Highlights

-

•

A rare case of bilateral chronic maxillary atelectasis is described.

-

•

There is a poor correlate between symptoms and severity of chronic maxillary atelectasis.

-

•

As seen in this case, the term ‘chronic’ maxillary atelectasis can be misleading, and rapid disease progression may occur.

-

•

Re-ventilation of the affected sinuses alleviates symptoms, halts disease progression and facilitates antral re-expansion.

Keywords: Chronic maxillary atelectasis, Sinusitis, Maxillary sinus, Endoscopic sinus surgery

Abstract

Introduction

Chronic maxillary atelectasis (CMA) is a rare acquired condition of persistent and progressive reduction in maxillary sinus volume and antral wall collapse secondary to ostiomeatal obstruction and development of negative intra-sinus pressure gradients.

Case presentation

A 32-year old male was referred with a 6 week history of persistent and worsening sinonasal symptoms, following a significant upper respiratory tract infection. Imaging confirmed bilateral stage I CMA and successful treatment entailed bilateral endoscopic uncinectomy and maxillary antrostomy.

Discussion

Review of the literature has demonstrated CMA to describe an all-encompassing disease process of ostiomeatal obstruction and atelectatic maxillary sinus remodelling that overcomes early variations in taxonomy (‘silent sinus syndrome’, ‘imploding antrum syndrome’, ‘acquired maxillary sinus hypoplasia’) and inconsistencies in reporting. Unilateral CMA is well documented, however a systematic search of the literature reveals only six bilateral cases. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first individual report of bilateral stage I CMA in which the inciting event is established and a uniquely rapid progress of disease followed.

Conclusion

The present literature regarding CMA is incomplete and further investigation is required to provide greater insight into its aetiology and pathogenesis. Minimally invasive endoscopic approaches can be employed to re-establish aeration to the affected maxillary sinus for symptomatic relief, to halt disease progression and facilitate antral remodelling and sinus re-expansion.

1. Introduction

Chronic maxillary atelectasis (CMA) is a rare acquired condition of persistent and progressive reduction in maxillary sinus volume and antral wall collapse secondary to ostiomeatal obstruction and development of negative intra-sinus pressure gradients [1]. It is most prevalent in the third and fourth decades of life, but can occur in children and has no gender preference [2], [3]. First reported in 1964, Montgomery described mucocoele-related opacification of a maxillary sinus, orbital floor collapse and enophthalmos [4]. Three decades later, Soparkar et al. coined the term silent sinus syndrome (SSS) for asymptomatic enophthalmos and hypoglobus in the context of a hypoplastic maxillary sinus [5]. Thereafter, deliberation amongst authors regarding CMA, SSS and other hypoplastic disease processes of the maxillary sinuses led to inconsistencies in reporting and the emergence of additional nomenclature including ‘acquired maxillary sinus hypoplasia’ (MSH) and ‘imploding antrum syndrome’ [2], [6]. CMA has since been classified into three distinct, but progressive stages (Table 1) [1], and based on a systematic review of all reported cases, SSS was demonstrated to be equivalent to, or a subtype of stage III CMA [2], [7]. Furthermore, through careful clinical and radiological evaluation, CMA should be distinguished from congenital MSH which reflects a developmental anomaly and not the acquired defect of CMA. Herein, we report a rare cases of bilateral CMA and review the available literature for this disease process.

Table 1.

Chronic maxillary atelectasis classification [1].

| Stage | Deformity | Features |

|---|---|---|

| I | Membranous | Lateralised posterior maxillary fontanelle |

| II | Osseous | Inward bowing of ≥1 osseous walls (anterior, superior &/or posterior) of the maxillary antrum |

| III | Clinical | Enophthalmos, hyoglobus &/or midfacial deformity |

2. Case report

A 32 year old male was referred with a 6 week history of persistent and worsening bilateral nasal congestion along with malar and periorbital pain, following a significant upper respiratory tract infection. His infective symptoms had resolved with several courses of oral antibiotics, however, his nasal congestion and facial pain continued to worsen. There was a previous history of multiple sports-related traumatic nasal fractures. There was no history of other cranial trauma, acute or chronic rhinosinusitis, sinus surgery or systemic illnesses.

