Abstract

Postoperative scar appearance is often a significant concern among patients, with many seeking advice from their surgeons regarding scar minimization. Numerous products are available that claim to decrease postoperative scar formation and improve wound healing. These products attempt to create an ideal environment for wound healing by targeting the three phases of wound healing: inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. With that said, preoperative interventions, such as lifestyle modifications and optimization of medical comorbidities, and intraoperative interventions, such as adherence to meticulous operative techniques, are equally important for ideal scarring. In this article, the authors review the available options in postoperative scar management, addressing the benefits of multimodal perioperative intervention. Although numerous treatments exist, no single modality has been proven superior over others. Therefore, each patient should receive a personalized treatment regimen to optimize scar management.

Keywords: scar management, scar revision, wound healing

An ideal scar is one that is largely undetectable, at the same level as the adjacent tissue, and with the same coloration as the surrounding skin. Numerous therapies and techniques are utilized to increase wound healing and decrease scar formation, some with proven benefits, and others with only anecdotal support. Although this article provides a brief overview of wound healing physiology, its main focus is providing the reader with a comprehensive discussion of products and techniques used to help optimize outcomes of postoperative scars (Table 1).

Table 1. Scar care products.

| Product | Cost | When to initiate treatment | Duration of treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic ointment | $ | POD 0 | 1–3 wk |

| Petroleum jelly | $ | POD 0 | 1–3 wk |

| Mederma | $ | POD 0 | 1–3 wk |

| Pressure dressings | $ | POD 0 | ≥ 6 mo |

| Paper tape | $$ | POD 0 | ≥ 6 wk |

| Silicone gel sheets | $$ | POD 0 | 3–6 mo |

| Prineo | $$ | POD 0 | 2–3 wk |

| PracaSil | $$ | POD 0 | 3 mo |

| Scar massage | − | 3 wk | ≥ 6 wk |

| Sunscreen | $ | 3 wk | ≥ 18 mo |

| Embrace | $$ | < 6 mo | 8 wk |

| Lasers | $$$ | 2–3 mo | 6 wk |

| Dermabrasion | $$$ | 2–3 mo | 3 mo |

| Revision surgery | $$$$ | > 18 mo | – |

Abbreviations: POD, postoperative day.

Wound Healing

Our current understanding of wound healing goes beyond simply categorizing the process into its three stages: inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling.1 A multitude of growth factors and inflammatory mediators secreted by numerous cell lines play crucial and specialized roles in the healing process, such as angiogenesis, fibroblast proliferation, and wound contraction. To understand and treat a scar, fundamental knowledge of the timeline of wound healing is of critical importance.

The first phase of wound healing, commonly referred to as the inflammatory stage, spans the first 3 to 5 days of healing. In the first few seconds to minutes after a wound occurs, the body instantaneously responds with vasoconstriction and activation of the coagulation cascade.2 This causes platelet aggregation and formation of the fibrin-platelet plug, which not only provides hemostasis, but also provides a platform for the progression of wound healing. After this initial period, vasodilation and increased vascular permeability leads to localized edema and an influx of important inflammatory mediators, which through chemotaxis, cause neutrophil transmigration to the wound site. These neutrophils have an important role in phagocytosis of necrotic tissue and killing of bacterial pathogens. Neutrophils are the dominant cell type around 24 hours, and then undergo apoptosis after resolution of inflammatory stimuli. Macrophages become the predominant cell type around 2 to 3 days and have a decisive role in managing the next step of the inflammatory process by either releasing anti-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors signaling resolution of inflammation and progression of wound healing to the proliferative phase, or by releasing inflammatory cytokines that recruit additional neutrophils and prolong the inflammatory process, causing damage to viable tissue and eventually causing a chronic wound.3 4

