Abstract

Psychological disorders co-occur often in children, but little has been done to document the types of conjoint pathways internalizing and externalizing symptoms may take from the crucial early period of toddlerhood or how harsh parenting may overlap with early symptom co-development. To examine symptom co-development trajectories, we identified latent classes of individuals based on internalizing and externalizing symptoms across ages 3–9 and found three symptom co-development classes: normative symptoms (low), severe-decreasing symptoms (initially high but rapidly declining) and severe symptoms (high) trajectories. Next, joint models examined how parenting trajectories overlapped with internalizing and externalizing symptom trajectories. These trajectory classes demonstrated that, normatively, harsh parenting increased after toddlerhood, but the severe symptoms class was characterized by a higher level and steeper increase in harsh parenting and the severe-decreasing class by high, stable harsh parenting. Additionally, a transactional model examined the bi-directional relationships among internalizing and externalizing symptoms and harsh parenting as they may cascade over time in this early period. Harsh parenting uniquely contributed to externalizing symptoms, controlling for internalizing symptoms, but not vice versa. Also, internalizing symptoms appeared to be a mechanism by which externalizing symptoms increase. Results highlight the importance accounting for both internalizing and externalizing symptoms from an early age to understand risk for developing psychopathology and the role harsh parenting plays in influencing these trajectories.

Keywords: internalizing, externalizing, trajectories, parenting, conflict tactics

Introduction

Developmentally, toddlerhood marks a major period of risk for children. While undergoing rapid brain development, toddlers go through a period of increased capabilities, including newfound mobility, but without the cognitive abilities to appreciate the consequences of their behavior nor the capabilities to consistently regulate their emotions (Shaw, Bell & Gilliom, 2000). During this developmental period, child behavior can be difficult for parents to manage, as externalizing and internalizing symptoms first emerge and may begin a trajectory towards increased risk for maladaptive behavior across the lifespan. Higher externalizing and internalizing symptoms in early childhood predict a myriad of poor outcomes across childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (e.g., Brennan et al., 2012; Roza et al., 2003). Therefore, understanding the development of early trajectories of externalizing and internalizing symptoms is critical in informing efforts to prevent early-appearing symptoms from developing into entrenched psychopathology (e.g., Dishion et al., 2008). Moreover, as studies show that psychiatric symptoms are highly co-occurring (Krueger & Markon, 2006), particularly in children (Achenbach, 1966; Caron & Rutter, 1991; Wadsworth et al., 2001), understanding the early development of internalizing and externalizing disorders in relation to each other is particularly important for addressing future psychopathology. Finally, just as understanding the trajectory of early internalizing and externalizing symptoms may inform potential prevention trials, so too may a focus on how parenting practices relate to these trajectories. Harsh parenting is quite well-studied as a risk factor for externalizing (e.g., Waller et al., 2012) as well as internalizing (e.g., Callahan et al., 2011) symptoms, and is a target for many early prevention studies (Dishion et al., 2008). Thus, studies that examine the role of harsh parenting in internalizing and externalizing psychopathology co-development may inform parenting-focused early prevention efforts (Callahan et al., 2011; Shaw, 2013).

Beyond the importance of examining the co-development of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in early childhood, a developmental psychopathology approach emphasizes that symptoms at any one point are not as important for predicting outcomes as the trajectory of symptoms over time (e.g., Rueter et al., 1999). Thus, developmental psychopathology researchers have leveraged longitudinal statistical techniques, such as growth mixture models, to examine the trajectories of internalizing and externalizing symptoms across development. Additionally, developmental psychopathology as a field has emphasized the importance of examining development from a person-centered approach. This approach highlights that symptoms over time may vary widely between youth in terms of the shape of their trajectories. By using a subset of growth mixture models, latent class growth analysis, researchers are able to identify more homogenous subgroups of individuals manifesting distinct symptom trajectories. These groups may have different shapes to their trajectories that would not be captured in latent growth curve models, which assume only a single shape (from which individuals vary) for the entire population (Wright & Hallquist, 2013). Thus, trajectory classes in early childhood can help to identify qualitatively different groups of youth who vary in their co-development of internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Thus, the primary goals of this study were, first, to examine the co-development of externalizing and internalizing symptoms over time using parallel process latent class growth analysis and, second, to examine the role harsh parenting plays in the development of these trajectories.

Externalizing Trajectory Groups

There have been a number of studies using trajectory analyses to examine externalizing and related behaviors such as aggression, antisocial behavior, and violence in late childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. Studies focusing on externalizing symptoms have generally identified three to four groups of individuals: a normative class of low externalizing problems, an intermediate class that could increase or decrease, and a severe class. For example, in a community sample of 452 individuals, Latendresse et al (2011) found three classes of individuals based on their externalizing symptom trajectories from age 12–22: a large normative class of low, decreasing externalizing; a smaller class of moderate, decreasing externalizing symptoms; and a small number of individuals with high, stable externalizing symptoms. Silver et al (2010) also found three classes in 241 children from ages 5–11, although, in contrast to Latendresse et al (2011), their intermediate group increased instead of decreased in symptom severity, possibly due to the specific age range covered or the specific composition of their relatively small sample size. Studies focusing on related constructs such as aggression and antisocial behavior, usually on adolescence and adulthood, have found similar numbers and types of groups (e.g., Cote et al., 2006; for a review, see Jennings & Reingle, 2012; Shaw, Hyde & Brennan, 2012; Tremblay et al., 2004). In particular, Broidy et al (2003) found a pattern of three to four trajectory classes of aggression across six samples of school-age children from multiple international sites. Importantly, the majority of studies in this area have started at school-age at the earliest (Broidy et al., 2003; Latendresse et al., 2011; Proctor et al., 2010; Silver et al., 2010).

Externalizing and externalizing-related behavior trajectories have been well studied starting at school-age and later; however, toddlerhood is a crucial period to start identifying types of trajectories of externalizing symptoms. Thus, research is needed examining earlier starting trajectories and a few studies have addressed this need. In particular, the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development found five classes of physical aggression trajectories in 1100 children 2 years old to 3rd grade, including a large normative class of low, decreasing aggression as well as intermediate and severe classes (NICHD, 2004). Also, two studies in the Pitt Mother and Child Project examined early conduct problems (Shaw et al., 2003) and the overlap between conduct problems and ADHD (Shaw, Lacourse & Nagin, 2005), and found four trajectory groups from age 2 to ages 8 and 10, respectively. However, beyond these few studies, less work has focused on this early age period, with little attention to the overlap between internalizing and externalizing psychopathology using trajectory groups (see Gilliom & Shaw, 2004, for an approach with latent growth curve modeling, examining variations from a single normative trajectory). Moreover, with the exception of the study from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care (N=1100), much of this groundbreaking work has been done on one community sample of moderate size (Ns=284 for both Shaw et al (2003) and (2005)), which is enriched for risk, but may not have represented the range of potential developmental paths in a national population, particularly as trajectory group number, size, and shape (e.g., an increasing versus decreasing intermediate class) may be affected by overall sample size and composition.

Internalizing Symptom Trajectory Groups

Compared to externalizing symptoms, there has been less research on trajectory classes of internalizing symptoms in youth. Researchers have examined trajectories of internalizing psychopathology and related constructs, such as anxiety and depression, starting in school-age and have found large normative classes that decreased in internalizing symptoms over time and severe classes that had high levels of internalizing symptoms, almost always with an additional one or two intermediate classes with increasing or decreasing internalizing (1,313 adolescents/young adults ages 10–20, Crocetti et al., 20091,313 adolescents/young adults ages 10–20, Crocetti et al., 2000 children ages 6–12, Duchesne et al., 2010; 565–2,325 girls in an accelerated longitudinal design covering age 5–13, Marmorstein et al., 2010; 279 severely maltreated youth ages 6–14, Proctor et al., 2010; 719 adolescents/adults ages 13–30, Yaroslavsky et al., 2013).

