Abstract

Despite efforts to use culturally appropriate, understandable terms for sexual behavior in HIV prevention trials, the way in which participants interpret questions is underinvestigated and not well understood. We present findings from qualitative interviews with 88 women in South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe who had previously participated in an HIV prevention trial. Findings suggested that participants may have misinterpreted questions pertaining to penile–anal intercourse (PAI) to refer to vaginal sex from behind and subsequently misreported the behavior. Three key issues emerge from these findings: first, the underreporting of socially stigmatized sexual behaviors due to social desirability bias; second, the inaccurate reporting of sexual behaviors due to miscomprehension of research terms; and third, the ambiguity in vernacular terms for sexual behavior and lack of acceptable terms for PAI in some languages. These findings highlight methodological challenges around developing clear and unambiguous definitions for sexual behaviors, with implications not only for clinical trials but also for clinical practice and sexual risk assessment. We discuss the challenges in collecting accurate and reliable data on heterosexual PAI in Africa and make recommendations for improved data collection on sensitive behaviors.

Each social and cultural context has behavioral norms and linguistic guidelines around sex and sexual communication (Cain, Schensul, & Mlobeli, 2011). Sexual behavior is considered an intimate and private aspect of people's lives, and communicating about sex is often complex, uncomfortable, and embarrassing. Language referring to sex, either in colloquial or more formal wording, tends to be indirect, ambiguous, and euphemistic. Even clinical terminology can be misinterpreted or misunderstood and lack precision (Duby & Colvin, in press). In much of sub-Saharan Africa, sex is considered a taboo topic, to be discussed openly only in socially sanctioned situations, such as during initiation rites (Kawai et al., 2008; Wight et al., 2006). Researchers studying sexual behavior face a number of challenges, amplified in cross-cultural research: first, in creating an enabling environment in which participants feel comfortable enough to openly and honestly report their sexual behavior; second, in using methods that encourage the participant to report accurately and truthfully; and third, in using terms that are precise, unambiguous, easy to understand, and are likely to be interpreted as researchers intend (Frith, 2000).

The phrasing of research questions and the manner in which research participants understand and interpret terms are critical for the collection of valid and reliable data on sexual behavior. Moreover, precise assessment of risk informs the design of effective and relevant HIV interventions (Schroder, Carey, & Vanable, 2003). Accurate translation is particularly important, and difficult, in multisite studies, exacerbated by the lack of a standardized process requiring researchers to retranslate terms for each study (Cleland, Boerma, Carael, & Weir, 2004; Ramirez, Mack, & Friedland, 2013). Decades of cross-cultural research have used the widely accepted Brislin (1970) model of forward and back translation. However, even when such well-established methods are used to translate study tools and resolve “semantic incongruences” the possibility remains of selecting terms that may be unfamiliar to the study population, ambiguous, and open to misinterpretation, leading to invalid results and misplaced interventions (Baker et al., 2010). During cross-cultural research, it is essential to establish participants' comprehension and familiarity with research terms, to ensure that translated terms are accurate and not lost in translation.

Achieving participant comprehension has proven to be a major challenge in HIV prevention clinical trials (Mack, Ramirez, Friedland, & Nnko, 2013). Given that terminology for sexual behaviors is infinitely varied and fluid, even with carefully translated and piloted study tools, one cannot assume that all study participants will interpret terms for sex acts similarly. This can be particularly problematic in contexts that are “linguistically heterogeneous,” such as many parts of Africa (Cleland et al., 2004). An additional challenge in HIV prevention trials is the identification of sexual behavior terms in local languages that are unambiguous and clearly understandable without being offensive or insulting (Ndlovu, 2009; Ramirez et al., 2013).

The accuracy of sexual behavior self-reporting is influenced by the degree to which the behavior is culturally sensitive or socially undesirable, as well as concerns over loss of privacy and lack of confidentiality, and characteristics of the interviewer or interview environment (Hewett et al., 2008; Mitchell et al., 2007; Plummer et al., 2004; Rasinski, Willis, Baldwin, Yeh, & Lee, 1999). “Socially desirable and norm-driven responding” (Hewett et al., 2008) refers to the overreporting of behaviors that are perceived to be acceptable and desirable (e.g., condom use or adherence to a study product) or the underreporting of socially stigmatized, undesirable behaviors, such as selling sex, using substances, or having anal intercourse (Catania, 1999; Gorbach et al., 2013; Minnis et al., 2009).

The mode of data collection also affects the accuracy of reporting. Because ACASI (audio computer-assisted self-interviewing) is standardized, affording participants privacy and thus reducing social desirability bias, it was thought to yield more accurate data on sensitive behaviors, with the inferral that higher reporting of sensitive behaviors is necessarily more accurate (Gorbach et al., 2013; Langhaug, Sherr, & Cowan, 2010; Mensch et al., 2011; Minnis et al., 2009; Rasinski et al., 1999; Schroder et al., 2003). However, drawbacks of ACASI include the lack of opportunity to detect participant confusion, clarify terms, or probe to verify participant comprehension (Jaya, Hindin, & Ahmed, 2008; Turner et al., 2009). Where no internal consistency checks are built into the software, ACASI is likely to produce more internally discrepant data than is face-to-face interviewing (FTFI) because interviewers can, and do, reconcile inconsistencies (Hewett et al., 2008; Mensch et al., 2011). In the absence of biomarkers to validate self-reports, it is not possible to ascertain whether participants are over- or underreporting in either ACASI or FTFI.

