Abstract

(1) To study the different patterns of presentations of tuberculosis in Head and Neck region. (2) To know the importance and reliability of ESR and Mantoux test as an aid in diagnosis of tuberculosis. This study was conducted at Department of ENT and Head and Neck Surgery, Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh from January 2014 to June 2015. Patients presenting with lesions in the Head and Neck region suspected of tuberculosis were subjected for cytological and histological investigations. Those cases confirmed to be tuberculosis on the basis of either of these tests were included in the study. Study comprised of 113 proven cases of tuberculosis of Head and Neck region. A female preponderance of 1:1.97 (M:F) ratio was noted. Most commonly involved structure was cervical lymph node (92.92 %) followed by larynx, skin and oral mucosa (1.76 %). It was also noted that Mantoux test was positive in 93.8 % of patients and ESR was >30 mm (first hour) in 95.5 % of patients with tuberculosis. Most common presentation of Tuberculosis in Head and Neck area was cervical lymphadenopathy. In a developing country like India the population is mostly in the lower socioeconomic strata. Access to various modern investigations is limited and diagnosis is challenging. Here ESR and Mantoux test are helpful in purusing the case for further evaluation. Based on these pointers cytologically negative cases can be taken up for biopsy.

Keywords: Extrapulmonary TB, TB in Head and Neck, Mantoux test, TB larynx, Uncommon presentations of TB

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) continues to intimidate human race since time immemorial not only due to its effects as a medical malady, but also by its impact as a social and economic tragedy. Tuberculosis is the most common cause of death world over due to a single infectious agent in adults and accounts for over a quarter of all avoidable deaths globally [1]. Extrapulmonary involvement can occur in isolation or along with a pulmonary focus as in the case of patients with disseminated tuberculosis [2]. India is the country with the highest burden of TB, with World Health Organisation (WHO) statistics for 2013 giving an estimated incidence figure of 2.1 million cases of TB for India out of a global incidence of 9 million. The estimated TB prevalence figure for 2013 is given as 2.6 million [3].

Cervical lymphadenopathy is the most common manifestation of extra-pulmonary TB [2]. This type of presentation is a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to the clinician as it mimics other pathological conditions, often requiring biopsy for definitive diagnosis. A complete history including that of contact, physical examination, staining for acid fast bacilli (AFB), fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) and biopsy wherever indicated are helpful in clinching early diagnosis.

Although literature is available on various aspects of this disease, not many have reported the various presentations (other than cervical lymphadenopathy) of tuberculosis in the head and neck region. Objective of this study was to find out the various patterns of presentation of tuberculosis in head and neck region and the challenges faced in arriving at the diagnosis. Other variables like age and sex distribution, role of certain investigations like ESR, Mantoux test were also studied.

Materials and Methods

This clinical study was conducted in the Department of ENT, Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal between January 2014 to June 2015. Patients presenting with lymph node enlargement in the Head and Neck region suspected of tuberculosis were subjected for FNAC. Lesions other than lymph nodes were taken up for biopsy. Simultaneously routine blood investigation along with erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and Mantoux test was performed.

Patients positive for tuberculosis on FNAC of lymph nodes were included in the study. Patients in whom FNAC was negative even second time were taken up for biopsy on grounds of strong clinical suspicion, raised ESR and positive mantoux test. Those patients with lymph node positive for tuberculosis on biopsy were also included. Other lesions of laynx, skin and oral ulcer which were proven to be tubercular on biopsy were also included. Chest radiograph and ultrasonography of neck and abdomen were done in all these patients.

All patients were registered and started with directly observed treatment, short course (DOTS).

