Significance

Formation of the gas-exchange region of the lung occurs largely postnatally through a process called alveologenesis. Alveolar abnormalities are a hallmark of neonatal and adult chronic lung diseases. Here we report that disruption of Notch signaling in mice, particularly by Notch2, results in abnormal enlargement of the alveolar spaces reminiscent of that seen in chronic lung diseases. We provide evidence that Notch is crucial to mediate cross-talk between different cell layers, including signals such as PDGF for formation of the alveoli and maintenance of the integrity of the conducting airways.

Keywords: Notch, alveolar myofibroblast, alveologenesis, bronchial smooth muscle, epithelial–mesenchymal interactions

Abstract

Abnormal enlargement of the alveolar spaces is a hallmark of conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Notch signaling is crucial for differentiation and regeneration and repair of the airway epithelium. However, how Notch influences the alveolar compartment and integrates this process with airway development remains little understood. Here we report a prominent role of Notch signaling in the epithelial–mesenchymal interactions that lead to alveolar formation in the developing lung. We found that alveolar type II cells are major sites of Notch2 activation and show by Notch2-specific epithelial deletion (Notch2cNull) a unique contribution of this receptor to alveologenesis. Epithelial Notch2 was required for type II cell induction of the PDGF-A ligand and subsequent paracrine activation of PDGF receptor-α signaling in alveolar myofibroblast progenitors. Moreover, Notch2 was crucial in maintaining the integrity of the epithelial and smooth muscle layers of the distal conducting airways. Our data suggest that epithelial Notch signaling regulates multiple aspects of postnatal development in the distal lung and may represent a potential target for intervention in pulmonary diseases.

In the mature lung, proper gas exchange is achieved by a vast network of alveolar structures comprised of epithelial type I and type II cells closely apposed to capillaries and a thin layer of mesenchymal lipofibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Formation of this compartment initiates prenatally with the establishment of a distal program of differentiation in lung epithelial progenitors and later with formation of primitive saccules. The mature murine alveoli, however, are generated postnatally through a dramatic remodeling of the primitive saccules known as alveologenesis (1). Abnormal alveologenesis has devastating effects and is present in human conditions such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia and prematurity. The mechanisms involved in alveolar formation include expansion of epithelial cells lining the primitive saccules and generation of secondary septa where interstitial alveolar myofibroblasts (AMYFs) deposit elastin (2). AMYFs are derived from a population of mesenchymal progenitors known to require platelet derived growth factor receptor-α (PDGFR-α) signaling to develop (3).

Notch signaling is essential for lung development. Notch genes encode single-transmembrane receptors that mediate communication between neighboring cells crucial for cell fate decisions during organ development (4). In mammals, four Notch receptors (Notch1 to Notch4) and five ligands (Jag1, Jag2, Dll1, Dll3, and Dll4) mediate these signaling events, largely through Rbpj (or CSL) transcriptional effector. O-fucosyltransferase 1 (Pofut1), an additional component of this pathway, conjugates O-fucose to EGF repeats of Notch receptors, allowing efficient Notch–ligand interactions (5).

In the embryonic lung Notch regulates the balance of ciliated, secretory, and neuroendocrine cells in the airway epithelium (6, 7). Postnatally, epithelial Notch signaling prevents airway Club (Scgb1a1 positive/Clara) cells from differentiating into goblet cells and is critical for airway regeneration after injury (8–10). It is less clear, however, how Notch signaling influences the alveolar compartment. Analysis of Rbpj or Pofut1 null mutants at late gestation shows that primitive saccules do not require Notch to develop. By contrast, Notch gain of function does interfere with differentiation of the developing distal lung compartment, from which alveoli will form postnatally (11). However, the Notch-overexpressing mutants die at birth, before the initiation of alveologenesis, thus limiting conclusions on the role of Notch in this process. Interestingly, analysis of Notch-deficient mice that survive postnatally, such as conditional Jag1 or glycosyltransferase Lunatic fringe (Lfng) mutants, points to a role of Notch in alveologenesis (12). Nevertheless, these mutants shed little light on Notch-mediated events in alveolar development. Deletion of Jag1 in lung epithelium had no effect on differentiation and maturation of alveolar epithelial cells (13). Deficiency in Lfng-mediated Notch signaling impaired myofibroblast differentiation, but it was unclear whether Notch was normally activated in these cells. Moreover, mice overexpressing Lfng in distal lung epithelium, including type II cells, show no lung abnormalities and survive to adulthood (14).

To better understand how Notch influences alveolar formation we investigated the impact of selective or pan-Notch receptor loss of function in the murine lung. Here we show that during neonatal life Notch2 is activated in type II cells to induce PDGF-A expression, triggering paracrine activation of PDGFR-α signaling in AMYF progenitors ultimately required for alveologenesis. We found a selectively dominant contribution of Notch2, compared with Notch1, in this process. Disruption of Notch signaling decreased PDGF-A expression, whereas overexpression of activated Notch2 rescued this negative effect of Notch inhibition. Notch signaling was also required for maintaining the integrity of the epithelial and bronchial smooth muscle (SM) layers of the distal airways. Thus, epithelial Notch signaling integrates postnatal morphogenesis of the distal bronchiole and alveoli via epithelial–mesenchymal interactions.

Results

Epithelial Pan-Notch Signaling Inactivation Disrupts Alveolar Development.

To investigate Notch signaling in alveologenesis we examined mice of the Shh-Cre;Pofut1 flox/flox line, which do not activate Notch in the lung epithelium but have some pups surviving up to 2–3 wk postnatally (7) (Fig. S1 A and B). Histological analysis revealed that whereas at embryonic day (E) 18.5 Pofut1cNull lungs were indistinguishable from controls (Fig. 1 A and B), at postnatal day (P) 3 mutant lungs failed to initiate alveolization, secondary septa were less frequent, and distal airspaces were enlarged compared with controls (Fig. 1 C and D). By P21, when alveologenesis was mostly completed in controls, Pofut1cNull lungs showed a major deficit in alveolar formation with an emphysema-like enlargement of distal airspaces [Fig. 1 E–G; mean alveolar cord length (mean ± SEM): control, 31 ± 0.6 μm and Pofut1cNull, 61 ± 2.9 μm].

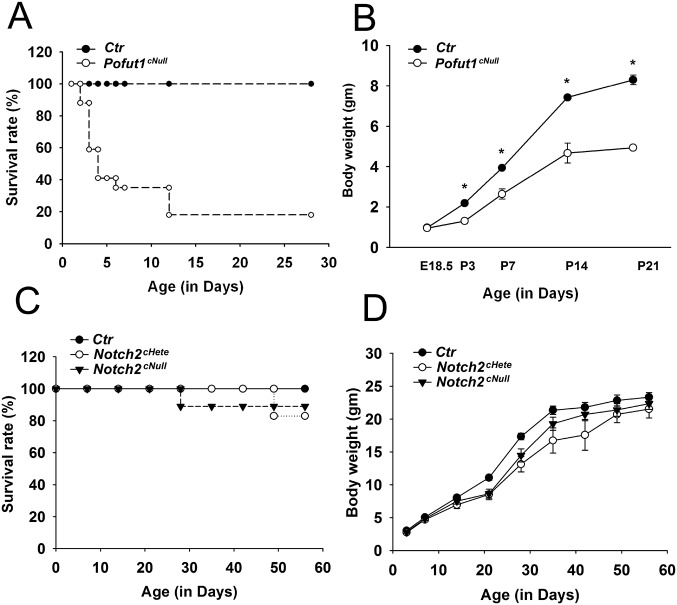

Fig. S1.

Postnatal growth and mortality in Notch mutant mice. (A and B) Pofut1cNull: Nearly 80% pups died within 2 wk of life. Failure to thrive was noted in Pofut1cNull mice since P3 and progressed thereafter (n = 4–34). (C and D) Notch2 mutants: Survival rate (C) and body weight (D) were compatible among wild-type, Notch2cNull, and Notch1cHetel;Notch2cNull mice. *P < 0.05.

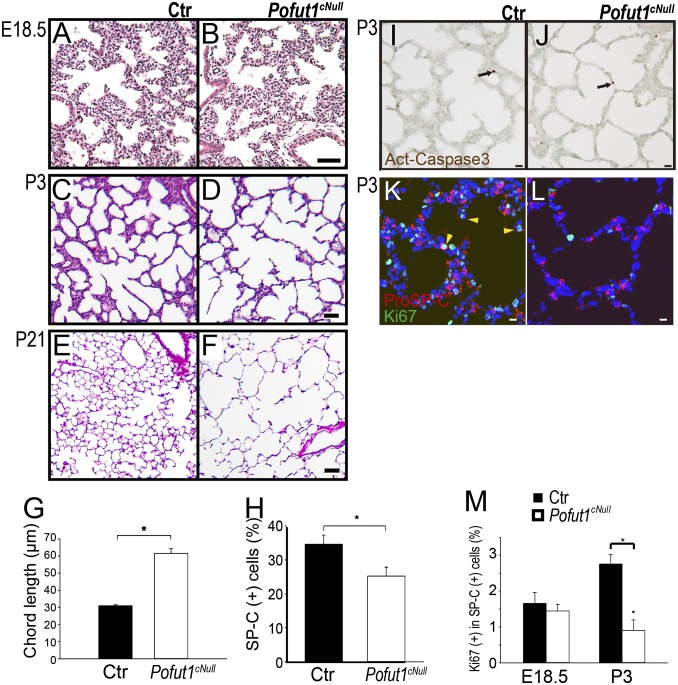

Fig. 1.

