Abstract

The chemical content of water-soluble organic carbon (WSOC) as a function of particle size was characterized in Little Rock, Arkansas in winter and spring 2013. The objectives of this study were to (i) compare the functional characteristics of coarse, fine and ultrafine WSOC and (ii) reconcile the sources of WSOC for periods when carbonaceous aerosol was the most abundant particulate component. The WSOC accounted for 5 % of particle mass for particles with δp > 0.96 μm and 10 % of particle mass for particles with δp < 0.96 μm. Non-exchangeable aliphatic (H–C), unsaturated aliphatic (H–C–C=), oxygenated saturated aliphatic (H–C–O), acetalic (O–CH–O) and aromatic (Ar–H) protons were determined by proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR). The total non-exchangeable organic hydrogen concentrations varied from 4.1 ± 0.1 nmol m−3 for particles with 1.5 < δp < 3.0 μm to 73.9 ± 12.3 nmol m−3 for particles with δp < 0.49 μm. The molar H/C ratios varied from 0.48 ± 0.05 to 0.92 ± 0.09, which were comparable to those observed for combustion-related organic aerosol. The R–H was the most abundant group, representing about 45 % of measured total non-exchangeable organic hydrogen concentrations, followed by H–C–O (27 %) and H–C–C= (26 %). Levoglucosan, amines, ammonium and methanesulfonate were identified in NMR fingerprints of fine particles. Sucrose, fructose, glucose, formate and acetate were associated with coarse particles. These qualitative differences of 1H-NMR profiles for different particle sizes indicated the possible contribution of biological aerosols and a mixture of aliphatic and oxygenated compounds from biomass burning and traffic exhausts. The concurrent presence of ammonium and amines also suggested the presence of ammonium/aminium nitrate and sulfate secondary aerosol. The size-dependent origin of WSOC was further corroborated by the increasing δ13C abundance from −26.81 ± 0.18 ‰ for the smallest particles to −25.93 ± 0.31 ‰ for the largest particles and the relative distribution of the functional groups as compared to those previously observed for marine, biomass burning and secondary organic aerosol. The latter also allowed for the differentiation of urban combustion-related aerosol and biological particles. The five types of organic hydrogen accounted for the majority of WSOC for particles with δp > 3.0 μm and δp < 0.96 μm.

1 Introduction

Atmospheric aerosols affect climate directly by absorption and scattering of incoming solar radiation and indirectly through their involvement in cloud microphysical processes (Pöschl, 2005; Ghan and Schwartz, 2007). They also influence atmospheric oxidative burden, visibility and human health (Sloane et al., 1991; Cho et al., 2005; Schlesinger et al., 2006). Organic carbon (OC) represents more than 40 % of aerosol mass in urban and continental areas, with the largest fraction of that being soluble in water, yet less than 20 % of that is chemically characterized (Putaud et al., 2004; Goldstein and Galbally, 2007). Moreover, the optical (absorption coefficient (σ (λ)), single scattering albedo (ωo)) and hydrophilic (vapor pressure ( ), evaporation, condensation and repartitioning) properties of organic aerosol cannot be described by any mathematical formulation of the properties of single compounds, since they are related to the number and type of chromophore (i.e., functional) groups and supra-molecular non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen and van der Walls bonds) (Kavouras and Stephanou, 2002; Cappa et al., 2008; Rincon et al., 2009; Reid et al., 2011). Consequently, the incomplete characterization and the heterogeneity of organic aerosol limit our understanding of their fate and impacts.

OC is composed of primary and secondary compounds originating from anthropogenic and biogenic sources. The water-soluble fraction of organic carbon (WSOC) accounts for 30–90 % of OC, and it is composed of dicarboxylic acids, keto-carboxylic acids, aliphatic aldehydes and alcohols, saccharides, saccharide anhydrides, amines, amino acids, aromatic acids, phenols, organic nitrates and sulfates, and humic and fulvic acids (Timonen et al., 2008; Miyazaki et al., 2009; Pietrogrande et al., 2013; Wozniak et al., 2013). Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectroscopy has been applied to characterize the WSOC content of urban, biogenic, marine, continental background and marine aerosol (Suzuki et al., 2001; Graham et al., 2002; Matta et al., 2003; Cavalli et al., 2004; Decesari et al., 2006, 2011; Finessi et al., 2012). Solid-state 13C cross polarized magic angle spinning (13C-CPMAS) NMR was also used to characterize atmospheric aerosol (Subbalakshmi et al., 2000; Sannigrahi et al., 2006). In addition, the secondary organic aerosol (SOA) composition was studied using two-dimensional (2-D) 1H–1H correlation spectroscopy (COSY) and 1H–13C heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectroscopy (Tagliavini et al., 2006; Maksymiuk et al., 2009). The analysis of the WSOC hydrophobic fraction by 1H and 2-D 1H–1H gradient COSY (gCOSY) NMR allowed for the detection of alkanoic acids based on resonances attributed to terminal methyl (CH3) at δ0.8 ppm, n-methylenes (nCH2) at δ1.3 ppm, and α-and β-methylenes (αCH2, βCH2) at δ2.2 ppm and δ1.6 ppm (Decesari et al., 2011). Carbohydrates and polyhydroxylated polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons were identified on urban surface films in Toronto, Canada by 1H, 2-D 1H–1H total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) and semi-solid-state NMR (Simpson et al., 2006).

Cluster and positive matrix factorization (PMF) were applied to 21 1H-NMR spectra using 200 (and 400) NMR bands as variables in Mace Head, Ireland (Decesari et al., 2011). Despite the inherent statistical errors associated with the use of a limited number of equations (samples, n = 21) to predict substantially more variables (m = 200 or m = 400), three to five factors were retained and assigned to methanesulfonate (MSA), amines, clean marine samples, polluted air masses and clean air masses. PMF was also applied to NMR and aerosol mass spectrometer data to apportion the sources of biogenic SOA in the boreal forest (Finessi et al., 2012). The four retained factors were attributed to glycols, humic-like compounds, amines + MSA and biogenic terpene-SOA originating from a polluted environment.

The overall aim of this study was to determine the compositional fingerprints of particulate WSOC for different particle sizes of urban aerosol in Little Rock, Arkansas. The specific objectives were to (i) compare the functional characteristics of coarse, fine and ultrafine WSOC and (ii) to reconcile the sources of WSOC by NMR spectroscopy and 13C isotope ratios. The Little Rock/North Little Rock metropolitan area is a mid-sized Midwestern urban area with PM2.5 (particles with diameter less than 2.5 μm) levels very close to the newly revised annual PM2.5 national ambient air quality standard of 12 μg m−3 (Chalbot et al., 2013a). OC was the predominant component, representing approximately ~ 55 % of PM2.5 mass, with the highest concentrations being measured during winter. The sources of fine atmospheric aerosol in the region included primary traffic particles, secondary nitrate and sulfate, biomass burning, diesel particles, aged/contaminated sea salt and mineral/road dust (Chalbot et al., 2013a). The region also experiences elevated counts of pollen in early spring due to the pollination of oak trees (Dhar et al., 2010). Due to the seasonal variation of weather patterns, the chemical content of aerosol may also be modified by regional transport of cold air masses from the Great Plains and Pacific Northwest in the winter (Chalbot et al., 2013a).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sampling

Seven-day urban size fractionated aerosol samples were collected every second week with a high-volume sampler in Little Rock, Arkansas in the winter and early spring of 2013 (February–March). The sampling duration was selected to reduce the effect of sampling biases (i.e., weekday/weekend or day/night) and obtain sufficient quantities for NMR analysis in each particle size range. The sampling site was located at the north end of the UAMS campus (34°45′3.69″ N and 92°19′10.28″ W). It was 20 m above the ground and approximately 100 m from West Markham Street with annual average daily traffic (AADT) of 13 000 vehicles. The I-630 Expressway is located 1 mile to the south of the sampling site (south end of the UAMS campus) with an AADT of 108 000 vehicles. The 6-lane (3 per direction) highway is an open below surface-level design to reduce air pollution and noise in the adjacent communities.

A five-stage (plus backup filter) Sierra Andersen Model 230 Impactor mounted on a high-volume pump was used (GMWL-2000, Tisch Environmental, Ohio, USA). Particles were separated into six size fractions on quartz fiber filters, according to their aerodynamic cutoff diameters at 50 % efficiency: (i) first stage: > 7.2 μm; (ii) second stage: 7.2–3.0 μm; (iii) third stage: 3.0–1.5 μm; (iv) fourth stage: 1.5–0.96 μm; (v) fifth stage: 0.96–0.5 μm; and (vi) backup filter: < 0.5 μm, at a nominal flow rate of 1.13 m3 min−1. We assumed an upper limit of 30 μm for the larger particles, in agreement with the specification for the effective cut point for standard high-volume samplers and to facilitate comparison with previous studies (Kavouras and Stephanou, 2002). After collection, filters were placed in glass tubes and stored in a freezer at −30 °C until extraction and analysis.

