Abstract

As a widely known hormone in animals, melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) has been more and more popular research topic in various aspects of plants. To summarize the these recent advances, this review focuses on the regulatory effects of melatonin in plant response to multiple abiotic stresses including salt, drought, cold, heat and oxidative stresses and biotic stress such as pathogen infection. We highlight the changes of endogenous melatonin levels under stress conditions, and the extensive metabolome, transcriptome, and proteome reprogramming by exogenous melatonin application. Moreover, melatonin-mediated stress signaling and underlying mechanism in plants are extensively discussed. Much more is needed to further study in detail the mechanisms of melatonin-mediated stress signaling in plants.

Keywords: melatonin, stress signaling, abiotic stress, biotic stress, mechanism

Introduction

N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine (melatonin) was first identified in the pineal gland of cow (Lerner et al., 1958, 1959). Later on melatonin was also discovered in plants (Dubbels et al., 1995; Hattori et al., 1995). Thereafter, melatonin has been identified in almost all plant species, although with different concentrations, including model plants (Arabidopsis, rice, tobacco), fruits (banana, cucumber, apple, beestrawberry), and so on (Arnao and Hernández-Ruiz, 2014, 2015; Reiter et al., 2001, 2014, 2015; Van Tassel et al., 2001; Simopoulos et al., 2005; Tan et al., 2007, 2012, 2014; Shi and Chan, 2014; Shi et al., 2015b,d,e,a,c,f). In the meantime, melatonin biosynthetic and metabolic pathways in plants have been revealed (Kang et al., 2010; Tan et al., 2012, 2014; Arnao and Hernández-Ruiz, 2014, 2015; Wang L. et al., 2014; Wang P. et al., 2014; Zuo et al., 2014; Reiter et al., 2015; Hardeland, 2016). Melatonin biosynthesis begins from tryptophan through four sequential enzyme reactions, involving tryptophan decarboxylase (TDC), arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AANAT)/serotonin N-acetyltransferase (SNAT), tryptamine 5-hydroxylase (T5H), N-aceylserotonin methyltransferase (ASMT)/hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase (HIOMT) (Tan et al., 2016; Wei et al., 2016). Thereafter, melatonin is converted to 2-hydroxymelatonin by melatonin 2-hydroxylase (M2H) (Byeon et al., 2015).

Based on previous studies using exogenous melatonin treatment or transgenic plants with higher or lower melatonin levels, some more general comprehension has been achieved as to the involvement of the compound in seed germination, root development, fruit ripening, senescence, yield, circadian rhythm, stress responses (Kolář and Macháčkova, 2005; Posmyk et al., 2008, 2009a,b; Li et al., 2012, 2015; Wang et al., 2012, 2013, 2015; Park et al., 2013; Yin et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2013; Bajwa et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2014, 2015; Zhang H. J. et al., 2014; Zhang N. et al., 2014; Liang et al., 2015; Byeon and Back, 2016). Considering the new advances in recent 5 years (Tan et al., 2012, 2014, 2015; Lee et al., 2014, 2015; Kaur et al., 2015; Reiter et al., 2015), we focus on the regulatory effects of melatonin in plant responses to multiple abiotic stress factors and plant–pathogen interactions (Table 1).

Table 1.

The functions of melatonin in plant stress responses.

| Plant species | Stress responses | Melatonin treatment or transgenic plants | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis | Cold stress | Melatonin treatment | Bajwa et al., 2014; Shi and Chan, 2014 |

| Arabidopsis | Disease resistance against Pseudomonas syringe pv. tomato | Melatonin treatment and transgenic plants |

