Abstract

Aurora kinases are eukaryotic serine/threonine protein kinases that regulate key events associated with chromatin condensation, centrosome and spindle function, and cytokinesis. Elucidating the roles of Aurora kinases in apicomplexan parasites is crucial to understand the cell cycle control during Plasmodium schizogony or Toxoplasma endodyogeny. Here, we report on the localization of two previously uncharacterized Toxoplasma Aurora-related kinases (Ark2 and Ark3) in tachyzoites and of the uncharacterized Ark3 orthologue in Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stages. In T. gondii, we show that TgArk2 and TgArk3 concentrate at specific sub-cellular structures linked to parasite division: the mitotic spindle and intranuclear mitotic structures (TgArk2), and the outer core of the centrosome and the budding daughter cells cytoskeleton (TgArk3). By tagging the endogenous PfArk3 gene with the green fluorescent protein (GFP) in live parasites, we show that PfArk3 protein expression peaks late in schizogony and localizes at the periphery of budding schizonts. Disruption of the TgArk2 gene reveals no essential function for tachyzoite propagation in vitro, which is surprising giving that the P. falciparum and P. berghei orthologues are essential for erythrocyte schizogony. In contrast, knock-down of TgArk3 protein results in pronounced defects in parasite division and a major growth deficiency. TgArk3-depleted parasites display several defects, such as reduced parasite growth rate, delayed egress and parasite duplication, defect in rosette formation, reduced parasite size and invasion efficiency and lack of virulence in mice. Our study provides new insights into cell cycle control in Toxoplasma and malaria parasites, and highlights Aurora kinase 3 as potential drug target.

Keywords: Apicomplexa, Toxoplasma gondii, Plasmodium falciparum, Tet-inducible system, Endodyogeny, Schizogony, Aurora kinases, Centrosome, spindle pole bodies, Replication

Introduction

Apicomplexan parasites are responsible for a wide array of pathologies in humans and animals. The species infecting humans include Plasmodium falciparum, the causative agent of the most virulent form of malaria, and Toxoplasma gondii, which causes toxoplasmosis, a significant health issue worldwide. The life cycle of apicomplexan parasites is characterized by several cycles of fast proliferation within a brief span, which is critical for their continued transmission and a contributing factor for their pathogenesis in the host (Francia et al., 2014). Cell division in apicomplexan parasites diverges significantly from that of higher eukaryotes. Apicomplexan parasites use closed mitosis of the nucleus, which leaves the nuclear envelope intact throughout division, and cytokinesis is achieved by internal or cortical budding (Francia et al., 2014). P. falciparum divides in its human host by schizogony, where multinucleated schizonts arise from multiple nuclear divisions (Arnot et al., 2011, Gerald et al., 2011, Francia et al., 2014). Surprisingly, although these multiple nuclei share the same cytoplasm, they divide in an asynchronous manner, which results in non-geometric expansion (Doerig et al., 2000, Read et al., 1993, Reininger et al., 2011). The last round of mitosis coincides with the simultaneous assembly of daughter cells (Francia et al., 2014). Rapidly dividing T. gondii tachyzoites use endodyogeny, a binary replication process that implicates a single round of DNA replication followed by nuclear mitosis, cytokinesis and the concomitant assembly and budding of two daughter cells within the mother cell (Anderson-White et al., 2012, Radke et al., 2001).

As in other eukaryotes, cell division in Apicomplexa appears to be controlled from the centrosome, which functions as a microtubule organizing center of the mitotic spindle (Suvorova et al., 2015). Plasmodium species lack typical centrioles/centrosomes. Instead, the mitotic spindles are emitted from a functional equivalent of the centrosome, the centriolar plaque or spindle pole body (SPBs) inserted at the inner face of the nuclear envelope (Gerald et al., 2011). The centrosome of Toxoplasma lies in the vicinity of the nuclear envelope (Suvorova et al., 2015). In T. gondii tachyzoites (the replicative form of the parasite), the centrosome plays a vital role in coordinating budding and mitotic events. Ultrastructural studies of various coccidian parasites (a subset of Apicomplexa that includes T. gondii) have demonstrated that duplication of the centrosome during endodyogeny occurs prior to budding, and that this involves an unusual parallel configuration of internal centriole structures (Dubremetz, 1973, Dubremetz, 1975, Dubremetz et al., 1979, Francia et al., 2014). This organelle controls the initiation of budding and has a master function in chromosome duplication and nuclear segregation (Francia et al., 2012, Suvorova et al., 2015). Little is known about the kinases controlling SPB or centrosome functions in apicomplexan parasites. For instance, only four kinases have been described to play a role in SPBs or centrosome biology, namely the P. falciparum Ark1 and the three T. gondii Nek1 (a Nima-related kinase, see below), CDPK7 and MAPK1-like kinases (Chen et al., 2013, Morlon-Guyot et al., 2014, Reininger et al., 2011, Suvorova et al., 2015). T. gondii Nek1 and MAPK1-like are recruited to the centrosome and are required for daughter cells budding and mitosis (Chen et al., 2013, Suvorova et al., 2015); and T. gondii CDPK7 is crucial for maintenance of centrosome integrity required for the initiation of endodyogeny (Morlon-Guyot et al., 2014).

Mitosis and cytokinesis in eukaryotic cells involve the concerted action of several conserved serine/threonine protein kinases, which include cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), Polo-like kinases (PLKs) (not expressed in Apicomplexa), Nima-related kinases (NEKs) and Aurora kinases (Nigg, 2001). The functions of Aurora kinases are closely linked to the dynamics of the centrosome and bipolar microtubule spindle, as well as to chromosome segregation and cytokinesis (Andrews et al., 2003, Carmena et al., 2003, Hochegger et al., 2013). Three Aurora-related kinases have been identified in malaria parasites. P. falciparum PfArk1 is detected as pairs of dots flanking the nascent nuclear spindle, suggesting association with recently duplicated spindle pole bodies in a subset of nuclei during schizogony (Carvalho et al., 2013, Reininger et al., 2011). Attempts to disrupt the PfArk1, PfArk2 or PfArk3 loci were unsuccessful but C-terminal tagging of the loci was readily obtained, strongly suggesting that all three Aurora-related kinases are essential for P. falciparum blood-stage development, and that each plays at least one function that is not redundant with those of the other two (Solyakov et al., 2011). In T. gondii the outer core of the centrosome associates with the orthologue of PfArk3 (to make the parallel with Plasmodium Aurora kinases, we will name it TgArk3 rather than TgArk1, as the protein has been previously named) (Suvorova et al., 2015). TgArk3 also associates with a linear structure lying along one side of the growing daughter inner membrane complex (Suvorova et al., 2015).

In the present study, we localized two Aurora-related kinases in T. gondii (TgArk2 and TgArk3) and assessed their functions. In addition, we determined the localization of TgArk3 orthologue in P. falciparum. Together our data suggests a conserved function for the Ark3 kinase in the Toxoplasma and Plasmodium budding process, and reveals unexpected variations in the specific roles for the various Aurora-related kinases in apicomplexan parasite cell division.