2.2 Materials

Quartz microfiber filters were purchased from Whatman (QM-A grade, 203 × 254 mm, Tisch Environmental, USA), were precombusted at 550 °C for 4 h and then kept in a dedicated clean glass container, with silica gel, to avoid humidity and contamination. Water (HPLC grade), deuterium oxide (NMR grade, 100 at. % D), 3-(trimethylsilyl)propionic acid-d4 sodium salt (98 at. % D), sodium phosphate buffer (for analysis, 99 %) and sodium azide (extra pure, 99 %) were purchased from Acros Organics (Fisher Scientific Company LLC, USA).

2.3 Analysis

A piece of the filters (1/10 of impactor stages (12.5 cm2) and 5.1 cm2 of the backup) was analyzed for δ13C by an elemental analyzer (NC2500 Carlo Erba, Milan Italy) interfaced via a Conflo III to a Delta Plus isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Thermo Finnigan, Bremen Germany) at the University of Arkansas Stable Isotope Laboratory. The samples were combusted at 1060 °C in a stream of helium with an aliquot of oxygen. Nitrogen oxides are reduced in a copper furnace at 600 °C. Resultant gases are separated using a 3 m chromatography column at 50 °C. Raw data are created using monitor gases, pure nitrogen and carbon dioxide. Raw results are normalized to the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) using a combination of certified and in-house standards (Nelson, 2000). The relative isotope differences are expressed in permil versus VPDB calculated as follows:

| (1) |

where R((13C/12C)sample) and R((13C/12C)standard) (VPDB) are the carbon isotope ratios of the sample and the standard, respectively (Coplen, 2011).

A 1 cm2 piece of each filter was extracted in 1 mL deionized water and an aliquot (20 μL) was analyzed for WSOC using a DRI Model 2001 Thermal/Optical thermal optical reflectance (TOR) carbon analyzer (Atmoslytic Inc., Calabasas, CA) following the Interagency Monitoring of PROtected Visual Environments (IMPROVE) thermal/optical reflectance (TOR) protocol at DRI’s Environmental Analysis Facility (Ho et al., 2006).

The remaining portion of each filter was extracted in 50 mL of ultrapure H2O for 1 h in an ultrasonic bath. The aqueous extract was filtered on a 0.45 μm polypropylene filter (Target2, Thermo Scientific), transferred into a pre-weighted vial (for the gravimetric determination of the total water-soluble extract, TWSE), dried using a SpeedVac apparatus and re-dissolved in 500 μL of deuterated water (D2O). A microbalance (Mettler-Toledo, model AB265-S) with a precision of 10 μg was used in a temperature-controlled environment. To minimize any variation in the pH of the samples and to block microbial activity, 100 μL of a buffer solution of disodium phosphate/monosodium phosphate (0.2 M Na2HPO4/0.2 M NaH2PO4, pH 7.4) and 100 μL of sodium azide (NaN3) (1 % w/w) were added into the sample, respectively. The 1H-NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker Avance 500 MHz instrument equipped with a 5 mm double-resonance broad band (BBFO Plus Smart) probe at 298 K with 3600 scans, using spin lock, an acquisition time of 3.2 s, a relaxation delay of 1 s, and 1 Hz exponential line broadening and presaturation to the H2O resonance (Chalbot et al., 2013b). Spectra were apodized by multiplication, with an exponential decay corresponding to 1 Hz line broadening in the spectrum and a zero filling factor of 2. The baseline was manually corrected and integrated using the Advanced Chemistry Development NMR processor (Version 12.01 Academic Edition). The determination of chemical shifts (δ1H) was done relative to that of trimethylsilyl-propionic acid-d4 sodium salt (TSP-d4) (set at 0.0 ppm). The segment from δ4.5 ppm to δ5.0 ppm, corresponding to the water resonance, was removed from all NMR spectra. We applied the icoshift algorithm to align the NMR spectra (Savorani et al., 2010) and integrated the intensity of signals of individual peaks as well as in five ranges (Decesari et al., 2000, 2001; Suzuki et al., 2001). The saturated aliphatic region (H–C, δ0.6–δ1.8 ppm) was assumed to include protons from methyl, methylene and methine groups (R–CH3, R–CH2, and R–CH, respectively). The unsaturated aliphatic region (H–C–C=, δ1.8–δ3.2 ppm) contained signals of protons bound to aliphatic carbon atoms adjacent to a double bond, including allylic (H–C–C=C), carbonyl (H–C–C=O) or imino (H–C–C=N) groups. Secondary or tertiary amines (H–C–NR2) may also be present in the δ2.2–δ2.9 ppm region. The oxygenated saturated aliphatic region (H–C–O, δ3.2–δ4.4 ppm) contained alcohols, ethers and esters. The fourth region included acetalic protons (O–CH–O) with signals of the anomeric proton of carbohydrates and olefins (long-chain R–CH=CH–R, δ5.0–δ6.4 ppm). Finally, the fifth region (δ6.5–δ8.3 ppm) contained aromatic protons (Ar–H).

2.4 Calculations

The Lundgren diagrams and mass median aerodynamic diameter (MMAD) were used to describe the size distribution of particle mass, WSOC and non-exchangeable organic hydrogen concentrations ( ) as follows (Van Vaeck and Van Cauwenberghe, 1985; Kavouras and Stephanou, 2002):

| (2) |

where C is the concentration (μg m−3) for a given stage, δp is the aerodynamic diameter (μm), and Ct is the total concentration (μg m−3).

MMAD denotes the particle diameter (μm) with half of the particle mass, TWSE, WSOC or non-exchangeable organic hydrogen concentration above and the other half below. It was calculated stepwise as follows:

| (3) |

where δ1 is the lower particle size (μm) for the i-impactor stage; Ci and Cj are the mass concentrations for the i- and j -impactor stages, respectively. If MMAD was higher than the upper particle size collected by the i-impactor stage, the calculation was repeated for the next stage. MMAD was calculated for the entire particle range, coarse particles (higher than 3.0 μm) and fine particles (less than 3.0 μm).

Multivariate linear regression analysis was used to attribute WSOC (in nmol m−3) to carbon associated with five types of non-exchangeable organic hydrogen as follows:

| (4) |

where α1, α2, α3, α4 and α5 are the regression coefficients of non-exchangeable R–H, H–C–C=, O–C–H, O–CH–O and Ar–H concentrations (in nmol m−3). The intercept, α0, accounted for carbon not associated with the five organic hydrogen types such as carboxylic. The coefficient of variation of the root mean square error, CV(RMSE), was used to evaluate the residuals between measured and predicted WSOC values. It was defined as the RMSE normalized to the mean of the observed values:

| (5) |

with RMSE being defined as the sample standard deviation of the differences between predicted values and observed values, n is the number of measurements and is the average WSOC concentration.

3 Results and discussion

Table 1 shows the ambient temperature (°C), barometric pressure (torr), concentrations of major aerosol types and concentration diagnostic ratios of PM2.5 aerosol during the monitoring period at Little Rock at the nearest PM2.5 chemical speciation site (EPA AIRS ID: 051190007; Lat.: 34.756072°N; Long.: 92.281139°W) (Chalbot et al., 2013a). The site is located 3.6 km ENE (heading of 77.9°) of the UAMS campus. The Interagency Monitoring of PRO-tected Visibility Environments (IMPROVE) PM2.5 mass re-construction scheme was used to estimate the mass of the secondary inorganic (sulfate and nitrate) aerosol, organic mass, elemental carbon, soil dust and sea spray (Sisler, 2000).

Table 1.