In 1998 Karim and Ramjee warned that HIV prevention studies should consider the effect that penile–anal intercourse (PAI) may have in microbicide trials. PAI has the potential to “dilute efficacy” for three reasons: first, if participants apply a vaginal microbicide gel rectally yet the gel is not protective for PAI; second, if participants apply the gel vaginally with the perception that it will offer protection for PAI; and third, the belief that PAI is “safe sex” for which protective gel is unnecessary (Mâsse, Boily, Dimitrov, & Desai, 2009). Gorbach et al. (2013) recommended the use of ACASI in vaginal microbicide trials to ensure more accurate reporting of PAI. This article presents findings on language and terminology for PAI, and participants' understanding and interpretation of a question relating to PAI asked using ACASI in a recent HIV prevention trial (VOICE) (Marrazzo et al., 2015). Findings highlight challenges that cross-cultural and multilingual studies face with translation, as well as shed light on issues pertaining to sexual behavior reporting, specifically for socially stigmatized behaviors such as PAI.

Method

Background to the VOICE Trial

VOICE-D was a qualitative follow-up to its parent study, VOICE (MTN-003), a multisite Phase IIB HIV prevention trial testing tenofovir-based biomedical HIV prevention products, a daily tenofovir 1% vaginal gel and two daily oral tablets (Viread and Truvada). VOICE was conducted from 2009 to 2012 and enrolled 5,029 female participants from South Africa (N = 4,077), Uganda (N = 322), and Zimbabwe (N = 630) (Marrazzo et al., 2015). During VOICE, participants self-reported their adherence to study products, as well as their sexual behavior, using pictorial ACASI. The ACASI questions in VOICE were translated and back-translated using the Brislin method. Prior to the start of VOICE, ACASI instruments, including the anal sex question, were pretested in all site languages, among volunteers similar to the target population and/or local staff not directly involved with the trial. However, neither cognitive interviewing with participants nor discussions with site staff fully revealed the ambiguity of the terms during this pretesting stage.

One ACASI question, asked quarterly throughout the duration of VOICE, assessed engagement in PAI in the past three months, as follows: “In the past three months how many times have you had anal sex? By anal sex we mean when a man puts his penis inside your anus.” Due to unexpectedly high reporting of PAI, concerns were raised, approximately a year into VOICE, regarding participants' comprehension of the ACASI question. It became apparent that in the process of back-translating the terms, translators had not highlighted the ambiguity and scope for varying interpretation in translated terms for PAI (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Translations of ACASI PAI Question

| Zulu | Shona | Luganda | |

|---|---|---|---|

| English ACASI question | In the past three months, how many times have you had anal sex? By anal sex we mean when a man puts his penis inside your anus. | ||

| Translated question | Ezinyangeni ezintathu ezidlule, ngabe uye kangaki ocansini lwesitho sangasese sangemuva? Ngocansi lwesitho sangasese sangemuva sisho uma indoda ifaka isitho sayo sangasese sangaphambili phakathi esithweni sakho sangasese sangemuva. | Mumwedzi mitatu yapfuura, makambosangana pabonde nekumashure here? Kana tichiti makambosangana pabonde nekumashure, tinoreva kana murume achiisa nhengo yake nekumashure kwenyu kwamunoita nako tsvina. | Mu myezi esaatu (3) egiyise, emirundi emeeka gy'ofunye okwegata kwemabega gyofulumira? Okwegata kwemabega gy'ofulumira tutegeeza ng'omusajja atadde obusajja bwe munda gyofulumira. |

| Literal English back-translation | In the past three months, how many times did you have sex in your back private part? By sex in your back private part, we mean when a man puts his front private part in your back private part. | In the past three months, how many times did you have sex at the back? By sex at the back we mean when a man puts his penis in your stool passage. | In the past three months how many times did you engage in sex with the back part where you pass feces from? By sex with the back part where you pass feces from we mean when a male puts his penis inside the passage where you pass feces from. |

| Revised question (implemented April 2011) | Ezinyangeni ezintathu ezedlule, ngabe uye kangaki ocansini lwezinqe? Ngocansi lwezinqe ngisho uma indoda ifaka isitho sayo sangasese (ipipi) embobeni yezinqe zakho. | N/A | N/A |

| Literal English back-translation of revised question | In the past three months, how many times have you had sex in the buttocks? By sex in the bum/buttocks I mean when a man inserts his private part (penis) into your bum/buttocks. | N/A | N/A |

Following this recognition were extensive consultations and a process of group translation, resulting in the rephrasing of the PAI questions in Zulu, to be more specific without being offensive. During retranslation of the Zulu PAI question site staff rejected the terms ngquza and indunu (anus/ass), considering them vulgar and inappropriate, choosing instead the term ezinqeni (in the bum). The rephrased ACASI PAI question was implemented in April 2011, approximately 18 months after VOICE study initiation, and only two months before enrolment ended. After implementation of the retranslated terms in Zulu, baseline prevalence for PAI reporting in the past three months among newly enrolled Zulu-speaking participants decreased from 21% to 16%. Overall, baseline figures were 17% (N = 868) of all 5,029 participants reported PAI in the past three months (20% in South Africa, and 7% in both Uganda and Zimbabwe).

VOICE-D

VOICE-D was conducted in 2012 and 2013, after completion of the VOICE trial. Acknowledging the limitations of ACASI and the possibility that participants had not consistently understood the PAI question in VOICE, one of the aims of VOICE-D was to revisit how VOICE participants had understood and interpreted the terms used for PAI in the ACASI questions (for more details on VOICE-D, refer to www.mtnstopshiv.org/news/studies/mtn003d). Qualitative in-depth interviews (IDIs) were used to retrospectively unpack participants' understanding and interpretations of the language and terminology for PAI used in VOICE.

VOICE-D Sample

Based on preselected stratification criteria to ensure that at least 10% had reported engaging in PAI while participating in VOICE, and approximately 10% had acquired HIV during VOICE, exited VOICE participants who had given permission to be recontacted were invited by fieldworkers to enroll in VOICE-D. In all, 58 female participants from four locations (20 each from two sites in Durban, South Africa; 26 from Chitungwiza, Zimbabwe; and 22 from Kampala, Uganda) were enrolled into VOICE-D. Those participants who had previously reported PAI in ACASI were not alerted that this was a stratification criterion; interviewers were blind as to whether participants had reported PAI during VOICE; and the interviews were not targeted toward their specific reporting of the behavior.