Emphysema-like alveolar phenotype in Pofut1cNull mice. H&E staining of controls (A, C, and E) and Pofut1cNull (B, D, and F) at different ages. (A and B) No difference at E18.5. (C and D) Marked decrease in the secondary septa (arrowhead) in Pofut1cNull mice compared with controls at P3. (E and F) At P21, Pofut1cNull showed enlarged and simplified alveoli. (G) Significantly increased chord length in Pofut1cNull mice at P21. (H) Pro-SPC–positive type II cells were significantly reduced at P21 in Pofut1cNull lungs. The cell numbers were counted on 10 fields at 20× magnification of three mice for each genotype. Cleaved caspase-3 showed no difference between wild-type (I) and Pofut1cNull lungs (J) at P3. Immunohistochemistry of Ki67 and SPC in control (K) and Pofut1cNull lungs (L) revealed proliferation index significantly decreased in type II cells at P3 (M) (n > 4 in each group; *P < 0.05). (Scale bars, 50 μm in A–F and 10 μm in I–L.)

Immunohistochemistry for prosurfactant protein C (pro-SPC) and morphometric analysis at P3 showed no difference in the number of type II cells between control and mutants; however, by P21 this number was significantly decreased in Pofut1cNull lungs (Fig. 1H and Fig. S2 A and B). T1-α (or podoplanin), which marks type I pneumocytes, was similarly expressed in control and Pofut1cNull lungs and outlined the enlarged distal airspaces of mutant lungs (Fig. S2 C–E). Activated Caspase3 suggested no difference in cell apoptosis between control and Pofut1cNull lungs (Fig. 1 I and J). However, we found decreased Ki-67 labeling in type II cells of Pofut1cNull mice (5.6% ± 1.3) compared with control (27.4% ± 1.8) at P3 (Fig. 1 K–M). Decreased proliferation postnatally could at least in part have contributed to the distal abnormalities of Notch-mutant lungs. Thus, although dispensable for cell type I/type II cell fate decisions, Notch signaling could be necessary to control the number of type II cells in the postnatal lung (7).

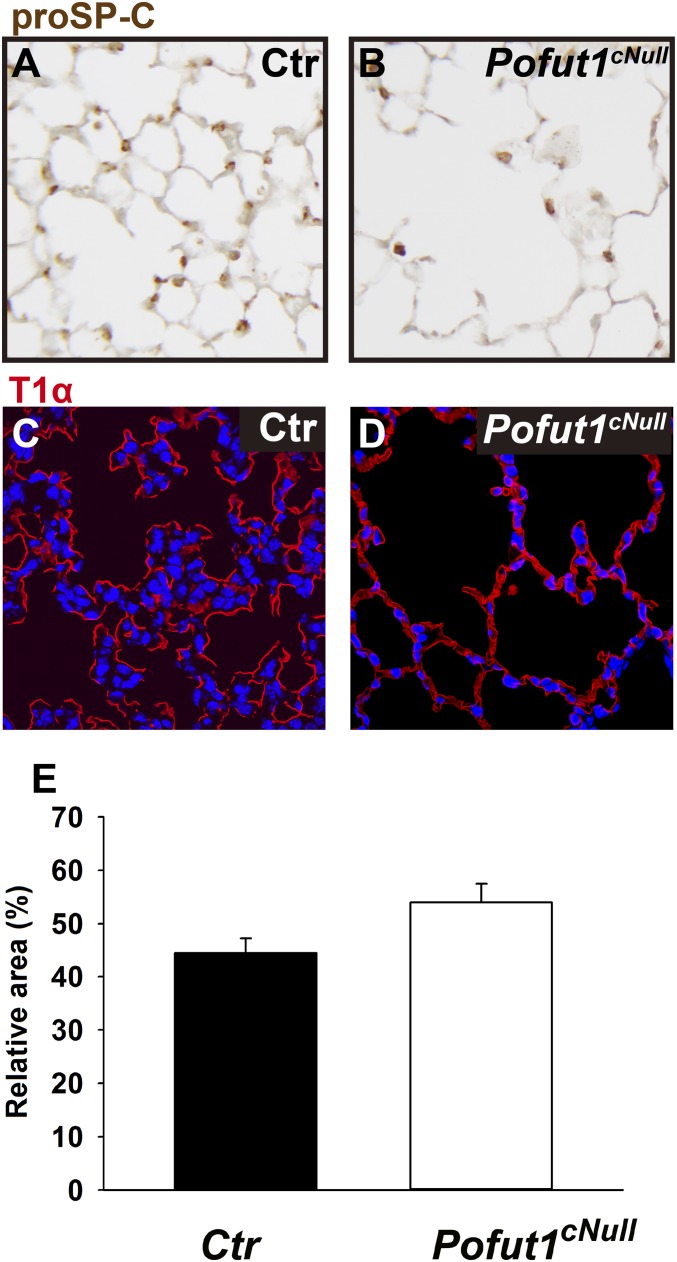

Fig. S2.

Distal lung differentiation in Pofut1cNull mice. Immunohistochemistry of (A and B) SPC, which labeled type II cells and of (C and D) T1-α (T1a), which labeled type I cells, showed a similar pattern of staining in control and Pofut1cNull lungs. (E) Quantification of type I cells presented as T1a staining area.

Notch2 Is Activated in Type II Cells During Alveologenesis.

Given that in pan-Notch signaling inactivation only a limited number of Pofut1cNull mice reached adulthood, we tested whether a Notch receptor-specific approach would allow better survival and provide additional insights into the role of Notch receptors in alveolar formation.

We limited our analysis to Notch1 and Notch2 because Notch3 null mice show no alveolar abnormalities (15) and Notch4 expression is restricted to the endothelium (16). First, we identified sites of Notch signaling activation during alveolar formation, by indirect immunofluorescence (IF) using antibodies that label selectively the Notch1 or 2 intracellular domains (N1-ICD and N2-ICD). Analysis of the distal lung at the onset of alveologenesis (P3) showed nuclear N1-ICD largely confined to endothelial cells with only weak epithelial signals (Fig. 2A and ref. 6). By contrast, N2-ICD strongly labeled type II cells (Fig. 2B).

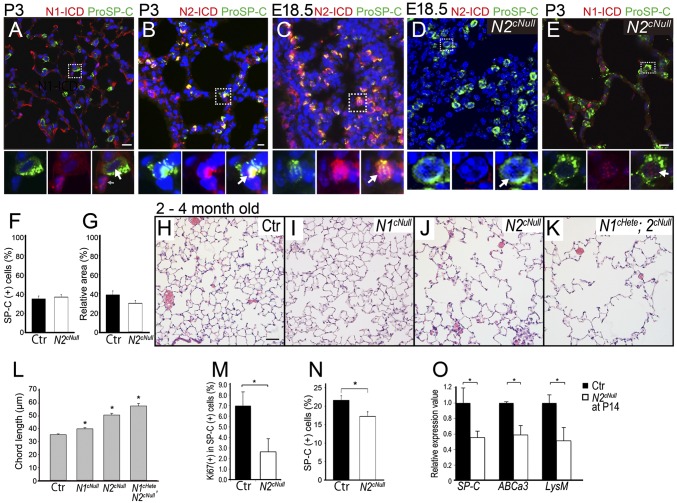

Fig. 2.

Notch2 activation in type II cells and requirement for type II cell proliferation and maturation. (A) Coimmunostaining of N1-ICD and pro-SPC at P3 showed that type II cells (white arrow) were not the main Notch1-active population (gray arrow). (B–D) N2-ICD detected in pro-SPC–positive type II cells (white arrows) at P3 (B) and E18.5 (C). N2-ICD antibody validated by lack of staining in Notch2cNull lungs (D). At P3, spotted N1-ICD signals in the nuclei of type II cells (white arrow) were increased in Notch2cNull (E) in compare with wild type (A). Quantification of type II (F) and type I (G) cells showed no difference between Notch2cNull and control lungs at P3. H&E staining of control (H), Notch1cNull (I), Notch2cNull (J), and Notch1cHete; 2cNull (K) mutant mice at 2–4 mo old. Emphysema-like phenotype in Notch2cNull and Notch1cHete;2cNull mutant lungs but not in Notch1cNull, and more severe in Notch1cHete;2cNull. (L) Significantly increased chord length in Notch receptor mutants, especially in Notch2cNull and Notch1cHete;2cNull at 2–4 mo old. (M) Proliferation index determined by Ki67 in pro-SPC–positive type II cells in control or Notch2cNull lungs at P3. (N) Type II cell number significantly decreased in adult Notch2cNull lungs at 4 mo old. (O) Significant reductions of expression of the type II cell marker genes SPC, ABCa, and LysM in Notch2cNull by quantitative RT-PCR of isolated the type II cells at P14. (Scale bars, 10 μm in A–E and 50 μm in H–K.)

We then investigated whether Notch2 is already active prenatally as primitive saccules form. N2-ICD signals were present at E18.5 in cells coexpressing pro-SPC (Fig. 2C), suggesting that Notch2 is activated already at the saccular stage concomitantly with the differentiation of type II cells. Thus, Notch2 is the predominant receptor activated in type II cells of primitive saccules, with a modest contribution of Notch1.

Notch2cNull but Not Notch1cNull Lungs Show Morphological and Functional Features of Emphysema-Like Phenotype.

To interrogate the function of Notch receptors individually in the developing lung, we inactivated Notch1 or Notch2 conditionally in the lung epithelium using the Shh-Cre mice, as we did for Pofut1 mutants (henceforth referred to as Notch1cNull and Notch2cNull mice).

