Abstract

Background/Objectives

The reasons for changing epidemiology of acute pancreatitis (AP) are poorly defined. We hypothesized that trends for severity, case-fatality and population mortality from AP will provide an insight into the rising burden of AP in the population. We evaluated trends in the hospitalizations, case-fatality, severity and population mortality related to AP in the US population.

Study

We used the National Hospital Discharge Survey to calculate age, sex and race standardized hospitalizations of and case-fatality rates for AP, and Vital Statistics to calculate AP-related population mortality from 1983–2010, using 2010 US census as the reference.

Results

Number of discharges per 100,000 population with primary diagnosis of AP increased 2 times from 42.4 (95% CI 38.2–46.5) during 1983–1986 to 85.4 (95% CI 62.8–108.1) during 2007–2010. During corresponding intervals, case-fatality from AP decreased 62% from 2.02% (95% CI 2.01–2.04) to 0.79% (95% CI 0.78–0.80), but population mortality per million population due to AP as primary cause remained stable from 9.28 (95% CI 8.94–9.62) to 9.91 (95% CI 9.56–10.26), and from AP as any cause decreased significantly (but only 12%) from 20.87 (95% CI 20.36–21.38) to 18.48 (95% CI 18.00–18.96). Prevalence of severe AP increased from 5% (95% CI 4.95–5.05%) during 1991–1994 to 9.78% (95% CI 9.73–9.83%) during 2007–2010.

Conclusion

An increasing prevalence of severe disease suggests true population increase to be an important contributor to the rising incidence of AP. A lack of proportional increase in population mortality suggests the impact of medical advances in the evaluation and management of AP.

Keywords: pancreatitis, trend, incidence, mortality, severity

Introduction

Studies from several populations have documented a progressive increase in the incidence of acute pancreatitis (AP) over the last 3–4 decades1–4. The number of discharges with a primary inpatient diagnosis of AP in the United States has almost doubled from 1988 to 20095, 6. In fact, AP is now the most common gastrointestinal cause of hospital admissions in the US6. The exact cause of rising incidence of AP is unclear. Increasing obesity (leading to an increase in gallstone disease and gallstone-related AP) and increased detection due to wide availability and routine performance of serum pancreatic enzymes to evaluate abdominal pain are speculated to be the main reasons7.

Corresponding to the rising incidence rates, a progressive decline in case-fatality of AP has been observed3, likely from advances in management (e.g. better intensive care treatment, optimization of the timing and type of interventions needed in the setting of local complications, etc.). However, the use of case-fatality to assess the impact of treatment on AP-related mortality has limitations. Patients with mild AP have a lower likelihood of adverse outcomes or death8. If increased detection is contributing to the rising incidence9, then decreasing case-fatality can be explained merely by a higher prevalence of mild disease among patients diagnosed with AP. Case-fatality can also decrease from improvement in management by enabling patients with severe AP to survive the index hospitalization. Case-fatality however would not capture delayed mortality occurring from local or systemic complications for which patients may or may not get readmitted. To better analyze trends for AP related mortality, evaluating all deaths related to AP in the population would be an unbiased approach.

We hypothesized that a true increase in the disease is an important contributor to the rising burden of AP, and that trends for severity, case-fatality and population mortality from AP will provide an insight into the rising burden of AP in the population. To test this hypothesis we used the National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS), a nationally representative inpatient dataset in the US to evaluate trends in the number of discharges, case-fatality and disease severity of AP. Furthermore, we used data from Vital Statistics to evaluate trends in the population mortality from AP. Together, these analyses provide a unique perspective of the epidemiologic trends of AP.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh.

Data Source

National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS)

The NHDS is a national probability sample survey conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) since 1965. NHDS utilizes a stratified, multi-stage probability design which involves probability samples of primary sampling units (PSUs) from the National Health Interview Survey sample (stage I), short-stay nonfederal hospitals (whose mean days of care is less than 30 days) within PSUs (stage II), and a sample of discharges within hospitals (stage III). A two-stage sampling plan was followed till 1987 and from 1988 onwards a three-stage sampling plan was implemented.

NHDS reports hospitalizations according to demographic characteristics, medical conditions and other features. It covers discharges from non-institutional hospitals, exclusive of Federal, Military, and Veterans Administration hospitals, located in 50 States and District of Columbia with the average number of hospitals participating per year of roughly 500 with over 300,000 discharges sampled per year. Data collection (manual and automatic) is performed by trained staff of National Center for health Statistics (NHCS) or by the hospitals. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) is used for classifying medical diagnosis. National estimates are generated using multistage estimation procedure which involved three components: inflation by reciprocals of the sampling selection probabilities, adjusting for non-response and population weighting ratio adjustments. The population weighting adjustments are made to adjust for the oversampling or under sampling of discharges reported in the sampling frame for the data year. The adjustment is a multiplicative factor that has as its numerator the number of admissions reported for the year at sampling frame hospitals within each region-specialty-size group and its denominator the estimated number of those admissions for that same hospital group10.

Vital Statistics

The National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) is an inter-governmental data sharing mechanism by which NCHS collects and disseminates the Nation’s official vital statistics. Vital registration systems operating in various jurisdictions in contract with NCHS collect registration of vital events like births, deaths, marriages, divorces and fetal deaths. Mortality data from NVSS are the main source for demographic, geographic and cause-of-death information.

For this study, data was extracted from Center for Disease Control Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (CDC WONDER) from 1983–2010 for deaths where AP was listed as the primary or any cause of death (ICD-9: 577.0, ICD-10: K85). CDC WONDER captures actual number of deaths year each, hence the numbers and mortality rates from AP are reported without any population weight estimate calculations11, 12.

Census Data

The US Population and Housing census is collected by the United States Census Bureau every 10 years. The last census was conducted in 2010. Information on the census is publically available and can be downloaded from the US Census Bureau website using the American Fact Finder tool13. For this study, 2010 Census was used as the reference population for estimating all discharge and population mortality rates for AP.

Years of Study

For the current study, we compiled data from the three sources for years 1983–2010. Year 1983 was chosen as the start of the study period due to inconsistencies in the reporting for the Race variable prior to 1982 and to allow for the study of trends in 4 year intervals. Race was categorized race into White, Black and Other for the dataset.