Lee et al., 2014, 2015; Lee and Back, 2016; Qian et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2015a,c, 2016; Zhao et al., 2015a |

| Arabidopsis | Leaf senescence | Melatonin treatment | Shi et al., 2015d |

| Arabidopsis | Thermotolerance | Melatonin treatment | Shi et al., 2015e |

| Arabidopsis | Salt and drought stresses | Melatonin treatment | Shi et al., 2015c |

| Arabidopsis | Oxidative stress | Melatonin treatment | Weeda et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015 |

| Bermudagrass | Salt, drought and cold stresses | Melatonin treatment | Shi et al., 2015b |

| Bermudagrass | Oxidative stress | Melatonin treatment | Shi et al., 2015f |

| Nicotiana benthamiana | Disease resistance against Pseudomonas syringe pv. Tomato | Melatonin treatment | Lee et al., 2014 |

| Lupinus albus | Disease resistance to fungal infection (Penicillium spp.) | Melatonin treatment | Arnao and Hernández-Ruiz, 2015 |

| Rice | Salt and cold stresses | Transgenic plants | Kang et al., 2010; Byeon and Back, 2016 |

| Rice | Herbicide-induced oxidative stress | Transgenic plants | Park et al., 2013 |

| Rice | Cadmium stress | Transgenic plants | Byeon et al., 2015 |

| Rice | Leaf senescence and salt stress | Melatonin treatment | Liang et al., 2015 |

| Malus | Disease resistance to Marssonina apple blotch | Melatonin treatment | Yin et al., 2013 |

| Malus | Salt stress | Melatonin treatment | Li et al., 2012 |

| Malus | Drought stress | Melatonin treatment | Li et al., 2015 |

| Malus | Senescence | Melatonin treatment | Wang et al., 2012, 2013; Wang P. et al., 2014 |

| Cucumber | Chilling stress | Melatonin treatment | Posmyk et al., 2009a |

| Cucumber | Salt stress | Melatonin treatment | Zhang H. J. et al., 2014 |

| Cucumber | Drought stress | Melatonin treatment | Zhang N. et al., 2014 |

| Red cabbage | Copper ion | Melatonin treatment | Posmyk et al., 2008, 2009b |

| Tomato | Drought stress | Transgenic plants | Wang L. et al., 2014 |

Melatonin-Mediated Stress Responses

Secondary messengers including calcium and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) play essential roles in plant stress responses by linking upstream receptors and activating downstream signal transduction (Shi et al., 2015b,d,e,a,c,f; Zhang et al., 2015). It has been shown that nearly all stresses including salt, drought, cold, heat, zinc sulfate, H2O2, anaerobic, pH, pathogen, and senescence can cause a rapid and massive up-regulation of melatonin production in various plants (Tan et al., 2012, 2014; Reiter et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2015b,d,e,a,c,f), indicating the possible role of melatonin as an important messenger in plant stress responses.

Most of previous studies focused on the effect of melatonin on reactive oxygen species (ROS) metabolism, as well as the alleviation of stress-induced ROS production and the activation of antioxidants in melatonin-conferred stress resistance in plants (Zhang et al., 2015). In recent years, more and more studies have extended our understanding on the molecular mechanisms of melatonin-mediated stress responses in plants. Based on previous studies, plant transcription factors play important roles in plant stress responses, by directly regulating the transcription of stress-responsive genes and through acting in cross-talk between multiple signaling pathways (Reiter et al., 2014, 2015; Shi et al., 2015b,d,e,a,c,f). In Arabidopsis, we have found that four transcription factors including Arabidopsis thaliana Zinc Finger protein 6 (ZAT6) (Shi and Chan, 2014), Auxin Resistant 3 (AXR3)/Indole-3-Acetic Acid inducible 17 (IAA17) (Shi et al., 2015d), class A1 Heat Shock Factors (HSFA1s) (Shi et al., 2015e), and C-repeat-Binding Factors (CBFs)/Drought Response Element Binding 1 factors (DREB1s) (Shi et al., 2015c), are involved in melatonin-mediated signaling. Briefly, AtZAT6-activated CBF pathway is essential for melatonin-mediated freezing stress response (Shi and Chan, 2014); AtIAA17-activated senescence-related Senescence 4 (SEN4) and Senescence-Associated Gene 12 (SAG12) transcripts may contribute to the process of natural leaf senescence (Shi et al., 2015d); HSFA1s-activated transcripts of HSFA2, Heat-Stress-Associated 32 (HSA32), Heat Shock Protein 90 (HSP90), and HSP101 may contribute to melatonin-mediated thermotolerance (Shi et al., 2015e); AtCBFs-mediated signaling pathway and sugar accumulation may partially be involved in melatonin-mediated stress response (Shi et al., 2015c). Moreover, the diurnal changes of AtCBF/DREB1s expression may be regulated by the corresponding change of endogenous melatonin level and be involved in diurnal cycle of plant immunity (Shi et al., 2016). Thus, these transcription factors may play important roles in melatonin-mediated stress responses in plants.

