Abstract

Understanding of the cellular mechanisms underlying brain functions such as cognition and emotions requires monitoring of membrane voltage at the cellular, circuit, and system levels. Seminal voltage-sensitive dye and calcium-sensitive dye imaging studies have demonstrated parallel detection of electrical activity across populations of interconnected neurons in a variety of preparations. A game-changing advance made in recent years has been the conceptualization and development of optogenetic tools, including genetically encoded indicators of voltage (GEVIs) or calcium (GECIs) and genetically encoded light-gated ion channels (actuators, e.g., channelrhodopsin2). Compared with low-molecular-weight calcium and voltage indicators (dyes), the optogenetic imaging approaches are 1) cell type specific, 2) less invasive, 3) able to relate activity and anatomy, and 4) facilitate long-term recordings of individual cells' activities over weeks, thereby allowing direct monitoring of the emergence of learned behaviors and underlying circuit mechanisms. We highlight the potential of novel approaches based on GEVIs and compare those to calcium imaging approaches. We also discuss how novel approaches based on GEVIs (and GECIs) coupled with genetically encoded actuators will promote progress in our knowledge of brain circuits and systems.

Keywords: GECI, GEVI, membrane voltage, neurophysiology, optical imaging

the importance of studying voltage signals within biological organisms was realized as far back as the eighteenth century by the scientist Luigi Galvani (1737–1798). Galvani proposed that electrical forces power movement in animals, which he termed “animal electricity”; thus all life is electrical (Bresadola 2008). Galvani's seminal work inspired the invention by Alessandro Volta of the first electric battery, used by Michael Faraday and other pioneers of physics. In a straightforward manner, biology gave birth to the modern physics of electricity and electronic circuits. This enormous contribution of biology to the modern world is often overlooked.

Electrophysiological measures, instigated by Galvani, Volta, Helmholtz, Bernstein, Adrian, Renshaw, Curtis, Cole, Hodgkin, Huxley, and others, have become a key methodology in neuroscience because fluctuations of membrane potential both are the physical means of signal transmission among the elements of a neuronal circuit and comprise the substrate of fast information processing (integration) in the brain. It is therefore indubitable that detecting and recording voltage changes from neurons in living animals and linking these signals to cognitive and emotional tasks is required for understanding the mammalian brain. In this review we explore the idea that the brain is essentially an electric information processing device with simultaneous multisite processing and that, consequently, simultaneous multisite voltage imaging at the cellular, circuit, and system levels is necessary for understanding the cellular mechanisms of brain function.

After many decades of methodological refinement, electrophysiology has become the standard to investigate neuronal signals at the level of single cells, dissected networks, and intact brains. The most traditional tools of an electrophysiologist are electrodes of various types. Metal and glass electrodes can be optimized for different types of recordings, such as those placed on the scalp to record an EEG or others that are inserted into single nerve cells (intracellular microelectrodes). Electrodes can record neuronal voltage signals on a microsecond timescale with ease and excellent fidelity. However, classical electrophysiology suffers from a strict limitation: while signals of individual cells can be readily recorded, it is impractical to parallelize this technique to obtain recordings from more than a few tens of individual cells simultaneously. Because mammalian brain function is based on the organized (orchestrated) operation of a very large number of neurons, the neuronal mechanism of higher brain functions (i.e., cognition and emotions) cannot be deduced from signals of a few selected cells. Techniques such as electroencephalography provide recordings from very large populations of cells, but at a loss of cellular resolution, and therefore they cannot reveal detailed information about how specific circuit elements (nerve cells, nerve tracts, nerve nuclei) generate brain signal output.

Optical Reporters of Neuronal Activity

The above limitations of classical microelectrode-based electrophysiology may be overcome by optical imaging methods using molecular reporters (dyes and fluorescent proteins) that convert neuronal physiological signals into optically detectable signals. Indeed, seminal voltage-sensitive dye and calcium-sensitive dye imaging studies have demonstrated parallel detection of electrical activity across populations of interconnected neurons in a variety of preparations including invertebrate ganglion, cultured neurons, brain slice, and cortex in vivo (Cohen et al. 1978; Cohen and Salzberg 1978; Grinvald et al. 1977; Grinvald and Hildesheim 2004; Petersen et al. 2003; Salzberg 2009; Salzberg et al. 1977). Traditional optical imaging techniques have used several kinds of low-molecular-weight dyes. Voltage-sensitive dyes produce optical signals directly related and proportional to neuronal membrane potential changes, while calcium-sensitive or pH-sensitive indicators, on the other hand, provide optical signals that are only indirectly related to neuronal activity. The temporal resolution of calcium imaging is limited by calcium ion dynamics in the neurons and usually too slow for following brain oscillations at frequencies > 10 Hz. In contrast, voltage imaging does not have this limitation. Calcium indicators usually produce larger signals (fractional changes in fluorescence), while voltage-sensitive dyes provide relatively small optical signal. As calcium imaging combines more easily detected slow signals with large fractional changes, it is used more frequently than voltage-sensitive dyes to monitor neuronal “electrical activity,” as a compromise between what is needed and what is feasible.

Optical imaging experiments using extracellularly applied cell-permeant AM ester calcium indicators or extracellularly applied voltage-sensitive dyes meet the requirement of simultaneously monitoring a large number of brain cells. However, these dyes stain all nerve cells and components of all neuronal circuits unselectively. As such, recordings using these dyes are usually blind to the identity and diversity of individual neurons, particular neuronal classes defined by the transmitter they use (e.g., glutamatergic vs. GABAergic neurons), connectivity (cortico-pontine vs. commissural pyramidal neurons), and emerging functional groupings (neural ensembles). Even more limiting is the fact that low-molecular-weight dyes indiscriminately stain nonneuronal brain cells (astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia, ependymal cells, blood vessels, etc.), which may result in large background signals and two kinds of debilitating interferences: 1) reduced quality of neuronal optical signals (poor signal-to-noise ratio) and 2) confusion of biological signals—the optical signals from nonneuronal cells mix with optical signals from neurons (Konnerth et al. 1987). Finally, and equally debilitating, is the fact that calcium-sensitive dyes and voltage-sensitive dyes are incompatible with long-lasting animal models that are required for linking brain activities and behavior.

GEVIs and GECIs.

A game-changing advance made in recent years has been the conceptualization and development of genetically encoded calcium and voltage indicators (GECIs and GEVIs) (Knopfel 2012; Knopfel et al. 2006; Miyawaki et al. 1997; Siegel and Isacoff 1997). Compared with low-molecular-weight indicators (“dyes”), the imaging approaches based on GECIs and GEVIs are 1) cell type specific, 2) less invasive (removal of dura mater is not required), and 3) able to relate activity and anatomy. Most importantly, they allow long-term recordings of individual cells' activities over weeks and thereby allow direct monitoring of the emergence of learned behavior and underlying circuit mechanisms.

The most recent versions of the GECIs (e.g., GCaMP5, GCaMP6, etc.), are considered to surpass the performance of small-molecule Ca2+ indicators (Chen et al. 2013). GECI imaging allows one to monitor routinely the action potential (AP) activity of hundreds of cortical pyramidal cells. GECI imaging is now being extended to GABAergic cells that provide smaller yet resolvable AP-related GECI signals (Chen et al. 2013; Muldoon et al. 2015). Transgenic mice that allow for Cre-dependent targeting of cell classes with GCaMP6f and -s are also now available to the broader community (Madisen et al. 2015).

The success of GECI-based imaging approaches may prompt us to question the need for GEVI-based imaging. In response to this conjecture, three facts stand out. 1) GEVIs enable measurements of voltage transients that are refractory to Ca2+ imaging (that is to say, Ca2+ imaging is blind to some essential neuronal signals). 2) In addition to being blind to some electrical phenomena, Ca2+ imaging is also contaminated with signals remotely related to the neuronal membrane potential (Table 1). 3) GEVI imaging should be conceptualized differently from Ca2+ imaging (each recording mode GECI and GEVI has a specific significance to the INPUT-OUTPUT feature of the neural circuit; see below).

Table 1.

Limitations of calcium imaging

| a. Internal release. Fluctuations in internal calcium unrelated to electrical signals. | Strong calcium signals, generated upon release of calcium ions from internal calcium stores, may appear in a calcium imaging trace. These calcium transients have a highly complicated relation to the membrane potential changes or no relation at all (Manita et al. 2011; Miyazaki et al. 2012). |

| b. Slow response. Distorted rising phase. Distorted falling phase. | The calcium signal dynamics is significantly slower than membrane voltage changes. Consequently, the propagation of electrical transients in terms of both direction and velocity, while apparent in voltage imaging experiments (Antic 2003), cannot be inferred from calcium imaging studies (Schiller et al. 1995). |

| c. AP frequency. Spike count. Spike timing. | The precise number and frequency of APs in high-frequency bursts, while apparent in voltage imaging experiments (Zhou et al. 2007), cannot be determined based on the calcium signals (Kampa and Stuart 2006). |

| d. Subthreshold potentials. Plateau depolarization. | A cardinal limitation of calcium signals is the inability to resolve subthreshold depolarizations preceding or following AP firing (Fig. 1, depolarization envelope). Understanding subthreshold events before and after AP firing is necessary for understanding signal integration in neurons (Koch and Segev 2000). |

| e. Calcium signal amplitude is often not correlated with the amplitude of local voltage change. | A major impediment of calcium imaging is that the signal amplitude is a function of local voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and NMDA receptor density, surface-to-volume ratio of the neuronal compartment, property of the calcium indicator, and property of intrinsic intracellular Ca2+ buffer density (Frick et al. 2001; Helmchen et al. 1996). Dendritic segments with higher density of these channels report stronger signals for the same voltage change; thus one should always be careful when trying to extract voltage amplitudes from calcium imaging data. |

Conceptual difference between GEVI and GECI signals.