Cases and outcomes of interest

We identified all discharges in the NHDS with a primary diagnosis of AP (ICD-9 577.0). Information for inpatient hospital death was obtained from the discharge status. Case-fatality was defined as the proportion of inpatient hospital deaths among patients with a diagnosis of AP. As reported previously14, disease severity was as defined as the presence of any one of the following: in-hospital deaths, presence of associated diagnostic or procedure codes for renal failure, respiratory failure, sepsis, intra-abdominal infections, use of vasopressin or activated drotrecogin alfa and abdominal surgery for complications of pancreatitis (see Appendix for codes used). Due to availability of relevant associated codes, disease severity classification was applied only for discharges from 1991 onwards. NHDS data documentation was reviewed and any modifications to the codes during the study period were taken into consideration for calculation of disease severity. Deaths where AP was listed as the primary or any cause of death in the vital statistics dataset were identified to determine population mortality from AP.

Statistics

We calculated the estimated number of discharges, overall and for each year with primary and any discharge diagnosis of AP during 1983–2010 from the NHDS database using weighted frequencies. Weighted frequencies were obtained by using SAS PROC SURVERYFREQ with weight option. Case-fatality rate was determined as the fraction of patients with a primary or any diagnosis of AP who died during the hospitalization.

To calculate the discharge and population mortality rates, we considered the entire US population during the study to be at risk. We calculated the crude discharge per 100,000 and population mortality rates per 1,000,000 population for the entire study period, each year and by intervals (see below). We adjusted the rates by age and sex to the 2010 US population using direct standardization and calculated the 95% confidence intervals (CI) using Poisson distribution. Rates were also calculated for discharges and population mortality and after stratification by age, sex and race. Severe AP is represented as the proportion of AP patients who had associated codes for severe disease or those who died during the hospitalization.

Due to fluctuations in the number of patients, especially after stratification of data by subgroups, we analyzed the data using successive 4-year intervals (e.g. 1983–1986, onwards) and decades (1983–1990, 1991–2000, and 2001–2010). Statistical significance for trends was determined by using Kendall Tau-b test for 4-year intervals, and the overlap of 95% CI’s of the estimates. Any estimate <30 and relative standard error of more than 30% from NHDS is considered to be unreliable and was not reported in this study. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Number of discharges and discharge rates

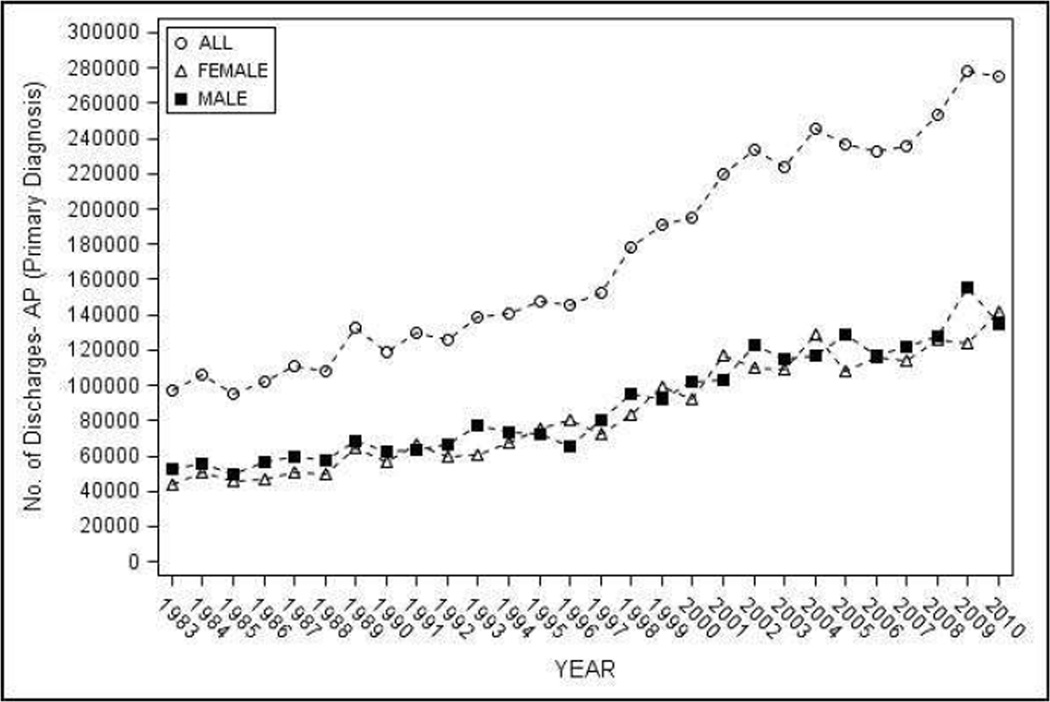

The estimated number of discharges with a primary inpatient diagnosis of AP in the NHDS during 1983–2010 was 4,854,189. The number of discharges increased ~3 times from 97,029 in 1983 to 275,613 in 2010 (Figure 1a).