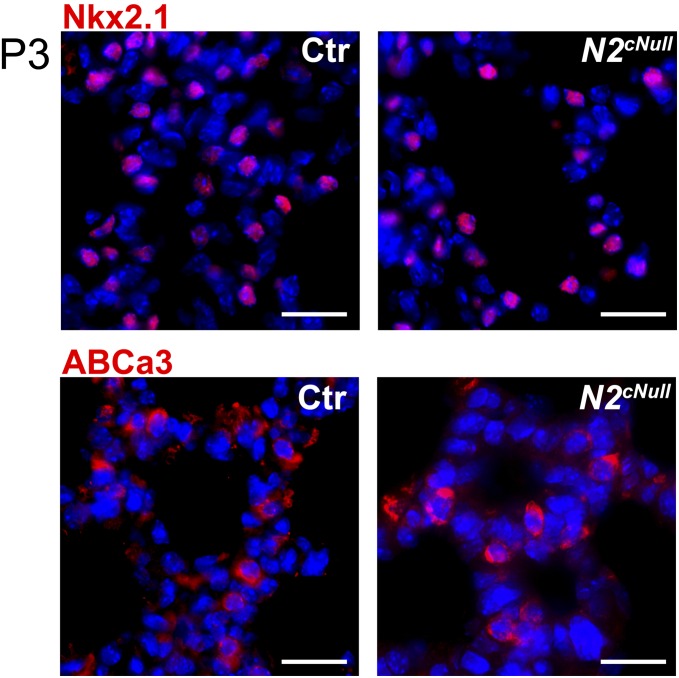

Notch1cNull and Notch2cNull pups were viable and reached adulthood (Fig. S1 C and D). Morphology and marker analyses of E18.5 and neonatal (P3) lungs was unremarkable in these mutants, including normal sacculation and differentiation of type I and type II cells, as confirmed by T1-α, Pro-SPC, Nkx2.1, and ABCa3 staining (Fig. 2 D and E and Fig. S3). Quantitative analysis showed no significant difference in the number of type II cells in Notch2cNull compared with controls (Fig. 2 F and G), confirming that Notch signaling is not required for type I versus type II cell fate decision in the lung (7).

Fig. S3.

Normal type II cells differentiation of Notch2 mutant lungs. Staining for two markers of type II cells, such as Nkx2.1 and ABCa3, showed no difference between control and Notch2cNull lungs at P3. (Scale bars, 50 μm.)

Adult lungs from Notch2cNull, however, were markedly different from those of Notch1cNull. Only Notch2cNull exhibited the emphysema-like enlargement of distal airspaces seen in Pofut1cNull (Fig. 2 H–J and L). As in Pofut1cNull lungs (Fig. 1M), Ki-67 labeling in type II cells of Notch2cNull lungs was significantly reduced (Fig. 2M). In addition, the number of type II cells was significantly decreased in adult Notch2cNull lungs (Fig. 2N), consistent with the findings in Pofut1cNull lung (Fig. 1H). We then isolated type II cells from control and Notch2cNull mice at P14 (late stage of alveologenesis) using FACS; PCR analysis showed decreased expression of SP-C, ABCa3, and LysM genes in mutants (17) (Fig. 2O). We concluded that, although not required for sacculation, Notch2 activity is essential for proliferation and maturation of type II cells when definitive alveoli are forming.

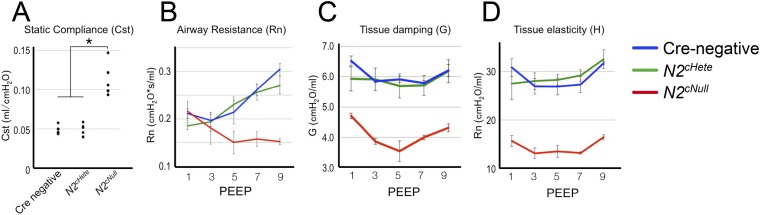

To evaluate the impact of Notch2 deficiency in the function of these lungs we assessed key physiologic parameters in adult mutants and age/sex-matched controls by FlexiVent analysis. We found a twofold increase in static lung compliance (Cst) in Notch2cNull homozygous compared with Notch2cHet and control (Cre-negative) littermates (Fig. S4A). We also detected a decrease in airway resistance (Rn) to high-pressure airflow (positive end expiratory pressure, PEEP) and a decrease in tissue elasticity and tissue damping (G) in homozygous Notch2cNull (Fig. S4 B–D). These findings are consistent with the functional abnormalities associated with an emphysema-like enlargement of distal airspaces. Interestingly, N1-ICD and pro-SPC double IF in Notch2cNull lungs showed N1-ICD nuclear signals in type II cells, stronger than in control type II cells (littermates without Cre gene) (Fig. 2 A and E). This suggested a potential compensatory up-regulation of N1-ICD in the absence of N2-ICD.

Fig. S4.

FlexiVent analysis of lung function in adult Notch2 mutants. (A) Increased static compliance (Cst) and decreased airway resistance (Rn) (B), tissue elasticity (C), and tissue damping (D) were detected in Notch2cNull (n = 5) compared with Notch2cHetero (n = 5) and Cre-negative control mice (n = 5). Mean ± SD of three measurements, *P < 0.05.

Given the potential functional redundancy between Notch1 and Notch2 (18) and the less severe phenotype of Notch2cNull compared with Pofut1cNull, we examined the effect of the ablating a Notch1 allele in Notch2cNull background. Notch1cHete;2cNull showed a more marked enlargement of the distal airspaces suggestive of a more severe emphysema-like phenotype compared with single Notch2cNull (Fig. 2 K and L). We concluded that although Notch2 plays a more prominent role in alveologenesis, activation of Notch1 also contributes to this process.

Disruption of Epithelial Notch Signaling Inhibits AMYF Proliferation and Differentiation Through Epithelium–Mesenchyme Interactions.

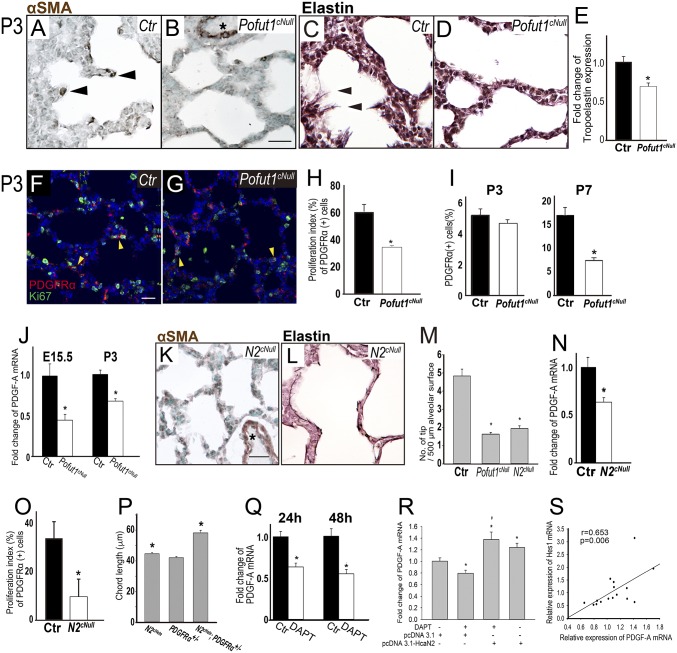

Because AMYF plays a crucial role in secondary septa formation (3, 19), we investigated myofibroblast differentiation in the alveologenesis defect of Notch-deficient mice. In control lungs at P3 α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA)-positive AMYFs are normally seen at the tip of the emerging secondary septa. In Pofut1cNull distal lungs at P3 these septa were nearly absent and the number of αSMA-positive AMYFs in primitive saccules was significantly decreased (Fig. 3 A, B, and M). By contrast, αSMA expression was unaffected in perivascular SM (Fig. 3 B and K, asterisk). Next, we analyzed the expression and distribution of elastin, which is deposited by AMYFs. In P3 controls, elastin was deposited at the tips of the septa and along the saccules, as expected (Fig. 3C). In contrast, elastic fiber formation was markedly decreased in the walls of P3 Pofut1cNull saccules (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, tropoelastin mRNA expression was decreased to 65% of controls in the lungs of Pofut1cNull mice (Fig. 3E). Quantitative analysis of the pool of PDGFR-α–positive AMYF progenitors showed a significant decrease in the number of proliferating PDGFR-α/Ki67 double-labeled cells in P3 Pofut1cNull lungs (Fig. 3 F–H). However, at P3 the overall number of PDGFR-α–positive progenitors was still similar in control and Pofut1cNull lungs. By contrast, by P7 the number of these progenitors significantly decreased in saccules walls of mutant lungs (Fig. 3I).

Fig. 3.

Inactivation of epithelial Notch signaling inhibits proliferation of mesenchymal AMYF progenitors. (A and B) Decreased number of αSMA-positive AMYFs (arrowheads) in (B) Pofut1cNull lungs compared with control (A) at P3. Asterisks indicate vascular SM. (C and D) Elastin staining revealed continuous elastin fibers with protrusions into the saccular space (arrowhead) in control (C). In contrast, only few protruding elastin fibers can be seen in Pofut1cNull lungs (D). (E) Tropoelastin mRNA significantly decreased in Pofut1cNull lungs. (M) Tip numbers of secondary septa significantly decreased in both Pofut1cNull and Notch2cNull lungs. (F and G) Proliferating AMYF progenitors are detected by PDGFR-α and Ki67 double staining of controls (F) and Pofut1cNull (G) lungs. The proliferation index estimated from the double staining was significantly reduced in Pofut1cNull and Notch2cNull lungs (H and O). (I) The number of PDGFR-α–positive AMFY progenitors was significantly decreased in Pofut1cNull lungs at P7, but not P3, during alveologenesis. (J and N) Real-time PCR showed significantly decreased PDGF-A mRNA expressions in Pofut1cNull (J) and Notch2cNull (N) lungs. AMYF differentiation (K) and elastin deposition (L) were also defective in Notch2cNull lungs. (P) Quantitative analysis revealed significantly increased chord length in Notch2cHete;PDGFR-α+/− mice at 3–6 mo old. DAPT (10 μM) inhibited PDGF-A mRNA expression in MLE15 cells (Q), and constitutively activated Notch2 signaling by transfection with HcaN2 plasmids rescued this phenomenon (R). Strongly positive correlation between levels of Hes1 and PDGF-A mRNA in MEL15 cells (S) (n = 3–5 in each group for quantification, *P < 0.05). (Scale bars, 10 μm.)