Data Collection

Interviewers received study-specific training prior to data collection activities; one training session was devoted to sensitizing interviewers toward the topic of PAI and equipping them with the knowledge, skills, and techniques necessary to neutrally and comfortably discuss such a taboo topic in the interview environment. Interview guides were developed by the research team in English, translated into each of the local languages at study sites (Shona, Luganda and Zulu), and field-tested by site teams. Ethical approval for VOICE-D was obtained from institutional review boards and ethics committees at each of the implementing study sites in Zimbabwe, Uganda, and South Africa and collaborating institutions in the United States and in Cape Town, South Africa.

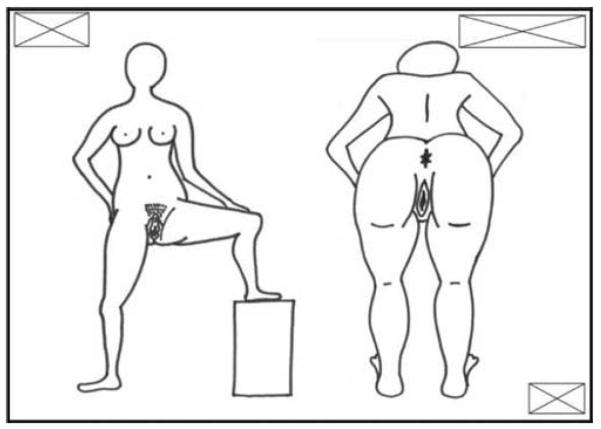

Interviews were conducted in participants' language of preference (Zulu, Luganda, Shona, or English), followed a semistructured format, and covered two topic areas: adherence to study products and PAI. The section of the interview covering PAI was initiated using a body-mapping activity, designed as an icebreaker to the topic of sex and as a visual aid to facilitate discussion and provide clarity on participants' anatomical knowledge and understanding of terms for various sex acts. The body map template consisted of a hand-drawn outline showing the front and back of a nude female figure (Figure 1). The template was intentionally simple, designed on the premise that participants, particularly those with low literacy, would not relate to a sagittal view diagram of the female anatomy. At the same time the template was intentionally graphic enough that it could be used to assess participants' anatomical knowledge and verify participants' understanding of the PAI question administered during VOICE ACASI. Following the body-mapping activity, questions on anal sex were introduced with a statement that almost 900 participants in VOICE had reported PAI during ACASI. After determining their comprehension of the definition of PAI, participants were asked open-ended questions relating to the behavior. Further, we examined participants' narratives of their own PAI experiences compared to their VOICE ACASI reports.

Figure 1.

Body map template used in VOICE-D.

Audio recordings from the IDIs underwent a process of transcription, review, translation into English, and secondary review before finalisation. A codebook was iteratively developed by the coding team reflecting the study's key objectives and themes that emerged through reading the data. Qualitative data were coded and analyzed using NVivo 10 (QSR International) by a team of four analysts; ≥ 80% intercoder reliability was established and verified on about 10% of the transcripts throughout the coding process.

Results

Basic demographic characteristics of the VOICE-D sample are presented in Table 2. The table also gives details of participants' reporting of PAI in VOICE's ACASI and VOICE-D's interviews. There was 65% (57/88) agreement, reporting similarly about PAI in both ACASI and IDIs, with 12 (14%) participants reporting PAI in both settings. In addition, 26% (23/88) said they had never engaged in PAI during their IDI, although they reported so during their ACASI. Finally, one-tenth of participants reported PAI in the IDI but not in ACASI.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of and PAI Reporting by VOICE-D Sample

| Demographic Characteristics | All Countries (N = 88) | South Africa (N = 40) | Uganda (N = 22) | Zimbabwe (N = 26) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 28.6 | 26 | 29.5 | 28.6 |

| Language spoken at home | ||||

| isiZulu | 35 (40%) | 35 (88%) | — | — |

| isiXhosa | 4 (5%) | 4 (10%) | — | — |

| English | 1 (1%) | 1 (3%) | — | — |

| Luganda | 19 (22%) | — | 19 (86%) | — |

| Shona | 26 (30%) | — | — | 26 (100%) |

| Other | 3 (3%) | — | 3 (14%) | — |

| Reporting of PAI | ||||

| YES in VOICE ACASI but NO in IDI | 23 | 13 | 3 | 7 |

| NO in VOICE ACASI but YES in IDI | 8 | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| YES in both VOICE ACASI & IDI | 12 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| NO in both VOICE ACASI & IDI | 45 | 16 | 13 | 16 |

The findings presented in the next section describe topics relating to the language, terminology, and understanding that emerged from analysis of the VOICE-D qualitative data. Direct quotations (translated) from participants are followed by parentheses detailing the participant's nationality and age. In cases of quoted conversation, R denotes the respondent and I denotes the interviewer.

Anal Sex Taboo

The social sensitivity of PAI was evident in the reactions that participants had to the introduction of the interview section addressing the behavior, with a majority of participants from all three countries displaying reactions such as shock, disgust, denial, disbelief, embarrassment, and surprise. Some participants asserted that discussing sex so openly was inappropriate, especially taboo behaviors like PAI: “Those are secrets for the bed” (Ugandan, age 39).