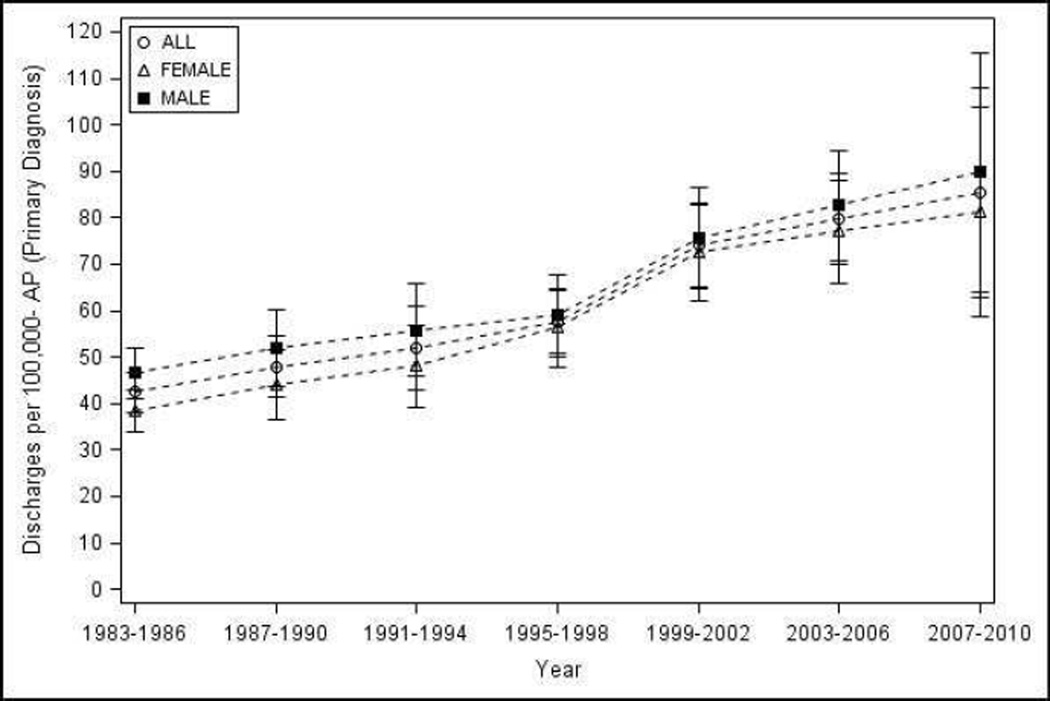

Figure 1.

Hospital discharges with AP as the primary diagnosis in the United States from 1983–2010 - a) Number of discharges, overall and by sex; b) age and sex adjusted discharges overall, and age adjusted discharges by sex

Trends for age and sex adjusted estimated discharges with a primary inpatient diagnosis of AP per 100,000 population by 4 year and 10 year intervals is shown in Figure 1b and Table 1. The discharge rate doubled from 42.4 (95% CI 38.2–46.5) during 1983–1986 to 85.4 (95% CI 62.8–108.1) during 2007–2010 (p-trend <0.002), and increased 1.8 times from 45.2 (95% CI 39.0–51.3) during 1983–1990 to 82.0 (95% CI 60.3–103.7) from 2001–2010. In subset analyses, a significant increase in the discharge rate was seen for both sexes, age groups 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, and 55–64, whites and other race on trend analyses (p-trend <0.05). Subgroup analyses were also significant when evaluated by overlap of 95% CI for whites, and age groups 25 thru 64 years for 4-year but not 10-year intervals. Discharge rates increased with age and were higher in males (vs. females), blacks (vs. whites).

Table 1.

Hospital Discharges with a primary diagnosis of Acute Pancreatitis in the National Hospital Discharge Survey from 1983–2010

| Group | Rate per 100,000 persons (95% CI)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1983–1990 | 1991–2000 | 2001–2010 | |