As with externalizing psychopathology, the toddlerhood period is important to examine for internalizing psychopathology, yet only three of the studies on internalizing or internalizing-related symptoms included data from prior to school age in identifying trajectory groups (Broeren et al., 2013; Feng, Shaw & Silk, 2008; Sterba, Prinstein & Cox, 2007). Like the studies on school-age and older children, all three of these toddlerhood studies found a pattern of a large, normative class with decreasing internalizing symptoms and a smaller, severe internalizing symptom class (224 children ages 4–11, Broeren et al., 2013), with two studies also finding one or two intermediate classes in addition to the normative and severe classes (1,364 children ages 2–11, Feng et al., 2008; 290 boys ages 2–10, Sterba et al., 2007). The small number of studies on this developmental period likely reflects the low base rates of internalizing disorders before school age. That said, internalizing disorders can onset very young; for example, the average age of onset of some anxiety disorders is as early as 6 years old (Merikangas et al., 2010). Early individual variability in these symptoms may portend worse outcomes and allow researchers to identify those youth at greatest need for preventive interventions. Examining trajectories starting early in life (e.g., toddlerhood) can help to document the shift from non-disordered to at-risk to disordered status. Additionally, in order to capture the full range of potential developmental paths, it is important to have samples larger than previous studies (e.g., Ns=224 from Broeren et al (2013) and 290 boys from Sterba et al (2007)), with representation from the range of the national population yet also enriched for risk.

The studies reviewed have been helpful to delineate different classes of individuals based on their externalizing or internalizing symptoms. However, identifying classes based on externalizing symptoms independently of internalizing symptoms and vice versa does not take into account that internalizing and externalizing psychopathology may be related, as many youth often exhibit co-occurring externalizing and internalizing symptoms (Gilliom & Shaw, 2004), at a much higher rate than would be expected by chance (Angold, Costello & Erkanli, 1999).

Co-development of Externalizing and Internalizing Symptoms

When examined across the entire population, externalizing behavior, particularly in overt (versus covert) form, typically peaks in toddlerhood then decreases (Kuczynski & Kochanska, 1990; Miner & Clarke-Stewart, 2008), whereas internalizing symptoms typically increase across childhood with a spike in adolescence (Achenbach, Howell, Quay, & Conners, 1991; Tremblay, Boulerice, Harden, McDuff, Perusse, Pihl, & Zoccolillo, 1996). These concurrent patterns may be due to changes in cognitive functioning with age (Miner & Clarke-Stewart, 2008). In particular, normative decreases in externalizing behavior from toddlerhood to middle childhood may be due to improved verbal communicative skills (Tremblay, 2000). Simultaneous increases in internalizing symptoms, on the other hand, may be due to an improved ability to remember and anticipate negative events (Kaslow, Brown, & Mee, 1994; Vasey, Crnic, & Carter, 1994). Another possibility is that emotionally dysregulated toddlers may throw tantrums, but as they experience punishment and negative reactions to their tantrums, children may begin to funnel this dysregulation into anxiety and other internalizing behaviors (Patterson, DeBaryshe & Ramsey, 1989). Thus, the interplay between externalizing and internalizing symptoms as they develop, both normatively and in youth on at-risk trajectories, is important to understand. Examining normatively decreasing externalizing and increasing internalizing behavior, however, does not take into account that some youth may exhibit different trajectory shapes, as has been demonstrated by the numerous trajectory class studies on internalizing and externalizing symptoms (reviewed above).

One way to obtain a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of how symptom domains co-develop, or change concurrently is to examine how the co-development of symptoms may differ across groups of individuals, but few studies have done this. Two studies examined the joint probabilities of being in different combinations of internalizing and externalizing symptom classes. First, Chen and Simon-Morton (2009) found that a large proportion (42%) of boys with the highest levels of depression symptoms across middle school through the first year of high school concurrently experienced the highest levels of conduct problems. Because this study focused on adolescents, however, it was unable to capture changes occurring in the crucial early period of toddlerhood to middle childhood. A second study identified internalizing and externalizing symptom classes, separately, over ages 2–11 and then calculated the joint probability of being in both types of classes (Fanti & Henrich, 2010). Of the 15 possible joint classes (5 externalizing symptom classes x 3 internalizing symptom classes), however, 4 potential combinations of classes had to be discarded because of low probabilities that the individuals assigned to that group actually belonged in that group (Fanti & Henrich, 2010). This method of examining trajectories of externalizing symptoms, regardless of internalizing symptoms, and vice versa, then calculating the joint probabilities, is a fruitful starting place. However, because this method is constrained to combinations of internalizing and externalizing symptom classes that have already been identified in separate models examining a single symptom domain, there is less flexibility to allow groups based on simultaneous examination of internalizing and externalizing symptoms to emerge. In particular, constraining the co-development classes to combinations of internalizing and externalizing symptom classes identified separately runs the risk of identifying non-existent joint classes (as shown in Fanti & Henrich’s (2010) low-probability classes that had to be eliminated) as well as joint classes that inadvertently encompass more than one homogenous subgroup. A more data-driven approach, such as parallel process latent class growth analysis, could allow for greater validity in classifying individuals based on simultaneous consideration of growth factors. Moreover, this technique would be strengthened through its application in much larger datasets that have the power to examine the possible existence of smaller co-occurring groups, particularly in families that may be at more risk for later psychopathology (e.g., via lower income).

Only one study used parallel process latent class growth analysis to examine the co-development of externalizing and internalizing symptoms in a youth sample (Hinnant & El-Sheikh, 2013). This study focused on a later period in childhood, ages 8 to 11. The authors identified three classes based on the co-development of externalizing and internalizing symptoms. The normative, largest class was characterized by low, decreasing internalizing and externalizing symptoms; an intermediate class was characterized by moderate levels of internalizing and low levels of externalizing symptoms; and a severe class was characterized by high, stable levels of internalizing and high, increasing levels of externalizing symptoms (Hinnant & El-Sheikh, 2013). Thus, the primary goal of this paper was to apply this method of identifying trajectory classes based on the co-development of internalizing and externalizing symptoms, but starting in the crucial early period of toddlerhood in a very large, population-based sample.

Harsh Parenting

Understanding the types of paths that the co-development of externalizing and internalizing symptoms can take is important in and of itself. In addition, it is also important to understand how early risk factors may contribute to these trajectories. One of the most potent and well-studied risk factors in childhood is harsh parenting. Harsh parenting, which can include, but is not limited to, physical assault (e.g., hitting) and psychological aggression (e.g., yelling) by the parent or caregiver (e.g., Shaw et al., 2003), plays a major role in the development of psychopathology (for reviews, see Cicchetti & Toth, 1995; McCrory, De Brito & Viding, 2012; Oswald, Heil & Goldbeck, 2010). It is well-established that harsh parenting is associated with worse externalizing behavior in toddlerhood (e.g., age 2, Callahan et al., 2011; age 2–3, Eiden et al., 2013; age 2–4, Waller et al., 2012) as well as older childhood (e.g., ages 9–16, Deardorff et al., 2013). Moreover, harsh parenting has been linked to poor trajectories of externalizing behavior from ages 2 to 8 and 10 (Shaw et al., 2003; Shaw et al., 2005) and may have an effect above and beyond passive gene-environment correlation (in children ages 5–8, Harold et al., 2013). Although significantly fewer papers linked harsh parenting with internalizing compared to externalizing symptoms, there is some support that harsh parenting is related to worse internalizing symptoms in toddlerhood (age 2, Callahan et al., 2011) and middle childhood to adolescence (for a meta analysis of studies with children ages 8–18, see McLeod, Weisz & Wood, 2007). Thus, the second aim of this paper is to identify the ways in which externalizing and internalizing symptoms as well as harsh parenting relate to one another from toddlerhood to middle childhood, in part by classifying individuals based on both child- and parent-level trajectories.

The theoretical mechanism underlying associations between harsh parenting and both externalizing and internalizing psychopathology is thought to start with harsh parenting in toddlerhood, which may undermine attempts to learn self-regulation, leading to further externalizing (Belsky, Pasco Fearon & Bell, 2007) and rejection by peers (Cantrell & Prinz, 1985). This in turn leads to increased risk for internalizing problems (Patterson et al., 1989) Moreover, a cycle of increasingly aversive, harsh parent-child interactions (Smith et al., in press), may further increase externalizing behavior (Patterson et al., 1989). Thus, understanding how harsh parenting changes from the toddlerhood to middle childhood alongside externalizing and internalizing symptoms is important to understand the emergence of these symptom domains.