Results

Aurora-related kinases are conserved in Apicomplexa

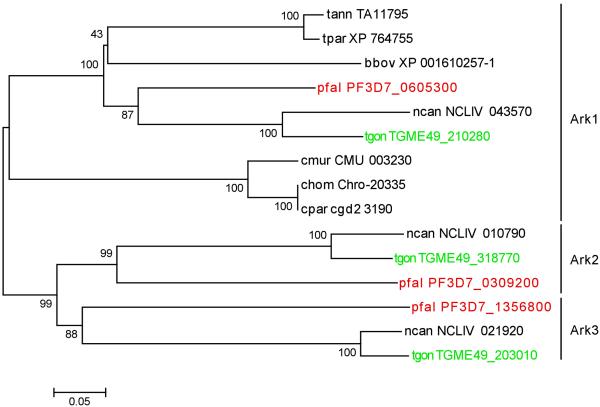

We previously identified three P. falciparum, Aurora-related kinases, PfArk1 (PF3D7_0605300), PfArk2 (PF3D7_0309200) and PfArk3 (PF3D7_1356800), and defined their phylogeny. This revealed that PfArk2 is restricted to Plasmodium species (Reininger et al., 2011). The initial analysis included two Aurora-related kinases sequences from the T. gondii ToxoDB database, TGME49_210280 (related to PfArk1 and here referred as TgArk1) and TGME49_203010 (related to PfArk3 and here referred as TgArk3), but not TGME49_318770 (here referred as TgArk2), which was not identified at the time due to long sequence insertions in its catalytic domain. For the same reason, a third Aurora-related kinase sequence in the genome of another coccidian apicomplexan, Neospora caninum, NCLIV_010790, was originally missed. A phylogenetic analysis of apicomplexan Aurora-related kinase domains, including those of the two newly identified T. gondii (TGME49_318770) and N. caninum (NCLIV_010790) sequences, indicates that both sequences cluster with PfArk2 (Fig. 1). A phylogenetic tree including Aurora-related kinases from canonical species showing that all three Plasmodium Aurora-related kinases cluster within an “Aurora clade” has been previously published (Reininger et al, 2011). The overall primary structures of TgArk2 and TgArk3 with variable N-terminal and C-terminal extensions (Supplementary Fig. 1A) are similar to those of PfArk2 and PfArk3 (Carvalho et al., 2013), respectively, further suggesting that these genes encode orthologues with conserved functions. TgArk2 (TGME49_318770) and TgArk3 (TGME49_203010) contain a putative kinase catalytic domain and represent giant 268 kDa and 298 kDa predicted proteins with long N-terminal or N- and C-terminal extensions respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1A). To avoid any inter-species confusion, the T. gondii Aurora-related kinase TGME49_203010 described by Suvorova et al (Suvorova et al., 2015), previously named TgArk1, will be here referred as TgArk3 in view of its clear orthology to PfArk3.

Fig. 1. Phylogenetic tree of Aurora-related kinases from apicomplexan parasites.

Phylogram (MEGA) with significant bootstrap values (100 iterations). The sequences are labelled with their identifier in EuPathDB database. The tree includes the previously unidentified T. gondii (TGME49_318770) and N. caninum (NCLIV_010790) orthologues of P. falciparum Ark2 (PF3D7_0309200, previously named PFC0385c) due to extensive sequence insertions in the catalytic domain and misprediction of exon-intron structure of the coding sequence, respectively (see section Results). The core kinase domains of Aurora sequences from the indicated species were extracted and subjected to optimize multiple sequence alignment using T-Coffee. Organism groups are Haemosporin: P. falciparum (Pfal); Piroplasm: T. annulata (tann), T. parvum (tpar), B. bovis (bbov); Coccidia: T. gondi (Tgon), N. caninum (ncan); and Cryptosporidium species (hominis (chom), parvum (cpar) and muris (cmur)). Note that Cryptosporidium Ark1 is distantly related to that of other Apicomplexa organisms.

The Aurora-related kinases Ark2 and Ark3 are differentially localized to distinct sub-cellular structures in T. gondii

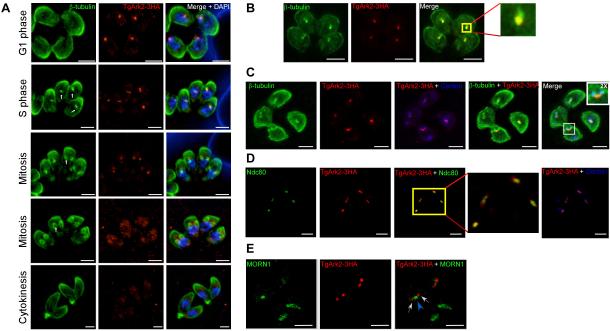

To investigate the localization of TgArk2 and TgArk3 Aurora-related kinases in T. gondii and of PfArk3 in P. falciparum, we generated transgenic parasites expressing C-terminally 3HA-tagged TgArks and GFP-tagged PfArk3, respectively using a single-cross-over homologous recombination strategy (Supplementary Figs. 1B and 2A, respectively). We showed TgArk2-3HA displays a dynamic localization pattern throughout the division cycle using anti-β-Tubulin as a cell-cycle stage specific marker (Chen et al., 2015). In G1 phase, TgArk2-3HA is recruited to the spindle pole prior to tubulin assembly and does not associate with the outer core of the centrosome (Fig. 2A, top panel and data not shown). It is found associated with the mitotic spindle throughout early mitosis (β-Tubulin, green staining) (Figs. 2A, middle panels; 2B and 2C), and disappears during bud elongation (Fig. 2A, lower panels). Co-staining of Ndc80 (a kinetochore marker) with TgArk2-3HA revealed that TgArk2-3HA localizes to the distal ends of Ndc80 staining upon spindle separation, suggesting that TgArk2-3HA splits before kinetochore duplication (Fig. 2D). No overlapping staining was observed between TgArk2-3HA and the outer core of the centrosome (Centrin, blue staining) (Figs. 2C and 2D) or with the centrocone (a sub-cellular structure found in close apposition to centrosomes) (MORN1, green staining) (Fig. 2E) (Suvorova et al., 2015). TgArk2-3HA was detected at the expected molecular mass, as assessed by Western blot (Supplementary Fig. 1C).

Fig. 2. Expression and localization of Ark2 in Toxoplasma parasites.

(A and B) IFA of intracellular TgArk2-3HA parasites showing co-localization of TgArk2 to the mitotic spindle as demonstrated by the anti-HA (red) and anti-β-Tubulin (green) co-staining. Intriguingly, TgArk2-3HA associates with mitotic spindle throughout early mitosis, and disappears during bud elongation. DAPI was used to stain DNA. The inset highlights the colocalization between TgArk2 and β-Tubulin. (C) IFA performed on intracellular TgArk2-3HA parasites using anti-HA (red staining), anti-centrin (blue staining) and anti-β-Tubulin (green staining) antibodies. Centrin is a centrosome (outer core) marker. The inset highlights the colocalization between TgArk2 and β-Tubulin but not with centrin. (D) IFA performed on intracellular TgArk2-3HA parasites using anti-HA (red staining), anti-centrin (blue staining) and anti-Ndc80 (green staining) antibodies. Ndc80 is a kinetochore marker. The inset highlights the colocalization between TgArk2 and Ndc80. (E) IFA performed on intracellular TgArk2-3HA parasites using anti-HA (red staining, white arrows) and anti-MORN1 (green staining, blue arrowhead; white arrows indicate separated TgArk2-3HA) antibodies. MORN1 is a centrocone/spindle pole marker. All scale bars represent 2 μm.

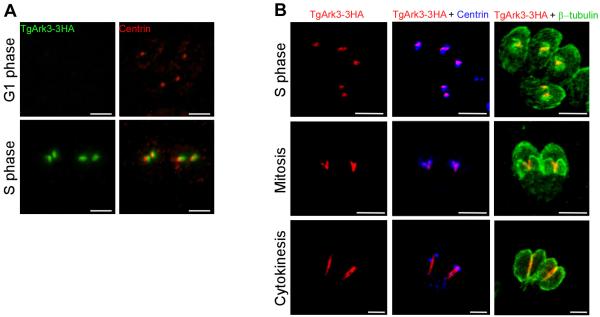

TgArk3-3HA also showed cell-cycle dependent localization. TgArk3-3HA is not expressed in G1, but in S phase, it is observed at duplicated centrosomes, partially associated with centrin (Figs. 3A and 3B), a marker commonly used to identify centrosomes in Toxoplasma parasites and recently found to be associated with the centrosome outer core (Suvorova et al., 2015). During mitosis and cytokinesis, TgArk3-3HA was found associated to a linear structure co-localizing with one side of the growing daughter cytoskeleton (Fig. 3B, lower two panels) (Suvorova et al., 2015). The TgArk3-3HA transgenic parasites expressed the 3HA-tagged Ark3 protein at the expected molecular mass, as revealed by Western blot (Supplementary Fig. 1D).

Fig. 3. Expression and localization of Ark3 in Toxoplasma parasites.

