Abstract

Objective

To assess whether women with a history of hypertensive disease of pregnancy have increased risk for early adult mortality.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, women with one or more singleton pregnancies (1939-2012) with birth certificate information in the Utah Population Database were included. Diagnoses were categorized into gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome, and eclampsia. Women with more than one pregnancy with hypertensive disease (exposed) were included only once, assigned to the most severe category. Exposed women were matched 1:2 to unexposed women by age, year of childbirth, and parity at time of index pregnancy. The causes of death were ascertained using Utah death certificates, and the fact of death was supplemented with the Social Security Death Index. Hazard ratios for cause-specific mortality among exposed women compared to unexposed women were estimated using Cox regressions, adjusting for infant sex, parental education, preterm delivery, race–ethnicity, and maternal marital status.

Results

Sixty thousand five hundred eighty exposed women were matched to 123,140 unexposed women; 4,520 (7.46%) exposed and 6,776 (5.50%) unexposed women were deceased by 2012. All-cause mortality was significantly higher among women with hypertensive disease of pregnancy [adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) 1.65, 95% CI 1.57-1.73]. Exposed women's greatest excess mortality risks were from Alzheimer's disease (aHR 3.44, 95% CI 1.00-11.82), diabetes (aHR 2.80, 95% CI 2.20-3.55), ischemic heart disease (aHR 2.23, 95% CI 1.90-2.63), and stroke (aHR 1.88, 95% CI 1.53-2.32).

Conclusion

Women with hypertensive disease of pregnancy have increased mortality risk, particularly for Alzheimer's disease, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and stroke.

Introduction

Pregnancy has been referred to as a window to future health, because women with certain medical complications of pregnancy are more likely to develop chronic medical problems.1 Specifically, a history of preeclampsia increases a woman's risk of developing chronic hypertension and its sequelae, such as ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral arterial disease.2-6 Several large studies have assessed the association between a previous diagnosis of preeclampsia and the risk of death from cardiovascular disease.7,8

While preeclampsia has been of particular interest as a precursor to chronic illness, there are few data on the long-term health consequences of other hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, such as gestational hypertension, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome, and eclampsia. Likewise, little is known about the risk of morbidity and mortality from non-cardiovascular disease in women with a history of HDP, including long-term adverse maternal neurologic outcomes with inflammatory vascular etiologies such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases.

In order to address these questions, we examined whether women with a history of hypertensive disease of pregnancy had an increased risk for early mortality and determined the most common causes of their deaths.

Materials and Methods

For this retrospective cohort study, we utilized the Utah Population Database to define a cohort of mothers who gave birth from 1939 to 2012. The Utah Population Database has been previously described in detail.9,10 It is a research resource of linked records pertaining to over 8 million individuals that include genealogy records from the Genealogical Society of Utah, official statewide birth and death records, and hospital discharge and ambulatory surgery records from the Utah State Department of Health. The population included in the Utah Population Database is representative of a broad spectrum of the Caucasian United States population and is based largely on founders from Northern and Western Europe. Study approvals were obtained from the Resource for Genetic and Epidemiologic Research, a special review panel that authorizes access to the Utah Population Database, and the University of Utah Institutional Review Board.

Using birth certificate data, we assigned a diagnosis of hypertensive disease of pregnancy and, when possible, the category of disease, to each pregnancy. Reported categories, ordered from least to most severe, included gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome, and eclampsia. When available, inpatient records were hand-reviewed for exposed women. If there was a discrepancy between hypertensive diagnoses listed in the inpatient records compared to the birth certificate, the inpatient record diagnoses were used in place of the birth certificate diagnoses.

Women were included in the study if they had at least one singleton pregnancy with birth certificate data from 1939 to 2012 and lived in Utah for at least one year after delivery. Exposed women were therefore those who had a pregnancy complicated by hypertensive disease of pregnancy. Women with more than one pregnancy complicated by hypertensive disease were included only once, with the index pregnancy chosen using a three-step process: 1) most severe category; 2) same severity but delivered more preterm; or 3) same severity but not delivered preterm with the lowest birth order.