Salicylic acid (SA) and NO are required small molecules for plant disease resistance, and SA-deficient plants (NahG overexpressing plants) and NO deficient mutants (noa1 and nia1nia2) show increased sensitivity to bacterial pathogen. Moreover, both of SA and NO confer enhanced disease resistance against bacterial pathogen in Arabidopsis, and the cooperation between them plays important roles in plant innate immunity (Shi et al., 2012). Recently, we also found that melatonin treatment increases the accumulation of sugars and glycerol, and the elevated sugars and glycerol thereafter increase the endogenous NO level, which confers an enhanced innate immunity against bacterial pathogens via a SA and NO-dependent pathway in Arabidopsis (Qian et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2015a,f). Consistently, Yin et al. (2013) showed that melatonin improves Malus resistance to Marssonina apple blotch, and Lee et al. (2014, 2015) found that melatonin confers disease resistance against pathogen attack in Arabidopsis and tobacco, which may be related with endogenous SA level. Zhao et al. (2015a) found that exogenous melatonin regulates carbohydrate metabolism, increases cell wall invertase (CWI), increases production of sucrose, glucose, fructose, cellulose, xylose and galactose, and cellose deposition during pathogen infection. They also found that melatonin-mediated sugar metabolism, especially its metabolites exert significant promotional and inhibitory effects, for instance on the growth of maize seedling, as was demonstrated by treatment with different doses of exogenous melatonin (Zhao et al., 2015b). Together with previous studies suggesting that sugars are functional, well compatible solutes for osmotic adaptation in response to abiotic stress, being also involved in the protection against bacterial pathogens (Thibaud et al., 2004; Shi et al., 2015a,f; Tsutsui et al., 2015), the above studies highlight the important roles of sugar metabolism in complex plant stress responses. Recently, Lee and Back (2016) found that the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling through MAPK kinase (MKK) 4/5/7/9-MPK3/6 cascades are also required for melatonin-mediated innate immunity in plants.

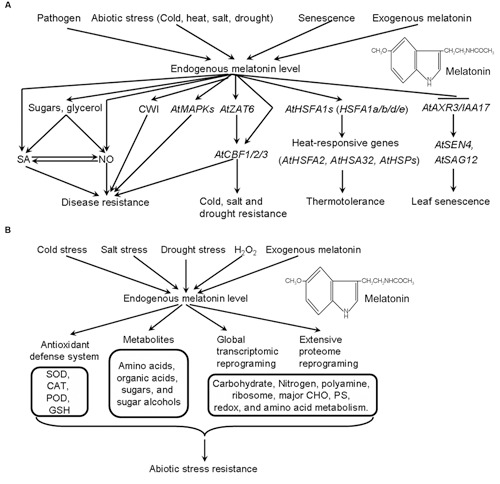

Based on these results, a hypothetical model explaining melatonin-mediated signaling in Arabidopsis is proposed (Figure 1A). Under various stress conditions, endogenous melatonin levels are quickly and significantly increased. As a consequence, the induction of melatonin increases the transcripts of some stress-related transcription factors (AtZAT6, AtCBFs, AtHSFA1s, and AtAXR3/IAA17) and the underlying down-stream genes, activates MAPK signaling, CWI and vacuolar invertase (VI), up-regulates carbohydrate metabolism especially the sugars. These induced affects in turn result in improved stress resistance in Arabidopsis.

FIGURE 1.