(A) TgArk3-3HA is expressed upon centrosome duplication and colocalizes partially with the outer core of the centrosome as demonstrated by the anti-HA (green) and anti-centrin (red) co-staining. Scale bars represent 2 μm. (B) IFA performed on intracellular TgArk3-3HA parasites using anti-HA (red staining), anti-centrin (blue staining) and anti-β-Tubulin (green staining) antibodies. Centrin is a centrosome (outer core) marker. Surprisingly, during mitosis and cytokinesis, TgArk3-3HA adopts a linear structure staining and co-localizes with one side of the newly formed IMCs of the daughter cells. Scale bars represent 2 μm.

In the ~48 hrs of the P. falciparum erythrocytic cycle, the formation of daughter merozoites is a rapid process that occurs within the 10 hrs following a ~18 hrs period of asynchronous nuclear replication. This latter 10 hrs phase involves a last round of mitosis that coincides with the assembly of an even number of daughter cells. To investigate a possible role for PfArk3 in merozoite ontogeny, we produced P. falciparum transgenic parasites expressing PfArk3 fused to a C-terminal GFP tag (Supplementary Fig. 2A) (Solyakov et al., 2011). Successful integration of the GFP-tag construct into the PfArk3 locus was ascertained by PCR analysis for clones #1 and #2 (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Consistent with mRNA expression profiles available on PlasmoDB, PfArk3-GFP reaches the maximum expression levels in late schizonts. No fluorescence was detected in young stages (Supplementary Fig. 2C). Instead, fluorescence was only detected in synchronized parasites corresponding to a window of ~36-48 hrs post-invasion, and first appears at the periphery of the multinucleated schizonts as discrete foci (doublets or single dots) associated with nuclei (Supplementary Fig. 2D, upper panels). The PfArk3-GFP fluorescence is then associated with more elongated cytoskeleton-like structures organized from the periphery of schizonts (Supplementary Fig. 2D, lower panels). We failed to detect full length PfArk3-GFP (~503 kDa) by western-blot, suggesting that this very large protein is expressed at low levels. The timing of the expression of PfArk3 in schizonts suggested that PfArk3 might participate to the formation of daughter merozoites at the end of the schizogonic process.

TgArk2 is dispensable for T. gondii tachyzoite survival

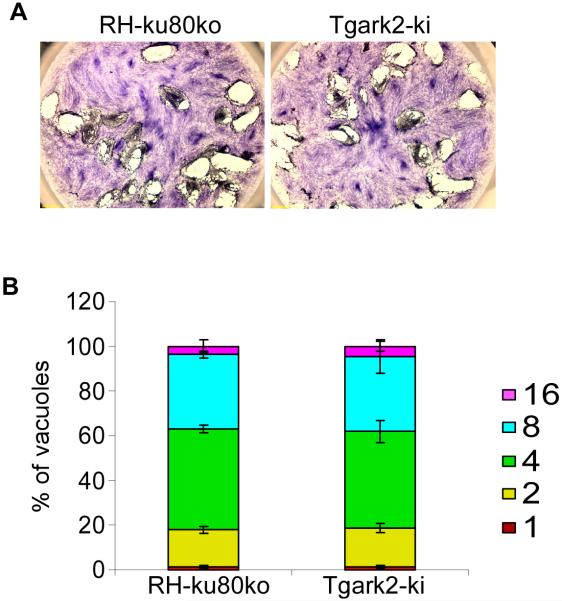

The presence of TgArk2 at the mitotic spindle and kinetochore suggests a possible role during mitosis. We used a gene disruption approach targeting the open reading frame upstream of the catalytic kinase domain (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Homologous recombination in the RH-ku80ko parental strain was achieved, as demonstrated by genomic PCR analysis of the Tgark2-ki clone (Supplementary Fig. 3B). RT-PCR confirmed that the TgArk2 catalytic kinase domain transcript (k) was absent in the Tgark2-ki strain, while the level of TgFYVE1 mRNA used as a loading control was unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 3C) (Daher et al., 2015). The phenotypic consequence of TgArk2 gene disruption was first examined by plaque assay. The Tgark2-ki parasites formed normal lysis plaques, indistinguishable from those formed by the wild-type (RH-ku80ko) parental strain (Fig. 4A). Further analysis confirmed that the absence of TgArk2 did not affect parasite growth or replication. Indeed the percentages of vacuoles containing 1, 2, 4, 8 or 16 parasites are similar in wild-type and Tgark2-ki mutant parasites (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Phenotypic analysis of TgArk2 depleted parasites.

(A) Plaque assay stained with Giemsa 7 days after invasion of the host cells with wild-type RH-ku80ko and Tgark2-ki strains. (B) Intracellular growth assay performed by counting the numbers of parasites per vacuole (x-axis) 24 h after invasion of the host cells. The percentages of vacuoles containing varying numbers of parasites are represented on the y-axis. Values are means ± S.D. for three independent experiments.