Because of the inherent properties of the genetically encoded indicator molecules, 1) mode (calcium or voltage), 2) site of protein expression (dendrites, axons, soma), and 3) sensitivity (AP vs. synaptic potential), GEVI signals largely represent synaptic INPUT arriving into a neural circuit, while GECI signals (in large-scale imaging experiments) represent AP OUTPUT generated in the neural circuit. Integration of synaptic inputs comprises the first stage of neuronal information processing (Poirazi et al. 2003). Monitoring the INPUT into a neural circuit via a GEVI is necessary for investigating neuronal computations, while AP monitoring via GECIs only informs about the result of the computation. Unlike Ca2+ signals in large-scale Ca2+ imaging experiments, optically recorded voltage signals are not limited to neuronal cell bodies (actually they mainly represent signals from dendrites, the main contributors to the plasma membrane). Therefore, GEVIs allow voltage measurements of the synaptic input arriving simultaneously in multiple neurons.

Limitations of calcium imaging for voltage measurements.

Calcium-based optical signals from the soma, dendrites, and axon of individual neurons suffer from several limitations that preclude their use for analyzing electrical signal integration in central nervous system neurons (Table 1).

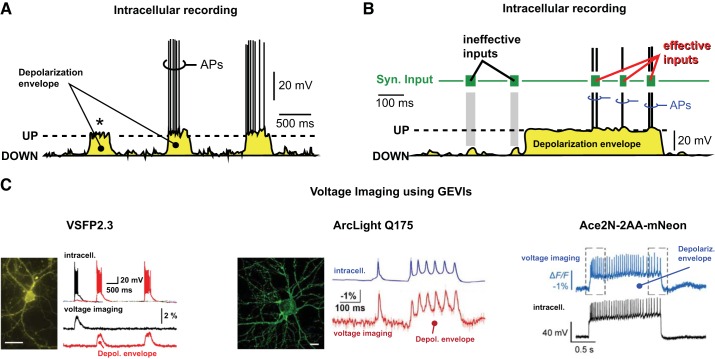

GEVIs enable measurements of voltage transients that are refractory to Ca2+ imaging. Some major cell classes (GABAergic interneurons) generate very narrow APs that are not accompanied by large Ca2+ transients (Evstratova et al. 2011; Franconville et al. 2011). Hyperpolarizing events and subthreshold depolarizing synaptic events are not associated with large Ca2+ influxes. Neuronal oscillatory activities may be subthreshold for activation of voltage-gated calcium channels (and hence are not associated with detectable Ca2+ transients) but could facilitate synchronous interactions by biasing neurons to discharge within the same time frame (Engel et al. 2001; Petersson and Fransen 2012; Yu and Ferster 2010). Indeed, Ca2+ imaging is “blind” to sustained depolarizations with amplitudes of ∼20 mV that occur in cortical pyramidal neurons in the absence of AP firing (Petersson and Fransen 2012; Yu and Ferster 2010) (Fig. 1A, asterisk). The main effect of the oscillatory modulation of neuronal membrane potential (spikeless UP state) is that it constrains the time interval (usually 200–500 ms) during which nerve cells are susceptible to excitatory input and can begin to reliably emit bursts of APs based on that afferent input (Fig. 1B, APs). While GECIs are completely ineffective reporters of subthreshold physiological states, GEVIs can detect slow components of membrane potential transients (depolarization envelopes) (Fig. 1A). The sustained plateau depolarizations (depolarization envelope) may represent activated neuronal states (UP states), when pyramidal neurons are closer to the AP threshold. Synaptic inputs that are ineffective in DOWN state become effective in UP state, resulting in the generation of the neuronal OUTPUT—APs (Fig. 1B). In fact, slower GEVIs are good filters for extraction of subthreshold depolarizations (Fig. 1C, depolarization envelope).

Fig. 1.

Depolarization envelope. A: neuronal membrane potential oscillates between DOWN and UP states in response to glutamatergic input via microiontophoresis (ex vivo) (Milojkovic et al. 2004) or physiologically in vivo (Steriade et al. 2001). B: the same kind of synaptic input is ineffective in the DOWN state but very effective during the UP state (generation of APs). C: 3 examples of published GEVI imaging illustrating reliable reporting of the slow component (depolarization envelope) of the membrane potential transients during underlying bursts of APs. Examples are taken from an early GEVI, VSFP2.3 (from Akemann et al. 2010 with permission; Lundby et al. 2008), a further evolved GEVI, ArcLight Q175 (from Han et al. 2013 with permission; Jin et al. 2012), and a more recently developed GEVI, Ace2N-2AA-mNeon (from Gong et al. 2015 with permission).

In summary, calcium imaging cannot faithfully measure membrane potential transients, and hence it cannot provide a complete description of voltage signals. GEVI-based approaches enable 1) efficient detection of neural ensembles, 2) efficient detection of network properties, and 3) detection of rhythmic and synchronized activities (orchestration) and exploration of their underlying circuit mechanisms. Thus GEVI-based optical imaging will be a “game-changer” for the study of large-scale dynamics, by allowing neuroscientists to selectively monitor the electrical synaptic INPUT to and OUTPUT from neurons of a chosen genetic type or connectivity pattern in behaving animals while observing the rich repertoire of electrical activity in those neurons.

Voltage imaging and calcium imaging are both very useful in experiments. Ideally, one would like to record calcium and voltage signals simultaneously (Canepari et al. 2007; Milojkovic et al. 2007; Vogt et al. 2011). A combined use of appropriate GEVIs and GECIs would make this possible in behaving animals.

Currently Available Voltage Indicators

Organic voltage-sensitive dyes.

Optical imaging of membrane voltage has its historical roots in the discovery of low-molecular-weight dyes (“organic dyes”) that stain plasma membranes and change their optical properties (absorption and/or fluorescence quantum yield) as a function of the voltage across the membrane (Davila et al. 1973). Organic voltage-sensitive absorption dyes may have lower phototoxicity than fluorescent dyes. Some well-characterized voltage-sensitive absorption dyes work with near-infrared light (>700 nm) and therefore can be combined with channelrhodopsin 2 (ChR2) optical stimulation. However, since absorption dyes require transillumination, most of their applications are on invertebrate ganglia and brain slices (Vranesic et al. 1994; Zecevic et al. 1989). The first fluorescent voltage-sensitive dyes reported APs from squid axons with changes of light intensities amounting to 10−6 to 10−3 of the baseline fluorescence (Davila et al. 1973; Tasaki et al. 1968). Compared with absorption dyes, fluorescent dyes are better suited for detecting voltage transients in axons and dendrites of individual neurons (Antic and Zecevic 1995) as well as for in vivo mammalian models (Grinvald 2005; Grinvald and Hildesheim 2004). Collaboration between organic chemists and biophysicists over several decades resulted in dyes that report membrane voltage transients with sensitivities exceeding 10−1/100 mV [expressed as change of light intensity (ΔF) over baseline (F), hence ΔF/F in % for 100-mV change in membrane potential], good photostability, and minimized side effects (Woodford et al. 2015; Yan et al. 2012). The finding that two-photon (2p) excitation is compatible with low-molecular-weight voltage-sensitive dyes (Fisher et al. 2005, 2008; Kuhn et al. 2008) opened exciting prospects of voltage imaging from deep brain structures and small neuronal compartments such as dendritic spines (see below). As discussed below in more detail, the use of voltage-sensitive dyes in physiological experimentation yielded important insights on the electrical signaling ranging from the small-scale subcellular level (individual neurons) to large-scale imaging experiments performed in awake monkeys (population of neurons) (Cohen et al. 1978; Grinvald and Hildesheim 2004).

GEVIs and cell-specific targeting.

GEVIs were envisaged soon after the discovery of green fluorescent proteins and primarily developed to overcome the limitations of low-molecular-weight voltage-sensitive dyes (Knopfel et al. 2006; Sakai et al. 2001; Siegel and Isacoff 1997). Pros and cons of low-molecular-weight indicators vs. GEVIs have been reviewed previously (Knopfel et al. 2006). The fundamental advantages of GEVIs are their inherent suitability to target specific cell classes and to read their activity without having to structurally resolve the cells; in contrast, classical voltage-sensitive dye imaging is blind to cellular identity. Important additional advantages of GEVIs over classical voltage dyes are 1) noninvasive (GEVI imaging can be performed with intact dura mater, unlike organic dyes, where dura surgery is necessary for staining; in fact, GEVIs can be imaged through the thinned skull in mice) and 2) long-lasting “staining” (GEVIs can be expressed life-long), both of which strongly facilitate longitudinal studies in intact, behaving animals.

GEVI evolution.

