Abstract

Background

Recent studies using simulated functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data show that independent vector analysis (IVA) is a superior solution for capturing spatial subject variability when compared with the widely used group independent component analysis (GICA). Retaining such variability is of fundamental importance for identifying spatially localized group differences in intrinsic brain networks.

New Methods

Few studies on capturing subject variability and order selection have evaluated real fMRI data. Comparison of multivariate components generated by multiple algorithms is not straightforward. The main difficulties are finding concise methods to extract meaningful features and comparing multiple components despite lack of a ground truth. In this paper, we present a graph-theoretic approach to effectively compare the ability of multiple multivariate algorithms to capture subject variability for real fMRI data for effective group comparisons.

Results

Discriminating trends in features calculated from IVA- and GICA-generated components show that IVA better preserves the qualities of centrality and small worldness in fMRI data. IVA also produced components with more activated voxels leading to larger area under the curve (AUC) values. Comparison with Existing Method IVA is compared with widely used GICA for the purpose of group discrimination in terms of graph-theoretic features. In addition, masks are applied for motor related components generated by both algorithms.

Conclusions

Results show IVA better captures subject variability producing more activated voxels and generating components with less mutual information in the spatial domain than Group ICA. IVA-generated components result in smaller p-values and clearer trends in graph-theoretic features.

Index Terms: IVA, GICA, fMRI, stroke patient, graph-theoretic analysis, order selection

1. INTRODUCTION

Independent component analysis (ICA) is a popular and widely used data-driven technique that achieves blind source separation (BSS) on an observed dataset based on the assumption that it is made from linear mixtures of statistically independent sources. Applying spatial ICA to fMRI data results in maximally independent spatial components with associated time courses. In this study, we use spatial ICA which is the most common form of ICA applied to fMRI analysis. Often, the goal of medical research is to study group differences, e.g., control vs patient groups, which requires multiple datasets. The application of ICA to multiple datasets, known as joint blind source separation (JBSS), is not straightforward. The easiest approach has been to perform ICA on each dataset separately but this does not take advantage of the statistical dependence across datasets and also requires solving the complex problem of component matching due to the permutation ambiguity for each estimated set of sources. GICA [1] has been a popular approach for the analysis of fMRI data from multiple subjects. An advantage of group ICA is that it performs a single ICA for all datasets and provides the same component ordering for each dataset which facilitates subject comparison. In order to perform a single ICA, each dataset is temporally concatenated followed by a common principal component analysis step that defines a single subspace on which ICA is performed. Single subject maps and time courses can then be back-reconstructed using various approaches [2]. GICA has been shown to capture considerable inter-subject variability [3], however, for the forward estimation step, it assumes a common subspace for all subjects which might limit the ability to capture the individual subject variability in spatial maps.

IVA is a recent extension of ICA to multiple datasets. Recent studies using simulated fMRI data [4, 5, 6] have shown that IVA is a superior solution for capturing spatial variability when compared with the popular GICA. At high levels of subject variability in spatial maps, [4] found that IVA continues to perform well whereas GICA performance declines. In a study using fMRI data from subjects with schizophrenia, [7] found that IVA better captured differences in variance in the spatial maps among multiple groups.

IVA does not limit the solution space by using a common subspace like group ICA but rather estimates a demixing matrix for each dataset simultaneously, thereby allowing individual subject variability to be better captured which is of central importance for group comparison studies. IVA also removes the need for component matching by capturing spatial statistical dependence among corresponding subject components. IVA takes advantage of any dependent sources across datasets by maximizing their mutual information.

In this paper, we present a multivariate graph-theoretical framework that summarizes components in terms of features to effectively compare the performance of JBSS methods for capturing subject variability for group analysis of real fMRI data. In addition, we discuss the role that order selection plays in this analysis and we suggest the use of higher orders for the number of estimated components and IVA, which is especially important when data exhibits large subject variability.

2. METHODS

2.1. IVA and ICA

Both ICA and IVA assume that datasets are linear mixtures of N statistically independent sources. ICA achieves BSS on only a single dataset. IVA is a recent extension of ICA that exploits dependence across multiple datasets while achieving JBSS. IVA takes K datasets, each with N observations. Each dataset is represented as a random vector using superscript notation as k = 1, …, K. The IVA generative mixture model for x[k] is

| (1) |

where each A[k] is an N by N mixing matrix and is the random vector representing the original sources for the kth dataset. When K = 1, IVA is equivalent to ICA:

| (2) |

For K > 1, IVA simultaneously estimates a demixing matrix W[k] for each dataset

| (3) |

where y[k] is the random vector representation for the estimated sources for the kth dataset. When K = 1, the ICA solution is

| (4) |

The ICA cost to be minimized is

| (5) |

The cost function corresponds to minimizing the mutual information and entropy of the source estimates. The constant C is determined by the observed data x.

IVA exploits dependence across datasets allowing each source from a dataset to have statistical dependence with one source from each other dataset. Sources across datasets are placed in a vector called a source component vector (SCV) and the mutual information within each SCV is maximized as part of the IVA cost function. For N sources in each dataset, N estimated SCVs are formed yn = [yn[1], yn[2], …, yn[K]]T, n = 1, …, N. Each SCV has K sources, one per dataset. For multiple datasets the IVA cost function can be written as shown in [8],

| (6) |

where ℐ is mutual information and C is a constant determined by the observed datasets x[k], k = 1, …, K. If the datasets do not have dependence then ℐ(yn) drops out of the cost function which then simplifies to the sum of (5) taken across each dataset. IVA is therefore equivalent to performing ICA on each dataset individually if there is no dependence across datasets to be exploited. If dependence exists then IVA effectively exploits it by maximizing the mutual information within each SCV which takes each dataset into account simultaneously. IVA also minimizes the entropy of the individual source estimates while minimizing the mutual information between each SCV taking higher order statistics into account. For the case K = 1, the IVA cost function reduces to the ICA cost function (5).