TgArk3 knock-down parasites exhibit reduced parasite growth and delayed egress

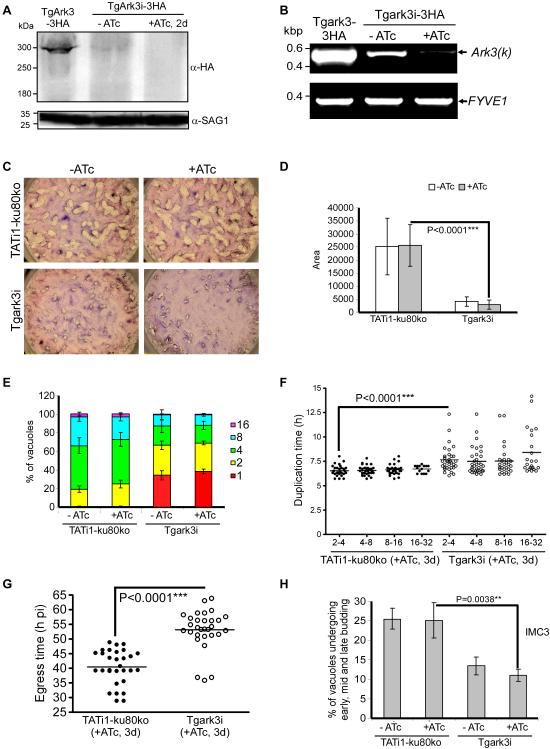

We then investigated whether TgArk3 is essential for T. gondii tachyzoite growth using the gene disruption approach targeting the open reading frame upstream of the catalytic domain by homologous recombination in the RH-ku80ko parental strain (Supplementary Fig. 4A). PCR performed on genomic DNA extracted from the uncloned population resistant to xanthine/mycophenolic acid (X/MPA) clearly shows an interruption of the TgArk3 gene (Supplementary Fig. 4B). However, despite numerous attempts, we failed to isolate a viable Tgark3-ki clone from the pool of X/MPA-resistant parasites (data not shown). The mutant Tgark3-ki parasites are lost between two and four days after the appearance of resistant parasites to X/MPA selection (Supplementary Fig. 4B), strongly suggesting that TgArk3 is crucial for Toxoplasma parasite survival. To further investigate the growth defect caused by TgArk3 gene disruption, we generated a conditional knock-down cell line for TgArk3 (Tgark3i), by replacing the endogenous promoter with an Anhydrotetracycline (ATc)-repressible promoter as described previously (Supplementary Fig. 4C) (Daher et al., 2015, Morlon-Guyot et al., 2014, Morlon-Guyot et al., 2015). Single homologous integration of the inducible cassette at the TgArk3 locus was monitored by PCR (Supplementary Fig. 4D). To study the regulation of TgArk3i protein in the presence or absence of ATc, a C-terminal triple HA epitope-tag was inserted by single homologous recombination at the inducible TgArk3 locus in the Tgark3i strain (Supplementary Fig. 4C). A chloramphenicol acetyltransferase resistance cassette was used to select transgenic parasites expressing the inducible TgArk3i-3HA protein (Supplementary Fig. 4C). Total protein extracts of the TgArk3-3HA and TgArk3i-3HA (+/− ATc) transgenic parasites were analyzed by western-blot using an anti-HA antibody; SAG1 (surface antigen 1) was used as loading control (Fig. 5A). The TgArk3-3HA or TgArk3i-3HA proteins were detected at their expected molecular masses, but placing the TgArk3 gene under the control of the minimal Sag4 promoter causes a significant down-expression of the TgArk3i-3HA protein when compared to endogenous TgArk3-3HA levels (Fig. 5A). We obtained different Tgark3i mutant clones and all of them express TgArk3 at very low levels. Further, the expression of TgArk3i-3HA is no longer detectable after 48 hrs of ATc treatment (Fig. 5A). Similarly, TgArk3 mRNA is drastically down-regulated under the control of Sag4 promoter without or after 2 days of ATc treatment (Fig. 5B), and knock-down of TgArk3 results in a dramatic effect on parasite growth observed by plaque assays with or without ATc treatment (Fig. 5C). The plaques formed were significantly reduced in size (~ 6 fold smaller), compared with the TATi1-ku80ko wild-type strain (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, TgArk3-depleted parasites showed a severe growth defect when compared to control, and did not progress through cell division as shown by the accumulation of vacuoles with only one or two parasites at day 3 (the number of parasites per vacuole were counted 24 hours after the invasion of new host cells by parasites treated for 48 hours in the presence of ATc) (38% and 31% of the vacuoles contain 1 or 2 parasite(s) respectively) or at 12 hours post-invasion ± ATc (without a pretreatment for 48 hrs in the presence of ATc) (Fig. 5E and supplementary Fig. 4E). Growth deficiency could be due to a delay in parasite duplication and/or to cell cycle blockage. To test this hypothesis, we performed time-lapse video-microscopy on the parental TATi1-ku80ko and Tgark3i strains for 72 hrs, tracking individual vacuoles. In absence of TgArk3, parasites within the same vacuole stopped to divide, showed signs of degeneration, and did not egress (compare Supplementary videos 1 and 2). The duplication time in >30 vacuoles was measured during four consecutive cycles of parasite division from 2 to 32 parasites per vacuole in Tgark3i mutant parasites and compared to the wild-type. Under our cell culture conditions, the time required for parasite duplication is typically 6.5 hrs (± 0.1) (Fig. 5F). In absence of TgArk3, we observed an increase in the average parasite duplication time to up to 7.7 hrs (± 0.2) (Fig. 5F). Moreover, we noticed a delay in the onset of the first division in Tgark3i mutant parasites compared to wild-type parasites: the average time for the first division (1 single parasite in a vacuole gives 2 parasites) was 5.5 hrs (± 2.1) in wild-type parasites, against, 8.2 hrs (± 2.8) for Tgark3i mutant parasites. In addition, the duplication time of Tgark3i mutant parasites showed a more dispersed distribution compared to that of wild type parasites (Fig. 5F). Parasite egress was also significantly delayed (by ~10 hrs), most likely as a consequence of an increase in duplication time (Fig. 5G). Further, initiation of daughter cells formation within the mother parasite was significantly impaired in TgArk3-depleted cells (Fig. 5H and supplementary Fig. 4F). The Inner Membrane Complex Protein 3 (IMC3), known to associate with the newly formed daughter parasites, and the IMC Subcompartment Protein 1 (ISP1), an exclusive marker of the apical cap of the IMC of both daughter and mother cells, were used as markers to monitor the percentage of parasites undergoing endodyogeny (Anderson-White et al., 2011, Beck et al., 2010). According to this analysis, the percentage of vacuoles containing parasites undergoing endodyogeny (showing IMC buds) is reduced 2 times in TgArk3-depleted parasites (Fig. 5H and supplementary Fig. 4F). Noteworthy, the reduced production of daughter parasites does not appear to relate to defective DNA synthesis, as 1N (G1-phase) and 1-2N (S- and M-phase) TgArk3-deficient parasite populations were found comparable to those of parental strain parasites (Supplementary Fig. 5). In T. gondii, the centrosome coordinates IMC buds, apicoplast duplication and kinetochore integrity (Chen et al., 2013, Morlon-Guyot et al., 2014, Striepen et al., 2000, Suvorova et al., 2015). Examination of subcellular structures of TgArk3-depleted parasites by IFA revealed, however, that the apicoplast, the mitochondrion, centrosome duplication and kinetochore integrity were not affected (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Fig. 5. Characterisation and phenotypic analysis of TgArk3 conditional knock-down parasites.

(A) Western blot analysis of TgArk3-3HA and TgArk3i-3HA (+/− ATc) strains. TgArk3i-3HA parasites were treated for 2 days with ATc. SAG1 was used as loading control. (B) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of TgArk3 expression in the wild-type and mutant parasites, preceded or not by 2 days of ATc treatment to regulate expression. The FYVE1 gene was used as a loading control. (C) Plaque assay performed on HFF monolayer infected with TATi1-ku80ko and Tgark3i parasites. After 7 days ± ATc, the HFF were stained with Giemsa. (D) The area of 30 plaques formed by the individual strains ± ATc was measured by using ImageJ software. Student’s t-test ***P < 0.0001; values are means ± S.D. (E) Intracellular growth of TATi1-ku80ko and Tgark3i cultivated in presence or absence of ATc for 48 hours and allowed to invade new HFF cells. Numbers of parasites per vacuole (x axis) were counted 24 hours after inoculation. The percentages of vacuoles containing varying numbers of parasites are represented on the y-axis. Values are means ± S.D. for three independent experiments. (F) Parasite duplication time was measured by time-lapse video microscopy. Dots show the time between two duplications for individual vacuole from 2 parasites per vacuole to 32 parasites per vacuole for wild-type and mutant strains treated with ATc for 3 days. A minimum of 30 vacuoles were tracked. The horizontal lines represent the means of parasites duplication time for each duplication step and parasite strain. Student’s t-test ***P < 0.0001. P: parasite. (G) The time of parasite egress was tracked by time-lapse video microscopy. Dots show the follow up of parasites egress for each strain treated with ATc for 3 days; each individual dot represents the egress time of one individual vacuole. The horizontal lines represent the means of parasites egress time for each strain from a minimum of 30 events observed per condition. Student’s t-test ***P < 0.0001. (H) Endodyogeny assay performed on TATi-ku80ko and Tgark3i strains cultivated in presence or absence of ATc for 48 hours and allowed to invade new HFF cells. Numbers of vacuoles showing the formation of newly formed buds (y axis) were counted 24 hours after inoculation using anti-IMC3 antibodies. Student’s t-test **P = 0.0038; values are means ± S.D. for three independent experiments.

These results indicated a role for TgArk3 in early steps of parasite division.

TgArk3 is required for parasite morphology and invasion efficiency

The association of TgArk3 with the cytoskeleton of daughter cells suggests a role for this kinase in maintaining the morphology of the parasites (Suvorova et al., 2015). To verify this hypothesis, we measured the length and the width of extracellular mutant parasites in the presence or absence of ATc. Our data showed that TgArk3-depleted parasites were about 9% shorter than wild-type parasites (Fig. 6A). In contrast, mutant parasites width remained unchanged (Fig. 6A). Recently, it has been reported that morphological modifications affect the ability of mutant parasites to invade host cells (Lentini et al., 2015). Interestingly, invasion assays allowed us to establish that the level of invasion by TgArk3-depleted parasites was reduced to 44% of that showed by control parasites grown in the presence of ATc (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Effect of TgArk3 depletion on parasite morphology and invasion efficiency

(A) Measurement of the length and the width of TATi1-ku80ko and Tgark3i parasites cultivated in presence or absence of ATc for 72 hours. Tgark3i parasites are statistically shorter than TATi1-ku80ko parasites, while the width is unchanged. Student’s t-test ***P < 0.0001; values are means ± S.D. for three independent experiments (n = 150). (B) Invasion assay performed on wild-type TATi1-ku80ko or Tgark3i strains ± ATc. The percentage of invaded cells is represented on the graph. Student’s t-test ***P < 0.0001; values are means ± S.D. for three independent experiments.