Other studies directly examining timing and trajectories of harsh parenting suggest that examining harsh parenting trajectories alongside internalizing and externalizing symptom trajectories may be valuable. Specifically, earlier exposure to physical assault (from birth to age 5) was more strongly associated with depression in adults than later exposure (Dunn et al., 2013), indicating that timing of harsh parenting (which would be captured by longitudinal data) is critical for predicting internalizing problems. Also, in a latent class growth analysis of maternal psychological aggression, compared to other trajectory patterns of psychological aggression, high stable patterns of psychological aggression over the middle school years has been linked to higher levels of externalizing (delinquency) as well as internalizing (depression) (Donovan & Brassard, 2011). Moreover, during a period of developmental transition (i.e., the ‘terrible twos’ of toddlerhood versus later in the preschool period or the school-age period), assessments of parenting might be more informative of later child problem behavior than during times of relative stability in children’s physical, emotional, and/or cognitive maturation (e.g., Trentacosta & Shaw, 2008). Taken together, these studies suggest that documenting when and for how long harsh parenting occurs may be important for understanding the development of internalizing and externalizing problems. Thus, understanding the full impact of harsh parenting on psychopathology may require taking into account changes in harsh parenting over time via the trajectories. Moreover, because both harsh parenting and internalizing and externalizing problems are moving targets, changing and bi-directionally influencing one another over time, modeling their joint trajectories may give a fuller picture of these dynamic processes than considering harsh parenting at any one time point.

Our second aim, to identify the ways in which externalizing and internalizing symptoms as well as harsh parenting relate to one another from toddlerhood to middle childhood, can be accomplished in part by classifying individuals based on both child- and parent-level trajectories. However, although an advantage of the trajectory approach is that it documents person-centered changes in levels of harsh parenting and symptoms (Wright & Hallquist, 2013), a weakness is that this approach does not account for the bidirectional, transactional nature of harsh parenting and externalizing and internalizing symptoms (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010; Sameroff, 2010). Several studies provide evidence that not only does harsh parenting influence symptoms, child externalizing and internalizing symptoms may also increase harsh parenting in the toddlerhood to middle childhood period. For example, Scaramella et al (2008) found that harsh parenting at age 2 increased externalizing behavior at age 3, which in turn increased harsh parenting at age 4. Next, Lansford et al (2009) demonstrated that children who display higher levels of externalizing behavior at age 5 were more likely to have high, stable trajectories of harsh parenting from ages 6–15. In addition, Gross et al (2008) found that child externalizing symptoms at age 2 increased parental depression, which in turn increased internalizing symptoms at age 4. Moreover, a study that examined cascading effects among internalizing and externalizing problems and another aspect of child wellbeing, academic competence, found a transactional relationship among these constructs: not only did externalizing problems influence internalizing and academic problems through early to middle childhood, academic competence also affected internalizing and externalizing problems (Moilanen, Shaw & Maxwell, 2010). A similar interplay may exist between externalizing and internalizing problems and harsh parenting as with parental depression or academic competence. Although there is evidence that harsh parenting may be involved in the development of externalizing and internalizing psychopathology separately, it currently unknown how harsh parenting may contribute to the development of externalizing symptoms in the context of internalizing symptoms and vice versa, or the extent to which the relationships among all three – internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and harsh parenting – are transactional. Thus, an additional, complementary approach to accomplish our second goal, identifying the ways in which externalizing and internalizing symptoms as well as harsh parenting relate to one another from toddlerhood to middle childhood, is to characterize the reciprocal contributions of externalizing and internalizing symptoms and harsh parenting to each other over time.

The Present Study

Overall, the research reviewed on externalizing and internalizing symptoms shows that these symptom domains likely follow low, intermediate, and severe paths in middle childhood to adolescence. However, few studies examined these trajectories before school age (though with some notable exceptions, many of which come from the same low-income sample, e.g., Shaw et al., 2003), particularly with regard to how externalizing and internalizing symptom trajectories may co-develop. The studies that have traced developmental trajectories for externalizing and internalizing problems separately used small to moderately sized samples, which decreases the ability to sensitively and accurately identify trajectories. Samples sizes in previous studies, which have been as low as in the few hundreds, could lead to very small Ns in groups, particularly when examining joint trajectories. Moreover, much of this work has been done on local community-based samples, which may influence the number and shape of the trajectories that the study is able to identify. Thus, in order to accurately identify trajectories, it is necessary to have a large, population-based sample, which would include representation of the range of developmental paths. In addition, it is important to have a sample enriched for risk in order to capture the most severe classes and transitions from typical to atypical behavior.

The research reviewed showed that harsh parenting is highly related to child behavior problems. However, harsh parenting’s relationship to the co-development of internalizing and externalizing symptoms has been understudied in the toddlerhood period, particularly in larger samples that can test for the possibility of smaller trajectory groups. Finally, though the primary goal of the manuscript is to characterize trajectories of symptoms, studies of transactional models emphasize the importance of also examining the interplay of symptoms and parenting over time. Thus, studies that examine cascade or cross-lag models as a complementary analysis can help to delineate the pathways through which these trajectories may be developing.

To address these gaps in the literature, the present study pursued two aims: (1) classify individuals based on the concurrent development of externalizing and internalizing symptoms starting from toddlerhood to late childhood, and (2) identify the ways in which externalizing and internalizing symptoms as well as harsh parenting relate to one another from toddlerhood to middle childhood by (2a) classifying individuals based on both child- and parent-level trajectories and (2b) characterizing the reciprocal contributions of externalizing and internalizing symptoms as well as harsh parenting to one another over time. We utilized longitudinal data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, which presents significant advantages over much of the past research in this area. The Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study contains a large cohort of children and families (N = 4397), sampled to be representative of American families living in urban settings. Moreover, this dataset is enriched for risk through oversampling single parent births, resulting in a large representation of children living in low socioeconomic conditions and from racial and ethnic minority groups.

Methods

Participants

Data were from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (Reichman et al., 2001), which follows a large, population-based cohort of predominantly low-income children born in 20 cities in the United States between 1998 and 2000. Families were recruited to participate at the hospital after the focal child’s birth. The present study used data from mother or other primary caregiver in-home interviews at ages 3, 5, and 9 of the child from 18 of the 20 cities, as two of the cities had pilot data from a different set of questions. Of a total 4898 families recruited to participate, 4397 completed the symptom domains measure (Child Behavior Checklist) and 4192 completed the harsh parenting measure (Conflict Tactics subscales Psychological Aggression and Physical Assault) for at least one of the three time points (ages 3, 5, and 9); these data were included in the analyses. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample and class characteristics.

Classes based on internalizing and externalizing symptoms as well as harsh parenting (see Figure 2B for a depiction of classes). Main analyses (parallel process latent class growth analyses and cascade model) controlled for maternal education, race/ethnicity, age, child gender and family structure. Internalizing and externalizing symptoms as measured by mother-reported CBCL and harsh parenting as measured by Conflict Tactics, unless otherwise indicated. Based on available data, father reports at age 5 consisted of a subset of CBCL questions (6 items each for internalizing and externalizing; “subset”, N = 557). Teacher report on the CBCL aggressive subscale of externalizing are available and reported here (“aggress”, N = 1006). Additionally, internalizing- and externalizing-like items (6 items for the former, 8 items for the latter) are reported from the Conners Teacher Rating Scale (“Conners”, N = 2243)

| Class | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| All | Normative | Severe-Decreasing | Severe | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| N | 4383 | 3004 | 1189 | 190 | χ2 | df | p | |

|

| ||||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | 14.3 | 6 | 0.026 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Black | 48.3% | 48.3% | 49.1% | 43.2% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Hispanic | 27.0% | 27.5% | 25.6% | 27.9% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| White | 21.1% | 21.3% | 20.4% | 23.7% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Other | 3.6% | 3.0% | 5.0% | 5.3% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Child Gender (%female) | 47.5% | 48.3% | 46.4% | 41.1% | 4.56 | 2 | 0.102 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Family structure | 38.4 | 4 | <.001 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Single mother | 48.2% | 36.7% | 45.4% | 45.2% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Married couple | 24.2% | 26.5% | 19.8% | 17.4% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Cohabitating couple | 27.5% | 36.8% | 34.8% | 37.4% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Mother’s education | 43.1 | 6 | <.001 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Less than high school | 33.9% | 33.1% | 36.2% | 34.7% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| High school or equivalent | 30.9% | 29.2% | 34.1% | 36.8% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Some college/tech school | 24.5% | 25.5% | 23.1% | 17.9% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| College or graduate school | 10.6% | 12.3% | 6.6% | 10.5% | F | df | p | |