Major aerosol types and diagnostic ratios of PM2.5 chemical species in Little Rock, Arkansas during the study period.

| Variable | Value (mean ± st. error) | Ratio | Value (mean ± st. error) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambient temperature (°C) | 10.6 (6.4–16.6) | OE/EC | 4.58 ± 1.06 | |

| Barometric pressure (torr) | 758 (756–762) | Molar | 3.07 ± 0.29 | |

| Organic mass (μg m−3) | 5.5 ± 0.9 |

|

2.66 ± 0.90 | |

| Elemental carbon (μg m−3) | 0.7 ± 0.1 | K+/K | 1.00 ± 0.28 | |

| Ammonium sulfate and nitrate (μg m−3) | 4.4 ± 1.6 | K/Fe | 0.87 ± 0.25 | |

| Soil dust (μg m−3) | 0.5 ± 0.1 | Ni/V | 0.44 ± 0.41 | |

| Sea spray (μg m−3) | 0.1 ± 0.1 | Al/Si Al/Ca |

0.40 ± 0.20 1.71 ± 0.82 |

Organic carbon (OC) was the predominant component of fine aerosol, accounting for 49 % of reconstructed PM2.5 mass, followed by secondary inorganic aerosol (40 %) and elemental carbon (EC) (7 %), which were comparable to those previously observed for the 2002–2010 period. The OC/EC ratio (4.58 ± 1.06) was comparable to those observed in the same region for the 2000–2010 period (Chalbot et al., 2013a) that identified biomass burning and traffic as the most important sources of carbonaceous aerosol in the region. This was further corroborated by the prevalence of soluble potassium, a tracer of biomass burning (K+/K ratio of 1.00 ± 0.28) (Zhang et al., 2013). The low K/Fe ratio (0.87 ± 0.25) and the ratios of mineral elements (Al, Si and Ca) were comparable to those previously observed in the US demonstrating the presence of soil dust (Kavouras et al., 2009; Chalbot et al., 2013a). The high molar ratio suggested the complete neutralization of sulfate by ammonia, while the suggested the presence of other forms of S from oil and coal combustion.

3.1 Size distribution

The mean (± standard error) of particle mass, total water soluble extract (TWSE), WSOC and non-exchangeable organic hydrogen concentrations for the five regions (R–H, H–C–C=, H–C–O, O–CH–O and Ar–H) for each particle size range are presented in Table 2. In Table 2, the mean (± standard error) molar H/C ratio and δ13C for each particle size are also reported. The total particle mass concentration ranged from 1.6 ± 0.1 μg m−3 for particles with 0.96 < δp < 1.5 μm to 11.2 ± 2.8 μg m−3 for particles with δp < 0.49 μm. These levels were substantially lower than those measured in other urban areas but comparable to those observed in forests (Kavouras and Stephanou, 2002). The lowest and highest TWSE concentrations were 0.5 ± 0.1 μg m−3 and 5.4 ± 1.4 μg m−3, accounting for about 13 % of the largest (δp > 7.2 μm) and up to 61 % of the smallest particles (δp < 0.96 μm), respectively. The WSOC levels were 0.1 ± 0.1 μgC m−3 for particles with δp > 0.96 μm representing 10 % of TWSE and 5 % of particle mass and increased to 1.2 ± 0.1 μgC m−3 (22.2 % of TWSE and 10 % of particle mass) for particles with δp < 0.96 μm. The contribution of WSOC to particle mass was slightly higher than that computed in Hong Kong for PM10 particles, albeit at substantially lower levels (Ho et al., 2006). For comparison, the WSOC concentrations of size-fractionated aerosol collected during the dry season in the Amazon varied from 0.2 (3.5–10 μm) to 30.4 μgC m−3 (0.42–1.2 μm) (Tagliavini et al., 2006). The total non-exchangeable organic hydrogen concentrations varied from 4.1 ± 0.1 nmol m−3 for particles with 0.96 < δp < 1.5 μm to 73.9 ± 12.3 nmol m−3 for particles with δp < 0.49 μm, with R–H being the most abundant group, representing about 45 % of measured total non-exchangeable organic hydrogen concentrations followed by H–C–O (27 %) and H–C–C= (26 %).

Table 2.

Particle mass, TWSE, WSOC and non-exchangeable organic hydrogen concentrations and δ13C at each impactor stage for urban aerosol.

| Diameter (μm) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30–7.2 μm | 7.2–3.0 μm | 3.0–1.5 μm | 1.5–0.96 μm | 0.96–0.49 μm | < 0.49 μm | |

| Particle mass (μg m−3) | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 11.2 ± 2.8 |

| TWSE (μg m−3) | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 1.4 |

| WSOC (μg m−3) | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| Total organic H (nmol m−3) | 12.5 ± 0.9 | 7.8 ± 1.0 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 5.7 ± 1.3 | 17.4 ± 3.5 | 73.9 ± 12.3 |

| R–H (nmol m−3) | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0 | 2.6 ± 1.4 | 9.1 ± 2.5 | 33.8 ± 11.9 |

| H–C–C= (nmol m−3) | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 6.4 ± 1.9 | 19.3 ± 8.4 |

| H–C–O (nmol m−3) | 9.0 ± 1.2 | 4.2 ± 1.6 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 20 ± 2.7 |

| O–CH–O (nmol m−3) | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.4 |

| Ar–H (nmol m−3) | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.2 |

| Molar H / C ratio | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.92 ± 0.09 | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 0.54 ± 0.05 | 0.73 ± 0.02 |

| δ13C | −25.93 ± 0.31 | −25.83 ± 0.19 | −25.61 ± 0.05 | −26.13 ± 0.11 | −26.76 ± 0.22 | −26.81 ± 0.18 |

The molar H/C ratio may provide information on the types of sources; however, it should be cautiously evaluated because of the inherent inability to identify exchangeable protons in hydroxyl, carboxylic and amine functional groups at neutral pH values by 1H-NMR (Duarte et al., 2007). H/C values higher than 2 were indicative of compounds with strong aliphatic components, while H/C values from 1 to 2 were typically associated with oxygenated or nitro-organic species, and H/C values lower than 1 suggested an aromatic signature (Fuzzi et al., 2001). The H/C molar ratios were 0.84 ± 0.02 and 0.92 ± 0.09 for particles with δp > 3.0 μm, decreased to 0.48 ± 0.05 for particles with 0.96 < δp < 3.0 μm and increased to 0.54 ± 0.05 and 0.73 ± 0.02 for smaller particles (δp < 0.96 μm). In a previous study, the molar H/C ratios for vegetation combustion and prescribed fire emissions collected very close to the fire front were 0.39 and 0.64–0.68, respectively, suggesting a strong polyaromatic content that was typically observed in combustion-related processes (Adler et al., 2011; Chalbot et al., 2013b).

The normalized concentration-based size distributions (i.e., Lundgren diagrams, Van Vaeck and Van Cauwenberghe, 1985) of particle mass, TWSE, WSOC and total non-exchangeable organic hydrogen concentrations are presented in Fig. 1a and b, respectively. Table 3 also shows the mass median aerodynamic diameter for each measured variable. Particle mass and TWSE followed a bimodal distribution with local maxima for particles with 0.49 < δp < 1.5 μm and 3.0 < δp < 7.2 μm. The first mode (i.e., fine particles) corresponded to MMADs of 0.39 ± 0.03 μm for particle mass and 0.39 ± 0.02 μm for TWSE, which was typical of those observed in other urban areas (Table 3) (Aceves and Grimalt, 1993; Kavouras and Stephanou, 2002). The MMADs of particle mass and TWSE for the second mode (i.e., coarse particles) were 9.15 ± 2.75 μm and 6.35 ± 0.45 μm, suggesting the presence of water-insoluble species (e.g., metal oxides) in larger particles (δp > 7.2 μm). The MMADs calculated for the whole range of particle sizes were 0.68 ± 0.48 μm and 0.46 ± 0.02 μm for particle mass and TWSE, respectively. This confirmed the accumulation of water-soluble species in the fine range. For WSOC and non-exchangeable organic hydrogen, the size distribution illustrated a one-mode pattern maximizing at particles with 0.49 < δp < 1.5 μm and corresponding to MMADs for the whole range of particle sizes of 0.43 ± 0.02 μm for WSOC and 0.41 ± 0.01 μm for non-exchangeable organic hydrogen. Coarse particles (> 3.0 μm) had an MMAD of 11.83 ± 2.20 μm for WSOC and 11.35 ± 1.45 μm, which was substantially higher than that computed for particle mass and TWSE, indicating the possible contribution of very large carbonaceous particles. Pollen particles from oak trees (Quercus) have diameters from 6.8 to 37 μm and only 10 % of them are present in smaller particles (0.8–3.1 μm) (Takahashi et al., 1995). The particle diameter of various types of tree and grass pollen ranged from 22 to 115 μm (Diehl et al., 2001). On the other hand, the fine particle MMADs for WSOC and non-exchangeable organic hydrogen of fine particles were 0.37 ± 0.01 μm and 0.34 ± 0.01 μm (comparable to those computed for particle mass and TWSE), indicating the considerable influence of WSOC on TWSE and particle mass in this size range.

Figure 1.

Size distribution for urban particle mass and TWSE (a), WSOC and non-exchangeable organic hydrogen (b), molar H / C ratio (c) and δ13C (d).

Table 3.

