Abstract

Fibrillin proteins constitute the backbone of extracellular macromolecular microfibrils. Mutations in fibrillins cause heritable connective tissue disorders, including Marfan syndrome, dominant Weill-Marchesani syndrome, and stiff skin syndrome. Fibronectin provides a critical scaffold for microfibril assembly in cell culture models.

Full length recombinant fibrillin-1 was expressed by HEK 293 cells, which deposited the secreted protein in a punctate pattern on the cell surface. Co-cultured fibroblasts consistently triggered assembly of recombinant fibrillin-1, which was dependent on a fibronectin network formed by the fibroblasts. Deposition of recombinant fibrillin-1 on fibronectin fibers occurred first in discrete packages that subsequently extended along fibronectin fibers. Mutant fibrillin-1 harboring either a cysteine 204 to serine mutation or a RGD to RGA mutation which prevents integrin binding, did not affect fibrillin-1 assembly. In conclusion, we developed a modifiable recombinant full-length fibrillin-1 assembly system that allows for rapid analysis of critical roles in fibrillin assembly and functionality. This system can be used to study the contributions of specific residues, domains or regions of fibrillin-1 to the biogenesis and functionality of microfibrils. It provides also a method to evaluate disease-causing mutations, and to produce microfibril-containing matrices for tissue engineering applications for example in designing novel vascular grafts or stents.

Keywords: biomacromolecular assembly, microfibrils, fibrillins, cell models, tissue engineering

INTRODUCTION

Microfibrils are extracellular fibers, 10–12 nm in diameter, found primarily in conjunction with elastic fibers or associated with basement membranes.1 These fibers are ubiquitously distributed and abundant in cardiovascular, skeletal and ocular tissues, where they confer mechanical stability and tissue integrity.2 Microfibrils provide support for the tissue architecture in the eye and kidney, and they provide a critical scaffold for elastic fiber assembly and homeostasis in elastic tissues. Furthermore, microfibrils are the pivotal structures involved in storage and regulation of growth factors of the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) superfamily, including TGF-β and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs).3,4

The major backbone components of microfibrils are three highly homologous, large (~350 kDa) proteins, fibrillin-1, -2 and -3, all encoded by different genes.2,5–7 Similar to other extracellular glycoproteins, fibrillins are composed of tandem arrays of individual domains.8 Domains with homology to the epidermal growth factor (EGF) precursor constitute the majority of each fibrillin molecule. Many of them bind calcium (cbEGF domains), which is important for homotypic interaction,9 protection against proteolysis,10 mediating ligand interactions,11–13 and structural stabilization.11,14–17 Other domains include the TGF-β binding protein-like (TB) domains and the hybrid domains. Fibrillins contain the most cysteine residues (~13%) among all extracellular matrix proteins,18 the majority of which form intramolecular disulfide bonds stabilizing the conformation of the modular domains.

Fibrillin-1 is highly expressed by mesenchymal cells and assembled with a number of other proteins into highly organized microfibrils.19,20 Cells of epithelial origin also secrete fibrillins, but typically cannot assemble microfibrils, which suggests that important accessory assembly proteins are missing.21 However, recently it was shown that retinal pigmented epithelial cells can deposit fibrillin microfibrils, but that this was dependent on syndecan-4, not fibronectin.22 Based on the studies with mesenchymal cells, some key assembly events have been characterized. After the required processing of the propeptides,23,24 fibrillin assembly proceeds on the cell surface. Self-assembly of fibrillin microfibrils has been described and shown to be mediated by N- to C-terminal interactions.9,15,25,26 The C-terminus of fibrillins can undergo multimerization into a bead-like structure, similar to the beads in microfibrils, which in turn promotes the interaction with the N-terminus.27 These C-terminal multimers occur as a consequence of the formation of intermolecular disulfide bonds during or directly after secretion. This correlates with previous data using metabolic labeling of aorta organ cultures, which demonstrated that fibrillin becomes disulfide bonded with itself or with other proteins soon after secretion.28 The unique surface exposed unpaired Cys204 in the hybrid 1 domain of fibrillin-1 is likely involved in such a cross-link.28,29 However, deletion of the hybrid 1 domain in a mouse model did not show a microfibril assembly phenotype.30 Conserved RGD sequences in fibrillins interact with integrin cell surface receptors αvβ3, α5β1, αvβ6, and α8β1.31–37 Fibrillin-1 contains one single highly conserved RGD site in the 4th TB domain which interacts with integrins and regulates cell attachment.31,33,38 An RGD to RGA mutation in a recombinant fibrillin-1 fragment abolished the interaction with integrins.32 A targeted RGD to RGE mutation in mouse resulted in an accumulation of microfibrils in the skin giving rise to a stiff skin phenotype, indicating that fibrillin-1 assembly is negatively regulated by the interaction with integrins.39 Fibrillin assembly by mesenchymal cells was described to be strictly dependent on the availability of a fibronectin network.40–42 Indirect evidence for a role of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans in the fibrillin assembly process were obtained with soluble heparin and heparan sulfate which inhibited microfibril formation in cell culture.12,43

Mutations in fibrillins give rise to a wide spectrum of heritable connective tissue disorders including Marfan syndrome, geleophysic dysplasia, acromicric dysplasia, stiff skin syndrome, familial aortic aneurysm/dissection, autosomal dominant Weill-Marchesani syndrome, familial ectopia lentis, and others.44–48 The autosomal dominant Marfan syndrome is the most common disorder associated with mutations in fibrillin-1 (prevalence 1–2 in 5,000), with major clinical symptoms in the cardiovascular, skeletal and ocular systems. The disease progression in affected tissue represents the combined consequence of a loss in tissue integrity and perturbed TGF-β signaling.49 Deficiencies in microfibrils and elastic fibers contribute to the dissection and rupture of the aortic wall. Studies using tissues and cells from affected individuals indicate that the biogenesis of microfibrils is often compromised in individuals with Marfan syndrome.23,50–55

Individuals with existing aneurysms are advised to undergo prophylactic aortic root surgery when the aneurysm reaches critical dimensions to prevent acute dissection.56 Tissue engineering approaches using self-assembled peptides and proteins to guide the cellularization of biomaterials are a key concept in regenerative medicine.57 Developing novel biocompatible materials is crucial to improve cell survival, differentiation, extracellular matrix production and to ultimately produce human tissue mimetics.58 For example, the use of synthetic grafts to replace diseased parts of the ascending aorta is standard practice in patients with Marfan syndrome. Since microfibrils and elastic fibers are essential for the biomechanical properties of the arterial wall, they constitute important components in engineering aortic replacement tissue.59 In order to replace synthetic grafts in the future with appropriate tissue-engineered biological tissue, it is necessary to understand the basic principles of the macromolecular assembly of microfibrils and elastic fibers, and to recombinantly express relevant human extracellular proteins.

In this study, we have developed a modifiable recombinant fibrillin assembly assay using HEK 293 cells in co-culture with mesenchymal cells. In this system, fibrillin-1 becomes deposited in discrete packages onto existing fibronectin fibers. These deposits extend along the fibronectin fibers. Similar observations were made with fibroblasts analyzed at low cell densities. A Cys204 and RGD1543 mutation did not affect early fibrillin-1 assembly. This recombinant system provides a novel method to study how specific fibrillin-1 mutations affect the biogenesis of microfibrils as well as subsequent cellular consequences. The system has potential for tissue engineering applications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning of the rFBN1-FL constructs and site directed mutagenesis

The plasmid for the recombinant full length fibrillin-1 (rFBN1-FL) construct was generated by ligating the 4,290 bp ApaI × PmlI fragment from pBS-rF6 with the 9,875 bp ApaI × PmlI fragment from pDNSP-rF16, resulting in a 14,165 bp plasmid, termed pDNSP-rFBN1-FL. Both original plasmids, pDNSP-rF16 and pBS-rF6, which code for the N-terminal and C-terminal halves of fibrillin-1, respectively, have been described previously.25,60 To generate the mutant construct replacing the unpaired Cys204 with Ser in the first hybrid domain, a c.610T>A mutation was introduced with the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) into the existing plasmid pDNSP-rF1F,61 using the primer pair 5′-CTCAGCGGGATTGTCAGCACAAAAACGCTCTG-3′ and 5′-CAGAGCGTTTTTGTGCTGACAATCCCGCTGAG-3′. A 929 bp Nhe × KpnI fragment was then cloned into pDNSP-rF16 and the resulting plasmid was termed pDNSP-rF16-Cys. To generate the plasmid for the full length fibrillin-1 containing the sequence for the Cys204 to Ser mutation, the 4,290 bp ApaI × PmlI fragment from pBS-rF6 was ligated with the 9,875 bp ApaI × PmlI fragment from pDNSP-rF16-Cys, resulting in pDNSP-rFBN1-Cys. The inactivation mutation of the RGD site in fibrillin-1 was achieved using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit with the plasmid pBS-rF6 as a template and primer pairs 5′-CGACCTCGAGGAGCCAATGGAGATACAGCCTGC-3′ and 5′-GCAGGCTGTATCTCCATTGGCTCCTCGAGGTCG-3′, introducing a c.4628A>C point mutation in fibrillin-1, resulting in a Asp1543 to Ala exchange in the RGD motif. The plasmid pDNSP-rFBN1-RGA (14,165 bp) was generated by ligating the 4,290 bp ApaI × PmlI fragment from pBS-rF6-RGA with the 9,875 bp ApaI × PmlI fragment from pDNSP-rF16. All plasmids and point mutations were verified by commercial DNA sequencing analysis (McGill University and Génome Québec Innovation Centre).