Participants from all three countries asserted that the topic of anal sex should not be openly discussed; discomfort was evident in women's verbal cues and body language. The language participants used to refer to PAI had largely negative associations. Zimbabwean participants used descriptive terms such as zvinosemesa (“disgusting”), hazviitwi (“not meant to be done that way”), hazvitaurwe (“not talked about”), and zvinonyadzisa (“shameful or embarrassing”). Ugandan participants used similarly negative language to talk about PAI, such as kya nsonyi (“embarrassing”) and ela ebyo biba bifu (“it is wrong”). Among South African participants, younger women were generally more comfortable talking about PAI, and four participants under 25 years of age admitted to enjoying PAI. Some of the older South African participants, however, displayed anger at being asked about such intimate aspects of their lives, even reprimanding the (younger) interviewer with the assertion that it is against “our culture” (the Zulu culture shared by the participant and interviewer) to discuss sex so openly.

The language participants used to describe PAI strongly associated the behavior with homosexuality. Almost all the Ugandans referred to anal sex as okulya ebisiyaga (“homosexuality”), saying you must be bisiyaga (“homosexual”) to have PAI. The Zimbabwean participants had similar associations, using terms like hungochani nzira yachona iyoyo (“having sex the homosexual way”) for PAI. The South African women used terms like ngabantu besilisa kuphela (“men only”) and izitabane (“gay”).

Comprehension

Use of the body-map template assisted in enabling interviewers to ascertain participants' comprehension of the PAI question and terminology. In all, 10 of 88 participants (South African, N = 2; Ugandan, N = 1; Zimbabwean, N = 7) expressed confusion over which anatomical location (vagina or anus) the PAI question was referring to and needed it to be clarified by the interviewer.

-

I:

Looking at this picture, when we say the man puts his penis through the anal hole of your body … where do you think he will put his penis?

-

R:

Through the front. Not through the place you excrete stool. (Zimbabwean, age 30)

During VOICE-D interviews, several participants admitted to realizing, only after comprehension had been clarified using the body-map template, what the PAI question in ACASI had referred to, stating that they had misinterpreted the question to refer to penile–vaginal intercourse (PVI) and reported accordingly.

All along I thought the “back part” being referred to was the position when a woman's back is bent over … then the man will put his private part (penis) here … at the back, but not the anus … I failed to understand this question when we were asked on ACASI … but it has become clear after this discussion … when we were using ACASI I didn't understand the meaning of that question … I was one of those who didn't understand what exactly the question meant … I thought maybe it's a sexual position in which the woman is bent over … then the men penetrate the women using the proper place (vagina) … That's how I understood it … I knew of my way of doing this (sex) … which is not what this question asked about … I answered this question under the impression that it was asking about vaginal sex in that bent position. (Zimbabwean, age 40)

A total of 14 of 88 of VOICE-D participants (South African, N = 2; Ugandan, N = 3; Zimbabwean, N = 9) stated that they had not understood the PAI question in VOICE's ACASI or had misinterpreted it to refer to PVI.

-

R:

They asked us (about sex using ACASI) but they never specified whether it was anal sex … we thought that then we would be bending over and the man passes behind you like this…. But they never really asked us about anal sex.

-

I:

… what you understood is a man “passing behind” but not using the anus?

-

R:

Yes, that is how I understood it … I answered yes because I had not understood its true purpose.

-

I:

So what you understood is the man passing behind to the vagina and not the anus?

-

R:

Yes, madam. (Ugandan, age 39)

A lack of comprehension was evident across participants from the three study countries, with greater lack of understanding demonstrated by Shona speakers. In some instances interviewers needed to use the body-map template to clarify that the translated terms for anal sex in ACASI were referring to the anus and not the vagina:

-

I:

When we say anal sex … what did it mean (to you), having sex from where?

-

R:

… Vagina, is that not what it was asking? … They were asking how many times from behind … meaning the vagina. (Zimbabwean, age 24)

During the IDIs, many participants used ambiguous terms that translate as “from behind,” “at the back,” and “pass behind,” demonstrating the lack of clear, explicit, acceptable terminology for PAI:

-

R:

I understood that he will be having sex from behind (vaginal doggy style), but not from the anus.

-

I:

Is there a name given to this act (anal sex) … that you know?

-

R:

Well, no, I just know that it is having sex from behind (vaginal doggy style), but here in this paper (body-map template) it specifies where the feces come from … “from behind” differs with where the feces come from. (Zimbabwean, age 30)

Interviewers had to probe participants using the body map to clarify precisely which part of the anatomy such terms referred to:

It (the ACASI question) meant I was to answer if during sex … we used the front or the back … “The back,” I don't mean he will be inserting his penis into my anus … I mean he will be inserting into my vagina from behind … That is what I understood this question was asking … when they say “from behind” … it doesn't mean he's inserting into my anus, but he's inserting into my vagina, but I would be bending. (Zimbabwean, age 27)

When informed that approximately 900 VOICE participants had reported PAI, some of the VOICE-D participants were of the opinion that this high number must have been a reporting error, due to a large proportion of women misunderstanding the question, interpreting it to refer to PVI, rather than indicating that many women had actually had PAI: “I think there was a mistake … most people thought you meant doggy style (vaginal sex from behind)” (Zimbabwean, age 27).

Local Terminology for Sex-Related Terms and Anal Sex

Participants generally used euphemistic language to refer to genitalia, such as “private parts.” To refer to the genital or anal areas, Zimbabwean participants used indirect terms like maparts acho akavanzika aya (“the hidden parts”), kuzasi (“down there”), pakati ipapo (“genital area”), and kumusuri “(where farting happens”). In reference to the vagina, Ugandan participants used terms in Luganda such as kakyala kabakazi (“lower thing”) or English terms such as “ordinary one” and “woman's part”; instead of referring to the anus, participants used words such as mukabina (“buttocks”). South African participants used terms like ushukela (“sugar”) and ekhekheni (“cake”) to refer to the vagina, as well as indirect terms for having sex, such as “do that thing.”