2.2. IVA and GICA for fMRI data

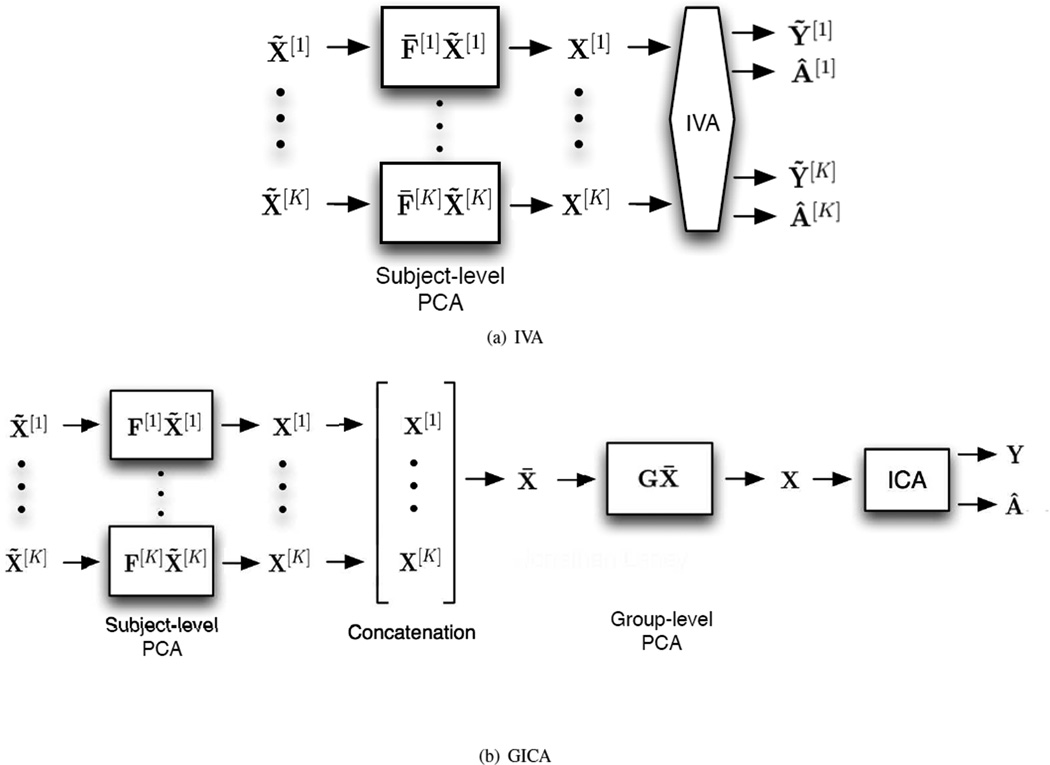

GICA is an extension of ICA to multiple datasets introduced for fMRI analysis [1]. GICA defines a single subspace for all subjects and performs BSS on the common subject subspace, these results are then reconstructed to get the corresponding JBSS solution for all datasets [2]. IVA is a more recent extension that performs JBSS across all datasets simultaneously. The two JBSS methods are displayed in Figure 2 and the corresponding back-reconstruction in Figure 3.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of multisubject fMRI data using (a) IVA; and (b) GICA. IVA alleviates the need to project multiple subjects to a common signal space and does not require back-reconstruction for spatial components.

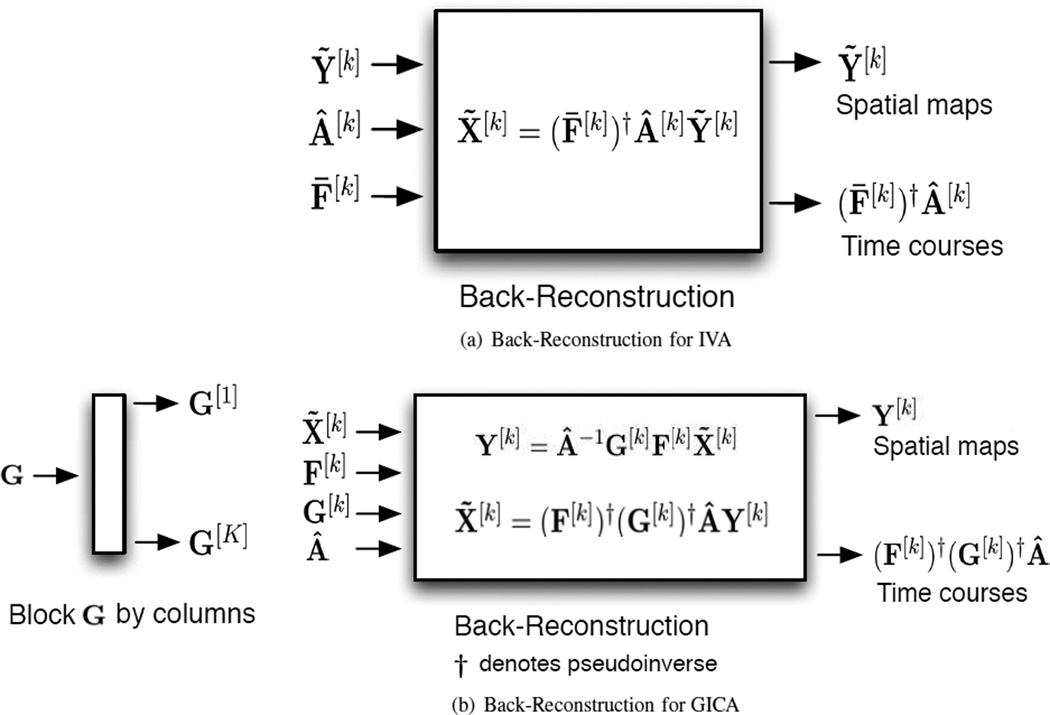

Fig. 3.

Back-reconstruction stages for (a) IVA and (b) GICA.