Cell lines and cell culture conditions

The human embryonic kidney cell line HEK 293, the mouse fibroblast cell line NIH 3T3, and the mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. Human dermal fibroblasts were derived from foreskin explants obtained from circumcisions of 3–10 years old individuals. Informed consent was obtained from the parents prior to the procedure which was approved by the Montreal Children’s Hospital Research Ethics Board (PED-06-054). Fibronectin knock-out and heterozygous MEFs were a gift from Dr. Deane Mosher and described previously.62,63 Fibrillin-1 knock-out MEFs were derived from fibrillin-1 knock-out mice (mgN/mgN).64 Cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium including 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM glutamine (DMEM, Wisent) in the presence of 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a humidified incubator under a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Generation and selection of stable protein expressing clones

The generation of stable recombinant cell clones using HEK 293 cells, was performed as described previously for other fibrillin-1 and -2 fragments.9 Briefly, purified plasmid DNA was transfected into HEK 293 cells using CaCl2 and the selection for antibiotic resistant clones derived from single cells was initiated with 750 μg/ml G418 after 3 days. After expanding the clones into 6-well plates (Corning), confluent cell layers were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Wisent) and further grown in the presence of serum-free DMEM. After 2 days, proteins in 1 ml conditioned medium were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid and separated on a 6% polyacrylamide gel under non-reducing conditions. The gels were blotted on a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) using 20 mM sodium borate buffer. After blocking for 1h with 5% non-fat milk in 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 (TBS), blots were incubated with the monoclonal antibodies mAB 201 or mAB F2 (diluted 1:500 in blocking buffer) overnight at 4°C. Blots were then incubated with a secondary horseradish peroxidase coupled goat-anti mouse antibody for 90 min followed by a color reaction with 4-chloronaphthol. Clones for further experiments were selected according to the intensity of the specific band. Polyclonal expression clones were obtained after lipofection. Briefly, 4 μg linearized plasmid DNA was transfected into HEK 293 cells in suspension using 10 μL lipofectamine 2000 and 490 μLOptiMEM (Invitrogen) in the absence of antibiotics in 6-well plates (Corning). The expression clones were then batch-selected with G418 and characterized as described above.

To analyze mRNA expression, total RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) from confluent cell layers in 6-well plates and reverse transcribed into cDNA with Superscript III RT (Invitrogen) using random hexamers. The cDNA was used as a PCR template with the following primer pairs: 5′-TACGACTCACTATAGGGAGACC-3′ and 5′-CAGAGCGTTTTTGTGCTGACAATCCCGCTGAG-3′ to specifically amplify the rFBN1 construct mRNA with a sense primer located in the vector sequence and a fibrillin-1 antisense primer, 5′-ATCATGCGTCGAGGGCGTCTGC-3′ and 5′-CAGAGCGTTTTTGTGCTGACAATCCCGCTGAG-3′ for endogenous human fibrillin-1 mRNA, 5′-GGATGGAAGGAGCTGCAAAG-3′ and 5′-GTTGTCGTCCATCTCGCTGC-3′ for endogenous mouse fibrillin-1 mRNA, 5′-CCGCATCTTCTTTTGCGTCGC-3′ and 5′-GACGGTGCCATGGAATTTGCC-3′ for human GAPDH, and 5′-GAGATTGTTGCCATCAACGACCCC-3′ and 5′-AGCTTCCCGTTCAGCTCTGGG-3′ for mouse GAPDH. The following PCR conditions were used: 94°C for 3 min, 40 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 48°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min, followed by 72°C for 7 min.

Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy

HEK 293 cultures transfected with the rFBN1-FL, rFBN1-Cys or rFBN1-RGA constructs were either grown in single cultures (75,000 cells/well) or as co-cultures with NIH 3T3 or MEF (37,500 + 37,500 cells/well, or other ratios as indicated). After 3–5 days, cells were washed once with PBS, fixed with ice-cold 70% methanol/30% acetone for 5 min and blocked for 1h with 10% goat serum in PBS (blocking buffer) at room temperature. All subsequent steps were followed by three brief PBS washes. The fixed cells were stained either with a rabbit anti-mouse fibronectin antibody (AB2033, MilliPore, 1:500), mouse anti-human fibronectin antibody (FN clone 15, Sigma, 1:1000), mouse anti-human fibrillin-1 antibodies (mAB F2, mAB 201, 1:500),65 or a rabbit anti-human antibody raised against the rFBN1-C terminal fragment (α-rF6H, synonym: pAB-FBN1-C, 1:500).12 All monoclonal anti-human fibrillin-1 antibodies did not react with mouse fibrillin-1, and HEK 293 cells do not secrete or assemble fibronectin or fibrillin-1. Therefore, this combination of antibodies was suitable to selectively label the mouse fibronectin and human recombinant fibrillin-1. Fibrillin-1 in mouse MEFs was detected with the polyclonal antibody pAB-FBN1-C (1:300) and its specificity was confirmed using the mgN/mgN MEFs. As secondary antibodies, fluorescently labeled goat-anti mouse (1:200) or goat-anti rabbit (1:200) conjugated Alexa-488 (Invitrogen) or Cy3 (Jackson Laboratories) in blocking buffer were incubated with the cells for 1.5h. Nuclei were stained with DAPI for 5 min and the slides were then mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories). Slides were examined with an Axioskop 2 microscope equipped with an Axiocam camera (Zeiss). Pictures were taken with the AxioVision software version 3.1.2.1 (Zeiss). Alternatively, slides were imaged using a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 510 Meta, Zeiss) and analyzed with the LSM viewer software (Zeiss).

To analyze cell surface localization of recombinant fibrillin proteins in HEK 293 cells, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min and after a PBS wash permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. Blocking and antibody staining was performed as outlined above. To analyze potential mechanisms by which the recombinant fibrillin-1 was tethered to the cell surface, monoclonal rFBN1-FL cells were grown as single cultures in the presence of 50 μg/ml rF2,25 100 μg/ml RGDS or RGE peptide, or 500 μg/ml porcine heparin (H3393, Sigma). To analyze the influence of heparin on the formation of the recombinant fibrillin network, MEFs and rFBN1-FL secreting cells were co-cultured in the presence of porcine heparin dissolved in cell culture medium. Cells were fixed and stained as described above.

RESULTS

Development of a modifiable full-length fibrillin-1 assembly assay

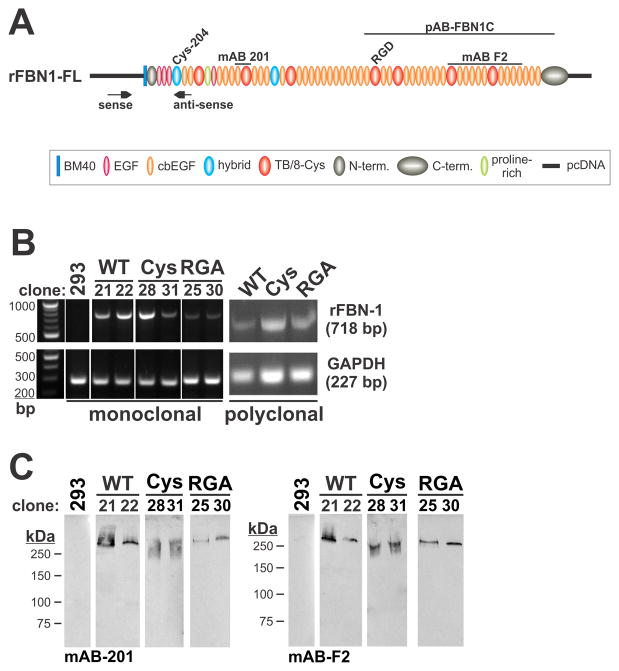

To study early assembly of fibrillin-1 and to analyze consequences of the deletion of functional domains or amino acid residues, we have developed and characterized a recombinant modifiable cell-based system. We generated a recombinant full-length expression vector for human fibrillin-1 (rFBN1-FL) which includes no artificial sequences besides an N-terminal BM-40 signal peptide, which ensures efficient secretion in HEK 293 cells (Fig. 1A).9,25,61,66 This construct differs from a previously generated full length fibrillin-1 construct in that it contains the C-terminal propeptide, which is absent from the previous construct.9 Processing of the C-terminal propeptide has been shown to be critical for fibrillin-1 deposition in the matrix.23,24 To determine whether the unique unpaired cysteine residue at position 204 (Cys204) in the first hybrid domain and the unique integrin-binding RGD sequence, located in the 4th TB domain have a role in early fibrillin-1 assembly, we mutated Cys204 to Ser (rFBN1-Cys) and Asp1543 to Ala (rFBN1-RGA). The latter RGD to RGA mutation was previously introduced in a smaller recombinant fibrillin-1 fragment and shown to disrupt integrin binding.32

Figure 1. Expression of recombinant fibrillin-1 constructs.

A) Schematic representation of the recombinant full length fibrillin-1 (rFBN1-FL) construct. The unpaired cysteine (Cys204) in the first hybrid domain and the integrin binding RGD motive in the TB 4 domain are indicated. Epitopes for polyclonal (pAB-FBN1-C) and monoclonal antibodies (mAB 201, mAB F2) are outlined on top. Arrows show the positions of the PCR primers to selectively detect expression of recombinant rFBN1-FL after transfection of HEK 293 cells. Note that the sense primer is located in the pcDNA vector sequence. B) Gene expression analysis of monoclonal (clone numbers indicated) and polyclonal cell lines stably transfected with rFBN1-FL (WT), rFBN-Cys (Cys) and rFBN1-RGA (RGA) constructs. A specific band of 718 bp that is not detected in non-transfected HEK 293 cells (293) indicates expression of the rFBN1 construct mRNA, albeit at variable levels (left), compared to the expression levels of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). No endogenous fibrillin-1 was expressed (not shown). C) Western blot analysis of the same clones as shown in B (1 ml conditioned medium, trichloroacetic acid-precipitated), using specific monoclonal antibodies with epitopes located in the N-terminal (mAB-201, left panel) and C-terminal (mAB-F2, right panel) half of rFBN1-FL. A single band of about 330 kDa was detected with both antibodies indicating that the recombinant proteins were expressed and secreted.