|

| ||||||||

| Mother’s age (M, SD in years) | 25.2 (6.0) | 25.4 (6.1) | 24.7 (5.7) | 25.3 (6.3) | 5.53 | 2,4380 | 0.004 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Internalizing (M, SD) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| age 3 | .347 (.25) | .257 (.19) | .516 (.26) | .544 (.32) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| age 5 | .222 (.21) | .154 (.14) | .340 (.21) | .572 (.37) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| age 9 | .210 (.18) | .120 (.12) | .236 (.16) | .723 (.35) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Other informants: | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| age 5 - Father (subset) | .202 (.28) | .160 (.22) | .282 (.35) | .283 (.36) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| age 9 - Teacher (Conners) | .406 (.36) | .362 (.33) | .475 (.39) | .628 (.44) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Externalizing | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| age 3 | .621 (.36) | .451 (.24) | .948 (.30) | .929 (.39) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| age 5 | .443 (.30) | .323 (.20) | .684 (.27) | .870 (.42) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| age 9 | .181 (.20) | .106 (.11) | .272 (.16) | .700 (.32) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Other Informants: | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| age 5 - Father (subset) | .563 (.39) | .503 (.37) | .671 (.42) | .717 (.37) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| age 5 - Teacher (aggress) | .232 (.34) | .178 (.28) | .310 (.40) | .545 (.47) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| age 9 - Teacher (Conners) | .353 (.45) | .295 (.41) | .456 (.50) | .582 (.50) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Harsh parenting | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| age 3 | .160 (.14) | .120 (.11) | .240 (.15) | .208 (.16) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| age 5 | .153 (.13) | .116 (.11) | .236 (.15) | .223 (.15) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| age 9 | .210 (.18) | .176 (.15) | .270 (.21) | .295 (.21) | ||||

Measures

Externalizing and Internalizing Symptoms

Psychological symptom domains (internalizing, externalizing) were assessed using the parent-report form of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). Parents indicated whether the statement of the behavior (e.g., “unhappy, sad or depressed” for internalizing or “argues a lot” for externalizing) is “never true”, “sometimes or somewhat true”, or “very true or often true”. For internalizing symptoms, there were 16, 23, and 21 items at ages 3, 5, and 9, respectively; for externalizing symptoms, there were 22, 30, and 35 items. The CBCL/2-3 version (Achenbach, 1992) was collected at age 3, CBCL/4-18 (Achenbach, 1991) at age 5, and CBCL/6-18 (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) at age 9. Although different versions of the CBCL are given across ages, the constructs that they measure are similar across versions. Moreover, the CBCL/2-3 version contains modifications of the questions for very young children in order to measure symptom domains in a developmentally appropriate manner. To be consistent with the CBCL/2-3 and CBCL/4-18, the somatic complaints subscale was not included when calculating internalizing symptoms for CBCL/6-18. Mean item scores were calculated to represent each subscale, and thus all subscales ranged from 0 to 2. Both internalizing (Cronbach’s alphas = .75, .76, and .84 for ages 3, 5, and 9 respectively) and externalizing symptoms had acceptable internal reliability (Cronbach’s alphas = .88, .87, .91).

Harsh Parenting

Harsh parenting was measured using the mean of the Psychological Aggression and Physical Assault subscales (10 items total) of the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales. The questionnaire asked mothers how often, in the past year, they had performed parenting behaviors related to psychological aggression (e.g., “Shouted, yelled, or screamed at [CHILD]”; “Called [CHILD] dumb or lazy or some other name like that”) and physical assault (e.g., “Spanked [CHILD] on the bottom with your bare hand”; “Hit [CHILD] on the bottom with something like a belt, hairbrush, a stick, or some other hard object”). Both subscales were scored for annual chronicity with severity weights in accordance with the frequencies indicated by the response categories. The subscales were standardized to a 0 to 1 scale, indicating the proportion of possible total score (Straus, 2001; Straus et al., 1998). The ten items from both subscales that comprised our harsh parenting measure have Cronbach’s alpha values of .74, .73, and .70 for ages 3, 5, and 9 respectively.

Analysis Plan

Aim 1: Classify Children on Externalizing & Internalizing Symptom Co-Development

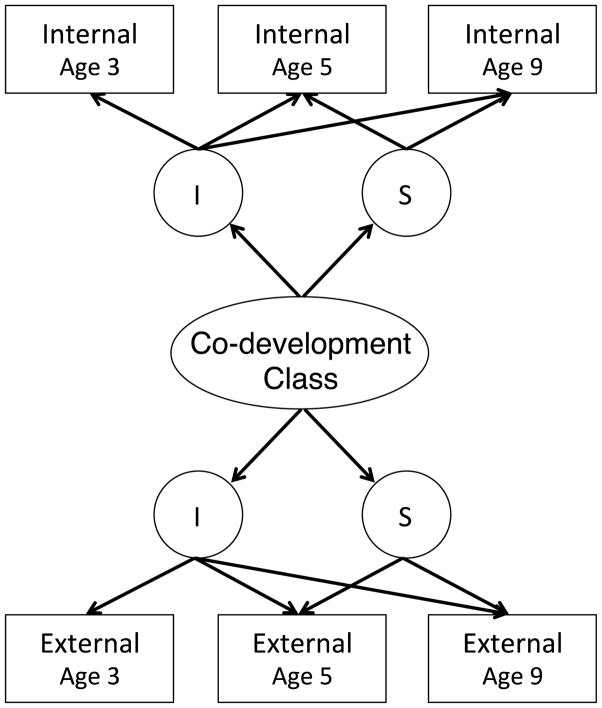

To accomplish our first aim, we classified individuals based on the concurrent development of externalizing and internalizing symptoms starting from toddlerhood using parallel process latent class growth analysis, with Mplus version 7.11 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2007). Latent class growth analysis is a person-centered analysis that allows identification of unobserved/latent but distinct groups of individuals who have similar developmental trajectories (Muthen & Muthen, 2000; Wright & Hallquist, 2013). To address our primary aim of identifying groups of individuals who have similar trajectories of symptoms, we used parallel process latent class growth analysis, which assigns individuals to groups based on initial levels (intercepts) and changes (slopes) in both internalizing and externalizing symptoms concurrently (Figure 1) (Wu et al., 2010).

Figure 1. Parallel process latent class growth analysis visualization for internalizing and externalizing co-development classes.

Internal = internalizing symptoms, External = externalizing symptoms, I = intercept, S = slope.

Following established procedures (Jung & Wickrama, 2008), we estimated models with one to six classes and chose the best fitting model based on comprehensively considering multiple fit indicators (LMR-LRT, VLMR, AIC, BIC, SSABIC, entropy, and a minimum class size of 1%) as well as interpretability. As our goal was to identify classes that were more homogenous with respect to slope and intercept, we constrained these parameters to be invariant within each class. This approach can lead to more groups, but groups that are more homogenous because within class variation in intercept and slope is constrained. Beyond theoretical motivations, constraining these parameters also helped to avoid convergence issues, as this type of model is highly stable in model convergence and widely used due to this significant advantage (Wright & Hallquist, 2013). To avoid local maxima, models were run with 500 to 1000 random starts.

Aim 2: Identify Inter-Relationships Among Externalizing and Internalizing Symptoms and Harsh Parenting

Our second aim was to identify the ways in which externalizing and internalizing symptoms as well as harsh parenting relate to one another from toddlerhood to middle childhood. To accomplish this, we utilized two complementary analyses. The first used a person-centered approach in order to identify groups of individuals based on their concurrent changes in externalizing and internalizing symptoms as well as harsh parenting. This model allowed us to classify individuals based on both child- and parent-level trajectories. In contrast to an alternative method of using one time point of harsh parenting as a predictor of internalizing and externalizing, using multiple time points of harsh parenting captures change in harsh parenting over time, alongside change in internalizing and externalizing problems. We re-estimated the parallel process latent class growth analysis with externalizing and internalizing symptoms, now including harsh parenting in addition. We used a similar procedure as in Aim 1, estimating models for one to six classes and using model fit indices to identify the best-fitting solution. This analysis was aimed at understanding the extent to which trajectories of parenting and internalizing and externalizing symptoms co-develop in parallel over time. This approach yields person-centered trajectories helpful to inform our understanding of the changes in levels of symptoms and parenting over time. However, it does not allow for understanding the dynamic interplay of parenting and child symptomatology over time; thus, we also utilized a complementary, variable-centered approach to examine a cascade model.