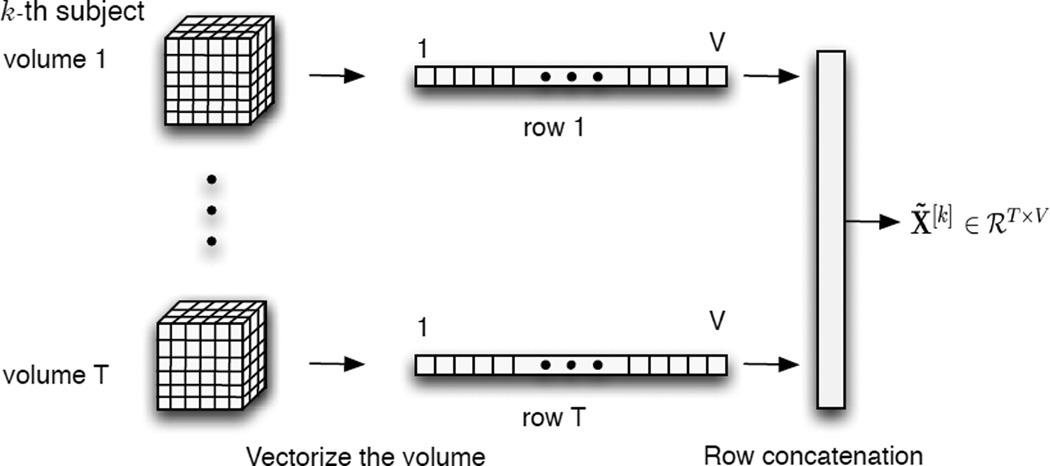

Starting with four dimensional fMRI data for the kth subject, which consists of T three dimensional brain volumes taken over time, this is reduced to a two dimensional matrix, as depicted in Figure 1. Each volume is flattened into a one by V vector, V is the number of voxels, then each vector becomes a row in the data matrix X̃[k] ∈ ℛT × V whose units are time by voxles.

Fig. 1.

Definition of X̃ through flattening of the 4 dimensional fMRI data.

For IVA and GICA, see Figures 2(a) and 2(b), respectively where for each, the K data matrices, X̃[k] k = 1, …, K, are first reduced in dimension by principal component analysis (PCA) on each dataset. PCA is an orthogonal transformation procedure that results in linearly uncorrelated principal components. The first principal component (PC) is selected in the direction of largest variance. Each subsequent PC is chosen in the direction of greatest variance orthogonal to all previous PCs. By selecting only the first N of T PCs, N < T, the dimensionality of a dataset can be reduced to a subspace that more concisely represents the signal space of the dataset. The transformation is seen as matrix multiplication on the left by a matrix containing row vectors that represent the directions that correspond the first N PCs.

For the IVA case, X[k] = F̄[k]X̃[k], F̄[k] ∈ ℛN × T, X[k] ∈ ℛN × V. The number of rows for each data matrix is reduced from T to N. This helps denoise the data retaining the signal space. IVA then estimates N components for all datasets X[k] k = 1, …, K simultaneously, resulting in N × K spatial components. The kth subject’s N spatial components are contained in Ỹ[k].

GICA, however, first reduces X̃[k] k = 1, …, K, in dimension by PCA down to T′. X[k] = F[k]X̃[k], F[k] ∈ ℛT′ × T, X[k] ∈ ℛT′ × V. GICA further assumes a common signal subsapce for X[k] k = 1, …, K. This common signal space is created by first temporally concatenating each X[k] to form a single matrix X̄ which is then reduced to X through PCA. X = GX̄, X ∈ ℛN × V, G ∈ ℛN × KT′, X̄ ∈ ℛKT′ × V. ICA is then performed on the common space X to produce group components Y. The assumption is that there exist common group spatial components, modeled as the average of the subject’s spatial maps, leading to an averaging effect on these group spatial maps [3, 9].

IVA then back-reconstructs the kth, k = 1, …, K, subject’s time courses using the estimated mixing matrix Â[K] and the pseudoinverse of the data reduction matrix (F̄[k])†. The subject’s time course is calculated as Ā[k] = (F̄[k])†Â[k], Â[k] ∈ ℛN × N. There is no back-reconstruction needed for the spatial maps for the IVA case because they are calculated directly by IVA; however, GICA needs to back-reconstruct both the spatial maps and the time courses for each subject. The group dimension-reduction matrix G is blocked by columns; G = [G[1] … G[K]], G[k] ∈ ℛN × T′. Each block corresponds to a single subject, i.e., dataset. The same group demixing matrix Â−1 is used to construct each subject’s spatial maps. The kth subject spatial maps Y[k] are then reconstructed. Y[k] = Â−1G[k]F[k]X̃[k]. The subject time courses Ā[k] are also reconstructed; Ā[k] = (F[k])†(G[k])†Â, where † denotes the pseudoinverse. IVA calculates the spatial maps directly for each subject allowing for subject spatial variability to be better captured during group fMRI analysis.

There can be multiple implementations of IVA, the implementation that we use to process the fMRI data is called the IVA-GL algorithm [8, 10]. This implementation takes full second order dependence among entries of an SCV into account by IVA-G which uses a Gaussian distribution for each entry within an SCV. The estimates of the demixing matrices are then used to initialize IVA-L that takes higher-order statistics into account by assuming a Laplacian distribution for each entry within an SCV. We processed the same fMRI data with the Infomax algorithm, implemented in GICA, assuming a Laplacian distribution for the independent components, which makes it a good match for comparison with IVA-GL. This algorithm will be referred to as Infomax-L.

2.3. Order Selection

Order selection is important due to the high dimensionality and high noise level in fMRI data, however, the problem of estimating the number of informative components is not straightforward due to noise and sample dependence in the spatial domain. For data obtained from subjects with stroke, high subject variability makes the order estimation more difficult. One approach, as in [11], has been to subsample to a set of independent and identically distributed data samples in order to take advantage of information-theoretic criteria that require this assumption. We use subsampling with a minimum description length (MDL) based estimator [11] to find the average estimated order over datasets. Research comparing ICA methods suggest that retaining more components at the subject PCA level is advantageous in order to improve time course and spatial map estimates, see e.g., [2, 12]. We generated components starting at order 20 and increasing in step sizes of 10 up to order 100. We found that higher orders, especially when subject datasets exhibit high variability, improve the estimation of spatial components. Order 80 generated components with more meaningful spatial maps and significant t-maps. At higher orders meaningful spatial components become fractured into separate component maps.

2.4. Validation

We validate our calculated group features by subsampling each group at one third the group size to form a subgroup. A third of the subjects are randomly chosen from the pre-group and the corresponding subjects are chosen from the post-group. Repeating this random sampling, we form twenty subgroups. The given feature is recalculated for both the pre- and post-subgroups. An unpaired two-sample t-test is performed to validate whether random subgroups show the difference found when considering the entire population. A similar approach to functional network connectivity (FNC) validation is used by [13], which is similar to a delete-m jack-knife method. FNC is computed by calculating the temporal dependence among components usually through covariance and is thus a measure of connectivity across components. Spatial FNC (sFNC) measures connectivity in terms of the dependence among spatial components calculated using mutual information.