Hypothetical model explaining melatonin-mediated stress responses in Arabidopsis(A) and bermudagrass (B). (A) Under various stress conditions, endogenous melatonin levels are quickly and significantly increased. Thereafter the induction of melatonin increases the transcripts of some stress-related transcription factors (AtZAT6, AtCBFs, AtHSFA1s, and AtAXR3/IAA17), activates MAPK signaling, CWI, and vacuolar invertase (VI), up-regulates carbohydrate metabolism especially the sugars. These affections in turn result in improved stress resistance in Arabidopsis. (B) In response to abiotic stress, endogenous melatonin levels are significantly induced. The induction of melatonin increases the activities of antioxidant defense system, triggers the extensive reprogramming of primary metabolites, transcriptome and proteome, resulting protective stress responses in bermudagrass. CAT, catalase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; POD, peroxidase; GSH, glutathione; CHO, carbohydrate; PS, photosynthesis.

With the development of omics, several studies indicated that melatonin triggers extensive reprogramming of primary metabolites, transcriptome, and proteome in plants, further confirming its involvement in plant signal transduction. Weeda et al. (2014), Liang et al. (2015), and Shi et al. (2015b) identified 1308 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (566 up-regulated genes and 742 down-regulated genes), 3933 DEGs (2361 up-regulated genes and 1572 down-regulated genes) and 457 DEGs (191 up-regulated genes and 266 down-regulated genes) by exogenous melatonin treatment in Arabidopsis, bermudagrass and rice, respectively. Wang P. et al. (2014) and Shi et al. (2015f) identified 309 and 63 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) after exogenous melatonin treatment in apple and bermudagrass, respectively. MapMan and gene ontology (GO) analyses found that that several pathways were enhanced by melatonin treatment in bermudagrass, including nitrogen-metabolism, polyamine metabolism, major carbohydrate (CHO) metabolism, hormone metabolism, metal handling, photosynthesis (PS), redox status, and amino acid metabolism. Notablly, all these transcriptome and proteome studies identified a large number of transcription factors as DEGs or DEPs, the functional identification of these DEGs or DEPs may provide more valuable clues into melatonin-mediated signaling. Additionally, both Wang P. et al. (2014) and Shi et al. (2015f) indicated the possible role of melatonin in epigenetic modification in plants. Based on our previous studies (Shi et al., 2015b,f), we also propose a hypothetical model explaining melatonin-mediated stress responses in bermudagrass (Figure 1B). In response to abiotic stress, endogenous melatonin levels are significantly induced. The induction of melatonin activates antioxidant defense system, triggers the extensive reprogramming of primary metabolites, transcriptome, and proteome, resulting protective stress responses in bermudagrass. The “omics” approaches can give some clues about the effect of melatonin on plants, focusing on the extensive reprogramming of gene transcripts, protein expression and metabolites, as well as the relationship among them. This is just the beginning to reveal melatonin signaling in plants, many questions need to be investigated, including the crosstalk between melatonin and other phytohomones, the interaction between melatonin and primary or secondary metabolism.

Conclusion and Perspectives

The objective of this review is to update the research on melatonin-mediated stress signaling, and to encourage plant researches to dissect further molecular mechanism and signaling pathway. Although melatonin has continuously drawn the attentions of plant biologists and some advances have been made in recent years, melatonin-mediated complex signaling pathways are largely unknown. Since melatonin shares the common substrate (tryptophan) with IAA, the cross-talk between melatonin and auxin signaling pathways needs to be further investigated (Arnao and Hernández-Ruiz, 2014, 2015). Moreover, unlike for animals (Jackers et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2014), no specific melatonin-associated phenotype and no melatonin receptor have been characterized in plants. Thus, these open questions still prevent a full understanding of melatonin signaling in plants (Reiter et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015). Therefore, the identification of melatonin receptor or sensor and the establishment of molecular link between melatonin sensing and the regulators for plant stress responses will be an important next step.

Moreover, several fundamental issues need to be resolved. How is endogenous melatonin production regulated? How to perceive and transfer melatonin signaling in plant cells? What are the major or limiting steps in melatonin signaling transduction in plants? Which genes are specifically regulated by melatonin and underlying signaling pathways? Together with the development of more new techniques, further studies will shed more light on the global involvement of melatonin in plants and underlying signaling pathway.