The second, variable-centered cascade model identified the reciprocal contributions of externalizing and internalizing symptoms as well as harsh parenting to one another over time. This model allowed us to determine: (1) harsh parenting’s contribution to internalizing symptoms, controlling for externalizing symptoms, and vice versa, (2) the extent to which the relationship between harsh parenting and child symptom domains is transactional and may cascade over time, and (3) interrelationships between internalizing and externalizing symptoms as they bi-directionally influence each other over time. We utilized an auto-regressive cross-lag (cascade) model with externalizing and internalizing symptoms as well as harsh parenting at ages 3, 5, and 9. In this model, each variable was regressed on all the variables at the previous time point. The auto-regressions examined continuity of externalizing and internalizing symptoms as well as harsh parenting. The cross-lags examined interrelationships among externalizing and internalizing symptoms and harsh parenting at each time point, controlling for the previous time point (e.g., child externalizing at age 5 influencing harsh parenting at age 9, controlling for prior harsh parenting and for internalizing). Within-time residual variances were allowed to covary across all variables.

Addressing Missingness and Control Variables

Mplus has the advantage of using the expectation maximization algorithm to obtain maximum likelihood estimates with robust standard errors (full information maximum likelihood). This method results in unbiased estimates when data are missing at random (McCartney, Burchinal & Bub, 2006) and was utilized to estimate all models.

Of the original 4898 families recruited at birth, externalizing and internalizing symptom data were collected on 68%, 76%, and 68% of children at ages 3, 5, and 9; harsh parenting was assessed for 68%, 61%, and 63% of families at ages 3, 5, and 9. Maternal education (F3,4888 = 8.805, p < .001) and ethnicity/race (F3,4882 = 23.790, p < .001) were related to number of time points missing and but child gender was not (t4895 = .187, p = .852).

We addressed attrition by controlling for the characteristics related to missingness, in addition to other demographic variables in the cascade model. The best-fitting parallel process latent class growth models (3-class solutions) were identified without control variables, because of very high computational intensity required to estimate models, particularly in this large sample. The best-fitting models were then repeated with control variables and are reported as the main findings. Control variables were: maternal age at birth of child, race/ethnicity (dummy coded as “Black/African American”, “White/European American”, “Hispanic/Latino(a)”, “other race”), education (“less than high school”, “high school”, “some college”, “college or high degree”), relationship status (“single”, “married”, “cohabitating”), and child gender. Classes were similar with and without control variables.

Addressing Mother as Informant

We took three major steps to address and decrease the possibility that our results would be colored by shared method variance, that is, confounded by a potential tendency for mothers with greater harsh parenting to view their children as having more internalizing or externalizing behavior. First, in the cascade model (Aim 2b), we controlled for stability of child symptoms and of maternal harsh parenting. Thus, the model predicts changes in child symptom domains based on previous changes in maternal harsh parenting and vice versa; therefore, it is less likely that our findings are primarily driven by an overall correlation between maternal depression and child symptoms. Second, in this analysis we also controlled for within-time covariances among all the variables. Third, although it is not possible to formally test for informant effects without non-mother informant data at all time points, father report of internalizing and externalizing symptoms at age 5 (subset of 6 items each construct), teacher report of aggression subscale at age 5, and teacher report of internalizing- and externalizing-like behavior items from the Conners Teacher Rating Scale (6 items for the former, 8 items for the latter) at age 9, are reported to compare with symptom co-development trajectory class patterns estimated with mother-report (Table 1). Cross-informant reports showed a similar pattern of findings as mother report.

Results

Descriptive statistics

A summary of the sample characteristics is in Table 1. The respondents are primarily low socio-economic status, unmarried mothers. A large proportion of the sample identified as racial and/or ethnic minorities.

Aim 1: Classify Children on Externalizing & Internalizing Symptom Co-Development

Parallel Process Latent Class Growth Analysis

Table 2 contains the fit indices for each of the six models (one through six classes) that we ran for internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Entropy values were consistently high (above .80) for two through six classes, indicating high classification accuracy across all models. AIC, BIC, and SSABIC values unilaterally decreased with the addition of each class, indicating a better model fit with more classes, which is often the case with large samples. VLMR and LMR-LRT indicate that having more than three classes did not significantly improve model fit. Moreover, with more than three classes, the smallest class was unacceptably small (less than 1% of the total sample). Thus, the 3-class model was accepted as best fitting and rerun with control variables. Figure 2 contains a graphical depiction of the trajectories for each of the classes in all of the models run. Table 3 shows the estimated slopes and intercepts for each class.

Table 2. Model fit indices and criteria for one- through six-class models.

A. Model including only internalizing and externalizing symptoms, B. Model including harsh parenting in addition to internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Number of classes was chosen based on a comprehensive review of all of the indicators listed in this table as well as interpretability. Optimal models are marked in bold red font. Decreasing values of AIC, BIC, and SSABIC indicate better model fit. P values less than .05 for VLMR and LMR-LRT indicate the model with k classes is preferred over k-1 classes. Entropy values closer to 1 indicate high classification accuracy. In order for the model to be accepted, the smallest latent class (Sm LC) could not be less than 1% of the total sample size.

| C | A. | B. | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||

| INTERNALIZING & EXTERNALIZING | INTERNALIZING, EXTERNALIZING, & HARSH PARENTING | |||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| AIC | BIC | SSABIC | VLMR | LMR-LRT | entropy | Sm LC | AIC | BIC | SSABIC | VLMR | LMR-LRT | entropy | Sm LC | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| 1 | 946 | 1010 | 978 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 100% | −8007 | −7911 | −7959 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 100% |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| 2 | −2927 | −2831 | −2879 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.82 | 19.88% | −12438 | −12298 | −12368 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.80 | 23.56% |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| 3 | −4353 | −4225 | −4289 | 0.207 | 0.213 | 0.81 | 3.84% | −13985 | −13799 | −13892 | 0.261 | 0.265 | 0.79 | 4.59% |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| 4 | −5422 | −5262 | −5341 | 0.079 | 0.082 | 0.84 | 0.43% | −15071 | −14841 | −14955 | 0.027 | 0.029 | 0.82 | 0.41% |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| 5 | −6019 | −5827 | −5923 | 0.206 | 0.210 | 0.81 | 0.32% | −16016 | −15741 | −15878 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.81 | 0.41% |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| 6 | −6438 | −6214 | −6326 | 0.222 | 0.226 | 0.84 | 0.32% | −16663 | −16344 | −16502 | 0.204 | 0.205 | 0.80 | 0.34% |

C = number of classes in model, AIC = Akaike information criterion, BIC = Bayesian information criterion, SSABIC = sample size-adjusted Bayesian information criterion, VLMR = Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin test p value, LMR-LRT = Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test p value, Sm LC = size of smallest latent class as a percentage of total sample

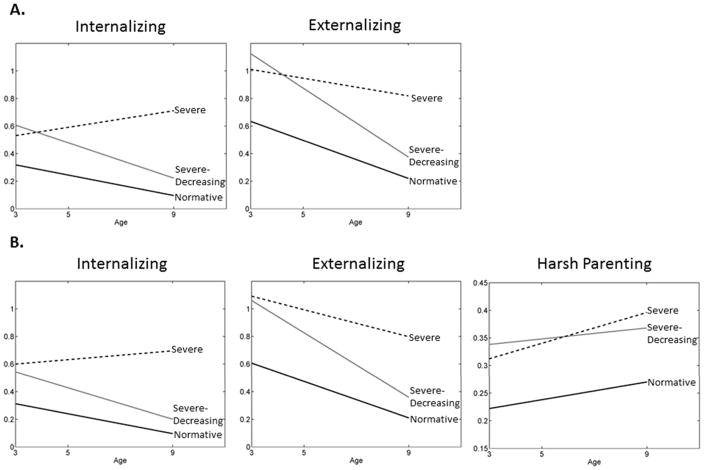

Figure 2. Characterization of trajectory groups.