The second phase, known as the proliferative phase, lasts approximately 5 to 15 days and is characterized by re-epithelialization, angiogenesis, fibroblast migration, and collagen deposition. Re-epithelialization occurs through proliferation and migration of epithelial cells from the wound edges to the center of the wound at a rate of 0.5 to 1 mm/d until the wound is completely covered and a protective epithelial layer is established. This process can also occur from dermal structures such as sebaceous glands and hair follicles.5 During this proliferative phase, some fibroblasts in the wound secrete disorganized type III collagen, whereas others differentiate into myofibroblasts that cause contraction of the wound.6 Simultaneously, new blood vessels begin forming in poorly perfused wounds with low oxygen tensions. These combined processes form the red granular-appearing tissue made of blood vessels and newly formed connective tissue commonly referred to as “granulation tissue.” To improve the rate of re-epithelialization, maintaining a moist environment has been shown to be significantly beneficial.7

The third and final phase, known as the remodeling phase, lasts up to 1 year and involves collagen cross-linking and replacement of the disorganized type III collagen by organized type I collagen. This remodeling restores the normal dermal composition and provides greater tensile strength to the wound over time. At 6 weeks after wounding, 50% tensile strength of the original skin is regained; at 3 months, 80% is regained, which is the maximum amount able to be salvaged.8

Preoperative Considerations

The effective treatment of the postoperative scar begins in the preoperative period with patient education and management of any underlying medical comorbidities that can impede proper wound healing. A thorough history and physical exam is fundamental in diagnosing and treating any medical problems that can adversely affect postoperative outcomes.

Laboratory values such as prealbumin and albumin are useful in evaluating a patient's nutritional status when interpreted in the right context. Amino acids, fatty acids, vitamins (vitamins C, K, and E), as well as micronutrients (copper, zinc, and iron), all play critical roles in the wound-healing process, and deficiencies in one or all of them can lead to suboptimal results.9 Although the routine measurement of such factors is not warranted, it is something to consider in immunocompromised patients or in patients with chronic, nonhealing wounds. Moreover, inadequate circulation and abnormal vasculature can become problematic as in the case of a lower extremity wound in a patient with peripheral vascular disease, leading to slower re-epithelialization and decreased wound tensile strength.10 11

Systemic diseases can have a significant impact on wound healing. In particular, diabetes mellitus can decrease the inflammatory response to injury and slow epithelialization in addition to causing neuropathy and vasculopathy.12 The measurement of hemoglobin A1c levels may prove useful in evaluating a patient's blood glucose levels and the effectiveness of treatment. Maintaining good glycemic control in the perioperative period is of vital importance.

Medications can increase or decrease the body's ability to heal. Corticosteroids not only decrease the inflammatory response and slow epithelialization, but also impede wound contraction and increase the risk of infection.13 The use of high-dose vitamin A (25,000 IU/d by mouth for 3–10 days) can restore the inflammatory process and re-establish collagen synthesis, although wound contraction will still be impaired and infection risk will still be elevated.14 Chronic corticosteroid use can cause thinning of the dermis, increasing the risk of skin avulsion. It is important to note that suture material holds poorly in this thin skin, and thus is more likely to lead to wound dehiscence.

Finally, drugs and toxins can negatively impact healing. Cigarette smoke contains multiple toxins such as nicotine, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen cyanide that all negatively affect wound healing. Counseling patients on smoking cessation for at least 1 month prior to surgery and at least 1 month postoperatively can lead to more favorable results.

Intraoperative Execution

An ideal surgical incision should have good aesthetic outcome while simultaneously re-establishing soft tissue functionality and structural support. One way of obtaining such results is to plan incisions parallel to or along the length of skin tension lines, or to hide the incision along the border of facial aesthetic units.15 Proper surgical technique and meticulous attention to detail must be utilized intraoperatively. This includes atraumatic handling of the skin and soft tissue, closure of the incision under minimal tension, and eversion of the skin edges on reapproximation. Maintaining hemostasis is crucial intraoperatively to minimize hematoma and seroma formation, both of which can impede wound healing and eventually cause subdermal fibrosis and long-term scar deformity.

Postoperative Interventions

In the early postoperative period, an optimal wound-healing environment must be maintained to allow for the best possible results. Prevention and control of infection remains the key to this process. This begins by creation of a moisture-rich environment for scar formation.