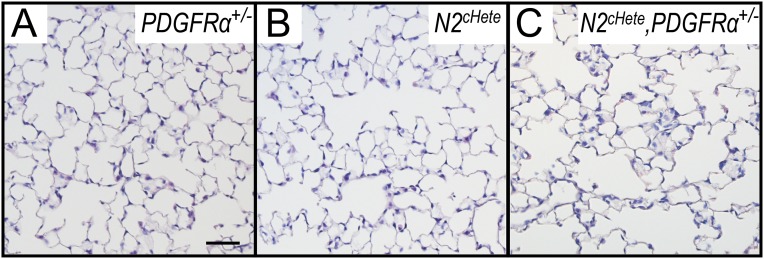

We investigated the effect of Notch deficiency in epithelial-derived paracrine signals that promote AMYF progenitor development. The epithelial-derived PDGF-A is essential for proliferation and differentiation of the PDGFR-α–positive AMYF progenitors (3, 20). PCR analysis of embryonic and postnatal lungs showed PDGF-A mRNA levels significantly decreased already at E15.5 and P3 Pofut1cNull lungs (Fig. 3J). We proposed that disruption of Notch2 signaling leading to low epithelial PDGF-A expression could ultimately result in the inability to form secondary septa postnatally. Indeed, as seen in Pofut1cNull mice, lungs from Notch2cNull mutants showed decreased proliferation and differentiation of PDGFR-α–expressing AMYF progenitors and decreased elastin deposition associated with low levels of epithelial PDGF-A expression (Fig. 3 K–O). Epistatic relation between Notch2 and PDGF signaling in alveologenesis was determined by generating Notch2cHete;PDGFR-α+/− mice. The double heterozygous adult mice showed longer mean alveolar cord length compared with single heterozygous [Fig. 3P; mean alveolar cord length (mean ± SEM): Notch2cHete, 44.6 ± 0.7 μm; PDGFR-α+/−, 42.1 ± 0.8 μm; Notch2cHete, PDGFR-α+/−, 58.2 ± 1.7 μm; Fig. S5].

Fig. S5.

Epistatic relation between Notch2 and PDGF signaling in alveologenesis. H&E staining of PDGFR-α+/− (A), Notch2cHete (B), and Notch2cHete;PDGFR-α+/− (C) determined an epistatic relationship between Notch2 and PDGF signaling in alveologenesis. (Scale bars, 50 μm.)

Consistent with this, blocking Notch signaling pharmacologically with gamma-secretase inhibitor (N-[N-(3, 5-difluorophenacetyl)-l-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester, DAPT) (21) in the alveolar type II cell line MLE 15 (22) decreased PDGF-A mRNA (Fig. 3Q). Notably, this effect could be reverted by expressing a constitutively active Notch2 (HcaN2) (Fig. 3R). In addition, expression of the Hes1 gene, a known target of Notch signaling, positively correlated with PDGF-A expression (Fig. 3S). Thus, Notch signaling controls proliferation of epithelial type II cells and mesenchymal AMYF progenitors through regulating PDGF-A expression.

Disrupted Epithelial Integrity and Impaired SM Development in Airways of Notch Null Mutants.

FlexiVent analyses of Notch2cNull mice (Fig. S4) revealed functional changes compatible with abnormalities in the alveolar and the distal airway compartments. This prompted us to examine whether small airways were also defective in Notch null mutant lungs. Markers analyses of adult Notch2cNull lungs revealed the expansion of the ciliated cell population at the costs of Club cells previously reported in other Notch-deficient mice (6, 7, 18). However, we also noticed E-cadherin (E-Cad) staining markedly attenuated in the distal airway epithelium Notch2cNull lungs compared with controls (Fig. 4 A and B). In some of these regions the epithelium became squamous-like (Fig. 4 I and J) and appeared discontinuous.

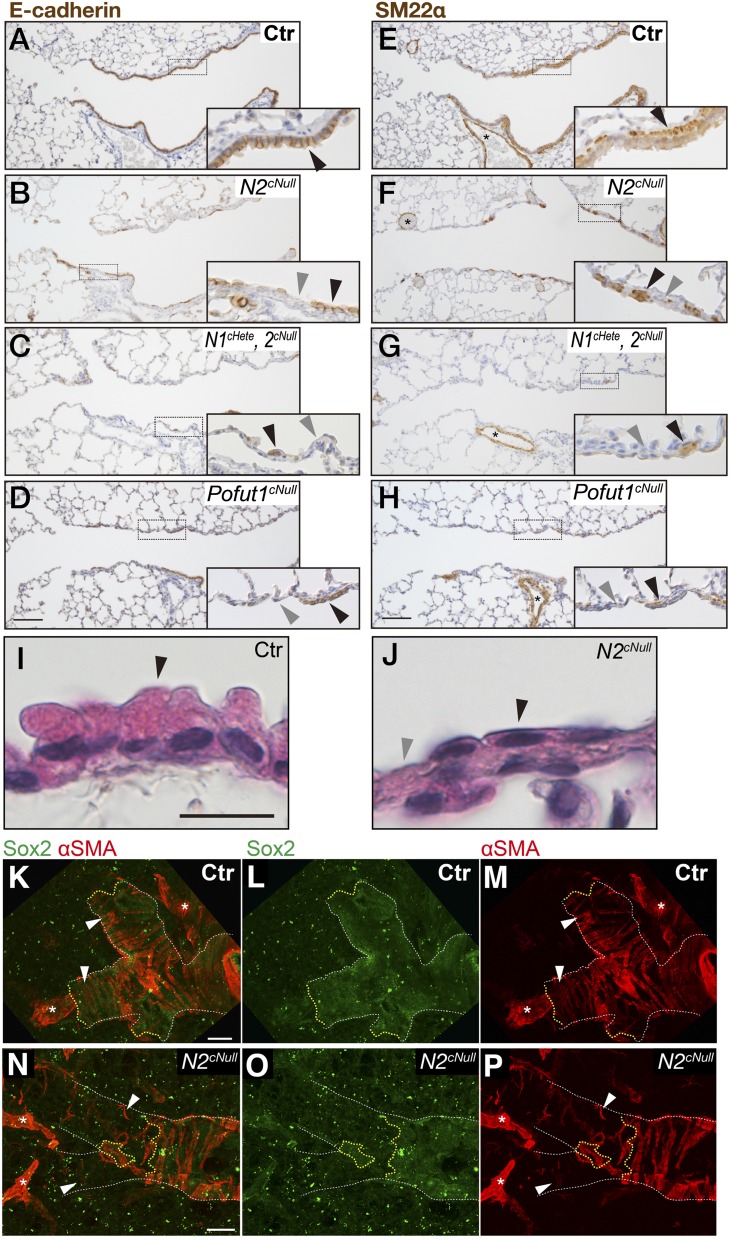

Fig. 4.

Epithelial Notch signaling is required for SM development in distal airways. Immunohistochemistry for E-Cad (A–D) and SM22α (E–H) in Pofut1cNull (pan-Notch signaling) compound Notch1cHete;Notch2cNull or Notch2cNull at P21 to 4 mo old. Distal airways showing discontinuous SM layer in areas of epithelial attenuation with squamous-like shape and loss of integrity, not seen in proximal regions. Phenotype is most severe in Pofut1cNull and Notch1cHete;Notch2cNull. (I and J) H&E staining revealed that the distal airway epithelium became squamous-like in appearance in adult Notch2cNull lungs. Black and gray arrowheads indicate the epithelial cells and defect in epithelium (A–D), SM, and defect in the subepithelial layer (E–H), respectively. (K–P) Double IF staining for epithelial Sox2 (K, L, N, and O) and mesenchymal αSMA (K, M, N, and P) in thick sections of the distal bronchiole of Notch2cNull showing correlation between epithelium and airway SM development. White and yellow lines outline shapes of the bronchioles and edges of epithelial sheet. White arrowheads indicate SM surrounding the distal-most bronchiole. In Notch2cNull SM failed to develop band-like tissue structure where the epithelial sheet is defective (N–P). Asterisks indicate vessels. (Scale bars, 100 μm in A–H and K–P and 10 μm in I and J.)

Interestingly, expression of the SM marker SM22α showed poorly developed or absence of airway SM in areas associated with the discontinuous epithelium (Fig. 4 E and F). Notch1cHete;2cNull and Pofut1cNull lungs displayed similar but more severe disruption of integrity of airway epithelial cells and SM (Fig. 4 C, D, G, and H). This defect was not seen in proximal airways (Fig. S6). To further check the topological correlation between epithelial and mesenchymal defect, double staining for epithelial Sox2 and mesenchymal αSMA (an SM marker) was performed in 150-μm-thick sections of the distal bronchioles (Fig. 4 K–P). This confirmed the preserved airway SM in distal airways associated with the Sox2-positive epithelium in controls, not present where the epithelium was discontinuous in the Notch2cNull airways (Fig. 4 N–P). The phenotype was not observed in E18.5 lungs (Fig. 5 A–E and Fig. S7), suggesting that these abnormalities occurred only postnatally.