Initially, we attempted to directly transfect the recombinant full length constructs for rFBN1-FL, rFBN1-Cys, and rFBN1-RGA into mouse fibroblast NIH 3T3 cells which were subsequently batch-selected using G418. We expected that these cells of mesenchymal origin would be able to secrete and assemble recombinant fibrillin-1. However, the expression levels of the recombinant rFBN1 constructs transfected by electroporation or by lipofection were very close to the detection limit in Western blotting or immunofluorescence staining. Therefore, we introduced the recombinant constructs into human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293), known to express and secrete recombinant fibrillin fragments at high levels using expression plasmids harboring the CMV promoter.9,15,67 Both recombinant monoclonal and batch-selected polyclonal cell clones were selected with G418 and tested by RT-PCR for mRNA expression of the constructs (Fig. 1B). Despite some differences in the expression levels, appreciable mRNA expression was readily detectable by RT-PCR for all rFBN1 constructs. Monoclonal and polyclonal cell clones showed similar mRNA expression levels. Endogenous fibrillin-1 mRNA was not expressed by HEK 293 cells (data not shown). Conditioned cell culture media were analyzed by Western blotting to monitor protein expression levels (Fig. 1C). All recombinant constructs were secreted into the culture media and migrated at the expected size of ~330 kDa. In summary, rFBN1-FL, rFBN1-Cys, and rFBN1-RGA were expressed and secreted from transfected HEK 293 cells.

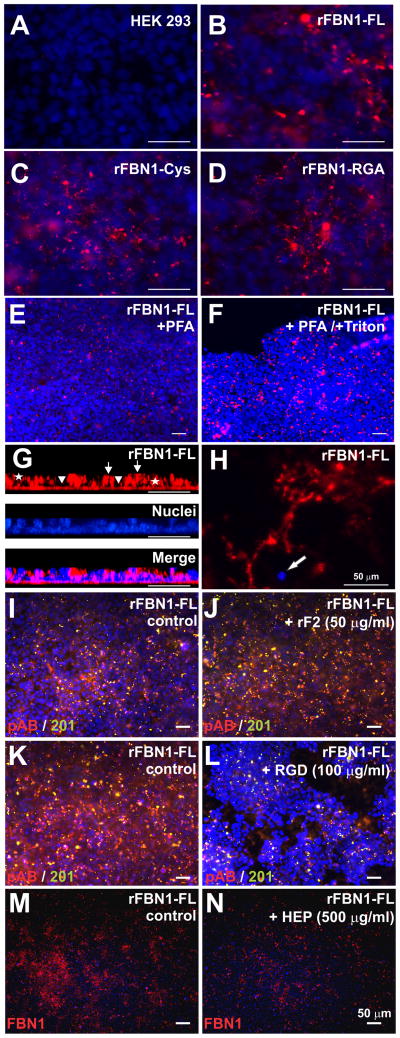

Recombinant fibrillin-1 is deposited in a punctate pattern on HEK 293 cells

Fibrillin-1 immunostaining of rFBN1-FL, rFBN1-Cys, and rFBN1-RGA expressing HEK 293 clones with a polyclonal anti-rFBN1-C antiserum revealed that all recombinant rFBN1 constructs are deposited in a punctate pattern, but did not form extended fibrillin-1 networks typical for mesenchymal cells (Fig. 2B–D). This pattern was absent in non-transfected HEK 293 cells (Fig. 2A), confirming that the punctae in the transfected clones represent the recombinant rFBN1 constructs. A similar staining pattern was observed after indirect immunostaining with the monoclonal antibodies mAB 201 and mAB F2 (data not shown). Whereas cell clones expressing the rFBN1 construct showed this typical deposition pattern, cell clones expressing recombinant N- and the C-terminal halves of fibrillin-1 did not, indicating that both ends of the molecules are required for tethering to cells (data not shown). To determine whether or not the punctae were deposited outside of the cell, we fixed the cells with paraformaldehyde with or without subsequent membrane permeabilization with Triton-X 100 (Fig. 2E, F). A similar staining pattern for rFBN1-FL was observed under both conditions, demonstrating that the recombinant punctae represents deposits outside the cells on the cell surface.

Figure 2. Recombinant fibrillin is deposited in a punctate pattern on the cell surface of HEK 293 cells.

A–D) Non-transfected and polyclonal rFBN1-FL, rFBN1-Cys, and rFBN1-RGA cells were cultured on glass slides and stained for fibrillin-1 with pAB-FBN1-C (red). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). A specific punctate pattern could be detected in transfected cells, but not in non-transfected HEK 293 cells. Constructs in which the unpaired cysteine 204 (rFBN1-Cys) or the RGD site (rFBN1-RGA) was mutated showed a similar deposition pattern compared to rFBN1-FL. E, F) rFBN1-FL expressing HEK 293 cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde (PFA) without (E) or with Triton X-100 (F) to permeabilize cell membranes. Similar punctate deposition patterns of recombinant rFBN1-FL were observed under both conditions, indicating cell surface localization of the deposits. Note that no intracellular accumulation of the recombinant protein was evident. G) Optical cross section after confocal imaging of monoclonal rFBN1-FL cells showed pAB-FBN1-C-positive protein deposited in a thin continuous layer on the glass slide (arrowheads), in between (asterisks), and on top of cells (arrows). H) Area where cells deposited recombinant rFBN1-FL on the surface of the glass slide and migrated or detached. A single remaining nucleus is indicated (arrow). I–N) Monoclonal rFBN1-FL expressing HEK 293 cells were either cultured without (I, K, M, control) or with (J, L, N) the following potential inhibitors at the indicated concentrations: rF2, a recombinant fibrillin-1 fragment encompassing the RGD-containing TB4 domain and two adjacent cbEGF domains (J),25 a synthetic RGD peptide (L), or heparin (N, HEP). None of these compounds at the concentrations used had an effect on the punctate deposits. Note that the synthetic RGD peptide reduced the background staining and punctate deposits are still present. In addition, the peptide strongly interfered with the attachment of the cells to the substratum and caused a contraction of the cell layer into spheres. Scale bars are 50 μm for all images.

To characterize the spatial distribution of fibrillin-1 reactive deposits, we employed confocal microscopy and 3D-reconstruction for rFBN1-FL (Fig. 2G). Most of the reactive fibrillin-1 deposits were localized between the cells within the cell layer. Some material was found deposited below the cells covering the glass slide. Indeed, recombinant fibrillin-1 positive deposits were detectable in some cell-free areas where cells detached during the culture period where cells previously migrated (Fig. 2H).

To address the question which functional entities may tether the recombinant fibrillin-1 deposits onto the cell surface, we tested potential integrin and glycosaminoglycan (proteoglycan) involvement. Addition of a small recombinant fragment harboring the unique RGD-containing TB4 domain and two adjacent cbEGF domains in fibrillin-1 (rF2, 50 μg/ml),25 a synthetic RGD peptide (100 μg/ml), or heparin (500 μg/ml) did not show appreciable alterations to the punctate deposition pattern, indicating that these compounds at the concentrations used could not compete with the formation of the aggregates (Fig. 2I–N). Note that the appearance of the cells after treatment with the RGD peptide was different compared to the control because the RGD peptide caused the cell layer to detach from the substratum resulting in the formation of spheres.

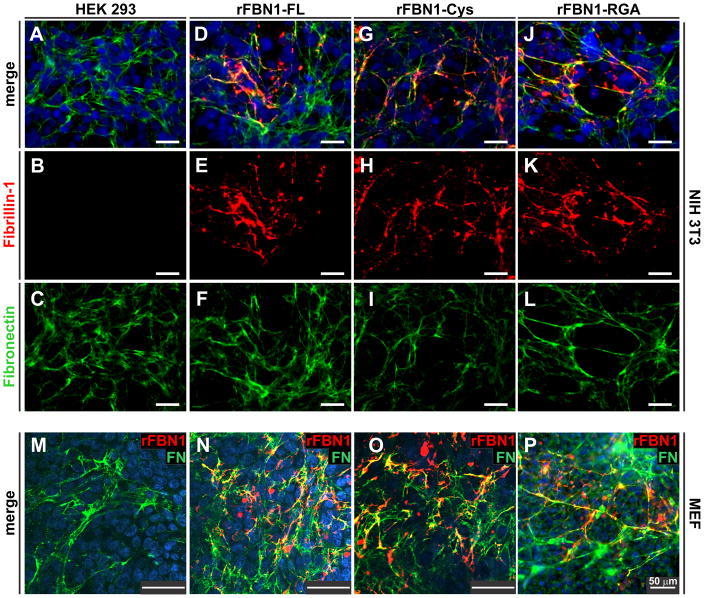

Co-culture of recombinant HEK 293 clones with mesenchymal cells resulted in the formation of a recombinant fibrillin-1 network

As stated above, mesenchymal cells including fibroblasts can assemble fibrillin-1 into a typical network.12,19 Since HEK 293 cells are of epithelial origin, we reasoned that co-culturing with fibroblasts may mediate assembly of the recombinant fibrillin-1 constructs. Therefore, we co-cultured the recombinant HEK 293 cell clones with either mouse NIH 3T3 cells (Fig. 3A–L) or with mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) (Fig. 3M–P). Both cell types produce an extracellular fibronectin scaffold which is one of the essential prerequisites for the formation of a fibrillin-1 network (Fig. 3C, F, I, L, M-P).40,42 The monoclonal antibodies against human fibrillin-1 mAB F2 or mAB 201 do not cross-react with mouse fibrillin-1 in the control co-cultures of non-transfected HEK 293 cells and the respective mesenchymal cells (Fig. 3B, M). Therefore, it is possible to selectively stain the human recombinant fibrillin-1 constructs on the endogenous mouse background. The wild-type rFBN1-FL as well as the mutated constructs rFBN1-Cys and rFBN1-RGA assembled into typical microfibril-like patterns in co-cultures with NIH 3T3 cells (Fig. 3E, H, K). Co-cultures with MEF cells showed a similar deposition pattern indicating that the system is compatible with different mesenchymal cells (Fig. 3N–P). For both cell types, the recombinant fibrillin-1 staining colocalized at many locations with the endogenous fibronectin network.