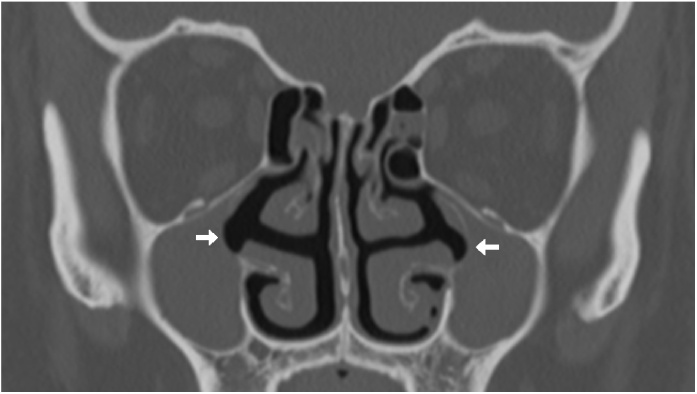

Examination demonstrated right septal deviation and mucopurulent discharge in both middle meatii. Computed tomography (CT) revealed bilateral antral opacification and lateralisation of the posterior maxillary fontanelle, along with lateralisation and demineralisation of the uncinate process bilaterally (Fig. 1). Additional findings included a left concha bullosa and partial opacification of bilateral ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses. Inward bowing of the other osseus walls and orbital floor collapse was not evident. Skin prick testing demonstrated positive responses to house dust mite and cockroach allergens. Findings were consistent with a diagnosis of stage I CMA bilaterally.

Fig. 1.

Coronal computed tomography demonstrating complete bilateral maxillary sinus opacification and uncinate process lateralisation (arrows).

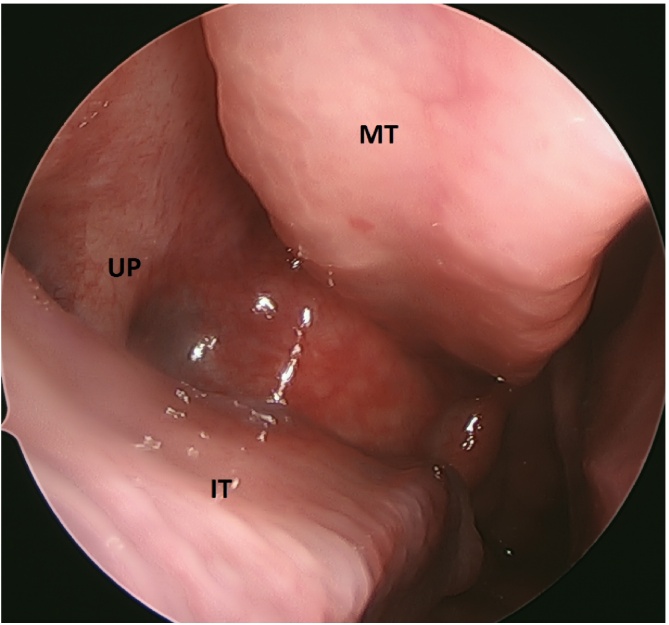

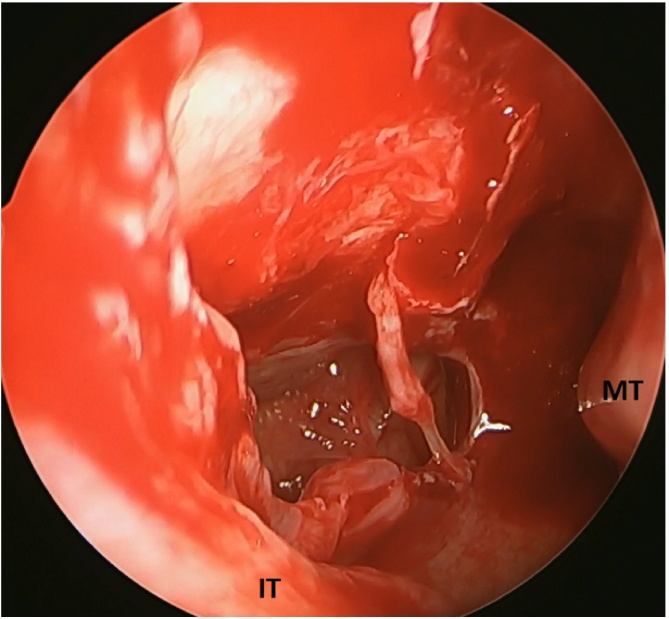

The patient was trialled on maximal medical therapy with intranasal and oral steroids, antibiotics and saline nasal douches without success. He proceeded to undergo bilateral uncinectomy and maxillary antrostomy with image guidance (StealthStation S7®, Medtronic, Minnesota, United States), along with septoplasty and bilateral inferior turbinoplasty (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). The post-operative course was unremarkable and at 9 months of follow-up, the patient remains free of nasal congestion and facial pain, without complication. A post-operative CT performed for unrelated reasons at this time demonstrated well aerated bilateral maxillary sinuses (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

0 ° endoscopic view of left middle meatus demonstrating a lateralised uncinate process. MT – middle turbinate, IT – inferior turbinate, UP – uncinate process.

Fig. 3.

30 ° endoscopic view of left maxillary sinus following antrostomy. MT – middle turbinate, IT – inferior turbinate.

Fig. 4.

Post-operative coronal computed tomography demonstrating well aerated bilateral maxillary sinuses.