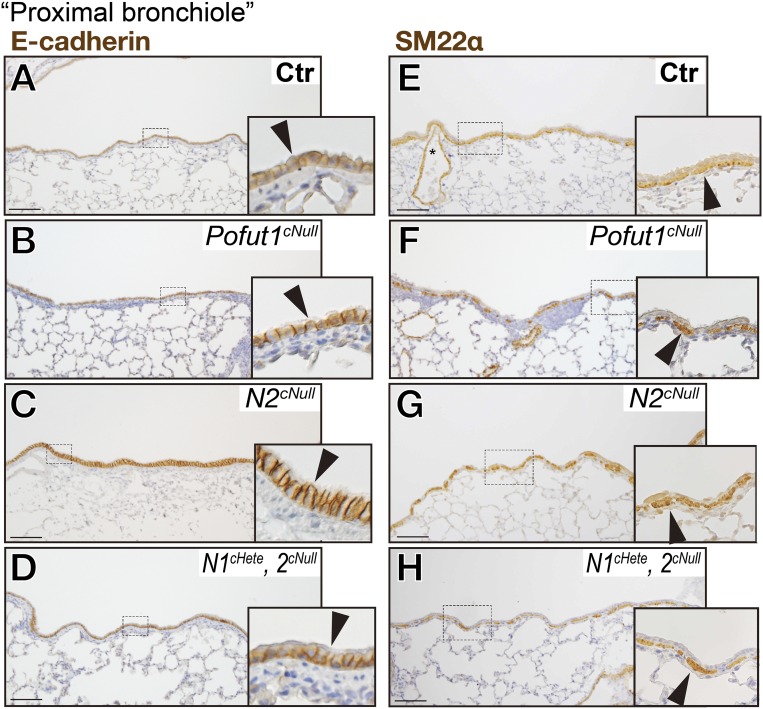

Fig. S6.

Preserved integrity of epithelial and airway SM layers in proximal airways. At P21 to 4 mo, immunostaining of E-Cad (A–D) and SM22α (E–H) showed Pofut1cNull (B and F), Notch2cNull (C and G), and Notch1cHete;2cNull (D and H) mice with preserved layers compared with controls (A and E). (Scale bars, 50 μm.)

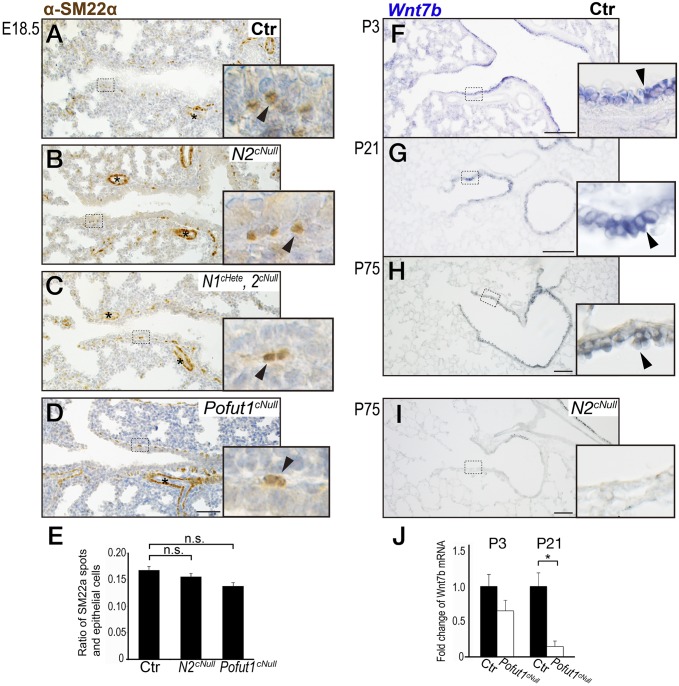

Fig. 5.

Integrity of the airway epithelium is required for SM development. (A–D) SM22α immunostaining of E18.5 lung showing continuous epithelial layer and SM layer unaltered in Notch mutants and control. (E) Quantification of the subepithelial αSMA-positive spots in Notch mutants and controls. (F and G) Wnt7b in situ hybridization in airway epithelium at P3 and P21. (H and I) Wnt7b expression significantly decreased in Notch2cNull lungs (I) compared with control (H). (J) RT-PCR showed a trend toward a decrease in expression in Wnt7b mRNA at P3 that becomes significant at P21 in Pofut1cNull mice compared with controls (n = 3–9 in each group). Error bars represent SEM. (Scale bars, 50 μm in A–D and 100 μm in F–I.)

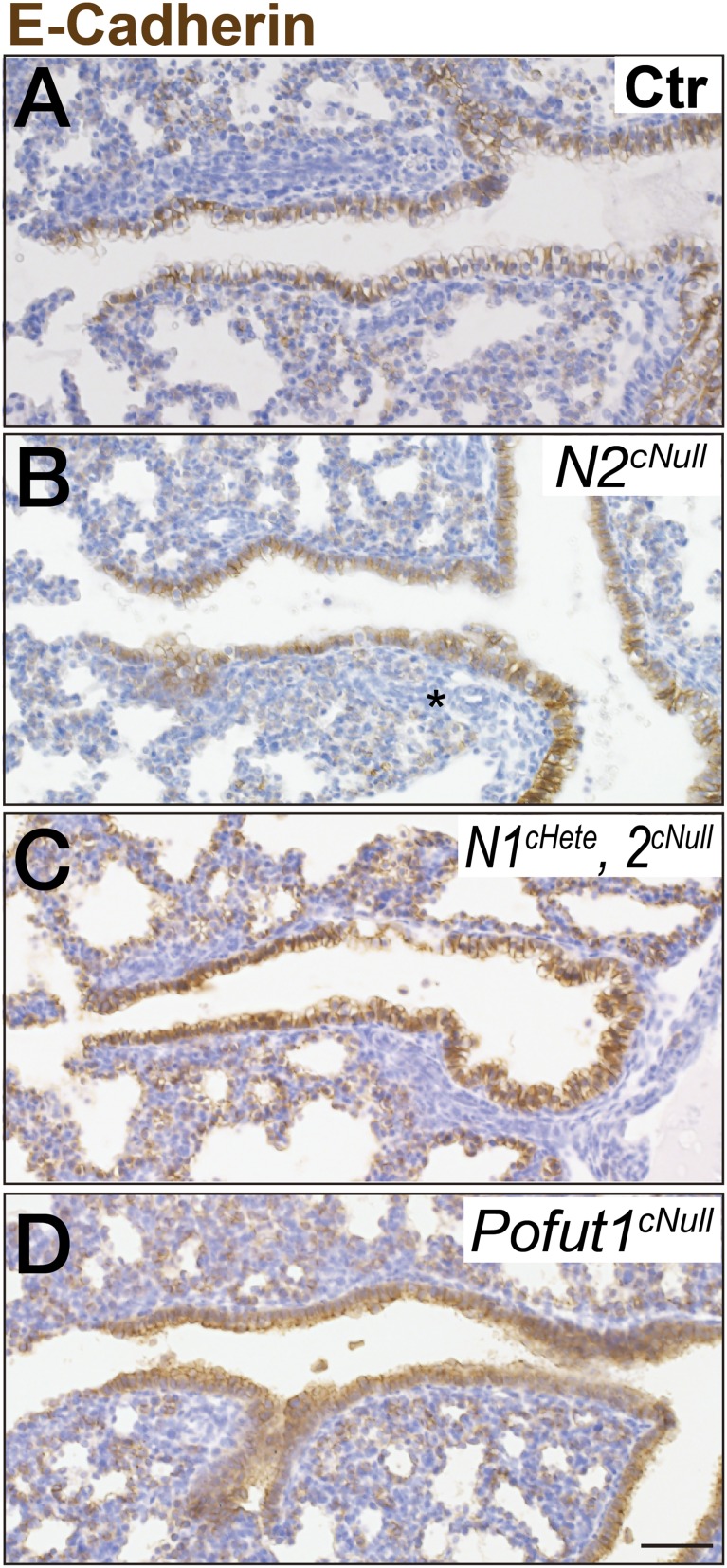

Fig. S7.

Preserved integrity of epithelium in prenatal airways. At E18.5, immunostaining of E-Cad of control (A), Notch2cNull (B), Notch1cHete;2cNull (C), and Pofut1cNull (D) mice showed normal development of epithelium in all genotypes. (Scale bars, 50 μm.)

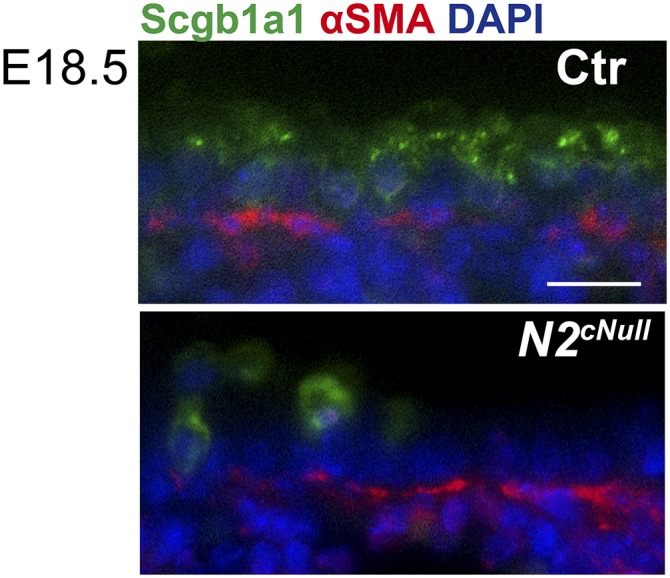

Because Shh-Cre does not target mesenchymal cells (23), the aberrant SM phenotype of Notch2cNull was likely to result primarily from an epithelial defect. In addition, we performed costaining of Scgb1a1b and αSMA for Notch2cNull or control and detected no topological relation of Club cells and airway SM cells (Fig. S8). This suggests that SM development is independent of the presence of Club cells in the developing airways.

Fig. S8.

There is no topological relation of Club cells and airway SM cells. Double immunostaining of Scgb1a1 and αSMA showed that the absence of Club cells per se does not correlate with the absence of airway SM. (Scale bars, 50 μm.)