Daily application of antibiotic ointments, such as bacitracin, to the scar not only offers antimicrobial effects, but also has the added benefit of providing moisture to help improve scar outcomes through faster epithelialization. It remains controversial whether these topical agents' antibacterial properties contribute to better scar results or if the benefit in scar appearance is solely attributed to the moisture they provide. The application of a triple antibiotic ointment is usually started immediately after closure of the wound intraoperatively and continued twice daily for 1 to 3 weeks postoperatively.16 17 One drawback to the use of these products is the development of contact dermatitis in some patients that is not seen with petroleum jelly ointments.16 To minimize allergic reaction, some physicians prefer to use an antibiotic ointment for the first week due to its antimicrobial effects then switch to a petroleum jelly ointment for the next 1 to 2 weeks.

Petroleum jelly ointments such as Vaseline (Unilever, Englewood Cliffs, NJ) applied three times daily for 1 to 3 weeks duration or nonadherent petroleum-impregnated gauze such as Xeroform (Kendall/Covidien, Mansfield, MA) placed daily for 1 to 3 weeks are excellent alternatives to maintain wound bed moisture.17 18 Petroleum jelly has the added benefit of reducing scar erythema. Ointments such as Vaseline provide an affordable option with comparable benefits to other more expensive treatments.

Other topical ointments such as vitamin E, vitamin D, cocoa butter, and Mederma (Merz USA, Raleigh, NC) have been used anecdotally in hopes of producing a better scar appearance. Mederma is thought to minimize scar formation through the anti-inflammatory properties of its active ingredient, an onion extract. In younger patients, it may also provide better dermal collagen organization. However, studies have shown no improvement in postoperative scar appearance with the use of these products over petroleum-based ointments and other treatment modalities.18 19 The benefits of these ointments seem to arise from the act of scar massage and from providing moisture to the scar.

After this initial 2- to 3-week period of scar healing where maintaining moisture is the most useful tool in improving wound epithelialization, patients begin experiencing significant reduction in incisional pain and it becomes necessary to educate patients on sun protection as they begin returning to normal activity. Newly formed scars less than 18 months old are highly susceptible to damage from ultraviolet radiation from the sun, causing hyperpigmentation and structural changes to the collagen matrix. This leads to a thickened and discolored scar. Minimizing sun exposure to the scar by covering with clothing or dressing is recommended. In addition, sunscreen with recommended SPF (sun protection factor) of 30 for 12 to 18 months postoperative is essential in protection against damaging ultraviolet radiation and must be worn at all times when the patient is in sunlight. Along with its main benefit of decreasing the risk of developing skin malignancy, sunscreen works to reduce scar hyperpigmentation by preventing melanogenesis, which occurs after ultraviolet light stimulation.

Following the initial 2- to 3-week period of healing, the scar has built enough tensile strength to allow for the initiation of scar massage, which is an effective and cost-efficient technique for scar management. Scar massage leads to a more supple and soft scar through the degradation of excessive and nonpliable collagen. It is important to note that scar massage should not be started until the wound has closed completely. We recommend beginning scar massage approximately 2 to 3 weeks postoperatively and performing twice daily 10-minute massages for a total duration of at least 6 weeks. Scar massage needs to be performed carefully so as to not cause any additional trauma to the closed incision. Applying gentle pressure in a circular motion with the use of petroleum jelly or a lubricating moisturizer during the massage is an effective maneuver in improving outcomes.

Numerous other products are available on the market that can be useful adjuncts to the above-mentioned scar treatments. Silicone gel sheeting is a moisture-protective dressing thought to work by providing the wound with a damp environment conducive to faster epithelialization, while simultaneously decreasing collagen deposition.12 Some studies have shown significant improvements in scar elasticity and appearance with the use of silicone sheets compared with untreated scars. They also soften and reduce scars quicker than pressure dressings. Silicone sheets are frequently used in the treatment of hypertrophic scars. In patients with a history of abnormal scarring, a reduction in the incidence of hypertrophic scars or keloids was seen in some studies.20 Ideally, they should be worn for at least 12 h/d for 3 to 4 months, making sure not to exceed a 6-month total treatment duration as this longer course may negatively affect healing. We advise our patients to wear the silicone sheet in the evening after returning home from work and to remove it before they leave for work in the morning.