2.5. Graph-Theoretical Analysis

Graph-theoretic (GT) analysis has been used to study FNC and sFNC for analysis of fMRI data, see e.g., [12, 14]. We show that GT analysis also provides an effective way to evaluate the performance of multiple multivariate algorithms in capturing subject variability. We investigate how capturing subject variability during JBSS leads to the preservation of each subject’s FNC and sFNC which highlights changes in GT features. We calculate GT features for each subject and average these feature values over all subjects to produce group features.

GT analysis simultaneously takes all meaningful components into account to form group features such as the clustering coefficient and node centrality. For each subject, an undirected graph is formed where each node corresponds to an estimated temporal or z-scored spatial component for the analysis of FNC and sFNC, respectively. For sFNC each edge is defined by the mutual information between nodes and for FNC edge values are defined by the correlation coefficient between nodes. Graph densities are formed by removing the edges that have values below a chosen threshold. When the threshold is low, the graph retains many connections and is comparable to a random network with an equal number of edges and nodes. As the threshold increases, graphs with different connection densities are formed resulting in trends in the graph-theoretic features.

The clustering coefficient is calculated as in [15]

| (7) |

A cluster exists if two neighbors of the nth node are connected. The number of edges connected to the nth node is Nn, therefore, Nn(Nn − 1)/2 is the maximum number of possible cluster and En represents the actual number clusters at the nth node. This clustering coefficient is then normalized by the corresponding coefficient from the comparable random graph with the same number of nodes and edges as the observed graph. These values are then averaged over subjects for each threshold. Two groups of data were formed from subjects with stroke, one group before and after a hand rehabilitation intervention, referred to as the pre- and post-group. We used random subject sampling on each group. The average clustering coefficient was calculated for each randomly selected subgroup and an unpaired two-sample t-test was performed across subgroups to find significant differences between the pre- and post-group. As noted in [16], the quality of small worldness in neural networks is more prominent in healthy subjects, which results in higher clustering coefficients. This is likely to be disrupted in stroke patients, leading to smaller clustering coefficients.

The centrality of a node is determined by its role in the shortest path between all pairwise nodes. The shortest path from one node to another is calculated by first converting edge values into distance values. The edge values are the mutual information values between nodes which represent the z-scored spatial components. These edge values are mapped to distance values between zero and one. Let ei and di represent the MI and distance values of the ith edge, respectively. The distance value for the ith edge is calculated as

| (8) |

The shortest path from node p to node q is the path that has the smallest sum of distances along the path. The centrality of the ith node is representative of the number of times that node i is found on the shortest path between all other pairwise nodes. High centrality suggests that the component is important in terms of efficiency of the brain’s functional network connectivity. The centrality for node i is calculated as in [17],

| (9) |

where Ep,i,q is the number of shortest paths between pairwise nodes that include node i and Ep,q is the number of shortest paths. Using binary weighted edges it is possible to have more than one shortest path but with distance edges there is always just one shortest path.

This work significantly extends work published at a conference [18]. The conference paper [18] briefly introduces graph-theory and shows a pair of t-maps for one independent component and two clustering coefficient plots. This paper extends our results laying out our graph-theoretic framework for the comparison of algorithm performance in capturing subject variability.

2.6. Performance Evaluation

The evaluation of an algorithm’s performance in producing components from real fMRI data is not straightforward. Graph-theoretical features generated for just one group over multiple algorithms does not lead to an informative method of comparison. Methods for comparing multiple algorithm component sets are developed here under a GT framework for multigroup studies. Using GT analysis we summarize multivariate components into features. These features provide a powerful way to highlight group differences. The comparison of group differences highlighted in the results of each algorithm thus provides a concise way of comparing algorithm performance.

2.6.1. Clustering Coefficient

The clustering coefficient shows group differences between the pre- and post-group. The functional networks of healthy subjects are found to have more clustering than found in random networks of the same number of nodes and edges. A shift toward random networks has been previously demonstrated in stroke and other brain pathologies, such as brain tumors [19], Alzheimer’s disease [20], and epilepsy [21]. The stroke patient groups show more clustering in key motor components after the rehabilitation, i.e., the post-group, allowing us to compare the differences found for multiple algorithms leading to inferences into the algorithms’ ability to capture these differences at the subject level. FNC validation was performed across random subgroups.

2.6.2. Centrality

Node centrality, calculated for spatial components, is an indicator of mutual information shared between separate spatial regions of the brain suggesting share of information in terms of functional network connectivity. The algorithms’ ability to highlight group differences in terms of component centrality is compared. Many networks activate even during rest; a change in centrality in key motor components during rest may be suggestive of functional changes in network connectivity which is of interest. Using sFNC validation, centrality was calculated across random subgroups.

2.6.3. Component Masks

Spatial components can be described in terms of corresponding Brodmann areas [22]. Masks fit to these Brodmann areas provide a way to quantify voxel activation in terms of false alarm and detection power. Region of convergence (ROC) curves are created across a range of voxel wise thresholds of spatial z-maps. This is validated by forming ROC curves for randomly selected subgroups. This is not the ROC in the traditional sense. The mask is not treated as a ground truth but rather the area under the curve (AUC) is considered as an indicator of how well spatial components fit a standard spatial area described by corresponding Brodmann areas. This serves as a comparison for corresponding components generated by multiple algorithms.

3. DATA

We collected 23 total sessions of fMRI data from 10 participants (subjects) with chronic (> 6 months) stroke using a 3 Tesla Philips scanner. Participants provided up to 3 sessions of resting state data. All participants lost motor functionality due to stroke and had moderate upper extremity paresis. All participants then underwent a 6 week unilateral rehabilitation intervention. We then collected 23 FMRI session datasets post intervention training, forming a pre-group and post-group. Each MRI session itself will be referred to as a subject, hence, there are 23 subjects in the pre- and post-group.

The SPM8 software package [23] was employed to perform fMRI pre-processing. Slice timing was performed with a shift relative to the acquisition time of the middle slice using sinc-interpolation. All images were spatially realigned to the 1st volume to correct for inter-scan movement. To remove movement-related variance the realigned images were processed using the unwarp SPM8 function. Given the observed variance (after realignment) and the realignment parameters, estimates of how deformations changed with subject movement were made, which subsequently were used to minimize movement-related variance. Data were then spatially normalized to a standard echo-planar imaging template based on the standard Montreal Neurological Institute space [24] with an affine transformation followed by a non-linear approach with a 4 × 5 × 4 basis functions. Images, originally collected at 2.5 mm × 2.5 mm × 2.5 mm, were resampled at 2 mm × 2 mm × 2 mm voxels. Finally, data were spatially smoothed with a Gaussian kernel of full-width half maximum (FWHM) of 5 mm × 5 mm × 5 mm.