All of the terms that participants used to refer to the anus were ambiguous, such as “behind one” and “at the back,” unless used in conjunction with a phrase such as “where feces/stool passes,” for example, “A man can come from behind … he puts his thing in” (South African, age 39). Another respondent stated, “I think that (anal sex) is having sex when a man puts his penis behind a woman's back side, behind … in the buttocks … where the feces pass” (Ugandan, age 27).

Across all three languages, terms were used to signify PAI that translate as “sex from the back”:

-

R:

I mean having sex from the back.

-

I:

When you say “from the back,” what do you mean?

-

R:

The area where feces come out from. (Zimbabwean, age 31)

In Shona this was phrased as nekumashure or yekumashure ikoko (“sex from behind there”/“sex from the back”). As illustrated by the quotation that follows, there is no commonly used term equivalent to “anal sex” in Shona:

-

I:

When you were in VOICE, you were asked questions … referring to sex when a man's sexual organ (penis) penetrates a woman's anus … Do we have a Shona word or phrase to describe this type of sexual intercourse, apart from the way I am describing it?

-

R:

Um, we don't have such a word in Shona … I don't know … I've never heard of it. (Zimbabwean, age 31)

Participants from all language groups used English terms such as “doggy style” or “dog style” to refer to vaginal sex from behind. Table 3 demonstrates the lack of unambiguous, precise, and acceptable terms for “anus” in Luganda, Shona, and Zulu.

Table 3.

Anogenital-Related Terms in Luganda, Shona, and Zulu

| Terms | Possible Meanings | Acceptability/Ambiguity |

|---|---|---|

| Luganda | ||

| akabina | Buttocks/behind | Impolite but not deeply offensive; ambiguous |

| ekinyo/ekinnyo | Anus/vagina/tooth (negative connotations of being big/ugly) | Offensive and ambiguous |

| okupama (okunia) | Defecate/pass feces | Impolite |

| omunio/omunyo/ekinio | Feces/anus (in certain contexts) | Offensive |

| ettako | Buttocks/bum | Offensive |

| Shona | ||

| mhata | Buttocks/vagina (depending on dialect) | Acceptable but ambiguous and unspecific |

| mukosho | Anus/asshole | Acceptable to Karanga ethnolinguistic subgroup but offensive to others |

| kumashure | “At the back” | Acceptable but ambiguous |

| mukodo/mufongo | Sexual intercourse “from the back”/dog style | Ambiguous—can be interpreted as PAI or PVI |

| kudhodhana | Asshole (derived from fecal matter) | Offensive |

| dako | Buttocks/bums | Impolite |

| Mudhidhi/horo/mutinhi/mupedzazviyo | Anus/hole | Ambiguous |

| Zulu | ||

| ezinqeni | Bum/buttocks | Acceptable but ambiguous |

| umqundu/ngquza/umdidi | Asshole | Offensive |

Discussion

The findings from VOICE-D interviews conducted with 88 women illustrate the extent to which PAI is a socially stigmatized taboo behavior in this sample of South African, Ugandan, and Zimbabwean women, and that local terms used to designate PAI are highly ambiguous. Terminology referring to sexual behavior and genitalia tends to be euphemistic and vague, and widely used slang terms such as “doggy style,” used by participants in all three countries, can be interpreted to mean either penile–vaginal sex from behind or penile–anal sex (Mavhu, Langhaug, Manyonga, Power, & Cowan, 2008; Stadler, Delany, & Mntambo, 2007). The terms used in the VOICE ACASI question on PAI were interpreted by participants in all three countries to refer to PVI, which may in part account for the high levels of reporting of PAI. The rephrasing of the Zulu ACASI PAI question resulted in slightly lower reporting. It is likely that participants' understanding, or lack thereof, of the PAI question was only one factor accounting for the reported level of PAI during VOICE.

Misinterpretation of Research Terms

Data accuracy is jeopardized when research participants misinterpret questions (O'Sullivan, 2008). Many researchers investigating sexual behavior have made assumptions about how participants interpret terms for sexual acts, without unpacking the nuances in sexual behavior terminology and the effects these have on data (Duby & Colvin, in press). Even when research terms have been carefully selected and instruments field-tested there is scope for ambiguity. In VOICE-D, some participants retrospectively reported answering the PAI question in ACASI based on their understanding that it referred to vaginal sex. ACASI does not provide opportunity for identifying inattention or miscomprehension, and data inaccuracies arise when participants misinterpret items. Participants are unlikely to admit when they do not understand terms or questions, or they may interpret terms differently than researchers intended (Binson & Catania, 1998). FTFI methods have the benefit of interaction between interviewer and participant, which can build rapport and trust between interviewer and participant and provide an opportunity for identifying participant miscomprehension or inconsistency (Mitchell et al., 2007; Parker, Herdt, & Carballo, 1991; Plummer et al., 2004). Nonetheless, it is often not possible to distinguish between misinterpretation of questions and intentional misreporting.

Understanding the Cultural Context

Despite pretesting ACASI instruments, sensitive sexual behavior terms were misunderstood. Pretesting research tools does not necessarily ensure the terms are easy to comprehend; endeavoring to understand the cultural context in which research is being conducted is critical (Mavhu et al., 2008). Cross-cultural translation of research terms is subject to the cultural equivalence factor, referring to the way in which members of different cultural and linguistic groups perceive or interpret meanings. Local culture and norms may affect the way in which research participants interpret and respond to research questions (Peña, 2007). As illustrated by VOICE-D participants' reactions to the body-mapping activity and responses to questions, there are linguistic cultural restrictions around sexual communication and cultural prohibition of open discussion of sexual behavior in many African contexts, including South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe (Eaton, Flisher, & Aarø, 2003; Fandrych, 2012; Vos, 1994). Discussion about excretory and sexual organs is considered obscene and offensive in Shona-, Luganda-, and Zulu-speaking contexts (Chabata & Mavhu, 2005; Mabaso, 2009; Mangoya, 2009; Storch, 2011). Terms for genitalia and sexual behaviors, particularly in the vernacular, tend to be euphemistic, ambiguous, and nonspecific in most African languages (Bell & Aggleton, 2012; Xaba, 1994).