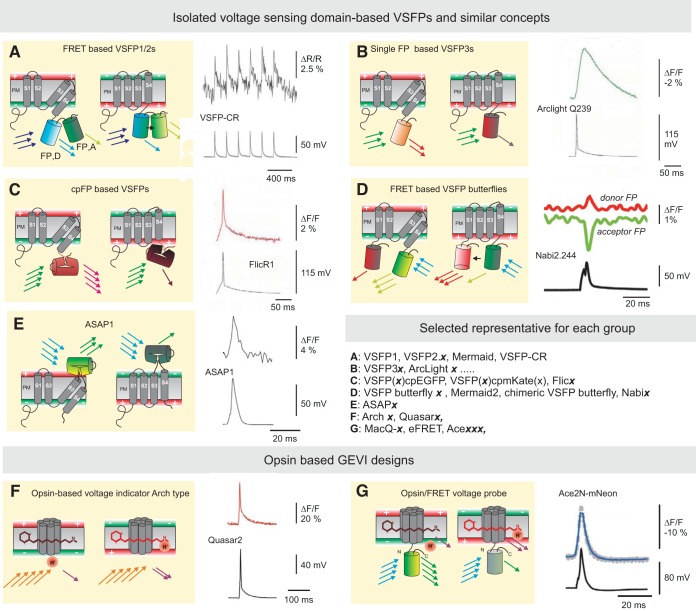

Development of GEVIs is currently a very active research field (Abdelfattah et al. 2016; Gong et al. 2015; Knopfel et al. 2015; Mishina et al. 2014; St-Pierre et al. 2014; Zou et al. 2014). The many different GEVIs published during recent years are essentially based on only two basic design principles (Fig. 2). The first design principle (“isolated voltage-sensing domain-based GEVIs,” Fig. 2, A–E) is to sense membrane voltage via an isolated voltage-sensing domain, such as the first four transmembrane segments (S1–S4) of voltage-gated potassium (Kv) channel subunits (also found in other voltage-gated ion channels and in voltage-sensitive phosphatases) (Sakai et al. 2001). This type of GEVI was introduced with the acronym VSFP (voltage-sensing fluorescent protein) and was the first that provided robust voltage reports from cultured mammalian cells (Baker et al. 2008; Dimitrov et al. 2007; Perron et al. 2009). VSFPs also were the first GEVIs enabling proof of principle for transcranial voltage imaging in living mice (Akemann et al. 2010). The second GEVI design principle (“opsin-based GEVIs,” Fig. 2, F and G) is based on the use of opsins (to which the endogenous polyene chromophore retinal binds) (Kralj et al. 2012). These Arch-type GEVIs originally had a very dim optical output, but this drawback has been subsequently corrected by molecular fusion with a fluorescent protein that is voltage dependently quenched by the opsin's retinal (Gong et al. 2014; Zou et al. 2014). The currently most sensitive (based on measurements in cultured cells) VSFP-type GEVIs are the single-color-emission ASAP1 (St-Pierre et al. 2014) and FlicR1 (Abdelfattah et al. 2016) and the two-color-emission VSFP-butterfly family (Akemann et al. 2012; Sung et al. 2015).

Fig. 2.

Overview of GEVI molecular designs: voltage-sensing domain-based and opsin-based GEVIs. Each of A–G displays a schematic depiction of 1 GEVI type with conformation at resting membrane voltage and after membrane depolarization along with an example optical recording trace obtained with a leading representative. A: FRET-based voltage-sensitive probes of the VSFP1/2 type where a pair of fluorescent proteins (FP,D: FRET donor; FP,A: FRET acceptor) is attached to a voltage-sensor domain, consisting of four segments (S1–S4). Depolarization of membrane voltage induces a rearrangement of the 2 fluorescent proteins with an increase in FRET (black arrow) that is optically reported as a change in the ratio between donor and acceptor fluorescence. Example trace taken from Lam et al. (2012) with permission. B and C: single fluorescent protein and circularly permuted (cp) fluorescent protein probes of the VSFP3 family. Examples are ArcLight and FlicR1 (traces taken from Abdelfattah et al. 2016 with permission). D: in FRET-based voltage-sensitive probes of the VSFP-Butterfly family the voltage-sensor domain is sandwiched between two fluorescent proteins. FRET mechanism as in A; example trace for Nabi2.244 taken from Sung et al. (2015) with permission. E: in ASAPs a single cp fluorescent protein is inserted between the 3rd and 4th transmembrane voltage-sensing domains. Example trace taken from St-Pierre et al. (2014) with permission. F and G: in GEVIs based on opsins a change in membrane potential induces increased absorption of red light by the retinal chromophore. This effect is read out either via retinal fluorescence (F) or via quenching of a FP donor (G). Examples are Quasars (from Hochbaum et al. 2014 with permission) and Ace (from Gong et al. 2015 with permission). Also shown is a list of selected representatives for each group.

The most recent representative of opsin-based GEVIs, Ace2N-mNeon, allowed proof-of-principle demonstration of fast AP recording from a single cell using single-photon (1p) excitation imaging in a living, awake mouse (Gong et al. 2015). Despite this encouraging proof of principle, so far only a few GEVIs have produced robust signals in living mammalian preparations and been independently confirmed across several laboratories (Akemann et al. 2012; Madisen et al. 2015). Even fewer transgenic mice are available that facilitate the wide exploitation of GEVI imaging (Madisen et al. 2015). Because of a slow process from development of GEVIs to their application, only a small fraction of the first sufficiently well performing GEVIs have been employed in studies focusing on biological questions beyond methodological proof of principle (Carandini et al. 2015; Chang Liao et al. 2015; Scott et al. 2014).

Shortcomings of current GEVIs.

Although some of the most recently developed GEVIs exhibit response times as short as ∼1 ms, they are much slower than fast voltage-sensitive dyes, with temporal resolution of ∼1 μs (Salzberg et al. 1993). This severely limits the use of GEVIs in studies where the exact shape (and not just incidence) of APs is relevant. A second limitation of GEVIs is their nonlinear fluorescence-voltage relationship. While this nonlinearity can be exploited to maximize sensitivity (i.e., the slope of the fluorescence-voltage curve) around a voltage range of interest (Akemann et al. 2012), it complicates quantitative biophysical measurements. The third shortcoming of currently available GEVIs is their quite limited spectral range of excitation and emission wavelengths. In particular, GEVIs that operate in the near-infrared spectrum are lacking. Finally, it should be noted that GEVIs (like any membrane protein) add mobile charges to the membrane, increasing membrane capacitance. However, modeling and experimental studies suggested that this effect is of little practical concern with the expression levels usually archived (Akemann et al. 2009). Indeed, most recently published GEVIs have been tested negative on changes of AP widths as an indicator for an increased membrane capacitance (Akemann et al. 2012; Gong et al. 2015; St-Pierre et al. 2014).

Notwithstanding the need for further development and improvement of GEVIs, existing versions are already valuable tools that are currently facilitating the interrogation of neuronal circuits at multiple levels—ranging from dendritic signal processing (Gong et al. 2015) to cortical representations of sensory and motor information.

Single-Neuron Voltage Imaging Approaches

Voltage imaging at single-neuron level is necessary.

Current theories of brain functions are almost entirely based on large-scale network models operating on the “action potential concept.” In these mental and computational models, nerve cells are either active (making APs) or silent (not making APs). This concept grew out of experimental studies at a time when detection of AP (“spike”) firing was the only routinely feasible methodology available. The examples of experimental methods focused on detecting AP occurrence, AP frequency, and AP timing include single-unit recordings and, more recently, population Ca2+ imaging (Floresco and Grace 2003; Vogelstein et al. 2010; Williams and Goldman-Rakic 1995). One important pitfall of experimental methods based on the spike detection paradigm (single-unit recordings; see also GEVIs—a modern evolution from single-unit recordings and local field potentials, calcium imaging from the cell body) is the neglect of the fact that important aspects of information processing and synaptic modifications occur in nerve cells without resulting in the generation of any APs. Nerve cells that appear silent in single-unit recordings (no AP firing) may be experiencing dramatic membrane potential fluctuations in the form of localized dendritic potentials (Hausser et al. 2000). Excitatory synaptic inputs can trigger large depolarizations and regenerative potentials in remote segments of thin dendritic branches (Hausser et al. 2000). Because of the unfavorable direction of propagation from the dendrite into the soma (capacitive load), these dendritic spikes fail to depolarize the soma and bring the axon to AP generation threshold (Larkum et al. 2009). In essence, this depolarization exceeds threshold in the dendrite but remains subthreshold in the soma (Schiller et al. 2000). When constructing the “theory of the brain,” these kinds of voltage changes (threshold dendritic and subthreshold somatic depolarizations) must be taken into account for three important reasons.

1) In the total absence of somatic (axonal) AP firing, local voltage changes in the form of dendritic plateau potentials alternate the somatic membrane potential between a DOWN and an UP state (Milojkovic et al. 2004). The UP state produces a transient change in membrane excitability and influences the overall neuronal responsiveness (Fig. 1B). That is, the incoming synaptic inputs are processed differently in the UP state than in the DOWN state (Fig. 1B). During a sustained depolarization phase (UP state), the voltage-gated K+ current is inactivated (Hoffman et al. 1997) and the membrane potential is closer to the AP firing threshold (Lampl et al. 1999). The same synaptic input, previously ineffective, reliably drives AP initiation during the depolarized phase (McCormick et al. 2003).

2) In the absence of somatic AP firing, in apparently silent neurons the local dendritic spikes can change the long-term efficacy of local synaptic inputs (Golding et al. 2002). So, in the absence of somatic APs, local dendritic spikes provide necessary depolarization of the postsynaptic membrane, thus satisfying the Hebbian requirement for long-term potentiation (Lisman 1989).