We extensively evaluated the effects of macro- and micro-motion and our general conclusion was that covariation with motion effects on ICA were very subtle and can be corrected by covariation post ICA, which does not impact the order selection [25].

4. RESULTS

4.1. Order Selection

Order selection plays an important role when data, such as our resting state data obtained from subjects with stroke, demonstrates high subject variability. We looked at information-theoretic criteria to decide the number of components to estimate. A downsampling estimator has been used to first generate independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) samples and then estimate the number of independent components found within a given dataset [11]. More recent work jointly estimates order and downsampling depth to produce i.i.d. samples using information-theoretic criterion leading to slightly higher orders [26]. The higher order yielded by [26] produced components of interest in the frontal, parietal, and temporal regions not observed at lower order ICA. Using the approach in [26] the average order is 25 with a standard deviation of 26. Due to the large standard deviation, we estimated components at a range of orders from 20 to 100 in steps of 10. At order 80 the component estimates produced meaningful components with higher t-values than those at lower orders; at higher orders, the components of interest become fragmented into separate spatial maps. We analyzed each component’s low frequency to high frequency power ratio, using the Group ICA of fMRI Toolbox (GIFT), and only retained meaningful components removing eye motion, gray matter, spinal fluid, and other artifacts. Other work has also made use of higher orders in order to provide a more detailed view of functional activity [12, 27, 28].

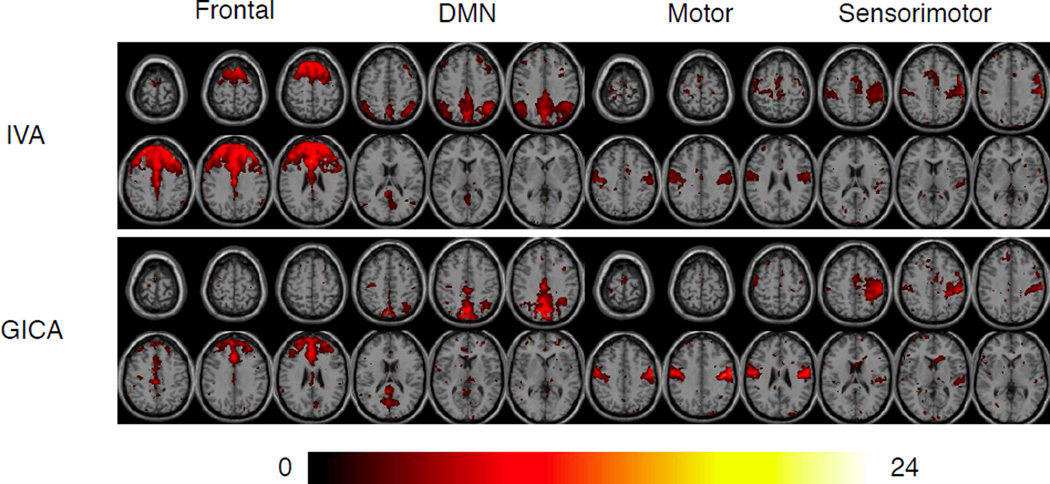

The two algorithms, IVA-GL and Infomax-L within GICA, produced comparable components at order 80. The frontal component seen in Figure 4 is an example where IVA provided a statistically more significant and spatially meaningful decomposition when compared with GICA. IVA makes use of dependence across datasets to produce components with better defined spatial areas. However, GICA seems to generate components which are more representative of what all subjects have in common, see the t-maps from the post-group results in Figure 4. The positive values are shown for each component, whereas sparse negative values located outside of the region of interest are de-emphasized. Plots are thresholded at p-values less than or equal to 0.05.

Fig. 4.

Example t-maps (one-sample) for components derived from IVA and GICA decompositions, thresholded at p < 0.05. It is seen that IVA typically produces components with more activated voxels and better definition of components as is the case for DMN.

4.2. Clustering Coefficient

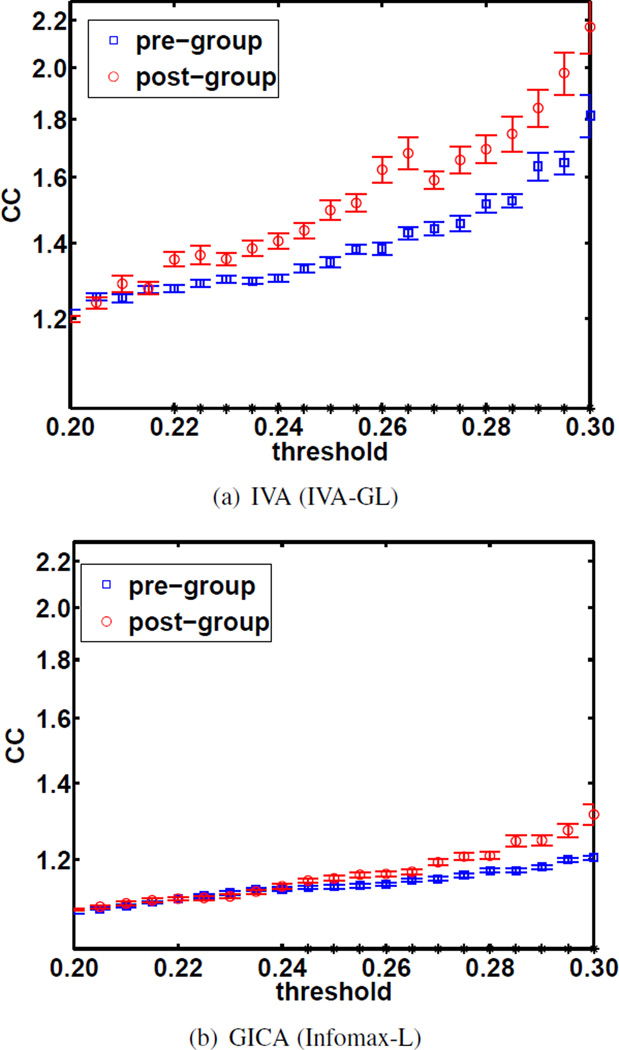

Functional network shifts toward random networks has previously been demonstrated in stroke and other brain pathologies, such as brain tumors [19], Alzheimer’s disease [20], and epilepsy [21]. The average clustering coefficients were calculated using a range of thresholds for the components generated by IVA-GL and Infomax-L, see Figures 5(a) and Figure 5(b), respectively. The blue markers indicate the pre-group and the red indicate the post-group.