Exposed women were excluded if they had missing data on a key variable (such as missing birth order or maternal age, which would preclude matching to a control), if they died as a result of the pregnancy (maternal mortality) or within 1 year of delivery of other causes, if they did not live in Utah for at least one year after delivery, or if they had documented medical comorbidities at the time of the index pregnancy (chronic hypertension, antiphospholipid syndrome, pregestational diabetes, and chronic kidney disease). Unexposed women were excluded if they had missing data that would preclude matching, if they died as a result of the pregnancy (maternal mortality) or within 1 year of delivery of other causes, if they did not live in Utah for at least one year after delivery, or if the birth or fetal death certificate listed a history of a prior pregnancy complicated by hypertensive disease.

Women with hypertensive disease of pregnancy (exposed) were matched 1:2 to women without hypertensive disease of pregnancy (unexposed) by 5-year age groups, year of childbirth (within 1 year), and parity (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 or more) at the time of the index pregnancy. The date of death was determined using Utah Population Database genealogies, Utah death certificates, or the Social Security Death Index. The Social Security Death Index is a national database, which allowed us to capture deaths for women who had moved out of Utah after their deliveries. Underlying cause of death was ascertained from Utah death certificates based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) version used at the time of death and summarized into broad cause of death categories. Apart from the matching criteria, several important patient confounders at the time of delivery of the index pregnancy were included in the Cox models to generate hazard ratios for mortality among women with all hypertensive disease categories combined as well as specific categories of hypertensive disease. These confounders included infant sex, gestational age at delivery, maternal and paternal education, maternal race–ethnicity, and maternal marital status.

Adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for all-cause mortality and for cause-specific mortality. The broad categories of causes of death were derived by the National Center for Health Statistics, which recognized the need for identifying diseases of public health importance and therefore implemented a standard list of causes of death.11 These broad categories (and their ICD9 codes) include infectious diseases (001-139), neoplasms (140-239), endocrine/nutritional/metabolic diseases (240-279), diseases of blood and blood-forming organs (280-289), mental disorders (290-319), nervous system disorders (320-389), circulatory system disease (390-459), respiratory system disease (460-519), digestive system disease (520-579), genitourinary disease (580-629), musculoskeletal and connective tissue disease (710-739), ill-defined diseases (780-799), and external causes (E800-E999).11

We included all women identified with a diagnosis of hypertensive disease of pregnancy during the study period for the Utah population that met our inclusion criteria. Hypothesis tests were based on a type I error of <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

We evaluated 2,083,331 eligible pregnancies, which included 60,580 (2.9%) distinct women with hypertensive disease of pregnancy (includes 28,894 gestational hypertension; 26,184 preeclampsia; 806 HELLP syndrome; 1,030 eclampsia) in at least one pregnancy. These women were matched to 123,140 women with no history of hypertensive disease in any pregnancies in the Utah Population Database. Baseline characteristics were compared between women with and without hypertensive disease at the time of the index pregnancy, and women with hypertensive disease of pregnancy were significantly more likely to be non-black, to have younger paternal age, to deliver at an earlier gestational age, to deliver a neonate with lower birth weight, to have fewer total children, to have lower maternal and paternal Nam-Powers socioeconomic scores (a census-derived score relating to occupation), and to have fewer years of maternal education (Table 1). A total of 11,296 women were deceased as of 2012: 4,520 (7.46%) exposed and 6,776 (5.50%) unexposed. Table 2 describes the number of deaths among exposed and unexposed women during each time period.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of exposed and unexposed women at time of index pregnancy.

| Variable | Exposed Women (n=60,580) | Unexposed Women (n=123,140) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Year of childbirth | 1995 ± 16 | 1995 ± 16 | 0.65 |

|

| |||

| Maternal age (years) | 26.0 ± 5.9 | 26.0 ± 5.9 | 0.84 |

|

| |||

| Maternal birth year | 1969 ± 16 | 1969 ± 16 | 0.54 |

|

| |||

| Maternal ethnicity [n (%)] | |||

| Black | 452 (0.3) | 737 (0.4) | <0.01 |

| Hispanic | 7,110 (3.9) | 14,671 (8.0) | 0.27 |

| Caucasian | 57,688 (31.4) | 117,307 (63.9) | 0.72 |

|

| |||

| Paternal age (years) | 28.5 ± 6.4 | 28.6 ± 6.5 | <0.01 |

|

| |||

| Paternal birth year | 1966 ± 17 | 1966 ± 17 | 0.24 |

|

| |||

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 37.9 ± 2.6 | 38.9 ± 1.9 | <0.01 |