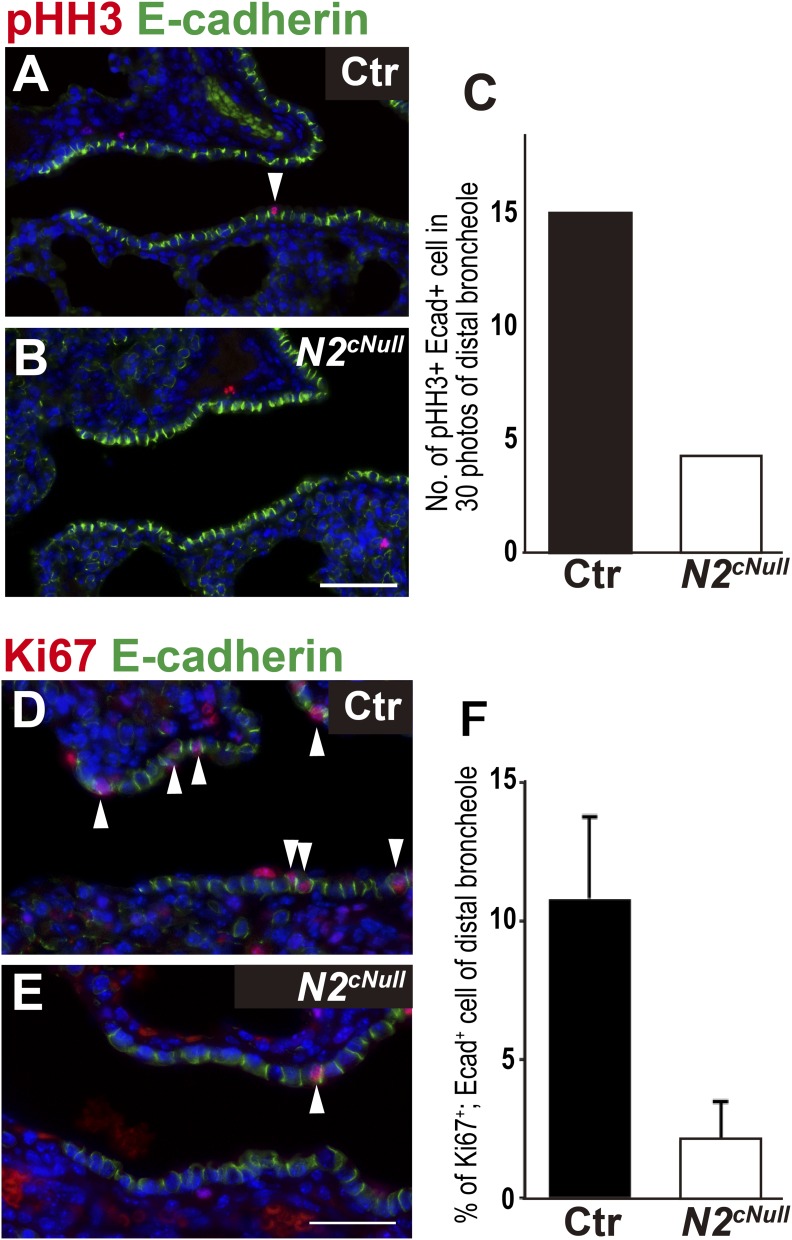

We compared the proliferation ratio of bronchiolar epithelial cells in control and Notch2cNull lungs by coimmunostaining for phosphor Histone H3 (pHH3) or Ki67 and E-Cad (Fig. S9 A, B, D, and E). Morphometric analysis of Notch2cNull bronchioles showed a reduction in the proliferating epithelial population (Fig. S9 C and F). This proliferation defect could be related to the reduction of Club cells, the major progenitor cells responsible for epithelial tissue maintenance in intrapulmonary airways (24).

Fig. S9.

Decreased epithelial proliferation in distal bronchioles of Notch2cNull mice. Lung epithelial proliferation was assayed by E-Cad and pHH3 (A and B) or Ki67 (D and E) double staining in control and Notch2cNull lungs at P4. (C and F) Number of E-Cad/pHH3 and E-Cad/ Ki67 double-positive cells in 30 photos of the distal bronchioles (n = 3 in each group). (Scale bars, 50 μm in A, B, D, and E.)

We examined other signals present in the airway epithelium potentially associated with airway SM development. Epithelial-secreted Wnt7b has been reported as a crucial inducer of airway SM in the developing lung (25). In situ hybridization of control lungs confirmed epithelial Wnt7b expression throughout the airway epithelium of P3 to P75 (Fig. 5 F–H), suggesting continuous contribution of this paracrine factor to postnatal airway SM development. Quantitative RT-PCR of Pofut1cNull lungs revealed reduction in Wnt7b expression particularly prominent at P21 compared with control (Fig. 5J). Notch2cNull adult lungs also showed decreased Wnt7b expression (Fig. 5I) (25, 26). Thus, disruption of Wnt7b-mediated epithelial–mesenchymal interactions could well contribute to the SM phenotype of Notch-deficient mice. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that other epithelium-secreted factors may also contribute to the defective SM phenotype.

Discussion

Despite the reported association between altered Notch signaling and abnormal distal lung development in mice, the role of Notch in lung alveolar formation has not been clearly defined. Issues include lack of unambiguous evidence that Notch is normally activated in the developing alveolar epithelium and uncertainties about alveolar epithelial sites of ligand expression.

Here we provide direct evidence of Notch2 activation in type II cells and genetic data supporting a unique contribution of Notch2 to alveologenesis. We show that Notch2 signaling is required for type II cell proliferation and maturation. Disruption of Notch signaling in the distal lung epithelium resulted in decreased expression of PDGF-A, indispensible for AMYF development in the distal mesenchyme, leading to defective alveologenesis. Moreover, we found decreased cellularity and loss of epithelial integrity in distal bronchioles with defective development of the adjacent SM layer. We ascribe the defects in both the alveolar and airway compartments to impaired epithelial–mesenchymal interactions in Notch-deficient mice

Lineage studies suggest that bronchiolar Club cells serve as a progenitor cell source, maintaining the bronchiolar epithelium at the postnatal period, but are not required for the integrity of the alveolar compartment (24). Indeed, alveolar defects have not been reported in mouse mutants in which Club cells have been ablated, such as in Scgb1a1-Cre–driven Sox2 deletion or in Scgb1a1-rtTA/tetO-Cre/R26-lacZ:DT-A transgenic mice (27, 28). Thus, the defect in alveologenesis is unlikely to be causally linked to the loss of Club cells. Interestingly, our Notch mutants lack the Club cells before birth (7), in contrast to the models described above. This may account for the different outcome, raising the possibility that integrity of Club cells prenatally, although not affecting saccular formation, may be required for normal alveologenesis. Alternatively, lung epithelial activation of Notch signaling prenatally could be required for alveologenesis, as suggested by the Notch-deficient disruption of AMYF differentiation.

We propose that Notch2 activity in epithelial cells regulates epithelial–mesenchymal interactions crucial for development and homeostasis of the distal lung (alveoli and distal bronchiole) during postnatal life. Our study shows a clear association between the epithelial defect and aberrant SM in Notch2-deficient mutants. Notch2 exert its effects likely thorough epithelial-derived paracrine factors, such as Wnt7b and PDGFA, candidate mediators of SM and AMYF differentiation in the bronchoalveolar compartment. In addition, the more severe distal lung phenotype in Notch1cHete;2cNull compared with Notch2cNull mice suggests a cooperative effect of Notch1 and Notch2 in alveolar formation. Disrupted morphogenesis of distal airways has been associated with lung immaturity in conditions such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature infants (29). Abnormal repair of alveolar and small airways after lung injury also lead to insufficient gas-exchange surface associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the adult (30).

Gene mutations resulting in loss of function of NOTCH2 or the ligand JAG1 have been causally linked to Alagille syndrome. This multisystem disorder includes abnormalities in liver, skeleton, eye, heart, and kidney (31). Interestingly, we have preliminary radiological evidence of diffuse emphysema-like changes in Allagile patients carrying JAG1 mutation, although this limited cohort did not contain patients with NOTCH2 mutations. In humans, 94% of Alagille patients harbor Jag1 mutations, but the disease can also result from loss of one Notch2 allele (31). This is of interest, given that disruption of alveolar formation has been previously described in mice with conditional deletion of Jag1 in lung epithelium (13), a phenotype also seen in our Notch2cNull mice.

The accumulated evidence of the role of Notch in the lung suggests the potential benefit of targeting this pathway in pulmonary disorders affecting the airway or alveolar epithelium.

Methods

Pofut1F/F (5), Notch1 F/F, and Notch2 F/F were mated to mice carrying the ShhCre allele (23) to generate mutant embryos as in our previous reports (7, 18). PDGFR-α+/− mice (32) were mated with ShhCre;Notch2f/+ for epistatic analysis. All mice were maintained on the C57BL/6 × CD1 mixed background, and ShhCre mice were on a C57BL/6 background. All animal experiments were approved by the Experimental Animal Use Committee of RIKEN Center of Developmental Biology or National Taiwan University Hospital. All other detailed methods, including information on antibodies (Table S1), the sequence of PCR primers for real-time PCR (Table S2), and the validation of the N2-ICD antibody (Fig. S10), are described in the SI Methods.

Table S1.

