is it Marketing or Education? (Poster) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nielson Newswire: Research shows link between online brand metrics and offline sales. http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/news-wire/2011/research-shows-link-between-on-line-brand-metrics-and-offline-sales.html.

- 35.Petersen A, Bowman D. Engaging whom and for what ends? Australian stakeholders’ constructions of public engagement in relation to nanotechnologies. ESEP. 2012;12:67–79. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma M, Dollar K, Kibler JL, Sarpong D, Samuels D. The effects of priming on a public health campaign targeting cardiovascular risks. Prev Sci. 2011;12:333–338. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noar SM. A 10-year retrospective of research in health mass media campaigns: where do we go from here? J Health Commun. 2006;11:21–42. doi: 10.1080/10810730500461059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryfe DM. Does deliberative democracy work? Annu Rev Polit Sci. 2005;8:49–71. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vogt TM, Glass A, Glasgow RE, La Chance PA, Lichtenstein E. The safety net: a cost-effective approach to improving breast and cervical cancer screening. J Womens Health. 2003;12:790–798. doi: 10.1089/154099903322447756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santoyo-Olsson J, Phan L, Stewart AL, Kaplan C, Moreno-John G, Napoles AM. A randomized trial to assess the effect of a research informational pamphlet on telephone survey completion rates among older Latinos. Con-temp Clin Trials. 2012:33624–33627. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hsu J, Zinsou C, Parkhurst J, N’Dour M, Foyet L, Mueller DH. Comparative costs and cost-effectiveness of behavioural interventions as part of HIV prevention strategies. Health Policy Plan. 2013;28:20–29. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paul CL, Redman S, Sanson-Fisher RW. A cost-effective approach to the development of printed materials: a randomized controlled trial of three strategies. Health Educ Res. 2004;19:698–706. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. [accessed April 3, 2013];US Department of Health and Human Services: Regulatory changes in ANPRM. http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/anprm-changetable.html.

- 44.Petrini C. ‘Broad’ consent, exceptions to consent and the question of using biological samples for research purposes different from the initial collection purpose. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shickle D. The consent problem within DNA biobanks. Stud Hist Philos Biol Biomed Sci. 2006;37:503–519. doi: 10.1016/j.shpsc.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCarty CA, Chapman-Stone D, Derfus T, Giampietro PF, Fost N. Marshfield Clinic PMRP Community Advisory Group: Community consultation and communication for a population-based DNA biobank: the Marsh-field clinic personalized medicine research project. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:3026–3033. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’Doherty KC, Burgess MM, Edwards K, Gallagher RP, Hawkins AK, Kaye J, McCaffrey V, Winickoff DE. From consent to institutions: designing adaptive governance for genomic biobanks. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mongoven A, McGee H. IRB review and public health biobanking: a case study of the Michigan BioTrust for Health. IRB. 2012;34:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Campbell AV. Ethical challenges of genetic databases: safeguarding altruism and trust. Kings Law J. 2007;18:227–246. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harmon SHE, Laurie G, Haddow G. Governing risk, engaging publics and engendering trust: new horizons for law and social science? Sci Public Policy. 2013;40:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hughes A. Using Social Media Platforms to Amplify Public Health Messages. 2010 http://smexchange.ogilvypr.com/2010/11/using-social-media-platforms-to-amplify-public-health-messaging/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.