|

| |||

| Birth weight (g) | 3072 ± 700 | 3316 ± 512 | <0.01 |

|

| |||

| Birth order [median (IQR)] | 1.0 (1.0-2.0)) | 1.0 (1.0-2.0) | 0.25 |

|

| |||

| Total number of children [median (IQR)] | 3.0 (2.0-4.0) | 3.0 (2.0-4.0) | <0.01 |

|

| |||

| Maternal Nam-Powers score | 49.4 ± 24.2 | 50.1 ± 24.6 | <0.01 |

|

| |||

| Paternal Nam-Powers score | 52.4 ± 24.3 | 54.8 ± 24.9 | <0.01 |

|

| |||

| Maternal education years | 13.1 ± 2.2 | 13.3 ± 2.3 | <0.01 |

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise specified.

Table 2. Number of deaths among exposed and unexposed women with index pregnancy during each time period.

| Year(s) | Exposed Women (n=60,580) | Unexposed Women (n=123,140) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Deceased | Total | Deceased | |

| 1939 | 61 | 57 (93.4%) | 122 | 109 (89.3%) |

| 1940-1949 | 1328 | 1111 (83.7%) | 2672 | 2108 (78.9%) |

| 1950-1959 | 2117 | 1304 (61.6%) | 4293 | 2143 (49.9%) |

| 1960-1969 | 2066 | 703 (34.0%) | 4245 | 950 (22.4%) |

| 1970-1979 | 2083 | 259 (12.4%) | 4210 | 303 (7.2%) |

| 1980-1989 | 8335 | 480 (5.8%) | 16375 | 575 (3.4%) |

| 1990-1999 | 14346 | 291 (2.0%) | 29342 | 371 (1.3%) |

| 2000-2012 | 30244 | 164 (0.5%) | 61521 | 195 (0.3%) |

Data presented as n or n (%).