3) Subthreshold depolarizations are known to propagate into the axon, alter the axonal membrane excitability, and potentially cause changes in the coupling efficiency with the downstream members of the neuronal network (Alle and Geiger 2006; Kole et al. 2007; Shu et al. 2006; Yu et al. 2010).

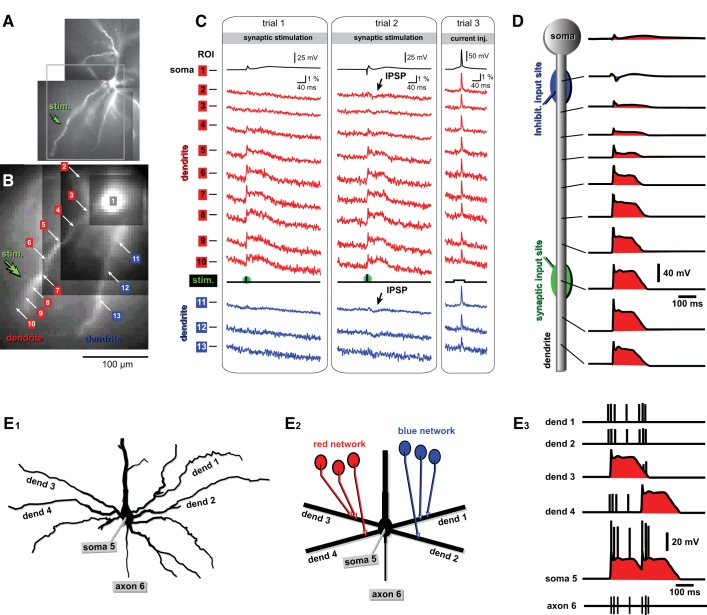

Sensory information enters the brain via APs and motor responses are also communicated via APs, but information processing between input and output relies on synaptic integration, which is governed by synaptic weights and membrane potential changes in dendrites. Since a very large component of the electrical signaling and signal integration is mediated by subthreshold potentials (Hausser et al. 2000; Poirazi et al. 2003; Schiller et al. 2000), experimental methods for monitoring subthreshold voltage transients by voltage imaging approaches are critical (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Voltage imaging of dendritic integration. A: compound photograph of a neuron; “stim.” marks position of the synaptic stimulation electrode. B: low-resolution image of the part of the dendritic tree where optical signals were recorded. Regions of interest (ROIs) are marked by numbers. C: simultaneous electrical (ROI 1) and optical (ROIs 2–13) recordings of dendritic membrane potential changes upon a single synaptic stimulation shock (stim.). D: schematic representation of voltage waveforms along a basal dendrite receiving excitatory synaptic input in distal segment (green) and inhibitory synaptic input near the soma (blue). E1: basilar dendritic tree of a pyramidal neuron. E2: schematic representation of the basilar dendritic tree. Dendrites 1 and 2 receive inputs from a “blue” network of neurons. Dendrites 3 and 4 receive inputs from a “red” network of neurons. E3: dendritic voltage waveforms explain the origin of somatic and axonal electrical responses.

Voltage imaging of dendrites and spines.

Pyramidal cells with large and complex dendritic trees comprise 80% of all nerve cells in cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Cortical pyramidal cells are divided into subclasses that differ in location of their soma within layers 2–6, dendritic morphology, axonal projections that they typically make, afferent input they receive, and their electrical properties. Because of their complex structure (Mainen et al. 1996) and the variety of voltage-gated channels nonuniformly distributed along this structure (Hoffman et al. 1997; Kole et al. 2006), cortical pyramidal neurons are neither isopotential nor electrotonically compact. By definition, two parts of the same cell are always experiencing vastly different voltage waveforms. In some cases, the voltage fluctuations in a remote dendritic segment do not produce any voltage signal in the cell soma (Fig. 3, A–C). Asymmetric voltage gradients (e.g., membrane voltage across the apical dendritic branches to soma vs. across basal dendrites of a L5 pyramidal cell) (Gong et al. 2015), as well as the highly nonlinear responses of individual neuronal compartments to excitatory inputs (Kim and Connors 1993; Schiller et al. 2000), are thought to constitute the essence of the neuronal computational capabilities (Archie and Mel 2000; Euler et al. 2002; Koch and Segev 2000). In an illustrative example shown in Fig. 3, E1–E3, some dendrites (dendrites 3 and 4) receive excitatory synaptic inputs from an active network of neurons (red network) and experience dendritic plateau potentials. Dendritic plateau potentials propagate to the soma and generate a pattern of APs riding atop sustained depolarizations (Fig. 3E3, soma 5). In this example, the firing pattern comprises two high-frequency bursts of APs. APs backpropagate into basal dendrites with different amplitude and duration of the voltage signal, depending on individual dendritic morphology, individual dendritic excitability, and individual history of dendritic activity (Zhou et al. 2008, 2015). Ca2+ imaging cannot resolve all individual APs in the soma, dendrite, and axon (Fig. 3E3). Thus imaging of somatic Ca2+ cannot confirm or reject the existence of the somatic plateau depolarization (Fig. 3E3, soma 5, red depolarization envelope). Moreover, Ca2+ imaging cannot easily resolve a Ca2+ flux due to synaptically evoked dendritic plateau potential from a Ca2+ influx due to a burst of backpropagating APs in the dendrite. Efficient experimental access to dendritic voltage waveforms, as depicted in Fig. 3, C and D, would allow the interpretation of synaptic causes of the neuronal (soma and axon) output. The precise relation between afferent synaptic activity (INPUT) and soma/axon AP firing pattern (OUTPUT) is the ultimate goal of cellular neuroscience: to understand how a neuron converts incoming information, in the form of active synapses, into appropriate AP output.

Dendritic spines receive most excitatory inputs in the cortex, hippocampus, striatum, amygdala, and nucleus accumbens. Despite their potential importance in brain function, direct experimental evidence for electrical signaling in dendritic spines was lacking for a long time, as their small size made them inaccessible to patch electrodes (Stuart et al. 1993). Ca2+ imaging experiments showed that spines compartmentalize Ca2+ (Denk et al. 1996), but it was still unknown what role, if any, these dendritic outgrowths played in integrating electrical signals in the form of synaptic inputs. To investigate the electrical function of dendritic spines directly (not indirectly by calcium imaging), researchers initially used second harmonic generation (SHG) imaging of the membrane potential in pyramidal neurons from hippocampal cultures and neocortical brain slices. With FM 4-64 as an intracellular SHG chromophore, the membrane potential waveform was obtained in dendritic spines during somatic APs (Nuriya et al. 2006). SHG imaging was burdened with noisy signals, so researchers turned to voltage-sensitive dye imaging (Rama et al. 2010). To date, four general approaches have been used to achieve voltage-sensitive dye imaging in dendritic spines: 1) 1p confocal microscope imaging (Pages et al. 2011; Palmer and Stuart 2009), 2) 1p multisite recordings (Holthoff et al. 2010), 3) 2p voltage imaging (Acker et al. 2011; Acker and Loew 2013), and 4) laser-spot voltage imaging (Popovic et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2007). Because voltage-sensitive dye signals are difficult to calibrate in terms of absolute change in millivolts, voltage imaging of dendritic spines is often paired with multicompartmental biophysical models to decipher spines' passive and active properties. Dendritic spine voltage imaging unequivocally showed that somatic APs backpropagate into dendritic shafts and from dendritic shafts they strongly invade dendritic spines. The backpropagation of somatic APs into the dendritic tree generated voltage signals at dendritic spines with amplitude and kinetics similar to somatic ones (Holthoff et al. 2010; Palmer and Stuart 2009; Popovic et al. 2015). The transfer of voltage from large structures (dendritic shafts) to small structures (dendritic spines) is strong and consistent with theoretical observations involving “transfer impedance,” which reflect how a current applied at one location within a complex neuron affects membrane potential at other locations of the same neuron. Unlike transfer impedance, voltage transfer is not symmetric but instead depends on the direction of signal propagation. According to theory and computational biophysics, voltage transients in large compartments (e.g., dendrites) invade small compartments (e.g., dendritic spine) more efficiently than vice versa (Jaffe and Carnevale 1999; Segev and Rall 1998). Strong voltage transfer in the direction from dendritic shaft to dendritic spine was effectively confirmed by voltage imaging (Holthoff et al. 2010; Nuriya et al. 2006; Palmer and Stuart 2009; Popovic et al. 2015). There is less consensus as to what obstacle the dendritic spine neck resistance imposes on voltage transfer in the opposite direction, from spine to dendrite. Experimental measurements based on the interpretation of Ca2+ signals in dendritic spines initially suggested that neck resistance is large enough (∼500 MΩ) to substantially amplify the spine head depolarization associated with a unitary synaptic input by ∼1.5- to ∼45-fold, depending on parent dendritic impedance. Spines provide a consistently high-impedance input structure throughout the dendritic arborization (Harnett et al. 2012). More recent voltage imaging experiments, on the other hand, indicate that synapses on dendritic spines are not electrically isolated by the spine neck to a significant extent. Electrically, they behave as if they are located directly on the dendrites (Popovic et al. 2015).

Voltage imaging from axons.