Estimated growth trajectories for parallel process latent growth analyses with: (A) internalizing and externalizing symptoms, (B) harsh parenting in addition to internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Normative symptoms class = 73%, 69% of sample, Severe-decreasing symptoms class = 23%, 27%, Severe symptoms class = 3.8%, 4.3%, as calculated in (A) and (B) respectively. Analyses controlled for maternal education, race/ethnicity, age, relationship status, and child gender.

Table 3. Parameter estimates for parallel process latent growth analyses.

Parameter estimates for each class in model when including (A) internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Aim 1) and (B) when including harsh parenting in addition to internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Aim 2a).

| Class | A. | B. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Internalizing | Externalizing | Internalizing | Externalizing | Harsh Parenting | ||

|

|

||||||

| Normative | Intercept | 0.318 | 0.634 | 0.312 | 0.606 | 0.222 |

|

| ||||||

| CI | [.273, .364] | [.562, .706] | [.265, .358] | [.526, .685] | [.193, .251] | |

|

| ||||||

| Slope | −0.037 | −0.069 | −0.036 | −0.066 | 0.008 | |

| CI | [−.046, −.028] | [−.081, −.057] | [−.045, −.028] | [−.077, −.055] | [.002, .015] | |

|

| ||||||

| N | 3204 | 3004 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Resilient | Intercept | 0.606 | 1.125 | 0.542 | 1.061 | 0.338 |

|

| ||||||

| CI | [.535, .677] | [1.029, 1.220] | [.470, .613] | [.947, 1.174] | [.306, .369] | |

|

| ||||||

| Slope | −0.064 | −0.125 | −0.057 | −0.117 | 0.005 n.s. | |

|

| ||||||

| CI | [−.079, −.049] | [−.143, −.107] | [−.070, −.044] | [−.136, −.099] | [−.003, .012] | |

|

| ||||||

| N | 1013 | 1189 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Severe | Intercept | 0.531 | 1.011 | 0.599 | 1.092 | 0.312 |

|

| ||||||

| CI | [.389, .672] | [.842, 1.180] | [.431, .766] | [.835, 1.349] | [.262, .362] | |

|

| ||||||

| Slope | 0.03 | −0.032 | 0.016 n.s. | −0.049 | 0.014 | |

|

| ||||||

| CI | [<.001, .060] | [−.064, −.001] | [−.014, .045] | [−.085, −.014] | [.005, .024] | |

|

| ||||||

| N | 165 | 190 | ||||

CI = 95% confidence intervals. Slopes significantly different from zero (p < .05) are indicated in bold, n.s. = slope not significantly different from zero (i.e., steady).

The co-development of internalizing and externalizing symptoms was best described by three classes. The normative symptoms class, encompassing 73% of the sample, was marked by initially low, declining levels of internalizing symptoms and initially medium, declining levels of externalizing symptoms. The next largest class (23%, severe-decreasing symptoms) had initially medium levels of internalizing symptoms that decreased over time and initially high but quickly declining externalizing symptoms. The severe symptoms class (3.8%) represented a subgroup of individuals that started with medium levels of internalizing symptoms that increased and high, slightly decreasing externalizing symptoms levels. Of note, compared to each other, the severe-decreasing and severe symptoms classes had similar levels of internalizing and externalizing problems at age 3. However, the severe-decreasing and severe symptoms classes differed in terms of slope: whereas the severe-decreasing symptoms class had very steep declines in both types of symptoms after age 3, the severe symptoms class failed to exhibit as sharp a decrease in externalizing symptoms and displayed an increase in internalizing symptoms.

Aim 2: Identify Inter-Relationships Among Externalizing and Internalizing Symptoms and Harsh Parenting

A. Parallel Process Latent Class Growth Analysis

Table 2 contains the fit indices for each of the six models (one through six classes) that we ran for internalizing, externalizing, as well as harsh parenting concurrently. The same criteria as in the parallel process latent class growth analysis for internalizing and externalizing alone (Aim 1) was used to identify the optimum number of classes for this analysis. The three-class model was identified as best-fitting and rerun with control variables. Figure 2 shows the trajectories for each class graphically, and Table 3 contains the slopes and intercepts of the trajectories for each class.

The co-development of harsh parenting along with externalizing and internalizing symptoms was best described by three classes. Internalizing and externalizing characteristics of the classes including harsh parenting were almost identical to the model without harsh parenting, with two exceptions in the severe symptoms class: first, externalizing behavior was high and stable when not concurrently considering harsh parenting, but was high and decreasing when including harsh parenting in the model; also, internalizing behavior was high and increasing when not considering harsh parenting, but was high and steady when including harsh parenting in the model.

For the normative symptoms class, which consisted of individuals with low, declining internalizing symptoms and medium, declining externalizing symptoms, harsh parenting started low at age 3 and gradually increased, but was still low by age 9 (69%). The severe-decreasing symptoms class, which consisted of individuals with initially medium internalizing and high externalizing symptoms, both declining sharply over time, were also characterized by high, steady harsh parenting (27%). The severe symptoms class, characterized by high, steady internalizing and high, decreasing externalizing symptoms, had medium levels of harsh parenting that increased (4.3%). Of note, although the slope of harsh parenting in the severe-decreasing symptoms class was not significantly different than zero (i.e., stable harsh parenting) and the slopes of harsh parenting in the normative and severe symptoms classes were different than zero (i.e., increasing harsh parenting), when compared directly, these slope estimates for all of the classes did not significantly differ from each other (see confidence intervals presented in Table 3). Additionally, the severe-decreasing and severe symptoms classes did not significantly differ from each other in initial levels of harsh parenting; both had significantly higher harsh parenting than the normative symptoms class.

B. Cascade Model

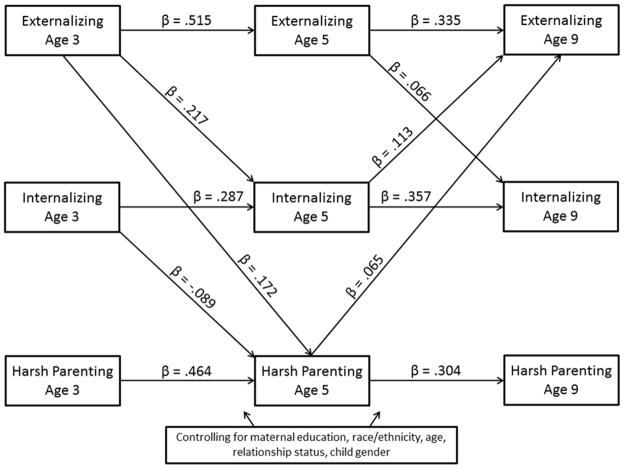

The cascade model, which examined reciprocal contributions among internalizing and externalizing symptoms as well as harsh parenting, showed acceptable fit on several indices (RMSEA = .051, CFI = .988, TLI = .845). Figure 3 shows the path coefficients in the model.

Figure 3. Reciprocal relations among externalizing and internalizing symptoms and harsh parenting.

Significant paths (p < .05) and standardized parameter estimates shown, from the autoregressive cross-lag (cascade) model. Paths specified from every control variable to every externalizing symptoms, internalizing symptoms, and harsh parenting variable. Estimates for all parameters (including non-significant paths) are shown in Table 4.

Harsh Parenting and Individual Symptom Domains

Harsh parenting at age 5 contributed to externalizing symptoms at age 9, controlling for internalizing symptoms. However, harsh parenting did not predict internalizing symptoms, controlling for both externalizing symptoms and stability of harsh parenting and internalizing symptoms.

Transactional relationship of harsh parenting and symptom domains

Externalizing at age 3 was associated with greater harsh parenting at age 5, which in turn was associated with worse externalizing behavior at age 9. In contrast to externalizing symptoms, contrary to expectations, higher levels of internalizing symptoms at age 3 were associated with less harsh parenting at age 5.

Inter-relationship of Externalizing and Internalizing Symptoms

Higher levels of externalizing symptoms at age 3 was associated with worse internalizing problems at age 5, which in turn predicted more externalizing behavior at age 9. Higher externalizing behavior at age 5 predicted greater internalizing problems at age 9.