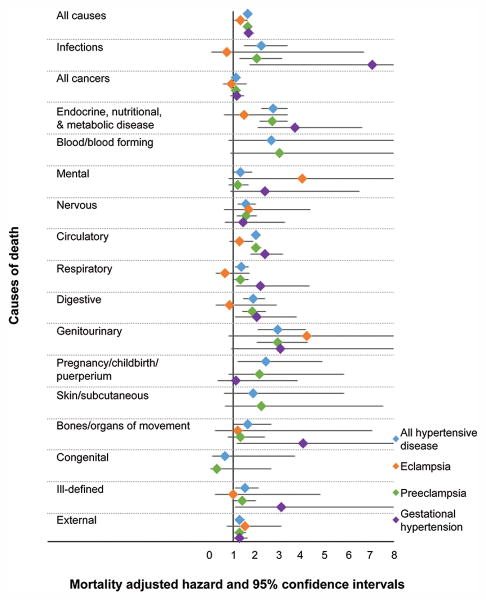

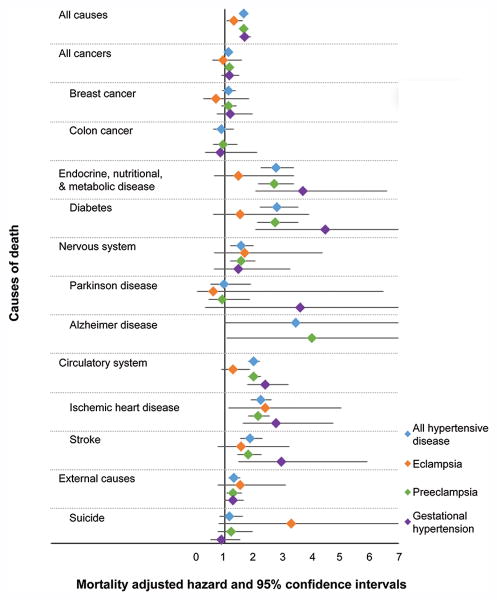

All-cause mortality was significantly increased among women with hypertensive disease of pregnancy compared to women without (aHR 1.65, 95% CI 1.57-1.73) (Figure 1). Exposed women were also at significantly increased risk of cause-specific mortality from each category of causes examined, with the exception of diseases of blood and blood-forming organs, mental diseases, diseases of skin and subcutaneous tissue, and congenital causes. Within these categories, exposed women were at significantly increased risk of death from Alzheimer's disease (aHR 3.44, 95% CI 1.004-11.82), diabetes (aHR 2.80, 95% CI 2.20-3.55), ischemic heart disease (aHR 2.23, 95% CI 1.90-2.63), and stroke (aHR 1.88, 95% CI 1.53-2.32) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Forest plot illustrating risks of general causes of mortality for women with each category of hypertensive disease of pregnancy compared to matched women without hypertensive disease of pregnancy. Created by Jennifer West.

Figure 2.

Forest plot illustrating risks of specific causes of mortality for women with each category of hypertensive disease of pregnancy compared to matched women without hypertensive disease of pregnancy. Created by Jennifer West.

When women with any hypertensive disease of pregnancy were divided into specific subtypes of hypertensive disease, we found that hazard ratios for mortality varied by type of hypertensive disease. Women with a history of eclampsia had a significantly increased risk of death from ischemic heart disease (aHR 2.39, 95% CI 1.14-5.03), but other causes did not have a statistically significant increased risk (Figures 1 and 2).

Women with a history of preeclampsia had significantly increased risk for death from genitourinary disease (aHR 2.95, 95% CI 2.04-4.26); endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic disease (aHR 2.71, 95% CI 2.16-3.39); infectious disease (aHR 2.03, 95% CI 1.30-3.16); circulatory disease (aHR 2.01, 95% CI 1.81-2.23); digestive disease (aHR 1.85, 95% CI 1.40-2.45); nervous system disease (aHR 1.57, 95% CI 1.19-2.06); respiratory disease (aHR 1.34, 95% CI 1.06-1.69); external causes (aHR 1.30, 95% CI 1.06-1.59); and all cancers (aHR 1.15, 95% CI 1.03-1.30) (Figure 1). Within these categories, women with a history of preeclampsia had a significantly increased risk of death from Alzheimer's disease (aHR 4.02, 95% CI 1.08-14.99), diabetes (aHR 2.75, 95% CI 2.13-3.56), ischemic heart disease (aHR 2.16, 95% CI 1.82-2.57), and stroke (aHR 1.82, 95% CI 1.45-2.28) (Figure 2).

Women with a history of gestational hypertension had significantly increased risk of death from infectious disease (aHR 7.04, 95% CI 1.73-28.65); musculoskeletal disease (aHR 4.04, 95% CI 1.17-13.94); endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic disease (aHR 3.70, 95% CI 2.07-6.61); ill-defined causes (aHR 3.12, 95% CI 1.11-8.79); circulatory disease (aHR 2.39, 95% CI 1.78-3.21); respiratory disease (aHR 2.21, 95% CI 1.13-4.34); digestive disease (aHR 2.04, 95% CI 1.11-3.77); and external causes (aHR 1.29, 95% CI 1.01-1.66) (Figure 1). Within these categories, women with a history of gestational hypertension had a significantly increased risk of death from diabetes (aHR 4.48, 95% CI 2.05-9.77), stroke (aHR 2.97, 95% CI 1.49-5.92), and ischemic heart disease (aHR 2.77, 95% CI 1.62-4.75) (Figure 2).

The number of women with a history of HELLP syndrome (n=806) who died was very small (8 deaths), presumably because this diagnosis was first described in 1982, and this group of women was therefore relatively young. Because calculations performed within this group yielded relatively unstable results, the results for this group have not been included here. The number with eclampsia (n=1,030) was of similar size but had many more deaths (226). The diagnosis of eclampsia has been available since 1939, allowing a much longer period of time in which to observe their mortality.