Author Contributions

HS initiated this project, wrote and revised the manuscript, KC, and YW wrote the manuscript, CH provided suggestions and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript and the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to all colleagues whose original works could not be cited in the manuscript because of space limitations. We also thank Prof. Zhulong Chan, Russel J. Reiter, and Dun-Xian Tan for their help and encouragement in the related research.

Footnotes

Funding. This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.31570249), the scientific research foundation of higher education in Hainan province (the education curriculum reform program, title: Research on the overall optimization of the curriculum system and teaching content of Hainan province excellent course-gene engineering, No.Hnjg2016-10), a central financial support to enhance the comprehensive strength of the central and western colleges and universities, the startup funding of Hainan University and the scientific research foundation of Hainan University (No.kyqd1531) and the education curriculum reform program of Hainan University (No.hdjy1601) to Haitao Shi.

References

- Arnao M. B., Hernández-Ruiz J. (2014). Melatonin: plant growth regulator and/or biostimulator during stress? Trends Plant Sci. 19 789–797. 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnao M. B., Hernández-Ruiz J. (2015). Function of melatonin in plants: a review. J. Pineal Res. 59 133–150. 10.101111/jpi.12253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajwa V. S., Shukla M. R., Sherif S. M., Murch S. J., Saxena P. K. (2014). Role of melatonin in alleviating cold stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Pineal Res. 56 238–245. 10.1111/jpi.12115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byeon Y., Back K. (2016). Low melatonin production by suppression of either serotonin N-acetyltransferase or N-acetylserotonin methyltransferase causes seedling growth retardation with yield penalty, abiotic stress susceptibility, and enhanced coleoptile growth in rice under anoxic conditions. J. Pineal Res. 60 348–359. 10.1111/jpi.12317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byeon Y., Lee H. Y., Hwang O. J., Lee H. J., Lee K., Back K. (2015). Coordinated regulation of melatonin synthesis and degradation genes in rice leaves in response to cadmium treatment. J. Pineal Res. 58 470–478. 10.1111/jpi.12232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubbels R., Reiter R. J., Klenke E., Goebel A., Schnakenberg E., Ehlers C., et al. (1995). Melatonin in edible plants identified by radioimmunoassay and by high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Pineal Res. 18 28–31. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.1995.tb00136.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeland R. (2016). Melatonin in plants-diversity of levels and multiplicity of functions. Front. Plant Sci. 7:198 10.3389/fpls.2016.00198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori A., Migitaka H., Iigo M., Itoh M., Yamamoto K., Ohtani-Kaneko R., et al. (1995). Identification of melatonin in plants and its effects on plasma melatonin levels and binding to melatonin receptors in vertebrates. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Inter. 35 627–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackers R., Maurice P., Boutin J. A., Delagrange P. (2008). Melatonin receptors, heterodimerization, signal transduction and binding sites: what’s new? Br. J. Pharmacol. 154 1182–1195. 10.1038/bjp.2008.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang K., Lee K., Park S., Kim Y. S., Back K. (2010). Enhanced production of melatonin by ectopic overexpression of human serotonin N-acetyltransferase plays a role in cold resistance in transgenic rice seedlings. J. Pineal Res. 49 176–182. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00783.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur H., Mukherjee S., Baluska F., Bhatla S. C. (2015). Regulatory roles of serotonin and melatonin in abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 10:e1049788 10.1080/15592324.2015.1049788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolář J., Macháčkova I. (2005). Melatonin in higher plants: occurrence and possible functions. J. Pineal Res. 39 333–341. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00276.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. Y., Back K. (2016). Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways are required for melatonin-mediated defense responses in plants. J. Pineal Res. 60 327–335. 