| All | 45.17 (39.00, 51.33) |

57.77 (47.72, 67.82) |

82.00 (60.29, 103.73) |

| Male | 49.27 (41.32, 57.22) |

60.27 (49.61, 70.94) |

85.19 (60.71, 109.67) |

| Female | 41.27 (34.11, 48.43) |

55.38 (45.16, 65.60) |

78.93 (56.95, 100.92) |

| White | 34.28 (28.82, 39.73) |

40.80 (31.71, 49.90) |

56.70 (38.55, 74.84) |

| Black | 84.71 (65.70, 103.71) |

90.66 (65.37, 115.95) |

105.16 (66.00, 144.33) |

| Other | 43.43 (25.96, 60.91) |

46.89 (20.98, 72.80) |

65.40 (31.97, 98.83) |

| Age 0–24 | 8.85 (5.71, 12.00) |

8.30 (4.36, 12.24) |

14.11 (7.54, 20.67) |

| Age 25–34 | 37.24 (26.30, 48.18) |

45.06 (31.01, 59.12) |

65.56 (41.87, 89.25) |

| Age 35–44 | 61.71 (49.01, 74.42) |

77.44 (59.06, 95.82) |

113.37 (76.00, 150.75) |

| Age 45–54 | 72.89 (58.65, 87.13) |

92.79 (71.16, 114.42) |

127.03 (86.35, 167.71) |

| Age 55–64 | 70.58 (55.88, 85.28) |

92.52 (70.44, 114.59) |

124.26 (82.14, 166.38) |

| Age +65 | 109.88 (90.06, 129.69) |

132.70 (104.19, 161.21) |

164.18 (114.45, 213.91) |

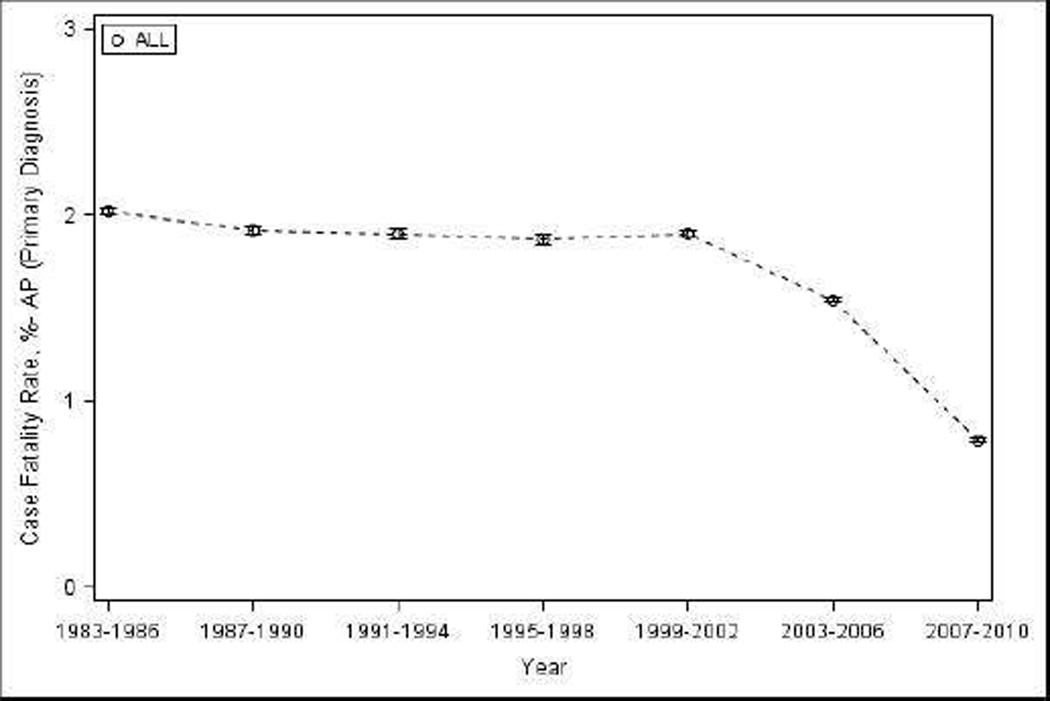

Case-fatality

The estimated in-hospital deaths during 1983–2010 in the NHDS dataset for primary diagnosis of AP were 77,769 resulting in an overall case fatality rate of 1.60% (95% CI 1.59–1.61). Case-fatality steadily decreased 62% during the study period from 2.02% (95% CI 2.01–2.04) during 1983–1986 to 0.79% (95% CI 0.78–0.80) during 2007–2010 (p-trend 0.004) (Figure 2) and 36% from 1.97% (95% CI 1.94–1.99) during 1983–1990 to 1.26% (95% CI 1.24–1.28) during 2001–2010 (Table 2). Overall, the case-fatality was significantly higher in males (vs. females) and in Blacks (vs. Whites). A significant reduction in case-fatality was observed for both sexes, whites, and in the elderly in whom the drop in case-fatality was the most impressive, from 4.37% (95% CI 4.31–4.43) during 1983–1990 to 2.34% (95% CI 2.29–2.39) during 2001–2010 (Table 2). A significant decrease in case-fatality was seen for 4-year intervals for whites [2.51% (95% CI 2.48–2.53) to 0.80% (95% CI 0.79–0.82)] and the elderly [4.86% (95% CI 4.81–4.90) to 1.30% (95% CI 1.27–1.33)] (p-trend <0.05). For other subgroups, due to low figures, reliable estimates could not be generated.

Figure 2.

Case-fatality for AP in the United States from 1983–2010

Table 2.

Case-fatality in admissions with a primary diagnosis of Acute Pancreatitis in the National Hospital Discharge Survey from 1983–2010

| Group | Percentage (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1983–1990 | 1991–2000 | 2001–2010 | |