Observations

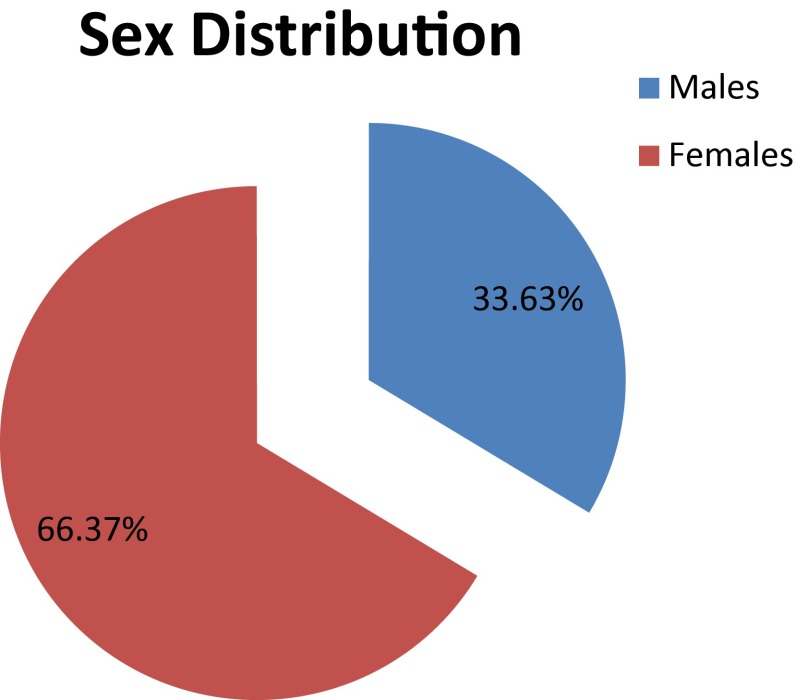

A total of 113 patients were included in the study. There were 38 males and 75 females with a ratio of 1:1.97 (Chart: 1).

Chart 1.

Sex distribution

Most common age group affected was 21–30 years followed by 11–20 (Table 1). The mean age was 27.33. Youngest was a 3 year old child and oldest patient was 70 years.

Table 1.

Age distribution

| Age group | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 09 | 7.96 |

| 11–20 | 32 | 28.31 |

| 21–30 | 37 | 32.74 |

| 31–40 | 21 | 18.48 |

| 41–50 | 06 | 5.30 |

| >51 | 08 | 7.07 |

The time interval between onset of symptoms and time of consultation varied from 7 days to 3 months.

Tuberculous cervical lymphadenopathy was the commonest presentation. Cervical lymphadenopathy was seen in 105 cases out of 113 (92.92 %). Posterior triangle lymph nodes were more commonly involved, followed by upper deep cervical and submandibular. Clinical examination and ultrasonography of the neck revealed multiple matted nodes in 68 patients, multiple discrete nodes in 23 patients and single discrete node in 14 patients. 10 out of 105 nodes presented as cold abscess. 7 out of 105 patients had axillary lymph node and 4 out of 105 patients had inguinal nodes in addition to cervical nodes. These patients were found to have pulmonary tuberculosis (sputum positive) along with HIV co-infection.

There were 2 cases of laryngeal tuberculosis with pulmonary tuberculosis. 2 cases of ulcer over the buccal mucosa were positive for tuberculosis on biopsy (Fig. 1). Cutaneous tuberculosis was found in 2 cases where skin of the neck in one and tip of nose in other was involved (Fig. 2). One patient had a granulomatous lesion of nose which came out to be tuberculosis on biopsy. Another patient a 14 year old girl who presented with a history of ear discharge for 2 years was found to have polypoidal mass in left ear with multiple neck scars (Fig. 3). She was taken up for mastoidectomy and the tissue sent from the mastoid was histopathologicaly positive for tuberculosis (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Tubercular ulcer left buccal mucosa

Fig. 2.

Cutaneous tuberculosis (Lupus Vulgaris)

Fig. 3.

Aural Tuberculosis with multiple inconclusive lymph node biopsies

Table 2.