Figure 3. Co-culture assembly assay of recombinant rFBN1 constructs.

A–L) Polyclonal rFBN1-FL, rFBN1-Cys and rFBN1-RGA cells were co-cultured with NIH 3T3 cells (1:1 ratio). Assembly of recombinant fibrillin-1 was monitored with a monoclonal antibody (red) and co-stained for fibronectin (green). The monoclonal FBN1 antibody did not cross-react with endogenous mouse fibrillin-1 (B). All recombinant rFBN1 proteins assembled into a similar network which partially co-localized with fibronectin. M–P) Co-culture of monoclonal rFBN1-FL, rFBN1-Cys and rFBN1-RGA HEK 293 cells with mouse embryonic fibroblasts, MEF (1:1 ratio). The merged channels (rFBN1, red; FN, green) are shown, demonstrating similar assembly properties of all rFBN1 constructs. Note that the pattern seen in co-culture of the rFBN1 constructs with MEFs appeared more punctate as compared to the more linear deposition pattern observed in co-cultures using NIH 3T3 cells. All bars represent 50 μm.

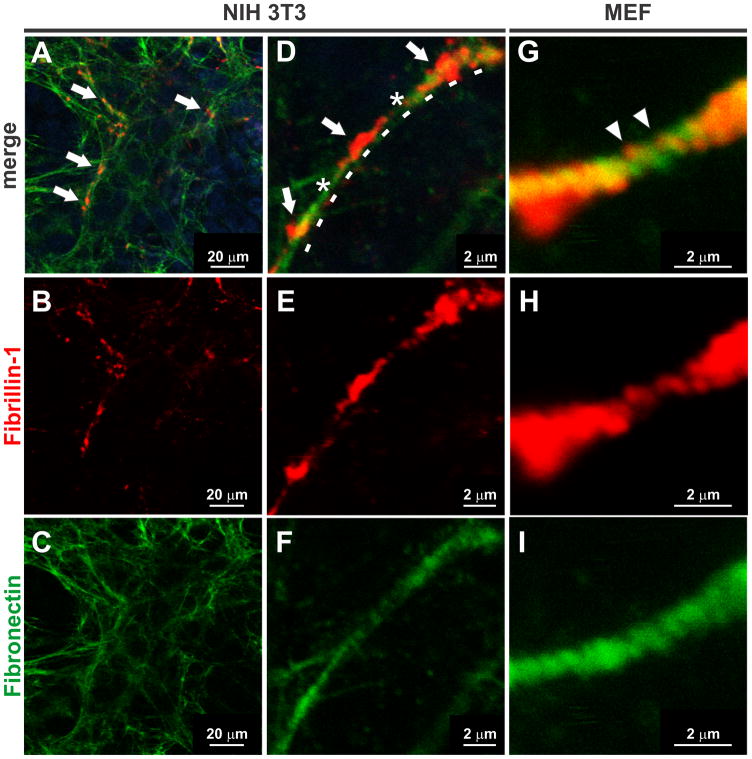

We further analyzed details of early fibronectin-mediated fibrillin-1 assembly in the recombinant co-culture system by confocal microscopy at higher magnifications (Fig. 4). We used a low expression rFBN1-FL clone in combination with NIH 3T3 or MEF cells to analyze initial fibrillin-1 deposition on individual fibronectin fibers. At these early stages, fibrillin-1 deposited as focal punctae on fibronectin fibers, and no continuous fibrillin-1 fiber were observed (Fig. 4A–C, arrows). The recombinant fibrillin-1 in these punctate deposits co-localized with fibronectin in smaller and wider packages but was clearly different from mature continuous microfibrils (Fig. 4D–F, arrows). This indicates that recombinant fibrillin-1 initially deposits as relative discrete packages on fibronectin fibers and then extends laterally to form more mature and continuous microfibrils. In some cases, the fibronectin fibers adopted a corkscrew-like shape and recombinant fibrillin-1 deposits appeared to integrate into the groves of the helix connecting neighboring deposits (Fig. 4G–I, arrowheads). In summary, the three tested constructs rFBN1-FL, rFBN1-Cys, and rFBN1-RGA are assembly-competent in the co-culture system and deposit onto fibronectin fibers. Recombinant fibrillin-1 initially decorates the fibronectin fibers and appears to extend laterally.

Figure 4. Deposition patterns of rFBN1-FL at high resolution.

A–I) A clone with low expression of rFBN1-FL was either co-cultured with NIH 3T3 cells (A–F) or with MEFs (G–I) which allowed for the analysis of early fibrillin-1 deposition on fibronectin fibers before the formation of an extensive network. rFBN1-FL deposits (A, D, arrows) on fibronectin fibers (D, asterisks and dashed line) are punctate, discrete, and partially co-localized. Continuous integration of recombinant rFBN1-FL into a fibronectin fiber (G, arrowheads).

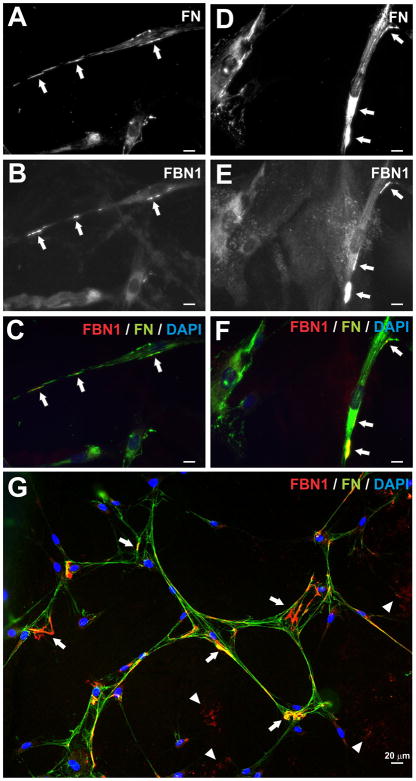

Initial microfibril assembly in human dermal fibroblasts modeled by low cell densities

To compare the results obtained from the recombinant co-culture system with endogenous fibrillin-1 deposition by primary mesenchymal cells, we analyzed human skin fibroblasts at very low densities (Fig. 5A–F). At this stage, fibronectin deposited on the cell surface in streaks and local aggregates (Fig 5A, D, arrows), with fibrillin-1 localizing at isolated distinct regions on some of these aggregates (Fig. 5A–F, arrows). No fibronectin or fibrillin fiber network was observed at this time point. At higher cell densities, extended fibronectin fibers formed between cells with variable length and thickness (Fig. 5G). Here, fibrillin-1 staining was localized in two different forms: i) Most of the fibrillin-1 positive fibers were deposited at this stage focally on the fibronectin fibers (Fig. 5G, arrows); ii) Fibrillin-1 staining was also found cell- and fibronectin-independent, presumably deposited onto the glass surface of the slide (Fig. 5G, arrowheads). In these regions, fibrillin-1 never assumed a fiber-like structure, instead it formed unstructured aggregates. Not all the fibronectin fibers were continuously decorated with fibrillin-1 and the fluorescence intensities for the fibrillin-1 deposits were variable, suggesting that fibrillin-1 was initially deposited in foci along the fibronectin fiber and subsequently extended over time. In summary, the experiments with low density primary fibroblasts show that endogenous fibrillin-1 deposits in discrete packages onto fibronectin fibers close to the cell surface. At later stages, these packages become extended along the fibronectin fiber. This scheme is very similar to the deposition of recombinant fibrillin-1 in the co-culture system.

Figure 5. Punctate pattern of endogenous fibrillin-1 deposited by skin fibroblasts.

Shown is fibronectin (FN) and fibrillin-1 (FBN1) immunostaining of human dermal fibroblasts cultured at low densities. A–F) Typical examples of punctate deposits of endogenous FN (A, D, arrows) and FBN1 (B, E, arrows). FBN1 co-localizes with FN (C, F, arrows). Note that neither FN nor FBN1 networks can be found at such low cell densities. G) Larger field of view with further advanced FN and FBN1 network formation. Similar properties can be observed as in the recombinant single and co-culture experiments: Punctate, discrete deposits of endogenous FBN1 (arrows), partially co-localizing with FN, and non-cell associated FBN1 amorphous deposits on the glass slide surface (arrowheads). Scale bar represents 20 μm for all images.