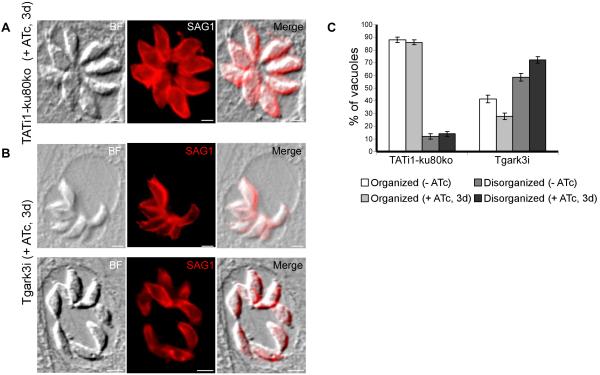

TgArk3-depleted parasites display a defect in rosette conformation

In the parasitophorous vacuole, T. gondii proliferates and organizes in rosettes around a residual body, which is surrounded by a membranous nano-tubular network (Muniz-Hernandez et al., 2011). Parental TATi1-ku80ko parasites showed a typical rosette organization within host cells, with groups of parasites clustered with their apical/anterior ends projecting outwards, while their posterior ends clustered at the center of the rosette (Figs. 7A and 7C). In contrast, a significant number of TgArk3-depleted parasites within the parasitophorous vacuole did not display the typical rosette organization within host cells (Figs. 7B and 7C). Knock-down of TgArk3 led to 60-70% of vacuoles presenting a defect in the typical rosette organization, as compared to 10% in parental TATi1-ku80ko parasites (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7. TgArk3 is involved in the rosette organisation of parasites within the parasitophorous vacuole membrane (PVM).

(A) A vacuole containing 8 parasites organized in the form of a rosette. The parasites were visualized by using anti-SAG1 antibodies (a plasma membrane marker). (B) Tgark3i mutant parasites showed either piled up parasites occupying a small space of the PVM (upper panel) or disorganized parasites distributed randomly within the PVM space (lower panel). Scale bars represent 2 μm. (C) Scoring of vacuoles showing normal or abnormal organization of parasites within the PVM by IFA using anti-SAG1 antibodies. The experiments were performed on wild-type TATi1-ku80ko and Tgark3i strains ± ATc for three days. Data are mean values ± SD for three independent experiments.

TgArk3 knock-down suppresses parasite virulence in mice

We tested the virulence of TgArk3-depleted parasites in a mouse model. The parental TATi1-ku80ko parasite and its derivative Tgark3i originate from the RH strain, a type I strain, which kills mice 8–10 days after intra-peritoneal injection of a single tachyzoite. In two independent experiments, two groups of 10 mice each were infected with 2 million TgArk3-knock-down or parental strain tachyzoites, and monitored daily over a period of two months. Mice infected with wild-type tachyzoites died within 6–8 days (Fig. 8). In contrast, none of the mice infected with Tgark3i parasites (in the absence of ATc treatment) died over the two months period of observation (Fig. 8). These data were consistently observed in two independent experiments, demonstrating that the knock-down of TgArk3 suppresses the virulence in mice.

Fig. 8. Knock-down of TgArk3 protein suppresses parasite virulence in a mouse model.

Two million tachyzoites of the indicated strains were injected into Swiss female mice (n = 20) and mouse survival was monitored daily (ATc was not added in the mice drinking water). The Tgark3i strain statistically suppresses virulence as compared to the wild-type strain (P-value < 0.001).

Discussion

This study addresses the localization of two Aurora-related kinases in T. gondii. We show that Toxoplasma TgArk2 and TgArk3 are sequentially recruited to distinct structures involved in cell cycle progression. TgArk2 localizes to structures associated with the kinetochore and the mitotic spindle and TgArk3 was found connected to the outer core of the centrosome and to the cytoskeleton on one side of budding daughter parasites. We also show that Plasmodium PfArk3 displays a dynamic pattern of expression late in schizogony and is recruited to specialized structures that might be functional homologues of Toxoplasma structures in malaria parasites. In mammalian cells, Aurora A localizes to the centrosome during metaphase and subsequently (during anaphase and telophase) associates with the mitotic spindle microtubules (Carmena et al., 2003). In contrast to Aurora A, Aurora B is a chromosomal passenger protein. Specifically, Aurora B localizes to the centromeres in prophase and metaphase, the central mitotic spindle in anaphase, the spindle midzone/cleavage furrow in telophase and the midbody during cytokinesis (Carmena et al., 2003). The partial overlapping localizations observed between human and parasite Aurora kinases make it difficult to assign cross-species functional homology to the apicomplexan Arks. Nevertheless, our functional and localization data concur with phylogenetic analyses in assigning relatedness of these putative kinases to the Aurora kinase family. Furthermore, our results indicate that apicomplexan parasites use canonical mitotic kinases to accomplish essential parasite-specific functions in the control of their unique mode of divisions and cell cycle progression.

Despite the localization of TgArk2 to essential subcellular structures (mitotic spindle and intranuclear mitotic structures), our reverse genetic experiments indicate that, in contrast to its P. falciparum orthologue, TgArk2 is not essential for mitosis and parasite development. The likely essentiality of PfArk2 could be explained by the difference related to diverse mode of divisions, schizogony vs endodyogeny. The apparent lack of involvement of TgArk2 in mitotic control is intriguing. We speculate that the function of TgArk2 during mitosis may overlap with another uncharacterized kinase; also, this putative kinase may be needed when the DNA content exceeds 2N in a single cell; for example during schizogony or endopolygeny. Schizogony is the mode of replication used by P. falciparum. This process is highlighted by multiple rounds of mitosis and nuclear division, thus producing several nuclei in a single cell (Francia et al., 2014). Endopolygeny is used by T. gondii in the cat intestine. This procedure is characterized by multiple rounds of mitosis without nuclear division, leading to a polyploid nucleus (Francia et al., 2014).

We show, that TgArk3, in contrast to TgArk2, play important roles in multiple processes such as endodyogeny, parasite duplication rate and parasite morphology. Interestingly, expression of Pfark3 mRNA and protein occurs late in the intra-erythrocytic cycle and peaks after the multiple rounds of asynchronous nuclear division. The late expression of PfArk3 and its dynamic sub-cellular localization to structures that may be similar to those of Toxoplasma where TgArk3 is recruited suggests a conserved function in the machinery that coordinate the budding of newly formed merozoites, although it may also play a role in the final wave of nuclear division.

We demonstrated a role of TgArk3 in maintaining a standard rate of daughter cells budding, which is highly likely linked to its association to the outer core of the centrosome. A recent study in T. gondii revealed a unique bipartite structure of the centrosome, which coordinates both mitosis and cytokinesis (Suvorova et al., 2015). Mutants with defects in outer core components display failure of daughter cell budding, but nuclear division is unaffected (Suvorova et al., 2015). These data illustrate that the outer core organizes daughter cell budding while the inner core coordinates mitosis, and that it is possible to uncouple budding from mitosis. TgArk3 kinase was found associated partially to the outer core of the centrosome (Fig. 3A), and consequences of its depletion provides a confirmation of the model on how the centrosome can separate the nuclear cycle from the division cycle (Suvorova et al., 2015). TgArk3-depleted parasites were able to trigger the nuclear division cycle but were impaired in daughter cell budding and cytokinesis. Therefore TgArk3 represents a potential putative kinase that might phosphorylate components of the centrosome outer core involved in a checkpoint at the end of the S phase required for the initiation of cytokinesis and IMC buds ontogeny.

The co-localization of TgArk3 with cytoskeleton of daughter cells supports a role in coordination of microtubular cytoskeleton assembly, a conclusion consistent with the formation of parasites with shorter length (which is known to affect ability to invade host cells). The future identification of TgArk3 substrates will be helpful to scrutinize mechanistically the mode of action of this atypical and crucial Aurora-related kinase.

Finally, a main result is the impact of TgArk3 deficiency on parasite virulence. We showed that a defect of division eliminates the in vivo virulence of parasites. This finding places Ark3 on the list of druggable kinases to fight against apicomplexan parasites.