10.1111/jpi.12314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. Y., Byeon Y., Back K. (2014). Melatonin as a signal molecule triggering defense responses against pathogen attack in Arabidopsis and tobacco. J. Pineal Res. 57 262–268. 10.1111/jpi.12165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. Y., Byeon Y., Tan D. X., Reiter R. J., Back K. (2015). Arabidopsis serotonin N-acetyltransferase knockout mutant plants exhibit decreasedmelatonin and salicylic acid levels resulting in susceptibility to an avirulent pathogen. J. Pineal Res. 58 291–299. 10.1111/jpi.12214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner A. B., Case J. D., Heinzelman R. V. Structure of melatonin. (1959). Structure of melatonin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 81 6084–6085. 10.1021/ja01531a060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner A. B., Case J. D., Takahashi Y., Lee Y., Mori W. (1958). Isolation of melatonin, the pineal gland factor that lightening melanocytes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 81 2587 10.1021/ja01543a060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Tan D. X., Liang D., Chang C., Jia D., Ma F. (2015). Melatonin mediates the regulation of ABA metabolism, free-radical scavenging, and stomatal behaviour in two Malus species under drought stress. J. Exp. Bot. 66 669–680. 10.1093/jxb/eru476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Wang P., Wei Z., Liang D., Liu C., Yin L., et al. (2012). The mitigation effects of exogenous melatonin on salinity-induced stress in Malus hupehensis. J. Pineal Res. 53 298–306. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2012.00999.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C., Zheng G., Li W., Wang Y., Hu B., Wang H., et al. (2015). Melatonin delays leaf senescence and enhances salt stress tolerance in rice. J. Pineal Res. 59 91–101. 10.1111/jpi.12243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Lee D. E., Jang H., Byeon Y., Kim Y. S., Back K. (2013). Melatonin-rich transgenic rice plants exhibit resistance to herbicide-induced oxidative stress. J. Pineal Res. 54 258–263. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2012.01029.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posmyk M. M., Bałabusta M., Wieczorek M., Sliwinska E., Janas K. M. (2009a). Melatonin applied to cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) seeds improves germination during chilling stress. J. Pineal Res. 46 214–223. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00652.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posmyk M. M., Janas K. M., Kontek R. (2009b). Red cabbage anthocyanin extract alleviates copper-induced cytological disturbances in plant meristematic tissue and human lymphocytes. Biometals 22 479–490. 10.1007/s10534-009-9205-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posmyk M. M., Kuran H., Marciniak K., Janas K. M. (2008). Presowing seed treatment with melatonin protects red cabbage seedlings against toxic copper ion concentrations. J. Pineal Res. 45 24–31. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00552.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y., Tan D. X., Reiter R. J., Shi H. (2015). Comparative metabolomic analysis highlights the involvement of sugars and glycerol in melatonin-mediated innate immunity against bacterial pathogen in Arabidopsis. Sci. Rep. 5:15815 10.1038/srep15815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter R. J., Tan D. X., Burkhardt S., Manchester L. C. (2001). Melatonin in plants. Nutr. Rev. 59 286–290. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2001.tb07018.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter R. J., Tan D. X., Galano A. (2014). Melatonin: exceeding expectations. Physiology (Bethesda) 29 325–333. 10.1152/physiol.00011.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter R. J., Tan D. X., Zhou Z., Cruz M. H., Fuentes-Broto L., Galano A. (2015). Phytomelatonin: assisting plants to survive and thrive. Molecules 20 7396–7437. 10.3390/molecules20047396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Chan Z. (2014). The cysteine2/histidine2-type transcription factor ZINC FINGER OF ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA 6-activated C-REPEAT-BINDING FACTOR pathway is essential formelatonin-mediated freezing stress resistance in Arabidopsis. J. Pineal Res. 57 185–191. 10.1111/jpi.12155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Chen Y., Tan D. X., Reiter R. J., Chan Z., He C. (2015a). Melatonin induces nitric oxide and the potential mechanisms relate to innate immunity against bacterial pathogen infection in Arabidopsis. J. Pineal Res. 59 102–108. 