Our study illustrates the lack of clarity around sexual behavior terms commonly used in sexual behavior survey instruments, and highlights the challenges in selecting explicit, anatomically accurate, nonambiguous terms that are translatable and locally understood. Literal and direct translations of sexual behavior or anatomy terms from English can be considered offensive and vulgar. As a result, achieving exact translation while retaining meaning is not always possible (McCombie & Ssebbanja, 1991). In cases where there is no clear equivalent translation, modification of words and concepts by translators is generally considered acceptable, particularly when terms are deemed to be socially insensitive (Maneesriwongul & Dixon, 2004). Linguistic taboos around sex mean that translators often choose ambiguous terminology, avoiding direct translation of terms for genitalia and sexual behaviors, which would be considered obscene, even in materials providing information on sexual health (Ndlovu, 2009). Efforts to be culturally appropriate cause ambiguities to arise where polite socially acceptable terms have been chosen to avoid causing offense or discomfort to participants, especially when these terms are not explicit or precise (Cain et al., 2011); VOICE-D findings demonstrate the potential for confusion, resulting in questionable data. The misinterpretation of the ACASI PAI question by VOICE participants may have resulted from the lack of culturally acceptable or commonly used terms for PAI in the participants' languages.

Even when precise and unambiguous terms are used, due to social desirability bias, there is a strong likelihood of under-reporting with regards to socially stigmatized behaviors. As demonstrated by VOICE-D, this is particularly the case in sub-Saharan Africa, where social codes relating to sexual behavior tend to be conservative and restrictive, compounded by the criminalization of PAI in Uganda and Zimbabwe (Mavhu et al., 2008). The cultural sensitivity of sexual communication and social stigmatization of PAI are likely to have introduced social desirability bias into the reporting of PAI in VOICE as well as in VOICE-D. In the absence of biomarkers, it is not possible to determine the accuracy of the overall level of PAI reported in ACASI during VOICE.

Limitations

Regardless of reporting methods, participants may deliberately misinform or mislead researchers (Turner et al., 2009). Despite the efforts of the interviewers to encourage candid discussion, given VOICE-D participants' assertion that anal sex is not openly discussed, they may have been reluctant to admit PAI and may have claimed they misunderstood what was meant by PAI in VOICE when in fact they had understood. IDIs are subject to social desirability too, and some participants may have been unwilling to discuss or disclose PAI for that reason.

Recommendations

Accurate and Standardized Translation of Research Terms

Attention to language is crucial in the design of study tools. Selection of words and terms, as well as phrasing of questions, affects participants' comprehension, interpretation, and responses, and also impacts on how much or how little participants choose to disclose (Frith, 2000). To increase accuracy and consistency in interpretations, questions and terminology should be as clear, comprehensible, and unambiguous as possible. That being said, the Shona and Luganda phrasing of the PAI questions in VOICE were explicit, using the phrase “where stool/faeces passes,” yet there was still misinterpretation. In recognition of the potential limitations of using formal language, some researchers have explored the method of using colloquial or slang terms, or asking participants to come up with their own terms. However, this has proved problematic, because slang can vary considerably depending on a participant's regional dialect or social grouping (Binson & Catania, 1998). As results from VOICE-D demonstrate, recommended techniques such as cognitive interviewing and group translation (Mack et al., 2013) are imperfect. One solution may be the development of bi-/multilingual lexicons to ensure consistency and standardization in translated terminology. Ramirez and colleagues (2013) suggested a process for eliciting and field-testing culturally and linguistically valid translations for use in the research setting.

Use of Visual Aids

In addition to clear and unambiguous language, visual aids can assist in assessing a participant's understanding of questions and terms. For socially sensitive topics, a visual aid can reduce participant discomfort; using the body-map template enabled VOICE-D participants to indicate anatomical areas without having to verbalize the words. Two-dimensional pictures alongside text have successfully been used to improve comprehension of health messages in health education campaigns (Dowse, Ramela, Barford, & Browne, 2010). However, visual aids may also be interpreted differently depending on the literacy levels of the audience and the cultural context. Visual tools for low-literacy populations should be as accurate and lifelike as possible, while being simple and not overly scientific (Dowse et al., 2010), as was attempted in the VOICE-D body-map template. All visual aids should be well researched prior to development; target audiences should be consulted in the development process to ensure that they are contextually relevant; and they should undergo field-testing to ensure their comprehensibility. Evidence suggests that pictorial tools should not replace text or verbal discussion but can be used in conjunction with text, to avoid misinterpretation (Katz, Kripalani, & Weiss, 2006).

Understanding the Cultural Context of Research

Achieving a balance between the acceptability of research terms and their ambiguity can be challenging. Questions on PAI are regularly excluded from surveys and research instruments out of concern that participants will take offense or because interviewers feel unable to ask about it (Mavhu et al., 2008). In the case of socially undesirable or taboo behaviors, it is important to understand the cultural context, which may shape interpretation and response to sensitive questions (Tourangeau & Smith, 1996). The more explicit and literal terms are, the more likely they are to be deemed inappropriate and offensive. Efforts to achieve unambiguity and clarity are likely to come up against cultural taboos; for example, research staff are likely to be subject to the same cultural taboos as participants and may feel uncomfortable using explicit terminology and diagrams. Researchers need to carefully balance the need for not causing offense, distress, or embarrassment, which may be deemed unethical, with the need for data accuracy.