Experimental Procedures

Ethics statement and in vivo experiments

All mice protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee (IACUC) of the American University of Beirut (AUB) (IACUC Permit Number #14-3-278). All animals were housed in approved pathogen-free housing. Humane endpoints were used as requested by the AUB IACUC according to AAALAC (Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International) guidelines and guide of animal care use book (Guide, NRC 2011). Mice were sacrificed for any of the following reasons: 1) impaired mobility (the inability to reach food and water); 2) inability to remain upright; 3) clinical dehydration and/or prolonged decreased food intake; 4) weight loss of 15-20%; 5) self mutilation; 6) lack of grooming behavior/rough/unkempt hair coat for more than 48 hours; 7) significant abdominal distension; 8) unconsciousness with no response to external stimuli. Mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane before cervical dislocation.

Twelve- to 16-week-old Swiss mice (Charles River, France) were infected by i.p. injection of 2 million tachyzoites freshly harvested from cell culture. Invasiveness of the parasites was evaluated by simultaneous plaque assay of a similar dose of parasites on HFFs. Mouse survival was monitored daily during three months, end-point of all experiments. Two independent experiments with 10 mice each were conducted. The immune response of surviving animals was tested following eye pricks performed on day 7 post infection. Sera were tested by western blotting against tachyzoite lysates. Data were represented as Kaplan and Meier plots using Excel.

Phylogenetic analysis

Multiple sequence alignment of protein kinase catalytic domains was performed using T-Coffee and quality of alignment assessed; sequence insertions of tgon TGME49_318770 (codons 2016-2102, 2224-2254, 2278-2307) were edited manually. The bootstrap neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was generated using MEGA version 4.1 software.

Parasite culture

T. gondii RH strains RH-ku80ko (Huynh et al., 2009) and TATi1-ku80ko (Sheiner et al., 2011) were grown in human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) (American Type Culture Collection-CRL 1634) maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; GIBCO, Invitrogen) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum and 2 mM glutamine. Selection of transgenic parasites were performed with chloramphenicol for CAT selection (Kim et al., 1993); mycophenolic acid (MPA) and xanthine for HXGPRT selection (Donald et al., 1996); pyrimethamine for DHFR-TS selection (Donald et al., 1993). Anhydrotetracycline (ATc) was used at 1.5 μg/ml for the inducible system (Meissner et al., 2001).

The 3D7 clone of P. falciparum and the 3D7 transfectants were grown in human erythrocytes as described previously, using 0.5% Albumax II (Invitrogen) (Walliker et al., 1987). Parasite cultures were synchronized twice using sorbitol according to Lambros and Vanderberg (Lambros et al., 1979). To obtain enriched preparations of schizont-stage parasites, mature trophozoites were enriched by using the VarioMACS separator and CS MACS column (Miltenyi Biotec), resuspended in complete medium and returned to culture for 1-10 hr(s) prior to harvesting. Development of schizont stages was monitored by Giemsa-stained thin blood smears.

Plasmids and transfection of T. gondii

Primers used in this study are listed in the supplementary table S1.

Plasmids LIC-CAT-Ark2Ctg-3HA and LIC-CAT-Ark3Ctg-3HA were designed to add a sequence coding for a 3HA at the endogenous locus of TGME49_318770 (TgArk2) and TGME49_203010 (TgArk3) open reading frames respectively. A 1101 bp and a 1382 bp fragment corresponding to the 3’ of TgArk2 and TgArk3 respectively were amplified from genomic DNA using primer sets 1/2 and 3/4 respectively and cloned into LIC-CAT-3HA vector (Daher et al., 2015). 40 μg of these plasmids were digested by MluI and ApaI respectively, transfected in the RH-ku80ko strain and were subjected to chloramphenicol selection.

Plasmid DHFR-tetO7Sag4-NtArk3 was designed to knock-down the level of expression of Ark3 protein using the tet-off system. A 1498 bp fragment corresponding to the 5’ of the coding region of Ark3 was amplified by PCR from T. gondii genomic DNA using primers 24/25 and cloned BamHI/NotI in the DHFR-TetO7SAG4 plasmid (Daher et al., 2015, Morlon-Guyot et al., 2014, Morlon-Guyot et al., 2015, Sheiner et al., 2011) downstream of the DHFR selection marker, tetO7 operator and pSag4 promoter. The construct was linearised by EcoRV and transfected TATi1-ku80ko parasites with 40 μg of this vector were selected with pyrimethamine and cloned by limiting dilution. Positive clones were verified by PCR to detect the native locus or the single homologous recombination of the inducible vectors in the Ark3 locus.

Disruption of the TgArk2 and TgArk3 genes was performed using the plasmids TgArk2-ki and TgArk3-ki respectively. 1360 bp and 1365 bp respectively upstream of the kinase domains that contains a unique SphI or MfeI site were PCR amplified using primers 9/10 and 14/15. The PCR products were cloned into pTUB8MycGFPPfMyoAtailTy.HX vector between KpnI and NsiI sites (Daher et al., 2012). The transfections were performed in the RH-ku80ko strain using 40 μg of the linearized vector, and the transfected parasites were subjected to MPA-xanthine selection.

Plasmid and transfection of P. falciparum

The PfArk3 (PF3D7_1356800) gene fragment of the GFP construct was amplified from P. falciparum (3D7) genomic DNA using primers pair 5/6 designed to contain PstI and BamHI restriction sites, respectively. The 967 bp PfArk3-GFP-tag fragment was cloned into a modified pCam-BSD plasmid containing the open reading frame of the GFP version II subcloned from pHH2, followed by the 3’ UTR of the P. berghei dihydrofolate reductase gene downstream of the multi-cloning site. The construct was sent to Dundee Sequencing Service, University of Dundee, UK, for sequence verification before being used.

Primers pair OL799/OL806 (7/8) was used to amplify across the integration site of PfArk3 gene giving rise to the expected 1.11 kb product.

The P. falciparum parasites described in this paper were grown in human erythrocytes as described previously, using 0.5% Albumax II (Invitrogen) instead of human serum (Walliker et al., 1987). Parasites were synchronized twice using sorbitol according to Lambros and Vanderberg (Lambros et al., 1979). To obtain enriched preparations of schizont-stage parasites, mature trophozoites were enriched by using the VarioMACS separator and CS MACS columns (Miltenyi Biotec). Development of schizont stages was monitored by Giemsa-stained thin blood smears. For transfections, synchronized ring-stage parasites (3D7 clone) were electroporated with 50-100 μg plasmid DNA using standard procedures. Transformed parasites were selected in presence of 2.5 μg/ml blasticidin (ENZO Life Sciences) and then cloned by limiting dilution.

T. gondii protein detection by western-blot

To detect TgArk2-3HA, TgArk3-3HA and TgArk3i-3HA proteins, parasite lysates were separated on 6% acrylamide gels. Upon transfer to nitrocellulose membranes, the blots were probed with anti-HA antibodies in 5% non-fat milk powder in TNT buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0; 150 mM NaCl; 0.05% Tween20). The rat anti-HA (Roche) antibody was used at the dilution of 1/300 (Morlon-Guyot et al., 2014). Bound secondary conjugated antibodies were visualized using the alkaline phosphatase kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (Promega).

T. gondii fluorescence microscopy

Briefly, for IFAs of intracellular parasites, infected confluent HFF monolayers were alternatively fixed by 100% methanol for 10 minutes followed by 30 minutes blocking with 1% BSA in PBS or 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized with 0.2% triton X-100, blocked with 10% FCS in PBS, and then incubated with primary antibodies (anti-HA (Roche) 1:100, anti-IMC3 1:2000 (Anderson-White et al., 2011), anti-SAG1 1:1000 (Couvreur et al., 1988), anti-ATRX1 1:1000 (kindly provided by Dr Peter Bradley), anti-mitochondrial F1 beta ATPase (P. Bradley, unpublished), anti-ROP1 1: 1000 (Leriche et al., 1991), anti-centrin 1:1000 (kindly provided by Dr. Iain Cheeseman), anti-Nuf2 1:2000 (Farrell et al., 2014), anti-Ndc80 1:2000 (Farrell et al., 2014), anti-MORN1 1:1000 (Gubbels et al., 2006), anti-ISP1 1:1000 (Beck et al., 2010), anti-Chlamydomonas centrin 1:1000 (clone 20H5, mouse, Millipore), anti-β-Tubulin 1:500 (Morrissette et al., 2002) followed by goat-anti-rabbit or goat-anti-mouse or goat-anti-rat or goat-anti-Guinea pig immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 594 (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen). Coverslips were mounted onto microscope slides using Immu-mount (Calbiochem). Samples were observed with a Zeiss Axioimager epifluorescence microscope equipped with an apotome and a Zeiss Axiocam MRmCCD camera driven by the Axiovision software (Zeiss), at the Montpellier RIO imaging facility.