Voltage-sensitive organic dyes have been successfully used to image APs in axons of cortical pyramidal neurons (Palmer and Stuart 2006; Popovic et al. 2011; Zhou et al. 2007) and cerebellar Purkinje cells (Foust et al. 2010). Besides the axonal initial segment, the AP waveforms were analyzed in intracortical axon collaterals and en passant presynaptic terminals of layer 5 pyramidal neurons (Foust et al. 2011). In astounding detail, these studies revealed the exact site of AP initiation in axons, the size of the AP initiation zone, and the saltatory conduction of AP across the nodes of Ranvier. At very high AP firing frequencies (up to 250 Hz), APs were observed to propagate faithfully into axon collaterals, in a saltatory manner (Foust et al. 2010), while AP propagation is nonsaltatory (monotonic) in immature axons prior to myelination (Popovic et al. 2011).

Voltage imaging from nerve terminals.

An interesting application of voltage imaging is the study of voltage transients in nerve terminals. The Salzberg group published a number of papers on voltage imaging from nerve terminals in the mammalian neurohypophysis, where the shape of the AP relates to the amount of hormones released (Fisher et al. 2008; Fisher and Salzberg 2015; Salzberg et al. 1983).

Circuit-Level Voltage Imaging Approaches

Classical voltage imaging with voltage-sensitive dyes has successfully dissected small neuronal networks in Crustacea and in Mollusca, particularly to monitor spike output from many neurons simultaneously and also to assess slower synaptic events (Parsons et al. 1989; Stadele et al. 2012; Zecevic et al. 1989). In more complicated mammalian systems pioneering work to assess local circuitry connections has used classical electrophysiology approaches such as paired (dual or multiple) intracellular electrical recordings (see Within-circuit neighbor-neighbor connections). More recently, the powerful application of pathway-specific ChR2-based optical stimulation alongside simultaneous measurement of voltage with multiple electrodes is revealing more information about how the properties of local connections among the circuit generate their output. For two recent examples see Fuchs et al. (2016) and Yang et al. (2013).

Within-circuit neighbor-neighbor connections.

Traditionally, local, neighbor-to-neighbor (or short range) connections within mammalian neuronal circuits are assessed with multiple simultaneous recordings with classical sharp or whole cell patch-clamp recording configurations. Each cell is triggered to fire an AP while the membrane potential of the simultaneously recorded cells is monitored; subthreshold synaptic responses are observed in connected cells in either a one-way or a bidirectional manner. The network connectivity is expressed as the percentage of observed connections between large numbers of sampled cells. The following two sections address the special role of voltage imaging in the analysis of excitatory and inhibitory connectivity.

excitatory connectivity.

Early pioneering paired recordings and post hoc reconstruction from randomly accessed pyramidal neurons revealed only 1–2% monosynaptic connectivity among CA3 pyramidal neurons, 7 of 400 pairs (Miles and Wong 1986), and 3% among neocortical L5/6 pyramidal neurons, 34 of 1,163 pairs (Deuchars et al. 1994). More recently, simultaneous whole cell electrophysiology of groups of up to four neurons in L2/3 of primary visual cortex (V1) revealed ∼19% connectivity (43/222 possible connections; 126 pairs). Interestingly, 116 of these had been previously identified as functionally active in vivo (Ko et al. 2011) with Ca2+ imaging. In barrel cortex slices, multiple simultaneous recording from 2,550 neurons revealed 909 of 8,895 possible connections, i.e., ∼10% connectivity, but the connectivity varied within and between layers, ranging from ∼5% to 19% (Lefort et al. 2009).

Similarly, in the cerebral cortex, the pyramidal neurons were first identified on the basis of their long-range projection identities with in vivo retrograde labeling, and then their connectivity was quantified. The resulting connectivity values ranged from 5% to 19% depending upon the projection identity (Brown and Hestrin 2009b). More recently, similar connection probabilities have been identified in vivo in L2/3 of barrel cortex with single-cell recordings and ChR-based mapping (Pala and Petersen 2015).

The classical experimental approaches are high in resolution and effective, especially if combined with knowledge of neuron identity (Jiang et al. 2015; Tasic et al. 2016) or retrograde labeling to establish projection identity (Brown and Hestrin 2009a). Nevertheless, such work remains technically demanding and time consuming and currently precludes analysis of dynamic changes in connectivity, for example, during plasticity or disease.

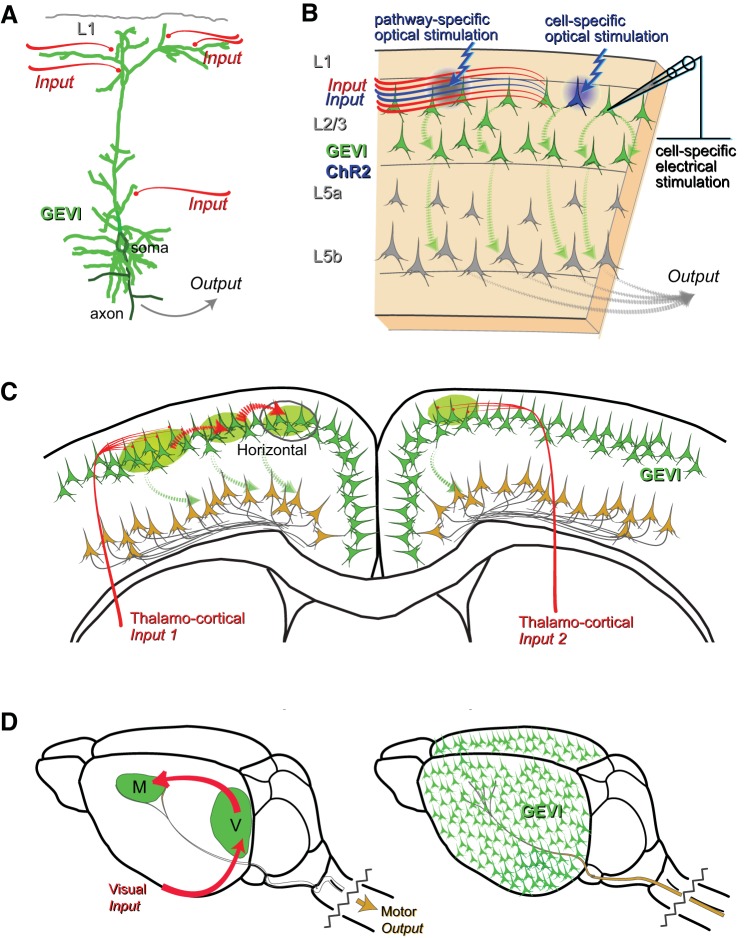

An alternative, potentially much higher-throughput, approach to mapping functional connectivities is provided by the combination of a single whole cell recording and GEVI-based imaging. The concept is to activate one pyramidal neuron among the others that are monitored by high-resolution voltage imaging (Fig. 4). GEVI imaging in response to single-cell AP input to the network will detect subthreshold excitatory responses of connected neighbor pyramidal neurons (E-E); we can consider this as a one-to-many INPUT connectivity map. Furthermore, as discussed in Voltage imaging of dendrites and spines, responses barely detectable at the soma by a classical electrode recording are often highly visible as membrane voltage changes in the dendrites. By providing this type of additional spatial dimension, GEVIs have the potential to radically influence how we assess and interpret the functional properties of short-range connectivity.

Fig. 4.

Schematic of how GEVIs can interrogate circuits at multiple levels—using a GEVI expressed specifically in L2/3 cortical neurons as an example. A: single-cell voltage signals from genetically identified L2/3 neurons to assess how these can be integrated across the dendrite to generate output signals at the soma and axon. B: GEVI-based single-cell and pathway-specific local network interrogation using optical (e.g., using ChR2) or electrical (electrophysiological) stimulation of inputs. L5 output neurons are not labeled. Synaptically connected L2/3 neurons integrate their subthreshold inputs and provide a spatial map of connections within the locally activated network. C: simplified illustration of how GEVIs can report longer-range activity from, e.g., 2 different thalamocortical inputs (1 and 2) to L2/3 of motor cortex with hypothetical different levels of thalamocortical synaptic input (left and right hemispheres). Input 1 leads to a larger GEVI signal than input 2 to illustrate the concept of how the size of the GEVI signal represents the level of connectivity at the input. Also shown is the concept of spread of subthreshold activity via recruitment of horizontal monosynaptic connections across cortical boundaries. D: simplified systems-level example to explain the concept of how GEVI expressed in L2/3 neurons (right image) can generate an “input map” in vivo (left image). For example, a visually evoked movement could first generate an input map in L2/3 neurons of visual cortex (V) that propagates via unseen output (L5, to other cortical and subcortical structures) to synaptically activate motor cortex (M) input, seen by L2/3 neurons, to then drive L5 motor output.

Circuit connectivity maps have already been successfully generated with ChR2 (Hooks et al. 2011; Pala and Petersen 2015; Yang et al. 2013) or caged glutamate (Kötter et al. 2005; Schubert et al. 2001) to provide patterned stimulation of excitatory neurons, often in a gridlike manner, while making a classical electrical recording from a single neuron. These optical approaches have successfully identified how connections among pyramidal neurons, for example in sensory cortex, receive different layer-specific inputs that work together to generate specific projection outputs (Hooks et al. 2011).

More recently, in the medial entorhinal cortex (mEC), local excitatory and inhibitory connections between four different identities of L2 neurons were revealed with cell-specific genetic targeting allied with electrophysiological phenotyping and targeted optical stimulation (Fuchs et al. 2016). Interestingly, the organization of these excitatory and inhibitory connections may underpin the “attractor dynamics” necessary for mEC grid cell outputs. Moreover, selective optical stimulation revealed distinct long-range septal-to-mEC inhibitory connections that could be responsible for septal modulation of mEC theta activity in vivo (Fuchs et al. 2016).