Paper tape, such as Micropore (3M, St. Paul, MN) tape or Steri-Strips (3M), is often placed over incision lines postoperatively. These latex-free hypoallergenic paper tapes prevent stretching of the wound by reducing tension on wound edges and minimizing shear forces.21 They have the added benefit of preventing excessive soft tissue formation and thus reducing scar volume, as well as keeping the wound moist by minimizing the formation of scabs. Compared with silicone sheets, Micropore tape produces analogous results with regards to postoperative scar appearance. We recommend placement of paper tape for at least 6 weeks postoperatively.

Pressure dressings are believed to help with scar management through compressive forces that would theoretically disrupt collagen bundles, thus leading to flattening of the scar and prevention of scar hypertrophy. A paucity of evidence exists for pressure dressing utilization in normal postoperative scars; however, some benefit is noted in studies with prolonged treatment periods in the management of keloids and hypertrophic scars.22

More invasive tools also exist for improving scar outcomes. Dermabrasion is a method of skin resurfacing that uses an abrasive device such as a rapidly rotating burr to level the scar surface by removing a controlled thickness of skin and inducing re-epithelialization. Factors affecting depth of skin removal are speed of rotation and coarseness of the burr, amount of pressure applied to the skin, and physical properties of the scar itself. Dermabrasion may be performed at any time once the wound is well-epithelialized, but is typically done 2 to 3 months after surgery to provide optimal improvements in scar appearance. Compared with lasers, dermabrasion is a more cost-effective tool with a lower likelihood of causing skin hyperpigmentation. However, it has the disadvantage of causing skin bleeding with prolonged recovery times lasting up to several weeks.23 24

Low-energy lasers are effective in wound management by stimulating cellular activity, resulting in improved tissue healing and more substantial wound epithelialization.25 Low-energy lasers such as the helium-neon laser and the infrared laser induce varying physiologic processes beneficial to wound healing depending on the wavelength used.26 27 Pulsed dye lasers, on the other hand, have been shown to cause substantial reduction in pruritus during the healing process and some studies note a decrease in scar thickness as well.25 28

If an undesirable scar is still evident, revision surgery can be performed to create an aesthetically pleasing appearance. As scar maturation is a 12- to 18-month process, more conservative treatment modalities should be instituted first before discussion of scar revision. An initial nonsurgical approach to scar management may provide the desired results that would nullify the need for revision surgery. If scar revision is necessary, using the previously mentioned surgical techniques becomes essential in achieving a superior outcome.

Patients often ask about new products marketed directly to consumers through different media outlets such as television ads or the Internet. Given the lack of robust scientific evidence on the majority of these products, it is difficult to determine their true efficacy. Most of these products are based on ingredients shown in some form to be beneficial to wound healing. More research is needed before fully recommending these products. Here, we will describe some of the products that are currently used to improve scarring.

New products such as Prineo (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) have been introduced to the market with promising results. The Prineo Skin Closure System is a flexible, self-adhesive polyester mesh used in full-thickness surgical incisions and is considered equivalent to intradermal sutures with no difference in wound healing according to some studies. This product has the added benefit of providing a much faster skin closure than intradermal sutures.29 The wound margins are reapproximated using the self-adhering mesh, followed by application of the liquid adhesive.

Embrace (Neodyne Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA), a modified silicone sheeting, is another new device on the market. When applied to a scar, it gently contracts and offloads tension, thus minimizing scarring. Studies have shown significant improvements in scar appearance due to this mechanical offloading.27 Embrace is worn for 8 weeks and is typically placed on the scar 2 to 4 weeks after surgery; however, treatment can be initiated up to 6 months after suture removal. An added benefit of this product is its once weekly device replacement, compared with most products that require more frequent and meticulous dressing care.

PracaSil (manufactured by Professional Compounding Centers of America, Houston, TX) is a new topical silicone base that incorporates pracaxi oil, which contains high amounts of fatty acids that are integral to the development of cellular membranes. PracaSil has been shown to be effective in improving scar appearance and symptomology in a case series; however, it remains unclear whether these results are due to its added ingredient or whether they are solely attributed to the moisture delivered by the silicone gel itself, similar to silicone gel sheets.30

Pediatric Wound Care

Although many of the same wound-care products used in adults can be used in children, there are several factors to be considered in this patient population. In infants, the use of tapes and adhesive dressings should be avoided as they can cause blistering and skin tears due to an immature dermal–epidermal bond. If tape must be used, latex-free hypoallergenic paper tape provides the least traumatic effect on the skin.31 Compression bandages are the preferred method for securing a dressing in place. Due to their nonadherent nature, the use of ointments can be very beneficial in providing a moist environment conducive to scar healing in this patient population.