| All | 1.97 (1.94–1.99) |

1.93 (1.90–1.96) |

1.26 (1.24–1.28) |

| Male | 2.07 (2.02–2.12) |

2.10 (2.06–2.13) |

1.52 (1.49–1.56) |

| Female | 1.85 (1.82–1.88) |

1.76 (1.73–1.79) |

0.99 (0.96–1.02) |

| White | 2.41 (2.38–2.43) |

2.16 (2.13–2.19) |

1.15 (1.13–1.16) |

| Black | - | - | 1.23 (1.21–1.26) |

| Other | - | - | - |

| Age 0–24 | - | - | - |

| Age 25–34 | - | - | - |

| Age 35–44 | - | - | - |

| Age 45–54 | - | - | 0.95 (0.91–0.99) |

| Age 55–64 | - | - | 1.82 (1.77–1.86) |

| Age +65 | 4.37 (4.31–4.43) |

4.05 (3.98–4.11) |

2.34 (2.29–2.39) |

Unweighted estimates < 30 were not reported

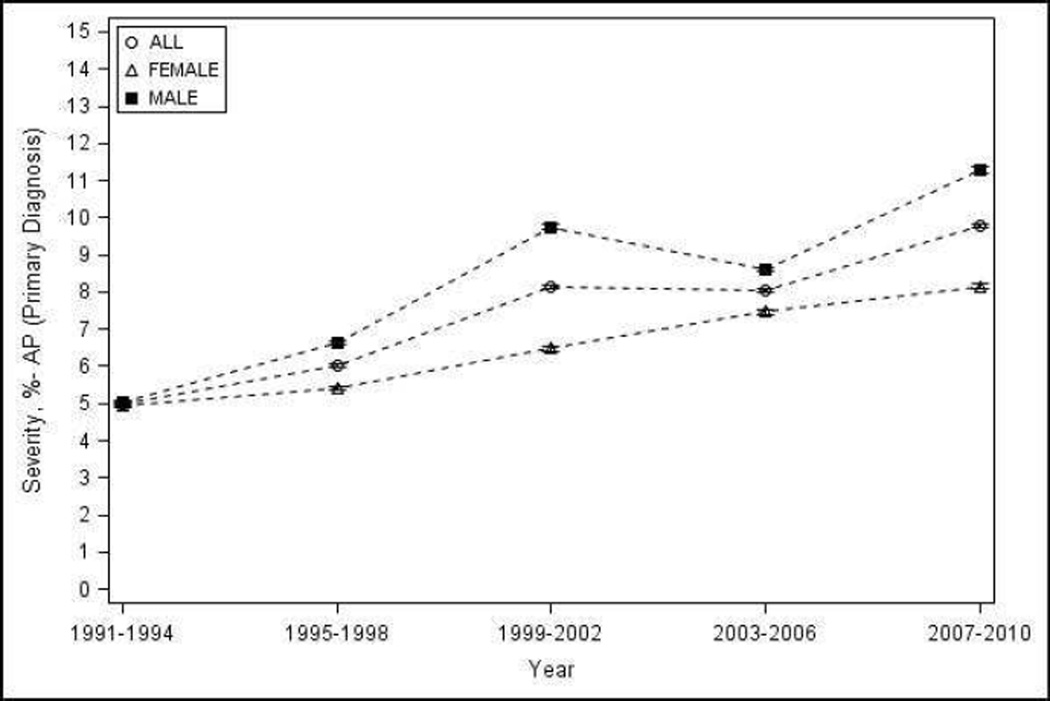

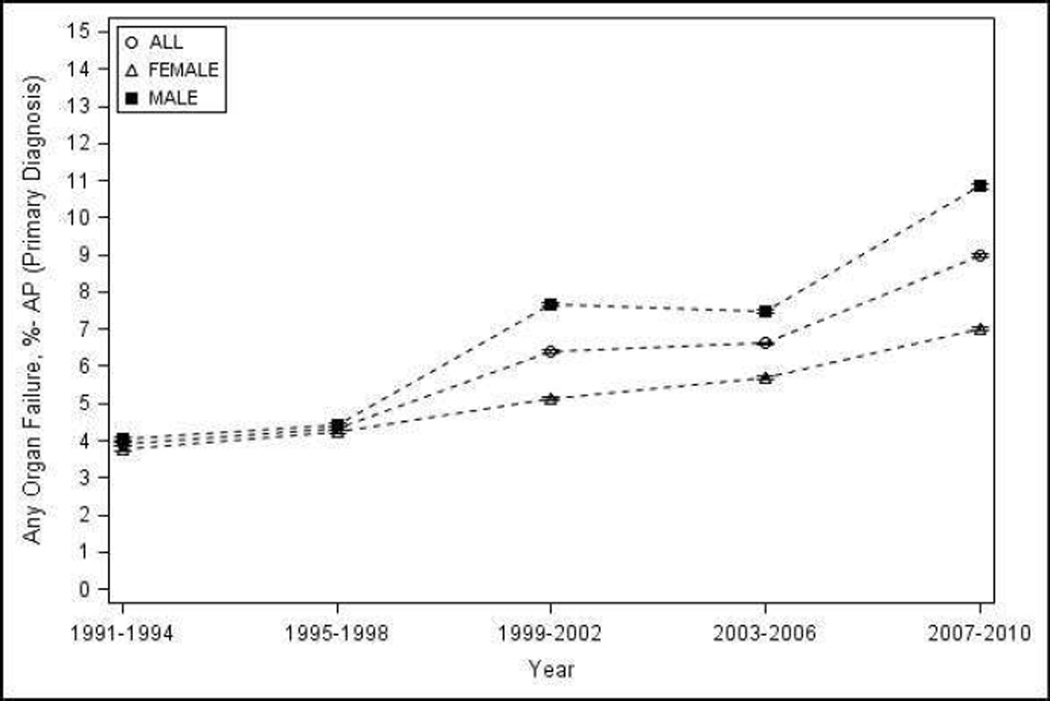

Severe AP

Overall, the percentage of patients with any organ failure increased from 3.92% (95% CI 3.88–3.96) during 1991–1994 to 8.99% (95% CI 8.94 – 9.04) during 2007–2010. The percentage of patients with severe AP increased from 5% (95% CI 4.95 – 5.05) during 1991–1994 to 9.78% (95% CI 9.73 – 9.83) during 2007–2010 (Figure 3a–b). Renal and respiratory failure contributed the most to the severity of AP, and their contribution remained constant during the observation period (74 and 32% in 1991–1994, and 78 and 33% in 2007–2010 respectively). Reliable estimates for organ failure and severe AP trends could not be calculated by sex, race and age groups, or for individual components of each of the criteria used to define severity due to low figures.

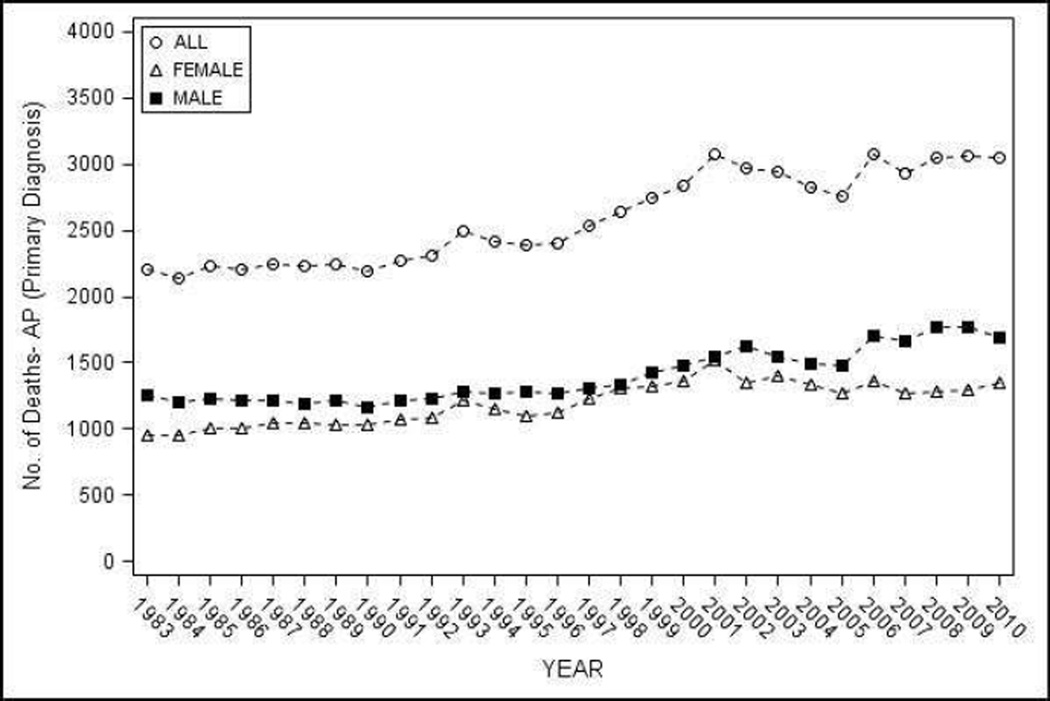

Figure 3.