Mass median aerodynamic diameter (in μm) of particle mass, TWSE, WSOC and non-exchangeable organic hydrogen.

| Total | Coarse | Fine | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle mass | 0.68 ± 0.19 | 9.15 ± 2.75 | 0.39 ± 0.03 |

| TWSE | 0.46 ± 0.02 | 6.35 ± 0.45 | 0.39 ± 0.02 |

| WSOC | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 11.83 ± 2.20 | 0.37 ± 0.01 |

| Organic hydrogen | 0.41 ± 0.01 | 11.35 ± 1.45 | 0.34 ± 0.01 |

| R–H | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 7.00 ± 0.01 | 0.34 ± 0.01 |

| H–C–C= | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 7.13 ± 0.03 | 0.37 ± 0.02 |

| O–C–H | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 13.05 ± 1.95 | 0.31 ± 0.01 |

| O–CH–O | 0.73 ± 0.07 | 10.25 ± 0.25 | 0.40 ± 0.04 |

| Ar–H | 1.25 ± 0.65 | 10.10 ± 0.90 | 0.53 ± 0.12 |

3.2 Functional characterization

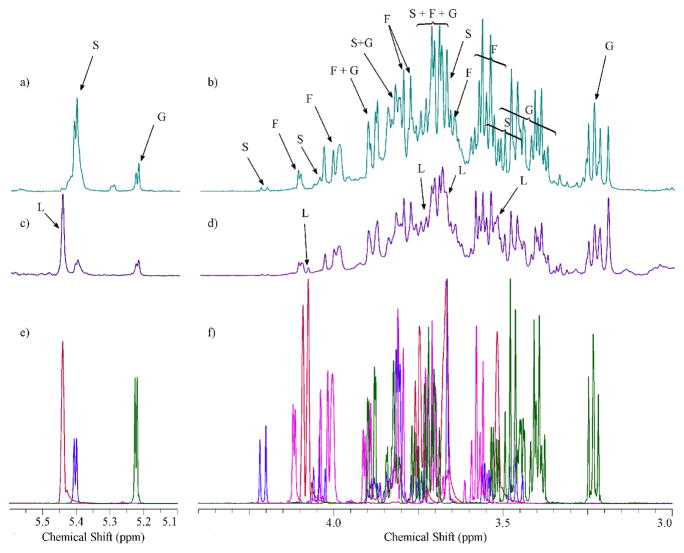

The 1H-NMR spectra of WSOC for different particle sizes are shown in Fig. 2. The structure of the compounds identified and the hydrogen assignment are shown in Fig. 3. The spectra are characterized by a combination of sharp resonances of the most abundant organic species and convoluted resonances of many organic compounds present at low concentrations. This section describes the variability of 1H-NMR spectra for different particles sizes in qualitative terms. A limited number of resonances were assigned to specific organic compounds using reference NMR spectra and in comparison with previous studies (Wishart et al., 2009).

Figure 2.

500 MHz 1H-NMR of size-fractionated WSOC. The segment from δ4.5 to δ5.0 ppm was removed from all NMR spectra due to H2O residues. The peaks were assigned to specific compounds as follows: formate (Fo), levoglucosan (L), glucose (G), sucrose (S), methanesulfonate (MSA), trimethylamine (TMA), succinate (Su), acetate (A), dimethylamine (DMA), monomethylamine (MMA), fructose (F), trigonelline (T), phthalic acid (PA), terephthalic acid (TA), ammonium ions ( ).

Figure 3.

Structures of compounds assigned from the NMR spectra of fractionated aerosols. The protons responsible for the NMR signals are colored as follows: brown (bound to carbon alpha of the carboxylic acid group), orange (methyl groups bound to amines), light blue (bound to carbon alpha of the sulfonic acid group), green (glucose), blue (sucrose), purple (fructose), red (levoglucosan), light green (aromatic hydrogen). The H in bold indicates the signals in the 5.1–5.7 ppm range (see Fig. 4).

The predominant peaks for particles with δp < 0.49 μm were those in the δ0.8 ppm to δ1.8 ppm range, with a somewhat bimodal distribution maximizing at δ ~ 0.9 ppm and δ ~ 1.3 ppm, respectively. They had previously been attributed to terminal methyl groups, alkylic protons and protons bound on C=O in compounds with a combination of functional groups and long aliphatic chains (Decesari et al., 2001). The 1H-NMR fingerprint in this region was comparable to that obtained for soil humic compounds, atmospheric humic-like species and urban traffic aerosol (Suzuki et al., 2001; Bartoszeck et al., 2008; Song et al., 2012; Chalbot et al., 2013b). It was previously observed that long chain (C6–C30) n-alkanoic acids, n-aldehydes and n-alkanes accumulated in particles with δp < 0.96 μm (Kavouras and Stephanou, 2002). The intensity of the convoluted resonances decreased for increasing particle sizes.

In the δ1.8–3.2 ppm range, the sharp resonances at δ1.92 ppm and δ2.41 ppm were previously assigned to aliphatic protons in α position in the COOH group in acetate (H-4 in Fig. 3) and in succinate (H-4 and H-5 in Fig. 3). These species were observed in the coarse fraction (Fig. 2e–f) but not in fine and ultrafine particles (Fig. 2a–c). These two acids (as well as formate) were typically associated with photo-oxidation processes and were present in the accumulation mode; however, Matsumoto et al. (1998) demonstrated that they were also present in sea spray coarse particles. Coarse acetate and formate were also observed in soil dust particles (Chalbot et al., 2013b).

The CH3 in mono-, di- and tri-methylamines (Fig. 3) was allocated to sharp resonances at δ2.59, δ2.72, and δ2.92 ppm, respectively. The major source of amines was animal husbandry and they were co-emitted with ammonia (Schade and Crutzen, 1995). They were present as vapors but they partition to aerosol phase by forming non-volatile aminium salts through scavenging by aqueous aerosol and reactions with acids, gas-phase acid–base reactions and displacement of ammonia from pre-existing salts (VandenBoer et al., 2011). The three amines were observed in particles with δp < 0.96 μm, which was consistent with previous studies and the suggested gas-to-particle partitioning mechanism (Mueller et al., 2009; Ge et al., 2011). Nitrate and sulfate particles constituted a considerable fraction of fine particles in Little Rock, Arkansas and it was associated with transport of air masses over the Great Plains and Upper Midwest, two regions with many animal husbandry facilities and the highest NH3 emissions in the US (Chalbot et al., 2013a). The presence of aminium/ammonium salts in the water-soluble fraction was also verified by the strong ammonium 1H–14N coupling signals at δ7.0–7.4 ppm (1 : 1 : 1 triplet, JHN ~ 70 Hz) (Suzuki et al., 2001). Methanesulfonic acid (MSA) was also present (CH3 at δ2.81 ppm). MSA is a tracer of marine aerosols, formed from dimethylsulfide oxidation. We previously demonstrated the contribution of marine aerosols originating from the Gulf of Mexico in Little Rock (Chalbot et al., 2013a). MSA was accumulated to fine and ultrafine particles (δp < 1.5 μm) (Fig. 2d–f).

Two segments of the carbohydrate region (δ3.0–4.4 ppm and δ5.1–5.6 ppm) of the 1H-NMR spectra for the largest and smallest particles sizes are presented in Fig. 4a–d, respectively. In addition, Fig. 4e and f show the combination of individual NMR reference spectra for glucose (HMDB00122), sucrose (HMDB00258), fructose (HMDB00660) and levoglucosan (HMDB00640) retrieved from the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) NMR databases (Wishart et al., 2009). The 1H-NMR spectra of size-fractionated WSOC contain both convoluted resonances illustrated by a broad envelope in the spectra, and sharp resonances. For particles with δp > 7.2 μm, the spectra were dominated by sharp resonances assigned to glucose (G in Fig. 2; H-3, multiplet at δ3.24 ppm; H-5, multiplet at δ3.37–3.43 ppm; H-6, multiplet at δ 3.44–3.49 ppm; H-3, multiplet at δ3.52 ppm; H-4, multiplet at δ3.68–3.73 ppm; H-11, multiplet at δ3.74–3.77 ppm and 3.88–3.91 ppm; H-6 and H-11, multiplet at 3.81–3.85 ppm; and alpha H-2, doublet at 5.23 ppm), sucrose (S in Fig. 2; H-10, multiplet at 3.46 ppm; H-12, multiplet at 3.55 ppm; H-13, singlet at δ3.67 ppm; H-11, multiplet at 3.75 ppm; H-17 and H-19, multiplet at δ3.82 ppm; H-9, multiplet at 3.87 ppm; H-5, multiplet at 3.89 ppm; H-4, multiplet at δ4.06 ppm; H-3, doublet at δ4.22 ppm and H-7, doublet at 5.41 ppm) and fructose (F in Fig. 2; H-7, multiplet at δ3.55–3.61 ppm; H-7 and H-11, multiplet at δ3.66–3.73 ppm; H-3, H-5 and H-11, multiplet at δ3.79–3.84 ppm; H-4, multiplet at δ3.89–3.91 ppm; H-5 and H-11, multiplet at δ3.99–4.04 ppm; H-3 and H-4, multiplet at δ4.11–4.12 ppm). The overall NMR profile in this range was comparable to that observed for the combination of glucose, sucrose and fructose reference spectra (Fig. 4e and f) and atmospheric pollen (Chalbot et al., 2013c). The intensity of proton resonances in the δ3.30–4.15 ppm range was highest for the largest (δp > 7.2 μm) and smallest (δp < 0.49 μm) particles and decreased approximately eight times for particles in the 0.96 < δp < 1.5 μm size range (Fig. 2a–f). Carbohydrates of biological origin (i.e., pollen) were typically associated with large particles; however, they were also observed in fine biomass burning or biogenic aerosols (Bugni and Ireland, 2004; Medeiros et al., 2006; Agarwal et al., 2010; Fu et al., 2012; Chalbot et al., 2013c). The diameter of airborne fragments of fungal and pathogenic material may be < 1 μm, with their highest concentrations being measured in fall and spring (Yamamoto et al., 2012). The presence of sugars in particles with δp < 0.49 μm may be due to particle breakup during sampling, an inherent artifact of impaction (Kavouras and Koutrakis, 2001). It has been shown that this error may account for up to 5 % of the particle mass for particles with diameters higher than the cut-off point of the impactor stage. In our study, this would add up to 0.05 nmol m−3 (or 0.2 %) of the non-exchangeable H–C–O concentration to the concentration of particles with δp < 0.49 μm, suggesting the negligible influence of sampling artifacts on the observed size distribution.