Anatomical structures involved in Head and Neck

| Structure | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Lymph nodes | 105 | 92.92 |

| Larynx | 02 | 1.76 |

| Skin (cutaneous) | 02 | 1.76 |

| Oral cavity (ulcer) | 02 | 1.76 |

| Nose | 01 | 0.88 |

| Middle ear and mastoid | 01 | 0.88 |

A total of 90 out of 105 (85.7 %) patients with lymph nodes were diagnosed by FNAC (80 in first and 10 in repeat FNAC). Remaining 15 (14.3 %) patients were taken up for lymph node excision and were diagnosed by histopathology after FNAC was inconclusive.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was raised in 108/113 patients. It was more than 30 mm in the first hour in most. Mantoux test was positive in 106/113 patients and was negative in 7. Majority of the patients read 15–20 mm of induration at the end of 72 h (Table 3). Chest radiograph suggestive of tuberculosis were seen in 15/113 of the cases.

Table 3.

Mantoux test results

| Reading after 72 h | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| >20 mm | 19 |

| 15–20 mm | 72 |

| 10–15 mm | 15 |

| <10 | 07 |

Discussion

Tuberculosis, “Captain of all these men of death”, as referred to by John Bunyan in the 18th century is still the biggest health challenge of the world. It is known that 1.5 % of India’s population is affected with tuberculosis [7]. Extrapulmonary involvement can occur in isolation or along with a pulmonary focus as in the case of patients with disseminated tuberculosis (TB). EPTB constitutes about 15–20 per cent of all cases of tuberculosis in immunocompetent patients [2].

Peripheral lymph nodes are the commonest presentation of extrapulmonary TB and cervical group of nodes are the commonest among them. Historically, lymph node tuberculosis (LNTB) has been called the “King’s evil” referring to the divine benediction which was presumed to be the treatment for it. It was also referred to as “scrofula” meaning “glandular swelling” (Latin) and “full necked sow” (French) [4]. Peripheral lymph nodes are most often affected and cervical involvement is the most common among them [4–6].

In the present study we included 113 confirmed cases of tuberculosis involving one or the other structures of head and neck area. Male to female ratio was 1:1.97 showing significant female preponderance. Female predilection has also been reported in some other studies [9–13]. Male to female ratio was found to be 1:1.13 by Jha et al. 1:1.2 by Dandapat et al. and 1:1.3 by Subrahmanyam (1:1.3) [7, 9, 10]. The reason for female predominance could probably be due to their poorer nutritional status in a male dominated society and lack of exposure to sunlight resulting from ‘purdah system’(putting a veil over the face and covering all the body parts) being followed both by muslims and hindus in most parts of India [21].

Out of the total of 113 cases of tuberculosis 105 cases (92.92 %) were those of tubercular cervical lymphadenitis making it the most common presentation in head and neck region. Iqbal et al. and Jha et al. in their study also found cervical lymph nodes to be the most commonly involved structures outside the lungs [7, 8]. In India and other developing countries lymph node TB continues to be the most common form of extrapulmonary TB and lymphadenitis due to non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) is seldom seen [9–11]. In the present study posterior triangle lymph nodes were the most common cervical lymph nodes to be involved whereas it was upper deep cervical lymph nodes which were commonly involved in the study done by Jha et al. [7]. Lymph node tuberculosis commonly affects children and young adults [2, 6, 9, 10]. In the present study 41 cases were below the age of 20 years out of which 40 had cervical lymph node tuberculosis and 1 case was that of laryngeal tuberculosis.

In this study authors had 2 patients presenting with hoarseness of voice and odynophagia. One patient was a gravida two with a neglected cough presented only when the hoarsness of voice developed. The other patient was a 12 year old boy, who presented with a history of gradually progressive stridor. Fiber optic laryngoscopic examination revealed granulomatous lesion involving posterior part of larynx. Biopsies taken from these lesions were proved to be tubercular. Both the patients had evidence of pulmonary tuberculosis, since the cough had been ignored they presented with laryngeal symptoms. Laryngeal tuberculosis is a rare clinical entity and recent incidence of laryngeal tuberculosis is less than 1 % of all tuberculosis cases [14]. Involvement of larynx in tuberculosis occurs secondary to pulmonary tuberculosis. Primary involvement of larynx is rare [15].