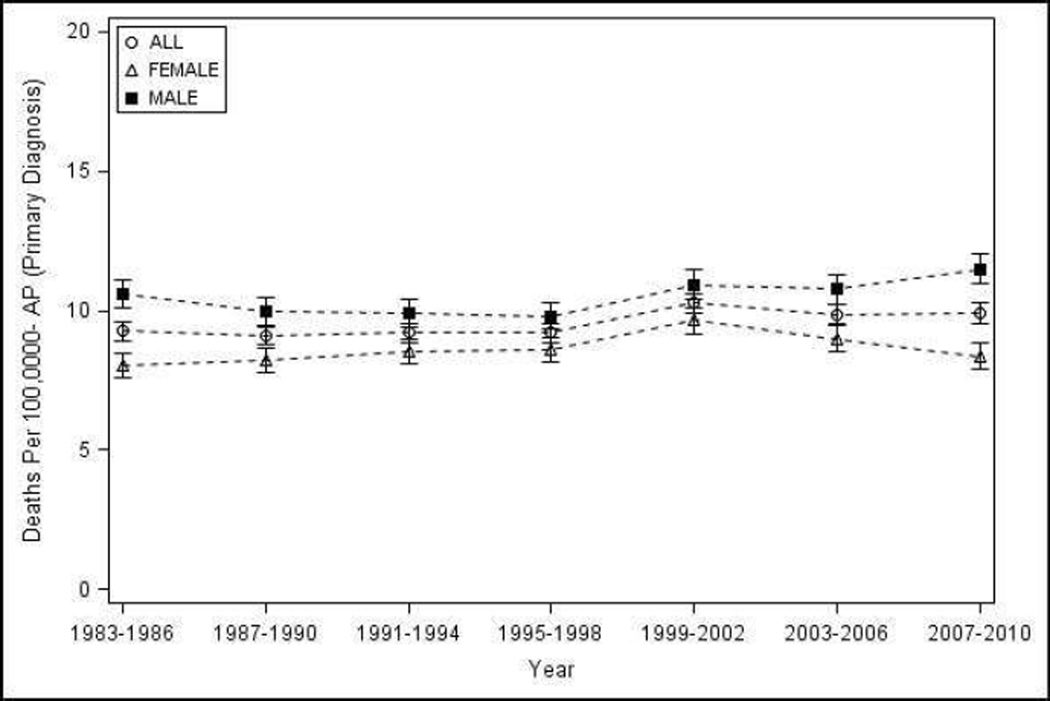

Mortality from AP as the primary cause in the United States from 1983–2010 - a) Number of deaths, overall and by sex; b) age and sex adjusted population mortality overall, and age adjusted population mortality by sex

AP-related population mortality

The total number of deaths where AP was listed in vital statistics as the primary cause was 72,521 and any cause from 1983–2010 was 158,910. The total number of deaths with AP as the primary cause increased from 2,203 in 1983 to 3,045 in 2010 (Figure 4a), and where AP was identified as any cause of death increased from 4,891 in 1983 to 5,808 in 2010.

Figure 4.

Proportion of patients with AP as the primary diagnosis with - a) organ failure; b) severe AP

Population mortality rate per one million population with AP as the primary cause showed an increase of 9% on 10-year intervals from 9.18 (95% CI 8.84–9.52) during 1983–1990 to 10.01 (95% CI 9.65–10.36) during 2001–2010 which was statistically significant, but a non-significant increase for 4-year intervals from 9.28 (95% CI 8.94–9.62) during 1983–1986 to 9.91 (95% CI 9.56–10.26) during 2007–2010 (p-trend 0.18). On subset analysis, a significant increase in the population mortality rates were noted for whites, and a significant decrease in blacks on 10-year (Table 3) and 4-year analyses (p-trend <0.05), but not for other groups.. Interestingly, population mortality was significantly higher in blacks when compared with whites during the early part of the study period, but this difference was lost around year 2000 and in the last four years of the study period, the population mortality in whites was significantly higher than blacks (data not shown) but not on 10-year analysis (Table 3). Population mortality was slightly higher in males when compared with females, and increased progressively with age with death rates in the elderly substantially higher when compared with other age groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Acute Pancreatitis related population mortality in the United States from 1983–2010

| Group |

Death rate per 100,000 persons (95% CI) with primary diagnosis of Acute Pancreatitis |

Death rate per 100,000 persons (95% CI) with any diagnosis of Acute Pancreatitis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1983–1990 | 1991–2000 | 2001–2010 | 1983–1990 | 1991–2000 | 2001–2010 | |

| All | 9.18 (8.84, 9.52) |

9.36 (9.01, 9.70) |

10.01 (9.65, 10.36) |

21.19 (20.68, 21.70) |

21.97 (21.44, 22.49) |

19.92 (19.42, 20.42) |

| Male | 10.29 (9.78, 10.80) |

10.00 (9.50, 10.50) |

11.16 (10.63, 11.69) |

24.53 (23.74, 25.32) |

24.36 (23.58, 25.15) |

22.02 (21.27, 22.77) |

| Female | 8.12 (7.68, 8.57) |

8.74 (8.28, 9.20) |

8.90 (8.43, 9.36) |

18.02 (17.36, 18.68) |

19.67 (18.98, 20.37) |

17.89 (17.23,18.55) |

| White | 8.98 (8.61, 9.36) |

9.36 (8.97, 9.74) |

10.51 (10.10, 10.91) |

20.28 (19.71, 20.84) |

21.25 (20.67, 21.82) |

20.54 (19.97, 21.11) |

| Black | 12.07 (11.02, 13.12) |

11.30 (10.28, 12.32) |

9.72 (8.77, 10.66) |

30.96 (29.28, 32.64) |

30.85 (29.17, 32.53) |

20.99 (19.61, 22.38) |

| Other | 3.62 (2.81, 4.43) |

3.96 (3.11, 4.81) |

4.14 (3.28, 5.01) |

8.84 (7.58, 10.10) |

10.37 (9.00, 11.74) |

9.54 (8.22, 10.85) |

| Age 0–24 | 0.35 (0.24, 0.47) |

0.34 (0.23, 0.46) |

0.35 (0.24, 0.47) |

0.69 (0.53, 0.85) |

0.87 (0.69, 1.05) |

0.75 (0.58, 0.92) |

| Age 25–34 | 2.57 (2.08, 3.06) |

2.40 (1.92, 2.87) |

2.48 (2.00, 2.96) |

6.02 (5.27, 6.77) |

6.57 (5.78, 7.35) |

4.62 (3.96, 5.28) |

| Age 35–44 | 6.04 (5.29, 6.79) |

5.25 (4.55, 5.96) |

5.45 (4.74, 6.17) |

14.99 (13.80, 16.17) |

14.67 (13.49, 15.84) |

10.78 (9.78, 11.79) |

| Age 45–54 | 9.28 (8.39, 10.17) |

8.80 (7.93, 9.66) |

8.98 (8.10, 9.85) |

23.63 22.21, 25.06) |

22.72 (21.33, 24.11) |

19.15 (17.87, 20.42) |

| Age 55–64 | 16.60 (15.28, 17.93) |

14.41 (13.17, 15.64) |

14.65 (13.41, 15.90) |

38.91 (36.88, 40.93) |

34.98 (33.06, 36.90) |

29.42 (27.66, 31.18) |

| Age +65 | 44.19 (42.16, 46.25) |

45.90 (43.81, 48.00) |

47.27 (45.14, 49.39) |

98.91 (95.83, 101.98) |

100.80 (97.69, 103.90) |

92.70 (89.73, 95.67) |

Population mortality per one million population where AP was listed as any cause decreased significantly by 12% when evaluated by 4-year intervals from 20.87 (95% CI 20.36–21.38) during 1983–1986 to 18.48 (95% CI 18.00–18.96) during 2007–2010 as well as 10-year intervals by 6% from 21.19 (95% CI 20.68–21.70) during 1983–1990 to 19.92 (95% CI 19.42–20.42) (Table 3). Trends for subgroup analyses were mostly similar to mortality from AP as the primary cause