Challenges of these optical mapping approaches include the timing and nature of the optical stimulation, particularly the precise control over optically activated input elements (e.g., whether the soma, dendrites, or bypassing axons or synaptic terminals within the illumination spot are activated), and time resolution and linearity of the optical indicators.

local and long-range inhibitory connections.

Recurrent inhibition is critical for controlling the spread of excitation through locally connected networks. Pioneering dual-recording approaches and post hoc reconstructions have identified classes of GABAergic interneurons and their widespread, ordered axonal projections to excitatory pyramidal neurons (I → E) (Buhl et al. 1994). The recent simultaneous recording of up to eight neurons in thick slices of adult V1 mouse cortex (where dendrites remain intact and a larger number of connections can be preserved) has provided further exciting new insights into the connections between different types of interneurons and pyramidal neurons, including connections to neurogliaform cells (Jiang et al. 2015). This most recent work heralds a new consensus of cortical connectivity with unprecedented detail. In the same report, the validity of several interneuron genetic targeting strategies was also assessed. We expect that in future studies GEVIs will be targeted in this way (or even to subclasses of GABAergic cells) while activating the network with a single pyramidal neuron, either electrically or optically (e.g., ChR2). This could provide reliable assessment of the E-I connections in a high-throughput one-to-many type configuration. Furthermore, since voltage imaging can reliably detect hyperpolarization (Akemann et al. 2012; Canepari et al. 2010), GEVIs also have the potential to detect the consequences of local inhibition for individual neurons and populations of neurons (Oldfield et al. 2010; Steriade et al. 1993).

Local and long-range, or interareal, feedforward synaptic inhibition are critical for cortical function. For example, removal of local inhibition unmasks excitatory connections to an extent that is sufficient to drive the spread of epileptiform activity (Chagnac-Amitai and Connors 1989). Demonstrated in the motor cortex, removal of interareal feedforward inhibition also unmasks long-range excitatory connections and expands motor representation in the primary motor cortex (M1) (Jacobs and Donoghue 1991). More recently shown in the visual cortex, pathway-specific differences in the activation of feedforward areal inhibition were found in V1 vs. the higher lateromedial extrastriate area (LM) with classical electrophysiology from pathway-specific retrogradely identified neurons with ChR-based mapping (Yang et al. 2013). GEVIs directed to these specific classes of interneurons in visual cortex could also improve our understanding of how feedforward inhibition is recruited in V1 and LM visual areas.

In the barrel cortex, voltage-sensitive dye recordings in vivo revealed how sensory stimulation activates a spatial pattern of surround and rebound inhibition followed by 16-Hz oscillations (Derdikman et al. 2003). How the spatiotemporal organization of inhibitory interneurons may generate these 16-Hz oscillations remains unknown, particularly as classical voltage-sensitive dye imaging reports signals from all cell types and all cellular compartments including dendrites, unmyelinated axons [see also Large-field-of-view mesoscopic voltage imaging], and glia.

Voltage imaging for assessing long-distance connections in hippocampus.

Voltage-sensitive dye imaging has been widely and successfully used to monitor the propagation of electrical activity through the classical hippocampal trisynaptic (DG-CA3-CA1) pathway (Grinvald et al. 1982; Nakagami et al. 1997). More recent studies expanded this approach to document changes in information flow during plasticity (recently reviewed by Stepan et al. 2015).

In many such studies, voltage-sensitive dye signals largely recapitulate local field potential (LFP) recordings and are argued to mainly represent activity of the predominant class of neurons found in the respective tissue (e.g., pyramidal cells in the case of cerebral cortex; for an example see Calfa et al. 2011). Notable differences between optical voltage indicator signals and LFPs are that 1) the polarity of LFP signals reverses across a layer of excited pyramidal cells (while the corresponding voltage signals do not reverse) and 2) voltage-sensitive dye signals are usually longer lasting than the LFP (Nakagami et al. 1997). These differences can be explained by the fact that LFPs measure current densities and not voltage amplitudes. As current is proportional to rate of change of voltage (I = dV/dt × C), slow potentials are associated with small currents irrespective of their amplitude. It is important to note that slow responses also may potentially arise from unhealthy preparations (inhibition compromised), phototoxicity, or the pharmacological effects of the dyes used (Grandy et al. 2012; Mennerick et al. 2010). However, in contrast to LFPs that report current densities that relate to changes in membrane potential occurring far away from the recording electrodes, voltage indicators report the transmembrane voltage transient from the very piece of plasma membrane to which the voltage probe is attached. Hence, the spatial resolution of voltage imaging is only limited by the optical instrumentation.

An example of the type of additional insight gained from hippocampal voltage-sensitive dye recordings was the identification of the spatiotemporal dynamics of CA2 recruitment during hippocampal mossy fiber-initiated synaptic transmission. Fast voltage-sensitive dye imaging identified classical CA3-to-CA1 Schaffer collateral-based propagation (∼7-ms delay) that was often accompanied by a slower transmission (∼10-ms delay) and specific voltage-sensitive dye signal within the CA2 network (Ang et al. 2005; Tominaga et al. 2002). This suggested that under certain conditions CA2 behaved as a “delay-relay” during activity propagation in the hippocampal pathway (Sekino et al. 1997). More recently, feedforward recruitment of CA2 inhibitory interneurons was identified to underpin this “delay-relay.” Furthermore, long-term depression of the excitation of CA2 inhibitory interneurons permitted distal excitation of CA2 pyramidal neurons, allowing them to fire and relay activity to CA1 (Nasrallah et al. 2015). The significance of CA2 and its connections was recently highlighted as critical for social memory (Hitti and Siegelbaum 2014; Stevenson and Caldwell 2014) and in a mouse model of schizophrenia where CA2 is functionally disconnected from the trisynaptic pathway by excessive feedforward inhibition (Piskorowski et al. 2016).

Connecting local circuits for ensemble activity and synchronized oscillations.

Groups or ensembles of neurons working together in space are often synchronized in time by rhythmic activity. Various frequencies of “brain rhythms” (Buzsáki and Freeman 2015), which exist and overlap in the central nervous system, are proposed to fulfill a variety of roles such as serving as a timing signal or carrier frequency (Singer 1993). A key question is how the functional connectivity within a neuronal network supports the repertoire of oscillations that a particular network can produce. The literature contains many examples where ensemble activity is assessed in vivo and in vitro by using multiple single-unit recordings, LFPs, or Ca2+ imaging to analyze coherent AP output of a group of neurons. Less advantage has been taken from the potential of voltage imaging for detecting synchronization and rhythmicity at the cellular/circuit level. However, a significant literature exists at the mesoscopic level (mm scale), describing wavelike propagation of electrical activity and voltage-sensitive dye signals in hyperexcitable or epileptiform cortical activity (Coulter et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2008). We predict that the cellular specificity of targeting of GEVIs will further facilitate mesoscopic analysis in the future by helping to determine the contributions of different neuron types to local activity and/or widespread global activity.

dynamic ensembles, propagating waves, and low-frequency oscillations in cortex.

Within large coronal slices of rat somatosensory cortex, use of the voltage-sensitive dye oxonal derivative RH479 successfully identified “dynamic ensembles” of cortical neurons (within an array area of 0.3 × 0.3 mm2) (Wu et al. 1999). These dynamic ensembles appear as cohesive (not expanding) propagating and self-sustaining “hot spots” of activity during 6- to 10-Hz oscillations either in response to stimulation or after a low-Mg2+-induced epileptiform burst. The dynamic ensembles propagate bidirectionally between layers and across columns and can also be seen to collide with other ensembles. These dynamic ensembles are much smaller in amplitude and more cohesive than the “wholesale” synchronization of the slice during epileptiform seizurelike activity (Meierkord et al. 1997). However, like epileptiform behavior (Wadman and Gutnick 1993), the dynamic ensembles exhibited the propensity to abruptly change their propagation speed (6–10 mm/s), for reasons that are not yet clear.

Voltage-sensitive dyes also reveal propagating waves in hyperexcitable/epileptiform activity in tissues where inhibition is blocked; these waves propagate at ∼80–130 mm/s and are dependent upon glutamatergic synaptic activity (Golomb and Amitai 1997) and are slower than nonmyelinated axon conduction velocities. In contrast to the propagating waves, oscillations are slower and regarded as being “one cycle, one wave,” where each oscillation cycle measured at a given location is associated with a wave passing through that location, as seen in carbachol-induced oscillations (Huang et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2008). The advantage of voltage-sensitive dye imaging over standard electrode recordings is the availability of spatiotemporal resolution, allowing the detection of multiple “one cycle, one wave” oscillators. If the oscillators are weakly coupled then there will be phase lags between them, allowing effective separation not only in space but also in time. The network oscillators can also interact with each other to produce spiral waves, or extinction by collision (Huang et al. 2004, 2010; Xu et al. 2007). However, if the interactions are very weak then the oscillations might remain independent and could even be of a different frequency (Bao and Wu 2003). Conversely, if mutual coupling is very strong then oscillations will be tightly synchronized over space (with “zero phase”) and there will be no propagating wave, as in hippocampal CA3; see also hippocampal high-frequency oscillations (Coulter et al. 2011; Mann et al. 2005).