Fig. 5.

clustering coefficient vs threshold plots using FNC validation. An asterisk on the x-axis indicate a statistically significant difference in clustering coefficients.

We expect individuals with stroke to have lower clustering coefficients than healthy control subjects due to disrupted connectivity. We also expect that improvements in terms of graph-theoretic features will be seen following rehabilitation training. Indeed, a higher clustering coefficient was identified at post-training compared to pre-training, suggesting improved local efficiency in information transfer. IVA better preserved the quality of component clustering at the subject level which is evidenced by the larger difference between pre-training and post-training values.

The two-sample t-test, from FNC validation, shows that the difference in clustering was statistically significant for both GICA and IVA components thus giving us confidence that clustering improved by post-training. An asterisk on the x-axes in Figure 5 indicates a statistically significant difference was found at the corresponding threshold. For GICA all false discovery rate (FDR) adjusted p-values are below 0.028, whereas for IVA all FDR adjusted p-values are below 0.018, thus IVA was better able to highlight the difference that we expected to find between pre- and post-training. This ability to identify changes as a result of training in terms of GT features makes IVA an attractive analysis tool for classification.

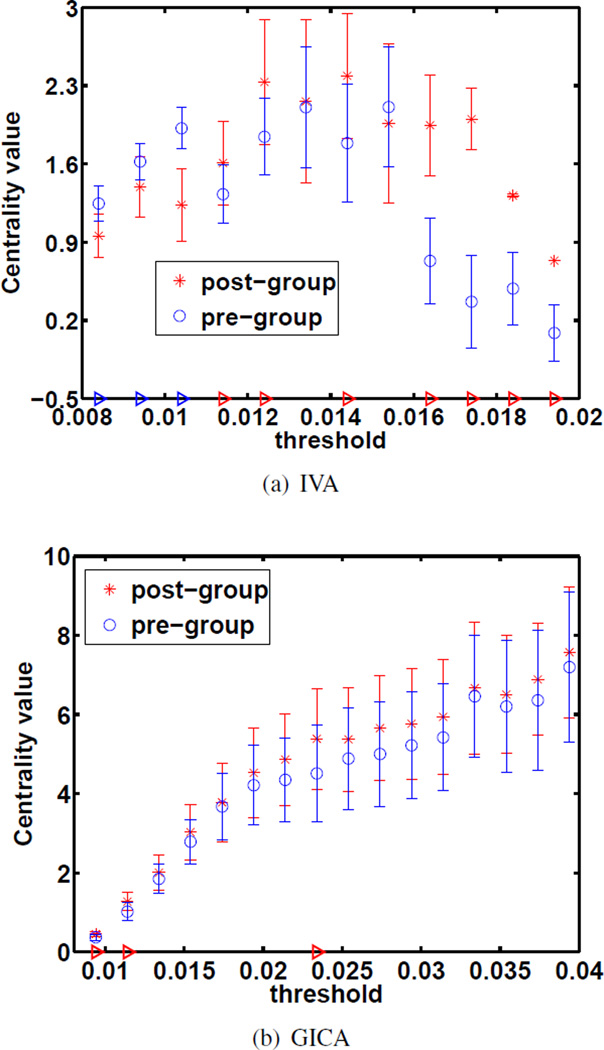

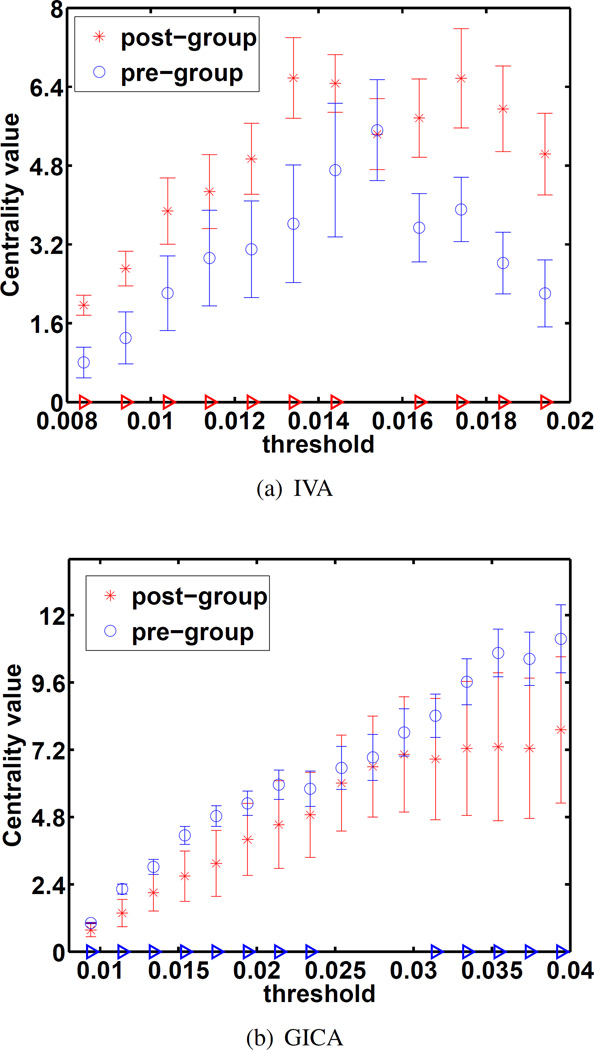

4.3. Centrality

Nodes with high centrality are important in terms of the functional organization of the brain as these nodes have mutual information with nodes from several clusters. Component clustering is disrupted by several brain pathologies, this in turn can affect the centrality of a given node. A red triangle along the x-axis of Figures 6 and 7 indicates significantly higher centrality by post-training compared to pre-training, whereas a blue triangle indicates significantly higher centrality at pre-training compared to post-training. An unpaired two-sample t-test was taken across the centrality of 20 randomly selected subgroups for FNC validation. The statistical difference in these centrality plots is at least an order of magnitude more significant in the IVA case compared with the GICA case. The centrality of motor components was found to significantly increase by post-training, see Figures 6 and 7. This suggests an increase in their importance in the functional brain network. In Figure 7 the IVA results show a very significant increase in centrality whereas the GICA results show an a less significant decrease. Using a naive Bonferroni correction [29] for both maintains a statistically significant increase for the IVA case but the GICA result loses statistical significance. IVA’s components produced more discriminating GT features at the subject level which highlight the differences we expect to find.