Discussion

This nationwide US study of ~5 million hospital discharges spanning over a quarter century improves our understanding of the epidemiologic trends of AP. Increasing prevalence of severe disease among diagnosed cases suggests that true increase in disease may be an important contributor to the rising burden of AP in the population. Increasing rates of obesity is the most plausible and unifying explanation for both of these observations. While case-fatality progressively decreased, little change in population mortality was noted. This paradoxical observation likely reflects balancing of increased prevalence of disease severity with improvement in medical and surgical care of AP patients.

While increasing incidence of AP has been documented in numerous studies, reasons for this observation have been speculative7. Studies in individual populations have evaluated gallstones and alcohol consumption as potential reasons3. Increase in gallstone AP would be applicable to most populations due to near universal increase in the prevalence of obesity15. On the other hand, an increase in alcoholic AP will be limited only to populations where per capita alcohol consumption is increasing15. Etiology of AP comes into consideration only after a diagnosis has been established. Therefore, evaluating the distribution of etiologies in patients diagnosed with AP will not help to determine whether increase in incidence reflects true increase of disease in a population. Moreover, etiology of AP will not influence performance of serum pancreatic enzyme estimations in patients with abdominal pain symptoms which have been reported as a potential reason for increased detection of AP9.

We hypothesized that evaluating trends for disease severity will be an unbiased approach to differentiate a true increase in disease (which will be reflected as unchanged or increasing prevalence of severe disease) from detection bias (which will be reflected by decreasing prevalence of severe disease). Increasing prevalence of severe disease in AP patients noted in our study is therefore suggestive of a true increase in disease burden in the population. This, coupled with ecologic observations of increasing obesity16 and stable rates for alcohol consumption17 in US population provides indirect evidence that gallstone-related AP (obesity is a risk factor for gallstones) is likely an important contributor to the increasing incidence of AP. Obesity is also a well-accepted risk factor for AP severity18. Studies in recent years have provided mechanistic clues for this association. Specifically, unsaturated free fatty acids produced by lipolysis of intra- and peri- pancreatic fat by the action of pancreatic lipase has been demonstrated to result in local and systemic complications of AP19, 20. A direct correlation has been noted between the amount of visceral fat and truncal obesity, thereby explaining a higher risk of disease severity in obese individuals21.

We used vital statistics to determine all deaths where AP was mentioned as the primary or contributing cause, irrespective of the timing (i.e. initial hospitalization as well as delayed mortality, which can sometimes occur weeks or months later were captured) or location (hospital, non-hospital settings such as rehabilitation facilities or skilled nursing facilities, home, hospice). Determining population mortality after standardization of population distribution adjusts for changes in population characteristics over time (e.g. aging of the population, since age is an important determinant of mortality in AP). While the observation of decreasing case fatality and little change in population mortality appears paradoxical, this observation has been noted previously in European studies22–24 and can easily be explained. In the past 3 decades, many advances have occurred in the evaluation and management of AP such as better recognition of patients at risk of severe disease, importance of early and aggressive fluid resuscitation, management of organ failure (ICU care), availability of antibiotics with bioavailability in the pancreas, delaying surgical debridement for local complications and advances in the treatment of necrotizing pancreatitis25–31. An alternative explanation for these observations would be detection bias - i.e. identification of milder cases as the reason for decreasing case-fatality and no change in population mortality. However, this argument does not take into consideration the effect of increasing obesity on disease severity or the beneficial effect of advances in the management of AP. Therefore, it is likely that increasing burden of patients with severe AP due to rising incidence is balanced by better treatment of patients with a resultant decrease in mortality, thereby resulting in minimal change in the population mortality from AP. While these results are encouraging, care of AP patients is still largely supportive. Future research should therefore focus on developing targeted therapies to decrease disease severity and overall mortality.

Other findings of our analysis, such as increasing hospitalizations, racial differences in risk, decreasing case-fatality, and increasing risk of death with age replicate findings from several previous studies1, 3, 4. Strengths of our study include nationwide data set with large number of patients, broad definition of disease severity, and use of vital statistics to capture population mortality and a long study period.

Limitations of our study pertain to our use to administrative data. The validity of AP diagnosis, sensitivity of measures to assess severity and their accuracy over time in the NHDS dataset is unknown. Thus, an underestimation of severity during the initial period could explain our findings of increasing prevalence of severity. However, even if we consider the prevalence of severity during the observation period to constant, detection bias alone fails to explain the observed trends as discussed above. Our definition was broad and also included intra-abdominal infections and pancreatic surgeries for local complications. Renal failure contributed more to severity than respiratory failure (which is the most common organ failure noted clinically) - however, their proportional contribution remained constant over time, suggesting that if underestimation of respiratory failure was present, it was evenly distributed during the study period. Due to these limitations, our observations should be considered hypothesis generating, and need to be evaluated in other populations to determine the role of true increase in disease burden towards increasing incidence of AP. NHDS dataset includes individual hospitalizations in non-unique patients, meaning that some patients would be represented more than once. The rate of hospitalization in our study is therefore an overestimation due to inclusion of patients with first attack as well as recurrent attacks of AP. Recurrent AP is shown to be usually milder when compared with the first attack3. An increasing prevalence of severe disease even after inclusion of patients with recurrent AP therefore is reassuring and provides validity to our analyses. Similar overall prevalence in corresponding time periods in previous publications for severe disease using the NHDS dataset (1988–2003)14, and for organ failure in patients with first hospitalization for AP in Allegheny County, PA (1996–2005)32 is also reassuring. An increase in incidence trend was observed overall and after stratification by sex and age, but not by race. It is important to highlight that information on race is missing in about 20% cases in the NHDS dataset, which could be a potential explanation for this finding. Moreover, race specific incidence rates reported in our analyses is likely an under representation of the actual rates.