3. Discussion

SSS defines the uncommon constellation of spontaneous enophthalmos, hypoglobus and radiographic evidence of maxillary sinus atelectasis, opacification and orbital floor collapse [5]. It is distinguished from CMA by its ‘silent’ progression with absence of significant sinonasal symptoms. Although presented initially as distinct clinical entities, subsequent evaluation has demonstrated SSS and CMA to be of the same disease spectrum, with incorporation of SSS into the CMA staging classification [2], [7]. Unilateral CMA, particularly the SSS subtype, is now well documented in the literature with multiple individual and series reports. Bilateral CMA however is not, and a systematic search of PUBMED, MEDLINE and EMBASE databases revealed only six cases (Table 2) [1], [8], [9], [10], [11].

Table 2.

Literature review of bilateral CMA.

| Author | Age/Sex | Presenting Symptoms | CMA Stage | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kass et al. [1] | 64/M | Sinonasal | I | Unknown |

| 30/F | Sinonasal | I | Unknown | |

| Liss et al. [8] | 56/M | Orbital | III | Endoscopic MMA & OFR |

| Sun and Dubin [11] | 52/M | Orbital & Sinonasal | III | Endoscopic maxillary os balloon dilation |

| Suh et al. [10] | 29/M | Incidental (Orbital) | III | Endoscopic MMA |

| Ferri et al. [9] | 27/F | Orbital | III | Endoscopic MMA & OFR |

M – male, F – female, MMA – middle meatal antrostomy, OFR – orbital floor reconstruction.

Correlation between symptoms and severity of CMA is poor. As in our case, early stage CMA is typified by sinonasal symptoms of nasal congestion, rhinorrhoea, facial pressure and pain and post-nasal drip [2]. As sinus atelectasis advances, diplopia, enophthalmos, lagophthalmos, hypoglobus and mid-face asymmetry become apparent [8], [9], however gradual alterations, particularly if bilateral, may go unnoticed by patients, with detection only occurring when imaging is performed for unrelated reasons [10]. Characteristic CT findings include near or total opacification of the affected sinus, ostiomeatal obstruction and inward bowing of antral walls, including orbital floor displacement [7]. Our patient experienced severe symptoms and rapid disease progression and stage I CMA was diagnosed within 6 weeks of initial symptom onset. Given the poor correlation between symptoms and disease severity, the mean duration over which atelectasis develops is unknown. Ferri et al. described their patient developing stage III CMA within 4 months of endoscopic sinus surgery on the contralateral maxillary sinus [9]. Their findings, in association with ours, suggest that the chronicity of CMA may, in some cases, be shorter than the term ‘chronic’ suggests.

The aetiology and pathogenesis of CMA are yet to be completely defined, however the present hypothesis describes sustained maxillary ostiomeatal complex obstruction following an acute event. This inciting event is often unknown but an acute infection, recurrent infections or trauma (including previous surgery) as antecedent events to severe inflammation and obstruction in the maxillary ostiomeatal locality have been suggested [9], [12]. A deficiency in the posterior attachment of the uncinate process to the inferior turbinate and hypermobility of the medial infundibular wall have also been put forth as underlying anatomical factors promoting development of a one-way flap valve which may exacerbate ostial occlusion during times of inflammation [1], [13]. Additionally, CMA in the context of previous chemoradiotherapy has been reported, raising the possibility of mucosal changes as long-term sequelae of adjuvant therapy being an aetiological consideration [8]. Irrespective of the aetiology, maxillary ostiomeatal obstruction and consequent sinus hypoventilation is believed to lead to sinus mucosal gas absorption and the development of a negative pressure gradient within the sinus. Manometric studies have recorded this at −8.4 ± 2.6 cm H2O on average, however this gradient may decrease to approach atmospheric pressures with advancing disease and greater opacification [14]. Thereafter, chronic inflammation and mucous retention is thought to be responsible for atelectatic remodelling with inward displacement and demineralisation of the affected antral walls [7]. It has been demonstrated that concurrent expansion occurs in the infratemporal, nasal and orbital compartments and this is postulated to be a compensatory mechanism to redistribute volume in the mid-face and prevent clinical asymmetry [15]. In their series, Lin et al. noted the volume of the affected maxillary sinus to be on average, less than half the volume of the unaffected one and this led to a 10.3% increase in orbital volume and 10.4% increase in mid orbital height [12]. However, preferential enlargement of one compartment over another has not been observed and individual variability is purported to be of significant influence, accounting for the enophthalmos and hyoglobus in the SSS subset of stage III CMA patients [15].