Figure 4.

500 MHz δ3.0–4.4 ppm and δ5.1–5.6 ppm 1H-NMR segments for the largest (a, b) and smallest particles sizes (c, d) and reference NMR spectra (e, f) of levoglucosan (red), glucose (green), sucrose (blue) and fructose (purple).

Levoglucosan (H-6, multiplet at δ3.52 ppm; H-7 and H-8, multiplet at δ3.67; H-2, multiplet at δ3.73–3.75 ppm and at 4.08 ppm; H-5, singlet at 5.45 ppm (H-3 at 4.64 ppm; this peak was not visible due to interferences from solvent residues)) was also detected in the carbohydrate region of the ultrafine and fine 1H-NMR. Its concentrations, computed using the resonance at δ5.45 ppm, ranged from 1.1 ng m−3 for particles with δp > 7.2 μm to 19.1 ng m−3 for particles with 0.49 < δp < 0.96 μm. The mean total concentration was 33.1 ng m−3, which was comparable to those observed in US urban areas (Hasheminassab et al., 2013). Levoglucosan was previously observed in the 1H-NMR spectra of aerosol samples dominated by biomass burning in the Amazon (Graham et al., 2002).

A group of very sharp resonances between δ3.23 and δ3.27 ppm was observed with increasing intensity as particle size increased (Fig. 2a–f). These peaks were previously attributed to H–C–X (where X=Br, Cl, or I) functional groups (Cavalli et al., 2004).

The intensities of proton resonances in the aromatic region were very low, accounting for 0.3 to 1.2 % of the total non-exchangeable hydrogen concentration, which was consistent with those observed in other studies (Decesari et al., 2007; Cleveland et al., 2012). Resonances were previously attributed to aromatic amino acids and lignin-derived structures, mainly phenyl rings substituted with alcohols OH, methoxy groups O–CH3 and unsaturated C=C bonds, and their combustion products (Duarte et al., 2008). Four organic compounds were identified by means of their NMR reference spectra. These were formate (Fo in Fig. 2; H-2, singlet at 8.47 ppm), trigonelline (T in Fig. 2; H-4, multiplet at δ8.09 ppm; H-5 and H-3, multiplet at δ8.84 ppm; H-1, singlet at δ9.13 ppm; H-9, singlet at 4.42 ppm), phthalic acid (P in Fig. 2; H-4 and H-5, multiplet at δ7.58 ppm; H-3 and H-6, multiplet at δ7.73 ppm) and terephthalic acid (TA in Fig. 2; H-6, H-2, H-5 and H-3, multiplet at δ8.01). Formate and trigonelline were only observed in particles with δp > 7.2 μm due to the absorption of formate on pre-existing particles and the biological origin of trigonelline (Chalbot et al., 2013c). The phthalic acid and its isomer, terephthalic acid, were only observed in particles with δp < 0.49 μm. These compounds have already been detected in urban areas and vehicular exhausts (Kawamura and Kaplan, 1987; Alier et al., 2013). They may also be formed during the oxidation of aromatic hydrocarbons, but oxidation reactions are not favored by prevailing atmospheric conditions in the winter in the study area (Kawamura and Yasui, 2005).

Overall, the qualitative analysis of 1H-NMR spectra showed the prevalence of sugars in larger particles and a mixture of aliphatic and oxygenated compounds associated with combustion-related sources such as biomass burning and traffic exhausts. The presence of ammonium/aminium salts, probably associated with nitrate and sulfate secondary aerosol, was also identified.

3.3 Source reconciliation

The δ13C ratios and the relative presence of the different types of protons were further analyzed to identify the sources of WSOC. Stable 13C isotope ratios have been estimated for different types of organic aerosol. The compounds associated with marine aerosols emitted via sea spray have δ13C values from −20 to −22 ‰ (Fontugne and Duplessy, 1981), and a decrease in the δ13C to −26 ± 2 ‰ of marine tropospheric aerosols has been associated with the presence of continental organic matter (Cachier et al., 1986; Chesselet et al., 1981). The carbon isotopic ratio of particles from the epicuticular waxes of terrestrial plants is related to the plant physiology and carbon fixation pathways, with C3 plants being less enriched in 13C (from −20 ‰ to −32 ‰) than the C4 plants (−9 to −17 ‰) (Collister et al., 1994; Ballantine, 1998). The δ13C ratios of organic aerosol from combustion of unleaded gasoline and diesel are −24.2 ± 0.6 ‰ and −26.2 ± 0.5 ‰, respectively (Widory et al., 2004). Atmospheric aging during transport increases the isotopic ratios (Aggarwal et al., 2013). In our study, the δ13C values increased from −26.81 ± 0.18 ‰ for the smallest particles (δp < 0.49 μm) to −25.93 ± 0.31 ‰ for the largest particles (δp > 7.2 μm), indicating a size-dependent mixture of anthropogenic and biogenic sources. Figure 5 shows the association (r2 = 0.69) between the WSOC-to-particle mass ratio and δ13C for particles with different sizes. The 13C enrichment of WSOC for low WSOC-to-particle mass ratios indicated the negligible effect of atmospheric aging. The predominance of R–H, moderate H / C ratios and low δ13C for the smaller particles (δp < 0.96 μm) were consistent with the contribution of combustion-related sources (Fig. 1c and d). A high δ13C ratio, the prevalence of oxygenated groups (H–C–O) and a high H / C ratio such as those observed for coarse particles (δp > 3.0 μm) would point towards aged organic aerosol; however, the large size of particles with these characteristics and the low WSOC-to-particle mass ratio suggested the influence of primary biogenic particles (Table 1).

Figure 5.

Association of the 13C isotopic ratio with the WSOC / particle mass ratio.

By plotting the ratios of calculated carboxylics and ketones (H–C–C=O) (by subtraction of the Ar–H from the H–C–C= region) to the total aliphatics (Σ (H–C–)) and H–C–O / Σ (H–C–), Decesari et al. (2007) assigned three areas of the plot to OC sources, namely, biomass burning, marine and secondary organic aerosol. The Σ (H–C–) included the saturated (H–C–O, hydroxyls) and the unsaturated oxygenated (HC–C=O in acids and ketones) groups, the benzylic (H–C–Ar) groups, the unfunctionalized alkyl (H–C) groups, and minor contributions from other aliphatic groups such as the sulfonic group of MSA. More recently, Cleveland et al. (2012) demonstrated the need to define the boundaries for urban and industrial aerosol that were described by moderate H–C–O / Σ (H–C–) and H–C–C=O / Σ (H–C) ratios. Figure 6 depicts the locations of the urban size-fractionated samples collected in this study, in relation to the three aforementioned WSOC sources. Overall, the H–C–C=O / Σ (H–C–) ratio increased and the H–C–O / Σ (H–C–) ratio decreased for decreasing particle sizes. The H–C–C=O / Σ (H–C–) varied from 0.12 to 0.50 and the H–CO / Σ (H–C–) varied from 0.13 to 0.79. The data points for the smaller particles (δp < 1.5 μm) were within the boundaries of biomass burning and SOA, demonstrating the significance of wood burning emissions. The presence of biological aerosol with δp > 3.0 μm yielded low H–C–C=O / Σ (H–C–) ratios with a clear separation from combustion-related processes. These findings, in conjunction with those presented by Decesari et al. (2007) and Cleveland et al. (2012), suggest distinct signatures for different sources of organic aerosol that, once defined, may be used to determine the predominant sources of particulate WSOC.