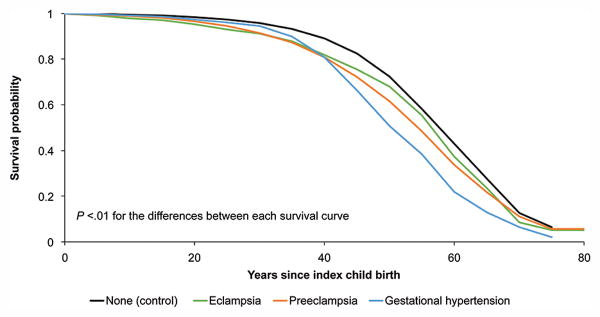

Figure 3 presents survival curves in years after the index pregnancy for women with each category of HDP.

Figure 3.

Survival curves for survival probability by years since index pregnancy for each category of hypertensive disease of pregnancy compared to women without hypertensive disease of pregnancy. The survival curves for each category of exposed women were significantly different from that for unexposed women and from each other (P value for all <.01). Created by Jennifer West.

Discussion

We found that hypertensive disease of pregnancy is associated with significantly increased risk for all-cause and some cause-specific mortality. We also found that the most common causes of death vary among women with a history of different categories of hypertensive disease of pregnancy. Some of these causes, such as ischemic heart disease and stroke, are expected given the involvement of endothelium in the pathophysiology of hypertensive disease of pregnancy.12,13 Likewise, the association of hypertensive disease of pregnancy with diabetes has also been described.14 However, the significantly increased risk of death from Alzheimer's disease among women with a history of preeclampsia is a notable new finding.

This association is plausible. Impaired cognitive functioning has been reported among women with a history of preeclampsia or eclampsia for several years postpartum.15,16 Preeclampsia and dementia share common cardiovascular risk factors, such as higher body mass index, higher blood pressure, and unfavorable lipid levels.17 Upregulation of STOX1 gene activity has been reported both in placentas of pregnancies affected by preeclampsia and in brains affected by late-onset Alzheimer's disease.18 The presence of amyloid precursor protein in the placentas and sera of women with preeclampsia has also been documented, suggesting a shared pathophysiology involving abnormal protein folding and aggregation.19 This association warrants further investigation and replication, particularly for morbidity rather than strictly mortality events.

We have demonstrated that women with all categories of hypertensive disease of pregnancy are at increased risk for adult mortality, with the most common causes of death varying according to the type of hypertensive disease. It is interesting to note that women with gestational hypertension, which is generally considered to be a more mild form of hypertensive disease of pregnancy, had a higher risk of death from diabetes compared to women with preeclampsia and eclampsia. Women with gestational hypertension also appear to have earlier mortality on the survival curve compared to women with preeclampsia and eclampsia. It may be that some women diagnosed with gestational hypertension actually had chronic hypertension, although we would also expect that this may be true for women with preeclampsia. A separate analysis of mortality risk among women with a history of recurrent hypertensive disease of pregnancy is planned.

Limitations of our study include the retrospective design, with the potential for inconsistency between providers over time in assigning a diagnosis of a specific category of hypertensive disease of pregnancy. By confirming birth certificate diagnoses with inpatient records when available, we attempted to limit this inconsistency. Residual misclassification of hypertensive diagnoses should trend our results toward the null, effectively underestimating the magnitude of our positive findings rather than erroneously yielding positive findings. Additional limitations include potential for selection bias and residual confounding from important potential confounders such as obesity, substance use, and the subsequent development of chronic hypertension (data which were not available using our data sources). We hoped to minimize these threats to validity by including all women meeting inclusion criteria during the study period, matching on key confounders for which we had data, and utilizing multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression models to control for potential confounding variables. Our study population was limited to women who had at least one viable pregnancy while residing in the state of Utah. Although Utah is becoming more racially and ethnically diverse, it remains predominantly white and non-obese. This may limit the generalizability of our findings to other patient populations. Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that women may have had one or more pregnancies outside the state of Utah or that such pregnancies might have been complicated by hypertensive disease. We excluded all women with prior hypertensive disease mentioned on a birth certificate, which minimized but did not resolve this limitation; however, there is no reason to believe that this factor would be more or less common in our exposed or unexposed populations.

Strengths of our study include use of a large population-based sample and retrospective study design allowing us to study the association between hypertensive disease of pregnancy and mortality in a large population of women over many years. The observed long-term health outcomes after hypertensive disease of pregnancy are meaningful from a public health perspective, and highlight the significance of a history of hypertensive disease of pregnancy for healthcare providers who follow these women in subsequent pregnancies and beyond their childbearing years. Women with a history of hypertensive disease of pregnancy may be targeted for early and intensive screening and, where possible, interventions such as diet and lifestyle modifications or pharmacologic therapy in order to improve long-term health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jennifer West for creating the figures for the manuscript.