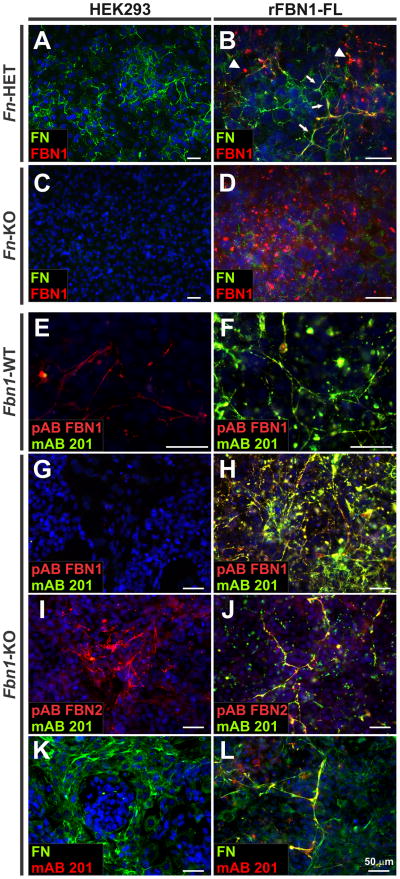

Deposition of rFBN1-FL in co-culture depends on fibronectin but not on endogenous mouse fibrillin-1

We and others have shown previously that the deposition of fibrillin-1 by human dermal fibroblasts is critically dependent on the presence of a fibronectin network in the extracellular matrix.40–42 Hence, we used mouse embryonic fibroblasts derived from fibronectin-null (Fn-KO) and fibronectin heterozygous (Fn-HET) mice,62,63 to analyze the dependency of the recombinant fibrillin-1 deposition in the co-culture system (Fig. 6A–D). The Fn-HET cells produced a sparse, but distinct fibronectin network and, as expected, the Fn-KO cells did not secrete or assemble any fibronectin (Fig. 6A, C). In the co-culture of the Fn-HET cells with the high expressing rFBN1-FL clone, some of the fibronectin fibers were clearly decorated with recombinant fibrillin-1, whereas the punctate pattern of recombinant fibrillin-1 deposition prevailed in regions void of fibronectin fibers (Fig. 6B). This indicates that fibrillin-1 was deposited on fibronectin fibers in relatively close vicinity to the producing cells. In co-cultures with Fn-KO cells, recombinant fibrillin-1 did not form fibers and was exclusively present in punctate patterns identical to the single recombinant HEK 293 clones (Fig. 6D vs. Fig. 2B–D). These data show that recombinant fibrillin-1 deposition is dependent on the presence of fibronectin, similar to what was shown for native fibrillin-1.

Figure 6. Recombinant rFBN1-FL assembly depends on a fibronectin network, but not on nascent fibrillin-1 fibers.

A–D) Monoclonal rFBN1-FL HEK 293 cells were co-cultured with heterozygous Fn-HET (A, B) or homozygous Fn-KO (C, D) MEFs. In the absence of FN (D), rFBN1-FL is deposited in a punctate pattern as observed in single cultures (see Figure 2B) but does not form fibers. rFBN1-FL was co-aligned with FN fibers produced by Fn-HET cells (B, arrows). Some rFBN1-FL punctae were observed in the Fn-HET co-culture (B, arrowheads) due to the lower FN network density. E–L) Monoclonal rFBN1-FL cells were co-cultured with Fbn1-WT (E,F) or Fbn1-KO MEFs (G–L) and co-stained with polyclonal antibodies for endogenous FBN1, FBN2, or FN and for recombinant rFBN1-FL (mAB 201). In the absence of endogenous FBN1 (G–L), recombinant rFBN1-FL protein assembled into fibers, which co-stained with endogenous FBN2 (J) and FN (L). Scale bars are 50 μm for all images.

To exclude the possibility that recombinant fibrillin-1 is associated with the nascent mouse fibrillin-1 network rather than being fully assembly-competent, we co-cultured the recombinant HEK 293 cells expressing the rFBN1-FL construct with fibrillin-1 knock-out MEFs (Fbn1-KO) and compared this to wild-type controls (Fig. 6E–L). The polyclonal anti-rFBN1-C antiserum stains endogenous mouse fibrillin-1 fibers, which are absent in Fbn1-KO cells, indicating the specificity of the antibody (Fig. 6E, G). Recombinant fibrillin-1 was clearly deposited in fibrous structures in the absence of endogenous fibrillin-1 and these structures colocalized with fibronectin (Fig. 6H, L). In these images, the polyclonal antiserum stains endogenous and recombinant rFBN1-FL, whereas mAB 201 is specific for the recombinant fibrillin-1 (Fig. 6E, F). The recombinant fibrillin-1 microfibrils were also shown to colocalize with endogenous fibrillin-2, which may be explained by the colocalization of fibrillin-2 with fibronectin (Fig. 6I, J).68 In summary, the deposition of recombinant fibrillin-1 does not require endogenous fibrillin-1, but does require the presence of a fibronectin network. This validates our recombinant cell culture system as a modifiable tool to study fibrillin assembly.

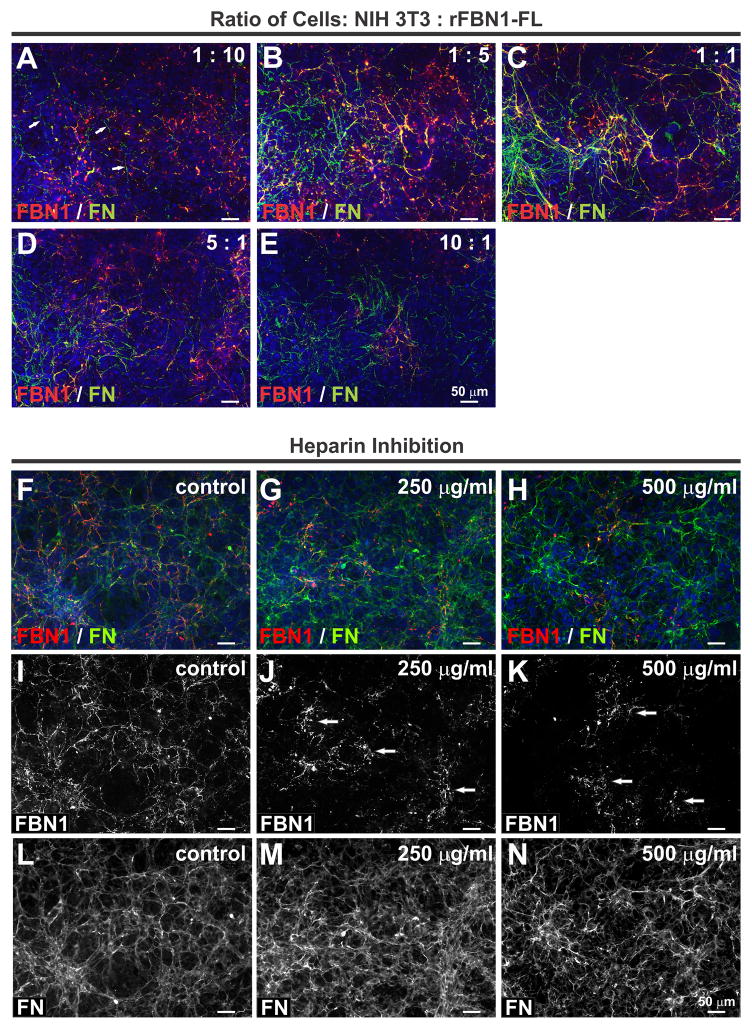

Recombinant fibrillin-deposition is concentration-dependent and can be inhibited by heparin

We tested the cell concentration dependency in the co-culture system and challenged it with heparin, a known inhibitor of fibrillin assembly by human dermal fibroblasts.12 To test the cell concentration dependency for the assembly of recombinant fibrillin-1, we used different ratios of NIH 3T3 and the rFBN1-FL transfected HEK 293 ranging from 1:10 to 10:1 (Fig. 7A–E). At a 1:10 ratio, there were not enough mouse cells to form an extensive fibronectin network and very view fibronectin fibers were visible (Fig. 7A, arrows). Consequently, recombinant fibrillin-1 was predominantly present in a punctate pattern. The optimal ratios for recombinant fibrillin-1 network formation were between 1:5 and 1:1 (Fig. 7B, C). At higher ratios, not enough recombinant fibrillin-1 was produced to form an extensive network (Fig. 7D, E).

Figure 7. Characteristics of the rFBN1-FL assembly system.

A–E) Monoclonal rFBN1-FL HEK 293 cells were co-cultured with NIH 3T3 cells at the indicated ratios. With an excess of rFBN1-FL expressing cells (A), the punctate pattern shown for the single culture dominated and only few FN fibers were observed (A, arrows). In contrast, an excess of NIH 3T3 cells showed mainly FN fibers, and very few punctate deposits (E). The ratio which enabled optimal rFBN1-FL assembly was between 1:5 (B) and 1:1 (C). F–K) Monoclonal rFBN1-FL HEK 293 cells were co-cultured with NIH 3T3 in the presence of indicated concentrations of heparin. Note that rFBN1-FL assembly (F, I) was abolished in the presence of increasing concentrations of heparin (G, J, H, K). Arrows in J and K indicate punctate deposits after heparin inhibition. The fibronectin network (FN) was not affected (L,M,N). Scale bars are 50 μm for all images.

Since it was described that heparin can inhibit the formation of a fibrillin-1 network deposited by human dermal fibroblasts,12 we tested if heparin had inhibitory effects on the recombinant fibrillin-1 deposition in this co-culture system (Fig. 7F–K). Addition of up to 500 μg/ml heparin inhibited the recombinant fibrillin-1 network formation dose-dependently resulting in punctate fibrillin-1 deposits as described for single rFBN1-FL HEK 293 cultures (Fig. 7J, K, arrows). The fibronectin network was not affected (Fig. 7L–M). The concentration of heparin needed for efficient inhibition was in the range shown to inhibit endogenous fibrillin-1 network formation by human dermal fibroblasts.12

DISCUSSION

The initial steps in fibrillin-1 deposition and assembly are not entirely resolved on a mechanistic level, including the function of key domains and residues within fibrillin-1, the role of accessory components of the assembly machinery, and the contribution of the cells in the formation of the microfibril network. In the present study, we describe the development and validation of a modifiable recombinant co-culture system to study initial steps in fibrillin-1 microfibril assembly. This system can also be used to analyze disease causing mutations, to screen small molecules with the potential to reduce or promote fibrillin assembly, and to develop microfibril based extracellular matrices for tissue engineering approaches.