Future use of GEVIs can build upon the voltage-sensitive dye work to identify the nature of the circuitry underlying these dynamic ensembles and local oscillators and to determine how they work together. Further investigation should also focus on how local oscillations sustain themselves and whether these self-sustaining properties are critical for cortical reverberation, a mechanism whereby a weak input to a local network is amplified in both animal and human circuits (Straub et al. 2003; Wu et al. 1999).

hippocampal high-frequency oscillations.

Network oscillations in the gamma range (30–100 Hz) are a defining feature of the awake brain but are also seen during REM sleep and in brain slices (Buzsáki and Wang 2012). In the hippocampus gamma oscillations are thought to underlie memory processing (Mann et al. 2005), and the CA3-CA1 axis is thought to provide the intrinsic gamma generator. Imaging of gamma-frequency oscillations using either voltage-sensitive dyes (Middleton et al. 2008) or GEVIs (Akemann et al. 2012) is technically challenging because of small signal amplitudes, so the majority of investigations have utilized classical electrophysiology to understand these rhythms. At the single-cell and network levels gamma is generated by the tight spike synchrony between APs in pyramidal neurons and interneurons and can be induced in vitro either by carbachol, to increase cholinergic tone (Buhl et al. 1998; Mann et al. 2005), or by kainic acid (Fisahn et al. 2004). Voltage-sensitive dye imaging of carbachol-induced gamma oscillations in CA3 in vitro revealed a spatiotemporal pattern whereby the maximum depolarization during the oscillations occurred in stratum pyramidale (soma) matched by a corresponding minimum or hyperpolarization in stratum radiatum (dendrites). The oscillations were driven by rhythmic firing of inhibitory interneurons providing alternate inhibition of pyramidal neuron cell bodies. Critically, gamma oscillations require glutamatergic AMPA receptor-mediated subthreshold synaptic excitation of the interneurons, and this is likely to be a major contributor to the changes in the voltage-sensitive dye signal. More recently, the synaptic contribution to maintain tight synchrony between CA3 pyramidal neurons and interneurons during gamma has been further established (Salkoff et al. 2015).

High-frequency network oscillations such as sharp wave ripple complexes (SPW-Rs) (Ylinen et al. 1995) can be induced in hippocampal slices to study the cellular correlates of assembly formation (Bahner et al. 2011; Both et al. 2008; Keller et al. 2015). During these oscillations intracellular microelectrode recordings revealed network-entrained APs in a subset of pyramidal cells, yielding a strict distinction between participating and nonparticipating neurons (Bahner et al. 2011; Both et al. 2008). Addressing these types of circuit-level questions could be greatly facilitated by voltage imaging of many cells with single-cell resolution. Toward this goal, GEVIs have been targeted with in utero electroporation to hippocampal CA3 and have been shown to reliably detect 25-Hz kainate-induced gamma oscillations (Akemann et al. 2012). In these experiments, the Butterfly1.2 signal was phase-shifted with respect to the LFP; this is in line with the fact that LFPs reflect the extracellular current density associated with the transmembrane currents that change the membrane voltage. The recent development of faster-reporting GEVIs (Mishina et al. 2014) now allows the capture of oscillations with frequencies up to 200 Hz. These new GEVIs will greatly improve the ability to detect the spatiotemporal behavior and the identity and connectivity of the cells that contribute to gamma oscillations both in vitro and in vivo.

synchronous ensemble activity in cerebellar network.

Cerebellar slices were among the first intact mammalian brain tissue preparations in which high-speed (<1 kHz) voltage imaging and imaging of population oscillations were achieved (Middleton et al. 2008; Vranesic et al. 1994). Voltage-sensitive dyes have also identified ensemble activity during low-frequency oscillations in the inferior olive (IO), where closely spaced synchronized oscillating clusters of several hundred IO neurons unite together to provide the highly synchronized afferent input to the cerebellum (Leznik et al. 2002). Spatially, the IO clusters consisted of core member neurons with a rim of more loosely connected neurons. Spatiotemporally the core remained the same size, but the amplitude of the voltage-sensitive dye signal varied with the phase of the oscillation, whereas the rim area was largest at the peak of the oscillations. The mechanism underlying this recruitment is not known but may involve gap junction coupling. Of wider significance is that, by uniting the different individual ensembles in space, the IO can generate synchronous, movement-related activation of distinct parasagittal bands of Purkinje neurons in the cerebellar cortex (Leznik et al. 2002).

In the cerebellar cortex, granule cells are recruited by sensory inputs. Voltage-sensitive dye imaging in slices revealed the spatial distribution of clustered granule cell activity for resonant theta oscillations. In this study, the tightly synchronized granule cell AP firing as well as the intact inhibitory network that provides the resonant oscillator formed the basis for the resonance (Gandolfi et al. 2013). GEVIs specifically directed either to granule cells or to Golgi cells raise the exciting prospect of detecting cell-specific contributions to the resonant frequency both in vitro and in vivo.

Systems-Level Voltage Imaging Approaches

GEVIs—a modern evolution from single-unit recordings and local field potentials.

Electrophysiological approaches to studying functions at the level of the intact brain began with the development of electroencephalography, demonstrating that different brain states are associated with distinct signatures of brain electrical signaling (Swartz and Goldensohn 1998). Single-unit (AP) recordings have been crucial in defining neuronal representations of sensory and motor information in terms of AP occurrence during sensory inputs and motor outputs at the systems level. This approach culminated in the classical work of Hubel and Wiesel, which demonstrated that neurons in the visual cortex are individually tuned to specific sensory inputs (Hubel and Wiesel 1998). Multiunit recordings and their combination with population recordings (in form of LFPs) indicated the importance of coordination of single-cell activities to generated sensory percepts and motor actions (Gray and Singer 1989; Schanze and Eckhorn 1997). During recent years microelectrode-based single-unit AP recordings from large numbers of cells have also been enabled by 2p Ca2+ imaging (Chen et al. 2013; Helmchen and Denk 2005).

Large-field-of-view mesoscopic voltage imaging.

In parallel to these “AP-centric” approaches, large-field-of-view (LFOV) voltage imaging in living animals evolved as a complementary methodology that emphasizes the neuronal information represented by very large numbers of neurons distributed over larger portions of the cortex of intact animals (Grinvald 2005; Grinvald and Hildesheim 2004). Originally developed with low-molecular-weight voltage-sensitive dyes, LFOV imaging of cortical activity typically uses wide-field 1p excitation, does not resolve single cells, but can resolve fast electrical signals typically digitized at frame rates of 1-0.05 kHz. The imaged population signals represent largely subthreshold (synaptic) activities and are therefore more closely related to EEG and electrocorticogram (ECoG) recordings than to AP recordings. However, as already pointed out, LFPs, EEGs, and ECoGs report electric current spreading through the tissue, whereas the voltage imaging reports transmembrane voltage; current spreads over millimeters of tissue, while localization of optical voltage signals is limited only by the resolution of their detection.

Voltage imaging of cortical activity at the mesoscopic level (covering several mm2 of cortical space but without resolving signal from individual cells) has been successfully performed with voltage-sensitive dyes, particularly in visual and somatosensory areas, and has contributed much to the understanding of cortical circuit dynamics (Ferezou et al. 2007; Grinvald and Hildesheim 2004; Grinvald and Petersen 2015; Mohajerani et al. 2010, 2013; Salzberg 2009; Xu et al. 2007). Despite these successful applications, the use of voltage-sensitive dyes in vivo suffers from the same limitations described above for ex vivo studies and several additional limitations that are of specific relevance for the aims of experiments in living animals. The most important among those are invasive staining procedures, pharmacological side effects, and contaminating optical signal components that represent hemodynamic processes rather than membrane voltage transients. These limitations have been overcome by the development of the differential dual-emission GEVIs (Akemann et al. 2010, 2012) (Fig. 5). The first generation of these probes, VSFP2.3 and VSFP2.42, provided proof of principle for GEVI imaging in living mice (Akemann et al. 2010), where cortical responses to whisker stimulation were imaged. In this study, the optical signals triggered by single whisker deflections of L2/3 pyramidal cells returned to baseline with an apparent time constant of ∼200 ms, and the question arose of whether this relatively slow time course is caused by slow indicator kinetics or if it represents the slow population synaptic potential of responsive pyramidal cells. In a subsequent study this issue was addressed by simultaneously imaging whisker deflection-induced optical signals of VSFP2.3 and the widely used small-molecular-size voltage-sensitive dye RH1691 (Mutoh et al. 2015). The study concluded that VSFP2.3 reported cortical population responses with time courses and amplitudes comparable or better than RH1691, indicating that in these type of experiments the response kinetics are not limited by the kinetics of this early and relatively slow VSFP2.x type of GEVI. Further development of VSFP2s led to VSFP Butterflies (Akemann et al. 2012). VSFP Butterfly 1.2 improved upon the performance of VSFP2s, particularly in the detection of subthreshold signals, permitting in vivo evaluation of cortical circuit dynamics in the context of the criticality hypothesis (Scott et al. 2014) and imaging of visual, somatosensory, and auditory cortical maps in awake mice (Carandini et al. 2015; Madisen et al. 2015) (Fig. 5). More recent Butterfly versions with improved kinetics (Mishina et al. 2012) and response amplitudes (Sung et al. 2015) have been developed.