Fig. 6.

Centrality plots for the primary motor component. The FDR adjusted p-values for significant differences are p = 0.0088 for IVA and p = 0.032 for GICA. Using sFNC validation, IVA showed a more significant group difference.

Fig. 7.

Centrality plots for the sensorimotor component. The FDR adjusted p-values for significant differences are p = 1.8 × 10−5 for IVA and p = 0.039 for GICA. Using sFNC validation, IVA showed a more significant group difference.

Mutual information values between components were larger in general for GICA than those of IVA suggesting that IVA was better able to maximize independence by exploiting the additional diversity of dependence across datasets. The threshold range was increased for the GICA case in order have comparable graph densities over which to calculate centrality.

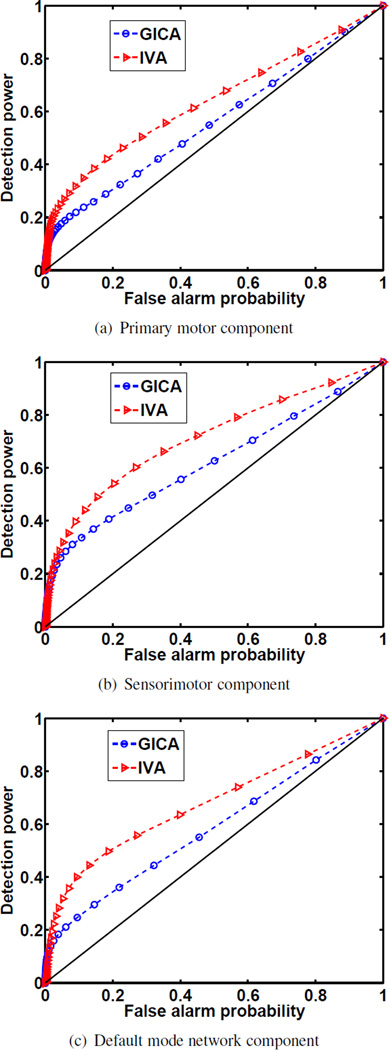

4.4. Component Masks

The IVA-estimated motor and DMN components are of particular interest in this study. The somatosensory input, Brodmann areas 1, 2, and 3, to the motor cortex, Brodmann area 4, was found to play a critical role in motor relearning after stroke [30]. Jointly, the somatosensory area and motor cortex spatially comprise the motor components of interest. This spatially continuous region comprised of Brodmann areas 1, 2, 3, and 4 was used to create the motor component mask. Brodmann areas 7, 10, 23, 31, and 39 were used for the DMN mask [22]. The masks were made using the WFU PickAtlas software toolbox [31, 32]. Though the method of applying a mask to a component provides a good method of comparison, it has limited application as it must assume that the component corresponds to the selected Brodmann areas, can only consider one component at a time, and does not take component connectivity into account. Graph-theoretic features can compare connectivity across patient components allowing us to compare these results to those of networks intrinsically found in healthy subjects. Graph-theoretic methods are hence robust to differences in the spatial component activation areas unlike analysis using predetermined masks. Nevertheless, to compare spatial components estimated by both algorithms, the masks were applied at varying thresholds across component z-maps. Some GICA components, such as the primary motor component in Figure 4, have larger voxel values which are important for smaller thresholds in ROC curves; nevertheless, the number of active voxels and their location may be more dominant features in ROC analysis. The area under the curve (AUC) is of interest because the ROC curve is not considered to be the ground truth and is not an ROC in the traditional sense. Using FNC validation to subsample both groups, the average spatial maps were calculated. The AUC was then calculated for each subgroup. We found that the IVA results produced components that better fit the selected Brodmann areas as seen in Figure 8, and that the difference in AUC values was statistically significant.

Fig. 8.

ROC curves for generating AUC values. A two-sample t-test was taken across 20 AUC values generated by randomly selected subgroups. The p-value indicating the level of statistical difference in AUC values for 8(a), 8(b), and 8(c), are p = 3.2 × 10−6, p = 2.6 × 10−9, p = 1.7 × 10−19, respectively. The IVA-estimated spatial components better fit the the Brodmann areas of the motor region and default mode network.

5. SUMMARY

We presented a graph-theoretical framework to effectively compare the multivariate results of JBSS algorithms in terms of their ability to capture subject variability in fMRI data in order to make effective group comparisons which is fundamental in medical research. The multivariate results are concisely summarized into GT features which concisely describe them. The IVA results produced very discriminating GT features due to the preservation of subject variability. The data from individuals with stroke was collected at both pre-training and post-training aimed at improving arm and hand function. We compared the average clustering coefficient from the results of IVA and GICA and found that the IVA results highlighted the difference that we expected to find. IVA better captured an increase in the motor component’s centrality for the post-group and resulted in spatially meaningful components leading to more powerful GT features for group comparison. Additionally, we suggest that higher order selection can significantly improve component estimation and is an important consideration when there is large subject variability as found in our data obtained from individuals with stroke. Thus we emphasize the use of IVA for effectively capturing subject variability to better highlight group differences found through the application of GT analysis of functional brain networks.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the UMB-UMBC Research and Innovation Partnership Seed Grant Program and by the NSF grant NSF-CCF 1117056.