Figure 6.

Functional group distributions of WSOC for each impactor stage. The boundaries of biomass burning, marine and secondary organic aerosol were obtained from Decesari et al. (2007).

The MMAD for the specific types of organic hydrogen may also provide qualitative information on the origin of organic aerosol. The MMAD of an organic species is found at a significantly smaller particle size than for the total aerosol when condensation (i.e., hot vapors cooling) or a gas-to-particle conversion mechanism prevails. The MMAD for R–H and H–C–C= were comparable, indicating a common origin. Their MMAD values for the total particle size range, coarse particles and fine particles were lower than those computed for particle mass and WSOC that can be interpreted by the condensation of hot vapor emissions from fossil fuel combustion and wood burning. This was further corroborated by the similar MMAD values for the total particle size range and fine particles for R–H and H–C–C=.

However, different trends were observed for O–C–H, O–CH–O and Ar–H. For O–C–H, the MMADs suggested a dual origin: (i) a strong condensation pathway for fine particles with an MMAD value (0.31 ± 0.01 μm) for fine particles that was lower than that for the entire particle size range (0.48 ± 0.02 μm) and fine MMADs for particle mass and WSOC, and (ii) a dominant primary (i.e., direct particle emissions) pathway for coarse particles with the highest MMAD values for all particle metrics in this study (13.05 ± 1.95 μm). Lastly, the high MMAD values for O–CH–O and Ar–H for the entire and fine particle size ranges as compared to those computed for the other types of organic hydrogen, particle mass and WSOC pointed towards emissions of primary particles.

3.4 WSOC reconstruction

In this section, we estimated the contribution of each type of non-exchangeable organic hydrogen to WSOC levels by regression analysis (Eq. 4) without making any assumptions about the H / C ratio. The regression coefficients are estimates of the product of the H / C ratio and the relative presence of the functional group in the overall organic composition. Figure 7a presents a comparison between the measured and calculated WSOC levels and Fig. 7b illustrates the attribution of WSOC concentrations to specific types of carbon using the same definitions as for the non-exchangeable protons, i.e., saturated aliphatic (R–H), unsaturated aliphatic (H–C–C=), oxygenated saturated aliphatic (H–C–O), acetalic (O–CH–O) and aromatic (Ar–H), respectively. There was very good agreement (r2 = 0.99, slope of 0.9964) between measured WSOC and predicted WSOC concentrations with an CV(RMSE) of 0.02 (or 2 %). The R–H carbon was the predominant type of WSOC for particles with δp < 7.2 μm (41–60 %) and declined to 28 % for the largest particles. Similarly, the H–C–C= carbon was the second most abundant WSOC type for particles with δp < 7.2 μm (25–34 %) and declined moderately to 17 % for the largest particles. The H–CO carbon accounted for approximately 49 % of the identified WSOC for particles with δp > 7.2 μm and decreased to 4 % of WSOC for particles with δp < 1.5 μm. The contribution of aromatic carbon to WSOC increased from 2 % for the smallest particles to 6 % for the larger particles, while acetalic carbon accounted for 1 % for all particle size ranges. The WSOC not associated with the five carbon types was negligible (less than 1 %) for particles with δp < 0.49 μm and increased to 47 % of WSOC for particles with 1.5 < δp < 3.0 μm and 22 % for larger particles. The carbon deficit may be related to carbon associated with carboxylic and/or hydroxyl groups and carbon atoms with no C–H bonds (e.g., quaternary C). Alkenoic acids and alcohols in urban environments have been shown to be accumulated in particles with 0.96 < δp < 3.0 μm (Kavouras and Stephanou, 2002). Overall, this analysis showed that aliphatic carbon originating from anthropogenic sources accounted for the largest fraction of fine and ultrafine WSOC. Sugars and other oxygenated compounds associated with biological particles dominated larger particles. Atmospheric aging appeared to be negligible during the monitoring period.

Figure 7.

Measured and predicted WSOC concentrations (a) and contributions of R–H, H–C–C=, H–C–O, O–CH–O and Ar–H on WSOC (b) for each impactor stage of urban aerosol.

4 Conclusions

The functional characteristic of water soluble organic carbon for different particles sizes in an urban area during winter and spring has been studied. Using 1H-NMR fingerprints, 13C isotopic analysis and molecular tracers, the sources of particulate WSOC were reconciled for specific functional organic groups. A bimodal distribution was drawn for particle mass and water-soluble extract. WSOC and organic hydrogen were distributed between fine particles with MMADs of 0.37 and 0.34 μm and coarse particles with MMADs of 11.83 and 11.35 μm, indicating a mixture of primary large organic aerosol and condensed organic species in the accumulation mode. The NMR spectra for larger particles (δp > 3.0 μm) demonstrated a strong oxygenated saturated aliphatic content and the presence of fructose, sucrose, glucose, acetate, formate and succinate. These compounds have been previously found in pollen, soil and sea spray particles. For smaller particles (δp < 1.5 μm), the NMR spectra were dominated by saturated and unsaturated aliphatic protons. Organic species associated with biomass burning (i.e., levoglucosan) and urban traffic emissions (phthalate and terephthalate) were tentatively determined. Furthermore, resonances attributed to ammonium and amines were recognized, suggesting the presence of ammonium/aminium nitrate and sulfate secondary aerosol. The δ13C corroborated the local anthropogenic origin of fine and ultrafine organic aerosol. The values of the H–C–C=O / Σ (H–C–) and H–C–O / Σ (H–C–) ratios for the different particle sizes also confirmed the mixed contributions of urban and biomass burning emissions for fine and ultra-fine aerosol. The observed distribution of functional groups allowed for the distinct separation of biomass burning and pollen particles, in agreement with previous studies. More than 95 % of WSOC was associated with the five types of non-exchangeable organic hydrogen shown for the largest and smallest particle sizes. Overall, we characterized the WSOC in the southern Mississippi Valley, a region influenced by local anthropogenic sources, intense episodes of pollen, and regional secondary sources of anthropogenic and marine origin. We showed that NMR provides qualitative and, in conjunction with thermal optical reflectance and isotopic analysis, quantitative information on the compositional features of WSOC. Finally, the relative distribution of non-exchangeable organic hydrogen functional groups appeared to be distinctively unique for pollen particles and different than that previously observed for biomass burning and biogenic secondary organic aerosol, indicating that the origin of WSOC may be determined.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank R. Helm for editing the manuscript. The opinions expressed here do not necessarily represent those of the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

- Aceves M, Grimalt JO. Seasonally dependent size distributions of aliphatic and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban aerosols from densely populated areas. Environ Sci Technol. 1993;27:2896–2908. [Google Scholar]

- Adler G, Flores JM, Abo Riziq A, Borrmann S, Rudich Y. Chemical, physical, and optical evolution of biomass burning aerosols: a case study. Atmos Chem Phys. 2011;11:1491–1503. doi: 10.5194/acp-11-1491-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S, Aggarwal SG, Okuzawa K, Kawamura K. Size distributions of dicarboxylic acids, ketoacids, α-dicarbonyls, sugars, WSOC, OC, EC and inorganic ions in atmospheric particles over Northern Japan: implication for long-range transport of Siberian biomass burning and East Asian polluted aerosols. Atmos Chem Phys. 2010;10:5839–5858. doi: 10.5194/acp-10-5839-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal SG, Kawamura K, Umarji GS, Tachibana E, Patil RS, Gupta PK. Organic and inorganic markers and stable C-, N-isotopic compositions of tropical coastal aerosols from megacity Mumbai: sources of organic aerosols and atmospheric processing. Atmos Chem Phys. 2013;13:4667–4680. doi: 10.5194/acp-13-4667-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alier M, van Drooge BL, Dall’Osto M, Querol X, Grimalt JO, Tauler R. Source apportionment of submicron organic aerosol at an urban background and a road site in Barcelona (Spain) during SAPUSS. Atmos Chem Phys. 2013;13:10353–10371. doi: 10.5194/acp-13-10353-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantine DC, Macko SA, Turekian VC. Variability of stable carbon isotopic composition in individual fatty acids from combustion of C4 and C3 plants: implications for biomass burning. Chem Geol. 1998;152:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoszeck M, Polak J, Sulkowski WW. NMR study of the humification process during sewage sludge treatment. Chemosphere. 2008;73:1465–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugni TS, Ireland CM. Marine-derived fungi: a chemically and biologically diverse group of microorganisms. Nat Prod Rep. 2004;21:143–163. doi: 10.1039/b301926h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachier H, Buat-Menard P, Fontugne M, Chesselet R. Long-range transport of continentally-derived particulate carbon in the marine atmosphere: evidence from stable carbon isotopic studies. Tellus B. 1986;38:161–177. [Google Scholar]