Direct transfection of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (NIH 3T3) with the recombinant full length fibrillin-1 (rFBN1-FL) resulted in very low expression levels, insufficient to produce significant amounts of extracellular fibrillin-1-containing microfibrils. This finding correlates with a previous report demonstrating that a full length fibrillin-1 expression construct was expressed at very low levels in the human fibroblast line MSU1.1.69 However, when rFBN1-FL was expressed by human epithelial kidney cells (HEK 293), known for high expression levels of recombinant extracellular proteins, and cultivated together with fibroblasts, robust recombinant fibrillin-1 network formation was observed. This result indicates that mesenchymal fibroblasts express the accessory proteins or factors that can mediate recombinant fibrillin-1 assembly. This finding complements our previous study, demonstrating that small recombinant fibrillin-1 fragments expressed by HEK 293 cells can inhibit endogenous fibrillin-1 assembly by co-cultured fibroblasts.70

It has been shown that the assembly of fibrillin-1 by fibroblasts and other mesenchymal cells is strictly dependent on the presence of a fibronectin network.40–42 We have shown in the present study that HEK 293 cells do not form a fibronectin network, and that the fibronectin network deposited by fibroblasts triggered assembly of the recombinant full length fibrillin-1 produced by HEK 293 cells. With this co-culture system, we found that i) recombinant fibrillin-1 is deposited in a punctate pattern on the cell surface of HEK 293 cells; ii) the recombinant fibrillin-1 is initially deposited in a non-continuous, focused fashion on the fibronectin network formed by the co-cultured fibroblasts and is then laterally extended; iii) the deposition is independent of endogenous fibrillin-1; and iv) the mutation of Cys204 or the integrin binding site RGD has no effect on the deposition of recombinant fibrillin-1 in this co-culture system.

The assembly of fibrillin is cell-type dependent.21,22 For example human dermal fibroblasts form an extensive network of fibrillin fibers after 3–4 days in culture.12 In contrast, epithelial cells typically do not assemble fibrillin-1 but rather deposit a punctate pattern of fibrillin on the cell surface.21 Such patterns strongly resemble the punctate pattern observed in the present study for the recombinant fibrillin-1 construct secreted by HEK 293 cells. Co-culture of epithelial cells (amniotic epithelial WISH cells) with fibroblasts promoted fibrillin-1 fibril formation,21 similar to the recombinant co-culture system in the present study. However, Dzamba et al. did not analyze for the presence of fibronectin, which was found much later to be required for the deposition of a proper fibrillin-1 network.40,42 Our results using the co-culture system indicate that the fibronectin network provided by the mouse cells enables the deposition of fibrillin-1 on these fibers. Using Fn-KO MEFs, no recombinant fibrillin-1 deposition occurred and the recombinant fibrillin-1 remained cell surface associated with the HEK 293 cells in a punctate pattern. The positioning and accumulation of fibrillin-1 protein at the cell surface may represent one of the initial steps in fibrillin-1 assembly and the biogenesis of microfibrils. HEK 293 cells cannot assemble fibrillin-1, since they do not assemble fibronectin, presumably due to the lack of the specific repertoire of cell surface receptors required for fibronectin assembly. We observed in the present study that punctate fibrillin-1 deposits are also observed in low density fibroblast cell cultures (fibroblasts alone without epithelial cells), indicating that these deposits potentially represent very early fibrillin-1 assemblies. This finding correlates with our previous study showing that fibrillin aggregates, resembling single globules in a microfibril, assemble on the cell surface.27 In the co-culture system providing the required fibronectin network, the punctate deposits are typically much reduced in favor of extended fibrillin fibers, providing further evidence that the punctate deposits are early precursors of fibrillin-1 assembly. The fact that human recombinant fibrillin-1 can assemble on a mouse fibronectin network was expected given the high homology between human and mouse fibronectin (>95% on amino acid level). In addition, it was shown that human fibrillin-1, transgenically expressed in mouse, can be incorporated into mouse microfibrils.71 Heparin (up to 500 μg/ml) and RGD-containing peptides could not inhibit the cell surface tethering of non-assembled globules. We conclude that the globules are either bound with a very high affinity to heparan sulfate containing proteoglycans or to RGD-dependent integrins or, alternatively, that other mechanisms are involved in the surface localization of recombinant fibrillin. This may include binding to the protein core of proteoglycans, or to a RGD-independent integrin.

One of the questions arising from the present study is, what mediates the transfer of the punctate material onto the fibronectin fibers? A possibility is that there are presently undefined accessory molecules involved, which may chaperone fibrillin packages onto a fibronectin fiber. We showed here that only some fibronectin fibers and only some regions of individual fibers are decorated with recombinant fibrillin-1. This indicates that the recombinant protein is not secreted first into the medium and then evenly deposited onto fibronectin fibers but rather relayed directly from the cell surface to the fibronectin fiber through a specific mechanism. Another possibility is that direct contact of fibronectin fibers to the fibrillin deposits is required and wherever fibronectin fibers are close enough fibrillin packages can be transferred. On the other hand, previous reports showed experimental evidence that conditioned medium containing fibrillin-1 can be transferred to other cells to induce fibrillin-1 assembly.21,42 However, it is not clear in this approach which additional set of proteins and factors, potentially mediating fibrillin-1 assembly, are transferred in the conditioned medium from one cell type to the other. Another possible mechanism could involve, in analogy to the deposition of tropoelastin onto nascent elastic fibers,72 cell movement for the delivery of recombinant fibrillin to the fibronectin fibers. We show in the present study high magnification images, which demonstrate that recombinant fibrillin-1 deposits on the surface of a fibronectin fiber in some cases can even wrap around the fibronectin fiber. Once fibrillin-1 is deposited on a fibronectin fiber, it appears that this fibronectin fiber is the preferred target for subsequent depositions extending nascent microfibrils. This could be explained by the substantial avidity increase for N-to-C-terminal fibrillin homotypic interactions following fibrillin-1 multimerization into globules via their C-terminal regions.27 Alternatively, or additionally, initial deposition of fibrillin-1 may render a certain fibronectin fiber competent for future deposits, potentially through conformational changes.

We have previously shown with chick aorta organ cultures that intermolecular disulfide bonds are formed very early to cross-link fibrillin molecules between themselves or to other molecules.28 In the same study, we provided evidence that the unpaired cysteine at position 204 in the first hybrid domain of fibrillin-1 is solvent accessible, which was confirmed by high resolution structural analyses.29 However, the present study clearly indicates that the mutation of the unpaired cysteine 204 neither affects the punctate deposition pattern of the recombinant fibrillin-1 on the HEK 293 cell surface nor abolishes the deposition of fibrillin-1 fibers onto a pre-existing fibronectin network. These findings are in agreement with the deletion of the entire first hybrid domain in a mouse model, which did not affect the formation of microfibrils.30 Since all the other cysteine residues in fibrillin-1 are predicted to be paired in intramolecular disulfide bonds, the question arises, which of the disulfide bonds are engaged in the formation of the early fibrillin-1 cross links observed in the chick organ system?28 We have shown that the recombinant fibrillin-1 C-terminal half multimerizes via its C-terminal region by covalent disulfide bonding, and that human dermal fibroblasts secrete reducible multimerized full-length fibrillin-1.27 As mentioned above, this multimerization is a necessary prerequisite for efficient N-to-C-terminal fibrillin-1 self-interaction. This suggests that the fibrillin-1 multimers observed in the previous study with chick organ cultures are mediated by disulfide-bond exchanges in the C-terminal region of fibrillin-1, and not via the unpaired cysteine 204 in the first hybrid domain.

Interaction of cells with fibrillin-1 via the integrins αvβ3, α5β1, αvβ6, and α8β1 was described using a variety of recombinant fragments.31,33,34,36,37 In addition, a heparin binding synergy region upstream of the RGD site was found to be involved in integrin binding and focal adhesion formation.32 In the present study, we have shown that a RGD to RGA mutation in recombinant full length fibrillin-1 can deposit in a punctate pattern in single HEK 293 cultures and can form a microfibril network on fibronectin in the co-culture system, very similar to the properties of the wild type recombinant fibrillin-1. This finding correlates with a recent report demonstrating that fibrillin-1 harboring a RGD to RGE mutation in a mouse model for stiff skin syndrome deposited excessive microfibrils in the skin that lost contacts with cells.39

As an outlook to further develop the current system for future tissue engineering approaches, it may be possible to co-express recombinant fibrillin together with fibronectin and tropoelastin in HEK 293 cells and co-culture these cells with primary aortic smooth muscle cells. Alternatively, the production of individual stable HEK 293 cell lines expressing recombinant fibronectin or tropoelastin could provide the co-cultures system with flexibility in adjusting the amounts of individual components. Such recombinant cell systems could then be used for the generation of extracellular microfibrils and elastic fibers in nano-structured vascular grafts in a bioreactor.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we developed a modifiable recombinant cell culture system to study the initial deposition of fibrillin-1 on fibronectin, and to provide a tool to analyze the contributions of specific amino acid residues, domains or regions of fibrillin-1 to the formation of microfibrils. This model system can also be used to study disease-causing mutations in fibrillins, such as mutations leading to Marfan syndrome, stiff skin syndrome, dominant Weill-Marchesani and others. In addition, the system can be used to produce microfibril containing matrices for applications in tissue engineering. The experimental model system could be expanded in the future using other microfibril and elastic fiber associated molecules in triple or quadruple cultures and could be valuable in gaining mechanistic insights in the interplay of extracellular matrix molecules during the formation of microfibrils and elastic fibers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Daliang Chen and Matthias Brandenburg for the generation of the RGA mutation in the pBS-rF6 vector. We are grateful to Dr. Dean Mosher and Dr. Douglas Annis for providing the Fn-null and Fn-HET mouse embryonic fibroblasts. We thank Dr. Francesco Ramirez, Lauren W. Wang and Dr. Suneel Apte for providing fibrillin-1 null mgN/mgN fibroblasts. We thank Dr. Simon Foulcer for critical suggestions to improve the clarity and readability of the manuscript.