Complications of Wound Healing

Hypertrophic scars are elevated scars, but remain confined to the margins of the incision (Fig. 1). They occur due to moderate collagen overproduction from fibroblasts that show a normal response to growth factor stimulation.32 33 Hypertrophic scars tend to occur earlier in the course of healing, most commonly around the first month, increase in size for several more months, with many improving and regressing spontaneously over time. For this reason, noninvasive therapies that can accelerate this process are used as first-line treatment modalities. The use of silicone gel sheeting may help prevent the development of hypertrophic scars and improve their appearance,34 pressure dressings may aid with scar maturation, and scar massage or pulsed-dye lasers may provide symptomatic relief with itching. Surgical excision, which can be successful in treating hypertrophic scars, is typically reserved for hypertrophic scars that have caused scar contracture or for scars that have failed the above noninvasive therapies. For recurrence after surgical treatment, corticosteroid injection and/or adjuvant therapy with radiation can be used alongside re-excision with potentially favorable outcomes.

Fig. 1.

(A) Hypertrophic scar of left elbow. (B) Hypertrophic scar of left arm.

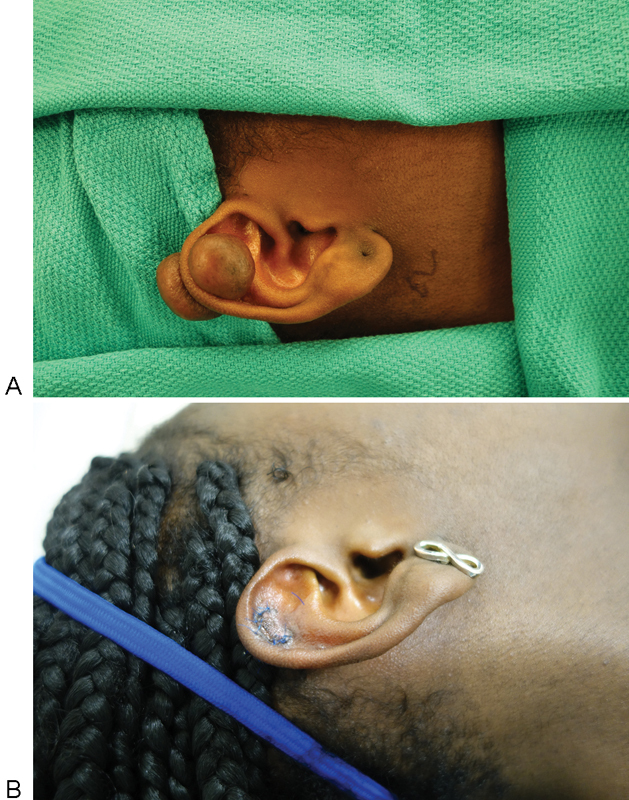

In contrast, keloid scars are characterized by overgrowth of scar tissue beyond the margins of the original incision (Fig. 2). They occur due to high collagen production from fibroblasts that are hyperresponsive to growth factor stimulation.33 Trauma seems to be the most common predisposing factor to the development of keloids, with a high predilection for darkly pigmented skin. Most keloids form within the first year after initial wounding; however, some may begin growing years later. They do not regress spontaneously over time and can continue to grow indefinitely. Keloid scars are extremely difficult to treat and have a high recurrence rate. Noninvasive therapies such as pressure dressings, silicone sheets, and scar massage that are used in treating hypertrophic scars are not as effective for keloids. Corticosteroids, pulsed dye lasers, radiation, and cryotherapy have all been used alone or in conjunction with other treatment options with high recurrence rates. Monotherapy is typically not an effective approach in keloid management and better results are achieved with combination therapy.35 Surgical treatment alone is associated with a high recurrence rate, as high as 100% recurrence in some studies, and thus should be used with adjuvant therapy to provide the best possible success rate. The combination of surgical excision and postoperative radiation has shown promising results in some studies, with recurrence rates as low as 25%.36 37 However, controversy arises regarding the use of radiation in keloids due to the potential for malignant transformation.