P. falciparum fluorescence microscopy

Expression of the PfArk3-GFP fusion protein was analyzed through direct detection of the green fluorescence in live parasites. Parasite nuclei were stained by incubation 10 min at 37ºC in complete medium containing 1 μg/ml Hoechst 3342 (Invitrogen). Stained parasites were diluted and placed on a slide and coverslip prior to fluorescence microscopy examination performed on a Delta vision deconvolution fluorescence microscope (100X/1.4 oil immersion objective Olympus IX-70). Images were processed using IMARIS version 7.0.

Time-lapse Video Microscopy to monitor T. gondii duplication and egress

Human Foreskin Fibroblasts (HFFs) were seeded in 8 wells glass bottom μplates (Ibidi). Host cells were then infected with 10 μl of each parasitic strain (TATi1-ku80ko or Tgark3i) harvested from a 25 cm2 flask containing freshly lysed parasites cultivated during 72 hours in presence of ATc. Two hours after invasion, the wells were washed with medium to remove remaining extracellular parasites. Samples were then placed on an inverted microscope (Axio-observer, Zeiss) equipped with an incubation chamber set up at 37°C, connected to 5% CO2 and equipped with a 100X Plan apochromat NA 1.4 objective and phase contrast. Image acquisition was performed using Zen blue Software (Zeiss). A combination of definite focus and autofocus set-up in the contrast mode was used to allow the acquisition of panorama images on a single plane, alternating wild type and mutant strain, every 10 min during 72 hours. The resulting panoramas were then stitched and fused, and vacuoles were tracked manually throughout the time series. To determine interdivision times, tn was defined as the time point in which 2 newly formed daughter cells could be clearly distinguished, tn+1 was defined as the time point were at least one of the Toxoplasma from the same vacuole has divided again. To determine egress times, tn was defined as the time point in which the parasites from the same vacuole have egressed. Only vacuoles that could be tracked throughout the acquisition period were taken into account.

T. gondii plaque assay

Fresh monolayers of HFF on circular coverslips were infected with parasites in the presence or absence of 1.5 μg/ml ATc for 7 days. Fixation, staining and visualization were performed as previously described (Daher et al., 2010).

Intracellular growth of T. gondii and endodyogeny assays

Parasites were pretreated for 48 hours with or without 1.5 μg/ml ATc, collected promptly after egress and inoculated onto new HFF monolayers in presence or absence of ATc during 24 hours. 24 hours later, cultures were fixed with PFA and stained with anti-TgSAG1. The numbers of parasites per vacuole were counted for more than 300 vacuoles for each condition. Replication defect was determined by staining of the inner membrane complex of the mother and daughter parasites (anti-IMC3 antibodies) and by labeling of the nascent apical cones of the mother and daughter parasites (anti-ISP1 antibodies). Formation of rosette structures was assessed using anti-SAG1 antibodies. Data are mean values ± S.D. from three independent biological experiments. For each condition, 300 vacuoles were observed.

T. gondii invasion assay

Parasites were treated for 48 hours with or without 1.5 μg/ml ATc and collected promptly after egress. For invasion assays, 5.106 freshly released tachyzoites were sedimented on confluent cells at 4°C for 30 minutes on ice and warmed up for invasion during 5 minutes at 38.5°C. Invasion was stopped by fixation in 4% PFA and parasites were further processed for IFA. Prior to triton permeabilization, extracellular parasites were labelled with anti-SAG1 antibodies, while following permeabilization, intracellular parasites were stained with anti-ROP1 antibodies that labelled the nascent PV (Lebrun et al., 2005). Data are mean values ± S.D. from three independent biological experiments. For each condition, 300 parasites were observed.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from T. gondii tachyzoites using the Nucleospin RNA II kit (Macherey-Nagel, 740955.10). RT-PCR was performed with the Superscript III first-strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen, 18080-051). 3000 ng of total RNA as a template were used per RT-PCR reaction and specific primers of TgFYVE1 (20/21) or TgArk2 (18/19) or TgArk3 (29/30) were used. Thirty cycles of PCR were performed.

T. gondii DNA content analysis

Low numbers of TATi1-ku80ko and Tgark3i tachyzoites were seeded and grown in the presence and absence of ATc for three days. The extracellular parasites were removed by 1X PBS wash, and only the intracellular parasites were released from HFFs after scrapping of the monolayer and passage through a 22G needle. Parasites were filtered through glass wool to eliminate cell debris. After 24 hours fixation in 70% (v/v) ethanol/30% 1XPBS at 4°C, DNA was stained with propidium iodide and RNA removed by RNase treatment followed by analysis on a FACS Canto flow cytometer. Data were analysed using FloJo software.

Analysis of T. gondii morphology

Parasites were treated for 72 hours with or without 1.5 μg/ml ATc and collected promptly after egress. Freshly egressed parasites from control (TATi1-ku80ko) and Tgark3i parasites were resuspended in HBSS and allowed to settle on coverslips previously coated with poly-L-lysine. After fixation with 4% PAF in HBSS containing 10 mM Hepes pH 7.2, the parasites were visualized by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy and images were collected. The length and the width of 150 parasites were determined for each strain using Zeiss Zen software.

Statistics

P values were calculated in Excel using the Student’s t-test assuming equal variance, unpaired samples, and using 2-tailed distribution. Means and standard deviations (SD) were also calculated in Excel.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Peter Bradley for providing the anti-ATRX1 and anti-α-F1-ATPase β-subunit antibodies, Dr Iain Cheeseman for providing anti-centrin antibodies, Pr Dominique Soldati-Favre for plasmid pTgCtermMLC2g-3Ty.HX, Dr Vern Carruthers for providing the RH-ku80ko strain, Dr Boris Striepen and Dr Lilach Sheiner for the DHFR-tetO7-SAG4 and LIC-CAT-3HA vectors. We thank Dr Paul McMillan from the University of Melbourne for microscopy support, as well as the Monash Micro Imaging Facility. We are grateful to the Montpellier RIO imaging facility at the University of Montpellier 2. Dr Wassim DAHER, Dr Juliette Morlon-GUYOT, and Dr Maryse LEBRUN are INSERM researchers. This work was supported by the Laboratoire d'Excellence (LabEx) (ParaFrapANR-11-LABX-0024) and by the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (Equipe FRM DEQ20130326508) to Dr Maryse Lebrun, by the National Institutes of Health grants AI107475 and AI081924 and AI110690 to Dr Marc-Jan Gubbels, and by the American University of Beirut Medical Practice Plan, Cèdre and CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique), L’Oréal-UNESCO for women in science levant and Egypt Regional Fellowships Program to Dr Hiba El Hajj. The P. falciparum work received intial support from the European Commission FP7 SIGMAL and ANTIMAL projects, and from the Australian National Health & Medical Research Council (Grant APP1061351) award to Dr Teresa Carvalho and Pr Christian Doerig. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Abbreviations

- Ark

Aurora-related kinase

- TATi-1

Trans-activator Trap identified-1

- IMC

Inner Membrane Complex

- Nuf2

Nuclear Filamentous 2

- ISP1

IMC Subcompartment Protein 1

- Ndc80

Nuclear Division Cycle 80

- MORN1

multiple membrane occupation and recognition nexus 1

Footnotes

No conflict of interest exists.