Multimethods Research

The accuracy of participants' self-reporting should never be taken for granted; therefore, triangulating data collection methods for purposes of cross-checking is advisable. Multimethod studies incorporating longitudinal qualitative IDIs alongside methods such as ACASI in future HIV prevention trials might assist in unpacking participants' experiences, sexual practices, relationship dynamics, and the social context of these. IDIs conducted while the study is ongoing, may help to identify miscomprehension of terminology. In addition, multiple interviews over time can give the opportunity for interviewers to build rapport with participants, which may counteract participants' unwillingness to disclose socially stigmatized behaviors such as PAI. As processes such as sexual decision making can be difficult to explain through one-off interviews, the use of multiple interviews over time with the same participants allows for participants' reflection and gradual increased disclosure, and can shed light on complex decision-making processes and underlying motives for sexual behavior (Collumbien, Busza, Cleland, & Campbell, 2012). Additional tools such as diaries, diagrams, visual aids, and body maps may assist in reporting or assessing participants' comprehension of terms and can be used as part of the interview process.

Conclusions

The findings from VOICE-D suggest that there may have been misreporting of PAI by VOICE participants due to misinterpretation and social desirability bias. Despite efforts to make the anal sex terms in VOICE's ACASI accurate, their meaning was frequently misinterpreted by participants to refer to vaginal sex from behind. The issue of under-reporting of sexual behaviors due to social desirability bias is likely to remain even as clear unambiguous terms are found. The issue of inaccurate reporting of sexual behaviors due to miscomprehension of terms also has roots in stigma and taboo, since veiled and ambiguous language around PAI makes clear communication difficult. These findings highlight the challenges in developing sexual behavior terms for data collection instruments that strike a balance between being unambiguous and specific while being culturally acceptable and socially appropriate. Clinical trials that have a longitudinal qualitative component running alongside the quantitative component are more likely to build a comprehensive picture of participants' sexual lives, perceptions and experiences.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the women who participated in this study, as well as all those who gave valuable input into the complex nuances and ambiguities of Luganda, Shona, and Zulu. The full MTN-003D study team can be viewed at http://www.mtnstopshiv.org/studies/4493. The study was designed and implemented by the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN). The MTN is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UM1AI068633, UM1AI068615, UM1AI106707), with cofunding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health, all components of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

ORCID Zoe Duby http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7615-8152

References

- Baker DL, Melnikow J, Ying Ly M, Shoultz J, Niederhauser V, Diaz Escamilla R. Translation of health surveys using mixed methods. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2010;42:430–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01368.x. doi:10.1111/jnu.2010.42.issue-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SA, Aggleton P. Time to invest in a “counterpublic health” approach: Promoting sexual health amongst sexually active young people in rural Uganda. Children's Geographies. 2012;10:385–397. doi:10.1080/14733285.2012.726066. [Google Scholar]

- Binson D, Catania JA. Respondents' understanding of the words used in sexual behavior questions. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1998;62:190–208. doi:101086/297840. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology. 1970;1:185–16. doi:10.1177/135910457000100301. [Google Scholar]

- Cain D, Schensul S, Mlobeli R. Language choice and sexual communication among Xhosa speakers in Cape Town, South Africa: Implications for HIV prevention message development. Health Education Research. 2011;26:476–488. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq067. doi:10.1093/her/cyq067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA. A framework for conceptualizing reporting bias and its antecedents in interviews assessing human sexuality. Journal of Sex Research. 1999;36:25–38. doi:10.1080/00224499909551964. [Google Scholar]

- Chabata E, Mavhu WM. To call or not to call a spade a spade: The dilemma of treating “offensive” terms in Duramazwi Guru reChiShona. Lexicos. 2005;15:253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Cleland J, Boerma JT, Carael M, Weir SS. Monitoring sexual behaviour in general populations: A synthesis of lessons of the past decade. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2004;80(Suppl. 2):ii1–ii7. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.013151. doi:10.1136/sti.2004.013151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collumbien M, Busza J, Cleland J, Campbell O. Social science methods for research on sexual and reproductive health. UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction; Geneva, Switzerland: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dowse R, Ramela T, Barford K-L, Browne S. Developing visual images for communicating information about antiretroviral side effects to a low-literate population. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2010;9:213–224. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2010.530172. doi:10.2989/16085906.2010.530172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duby Z, Colvin CJ. Defining sex, virginity and abstinence: Where does anal sex fit in and what are the implications for HIV prevention? in press. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton L, Flisher AJ, Aarø LE. Unsafe sexual behaviour in South African youth. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;56:149–165. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00017-5. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fandrych I. Between tradition and the requirements of modern life: Hlonipha in Southern Bantu societies, with special reference to Lesotho. Journal of Language and Culture. 2012;3:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Frith H. Focusing on sex: Using focus groups in sex research. Sexualities. 2000;3:275–297. doi:10.1177/136346000003003001. [Google Scholar]

- Gorbach PM, Mensch BS, Husnik M, Coly A, Mâsse B, Makanani B, Forsyth A. Effect of computer-assisted interviewing on self-reported sexual behavior data in a microbicide clinical trial. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17:790–800. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0302-2. doi:10.1007/s10461-012-0302-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett PC, Mensch BS, de Almeida Ribeiro MCS, Jones HE, Lippman SA, Montgomery MR, van de Wijgert JHJM. Using sexually transmitted infection biomarkers to validate reporting of sexual behavior within a randomized, experimental evaluation of interviewing methods. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;168:202–211. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn113. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaya, Hindin MJ, Ahmed S. Differences in young people's reports of sexual behaviors according to interview methodology: A randomized trial in India. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(1):169–174. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099937. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.099937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim SS, Ramjee G. Anal sex and HIV transmission in women. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1265–1266. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.8.1265-a. doi:10.2105/AJPH.88.8.1265-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz MG, Kripalani S, Weiss BD. Use of pictorial aids in medication instructions: A review of the literature. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2006;63:2391–2397. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060162. doi:10.2146/ajhp060162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai K, Kaaya SF, Kajula L, Mbwambo J, Kilonzo GP, Fawzi WW. Parents' and teachers' communication about HIV and sex in relation to the timing of sexual initiation among young adolescents in Tanzania. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2008;36:879–888. doi: 10.1177/1403494808094243. doi:10.1177/1403494808094243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhaug LF, Sherr L, Cowan FM. How to improve the validity of sexual behaviour reporting: Systematic review of questionnaire delivery modes in developing countries. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2010;15:362–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02464.x. doi:10.1111/tmi.2010.15.issue-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabaso P. The compilation of a Shona children's dictionary: Challenges and solutions. Lexikos. 2009;19(1) doi:10.4314/lex.v19i2.49171. [Google Scholar]