10.1111/jpi.12244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Jiang C., Ye T., Tan D. X., Reiter R. J., Zhang H., et al. (2015b). Comparative physiological, metabolomic, and transcriptomic analyses reveal mechanisms of improved abiotic stress resistance in bermudagrass [Cynodon dactylon (L). Pers.] by exogenous melatonin. J. Exp. Bot. 66 681–694. 10.1093/jxb/eru373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Qian Y., Tan D. X., Reiter R. J., He C. (2015c). Melatonin induces the transcripts of CBF/DREBs and their involvement in abiotic and biotic stresses in Arabidopsis. J. Pineal Res. 59 334–342. 10.1111/jpi.12262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Reiter R. J., Tan D. X., Chan Z. (2015d). INDOLE-3-ACETIC ACID INDUCIBLE 17 positively modulates natural leaf senescence through melatonin-mediated pathway in Arabidopsis. J. Pineal Res. 58 26–33. 10.1111/jpi.12188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Tan D. X., Reiter R. J., Ye T., Yang F., Chan Z. (2015e). Melatonin induces class A1 heat-shock factors (HSFA1s) and their possible involvement of thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. J. Pineal Res. 58 335–342. 10.1111/jpi.12219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Wang X., Tan D. X., Reiter R. J., Chan Z. (2015f). Comparative physiological and proteomic analyses reveal the actions of melatonin in the reduction of oxidative stress in Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon (L). Pers.). J. Pineal Res. 59 120–131. 10.1111/jpi.12246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Wei Y., He C. (2016). Melatonin-induced CBF/DREB1s are essential for diurnal change of disease resistance and CCA1 expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 100 150–155. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H. T., Li R. J., Cai W., Liu W., Wang C. L., Lu Y. T. (2012). Increasing nitric oxide content in Arabidopsis thaliana by expressing rat neuronal nitric oxide synthase resulted in enhanced stress tolerance. Plant Cell Physiol. 53 344–357. 10.1093/pcp/pcr181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simopoulos A. P., Tan D. X., Manchester L. C., Reiter R. J. (2005). Purslane: a plant source of omega-3 fatty acids and melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 39 331–332. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00269.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan D. X., Hardeland R., Back K., Manchester L. C., Alatorre-Jimenez M. A., Reiter R. J. (2016). On the significance of an alternate pathway of melatonin synthesis via 5-methoxytryptamine: comparisons across species. J. Pineal Res. 61 27–40. 10.1111/jpi.12336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan D. X., Hardeland R., Manchester L. C., Korkmaz A., Ma S., Rosales-Corral S., et al. (2012). Functional roles of melatonin in plants, and perspectives in nutritional and agricultural science. J. Exp. Bot. 63 577–597. 10.1093/jxb/err256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan D. X., Manchester L. C., Esteban-Zubero E., Zhou Z., Reiter R. J. (2015). Melatonin as a potent and inducible encogenous antioxidant: synthesis and metabolism. Molecules 20 18886–18906. 10.3390/molecules201018886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan D. X., Manchester L. C., Helton P., Reiter R. J. (2007). Phytoremediative capacity of plants enriched with melatonin. Plant Signal. Behav. 2 514–516. 10.4161/psb.2.6.4639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan D. X., Zheng X., Kong J., Manchester L. C., Hardeland R., Kim S. J., et al. (2014). Fundamental issues related to the origin of melatonin and melatonin isomers during evolution: relation to their biological functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15 15858–15890. 10.3390/ijms150915858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibaud M. C., Gineste S., Nussaume L., Robaqlia C. (2004). Sucrose increases pathogenesis-related PR-2 gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana through an SA-dependent but NPR1-independent signaling pathway. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 42 81–88. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2003.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui T., Nakano A., Ueda T. (2015). The plant-specific RAB5 GTPase ARA6 is required for starch and sugar homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 56 1073–1083. 10.1093/pcp/pcv029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tassel D. L., Roberts N., Lewy A., O’Neill S. D. (2001). Melatonin in plant organs. J. Pineal Res. 31 8–15. 10.1034/j.1600-079X.2001.310102.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Zhao Y., Reiter R. J., He C., Liu G., Lei Q., et al. (2014). Changes in melatonin levels in transgenic ’Micro-Tom’ tomato overexpressing ovine AANAT and ovine HIOMT genes. J. Pineal Res. 56 134–142. 