- Cappa CD, Lovejoy ER, Ravishankara AR. Evidence for Liquid-Like and Nonideal Behavior of a Mixture of Organic Aerosol Components, P. Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18687–18691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802144105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli F, Facchini M, Decesari S, Mircea M, Emblico L, Fuzzi S, Ceburnis D, Yoon Y, O’Dowd C, Putaud J, Dell’Acqua A. Advances in characterization of size-resolved organic matter in marine aerosol over the North Atlantic. J Geo-phys Res-Atmos. 2004;109:D24215. doi: 10.1029/2004JD0051377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chalbot M-C, McElroy B, Kavouras IG. Sources, trends and regional impacts of fine particulate matter in southern Mississippi valley: significance of emissions from sources in the Gulf of Mexico coast. Atmos Chem Phys. 2013a;13:3721–3732. doi: 10.5194/acp-13-3721-2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chalbot MC, Nikolich G, Etyemezian V, Dubois DW, King J, Shafer D, Gamboa Da Costa G, Hinton JF, Kavouras IG. Soil humic-like organic compounds in prescribed fire emissions using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Environ Pollut. 2013b;181:167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalbot MC, Gamboa da Costa G, Kavouras IG. NMR analysis of the water soluble fraction of airborne pollen particles. Appl Magn Reson. 2013c;44:1347–1358. [Google Scholar]

- Chesselet R, Fontugne M, Buat-Menard P, Ezat U, Lambert CE. The origin of particulate organic carbon in the marine atmosphere as indicated by its stable carbon isotopic composition. Geophys Res Lett. 1981;8:345–348. [Google Scholar]

- Cho AK, Sioutas C, Miguel AH, Kumagai Y, Schmitz DA, Singh M, Eiguren-Fernandez A, Froines JR. Redox activity of airborne particulate matter at different sites in the Los Angeles Basin. Environ Res. 2005;99:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland MJ, Ziemba LD, Griffin RJ, Dibb JE, Anderson CH, Lefer B, Rappenglueck B. Characterization of urban aerosol using aerosol mass spectrometry and proton nuclear magnetic resonances. Atmos Environ. 2012;54:511–518. [Google Scholar]

- Collister JW, Rieley G, Stern B, Eglinton G, Fry B. Compound-specific delta-C-13 analyses of leaf lipids from plants with differing carbon-dioxide metabolisms. Org Geochem. 1994;21:619–627. [Google Scholar]

- Coplen TB. Guidelines and recommended terms for expression of stable-isotope-ratio and gas-ratio measurement results. Rapid Commun Mass Sp. 2011;25:2538–2560. doi: 10.1002/rcm.5129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decesari S, Facchini M, Fuzzi S, Tagliavini E. Characterization of water-soluble organic compounds in atmospheric aerosol: A new approach. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2000;105:1481–1489. [Google Scholar]

- Decesari S, Facchini M, Matta E, Lettini F, Mircea M, Fuzzi S, Tagliavini E, Putaud J. Chemical features and seasonal variation of fine aerosol water-soluble organic compounds in the Po valley, Italy. Atmos Environ. 2001;35:3691–3699. [Google Scholar]

- Decesari S, Fuzzi S, Facchini MC, Mircea M, Emblico L, Cavalli F, Maenhaut W, Chi X, Schkolnik G, Falkovich A, Rudich Y, Claeys M, Pashynska V, Vas G, Kourtchev I, Vermeylen R, Hoffer A, Andreae MO, Tagliavini E, Moretti F, Artaxo P. Characterization of the organic composition of aerosols from Rondônia, Brazil, during the LBA-SMOCC 2002 experiment and its representation through model compounds. Atmos Chem Phys. 2006;6:375–402. doi: 10.5194/acp-6-375-2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Decesari S, Mircea M, Cavalli F, Fuzzi S, Moretti F, Tagliavini E, Facchini MC. Source attribution of water-soluble organic aerosol by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:2479–2484. doi: 10.1021/es061711l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decesari S, Finessi E, Rinaldi M, Paglione M, Fuzzi S, Stephanou EG, Tziaras T, Spyros A, Ceburnis D, O’Dowd C, Dall’Ostro M, Harrison RM, Allan J, Coe H, Facchini MC. Primary and secondary marine organic aerosols over the North Atlantic Ocean during the MAP experiment. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2011;116:D22210. doi: 10.1029/2011JD016204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar M, Portnoy J, Barnes C. Oak pollen season in the Midwestern US. J Allergy Clin Immun. 2010;125:AB15. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(10)00024-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl K, Quick C, Matthis-Maser S, Mitra SK, Jaenicke R. The ice nucleating ability of pollen Part I: Laboratory studies in deposition and condensation freezing modes. Atmos Res. 2001;58:75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte RMBO, Santos EBH, Pio CA, Duarte AC. Comparison of structural features of water-soluble organic matter from atmospheric aerosols with those of aquatic humic substances. Atmos Environ. 2007;41:8100–8113. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte RMBO, Silva AMS, Duarte AC. Two-dimensional NMR studies of water-soluble organic matter in atmospheric aerosols. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:8224–8230. doi: 10.1021/es801298s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finessi E, Decesari S, Paglione M, Giulianelli L, Carbone C, Gilardoni S, Fuzzi S, Saarikoski S, Raatikainen T, Hillamo R, Allan J, Mentel ThF, Tiitta P, Laaksonen A, Petäjä T, Kulmala M, Worsnop DR, Facchini MC. Determination of the biogenic secondary organic aerosol fraction in the boreal forest by NMR spectroscopy. Atmos Chem Phys. 2012;12:941–959. doi: 10.5194/acp-12-941-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fontugne MR, Duplessy JC. Organic-Carbon isotopic fractionation by marine plankton in the temperature-range −1 to 31 degres C. Oceanol Acta. 1981;4:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fu P, Kawamura K, Kobayashi M, Simoneit BRT. Seasonal variations of sugars in atmospheric particulate matter from gosan, jeju island: Significant contributions of airborne pollen and asian dust in spring. Atmos Environ. 2012;55:234–239. [Google Scholar]

- Fuzzi S, Decesari S, Facchini MC, Matta E, Mircea M, Tagliavini E. A simplified model of the water soluble organic component of atmospheric aerosols. Geophys Res Lett. 2001;28:4079–4082. [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Wexler AS, Clegg SL. Atmospheric Amines – Part 1, A review. Atmos Environ. 2011;45:524–546. [Google Scholar]

- Ghan SJ, Schwartz SE. Aerosol properties and processes–A path from field and laboratory measurements to global climate models, B. Am Meteorol Soc. 2007;88:1059–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AH, Galbally IE. Known and unexplored organic constituents in the earth’s atmosphere. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:1514–1521. doi: 10.1021/es072476p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham B, Mayol-Bracero O, Guyon P, Roberts GC, Decesari S, Facchini MC, Artaxo P, Maenhaut W, Köll P, Andreae MO. Water-soluble organic compounds in biomass burning aerosols over Amazonia 1. Characterization by NMR and GC-MS. J Geophys Res. 2002;107:8047. doi: 10.1029/2001JD000336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasheminassab S, Daher N, Schauer JJ, Sioutas C. Source apportionment and organic compound characterization of ambient ultrafine particulate matter (PM) in the Los Angeles Basin. Atmos Environ. 2013;79:529–539. [Google Scholar]

- Ho KF, Lee SC, Cao JJ, Li YS, Chow JC, Watson JG, Fung K. Variability of organic and elemental carbon, water soluble organic carbon, and isotopes in Hong Kong. Atmos Chem Phys. 2006;6:4569–4576. doi: 10.5194/acp-6-4569-2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kavouras IG, Koutrakis P. Use of polyurethane foam as the impaction substrate/collection medium in conventional inertial impactors. Aerosol Sci Tech. 2001;34:46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kavouras IG, Stephanou EG. Particle size distribution of organic primary and secondary aerosol constituents in urban, background marine, and forest atmosphere. J Geophys Res. 2002;107:4069. doi: 10.1029/2000JD000278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kavouras IG, Etyemezian V, DuBois DW, Xu J, Pitchford M. Source reconciliation of atmospheric dust causing visibility impairment in Class I areas of the western United States. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2009;114:D02308. doi: 10.1029/2008JD009923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura K, Kaplan IR. Motor exhaust emissions as a primary source for dicarboxylic acids in Los Angeles ambient air. Environ Sci Technol. 1987;21:105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura K, Yasui O. Diurnal changes in the distribution of dicarboxylic acids, ketocarboxylic acids and dicarbonyls in the urban Tokyo atmosphere. Atmos Environ. 2005;39:1945–1960. [Google Scholar]