- Mack N, Ramirez CB, Friedland B, Nnko S. Lost in translation: Assessing effectiveness of focus group questioning techniques to develop improved translation of terminology used in HIV prevention clinical trials. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e73799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073799. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maneesriwongul W, Dixon JK. Instrument translation process: A methods review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;48:175–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03185.x. doi:10.1111/jan.2004.48.issue-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangoya E. Target users' expectations versus the actual compilation of a Shona children's dictionary. Lexikos. 2009;19 doi:10.4314/lex.v19i2.49172. [Google Scholar]

- Marrazzo JM, RAMJEE G, Richardson BA, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, Chirenje ZM. Tenofovir-based pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:509–518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1402269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mâsse BR, Boily M-C, Dimitrov D, Desai K. Efficacy dilution in randomized placebo-controlled vaginal microbicide trials. Emerging themes in epidemiology. Emerging Themes in Epidemiology. 2009;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-6-5. doi:10.1186/1742-7622-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavhu W, Langhaug L, Manyonga B, Power R, Cowan F. What is “sex” exactly? Using cognitive interviewing to improve the validity of sexual behaviour reporting among young people in rural Zimbabwe. Culture, Health, and Sexuality. 2008;10:563–572. doi: 10.1080/13691050801948102. doi:10.1080/13691050801948102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCombie S, Ssebbanja P. Talking about sex and partners in Luganda: Issues for questionnaire translation [AIDSCOM field note] Academy for Educational Development. 1991 Retrieved from http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNABL814.pdf.

- Mensch BS, Hewett PC, Abbott S, Rankin J, Littlefield S, Ahmed K, Cassim N, Skoler-Karpoff S. Assessing the reporting of adherence and sexual activity in a simulated microbicide trial in South Africa: An interview mode experiment using a placebo gel. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15:407–421. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9791-z. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9791-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnis AM, Steiner MJ, Gallo MF, Warner L, Hobbs MM, van der Straten A, Padian NS. Biomarker validation of reports of recent sexual activity: Results of a randomized controlled study in Zimbabwe. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;170:918–924. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp219. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell K, Wellings K, Elam G, Erens B, Fenton K, Johnson A. How can we facilitate reliable reporting in surveys of sexual behaviour? Evidence from qualitative research. Culture, Health, and Sexuality. 2007;9:519–531. doi: 10.1080/13691050701432561. doi:10.1080/13691050701432561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndlovu MV. The accessibility of translated Zulu health texts: An investigation of translation strategies (Doctoral thesis) University of South Africa; Pretoria, South Africa: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan LF. Editorial: Challenging assumptions regarding the validity of self-report. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:207–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.002. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker RG, Herdt G, Carballo M. Sexual culture, HIV transmission, and AIDS research. Journal of Sex Research. 1991;28:77–98. doi:10.1080/00224499109551596. [Google Scholar]

- Peña ED. Lost in translation: Methodological considerations in cross-cultural research. Child Development. 2007;78:1255–1264. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01064.x. doi:10.1111/cdev.2007.78.issue-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer ML, Ross DA, Wight D, Changalucha J, Mshana G, Wamoyi J, Hayes RJ. “A bit more truthful”: The validity of adolescent sexual behaviour data collected in rural northern Tanzania using five methods. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2004;80(Suppl. 2):ii49–ii56. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.011924. doi:10.1136/sti.2004.011924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez C, Mack N, Friedland AB. A toolkit for developing bilingual lexicons for international HIV prevention clinical trials. Population Council and FHI360; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rasinski KA, Willis GB, Baldwin AK, Yeh W, Lee L. Methods of data collection, perceptions of risks and losses, and motivation to give truthful answers to sensitive survey questions. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 1999;13:465–484. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1099-0720. [Google Scholar]

- Schroder KE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: II. Accuracy of self-reports. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26:104–123. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2602_03. doi:10.1207/S15324796ABM2602_03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler JJ, Delany S, Mntambo M. Sexual coercion and sexual desire: Ambivalent meanings of heterosexual anal sex in Soweto. South Africa. AIDS Care. 2007;19:1189–1193. doi: 10.1080/09540120701408134. doi:10.1080/09540120701408134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch A. Secret manipulations: Language and context in Africa. Oxford University Press; New York NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau R, Smith TW. Asking sensitive questions: The impact of data collection mode, question format, and question context. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1996;60:275–304. doi:10.1086/297751. [Google Scholar]

- Turner AN, De Kock AE, Meehan-Ritter A, Blanchard K, Sebola MH, Hoosen AA, Ellertson C. Many vaginal microbicide trial participants acknowledged they had misreported sensitive sexual behavior in face-to-face interviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62:759–765. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.07.011. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos T. Attitudes to sex and sexual behaviour in rural Matabeleland, Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 1994;6:193–203. doi: 10.1080/09540129408258630. doi:10.1080/09540129408258630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wight D, Plummer ML, Mshana G, Wamoyi J, Shigongo ZS, Ross DA. Contradictory sexual norms and expectations for young people in rural Northern Tanzania. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:987–997. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.052. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xaba M. And what do Zulu girls have? Agenda. 1994;10:33–35. doi:10.2307/4065944. [Google Scholar]