REFERENCES

- 1.Calhoun VD, Adalı T, Pearlson GD, Pekar JJ. A method for making group inferences from functional MRI data using independent component analysis. Human Brain Mapping. 2001;14(3):140–151. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erhardt E, Rachakonda S, Bedrick E, Allen E, Adalı T, Calhoun V. Comparison of multi-subject ICA methods for analysis of fMRI data. Human Brain Mapping. 2011;32:2075–2095. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen EA, Erhardt EB, Wei Y, Eichele T, Calhoun VD. Capturing inter-subject variability with group independent component analysis of fMRI data: A simulation study. NeuroImage. 2012;59(4):4141–4159. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michael A, Anderson M, Miller R, Adalı T, Calhoun VD. Preserving subject variability in group fMRI analysis: Performance evaluation of GICA versus IVA. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 2014;8(106) doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dea J, Anderson M, Allen E, Calhoun V, Adalı T. IVA for multi-subject FMRI analysis: A comparative study using a new simulation toolbox. Machine Learning for Signal Processing (MLSP), 2011 IEEE International Workshop on. 2011:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma S, Phlypo R, Calhoun V, Adalı T. Capturing group variability using IVA: A simulation study and graph-theoretical analysis. Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2013 IEEE International Conference on. 2013:3128–3132. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gopal S, Miller R, Adalı T, Baum S, Calhoun V. A study of spatial variation in fMRI brain networks via independent vector analysis: Application to schizophrenia. Pattern Recognition in Neuroimaging (PRNI), 2014 International Workshop on; June 4–6.2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson M, Adalı T, Li X-L. Joint blind source separation with multivariate gaussian model: Algorithms and performance analysis. Signal Processing, IEEE Transactions on. 2012;60(4):1672–1683. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esposito F, Scarabino T, Hyvarinen A, Himberg J, Formisano E, Comani S, Tedeschi G, Goebel R, Seifritz E, Salle FD. Independent component analysis of fMRI group studies by self-organizing clustering. NeuroImage. 2005;25(1):193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JH, Lee TW, Jolesz FA, Yoo SS. Independent vector analysis (IVA): multivariate approach for fMRI group study. Neuroimage. 2008;40(1):86–109. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y-O, Adalı T, Calhoun VD. Estimating the number of independent components for fMRI data. Human Brain Mapping. 2007;28:1251–1266. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma S, Calhoun VD, Eichele T, Du W, Adalı T. Modulations of functional connectivity in the healthy and schizophrenia groups during task and rest. Neuroimage. 2012 Sep;62(3):1694–1704. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jafri MJ, Pearlson GD, Stevens M, Calhoun VD. A method for functional network connectivity among spatially independent resting-state components in schizophrenia. NeuroImage. 2008;39(4):1666–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu Q, Allen EA, Sui J, Arbabshirani MR, Pearlson G, Calhoun VD. Brain connectivity networks in schizophrenia underlying resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging. Curr Top Med Chem. 2012;12(21):2415–2425. doi: 10.2174/156802612805289890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Liang M, Zhou Y, He Y, Hao Y, Song M, Yu C, Liu H. Disrupted small-world networks in schizophrenia. Brain. 2008;131(4):945–961. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L, Yu C, Chen H, Qin W, He Y, Fan F, Zhang Y, Wang M, Li K, Zang Y, Woodward TS, Zhu C. Dynamic functional reorganization of the motor execution network after stroke. Brain. 2010;133(4):1224–1238. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq043. [Online]. Available: http://brain.oxfordjournals.org/content/133/4/1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sporns O, Honey CJ, Kötter R. Identification and classification of hubs in brain networks. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(10):e1049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laney J, Westlake K, Ma S, Woytowicz E, Adalı T. Capturing subject variability in data driven fmri analysis: A graph theoretical comparison. Information Sciences and Systems (CISS), 2014 48th Annual Conference on. 2014 Mar;:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartolomei F, Bosma I, Klein M, Baayen J, Reijneveld J, Postma T, Heimans J, van Dijk B, de Munck J, de Jongh A, Cover K, Stam C. Disturbed functional connectivity in brain tumour patients: Evaluation by graph analysis of synchronization matrices. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2006;117:2039–2049. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Haan W, Pijnenburg Y, Strijers R, van derMade Y, van der Flier W, Stam CSP. Functional neural network analysis in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease using EEG and graph theory. BMC Neuroscience. 2009;10:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Dellen E, Douw L, Baayen J, Heimans J, Ponten S, Vandertop W, Velis D, Stam C, Reijneveld J. Long-term effects of temporal lobe epilepsy on local neural networks: A graph theoretical analysis of corticography recordings. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Correa N, Adalı T, Calhoun VD. Performance of blind source separation algorithms for fMRI analysis using a group ICA method. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2007;25(5):684–694. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friston K. SPM. 2013 Jan. [Online]. Available: http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friston K, Ashburner J, Frith CD, Poline J-B, Heather JD, Frackowiak R. Spatial registration and normalization of images. Human Brain Mapping. 1995;3:165–189. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Damaraju E, Allen E, Calhoun VD. Impact of head motion on ica-derived functional connectivity measures. Biennial Conference on Resting State Brain Connectivity. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X-L, Ma S, Calhoun VD, Adalı T. Order detection for fMRI analysis: Joint estimation of downsampling depth and order by information theoretic criteria. IEEE Int. Symp., Biomedical Imaging: From Nano to Macro. 2011 Apr.:1019–1022. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiviniemi V, Srarck T, Remes J, Long X, Nikkinen J, Haapea M, Veijola J, Moilanen I, Isohanni M, Zang Y, Tervonen O. Functional segmentation of the brain cortex using high model order group PICA. Human Brain Mapping. 2009;30:3865–3886. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allen EA, Erhardt EB, Damaraju E, Gruner W, Segall JM, Silva RF, Havlicek M, Rachakonda S, Fries J, Kalyanam R, Michael AM, Caprihan A, Turner JA, Eichele T, Adelsheim S, Bryan AD, Bustillo J, Clark VP, Feldstein Ewing SW, Filbey F, Ford CC, Hutchison K, Jung RE, Kiehl KA, Kodituwakku P, Komesu YM, Mayer AR, Pearlson GD, Phillips JP, Sadek JR, Stevens M, Teuscher U, Thoma RJ, Calhoun VD. A baseline for the multivariate comparison of resting-state networks. Front Syst Neurosci. 2011;5:2. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bland JM, Altman DG. Multiple significance tests: the bonferroni method. BMJ. 1995;310(6973):170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6973.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schaechter JD, van Oers CAMM, Groisser BN, Salles SS, Vangel MG, Moore CI, Dijkhuizen RM. Increase in sensorimotor cortex response to somatosensory stimulation over subacute poststroke period correlates with motor recovery in hemiparetic patients. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 2012;26(4):325–334. doi: 10.1177/1545968311421613. [Online]. Available: http://nnr.sagepub.com/content/26/4/325.abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, Burdette JH. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. NeuroImage. 2003;19(3):1233–1239. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maldjian JA BJ, Laurienti PJ. Precentral gyrus discrepancy in electronic versions of the Talairach atlas. Neuroimage. 2004;21(1):450–455. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]