Fig. 2.

(A) Preoperative keloid of the right ear. (B) Postoperative result after keloid excision.

Patient education becomes critical when dealing with the treatment of hypertrophic and keloid scars. Patients must be made aware that no treatment modality is guaranteed to provide a definitive cure and that the recurrence rate is highly variable. The key to the effective management of these scar complications is prevention. This is done by first reducing deformational forces on the incision with a tension-free skin closure, applying protective dressings such as paper tape or devices such as Embrace that offload these tensile forces, and advising the patient to minimize trauma to the area from friction, scratching, or stretching of the scar. Prolonged inflammation due to wound colonization and infection can also lead to scar complications along with delays in wound healing and potential incisional dehiscence. It is of vital importance to keep the wound clean by washing the incision and performing routine dressing changes. Well-approximated surgical incisions epithelialize within 1 to 2 days, thus washing a wound may be safely started 48 hours postoperatively and should be done daily thereafter. Scar maintenance therapy such as sun block, scar massaging, scar creams, and silicone sheeting / scar compression should be instituted to optimize outcome.

Conclusion

Numerous therapeutic options are available for postoperative scar management with varying levels of evidence and success rates. Because no single treatment modality emerges as the definitive treatment option in creating the ideal scar, each patient and each wound must be handled uniquely. Optimizing scar appearance is a process that spans from the preoperative period to scar maturation, and regardless of which treatment plan is employed, basic principles of wound care must be maintained.