The individual conditions for immunohistochemistry

| Antibody and dilution | Company and catalog no. | Fixative | Tissue preparation | Antigen retrieval | Second antibody | Amplification |

| Cleaved Caspase3 | Cell Signaling Technology, 9661S | 4% PFA* | Paraffin | 95 °C 5 min in AUS† | α-Rabbit | — |

| Scgb1a1 (T-18), 1:300 | Santa Cruz, sc-9772 | 4% PFA* | Paraffin | 105 °C 15 min in HistoVT One‡ | α-Goat-Alexa594§ | — |

| E-cadherin (24E10), 1:1,000 | Cell Signaling Technology, 3195 | 4% PFA* | Paraffin | 105 °C 15 min in HistoVT One‡ | α-Rabbit-Alexa594¶ | — |

| E-cadherin (24E10), 1:1,000 | Cell Signaling Technology, 3195 | 4% PFA* | Paraffin | 105 °C 15 min in HistoVT One‡ | α-Rabbit-Biotin# | ABC|| and DAB detection |

| PDGFR-α, 1:500 | Cell Signaling Technology | 4% PFA* | Paraffin | 95 °C 5 min in AUS** | α-rabbit-Alexa594¶ | — |

| GFP, 1:600 | MBL, 598 | 4% PFA* | Paraffin | 105 °C 15 min in HistoVT One‡ | α-Rabbit-Alexa488†† | — |

| p-Histon H3, 1:500 | Santa Cruz, sc-12917 | 4% PFA* | Paraffin | 105 °C 15 min in HistoVT One‡ | α-Goat-Alexa488‡‡ | — |

| Ki67, 1:100 | BD, 550609 | 4% PFA* | Paraffin | 95 °C 5 min in AUS** | α-Mouse-Alexa594 | — |

| N1-ICD, 1:300 | Cell Signaling Technology, 4147 | 4% PFA* | Paraffin | 105 °C 15 min in HistoONE‡ | α-Rabbit-Biotin# | ABC|| and TSA-Cy3§§ |

| N2-ICD, 1:500 | Abcam, ab52302 | 4% PFA* | Paraffin | 95 °C 5 min in AUS** | α-Rabbit | ABC|| and TSA-Cy3§§ |

| Pro-SPC, 1:1,000 | Chemicon, AB3786 | 4% PFA* | Paraffin | 105 °C 15 min in HistoONE‡ | α-Rabbit-Alexa488†† | — |

| SM22α, 1:10,000 | Abcam, ab14106 | 4% PFA* | Paraffin | 105 °C 15 min in HistoVT One‡ | α-Rabbit-Alexa488†† | — |

| SMA, 1:300 | Genetex, 100095 | 4% PFA* | Paraffin | 95 °C 5 min in AUS** | α-Rabbit | — |

| SMA-Cy3, 1:300 | Sigma, C6198 | 0.5% PFA* | OCT-frozen | 95 °C 5 min in AUS† | — | — |

| Sox2, 1:100 | Santa Cruz, sc-17320 | 0.5% PFA* | OCT-frozen | 95 °C 5 min in AUS† | α-Goat-Alexa488‡‡ | — |

| T1α | Abcam, 11936 | 4% PFA* | Paraffin | 95 °C 5 min in AUS** | α-Hamster | ABC|| and TSA-Cy3§§ |

| Nkx2.1 | Leika NCL-L-TTF-1 | 4% PFA* | Paraffin | 95 °C 5 min in AUS† | α-Mouse-Alexa594 | |

| ABCa3 | Seven Hills Bioreagents, WRAB-70565 | 4% PFA* | Paraffin | 95 °C 5 min in AUS† | α-Rabbit-Alexa594¶ |

Paraformaldehyde (Sigma).

Antigen unmasking solution, citric acid-based (Vector Laboratory, Inc.).

HistoVT One (nacalai tesque).

Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-goat IgG (invitrogen).

Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (invitrogen).

Biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG, made in goat (Vector Laboratory, Inc.).

VECTASTAIN ABC Kit (Vector Laboratory, Inc.).

Trilogy antigen unmasking solution (Cell Marque).

Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (invitrogen).

Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-goat IgG (invitrogen).

TSA Cyanine 3 Tyramide Reagent Pack (PerkinElmer). The ABC kit was used before TSA-Cy3 in our protocol.

Table S2.

Sequence of PCR primers for real-time PCR

| Primer | Sequence |

| PDGF-A-F | GAGGAAGCCGAGATACCCC |

| PDGF-A-R | TGCTGTGGATCTGACTTCGAG |

| SMA-F | GTCCCAGACATCAGGGAGTAA |

| SMA-R | TCGGATACTTCAGCGTCAGGA |

| Tropoelastin-F | TTGCTGATCCTCTTGCTCAAC |

| Tropoelastin-R | GCCCCTGGATAATAGACTCCAC |

| SP-C-F | ATGGACATGAGTAGCAAAGAGGT |

| SP-C-R | CACGATGAGAAGGCGTTTGAG |

| AQP5-F | AGAAGGAGGTGTGTTCAGTTGC |

| AQP5-R | GCCAGAGTAATGGCCGGAT |

| Wnt7b-F | TTTGGCGTCCTCTACGTGAAG |

| Wnt7b-R | CCCCGATCACAATGATGGCA |

| CC10-F | CACCAAAGCCTCCAACCTCTAC |

| CC10-R | GGGATGCCACATAACCAGACTC |

| Foxj1-F | ATCGTCGTGCACATCTCGAAG |

| Foxj1-R | AGCAGAAGTTGTCCGTGATC |

| CGRP-F | GAGGGCTCTAGCTTGGACAG |

| CGRP-R | AAGGTGTGAAACTTGTTGAGGT |

| Gapdh-F | AATGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTGA |

| Gapdh-R | GATGCCTGCTTCACCACCTTCT |

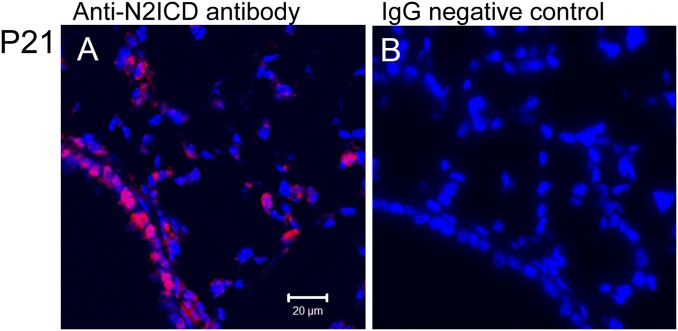

Fig. S10.

Validity of the N2-ICD antibody. Notch2 ICD staining was visible in airway and alveolar epithelium (A); however, it was invisible after replacing the Notch2ICD antibody with control IgG (B).

SI Methods

Immunohistochemistry.

Lungs were inflated with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 1 h to overnight at 4 °C and embedded in paraffin. Antibodies and staining conditions are described in Table S1. The staining for N2-ICD was performed as previously described (33). Briefly, after incubation of the N2-ICD antibody, the sections were treated with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch), tyramide-conjugated FITC (NEN, 1:1,000; PerkinElmer), and then HRP-conjugated anti-fluorescein antibody. The antigen was then visualized with tyramide-conjugated Cy3 (TSA-Plus Cyanine 3, 1:500; PerkinElmer). Validity of the N2-ICD antibody was confirmed by lack of signals in negative controls (Fig. S10) and sections of Notch2cNull lungs. Stained sections are analyzed using a Zeiss confocal laser-scanning microscope (LSM510 META and LSM710) and Olympus IX71 with DP73 camera as in previous reports (6, 21).

Epithelial–Mesenchymal Correlation Analysis.

Samples were prepared according to ref. 34. Briefly, the lungs from 2-mo-old mice were inflated with 0.5% PFA (P6148; Sigma) in PBS at 30 cm H2O pressure and incubated with 0.5% PFA in PBS at room temperature for 3 h. The fixed lungs were cryoprotected in optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT) (4583; Tissue-Tek) following washing with PBS at 4 °C overnight and 30% (wt/vol) sucrose treatment. Frozen tissues were sectioned at 150-μm thickness and adhered to slide glasses (S9903; MATSUNAMI) and dried overnight, which compresses thick sections. The conditions of immunohistochemistry with anti-Sox2 and -SMA antibodies are described in Table S1. Stained sections were imaged on the inverted Zeiss 710 confocal microscope with a 25× objective (LCI Plane Apochromat LD). Seven to 10 Z-stack sectional images were scanned to cover 13.8-μm thickness of the tissue and combined with the max projection method using ZEN software.

Morphometric Analysis.

Digital images of airways were acquired using a Leica DM750 light-emitting diode microscope. Alveolar size was assessed by measuring alveolar chord length using the NIH ImageJ program (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) according to American Thoracic Society guidelines (35). A minimum of 10 representative, nonoverlapping fields from lungs of at least three mice of each group were evaluated. The percentage of labeled epithelial cells immunostained for Ki-67 and SPC or PDGFR-α was performed as previously described (7, 9). The numbers of SPC/PDGFR-α and/or Ki67/SPC or PDGFR-α double-positive cells were counted in 21 photos of three biological samples. The number of the double-positive population was divided by total SPC- or PDGFR-α–positive cells to estimate the percentages of proliferating type II or AMYF cells.

FlexiVent Analysis.

A detailed procedure has been previously reported in refs. 36 and 37. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg of pentobarbital sodium and a tracheotomy was performed to attach mice to the small animal ventilator (flexiVent; SCIREQ). Mice received ventilation with a tidal volume of 8 mL/kg at a frequency of 150 breaths per min. Respiratory mechanics were assessed at five different PEEP levels (1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 cm H2O) using an 8-s, broadband low-frequency forced oscillation maneuver, Prime-8 perturbation, following two inflations to 30 cm H2O to standardize volume history. Respiratory system resistance (Rrs) and elastance (Ers) were calculated in the flexiVent software by fitting the equation and airway resistance (Rn), tissue elasticity (H), and tissue damping (resistance) (G) were determined. Quasi-static pressure–volume perturbation was applied to obtain static compliance (Cst) using PVr-P perturbation, a 16-s, triangular pressure-controlled perturbation up to 25 cm H2O. All perturbations were conducted until three correct measurements were performed for each mouse, and the results were averaged.