Alison Fraser, Michael Hollingshaus and Ken Smith were supported by R01AG022095 (Early Life Conditions, Survival, and Health: A Pedigree-Based Population Study) (PI Smith). Michael Varner is supported by NIH/NCATS 1UL1TR001067 and by the HA and Edna Benning Presidential Endowment.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Presented at the 2016 Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Annual Meeting, February 1–6, 2016, Atlanta, Georgia.

References

- 1.Carson MP. Society for maternal and fetal medicine workshop on pregnancy as a window to future health: Clinical utility of classifying women with metabolic syndrome. Semin Perinatol. 2015;39(4):284–289. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sandvik MK, Hallan S, Svarstad E, Vikse BE. Preeclampsia and prevalence of microalbuminuria 10 years later. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(7):1126–1134. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10641012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghossein-Doha C, Peeters L, van Heijster S, et al. Hypertension after preeclampsia is preceded by changes in cardiac structure and function. Hypertension. 2013;62(2):382–90. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breetveld NM, Ghossein-Doha C, van Kuijk S, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk is only elevated in hypertensive, formerly preeclamptic women. BJOG. 2015;122(8):1092–1100. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonald SD, Malinowski A, Zhou Q, Yusuf S, Devereaux PJ. Cardiovascular sequelae of preeclampsia/eclampsia: A systematic review and meta-analyses. American Heart Journal. 2008;156(5):918–930. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaugler-Senden IPM, Berends AL, de Groot CJM, Steegers EAP. Severe, very early onset preeclampsia: Subsequent pregnancies and future parental cardiovascular health. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2008;140(2):171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cirillo PM, Cohn BA. Pregnancy complications and cardiovascular disease death: 50-year follow-up of the Child Health and Development Studies Pregnancy Cohort. Circulation. 2015;132:1234–1242. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mongraw-Chaffin ML, Cirillo PM, Cohn BA. Preeclampsia and cardiovascular disease death: prospective evidence from the Child Health and Development Studies Cohort. Hypertension. 2010;56(1):166–171. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esplin MS, Fausett MB, Fraser A, et al. Paternal and maternal components of the predisposition to preeclampsia. NEJM. 2001;344(12):867–872. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103223441201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerber RA, O'Brien E. A cohort study of cancer risk in relation to family histories of cancer in the Utah population database. Cancer. 2005;103(9):1906–1915. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heron M. Deaths: Leading causes for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(10) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schokker SAM, Van Oostwaard MF, Melman EM, et al. Cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, and renal hypertensive disease after hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2015;5(4):287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amaral LM, Cunningham MW, Jr, Cornelius DC, LaMarca B. Preeclampsia: long-term consequences for vascular health. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2015;11:403–415. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S64798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Libby G, Murphy DJ, McEwan NF, et al. Pre-eclampsia and the later development of type 2 diabetes in mothers and their children: an intergenerational study from the Walker cohort. Diabetologia. 2007;50(3):523–530. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0558-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brusse I, Duvekot J, Jongerling J, Steegers E, De Koning I. Impaired maternal cognitive functioning after pregnancies complicated by severe pre-eclampsia: a pilot case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87(4):408–412. doi: 10.1080/00016340801915127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aukes AM, Wessel I, Dubois AM, Aarnoudse JG, Zeeman GG. Self-reported cognitive functioning in formerly eclamptic women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(4):365 e361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beeri MS, Ravona-Springer R, Silverman JM, Haroutunian V. The effects of cardiovascular risk factors on cognitive compromise. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(2):201–212. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.2/msbeeri. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Dijk M, van Bezu J, Poutsma A, et al. The pre-eclampsia gene STOX1 controls a conserved pathway in placenta and brain upregulated in late-onset Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19(2):673–679. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng S, Nakashima A, Sharma S. Understanding pre-eclampsia using Alzehimer's etiology: an intriguing viewpoint. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2016;75(3):372–81. doi: 10.1111/aji.12446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.