References

- 1.Broughton G II Janis J E Attinger C E The basic science of wound healing Plast Reconstr Surg 2006117(7, Suppl)12S–34S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furie B, Furie B C. Mechanisms of thrombus formation. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(9):938–949. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0801082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leibovich S J, Ross R. The role of the macrophage in wound repair. A study with hydrocortisone and antimacrophage serum. Am J Pathol. 1975;78(1):71–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Amerongen M J, Harmsen M C, van Rooijen N, Petersen A H, van Luyn M J. Macrophage depletion impairs wound healing and increases left ventricular remodeling after myocardial injury in mice. Am J Pathol. 2007;170(3):818–829. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grotendorst G R, Soma Y, Takehara K, Charette M. EGF and TGF-alpha are potent chemoattractants for endothelial cells and EGF-like peptides are present at sites of tissue regeneration. J Cell Physiol. 1989;139(3):617–623. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041390323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regan M C, Kirk S J, Wasserkrug H L, Barbul A. The wound environment as a regulator of fibroblast phenotype. J Surg Res. 1991;50(5):442–448. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(91)90022-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Field F K Kerstein M D Overview of wound healing in a moist environment Am J Surg 1994167(1A):2S–6S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levenson S M, Geever E F, Crowley L V, Oates J F III, Berard C W, Rosen H. The healing of rat skin wounds. Ann Surg. 1965;161:293–308. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196502000-00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faintuch J, Matsuda M, Cruz M E. et al. Severe protein-calorie malnutrition after bariatric procedures. Obes Surg. 2004;14(2):175–181. doi: 10.1381/096089204322857528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu Q, Wang D, Cui C, Gao Y, Xia G, Cui X. Effects of radiation on wound healing. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 1998;17(2):117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tibbs M K. Wound healing following radiation therapy: a review. Radiother Oncol. 1997;42(2):99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(96)01880-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chow L W, Loo W T, Yuen K Y, Cheng C. The study of cytokine dynamics at the operation site after mastectomy. Wound Repair Regen. 2003;11(5):326–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2003.11503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen I K, Diegelmann R F, Johnson M L. Effect of corticosteroids on collagen synthesis. Surgery. 1977;82(1):15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petry J J. Surgically significant nutritional supplements. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97(1):233–240. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199601000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hom D B, Odland R M. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 2000. Prognosis for facial scarring; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smack D P, Harrington A C, Dunn C. et al. Infection and allergy incidence in ambulatory surgery patients using white petrolatum vs bacitracin ointment. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;276(12):972–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trookman N S Rizer R L Weber T Treatment of minor wounds from dermatologic procedures: a comparison of three topical wound care ointments using a laser wound model J Am Acad Dermatol 201164(3, Suppl)S8–S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baumann L S, Spencer J. The effects of topical vitamin E on the cosmetic appearance of scars. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25(4):311–315. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung V Q, Kelley L, Marra D, Jiang S B. Onion extract gel versus petrolatum emollient on new surgical scars: prospective double-blinded study. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(2):193–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gold M H, Foster T D, Adair M A, Burlison K, Lewis T. Prevention of hypertrophic scars and keloids by the prophylactic use of topical silicone gel sheets following a surgical procedure in an office setting. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27(7):641–644. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atkinson J A McKenna K T Barnett A G McGrath D J Rudd M A randomized, controlled trial to determine the efficacy of paper tape in preventing hypertrophic scar formation in surgical incisions that traverse Langer's skin tension lines Plast Reconstr Surg 200511661648–1656., discussion 1657–1658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costa A M, Peyrol S, Pôrto L C, Comparin J P, Foyatier J L, Desmoulière A. Mechanical forces induce scar remodeling. Study in non-pressure-treated versus pressure-treated hypertrophic scars. Am J Pathol. 1999;155(5):1671–1679. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65482-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim E K Hovsepian R V Mathew P Paul M D Dermabrasion Clin Plast Surg 2011383391–395., v–vi [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith J E. Dermabrasion. Facial Plast Surg. 2014;30(1):35–39. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1363759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manuskiatti W, Fitzpatrick R E. Treatment response of keloidal and hypertrophic sternotomy scars: comparison among intralesional corticosteroid, 5-fluorouracil, and 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed-dye laser treatments. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(9):1149–1155. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.9.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyons R F, Abergel R P, White R A, Dwyer R M, Castel J C, Uitto J. Biostimulation of wound healing in vivo by a helium-neon laser. Ann Plast Surg. 1987;18(1):47–50. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198701000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kana J S, Hutschenreiter G, Haina D, Waidelich W. Effect of low-power density laser radiation on healing of open skin wounds in rats. Arch Surg. 1981;116(3):293–296. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1981.01380150021005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allison K P, Kiernan M N, Waters R A, Clement R M. Pulsed dye laser treatment of burn scars. Alleviation or irritation? Burns. 2003;29(3):207–213. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blondeel P N, Richter D, Stoff A, Exner K, Jernbeck J, Ramakrishnan V. Evaluation of a new skin closure device in surgical incisions associated with breast procedures. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;73(6):631–637. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182858781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banov D, Banov F, Bassani A S. Case series: the effectiveness of fatty acids from pracaxi oil in a topical silicone base for scar and wound therapy. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2014;4(2):259–269. doi: 10.1007/s13555-014-0065-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCord S S, Levy M L. Practical guide to pediatric wound care. Semin Plast Surg. 2006;20:192–199. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Younai S, Nichter L S, Wellisz T, Reinisch J, Nimni M E, Tuan T L. Modulation of collagen synthesis by transforming growth factor-beta in keloid and hypertrophic scar fibroblasts. Ann Plast Surg. 1994;33(2):148–151. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199408000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan K Y Lau C L Adeeb S M Somasundaram S Nasir-Zahari M A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, prospective clinical trial of silicone gel in prevention of hypertrophic scar development in median sternotomy wound Plast Reconstr Surg 200511641013–1020., discussion 1021–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bettinger D A, Yager D R, Diegelmann R F, Cohen I K. The effect of TGF-beta on keloid fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98(5):827–833. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199610000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mustoe T A, Cooter R D, Gold M H. et al. International clinical recommendations on scar management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(2):560–571. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200208000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Norris J E. Superficial x-ray therapy in keloid management: a retrospective study of 24 cases and literature review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95(6):1051–1055. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199505000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones K, Fuller C D, Luh J Y. et al. Case report and summary of literature: giant perineal keloids treated with post-excisional radiotherapy. BMC Dermatol. 2006;6:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]