10.1111/jpi.12105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Sun X., Chang C., Feng F., Liang D., Cheng L., et al. (2013). Delay in leaf senescence of Malus hupehensis by long-term melatonin application is associated with its regulation of metabolic status and protein degradation. J. Pineal Res. 55 424–434. 10.1111/jpi.12091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Sun X., Wang N., Tan D. X., Ma F. (2015). Melatonin enhances the occurrence of autophagy induced by oxidative stress in Arabidopsis seedlings. J. Pineal Res. 58 479–489. 10.1111/jpi.12233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Sun X., Xie Y., Li M., Chen W., Zhang S., et al. (2014). Melatonin regulates proteomic changes during leaf senescence in Malus hupehensis. J. Pineal Res. 57 291–307. 10.1111/jpi.12169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Yin L., Liang D., Li C., Ma F., Yue Z. (2012). Delayed senescence of apple leaves by exogenous melatonin treatment: toward regulating the ascorbate-glutathione cycle. J. Pineal Res. 53 11–20. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00966.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeda S., Zhang N., Zhao X., Ndip G., Guo Y., Buck G. A., et al. (2014). Arabidopsis transcriptome analysis reveals key roles of melatonin in plant defense systems. PLoS ONE 9:e93462 10.1371/journal.pone.0093462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Zeng H., Hu W., Chen L., He C., Shi H. (2016). Comparative transcriptional profiling of melatonin synthesis and catabolic genes indicates the possible role of melatonin in developmental and stress responses in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 7:676 10.3389/fpls.2016.00676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L., Wang P., Li M., Ke X., Li C., Liang D., et al. (2013). Exogenous melatonin improves Malus resistance to Marssonina apple blotch. J. Pineal Res. 54 426–434. 10.1111/jpi.12038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L., Sun Y., Cheng L., Jin Z., Yang Y., Zhai M., et al. (2014). Melatonin receptor-mediated protection against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: role of SIRT1. J. Pineal Res. 57 228–238. 10.1111/jpi.12161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. J., Zhang N., Yang R. C., Wang L., Sun Q. Q., Li D. B., et al. (2014). Melatonin promotes seed germination under high salinity by regulating antioxidant systems, ABA and GA interaction in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). J. Pineal Res. 57 269–279. 10.1111/jpi.12167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Zhang H. J., Zhao B., Sun Q. Q., Cao Y. Y., Li R., et al. (2014). The RNA-seq approach to discriminate gene expression profiles in response tomelatonin on cucumber lateral root formation. J. Pineal Res. 56 39–50. 10.1111/jpi.12095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Sun Q., Zhang H., Cao Y., Weeda S., Ren S., et al. (2015). Roles of melatonin in abiotic stress resistance in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 66 647–656. 10.1093/jxb/eru336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Zhao B., Zhang H. J., Weeda S., Yang C., Yang Z. C., et al. (2013). Melatonin promotes water-stress tolerance, lateral root formation, and seed germination in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). J. Pineal Res. 54 15–23. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2012.01015.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H., Xu L., Su T., Jiang Y., Hu L., Ma F. (2015a). Melatonin regulates carbohydrate metabolism and defenses against Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 infection in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Pineal Res. 59 109–119. 10.1111/jpi.12245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H., Su T., Hu L., Wei H., Jiang Y., Xu L., et al. (2015b). Unveiling the mechanism of melatonin impacts on maize seedling growth: sugar metablism as a case. J. Pineal Res. 59 255–266. 10.1111/jpi.12258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Tan D. X., Lei Q., Chen H., Wang L., Li Q. T., et al. (2013). Melatonin and its potential biological functions in the fruits of sweet cherry. J. Pineal Res. 55 79–88. 10.1111/jpi.12044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo B., Zheng X., He P., Wang L., Lei Q., Feng C., et al. (2014). Overexpression of MzASMT improves melatonin production and enhances drought tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana plants. J. Pineal Res. 57 408–417. 10.1111/jpi.12180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]