Overall, the cascade model shows a transactional relationship in which internalizing and externalizing symptoms at age 3 predict changes in harsh parenting at age 5, which in turn predicts increased externalizing problems at age 9. Age 3 externalizing symptoms also predict increases in internalizing problems at age 5, which in turn predicts increases in externalizing problems at age 9. In other words, early externalizing symptoms worsens parenting and internalizing behavior at age 5, which in turn appear to further exacerbate externalizing problems at age 9. Moreover, externalizing and internalizing symptoms appear to be mechanisms by which each is maintained, as internalizing behavior at age 5 increases externalizing problems at age 9 and externalizing behavior at both 3 and 5 increase later internalizing problems (age 5 and 9).

Conclusion

To summarize, Aim 1 was to identify classes of individuals based on internalizing and externalizing symptoms concurrently. This study documented three symptom co-development classes: normative (low), severe-decreasing (initially high but declining), and severe (high) symptoms trajectories. Aim 2 was to identify the ways in which externalizing and internalizing symptoms as well as harsh parenting relate to one another from toddlerhood to middle childhood. This study found that whereas normatively harsh parenting increased after toddlerhood, the severe-decreasing and severe symptoms classes were characterized by higher levels and steeper increases in harsh parenting. The cascade model documented a transactional relationship between symptoms, particularly externalizing symptoms, and harsh parenting cascading over time in this period. Lastly, this study showed that externalizing and internalizing symptoms influenced each other; for example, we found that internalizing behavior appeared to be a mechanism by which externalizing problems increased over time.

Examining externalizing and internalizing symptoms in context of one another allowed for the categorization of joint trajectories that would otherwise have been obscured by examining symptom domain trajectories in isolation. In particular, the most severe, non-normative symptom co-development class was characterized by internalizing and externalizing symptoms that did not change in tandem with each other. For most children (normative symptoms class), internalizing and externalizing symptoms were low across this age period; for another, a substantial portion of children (severe-decreasing symptoms class), symptoms started relatively high at age 3 but then showed normalizing improvements through childhood, even in the presence of high levels of harsh parenting. Of note, however, in the severe symptoms class, internalizing problems increased, whereas externalizing symptoms stayed stable. This pattern is consistent with studies demonstrating that externalizing generally decreases from the toddler years into school age (e.g., Miner & Clarke-Stewart, 2008), but that internalizing symptoms may emerge at the same time (e.g., Achenbach et al., 1991). Interestingly though, it appears that for the severe symptoms group when externalizing behavior fails to decrease (e.g., normalize) by middle childhood, internalizing problems concurrently worsen over time. Examining either internalizing or externalizing symptoms separately, as many studies have done, may not have been able to identify the extent to which these trajectories co-develop across different groups of individuals. Investigating externalizing symptom trajectories alone would give the impression that for individuals in the severe symptoms class, symptom severity is not worsening, but by including internalizing symptoms in this co-development model, we identified a subgroup of individuals whose internalizing problems become worse over time even as their externalizing behavior has leveled off. Thus, the research implications of these findings point to the importance of examining parallel processes in order to better distinguish classes of individuals and find highly clustered groups.

The parallel process latent class growth analysis also afforded a more developmental view of comorbidity than noting that, at a single time point, internalizing problems were high and externalizing problems were high. For example, one group of children we identified (severe-decreasing symptoms class) would be considered to have comorbid internalizing and externalizing symptoms (high levels of both) in toddlerhood; however, both symptom domains decreased with time. This implies that, for these children, improvement across development was cross-domain. There is another class (severe symptoms) that maintained high symptoms of both internalizing and externalizing symptoms across this time period, which could be considered comorbidity, but the symptom domains did not change in tandem with each other – internalizing symptoms increased whereas externalizing symptoms stayed stable across development. Thus, our analytic approach of examining how symptom domains changed concurrently allowed for a more nuanced picture of the trajectories of comorbidity across development.

Aim 2 was to examine the inter-relationships among internalizing and externalizing symptoms as well as harsh parenting. In the first of two complementary analyses to address Aim 2, we extended the parallel process latent class growth analysis to examine how trajectories of harsh parenting changed alongside externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Three classes, replicating the symptom co-development classes we identified with externalizing and internalizing symptoms alone, additionally documented how the symptom domains changed as harsh parenting changed. The severe and severe-decreasing symptoms classes both experienced high, increasing harsh parenting, but the former worsened in symptoms whereas the latter’s symptoms normalized. The analyses revealed that levels of harsh parenting at age 3 were relatively uninformative of which children would improve versus worsen in severity, as both the severe and severe-decreasing symptoms classes had relatively high harsh parenting. It would be important in future studies to identify which factors beyond parenting (e.g., specific genes, other contextual factors) may identify youth in the severe-decreasing symptoms group and illuminate why these youth appeared to improve even though the parenting they received was relatively harsh. Ultimately, most children high on early externalizing symptoms do desist and thus identifying factors that contribute to desistence (without concurrent increases in internalizing symptoms) can help inform intervention efforts during this age period.

Examining complementary models allowed for an examination of how harsh parenting is associated with joint trajectories as well as internalizing and externalizing symptoms uniquely. The parallel process latent class growth analysis with harsh parenting as well as internalizing and externalizing symptoms examined the association between harsh parenting trajectories and joint internalizing-externalizing symptom trajectories, whereas the cascade model examined how harsh parenting as well as internalizing and externalizing symptoms cascaded and influenced each other over time, controlling for auto-regressive paths and within time, cross-construct correlation. The highest trajectories of harsh parenting were associated with the severe-decreasing and severe classes of internalizing and externalizing symptoms. However, the contribution of harsh parenting to internalizing and externalizing symptoms separately while modeling transactions at each time point showed that harsh parenting only contributed unique variance to externalizing symptoms, controlling for internalizing symptoms, not vice versa. Previous studies on toddlerhood have found much more support for harsh parenting contributing to externalizing symptoms (e.g., Waller et al., 2012), but there is much less support for harsh parenting contributing to internalizing symptoms (Callahan et al., 2011). Our findings suggest that previous research may have seen a link from harsh parenting to internalizing symptoms only due to the extent to which internalizing and externalizing symptoms overlap.

Of note, however, harsh parenting and internalizing symptoms were not completely unrelated. Harsh parenting was related to internalizing symptoms, but not in the direction that most papers examine (parenting predicting child outcome). Instead of parents influencing their children, in the case of harsh parenting and internalizing symptoms in this early time period (and externalizing symptoms at age 9), children’s increasing internalizing symptoms was related to decreasing harsh parenting. Interestingly, though the joint trajectory models would suggest that harsher parenting would be associated with greater internalizing symptoms over time, the results in the cascade model, suggest that, when controlling for levels of externalizing symptoms, from age 3 to 5, internalizing symptoms may prompt decreases in harsh parenting. It could be that when children have early internalizing symptoms (without high externalizing symptoms), this child behavior leads parents to soften their approach over time in response to their child’s depressed or anxious feelings. These findings emphasize the importance of considering bidirectional parent-child effects (Bell, 1968; Leve et al., 2010; Scarr & McCartney, 1983).

In contrast to the dampening effect of children’s internalizing symptoms on harsh parenting, externalizing symptoms were associated with greater harsh parenting, which in turn was associated with later worse externalizing symptoms. These results indicate that not only did harsh parenting increase externalizing symptoms, children’s externalizing may have elicited greater harsh parenting. These findings are consistent with a developmental psychopathology perspective, which emphasizes that influences between parents and children are bidirectional and reciprocally relate over time. Moreover, these findings are consistent with previous research indicating that child externalizing symptoms elicit harsher parenting (Lansford et al., 2009; Scaramella et al., 2008) and that child to parent and parent to child effects in externalizing symptoms and harsh parenting may cascade over time, consistent with Patterson and others’ model (Patterson et al., 1989).

The cascade model also allowed for the characterization of the interactions between the two symptom domains, internalizing and externalizing, over the toddlerhood to middle childhood period. The findings fit with theoretical expectations that externalizing and internalizing symptoms influence each other; specifically, externalizing behavior in early childhood is thought to increase internalizing behavior via peer rejection and academic failure (Patterson et al., 1989). The results support and extend these theoretical expectations by showing that internalizing symptoms appeared to be a mechanism by which externalizing symptoms was maintained: greater externalizing symptoms in toddlerhood were associated with subsequent internalizing symptoms at age 5, which in turn was related to greater externalizing symptoms at age 9. Additionally, externalizing symptoms around the time that children are entering (or about to enter) school age (5 years old) were associated with later increases in internalizing symptoms as well (at age 9). These results are consistent with the idea that as children experience peer rejection (and, in school age, academic failure) as a consequence of their externalizing behavior, this is turned inward and they react with feelings of depression and anxiety (internalizing symptoms), which may in turn lead to later acting out and further increases in externalizing symptoms.