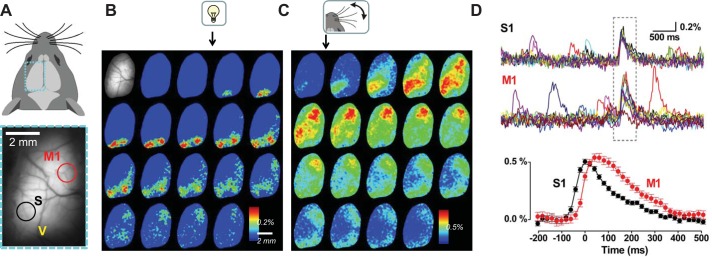

Fig. 5.

Cortex-wide voltage imaging. A, top: schematic dorsal view of the mouse head. Bottom: transcranial mCitrine fluorescence image of the left cortical hemisphere in a mouse expressing VSFP butterfly (Akemann et al. 2012). The imaged cortical region is indicated as a dotted rectangle (cyan) in the schematic at top; M, S, and V indicate motor, somatosensory, and visual cortical regions. Donor (mCitrine) and acceptor (mKate2) signals were acquired with 2 synchronized CCD cameras at 50 frames/s in 4-s-lasting trials during which either a visual stimulus (5 ms light flash, B) or a single deflection of the contralateral C1 whisker (C) was delivered. B and C: peristimulus, single-trial sequence of ΔR/R0 (indicating changes in membrane voltage) images spatially filtered with a 2 × 2 Gauss kernel. The first image (grayscale) in B shows the mCitrine baseline image with pixels outside of the optical window masked. Note the spread of neuronal activation from sensory to motor cortices. D, top: time courses of 25 consecutive trials of signals over regions of interest selected within somatosensory and motor areas (black and red circles in A). Time window of the response to whisker deflection is indicated by dotted rectangle. Depolarizing events outside of this time window are spontaneous. Bottom: average of the evoked S1 and M1 response (25 trials) at enlarged timescale. Note similarity between spontaneous and stimulation-evoked events. Partially redrawn from Akemann et al. (2015) with permission.

Understanding the INPUT map nature of the GEVI signal from in vivo systems-level mesoscopic imaging data requires careful registration with known anatomical and functional maps. The availability of online interactive mouse connectivity atlases, such as those from the Allen Brain Institute, now allows the development of “virtual retrograde/anterograde” or “input” maps, and these will become increasingly important to inform the interpretation of functional maps (Cao et al. 2015).

The current state of GEVI-based imaging represents a clear advance upon classical mesoscopic voltage-sensitive dye-based in vivo imaging; however, it does not yet reach the goal of relating electrical signals of individual neurons to cognitive and emotional processes. Although GEVIs with response dynamics that are compatible with recordings of fast APs in vivo are already available (Abdelfattah et al. 2016; Gong et al. 2015; St-Pierre et al. 2014), their performance is currently not sufficient to supersede Ca2+ imaging approaches for the monitoring of AP patterns. As the most advanced GECIs are doing very well for the purpose of AP detection, voltage imaging of AP patterns may even not be considered a pressing goal. However, as described above for the in vitro voltage imaging approaches (cell and circuit levels), there are questions that cannot be sufficiently covered by single-cell level calcium imaging approaches but are amenable to currently available GEVIs. Nevertheless, continued development of brighter, more sensitive, faster, and more linear GEVIs is needed, as is optimization and de novo development of specialized GEVI imaging equipment. For instance, cellular resolution functional imaging will require novel 2p microscopes that are able to monitor activity patterns of a large number of neurons updated at approximately each millisecond. The current trend of 2p optical instrumentation advances toward solutions that involve spatial, temporal, and possibly spectral multiplexing strategies enabled by multifocal, temporal focusing and holographic technologies (Emiliani et al. 2015; Oron et al. 2012; Shtrahman et al. 2015). Another possibility that should not be neglected is 1p approaches that resolve single cells in vivo such as GRIN lenses (Jung et al. 2004; Tang et al. 2015) or light sheet approaches (Bouchard et al. 2015).

Outlook

Voltage imaging, in particular with the recent accelerated development of GEVIs, remains an exciting and forward-looking approach to fundamental questions about the working of the brain. As discussed above, simultaneous voltage and calcium imaging using dual expression of genetically encoded voltage and calcium indicators holds much promise to assess both subthreshold INPUT activity and suprathreshold AP-based OUTPUT activity at the same time. Creating the expression constructs (and gene-targeted mice) to do this is not trivial, nor are the technical challenges to imaging different fluorophores at high spatial and temporal resolution (Jaafari et al. 2015; Popovic et al. 2011), but there is little doubt that these technical hurdles will be overcome in the near future. More ambitious, but clearly one of the next goals, will be the combination of GEVI-based voltage imaging with genetically targeted optogenetic actuators to achieve 1) optical excitation, 2) optical inhibition, and 3) optical monitoring of electrical activity (voltage) of a large number of neurons in an intact neural circuit at “single-cell” resolution. If optical imaging using GEVIs can be combined with genetically targeted optogenetic actuators (e.g., ChR2-mediated excitation of specific cell types/groups to activate a pathway of choice), then generating a “read/write” interface to the brain becomes a reality. This combination would enable a bidirectional dialog between the “circuit interrogators” and the object of their study—the behaving experimental animal. With continued advances in genetic targeting (and hence attribution of optical signals to defined cell populations), the robust nontoxic fluorescent nature of GEVIs and GECIs and the dramatic recent improvements in CCD sensor array technology (low noise, array sizes, readout speeds) make for an exciting future for targeted multimodal optical recordings in the brain.

GRANTS

The work of the authors' laboratories has been funded by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grants MH-104775 and MH-109091 (S. D. Antic), Brain Research New Zealand (R. M. Empson), Marsden Royal Society of New Zealand (R. M. Empson), the Human Frontier Science Program (HFSP) (T. Knöpfel), NIMH Grant 1U01 MH-109091-01 (S. D. Antic and T. Knöpfel), and RIKEN (T. Knöpfel).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.D.A., R.M.E., and T.K. prepared figures; S.D.A., R.M.E., and T.K. drafted manuscript; S.D.A., R.M.E., and T.K. edited and revised manuscript; S.D.A., R.M.E., and T.K. approved final version of manuscript; T.K. interpreted results of experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

S. D. Antic thanks Dejan Zecevic for expert advice and Pavle Andjus and Brana Jelenkovic for new ideas on the use of photons in biology (Photonics Workshop Kopaonik). T. Knöpfel particularly thanks gifted students in his laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript and many helpful suggestions: Taylor Lyons, Peter Quicke, Gerald Moore, Elisa Ciglieri, and Chenchen Song. We also acknowledge the many other important contributions in the voltage imaging community that, regrettably, could not be included in the present review owing to focus and space constraints.

REFERENCES

- Abdelfattah AS, Farhi SL, Zhao Y, Brinks D, Zou P, Ruangkittisakul A, Platisa J, Pieribone VA, Ballanyi K, Cohen AE, Campbell RE. A bright and fast red fluorescent protein voltage indicator that reports neuronal activity in organotypic brain slices. J Neurosci 36: 2458–2472, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acker CD, Loew LM. Characterization of voltage-sensitive dyes in living cells using two-photon excitation. Methods Mol Biol 995: 147–160, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acker CD, Yan P, Loew LM. Single-voxel recording of voltage transients in dendritic spines. Biophys J 101: L11–L13, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akemann W, Lundby A, Mutoh H, Knopfel T. Effect of voltage sensitive fluorescent proteins on neuronal excitability. Biophys J 96: 3959–3976, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akemann W, Mutoh H, Perron A, Park YK, Iwamoto Y, Knopfel T. Imaging neural circuit dynamics with a voltage-sensitive fluorescent protein. J Neurophysiol 108: 2323–2337, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akemann W, Mutoh H, Perron A, Rossier J, Knopfel T. Imaging brain electric signals with genetically targeted voltage-sensitive fluorescent proteins. Nat Methods 7: 643–649, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akemann W, Song C, Mutoh H, Knopfel T. Route to genetically targeted optical electrophysiology: development and applications of voltage-sensitive fluorescent proteins. Neurophotonics 2: 021008, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alle H, Geiger JR. Combined analog and action potential coding in hippocampal mossy fibers. Science 311: 1290–1293, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang CW, Carlson GC, Coulter DA. Hippocampal CA1 circuitry dynamically gates direct cortical inputs preferentially at theta frequencies. J Neurosci 25: 9567–9580, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antic SD. Action potentials in basal and oblique dendrites of rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Physiol 550: 35–50, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antic S, Zecevic D. Optical signals from neurons with internally applied voltage-sensitive dyes. J Neurosci 15: 1392–1405, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archie KA, Mel BW. A model for intradendritic computation of binocular disparity. Nat Neurosci 3: 54–63, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahner F, Weiss EK, Birke G, Maier N, Schmitz D, Rudolph U, Frotscher M, Traub RD, Both M, Draguhn A. Cellular correlate of assembly formation in oscillating hippocampal networks in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: E607–E616, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BJ, Mutoh H, Dimitrov D, Akemann W, Perron A, Iwamoto Y, Jin L, Cohen LB, Isacoff EY, Pieribone VA, Hughes T, Knopfel T. Genetically encoded fluorescent sensors of membrane potential. Brain Cell Biol 36: 53–67, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao W, Wu JY. Propagating wave and irregular dynamics: spatiotemporal patterns of cholinergic theta oscillations in neocortex in vitro. J Neurophysiol 90: 333–341, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]