- Maksymiuk CS, Gayahtri C, Gil RR, Donahue NM. Secondary organic aerosol formation from multiphase oxidation of limonene by ozone: Mechanistic constraints via two-dimensional heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2009;11:7810–7818. doi: 10.1039/b820005j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Nagao I, Tanaka H, Miyaji H, Iida T, Ikebe Y. Seasonal characteristics of organic and inorganic species and their size distributions in atmospheric aerosols over the Northwest Pacific Ocean. Atmos Environ. 1998;32:1931–1946. [Google Scholar]

- Matta E, Facchini MC, Decesari S, Mircea M, Cavalli F, Fuzzi S, Putaud J-P, Dell’Acqua A. Mass closure on the chemical species in size-segregated atmospheric aerosol collected in an urban area of the Po Valley, Italy. Atmos Chem Phys. 2003;3:623–637. doi: 10.5194/acp-3-623-2003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros PM, Conte MH, Weber JC, Simoneit BRT. Sugars as source indicators of biogenic organic carbon in aerosols collected above the Howland Experimental Forest, Maine. Atmos Environ. 2006;40:1694–1705. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki Y, Kondo Y, Shiraiwa M, Takegawa N, Miyakawa T, Han S, Kita K, Hu M, Denq ZQ, Zhao Y, Sugimoto N, Blake DR, Weber RJ. Chemical characterization of water-soluble organic carbon aerosols at a rural site in the Pearl River Delta, China, in the summer of 2006. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2009;114:D14208. doi: 10.1029/2009JD011736. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller C, Iinuma Y, Karstensen J, van Pinxteren D, Lehmann S, Gnauk T, Herrmann H. Seasonal variation of aliphatic amines in marine sub-micrometer particles at the Cape Verde islands. Atmos Chem Phys. 2009;9:9587–9597. doi: 10.5194/acp-9-9587-2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson ST. A simple, practical methodology for routine VS-MOW/SLAP normalization of water samples analyzed by continuous flow methods. Rapid Commun Mass Sp. 2000;14:1044–1046. doi: 10.1002/1097-0231(20000630)14:12<1044::AID-RCM987>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrogrande MC, Bacco D, Chiereghin S. GC/MS analysis of water-soluble organics in atmospheric aerosol: optimization of a solvent extraction procedure for simultaneous analysis of carboxylic acids and sugars. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2013;405:1095–1104. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6592-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pöschl U. Atmospheric aerosols: Composition, transformation, climate and health effects. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2005;44:7520–7540. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putaud JP, Raes F, Van Dingenen R, Bruggermann E, Facchini MC, Decesari S, Fuzzi S, Gehrig R, Huglin C, Laj P, Lorbeer G, Maenhaut W, Mihalopoulos N, Muller K, Querol X, Rodriguez S, Schneider J, Spindler G, ten Brink H, Torseth K, Wiedensohler A. A European aerosol phenomenology-2: Chemical characteristics of particulate matter at kerbside, urban, rural and background sites in Europe. Atmos Environ. 2004;38:2579–2595. [Google Scholar]

- Reid JP, Dennis-Smither BJ, Kwamena NOA, Miles REH, Hanford KL, Homer CJ. The morphology of aerosol particles consisting of hydrophobic and hydrophilic phases: hydrocarbons, alcohols and fatty acids as the hydrophobic component. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13:15559–15572. doi: 10.1039/c1cp21510h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rincon AG, Guzman MI, Hoffmann MR, Colussi AJ. Optical absorptivity versus molecular composition of model organic aerosol matter. J Phys Chem. 2009;113:10512–10520. doi: 10.1021/jp904644n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sannigrahi P, Sullivan A, Weber R, Ingall E. Characterization of water-soluble organic carbon in urban atmospheric aerosols using solid-state C-13 NMR spectroscopy. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40:666–672. doi: 10.1021/es051150i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savorani F, Tomasi G, Engelsen SB. icoshift: A versatile tool for the rapid alignment of 1D NMR spectra. J Magn Res. 2010;202:109–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schade GW, Crutzen PJ. Emission of aliphatic amines from animal husbandry and their reactions: potential source of N2O and HCN. J Atmos Chem. 1995;22:319–346. [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger RB, Kunzli N, Hidy GM, Gotschi T, Jerrett M. The health relevance of ambient particulate matter characteristics: Coherence of toxicological and epidemiological inferences. Inhal Toxicol. 2006;18:95–125. doi: 10.1080/08958370500306016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson A, Lam B, Diamond ML, Donaldson DJ, Lefebvre BA, Moser AQ, Williams AJ, Larin NI, Kvasha MP. Assessing the organic composition of urban surface films using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Chemosphere. 2006;63:142–152. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisler JF. In: Aerosol mass budget and spatial distribution, in Spatial and Seasonal Pattern and Temporal Variability of Haze and its Constitutents in the United States, Report III. Malm W, editor. Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Co; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sloane CS, Watson J, Chow J, Pritchett L, Richards LW. Size-segregated fine particle measurements by chemical-species and their impact on visibility impairment in Denver. Atmos Environ A-Gen. 1991;25:1013–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Song J, He L, Peng P, Zhao J, Ma S. Chemical and isotopic composition of humic-like substances (HULIS) in ambient aerosols in Guangzhou, South China. Aerosol Sci Tech. 2012;46:533–546. [Google Scholar]

- Subbalakshmi Y, Patti AF, Lee GSH, Hooper MA. Structural characterization of macromolecular organic material in air particulate matter using py-GC-MS and solid state C-13-NMR. J Environ Monitor. 2000;2:561–565. doi: 10.1039/b005596o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Kawakami M, Akasaka K. H-1 NMR application for characterizing water-soluble organic compounds in urban atmospheric particles. Environ Sci Technol. 2001;35:2656–2664. doi: 10.1021/es001861a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliavini E, Moretti F, Decesari S, Facchini MC, Fuzzi S, Maenhaut W. Functional group analysis by H NMR/chemical derivatization for the characterization of organic aerosol from the SMOCC field campaign. Atmos Chem Phys. 2006;6:1003–1019. doi: 10.5194/acp-6-1003-2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Sasaki K, Nakamura S, Miki-Hirosige H, Nitta H. Aerodynamic size distribution of particles emitted from the flowers of allergologically important plants. Grana. 1995;34:45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Timonen H, Saarikoski S, Aurela M, Saarnio K, Hillamo R. Water soluble organic carbon in urban aerosols: concentrations, size distributions and contributions to particulate matter. Boreal Environ Res. 2008;13:335–346. [Google Scholar]

- VandenBoer TC, Petroff A, Markovic MZ, Murphy JG. Size distribution of alkyl amines in continental particulate matter and their online detection in the gas and particle phase. Atmos Chem Phys. 2011;11:4319–4332. doi: 10.5194/acp-11-4319-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vaeck L, Van Cauwenberghe KA. Characteristic parameters of particle size distributions of primary organic constituents of ambient aerosols. Environ Sci Technol. 1985;19:707–716. doi: 10.1021/es00138a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widory D, Roy S, Le Moullec Y, Goupil G, Cocherie A, Geuerrot C. The origins of atmospheric particles in Paris: a view through carbon and lead isotopes. Atmos Environ. 2004;38:953–961. [Google Scholar]

- Wishart DS, Knox C, Guo AC, Eisner R, Young N, Gautam B, Hau DD, Psychogios N, Dong E, Bouatra S, Mandal R, Sinelnikov I, Xia J, Jia L, Cruz JA, Lim E, Sobsey CA, Shrivastava S, Huang P, Liu P, Fang L, Peng J, Fradette R, Cheng D, Tzur D, Clements M, Lewis A, De Souza A, Zuniga A, Dawe M, Xiong Y, Clive D, Greiner R, Nazyrova A, Shaykhutdinov R, Li L, Vogel HJ, Forsythe I. HMDB: a knowledgebase for the human metabolome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D603-10. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak AS, Shelley RU, Sleighter RL, Abdulla HAN, Morton PL, Landing WM, Hatcher PG. Relationships among aerosol water soluble organic matter, iron and aluminum in European, North African, and marine air masses from the 2010 US GEOTRACES cruise. Mar Chem. 2013;154:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto N, Bibby K, Qian J, Hospodsky D, Rismani-Yazdi H, Nazaroff WW, Peccia J. Particle-size distribution and seasonal diversity of allergenic and pathogenic fungi in outdoor air. ISME J. 2012;6:1801–1811. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Obritz D, Zielinska B, Gertler A. Particulate emissions from different types of biomass burning. Atmos Environ. 2013;72:27–35. [Google Scholar]