In the current study authors encountered 2 cases of cutaneous tuberculosis out of which one of the patients a 15 year old boy developed a non healing ulcer (2 months) after a fall. It involved the tip of nose and adjoining area of upper lip and other case had involved skin of neck of posterior triangle. Both skin lesions were diagnosed on biopsy, to be lupus vulgaris. Cutaneous tuberculosis accounts for 0.11–2.5 per cent of all patients with skin diseases [16–20]. Lupus vulgaris is the most common variety seen in India followed by tuberculosis verrucosa cutis and scrofuloderma [16–20].

The oral cavity is an uncommon site of involvement of tuberculosis. Infection in the oral cavity is usually acquired through infected sputum coughed out by a patient with open pulmonary tuberculosis or by haematogenous spread. Tongue is the most common site of involvement and accounts for nearly half of the cases [2]. Authors came across two cases of TB involving oral cavity in the study. One was a 45 year old man with an ulcer of the tongue and another was a 43 year old man with an ulcer over the buccal mucosa. In both these patients biopsy of the non healing ulcers revealed tuberculosis. The patient having tongue ulcer also had smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis.

Nasal tuberculosis was found in a 35 year old lady who presented with a history of partial nasal obstruction, hyposmia and occasional nasal bleeding since 6 months. This patient was taken up for diagnostic nasal endoscopy. Biopsy was taken from the ulcerative lesion seen over the inferior turbinate and anterior part of septum proved to be tuberculosis. Tuberculosis of the nose can cause complications like septal perforation, atrophic rhinitis and scarring of nasal vestibule [2]. Here early diagnosis can prevent all these nasal complications. Our patient had dramatic improvement in symptoms within 2 months of antitubercular therapy.

Tuberculosis of the temporal region is a rare entity and very few cases are reported in recent time. In the present study a 14 year old girl presented with the history of blood stained ear discharge and aural fullness of left ear since 2 years. She had multiple discrete cervical nodes and scar marks on the ipsilateral side of neck. She also gave history of visiting multiple ENT surgeons and had undergone biopsies twice of the tissue in the ear and thrice of cervical lymph nodes. Along the course she had developed grade II facial nerve palsy of left side. Modified radical mastoidectomy was done; the whole of middle ear was filled with proliferative mass. There was erosion of the mastoid walls, lateral semicircular canal and fallopian canal in the mastoid segment. Multiple bits of tissue sent for histopathology was reported to be tubercular. Her mastoid cavity became healthy and facial nerve recovered completely after 4 months of starting anti-tubercular therapy.

In countries like India where tuberculosis is highly endemic, tuberculin skin test result alone is not sufficient evidence to diagnose EPTB in adult patients [2]. Though it may not help in diagnosis of TB it can be used as an adjunct to other definitive investigation. In our study 106 out of 113 had positive tuberculin skin test results. ESR was raised and was more than 30 mm in first hour in all but 5 cases. In our study 80 patients with lymph nodes were diagnosed to be TB in first FNAC. On clinical suspicion, positive mantoux tuberculin test and raised ESR the remaining 25 patients were subjected to repeat FNAC out of which 10 came out to be positive and rest were diagnosed after lymph node excision biopsy. ESR and Mantoux test cannot be used as a diagnostic tool but can be helpful in pursuing the cases and subjecting the patient for further investigation on strong clinical suspicion.