Abbreviations used

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- cbEGF

calcium-binding epidermal growth factor like domain

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HEK 293

human embryonic kidney cells

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- rFBN1-FL

recombinant full length fibrillin-1

- TB

TGF-β binding protein-like domain

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor beta

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

References

- 1.Low FN. Microfibrils: fine filamentous components of the tissue space. Anat Rec. 1962;142:131–137. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091420205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hubmacher D, Tiedemann K, Reinhardt DP. Fibrillins: From biogenesis of microfibrils to signaling functions. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2006;75:93–123. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)75004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neptune ER, Frischmeyer PA, Arking DE, Myers L, Bunton TE, Gayraud B, Ramirez F, Sakai LY, Dietz HC. Dysregulation of TGF-beta activation contributes to pathogenesis in Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:407–411. doi: 10.1038/ng1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sengle G, Charbonneau NL, Ono RN, Sasaki T, Alvarez J, Keene DR, Bachinger HP, Sakai LY. Targeting of bone morphogenetic protein growth factor complexes to fibrillin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13874–13888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707820200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang H, Apfelroth SD, Hu W, Davis EC, Sanguineti C, Bonadio J, Mecham RP, Ramirez F. Structure and expression of fibrillin-2, a novel microfibrillar component preferentially located in elastic matrices. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:855–863. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.5.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pereira L, D’Alessio M, Ramirez F, Lynch JR, Sykes B, Pangilinan T, Bonadio J. Genomic organization of the sequence coding for fibrillin, the defective gene product in Marfan syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:961–968. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.7.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagase T, Nakayama M, Nakajima D, Kikuno R, Ohara O. Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. XXII. The complete sequences of 100 new cDNA clones from brain which code for large proteins in vitro. DNA Res. 2001;8:85–95. doi: 10.1093/dnares/8.2.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corson GM, Chalberg SC, Dietz HC, Charbonneau NL, Sakai LY. Fibrillin binds calcium and is coded by cDNAs that reveal a multidomain structure and alternatively spliced exons at the 5’ end. Genomics. 1993;17:476–484. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin G, Tiedemann K, Vollbrandt T, Peters H, Bätge B, Brinckmann J, Reinhardt DP. Homo- and heterotypic fibrillin-1 and -2 interactions constitute the basis for the assembly of microfibrils. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50795–50804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210611200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reinhardt DP, Ono RN, Sakai LY. Calcium stabilizes fibrillin-1 against proteolytic degradation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1231–1236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reinhardt DP, Sasaki T, Dzamba BJ, Keene DR, Chu ML, Göhring W, Timpl R, Sakai LY. Fibrillin-1 and fibulin-2 interact and are colocalized in some tissues. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19489–19496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tiedemann K, Bätge B, Müller PK, Reinhardt DP. Interactions of fibrillin-1 with heparin/heparan sulfate: Implications for microfibrillar assembly. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36035–36042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104985200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cain SA, Baldock C, Gallagher J, Morgan A, Bax DV, Weiss AS, Shuttleworth CA, Kielty CM. Fibrillin-1 interactions with heparin: Implications for microfibril and elastic fibre assembly. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30526–30537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reinhardt DP, Mechling DE, Boswell BA, Keene DR, Sakai LY, Bächinger HP. Calcium determines the shape of fibrillin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7368–7373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marson A, Rock MJ, Cain SA, Freeman LJ, Morgan A, Mellody K, Shuttleworth CA, Baldock C, Kielty CM. Homotypic fibrillin-1 interactions in microfibril assembly. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5013–5021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Downing AK, Knott V, Werner JM, Cardy CM, Campbell ID, Handford PA. Solution structure of a pair of calcium-binding epidermal growth factor-like domains: implications for the Marfan syndrome and other genetic disorders. Cell. 1996;85:597–605. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Werner JM, Knott V, Handford PA, Campbell ID, Downing AK. Backbone dynamics of a cbEGF domain pair in the presence of calcium. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:1065–1078. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hubmacher D, Sabatier L, Annis DS, Mosher DF, Reinhardt DP. Homocysteine modifies structural and functional properties of fibronectin and interferes with the fibronectin-fibrillin-1 interaction. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5322–5332. doi: 10.1021/bi200183z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakai LY, Keene DR, Engvall E. Fibrillin, a new 350-kD glycoprotein, is a component of extracellular microfibrils. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:2499–2509. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.6.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldwin AK, Simpson A, Steer R, Cain SA, Kielty CM. Elastic fibres in health and disease. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2013;15:e8. doi: 10.1017/erm.2013.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dzamba BJ, Keene DR, Isogai Z, Charbonneau NL, Karaman-Jurukovska N, Simon M, Sakai LY. Assembly of epithelial cell fibrillins. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1612–1620. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldwin AK, Cain SA, Lennon R, Godwin A, Merry CL, Kielty CM. Epithelial-mesenchymal status influences how cells deposit fibrillin microfibrils. J Cell Sci. 2013;127:158–171. doi: 10.1242/jcs.134270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milewicz D, Pyeritz RE, Crawford ES, Byers PH. Marfan syndrome: defective synthesis, secretion, and extracellular matrix formation of fibrillin by cultured dermal fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:79–86. doi: 10.1172/JCI115589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milewicz DM, Grossfield J, Cao SN, Kielty C, Covitz W, Jewett T. A mutation in FBN1 disrupts profibrillin processing and results in isolated skeletal features of the Marfan syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2373–2378. doi: 10.1172/JCI117930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reinhardt DP, Keene DR, Corson GM, Pöschl E, Bächinger HP, Gambee JE, Sakai LY. Fibrillin 1: organization in microfibrils and structural properties. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:104–116. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baldock C, Koster AJ, Ziese U, Rock MJ, Sherratt MJ, Kadler KE, Shuttleworth CA, Kielty CM. The supramolecular organization of fibrillin-rich microfibrils. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:1045–1056. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.5.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hubmacher D, El-Hallous E, Nelea V, Kaartinen MT, Lee ER, Reinhardt DP. Biogenesis of extracellular microfibrils-Multimerization of the fibrillin-1 C-terminus into bead-like structures enables self-assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6548–6553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706335105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reinhardt DP, Gambee JE, Ono RN, Bächinger HP, Sakai LY. Initial steps in assembly of microfibrils. Formation of disulfide-cross-linked multimers containing fibrillin-1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2205–2210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen SA, Iqbal S, Lowe ED, Redfield C, Handford PA. Structure and interdomain interactions of a hybrid domain: a disulphide-rich module of the fibrillin/LTBP superfamily of matrix proteins. Structure. 2009;17:759–768. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Charbonneau NL, Carlson EJ, Tufa S, Sengle G, Manalo EC, Carlberg VM, Ramirez F, Keene DR, Sakai LY. In vivo studies of mutant fibrillin-1 microfibrils. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:24943–24955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.130021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bax DV, Bernard SE, Lomas A, Morgan A, Humphries J, Shuttleworth A, Humphries MJ, Kielty CM. Cell adhesion to fibrillin-1 molecules and microfibrils is mediated by alpha5 beta1 and alphav beta3 integrins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34605–34616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303159200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bax DV, Mahalingam Y, Cain S, Mellody K, Freeman L, Younger K, Shuttleworth CA, Humphries MJ, Couchman JR, Kielty CM. Cell adhesion to fibrillin-1: identification of an Arg-Gly-Asp-dependent synergy region and a heparin-binding site that regulates focal adhesion formation. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1383–1392. doi: 10.1242/jcs.003954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfaff M, Reinhardt DP, Sakai LY, Timpl R. Cell adhesion and integrin binding to recombinant human fibrillin-1. FEBS Lett. 1996;384:247–250. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakamoto H, Broekelmann T, Cheresh DA, Ramirez F, Rosenbloom J, Mecham RP. Cell-type specific recognition of RGD- and non-RGD-containing cell binding domains in fibrillin-1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4916–4922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee SS, Knott V, Jovanovic J, Harlos K, Grimes JM, Choulier L, Mardon HJ, Stuart DI, Handford PA. Structure of the integrin binding fragment from fibrillin-1 gives new insights into microfibril organization. Structure. 2004;12:717–729. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jovanovic J, Takagi J, Choulier L, Abrescia NG, Stuart DI, van der Merwe PA, Mardon HJ, Handford PA. Alpha v beta 6 is a novel receptor for human fibrillin-1: comparative studies of molecular determinants underlying integrin-RGD affinity and specificity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6743–6751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bouzeghrane F, Reinhardt DP, Reudelhuber T, Thibault G. Enhanced expression of fibrillin-1, a constituent of the myocardial extracellular matrix, in fibrosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H982–H991. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00151.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piha-Gossack A, Sossin WS, Reinhardt DP. The evolution of extracellular fibrillins and their functional domains. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerber EE, Gallo EM, Fontana SC, Davis EC, Wigley FM, Huso DL, Dietz HC. Integrin-modulating therapy prevents fibrosis and autoimmunity in mouse models of scleroderma. Nature. 2013;503:126–130. doi: 10.1038/nature12614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kinsey R, Williamson MR, Chaudhry S, Mellody KT, McGovern A, Takahashi S, Shuttleworth CA, Kielty CM. Fibrillin-1 microfibril deposition is dependent on fibronectin assembly. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2696–2704. doi: 10.1242/jcs.029819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sabatier L, Djokic J, Fagotto-Kaufmann C, Chen M, Annis DS, Mosher DF, Reinhardt DP. Complex contributions of fibronectin to initiation and maturation of microfibrils. Biochem J. 2013;456:283–295. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sabatier L, Chen D, Fagotto-Kaufmann C, Hubmacher D, McKee MD, Annis DS, Mosher DF, Reinhardt DP. Fibrillin assembly requires fibronectin. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:846–858. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-08-0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ritty TM, Broekelmann TJ, Werneck CC, Mecham RP. Fibrillin-1 and -2 contain heparin-binding sites important for matrix deposition and that support cell attachment. Biochem J. 2003;375:425–432. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Faivre L, Gorlin RJ, Wirtz MK, Godfrey M, Dagoneau N, Samples JR, Le MM, Collod-Beroud G, Boileau C, Munnich A, Cormier-Daire V. In frame fibrillin-1 gene deletion in autosomal dominant Weill-Marchesani syndrome. J Med Genet. 2003;40:34–36. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Faivre L, Collod-Beroud G, Callewaert B, Child A, Binquet C, Gautier E, Loeys BL, Arbustini E, Mayer K, Arslan-Kirchner M, Stheneur C, Kiotsekoglou A, Comeglio P, Marziliano N, Wolf JE, Bouchot O, Khau-Van-Kien P, Beroud C, Claustres M, Bonithon-Kopp C, Robinson PN, Ades L, De BJ, Coucke P, Francke U, De PA, Jondeau G, Boileau C. Clinical and mutation-type analysis from an international series of 198 probands with a pathogenic FBN1 exons 24–32 mutation. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:491–501. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Le Goff C, Mahaut C, Wang LW, Allali S, Abhyankar A, Jensen S, Zylberberg L, Collod-Beroud G, Bonnet D, Alanay Y, Brady AF, Cordier MP, Devriendt K, Genevieve D, Kiper PO, Kitoh H, Krakow D, Lynch SA, Le MM, Megarbane A, Mortier G, Odent S, Polak M, Rohrbach M, Sillence D, Stolte-Dijkstra I, Superti-Furga A, Rimoin DL, Topouchian V, Unger S, Zabel B, Bole-Feysot C, Nitschke P, Handford P, Casanova JL, Boileau C, Apte SS, Munnich A, Cormier-Daire V. Mutations in the TGFbeta binding-protein-like domain 5 of FBN1 are responsible for acromicric and geleophysic dysplasias. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dietz HC, Cutting GR, Pyeritz RE, Maslen CL, Sakai LY, Corson GM, Puffenberger EG, Hamosh A, Nanthakumar EJ, Curristin SM, Stetten G, Meyers DA, Francomano CA. Marfan syndrome caused by a recurrent de novo missense mutation in the fibrillin gene. Nature. 1991;352:337–339. doi: 10.1038/352337a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loeys BL, Gerber EE, Riegert-Johnson D, Iqbal S, Whiteman P, McConnell V, Chillakuri CR, Macaya D, Coucke PJ, De Paepe A, Judge DP, Wigley F, Davis EC, Mardon HJ, Handford P, Keene DR, Sakai LY, Dietz HC. Mutations in Fibrillin-1 Cause Congenital Scleroderma: Stiff Skin Syndrome. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:23ra20. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramirez F, Carta L, Lee-Arteaga S, Liu C, Nistala H, Smaldone S. Fibrillin-rich microfibrils - structural and instructive determinants of mammalian development and physiology. Connect Tissue Res. 2008;49:1–6. doi: 10.1080/03008200701820708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aoyama T, Tynan K, Dietz HC, Francke U, Furthmayr H. Missense mutations impair intracellular processing of fibrillin and microfibril assembly in Marfan syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:2135–2140. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.12.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hollister DW, Godfrey M, Sakai LY, Pyeritz RE. Immunohistologic abnormalities of the microfibrillar-fiber system in the Marfan syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:152–159. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007193230303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raghunath M, Superti-Furga A, Godfrey M, Steinmann B. Decreased extracellular deposition of fibrillin and decorin in neonatal Marfan syndrome fibroblasts. Hum Genet. 1993;90:511–515. doi: 10.1007/BF00217450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Godfrey M, Raghunath M, Cisler J, Bevins CL, Depaepe A, Di Rocco M, Gregoritch J, Imaizumi K, Kaplan P, Kuroki Y, Silberbach M, Superti-Furga A, van Thienen MN, Vetter U, Steinmann B. Abnormal morphology of fibrillin microfibrils in fibroblast cultures from patients with neonatal Marfan syndrome. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:1414–1421. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kielty CM, Shuttleworth CA. Abnormal fibrillin assembly by dermal fibroblasts from two patients with Marfan syndrome. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:997–1004. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.6.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kielty CM, Phillips JE, Child AH, Pope FM, Shuttleworth CA. Fibrillin secretion and microfibril assembly by Marfan dermal fibroblasts. Matrix Biol. 1994;14:191–199. doi: 10.1016/0945-053x(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Milewicz DM, Dietz HC, Miller DC. Treatment of aortic disease in patients with Marfan syndrome. Circulation. 2005;111:e150–e157. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155243.70456.F4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hosseinkhani H, Hong PD, Yu DS. Self-assembled proteins and peptides for regenerative medicine. Chem Rev. 2013;113:4837–4861. doi: 10.1021/cr300131h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hosseinkhani H, Hosseinkhani M, Hattori S, Matsuoka R, Kawaguchi N. Micro and nano-scale in vitro 3D culture system for cardiac stem cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;94:1–8. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bashur CA, Venkataraman L, Ramamurthi A. Tissue engineering and regenerative strategies to replicate biocomplexity of vascular elastic matrix assembly. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2012;18:203–217. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2011.0521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jensen SA, Reinhardt DP, Gibson MA, Weiss AS. MAGP-1, Protein interaction studies with tropoelastin and fibrillin-1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39661–39666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.El-Hallous E, Sasaki T, Hubmacher D, Getie M, Tiedemann K, Brinckmann J, Bätge B, Davis EC, Reinhardt DP. Fibrillin-1 interactions with fibulins depend on the first hybrid domain and provide an adapter function to tropoelastin. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8935–8946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608204200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saoncella S, Echtermeyer F, Denhez F, Nowlen JK, Mosher DF, Robinson SD, Hynes RO, Goetinck PF. Syndecan-4 signals cooperatively with integrins in a Rho-dependent manner in the assembly of focal adhesions and actin stress fibers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2805–2810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.George EL, Georges-Labouesse EN, Patel-King RS, Rayburn H, Hynes RO. Defects in mesoderm, neural tube and vascular development in mouse embryos lacking fibronectin. Development. 1993;119:1079–1091. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carta L, Pereira L, Arteaga-Solis E, Lee-Arteaga SY, Lenart B, Starcher B, Merkel CA, Sukoyan M, Kerkis A, Hazeki N, Keene DR, Sakai LY, Ramirez F. Fibrillins 1 and 2 perform partially overlapping functions during aortic development. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8016–8023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511599200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuo CL, Isogai Z, Keene DR, Hazeki N, Ono RN, Sengle G, Bächinger HP, Sakai LY. Effects of fibrillin-1 degradation on microfibril ultrastructure. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4007–4020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hubmacher D, Tiedemann K, Bartels R, Brinckmann J, Vollbrandt T, Bätge B, Notbohm H, Reinhardt DP. Modification of the structure and function of fibrillin-1 by homocysteine suggests a potential pathogenetic mechanism in homocystinuria. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:34946–34955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504748200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kirschner R, Hubmacher D, Iyengar G, Kaur J, Fagotto-Kaufmann C, Brömme D, Bartels R, Reinhardt DP. Classical and neonatal Marfan syndrome mutations in fibrillin-1 cause differential protease susceptibilities and protein function. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32810–32823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.221804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beene LC, Wang LW, Hubmacher D, Keene DR, Reinhardt DP, Mecham RP, Traboulsi EI, Apte SS. Non-selective assembly of fibrillin-1 and fibrillin-2 in the rodent ocular zonule and in cultured cells: Implications for Marfan syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:8337–8344. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kettle S, Card CM, Hutchinson S, Sykes B, Handford PA. Characterisation of fibrillin-1 cDNA clones in a human fibroblast cell line that assembles microfibrils. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2000;32:201–214. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Charbonneau NL, Dzamba BJ, Ono RN, Keene DR, Corson GM, Reinhardt DP, Sakai LY. Fibrillins can co-assemble in fibrils, but fibrillin fibril composition displays cell-specific differences. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2740–2749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Judge DP, Biery NJ, Keene DR, Geubtner J, Myers L, Huso DL, Sakai LY, Dietz HC. Evidence for a critical contribution of haploinsufficiency in the complex pathogenesis of Marfan syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:172–181. doi: 10.1172/JCI20641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Czirok A, Zach J, Kozel BA, Mecham RP, Davis EC, Rongish BJ. Elastic fiber macro-assembly is a hierarchical, cell motion-mediated process. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207:97–106. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]