Successful treatment of CMA entails re-establishment of aeration to the affected maxillary sinus. In our case, bilateral uncinectomy and maxillary antrostomy were performed, and this minimally invasive endoscopic approach is the contemporary standard of care [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. Successful re-ventilation is important for symptomatic relief and halting disease progression, but also facilitates antral remodelling and sinus re-expansion. A recent volumetric analysis demonstrated post-operative reductions in orbital volumes and increases in maxillary sinus volumes at an average of 11.1 months follow-up, however complete normalisation to baseline sizes was not evident with orbital and sinus volumes remaining at 104.5% and 60.1% respectively, in comparison to the unaffected side [12]. Equivalent outcomes were noted by Sivasubramaniam et al. in their series of 18 patients with enophthalmos, with complete clinical resolution in 14 and partial resolution, sufficient to forgo aesthetic concerns, in 3 patients, 6–18 months following endoscopic maxillary antrostomy [16]. Given the likelihood of spontaneous orbital floor elevation and reversal of clinical asymmetry, strong credence is given to delaying orbital floor reconstruction procedures [16]. Recently, Sun and Dubin proposed in-office balloon dilation of the maxillary ostium as a cost- and risk-effective alternative to endoscopic surgery for CMA [11]. Preliminary outcomes of symptom alleviation and antrostomy patency in 4 patients were promising, however follow-up was limited to a maximum of 4 months.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, the present literature regarding CMA is incomplete and further investigation is required to provide greater insight into its aetiology and pathogenesis. We present the first individual report of bilateral stage I CMA in which the inciting event was established and uniquely rapid progress of disease followed. For this case, bilateral endoscopic uncinectomy and maxillary antrostomy was successful in resolving symptoms and preventing further disease advancement.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Sources of funding

None.

Ethical approval

The study has been approved by Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) for the Western Sydney Local Health District, New South Wales Australia.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Dakshika A. Gunaratne – study design, data collection, manuscript preparation.

Zubair Hasan – study design, manuscript preparation.

Peter Floros – study design, manuscript preparation.

Narinder Singh – study design, data collection, manuscript preparation.

Guarantor

I, Dakshika A. Gunaratne, accept full responsibility for the work and/or conduct of the study. I had access to the data and controlled the decision to publish.

References

- 1.Kass E.S., Salman S., Rubin P.A. Chronic maxillary atelectasis. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1997;106(2):109–116. doi: 10.1177/000348949710600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandt M.G., Wright E.D. The silent sinus syndrome is a form of chronic maxillary atelectasis: a systematic review of all reported cases. Am. J. Rhinol. 2008;22(1):68–73. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kass E.S., Salman S., Montgomery W.W. Chronic maxillary atelectasis in a child. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1998;107(7):623–625. doi: 10.1177/000348949810700714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montgomery W.W. Mucocele of the maxillary sinus causing enophthalmos. Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon. 1964;43:41–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soparkar C.N., Patrinely J.R., Cuaycong M.J. The silent sinus syndrome. A cause of spontaneous enophthalmos. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(4):772–778. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31267-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosko J.R., Hall B.E., Tunkel D.E. Acquired maxillary sinus hypoplasia: a consequence of endoscopic sinus surgery? Laryngoscope. 1996;106(10):1210–1213. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199610000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mangussi-Gomes J., Nakanishi M., Chalita M.R. Stage II chronic maxillary atelectasis associated with subclinical visual field defect. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;17(4):409–412. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1351679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liss J.A., Patel R.D., Stefko S.T. A case of bilateral silent sinus syndrome presenting with chronic ocular surface disease. Ophthal. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011;27(6):e158–60. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e318208356c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferri A., Ferri T., Sesenna E. Bilateral silent sinus syndrome: case report and surgical solution. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012;70(1):e103–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suh J.D., Ramakrishnan V., Lee J.Y., Chiu A.G. Bilateral silent sinus syndrome. Ear. Nose. Throat J. 2012;91(12):e19–e21. doi: 10.1177/014556131209101217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun D.Q., Dubin M.G. Treatment of chronic maxillary atelectasis using balloon dilation. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2013;149(5):782–785. doi: 10.1177/0194599813500634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin G.C., Sedaghat A.R., Bleier B.S. Volumetric analysis of chronic maxillary atelectasis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy. 2015;29(3):166–169. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2013.27.4173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ende K., Mah L., Kass E.S. Progression of late-stage chronic maxillary atelectasis. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2002;111(8):759–762. doi: 10.1177/000348940211100819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kass E.S., Salman S., Montgomery W.W. Manometric study of complete ostial occlusion in chronic maxillary atelectasis. Laryngoscope. 1996;106(10):1255–1258. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199610000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohn J.C., Rootman D.B., Xu D., Goldberg R.A. Infratemporal fossa fat enlargement in chronic maxillary atelectasis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2013;97(8):1005–1009. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-303299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sivasubramaniam R., Sacks R., Thornton M. Silent sinus syndrome: dynamic changes in the position of the orbital floor after restoration of normal sinus pressure. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2011;125(12):1239–1243. doi: 10.1017/S0022215111001952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]