In conclusion, during a 28 year period, we confirm the trends reported in prior studies for hospitalizations and case-fatality of AP in the United States. We found an increasing trend for the number of episodes of AP and the prevalence of severe disease among AP episodes, but little change in population mortality from AP during this period. These findings suggest that true increase in the burden of episodes is an important contributing factor to the rising incidence of AP, and that the paradoxical observation of increasing severity and no change in population mortality may be related to the impact of medical advances in the management of AP. Future research should focus on designing treatments to reduce severity and mortality from AP at a population level.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: None

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflict of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Authorship criteria and contributions:

Study design: SM, DY

Data analysis: SM

Data interpretation, drafting, revisions and final approval of the manuscript: SM, DY

References

- 1.Frey CF, Zhou H, Harvey DJ, et al. The incidence and case-fatality rates of acute biliary, alcoholic, and idiopathic pancreatitis in California, 1994–2001. Pancreas. 2006;33:336–344. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000236727.16370.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spanier BW, Dijkgraaf MG, Bruno MJ. Trends and forecasts of hospital admissions for acute and chronic pancreatitis in the Netherlands. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:653–658. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f52f83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yadav D, Lowenfels AB. Trends in the epidemiology of the first attack of acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Pancreas. 2006;33:323–330. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000236733.31617.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang AL, Vadhavkar S, Singh G, et al. Epidemiology of alcohol-related liver and pancreatic disease in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:649–656. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Go Vay Liang WJE. Pancreatitis. In: Everhart JE, editor. Digestive diseases in the United States: Epidemiology and impact. USGPO, Washington DC and Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service and National Institute of Health; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of Gastrointestinal Disease in the United States: 2012 Update. Gastroenterology. 2012 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yadav D, Lowenfels AB. The epidemiology of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1252–1261. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banks PA, Freeman ML. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2006;101:2379–2400. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yadav D, Ng B, Saul M, et al. Relationship of serum pancreatic enzyme testing trends with the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2011;40:383–389. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182062970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. National Hospital Discharge Survey 2010 Public Use Data File Documentation. Accessed at ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHDS/NHDS_2010_Documentation.pdf on Jun 12, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Compressed Mortality File 1979–1998. CDC WONDER On-line Database. compiled from Compressed Mortality File CMF 1968–1988, Series 20, No. 2A, 2000 and CMF 1989–1998, Series 20, No. 2E, 2003. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd9.html on Jun 12, 2014.

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Compressed Mortality File 1999–2010 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released January 2013. Data are compiled from Compressed Mortality File 1999–2010 Series 20 No. 2P, 2013. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd10.html on Jun 18, 2014.

- 13.U.S. Census Bureau. 2010 Census Summary File 2, Table PCT3; using American FactFinder. Accessed at: http://factfinder2.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/DEC/10_SF2/QTP1//popgroup~001|002|004|006|012|050|400. December 3, 2013.

- 14.Fagenholz PJ, Castillo CF, Harris NS, et al. Increasing United States hospital admissions for acute pancreatitis, 1988–2003. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. [Accessed 4.7.15];Global Health Observatory Data. Available at: http://www.who.int/gho/countries/aus/country_profiles/en/

- 16.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed March 31, 2015];Obesity prevalence maps. http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html.

- 17.National Center for Health Statistics. Health US, 2011: With Special Feature on Socioeconomic Status and Health. Hyattsville, MD: 2012. [Accessed September 13, 2012]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong S, Qiwen B, Ying J, et al. Body mass index and the risk and prognosis of acute pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2011;23:1136–1143. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834b0e0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navina S, Acharya C, DeLany JP, et al. Lipotoxicity causes multisystem organ failure and exacerbates acute pancreatitis in obesity. Science translational medicine. 2011;3:107ra110. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noel P, Patel K, Durgampudi C, et al. Peripancreatic fat necrosis worsens acute pancreatitis independent of pancreatic necrosis via unsaturated fatty acids increased in human pancreatic necrosis collections. Gut. 2014 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Camhi SM, Bray GA, Bouchard C, et al. The relationship of waist circumference and BMI to visceral, subcutaneous, and total body fat: sex and race differences. Obesity. 2011;19:402–408. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corfield AP, Cooper MJ, Williamson RC. Acute pancreatitis: a lethal disease of increasing incidence. Gut. 1985;26:724–729. doi: 10.1136/gut.26.7.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eland IA, Sturkenboom MJ, Wilson JH, et al. Incidence and mortality of acute pancreatitis between 1985 and 1995. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:1110–1116. doi: 10.1080/003655200451261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomson HJ. Acute pancreatitis in north and north-east Scotland. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1985;30:104–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Besselink MG, Verwer TJ, Schoenmaeckers EJ, et al. Timing of surgical intervention in necrotizing pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 2007;142:1194–1201. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.12.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher JM, Gardner TB. The "golden hours" of management in acute pancreatitis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2012;107:1146–1150. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar N, Conwell DL, Thompson CC. Direct endoscopic necrosectomy versus step-up approach for walled-off pancreatic necrosis: comparison of clinical outcome and health care utilization. Pancreas. 2014;43:1334–1339. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mounzer R, Langmead CJ, Wu BU, et al. Comparison of existing clinical scoring systems to predict persistent organ failure in patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1476–1482. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.005. quiz e15-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sleeman D, Levi DM, Cheung MC, et al. Percutaneous lavage as primary treatment for infected pancreatic necrosis. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:748–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.12.019. discussion 752-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trikudanathan G, Navaneethan U, Vege SS. Current controversies in fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Pancreas. 2012;41:827–834. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31824c1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, et al. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491–1502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nawaz H, O'Connell M, Papachristou GI, et al. Severity and natural history of acute pancreatitis in diabetic patients. Pancreatology. 2015;15:247–252. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.