References

- Anderson-White B, Beck JR, Chen CT, Meissner M, Bradley PJ, Gubbels MJ. Cytoskeleton assembly in Toxoplasma gondii cell division. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2012;298:1–31. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394309-5.00001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson-White BR, Ivey FD, Cheng K, Szatanek T, Lorestani A, Beckers CJ. A family of intermediate filament-like proteins is sequentially assembled into the cytoskeleton of Toxoplasma gondii. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13:18–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01514.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews PD, Knatko E, Moore WJ, Swedlow JR. Mitotic mechanics: the auroras come into view. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:672–683. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnot DE, Ronander E, Bengtsson DC. The progression of the intra-erythrocytic cell cycle of Plasmodium falciparum and the role of the centriolar plaques in asynchronous mitotic division during schizogony. Int J Parasitol. 2011;41:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JR, Rodriguez-Fernandez IA, de Leon JC, Huynh MH, Carruthers VB, Morrissette NS, Bradley PJ. A novel family of Toxoplasma IMC proteins displays a hierarchical organization and functions in coordinating parasite division. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001094. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmena M, Earnshaw WC. The cellular geography of aurora kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:842–854. doi: 10.1038/nrm1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho TG, Doerig C, Reininger L. Nima- and Aurora-related kinases of malaria parasites. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1834:1336–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CT, Gubbels MJ. The Toxoplasma gondii centrosome is the platform for internal daughter budding as revealed by a Nek1 kinase mutant. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:3344–3355. doi: 10.1242/jcs.123364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CT, Kelly M, Leon J, Nwagbara B, Ebbert P, Ferguson DJ. Compartmentalized Toxoplasma EB1 bundles spindle microtubules to secure accurate chromosome segregation. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:4562–4576. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-06-0437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couvreur G, Sadak A, Fortier B, Dubremetz JF. Surface antigens of Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitology. 1988;97:1–10. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000066695. Pt 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daher W, Klages N, Carlier MF, Soldati-Favre D. Molecular characterization of Toxoplasma gondii formin 3, an actin nucleator dispensable for tachyzoite growth and motility. Eukaryot Cell. 2012;11:343–352. doi: 10.1128/EC.05192-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daher W, Morlon-Guyot J, Sheiner L, Lentini G, Berry L, Tawk L. Lipid kinases are essential for apicoplast homeostasis in Toxoplasma gondii. Cell Microbiol. 2015;17:559–578. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daher W, Plattner F, Carlier MF, Soldati-Favre D. Concerted action of two formins in gliding motility and host cell invasion by Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001132. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerig C, Chakrabarti D, Kappes B, Matthews K. The cell cycle in protozoan parasites. Prog Cell Cycle Res. 2000;4:163–183. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4253-7_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald RG, Carter D, Ullman B, Roos DS. Insertional tagging, cloning, and expression of the Toxoplasma gondii hypoxanthine-xanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase gene. Use as a selectable marker for stable transformation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14010–14019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald RG, Roos DS. Stable molecular transformation of Toxoplasma gondii: a selectable dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase marker based on drug-resistance mutations in malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:11703–11707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubremetz JF. [Ultrastructural study of schizogonic mitosis in the coccidian, Eimeria necatrix (Johnson 1930)] J Ultrastruct Res. 1973;42:354–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubremetz JF. [Genesis of merozoites in the coccidia, Eimeria necatrix. Ultrastructural study] J Protozool. 1975;22:71–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1975.tb00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubremetz JF, Elsner YY. Ultrastructural study of schizogony of Eimeria bovis in cell cultures. J Protozool. 1979;26:367–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1979.tb04639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell M, Gubbels MJ. The Toxoplasma gondii kinetochore is required for centrosome association with the centrocone (spindle pole) Cell Microbiol. 2014;16:78–94. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francia ME, Jordan CN, Patel JD, Sheiner L, Demerly JL, Fellows JD. Cell division in Apicomplexan parasites is organized by a homolog of the striated rootlet fiber of algal flagella. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francia ME, Striepen B. Cell division in apicomplexan parasites. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:125–136. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerald N, Mahajan B, Kumar S. Mitosis in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Eukaryot Cell. 2011;10:474–482. doi: 10.1128/EC.00314-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubbels MJ, Vaishnava S, Boot N, Dubremetz JF, Striepen B. A MORN-repeat protein is a dynamic component of the Toxoplasma gondii cell division apparatus. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2236–2245. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochegger H, Hegarat N, Pereira-Leal JB. Aurora at the pole and equator: overlapping functions of Aurora kinases in the mitotic spindle. Open Biol. 2013;3:120185. doi: 10.1098/rsob.120185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh MH, Carruthers VB. Tagging of endogenous genes in a Toxoplasma gondii strain lacking Ku80. Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8:530–539. doi: 10.1128/EC.00358-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Soldati D, Boothroyd JC. Gene replacement in Toxoplasma gondii with chloramphenicol acetyltransferase as selectable marker. Science. 1993;262:911–914. doi: 10.1126/science.8235614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambros C, Vanderberg JP. Synchronization of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stages in culture. J Parasitol. 1979;65:418–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrun M, Michelin A, El Hajj H, Poncet J, Bradley PJ, Vial H, Dubremetz JF. The rhoptry neck protein RON4 re-localizes at the moving junction during Toxoplasma gondii invasion. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1823–1833. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentini G, Kong-Hap M, El Hajj H, Francia M, Claudet C, Striepen B. Identification and characterization of Toxoplasma SIP, a conserved apicomplexan cytoskeleton protein involved in maintaining the shape, motility and virulence of the parasite. Cell Microbiol. 2015;17:62–78. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leriche MA, Dubremetz JF. Characterization of the protein contents of rhoptries and dense granules of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites by subcellular fractionation and monoclonal antibodies. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1991;45:249–259. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90092-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner M, Brecht S, Bujard H, Soldati D. Modulation of myosin A expression by a newly established tetracycline repressor-based inducible system in Toxoplasma gondii. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:E115. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morlon-Guyot J, Berry L, Chen CT, Gubbels MJ, Lebrun M, Daher W. The Toxoplasma gondii calcium-dependent protein kinase 7 is involved in early steps of parasite division and is crucial for parasite survival. Cell Microbiol. 2014;16:95–114. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morlon-Guyot J, Pastore S, Berry L, Lebrun M, Daher W. Toxoplasma gondii Vps11, a subunit of HOPS and CORVET tethering complexes, is essential for the biogenesis of secretory organelles. Cell Microbiol. 2015;17:1157–1178. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissette NS, Sibley LD. Disruption of microtubules uncouples budding and nuclear division in Toxoplasma gondii. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:1017–1025. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.5.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muniz-Hernandez S, Carmen MG, Mondragon M, Mercier C, Cesbron MF, Mondragon-Gonzalez SL. Contribution of the residual body in the spatial organization of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites within the parasitophorous vacuole. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:473983. doi: 10.1155/2011/473983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg EA. Mitotic kinases as regulators of cell division and its checkpoints. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:21–32. doi: 10.1038/35048096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke JR, Striepen B, Guerini MN, Jerome ME, Roos DS, White MW. Defining the cell cycle for the tachyzoite stage of Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;115:165–175. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read M, Sherwin T, Holloway SP, Gull K, Hyde JE. Microtubular organization visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy during erythrocytic schizogony in Plasmodium falciparum and investigation of post-translational modifications of parasite tubulin. Parasitology. 1993;106:223–232. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000075041. Pt 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reininger L, Wilkes JM, Bourgade H, Miranda-Saavedra D, Doerig C. An essential Aurora-related kinase transiently associates with spindle pole bodies during Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic schizogony. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:205–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07442.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheiner L, Demerly JL, Poulsen N, Beatty WL, Lucas O, Behnke MS. A systematic screen to discover and analyze apicoplast proteins identifies a conserved and essential protein import factor. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002392. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solyakov L, Halbert J, Alam MM, Semblat JP, Dorin-Semblat D, Reininger L. Global kinomic and phospho-proteomic analyses of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Commun. 2011;2:565. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striepen B, Crawford MJ, Shaw MK, Tilney LG, Seeber F, Roos DS. The plastid of Toxoplasma gondii is divided by association with the centrosomes. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1423–1434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvorova ES, Francia M, Striepen B, White MW. A novel bipartite centrosome coordinates the apicomplexan cell cycle. PLoS Biol. 2015;13:e1002093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walliker D, Quakyi IA, Wellems TE, McCutchan TF, Szarfman A, London WT. Genetic analysis of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Science. 1987;236:1661–1666. doi: 10.1126/science.3299700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.