Isolation of Alveolar Type II Cells.

The lungs of P14 Notch2cNull or control mice were filled with Dispase (354235; Becton Dickinson) after isolation from the thorax. The isolated lungs were soaked in HBSS and incubated for 45 min at room temperature. Distal lung tissues were picked off the lungs by forceps and pipetted 20 times in PBS plus 10% (vol/vol) FBS (Invitrogen). Following incubation with DNaseI (0.5 mg/mL, D7691; Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min, cells were filtered through a 70-μm-pore and 40-μm-pore nylon net strainer (352350 and 352340; BD Falcon). Separated cells were washed with PBS plus 10% (vol/vol) FBS, heparin (22600AMX00809000, 20 U/mL; Mochida Pharmaceutical Co.), and resuspended with RBC lysis buffer (420301; Biolegend) to remove red blood cells and washed again. Cells were resuspended in a mixture of antibodies, including anti–CD45-PE-Cy7, –CD31-PE-Cy7, –EpCAM-APC, and –MHC classII-eFluor450 (Biolegend) and incubated for 20 min at 4 °C. Labeled cells were washed and resuspended in PBS/2% (vol/vol) FBS and 7-aminoactinomycin D (559925; Becton Dickinson) then kept on ice for flow cytometric analysis and sorting. To isolate alveolar type II cells, we sorted CD45-negative (nonhematopoietic) and CD31-negative (nonendothelial) cells from the cell suspensions and isolated type II cells on the basis of the differential expression of EpCAM (epithelial) and the MHC class II (type II cell) antigen. Analysis was performed using FACS AriaII Cell Sorting System (Becton Dickinson).

Lung Epithelium Culture and Transfection in Vitro.

MLE15 cells, a murine type II cell line that expresses PDGF-A endogenously, were transfected with 1.0 μg of constitutive active Notch2 intracelluar domain (caN2) or vector constructs to constitutively activate Notch2 signaling (38). The transfected cells were treated with DAPT (10 μM, Sigma) or DMSO (control) for 48 h (21).

Real-Time PCR.

Total RNA from lung tissues or cell lines was isolated using the TRIzol method. For reverse transcription, 2 µg of total RNA were transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). Real-time RT-PCR was performed in a DNA Engine Opticon 2 (Bio-Rad) using iQ SYBR Green supermix (Bio-Rad). Briefly, 100 ng of the reverse-transcribed cDNA were used for each PCR with 250 nM of forward and reverse primers. The primer sequences for real-time PCR are presented in Table S2. The threshold cycle (CT) values were obtained for the reactions, reflecting the quantity of the product in the sample. The relative concentration of RNA for each gene to GAPDH mRNA was determined using the equation 2−ΔCT, where ΔCT = (CTmRNA – CTGAPDHmRNA).

Statistics.

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test; differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank the second Core Laboratory of the Department of Medical Research of National Taiwan University Hospital and National Laboratory Animal Center for technical assistance. This work was supported by funding from Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (A) 26713029 and 23689044 and Challenging Exploratory Research Grant 16K15463 of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to M. Mitsuru); National Health Research Institutes Grants EX102-9924SC, Ministry of Science and Technology Grant 101-2628-B-002-002-MY4 and 104-2627-M-002-012, National Taiwan University Grant 105R7751, and National Taiwan University Hospital Grant 105-P07 (to P.-N.T.); and NIH Grant 5R01HL105971 (to W.V.C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. X.S. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1511236113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Massaro D, Massaro GD. Developmental alveologenesis: Longer, differential regulation and perhaps more danger. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293(3):L568–L569. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00258.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wendel DP, Taylor DG, Albertine KH, Keating MT, Li DY. Impaired distal airway development in mice lacking elastin. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;23(3):320–326. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.3.3906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boström H, et al. PDGF-A signaling is a critical event in lung alveolar myofibroblast development and alveogenesis. Cell. 1996;85(6):863–873. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopan R, Ilagan MX. The canonical Notch signaling pathway: Unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell. 2009;137(2):216–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi S, Stanley P. Protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 is an essential component of Notch signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(9):5234–5239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0831126100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morimoto M, et al. Canonical Notch signaling in the developing lung is required for determination of arterial smooth muscle cells and selection of Clara versus ciliated cell fate. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 2):213–224. doi: 10.1242/jcs.058669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsao PN, et al. Notch signaling controls the balance of ciliated and secretory cell fates in developing airways. Development. 2009;136(13):2297–2307. doi: 10.1242/dev.034884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rock JR, et al. Notch-dependent differentiation of adult airway basal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(6):639–648. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsao PN, et al. Notch signaling prevents mucous metaplasia in mouse conducting airways during postnatal development. Development. 2011;138(16):3533–3543. doi: 10.1242/dev.063727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xing Y, Li A, Borok Z, Li C, Minoo P. NOTCH1 is required for regeneration of Clara cells during repair of airway injury. Stem Cells. 2012;30(5):946–955. doi: 10.1002/stem.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guseh JS, et al. Notch signaling promotes airway mucous metaplasia and inhibits alveolar development. Development. 2009;136(10):1751–1759. doi: 10.1242/dev.029249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu K, et al. Lunatic Fringe-mediated Notch signaling is required for lung alveogenesis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;298(1):L45–L56. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90550.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang S, Loch AJ, Radtke F, Egan SE, Xu K. Jagged1 is the major regulator of Notch-dependent cell fate in proximal airways. Dev Dyn. 2013;242(6):678–686. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Tuyl M, et al. Overexpression of lunatic fringe does not affect epithelial cell differentiation in the developing mouse lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288(4):L672–L682. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00247.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krebs LT, et al. Characterization of Notch3-deficient mice: Normal embryonic development and absence of genetic interactions with a Notch1 mutation. Genesis. 2003;37(3):139–143. doi: 10.1002/gene.10241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uyttendaele H, et al. Notch4/int-3, a mammary proto-oncogene, is an endothelial cell-specific mammalian Notch gene. Development. 1996;122(7):2251–2259. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.7.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desai TJ, Brownfield DG, Krasnow MA. Alveolar progenitor and stem cells in lung development, renewal and cancer. Nature. 2014;507(7491):190–194. doi: 10.1038/nature12930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morimoto M, Nishinakamura R, Saga Y, Kopan R. Different assemblies of Notch receptors coordinate the distribution of the major bronchial Clara, ciliated and neuroendocrine cells. Development. 2012;139(23):4365–4373. doi: 10.1242/dev.083840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amy RW, Bowes D, Burri PH, Haines J, Thurlbeck WM. Postnatal growth of the mouse lung. J Anat. 1977;124(Pt 1):131–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindahl P, et al. Alveogenesis failure in PDGF-A-deficient mice is coupled to lack of distal spreading of alveolar smooth muscle cell progenitors during lung development. Development. 1997;124(20):3943–3953. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.20.3943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsao PN, et al. Gamma-secretase activation of notch signaling regulates the balance of proximal and distal fates in progenitor cells of the developing lung. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(43):29532–29544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801565200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wikenheiser KA, et al. Production of immortalized distal respiratory epithelial cell lines from surfactant protein C/simian virus 40 large tumor antigen transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(23):11029–11033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris KS, Zhang Z, McManus MT, Harfe BD, Sun X. Dicer function is essential for lung epithelium morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(7):2208–2213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510839103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rawlins EL, et al. The role of Scgb1a1+ Clara cells in the long-term maintenance and repair of lung airway, but not alveolar, epithelium. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(6):525–534. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shu W, Jiang YQ, Lu MM, Morrisey EE. Wnt7b regulates mesenchymal proliferation and vascular development in the lung. Development. 2002;129(20):4831–4842. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.20.4831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen ED, et al. Wnt signaling regulates smooth muscle precursor development in the mouse lung via a tenascin C/PDGFR pathway. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(9):2538–2549. doi: 10.1172/JCI38079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tompkins DH, et al. Sox2 is required for maintenance and differentiation of bronchiolar Clara, ciliated, and goblet cells. PLoS One. 2009;4(12):e8248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stripp BR, et al. Clara cell secretory protein: A determinant of PCB bioaccumulation in mammals. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(4 Pt 1):L656–L664. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.4.L656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gien J, Kinsella JP. Pathogenesis and treatment of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23(3):305–313. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328346577f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuder RM, Petrache I. Pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(8):2749–2755. doi: 10.1172/JCI60324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turnpenny PD, Ellard S. Alagille syndrome: Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20(3):251–257. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding G, Tanaka Y, Hayashi M, Nishikawa S, Kataoka H. PDGF receptor alpha+ mesoderm contributes to endothelial and hematopoietic cells in mice. Dev Dyn. 2013;242(3):254–268. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng HT, et al. Notch2, but not Notch1, is required for proximal fate acquisition in the mammalian nephron. Development. 2007;134(4):801–811. doi: 10.1242/dev.02773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alanis DM, Chang DR, Akiyama H, Krasnow MA, Chen J. Two nested developmental waves demarcate a compartment boundary in the mouse lung. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3923. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsia CC, Hyde DM, Ochs M, Weibel ER. An official research policy statement of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society: Standards for quantitative assessment of lung structure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(4):394–418. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200809-1522ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fust A, Bates JH, Ludwig MS. Mechanical properties of mouse distal lung: In vivo versus in vitro comparison. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;143(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ikegami M, et al. Deficiency of SP-B reveals protective role of SP-C during oxygen lung injury. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92(2):519–526. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00459.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Small D, et al. Soluble Jagged 1 represses the function of its transmembrane form to induce the formation of the Src-dependent chord-like phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(34):32022–32030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]