Limitations

Though the study had several notable strengths, including a large number of well-sampled and at-risk families, longitudinal data, and complementary sophisticated quantitative modeling approaches, there are several limitations to consider in interpreting these finding. First, because we used mother report for both the child symptom domains and harsh parenting, it is possible that relationships among the variables are inflated due to shared method variance. Because we do not have data at all time points from non-mother informants, we could not repeat these analyses with non-mother informants. (Non-mother informant data at ages 5 and 9 are shown in Table 1). However, because our cascade model (Aim 2b) controlled for continuity of harsh parenting and symptoms, the model predicts changes in symptoms based on prior changes in harsh parenting and vice versa and may be less affected by shared method variance. In addition, we controlled for within-time covariances among symptom domains and harsh parenting. Thus, an overall correlation between harsh parenting and child symptoms due to mother report is less likely to be primarily driving our findings, though it may still be a factor. Indeed, despite the risk of shared method variance, mother reports of child symptoms may be based on greater time observing the child, because mothers usually spend the most time with the child during this toddlerhood to middle childhood period.

Second, in our sample, younger, Hispanic or other race/ethnicity mothers with less than a high school education were more likely to have missing data, and data were collected on 61–76% of individuals at each time point, of the original 4898 families recruited to participate at birth. Although patterns of attrition may affect our results, this very large sample is population-based and, due to sampling, has disproportionately large numbers of hard-to-reach individuals, such as historically under-served and under-researched minority groups and low socio-economic status groups. Nevertheless, future large scale studies are needed that have and retain large portions of individuals who are younger, Hispanic or with low education.

Third, our study had three time points (ages 3, 5, and 9). A greater number of time points, more densely spaced in time, would have been ideal to detect the transition to full-time schooling and would be necessary to model quadratic trends. Data will be collected on these families at age 15; future studies may use these four time points to examine nonlinear trends.

Last, the growth mixture model approach necessitates judgment about which class structure to choose. The unilaterally decreasing AIC, BIC, and SSABIC seen in the present study’s models are likely because one more class can always be found in such a large sample. However, we took a comprehensive view of all of the indicators (in addition to AIC, BIC, and SSABIC, we considered VLMR, LMR-LRT, entropy, minimum class size of 1%) as well as interpretability of the findings. For complete transparency, we have included the values for the fit indices for all six of the models run for the symptom domains and the symptom domains plus harsh parenting (Table 2). Of note, the number of classes increasing reflected a process by which classes were splitting into subclasses, not individuals moving into completely different categories. This is seen in the consistently high entropy values across models. Thus, choosing a model with one more or less class than we chose would not drastically change the interpretation of the findings.

Future Directions

Our findings lay the groundwork for potentially fruitful directions for future research. Now that the present study has identified symptom co-development classes with ages 3–9, the next step is to follow up with the individuals in adolescence and beyond. In the Fragile Families and Child Well-being Study, the same children who participated in our study will next be assessed at age 15. Adolescence is marked by multiple transitions (school structure, peer and romantic relationships, puberty) as well as an increase in depression and risk-taking (Nelson et al., 2005). As the children age into this time period, future research can examine continuity and discontinuity of the symptom co-development classes. It is possible that, as the literature review on single symptom domains suggests (see Introduction), the number of classes will decrease in adolescence and young adulthood, potentially because the severe-decreasing symptoms class characterized by initially high but declining symptoms normalize to the point of merging with the normative, lowest symptoms class. This would leave two paths in adolescence and onward: one characterized by low symptom levels and another characterized by higher symptom levels, though literature on adolescent delinquency may suggest that a new class could emerge in adolescence (e.g., Shaw et al., 2012). Follow-up with more data points at older ages, however, will be necessary to test these hypotheses. Moreover, with more than three data points, a nonlinear component could be added to examine curvilinear patterns of symptom co-development.

Conclusion

The present study grew out of and supports the developmental psychopathology perspective in three ways. First, the developmental psychopathology perspective promotes examining symptoms dimensionally and as they may co-occur (Cicchetti & Blender, 2004; Cicchetti & Dawson, 2002). Accordingly, changes in two symptom domains concurrently were examined, which helped to classify individuals more precisely than studies examining a single symptom domain. Moreover, the study brought together information from the child (psychological symptom) and parent (harsh parenting) levels in both person-centered (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1996; Curtis & Cicchetti, 2003; Masten, 2007), as and variable-centered cascade (Sameroff, 2010) approaches; this allowed the study to both identify groups of individuals based on concurrent harsh parenting and symptom domain changes as well as characterize the transactional inter-relationships among parenting and child symptom domains. This study represents a step toward explaining issues of multifinality and equifinality (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1996). In particular, illustrating equifinality, the severe-decreasing symptoms class, which started high in externalizing and medium in internalizing symptoms but normalized over time, and the normative symptoms class both had low symptoms at age 9, but exhibited different pathways to that point. As an illustration of multifinality, those in the severe and severe-decreasing symptoms classes demonstrated similar externalizing symptoms at age 3 but had vastly different trajectories over time to end at very different levels of externalizing symptoms at age 9. Lastly, the developmental psychopathology perspective promotes the viewpoint that children are the product of continuous interactions between the child and the child’s environment (Cicchetti, 1984; Sameroff, 2000). In line with this, our study identified groups of individuals based on concurrent trajectories of maladaptive parental actions and reactions to the child (harsh parenting) as well as children’s psychological symptom co-development trajectories. Additionally, we examined the reciprocal contributions among harsh parenting and symptom domains over this toddler to middle childhood period. Thus, our findings begin to illustrate how this transactional relationship unfolds over time. Overall, integrating a developmental psychopathology perspective into the present study, which identified symptom co-development classes and examined symptom co-development in relation to harsh parenting, is a step toward the long-term goal of more fully charting the emergence of psychopathology.

Table 4. Parameter estimates from cascade model.

Autoregressive cross-lag (cascade) model also controlled for maternal education, race/ethnicity, age, relationship status, and child gender. Graphical depiction of the cascade model is in Figure 3.

| Outcome | Predictor | β | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Externalizing age 5 | Externalizing age 3 | .515 | [.468, .562] |

| Internalizing age 3 | .007 n.s. | [−.041, .055] | |

| Harsh parenting age 3 | .028 n.s. | [−.010, .066] | |

| Internalizing age 5 | Internalizing age 3 | .287 | [.237, .336] |

| Externalizing age 3 | .217 | [.168, .266] | |

| Harsh parenting age 3 | .012 n.s. | [−.028, .052] | |

| Harsh Parenting age 5 | Harsh parenting age 3 | .464 | [.425, .503] |

| Internalizing age 3 | −.089 | [−.135, −.042] | |

| Externalizing age 3 | .172 | [.123, .221] | |

| Externalizing age 9 | Externalizing age 5 | .335 | [.286, .383] |

| Internalizing age 5 | .113 | [.067, .159] | |

| Harsh parenting age 5 | .065 | [.025, .104] | |

| Internalizing age 9 | Internalizing age 5 | .357 | [.308, .405] |

| Externalizing age 5 | .066 | [.203, .109] | |

| Harsh parenting age 5 | −.007 n.s. | [−.045, .030] | |

| Harsh Parenting age 9 | Harsh parenting age 5 | .304 | [.257, .351] |

| Internalizing age 5 | .008 n.s. | [−.307, .053] | |

| Externalizing age 5 | .033 n.s. | [−.019, .085] |

Significant paths (p < .05) marked in bold; n.s. = non-significant. Autoregressive pathways shaded in gray. 95% CI = 95% confidence intervals.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) through grants R01HD36916, R01HD39135, and R01HD40421, as well as a consortium of private foundations for their support of the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study. The authors also thank the families who participated and are grateful to Ellen Leibenluft, MD, for encouragement on the manuscript.

References

- Achenbach TM. The classification of children’s psychiatric symptoms: a factor-analytic study. Psychol Monogr. 1966;80(7):1–37. doi: 10.1037/h0093906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checkilst/2-3 and 1992 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1992. [Google Scholar]