Conclusion

In our study we have seen cervical lymphadenopathy as the commonest presentation of tuberculosis in the Head and Neck region. Other lesions in the larynx, skin, oral mucosa, ear and nose were rare presentations but still found. In times of HIV–TB co-infection, presence of multidrug resistant tuberculosis, rampant use of immunosuppressive and immunomodulator drugs the clinical picture may be altered. This is a diagnostic challenge and surgeons should be aware of these areas of involvement of tuberculosis even in the present era. In centres with limited resources ESR and mantoux test are still useful tools in coming to a diagnosis.

Funding

There is no funding involved. All the investigations required for the study were done free of cost in our institution.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Both the authors declare that there is no conflict of interest in the present study.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Contributor Information

J. K. Yashveer, Email: yash045@yahoo.com

Y. K. Kirti, Email: kittoo24@yahoo.co.in

References

- 1.Sharma SK, Mohan A. Tuberculosis. 2. India: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2003. pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma SK, Mohan A. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res. 2004;120(4):316–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Tuberculosis Control (2014) WHO, Geneva. www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/. Accessed 13 Sept 2015

- 4.Kumar A. Lymph node tuberculosis. In: Sharma SK, Mohan A, editors. Tuberculosis. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2001. pp. 273–284. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appling D, Miller HR. Mycobacterial cervical lymphadenopathy: 1981 update. Laryngoscope. 1981;91:1259–1266. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson MM, Underwood MJ, Sayers RD, Dookeran KA, Bell PRF. Peripheral tuberculous lymphadenopathy: a review of 67 cases. Br J Surg. 1992;79:763–764. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jha BC, et al. Cervical tuberculosis lymphadenopathy: changing clinical pattern and concepts in management. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:185–187. doi: 10.1136/pmj.77.905.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iqbal M, et al. Frequency of tuberculosis in cervical lyphedenopathy. J Surg Pak. 2010;15(2):107–109. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dandapat MC, Mishra BM, Dash SP, Kar PK. Peripheral lymph node tuberculosis: a review of 80 cases. Br J Surg. 1990;77:911–912. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800770823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Subrahmanyam M. Role of surgery and chemotherapy for peripheral lymph node tuberculosis. Br J Surg. 1993;8:1547–1548. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800801218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jawahar MS, Sivasubramaniam S, Vijayan VK, Ramakrishnan CV, Paramasivan CN, Selvakumar V, et al. Short-course chemotherapy for tuberculous lymphadenitis in children. BMJ. 1990;301:359–362. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6748.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen YM, Lee PY, Su WJ, Perng RP. Lymph node tuberculosis: 7-year experience in Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan. Tuber Lung Dis. 1992;73:368–371. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(92)90042-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fain O, Lortholary O, Djouab M, Amoura I, Bainet P, Beaudreuil J, et al. Lymph node tuberculosis in the suburbs of Paris: 59 cases in adults not infected by the human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999;3:162–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egeli E, et al. Epiglottic tuberculosis in a patient treated with steroid for addison’s disease. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2003;20:119–125. doi: 10.1620/tjem.201.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rout MR, Moharana PR. Tuberculosis of larynx: a case report. Indian J Tuberc. 2012;59:231–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramam M. Cutaneous tuberculosis. In: Sharma SK, Mohan A, editors. Tuberculosis. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2001. pp. 261–271. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mammen A, Thambiah AS. Tuberculosis of the skin. Indian J Dermatol Venereol. 1973;39:153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandhi RK, Bedi TR, Kanwar AJ, Bhutani LK. Cutaneous tuberculosis: a clinical and investigative study. Indian J Dermatol. 1977;22:99–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramesh V, Misra RS, Jain RK. Secondary tuberculosis of the skin, clinical features and problems in laboratory diagnosis. Int J Dermatol. 1986;26:578–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1987.tb02309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar B, Muralidhar S. Cutaneous tuberculosis: a twenty-year prospective study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999;3:494–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dublin LI (2015) Vital statistics. Am J Public Health. http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.17.3.280. Accessed 17 Sept 2015